Effect of NK-5962 on Gene Expression Profiling of Retina in a Rat Model of Retinitis Pigmentosa

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

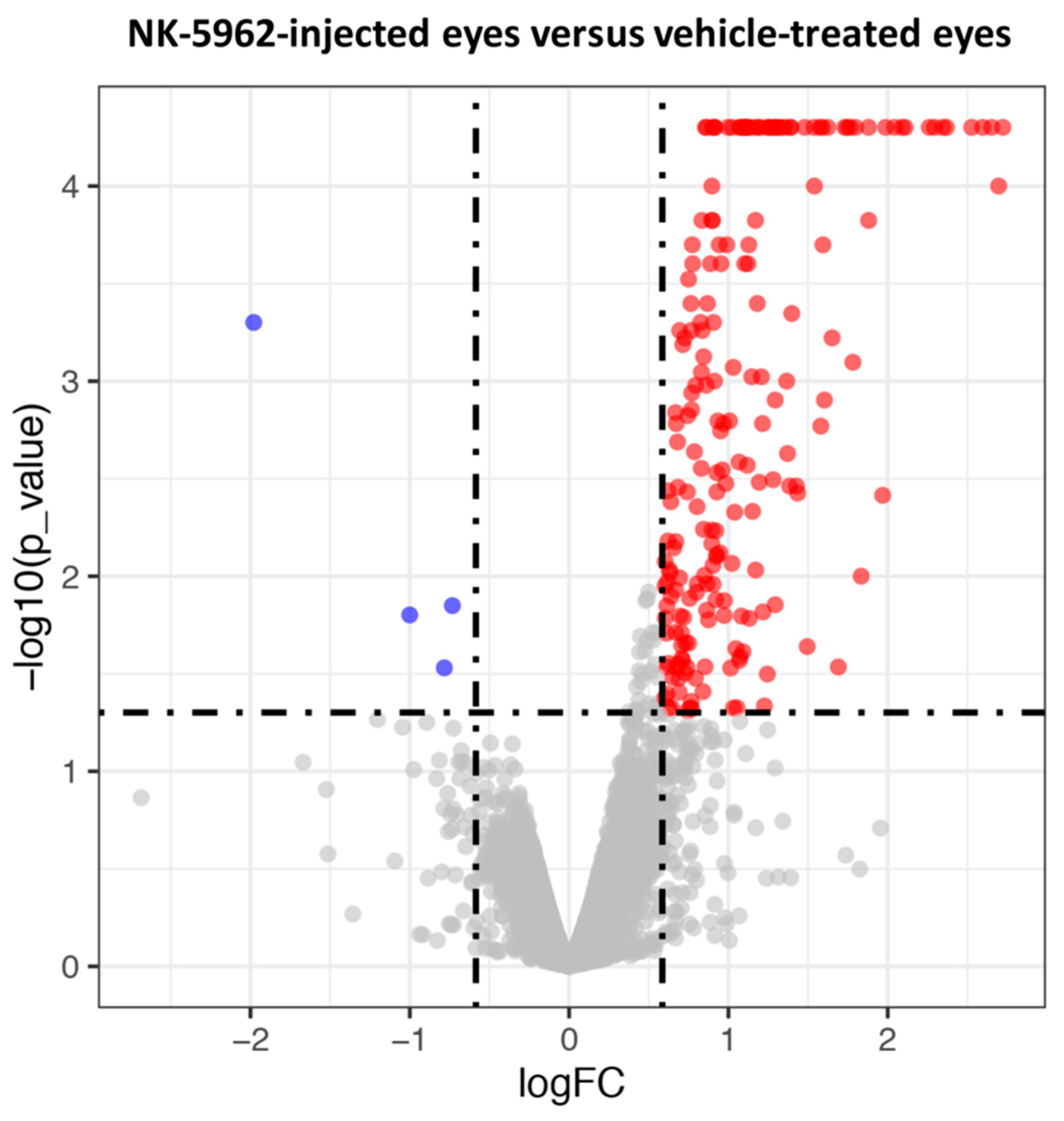

2.1. Screening of DEGs in the Eyes Injected with NK-5962

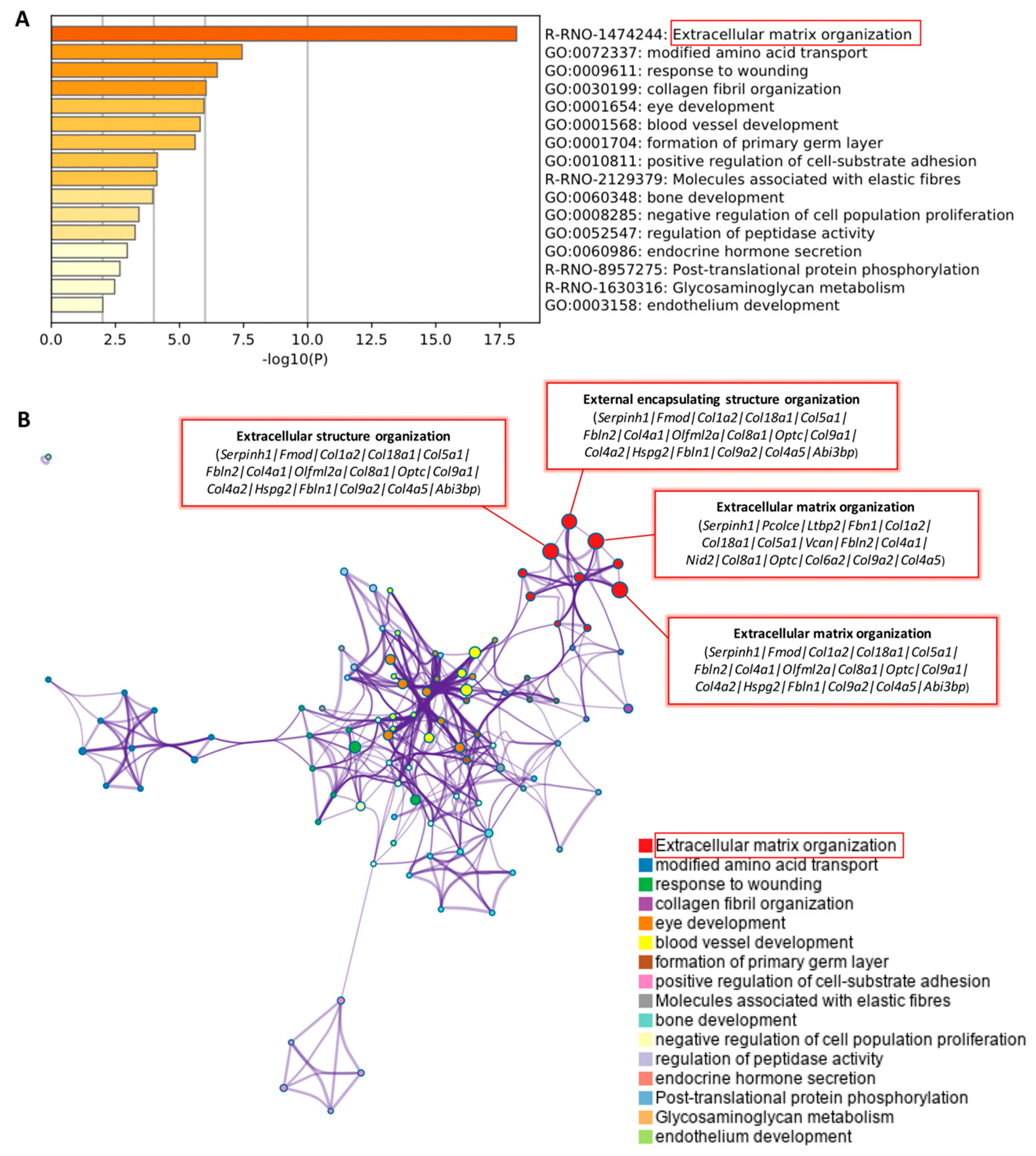

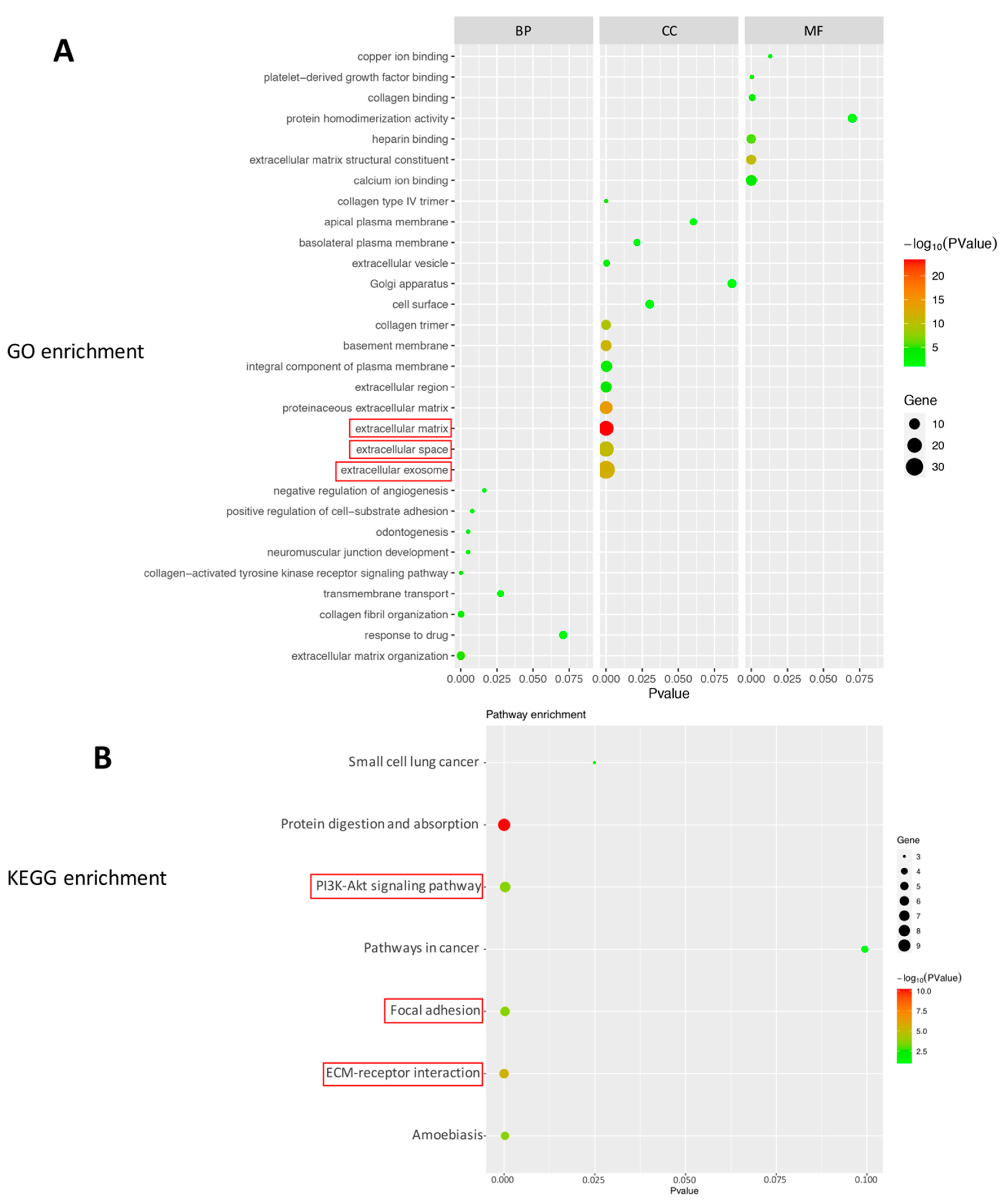

2.2. Bioinformatics Analysis of DEGs in the Eyes Injected with NK-5962

3. Discussion

4. Methods

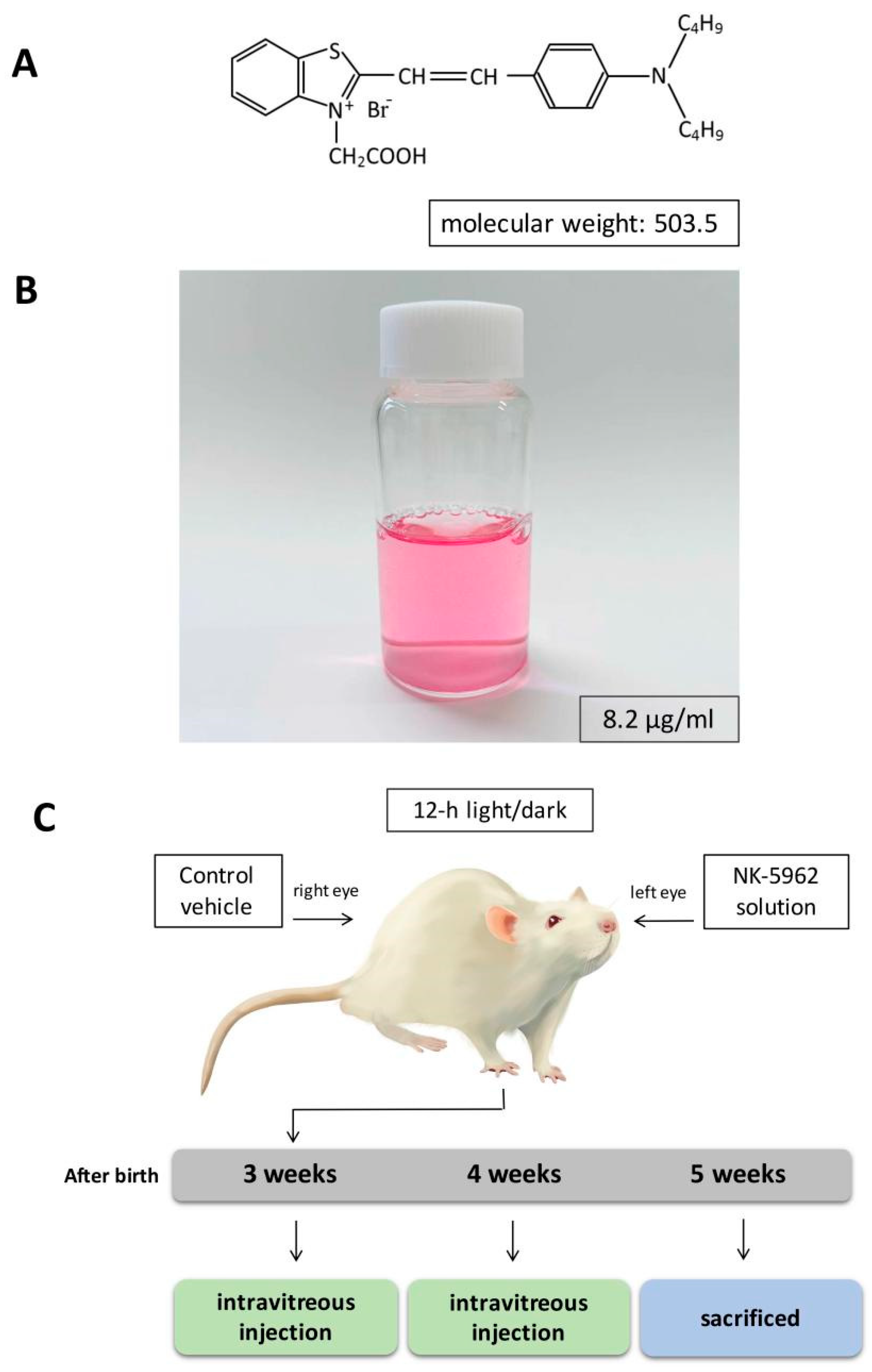

4.1. Chemicals and Preparations

4.2. Animals

4.3. RNA Extraction

4.4. RNA Sequencing

4.5. Bioinformatics Analysis

4.6. Data Availability

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hamel, C. Retinitis pigmentosa. Orphanet. J. Rare Dis. 2006, 1, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faktorovich, E.G.; Steinberg, R.H.; Yasumura, D.; Matthes, M.T.; Lavail, M.M. Photoreceptor degeneration in inherited retinal dystrophy delayed by basic fibroblast growth factor. Nature 1990, 347, 83–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaVail, M.M.; Unoki, K.; Yasumura, D.; Matthes, M.T.; Yancopoulos, G.D.; Steinberg, R.H. Multiple growth factors, cytokines, and neurotrophins rescue photoreceptors from the dam-aging effects of constant light. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 1992, 89, 11249–11253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rezaie, T.; McKercher, S.R.; Kosaka, K.; Seki, M.; Wheeler, L.; Viswanath, V.; Chun, T.; Joshi, R.; Valencia, M.; Sasaki, S.; et al. Protective effect of carnosic acid, a pro-electrophilic compound, in models of oxidative stress and light-induced retinal degeneration. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2012, 53, 7847–7854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanz, M.; Johnson, L.; Ahuja, S.; Ekström, P.; Romero, J.; van Veen, T. Significant photoreceptor rescue by treatment with a combination of antioxidants in an animal model for retinal degeneration. Neuroscience 2007, 145, 1120–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Matsuo, T.; Miyaji, M.; Hosoya, O. The Effect of Cyanine Dye NK-4 on Photoreceptor Degeneration in a Rat Model of Early-Stage Retinitis Pigmentosa. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Poulaki, V.; Kim, S.-J.; Eldred, W.D.; Kane, S.; Gingerich, M.; Shire, D.B.; Jensen, R.; DeWalt, G.; Kaplan, H.J.; et al. Implantation and Extraction of Penetrating Electrode Arrays in Minipig Retinas. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 2020, 9, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuo, T.; Uchida, T.; Sakurai, J.; Yamashita, K.; Matsuo, C.; Araki, T.; Yamashita, Y.; Kamikawa, K. Visual Evoked Potential Recovery by Subretinal Implantation of Photoelectric Dye-Coupled Thin Film Retinal Prosthesis in Monkey Eyes With Macular Degeneration. Artif. Organs. 2018, 42, E186–E203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; da Cruz, L. The Argus(®) II retinal prosthesis system. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2016, 50, 89–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maya-Vetencourt, J.F.; Manfredi, G.; Mete, M.; Colombo, E.; Bramini, M.; Di Marco, S.; Shmal, D.; Mantero, G.; Dipalo, M.; Rocchi, A.; et al. Subretinally injected semiconducting polymer nanoparticles rescue vision in a rat model of retinal dystrophy. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2020, 15, 698–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maya-Vetencourt, J.F.; Di Marco, S.; Mete, M.; Di Paolo, M.; Ventrella, D.; Barone, F.; Elmi, A.; Manfredi, G.; Desii, A.; Sannita, W.G.; et al. Biocompatibility of a Conjugated Polymer Retinal Prosthesis in the Do-mestic Pig. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 15, 579141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maya-Vetencourt, J.F.; Ghezzi, D.; Antognazza, M.R.; Colombo, E.; Mete, M.; Feyen, P.; Desii, A.; Buschiazzo, A.; Di Paolo, M.; Di Marco, S.; et al. A fully organic retinal prosthesis restores vision in a rat model of degenerative blindness. Nat. Mater. 2017, 16, 681–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cehajic-Kapetanovic, J.; Xue, K.; Martinez-Fernandez de la Camara, C.; Nanda, A.; Davies, A.; Wood, L.J.; Salvetti, A.P.; Fischer, M.D.; Aylward, J.W.; Barnard, A.R.; et al. Initial results from a first-in-human gene therapy trial on X-linked retinitis pig-mentosa caused by mutations in RPGR. Nat. Med. 2020, 26, 354–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourne, M.C.; Campbell, D.A.; Tansley, K. Hereditary degeneration of the rat retina. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 1938, 22, 613–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bok, D.; Hall, M.O. The role of the pigment epithelium in the etiology of inherited retinal dystrophy in the rat. J. Cell Biol. 1971, 49, 664–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullen, R.J.; LaVail, M.M. Inherited retinal dystrophy: Primary defect in pigment epithelium determined with ex-perimental rat chimeras. Science 1976, 192, 799–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowling, J.E.; Sidman, R.L. Inherited retinal dystrophy in the rat. J. Cell Biol. 1962, 14, 73–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuo, T. A simple method for screening photoelectric dyes towards their use for retinal prosthese. Acta Med. Okayama 2003, 57, 257–260. [Google Scholar]

