Abstract

Background: Parkinson’s disease (PD) is the second most frequent neurodegenerative disease, which creates a significant public health burden. There is a challenge for the optimization of therapies since patients not only respond differently to current treatment options but also develop different side effects to the treatment. Genetic variability in the human genome can serve as a biomarker for the metabolism, availability of drugs and stratification of patients for suitable therapies. The goal of this systematic review is to assess the current evidence for the clinical translation of pharmacogenomics in the personalization of treatment for Parkinson’s disease. Methods: We performed a systematic search of Medline database for publications covering the topic of pharmacogenomics and genotype specific mutations in Parkinson’s disease treatment, along with a manual search, and finally included a total of 116 publications in the review. Results: We analyzed 75 studies and 41 reviews published up to December of 2020. Most research is focused on levodopa pharmacogenomic properties and catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) enzymatic pathway polymorphisms, which have potential for clinical implementation due to changes in treatment response and side-effects. Likewise, there is some consistent evidence in the heritability of impulse control disorder via Opioid Receptor Kappa 1 (OPRK1), 5-Hydroxytryptamine Receptor 2A (HTR2a) and Dopa decarboxylase (DDC) genotypes, and hyperhomocysteinemia via the Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) gene. On the other hand, many available studies vary in design and methodology and lack in sample size, leading to inconsistent findings. Conclusions: This systematic review demonstrated that the evidence for implementation of pharmacogenomics in clinical practice is still lacking and that further research needs to be done to enable a more personalized approach to therapy for each patient.

1. Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is the second most common neurodegenerative disease present today. The incidence and prevalence are highest in the population aged ≥65 years old, making the disease a significant public health burden in the elderly [1]. The clinical course of the disease is progressive and is defined by motor symptoms such as resting tremor, bradykinesia and rigidity, along with a wide variety of non-motor symptoms such as autonomic dysfunction, sleep disorders, cognitive deficits and behavioural changes [2]. The first symptoms appear several years before the classic motor symptoms during the prodromal PD, which is marked by non-specific symptoms like constipation and insomnia [3]. Our understanding of underlying mechanisms in PD has significantly increased over recent years. The main postulated pathological mechanisms in PD include the intracellular aggregation of α-synuclein, which form Lewy bodies [4], as well as the loss of dopaminergic neurons, which first happens in the substantia nigra but later becomes more widespread as the disease progresses [5]. The landmark paper published by Braak et al. describes a gradually evolving pathological severity, starting from the lower brainstem, with a progression to the limbic and neocortical brain regions in the later stages of PD [6].

The variation of clinical states between patients can be significant, even though the underlying mechanisms are similar. Efforts have been made to categorize the disease into varying subtypes. Seyed-Mohammad et al. [7] propose three subtypes based predominantly on clinical characteristics: the mild motor, intermediate and diffuse malignant subtypes. Importantly, findings from the study indicated that neuroimaging correlated better with the subtypes than genetic information, even after incorporating a single “genetic risk score” that encompassed 30 specific PD-related mutations. However, this could also be a consequence of a lack of patients with particular variations in the population they studied [7]. The need to categorize the disease comes from its variability in presentation, response to treatment and incidence of side-effects.

Current treatment options for PD are plentiful, at least in comparison to other neurodegenerative diseases, and offer PD patients extended control of symptom severity as well as an improved quality of life. Unfortunately, no treatment halts the pathological mechanisms that drive disease progression, with most treatment being focused on replacing or enhancing dopamine availability. The golden standard in pharmacologic therapy is dopamine replacement therapy, mainly levodopa, used in synergy with dopamine receptor agonists, monoamine oxidase (MAO) inhibitors or catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) inhibitors [8]. The challenge that stems from this type of therapy is the delicate balance between the beneficial and harmful effects that can arise [9]. There is a significant variation in therapy response and side-effect incidence in treating PD, which can be linked to the varied subtypes mentioned earlier, along with increasing evidence of complex environmental and genetic factor interaction [10,11,12]. The consequence of this is the need to fine-tune and personalize the therapy to each patient to account for the variability in drug response [8]. As most treatment is focused on L-dopa, understanding the key players in its metabolism has put the research focus in pharmacogenomics on genes that influence the enzymes and receptors in this pathway [13]. The general principles and goals of pharmacogenomics are to identify the genetic factors behind the varied drug response in individuals, thereby predicting response and paving the way for personalised medicine [14]. The two main areas where the variability of drug response is studied are known as pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. Pharmacokinetics incorporates all processes that affect drug absorption, distribution and metabolism in the body as well as its excretion, while pharmacodynamics focuses on the target actions of the drug. Current evidence suggests that genetic variability and its effects on drug characteristics are concentrated in three major steps: the initial pharmacokinetic processes that ultimately affect the plasma concentration, the capability of drugs in passing the blood-brain barrier (BBB) and finally, the modification of target pharmacodynamic properties of the drug [13]. Expanding the knowledge of the variations that affect these three factors will pave the way for predicting drug response, thus furthering the benefit of a personalized medicine approach in all diseases. Unfortunately, there are currently no clinical guidelines regarding the use of pharmacogenomics in the clinical practice of treating PD, with sparse clinical annotations on relevant databases [15]. Therefore, our aim is to assess the current state of knowledge in this field and the possibility of translation into the clinics.

2. Results

Current treatment in PD is focused on alleviating the symptoms and does little to slow down the pathophysiological progression of the disease. As such, the therapy goal is to increase the amount of dopamine to compensate for the loss of dopaminergic neurons. The therapeutic of choice for this is levodopa (L-dopa), which relieves the motor symptoms by increasing the availability of dopamine in the central nervous system (CNS) [16]. All the current pharmaceutical treatment options centre around the dopamine metabolic pathway, which encompasses many genetic pathways. However, there are specific pharmacogenomic properties for different treatment options, as well as differences in pharmacogenomic properties in genotype driven PD.

