Forest Biomass as a Promising Source of Bioactive Essential Oil and Phenolic Compounds for Alzheimer’s Disease Therapy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Chemical Composition of Essential Oil and Phenolic Compounds from E. globulus Leaves

3. Role of Essential Oil and Phenolic Compounds from E. globulus Leaves in Alzheimer’s Disease

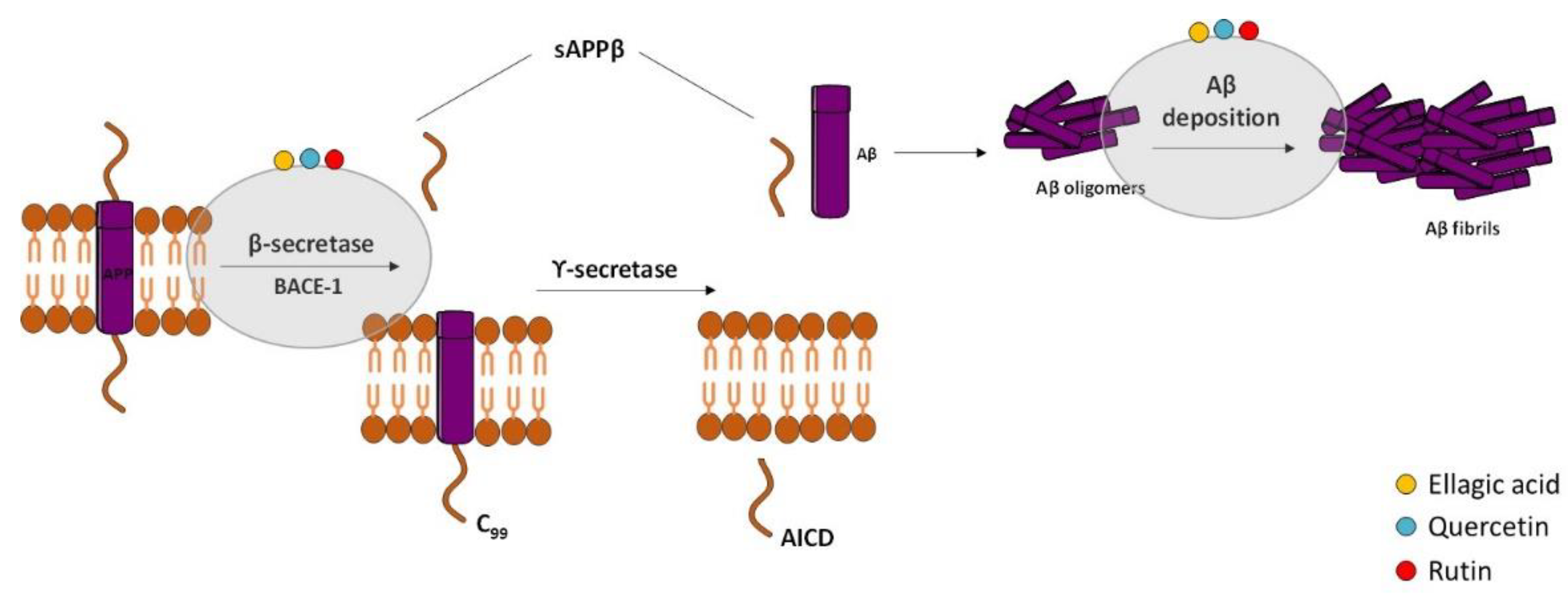

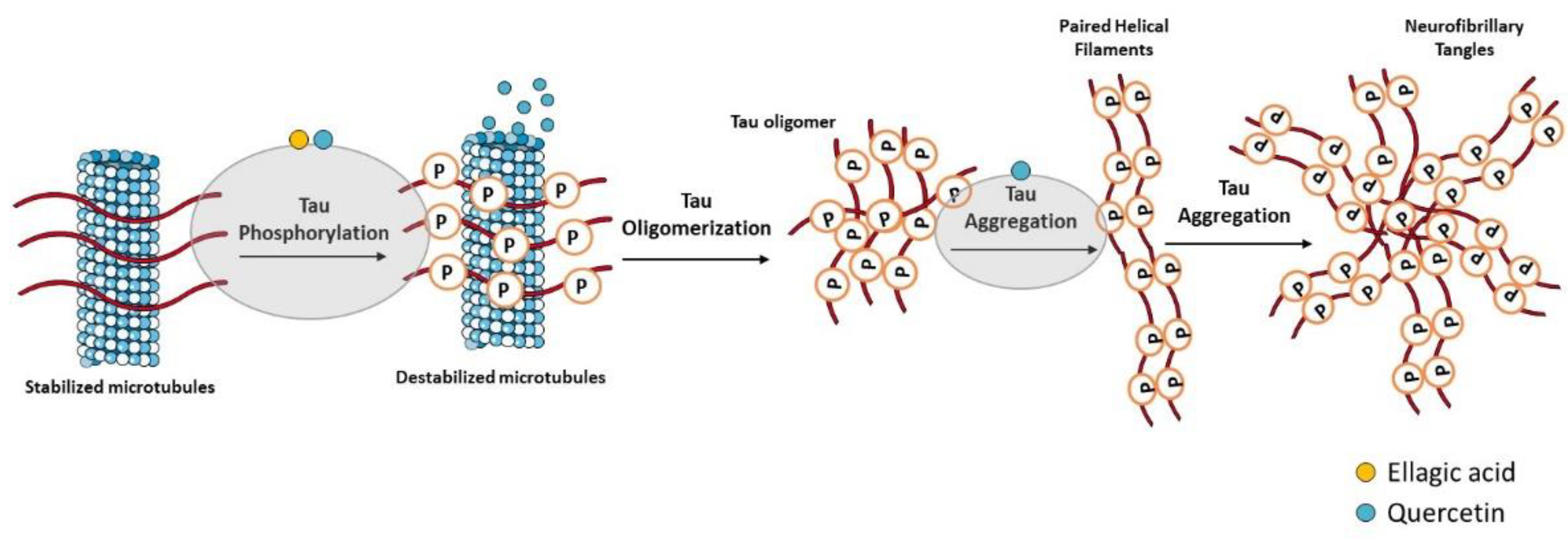

3.1. Aβ Formation and Tau Hyperphosphorylation

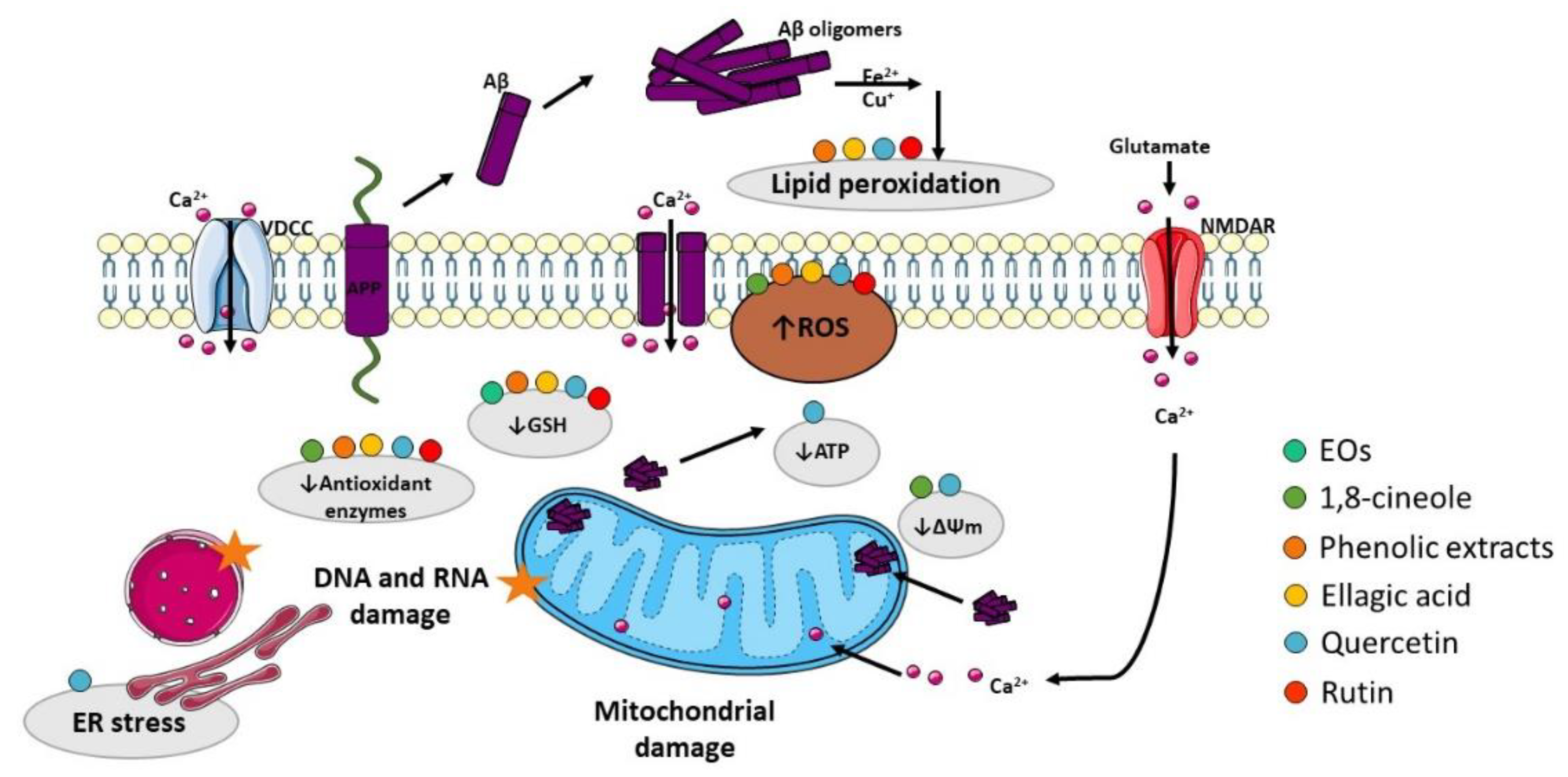

3.2. Oxidative Stress

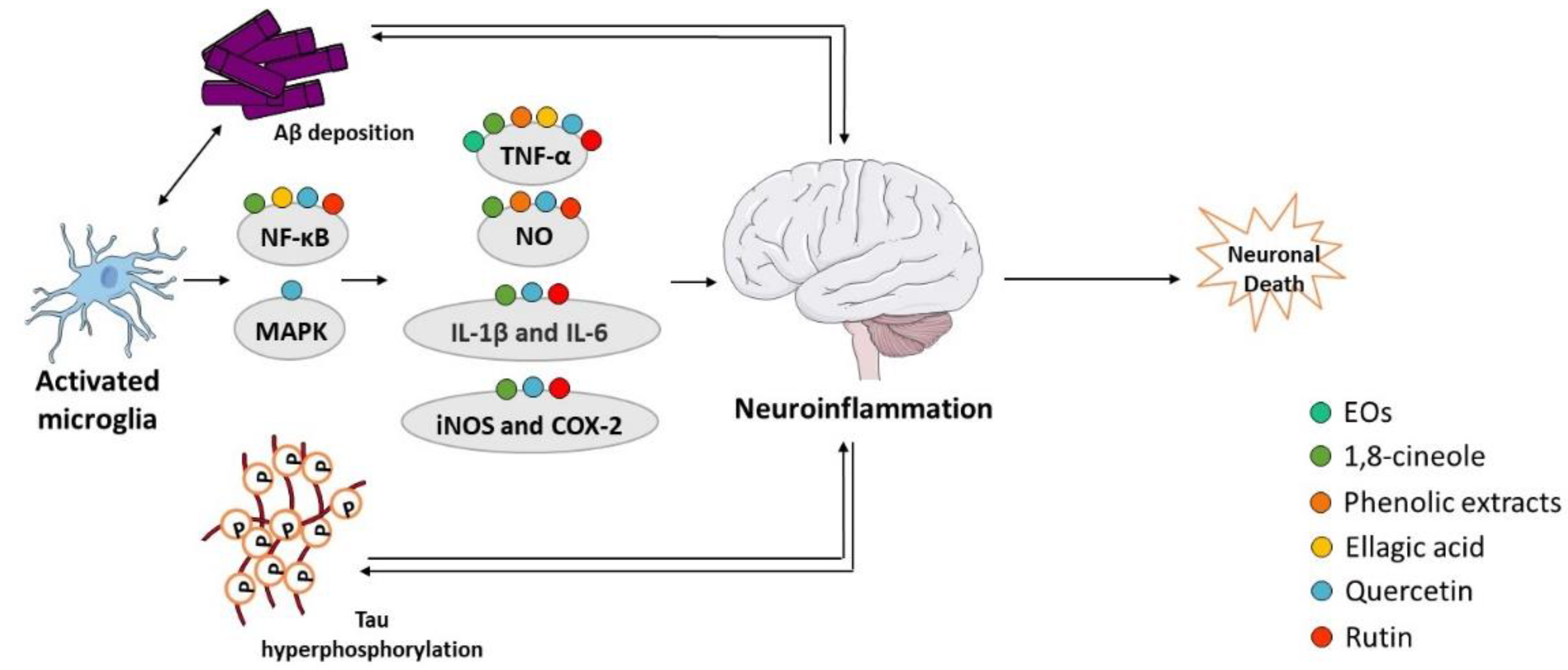

3.3. Inflammation

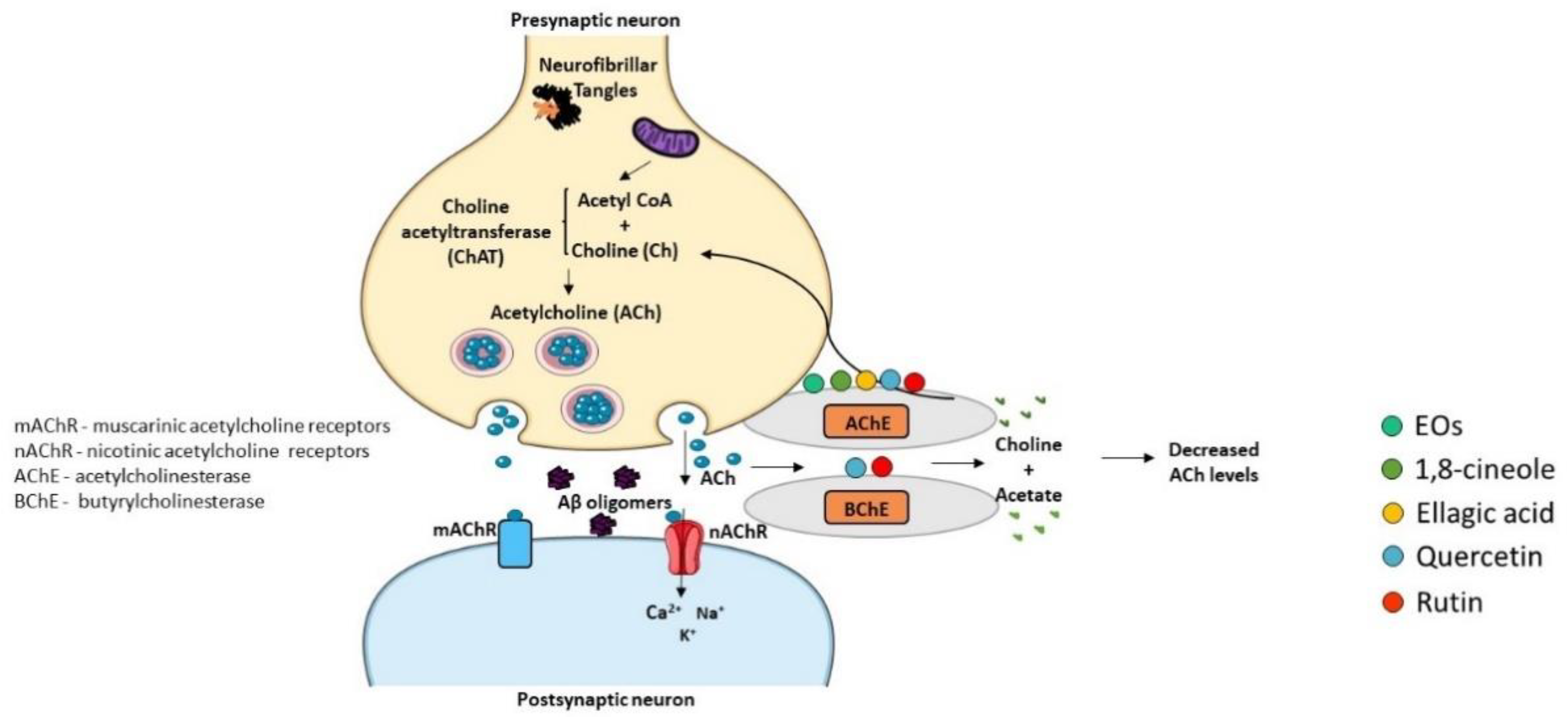

3.4. Cholinesterase Activity

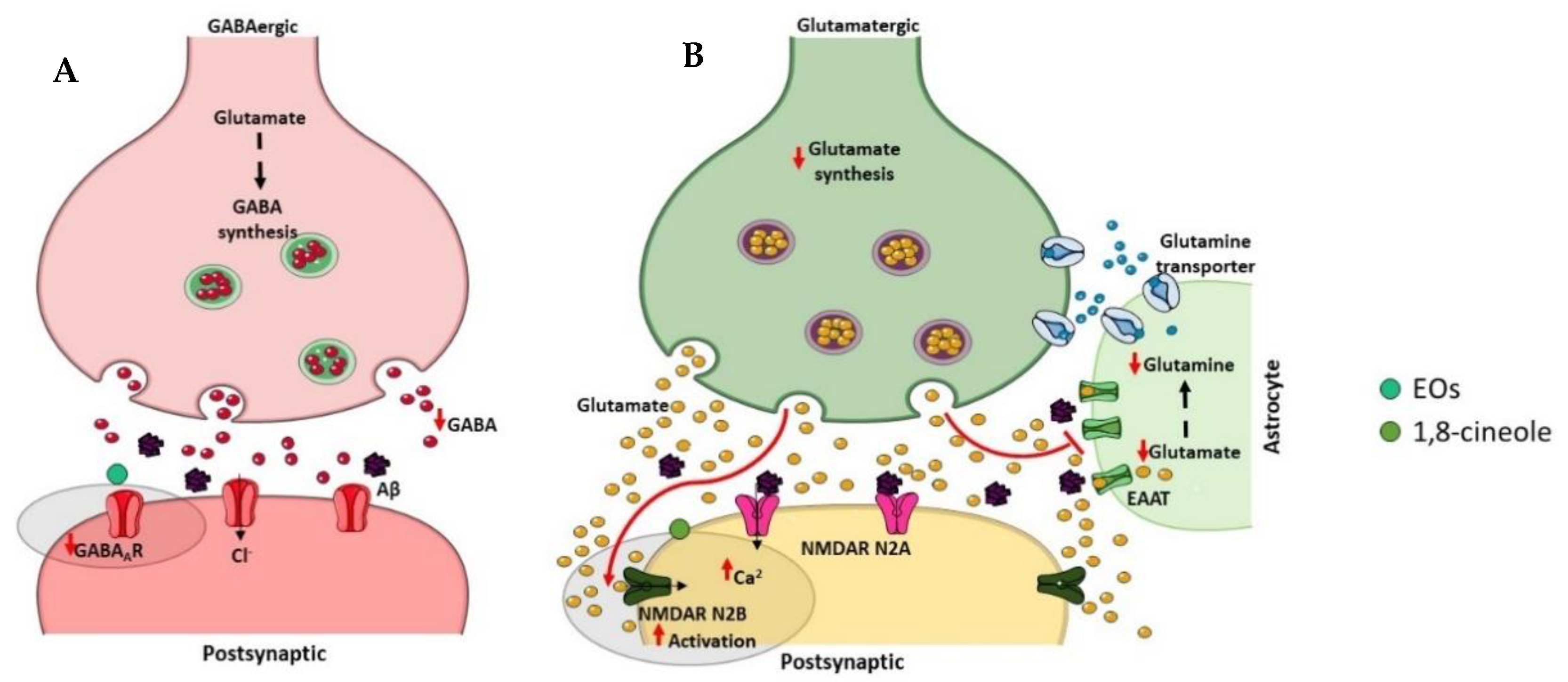

3.5. GABAergic and Glutamatergic Dysfunction

3.6. Impaired Learning and Memory

| Compound | Model | Dose and Duration | Effects | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EO | Cell free | IC50 = 0.1298 mg/mL | Inhibited AChE activity | [16] |

| GT1-7 cells treated with H2O2 | 25 ppm, 24 h | Attenuated neuronal death | [182] | |

| Wistar albino rats treated with ketamine | 500 and 1000 mg/kg/day, p.o., 21 days | Facilitated GABA release, increased GSH levels, inhibited dopamine neurotransmission, decreased TNF-α levels, and diminished AChE activity Restored learning and memory function | [77] | |

| Computational | - | Candidate for NMDA antagonism | [261] | |

| Cineol | Cell free | IC50 = 840 μM | Inhibited AChE activity | [239] |

| Differentiated PC12 cells treated with Aβ25-35 | 2.5, 5 and 10 μM, 24 h | Restored cell viability Reduced mitochondria membrane potential and ROS and NO levels Lowered expression of TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, iNOS, COX-2, and NF-κB | [184] | |

| Primary rat cortical neurons/glial | 10 μM, 4 h | Increased SOD activity and reduced ROS production | [183] | |

| α-pinene | Computational | - | Partially modulated GABAA-BZD receptors Directly bound to the BZD binding site of GABAA receptor | [256] |

| Brain slices | 10 µM | |||

| C57BL/6N mice treated with pentobarbital | 100 mg/kg, p.o. | |||

| C57BL/6 mice treated with scopolamine | 10 mg/kg, i.p. | Improved cognitive dysfunction Increased expression of ChAT Increased protein levels of antioxidant enzymes Activated Nrf2 | [185] | |

| Phenolic extracts | SH-SY5Y cells treated with H2O2 | 5, 10, 25 and 50 µg/mL, 24 h | Increased cell viability, GSH levels, and antioxidant enzymes activity Decreased ROS production and lipid peroxidation levels | [13] |

| RAW264.7 cells treated with LPS and INF-γ | 51 and 83 µg/mL, 24 h | Inhibited NO and TNF-α production | [229] | |

| Ellagic acid | Cell free | IC50 = 39 μM | Inhibited BACE-1 activity | [150] |

