Abstract

Based on nanoarchitectonics and molecular dynamics simulations, we investigate the structural properties and diffusion pathway of Na atoms in sodium trisilicate over a wide temperature range. The structural and dynamics properties are analyzed through the radial distribution function (RDF), the Voronoi Si- and O-polyhedrons, the cluster function fCL(r), and the sets of fastest (SFA) and slowest atoms (SSA). The results indicate that Na atoms are not placed in Si-polyhedrons and bridging oxygen (BO) polyhedrons; instead, Na atoms are mainly placed in non-bridging oxygen (NBO) polyhedrons and free oxygen (FO) polyhedrons. Here BO, NBO, and FO represent O bonded with two, one, and no Si atoms, respectively. The simulation shows that O atoms in sodium trisilicate undergo numerous transformations: NBF0 ↔ NBF1, NBF1 ↔ NBF2, and BO0 ↔ BO1, where NBF is NBO or FO. The dynamics in sodium trisilicate are mainly distributed by the hopping and cooperative motion of Na atoms. We suppose that the diffusion pathway of Na atoms is realized via hopping Na atoms alone in BO-polyhedrons and the cooperative motion of a group of Na atoms in NBO- and FO-polyhedrons.

1. Introduction

It is well known that the structure of silica (SiO2) is an archetypal network-forming system containing SiO4 tetrahedra. The addition of doped Na ions generates non-bridging oxygen (NBO) [1,2]. Therefore, sodium trisilicate (Na2O∙3SiO2) has various anomalous properties which are essential for industrial applications, ceramics, metallurgy, and glass technologies, as well as for understanding the fundamentals of minerals [3,4,5]. Na2O∙3SiO2 has been extensively studied using experimental methods such as photoelectron spectroscopy [6], X-ray diffraction [4,7], in situ Raman spectroscopy, and elastic neutron scattering [8], along with various simulation techniques [9,10,11,12]. Nesbitt et al. have characterized two types of network oxygen in sodium silicate: three-fold-coordinated BO-Na and two-fold-coordinated Si-O-Si [6]. The doped Na ions function as a network modifier, causing significant alterations in the random network of corner-shared SiO4 tetrahedra with the formation of FO and NBO. Davidenko et al. reported that Na2O-SiO2 has a micro-heterogeneous structure which contains noncrystalline micro-groups such as silica, Na disilicate, and Na monosilicate [7]. Zhao et al. indicated that, when enough Na2O is added into the glass matrix to create two NBO atoms (Q2 species), the silica network loses its three-dimensional connectivity needed to sustain the local transformations between α-like and β-like rings, and glass softens upon heating due to the dominant anharmonic effect [8].

The nanoarchitectonics and molecular dynamics (MDs) simulation can provide more detailed information about both the microstructural properties and diffusion mechanisms at the atom level to develop functional materials (Figure 1). The results of MDS found that in sodium silicate, the extent of polymerization reduces from pure SiO2 to 2Na2O∙SiO2 [9,10,11,12]. Alongside the BO/NBO ratio and polymerization extent, other factors such as the bond length, bond angle, coordination number, distribution of ring sizes, and distribution of void sizes are also utilized to examine the structure at short- and mid-range scales. However, the spatial distribution of Na in Na2O∙3SiO2 remains not yet fully clarified.

Figure 1.

Outline of nanoarchitectonics and molecular dynamics simulation: meaning and procedure.

The very fast diffusivity of alkali atoms is one of the important dynamical properties of alkali silicates [13,14,15,16,17,18,19]. The addition of doped Na ions to pure SiO2 leads to a decoupling of alkali diffusion and diffusive transport in the Si-O network. Davidenko et al. suggested that a distribution where increasing alkali oxide content causes homogeneous, increasing disruption to the Si-O network of pure SiO2 is in conflict with the highly nonlinear dependence of viscosity on alkali concentration [20]. In accordance with other studies [21,22,23,24], the existence of the decoupling of alkali diffusion and diffusive transport in the relatively immobile Si-O network is proposed to interpret the fast diffusivity of alkali ions. The pre-peak at 0.9 Å−1 in the structure factor measured experimentally for alkali silicates is evidence for the diffusion pathway.

Various experimental results have shown that the structure of these silicates is found to comprise micro-regions with high Na concentrations. The two structural samples, the modified random network and the compensated continuous random network, predict some clustering of alkali atoms in the silicate’s structure [25,26,27]. This indicates that the clustering of alkali atoms marks out their diffusion pathway.

Several models for diffusion mechanisms in alkali silicate are suggested [28,29,30]. It is demonstrated that the diffusion pathway occupies a relatively small subspace of the system. According to Horbach et al. and Smith et al., the activated hopping of Na through the Si-O matrix is frozen with respect to the movement of Na atoms [9,31]. Based on the position of the first peak of the pair radial distribution function (RDF) for the Na-Na pair, they determine the mean hopping distance of Na atoms. The alkali ions hop into empty sites so that the mechanism owes more in character to their vacancy crystalline counterpart than to their interstitial cousins [32,33,34]. Habasaki et al. indicated that the cooperative motion mechanism may be suitable to clarify the increasing diffusivity with increasing alkali content [35]. Traps due to defects or impurities can lead to a decrease in charge carrier mobility and an increase in recombination rates in semiconductors [36]. However, many fundamental aspects of the fast diffusion of Na in Na2O∙3SiO2 remain up for debate.