2.1. Drug Specific Pharmacogenomic Properties

2.1.1. Pharmacogenomics of the Therapeutic Response to L-dopa

Clinically, L-dopa is always combined with dopa decarboxylase (DDC) inhibitors, which causes a switch in L-dopa metabolism to the COMT pathway, thereby increasing the bioavailability of L-dopa in the CNS [16]. The genetic variability of several genes has been implicated in the varied response to L-dopa. COMT gene is a protein-coding gene that provides instructions for creating the COMT enzyme, and its polymorphisms are involved in the varied response to numerous CNS diseases and treatments [17,18]. The most studied polymorphism of the COMT gene is rs4680 (G>A), which results in a valine to methionine substitution at codon 158 (Val158Met). Single nucleotide polymorphisms of the COMT gene form haplotypes that result in lower (A_C_C_G), medium (A_T_C_A) and higher (G_C_G_G) enzyme activity, which, in the case of higher activity, had an impact on the required dosage compared to noncarriers [19] (Table 1). Studies have shown that the higher dosage is required during chronic administration in patients with greater COMT activity, while acute L-dopa administration was unchanged [20,21,22]. Similar changes were observed in a recent study by Sampaio et al., where higher COMT enzyme activity was linked to higher doses of L-dopa required, while no significant changes in dosage were found in lower COMT enzymatic activity compared to the control [23]. Common characteristics of patients that required the higher L-dopa dosage in multiple studies were advanced PD and earlier onset. A contradicting result was published in patients of Korean origins, with no significant association between the rs4680 polymorphism and the response to L-dopa; however, the study population did not have a considerable number of patients with advanced PD [24]. Higher L-dopa doses were needed for patients with Solute Carrier Family 22 Member 1 (SLC22A1) gene rs622342A>C polymorphism that encodes the Organic Cation Transporter 1, along with the patients having higher mortality than the control population [25]. On the other hand, lower required doses of L-dopa were found in patients with Synaptic vesicle glycoprotein 2C (SV2C) rs30196 polymorphism, as well as in Solute Carrier Family 6 Member 3 (SLC6A3) polymorphism after multivariate analysis [26].

Table 1.

Pharmacogenomic studies cited in the systematic review.

2.1.2. Pharmacogenomics of the Side-Effects to L-dopa

Increased incidence of adverse events in L-dopa treatment has been linked with various gene polymorphisms. Although the variations in COMT enzymatic activity on the onset of adverse events is still under debate, several studies have linked the lower COMT enzymatic activity to the increased incidence of motor complications such as dyskinesia, especially in advanced PD [23,27]. Hypothetically, more moderate COMT enzymatic activity could lead to inadequate dopamine inactivation and the accumulation of dopamine in the synaptic cleft, thereby causing the dyskinesias. The same result was not replicated in studies by Watanabe et al. [28] and Contin et al. [22].

There is some evidence that the activation of the Mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling pathway contributes to L-dopa induced dyskinesia. It was indicative of earlier animal studies that the inhibition of mTOR pathways reduces the L-dopa related dyskinesia, most likely due to impaired metabolic homeostasis [78]. These findings were corroborated in a recent human study, by Martin-Flores et al., that found significant associations with several SNPs affecting the mTOR pathway, indicating that the mTOR pathway contributes genetically to L-dopa induced dyskinesia susceptibility [29]. Similarly, a functional Brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) Val66Met polymorphism can lead to aberrant synaptic plasticity, which has been associated with L-dopa induced dyskinesia in a single study by Foltynie et al. [30]. Limited evidence has been found in favour of a protective function of the Dopamine receptor 1 (DRD1) (rs4532) SNP, shown in a single study by Dos Santos et al. [31]. The effect of Dopamine receptor 2 (DRD2) SNP’s on dyskinesia is a point of contention in current literature, as some studies indicate an increased risk of developing dyskinesia [31,32,33], while others revealed a protective effect on the incidence of dyskinesia [34,35]. Interestingly, both studies that show reduced dyskinesias were conducted in the Italian population with the polymorphism DRD2 CAn-STR. Increased risk for developing L-dopa induced dyskinesia was seen in the Dopamine receptor 3 (DRD3) rs6280 polymorphism in a Korean population [36]. However, opposing results were found by three research groups, with no evidence of correlation between DRD3 genetic polymorphisms and incidence of dyskinesias [37,38,39]. Lower risk of L-dopa-associated dyskinesias was found in patients with Homer protein homolog 1 (HOMER1) rs4704560 G allele polymorphism [40]. Finally, incidence of L-dopa induced dyskinesias was studied for the dopamine transporter gene (DAT), where the presence of two genotypes 10R/10R (rs28363170) and A carrier (rs393795) led to a reduced risk of dyskinesias in an Italian population [41].

Hyperhomocysteinemia is a known complication of L-dopa treatment in PD. The potential dangers of elevated plasma homocysteine are systemic, and include cardiovascular risk, increased risk for dementia and impaired bone health [79]. A SNP C667T (rs1801133) in the MTHFR gene is consistently being linked to hyperhomocysteinemia due to L-dopa treatment in several studies. The result of this mutation is a temperature-labile MTHFR enzyme, which ultimately leads to hyperhomocysteinemia [42]. In addition, a study by Gorgone et al. showed that elevated homocysteine levels lead to systemic oxidative stress in patients with this polymorphism [43]. A recent study by Yuan et al. further adds to the claim that homocysteine levels are affected by L-dopa administration, especially in 677C/T and T/T genotypes [44]. A possible option for homocysteine level reduction and alleviation of systemic oxidative stress is the addition of COMT inhibitors to the therapy, which presents a clear possibility for translation of this knowledge into the treatment of patients [79].

There is contradicting evidence regarding whether COMT polymorphisms can influence the incidence of daytime sleepiness in PD patients, with differing results of the pilot and follow-up studies conducted by the same authors [45,46]. Two additional studies by the same primary author revealed an association between sudden-sleep onset and the polymorphisms in hypocretin and DRD2, which was unrelated to a specific drug [47,48]. Furthermore, increased risk of sleep attacks was found in Dopamine receptor 4 (DRD4) 48-bp VNTR polymorphism in a German population [39]. The L-dopa adverse effects affecting emetic activity are not uncommon in PD treatment. DRD2 and DRD3 polymorphisms both showed an association with an increased risk of developing gastrointestinal adverse effects that do not respond well to therapy in a Brazilian population [32,49]. However, that has not been reproduced in a recent study in a Slovenian population by Redenšek et al. [50].

Mental and cognitive adverse effects of L-dopa are common due to the shared physiological dopaminergic pathways. A significant interaction was found between L-dopa and the COMT gene polymorphism in causing a detrimental effect on the activity in task-specific regions of the pre-frontal cortex due to altered availability of dopamine [51,52]. Interestingly, carriers of at least one COMT rs165815 C allele had a decreased risk of developing visual hallucinations [50]. In the same study carriers of the DRD3 rs6280 C allele had higher odds of developing visual hallucinations [50], which is in line with a previous study published by Goetz et al. [53]. Increased risk of developing hallucinations is seen in patients with polymorphisms in the DRD2 gene [54], cholecystokinin gene [55] and HOMER1 rs4704559 A allele [56], which encodes a protein that possesses a vital function for synaptic plasticity and glutamate signaling. On the other hand, the HOMER 1 rs4704559 G allele appears to decrease the risk of visual hallucinations [40]. Furthermore, several studies link BDNF Val66Met polymorphism to impaired cognitive functioning in PD, but it appears to be irrespective of dopamine replacement therapy and is a genotype-specific trait [57].

