Gain of Function (GOF) Mutant p53 in Cancer—Current Therapeutic Approaches

Abstract

1. Introduction

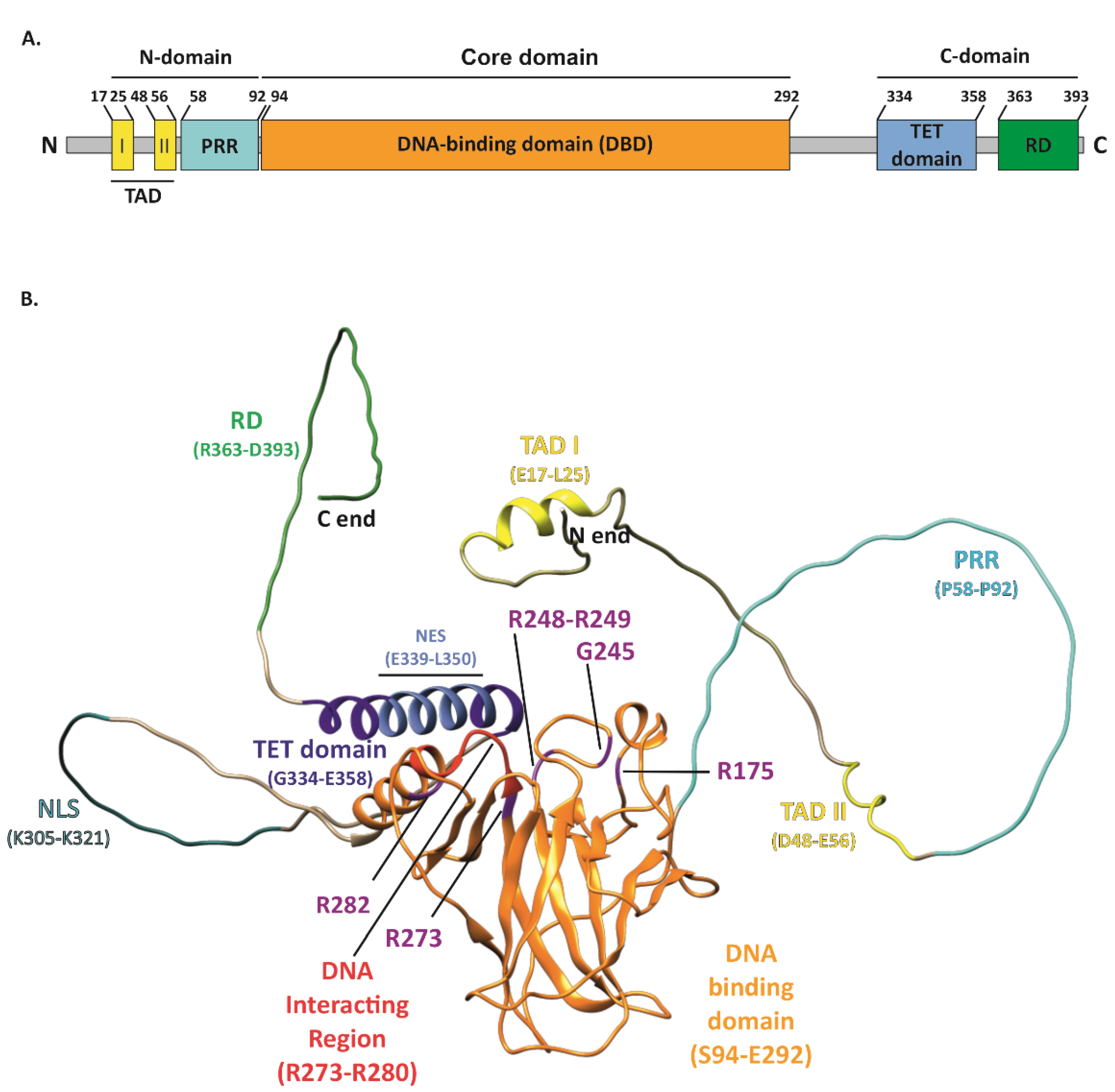

2. Pivotal Functions and Regulation Mechanisms of Wild-Type p53 (WTp53)

3. Features of GOF p53 Mutants

4. Chemoresistance Mechanisms Established by MUTp53

5. Possible Therapeutic Approaches

6. APR-246 (PRIMA-1MET, Eprenetapopt)

7. COTI-2

8. Vorinostat (SAHA)

9. PEITC

10. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lane, D.P. Cancer. p53, guardian of the genome. Nature 1992, 358, 15–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, Y.S.; Mhoumadi, Y.; Verma, C.S. Roles of computational modelling in understanding p53 structure, biology, and its therapeutic targeting. J. Mol. Cell Biol. 2019, 11, 306–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitayner, M.; Rozenberg, H.; Kessler, N.; Rabinovich, D.; Shaulov, L.; Haran, T.E.; Shakked, Z. Structural basis of DNA recognition by p53 tetramers. Mol. Cell 2006, 22, 741–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kruiswijk, F.; Labuschagne, C.F.; Vousden, K.H. p53 in survival, death and metabolic health: A lifeguard with a licence to kill. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2015, 16, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zilfou, J.T.; Lowe, S.W. Tumor suppressive functions of p53. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2009, 1, a001883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bieging, K.T.; Mello, S.S.; Attardi, L.D. Unravelling mechanisms of p53-mediated tumour suppression. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2014, 14, 359–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarado-Ortiz, E.; de la Cruz-Lopez, K.G.; Becerril-Rico, J.; Sarabia-Sanchez, M.A.; Ortiz-Sanchez, E.; Garcia-Carranca, A. Mutant p53 Gain-of-Function: Role in Cancer Development, Progression, and Therapeutic Approaches. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 607670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantovani, F.; Collavin, L.; Del Sal, G. Mutant p53 as a guardian of the cancer cell. Cell Death Differ. 2019, 26, 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, M.S.; Stojanov, P.; Mermel, C.H.; Robinson, J.T.; Garraway, L.A.; Golub, T.R.; Meyerson, M.; Gabriel, S.B.; Lander, E.S.; Getz, G. Discovery and saturation analysis of cancer genes across 21 tumour types. Nature 2014, 505, 495–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouaoun, L.; Sonkin, D.; Ardin, M.; Hollstein, M.; Byrnes, G.; Zavadil, J.; Olivier, M. TP53 Variations in Human Cancers: New Lessons from the IARC TP53 Database and Genomics Data. Hum. Mutat. 2016, 37, 865–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baugh, E.H.; Ke, H.; Levine, A.J.; Bonneau, R.A.; Chan, C.S. Why are there hotspot mutations in the TP53 gene in human cancers? Cell Death Differ. 2018, 25, 154–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jumper, J.; Evans, R.; Pritzel, A.; Green, T.; Figurnov, M.; Ronneberger, O.; Tunyasuvunakool, K.; Bates, R.; Žídek, A.; Potapenko, A.; et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 2021, 596, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varadi, M.; Anyango, S.; Deshpande, M.; Nair, S.; Natassia, C.; Yordanova, G.; Yuan, D.; Stroe, O.; Wood, G.; Laydon, A.; et al. AlphaFold Protein Structure Database: Massively expanding the structural coverage of protein-sequence space with high-accuracy models. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 50, D439–D444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettersen, E.F.; Goddard, T.D.; Huang, C.C.; Couch, G.S.; Greenblatt, D.M.; Meng, E.C.; Ferrin, T.E. UCSF Chimera—A visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 2004, 25, 1605–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastenhuber, E.R.; Lowe, S.W. Putting p53 in Context. Cell 2017, 170, 1062–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simabuco, F.M.; Morale, M.G.; Pavan, I.C.B.; Morelli, A.P.; Silva, F.R.; Tamura, R.E. p53 and metabolism: From mechanism to therapeutics. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 23780–23823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikh, M.S.; Fornace, A.J., Jr. Death and decoy receptors and p53-mediated apoptosis. Leukemia 2000, 14, 1509–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stindt, M.H.; Muller, P.A.; Ludwig, R.L.; Kehrloesser, S.; Dotsch, V.; Vousden, K.H. Functional interplay between MDM2, p63/p73 and mutant p53. Oncogene 2015, 34, 4300–4310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman, M.Y.; Gabai, V.; O’Callaghan, C.; Yaglom, J. Molecular chaperones regulate p53 and suppress senescence programs. FEBS Lett. 2007, 581, 3711–3715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wawrzynow, B.; Zylicz, A.; Zylicz, M. Chaperoning the guardian of the genome. The two-faced role of molecular chaperones in p53 tumor suppressor action. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Rev. Cancer 2018, 1869, 161–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prives, C.; White, E. Does control of mutant p53 by Mdm2 complicate cancer therapy? Genes Dev. 2008, 22, 1259–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, G.A.; Iwakuma, T.; Suh, Y.A.; Liu, G.; Rao, V.A.; Parant, J.M.; Valentin-Vega, Y.A.; Terzian, T.; Caldwell, L.C.; Strong, L.C.; et al. Gain of function of a p53 hot spot mutation in a mouse model of Li-Fraumeni syndrome. Cell 2004, 119, 861–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, X.; Zhao, Y.; Xu, Y.; Zheng, M.; Feng, Z.; Hu, W. Mutant p53 in Cancer: Accumulation, Gain-of-Function, and Therapy. J. Mol. Biol. 2017, 429, 1595–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chipuk, J.E.; Maurer, U.; Green, D.R.; Schuler, M. Pharmacologic activation of p53 elicits Bax-dependent apoptosis in the absence of transcription. Cancer Cell 2003, 4, 371–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, Y.; Rotter, V.; Aloni-Grinstein, R. Gain-of-Function Mutant p53: All the Roads Lead to Tumorigenesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 6197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bykov, V.J.N.; Eriksson, S.E.; Bianchi, J.; Wiman, K.G. Targeting mutant p53 for efficient cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2018, 18, 89–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullock, A.N.; Fersht, A.R. Rescuing the function of mutant p53. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2001, 1, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullock, A.N.; Henckel, J.; Fersht, A.R. Quantitative analysis of residual folding and DNA binding in mutant p53 core domain: Definition of mutant states for rescue in cancer therapy. Oncogene 2000, 19, 1245–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.P.; Lozano, G. Mutant p53 partners in crime. Cell Death Differ. 2018, 25, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.; Deppert, W. Interactions of mutant p53 with DNA: Guilt by association. Oncogene 2007, 26, 2185–2190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Cao, J.; Topatana, W.; Juengpanich, S.; Li, S.; Zhang, B.; Shen, J.; Cai, L.; Cai, X.; Chen, M. Targeting mutant p53 for cancer therapy: Direct and indirect strategies. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2021, 14, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabapathy, K.; Lane, D.P. Therapeutic targeting of p53: All mutants are equal, but some mutants are more equal than others. Nat. Reviews. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 15, 13–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfister, N.T.; Fomin, V.; Regunath, K.; Zhou, J.Y.; Zhou, W.; Silwal-Pandit, L.; Freed-Pastor, W.A.; Laptenko, O.; Neo, S.P.; Bargonetti, J.; et al. Mutant p53 cooperates with the SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex to regulate VEGFR2 in breast cancer cells. Genes Dev. 2015, 29, 1298–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraiuolo, M.; Di Agostino, S.; Blandino, G.; Strano, S. Oncogenic Intra-p53 Family Member Interactions in Human Cancers. Front. Oncol. 2016, 6, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiu, R.; Rolih, V.; Bolli, E.; Barutello, G.; Riccardo, F.; Quaglino, E.; Merighi, I.F.; Pericle, F.; Donofrio, G.; Cavallo, F.; et al. Fighting breast cancer stem cells through the immune-targeting of the xCT cystine-glutamate antiporter. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. CII 2019, 68, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCubrey, J.A.; Meher, A.K.; Akula, S.M.; Abrams, S.L.; Steelman, L.S.; LaHair, M.M.; Franklin, R.A.; Martelli, A.M.; Ratti, S.; Cocco, L.; et al. Wild type and gain of function mutant TP53 can regulate the sensitivity of pancreatic cancer cells to chemotherapeutic drugs, EGFR/Ras/Raf/MEK, and PI3K/mTORC1/GSK-3 pathway inhibitors, nutraceuticals and alter metabolic properties. Aging 2022, 14, 3365–3386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Li, L.; Guan, X.; Xiong, L.; Miao, X. Mutant p53 Gain of Function and Chemoresistance: The Role of Mutant p53 in Response to Clinical Chemotherapy. Chemotherapy 2017, 62, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossi, G.; Lapi, E.; Strano, S.; Rinaldo, C.; Blandino, G.; Sacchi, A. Mutant p53 gain of function: Reduction of tumor malignancy of human cancer cell lines through abrogation of mutant p53 expression. Oncogene 2006, 25, 304–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scian, M.J.; Stagliano, K.E.; Anderson, M.A.; Hassan, S.; Bowman, M.; Miles, M.F.; Deb, S.P.; Deb, S. Tumor-derived p53 mutants induce NF-kappaB2 gene expression. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005, 25, 10097–10110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Lin, F.T.; Graves, J.D.; Lee, Y.J.; Lin, W.C. Mutant p53 perturbs DNA replication checkpoint control through TopBP1 and Treslin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, E3766–E3775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampath, J.; Sun, D.; Kidd, V.J.; Grenet, J.; Gandhi, A.; Shapiro, L.H.; Wang, Q.; Zambetti, G.P.; Schuetz, J.D. Mutant p53 cooperates with ETS and selectively up-regulates human MDR1 not MRP1. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 39359–39367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, R.P.; Tsang, W.P.; Chau, P.Y.; Co, N.N.; Tsang, T.Y.; Kwok, T.T. p53-R273H gains new function in induction of drug resistance through down-regulation of procaspase-3. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2007, 6, 1054–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorini, C.; Cordani, M.; Padroni, C.; Blandino, G.; Di Agostino, S.; Donadelli, M. Mutant p53 stimulates chemoresistance of pancreatic adenocarcinoma cells to gemcitabine. Biochim. Et Biophys. Acta 2015, 1853, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tocci, P.; Cianfrocca, R.; Di Castro, V.; Rosano, L.; Sacconi, A.; Donzelli, S.; Bonfiglio, S.; Bucci, G.; Vizza, E.; Ferrandina, G.; et al. beta-arrestin1/YAP/mutant p53 complexes orchestrate the endothelin A receptor signaling in high-grade serous ovarian cancer. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 3196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Li, Y.; Sheng, J.; Wu, F.; Li, K.; Huang, R.; Wang, X.; Jiao, T.; Guan, X.; Lu, Y.; et al. P53-R273H mutation enhances colorectal cancer stemness through regulating specific lncRNAs. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. CR 2019, 38, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, A.Y.; Gu, L.Y.; Cang, W.; Cheng, M.X.; Wang, W.J.; Di, W.; Huang, L.; Qiu, L.H. Fn14 overcomes cisplatin resistance of high-grade serous ovarian cancer by promoting Mdm2-mediated p53-R248Q ubiquitination and degradation. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. CR 2019, 38, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binayke, A.; Mishra, S.; Suman, P.; Das, S.; Chander, H. Awakening the “guardian of genome”: Reactivation of mutant p53. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2019, 83, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, A.S.; Ramos, H.; Inga, A.; Sousa, E.; Saraiva, L. Structural and Drug Targeting Insights on Mutant p53. Cancers 2021, 13, 3344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrales, A.; Iwakuma, T. Targeting Oncogenic Mutant p53 for Cancer Therapy. Front. Oncol. 2015, 5, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz-Heddergott, R.; Moll, U.M. Gain-of-Function (GOF) Mutant p53 as Actionable Therapeutic Target. Cancers 2018, 10, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Petersen, R.B.; Zheng, L.; Huang, K. Salvation of the fallen angel: Reactivating mutant p53. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2019, 176, 817–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bykov, V.J.; Issaeva, N.; Shilov, A.; Hultcrantz, M.; Pugacheva, E.; Chumakov, P.; Bergman, J.; Wiman, K.G.; Selivanova, G. Restoration of the tumor suppressor function to mutant p53 by a low-molecular-weight compound. Nat. Med. 2002, 8, 282–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salim, K.Y.; Maleki Vareki, S.; Danter, W.R.; Koropatnick, J. COTI-2, a novel small molecule that is active against multiple human cancer cell lines in vitro and in vivo. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 41363–41379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Marchenko, N.D.; Moll, U.M. SAHA shows preferential cytotoxicity in mutant p53 cancer cells by destabilizing mutant p53 through inhibition of the HDAC6-Hsp90 chaperone axis. Cell Death Differ. 