Therefore, in this present study, we focus on Na2O∙3SiO2 at different temperatures. Based on the characteristics of the pair RDF, the Voronoi Si- and O-polyhedrons, the cluster function, fCL(r), and the sets of fastest (SFA) and slowest atoms (SSA), we attempt to gain insight into the spatial distribution as well as the diffusion pathway of Na in the Na2O∙3SiO2.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Characteristics of Structural Na2O∙3SiO2

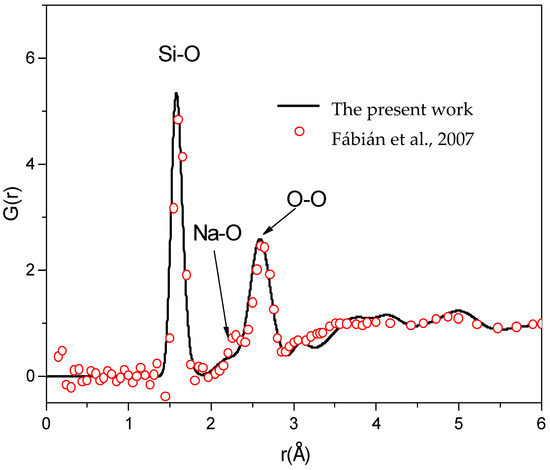

The total RDF for neutron diffraction, G(r), for Na2O∙3SiO2 is presented in Figure 2. This RDF exhibits the short-range order (SRO). As shown in Figure 2, the first peak of G(r) is located at 1.60 ± 0.02 Å, which is contributed to by gSi-O(r), exhibiting the Si-O bond length. The second and third peaks of G(r) are located at 2.25 ± 0.02 Å and 2.60 ± 0.02 Å, which are contributed to by gNa-O(r) and gO-O(r), exhibiting the Na-O and O-O bond lengths, respectively. It can be seen that there is good agreement between the experimental and simulated G(r) RDFs for an r of up to 6 Å [1]. Using the method in [37], the calculation result for the bond angle distribution indicated that the peaks of the O-Si-O and Si-O-Si bond angle distributions are located at 109.6° and 149.0°, respectively. For Si-O-Na, the bond angle distribution is centered around 90°–125°, very close to the experiments [1,7].

Figure 2.

The total RDF of sodium trisilicate at a temperature of 973 K and a comparison with experimental data [1], which was obtained from this work and reported in an experiment in [1].

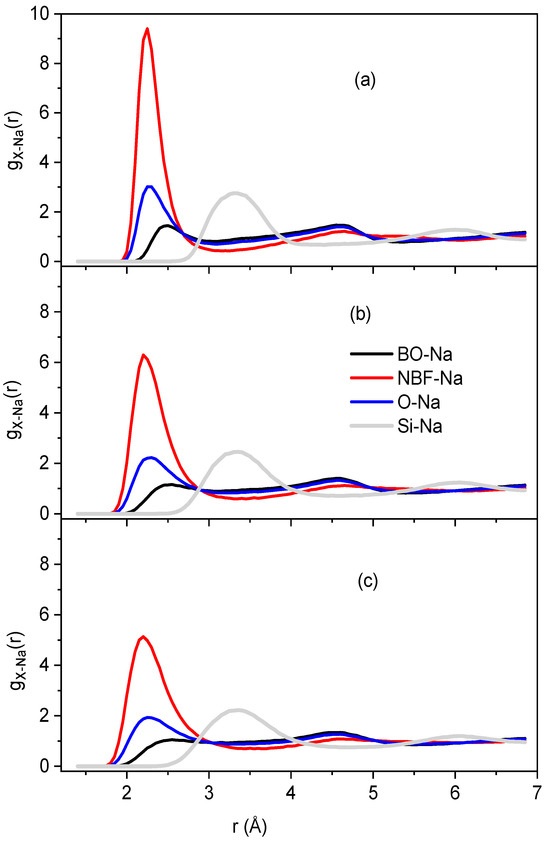

Figure 3 shows the RDF for the BO-Na, NBF-Na, O-Na, and Si-Na pairs at temperatures of 300, 973, and 1573 K. A pronounced peak is seen in gNBF-Na(r), which is not unclear for gBO-Na(r). Note that

where and mNBO, mBO, and mO are the total numbers of NBO, BO and O, respectively. This means that most of the Na is located around the NBF and is rarely present in the vicinity of BO. All the constructed samples consist of SiO4 along with BO and only fewer SiO5 particles in the high-temperature samples, indicating the tetrahedral network structure of Na2O∙3SiO2. The major O forms are NBO and BO, and less than 0.05% of the total O is FO. In addition, the relative fraction of O types was almost unchanged with temperature (Table 1). The spatial distribution of TOy (T is Si or Na, y = 4.5) in Na2O∙3SiO2 samples at different temperatures is shown. As seen, the structure of Na2O∙3SiO2 comprises mainly SiO4 units and a small count of NaO4 and NaO5 units, which are distributed over the whole space.

Figure 3.

The pair RDF for BO-Na, NBF-Na, O-Na, and Si-Na pairs at different temperatures: (a) 300 K; (b) 973 K, and (c) 1573 K.

Table 1.

Distribution of Na in O-polyhedrons and fraction of different types of O. Here, mAx is the number of Ax-polyhedrons; A is BO or NBF; x is the number of Na atoms in the Ax-polyhedron; mFO, mNBO, mBO, and mO are the total numbers of FO, NBO, BO, and O atoms, respectively.

The fractions of different types of O atoms are listed in Table 1. It can be seen that O-polyhedrons either do not contain or do contain Na; meanwhile, Si-polyhedrons do not contain any Na residues. Our simulation shows that most O-polyhedrons comprise BO0, BO1, NBF0, NBF1, and NBF2. It shows that BO0 and NBF0 represent an empty O-polyhedron which does not contain Na. As temperature increases, the fractions mBO1/mO and mNBF0/mO increase. In contrast, mBO0/mO and mNBF2/mO slightly change in the opposite direction. From these data, we can suggest a simple diffusion sample in Na2O∙3SiO2. Namely, Na travels from its site to empty sites which are located in BO- and NBF-polyhedrons. The motion of Na between polyhedrons leads to the diffusivity of Na.