Impulse control disorder (ICD) is a well-known complication that can occur in some PD patients after initiating dopamine replacement therapy by either L-dopa or dopamine agonists [58]. Heritability of ICD in a cohort of PD patients has been estimated at 57%, particularly for Opioid Receptor Kappa 1 (OPRK1), 5-Hydroxytryptamine Receptor 2A (HTR2a) and Dopa decarboxylase (DDC) genotypes [80]. A recent study found a suggestive association for developing ICD in variants of the opioid receptor gene OPRM1 and the DAT gene [59]. Furthermore, there is evidence that polymorphisms in DRD1 (rs4857798, rs4532, rs265981), DRD2/ANKK1 (rs1800497) and glutamate ionotropic receptor NMDA type subunit 2B (GRIN2B) (rs7301328) bear an increased risk of developing ICD [60,81]. The DRD3 (rs6280) mutation has also been linked with increased incidence of ICD with L-dopa therapy in studies by Lee et al. [61] and Castro-Martinez et al. [62]. On the other hand, there was no significant association found in COMT Val158Met and DRD2 Taq1A polymorphisms [81]. Even though current data suggest high heritability for developing ICD after initiating dopamine replacement therapy, it should be noted that the effects of individual genes are small, and the development is most likely multigenic.

2.1.3. Dopamine Receptor Agonists

Dopamine receptor agonists (DAs) are often the first therapies initiated in PD patients and are the main alternative to L-dopa [82]. The effectiveness of DAs is lower than L-dopa, and most patients discontinue treatment within three years. Some significance has been found in polymorphisms of the DRD2 and DRD3 genes that could influence drug effectiveness and tolerability. A retrospective study by Arbouw et al. revealed that a DRD2 (CA)n-repeat polymorphism is linked with a decreased discontinuation of non-ergoline DA treatment, although the sample size in this study was small [63]. A pilot study that included Chinese PD patients revealed that the DRD3 Ser9Gly (rs6280) polymorphism is associated with a varied response to pramipexole [64], which has since been confirmed in a recent study by Xu et al. [65].

Interestingly, the same polymorphism has also been linked with depression severity in PD, indicating that in DRD3 Ser9Gly patients with Ser/Gly and Gly/Gly genotypes more care should be given to adjusting therapy and caring for non-motor complications [66]. Furthermore, there is evidence from the aforementioned studies that DRD2 Taq1A polymorphism does not play a significant role in response to DA treatment [64,65,67]. On the other hand, certain Taq1A polymorphisms (rs1800497) have been associated with differences in critical cognitive control processes depending on allele expression [67]. As mentioned earlier, another crucial pharmacogenomic characteristic of DA to bear in mind when administering therapy is the possibility of genotype driven impulse control disorders, which is a problem, especially in de-novo PD patients starting DA therapy [80]. Genetic model of polymorphisms in DRD1 (rs5326), OPRK1 (rs702764), OPRM1 (rs677830) and COMT (rs4646318) genes had a high prediction of ICD in patients of DA therapy (AUC of 0.70 (95% CI: 0.61–0.79) [68].

2.1.4. COMT Inhibitors

COMT inhibitors are potent drugs that increase the bioavailability of L-dopa by stopping the physiological O-methylation of levodopa to its metabolite 3-O-methyldopa, and can work in tandem with DDC inhibitors [69]. Similar to L-dopa, the presence of the previously mentioned rs4608 COMT gene polymorphism modified the motor response to COMT inhibitors entacapone in a small-sample study [83]. Patients with higher COMT enzyme activity had greater response compared to patients with lower COMT enzyme activity during the acute challenge with entacapone [83]. Subsequent studies have not found clinically significance in repeated administration of either entacapone [70] or tolcapone [71], with the impact on opicapone still unknown, meriting further study. Increased doses of carbidopa combined with levodopa and entacapone can improve “off” times, which was shown in a recent randomized trial by Trenkwalder et al., with an even more pronounced effect in patients that had higher COMT enzymatic activity due to COMT gene polymorphisms [72].

Pharmacokinetic studies have shown that COMT inhibitors are metabolized in the liver by glucuronidation, in particular by UDP-glucuronyltransferase UGT1A and UGT1A9 enzymes [82]. Hepatotoxicity is a known rare side-effect of tolcapone [73], with only sparse reports of entacapone hepatotoxicity [84]. Several studies indicate that SNPs in the UGT1A and UGT1A9 are responsible for these adverse events, which can cause inadequate metabolism and subsequent damage to the liver by the drugs [74,75,85,86]. Interestingly, opicapone has not demonstrated evident hepatotoxicity related adverse events, while in-vitro studies show a favorable effect on hepatocytes when compared to entacapone and tolcapone [76].

2.1.5. MAO Inhibitors

MAO inhibitors are used with L-dopa to extend its duration due to reduced degradation in the CNS. Most MAO inhibitors used today in PD treatment (e.g., selegiline, rasagiline) are focused on blocking the MAO-B enzyme that is the main isoform responsible for the degradation of dopamine [87]. There have not been many studies performed to assess MAO inhibitor pharmacogenetic properties. Early clinical studies with rasagiline did reveal an inter-individual variation in the quality of response that could not be adequately explained at that time [88]. Masellisi et al. conducted an extensive study using the ADAGIO study data to identify possible genetic determinants that can alter the response to rasagiline. They identified two SNPs on the DRD2 gene that were associated with statistically significant improvement of both motor and mental functions after 12 weeks of treatment [89].

2.2. Genotype Specific Treatment and Pharmacogenomic Properties

Gene variations that influence pharmacogenomic properties and treatment in PD are not only focused on the metabolic and activity pathways of the drugs. There is a wide number of genes that are linked to monogenic PD, but only some had their association proven continuously in various research studies. Mutations in the genes coding α-Synuclein (SNCA), Leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2), vacuolar protein sorting-associated protein 35 (VPS35), parkin RBR E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase (PRKN), PTEN-induced putative kinase 1 (PINK1), glucocerebrosidase (GBA) and oncogene DJ-1 [77] have mostly been found before the onset of genome-wide association studies, while many candidate genes found after are yet to be definitively proven to cause a significant risk for PD. Importantly, the currently known candidate genes can explain only a small fraction of cases where there is a known higher familial incidence of PD [90]. It is remarkable, however, that assessing polygenic risk scores and combining those with specific clinical parameters can yield impressive sensitivity of 83.4% and specificity of 90% [91] (Table 2.). The unfortunate consequence of the rapid expansion of knowledge in the field and amount of target genes is that the studies assessing pharmacogenomics of these gene variants are not keeping up.