- Matsuo, T.; Dan-oh, Y.; Suga, S. Agent for Inducing Receptor Potential. U.S. Patent US7,101,533 B2, 5 September 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Matsuo, T.; Sakurai, M.; Terada, K.; Uchida, T.; Yamashita, K.; Tanaka, T.; Takarabe, K. Photoelectric Dye-Coupled Polyethylene Film: Photoresponsive Properties Evaluated by Kelvin Probe and In Vitro Biological Response Detected in Dystrophic Retinal Tissue of Rats. Adv. Biomed. Eng. 2019, 8, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuo, T.; Terada, K.; Sakurai, M.; Liu, S.; Yamashita, K.; Uchida, T. Step-by-step procedure to test photoelectric dye-coupled polyethylene film as retinal prosthesis to induce light-evoked spikes in isolated retinal dystrophic tissue of rd1 mice. Clin Surg. 2020, 5, 2903. [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto, K.; Matsuo, T.; Tamaki, T.; Uji, A.; Ohtsuki, H. Short-term biological safety of a photoelectric dye used as a component of retinal prostheses. J. Artif. Organs 2008, 11, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuo, T.; Hosoya, O.; Tsutsui, K.M.; Uchida, T. Vision maintenance and retinal apoptosis reduction in RCS rats with Okayama University-type retinal prosthesis (OUReP™) implantation. J. Artif. Organs. 2015, 18, 264–271. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Matsuo, T.; Hosoya, O.; Uchida, T. Photoelectric Dye Used for Okayama University-Type Retinal Prosthesis Reduces the Apoptosis of Photoreceptor Cells. J. Ocul. Pharmacol. Ther. 2017, 33, 149–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuo, T.; Liu, S.; Uchida, T.; Onoue, S.; Nakagawa, S.; Ishii, M.; Kanamitsu, K. Photoelectric Dye, NK-5962, as a Potential Drug for Preventing Retinal Neurons from Apoptosis: Pharmacokinetic Studies Based on Review of the Evidence. Life 2021, 11, 591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wacker, S.; Houghtaling, B.R.; Elemento, O.; Kapoor, T.M. Using transcriptome sequencing to identify mechanisms of drug action and resistance. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2012, 8, 235–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, S.; Polato, F.; Samardzija, M.; Abu-Asab, M.; Grimm, C.; Crawford, S.E.; Becerra, S.P. PEDF deficiency increases the susceptibility of rd10 mice to retinal degeneration. Exp. Eye Res. 2020, 198, 108121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valiente-Soriano, F.J.; Di Pierdomenico, J.; García-Ayuso, D.; Ortín-Martínez, A.; De Imperial-Ollero, J.A.M.; Gallego-Ortega, A.; Jiménez-López, M.; Villegas-Pérez, M.P.; Becerra, S.P.; Vidal-Sanz, M. Pigment Epithelium-Derived Factor (PEDF) Fragments Prevent Mouse Cone Photoreceptor Cell Loss Induced by Focal Phototoxicity In Vivo. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gould, D.B.; Marchant, J.K.; Savinova, O.V.; Smith, R.S.; John, S.W. Col4a1 mutation causes endoplasmic reticulum stress and genetically modifiable ocular dysgenesis. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2007, 16, 798–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Templeton, J.P.; Wang, X.; Freeman, N.E.; Ma, Z.; Lu, A.; Hejtmancik, F.; Geisert, E.E. A crystallin gene network in the mouse retina. Exp. Eye Res. 2013, 116, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kuo, D.S.; Labelle-Dumais, C.; Gould, D.B. COL4A1 and COL4A2 mutations and disease: Insights into pathogenic mechanisms and potential therapeutic targets. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2012, 21, R97–R110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, M.; Morita, H.; Sormunen, R.; Airenne, S.; Kreivi, M.; Wang, L.; Fukai, N.; Olsen, B.R.; Tryggvason, K.; Soininen, R. Heparan sulfate chains of perlecan are indispensable in the lens capsule but not in the kidney. EMBO J. 2003, 22, 236–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamer, W.D.; Bok, D.; Hu, J.; Jaffe, G.J.; McKay, B.S. Aquaporin-1 channels in human retinal pigment epithelium: Role in tran-sepithelial water movement. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2003, 44, 2803–2808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perucci, L.O.; Sugimoto, M.A.; Gomes, K.B.; Dusse, L.; Teixeira, M.M.; Sousa, L.P. Annexin A1 and specialized proresolving lipid mediators: Promoting resolution as a therapeutic strategy in human inflammatory diseases. Expert. Opin. Ther. Targets 2017, 21, 879–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porzionato, A.; Rucinski, M.; Macchi, V.; Sarasin, G.; Malendowicz, L.; De Caro, R. ECRG4 Expression in Normal Rat Tissues: Expression Study and Literature Review. Eur. J. Histochem. 2015, 59, 2458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capowski, E.E.; Wright, L.S.; Liang, K.; Phillips, M.J.; Wallace, K.; Petelinsek, A.; Hagstrom, A.; Pinilla, I.; Borys, K.; Lien, J.; et al. Regulation of WNT Signaling by VSX2 During Optic Vesicle Patterning in Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells. STEM CELLS 2016, 34, 2625–2634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlin, A.; Geier, E.; Stocker, S.L.; Cropp, C.D.; Grigorenko, E.; Bloomer, M.; Siegenthaler, J.; Xu, L.; Basile, A.S.; Tang-Liu, D.D.-S.; et al. Gene Expression Profiling of Transporters in the Solute Carrier and ATP-Binding Cassette Superfamilies in Human Eye Substructures. Mol. Pharm. 2013, 10, 650–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishizu, M.; Murakami, Y.; Fujiwara, K.; Funatsu, J.; Shimokawa, S.; Nakatake, S.; Tachibana, T.; Hisatomi, T.; Koyanagi, Y.; Akiyama, M.; et al. Relationships Between Serum Antioxidant and Oxidant Statuses and Visual Function in Retinitis Pigmentosa. Investig. Opthalmology Vis. Sci. 2019, 60, 4462–4468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Fernández de la Cámara, C.; Salom, D.; Sequedo, M.D.; Hervás, D.; Marín-Lambíes, C.; Aller, E.; Jaijo, T.; Díaz-LLopis, M.; Millán, J.M.; Rodrigo, R. Altered antioxidant-oxidant status in the aqueous humor and peripheral blood of patients with retinitis pigmentosa. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e74223. [Google Scholar]