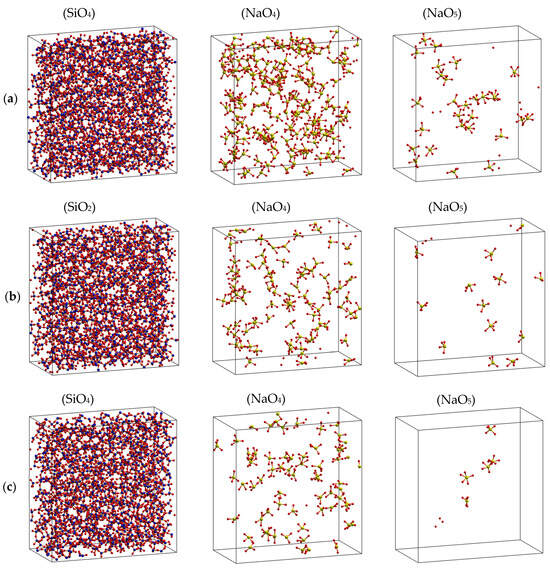

Next, more detail about the tetrahedral network structure of Na2O∙3SiO2 is derived from the characteristics of Voronoi polyhedrons, which are summarized in Table 2. As seen, the average volume per polyhedron increases in the order Si- → BO- → NBF-polyhedron. The total volume of BO- and NBF-polyhedrons, which contain Na, is about 87% of the simulation box. Although VBO is equal to 1.6 times VNBF, about 78–90% of total Na is placed in NBF-polyhedrons. As temperature increases, the amount of Na residing in NBF-polyhedrons decreases from 91 to 78%, corresponding with the temperature increasing from 300 to 1573 K. This demonstrates that Na atoms are not uniformly distributed through O-polyhedrons but instead are gathered in NBF-polyhedrons, as can be seen from Figure 4. This supports the idea that the diffusion pathway of Na occurs in NBF-polyhedrons with a total volume of 33.0–33.6% of the simulation box.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Voronoi polyhedrons. <vSi>, <vBO>, and <vNBF> are the average volumes per Si-, BO-, and NBF-polyhedron, respectively, measured in Å3; VSi, VBO, VNBF, and VSB are the volumes occupied by Si-, BO-, and NBF-polyhedrons and the volume of the simulation box, respectively; mNaBO and mNaNBF are the numbers of Na atoms residing in BO- and NBF-polyhedrons, respectively; and mNa is the total number of Na atoms.

Figure 4.

Spatial distribution of TOy (T is Si or Na, y = 4.5) in Na2O-3SiO2 models at different temperatures. Here, (a) 300 K, (b) 973 K, and (c) 1573 K, with O (red color), Si (blue color), and Na (yellow color).

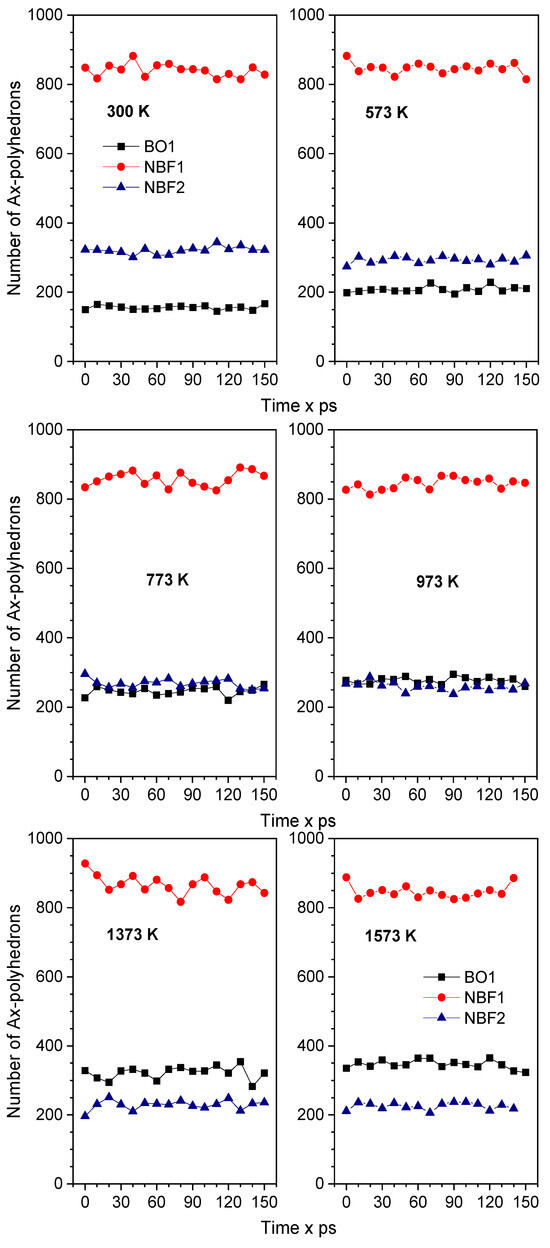

Figure 5 plots the number of BO1-, NBF1-, and NBF2-polyhedrons versus time at different temperatures. As seen, the number of NBF2-polyhedrons is larger than that of BO1 polyhedrons at low temperatures, and it becomes smaller at high temperatures. In the temperature range of 773–973 K, the number of NBF2-polyhedrons is the same as that of BO1 polyhedrons. This is explained by the fact that more Na spreads on BO-polyhedrons at high temperatures. This is also observed from the spatial distribution of all types of OT2 linkages (T is Si or Na), as plotted in Figure 6. As seen, the Si-O-Na and Si-O-Si linkages are dominant. There is only a small count of Na-O-Na linkages. These linkages slightly change with increasing temperature. This is explained by the fact that pure SiO2 is composed of a continuous random network of SiO4 tetrahedra and that the doped Na ions break the Si-O linkages, which leads to the generation of non-bridging oxygen (NBO) in Na2O∙3SiO2. The generation of NBO lowers the glass melting point.

Figure 5.

Time dependence of the number of Ax-polyhedrons at different temperatures. Here, A denotes an NBF or BO atom; x denotes the number of Na atoms in the Ax-polyhedron.

