Molecular Mechanisms of Antiproliferative and Apoptosis Activity by 1,5-Bis(4-Hydroxy-3-Methoxyphenyl)1,4-Pentadiene-3-one (MS13) on Human Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Cells

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

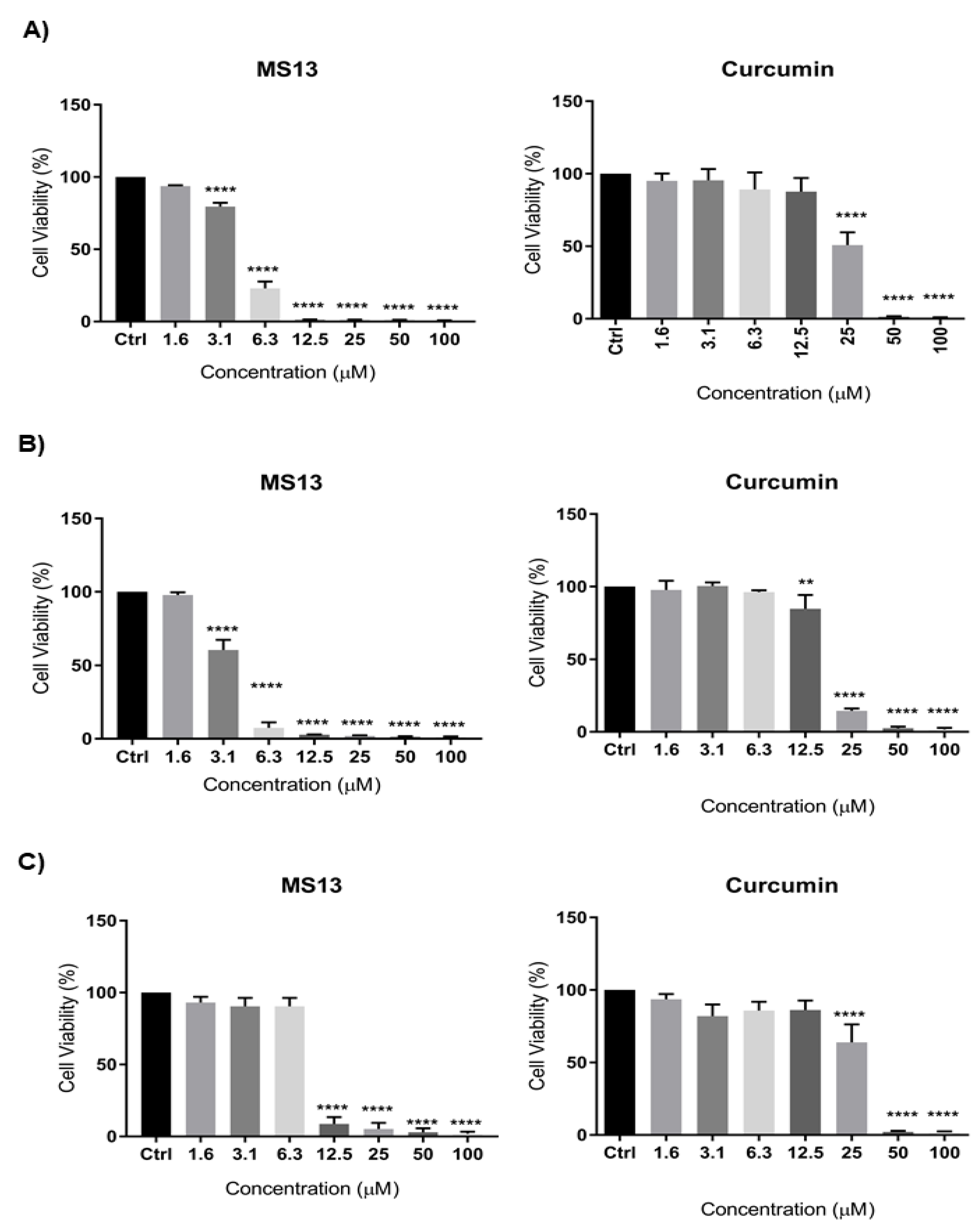

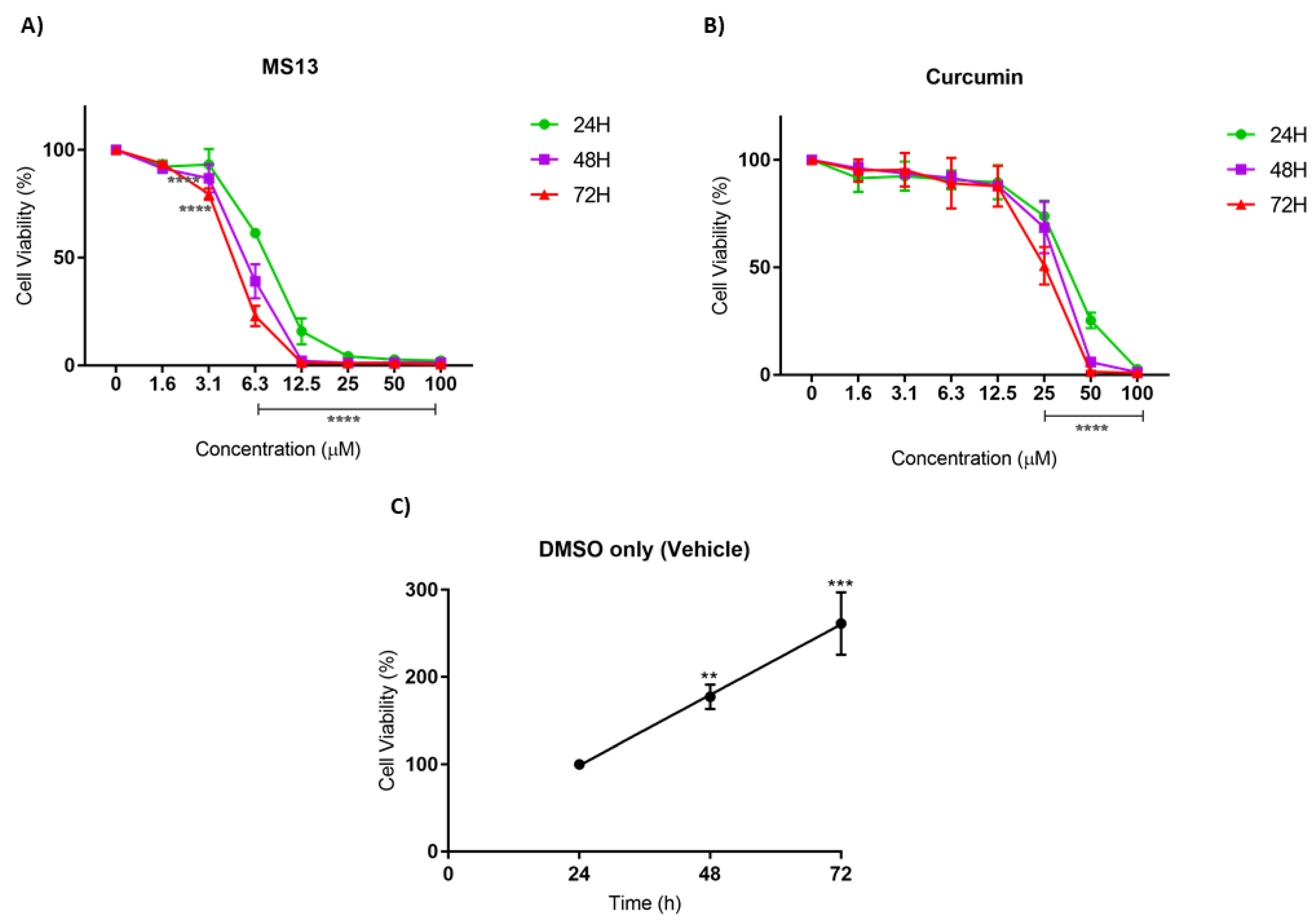

2.1. Cytotoxic Effects of MS13 on NCI-H520 and NCI-H23 Cell Lines

2.2. Antiproliferative Effect of MS13 on NCI-H520 and NCI-H23 Cell Lines

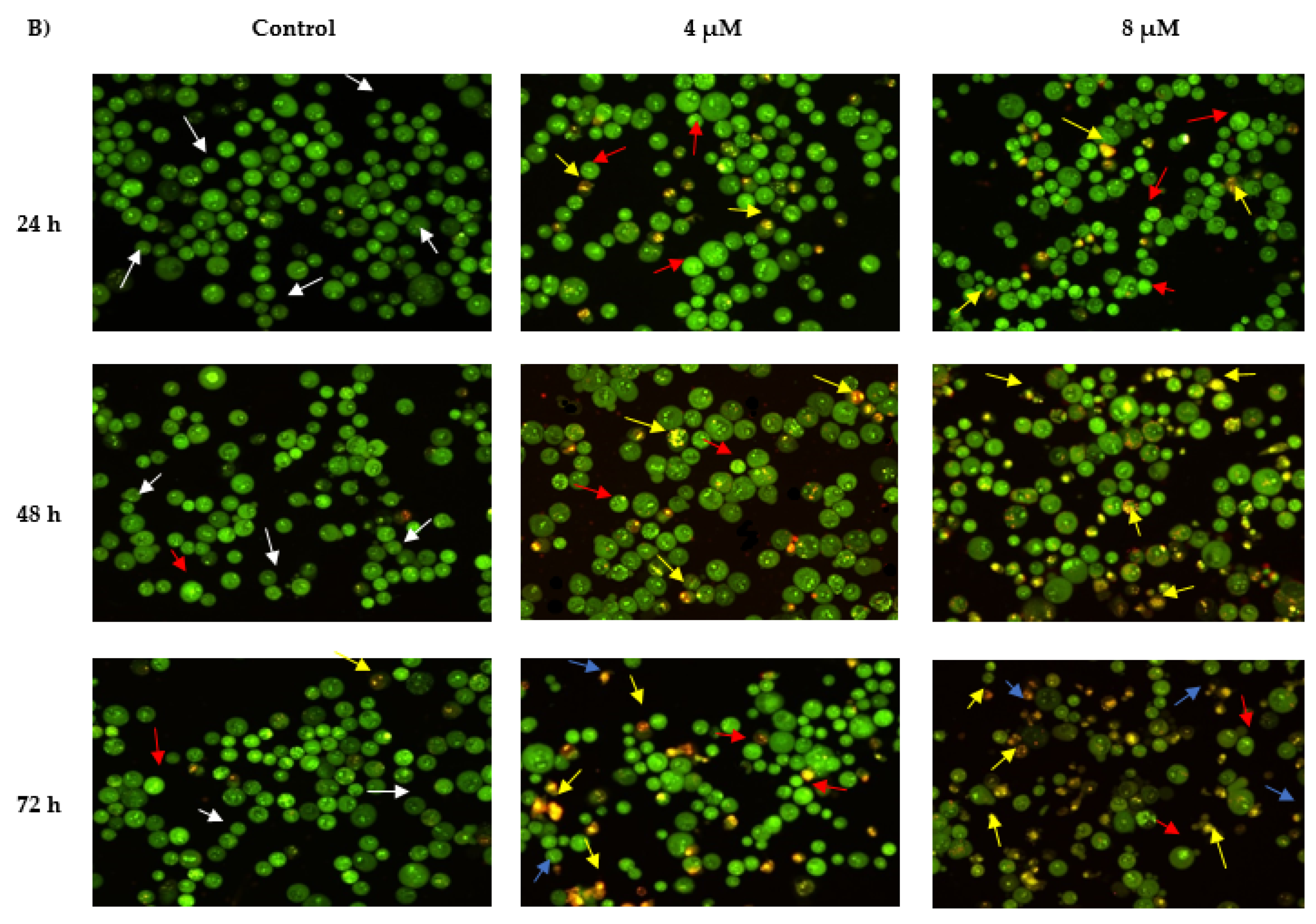

2.3. Morphological Observation of Apoptotic Cells by Acridine Orange

2.3.1. Propidium Iodide (AO-PI) Double Staining

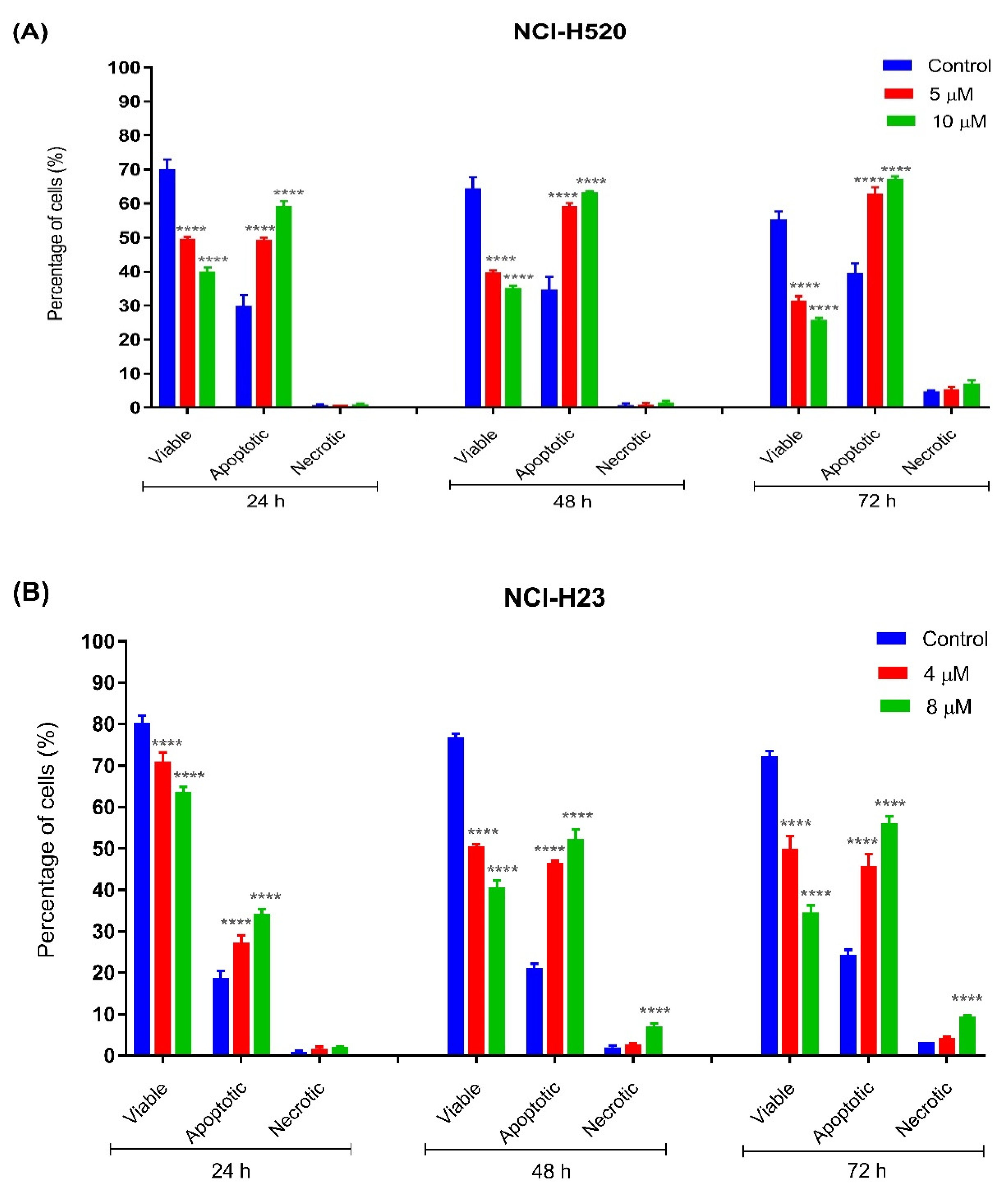

2.3.2. Quantification of Apoptotic and Necrotic Cells

2.3.3. Quantification of Relative Caspase-3 Activity

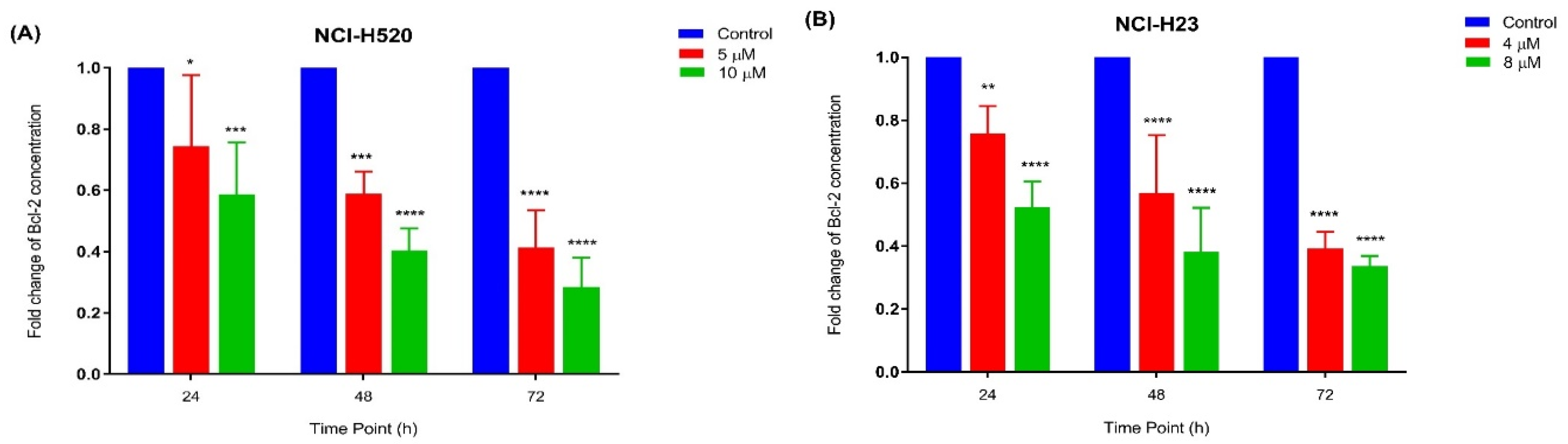

2.3.4. Quantification of Bcl-2 Protein Concentration

2.4. Analysis of Differentially Expressed Genes (DEGs) in MS13-Treated Lung Cancer Cells Associated with PI3K-AKT, Cell Cycle-Apoptosis, and MAPK Pathways

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cell Culture and Maintenance

4.2. Preparation of Curcumin Analogue (MS13) and Curcumin

4.3. Cell Viability and Antiproliferative Assays

4.4. Induction of Apoptosis by MS13

4.4.1. Morphological Evaluation of Apoptotic Cells by Acridine Orange–Propidium Iodide (AO-PI) Double Staining

- viable cells exhibit uniform green nuclei with intact structure

- early apoptotic cells exhibit bright-green to yellow nuclei. In addition, characteristics of membrane integrity loss and chromatin condensation

- late apoptotic cells exhibit yellow-orange to bright red nuclei as well as condensed or fragmented chromatin,

- necrotic cells exhibit bright orange or red uniform nuclei.