| SH-SY5Y cells treated with Aβ1-42 | 5 and 10 μM, 48 h | Promoted oligomers loss Prevented neuronal death | [151] | |

| PC12 cells treated with Aβ25-35 | 0.5, 2.5, and 5 µM, 12 h | Attenuated Aβ-induced toxicity Inhibited ROS production and reduced calcium ion influx | ||

| PC12 cells treated with rotenone | 10 µM, 24 h | Attenuated cell death Reduced ROS and RNS production Suppressed apoptosis | [188] | |

| Primary murine cortical microglia treated with Aβ1-42 | 10 µM, 24 h | Decreased TNF-α secretion | [230] | |

| APP/PS1 transgenic mice | 50 mg/kg/day, i.g., 60 days | Ameliorated learning and memory deficits Reduced neuronal apoptosis and amyloid deposition Inhibited tau hyperphosphorylation and decreased GSK-3β activity | [154] | |

| Wistar rats treated with Aβ25-35 | 50 and 100 mg/kg/day, i.p., 7 days | Improved learning and memory deficits Mitigated oxidative stress by increasing CAT and GSH and reducing MDA levels Reduced AChE activity Modulated NF-κB/Nrf2/TLR4 signaling pathway | [189] | |

| Wistar rats treated with STZ | 50 mg/kg/day, p.o., 30 days | Decreased brain Aβ levels Revealed marked dose-dependent free radical scavenging effect and higher BMA levels Reduced AChE activity Prevented cognitive disfunction | [153] | |

| Wistar rats treated with STZ | 35 mg/kg/day, p.o., 4 weeks | Reduced TBARS production and prevented the depletion of GSH and the inhibition of SOD and CAT activities Increased TNF-α levels Reduced AChE activity Restored memory deficits | [190] | |

| Wistar rats treated with STZ | 17.5 and 35 mg/kg/day, p.o., 28 days | Reduced TBARS production and prevented the depletion of GSH Increased TNF-α levels Restored memory deficits | [191] | |

| Diabetic rats treated with STZ | 50 mg/kg/day, p.o., 21 days | Decreased lipid peroxidation and oxidative stress index Increased antioxidant enzymes Attenuated NO production | [192] | |

| Wistar rats treated with scopolamine and diazepam | 30 and 100 mg/kg/day, i.p., 10 days | Prevented cognitive deficits | [265] | |

| Quercetin | Computational | - | Candidate as AChE inhibitor | [247,249] |

| Cell free | 50 µM | Inhibited and destabilized Aβ fibril formation | [158] | |

| Cell free | 1 mg/mL (76.2% and 46.8% inhibition) | Inhibited AChE and BChE activities | [242] | |

| Cell free | IC50 = 181 µM and IC50 = 203 µM | Inhibited AChE and BChE activities | [240] | |

| Cell free | IC50 = 354 µM and IC50 = 421 µM | Inhibited AChE and BChE activities | [243] | |

| Cell free | IC50 = 19.8 µM | Inhibited AChE activity | [244] | |

| Cell free | IC50 = 3.6 µM | Inhibited AChE activity | [245] | |

| Cell free | IC50 = 14.4 µM | Inhibited AChE activity | [246] | |

| Cell free | IC50 = 51 µM | Inhibited AchE activity | [248] | |

| Cell free Bacterial cells | IC50 = 124.6 μM | Decreased Aβ aggregation | [163] | |