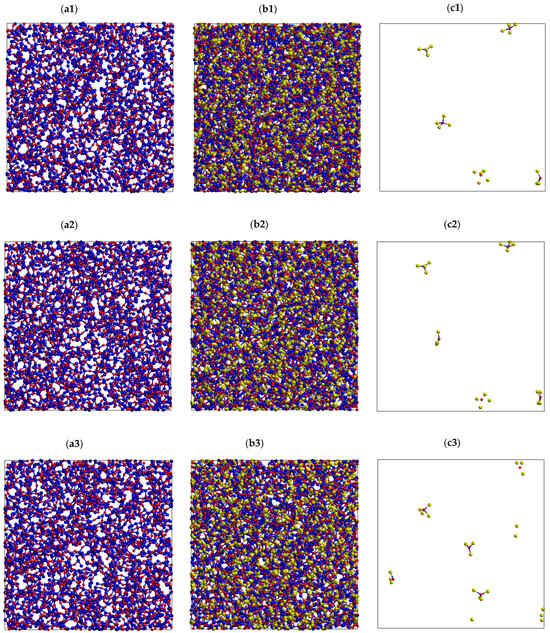

Figure 6.

Spatial distribution of all types of OT2 linkages (T is Si or Na) in Na2O-3SiO2 at different temperatures, (a1–c1) 300 K; (a2–c2) 973 K; and (a3–c3) 1573 K, with O (red color), Si (blue color), and Na (yellow color). Here, (a1–a3) is Si-O-Si; (b1–b3) is Si-O-Na; and (c1–c3) is Na-O-Na linkage, respectively.

2.2. The Diffusion Pathway of Na Atoms in Na2O∙3SiO2

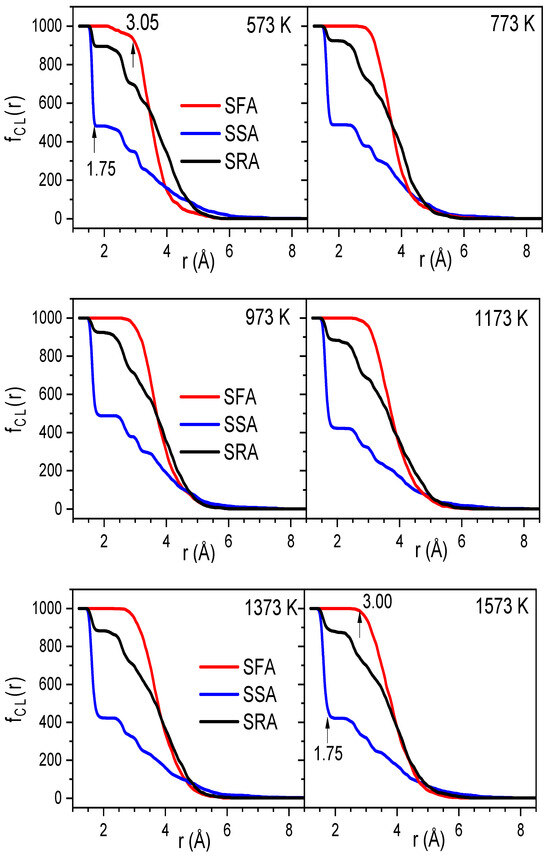

To demonstrate the clustering of Na atoms, we use the link cluster function, fCl(r); the calculation algorithm employed here can be found elsewhere [38,39]. The sets of fastest, slowest, and random atoms (SFA, SSA, and SRA) comprise about 10% of all the atoms. The SFA has a mean square displacement (MSD) larger than that of the remaining atoms. The SSA has an MSD smaller than that of the remaining atoms. The SRA contains atoms that are randomly chosen from the sample. The atoms in the SFA, SSA, and SRA are determined from the atom position in the configuration at 150 ps. Figure 7 plots fCl(r) at different temperatures. As seen, in the temperature range of 300–1573 K, the considered sets are mostly unchanged. However, the variations in the SSA, SFA, and SRA are quite different with r; namely, the SSA drops drastically from 1000 to 483 atoms as r varies from 1.3 to 1.75 ± 0.05 Å. The value of fCl(r) at 1.75 Å is about 1000 and 895, corresponding to the SFA and SRA, respectively.

Figure 7.

The CL function for atoms belonging the SFA, SSA, and SRA at different temperatures.

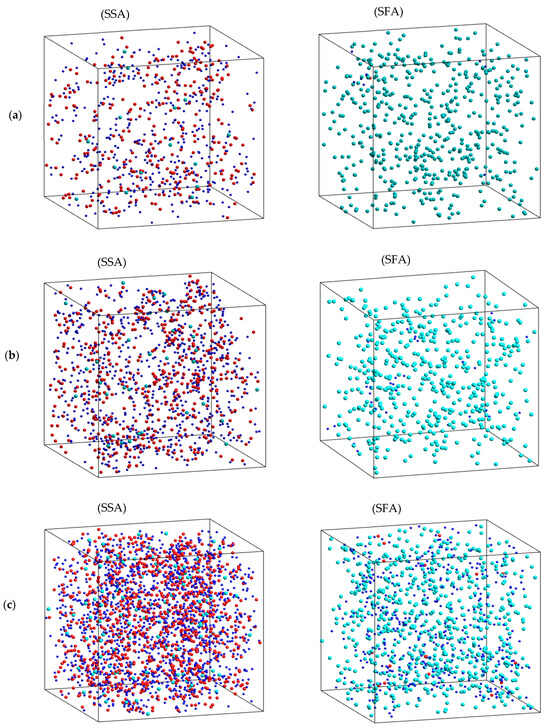

Clearly, these values are significantly larger than that of the SSA. With further increasing r to 3.00 ± 0.05 Å, the SFA and SRA appear as turning points, and then fCl(r) gradually decreases. The result demonstrates the heterogeneous spatial distribution of the fastest and slowest atoms in the Na2O∙3SiO2 network. The problem here is that we do not know whether the Na atoms are mainly distributed in the SFA. To investigate this, we considered the distribution of sets of the fastest and slowest atoms using a visual technique. Here, we considered two consecutive configurations at moments t and t + 2 ps. Then, the MSD was identified, and the SFA and SSA were therefore found. Figure 8 displays the distribution of SFA and SSA at 773, 1173, and 1573 K. As can be seen, the distributions of both the fastest and slowest atoms are not uniform. The SFA mainly includes Na atoms, while the SSA mainly includes Si and O atoms. This demonstrates that the dynamics of the atoms are heterogeneous, and the hopping of Na atoms is mainly distributed for diffusion pathways in Na2O∙3SiO2.