4.4.2. Caspase-3 Activity

4.4.3. Bcl-2 Cellular Protein Concentration

4.5. Gene Expression Analysis

4.5.1. Total mRNA Extraction

4.5.2. Nanostring nCounter Gene Expression Analysis

4.5.3. Sample Loading Protocol for nCounter SPRINTTM Profiler

4.5.4. Data Collection and Data Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travis, W.D. Pathology of lung cancer. Clin. Chest Med. 2011, 32, 669–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minna, J.D.; Roth, J.A.; Gazdar, A.F. Focus on lung cancer. Cancer Cell 2002, 1, 49–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, K.D.; Siegel, R.L.; Lin, C.C.; Mariotto, A.B.; Kramer, J.L.; Rowland, J.H.; Stein, K.D.; Alteri, R.; Jemal, A. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2016, 66, 271–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arriagada, R.; Dunant, A.; Pignon, J.-P.; Bergman, B.; Chabowski, M.; Grunenwald, D.; Kozlowski, M.; Le Péchoux, C.; Pirker, R.; Pinel, M.-I.S.; et al. Long-Term Results of the International Adjuvant Lung Cancer Trial Evaluating Adjuvant Cisplatin-Based Chemotherapy in Resected Lung Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009, 28, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altaf, M.M.; Ahmad Khan, M.S.; Ahmad, I. Chapter 2—Diversity of Bioactive Compounds and Their Therapeutic Potential. In New Look to Phytomedicine; Ahmad Khan, M.S., Ahmad, I., Chattopadhyay, D., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019; pp. 15–34. [Google Scholar]

- Panahi, Y.; Hosseini, M.S.; Khalili, N.; Naimi, E.; Simental-Mendía, L.E.; Majeed, M.; Sahebkar, A. Effects of curcumin on serum cytokine concentrations in subjects with metabolic syndrome: A post-hoc analysis of a randomized controlled trial. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2016, 82, 578–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahebkar, A.; Serban, M.-C.; Ursoniu, S.; Banach, M. Effect of curcuminoids on oxidative stress: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Funct. Foods 2015, 18, 898–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghadamtousi, S.Z.; Kadir, H.A.; Hassandarvish, P.; Tajik, H.; Abubakar, S.; Zandi, K. A Review on Antibacterial, Antiviral, and Antifungal Activity of Curcumin. BioMed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 186864. [Google Scholar]

- Vallianou, N.G.; Evangelopoulos, A.; Schizas, N.; Kazazis, C. Potential anticancer properties and mechanisms of action of curcumin. Anticancer. Res. 2015, 35, 645–651. [Google Scholar]

- Mehta, H.J.; Patel, V.; Sadikot, R.T. Curcumin and lung cancer—A review. Target. Oncol. 2014, 9, 295–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan Mohd Tajuddin, W.N.B.; Lajis, N.H.; Abas, F.; Othman, I.; Naidu, R. Mechanistic understanding of curcumin’s therapeutic effects in lung cancer. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, P.; Kunnumakkara, A.B.; Newman, R.A.; Aggarwal, B.B. Bioavailability of curcumin: Problems and promises. Mol. Pharm. 2007, 4, 807–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulraj, F.; Abas, F.; Lajis, N.H.; Othman, I.; Naidu, R. Molecular Pathways Modulated by Curcumin Analogue, Diarylpentanoids in Cancer. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cen, L.; Hutzen, B.; Ball, S.; DeAngelis, S.; Chen, C.-L.; Fuchs, J.R.; Li, C.; Li, P.-K.; Lin, J. New structural analogues of curcumin exhibit potent growth suppressive activity in human colorectal carcinoma cells. BMC Cancer 2009, 9, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvendiran, K.; Ahmed, S.; Dayton, A.; Kuppusamy, M.L.; Tazi, M.; Bratasz, A.; Tong, L.; Rivera, B.K.; Kálai, T.; Hideg, K. Safe and targeted anticancer efficacy of a novel class of antioxidant-conjugated difluorodiarylidenyl piperidones: Differential cytotoxicity in healthy and cancer cells. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2010, 48, 1228–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.; Sidell, N.; Mancini, A.; Huang, R.-P.; Shenming, W.; Horowitz, I.R.; Liotta, D.C.; Taylor, R.N.; Wieser, F. Multiple Anticancer Activities of EF24, a Novel Curcumin Analog, on Human Ovarian Carcinoma Cells. Reprod. Sci. 2010, 17, 931–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, G.; Shao, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, C.; Chu, Y.; Xiao, J.; Zhao, Y.; Li, X.; Yang, S. Exploration and synthesis of curcumin analogues with improved structural stability both in vitro and in vivo as cytotoxic agents. Bioorganic Med. Chem. 2009, 17, 2623–2631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Citalingam, K.; Abas, F.; Lajis, N.H.; Othman, I.; Naidu, R. Anti-proliferative effect and induction of apoptosis in androgen-independent human prostate cancer cells by 1, 5-bis (2-hydroxyphenyl)-1, 4-pentadiene-3-one. Molecules 2015, 20, 3406–3430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paulraj, F.; Abas, F.; Lajis, N.H.; Othman, I.; Hassan, S.S.; Naidu, R. The curcumin analogue 1, 5-bis (2-hydroxyphenyl)-1, 4-pentadiene-3-one induces apoptosis and downregulates E6 and E7 oncogene expression in HPV16 and HPV18-infected cervical cancer cells. Molecules 2015, 20, 11830–11860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, N.I.; Othman, I.; Abas, F.; Lajis, N.H.; Naidu, R. The Curcumin Analogue, MS13 (1, 5-Bis (4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-1, 4-pentadiene-3-one), Inhibits Cell Proliferation and Induces Apoptosis in Primary and Metastatic Human Colon Cancer Cells. Molecules 2020, 25, 3798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.Q.; Rajadurai, P.; Abas, F.; Othman, I.; Naidu, R. Proteomic Analysis on Anti-Proliferative and Apoptosis Effects of Curcumin Analog, 1, 5-bis (4-Hydroxy-3-Methyoxyphenyl)-1, 4-Pentadiene-3-One-Treated Human Glioblastoma and Neuroblastoma Cells. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, K.-B.; Bustamam, A.; Sukari, M.A.; Abdelwahab, S.I.; Mohan, S.; Buckle, M.J.C.; Kamalidehghan, B.; Nadzri, N.M.; Anasamy, T.; Hadi, A.H.A. Induction of selective cytotoxicity and apoptosis in human T4-lymphoblastoid cell line (CEMss) by boesenbergin a isolated from boesenbergia rotunda rhizomes involves mitochondrial pathway, activation of caspase 3 and G2/M phase cell cycle arrest. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2013, 13, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmer, S.; Kahl, P.; Buhl, T.M.; Steiner, S.; Wardelmann, E.; Merkelbach-Bruse, S.; Buettner, R.; Heukamp, L.C. Epidermal growth factor receptor mutations in non-small cell lung cancer influence downstream Akt, MAPK and Stat3 signaling. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2009, 135, 723–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedman, L.; Lin, L.; Ball, S.; Bekaii-Saab, T.; Fuchs, J.; Li, P.-K.; Li, C.; Lin, J. Curcumin analogues exhibit enhanced growth suppressive activity in human pancreatic cancer cells. Anti-Cancer Drugs 2009, 20, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, T.; Maruyama, T.; Miura, M.; Inoue, M.; Fukuda, K.; Shimazu, K.; Taguchi, D.; Kanda, H.; Oshima, M.; Iwabuchi, Y. Dietary intake of pyrolyzed deketene curcumin inhibits gastric carcinogenesis. J. Funct. Foods 2018, 50, 192–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvendiran, K.; Tong, L.; Bratasz, A.; Kuppusamy, M.L.; Ahmed, S.; Ravi, Y.; Trigg, N.J.; Rivera, B.K.; Kálai, T.; Hideg, K. Anticancer efficacy of a difluorodiarylidenyl piperidone (HO-3867) in human ovarian cancer cells and tumor xenografts. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2010, 9, 1169–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramaniam, D.; May, R.; Sureban, S.M.; Lee, K.B.; George, R.; Kuppusamy, P.; Ramanujam, R.P.; Hideg, K.; Dieckgraefe, B.K.; Houchen, C.W. Diphenyl difluoroketone: A curcumin derivative with potent in vivo anticancer activity. Cancer Res. 2008, 68, 1962–1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutzen, B.; Friedman, L.; Sobo, M.; Lin, L.; Cen, L.; De Angelis, S.; Yamakoshi, H.; Shibata, H.; Iwabuchi, Y.; Lin, J. Curcumin analogue GO-Y030 inhibits STAT3 activity and cell growth in breast and pancreatic carcinomas. Int. J. Oncol. 2009, 35, 867–872. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lin, L.; Liu, Y.; Li, H.; Li, P.; Fuchs, J.; Shibata, H.; Iwabuchi, Y.; Lin, J. Targeting colon cancer stem cells using a new curcumin analogue, GO-Y030. Br. J. Cancer 2011, 105, 212–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Shi, Q.; Nyarko, A.K.; Bastow, K.F.; Wu, C.-C.; Su, C.-Y.; Shih, C.C.-Y.; Lee, K.-H. Antitumor agents. 250. Design and synthesis of new curcumin analogues as potential anti-prostate cancer agents. J. Med. Chem. 2006, 49, 3963–3972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Goot, H. The chemistry and qualitative structure-activity relationships of curcumin. In Recent Developments in Curcumin Pharmacochemistry; Aditya Media: Mumbai, India, 1997; pp. 13–26. [Google Scholar]