| Cell free | - | Inhibited Aβ fibril formation | [157] | |

| HT22 cells treated with Aβ25-35 | - | Attenuated neuronal death | ||

| HT22 cells treated with OA | 5 and 10 µM, 12 h | Attenuated neuronal death Decreased levels of SOD, mitochondria membrane potential, GPx, MDA, and ROS Inhibited hyperphosphorylation of tau protein Inhibited apoptosis via the reduction of Bax and up-regulation of cleaved caspase 3 via the inhibition of PI3K/Akt/GSK-3β, MAPKs, and activation of NF-κB | [164] | |

| HT22 cells treated with OA | 5 and 10 µM, 12 h | Attenuated tau protein hyperphosphorylation Inhibited the activity of CD-K5 Attenuated intracellular calcium rise | [165] | |

| Differentiated SH-SY5Y cells treated with OA | 100 nM, 6 h | Decreased tau phosphorylation levels | [166] | |

| SH-SY5Y cells treated with OA | 10 µM, 6 h | Suppressed ER stress with decreased phosphorylation of IRE1α and PERK Decreased ROS production and restored mitochondria membrane potential Inhibited TXNIP and NLRP3 inflammasome activation and downregulated ASC and pro-caspase-1 | [167] | |

| C57BL/6J mice exposed to high-fat diets | 50 mg/kg/day, p.o., 10 weeks | Reduced IL-1β and IL-6 production Attenuated tau phosphorylation Reduced IL-1β and TNF-α production Enhanced AMPK activity Inhibited IRE1α and PERK phosphorylation, NLRP3 expression, and tau phosphorylation Improved cognitive disorder | ||

| Cell free | 1, 5 and 10 µM | Inhibited the formation of Aβ fibrils and disaggregated Aβ fibrils | [155] | |

| APPswe-transfected SH-SY5Y cells | 25, 50, and 100 nM, 24 h | Decreased ROS production and lipid peroxidation Increased GSH content and the redox status | ||

| Cell free | IC50 = 55 μM and IC50 = 19 µM IC50 = 0.55 µM | Inhibited AChE and BChE activities Inhibited BACE activity | [160] | |

| SH-SY5Y cells treated with L-DOPA | 10, 50, 250, and 1000 µM, 24 h | Attenuated neuronal death | ||

| 7W CHO cells overexpressing APP | 10, 25, and 50 µM, 24 h | Inhibited Aβ and sAPPβ production Regulated BACE expression | [162] | |

| SH-SY5Y cells treated with TNF-α | 20 µM, 30 min | |||

| SH-SY5Y, U373, and THP-1 cells treated with LPS and INF-γ or INF-γ | 33 µM, 8 h | Reduced oxidative/nitrative damage to DNA, lipids, and proteins Increased intracellular GSH content Reduced the release of TNF-α and IL-6 Attenuated the activation of MAPK and NF-kB | [198] | |

| PC12 cells treated with H2O2 | 10, 30, 60 and 100 µM, 2 h | Preserved cell viability | [195] | |

| Cell free | IC50 = 5.4 μM | Inhibited BACE activity | [161] | |

| Primary rat E18 cortical neurons | 20 μM, 24 h | Decreased Aβ levels | ||

| Primary rat hippocampal neurons treated with Aβ1-42 | 5 and 10 μM, 24 h | Attenuated neuronal death, protein oxidation, lipid peroxidation, and apoptosis | [196] | |

| Primary rat hippocampal neurons treated with Aβ1-42 and H2O2 | 10 μM, 24 h | Attenuated neuronal death, ROS accumulation, and depolarization of mitochondrial membrane | [197] | |

| Primary mouse cortical neurons treated with Aβ25-35 | 30 μM, 24 and 48 h | Demonstrated free radical scavenging activity Ameliorated neuronal death | [193] | |

| Cell free | 250 µM | Inhibited Aβ fibrilization | [168] | |

| C. elegans treated with Aβ1-42 | 73 µM, ~12 days | Increased % of survival | ||

| C. elegans treated with Aβ1-42 | 100 µM, 48 h | Increased proteasomal activity Enhanced the flow of proteins through the macroautophagy pathway | [169] | |

| Zebrafish treated with scopolamine | 50 mg/kg/single dose, i.p. | Attenuated memory deficits | [266] | |

| APP/PS1 transgenic mice | 20 and 40 mg/kg/day, 16 weeks | Improved cognitive deficits Reduced scattered senile plaques Ameliorated mitochondrial dysfunction by restoration of mitochondrial membrane potential, ROS, and ATP levels Increased AMPK activity | [170] | |

| APP/PS1 transgenic mice | 2 mg/g diet, 12 months | Increased Aβ clearance and reduced astrogliosis Ameliorated cognitive dysfunction | [175] | |

| APP/PS1 transgenic mice | 1% in mouse chow, 10 months | Attenuated neuroinflammation by reducing IL-1β and MCP-1 levels | [233] | |

| APP23 transgenic mice | 0.5% in mouse chow, 52 weeks | Reduced eIF2α phosphorylation and ATF4 expression through GADD34 induction Improved memory deficits | [219] | |

| 3xTg-AD mice | 25 mg/kg/48 h, i.p., 3 months | Decreased extracellular β-amyloidosis, tauopathy, astrogliosis, and microgliosis Reduced PHF and Aβ levels Decreased BACE-1-mediated cleavage of APP Improved performance on learning and spatial memory | [171] | |

| 3xTg-AD mice | 100 mg/kg/48 h, p.o., 12 months | Reduced β-amyloidosis and tauopathy Improved cognitive deficits | [172] | |

| 3xTg-AD mice | 25 mg/kg/48 h, i.p., 3 months | Decreased reactive microglia and Aβ Reduced GFAP, iNOS, COX-2, and IL-1β | [173] | |

| 5xFAD mice | 500 mg/kg/day, oral gavage, 10 days | Increased brain ApoE and reduced Aβ levels | [174] | |

| ICR mice injected with Aβ1-42 | 50 and 100 mg/kg/day, p.o., 1 month | Improved learning and memory loss | [270] | |

| ICR mice injected with Aβ25-35 | 50 mg/kg/day, p.o., 2 weeks | Decreased protein levels of APP, BACE, and p-tau Reduced oxidative stress such as ROS and TBARS levels Decreased the protein levels of ER stress markers GRP78, p-PERK, p-eIF2α, XBP1, and CHOP and the proapoptotic molecules Bax, p-JNK, and cleaved caspases-3 and -9 | [176] | |

| Mice injected with Aβ25-35 | 30 mg/kg/day, p.o., 14 days | Decreased NO formation and lipid peroxidation Improved cognitive function | [206] | |

| Kunming mice injected with Aβ25-35 | 5, 10, 20 and 40 mg/kg/day, oral gavage, 8 days | Regulated ERK/CREB/BDNF pathway Restored ACh levels and inhibited AChE activity Improved the learning and memory capabilities | [209] | |

| ICR mice treated with trimethyltin | 5, 10, and 20 mg/kg/day, 3 weeks | Decreased MDA generation and showed antioxidant capacity Inhibited AChE activity Improved cognitive deficits | [205] | |

| C57BL/6N mice treated with LPS | 30 mg/kg/day, i.p., 2 weeks | Prevented the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway and neuronal degeneration by regulating Bax/Bcl2, decreasing activated cytochrome c and caspase-3 activity, and cleaving PARP-1 Reduced activated gliosis and levels of various inflammatory markers such as TNF-α, COX-2, and iNOS Improved memory performance | [207] | |

| Swiss mice treated with LPS | 25, 50, and 100 mg/kg/day, i.p., 7 days | Reversed memory deficits | [268] | |

| Sprague–Dawley rats injected with Aβ1-42 | 100 mg/kg/day, p.o., 19 days | Reduced Aβ levels Increased SOD, CAT, and GSH and decreased MDA levels Increased Nrf2/HO-1 pathway Improved cognitive deficits | [177] | |

| Wistar rats injected with Aβ1-42 | 40 mg/kg/day, p.o., 1 month | Alleviated learning and memory deficits | [271] | |

| Wistar rats treated with STZ | 5, 25, and 50 mg/kg/day, oral gavage, 40 days | Reduced MDA levels Prevented the increase in AChE activity Prevented memory deficits | [204] | |

| Wistar rats treated with STZ | 40 and 80 mg/kg/day, i.p., 12 days | Enhanced spatial memory | [269] | |

| Human early-stage AD patients | 80 mg/patient/day, p.o., 4 weeks | Enhanced memory recall | [272] | |

| Rutin | Computational | - | Candidate as AChE inhibitor | [241] |

| Cell free | 10 µM | Inhibited BACE activity | [159] | |

| Cell free | IC50 = 0.219 mM and IC50 = 0.288 mM | Inhibited AChE and BChE activities | [240] | |

| Cell free APPswe-transfected SH-SY5Y cells | 1, 5, and 10 µM 100 µM 25, 50, and 100 nM, 24 h | Inhibited the formation of Aβ fibrils and disaggregated Aβ fibrils Inhibited BACE activity Decreased ROS production and lipid peroxidation Increased GSH content and the redox status | [155] | |

| Cell free | 50 and 200 µM | Inhibited Aβ fibrillization and attenuated Aβ-induced cytotoxicity | [156] | |

| SH-SY5Y and BV-2 cells treated with Aβ1-42 | 0.8 and 8 µM, 24 h | Decreased ROS, NO, GSSG, and MDA formation Reduced iNOS activity and attenuated mitochondrial damage Increased GSH/GSSG ratio Enhanced SOD, CAT, and GPx activities Decreased TNF-α and IL-1β generation | ||

| Cell free SH-SY5Y cells treated with L-DOPA | IC50 = 3.8 nM 10, 50, 250, and 1000 µM, 24 h | Inhibited BACE activity Attenuated neuronal death | [160] | |

| SH-SY5Y cells treated with amylin | 0.8, 4, and 8 µM, 24 and 48 h | Attenuated neuronal death Decreased the production of ROS, NO, GSSG, MDA, and pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α and IL-1β Attenuated mitochondrial damage and increased the GSH/GSSG ratio Enhanced the antioxidant enzyme activity of SOD, CAT, and GPx Reduced iNOS activity | [194] | |

| Primary mouse cortical neurons treated with Aβ25-35 | 30 μM, 24 and 48 h | Demonstrated free radical scavenging activity Ameliorated neuronal death | [193] | |

| Primary rat microglia treated with LPS | 50 mM, 24 h | Decreased expression levels of TNF- α, IL-1β, IL-6, and iNOS Reduced the production of IL-6, TNF-α, and NO Increased production of the M2 regulatory cytokine IL-10 and arginase Restored upregulation of COX-2, IL-18, and TGF-β | [231] | |

| Zebrafish treated with scopolamine | 50 mg/kg/single dose, i.p. | Attenuated memory deficits | [266] | |

| APP/PS1 transgenic mice | 100 mg/kg/day, p.o., 6 weeks | Decreased oligomeric Aβ level Increased SOD activity and GSH/GSSG ratio Reduced GSSG and MDA levels Downregulated microgliosis and astrocytosis Decreased IL-1β and IL-6 levels Attenuated memory deficits | [178] | |

| ICR mice injected with Aβ25-35 | 100 mg/kg/day, p.o., 14 days | Decreased NO formation and lipid peroxidation Attenuated cognitive deficits | [200] | |

| Swiss albino mice treated with STZ | 2.5, 5, and 10 mg/kg/day, p.o., 21 days | Restored cerebral blood flow and ATP content Reduced MDA and NO levels and increased GSH content Attenuated elevated AChE activity Prevented memory impairment | [203] | |

| Wistar rats injected with Aβ1-42 | 100 mg/kg/day, i.p., 3 weeks | Increased ERK, CREB, and BDNF expression and decreased MDA level Improved memory deficits | [208] | |

| Wistar rats treated with STZ | 25 mg/kg/day, p.o., 3 weeks | Decreased TBARS, PARP activity, and NO level Increased GSH content and activities of GPx, glutathione reductase, and CAT Reduced the expression of COX-2, GFAP, IL-8, iNOS, and NF-kB Improved cognitive deficits | [199] | |

| Sprague–Dawley rats with chronic cerebral hypoperfusion | 50 mg/kg/day, i.p., 12 weeks | Attenuated oxidative damage, namely increased GPx activity and decreased MDA levels and protein carbonyls Inhibited glial activation; reduced the levels of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6; and prevented neuronal damage Alleviated ACh depletion, ChAT inhibition, and AChE activation Improved cognitive deficits | [201] | |

| Wistar rats injected with doxorubicin | 50 mg/kg/day, p.o., 50 days | Reduced CAT, GSH, SOD, and TNF-α levels Prevented memory deficits | [202] | |

| Wistar rats treated with scopolamine | 50 and 100 mg/kg/day, p.o., 15 days | Improved short- and long-term episodic memory deficits | [267] |