Figure 8.

The 5% distribution of the sets of slowest atoms (SSA) and fastest atoms (SFA): (a) 1573 K, (b) 1173 K, and (c) 773 K; the red ball is Si, the blue ball is O, and the green ball is Na.

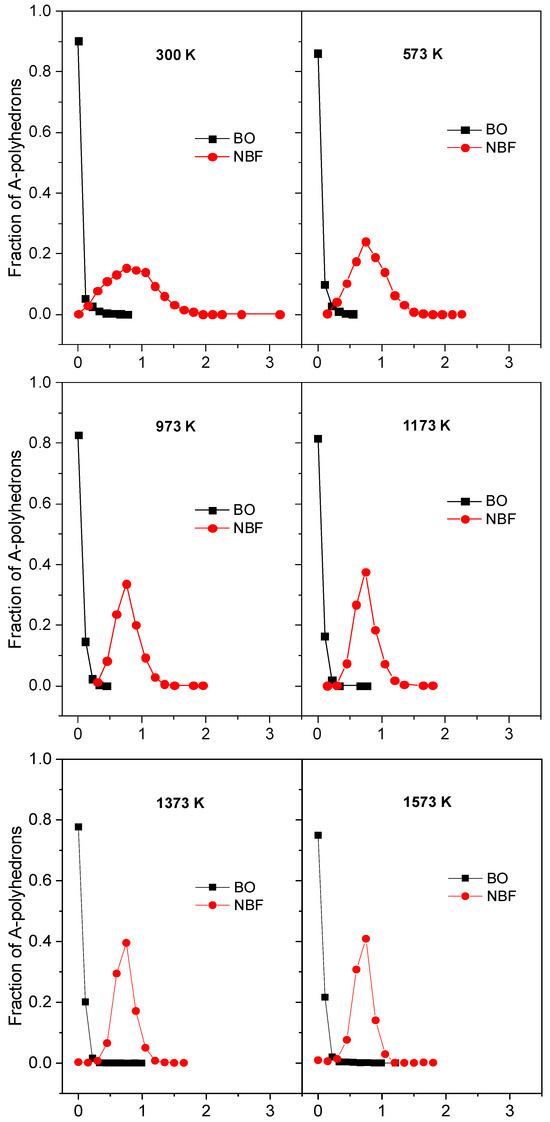

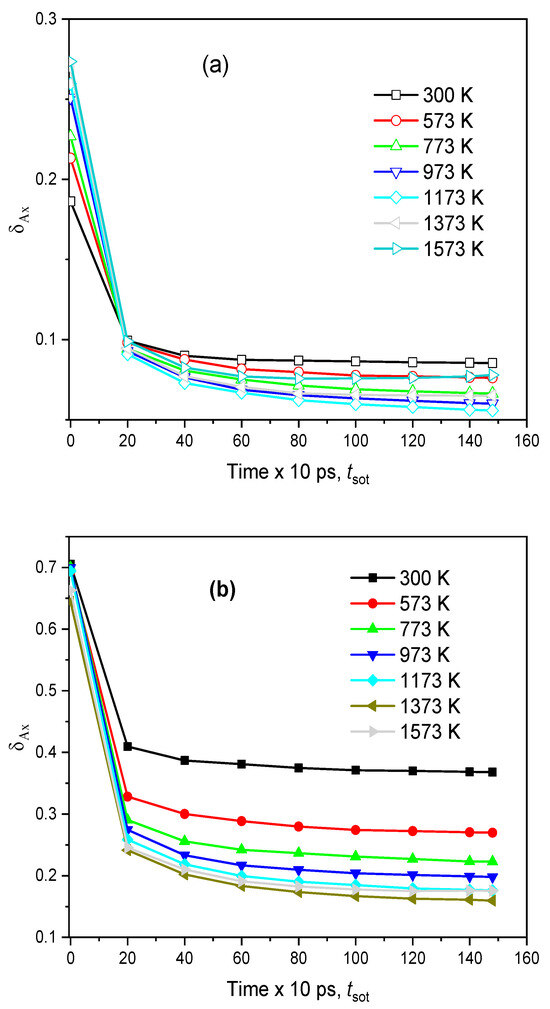

To investigate the diffusion pathway, we specified the number of BO- and NBF-polyhedrons as a function of <xA>, where <xA> is the mean number of Na atoms in the A-polyhedron for the time tsot. The distributions of the fraction mAx/mA and the time dependence of the deviation of those distributions, δAx, for the case tsot = 150 ps are plotted in Figure 9 and Figure 10. It can be seen that the curve for the NBF-polyhedrons possesses a pronounced peak at <xA> = 0.75 and spreads over a wide range, whereas the major BO-polyhedrons possess a small <xA>. As temperature increases, the curve for NBF spreads over a narrower range. This demonstrates that the diffusion pathway is composed of NBF-polyhedrons. With increasing tsot, the deviation, δAx, decreases quickly, and it approaches a smaller value at higher temperatures. This observation is understood as follows: under tsot, the average number of Na atoms in the ith A-polyhedron approaches <xAi>, which is proportional to

where ESi, kB, and T are the site energy, Boltzmann constant, and temperature, respectively.

Figure 9.

The fraction mAx/mA as a function of the average number of Na atoms in the A-polyhedron <xA> for 150 ps at different temperatures. Here, A denotes BO or NBF; mAx and mA denote the number of A-polyhedrons with <xA> and the total number of A-polyhedrons, respectively.

Figure 10.

The time dependence of the deviation, δAx, at different temperatures: (a)—BO and (b)—NBF.