- Danial, N.N.; Korsmeyer, S.J. Cell death: Critical control points. Cell 2004, 116, 205–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, R.S. Apoptosis in cancer: From pathogenesis to treatment. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2011, 30, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, A.G.; Jänicke, R.U. Emerging roles of caspase-3 in apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 1999, 6, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jänicke, R.U.; Sprengart, M.L.; Wati, M.R.; Porter, A.G. Caspase-3 is required for DNA fragmentation and morphological changes associated with apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 9357–9360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, W.; Xiao, J.; Zhang, H.; Chen, Q.; Wang, Z.; Shi, H.; Gong, L.; Chen, J.; Liu, Y.; Cao, R. B19, a novel monocarbonyl analogue of curcumin, induces human ovarian cancer cell apoptosis via activation of endoplasmic reticulum stress and the autophagy signaling pathway. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2013, 9, 766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cory, S.; Adams, J.M. The Bcl2 family: Regulators of the cellular life-or-death switch. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2002, 2, 647–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.E.; Ha, T.K.; Yoon, J.H.; Lee, J.S. Myricetin induces cell death of human colon cancer cells via BAX/BCL2-dependent pathway. Anticancer. Res. 2014, 34, 701–706. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Faião-Flores, F.; Suarez, J.A.Q.; Soto-Cerrato, V.; Espona-Fiedler, M.; Pérez-Tomás, R.; Maria, D.A. Bcl-2 family proteins and cytoskeleton changes involved in DM-1 cytotoxic effect on melanoma cells. Tumor Biol. 2013, 34, 1235–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarris, E.G.; Saif, M.W.; Syrigos, K.N. The Biological Role of PI3K Pathway in Lung Cancer. Pharmaceuticals 2012, 5, 1236–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadimitrakopoulou, V. Development of PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway inhibitors and their application in personalized therapy for non–small-cell lung cancer. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2012, 7, 1315–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsurutani, J.; Fukuoka, J.; Tsurutani, H.; Shih, J.H.; Hewitt, S.M.; Travis, W.D.; Jen, J.; Dennis, P.A. Evaluation of two phosphorylation sites improves the prognostic significance of Akt activation in non–small-cell lung cancer tumors. J. Clin. Oncol. 2006, 24, 306–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, J.-M.; He, Q.-Y.; Guo, R.-X.; Chang, X.-J. Phosphorylated Akt overexpression and loss of PTEN expression in non-small cell lung cancer confers poor prognosis. Lung Cancer 2006, 51, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Umemura, S.; Mimaki, S.; Makinoshima, H.; Tada, S.; Ishii, G.; Ohmatsu, H.; Niho, S.; Yoh, K.; Matsumoto, S.; Takahashi, A. Therapeutic priority of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway in small cell lung cancers as revealed by a comprehensive genomic analysis. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2014, 9, 1324–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sebolt-Leopold, J.S.; Herrera, R. Targeting the mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade to treat cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2004, 4, 937–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labib, K.; Tercero, J.A.; Diffley, J.F.X. Uninterrupted MCM2-7 Function Required for DNA Replication Fork Progression. Science 2000, 288, 1643–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, B.; Yu, G.; Tseng, G.C.; Cieply, K.; Gavel, T.; Nelson, J.; Michalopoulos, G.; Yu, Y.; Luo, J. MCM7 amplification and overexpression are associated with prostate cancer progression. Oncogene 2006, 25, 1090–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.-Y.; Li, D.; Zhang, Y.; Guan, B.-X.; Gao, P.; Zhou, X.-C.; Zhou, C.-J. The expression of MCM7 is a useful biomarker in the early diagnostic of gastric cancer. Pathol. Oncol. Res. 2018, 24, 367–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.-Z.; Jiang, Y.-Y.; Hao, J.-J.; Lu, S.-S.; Zhang, T.-T.; Shang, L.; Cao, J.; Song, X.; Wang, B.-S.; Cai, Y. Prognostic significance of MCM7 expression in the bronchial brushings of patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Lung Cancer 2012, 77, 176–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujioka, S.; Shomori, K.; Nishihara, K.; Yamaga, K.; Nosaka, K.; Araki, K.; Haruki, T.; Taniguchi, Y.; Nakamura, H.; Ito, H. Expression of minichromosome maintenance 7 (MCM7) in small lung adenocarcinomas (pT1): Prognostic implication. Lung Cancer 2009, 65, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreenivasan, S.; Thirumalai, K.; Krishnakumar, S. Expression Profile of Genes Regulated by Curcumin in Y79 Retinoblastoma Cells. Nutr. Cancer 2012, 64, 607–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drechsel, D.; Hyman, A.A.; Cobb, M.H.; Kirschner, M.W. Modulation of the dynamic instability of tubulin assembly by the microtubule-associated protein tau. Mol. Biol. Cell 1992, 3, 1141–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Liu, Y.; Guo, W.; Zhu, X.; Ahuja, N.; Fu, T. MAPT promoter CpG island hypermethylation is associated with poor prognosis in patients with stage II colorectal cancer. Cancer Manag. Res. 2019, 11, 7337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, D.-H.; Lee, H.J.; Ahn, J.-H.; Yoon, D.H.; Kim, S.-B.; Gong, G.; Son, B.H.; Ahn, S.H.; Jung, K.H. Tau and PTEN status as predictive markers for response to trastuzumab and paclitaxel in patients with HER2-positive breast cancer. Tumor Biol. 2015, 36, 5865–5871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mimori, K.; Sadanaga, N.; Yoshikawa, Y.; Ishikawa, K.; Hashimoto, M.; Tanaka, F.; Sasaki, A.; Inoue, H.; Sugimachi, K.; Mori, M. Reduced tau expression in gastric cancer can identify candidates for successful Paclitaxel treatment. Br. J. Cancer 2006, 94, 1894–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sekino, Y.; Han, X.; Babasaki, T.; Goto, K.; Inoue, S.; Hayashi, T.; Teishima, J.; Shiota, M.; Takeshima, Y.; Yasui, W. Microtubule-Associated Protein Tau (MAPT) Promotes Bicalutamide Resistance and Is Associated with Survival in Prostate Cancer; Urologic Oncology: Seminars and Original Investigations; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; p. 795. [Google Scholar]

- Massague, J. The Transforming Growth Factor-beta Family. Annu. Rev. Cell Biol. 1990, 6, 597–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, H.; Liang, Y.; Kang, L.; Xiao, Y.; Yu, T.; Wan, R. miR-454-3p inhibits non-small cell lung cancer cell proliferation and metastasis by targeting TGFB2. Oncol. Rep. 2021, 45, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dumont, N.; Arteaga, C.L. Transforming growth factor-beta and breast cancer: Tumor promoting effects of transforming growth factor-β. Breast Cancer Res. 2000, 2, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, R.; Ji, Z.; Li, X.; Qin, J.; Cui, G.; Chen, J.; Zhai, Q.; Zhao, C.; Zhang, W.; Yu, Z. Tumor suppressive microRNA-200a inhibits renal cell carcinoma development by directly targeting TGFB2. Tumor Biol. 2015, 36, 6691–6700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, J.C. Thrombospondin-1. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 1997, 29, 861–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, G.J.; Hayden, K.E.; McDowell, G.; Lang, H.; Kirwan, C.C.; Tetlow, L.; Kumar, S.; Bundred, N.J. Angiogenic characteristics of circulating and tumoural thrombospondin-1 in breast cancer. Int. J. Oncol. 2007, 31, 1127–1132. [Google Scholar]