- Kanan, Y.; Brobst, D.; Han, Z.; Naash, M.I.; Al-Ubaidi, M.R. Fibulin 2, a tyrosine O-sulfated protein, is up-regulated following retinal detachment. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 13419–13433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, J.S.; Faucher, M.; Hiscott, P.; Biron, V.L.; Malenfant, M.; Turcotte, P.; Raymond, V.; Walter, M.A. Protein localization in the human eye and genetic screen of opticin. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2002, 11, 1333–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, S.K.; Eiby, Y.; Lee, S.; Lingwood, B.E.; Dawson, P.A. Structure, organization and tissue expression of the pig SLC13A1 and SLC13A4 sulfate transporter genes. Biochem. Biophys. Rep. 2017, 10, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hochmann, S.; Kaslin, J.; Hans, S.; Weber, A.; Machate, A.; Geffarth, M.; Funk, R.H.W.; Brand, M. Fgf Signaling is Required for Photoreceptor Maintenance in the Adult Zebrafish Retina. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e30365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.J.; La Pierre, D.P.; Wu, J.; Yee, A.J.; Yang, B.B. The interaction of versican with its binding partners. Cell Res. 2005, 15, 483–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, C.; Li, P.; Bi, J.; Wu, Q.; Lu, L.; Qian, G.; Jia, R.; Jia, R. Differential expression of TYRP1 in adult human retinal pigment epithelium and uveal melanoma cells. Oncol. Lett. 2016, 11, 2379–2383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radeke, M.J.; Peterson, K.E.; Johnson, L.V.; Anderson, D.H. Disease susceptibility of the human macula: Differential gene transcription in the retinal pigmented epithelium/choroid. Exp. Eye Res. 2007, 85, 366–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, N.M.; Johnson, C.S.; de Souza, C.F.; Chee, K.-S.; Good, W.R.; Green, C.R.; Danesh-Meyer, H.V. Immunolocalization of Gap Junction Protein Connexin43 (GJA1) in the Human Retina and Optic Nerve. Investig. Opthalmology Vis. Sci. 2010, 51, 4028–4034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, A.R.; Khalaj, M.; Tsuji, T.; Tanahara, M.; Uchida, K.; Sugimoto, Y.; Kunieda, T. A mutation of the WFDC1 gene is responsible for multiple ocular defects in cattle. Genomics 2009, 94, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Jones, W.; Beatty, W.; Tan, Q.; Mecham, R.; Kumra, H.; Reinhardt, D.; Gibson, M.; Reilly, M.; Rodriguez, J.; et al. Latent-transforming growth factor beta-binding protein-2 (LTBP-2) is required for longevity but not for development of zonular fibers. Matrix Biol. 2020, 95, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daga, S.; Donati, F.; Capitani, K.; Croci, S.; Tita, R.; Giliberti, A.; Valentino, F.; Benetti, E.; Fallerini, C.; Niccheri, F.; et al. New frontiers to cure Alport syndrome: COL4A3 and COL4A5 gene editing in podocyte-lineage cells. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2019, 28, 480–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, X.; Li, H.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Zheng, Q.; Hua, J.; Yang, J.; Pan, L.; Lu, F.; Qu, J.; et al. DAPL1, a susceptibility locus for age-related macular degeneration, acts as a novel suppressor of cell proliferation in the retinal pigment epithelium. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2017, 26, 1612–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reigada, D.; Lu, W.; Zhang, X.; Friedman, C.; Pendrak, K.; McGlinn, A.; Stone, R.A.; Laties, A.M.; Mitchell, C.H. Degradation of extracellular ATP by the retinal pigment epithelium. Am. J. Physiol. Physiol. 2005, 289, C617–C624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strungaru, M.H.; Footz, T.; Liu, Y.; Berry, F.B.; Belleau, P.; Semina, E.V.; Raymond, V.; Walter, M.A. PITX2 Is Involved in Stress Response in Cultured Human Trabecular Meshwork Cells through Regulation of SLC13A3. Investig. Opthalmology Vis. Sci. 2011, 52, 7625–7633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R.; Kim, A.S.; Fox, J.M.; Nair, S.; Basore, K.; Klimstra, W.B.; Rimkunas, R.; Fong, R.H.; Lin, H.; Poddar, S. Mxra8 is a receptor for multiple arthritogenic alphaviruses. Nature 2018, 557, 570–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.-Y.; Olsen, B.R.; Kao, W.W.-Y. Developmental patterns of two α1(IX) collagen mRNA isoforms in mouse. Dev. Dyn. 1993, 198, 150–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilbao-Malavé, V.; Recalde, S.; Bezunartea, J.; Hernandez-Sanchez, M.; González-Zamora, J.; Maestre-Rellan, L.; Ruiz-Moreno, J.M.; Araiz-Iribarren, J.; Arias, L.; Ruiz-Medrano, J.; et al. Genetic and environmental factors related to the development of myopic maculopathy in Spanish patients. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0236071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kameya, S.; Hawes, N.L.; Chang, B.; Heckenlively, J.R.; Naggert, J.K.; Nishina, P.M. Mfrp, a gene encoding a frizzled related protein, is mutated in the mouse retinal degeneration 6. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2002, 11, 1879–1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayasarathy, C.; Zeng, Y.; Brooks, M.J.; Fariss, R.N.; Sieving, P.A. Genetic Rescue of X-Linked Retinoschisis Mouse (Rs1-/y) Retina Induces Quiescence of the Retinal Microglial Inflammatory State Following AAV8-RS1 Gene Transfer and Identifies Gene Networks Underlying Retinal Recovery. Hum. Gene Ther. 2020, 32, 667–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handford, P. Fibrillin-1, a calcium binding protein of extracellular matrix. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Bioenerg. 2000, 1498, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marneros, A.G.; Keene, U.R.; Hansen, U.; Fukai, N.; Moulton, K.; Goletz, P.L.; Moiseyev, G.; Pawlyk, B.S.; Halfter, W.; Dong, S.; et al. Collagen XVIII/endostatin is essential for vision and retinal pigment epithelial function. EMBO J. 2003, 23, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.; Laboulaye, M.A.; Tran, N.M.; Whitney, I.E.; Benhar, I.; Sanes, J.R. Mouse Retinal Cell Atlas: Molecular Identification of over Sixty Amacrine Cell Types. J. Neurosci. 2020, 40, 5177–5195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodgkinson, C.P.; Naidoo, V.; Patti, K.G.; Gomez, J.A.; Schmeckpeper, J.; Zhang, Z.; Davis, B.; Pratt, R.E.; Mirotsou, M.; Dzau, V.J. Abi3bp is a multifunctional autocrine/paracrine factor that regulates mesen-chymal stem cell biology. Stem Cells 2013, 31, 1669–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitmore, S.S.; Wagner, A.H.; DeLuca, A.P.; Drack, A.V.; Stone, E.M.; Tucker, B.A.; Zeng, S.; Braun, T.A.; Mullins, R.F.; Scheetz, T.E. Transcriptomic analysis across nasal, temporal, and macular regions of human neural retina and RPE/choroid by RNA-Seq. Exp. Eye Res. 2014, 129, 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, H.; Li, S.; Li, J.; Huang, C.; Zhou, F.; Zhao, L.; Yu, W.; Qin, X. Knockdown of Fibromodulin Inhibits Proliferation and Migration of RPE Cell via the VEGFR2-AKT Pathway. J. Ophthalmol. 2018, 2018, 5708537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, L.; Liu, Y.; Wei, C.; Jin, H.; Mei, L.; Wu, C. SERPINH1, Targeted by miR-29b, Modulated Proliferation and Migration of Human Retinal Endothelial Cells Under High Glucose Conditions. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2021, 14, 3471–3483. [Google Scholar]

- Pollard, R.D.; Blesso, C.N.; Zabalawi, M.; Fulp, B.; Gerelus, M.; Zhu, X.; Lyons, E.W.; Nuradin, N.; Francone, O.L.; Li, X.-A.; et al. Procollagen C-endopeptidase Enhancer Protein 2 (PCPE2) Reduces Athero-sclerosis in Mice by Enhancing Scavenger Receptor Class B1 (SR-BI)-mediated High-density Lipoprotein (HDL)-Cholesteryl Ester Uptake. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 15496–15511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Soleimani, M.; Hughes, B.A. SLC26A7 constitutes the thiocyanate-selective anion conductance of the basolateral membrane of the retinal pigment epithelium. Am. J. Physiol. Physiol. 2020, 319, C641–C656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, R.; Nie, Z.-T.; Liu, L.; Chang, Y.-W.; Shen, J.-Q.; Chen, Q.; Dong, L.-J.; Hu, B.-J. Follistatin-like protein 1 functions as a potential target of gene therapy in proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Aging 2021, 13, 8643–8664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Ibave, D.C.; González-Alvarez, R.; Martinez-Fierro, M.D.L.L.; Ruiz-Ayma, G.; Luna-Muñoz, M.; Martínez-De-Villarreal, L.E.; Garza-Rodríguez, M.D.L.; Reséndez-Pérez, D.; Mohamed-Noriega, J.; Garza-Guajardo, R.; et al. Olfactomedin-like 2 A and B (OLFML2A and OLFML2B) expression profile in primates (human and baboon). Biol. Res. 2016, 49, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obermann, J.; Priglinger, C.S.; Merl-Pham, J.; Geerlof, A.; Priglinger, S.; Götz, M.; Hauck, S.M. Proteome-wide Identification of Glycosylation-dependent Interactors of Galectin-1 and Galectin-3 on Mesenchymal Retinal Pigment Epithelial (RPE) Cells. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2017, 16, 1528–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaei, M.; Gupta, V.B.; Chick, J.M.; Greco, T.M.; Wu, Y.; Chitranshi, N.; Wall, R.V.; Hone, E.; Deng, L.; Dheer, Y.; et al. Age-related neurodegenerative disease associated pathways identified in retinal and vitreous proteome from human glaucoma eyes. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 12685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.; Luderer, U. Oxidative Damage Increases and Antioxidant Gene Expression Decreases with Aging in the Mouse Ovary. Biol. Reprod. 2011, 84, 775–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Clermont, A.C.; Gao, B.-B.; Feener, E.P. Intraocular Hemorrhage Causes Retinal Vascular Dysfunction via Plasma Kallikrein. Investig. Opthalmology Vis. Sci. 2013, 54, 1086–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, S.; Booth, C.; Fillman, C.; Shapiro, M.; Blair, M.P.; Hyland, J.C.; Ala-Kokko, L. A loss of function mutation in the COL9A2 gene causes autosomal recessive Stickler syndrome. Am. J. Med Genet. Part A 2011, 155, 1668–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giblin, M.; Penn, J.S. Cytokine-induced ECM alterations in DR pathogenesis. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2020, 61, 1766. [Google Scholar]