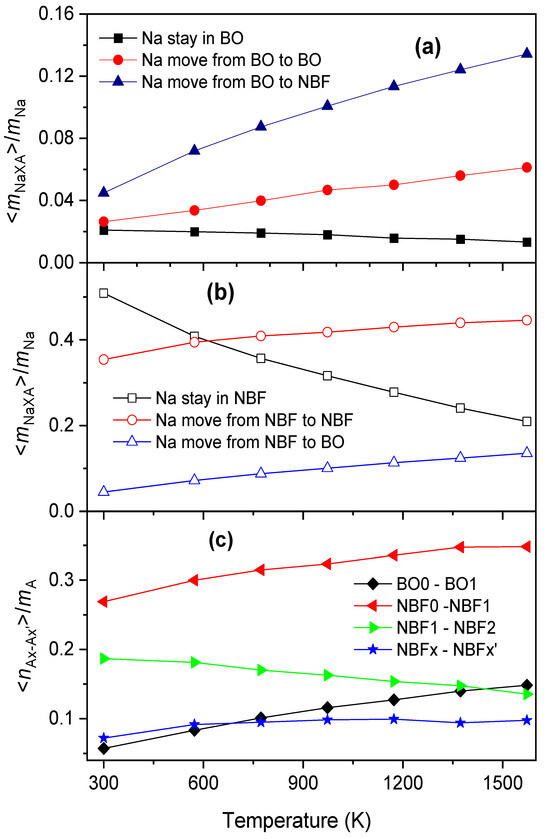

On the other hand, from Figure 9, the <xA> of BO is significantly smaller than that of NBF. This means that the site energy for a Na atom located in an NBF-polyhedron must be significantly smaller than that for a Na atom in a BO-polyhedron. In addition, <xA> varies over a wide range, indicating that Na has various energies, ESi. In fact, Na moves frequently between A-polyhedrons, so the average number of Na atoms in the ith polyhedron quickly approaches <xAi>, and δAx also decreases quickly with tsot. As temperature increases, the values of <xAi> for different A-polyhedrons are close to each other. This leads to δAx approaching a smaller value with increasing temperature (see Figure 10). Figure 11 displays the number of Na atoms staying in an A-polyhedron or moving from an A-polyhedron to another one within 2.0 ps. As expected, the number of Na atoms remaining monotonously decreases with increasing temperature.

Figure 11.

The temperature dependence of <mNaA>/mNa (a,b) and <mAx-Ax’>/mA (c). Here, <mNaA> is the average number of Na atoms staying in A-polyhedrons or moving from an A-polyhedron to another one within 2 ps; A is BO or NBF; mNa is the total number of Na atoms; <mAx-Ax’> is the average number of Ax → Ax’ transformations within 2 ps; and mA is the total number of A-polyhedrons.

Due to the movement of Na between O-polyhedrons, the system undergoes numerous Ax → Ax’ transformations. The average number of Ax → Ax’ transformations is plotted in Figure 10. As seen in Figure 10, there are a small number of BOx atoms undergoing the transformation BO0 ↔ BO1, which increases with temperature. Therefore, more Na atoms reside in BO-polyhedrons at higher temperatures, and Na atoms perform independent jumping in them. In the case of NBF-polyhedrons, the transformations NBF0 ↔ NBF1 and NBF1 ↔ NBF2 occur in the majority of polyhedrons. However, the system comprises a number of NBF-polyhedrons undergoing the transformation NBFx → NBFx’, where |x − x’| > 1. The number of such NBF-polyhedrons also increases with increasing temperature. We conclude that, unlike BO-polyhedrons, Na performs independent jumping and cooperative motion. Cooperative motion is realized in more NBF-polyhedrons at higher temperatures.

From the above explanation, we suggest that the diffusion constant for Na in Na2O∙3SiO2 may be written as follows:

where is the mean square distance between a site and its nearest neighbor, is the rate of Na atoms moving between O-polyhedrons, is the geometrical factor, and f is the correlation coefficient describing the forward–backward jumps of Na atoms [32,33].

3. Materials and Methods

The simulation was carried out for Na2O∙3SiO2 at ambient pressure over a temperature range of 300–1573 K. The sample was made of 9996 atoms, including 5831 O atoms, 2499 Si atoms, and 1666 Na atoms. All simulation runs were performed using MXDORTO code [40]. We used the interaction potentials, consisting of two-body and three-body terms, which can quite reliably reproduce the structure and dynamics of sodium silicate. The density was adopted from that of a real sodium trisilicate glass of 2.4323 g/cm3 [41]. A complete description of these potentials can be found elsewhere [29,42]. The pair potential has the following form:

The potential parameters are listed in Table 3. Note that the three-body term relating to the Si-O-Si angle has the following form:

where f is the force constant; θkij is the angle among atoms k–i–j; and θ0, gr, and rm are the parameters for adjusting the angular part of covalent bonds. The partial charges for the Si and O atoms are calculated as follows: ZSi.ZO = −2.5 and 2ZNa + 3 ZSi + 7 ZO = 0, where ZNa is fixed at 1.0.

Table 3.

The interatomic potential parameters.

The pair radial distribution function (PRDF) for BO and NBF is characteristic of their local microstructure. Here, BO, NBO, and FO are the types of oxygen which are bounded, respectively, with two, one, and no Si atoms; NBF is denoted either as NBO or FO. Overall, the status of O (BO, NBO, and FO) was mostly unchanged during the simulation. Only a few BO ↔ NBF transformations were detected at temperatures of 300, 973, and 1373 K.