- Albo, D.; Rothman, V.L.; Roberts, D.D.; Tuszynski, G.P. Tumour cell thrombospondin-1 regulates tumour cell adhesion and invasion through the urokinase plasminogen activator receptor. Br. J. Cancer 2000, 83, 298–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Dong, M.; Li, L.; Fan, Y.; Pathre, P.; Dong, J.; Lou, D.; Wells, J.M.; Olivares-Villagómez, D.; Van Kaer, L.; et al. Endonuclease G is required for early embryogenesis and normal apoptosis in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 15782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basnakian, A.G.; Apostolov, E.O.; Yin, X.; Abiri, S.O.; Stewart, A.G.; Singh, A.B.; Shah, S.V. Endonuclease G promotes cell death of non-invasive human breast cancer cells. Exp. Cell Res. 2006, 312, 4139–4149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Tryndyak, V.; Apostolov, E.O.; Yin, X.; Shah, S.V.; Pogribny, I.P.; Basnakian, A.G. Sensitivity of human prostate cancer cells to chemotherapeutic drugs depends on EndoG expression regulated by promoter methylation. Cancer Lett. 2008, 270, 132–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Dutto, I.; Tillhon, M.; Cazzalini, O.; Stivala, L.A.; Prosperi, E. Biology of the cell cycle inhibitor p21CDKN1A: Molecular mechanisms and relevance in chemical toxicology. Arch. Toxicol. 2015, 89, 155–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitsuuchi, Y.; Johnson, S.W.; Selvakumaran, M.; Williams, S.J.; Hamilton, T.C.; Testa, J.R. The Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase/AKT Signal Transduction Pathway Plays a Critical Role in the Expression of p21WAF1/CIP1/SDI1 Induced by Cisplatin and Paclitaxel. Cancer Res. 2000, 60, 5390. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Abbas, T.; Dutta, A. p21 in cancer: Intricate networks and multiple activities. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2009, 9, 400–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löhr, K.; Möritz, C.; Contente, A.; Dobbelstein, M. p21/CDKN1A mediates negative regulation of transcription by p53. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 32507–32516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukazawa, T.; Guo, M.; Ishida, N.; Yamatsuji, T.; Takaoka, M.; Yokota, E.; Haisa, M.; Miyake, N.; Ikeda, T.; Okui, T. SOX2 suppresses CDKN1A to sustain growth of lung squamous cell carcinoma. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 20113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Hu, Y.; Hu, W.; Xie, X.; Ela Bella, A.; Fu, J.; Rao, D. Expression and prognostic relevance of p21WAF1 in stage III esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Dis. Esophagus 2012, 25, 67–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.-Y.; Tan, Q.-X.; Zhu, X.; Qin, Q.-H.; Zhu, F.-B.; Mo, Q.-G.; Yang, W.-P. Expression of CDKN1A/p21 and TGFBR2 in breast cancer and their prognostic significance. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2015, 8, 14619–14629. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kuang, Y.-F.; Chen, Y.-H. Induction of apoptosis in a non-small cell human lung cancer cell line by isothiocyanates is associated with P53 and P21. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2004, 42, 1711–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Ho, W.S. Combination of liquiritin, isoliquiritin and isoliquirigenin induce apoptotic cell death through upregulating p53 and p21 in the A549 non-small cell lung cancer cells. Oncol. Rep. 2014, 31, 298–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, Y.; Shen, Z.; Gu, W.; Wu, M. Inhibition of hepatocellular carcinoma tumorigenesis by curcumin may be associated with CDKN1A and CTGF. Gene 2018, 651, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamura, R.E.; de Vasconcellos, J.F.; Sarkar, D.; Libermann, T.A.; Fisher, P.B.; Zerbini, L.F. GADD45 Proteins: Central Players in Tumorigenesis. Curr. Mol. Med. 2012, 12, 634–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, J.; Srivastava, G.; Hsieh, W.-S.; Gao, Z.; Murray, P.; Liao, S.-K.; Ambinder, R.; Tao, Q. The Stress-Responsive Gene GADD45G Is a Functional Tumor Suppressor, with Its Response to Environmental Stresses Frequently Disrupted Epigenetically in Multiple Tumors. Clin. Cancer Res. 2005, 11, 6442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Li, T.; Shao, Y.; Zhang, C.; Wu, Q.; Yang, H.; Zhang, J.; Guan, M.; Yu, B.; Wan, J. Semi-quantitative detection of GADD45-gamma methylation levels in gastric, colorectal and pancreatic cancers using methylation-sensitive high-resolution melting analysis. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2010, 136, 1267–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, W.; Zhu, T.; Dong, Z.; Cui, L.; Zhang, M.; Kuang, G. Decreased expression and aberrant methylation of Gadd45G is associated with tumor progression and poor prognosis in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Clin. Exp. Metastasis 2012, 30, 977–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.; Yuan, W.; He, J.; Wang, J.; Yu, L.; Jin, X.; Hu, Y.; Liao, M.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, Y. Overexpression of EphA2, MMP-9, and MVD-CD34 in hepatocellular carcinoma: Implications for tumor progression and prognosis. Hepatol. Res. 2009, 39, 1169–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, W.; Chen, Z.; Chen, Z.; Wu, S.; Guo, J.; Ge, J.; Yang, P.; Huang, J. Silencing of EphA2 inhibits invasion of human gastric cancer SGC-7901 cells in vitro and in vivo. Neoplasma 2012, 59, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.-X.; He, Y.-J.; Zhao, S.-Z.; Wu, J.-G.; Wang, J.-T.; Zhu, L.-M.; Lin, T.-T.; Sun, B.-C.; Li, X.-R. Inhibition of tumor growth and vasculogenic mimicry by curcumin through down-regulation of the EphA2/PI3K/MMP pathway in a murine choroidal melanoma model. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2011, 11, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Layseca, P.; Streuli, C.H. Signalling pathways linking integrins with cell cycle progression. Matrix Biol. 2014, 34, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, R.L.; O’Connor, K.L. Clinical significance of the integrin α6β4 in human malignancies. Lab. Investig. 2015, 95, 976–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boelens, M.C.; van den Berg, A.; Vogelzang, I.; Wesseling, J.; Postma, D.S.; Timens, W.; Groen, H.J.M. Differential expression and distribution of epithelial adhesion molecules in non-small cell lung cancer and normal bronchus. J. Clin. Pathol. 2007, 60, 608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, J.; Bachelder, R.E.; Lipscomb, E.A.; Shaw, L.M.; Mercurio, A.M. Integrin (α6β4) regulation of eIF-4E activity and VEGF translation: A survival mechanism for carcinoma cells. J. Cell Biol. 2002, 158, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, H.; Dydensborg, A.B.; Herring, F.E.; Basora, N.; Gagné, D.; Vachon, P.H.; Beaulieu, J.-F. Upregulation of a functional form of the β4 integrin subunit in colorectal cancers correlates with c-Myc expression. Oncogene 2005, 24, 6820–6829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolopoulos, S.N.; Blaikie, P.; Yoshioka, T.; Guo, W.; Giancotti, F.G. Integrin β4 signaling promotes tumor angiogenesis. Cancer Cell 2004, 6, 471–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khoshnoodi, J.; Pedchenko, V.; Hudson, B.G. Mammalian collagen IV. Microsc. Res. Tech. 2008, 71, 357–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burnier, J.V.; Wang, N.; Michel, R.P.; Hassanain, M.; Li, S.; Lu, Y.; Metrakos, P.; Antecka, E.; Burnier, M.N.; Ponton, A.; et al. Type IV collagen-initiated signals provide survival and growth cues required for liver metastasis. Oncogene 2011, 30, 3766–3783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Q.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, Q.; Yue, J.; Liu, C.; Zhao, X.; Qiao, Y.; Ji, H.; Chen, J.; Ge, G. Minor Type IV Collagen α5 Chain Promotes Cancer Progression through Discoidin Domain Receptor-1. PLoS Genet. 2015, 11, e1005249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salomonsson, A.; Jönsson, M.; Isaksson, S.; Karlsson, A.; Jönsson, P.; Gaber, A.; Bendahl, P.-O.; Johansson, L.; Brunnström, H.; Jirström, K.; et al. Histological specificity of alterations and expression of KIT and KITLG in non-small cell lung carcinoma. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2013, 52, 1088–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vliagoftis, H.; Worobec, A.S.; Metcalfe, D.D. The protooncogene c-kit and c-kit ligand in human disease. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 1997, 100, 435–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasagakis, K.; Krüger-Krasagakis, S.; Eberle, J.; Tsatsakis, A.; Tosca, A.D.; Stathopoulos, E.N. Co-Expression of KIT Receptor and Its Ligand Stem Cell Factor in Merkel Cell Carcinoma. Dermatology 2009, 218, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reichardt, L.F. Neurotrophin-regulated signalling pathways. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2006, 361, 1545–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Truzzi, F.; Marconi, A.; Lotti, R.; Dallaglio, K.; French, L.E.; Hempstead, B.L.; Pincelli, C. Neurotrophins and Their Receptors Stimulate Melanoma Cell Proliferation and Migration. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2008, 128, 2031–2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchetti, D.; Aucoin, R.; Blust, J.; Murry, B.; Greiter-Wilke, A. p75 neurotrophin receptor functions as a survival receptor in brain-metastatic melanoma cells. J. Cell. Biochem. 2004, 91, 206–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, A.S.; Risberg, B.; Magalhães, J.; Trovisco, V.; de Castro, I.V.; Lazarovici, P.; Soares, P.; Davidson, B.; Sobrinho-Simões, M. The p75 neurotrophin receptor is widely expressed in conventional papillary thyroid carcinoma. Hum. Pathol. 2006, 37, 562–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kettunen, E.; Anttila, S.; Seppänen, J.K.; Karjalainen, A.; Edgren, H.; Lindström, I.; Salovaara, R.; Nissén, A.-M.; Salo, J.; Mattson, K.; et al. Differentially expressed genes in nonsmall cell lung cancer: Expression profiling of cancer-related genes in squamous cell lung cancer. Cancer Genet. Cytogenet. 2004, 149, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuanlong, H.; Haifeng, J.; Xiaoyin, Z.; Jialin, S.; Jie, L.; Li, Y.; Huahong, X.; Jiugang, S.; Yanglin, P.; Kaichun, W.; et al. The inhibitory effect of p75 neurotrophin receptor on growth of human hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Cancer Lett. 2008, 268, 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khwaja, F.; Tabassum, A.; Allen, J.; Djakiew, D. The p75NTR tumor suppressor induces cell cycle arrest facilitating caspase mediated apoptosis in prostate tumor cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2006, 341, 1184–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Pan, Y.; Zhao, L.; Zhai, H.; Li, X.; Sun, L.; He, L.; Chen, Y.; Hong, L.; Du, Y.; et al. p75 Neurotrophin Receptor Suppresses the Proliferation of Human Gastric Cancer Cells. Neoplasia 2007, 9, 471–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabassum, A.; Khwaja, F.; Djakiew, D. The p75NTR tumor suppressor induces caspase-mediated apoptosis in bladder tumor cells. Int. J. Cancer 2003, 105, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsay, R.G.; Gonda, T.J. MYB function in normal and cancer cells. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2008, 8, 523–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biroccio, A.; Benassi, B.; D’Agnano, I.; D’Angelo, C.; Buglioni, S.; Mottolese, M.; Ricciotti, A.; Citro, G.; Cosimelli, M.; Ramsay, R.G. c-Myb and Bcl-x overexpression predicts poor prognosis in colorectal cancer: Clinical and experimental findings. Am. J. Pathol. 2001, 158, 1289–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greco, C.; Alvino, S.; Buglioni, S.; Assisi, D.; Lapenta, R.; Grassi, A.; Stigliano, V.; Mottolese, M.; Casale, V. Activation of c-MYC and c-MYB proto-oncogenes is associated with decreased apoptosis in tumor colon progression. Anticancer Res. 2001, 21, 3185–3192. [Google Scholar]

- van de Vijver, M.J.; He, Y.D.; van’t Veer, L.J.; Dai, H.; Hart, A.A.M.; Voskuil, D.W.; Schreiber, G.J.; Peterse, J.L.; Roberts, C.; Marton, M.J.; et al. A Gene-Expression Signature as a Predictor of Survival in Breast Cancer. N. Eng. J. Med. 2002, 347, 1999–2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guérin, M.; Sheng, Z.M.; Andrieu, N.; Riou, G. Strong association between c-myb and oestrogen-receptor expression in human breast cancer. Oncogene 1990, 5, 131–135. [Google Scholar]