- Tangeman, J.; Luz-Madrigal, A.; Sreeskandarajan, S.; Grajales-Esquivel, E.; Liu, L.; Liang, C.; Tsonis, P.; Del Rio-Tsonis, K. Transcriptome Profiling of Embryonic Retinal Pigment Epithelium Reprogramming. Genes 2021, 12, 840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hubens, W.H.; Breddels, E.M.; Walid, Y.; Ramdas, W.D.; Webers, C.A.; Gorgels, T.G. Mapping mRNA Expression of Glaucoma Genes in the Healthy Mouse Eye. Curr. Eye Res. 2019, 44, 1006–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Recchia, F.M.; Xu, L.; Penn, J.S.; Boone, B.; Dexheimer, P. Identification of Genes and Pathways Involved in Retinal Neovascularization by Microarray Analysis of Two Animal Models of Retinal Angiogenesis. Investig. Opthalmology Vis. Sci. 2010, 51, 1098–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, Y.-P.; Hallman, D.M.; Gonzalez, V.H.; Klein, B.E.K.; Klein, R.; Hayes, M.G.; Cox, N.J.; Bell, G.I.; Hanis, C.L. Identification of Diabetic Retinopathy Genes through a Genome-Wide Association Study among Mexican-Americans from Starr County, Texas. J. Ophthalmol. 2010, 2010, 861291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahram, D.F.; Cook, A.C.; Kecova, H.; Grozdanic, S.D.; Kuehn, M.H. Identification of genetic loci associated with primary angle-closure glaucoma in the basset hound. Mol. Vis. 2014, 20, 497–510. [Google Scholar]

- Kole, C.; Berdugo, N.; DA Silva, C.; Aït-Ali, N.; Millet-Puel, G.; Pagan, D.; Blond, F.; Poidevin, L.; Ripp, R.; Fontaine, V.; et al. Identification of an Alternative Splicing Product of the Otx2 Gene Expressed in the Neural Retina and Retinal Pigmented Epithelial Cells. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0150758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.B.; Xu, T.; Peng, S.; Singh, D.; Ghiassi-Nejad, M.; Adelman, R.A.; Rizzolo, L.J. Disease-associated mutations of claudin-19 disrupt retinal neurogenesis and visual function. Commun. Biol. 2019, 2, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudolf, R.; Bittins, C.M.; Gerdes, H.-H. The role of myosin V in exocytosis and synaptic plasticity. J. Neurochem. 2010, 116, 177–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burgoyne, T.; O’Connor, M.N.; Seabra, M.C.; Cutler, D.F.; Futter, C.E. Regulation of melanosome number, shape and movement in the zebrafish retinal pigment epithelium by OA1 and PMEL. J. Cell Sci. 2015, 128, 1400–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Chen, M.; Reid, D.M.; Forrester, J.V. LYVE-1–Positive Macrophages Are Present in Normal Murine Eyes. Investig. Opthalmology Vis. Sci. 2007, 48, 2162–2171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roddy, G.W.; Rosa, R.H., Jr.; Oh, J.Y.; Ylostalo, J.H.; Bartosh, Y.J., Jr.; Choi, H.; Lee, R.H.; Yasumura, D.; Ahern, K.; Nielsen, G.; et al. Stanniocalcin-1 rescued photoreceptor degeneration in two rat models of inherited retinal degeneration. Mol. Ther. 2012, 20, 788–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ubaidi, M.R.; Naash, M.I.; Conley, S.M. A Perspective on the Role of the Extracellular Matrix in Progressive Retinal De-generative Disorders. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2013, 54, 8119–8124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lillien, L.E.; Sendtner, M.; Raff, M.C. Extracellular matrix-associated molecules collaborate with ciliary neu- rotrophic factor to induce type-2 astrocyte development. J, Cell Biol. 1990, 111, 635–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaborowski, M.P.; Balaj, L.; Breakefield, X.O.; Lai, C.P. Extracellular Vesicles: Composition, Biological Relevance, and Methods of Study. Bioscience 2015, 65, 783–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andaloussi, S.; Mäger, I.; Breakefield, X.O.; Wood, M.J.A. Extracellular vesicles: Biology and emerging therapeutic opportunities. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2013, 12, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wooff, Y.; Cioanca, A.V.; Chu-Tan, J.A.; Aggio-Bruce, R.; Schumann, U.; Natoli, R. Small-Medium Extracellular Vesicles and Their miRNA Cargo in Retinal Health and De-generation: Mediators of Homeostasis, and Vehicles for Targeted Gene Therapy. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2020, 14, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, A.J.; Nakamura, M.; Wolpert, E.B.; Reiter, C.E.N.; Seigel, G.M.; Antonetti, D.A.; Gardner, T. Insulin Rescues Retinal Neurons from Apoptosis by a Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase/Akt-mediated Mechanism That Reduces the Activation of Caspase-3. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 32814–32821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, E.S.; Rendahl, K.G.; Zhou, S.; Ladner, M.; Coyne, M.; Srivastava, R.; Manning, W.C.; Flannery, J.G. Two Animal Models of Retinal Degeneration Are Rescued by Recombinant Adeno-associated Virus-Mediated Production of FGF-5 and FGF-18. Mol. Ther. 2001, 3, 507–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Wang, Z.; Zheng, Z.; Chen, Y.; Khor, S.; Shi, K.; He, Z.; Wang, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, H.; et al. Neuron and microglia/macrophage-derived FGF10 activate neuronal FGFR2/PI3K-Akt signaling and inhibit microglia/macrophages TLR4/NF-κB-dependent neuroinflammation to improve functional recovery after spinal cord injury. Cell Death Dis. 2017, 8, e3090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fudalej, E.; Justyniarska, M.; Kasarełło, K.; Dziedziak, J.; Szaflik, J.P.; Cudnoch-Jędrzejewska, A. Neuroprotective Factors of the Retina and Their Role in Promoting Survival of Retinal Ganglion Cells: A Review. Ophthalmic. Res. 2021, 64, 345–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Liu, H.; Lu, X.; Tombran-Tink, J.; Zhao, S. PEDF Attenuates Ocular Surface Damage in Diabetic Mice Model through Its Antioxidant Properties. Curr. Eye Res. 2020, 46, 302–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, B.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, R.; Zhang, K.; Yang, T.; Hu, C.; Gao, Y.; Lan, Q.; Liu, Y.; Yang, X.; et al. Pigment epithelium-derived factor (PEDF) plays anti-inflammatory roles in the pathogenesis of dry eye disease. Ocul. Surf. 2021, 20, 70–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Pinto, A.; Polato, F.; Subramanian, P.; de la Rocha-Muñoz, A.; Vitale, S.; de la Rosa, E.J.; Becerra, S.P. PEDF peptides promote photoreceptor survival in rd10 retina models. Exp. Eye Res. 2019, 184, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagan-Mercado, G.; Becerra, S.P. Signaling Mechanisms Involved in PEDF-Mediated Retinoprotection. Retin. Degener. Dis. 2019, 1185, 445–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikelle, L.; Naash, M.I.; Al-Ubaidi, M.R. Modulation of SOD3 Levels Is Detrimental to Retinal Homeostasis. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyaji, M.; Furuta, R.; Hosoya, O.; Sano, K.; Hara, N.; Kuwano, R.; Kang, J.; Tateno, M.; Tsutsui, K.M.; Tsutsui, K. Topoisomerase IIβ targets DNA crossovers formed between distant homologous sites to induce chromatin opening. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 18550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene Name | Description | Locus | Log2(Fold_Change) | p_Value | q_Value | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SERPINF1 | Serpin Family F Member 1 | chr10:62713440-62739444 | 2.722 | 5.00 × 10−5 | 0.012 | [27,28] |

