Mycobacterium tuberculosis in a Trap: The Role of Neutrophil Extracellular Traps in Tuberculosis

Abstract

1. Introduction

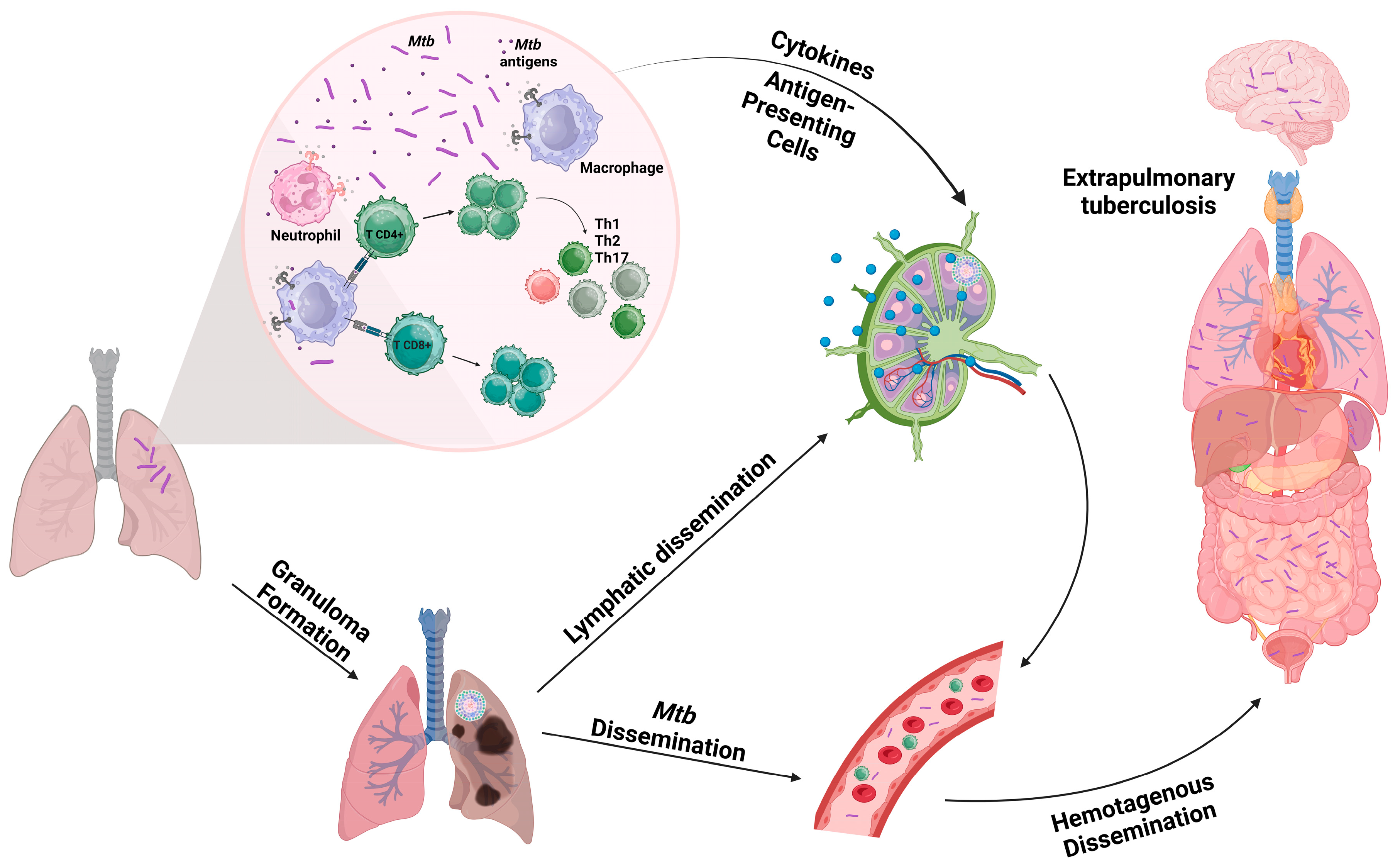

2. Tuberculosis

3. Neutrophils

4. Neutrophil Extracellular Trap in Tuberculosis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Garrido-Cardenas, J.A.; de Lamo-Sevilla, C.; Cabezas-Fernández, M.T.; Manzano-Agugliaro, F.; Martínez-Lirola, M. Global tuberculosis research and its future prospects. Tuberculosis 2020, 121, 101917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nogueira, B.M.F.; Krishnan, S.; Barreto-Duarte, B.; Araújo-Pereira, M.; Queiroz, A.T.L.; Ellner, J.J.; Salgame, P.; Scriba, T.J.; Sterling, T.R.; Gupta, A.; et al. Diagnostic biomarkers for active tuberculosis: Progress and challenges. EMBO Mol. Med. 2022, 14, e14088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dicks, K.V.; Stout, J.E. Molecular Diagnostics for Mycobacterium tuberculosis Infection. Annu. Rev. Med. 2019, 70, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Lucena, L.A.; da Silva Dantas, G.B.; Carneiro, T.V.; Lacerda, H.G. Factors Associated with the Abandonment of Tuberculosis Treatment in Brazil: A Systematic Review. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 2023, 56, e0155-2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, P. Challenges & Solutions for Recent Advancements in Multi-Drugs Resistance Tuberculosis: A Review. Microbiol. Insights 2023, 16, 117863612311524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Saavedra-Avila, N.A.; Tiwari, S.; Porcelli, S.A. A century of BCG vaccination: Immune mechanisms, animal models, non-traditional routes and implications for COVID-19. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 959656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pai, M.; Kasaeva, T.; Swaminathan, S. Covid-19’s Devastating Effect on Tuberculosis Care-A Path to Recovery. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 1490–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization (WHO) Global Tuberculosis Report 2022; Geneva World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022.

- Kanabalan, R.D.; Lee, L.J.; Lee, T.Y.; Chong, P.P.; Hassan, L.; Ismail, R.; Chin, V.K. Human tuberculosis and Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex: A review on genetic diversity, pathogenesis and omics approaches in host biomarkers discovery. Microbiol. Res. 2021, 246, 126674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scriba, T.J.; Coussens, A.K.; Fletcher, H.A. Human Immunology of Tuberculosis. Microbiol. Spectr. 2016, 4, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borkute, R.R.; Woelke, S.; Pei, G.; Dorhoi, A. Neutrophils in Tuberculosis: Cell Biology, Cellular Networking and Multitasking in Host Defense. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liew, P.X.; Kubes, P. The Neutrophil’s Role During Health and Disease. Physiol. Rev. 2019, 99, 1223–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burn, G.L.; Foti, A.; Marsman, G.; Patel, D.F.; Zychlinsky, A. The Neutrophil. Immunity 2021, 54, 1377–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papayannopoulos, V. Neutrophil extracellular traps in immunity and disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2018, 18, 134–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schauer, C.; Janko, C.; Munoz, L.E.; Zhao, Y.; Kienhöfer, D.; Frey, B.; Lell, M.; Manger, B.; Rech, J.; Naschberger, E.; et al. Aggregated neutrophil extracellular traps limit inflammation by degrading cytokines and chemokines. Nat. Med. 2014, 20, 511–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thanabalasuriar, A.; Kubes, P. Rise and shine: Open your eyes to produce anti-inflammatory NETs. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2019, 105, 1083–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Rizo, V.; Martínez-Guzmán, M.A.; Iñiguez-Gutierrez, L.; García-Orozco, A.; Alvarado-Navarro, A.; Fafutis-Morris, M. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps and Its Implications in Inflammation: An Overview. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, A.; Libby, P.; Soehnlein, O.; Aramburu, I.V.; Papayannopoulos, V.; Silvestre-Roig, C. Neutrophil extracellular traps: From physiology to pathology. Cardiovasc. Res. 2022, 118, 2737–2753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loddenkemper, R.; Murray, J.F. History of Tuberculosis. In Essential Tuberculosis; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 3–9. [Google Scholar]

- Guerra-De-Blas, P.D.C.; Torres-González, P.; Bobadilla-Del-Valle, M.; Sada-Ovalle, I.; Ponce-De-León-Garduño, A.; Sifuentes-Osornio, J. Potential Effect of Statins on Mycobacterium tuberculosis Infection. J. Immunol. Res. 2018, 2018, 7617023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pai, M.; Behr, M.A.; Dowdy, D.; Dheda, K.; Divangahi, M.; Boehme, C.C.; Ginsberg, A.; Swaminathan, S.; Spigelman, M.; Getahun, H.; et al. Tuberculosis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2016, 2, 16076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowdy, D.W.; Raviglione, M.C. Basic and Descriptive Epidemiology of Tuberculosis. In Essential Tuberculosis; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 29–36. [Google Scholar]

- Campaniço, A.; Harjivan, S.G.; Warner, D.F.; Moreira, R.; Lopes, F. Addressing Latent Tuberculosis: New Advances in Mimicking the Disease, Discovering Key Targets, and Designing Hit Compounds. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferluga, J.; Yasmin, H.; Al-Ahdal, M.N.; Bhakta, S.; Kishore, U. Natural and trained innate immunity against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Immunobiology 2020, 225, 151951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simmons, J.D.; Stein, C.M.; Seshadri, C.; Campo, M.; Alter, G.; Fortune, S.; Schurr, E.; Wallis, R.S.; Churchyard, G.; Mayanja-Kizza, H.; et al. Immunological mechanisms of human resistance to persistent Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2018, 18, 575–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warner, D.F.; Koch, A.; Mizrahi, V. Diversity and disease pathogenesis in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Trends Microbiol. 2015, 23, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruchfeld, J.; Forsman, L.D.; Fröberg, G.; Niward, K. Extrapulmonary Tuberculosis. In Essential Tuberculosis; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 259–266. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization Global Tuberculosis Report 2019; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 283.

- Rodriguez-Takeuchi, S.Y.; Renjifo, M.E.; Medina, F.J. Extrapulmonary Tuberculosis: Pathophysiology and Imaging Findings. Radiographics 2019, 39, 2023–2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, R.J.; Rohlwink, U.; Misra, U.K.; Van Crevel, R.; Mai, N.T.H.; Dooley, K.E.; Caws, M.; Figaji, A.; Savic, R.; Solomons, R.; et al. Tuberculous meningitis. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2017, 13, 581–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sia, J.K.; Rengarajan, J. Immunology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis Infections. Microbiol. Spectr. 2019, 7, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S. Pathogenesis, immunology, and diagnosis of latent Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Clin. Dev. Immunol. 