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- De Strooper, B.; Karran, E. The Cellular Phase of Alzheimer’s Disease. Cell 2016, 164, 603–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirakhur, A.; Craig, D.; Hart, D.J.; McLlroy, S.P.; Passmore, A.P. Behavioural and psychological syndromes in Alzheimer’s disease. Int J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2004, 19, 1035–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patterson, C. World Alzheimer Report 2018: The State of the Art of Dementia Research: New Frontiers; Alzheimer’s Disease International (ADI): London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Braak, H.; de Vos, R.A.; Jansen, E.N.; Bratzke, H.; Braak, E. Neuropathological hallmarks of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases. Prog. Brain. Res. 1998, 117, 267–285. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sharma, P.; Srivastava, P.; Seth, A.; Tripathi, P.N.; Banerjee, A.G.; Shrivastava, S.K. Comprehensive review of mechanisms of pathogenesis involved in Alzheimer’s disease and potential therapeutic strategies. Prog. Neurobiol. 2019, 174, 53–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russo, P.; Frustaci, A.; Del Bufalo, A.; Fini, M.; Cesario, A. Multitarget drugs of plants origin acting on Alzheimer’s disease. Curr. Med. Chem. 2013, 20, 1686–1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalasz, H.; Ojha, S.; Tekes, K.; Szoke, E.; Mohanraj, R.; Fahim, M.; Adeghate, E.; Adem, A. Pharmacognostical Sources of Popular Medicine to Treat Alzheimer’s Disease. Open Med. Chem. J. 2018, 12, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Park, S.Y. Potential therapeutic agents against Alzheimer’s disease from natural sources. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2010, 33, 1589–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, N.; Khodagholi, F. Natural products as promising drug candidates for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease: Molecular mechanism aspect. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2013, 11, 414–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacabelos, R.; Torrellas, C.; Carrera, I.; Cacabelos, P.; Corzo, L.; Fernandez-Novoa, L.; Tellado, I.; Carril, J.C.; Aliev, G. Novel Therapeutic Strategies for Dementia. CNS Neurol. Disord. Drug Targets 2016, 15, 141–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koynova, R.; Tenchov, B. Natural Product Formulations for the Prevention and Treatment of Alzheimer’s disease: A Patent Review. Recent. Pat. Drug Deliv. 2018, 12, 23–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, L.C.; Filomeno, C.A.; Teixeira, R.R. Chemical Variability and Biological Activities of Eucalyptus spp. Essential Oils. Molecules 2016, 21, 1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Burgos, E.; Liaudanskas, M.; Viskelis, J.; Zvikas, V.; Janulis, V.; Gomez-Serranillos, M.P. Antioxidant activity, neuroprotective properties and bioactive constituents analysis of varying polarity extracts from Eucalyptus globulus leaves. J. Food Drug Anal. 2018, 26, 1293–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhakad, A.K.; Pandey, V.V.; Beg, S.; Rawat, J.M.; Singh, A. Biological, medicinal and toxicological significance of Eucalyptus leaf essential oil: A review. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2018, 98, 833–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreira, P.; Sousa, F.J.; Matos, P.; Brites, G.S.; Goncalves, M.J.; Cavaleiro, C.; Figueirinha, A.; Salgueiro, L.; Batista, M.T.; Branco, P.C.; et al. Chemical Composition and Effect against Skin Alterations of Bioactive Extracts Obtained by the Hydrodistillation of Eucalyptus globulus Leaves. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aazza, S.; Lyoussi, B.; Miguel, M.G. Antioxidant and antiacetylcholinesterase activities of some commercial essential oils and their major compounds. Molecules 2011, 16, 7672–7690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayaz, M.; Sadiq, A.; Junaid, M.; Ullah, F.; Subhan, F.; Ahmed, J. Neuroprotective and Anti-Aging Potentials of Essential Oils from Aromatic and Medicinal Plants. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2017, 9, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakkali, F.; Averbeck, S.; Averbeck, D.; Idaomar, M. Biological effects of essential oils—A review. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2008, 46, 446–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faleiro, M.L.; Miguel, M.G. Use of Essential Oils and Their Components against Multidrug-Resistant Bacteria. In Fighting Multidrug Resistance with Herbal Extracts, Essential Oils and Their Components; Rai, M.K., Kon, K.V., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2013; pp. 65–94. [Google Scholar]

- Zunino, M.P.; Areco, V.A.; Zygadlo, J.A. Insecticidal activity of three essential oils against two new important soybean pests: Sternechus pinguis (Fabricius) and Rhyssomatus subtilis Fiedler (Coleoptera: Curculionidae). Boletín Latinoam. Caribe Plantas Med. Aromáticas 2012, 11, 269–277. [Google Scholar]

- Noumi, E.; Snoussi, M.; Hajlaoui, H.; Trabelsi, N.; Ksouri, R.; Valentin, E.; Bakhrouf, A. Chemical composition, antioxidant and antifungal potential of Melaleuca alternifolia (tea tree) and Eucalyptus globulus essential oils against oral Candida species. J. Med. Plants Res. 2011, 5, 4147–4156. [Google Scholar]

- Tardugno, R.; Pellati, F.; Iseppi, R.; Bondi, M.; Bruzzesi, G.; Benvenuti, S. Phytochemical composition and in vitro screening of the antimicrobial activity of essential oils on oral pathogenic bacteria. Nat. Prod. Res. 2018, 32, 544–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilela, G.R.; de Almeida, G.S.; D’Arce, M.A.B.R.; Moraes, M.H.D.; Brito, J.O.; da Silva, M.F.d.G.; Silva, S.C.; de Stefano Piedade, S.M.; Calori-Domingues, M.A.; da Gloria, E.M. Activity of essential oil and its major compound, 1, 8-cineole, from Eucalyptus globulus Labill., against the storage fungi Aspergillus flavus Link and Aspergillus parasiticus Speare. J. Stored Prod. Res. 2009, 45, 108–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.C.; Choi, H.Y.; Choi, W.S.; Clark, J.M.; Ahn, Y.J. Ovicidal and adulticidal activity of Eucalyptus globulus leaf oil terpenoids against Pediculus humanus capitis (Anoplura: Pediculidae). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004, 52, 2507–2511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chauhan, N.; Malik, A.; Sharma, S. Repellency potential of essential oils against housefly, Musca domestica L. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2018, 25, 4707–4714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manguro, L.O.; Opiyo, S.A.; Asefa, A.; Dagne, E.; Muchori, P.W. Chemical Constituents of Essential Oils from Three Eucalyptus Species Acclimatized in Ethiopia and Kenya. J. Essent. Oil Bear. Plants 2010, 13, 561–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ait-Ouazzou, A.; Loran, S.; Bakkali, M.; Laglaoui, A.; Rota, C.; Herrera, A.; Pagan, R.; Conchello, P. Chemical composition and antimicrobial activity of essential oils of Thymus algeriensis, Eucalyptus globulus and Rosmarinus officinalis from Morocco. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2011, 91, 2643–2651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atmani-Merabet, G.; Belkhiri, A.; Dems, M.A.; Lalaouna, A.; Khalfaoui, Z.; Mosbah, B. Chemical composition, toxicity, and acaricidal activity of Eucalyptus globulus essential oil from Algeria. Curr. Issues Pharm. Med. Sci. 2018, 31, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, M.; Bessa, L.J.; Martins, M.R.; Arantes, S.; Teixeira, A.P.S.; Mendes, A.; Martins da Costa, P.; Belo, A.D.F. Chemical Composition, Antibacterial, Antibiofilm and Synergistic Properties of Essential Oils from Eucalyptus globulus Labill. and Seven Mediterranean Aromatic Plants. Chem. Biodivers. 2017, 14, e1700006–e1700018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djenane, D.; Yangüela, J.; Amrouche, T.; Boubrit, S.; Boussad, N.; Roncalés, P. Chemical composition and antimicrobial effects of essential oils of Eucalyptus globulus, Myrtus communis and Satureja hortensis against Escherichia coli O157: H7 and Staphylococcus aureus in minced beef. Food Sci. Technol. Int. 2011, 17, 505–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Ahmad, A.; Bushra, R. Supercritical carbon dioxide extraction of essential oils from leaves of Eucalyptus globulus L., their analysis and application. Anal. Methods 2016, 8, 1339–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benayache, S.; Benayache, F.; Benyahia, S.; Chalchat, J.-C.; Garry, R.-P. Leaf oils of some Eucalyptus species growing in Algeria. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2001, 13, 210–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harkat-Madouri, L.; Asma, B.; Madani, K.; Said, Z.B.-O.S.; Rigou, P.; Grenier, D.; Allalou, H.; Remini, H.; Adjaoud, A.; Boulekbache-Makhlouf, L. Chemical composition, antibacterial and antioxidant activities of essential oil of Eucalyptus globulus from Algeria. Ind. Crops Prod. 2015, 78, 148–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadjib, B.M.; Amine, F.M.; Abdelkrim, K.; Fairouz, S.; Maamar, M. Liquid and vapour phase antibacterial activity of Eucalyptus globulus essential oil= susceptibility of selected respiratory tract pathogens. Am. J. Infect. Dis. 2014, 10, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daroui-Mokaddem, H.; Kabouche, A.; Bouacha, M.; Soumati, B.; El-Azzouny, A.; Bruneau, C.; Kabouche, Z. GC/MS analysis and antimicrobial activity of the essential oil of fresh leaves of Eucalytus globulus, and leaves and stems of Smyrnium olusatrum from Constantine (Algeria). Nat. Prod. Commun. 2010, 5, 1934578X1000501031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toudert-Taleb, K.; Hedjal-Chebheb, M.; Hami, H.; Debras, J.; Kellouche, A. Composition of essential oils extracted from six aromatic plants of Kabylian origin (Algeria) and evaluation of their bioactivity on Callosobruchus maculatus (Fabricius, 1775) (Coleoptera: Bruchidae). Afr. Entomol. 2014, 22, 417–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viturro, C.I.; Molina, A.C.; Heit, C.I. Volatile components of Eucalyptus globulus Labill ssp. bicostata from Jujuy, Argentina. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2003, 15, 206–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzogaray, R.A.; Lucia, A.; Zerba, E.N.; Masuh, H.M. Insecticidal activity of essential oils from eleven Eucalyptus spp. and two hybrids: Lethal and sublethal effects of their major components on Blattella germanica. J. Econ. Entomol. 2011, 104, 595–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucia, A.; Licastro, S.; Zerba, E.; Masuh, H. Yield, chemical composition, and bioactivity of essential oils from 12 species of Eucalyptus on Aedes aegypti larvae. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 2008, 129, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toloza, A.C.; Lucía, A.; Zerba, E.; Masuh, H.; Picollo, M.I. Eucalyptus essential oil toxicity against permethrin-resistant Pediculus humanus capitis (Phthiraptera: Pediculidae). Parasitol. Res. 2010, 106, 409–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peschiutta, M.L.; Pizzolitto, R.P.; Ordano, M.A.; Zaio, Y.; Zygadlo, J.A. Laboratory evaluation of insecticidal activity of plant essential oils against the vine mealybug, Planococcus ficus. J. Insect Sci. 2017, 56, 79–83. [Google Scholar]