- Anfossi, G.; Gewirtz, A.M.; Calabretta, B. An oligomer complementary to c-myb-encoded mRNA inhibits proliferation of human myeloid leukemia cell lines. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1989, 86, 3379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutwyche, J.K.; Keough, R.A.; Hughes, T.P.; Gonda, T.J. Mutation screening of the c-MYB negative regulatory domain in acute and chronic myeloid leukaemia. Br. J. Haematol. 2001, 114, 632–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuenda, A.; Rousseau, S. p38 MAP-Kinases pathway regulation, function and role in human diseases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Res. 2007, 1773, 1358–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Han, L.; Li, B.; Yang, J.; Huen, M.S.Y.; Pan, X.; Tsao, S.W.; Cheung, A.L.M. F-Box Only Protein 31 (FBXO31) Negatively Regulates p38 Mitogen-activated Protein Kinase (MAPK) Signaling by Mediating Lysine 48-linked Ubiquitination and Degradation of Mitogen-activated Protein Kinase Kinase 6 (MKK6). J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 21508–21518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotan, T.L.; Lyon, M.; Huo, D.; Taxy, J.B.; Brendler, C.; Foster, B.A.; Stadler, W.; Rinker-Schaeffer, C.W. Up-regulation of MKK4, MKK6 and MKK7 during prostate cancer progression: An important role for SAPK signalling in prostatic neoplasia. J. Pathol. 2007, 212, 386–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parray, A.A.; Baba, R.A.; Bhat, H.F.; Wani, L.; Mokhdomi, T.A.; Mushtaq, U.; Bhat, S.S.; Kirmani, D.; Kuchay, S.; Wani, M.M.; et al. MKK6 is Upregulated in Human Esophageal, Stomach, and Colon Cancers. Cancer Investig. 2014, 32, 416–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Liu, K.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, M.; Lu, R.; Folts, C.J.; Gao, X.; Noble, M.D.; Zhao, T.; Zhou, Z.; et al. Pharmacological targeting of p38 MAP-Kinase 6 (MAP2K6) inhibits the growth of esophageal adenocarcinoma. Cell. Signal. 2018, 51, 222–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satyal, S.H.; Chen, D.; Fox, S.G.; Kramer, J.M.; Morimoto, R.I. Negative regulation of the heat shock transcriptional response by HSBP1. Genes Dev. 1998, 12, 1962–1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eroglu, B.; Min, J.-N.; Zhang, Y.; Szurek, E.; Moskophidis, D.; Eroglu, A.; Mivechi, N.F. An essential role for heat shock transcription factor binding protein 1 (HSBP1) during early embryonic development. Dev. Biol. 2014, 386, 448–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, L.; Zhang, R.; Sun, Y.; Wang, X.; Deng, A.M.; Bi, L. Overexpression of HSBP1 is associated with resistance to radiotherapy in oral squamous epithelial carcinoma. Med. Oncol. 2014, 31, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phan, N.N.; Wang, C.Y.; Chen, C.F.; Sun, Z.; Lai, M.D.; Lin, Y.C. Voltage-gated calcium channels: Novel targets for cancer therapy. Oncol. Lett. 2017, 14, 2059–2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warnier, M.; Roudbaraki, M.; Derouiche, S.; Delcourt, P.; Bokhobza, A.; Prevarskaya, N.; Mariot, P. CACNA2D2 promotes tumorigenesis by stimulating cell proliferation and angiogenesis. Oncogene 2015, 34, 5383–5394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Costa Prando, É.; Cavalli, L.R.; Rainho, C. Evidence of epigenetic regulation of the tumor suppressor gene cluster flanking RASSF1 in breast cancer cell lines. Epigenetics 2011, 6, 1413–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, H.; Wang, J.; Bao, L.; Wang, L.; Huo, J.; Wang, X. Global analysis of chromosome 1 genes among patients with lung adenocarcinoma, squamous carcinoma, large-cell carcinoma, small-cell carcinoma, or non-cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2015, 34, 249–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natrajan, R.; Little, S.E.; Reis-Filho, J.S.; Hing, L.; Messahel, B.; Grundy, P.E.; Dome, J.S.; Schneider, T.; Vujanic, G.M.; Pritchard-Jones, K.; et al. Amplification and Overexpression of CACNA1E Correlates with Relapse in Favorable Histology Wilms’ Tumors. Clin. Cancer Res. 2006, 12, 7284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camps, M.; Nichols, A.; Arkinstall, S. Dual specificity phosphatases: A gene family for control of MAP kinase function. FASEB J. 2000, 14, 6–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.S. Role of mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatases (MKPs) in cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2007, 26, 579–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keyse, S.M. Dual-specificity MAP kinase phosphatases (MKPs) and cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2008, 27, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ratsada, P.; Hijiya, N.; Hidano, S.; Tsukamoto, Y.; Nakada, C.; Uchida, T.; Kobayashi, T.; Moriyama, M. DUSP4 is involved in the enhanced proliferation and survival of DUSP4-overexpressing cancer cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2020, 528, 586–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Song, L.; Ritchie, A.-M.; Melton, D.W. Increased levels of DUSP6 phosphatase stimulate tumourigenesis in a molecularly distinct melanoma subtype. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2012, 25, 188–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, L.A.; Ryan, K.M. Life and death decisions by E2F-1. Cell Death Differ. 2004, 11, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorgoulis, V.G.; Zacharatos, P.; Mariatos, G.; Kotsinas, A.; Bouda, M.; Kletsas, D.; Asimacopoulos, P.J.; Agnantis, N.; Kittas, C.; Papavassiliou, A.G. Transcription factor E2F-1 acts as a growth-promoting factor and is associated with adverse prognosis in non-small cell lung carcinomas. J. Pathol. 2002, 198, 142–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eymin, B.; Gazzeri, S.; Brambilla, C.; Brambilla, E. Distinct pattern of E2F1 expression in human lung tumours: E2F1 is upregulated in small cell lung carcinoma. Oncogene 2001, 20, 1678–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.Y.; Liu, S.C.; Al-Saleem, L.F.; Holloran, D.; Babb, J.; Guo, X.; Klein-Szanto, A.J.P. E2F-1: A Proliferative Marker of Breast Neoplasia. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2000, 9, 395. [Google Scholar]

- Saiz, A.D.; Olvera, M.; Rezk, S.; Florentine, B.A.; McCourty, A.; Brynes, R.K. Immunohistochemical expression of cyclin D1, E2F-1, and Ki-67 in benign and malignant thyroid lesions. J. Pathol. 2002, 198, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.L.; Liu, D.; Nakano, J.; Yokomise, H.; Ueno, M.; Kadota, K.; Wada, H. E2F1 Overexpression Correlates with Thymidylate Synthase and Survivin Gene Expressions and Tumor Proliferation in Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2007, 13, 6938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coutte, L.; Dreyer, C.; Sablin, M.-P.; Faivre, S.; Raymond, E. PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathway and cancer. Bull. Cancer 2012, 99, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García, Z.; Kumar, A.; Marqués, M.; Cortés, I.; Carrera, A.C. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase controls early and late events in mammalian cell division. EMBO J. 2006, 25, 655–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortés, I.; Sánchez-Ruíz, J.; Zuluaga, S.; Calvanese, V.; Marqués, M.; Hernández, C.; Rivera, T.; Kremer, L.; González-García, A.; Carrera, A.C. p85β phosphoinositide 3-kinase subunit regulates tumor progression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 11318–11323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.; Bao, Y.; Ma, M.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Yuan, M.; Liu, B.; Yang, Y.; Cui, W.; Ansong, E.; et al. Clinical significance of the correlation between PLCE 1 and PRKCA in esophageal inflammation and esophageal carcinoma. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 33285–33299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, S.; Simeonova, I.; Bielle, F.; Verreault, M.; Bance, B.; Le Roux, I.; Daniau, M.; Nadaradjane, A.; Gleize, V.; Paris, S.; et al. A recurrent point mutation in PRKCA is a hallmark of chordoid gliomas. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2371–2379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, S.; Ranade, A.R.; Tran, N.L.; Nasser, S.; Sridhar, S.; Korn, R.L.; Ross, J.T.D.; Dhruv, H.; Foss, K.M.; Sibenaller, Z.; et al. MicroRNA-328 is associated with (non-small) cell lung cancer (NSCLC) brain metastasis and mediates NSCLC migration. Int. J. Cancer 2011, 129, 2621–2631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, H.; Fu, Q.; Song, X.; Ge, C.; Li, R.; Li, Z.; Zeng, B.; Li, C.; Wang, Y.; Xue, Y.; et al. HDGF and PRKCA upregulation is associated with a poor prognosis in patients with lung adenocarcinoma. Oncol. Lett. 2019, 18, 4936–4946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, T.; Mizuno, S. The discovery of Hepatocyte Growth Factor (HGF) and its significance for cell biology, life sciences and clinical medicine. Proc. Jpn. Acad. Ser. B 2010, 86, 588–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morishita, R.; Aoki, M.; Hashiya, N.; Yamasaki, K.; Kurinami, H.; Shimizu, S.; Makino, H.; Takesya, Y.; Azuma, J.; Ogihara, T. Therapeutic Angiogenesis using Hepatocyte Growth Factor (HGF). Curr. Gene Ther. 2004, 4, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipriani, N.A.; Abidoye, O.O.; Vokes, E.; Salgia, R. MET as a target for treatment of chest tumors. Lung Cancer 2009, 63, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comoglio, P.M.; Boccaccio, C. Scatter factors and invasive growth. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2001, 11, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, P.C.; Jagadeeswaran, R.; Jagadeesh, S.; Tretiakova, M.S.; Nallasura, V.; Fox, E.A.; Hansen, M.; Schaefer, E.; Naoki, K.; Lader, A.; et al. Functional Expression and Mutations of c-Met and Its Therapeutic Inhibition with SU11274 and Small Interfering RNA in Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer. Cancer Res. 2005, 65, 1479–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, P.C.; Tretiakova, M.S.; Nallasura, V.; Jagadeeswaran, R.; Husain, A.N.; Salgia, R. Downstream signalling and specific inhibition of c-MET/HGF pathway in small cell lung cancer: Implications for tumour invasion. Br. J. Cancer 2007, 97, 368–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cecchi, F.; Rabe, D.C.; Bottaro, D.P. Targeting the HGF/Met signaling pathway in cancer therapy. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 2012, 16, 553–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiao, D.; Wang, J.; Lu, W.; Tang, X.; Chen, J.; Mou, H.; Chen, Q.-Y. Curcumin inhibited HGF-induced EMT and angiogenesis through regulating c-Met dependent PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathways in lung cancer. Mol. Ther. Oncolytics 2016, 3, 16018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, H.N.; Stenling, R.; Rubio, C.; Lindblom, A. Colorectal carcinogenesis is associated with stromal expression of COL11A1 and COL5A2. Carcinogenesis 2001, 22, 875–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, A.C.; Reed, A.E.M.; Waddell, N.; Lane, A.; Reid, L.E.; Smart, C.E.; Cocciardi, S.; da Silva, L.; Song, S.; Chenevix-Trench, G.; et al. Gene expression profiling of tumour epithelial and stromal compartments during breast cancer progression. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2012, 135, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.-T.; Liu, X.-P.; Liu, T.-Z.; Wang, X.-H. The clinical significance of COL5A2 in patients with bladder cancer: A retrospective analysis of bladder cancer gene expression data. Medicine 2018, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, D.; Chen, K.; Bai, Y.; Zhu, X.; Chen, Z.; Wang, C.; Zhao, Y.; Li, M. Screening of diagnostic markers for osteosarcoma. Mol. Med. Rep. 2014, 10, 2415–2420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, L.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, H.; Dong, N.; Su, X.; Xu, M.; Wang, X. Variations of chromosome 2 gene expressions among patients with lung cancer or non-cancer. Cell Biol. Toxicol. 2016, 32, 419–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barczyk, M.; Carracedo, S.; Gullberg, D. Integrins. Cell Tissue Res. 2009, 339, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiao, Y.; Li, Y.; Liu, S.; Chen, Q.; Liu, Y. ITGA3 serves as a diagnostic and prognostic biomarker for pancreatic cancer. OncoTargets Ther. 2019, 12, 4141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.-R.; Wen, X.; He, Q.-M.; Li, Y.-Q.; Ren, X.-Y.; Yang, X.-J.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.-Q.; Ma, J.; Liu, N. MicroRNA-101 inhibits invasion and angiogenesis through targeting ITGA3 and its systemic delivery inhibits lung metastasis in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cell Death Dis. 2018, 8, e2566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurozumi, A.; Goto, Y.; Matsushita, R.; Fukumoto, I.; Kato, M.; Nishikawa, R.; Sakamoto, S.; Enokida, H.; Nakagawa, M.; Ichikawa, T. Tumor-suppressive micro RNA-223 inhibits cancer cell migration and invasion by targeting ITGA 3/ITGB 1 signaling in prostate cancer. Cancer Sci. 2016, 107, 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sa, K.-D.; Zhang, X.; Li, X.-F.; Gu, Z.-P.; Yang, A.-G.; Zhang, R.; Li, J.-P.; Sun, J.-Y. A miR-124/ITGA3 axis contributes to colorectal cancer metastasis by regulating anoikis susceptibility. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2018, 501, 758–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakaguchi, T.; Yoshino, H.; Yonemori, M.; Miyamoto, K.; Sugita, S.; Matsushita, R.; Itesako, T.; Tatarano, S.; Nakagawa, M.; Enokida, H. Regulation of ITGA3 by the dual-stranded microRNA-199 family as a potential prognostic marker in bladder cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2017, 116, 1077–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wu, H.; Zhang, H.; Li, Y.; Li, S.; Hou, Q.; Wu, S.; Yang, S.-Y. Identification of curcumin-inhibited extracellular matrix receptors in non–small cell lung cancer A549 cells by RNA sequencing. Tumor Biol. 2017, 39, 1010428317705334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smrcka, A.V. Molecular targeting of Gα and Gβγ subunits: A potential approach for cancer therapeutics. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2013, 34, 290–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.M.; Sleno, R.; Gora, S.; Zylbergold, P.; Laverdure, J.-P.; Labbé, J.-C.; Miller, G.J.; Hébert, T.E. The expanding roles of Gβγ subunits in G protein–coupled receptor signaling and drug action. Pharmacol. Rev. 2013, 65, 545–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, H.; Kanda, M.; Miwa, T.; Umeda, S.; Sawaki, K.; Tanaka, C.; Kobayashi, D.; Hayashi, M.; Yamada, S.; Nakayama, G.; et al. G-protein subunit gamma-4 expression has potential for detection, prediction and therapeutic targeting in liver metastasis of gastric cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2021, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, L.; Zeng, J.-H.; Qin, X.-G.; Chen, J.-Q.; Luo, D.-Z.; Chen, G. Distinguishable prognostic signatures of left-and right-sided colon cancer: A study based on sequencing data. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2018, 48, 475–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katoh, M.; Nakagama, H. FGF receptors: Cancer biology and therapeutics. Med. Res. Rev. 2014, 34, 280–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Zhang, S.; Wei, L.; Wang, Z.; Ma, W.; Liu, F.; Qian, Y. FGF2 and FGFR2 in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and lung cancer. Oncol. Lett. 2018, 16, 2490–2494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosoya, T.; Nakata, A.; Yamasaki, F.; Abas, F.; Shaari, K.; Lajis, N.H.; Morita, H. Curcumin-like diarylpentanoid analogues as melanogenesis inhibitors. J. Nat. Med. 2012, 66, 166–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Compounds | EC50 Values (µM) | Selective Index (SX) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCI-H520 | NCI-H23 | MRC9 | NCI-H520 | NCI-H23 | |