2011, 2011, 814943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jellinger, K.A.; Bustin, S.; Alsayed, S.S.R.; Gunosewoyo, H. Tuberculosis: Pathogenesis, Current Treatment Regimens and New Drug Targets. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 5202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, P.; Grigsby, S.J.; Philips, J.A. Immune evasion and provocation by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2022, 20, 750–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehlers, S.; Schaible, U.E. The granuloma in tuberculosis: Dynamics of a host-pathogen collusion. Front. Immunol. 2012, 3, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingo-Gonzalez, R.; Prince, O.; Cooper, A.; Khader, S.A. Cytokines and Chemokines in Mycobacterium tuberculosis Infection. Microbiol. Spectr. 2016, 4, 4–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernst, J.D. The immunological life cycle of tuberculosis. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2012, 12, 581–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, D.; Martineau, A.R. Inflammation-mediated tissue damage in pulmonary tuberculosis and host-directed therapeutic strategies. Semin. Immunol. 2023, 65, 101672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasindran, S.J.; Torrelles, J.B. Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Infection and Inflammation: What is Beneficial for the Host and for the Bacterium? Front. Microbiol. 2011, 2, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Randall, P.J.; Hsu, N.J.; Quesniaux, V.; Ryffel, B.; Jacobs, M. Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection of the ‘non-classical immune cell’. Immunol. Cell Biol. 2015, 93, 789–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baykan, A.H.; Sayiner, H.S.; Aydin, E.; Koc, M.; Inan, I.; Erturk, S.M. Extrapulmonary tuberculosıs: An old but resurgent problem. Insights Imaging 2022, 13, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moule, M.G.; Cirillo, J.D. Mycobacterium tuberculosis Dissemination Plays a Critical Role in Pathogenesis. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 517605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopalaswamy, R.; Dusthackeer, V.N.A.; Kannayan, S.; Subbian, S. Extrapulmonary Tuberculosis—An Update on the Diagnosis, Treatment and Drug Resistance. J. Respir. 2021, 1, 141–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loddenkemper, R.; Lipman, M.; Zumla, A. Clinical Aspects of Adult Tuberculosis. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2016, 6, a017848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, H.A.; Forrester, L.; Kaldor, C.D.; Dickerhof, N.; Hampton, M.B. Antimicrobial Activity of Neutrophils Against Mycobacteria. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 782495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naumenko, V.; Turk, M.; Jenne, C.N.; Kim, S.J. Neutrophils in viral infection. Cell Tissue Res. 2018, 371, 505–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavalcante-Silva, L.H.A.; Carvalho, D.C.M.; de Almeida Lima, É.; Galvão, J.G.F.M.; de França da Silva, J.S.; de Sales-Neto, J.M.; Rodrigues-Mascarenhas, S. Neutrophils and COVID-19: The road so far. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2021, 90, 107233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosales, C. Neutrophil: A Cell with Many Roles in Inflammation or Several Cell Types? Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galani, I.E.; Andreakos, E. Neutrophils in viral infections: Current concepts and caveats. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2015, 98, 557–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urban, C.F.; Backman, E. Eradicating, retaining, balancing, swarming, shuttling and dumping: A myriad of tasks for neutrophils during fungal infection. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2020, 58, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newburger, P.E. Autoimmune and other acquired neutropenias. Hematol. Am. Soc. Hematol. Educ. Progr. 2016, 2016, 38–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Dikshit, M. Metabolic Insight of Neutrophils in Health and Disease. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, H.B.; Deniset, J.F.; Kubes, P. Neutrophils in homeostasis and tissue repair. Int. Immunol. 2022, 34, 399–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomino-Segura, M.; Sicilia, J.; Ballesteros, I.; Hidalgo, A. Strategies of neutrophil diversification. Nat. Immunol. 2023, 24, 575–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, A.; Chilvers, E.R.; Summers, C.; Koenderman, L. The Neutrophil Life Cycle. Trends Immunol. 2019, 40, 584–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grieshaber-Bouyer, R.; Radtke, F.A.; Cunin, P.; Stifano, G.; Levescot, A.; Vijaykumar, B.; Nelson-Maney, N.; Blaustein, R.B.; Monach, P.A.; Nigrovic, P.A.; et al. The neutrotime transcriptional signature defines a single continuum of neutrophils across biological compartments. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 2856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ley, K.; Hoffman, H.M.; Kubes, P.; Cassatella, M.A.; Zychlinsky, A.; Hedrick, C.C.; Catz, S.D. Neutrophils: New insights and open questions. Sci. Immunol. 2018, 3, eaat4579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deniset, J.F.; Kubes, P. Neutrophil heterogeneity: Bona fide subsets or polarization states? J. Leukoc. Biol. 2018, 103, 829–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cassatella, M.A.; Östberg, N.K.; Tamassia, N.; Soehnlein, O. Biological Roles of Neutrophil-Derived Granule Proteins and Cytokines. Trends Immunol. 2019, 40, 648–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillipson, M.; Kubes, P. The Healing Power of Neutrophils. Trends Immunol. 2019, 40, 635–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawai, T.; Akira, S. The role of pattern-recognition receptors in innate immunity: Update on toll-like receptors. Nat. Immunol. 2010, 11, 373–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netea, M.G.; Balkwill, F.; Chonchol, M.; Cominelli, F.; Donath, M.Y.; Giamarellos-Bourboulis, E.J.; Golenbock, D.; Gresnigt, M.S.; Heneka, M.T.; Hoffman, H.M.; et al. A guiding map for inflammation. Nat. Immunol. 2017, 18, 826–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medzhitov, R. Inflammation 2010: New Adventures of an Old Flame. Cell 2010, 140, 771–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolaczkowska, E.; Kubes, P. Neutrophil recruitment and function in health and inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2013, 13, 159–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatfield, S.M.; Thieblemont, N.; Witko-Sarsat, V. Expanding Neutrophil Horizons: New Concepts in Inflammation. J. Innate Immun. 2018, 10, 422–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, W.A. Mechanisms of Leukocyte Transendothelial Migration. Annu. Rev. Pathol. Mech. Dis. 2011, 6, 323–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyun, Y.; Hong, C. Deep insight into neutrophil trafficking in various organs. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2017, 102, 617–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powell, D.R.; Huttenlocher, A. Neutrophils in the Tumor Microenvironment. Trends Immunol. 