Table 2.

Genotype specific Parkinson’s disease studies cited in the manuscript.

2.2.1. LRRK2

Current evidence, albeit limited, points to differences in treatment response between various genotypes of monogenic PD. Mutations in the LRRK2 gene are known to cause familial PD, especially in North African and Ashkenazi Jew populations [92]. LRRK2 protein has a variety of physiological functions in intracellular trafficking and cytoskeleton dynamics, along with a substantial role in the cells of innate immunity. It is yet unclear how mutations in LRRK2 influence the pathogenesis of PD, but there is numerous evidence that links it to a disorder in cellular homeostasis and subsequent α-synuclein aggregation [105]. Results in in vitro and in vivo animal model studies for inhibition of mutant LRRK2 are promising, and in most cases, confirm a reduced degeneration of dopaminergic neurons [106]. The biggest challenge of human trials has been creating an LRRK2 inhibitor that can pass the blood-brain barrier, which was overcome by Denali Therapeutics, and the phase-1b trial for their novel LRRK2 inhibitor has been completed and is awaiting official results [105]. Furthermore, LRRK2-associated PD has a similar response to L-dopa compared to sporadic PD, with conflicting results for the possible earlier development of motor symptoms [13]. Pharmacogenomics in LRRK2 associated PD are linked to specific genotype variants. G2019S and G2385R variants in LRRK2 have been linked as predictors of motor complications due to L-dopa treatment, along with requiring higher doses during treatment [107]. On the other hand, G2019S carrier status did not influence the prevalence of L-dopa induced dyskinesias in a study by Yahalom et al. [93]. Furthermore, a study covering the pharmacogenetics of Atremorine, a novel bioproduct with neuroprotective effects of dopaminergic neurons, found that LRRK2 associated PD patients had a more robust response to the compound, along with several genes that cover metabolic and detoxification pathways [94].

2.2.2. SNCA

SNCA gene encodes the protein α-synuclein, now considered a central player in the pathogenesis of PD due to its aggregation into Lewy-bodies. SNP’s in the SNCA gene are consistently linked to an increased risk of developing PD in GWAS studies in both familial and even sporadic PD [95]. In cases of autosomal dominant mutations, there is a solid L-dopa and classical PD treatment response, albeit with early cognitive and mental problems, akin to GBA mutations [108]. There are several planned therapeutic approaches suited for SNCA polymorphism genotypes which include: targeted monoclonal antibody immunotherapy of α-synuclein [96], downregulation of SNCA expression by targeted DNA editing [109] and RNA interference of SNCA [97]. Roche Pharmaceuticals has developed an anti-α-synuclein monoclonal antibody which is in a currently ongoing phase two of clinical trials [110]. Two other methods are still in preclinical testing, and their development shows promise for the future.

2.2.3. GBA

Glucocerebrosidase mutations represent a known risk factor for developing PD. GBA mutation associated PD is characterized by the earlier onset of the disease, followed by a more pronounced cognitive deficit and a significantly higher risk of dementia [98]. Gaucher’s disease (GD) is an autosomal recessive genetic disorder that also arises from mutations in the GBA gene. The current enzyme replacement and chaperone treatment options for systemic manifestations of GD are not effective enough in treating the neurological manifestations of the disease as they are not able to reach the CNS [111]. Three genotype-specific therapies to address the cognitive decline are currently being tested with promising early results, with two focusing on the chaperones ambroxol [112] and LTI-291 to increase glucocerebrosidase activity and the third focusing on reducing the levels of glucocerebrosidase with ibiglustat [98]. There is growing evidence that GBA associated PD is often marked by rapid progression with many hallmarks of advanced PD, such as higher L-dopa daily dose required to control motor symptoms [99]. However, current research does not show a significant influence of GBA mutations on L-dopa response properties with adequate motor symptom control [100]. A single study by Lesage et al. in a population of European origin linked a higher incidence of L-dopa induced dyskinesias in GBA-PD patients [113], but that has not been replicated in a more recent study by Zhang et al. in a population of Chinese origin [101].

2.2.4. PRKN/PINK1/DJ1

Mutations in the PRKN gene can lead to early onset PD, characterized by a clinically typical form of PD that is often associated with dystonia and dyskinesia [102]. Patients with PRKN mutations generally have excellent and sustained responses to L-dopa, even in lower doses than in sporadic PD [103]. Dyskinesias can occur early on in the course of the disease with very low doses of L-dopa [114], while dystonia in these patients was not found to be linked to L-dopa treatment [102]. Furthermore, patients with PINK1 mutations have a similar disease course as PRKN mutation carriers, with a good response to L-dopa treatment, but early dystonia and L-dopa induced dyskinesias [102]. Pharmacogenomic properties and genotype-specific treatment of several other gene mutations in PD such as VPS35 and DJ1 have not yet been characterized fully due to the rarity of cases and are currently a focus of several studies that as of writing do not have preliminary results available [90,115,116].

3. Discussion

There has been considerable progress in the field of pharmacogenomics in Parkinson’s disease. The main question in the field is whether we can use the current knowledge in clinical practice to benefit the patients. The data on Parkinson’s disease in PharmGKB, a pharmacogenomics database, are sparse, with only ten clinical annotations with most being supported by a rather low level of evidence, which is clear from this systematic review as well [15]. Most of the pharmacogenomic studies that focus on antiparkinsonian drugs are highly centered on L-dopa and its metabolism. The current evidence on the pharmacogenomics of therapeutic response to L-dopa is contradictory, with most studies focusing on the COMT gene polymorphisms. The differences between studies limit the potential for clinical use. However, there is potential to clarify the effects of COMT gene polymorphisms by further studies analyzing the enzymatic activity in various genotypes and the L-dopa dosage and therapeutic response. More robust evidence is present for the pharmacogenomics of side-effects in L-dopa or dopaminergic therapy. The most studied motor complication of L-dopa therapy is treatment-induced dyskinesias. Looking at the evidence, we can see that there are numerous reports focusing on various genes, although often with contradictory results in COMT, DRD2 and DRD3 genes. On the other hand, SNPs in the mTOR pathway genes, BDNF, HOMER1 and DAT have been implicated in either increased or reduced risk for dyskinesias, but with single studies that are yet to be corroborated in larger cohorts. Other side-effects such as cognitive decline, visual hallucinations and daytime sleepiness have been implicated in various polymorphisms of the COMT, DRD2, DRD3, HOMER1 and BDNF genes, but lack consistency in the results to consider current clinical implementations.