- Yeom, H.-J.; Kang, J.; Kim, S.-W.; Park, I.-K. Fumigant and contact toxicity of Myrtaceae plant essential oils and blends of their constituents against adults of German cockroach (Blattella germanica) and their acetylcholinesterase inhibitory activity. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2013, 107, 200–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-E.; Choi, W.-S.; Lee, H.-S.; Park, B.-S. Cross-resistance of a chlorpyrifos-methyl resistant strain of Oryzaephilus surinamensis (Coleoptera: Cucujidae) to fumigant toxicity of essential oil extracted from Eucalyptus globulus and its major monoterpene, 1, 8-cineole. J. Stored Prod. Res. 2000, 36, 383–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldoghaim, F.S.; Flematti, G.R.; Hammer, K.A. Antimicrobial activity of several cineole-rich Western Australian Eucalyptus essential oils. Microorganisms 2018, 6, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, H.-M.; Kim, J.; Chang, K.-S.; Kim, B.-S.; Yang, Y.-J.; Kim, G.-H.; Shin, S.-C.; Park, I.-K. Larvicidal activity of Myrtaceae essential oils and their components against Aedes aegypti, acute toxicity on Daphnia magna, and aqueous residue. J. Med. Entomol. 2011, 48, 405–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baranska, M.; Schulz, H.; Reitzenstein, S.; Uhlemann, U.; Strehle, M.; Krüger, H.; Quilitzsch, R.; Foley, W.; Popp, J. Vibrational spectroscopic studies to acquire a quality control method of Eucalyptus essential oils. Biopolym. Orig. Res. Biomol. 2005, 78, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayaud, L.; Carricajo, A.; Zhiri, A.; Aubert, G. Comparison of bacteriostatic and bactericidal activity of 13 essential oils against strains with varying sensitivity to antibiotics. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2008, 47, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, A.; Oliveira, J.V.d.; França, S.M.; Navarro, D.M.; Barbosa, D.R.; Dutra, K.d.A. Toxicity and repellency of essential oils in the management of Sitophilus zeamais. Rev. Bras. Eng. Agrícola Ambient. 2019, 23, 372–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciel, M.; Morais, S.; Bevilaqua, C.; Silva, R.; Barros, R.; Sousa, R.; Sousa, L.; Brito, E.; Souza-Neto, M. Chemical composition of Eucalyptus spp. essential oils and their insecticidal effects on Lutzomyia longipalpis. Vet. Parasitol. 2010, 167, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrosio, C.M.; de Alencar, S.M.; Moreno, A.M.; Da Gloria, E.M. Evaluation of the selective antibacterial activity of Eucalyptus globulus and Pimenta pseudocaryophyllus essential oils individually and in combination on Enterococcus faecalis and Lactobacillus rhamnosus. Can. J. Microbiol. 2018, 64, 844–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, J.C.; Endo, E.H.; de Souza, M.R.; Zanqueta, E.B.; Polonio, J.C.; Pamphile, J.A.; Ueda-Nakamura, T.; Nakamura, C.V.; Dias Filho, B.P.; de Abreu Filho, B.A. Bioactivity of essential oils in the control of Alternaria alternata in dragon fruit (Hylocereus undatus Haw.). Ind. Crops Prod. 2017, 97, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mossi, A.J.; Astolfi, V.; Kubiak, G.; Lerin, L.; Zanella, C.; Toniazzo, G.; de Oliveira, D.; Treichel, H.; Devilla, I.A.; Cansian, R. Insecticidal and repellency activity of essential oil of Eucalyptus sp. against Sitophilus zeamais Motschulsky (Coleoptera, Curculionidae). J. Sci. Food Agric. 2011, 91, 273–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Godoi, S.N.; Quatrin, P.M.; Sagrillo, M.R.; Nascimento, K.; Wagner, R.; Klein, B.; Santos, R.C.V.; Ourique, A.F. Evaluation of stability and in vitro security of nanoemulsions containing Eucalyptus globulus oil. BioMed Res. Int. 2017, 2017, 2723418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galli, G.M.; Roza, L.F.; Santos, R.C.; Quatrin, P.M.; Ourique, A.F.; Klein, B.; Wagner, R.; Baldissera, M.D.; Volpato, A.; Campigotto, G. Low Dose of Nanocapsules Containing Eucalyptus Oil Has Beneficial Repellent Effect against Horn Fly (Diptera: Muscidae). J. Econ. Entomol. 2018, 111, 2983–2987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldbeck, J.C.; do Nascimento, J.E.; Jacob, R.G.; Fiorentini, Â.M.; da Silva, W.P. Bioactivity of essential oils from Eucalyptus globulus and Eucalyptus urograndis against planktonic cells and biofilms of Streptococcus mutans. Ind. Crops Prod. 2014, 60, 304–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomazoni, E.Z.; Pauletti, G.F.; da Silva Ribeiro, R.T.; Moura, S.; Schwambach, J. In vitro and in vivo activity of essential oils extracted from Eucalyptus staigeriana, Eucalyptus globulus and Cinnamomum camphora against Alternaria solani Sorauer causing early blight in tomato. Sci. Hortic. 2017, 223, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrotti, C.; Marcon, Â.R.; Delamare, A.P.L.; Echeverrigaray, S.; da Silva Ribeiro, R.T.; Schwambach, J. Alternative control of grape rots by essential oils of two Eucalyptus species. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2019, 99, 6552–6561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomazoni, E.Z.; Griggio, G.S.; Broilo, E.P.; da Silva Ribeiro, R.T.; Soares, G.L.G.; Schwambach, J. Screening for inhibitory activity of essential oils on fungal tomato pathogen Stemphylium solani Weber. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2018, 16, 364–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pansera, M.R.; Conte, R.I.; e Silva, S.M.; Sartori, V.C.; silva Ribeiro, R.T. Strategic control of postharvest decay in peach caused by Monilinia fructicola and Colletotrichum gloeosporioides. Appl. Res. Agrotechnol. 2015, 8, 7–14. [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto, C.; De Sant’anna, J.R.; Franco, C.D.S.; Cunico, M.; Miguel, O.; Côcco, L.; Yamamoto, C.; Corrêa, C.; de Castro-Prado, M. Genotoxic activity of Eucalyptus globulus essential oil in Aspergillus nidulans diploid cells. Folia Microbiol. 2009, 54, 493–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno, P.C.P.; Junior, M.G.; Bastos, J.K. A GC-FID validated method for the quality control of Eucalyptus globulus raw material and its pharmaceutical products, and GC-MS fingerprinting of 12 Eucalyptus species. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2014, 9, 1934578X1400901233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sameza, M.L.; Boat, M.A.B.; Nguemezi, S.T.; Mabou, L.C.N.; Dongmo, P.M.J.; Boyom, F.F.; Menut, C. Potential use of Eucalyptus globulus essential oil against Phytophthora colocasiae the causal agent of taro leaf blight. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2014, 140, 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bittner, M.L.; Casanueva, M.E.; Arbert, C.C.; Aguilera, M.A.; Hernández, V.J.; Becerra, J.V. Effects of essential oils from five plant species against the granary weevils Sitophilus zeamais and Acanthoscelides obtectus (Coleoptera). J. Child Chem. Soc. 2008, 53, 1444–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, A.; Gutiérrez-Cutiño, M.; Moenne, A. Oligo-carrageenan kappa-induced reducing redox status and increase in TRR/TRX activities promote activation and reprogramming of terpenoid metabolism in Eucalyptus trees. Molecules 2014, 19, 7356–7367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, K.; Tang, L.; Zhang, N.; Zhou, Y.; Li, W.; Li, H.; Cheng, D.; Zhang, Z. Repellent and fumigant activities of Eucalyptus globulus and Artemisia carvifolia essential oils against Solenopsis invicta. Bull. Insectol. 2014, 67, 207–211. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Chen, Z.; Han, F.; Kang, X.; Gu, H.; Yang, L. Microwave-assisted method for simultaneous hydrolysis and extraction in obtaining ellagic acid, gallic acid and essential oil from Eucalyptus globulus leaves using Brönsted acidic ionic liquid [HO3S (CH2) 4mim] HSO4. Ind. Crops Prod. 2016, 81, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- España, M.D.; Arboleda, J.W.; Ribeiro, J.A.; Abdelnur, P.V.; Guzman, J.D. Eucalyptus leaf byproduct inhibits the anthracnose-causing fungus Colletotrichum gloeosporioides. Ind. Crops Prod. 2017, 108, 793–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimanga, K.; Kambu, K.; Tona, L.; Apers, S.; De Bruyne, T.; Hermans, N.; Totté, J.; Pieters, L.; Vlietinck, A.J. Correlation between chemical composition and antibacterial activity of essential oils of some aromatic medicinal plants growing in the Democratic Republic of Congo. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2002, 79, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacchetti, G.; Maietti, S.; Muzzoli, M.; Scaglianti, M.; Manfredini, S.; Radice, M.; Bruni, R. Comparative evaluation of 11 essential oils of different origin as functional antioxidants, antiradicals and antimicrobials in foods. Food Chem. 2005, 91, 621–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elzayyat, E.; Elleboudy, N.; Moustafa, A.; Ammar, A. Insecticidal, Oxidative, and Genotoxic Activities of Syzygium aromaticum and Eucalyptus globulus on Culex pipiens Adults and Larvae. Türkiye Parazitolojii Derg. 2018, 42, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yones, D.A.; Bakir, H.Y.; Bayoumi, S.A. Chemical composition and efficacy of some selected plant oils against Pediculus humanus capitis in vitro. Parasitol. Res. 2016, 115, 3209–3218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekonnen, A.; Yitayew, B.; Tesema, A.; Taddese, S. In vitro antimicrobial activity of essential oil of Thymus schimperi, Matricaria chamomilla, Eucalyptus globulus, and Rosmarinus officinalis. Int. J. Microbiol. 2016, 2016, 9545693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagne, E.; Bisrat, D.; Alemayehu, M.; Worku, T. Essential oils of twelve Eucalyptus species from Ethiopia. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2000, 12, 467–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, P.-G.; Berti, L.; Panighi, J.; Luciani, A.; Maury, J.; Muselli, A.; Serra, D.d.R.; Gonny, M.; Bolla, J.-M. Antibacterial action of essential oils from Corsica. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2007, 19, 176–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulyaningsih, S.; Sporer, F.; Reichling, J.; Wink, M. Antibacterial activity of essential oils from Eucalyptus and of selected components against multidrug-resistant bacterial pathogens. Pharm. Biol. 2011, 49, 893–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vivekanandhan, P.; Usha-Raja-Nanthini, A.; Valli, G.; Subramanian Shivakumar, M. Comparative efficacy of Eucalyptus globulus (Labill) hydrodistilled essential oil and temephos as mosquito larvicide. Nat. Prod. Res. 2020, 34, 2626–2629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, M.; Jindal, D.K.; Parle, M.; Kumar, A.; Dhingra, S. Targeting oxidative stress, acetylcholinesterase, proinflammatory cytokine, dopamine and GABA by eucalyptus oil (Eucalyptus globulus) to alleviate ketamine-induced psychosis in rats. Inflammopharmacology 2019, 27, 301–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, A.; Chattopadhyay, P.; Banerjee, S.; Pakshirajan, K.; Singh, L. Antitermitic activity of plant essential oils and their major constituents against termite Odontotermes assamensis Holmgren (Isoptera: Termitidae) of North East India. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2012, 75, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, A.; Sharma, A.; Bachheti, R.; Pandey, D. A Comparative study of the chemical composition of the essential oil from Eucalyptus globulus growing in Dehradun (India) and around the World. Orient. J. Chem. 2016, 32, 331–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pant, M.; Dubey, S.; Patanjali, P.; Naik, S.; Sharma, S. Insecticidal activity of eucalyptus oil nanoemulsion with karanja and jatropha aqueous filtrates. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2014, 91, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Mishra, S.; Malik, A.; Satya, S. Compositional analysis and insecticidal activity of Eucalyptus globulus (family: Myrtaceae) essential oil against housefly (Musca domestica). Acta Trop. 2012, 122, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, A.K.; Malik, A. Antimicrobial potential and chemical composition of Eucalyptus globulus oil in liquid and vapour phase against food spoilage microorganisms. Food Chem. 2011, 126, 228–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Bhagat, M.; Sudan, R.; Dogra, S.; Jamwal, R. Comparative Chemoprofiling and Biological Potential of Three Eucalyptus Species Growing in Jammu and Kashmir. J. Essent. Oil Bear. Plants 2015, 18, 409–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, S.M.; Wilson, G.; Raftos, D.; Mirzargar, S.S.; Omidbaigi, R. Antibacterial activities of a new combination of essential oils against marine bacteria. Aquac. Int. 2011, 19, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azadbakht, E.; Maghsoudlou, Y.; Khomiri, M.; Kashiri, M. Development and structural characterization of chitosan films containing Eucalyptus globulus essential oil: Potential as an antimicrobial carrier for packaging of sliced sausage. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2018, 17, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laquale, S.; Candido, V.; Avato, P.; Argentieri, M.; d’Addabbo, T. Essential oils as soil biofumigants for the control of the root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita on tomato. Ann. Appl. Biol. 2015, 167, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardoni, S.; Giovanelli, S.; Pistelli, L.; Mugnaini, L.; Profili, G.; Pisseri, F.; Mancianti, F. In vitro activity of twenty commercially available, plant-derived essential oils against selected dermatophyte species. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2015, 10, 1473–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardoni, S.; Ebani, V.V.; D’Ascenzi, C.; Pistelli, L.; Mancianti, F. Sensitivity of entomopathogenic fungi and bacteria to plants secondary metabolites, for an alternative control of Rhipicephalus (Boophilus) microplus in cattle. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebani, V.V.; Najar, B.; Bertelloni, F.; Pistelli, L.; Mancianti, F.; Nardoni, S. Chemical Composition and In Vitro Antimicrobial Efficacy of Sixteen Essential Oils against Escherichia coli and Aspergillus fumigatus Isolated from Poultry. Vet. Sci. 2018, 5, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fratini, F.; Casella, S.; Leonardi, M.; Pisseri, F.; Ebani, V.V.; Pistelli, L.; Pistelli, L. Antibacterial activity of essential oils, their blends and mixtures of their main constituents against some strains supporting livestock mastitis. Fitoterapia 2014, 96, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tampieri, M.; Galuppi, R.; Carelle, M.; Macchioni, F.; Cioni, P.; Morelli, I. Effect of selected essential oils and pure compounds on Saprolegnia parasitica. Pharm. Biol. 2003, 41, 584–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tampieri, M.P.; Galuppi, R.; Macchioni, F.; Carelle, M.S.; Falcioni, L.; Cioni, P.L.; Morelli, I. The inhibition of Candida albicans by selected essential oils and their major components. Mycopathologia 2005, 159, 339–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrucci, S. Acaricidal activity of some essential oils and their constituents against Tyrophagus longior, a mite of stored food. J. Food Prot. 1995, 58, 560–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Della Porta, G.; Porcedda, S.; Marongiu, B.; Reverchon, E. Isolation of eucalyptus oil by supercritical fluid extraction. Flavour Frag J. 1999, 14, 214–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karemu, C.K.; Ndung’u, M.W.; Githua, M. Repellent effects of essential oils from selected eucalyptus species and their major constituents against Sitophilus zeamais (Coleoptera: Curculionidae). Int. J. Trop. Insect Sci. 2013, 33, 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damjanović-Vratnica, B.; Đakov, T.; Šuković, D.; Damjanović, J. Antimicrobial effect of essential oil isolated from Eucalyptus globulus Labill. from Montenegro. Czech. J. Food Sci. 2011, 29, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chebli, B.; Hmamouchi, M.; Achouri, M.; Hassani, L.I. Composition and in vitro fungitoxic activity of 19 essential oils against two post-harvest pathogens. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2004, 16, 507–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaddor, M.; Lamarti, A.; Tantaoui-Elaraki, A.; Ezziyyani, M.; Castillo, M.-E.C.; Badoc, A. Antifungal activity of three essential oils on growth and toxigenesis of Penicillium aurantiogriseum and Penicillium viridicatum. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2006, 18, 586–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aazza, S.; Lyoussi, B.; Megias, C.; Cortes-Giraldo, I.; Vioque, J.; Figueiredo, A.C.; Miguel, M.G. Anti-oxidant, anti-inflammatory and anti-proliferative activities of Moroccan commercial essential oils. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2014, 9, 587–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaffar, A.; Yameen, M.; Kiran, S.; Kamal, S.; Jalal, F.; Munir, B.; Saleem, S.; Rafiq, N.; Ahmad, A.; Saba, I. Chemical composition and in-vitro evaluation of the antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of essential oils extracted from seven Eucalyptus species. Molecules 2015, 20, 20487–20498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, Z.; Hussain, I.; Hussain, A.; Ashraf, M.Y. Genetic variability to essential oil contents and composition in five species of Eucalyptus. Pak. J. Bot. 2003, 35, 843–852. [Google Scholar]