| COL4A1 | Collagen Type IV Alpha 1 Chain | chr16:83045182-83157835 | 2.651 | 5.00 × 10−5 | 0.012 | [29] |

| CRYAB | Crystallin Alpha B | chr8:54107289-54111502 | 2.368 | 5.00 × 10−5 | 0.012 | [30] |

| COL4A2 | Collagen Type IV Alpha 2 Chain | chr16:82899293-83045155 | 2.293 | 5.00 × 10−5 | 0.012 | [31] |

| HSPG2 | Heparan Sulfate Proteoglycan 2 | chr5:156226988-156328912 | 2.089 | 5.00 × 10−5 | 0.012 | [32] |

| AQP1 | Aquaporin 1 | chr4:84098345-84110524 | 2.043 | 5.00 × 10−5 | 0.012 | [33] |

| ANXA1 | Annexin A1 | chr1:223478435-223494455 | 1.798 | 5.00 × 10−5 | 0.012 | [34] |

| Ecrg4 | ECRG4 augurin precursor | chr9:42930953-42950605 | 1.575 | 5.00 × 10−5 | 0.012 | [35] |

| WLS | Wnt Ligand Secretion Mediator | chr2:258014377-258128180 | 1.392 | 5.00 × 10−5 | 0.012 | [36] |

| SLC22A8 | Solute Carrier Family 22 Member 8 | chr1:211269365-211287596 | 1.388 | 5.00 × 10−5 | 0.012 | [37] |

| SOD3 | Superoxide dismutase 3 | chr14:63381446-63387180 | 1.328 | 5.00 × 10−5 | 0.012 | [38,39] |

| FBLN2 | Fibulin 2 | chr4:125380499-125441075 | 1.296 | 5.00 × 10−5 | 0.012 | [40] |

| OPTC | Opticin | chr13:46846755-46858100 | 1.292 | 5.00 × 10−5 | 0.012 | [41] |

| SLC13A4 | Solute Carrier Family 13 Member 4 | chr4:62679592-62724547 | 1.265 | 5.00 × 10−5 | 0.012 | [42] |

| FGFR2 | Fibroblast Growth Factor Receptor 2 | chr1:189482974-189589279 | 1.243 | 5.00 × 10−5 | 0.012 | [43] |

| FBLN1 | Fibulin 1 | chr7:123208153-123287289 | 1.194 | 5.00 × 10−5 | 0.012 | [44] |

| TYRP1 | Tyrosinase-Related Protein 1 | chr5:99518305-99537289 | 1.190 | 5.00 × 10−5 | 0.012 | [45] |

| OGN | Osteoglycin | chr17:20969065-21145330 | 1.160 | 5.00 × 10−5 | 0.012 | [46] |

| GJA1 | Gap Junction Protein Alpha 1 | chr20:35409814-35422259 | 1.117 | 5.00 × 10−5 | 0.012 | [47] |

| WFDC1 | WAP Four-Disulfide Core Domain 1 | chr19:49924309-49943113 | 1.116 | 5.00 × 10−5 | 0.012 | [48] |

| LTBP2 | Latent Transforming Growth Factor Beta Binding Protein 2 | chr6:108826438-108924895 | 1.112 | 5.00 × 10−5 | 0.012 | [49] |

| COL4A5 | Collagen Type IV Alpha 5 Chain | chrX:36918650-37130562 | 1.105 | 5.00 × 10−5 | 0.012 | [50] |

| DAPL1 | Death-Associated Protein Like 1 | chr3:41187966-41207910 | 1.070 | 5.00 × 10−5 | 0.012 | [51] |

| ENPP2 | Ectonucleotide Pyrophosphatase/Phosphodiesterase 2 | chr7:91295814-91377947 | 0.997 | 5.00 × 10−5 | 0.012 | [52] |

| SLC13A3 | Solute Carrier Family 13 Member 3 | chr3:156447899-156510620 | 0.914 | 5.00 × 10−5 | 0.012 | [53] |

| MXRA8 | Matrix Remodeling Associated 8 | chr5:172698112-172702607 | 0.899 | 5.00 × 10−5 | 0.012 | [54] |

| COL9A1 | Collagen Type IX Alpha 1 Chain | chr9:22907067-22990836 | 0.855 | 5.00 × 10−5 | 0.012 | [55] |

| COL8A1 | Collagen Type VIII Alpha 1 Chain | chr11:43604973-43737050 | 1.879 | 1.50 × 10−4 | 0.029 | [56] |

| MFRP | Membrane Frizzled-Related Protein | chr8:47084055-47089218 | 1.169 | 1.50 × 10−4 | 0.029 | [57] |

| COL5A1 | Collagen Type V Alpha 1 Chain | chr3:6825780-6973521 | 0.901 | 1.50 × 10−4 | 0.029 | [58] |

| FBN1 | Fibrillin 1 | chr3:112607811-112804951 | 0.895 | 1.50 × 10−4 | 0.029 | [59] |

| COL18A1 | Collagen alpha-1(XVIII) chain | chr20:11872458-11982466 | 0.834 | 1.50 × 10−4 | 0.029 | [60] |

| SLC6A13 | Solute Carrier Family 6 Member 13 | chr4:157736263-157771945 | 0.942 | 2.00 × 10−4 | 0.036 | [61] |

| ABI3BP | ABI Family Member 3 Binding Protein | chr11:44853363-45072422 | 1.122 | 2.50 × 10−4 | 0.041 | [62] |

| CPXM1 | Carboxypeptidase X, M14 Family Member 1 | chr3:118000979-118007777 | 1.102 | 2.50 × 10−4 | 0.041 | [63] |

| FMOD | Fibromodulin | chr13:46987713-46998331 | 0.887 | 2.50 × 10−4 | 0.041 | [64] |

| VCAN | Versican | chr2:19712628-19812592 | 0.868 | 4.00 × 10−4 | 0.061 | [44] |

| SERPINH1 | Serpin Family H Member 1 | chr1:156666873-156674336 | 0.765 | 4.00 × 10−4 | 0.061 | [65] |

| PCOLCE | Procollagen C-Endopeptidase Enhancer | chr12:19672504-19690374 | 1.398 | 4.50 × 10−4 | 0.068 | [66] |

| SLC26A4 | Solute Carrier Family 26 Member | chr6:49389211-49427000 | 0.835 | 5.50 × 10−4 | 0.078 | [67] |

| FSTL1 | Follistatin Like 1 | chr11:64680819-64735683 | 0.694 | 5.50 × 10−4 | 0.078 | [68] |

| OLFML2A | Olfactomedin Like 2A | chr3:18731164-18751940 | 0.713 | 6.50 × 10−4 | 0.089 | [69] |

| MRC2 | Mannose Receptor C Type 2 | chr10:94689060-94753073 | 0.831 | 9.00 × 10−4 | 0.117 | [70] |

| GSTM2 | Glutathione S-Transferase Mu 2 | chr2:203549021-203553380 | 1.207 | 9.50 × 10−4 | 0.120 | [71,72] |