2016, 37, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, F.; Zhao, S.; Yu, B.; Chen, Y.M.; Wang, W.; Song, Z.G.; Hu, Y.; Tao, Z.W.; Tian, J.H.; Pei, Y.Y.; et al. A new coronavirus associated with human respiratory disease in China. Nature 2020, 579, 265–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hilda, J.N.; Das, S.; Tripathy, S.P.; Hanna, L.E. Role of neutrophils in tuberculosis: A bird’s eye view. Innate Immun. 2020, 26, 240–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panteleev, A.V.; Nikitina, I.Y.; Burmistrova, I.A.; Kosmiadi, G.A.; Radaeva, T.V.; Amansahedov, R.B.; Sadikov, P.V.; Serdyuk, Y.V.; Larionova, E.E.; Bagdasarian, T.R.; et al. severe tuberculosis in humans correlates best with neutrophil abundance and lymphocyte deficiency and does not correlate with antigen-specific CD4 T-cell response. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, D.M.; Bandara, A.K.; Packe, G.E.; Barker, R.D.; Wilkinson, R.J.; Griffiths, C.J.; Martineau, A.R. Neutrophilia independently predicts death in tuberculosis. Eur. Respir. J. 2013, 42, 1752–1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Meer, A.J.; Zeerleder, S.; Blok, D.C.; Kager, L.M.; Lede, I.O.; Rahman, W.; Afroz, R.; Ghose, A.; Visser, C.E.; Zahed, A.S.M.; et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps in patients with pulmonary tuberculosis. Respir. Res. 2017, 18, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poh, X.Y.; Loh, F.K.; Friedland, J.S.; Ong, C.W.M. Neutrophil-Mediated Immunopathology and Matrix Metalloproteinases in Central Nervous System-Tuberculosis. Front. Immunol. 2022, 12, 788976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcos, J.; Diangelo, L.E.; Scordo, J.M.; Sasindran, S.J.; Moliva, J.I.; Turner, J.; Torrelles, J.B. Lung Mucosa Lining Fluid Modification of Mycobacterium tuberculosis to Reprogram Human Neutrophil Killing Mechanisms. J. Infect. Dis. 2015, 212, 948–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopal, R.; Monin, L.; Torres, D.; Slight, S.; Mehra, S.; McKenna, K.C.; Junecko, B.A.F.; Reinhart, T.A.; Kolls, J.; Báez-Saldańa, R.; et al. S100A8/A9 proteins mediate neutrophilic inflammation and lung pathology during tuberculosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2013, 188, 1137–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lovewell, R.R.; Baer, C.E.; Mishra, B.B.; Smith, C.M.; Sassetti, C.M. Granulocytes act as a niche for Mycobacterium tuberculosis growth. Mucosal Immunol. 2020, 14, 229–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinkmann, V.; Reichard, U.; Goosmann, C.; Fauler, B.; Uhlemann, Y.; Weiss, D.S.; Weinrauch, Y.; Zychlinsky, A. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps Kill Bacteria. Science 2004, 303, 1532–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brinkmann, V. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps in the Second Decade. J. Innate Immun. 2018, 10, 414–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narasaraju, T.; Tang, B.M.; Herrmann, M.; Muller, S.; Chow, V.T.K.; Radic, M. Neutrophilia and NETopathy as Key Pathologic Drivers of Progressive Lung Impairment in Patients With COVID-19. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hahn, J.; Knopf, J.; Maueröder, C.; Kienhöfer, D.; Leppkes, M.; Herrmann, M. Neutrophils and neutrophil extracellular traps orchestrate initiation and resolution of inflammation. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2016, 34, 6–8. [Google Scholar]