2011, 18, 1904–1913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, M.; Saxena, R.; Sinclair, E.; Fu, Y.; Jacobs, A.; Dyba, M.; Wang, X.; Cruz, I.; Berry, D.; Kallakury, B.; et al. Reactivation of mutant p53 by a dietary-related compound phenethyl isothiocyanate inhibits tumor growth. Cell Death Differ. 2016, 23, 1615–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bykov, V.J.; Issaeva, N.; Zache, N.; Shilov, A.; Hultcrantz, M.; Bergman, J.; Selivanova, G.; Wiman, K.G. Reactivation of mutant p53 and induction of apoptosis in human tumor cells by maleimide analogs. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 30384–30391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohell, N.; Alfredsson, J.; Fransson, A.; Uustalu, M.; Bystrom, S.; Gullbo, J.; Hallberg, A.; Bykov, V.J.; Bjorklund, U.; Wiman, K.G. APR-246 overcomes resistance to cisplatin and doxorubicin in ovarian cancer cells. Cell Death Dis. 2015, 6, e1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, J.M.; Gorzov, P.; Veprintsev, D.B.; Soderqvist, M.; Segerback, D.; Bergman, J.; Fersht, A.R.; Hainaut, P.; Wiman, K.G.; Bykov, V.J. PRIMA-1 reactivates mutant p53 by covalent binding to the core domain. Cancer Cell 2009, 15, 376–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degtjarik, O.; Golovenko, D.; Diskin-Posner, Y.; Abrahmsen, L.; Rozenberg, H.; Shakked, Z. Structural basis of reactivation of oncogenic p53 mutants by a small molecule: Methylene quinuclidinone (MQ). Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 7057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menichini, P.; Monti, P.; Speciale, A.; Cutrona, G.; Matis, S.; Fais, F.; Taiana, E.; Neri, A.; Bomben, R.; Gentile, M.; et al. Antitumor Effects of PRIMA-1 and PRIMA-1(Met) (APR246) in Hematological Malignancies: Still a Mutant P53-Dependent Affair? Cells 2021, 10, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, S.I.; Tuszynski, J. The molecular mechanism of action of methylene quinuclidinone and its effects on the structure of p53 mutants. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 37137–37156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milne, J.V.; Zhang, B.Z.; Fujihara, K.M.; Dawar, S.; Phillips, W.A.; Clemons, N.J. Transketolase regulates sensitivity to APR-246 in p53-null cells independently of oxidative stress modulation. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 4480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tessoulin, B.; Descamps, G.; Moreau, P.; Maiga, S.; Lode, L.; Godon, C.; Marionneau-Lambot, S.; Oullier, T.; Le Gouill, S.; Amiot, M.; et al. PRIMA-1Met induces myeloma cell death independent of p53 by impairing the GSH/ROS balance. Blood 2014, 124, 1626–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grellety, T.; Laroche-Clary, A.; Chaire, V.; Lagarde, P.; Chibon, F.; Neuville, A.; Italiano, A. PRIMA-1(MET) induces death in soft-tissue sarcomas cell independent of p53. BMC Cancer 2015, 15, 684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujihara, K.M.; Corrales Benitez, M.; Cabalag, C.S.; Zhang, B.Z.; Ko, H.S.; Liu, D.S.; Simpson, K.J.; Haupt, Y.; Lipton, L.; Haupt, S.; et al. SLC7A11 is a superior determinant of APR-246 (Eprenetapopt) response than TP53 mutation status. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2021, 20, 1858–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceder, S.; Eriksson, S.E.; Liang, Y.Y.; Cheteh, E.H.; Zhang, S.M.; Fujihara, K.M.; Bianchi, J.; Bykov, V.J.N.; Abrahmsen, L.; Clemons, N.J.; et al. Mutant p53-reactivating compound APR-246 synergizes with asparaginase in inducing growth suppression in acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells. Cell Death Dis. 2021, 12, 709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrams, S.L.; Duda, P.; Akula, S.M.; Steelman, L.S.; Follo, M.L.; Cocco, L.; Ratti, S.; Martelli, A.M.; Montalto, G.; Emma, M.R.; et al. Effects of the Mutant TP53 Reactivator APR-246 on Therapeutic Sensitivity of Pancreatic Cancer Cells in the Presence and Absence of WT-TP53. Cells 2022, 11, 794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.; Tamari, R.; DeZern, A.E.; Byrne, M.T.; Gooptu, M.; Chen, Y.B.; Deeg, H.J.; Sallman, D.; Gallacher, P.; Wennborg, A.; et al. Eprenetapopt Plus Azacitidine After Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem-Cell Transplantation for TP53-Mutant Acute Myeloid Leukemia and Myelodysplastic Syndromes. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 2022, JCO2200181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Shapiro, G.I.; Gao, X.; Mahipal, A.; Starr, J.; Furqan, M.; Singh, P.; Ahrorov, A.; Gandhi, L.; Ghosh, A.; et al. Phase Ib study of eprenetapopt (APR-246) in combination with pembrolizumab in patients with advanced or metastatic solid tumors. ESMO Open 2022, 7, 100573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, S.; Bykov, V.J.; Ali, D.; Andren, O.; Cherif, H.; Tidefelt, U.; Uggla, B.; Yachnin, J.; Juliusson, G.; Moshfegh, A.; et al. Targeting p53 in vivo: A first-in-human study with p53-targeting compound APR-246 in refractory hematologic malignancies and prostate cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 2012, 30, 3633–3639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deneberg, S.; Cherif, H.; Lazarevic, V.; Andersson, P.O.; von Euler, M.; Juliusson, G.; Lehmann, S. An open-label phase I dose-finding study of APR-246 in hematological malignancies. Blood Cancer J 2016, 6, e447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cluzeau, T.; Sebert, M.; Rahme, R.; Cuzzubbo, S.; Lehmann-Che, J.; Madelaine, I.; Peterlin, P.; Beve, B.; Attalah, H.; Chermat, F.; et al. Eprenetapopt Plus Azacitidine in TP53-Mutated Myelodysplastic Syndromes and Acute Myeloid Leukemia: A Phase II Study by the Groupe Francophone des Myelodysplasies (GFM). J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 39, 1575–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sallman, D.A.; DeZern, A.E.; Garcia-Manero, G.; Steensma, D.P.; Roboz, G.J.; Sekeres, M.A.; Cluzeau, T.; Sweet, K.L.; McLemore, A.; McGraw, K.L.; et al. Eprenetapopt (APR-246) and Azacitidine in TP53-Mutant Myelodysplastic Syndromes. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 39, 1584–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, X.; Blanden, A.R.; Narayanan, S.; Jayakumar, L.; Lubin, D.; Augeri, D.; Kimball, S.D.; Loh, S.N.; Carpizo, D.R. Small molecule restoration of wildtype structure and function of mutant p53 using a novel zinc-metallochaperone based mechanism. Oncotarget 2014, 5, 8879–8892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, A.L.; Osman, A.A.; Xie, T.X.; Patel, A.; Skinner, H.; Sandulache, V.; Myers, J.N. Reactive oxygen species and p21Waf1/Cip1 are both essential for p53-mediated senescence of head and neck cancer cells. Cell Death Dis. 2015, 6, e1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindemann, A.; Patel, A.A.; Silver, N.L.; Tang, L.; Liu, Z.; Wang, L.; Tanaka, N.; Rao, X.; Takahashi, H.; Maduka, N.K.; et al. COTI-2, A Novel Thiosemicarbazone Derivative, Exhibits Antitumor Activity in HNSCC through p53-dependent and -independent Mechanisms. Clin. Cancer Res. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 2019, 25, 5650–5662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Synnott, N.C.; O’Connell, D.; Crown, J.; Duffy, M.J. COTI-2 reactivates mutant p53 and inhibits growth of triple-negative breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2020, 179, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruefli, A.A.; Ausserlechner, M.J.; Bernhard, D.; Sutton, V.R.; Tainton, K.M.; Kofler, R.; Smyth, M.J.; Johnstone, R.W. The histone deacetylase inhibitor and chemotherapeutic agent suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (SAHA) induces a cell-death pathway characterized by cleavage of Bid and production of reactive oxygen species. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 10833–10838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, C.; Mizzau, M.; Paroni, G.; Maestro, R.; Schneider, C.; Brancolini, C. Role of caspases, Bid, and p53 in the apoptotic response triggered by histone deacetylase inhibitors trichostatin-A (TSA) and suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (SAHA). J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 12579–12589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foggetti, G.; Ottaggio, L.; Russo, D.; Mazzitelli, C.; Monti, P.; Degan, P.; Miele, M.; Fronza, G.; Menichini, P. Autophagy induced by SAHA affects mutant P53 degradation and cancer cell survival. Biosci. Rep. 2019, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natarajan, U.; Venkatesan, T.; Radhakrishnan, V.; Samuel, S.; Rasappan, P.; Rathinavelu, A. Cell Cycle Arrest and Cytotoxic Effects of SAHA and RG7388 Mediated through p21(WAF1/CIP1) and p27(KIP1) in Cancer Cells. Medicina 2019, 55, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Natarajan, U.; Venkatesan, T.; Rathinavelu, A. Effect of the HDAC Inhibitor on Histone Acetylation and Methyltransferases in A2780 Ovarian Cancer Cells. Medicina 2021, 57, 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drozdkova, D.H.; Gursky, J.; Minarik, J.; Uberall, I.; Kolar, Z.; Trtkova, K.S. CDKN1A Gene Expression in Two Multiple Myeloma Cell Lines With Different P53 Functionality. Anticancer Res. 2020, 40, 4979–4987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, H.; Fu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Peng, F.; Lu, M.; Feng, Y.; Chen, L.; Chen, Z.; Li, M.; Chen, Y. Dissection of Anti-tumor Activity of Histone Deacetylase Inhibitor SAHA in Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma Cells via Quantitative Phosphoproteomics. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 577784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernandez-Borja, F.; Mercado-Sanchez, I.; Alcaraz, Y.; Garcia-Revilla, M.A.; Villegas Gomez, C.; Ordaz-Rosado, D.; Santos-Martinez, N.; Garcia-Becerra, R.; Vazquez, M.A. Exploring novel capping framework: High substituent pyridine-hydroxamic acid derivatives as potential antiproliferative agents. Daru J. Fac. Pharm. Tehran Univ. Med. Sci. 2021, 29, 291–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richon, V.M. Cancer biology: Mechanism of antitumour action of vorinostat (suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid), a novel histone deacetylase inhibitor. Br. J. Cancer 2006, 95, S2–S6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, C.P.; Wu, Q.V.; Voutsinas, J.; Fromm, J.R.; Jiang, X.; Pillarisetty, V.G.; Lee, S.M.; Santana-Davila, R.; Goulart, B.; Baik, C.S.; et al. A Phase II Trial of Pembrolizumab and Vorinostat in Recurrent Metastatic Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinomas and Salivary Gland Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 2020, 26, 837–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, R.M.; Fackler, M.J.; Zhang, Z.; Zhou, X.C.; Goetz, M.P.; Boughey, J.C.; Walsh, B.; Carpenter, J.T.; Storniolo, A.M.; Watkins, S.P.; et al. Tumor and serum DNA methylation in women receiving preoperative chemotherapy with or without vorinostat in TBCRC008. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2018, 167, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckert, C.; Parker, C.; Moorman, A.V.; Irving, J.A.; Kirschner-Schwabe, R.; Groeneveld-Krentz, S.; Revesz, T.; Hoogerbrugge, P.; Hancock, J.; Sutton, R.; et al. Risk factors and outcomes in children with high-risk B-cell precursor and T-cell relapsed acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: Combined analysis of ALLR3 and ALL-REZ BFM 2002 clinical trials. Eur. J. Cancer 2021, 151, 175–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, C.; Waters, R.; Leighton, C.; Hancock, J.; Sutton, R.; Moorman, A.V.; Ancliff, P.; Morgan, M.; Masurekar, A.; Goulden, N.; et al. Effect of mitoxantrone on outcome of children with first relapse of acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL R3): An open-label randomised trial. Lancet 2010, 376, 2009–2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, N.B.; Quirt, I.; Hotte, S.; McWhirter, E.; Polintan, R.; Litwin, S.; Adams, P.D.; McBryan, T.; Wang, L.; Martin, L.P.; et al. Phase II trial of vorinostat in advanced melanoma. Investig. New Drugs 2014, 32, 526–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon, S.W.; McGuire, W.P., 3rd; Shafer, D.A.; Sterling, R.K.; Lee, H.M.; Matherly, S.C.; Roberts, J.D.; Bose, P.; Tombes, M.B.; Shrader, E.E.; et al. Phase I Study of Sorafenib and Vorinostat in Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Am. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 42, 649–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghiaseddin, A.; Reardon, D.; Massey, W.; Mannerino, A.; Lipp, E.S.; Herndon, J.E., 2nd; McSherry, F.; Desjardins, A.; Randazzo, D.; Friedman, H.S.; et al. Phase II Study of Bevacizumab and Vorinostat for Patients with Recurrent World Health Organization Grade 4 Malignant Glioma. Oncologist 2018, 23, e157–e178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeh, Y.T.; Yeh, H.; Su, S.H.; Lin, J.S.; Lee, K.J.; Shyu, H.W.; Chen, Z.F.; Huang, S.Y.; Su, S.J. Phenethyl isothiocyanate induces DNA damage-associated G2/M arrest and subsequent apoptosis in oral cancer cells with varying p53 mutations. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2014, 74, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Di Pasqua, A.J.; Govind, S.; McCracken, E.; Hong, C.; Mi, L.; Mao, Y.; Wu, J.Y.; Tomita, Y.; Woodrick, J.C.; et al. Selective depletion of mutant p53 by cancer chemopreventive isothiocyanates and their structure-activity relationships. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 54, 809–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.H.; Uddin, M.H.; Jo, U.; Kim, B.; Song, J.; Suh, D.H.; Kim, H.S.; Song, Y.S. ROS Accumulation by PEITC Selectively Kills Ovarian Cancer Cells via UPR-Mediated Apoptosis. Front. Oncol. 2015, 5, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Zhu, Y.; Yan, S.; Xiao, H.; Yi, J.; Li, R.; Wu, J.; Wen, L. Phenethyl isothiocyanate induces IPEC-J2 cells cytotoxicity and apoptosis via S-G2/M phase arrest and mitochondria-mediated Bax/Bcl-2 pathway. Comp. Biochem. Physiology. Toxicol. Pharmacol. CBP 2019, 226, 108574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aggarwal, M.; Saxena, R.; Asif, N.; Sinclair, E.; Tan, J.; Cruz, I.; Berry, D.; Kallakury, B.; Pham, Q.; Wang, T.T.Y.; et al. p53 mutant-type in human prostate cancer cells determines the sensitivity to phenethyl isothiocyanate induced growth inhibition. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. CR 2019, 38, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Chen, G.; Pelicano, H.; Liao, J.; Huang, J.; Feng, L.; Keating, M.J.; Huang, P. Targeting p53-deficient chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells in vitro and in vivo by ROS-mediated mechanism. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 71378–71389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.M.; Stepanov, I.; Murphy, S.E.; Wang, R.; Allen, S.; Jensen, J.; Strayer, L.; Adams-Haduch, J.; Upadhyaya, P.; Le, C.; et al. Clinical Trial of 2-Phenethyl Isothiocyanate as an Inhibitor of Metabolic Activation of a Tobacco-Specific Lung Carcinogen in Cigarette Smokers. Cancer Prev. Res. 2016, 9, 396–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vikhanskaya, F.; Lee, M.K.; Mazzoletti, M.; Broggini, M.; Sabapathy, K. Cancer-derived p53 mutants suppress p53-target gene expression--potential mechanism for gain of function of mutant p53. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35, 2093–2104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, B.S.; Tiong, K.H.; Choo, H.L.; Chung, F.F.; Hii, L.W.; Tan, S.H.; Yap, I.K.; Pani, S.; Khor, N.T.; Wong, S.F.; et al. Mutant p53-R273H mediates cancer cell survival and anoikis resistance through AKT-dependent suppression of BCL2-modifying factor (BMF). Cell Death Dis. 2015, 6, e1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klimovich, B.; Meyer, L.; Merle, N.; Neumann, M.; Konig, A.M.; Ananikidis, N.; Keber, C.U.; Elmshauser, S.; Timofeev, O.; Stiewe, T. Partial p53 reactivation is sufficient to induce cancer regression. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. CR 2022, 41, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keshavarz-Rahaghi, F.; Pleasance, E.; Kolisnik, T.; Jones, S.J.M. A p53 transcriptional signature in primary and metastatic cancers derived using machine learning. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 987238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, M.C.; Lowe, S.W. Mutant p53: It’s not all one and the same. Cell Death Differ. 2022, 29, 983–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duffy, M.J.; Synnott, N.C.; O’Grady, S.; Crown, J. Targeting p53 for the treatment of cancer. Semin Cancer Biol. 2022, 79, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Strasser, A.; Kelly, G.L. Should mutant TP53 be targeted for cancer therapy? Cell Death Differ. 2022, 29, 911–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolma, L.; Muller, P.A.J. GOF Mutant p53 in Cancers: A Therapeutic Challenge. Cancers 2022, 14, 5091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, M.J.; Tang, M.; Rajaram, S.; O’Grady, S.; Crown, J. Targeting Mutant p53 for Cancer Treatment: Moving Closer to Clinical Use? Cancers 2022, 14, 4499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Drug | Type of Drug | No. of Registered Clinical Trials Related to Cancer Treatment | Mechanism | Targeted p53 Mutants | Phases of Clinical Trials | Discovery |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| APR-246 (Eprenetapopt) | Small molecule-cysteine thiol group targeting compound | 13 | Restoration of the native conformation by binding to thiol groups in the core domain | R175H, R273H | I–III | 2002 [52] |