Hyperhomocysteinemia and ICD are known complications of dopaminergic therapy, and both have been consistently linked with genetic factors [42,43,79]. Specifically, mutations in the MTHFR gene can increase the incidence of hyperhomocysteinemia, which could be ameliorated by the addition of COMT inhibitors to therapy, presenting a possibility for clinical interventions based on pharmacogenomic testing. The same can be said about ICD, where genetic models are gaining accuracy with each new study in the field [60,62]. Potential for clinical use can especially be seen in younger patients which are only starting dopamine agonist therapy, as polymorphisms in DRD1 (rs5326), OPRK1 (rs702764), OPRM1 (rs677830) and COMT (rs4646318) genes showed a high prediction rate of ICD [68]. There is evidence that polymorphisms in DRD2 and DRD3 gene could also cause these side-effects, leading to earlier discontinuation of DA therapy in patients. There is clear potential for clinical implementation in this area, and future goal should be to establish studies with larger cohorts in order to improve the genetic prediction models.

There is lacking evidence regarding the pharmacogenomic properties of other drugs used in PD, such as COMT and MAO inhibitors. However, there is some evidence that mutations leading to varied COMT enzyme activity could have an influence on the potency of COMT inhibitors, but the results are not consistent [70,71]. More consistent results have been found regarding entacapone hepatotoxicity, with several studies indicating that SNP’s in the UGT1A and UGT1A9 could lead to this adverse effect [74,75,76]. MAO inhibitors are known to have inter-individual variation, which is still not explained in current studies, with a single study reporting improved motor and mental functions in DRD2 gene SNP. Taken together, the pharmacogenomic data regarding COMT and MAO inhibitors are still not strong enough to make any recommendations for clinical implementation.

Finally, pharmacogenomics in PD also encompasses changes that occur in specific differences in genotype-associated PD. Three of the most studied single gene mutations are the LRRK2, GBA and SNCA gene mutations. Published studies covering L-dopa treatment with these mutations have contradicting results depending on the populations studied, which makes it difficult to give any firm recommendations regarding treatment optimization [93,94,96,101,102]. The current evidence for PRKN, PINK1 and DJ1 point to a sustained L-dopa response with lower doses, albeit with early motor complications that include dyskinesias and dystonia [103,114,115]. Therefore, this clinical phenotype can raise suspicions of these mutations and lead to earlier genetic testing and treatment optimization. However, the number of cases analyzed is low due to the rarity of these mutations, and further studies are required to confirm these early findings.

4. Materials and Methods

We have done a systematic search of articles indexed in Medline and Embase from its inception to July of 2020 focused on the pharmacogenomics in Parkinson’s disease using a strategy similar to what was described by Corvol et al. [13]. The search terms included: Genetic Variation (MeSH), Genotype (MeSH), Genes (MeSH), Polymorphism, Allele, Mutation, Treatment outcome (MeSH), Therapeutics (MeSH), Pharmacogenomic (MeSH), Pharmacogenetics (MeSH), Adverse effects (MeSH Subheading), Toxicogenetics (MeSH) and Parkinson’s disease (MeSH). The articles included in the search were clinical trials, meta-analysis, and randomized controlled trial, with excluding case reports and reviews, with additional filters of human studies and English language. We included studies that had a clear methodology regarding study population and main findings. Exclusion criteria were articles not written in English, lacking study population information and findings not relevant to the theme of pharmacogenomics in PD. Several reviews were added into the overall analyzed papers using manual searches through websites and citation searching. PharmGKB database was accessed as well using the search parameter “Parkinson’s disease” to view current clinical annotations present for PD [15].