| MS13 | 4.7 ± 0.1 | 3.7 ± 0.4 | 8.6 ± 0.6 | 181.4 | 232.4 |

| Curcumin | 25.19 ± 1.7 | 18.5 ± 0.7 | 27.4 ± 1.7 | 108.8 | 148.2 |

| Genes/Cell Line | Gene Description | Accession No. | Single/Multiple Pathways | FC | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCI-H520 | |||||

| PTEN | Phosphatase and Tensin Homolog | NM_000314.3:1675 | PI3K | 1.3 | 0.0233 |

| DDIT4 | DNA Damage Inducible Transcript 4 | NM_019058.2:85 | PI3K | 1.4 | 0.0223 |

| ENDOG | Endonuclease G | NM_004435.2:694 | Cell-cycle Apoptosis | 1.5 | 0.00367 |

| CASP8 | Caspase 8 | NM_001228.4:301 | Cell-cycle Apoptosis | 1.4 | 0.0341 |

| DDIT3 | DNA Damage Inducible Transcript 3 | NM_004083.4:40 | MAPK | 1.3 | 0.00325 |

| CDKN1A | Cyclin Dependent Kinase Inhibitor 1A | NM_000389.2:1975 | Cell-cycle Apoptosis and PI3K | 2.1 | 0.0006 |

| * CCND3 | Cyclin D3 | NM_001760.2:1215 | Cell-cycle Apoptosis and PI3K | 1.4 | 0.015 |

| GADD45G | Growth Arrest and DNA Damage Inducible Gamma | NM_006705.3:250 | Cell-cycle Apoptosis and MAPK | 2.1 | 0.000258 |

| NCI-H23 | |||||

| ITGA2 | Integrin Subunit Alpha 2 | NM_002203.2:475 | PI3K | 1.4 | 0.00405 |

| THEM4 | Thioesterase Superfamily Member 4 | NM_053055.4:764 | PI3K | 1.3 | 0.00716 |

| TNFRSF10A | TNF Receptor Superfamily Member 10a | NM_003840.3:2380 | Cell-cycle Apoptosis | 1.4 | 0.00918 |

| IRAK2 | Interleukin 1 Receptor Associated Kinase 2 | NM_001570.3:1285 | Cell-cycle Apoptosis | 1.4 | 0.00186 |

| DUSP2 | Dual Specificity Phosphatase 2 | NM_004418.3:1235 | MAPK | 1.3 | 0.0344 |

| * CCND3 | Cyclin D3 | NM_001760.2:1215 | Cell-cycle Apoptosis and PI3K | 1.3 | 0.00733 |

| Genes/Cell Line | Gene Description | Accession No. | Single/Multiple Pathways | FC | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCI-H520 | |||||

| EPHA2 | EPH Receptor A2 | NM_004431.2:1525 | PI3K | −2.0 | 0.00397 |

| NGFR | Nerve Growth Factor Receptor | NM_002507.1:2705 | PI3K | −2.0 | 0.00691 |

| MYB | MYB Proto-Oncogene, Transcription Factor | NM_005375.2:3145 | PI3K | −1.9 | 0.00042 |

| ITGB4 | Integrin Subunit Beta 4 | NM_001005731.1:4151 | PI3K | −1.7 | 0.00064 |

| COL4A5 | Collagen Type IV Alpha 5 Chain | NM_033381.1:5360 | PI3K | −1.7 | 0.00275 |

| * THBS1 | Thrombospondin 1 | NM_003246.2:3465 | PI3K | −1.7 | 0.00044 |

| KIT | KIT Proto-Oncogene, Receptor Tyrosine Kinase | NM_000222.1:5 | PI3K | −1.6 | 0.0418 |

| KITLG | KIT Ligand | NM_003994.4:1155 | PI3K | −1.5 | 0.00058 |

| PDGFD | Platelet Derived Growth Factor D | NM_025208.4:1120 | PI3K | −1.4 | 0.0496 |

| FN1 | Fibronectin 1 | NM_212482.1:1776 | PI3K | −1.3 | 0.00927 |

| ITGA2 | Integrin Subunit Alpha 2 | NM_002203.2:475 | PI3K | −1.3 | 0.0199 |

| * MCM-7 | Minichromosome Maintenance Complex Component 7 | NM_182776.1:1325 | Cell-cycle Apoptosis | −4.3 | 1.62 × 10−5 |

| E2F1 | E2F Transcription Factor 1 | NM_005225.1:935 | Cell-cycle Apoptosis | −1.5 | 0.00051 |

| MAP2K1 | Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Kinase 1 | NM_002755.2:970 | Cell-cycle Apoptosis | −1.4 | 0.00012 |

| CDKN2C | Cyclin Dependent Kinase Inhibitor 2C | NM_001262.2:1295 | Cell-cycle Apoptosis | −1.4 | 0.013 |

| PRKAR1B | Protein Kinase CAMP-Dependent Type I Regulatory Subunit Beta | NM_001164759.1:1112 | Cell-cycle Apoptosis | −1.4 | 0.00524 |

| CDKN2D | Cyclin-Dependent Kinase Inhibitor 2D | NM_001800.3:870 | Cell-cycle Apoptosis | −1.4 | 0.0333 |