- Jo, A.; Kim, D.W. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps in Airway Diseases: Pathological Roles and Therapeutic Implications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 5034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruschi, M.; Petretto, A.; Santucci, L.; Vaglio, A.; Pratesi, F.; Migliorini, P.; Bertelli, R.; Lavarello, C.; Bartolucci, M.; Candiano, G.; et al. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps protein composition is specific for patients with Lupus nephritis and includes methyl-oxidized αenolase (methionine sulfoxide 93). Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 7934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, E.F.; Herzig, A.; Krüger, R.; Muth, A.; Mondal, S.; Thompson, P.R.; Brinkmann, V.; von Bernuth, H.; Zychlinsky, A. Diverse stimuli engage different neutrophil extracellular trap pathways. Elife 2017, 6, e24437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, T.A.; Abed, U.; Goosmann, C.; Hurwitz, R.; Schulze, I.; Wahn, V.; Weinrauch, Y.; Brinkmann, V.; Zychlinsky, A. Novel cell death program leads to neutrophil extracellular traps. J. Cell Biol. 2007, 176, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakkim, A.; Fuchs, T.A.; Martinez, N.E.; Hess, S.; Prinz, H.; Zychlinsky, A.; Waldmann, H. Activation of the Raf-MEK-ERK pathway is required for neutrophil extracellular trap formation. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2011, 7, 75–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, P.; Li, M.; Lindberg, M.R.; Kennett, M.J.; Xiong, N.; Wang, Y. PAD4 is essential for antibacterial innate immunity mediated by neutrophil extracellular traps. J. Exp. Med. 2010, 207, 1853–1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sollberger, G.; Choidas, A.; Burn, G.L.; Habenberger, P.; Di Lucrezia, R.; Kordes, S.; Menninger, S.; Eickhoff, J.; Nussbaumer, P.; Klebl, B.; et al. Gasdermin D plays a vital role in the generation of neutrophil extracellular traps. Sci. Immunol. 2018, 3, eaar6689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porto, B.N.; Stein, R.T. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps in Pulmonary Diseases: Too Much of a Good Thing? Front. Immunol. 2016, 7, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dang, G.; Cui, Y.; Wang, L.; Li, T.; Cui, Z.; Song, N.; Chen, L.; Pang, H.; Liu, S. Extracellular Sphingomyelinase Rv0888 of Mycobacterium tuberculosis Contributes to Pathological Lung Injury of Mycobacterium smegmatis in Mice via Inducing Formation of Neutrophil Extracellular Traps. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yipp, B.G.; Kubes, P. NETosis: How vital is it? Blood 2013, 122, 2784–2794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiroki, C.H.; Toller-Kawahisa, J.E.; Fumagalli, M.J.; Colon, D.F.; Figueiredo, L.T.M.; Fonseca, B.A.L.D.; Franca, R.F.O.; Cunha, F.Q. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps Effectively Control Acute Chikungunya Virus Infection. Front. Immunol. 2020, 10, 3108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban, C.F.; Nett, J.E. Neutrophil extracellular traps in fungal infection. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2019, 89, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimarães-Costa, A.B.; Nascimento, M.T.C.; Froment, G.S.; Soares, R.P.P.; Morgado, F.N.; Conceição-Silva, F.; Saraiva, E.M. Leishmania amazonensis promastigotes induce and are killed by neutrophil extracellular traps. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 6748–6753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Kichik, V.; Mondragón-Flores, R.; Mondragón-Castelán, M.; Gonzalez-Pozos, S.; Muñiz-Hernandez, S.; Rojas-Espinosa, O.; Chacón-Salinas, R.; Estrada-Parra, S.; Estrada-García, I. Neutrophil extracellular traps are induced by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Tuberculosis 2009, 89, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filio-Rodríguez, G.; Estrada-García, I.; Arce-Paredes, P.; Moreno-Altamirano, M.M.; Islas-Trujillo, S.; Ponce-Regalado, M.D.; Rojas-Espinosa, O. In vivo induction of neutrophil extracellular traps by Mycobacterium tuberculosis in a guinea pig model. Innate Immun. 