- Silvestre, A.J.D.; Cavaleiro, J.A.S.; Delmond, B.; Filliatre, C.; Bourgeois, G. The Essential Oil of Eucalyptus globulus Labill. from Portugal. Flavour Frag J. 1994, 9, 51–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topiar, M.; Sajfrtova, M.; Pavela, R.; Machalova, Z. Comparison of fractionation techniques of CO2 extracts from Eucalyptus globulus-Composition and insecticidal activity. J. Supercrit Fluid 2015, 97, 202–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Císarová, M.; Tančinová, D.; Medo, J.; Kačániová, M. The in vitro effect of selected essential oils on the growth and mycotoxin production of Aspergillus species. J. Environ. Sci. Health Part B 2016, 51, 668–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Combrinck, S.; Regnier, T.; Kamatou, G. In vitro activity of eighteen essential oils and some major components against common postharvest fungal pathogens of fruit. Ind. Crops Prod. 2011, 33, 344–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diánez, F.; Santos, M.; Parra, C.; Navarro, M.; Blanco, R.; Gea, F. Screening of antifungal activity of 12 essential oils against eight pathogenic fungi of vegetables and mushroom. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2018, 67, 400–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luís, Â.; Duarte, A.; Gominho, J.; Domingues, F.; Duarte, A.P. Chemical composition, antioxidant, antibacterial and anti-quorum sensing activities of Eucalyptus globulus and Eucalyptus radiata essential oils. Ind. Crops Prod. 2016, 79, 274–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jesser, E.N.; Werdin-González, J.O.; Murray, A.P.; Ferrero, A.A. Efficacy of essential oils to control the Indian meal moth, Plodia interpunctella (Hübner)(Lepidoptera: Pyralidae). J. Asia-Pac. Entomol. 2017, 20, 1122–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadtong, S.; Kamkaen, N.; Watthanachaiyingcharoen, R.; Ruangrungsi, N. Chemical components of four essential oils in aromatherapy recipe. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2015, 10, 1934578X1501000673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soonwera, M.; Wongnet, O.; Sittichok, S. Ovicidal effect of essential oils from Zingiberaceae plants and Eucalytus globulus on eggs of head lice, Pediculus humanus capitis De Geer. Phytomedicine 2018, 47, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghrab, S.; Balme, S.; Cretin, M.; Bouaziz, S.; Benzina, M. Adsorption of terpenes from Eucalyptus globulus onto modified beidellite. Appl. Clay Sci. 2018, 156, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elaissi, A.; Medini, H.; Khouja, M.L.; Simmonds, M.; Lynen, F.; Farhat, F.; Chemli, R.; Harzallah-Skhiri, F. Variation in volatile leaf oils of five Eucalyptus species harvested from Jbel Abderrahman Arboreta (Tunisia). Chem. Biodivers. 2011, 8, 352–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerbi, A.; Derbali, A.; Elfeki, A.; Kammoun, M. Essential oil composition and biological activities of Eucalyptus globulus leaves extracts from Tunisia. J. Essent. Oil Bear. Plants 2017, 20, 438–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slimane, B.B.; Ezzine, O.; Dhahri, S.; Jamaa, M.L.B. Essential oils from two Eucalyptus from Tunisia and their insecticidal action on Orgyia trigotephras (Lepidotera, Lymantriidae). Biol. Res. 2014, 47, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hafsa, J.; ali Smach, M.; Khedher, M.R.B.; Charfeddine, B.; Limem, K.; Majdoub, H.; Rouatbi, S. Physical, antioxidant and antimicrobial properties of chitosan films containing Eucalyptus globulus essential oil. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 68, 356–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, A.; Shibamoto, T. Antioxidant/lipoxygenase inhibitory activities and chemical compositions of selected essential oils. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 7218–7225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, B.G. Tannins and Polyphenols. In Encyclopedia of Food Sciences and Nutrition, 2nd ed.; Caballero, B., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2003; pp. 5729–5733. [Google Scholar]

- Boulekbache-Makhlouf, L.; Meudec, E.; Mazauric, J.P.; Madani, K.; Cheynier, V. Qualitative and Semi-quantitative Analysis of Phenolics in Eucalyptus globulus Leaves by High-performance Liquid Chromatography Coupled with Diode Array Detection and Electrospray Ionisation Mass Spectrometry. Phytochem. Anal. 2013, 24, 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, S.A.; Freire, C.S.; Domingues, M.R.; Silvestre, A.J.; Pascoal Neto, C. Characterization of phenolic components in polar extracts of Eucalyptus globulus Labill. bark by high-performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 9386–9393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harborne, J.B. Phytochemical Methods: A Guide to Modern Techniques of Plant. Analysis, 3rd ed.; Chapman and Hall: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Dezsi, S.; Badarau, A.S.; Bischin, C.; Vodnar, D.C.; Silaghi-Dumitrescu, R.; Gheldiu, A.M.; Mocan, A.; Vlase, L. Antimicrobial and antioxidant activities and phenolic profile of Eucalyptus globulus Labill. and Corymbia ficifolia (F. Muell.) K.D. Hill & L.A.S. Johnson leaves. Molecules 2015, 20, 4720–4734. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Salgado, P.; Márquez, K.; Rubilar, O.; Contreras, D.; Vidal, G. The effect of phenolic compounds on the green synthesis of iron nanoparticles (Fe x O y-NPs) with photocatalytic activity. Appl. Nanosci. 2019, 9, 371–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.E.; Sun, X.; Kim, M.K.; Li, W.Y.; Lee, S.W.; Koppula, S.; Yu, S.H.; Kim, H.B.; Kang, T.B.; Lee, K.H. Eucalyptus globulus Inhibits Inflammasome-Activated Pro-Inflammatory Responses and Ameliorate Monosodium Urate-Induced Peritonitis in Murine Experimental Model. Am. J. Chin. Med. 2018, 46, 423–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghareeb, M.A.; Sobeh, M.; El-Maadawy, W.H.; Mohammed, H.S.; Khalil, H.; Botros, S.; Wink, M. Chemical Profiling of Polyphenolics in Eucalyptus globulus and Evaluation of Its Hepato-Renal Protective Potential against Cyclophosphamide Induced Toxicity in Mice. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Proestos, C.; Komaitis, M. Analysis of naturally occurring phenolic compounds in aromatic plants by RP-HPLC coupled to diode array detector (DAD) and GC-MS after silylation. Foods 2013, 2, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nile, S.H.; Keum, Y.S. Chemical composition, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and antitumor activities of Eucalyptus globulus Labill. Indian J. Exp. Biol. 2018, 56, 734–742. [Google Scholar]