In this work, the simple nanoarchitectonics of atoms include O-polyhedrons and Si-polyhedrons; bridging oxygen (BO)-, non-bridging oxygen (NBO)-, and free oxygen (FO)-polyhedrons; the group of Na in NBO- and FO-polyhedrons; and the fastest, slowest, and random atoms. The visualization of MD data was carried out to study the structural properties and diffusion pathway of Na atoms in sodium trisilicate [43]. In this context, we suppose that the simulation box is fully filled by O- and Si-polyhedrons, and Na is placed inside these polyhedrons. In this work, the A-polyhedron is denoted as the A-centered polyhedron, where A is the Si, BO, or NBF; we also use the Ax-polyhedron, where x is the number of Na atoms in the A-polyhedron. For instance, NBF1 represents the NBF-polyhedron containing one Na atom, respectively. During the simulation process, we found that Na atoms were not placed in fixed polyhedrons, but they frequently moved from one to other polyhedrons. To clarify this effect, we observed A-polyhedrons in configurations separated by 2 ps. The local Na density in the vicinity of an O or Si atom was quantified by the mean number of Na atoms in the A-polyhedron, which is called <xA>. We determined Ax for configurations within a span of time tsot, and then <xA> was obtained by averaging x over those polyhedrons. The value of <xA> depends on tsot and approaches a finite value as tsot → ∞. Consider two consecutive configurations at moments t and t + 2 ps. We specified the number of Na atoms staying in the A-polyhedron and also the number of Na atoms moving to other polyhedrons. In this way, we detected Ax → Ax’ transformations. For instance, BO1 at moment t transforms to BO0 at moment t + 2 ps if one Na atom leaves the given BO-polyhedron to enter another O-polyhedron. The number of Ax → Ax’ transformations characterizes sodium’s migration in sodium silicate. To investigate the microstructure at an atomic level, MATLAB2018 software, code by N.V. Hong (Hanoi University of Science and Technology, VIET NAM) was used to visualize the MD data in 3D space.

4. Conclusions

In this study, using nanoarchitectonics and an MD simulation, the structural properties and diffusion pathway of alkali in sodium silicate (Na2O∙3SiO2) were considered. The obtained results suggest that most Na atoms are located around NBF. Si-polyhedrons do not contain Na, and O-polyhedrons either are empty or contain Na atoms. This demonstrates that Na atoms are concentrated in a relatively small subspace. The motion of Na atoms includes the displacement between two neighboring NBF-polyhedrons, which describes the channel for Na diffusion. In addition, the doped Na ions break the Si-O linkages, which leads to the generation of non-bridging oxygen (NBO) in Na2O∙3SiO2.

Na2O∙3SiO2 undergoes numerous transformations, such as NBF0 ↔ NBF1, NBF1 ↔ NBF2, and BO0 ↔ BO1. The dynamics in Na2O∙3SiO2 are mainly distributed through the hopping of Na atoms; namely, Na atoms carry out independent hopping when transformations occur. We propose that the diffusion of Na atoms in Na2O∙3SiO2 is realized through independent hopping in BO- and NBF-polyhedrons and through cooperative motion in NBF-polyhedrons.

This new diffusion model is proposed to give insight into the diffusion pathway of alkali in sodium silicate systems. These results provide a foundation for future experimental research aimed at fabricating materials for industrial applications, ceramics, metallurgy, and glass technologies, as well as understanding the fundamentals of minerals. The findings revealed in this study are expected to contribute to future studies on new materials with varying temperature and pressure conditions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.H.K.; methodology, G.T.T.T.; software, P.H.K.; validation G.T.T.T.; formal analysis, P.H.K.; investigation, G.T.T.T.; resources, G.T.T.T.; data curation, P.H.K.; writing—original draft, G.T.T.T.; writing—review and editing, P.H.K.; supervision, G.T.T.T.; project administration, P.H.K.; funding acquisition, P.H.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Thai Nguyen University and Thai Nguyen University of Education under grant number ĐH2023-TN04-04.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the articl, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Fumiya Noritake (Computational Astrophysics Laboratory, RIKEN, Japan) for supporting the sodium silicate models and P.K. Hung (Hanoi University of Science and Technology, VIET NAM) for many enlightening discussions on the problems discussed here.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Fábián, M.; Jóvári, P.; Sváb, E.; Mészáros, G.; Proffen, T.; Veress, E. Network structure of 0.7SiO2-0.3Na2O glass from neutron and X-ray diffraction and RMC modelling. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2007, 19, 335209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozzi, R.L.; Warren, B.E. The structure of vitreous silica. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 1969, 2, 164–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benmore, C.J.; Weber, J.K.R.; Wilding, M.C.; Du, J.; Parise, J.B. Temperature-dependent structural heterogeneity in calcium silicate liquids. Phys. Rev. B 2010, 82, 224202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, Y.; Takumi, Y.; Atsunobu, M.; Hiroyuki, I.; Koji, O.; Shinji, K. Structural change of Na2O-doped SiO2 glasses by melting. J. Ceram. Soc. Jpn. 2016, 124, 717–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Weiying, S.; Morten, M.S.; John, C.M.; Mathieu, B. Quantifying the internal stress in over-constrained glasses by molecular dynamics simulations. J. Non-Cryst. Solids X 2019, 1, 100013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesbitt, H.W.; Henderson, G.S.; Bancroft, G.M.; Ho, R. Experimental evidence for Na coordination to bridging oxygen in Na-silicate glasses: Implications for spectroscopic studies and for the modified random network model. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2015, 409, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidenko, A.O.; Sokol’skii, V.E.; Roik, A.S.; Goncharov, I.A. Structural study of sodium silicate glasses and melts. Inorg. Mater. 2014, 50, 1289–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Guerette, M.; Scannell, G.; Huang, L. In-situ high temperature Raman and Brillouin light scattering studies of sodium silicate glasses. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2012, 358, 3418–3426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, W.; Greaves, G.N.; Gillan, M.J. Computer simulation of Na disilicate glass. J. Chem. Phys. 1995, 103, 3091–3097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, N.V.; Dung, M.V.; Hung, P.K.; Van, T.B.; Vinh, L.T. Spatial distribution of cations through Voronoi polyhedrons and their exchange between polyhedrons in sodium silicate liquids. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2021, 566, 120898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabraoui, H.; Achhal, E.M.; Hasnaoui, A.; Garden, J.L.; Vaills, Y.; Ouaskit, S. Molecular dynamics simulation of thermodynamic and structural properties of silicate glass: Effect of the alkali oxide modifiers. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2016, 448, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mountjoy, G.; Al-Hasni, B.M.; Storey, C. Structural organisation in oxide glasses from molecular dynamics modelling. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2011, 357, 2522–2529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojovan, M.I. The Modified Random Network (MRN) Model within the Configuron Percolation Theory (CPT) of Glass Transition. Ceramics 2021, 4, 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabraoui, H.; Vaills, Y.; Hasnaoui, A.; Badawi, M.; Ouaskit, S. Effect of Na oxide modifier on structural and elastic properties of silicate glass. J. Phys. Chem. B 2016, 120, 13193–13205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noritake, F. Structural transformations in sodium silicate liquids under pressure: New static and dynamic structure analyses. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2017, 473, 102–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voigtmann, T.; Horbach, J. Slow dynamics in ion-conducting sodium silicate melts: Simulation and mode-coupling theory. Europhys. Lett. 2006, 74, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, P.K.; Noritake, F.; San, L.T.; Van, T.B. Study of diffusion and local structure of sodium-silicate liquid: The molecular dynamic simulation. Eur. Phys. J. B 2017, 90, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, Y.P.; King, T.B. Self-diffusion of sodium in sodium silicate liquids. Trans. Metall. Soc. AIME 1967, 239, 1701. [Google Scholar]