| CASP7 | Caspase 7 | NM_001227.3:915 | Cell-cycle Apoptosis | −1.3 | 0.0198 |

| PKMYT1 | Protein Kinase, Membrane-Associated Tyrosine/Threonine 1 | NM_004203.3:780 | Cell-cycle Apoptosis | −1.3 | 0.00813 |

| HDAC10 | Histone Deacetylase 1 | NM_032019.5:932 | Cell-cycle Apoptosis | −1.3 | 0.00159 |

| MYD88 | Innate Immune Signal Transduction Adaptor | NM_002468.3:2145 | Cell-cycle Apoptosis | −1.3 | 0.00872 |

| * SKP2 | S-Phase Kinase-Associated Protein 2 | NM_005983.2:615 | Cell-cycle Apoptosis | −1.3 | 0.00401 |

| CACNA2D2 | Calcium Voltage-Gated Channel Auxiliary Subunit Alpha2delta 2 | NM_001005505.1:2045 | MAPK | −2.1 | 0.0113 |

| CACNA1E | Calcium Voltage-Gated Channel Subunit Alpha1 E | NM_000721.2:9325 | MAPK | −2.1 | 0.00435 |

| DUSP4 | Dual Specificity Phosphatase 4 | NM_057158.2:3115 | MAPK | −1.6 | 0.0319 |

| MAP2K6 | Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Kinase 6 | NM_002758.3:555 | MAPK | −1.5 | 0.00795 |

| * MAPT | Microtubule Associated Protein Tau | NM_016834.3:1205 | MAPK | −1.5 | 0.0469 |

| THSBP1 | Heat Shock Factor Binding Protein 1 | NM_003246.2:3465 | MAPK | −1.5 | 0.0123 |

| DUSP6 | Dual Specificity Phosphatase 6 | NM_001946.2:1535 | MAPK | −3.3 | 6.93 × 10−5 |

| RASGRP1 | RAS Guanyl Releasing Protein 1 | NM_005739.3:365 | MAPK | −1.7 | 0.0297 |

| PIK3R2 | Phosphoinositide-3-Kinase Regulatory Subunit 2 | NM_005027.2:3100 | Cell cycle-apoptosis and PI3K | −1.5 | 0.00943 |

| BAD | BCL2 Associated Agonist of Cell Death | NM_004322.3:652 | Cell cycle-apoptosis and PI3K | −1.4 | 0.00012 |

| CDK6 | Cyclin-Dependent Kinase 6 | NM_001259.5:15 | Cell cycle-apoptosis and PI3K | −1.4 | 0.00398 |

| PIK3R3 | Phosphoinositide-3-Kinase Regulatory Subunit 3 | NM_003629.3:1800 | Cell cycle-apoptosis and PI3K | −1.3 | 0.00023 |

| * PIK3CB | Phosphatidylinositol-4,5-Bisphosphate 3-Kinase Catalytic Subunit Beta | NM_006219.1:2945 | Cell cycle-apoptosis and PI3K | −1.3 | 0.00023 |

| FGF9 | Fibroblast Growth Factor 9 | NM_002010.2:1565 | PI3K and MAPK | −1.8 | 0.00742 |

| PRKCA | Protein Kinase C Alpha | NM_002737.2:5560 | PI3K and MAPK | −1.6 | 0.0235 |

| MAP2K1 | Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Kinase 1 | NM_002755.2:970 | PI3K and MAPK | −1.4 | 0.000117 |

| MAP2K2 | Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Kinase 2 | NM_030662.2:1325 | PI3K and MAPK | −1.4 | 0.00258 |

| * MAPK3 | Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase 3 | NM_001040056.1:580 | PI3K and MAPK | −1.3 | 0.016 |

| * TGFB2 | Transforming Growth Factor Beta 2 | NM_003238.2:1125 | Cell cycle-apoptosis and MAPK | −1.5 | 0.00123 |

| PRKACA | Protein Kinase CAMP-Activated Catalytic Subunit Alpha | NM_002730.3:400 | Cell cycle-apoptosis, PI3K and MAPK | −1.3 | 4.50 × 10−5 |

| AKT1 | AKT Serine/Threonine Kinase 1 | NM_005163.2:1772 | Cell cycle-apoptosis, PI3K and MAPK | −1.3 | 0.0007 |

| NCI-H23 | |||||

| HGF | Hepatocyte Growth Factor | NM_000601.4:550 | PI3K | −1.8 | 0.0285 |

| COL5A2 | Collagen Type V Alpha 2 Chain | NM_000393.3:4075 | PI3K | −1.7 | 0.00464 |

| GNG4 | G Protein Subunit Gamma 4 | NM_004485.2:215 | PI3K | −1.6 | 0.028 |

| MET | MET Proto-Oncogene, Receptor Tyrosine Kinase | NM_000245.2:405 | PI3K | −1.5 | 0.00293 |

| ITGA3 | Integrin Subunit Alpha 3 | NM_005501.2:1138 | PI3K | −1.5 | 0.0131 |

| * THBS1 | Thrombospondin 1 | NM_003246.2:3465 | PI3K | −1.4 | 0.00578 |

| IRS1 | Insulin Receptor Substrate 1 | NM_005544.2:6224 | PI3K | −1.4 | 0.00412 |

| EFNA3 | Ephrin A3 | NM_004952.4:1672 | PI3K | −1.4 | 0.0205 |

| EIF4EBP1 | Eukaryotic Translation Initiation Factor 4E Binding Protein 1 | NM_001429.2:715 | PI3K | −1.3 | 0.0184 |

| * MCM-7 | Minichromosome Maintenance Complex Component 7 | NM_182776.1:1325 | Cell-cycle Apoptosis | −1.7 | 0.00101 |

| CCNA1 | Cyclin A1 | NM_003914.3:1605 | Cell-cycle Apoptosis | −1.4 | 0.0264 |

| SMAD2 | SMAD Family Member 2 | NM_001003652.1:4500 | Cell-cycle Apoptosis | −1.4 | 0.0199 |

| CHEK2 | Checkpoint Kinase 2 | NM_007194.3:140 | Cell-cycle Apoptosis | −1.3 | 0.0398 |

| MAD2L2 | Mitotic Arrest Deficient 2 Like 2 | NM_001127325.1:290 | Cell-cycle Apoptosis | −1.3 | 0.0128 |

| * SKP2 | S-Phase Kinase Associated Protein 2 | NM_005983.2:615 | Cell-cycle Apoptosis | −1.3 | 0.00026 |

| CDC7 | Cell Division Cycle 7 | NM_003503.2:805 | Cell-cycle Apoptosis | −1.3 | 0.0302 |

| RAD21 | RAD21 Cohesin Complex Component | NM_006265.2:1080 | Cell-cycle Apoptosis | −1.3 | 0.0289 |

| * MAPT | Microtubule Associated Protein Tau | NM_016834.3:1205 | MAPK | −1.5 | 0.0469 |

| RAC3 | Rac Family Small GTPase 3 | NM_005052.2:702 | MAPK | −1.4 | 0.0439 |

| FLNA | Filamin A | NM_001456.3:7335 | MAPK | −1.3 | 0.00262 |

| * PIK3CB | Phosphatidylinositol-4,5-Bisphosphate 3-Kinase Catalytic Subunit Beta | NM_006219.1:2945 | Cell cycle-apoptosis and PI3K | −1.3 | 0.0272 |

| FAS | Fas Cell Surface Death Receptor | NM_152876.1:1740 | Cell cycle-apoptosis and MAPK | −1.4 | 0.00328 |

| PPP3CA | Protein Phosphatase 3 Catalytic Subunit Alpha | NM_000944.4:3920 | Cell cycle-apoptosis and MAPK | −1.3 | 0.0223 |

| * TGFB2 | Transforming Growth Factor Beta 2 | NM_003238.2:1125 | Cell cycle-apoptosis and MAPK | −1.6 | 0.0104 |

| FGFR2 | Fibroblast Growth Factor Receptor 2 | NM_000141.4:647 | PI3K and MAPK | −1.6 | 0.0265 |

| FGF2 | Fibroblast Growth Factor 2 | NM_002006.4:620 | PI3K and MAPK | −1.4 | 0.00307 |

| FGFR4 | Fibroblast Growth Factor Receptor 4 | NM_002011.3:1585 | PI3K and MAPK | −1.3 | 0.027 |

| * MAPK3 | Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase 3 | NM_001040056.1:580 | PI3K and MAPK | −1.4 | 0.0425 |

| TP53 | Tumor Protein P53 | NM_000546.2:1330 | Cell cycle-apoptosis, PI3K and MAPK | −1.3 | 0.00783 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wan Mohd Tajuddin, W.N.B.; Abas, F.; Othman, I.; Naidu, R. Molecular Mechanisms of Antiproliferative and Apoptosis Activity by 1,5-Bis(4-Hydroxy-3-Methoxyphenyl)1,4-Pentadiene-3-one (MS13) on Human Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7424. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22147424

Wan Mohd Tajuddin WNB, Abas F, Othman I, Naidu R. Molecular Mechanisms of Antiproliferative and Apoptosis Activity by 1,5-Bis(4-Hydroxy-3-Methoxyphenyl)1,4-Pentadiene-3-one (MS13) on Human Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Cells. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2021; 22(14):7424. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22147424

Chicago/Turabian StyleWan Mohd Tajuddin, Wan Nur Baitty, Faridah Abas, Iekhsan Othman, and Rakesh Naidu. 2021. "Molecular Mechanisms of Antiproliferative and Apoptosis Activity by 1,5-Bis(4-Hydroxy-3-Methoxyphenyl)1,4-Pentadiene-3-one (MS13) on Human Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Cells" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 22, no. 14: 7424. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22147424

APA StyleWan Mohd Tajuddin, W. N. B., Abas, F., Othman, I., & Naidu, R. (2021). Molecular Mechanisms of Antiproliferative and Apoptosis Activity by 1,5-Bis(4-Hydroxy-3-Methoxyphenyl)1,4-Pentadiene-3-one (MS13) on Human Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Cells. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 22(14), 7424. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22147424