- Bajpai, M.; Pande, A.; Tewari, S.; Prakash, D. Phenolic contents and antioxidant activity of some food and medicinal plants. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2005, 56, 287–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almeida, I.F.; Fernandes, E.; Lima, J.L.; Valentão, P.; Andrade, P.B.; Seabra, R.M.; Costa, P.; Bahia, M. Oxygen and nitrogen reactive species are effectively scavenged by Eucalyptus globulus leaf water extract. J. Med. Food 2009, 12, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puig, C.G.; Reigosa, M.J.; Valentao, P.; Andrade, P.B.; Pedrol, N. Unravelling the bioherbicide potential of Eucalyptus globulus Labill: Biochemistry and effects of its aqueous extract. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0192872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, B.; Hwang, E.; Seo, S.A.; Cho, J.G.; Yang, J.E.; Yi, T.H. Eucalyptus globulus extract protects against UVB-induced photoaging by enhancing collagen synthesis via regulation of TGF-beta/Smad signals and attenuation of AP-1. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2018, 637, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, J.; Allsop, D. Amyloid deposition as the central event in the aetiology of Alzheimer’s disease. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1991, 12, 383–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassar, R.; Bennett, B.D.; Babu-Khan, S.; Kahn, S.; Mendiaz, E.A.; Denis, P.; Teplow, D.B.; Ross, S.; Amarante, P.; Loeloff, R.; et al. Beta-secretase cleavage of Alzheimer’s amyloid precursor protein by the transmembrane aspartic protease BACE. Science 1999, 286, 735–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Koelsch, G.; Wu, S.; Downs, D.; Dashti, A.; Tang, J. Human aspartic protease memapsin 2 cleaves the beta-secretase site of beta-amyloid precursor protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 1456–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leissring, M.A.; Murphy, M.P.; Mead, T.R.; Akbari, Y.; Sugarman, M.C.; Jannatipour, M.; Anliker, B.; Muller, U.; Saftig, P.; De Strooper, B.; et al. A physiologic signaling role for the gamma -secretase-derived intracellular fragment of APP. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 4697–4702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, S.L.; Vassar, R. The Alzheimer’s disease beta-secretase enzyme, BACE1. Mol. Neurodegener. 2007, 2, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farzan, M.; Schnitzler, C.E.; Vasilieva, N.; Leung, D.; Choe, H. BACE2, a beta-secretase homolog, cleaves at the beta site and within the amyloid-beta region of the amyloid-beta precursor protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 9712–9717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dovey, H.F.; John, V.; Anderson, J.P.; Chen, L.Z.; de Saint Andrieu, P.; Fang, L.Y.; Freedman, S.B.; Folmer, B.; Goldbach, E.; Holsztynska, E.J.; et al. Functional gamma-secretase inhibitors reduce beta-amyloid peptide levels in brain. J. Neurochem. 2001, 76, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Citron, M. Alzheimer’s disease: Strategies for disease modification. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2010, 9, 387–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Strooper, B. Lessons from a failed gamma-secretase Alzheimer trial. Cell 2014, 159, 721–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oehlrich, D.; Berthelot, D.J.; Gijsen, H.J. gamma-Secretase modulators as potential disease modifying anti-Alzheimer’s drugs. J. Med. Chem 2011, 54, 669–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menting, K.W.; Claassen, J.A. beta-secretase inhibitor; a promising novel therapeutic drug in Alzheimer’s disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2014, 6, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangialasche, F.; Solomon, A.; Winblad, B.; Mecocci, P.; Kivipelto, M. Alzheimer’s disease: Clinical trials and drug development. Lancet Neurol. 2010, 9, 702–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadavath, H.; Hofele, R.V.; Biernat, J.; Kumar, S.; Tepper, K.; Urlaub, H.; Mandelkow, E.; Zweckstetter, M. Tau stabilizes microtubules by binding at the interface between tubulin heterodimers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 7501–7506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simic, G.; Babic Leko, M.; Wray, S.; Harrington, C.; Delalle, I.; Jovanov-Milosevic, N.; Bazadona, D.; Buee, L.; de Silva, R.; Di Giovanni, G.; et al. Tau Protein Hyperphosphorylation and Aggregation in Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Tauopathies, and Possible Neuroprotective Strategies. Biomolecules 2016, 6, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grill, J.D.; Cummings, J.L. Current therapeutic targets for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Expert Rev. Neurother. 2010, 10, 711–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.L.; Wang, C.; Jiang, T.; Tan, L.; Xing, A.; Yu, J.T. The Role of Cdk5 in Alzheimer’s Disease. Mol. Neurobiol. 2016, 53, 4328–4342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernandez, F.; Gomez de Barreda, E.; Fuster-Matanzo, A.; Lucas, J.J.; Avila, J. GSK3: A possible link between beta amyloid peptide and tau protein. Exp. Neurol. 2010, 223, 322–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pei, J.J.; Tanaka, T.; Tung, Y.C.; Braak, E.; Iqbal, K.; Grundke-Iqbal, I. Distribution, levels, and activity of glycogen synthase kinase-3 in the Alzheimer disease brain. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 1997, 56, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phiel, C.J.; Wilson, C.A.; Lee, V.M.; Klein, P.S. GSK-3alpha regulates production of Alzheimer’s disease amyloid-beta peptides. Nature 2003, 423, 435–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwak, H.M.; Jeon, S.Y.; Sohng, B.H.; Kim, J.G.; Lee, J.M.; Lee, K.B.; Jeong, H.H.; Hur, J.M.; Kang, Y.H.; Song, K.S. beta-Secretase (BACE1) inhibitors from pomegranate (Punica granatum) husk. Arch. Pharm Res. 2005, 28, 1328–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, Y.; Yang, S.G.; Du, X.T.; Zhang, X.; Sun, X.X.; Zhao, M.; Sun, G.Y.; Liu, R.T. Ellagic acid promotes Abeta42 fibrillization and inhibits Abeta42-induced neurotoxicity. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2009, 390, 1250–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.C.; Juan, C.W.; Lin, C.S.; Chen, C.C.; Chang, C.L. Neuroprotective Effect of Terminalia Chebula Extracts and Ellagic Acid in Pc12 Cells. Afr J. Tradit. Complement. Altern. Med. 2017, 14, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, A.B.; Panchal, S.S.; Shah, A. Ellagic acid: Insights into its neuroprotective and cognitive enhancement effects in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease. Pharm. Biochem. Behav. 2018, 175, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, L.; Liu, H.; Zhang, W.; Liu, X.; Jiang, B.; Fei, H.; Sun, Z. Ellagic acid ameliorates learning and memory impairment in APP/PS1 transgenic mice via inhibition of beta-amyloid production and tau hyperphosphorylation. Exp. Med. 2018, 16, 4951–4958. [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez-Aliaga, K.; Bermejo-Bescos, P.; Benedi, J.; Martin-Aragon, S. Quercetin and rutin exhibit antiamyloidogenic and fibril-disaggregating effects in vitro and potent antioxidant activity in APPswe cells. Life Sci. 2011, 89, 939–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.W.; Wang, Y.J.; Su, Y.J.; Zhou, W.W.; Yang, S.G.; Zhang, R.; Zhao, M.; Li, Y.N.; Zhang, Z.P.; Zhan, D.W.; et al. Rutin inhibits beta-amyloid aggregation and cytotoxicity, attenuates oxidative stress, and decreases the production of nitric oxide and proinflammatory cytokines. Neurotoxicology 2012, 33, 482–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.; Park, B.S.; Lee, K.G.; Choi, C.Y.; Jang, S.S.; Kim, Y.H.; Lee, S.E. Effects of naturally occurring compounds on fibril formation and oxidative stress of beta-amyloid. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 8537–8541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ono, K.; Yoshiike, Y.; Takashima, A.; Hasegawa, K.; Naiki, H.; Yamada, M. Potent anti-amyloidogenic and fibril-destabilizing effects of polyphenols in vitro: Implications for the prevention and therapeutics of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurochem. 2003, 87, 172–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Descamps, O.; Spilman, P.; Zhang, Q.; Libeu, C.P.; Poksay, K.; Gorostiza, O.; Campagna, J.; Jagodzinska, B.; Bredesen, D.E.; John, V. AβPP-selective BACE inhibitors (ASBI): Novel class of therapeutic agents for Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. JAD 2013, 37, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, S.H.; Scott, C.J.; Hamlin, A.S.; Obied, H.K. Biophenols: Enzymes (beta-secretase, Cholinesterases, histone deacetylase and tyrosinase) inhibitors from olive (Olea europaea L.). Fitoterapia 2018, 128, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimmyo, Y.; Kihara, T.; Akaike, A.; Niidome, T.; Sugimoto, H. Flavonols and flavones as BACE-1 inhibitors: Structure–activity relationship in cell-free, cell-based and in silico studies reveal novel pharmacophore features. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Gen. Subj. 2008, 1780, 819–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paris, D.; Mathura, V.; Ait-Ghezala, G.; Beaulieu-Abdelahad, D.; Patel, N.; Bachmeier, C.; Mullan, M. Flavonoids lower Alzheimer’s Aβ production via an NFκB dependent mechanism. Bioinformation 2011, 6, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espargaro, A.; Ginex, T.; Vadell, M.D.; Busquets, M.A.; Estelrich, J.; Munoz-Torrero, D.; Luque, F.J.; Sabate, R. Combined in Vitro Cell-Based/in Silico Screening of Naturally Occurring Flavonoids and Phenolic Compounds as Potential Anti-Alzheimer Drugs. J. Nat. Prod. 2017, 80, 278–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Luo, T.; Li, S.; Zhou, Y.; Shen, X.Y.; He, F.; Xu, J.; Wang, H.Q. Quercetin Protects against Okadaic Acid-Induced Injury via MAPK and PI3K/Akt/GSK3beta Signaling Pathways in HT22 Hippocampal Neurons. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0152371. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, X.Y.; Luo, T.; Li, S.; Ting, O.Y.; He, F.; Xu, J.; Wang, H.Q. Quercetin inhibits okadaic acid-induced tau protein hyperphosphorylation through the Ca2+-calpain-p25-CDK5 pathway in HT22 cells. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2018, 41, 1138–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Z.; Luan, G.; Wang, Z.; Hao, X.; Li, J.; Suo, Y.; Li, G.; Wang, H. Flavonoids from Potentilla parvifolia Fisch. and Their Neuroprotective Effects in Human Neuroblastoma SH-SY 5Y Cells in vitro. Chem. Biodivers. 2017, 14, e1600487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Deng, X.; Liu, N.; Li, M.; Liu, B.; Fu, Q.; Qu, R.; Ma, S. Quercetin attenuates tau hyperphosphorylation and improves cognitive disorder via suppression of ER stress in a manner dependent on AMPK pathway. J. Funct. Foods 2016, 22, 463–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagota, S.; Rajadas, J. Effect of phenolic compounds against Aβ aggregation and Aβ-induced toxicity in transgenic C. elegans. Neurochem. Res. 2012, 37, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Regitz, C.; Dussling, L.M.; Wenzel, U. Amyloid-beta (Abeta(1)(-)(4)(2))-induced paralysis in Caenorhabditis elegans is inhibited by the polyphenol quercetin through activation of protein degradation pathways. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2014, 58, 1931–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.M.; Li, S.Q.; Wu, W.L.; Zhu, X.Y.; Wang, Y.; Yuan, H.Y. Effects of long-term treatment with quercetin on cognition and mitochondrial function in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurochem. Res. 2014, 39, 1533–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabogal-Guaqueta, A.M.; Munoz-Manco, J.I.; Ramirez-Pineda, J.R.; Lamprea-Rodriguez, M.; Osorio, E.; Cardona-Gomez, G.P. The flavonoid quercetin ameliorates Alzheimer’s disease pathology and protects cognitive and emotional function in aged triple transgenic Alzheimer’s disease model mice. Neuropharmacology 2015, 93, 134–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paula, P.C.; Angelica Maria, S.G.; Luis, C.H.; Gloria Patricia, C.G. Preventive Effect of Quercetin in a Triple Transgenic Alzheimer’s Disease Mice Model. Molecules 2019, 24, 2287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Restrepo, F.; Sabogal-Guaqueta, A.M.; Cardona-Gomez, G.P. Quercetin ameliorates inflammation in CA1 hippocampal region in aged triple transgenic Alzheimer s disease mice model. Biomedica 2018, 38, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Hu, J.; Zhong, L.; Wang, N.; Yang, L.; Liu, C.C.; Li, H.; Wang, X.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Quercetin stabilizes apolipoprotein E and reduces brain Abeta levels in amyloid model mice. Neuropharmacology 2016, 108, 179–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Liu, Q.; Yu, Q. Quercetin enrich diet during the early-middle not middle-late stage of alzheimer’s disease ameliorates cognitive dysfunction. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2018, 10, 1237. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Woo, M.; Noh, J.S.; Cho, E.J.; Song, Y.O. Bioactive Compounds of Kimchi Inhibit Apoptosis by Attenuating Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress in the Brain of Amyloid beta-Injected Mice. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 4883–4890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Tian, Q.; Li, Z.; Dang, M.; Lin, Y.; Hou, X. Activation of Nrf2 signaling by sitagliptin and quercetin combination against beta-amyloid induced Alzheimer’s disease in rats. Drug Dev. Res. 2019, 80, 837–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, P.-X.; Wang, S.-W.; Yu, X.-L.; Su, Y.-J.; Wang, T.; Zhou, W.-W.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Y.-J.; Liu, R.-T. Rutin improves spatial memory in Alzheimer’s disease transgenic mice by reducing Aβ oligomer level and attenuating oxidative stress and neuroinflammation. Behav. Brain Res. 2014, 264, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lovell, M.A.; Markesbery, W.R. Oxidative DNA damage in mild cognitive impairment and late-stage Alzheimer’s disease. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35, 7497–7504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunomura, A.; Castellani, R.J.; Zhu, X.; Moreira, P.I.; Perry, G.; Smith, M.A. Involvement of oxidative stress in Alzheimer disease. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2006, 65, 631–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhao, B. Oxidative stress and the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Oxid Med. Cell Longev. 2013, 2013, 316523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizuno, D.; Konoha-Mizuno, K.; Mori, M.; Yamazaki, K.; Haneda, T.; Koyama, H.; Kawahara, M. An In Vitro System Comprising Immortalized Hypothalamic Neuronal Cells (GT1-7 Cells) for Evaluation of the Neuroendocrine Effects of Essential Oils. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2015, 2015, 343942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, S.; Park, H.; Seol, G.H.; Choi, I.Y. 1,8-Cineole ameliorates oxygen-glucose deprivation/reoxygenation-induced ischaemic injury by reducing oxidative stress in rat cortical neuron/glia. J. Pharm. Pharm. 2014, 66, 1818–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Vaibhav, K.; Javed, H.; Tabassum, R.; Ahmed, M.E.; Khan, M.M.; Khan, M.B.; Shrivastava, P.; Islam, F.; Siddiqui, M.S.; et al. 1,8-cineole (eucalyptol) mitigates inflammation in amyloid Beta toxicated PC12 cells: Relevance to Alzheimer’s disease. Neurochem. Res. 2014, 39, 344–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.Y.; Lee, C.; Park, G.H.; Jang, J.H. Amelioration of Scopolamine-Induced Learning and Memory Impairment by alpha-Pinene in C57BL/6 Mice. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2017, 2017, 4926815. [Google Scholar]