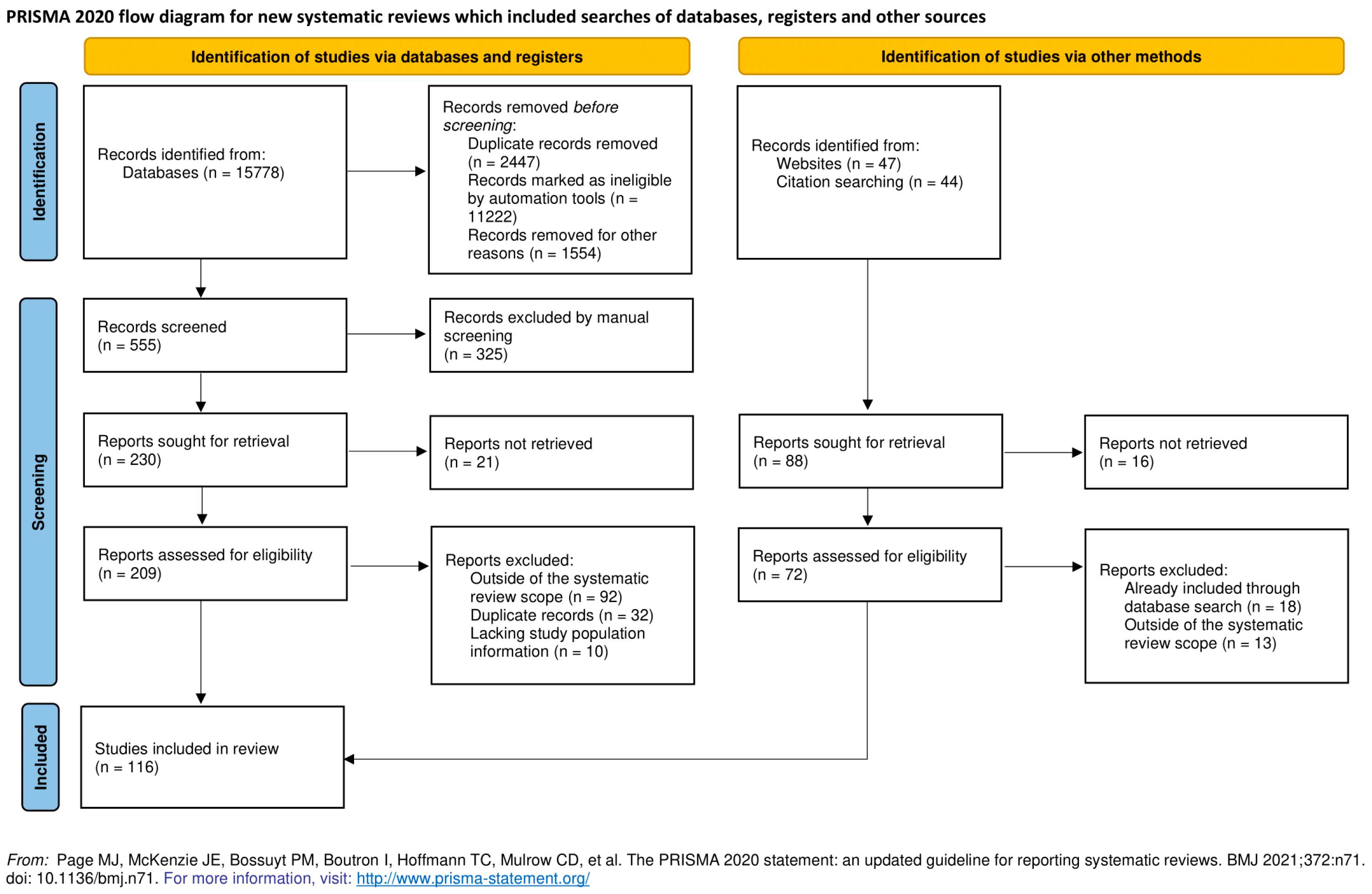

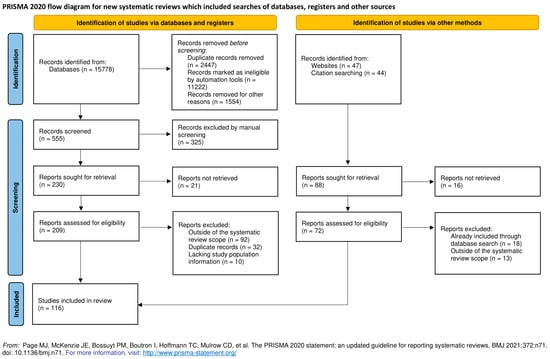

The systematic literature search in Medline and Embase revealed 15,778 potential publications, which were first automatically and then manually filtered to exclude studies that do not fit the inclusion criteria (Figure 1). We included 75 studies, with the final count being 116 after adding publications found through manual search that include reviews covering this topic, along with studies focused on genotype specific PD forms (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Prisma flow diagram for the systematic review [117].

5. Conclusions

Most pharmacogenomic data for PD treatment present today are still not consistent enough to be entered into clinical practice, and further studies are required to enable a more personalized approach to therapy for each patient. The main findings can be summarized as follows:

- Most evidence from the analyzed studies is found via secondary endpoints, which limits their power, with small sample size also being a diminishing factor.

- Conflicting reports between varied populations could be a consequence of low sample sizes and unaccounted interactions, which ultimately leads to low confidence in the data currently available.

- The most promising avenues for clinical implementation of pharmacogenetics lie in the current findings of impulse control disorders and hyperhomocysteinemia, where the available data are more consistent.

- Most of the studies focus on L-dopa and DA, and greater focus should also be given to other PD treatment options such as MAO-B and COMT inhibitors.

Even though the wealth of knowledge is rapidly increasing, there are still not enough consistent data to make quality choices in the clinical treatment of patients. Studies that have a clear focus on pharmacogenomic properties of antiparkinsonian drugs are key for consolidating the current information and for the translation into clinical practice.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.V., V.R., B.P.; methodology, V.V., V.R., E.P.; formal analysis, V.V., V.R.; investigation, V.V., V.R.; data curation, V.V., B.P.; writing—original draft preparation, V.V., V.R.; writing—review and editing, V.V., V.R., E.P., B.P.; supervision, B.P.; funding acquisition, V.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the Croatian Science Foundation (Grant IP-2019-04-7276) and by the University of Rijeka (Grants uniri-biomed-18-1981353).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Poewe, W.; Seppi, K.; Tanner, C.M.; Halliday, G.M.; Brundin, P.; Volkmann, J.; Schrag, A.E.; Lang, A.E. Parkinson disease. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2017, 3, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuletic, V.; Racki, V.; Chudy, D.; Bogdanovic, N. Deep Brain Stimulation in Non-motor Symptoms of Neurodegenerative diseases. In Neuromodulation Guiding the Advance of Research and Therapy [Working Title]; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Heinzel, S.; Berg, D.; Gasser, T.; Chen, H.; Yao, C.; Postuma, R.B. Update of the MDS research criteria for prodromal Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 2019, 34, 1464–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloem, B.R.; Okun, M.S.; Klein, C. Parkinson’s disease. Lancet 2021, 397, 2284–2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damier, P.; Hirsch, E.C.; Agid, Y.; Graybiel, A.M. The substantia nigra of the human brain: II. Patterns of loss of dopamine-containing neurons in Parkinson’s disease. Brain 1999, 122, 1437–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braak, H.; Del Tredici, K.; Rüb, U.; De Vos, R.A.I.; Jansen Steur, E.N.H.; Braak, E. Staging of brain pathology related to sporadic Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging 2003, 24, 197–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fereshtehnejad, S.-M.; Zeighami, Y.; Dagher, A.; Postuma, R.B. Clinical criteria for subtyping Parkinson’s disease: Biomarkers and longitudinal progression. Brain 2017, 140, 1959–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciccacci, C.; Borgiani, P. Pharmacogenomics in Parkinson’s disease: Which perspective for developing a personalized medicine? Neural Regen. Res. 2019, 14, 75–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olanow, C.W.; Obeso, J.A.; Stocchi, F. Continuous dopamine-receptor treatment of Parkinson’s disease: Scientific rationale and clinical implications. Lancet Neurol. 2006, 5, 677–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Jiménez, F.J.; Alonso-Navarro, H.; García-Martín, E.; Agúndez, J.A.G. Advances in understanding genomic markers and pharmacogenetics of Parkinsons disease. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2016, 12, 433–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Džoljić, E.; Novaković, I.; Krajinovic, M.; Grbatinić, I.; Kostić, V. Pharmacogenetics of drug response in Parkinson’s disease. Int. J. Neurosci. 2015, 125, 635–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacabelos, R. Parkinson’s disease: From pathogenesis to pharmacogenomics. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corvol, J.C.; Poewe, W. Pharmacogenetics of Parkinson’s Disease in Clinical Practice. Mov. Disord. Clin. Pract. 2017, 4, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Krebs, K.; Milani, L. Translating pharmacogenomics into clinical decisions: Do not let the perfect be the enemy of the good. Hum. Genomics 2019, 13, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Parkinson Disease—Clinical Annotations. Available online: https://www.pharmgkb.org/disease/PA445254/clinicalAnnotation (accessed on 30 April 2020).