- Braedt, M.; Frischat, G.H. Sodium self diffusion in glasses and melts of the system Na2O-Rb2O-SiO2. Phys. Chem. Glas. 1988, 29, 214–218. [Google Scholar]

- Knoche, R.; Dingwell, D.B.; Seifert, F.A.; Webb, S.L. Non-linear properties of supercooled liquids in the system Na2O∙SiO2. Chem. Geol. 1994, 116, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, A.; Horbach, J.; Kob, W.; Kargl, F.; Schober, H. Channel formation and intermediate range order in sodium silicate melts and glasses. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2004, 93, 027801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kargl, F.; Weis, H.; Unruh, T.; Meyer, A. Self diffusion in liquid aluminium. In J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2012, 340, 012077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philippe, J.; Kob, W.; Jullien, R. Channel diffusion of Na in a silicate glass. Phys. Rev. B 2001, 64, 134303. [Google Scholar]

- Van, T.B.; Hung, P.K.; Vinh, L.T.; Ha, N.T.T.; San, L.T.; Noritake, F. Network cavity, spatial distribution of Na and dynamics in sodium silicate melts. J. Mater. Sci. 2020, 55, 2870–2880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantinou, K.; Duffy, D.M.; Shluger, A.L. Structure and luminescence of intrinsic localized states in sodium silicate glasses. Phys. Rev. B 2016, 94, 174202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greaves, G.N. Structure and ionic transport in disordered silicates. Mineral. Mag. 2000, 64, 441–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greaves, G.N.; Sen, S. Inorganic glasses, glass-forming liquids and amorphizing solids. Adv. Phys. 2007, 56, 1–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauchy, M.; Micoulaut, M. From pockets to channels: Density-controlled diffusion in sodium silicates. Phys. Rev. B 2011, 83, 184118. [Google Scholar]

- Noritake, F.; Katsuyuki, K.; Takashi, Y.; Eiichi, T. Molecular dynamics simulation and electrical conductivity measurement of Na2O∙3SiO2 melt under high pressure; relationship between its structure and properties. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2012, 358, 3109–3118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunyer, E.; Philippe, J.; Rémi, J. Characterization of channel diffusion in a Na tetrasilicate glass via molecular-dynamics simulations. Phys. Rev. B 2002, 65, 214203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horbach, J.; Walter, K.; Kurt, B. Structural and dynamical properties of sodium silicate melts: An investigation by molecular dynamics computer simulation. Chem. Geol. 2001, 174, 87–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cormack, A.N.; Du, J.; Zeitler, T.R. Alkali ion migration mechanisms in silicate glasses probed by molecular dynamics simulations. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2002, 4, 3193–3197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cormack, A.N.; Du, J.; Zeitler, T.R. Sodium ion migration mechanisms in silicate glasses probed by molecular dynamics simulations. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2003, 323, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noritake, F. Diffusion mechanism of network-forming elements in silicate liquids. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2021, 553, 120512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habasaki, J.; Yasuaki, H. Molecular dynamics study of the mechanism of ion transport in lithium silicate glasses: Characteristics of the potential energy surface and structures. Phys. Rev. B 2004, 69, 144207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morab, S.; Sundaram, M.M.; Pivrikas, A. Influence of traps and Lorentz Force on charge transport in organic semiconductors. Materials 2023, 16, 4691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Yen, N.; Plan, E.L.V.M.; Kien, P.H.; Nguyen, A.T.; Van Hong, N.; Phan, H. Topological structural analysis and dynamical properties in MgSiO3 liquid under compression. Eur. Phys. J. B 2022, 95, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, P.K.; Vinh, L.T.; Hong, N.V.; Thu Ha, N.T.; Toshiaki, I. Two-domain structure and dynamics heterogeneity in a liquid SiO2. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2018, 484, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, N.T.T.; Hong, N.V.; Hung, P.K. Distribution of Na and dynamical heterogeneity in sodium silicate liquid. Int. J. Mod. Phys. B 2019, 33, 1950013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakuma, H.; Kawamura, K. Structure and dynamics of water on muscovite mica surfaces. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2009, 73, 4100–4110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaze, F.W.; Young, J.C.; Finn, A.N. The density of some soda-lime-silica glasses as a function of the composition. Bur. Stand. J. Res. 1932, 9, 799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noritake, F.; Naito, S. Mechanism of mixed alkali effect in silicate glass/liquid: Pathway and network analysis. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2023, 610, 122321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariga, K. Nanoarchitectonics: Method for everything in material science. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 2023, 97, uoad001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).