- Branca, C.; Ferreira, E.; Nguyen, T.V.; Doyle, K.; Caccamo, A.; Oddo, S. Genetic reduction of Nrf2 exacerbates cognitive deficits in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2017, 26, 4823–4835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahn, G.; Jo, D.G. Therapeutic Approaches to Alzheimer’s Disease Through Modulation of NRF2. Neuromol. Med. 2019, 21, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kabiraj, P.; Marin, J.E.; Varela-Ramirez, A.; Zubia, E.; Narayan, M. Ellagic acid mitigates SNO-PDI induced aggregation of Parkinsonian biomarkers. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2014, 5, 1209–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiasalari, Z.; Heydarifard, R.; Khalili, M.; Afshin-Majd, S.; Baluchnejadmojarad, T.; Zahedi, E.; Sanaierad, A.; Roghani, M. Ellagic acid ameliorates learning and memory deficits in a rat model of Alzheimer’s disease: An exploration of underlying mechanisms. Psychopharmacology 2017, 234, 1841–1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Bansal, N. Ellagic acid prevents dementia through modulation of PI3-kinase-endothelial nitric oxide synthase signalling in streptozotocin-treated rats. Naunyn-Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharm. 2018, 391, 987–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, N.; Yadav, P.; Kumar, M. Ellagic Acid Administration Negated the Development of Streptozotocin-Induced Memory Deficit in Rats. Drug Res. 2017, 67, 425–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzar, E.; Alp, H.; Cevik, M.U.; Firat, U.; Evliyaoglu, O.; Tufek, A.; Altun, Y. Ellagic acid attenuates oxidative stress on brain and sciatic nerve and improves histopathology of brain in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Neurol. Sci. 2012, 33, 567–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.M.; Kim, B.C.; Cho, Y.H.; Choi, K.H.; Chang, J.; Park, M.S.; Kim, M.K.; Cho, K.H.; Kim, J.K. Effects of Flavonoid Compounds on beta-amyloid-peptide-induced Neuronal Death in Cultured Mouse Cortical Neurons. Chonnam Med. J. 2014, 50, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.L.; Li, Y.N.; Zhang, H.; Su, Y.J.; Zhou, W.W.; Zhang, Z.P.; Wang, S.W.; Xu, P.X.; Wang, Y.J.; Liu, R.T. Rutin inhibits amylin-induced neurocytotoxicity and oxidative stress. Food Funct. 2015, 6, 3296–3306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, H.J.; Lee, C.Y. Protective effects of quercetin and vitamin C against oxidative stress-induced neurodegeneration. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004, 52, 7514–7517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ansari, M.A.; Abdul, H.M.; Joshi, G.; Opii, W.O.; Butterfield, D.A. Protective effect of quercetin in primary neurons against Abeta(1-42): Relevance to Alzheimer’s disease. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2009, 20, 269–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godoy, J.A.; Lindsay, C.B.; Quintanilla, R.A.; Carvajal, F.J.; Cerpa, W.; Inestrosa, N.C. Quercetin Exerts Differential Neuroprotective Effects Against H2O2 and Abeta Aggregates in Hippocampal Neurons: The Role of Mitochondria. Mol. Neurobiol. 2017, 54, 7116–7128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; McGeer, E.G.; McGeer, P.L. Quercetin, not caffeine, is a major neuroprotective component in coffee. Neurobiol. Aging 2016, 46, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, H.; Khan, M.M.; Ahmad, A.; Vaibhav, K.; Ahmad, M.E.; Khan, A.; Ashafaq, M.; Islam, F.; Siddiqui, M.S.; Safhi, M.M.; et al. Rutin prevents cognitive impairments by ameliorating oxidative stress and neuroinflammation in rat model of sporadic dementia of Alzheimer type. Neuroscience 2012, 210, 340–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.Y.; Lee, J.M.; Lee, D.G.; Cho, S.; Yoon, Y.H.; Cho, E.J.; Lee, S. The n-Butanol Fraction and Rutin from Tartary Buckwheat Improve Cognition and Memory in an In Vivo Model of Amyloid-beta-Induced Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Med. Food 2015, 18, 631–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, J.; Zhou, Q.; Du, Y.; Zhang, W.; Bai, M.; Zhang, Z.; Xi, Y.; Li, Z.; Miao, J. Rutin protects against cognitive deficits and brain damage in rats with chronic cerebral hypoperfusion. Br. J. Pharm. 2014, 171, 3702–3715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramalingayya, G.V.; Cheruku, S.P.; Nayak, P.G.; Kishore, A.; Shenoy, R.; Rao, C.M.; Krishnadas, N. Rutin protects against neuronal damage in vitro and ameliorates doxorubicin-induced memory deficits in vivo in Wistar rats. Drug Des. Devel. 2017, 11, 1011–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tota, S.; Awasthi, H.; Kamat, P.K.; Nath, C.; Hanif, K. Protective effect of quercetin against intracerebral streptozotocin induced reduction in cerebral blood flow and impairment of memory in mice. Behav. Brain Res. 2010, 209, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciel, R.M.; Carvalho, F.B.; Olabiyi, A.A.; Schmatz, R.; Gutierres, J.M.; Stefanello, N.; Zanini, D.; Rosa, M.M.; Andrade, C.M.; Rubin, M.A.; et al. Neuroprotective effects of quercetin on memory and anxiogenic-like behavior in diabetic rats: Role of ectonucleotidases and acetylcholinesterase activities. Biomed. Pharm. 2016, 84, 559–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, G.N.; Kim, J.H.; Kwak, J.H.; Jeong, C.-H.; Jeong, H.R.; Lee, U.; Heo, H.J. Effect of quercetin on learning and memory performance in ICR mice under neurotoxic trimethyltin exposure. Food Chem. 2012, 132, 1019–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Lee, J.; Lee, S.; Cho, E.J. Quercetin and quercetin-3-β-d-glucoside improve cognitive and memory function in Alzheimer’s disease mouse. Appl. Biol. Chem. 2016, 59, 721–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Ali, T.; Rehman, S.U.; Khan, M.S.; Alam, S.I.; Ikram, M.; Muhammad, T.; Saeed, K.; Badshah, H.; Kim, M.O. Neuroprotective Effect of Quercetin Against the Detrimental Effects of LPS in the Adult Mouse Brain. Front. Pharm. 2018, 9, 1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moghbelinejad, S.; Nassiri-Asl, M.; Farivar, T.N.; Abbasi, E.; Sheikhi, M.; Taghiloo, M.; Farsad, F.; Samimi, A.; Hajiali, F. Rutin activates the MAPK pathway and BDNF gene expression on beta-amyloid induced neurotoxicity in rats. Toxicol Lett. 2014, 224, 108–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Zhang, T.T.; Zhou, D.; Bai, X.Y.; Zhou, W.L.; Huang, C.; Song, J.K.; Meng, F.R.; Wu, C.X.; Li, L.; et al. Quercetin protects against the Abeta(25-35)-induced amnesic injury: Involvement of inactivation of rage-mediated pathway and conservation of the NVU. Neuropharmacology 2013, 67, 419–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, N. ER Stress, CREB, and Memory: A Tangled Emerging Link in Disease. Neuroscientist 2019, 25, 420–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Placido, A.I.; Pereira, C.M.; Duarte, A.I.; Candeias, E.; Correia, S.C.; Carvalho, C.; Cardoso, S.; Oliveira, C.R.; Moreira, P.I. Modulation of endoplasmic reticulum stress: An opportunity to prevent neurodegeneration? CNS Neurol. Disord. Drug Targets 2015, 14, 518–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, P.; Ron, D. The unfolded protein response: From stress pathway to homeostatic regulation. Science 2011, 334, 1081–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.H.; Iwakoshi, N.N.; Glimcher, L.H. XBP-1 regulates a subset of endoplasmic reticulum resident chaperone genes in the unfolded protein response. Mol. Cell Biol. 2003, 23, 7448–7459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hetz, C.; Chevet, E.; Oakes, S.A. Proteostasis control by the unfolded protein response. Nat. Cell Biol. 2015, 17, 829–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harding, H.P.; Zhang, Y.; Bertolotti, A.; Zeng, H.; Ron, D. Perk is essential for translational regulation and cell survival during the unfolded protein response. Mol. Cell 2000, 5, 897–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harding, H.P.; Zhang, Y.; Zeng, H.; Novoa, I.; Lu, P.D.; Calfon, M.; Sadri, N.; Yun, C.; Popko, B.; Paules, R.; et al. An integrated stress response regulates amino acid metabolism and resistance to oxidative stress. Mol. Cell 2003, 11, 619–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabas, I.; Ron, D. Integrating the mechanisms of apoptosis induced by endoplasmic reticulum stress. Nat. Cell Biol. 2011, 13, 184–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsaytler, P.; Bertolotti, A. Exploiting the selectivity of protein phosphatase 1 for pharmacological intervention. FEBS J. 2013, 280, 766–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayakawa, M.; Itoh, M.; Ohta, K.; Li, S.; Ueda, M.; Wang, M.X.; Nishida, E.; Islam, S.; Suzuki, C.; Ohzawa, K.; et al. Quercetin reduces eIF2alpha phosphorylation by GADD34 induction. Neurobiol. Aging 2015, 36, 2509–2518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heneka, M.T.; Carson, M.J.; El Khoury, J.; Landreth, G.E.; Brosseron, F.; Feinstein, D.L.; Jacobs, A.H.; Wyss-Coray, T.; Vitorica, J.; Ransohoff, R.M.; et al. Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2015, 14, 388–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.S.; Joh, T.H. Microglia, major player in the brain inflammation: Their roles in the pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease. Exp. Mol. Med. 2006, 38, 333–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldgaber, D.; Harris, H.W.; Hla, T.; Maciag, T.; Donnelly, R.J.; Jacobsen, J.S.; Vitek, M.P.; Gajdusek, D.C. Interleukin 1 regulates synthesis of amyloid beta-protein precursor mRNA in human endothelial cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1989, 86, 7606–7610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintanilla, R.A.; Orellana, D.I.; Gonzalez-Billault, C.; Maccioni, R.B. Interleukin-6 induces Alzheimer-type phosphorylation of tau protein by deregulating the cdk5/p35 pathway. Exp. Cell Res. 2004, 295, 245–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinney, J.W.; Bemiller, S.M.; Murtishaw, A.S.; Leisgang, A.M.; Salazar, A.M.; Lamb, B.T. Inflammation as a central mechanism in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2018, 4, 575–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, W.S.; Stanley, L.C.; Ling, C.; White, L.; MacLeod, V.; Perrot, L.J.; White, C.L., 3rd; Araoz, C. Brain interleukin 1 and S-100 immunoreactivity are elevated in Down syndrome and Alzheimer disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1989, 86, 7611–7615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, J.; Luber-Narod, J.; Styren, S.D.; Civin, W.H. Expression of immune system-associated antigens by cells of the human central nervous system: Relationship to the pathology of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging 1988, 9, 339–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasparini, L.; Ongini, E.; Wenk, G. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) in Alzheimer’s disease: Old and new mechanisms of action. J. Neurochem. 2004, 91, 521–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breitner, J.C. Inflammatory processes and antiinflammatory drugs in Alzheimer’s disease: A current appraisal. Neurobiol. Aging 1996, 17, 789–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, M.A.; Raju, R.; Beattie, K.D.; Bodkin, F.; Munch, G. Medicinal Plants of the Australian Aboriginal Dharawal People Exhibiting Anti-Inflammatory Activity. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2016, 2016, 2935403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojanathammanee, L.; Puig, K.L.; Combs, C.K. Pomegranate polyphenols and extract inhibit nuclear factor of activated T-cell activity and microglial activation in vitro and in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer disease. J. Nutr. 2013, 143, 597–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bispo da Silva, A.; Cerqueira Coelho, P.L.; Alves Oliveira Amparo, J.; Alves de Almeida Carneiro, M.M.; Pereira Borges, J.M.; Dos Santos Souza, C.; Dias Costa, M.F.; Mecha, M.; Guaza Rodriguez, C.; Amaral da Silva, V.D.; et al. The flavonoid rutin modulates microglial/macrophage activation to a CD150/CD206 M2 phenotype. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2017, 274, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, A.G.; Upton, J.-P.; Praveen, P.; Ghosh, R.; Nakagawa, Y.; Igbaria, A.; Shen, S.; Nguyen, V.; Backes, B.J.; Heiman, M. IRE1α induces thioredoxin-interacting protein to activate the NLRP3 inflammasome and promote programmed cell death under irremediable ER stress. Cell Metab. 2012, 16, 250–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.H.; Murphy, E.A.; McClellan, J.L.; Carmichael, M.D.; Davis, J.M. The dietary flavonoid quercetin decreases neuroinflammation in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. FASEB J. 2010, 24, 604–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, P.T.; Palmer, A.M.; Snape, M.; Wilcock, G.K. The cholinergic hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease: A review of progress. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 1999, 66, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappas, B.A.; Bayley, P.J.; Bui, B.K.; Hansen, L.A.; Thal, L.J. Choline acetyltransferase activity and cognitive domain scores of Alzheimer’s patients. Neurobiol. Aging 2000, 21, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyaya, P.; Seth, V.; Ahmad, M. Therapy of Alzheimer’s disease: An update. Afr. J. Pharm. Pharm. 2010, 4, 408–421. [Google Scholar]

- McGleenon, B.M.; Dynan, K.B.; Passmore, A.P. Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors in Alzheimer’s disease. Br. J. Clin. Pharm. 1999, 48, 471–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burcul, F.; Blazevic, I.; Radan, M.; Politeo, O. Terpenes, Phenylpropanoids, Sulfur and Other Essential Oil Constituents as Inhibitors of Cholinesterases. Curr. Med. Chem. 2020, 27, 4297–4343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaufmann, D.; Dogra, A.K.; Wink, M. Myrtenal inhibits acetylcholinesterase, a known Alzheimer target. J. Pharm. Pharm. 2011, 63, 1368–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ademosun, A.O.; Oboh, G.; Bello, F.; Ayeni, P.O. Antioxidative Properties and Effect of Quercetin and Its Glycosylated Form (Rutin) on Acetylcholinesterase and Butyrylcholinesterase Activities. J. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2016, 21, NP11–NP17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]