- Salat, D.; Tolosa, E. Levodopa in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease: Current status and new developments. J. Parkinsons Dis. 2013, 3, 255–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Craddock, N.; Owen, M.J.; O’Donovan, M.C. The catechol-O-methyl transferase (COMT) gene as a candidate for psychiatric phenotypes: Evidence and lessons. Mol. Psychiatry 2006, 11, 446–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Stein, D.J.; Newman, T.K.; Savitz, J.; Ramesar, R. Warriors versus worriers: The role of COMT gene variants. CNS Spectr. 2006, 11, 745–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bialecka, M.; Kurzawski, M.; Klodowska-Duda, G.; Opala, G.; Tan, E.K.; Drozdzik, M. The association of functional catechol-O-methyltransferase haplotypes with risk of Parkinsons disease, levodopa treatment response, and complications. Pharmacogenet. Genomics 2008, 18, 815–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheshire, P.; Bertram, K.; Ling, H.; O’Sullivan, S.S.; Halliday, G.; McLean, C.; Bras, J.; Foltynie, T.; Storey, E.; Williams, D.R. Influence of single nucleotide polymorphisms in COMT, MAO-A and BDNF genes on dyskinesias and levodopa use in Parkinson’s disease. Neurodegener. Dis. 2013, 13, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Białecka, M.; Droździk, M.; Kłodowska-Duda, G.; Honczarenko, K.; Gawrońska-Szklarz, B.; Opala, G.; Stankiewicz, J. The effect of monoamine oxidase B (MAOB) and catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) polymorphisms on levodopa therapy in patients with sporadic Parkinson’s disease. Acta Neurol. Scand. 2004, 110, 260–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contin, M.; Martinelli, P.; Mochi, M.; Riva, R.; Albani, F.; Baruzzi, A. Genetic polymorphism of catechol-O-methyltransferase and levodopa pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic pattern in patient with parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 2005, 20, 734–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampaio, T.F.; dos Santos, E.U.D.; de Lima, G.D.C.; dos Anjos, R.S.G.; da Silva, R.C.; Asano, A.G.C.; Asano, N.M.J.; Crovella, S.; de Souza, P.R.E. MAO-B and COMT Genetic Variations Associated With Levodopa Treatment Response in Patients With Parkinson’s Disease. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2018, 58, 920–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.S.; Lyoo, C.H.; Ulmanen, I.; Syvänen, A.C.; O Rinne, J. Genotypes of catechol-O-methyltransferase and response to levodopa treatment in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Neurosci. Lett. 2001, 298, 131–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, M.L.; Visser, L.E.; Van Schaik, R.H.N.; Hofman, A.; Uitterlinden, A.G.; Stricker, B.H.C. OCT1 polymorphism is associated with response and survival time in anti-Parkinsonian drug users. Neurogenetics 2011, 12, 79–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Altmann, V.; Schumacher-Schuh, A.F.; Rieck, M.; Callegari-Jacques, S.M.; Rieder, C.R.M.; Hutz, M.H. Influence of genetic, biological and pharmacological factors on levodopa dose in Parkinson’s disease. Pharmacogenomics 2016, 17, 481–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lau, L.M.L.; Verbaan, D.; Marinus, J.; Heutink, P.; Van Hilten, J.J. Catechol-O-methyltransferase Val158Met and the risk of dyskinesias in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 2012, 27, 132–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, M.; Harada, S.; Nakamura, T.; Ohkoshi, N.; Yoshizawa, K.; Hayashi, A.; Shoji, S. Association between catechol-O-methyltransferase gene polymorphisms and wearing-off and dyskinesia in Parkinson’s disease. Neuropsychobiology 2003, 48, 190–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Flores, N.; Fernández-Santiago, R.; Antonelli, F.; Cerquera, C.; Moreno, V.; Martí, M.J.; Ezquerra, M.; Malagelada, C. MTOR Pathway-Based Discovery of Genetic Susceptibility to L-DOPA-Induced Dyskinesia in Parkinson’s Disease Patients. Mol. Neurobiol. 2019, 56, 2092–2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foltynie, T.; Cheeran, B.; Williams-Gray, C.H.; Edwards, M.J.; Schneider, S.A.; Weinberger, D.; Rothwell, J.C.; Barker, R.A.; Bhatia, K.P. BDNF val66met influences time to onset of levodopa induced dyskinesia in Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2009, 80, 141–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dos Santos, E.U.D.; Sampaio, T.F.; Tenório dos Santos, A.D.; Bezerra Leite, F.C.; da Silva, R.C.; Crovella, S.; Asano, A.G.C.; Asano, N.M.J.; de Souza, P.R.E. The influence of SLC6A3 and DRD2 polymorphisms on levodopa-therapy in patients with sporadic Parkinson’s disease. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2019, 71, 206–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieck, M.; Schumacher-Schuh, A.F.; Altmann, V.; Francisconi, C.L.; Fagundes, P.T.; Monte, T.L.; Callegari-Jacques, S.M.; Rieder, C.R.; Hutz, M.H. DRD2 haplotype is associated with dyskinesia induced by levodopa therapy in Parkinson’s disease patients. Pharmacogenomics 2012, 13, 1701–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strong, J.A.; Dalvi, A.; Revilla, F.J.; Sahay, A.; Samaha, F.J.; Welge, J.A.; Gong, J.; Gartner, M.; Yue, X.; Yu, L. Genotype and smoking history affect risk of levodopa-induced dyskinesias in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 2006, 21, 654–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zappia, M.; Annesi, G.; Nicoletti, G.; Arabia, G.; Annesi, F.; Messina, D.; Pugliese, P.; Spadafora, P.; Tarantino, P.; Carrideo, S.; et al. Sex differences in clinical and genetic determinants of levodopa peak-dose dyskinesias in Parkinson disease: An exploratory study. Arch. Neurol. 