2017, 23, 625–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hahn, S.; Giaglis, S.; Chowdury, C.S.; Hösli, I.; Hasler, P. Modulation of neutrophil NETosis: Interplay between infectious agents and underlying host physiology. Semin. Immunopathol. 2013, 35, 439–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, K.; Nakayama, H.; Sasaki, S.; Takahashi, K.; Iwabuchi, K. Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex promote release of pro-inflammatory enzymes matrix metalloproteinases by inducing neutrophil extracellular trap formation. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 5181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendoza-Aguilar, M.D.; Arce-Paredes, P.; Aquino-Vega, M.; Rodríguez-Martínez, S.; Rojas-Espinosa, O. Fate of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in peroxidase-loaded resting murine macrophages. Int. J. Mycobacteriol. 2013, 2, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stephan, A.; Batinica, M.; Steiger, J.; Hartmann, P.; Zaucke, F.; Bloch, W.; Fabri, M. LL37:DNA complexes provide antimicrobial activity against intracellular bacteria in human macrophages. Immunology 2016, 148, 420–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braian, C.; Hogea, V.; Stendahl, O. Mycobacterium tuberculosis- induced neutrophil extracellular traps activate human macrophages. J. Innate Immun. 2013, 5, 591–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, C.W.; Elkington, P.T.; Brilha, S.; Ugarte-Gil, C.; Tome-Esteban, M.T.; Tezera, L.B.; Pabisiak, P.J.; Moores, R.C.; Sathyamoorthy, T.; Patel, V.; et al. Neutrophil-derived MMP-8 drives AMPK-dependent matrix destruction in human pulmonary tuberculosis. PLoS Pathog. 2015, 11, e1004917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira-Teixeira, L.; Stimpson, P.J.; Stavropoulos, E.; Hadebe, S.; Chakravarty, P.; Ioannou, M.; Aramburu, I.V.; Herbert, E.; Priestnall, S.L.; Suarez-Bonnet, A.; et al. Type I IFN exacerbates disease in tuberculosis-susceptible mice by inducing neutrophil-mediated lung inflammation and NETosis. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, R.; Peng, Y.P.; Deng, Z.; Deng, Y.T.; Ye, J.Q.; Guo, Y.; Huang, Z.K.; Luo, Q.; Jiang, H.; Li, J.M. Mycobacterium tuberculosis Infection Induces Low-Density Granulocyte Generation by Promoting Neutrophil Extracellular Trap Formation via ROS Pathway. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dallenga, T.; Repnik, U.; Corleis, B.; Eich, J.; Reimer, R.; Griffiths, G.W.; Schaible, U.E.M. tuberculosis-Induced Necrosis of Infected Neutrophils Promotes Bacterial Growth Following Phagocytosis by Macrophages. Cell Host Microbe 2017, 22, 519–530.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corleis, B.; Korbel, D.; Wilson, R.; Bylund, J.; Chee, R.; Schaible, U.E. Escape of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from oxidative killing by neutrophils. Cell. Microbiol. 2012, 14, 1109–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francis, R.J.; Butler, R.E.; Stewart, G.R. Mycobacterium tuberculosis ESAT-6 is a leukocidin causing Ca2+ influx, necrosis and neutrophil extracellular trap formation. Cell Death Dis. 2014, 5, e1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunter, R.L. The Pathogenesis of Tuberculosis-The Koch Phenomenon Reinstated. Pathogens 2020, 9, 813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ong, C.W.M.; Fox, K.; Ettorre, A.; Elkington, P.T.; Friedland, J.S. Hypoxia increases neutrophil-driven matrix destruction after exposure to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 11475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schechter, M.C.; Buac, K.; Adekambi, T.; Cagle, S.; Celli, J.; Ray, S.M.; Mehta, C.C.; Rada, B.; Rengarajan, J. Neutrophil extracellular trap (NET) levels in human plasma are associated with active TB. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0182587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Melo, M.G.M.; Mesquita, E.D.D.; Oliveira, M.M.; Da Silva-Monteiro, C.; Silveira, A.K.A.; Malaquias, T.S.; Dutra, T.C.P.; Galliez, R.M.; Kritski, A.L.; Silva, E.C. Imbalance of NET and Alpha-1-Antitrypsin in Tuberculosis Patients Is Related With Hyper Inflammation and Severe Lung Tissue Damage. Front. Immunol. 2019, 9, 3147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, S.; Seddon, J.A.; Maasdorp, E.; Kleynhans, L.; du Plessis, N.; Loxton, A.G.; Malherbe, S.T.; Zak, D.E.; Thompson, E.; Duffy, F.J.; et al. Neutrophil degranulation, NETosis and platelet degranulation pathway genes are co-induced in whole blood up to six months before tuberculosis diagnosis. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0278295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ríos-López, A.L.; González, G.M.; Hernández-Bello, R.; Sánchez-González, A. Avoiding the trap: Mechanisms developed by pathogens to escape neutrophil extracellular traps. Microbiol. Res. 2021, 243, 126644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arazna, M.; Pruchniak, M.P.; Demkow, U. Neutrophil extracellular traps in bacterial infections: Strategies for escaping from killing. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 2013, 187, 74–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manda, A.; Pruchniak, M.P.; Araźna, M.; Demkow, U.A. Neutrophil extracellular traps in physiology and pathology. Cent. J. Immunol. 2014, 39, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauth, X.; Von Köckritz-Blickwede, M.; McNamara, C.W.; Myskowski, S.; Zinkernagel, A.S.; Beall, B.; Ghosh, P.; Gallo, R.L.; Nizet, V. M1 Protein Allows Group A Streptococcal Survival in Phagocyte Extracellular Traps through Cathelicidin Inhibition. J. Innate Immun. 2009, 1, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brennan, P.J. Structure, function, and biogenesis of the cell wall of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Tuberculosis 2003, 83, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cavalcante-Silva, L.H.A.; Almeida, F.S.; Andrade, A.G.d.; Comberlang, F.C.; Cardoso, L.L.; Vanderley, S.E.R.; Keesen, T.S.L. Mycobacterium tuberculosis in a Trap: The Role of Neutrophil Extracellular Traps in Tuberculosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 11385. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms241411385

Cavalcante-Silva LHA, Almeida FS, Andrade AGd, Comberlang FC, Cardoso LL, Vanderley SER, Keesen TSL. Mycobacterium tuberculosis in a Trap: The Role of Neutrophil Extracellular Traps in Tuberculosis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2023; 24(14):11385. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms241411385

Chicago/Turabian StyleCavalcante-Silva, Luiz Henrique Agra, Fernanda Silva Almeida, Arthur Gomes de Andrade, Fernando Cézar Comberlang, Leonardo Lima Cardoso, Shayenne Eduarda Ramos Vanderley, and Tatjana S. L. Keesen. 2023. "Mycobacterium tuberculosis in a Trap: The Role of Neutrophil Extracellular Traps in Tuberculosis" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 24, no. 14: 11385. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms241411385

APA StyleCavalcante-Silva, L. H. A., Almeida, F. S., Andrade, A. G. d., Comberlang, F. C., Cardoso, L. L., Vanderley, S. E. R., & Keesen, T. S. L. (2023). Mycobacterium tuberculosis in a Trap: The Role of Neutrophil Extracellular Traps in Tuberculosis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 24(14), 11385. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms241411385