| COTI-2 | Zn2+ chelator | 1 | Inhibition of MUTp53 misfolding | R175H, R273H, R273C, R282W | I | 2016 [53] |

| SAHA (Vorinostat) | HDAC inhibitor | 283 | Inhibition of the Hsp90 complex- induction of degradation of the mutant p53 | R249S, R273H | I–III | 2011 [54] |

| PEITC | Phytochemical | 7 | Restoration of the native conformation Oxidative stress | R175H | I–III | 2016 [55] |

| ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier | Status | Conditions | Last Update | Available Results | Phase |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT04214860 | Completed | Myeloid Malignancy | 19 January 2022 | No | I |

| NCT03931291 | Completed | Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML), Myelodysplastic Syndromes (MDS) | 19 January 2022 | Yes [68] | II |

| NCT04383938 | Completed | Bladder Cancer, Gastric Cancer, Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC), Urothelial Carcinoma, Advanced Solid Tumor | 3 June 2022 | Yes [69] | I–II |

| NCT03588078 | Unknown | MDS with gene mutations, AML with gene mutations, Myeloproliferative Neoplasm (MPNs), Chronic Myelomonocytic Leukemia (CMML) | 30 January 2020 | Yes [72] | I–II |

| NCT04419389 | Suspended | Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma (NHL), Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL), Mantle Cell Lymphoma (MCL) | 3 June 2022 | No | I–II |

| NCT03745716 | Completed | MDS with MUTp53 | 12 July 2022 | Yes [https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03745716 accessed on 2 October 2022] | III |

| NCT03268382 | Completed | High-grade Serous Ovarian Cancer (HGSC) with MUTp53 | 21 July 2022 | No | II |

| NCT03072043 | Completed | MDS, AML, MPNs; CMML with MUTp53 | 24 January 2022 | Yes [73] | I–II |

| NCT00900614 | Completed | Hematologic Neoplasms, Prostatic Neoplasms | 31 July 2019 | No | I |

| NCT02098343 | Completed | HGSC with MUTp53 | 13 October 2022 | Yes [71] | I–II |

| NCT03391050 | Terminated | Melanoma | 31 July 2019 | No | I–II |

| NCT04990778 | Withdrawn | MCL | 10 March 2022 | No | II |

| ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier | Status | Conditions | Last Update | Available Results | Phase |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT02433626 | Unknown | Ovarian Cancer, Fallopian Tube Cancer, Endometrial Cancer, Cervical Cancer, Peritoneal Cancer, Head and Neck Cancer (HNSCC), Colorectal Cancer, Lung Cancer, Pancreatic Cancer | 1 February 2019 | No | I |

| ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier | Status | Conditions | Last Update | Available Results | Phase |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT00735826 | Completed | Aerodigestive Tract Cancer, Lung Cancer, Esophageal Cancer, Head and Neck Cancer (HNSCC) | 12 October 2018 | No | NA |

| NCT02538510 | Completed | HNSCC, Squamous Cell Carcinoma, Nasopharynx Carcinoma, Salivary Gland Carcinoma | 13 September 2022 | Yes [87] | I–II |

| NCT00616967 | Active, Not Recruiting | Breast Cancer | 3 February 2022 | Yes [88] | II |

| NCT01153672 | Completed | Breast Cancer | 6 September 2019 | Yes [https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01153672 accessed on 2 October 2022] | NA |

| NCT00967057 | Completed | Leukemia | 12 August 2013 | Yes [89,90] | III |

| NCT00121225 | Completed | Melanoma | 29 January 2019 | Yes [91] | II |

| NCT00948688 | Terminated | Pancreatic Cancer | 10 May 2017 | No | I–II |

| NCT01075113 | Completed | Liver Cancer | 20 August 2019 | Yes [92] | I |

| NCT02042989 | Completed | Advanced Cancers with MUTp53 | 11 July 2022 | No | I |

| NCT01738646 | Completed | Glioblastoma | 6 March 2017 | Yes [93] | II |

| ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier | Status | Conditions | Last Update | Available Results | Phase |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT03700983 | Completed | Head and Neck Cancer | 9 October 2018 | No | NA |

| NCT03034603 | Active, Not Recruiting | Head and Neck Neoplasms | 10 October 2022 | No | NA |

| NCT00691132 | Completed | Lung Cancer | 12 May 2017 | Yes [100] | II |

| NCT00968461 | Withdrawn | Leukemia | 15 April 2013 | No | I |

| NCT01790204 | Completed | Oral Cancer with MUTp53 | 23 March 2015 | No | I–II |

| NCT00005883 | Completed | Lung Cancer | 28 March 2011 | No | I |

| NCT02468882 | Unknown | Long-term Effects Secondary to Cancer | 11 June 2015 | No | III |

| NCT03978117 | Recruiting | Healthy | 5 April 2022 | No | II |

| NCT05354453 | Recruiting | Healthy | 19 October 2022 | No | I |

| NCT05070585 | Recruiting | Metabolic Disturbance | 9 June 2022 | No | I–II |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Roszkowska, K.A.; Piecuch, A.; Sady, M.; Gajewski, Z.; Flis, S. Gain of Function (GOF) Mutant p53 in Cancer—Current Therapeutic Approaches. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 13287. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms232113287

Roszkowska KA, Piecuch A, Sady M, Gajewski Z, Flis S. Gain of Function (GOF) Mutant p53 in Cancer—Current Therapeutic Approaches. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2022; 23(21):13287. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms232113287

Chicago/Turabian StyleRoszkowska, Katarzyna A., Aleksandra Piecuch, Maria Sady, Zdzisław Gajewski, and Sylwia Flis. 2022. "Gain of Function (GOF) Mutant p53 in Cancer—Current Therapeutic Approaches" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 23, no. 21: 13287. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms232113287

APA StyleRoszkowska, K. A., Piecuch, A., Sady, M., Gajewski, Z., & Flis, S. (2022). Gain of Function (GOF) Mutant p53 in Cancer—Current Therapeutic Approaches. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 23(21), 13287. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms232113287