| COL6A2 | Collagen Type VI Alpha 2 Chain | chr20:12436782-12464512 | 0.859 | 1.05 × 10−3 | 0.127 | [73] |

| COL9A2 | Collagen Type IX Alpha 2 Chain | chr5:141623364-141640224 | 0.770 | 1.15 × 10−3 | 0.137 | [74] |

| NID2 | nidogen-2 | chr15:4801182-4856895 | 0.769 | 1.40 × 10−3 | 0.163 | [75,76] |

| F5 | Coagulation Factor V | chr13:79934955-79997282 | 0.745 | 1.50 × 10−3 | 0.171 | [77] |

| SNED1 | Sushi, Nidogen, and EGF-Like Domains 1 | chr9:92509498-92568597 | 0.672 | 1.65 × 10−3 | 0.181 | [78] |

| COLEC12 | Collectin Subfamily Member 12 | chr18:996296-1188288 | 0.951 | 1.80 × 10−3 | 0.192 | [79] |

| COL1A2 | Collagen Type I Alpha 2 Chain | chr4:29393502-29429101 | 1.066 | 2.60 × 10−3 | 0.264 | [80] |

| SLC16A12 | Solute Carrier Family 16 Member 12 | chr1:238643039-238665699 | 0.962 | 2.85 × 10−3 | 0.281 | [81] |

| CLDN19 | Claudin 19 | chr5:139838013-139842711 | 0.896 | 5.80 × 10−3 | 0.480 | [82] |

| MYO5C | Myosin VC | chr8:80042255-80118773 | 0.921 | 5.85 × 10−3 | 0.481 | [83] |

| PMEL | Premelanosome Protein | chr7:2007881-2045336 | 1.294 | 1.40 × 10−2 | 0.941 | [84] |

| Gene Name | Description | Locus | Log2(Fold_Change) | p_Value | q_Value | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LYVE1 | Lymphatic Vessel Endothelial Hyaluronan Receptor 1 | chr1:168601459-168622234 | −1.001 | 1.58 × 10−2 | 0.999 | [85] |

| Category | Term | Description | LogP | InTerm_ InList | Genes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reactome Gene Sets | R-RNO- 1474244 | Extracellular matrix organization | −18.264 | 16/198 | Serpinh1, Pcolce, Ltbp2, Fbn1, Col1a2, Col18a1, Col5a1, Vcan, Fbln2, Col4a1, Nid2, Col8a1, Optc, Col6a2, Col9a2, Col4a5, Fmod, Olfml2a, Col9a1, Col4a2, Hspg2, Fbln1, Abi3bp, Fgfr2 |

| Category | Term | Description | LogP | InTerm_ InList | Genes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GO Biological Processes | GO:0030198 | extracellular matrix organization | −16.615 | 17/308 | Serpinh1, Fmod, Col1a2, Col18a1, Col5a1, Fbln2, Col4a1, Olfml2a, Col8a1, Optc, Col9a1, Col4a2, Hspg2, Fbln1, Col9a2, Col4a5, Abi3bp |

| GO Biological Processes | GO:0043062 | extracellular structure organization | −16.591 | 17/309 | Serpinh1, Fmod, Col1a2, Col18a1, Col5a1, Fbln2, Col4a1, Olfml2a, Col8a1, Optc, Col9a1, Col4a2, Hspg2, Fbln1, Col9a2, Col4a5, Abi3bp |

| GO Biological Processes | GO:0045229 | external encapsulating structure organization | −16.567 | 17/310 | Serpinh1, Fmod, Col1a2, Col18a1, Col5a1, Fbln2, Col4a1, Olfml2a, Col8a1, Optc, Col9a1, Col4a2, Hspg2, Fbln1, Col9a2, Col4a5, Abi3bp |

| Category | Term | Description | LogP | InTerm_InList | Genes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KEGG Pathway | ko04512, rno04512 | ECM-receptor interaction | −9.901 | 8/81 | Col1a2, Col4a1, Col9a1, Col4a2, Hspg2, Col6a2, Col9a2, Col4a5 |

| KEGG Pathway | ko04151, rno04151 | PI3K–Akt signaling pathway | −5.166 | 8/329 | Fgfr2, Col1a2, Col4a1, Col9a1, Col4a2, Col6a2, Col9a2, Col4a5 |

| Category | Term | Count | % | p Value | Genes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GOTERM_ CC_DIRECT | GO:0070062~ extracellular exosome | 31 | 56.3 | 8.19 × 10−13 | COLEC12, COL18A1, SNED1, LTBP2, FBLN1, FBLN2, FSTL1, NID2, AQP1, GJA1, SERPINH1, SLC13A3, GSTM2, ANXA1, SERPINF1, SLC6A13, PCOLCE, SOD3, HSPG2, COL1A2, COL4A2, COL5A1, COL6A2, OGN, MYO5C, MXRA8, COL8A1, SLC26A4, SLC22A8, CRYAB, FBN1 |

| GOTERM_ CC_DIRECT | GO:0005615~ extracellular space | 22 | 40.0 | 2.30 × 10−11 | COL18A1, ANXA1, SERPINF1, RGD1305645, WFDC1, PCOLCE, LTBP2, FBLN1, SOD3, FSTL1, HSPG2, F5, VCAN, COL1A2, ABI3BP, COL6A2, OGN, SERPINH1, ENPP2, CPXM1, FMOD, FBN1 |

| GOTERM_ CC_DIRECT | GO:0031012~ extracellular matrix | 21 | 38.1 | 3.45 × 10−24 | COL18A1, SERPINF1, PCOLCE, LTBP2, FBLN1, SOD3, NID2, HSPG2, FBLN2, VCAN, COL1A2, COL4A2, COL5A1, COL4A1, ABI3BP, COL6A2, OGN, COL8A1, FMOD, FGFR2, FBN1 |

| Category | Term | Count | % | p Value | Genes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KEGG_PATHWAY | rno04151:PI3K–Akt signaling pathway | 7 | 12.7 | 2.76 × 10−4 | COL1A2, COL4A2, COL5A1, COL4A1, COL6A2, COL4A5, FGFR2 |

| KEGG_PATHWAY | rno04512:ECM- receptor interaction | 6 | 10.9 | 4.03 × 10−6 | COL1A2, COL4A2, COL5A1, COL4A1, COL6A2, COL4A5 |

| KEGG_PATHWAY | rno04510:Focal adhesion | 6 | 10.9 | 2.52 × 10−4 | COL1A2, COL4A2, COL5A1, COL4A1, COL6A2, COL4A5 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, S.; Miyaji, M.; Hosoya, O.; Matsuo, T. Effect of NK-5962 on Gene Expression Profiling of Retina in a Rat Model of Retinitis Pigmentosa. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 13276. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms222413276

Liu S, Miyaji M, Hosoya O, Matsuo T. Effect of NK-5962 on Gene Expression Profiling of Retina in a Rat Model of Retinitis Pigmentosa. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2021; 22(24):13276. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms222413276

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Shihui, Mary Miyaji, Osamu Hosoya, and Toshihiko Matsuo. 2021. "Effect of NK-5962 on Gene Expression Profiling of Retina in a Rat Model of Retinitis Pigmentosa" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 22, no. 24: 13276. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms222413276

APA StyleLiu, S., Miyaji, M., Hosoya, O., & Matsuo, T. (2021). Effect of NK-5962 on Gene Expression Profiling of Retina in a Rat Model of Retinitis Pigmentosa. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 22(24), 13276. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms222413276