2005, 62, 601–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveri, R.L.; Annesi, G.; Zappia, M.; Civitelli, D.; Montesanti, R.; Branca, D.; Nicoletti, G.; Spadafora, P.; Pasqua, A.A.; Cittadella, R.; et al. Dopamine D2 receptor gene polymorphism and the risk of levodopa-induced dyskinesias in PD. Neurology 1999, 53, 1425–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.Y.; Cho, J.; Lee, E.K.; Park, S.S.; Jeon, B.S. Differential genetic susceptibility in diphasic and peak-dose dyskinesias in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 2011, 26, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaiser, R.; Hofer, A.; Grapengiesser, A.; Gasser, T.; Kupsch, A.; Roots, I.; Brockmöller, J. L-Dopa-induced adverse effects in PD and dopamine transporter gene polymorphism. Neurology 2003, 60, 1750–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu, Z.L.; Chen, B. Association study of dopamine D2, D3 receptor gene polymorphisms with motor fluctuations in PD. Neurology 2001, 56, 1757–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paus, S.; Gadow, F.; Knapp, M.; Klein, C.; Klockgether, T.; Wüllner, U. Motor complications in patients form the German Competence Network on Parkinson’s disease and the DRD3 Ser9Gly polymorphism. Mov. Disord. 2009, 24, 1080–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacher-Schuh, A.F.; Altmann, V.; Rieck, M.; Tovo-Rodrigues, L.; Monte, T.L.; Callegari-Jacques, S.M.; Medeiros, M.S.; Rieder, C.R.M.; Hutz, M.H. Association of common genetic variants of HOMER1 gene with levodopa adverse effects in Parkinson’s disease patients. Pharm. J. 2014, 14, 289–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purcaro, C.; Vanacore, N.; Moret, F.; Di Battista, M.E.; Rubino, A.; Pierandrei, S.; Lucarelli, M.; Meco, G.; Fattapposta, F.; Pascale, E. DAT gene polymorphisms (rs28363170, rs393795) and levodopa-induced dyskinesias in Parkinson’s disease. Neurosci. Lett. 2019, 690, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bonis, M.L.; Tessitore, A.; Pellecchia, M.T.; Longo, K.; Salvatore, A.; Russo, A.; Ingrosso, D.; Zappia, V.; Barone, P.; Galletti, P.; et al. Impaired transmethylation potential in Parkinson’s disease patients treated with l-Dopa. Neurosci. Lett. 2010, 468, 287–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorgone, G.; Currò, M.; Ferlazzo, N.; Parisi, G.; Parnetti, L.; Belcastro, V.; Tambasco, N.; Rossi, A.; Pisani, F.; Calabresi, P.; et al. Coenzyme Q10, hyperhomocysteinemia and MTHFR C677T polymorphism in levodopa-treated Parkinson’s disease patients. NeuroMolecular Med. 2012, 14, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, R.Y.; Sheu, J.J.; Yu, J.M.; Hu, C.J.; Tseng, I.J.; Ho, C.S.; Yeh, C.Y.; Hung, Y.L.; Chiang, T.R. Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase polymorphisms and plasma homocysteine in levodopa-treated and non-treated Parkinson’s disease patients. J. Neurol. Sci. 2009, 287, 64–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frauscher, B.; Högl, B.; Maret, S.; Wolf, E.; Brandauer, E.; Wenning, G.K.; Kronenberg, M.F.; Kronenberg, F.; Tafti, M.; Poewe, W. Association of daytime sleepiness with COMT polymorphism in patients with parkinson disease: A pilot study. Sleep 2004, 27, 733–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rissling, I.; Frauscher, B.; Kronenberg, F.; Tafti, M.; Stiasny-Kolster, K.; Robyr, A.-C.; Körner, Y.; Oertel, W.H.; Poewe, W.; Högl, B.; et al. Daytime sleepiness and the COMT val158met polymorphism in patients with Parkinson disease. Sleep 2006, 29, 108–111. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rissling, I.; Körner, Y.; Geller, F.; Stiasny-Kolster, K.; Oertel, W.H.; Möller, J.C. Preprohypocretin polymorphisms in Parkinson disease patients reporting “sleep attacks”. Sleep 2005, 28, 871–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rissling, I.; Geller, F.; Bandmann, O.; Stiasny-Kolster, K.; Körner, Y.; Meindorfner, C.; Krüger, H.P.; Oertel, W.H.; Möller, J.C. Dopamine receptor gene polymorphisms in Parkinson’s disease patients reporting “sleep attacks”. Mov. Disord. 2004, 19, 1279–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieck, M.; Schumacher-Schuh, A.F.; Altmann, V.; Callegari-Jacques, S.M.; Rieder, C.R.M.; Hutz, M.H. Association between DRD2 and DRD3 gene polymorphisms and gastrointestinal symptoms induced by levodopa therapy in Parkinson’s disease. Pharm. J. 2018, 18, 196–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redenšek, S.; Flisar, D.; Kojovic, M.; Kramberger, M.G.; Georgiev, D.; Pirtošek, Z.; Trošt, M.; Dolžan, V. Dopaminergic pathway genes influence adverse events related to dopaminergic treatment in Parkinson’s disease. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nombela, C.; Rowe, J.B.; Winder-Rhodes, S.E.; Hampshire, A.; Owen, A.M.; Breen, D.P.; Duncan, G.W.; Khoo, T.K.; Yarnall, A.J.; Firbank, M.J.; et al. Genetic impact on cognition and brain function in newly diagnosed Parkinson’s disease: ICICLE-PD study. Brain 2014, 137, 2743–2758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams-Gray, C.H.; Hampshire, A.; Barker, R.A.; Owen, A.M. Attentional control in Parkinson’s disease is dependent on COMT val 158 met genotype. Brain 2008, 131, 397–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goetz, C.G.; Burke, P.F.; Leurgans, S.; Berry-Kravis, E.; Blasucci, L.M.; Raman, R.; Zhou, L. Genetic variation analysis in Parkinson disease patients with and without hallucinations: Case-control study. Arch. Neurol. 2001, 58, 209–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Makoff, A.J.; Graham, J.M.; Arranz, M.J.; Forsyth, J.; Li, T.; Aitchison, K.J.; Shaikh, S.; Grünewald, R.A. Association study of dopamine receptor gene polymorphisms with drug-induced hallucinations in patients with idiopathic Parkinson’s disease. Pharmacogenetics 2000, 10, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Si, Y.M.; Liu, Z.L.; Yu, L. Cholecystokinin, cholecystokinin-A receptor and cholecystokinin-B receptor gene polymorphisms in Parkinson’s disease. Pharmacogenetics 2003, 13, 365–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Luca, V.; Annesi, G.; De Marco, E.V.; De Bartolomeis, A.; Nicoletti, G.; Pugliese, P.; Muscettola, G.; Barone, P.; Quattrone, A. HOMER1 promoter analysis in Parkinson’s disease: Association study with psychotic symptoms. Neuropsychobiology 2009, 59, 239–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Liu, J.; Guo, Y.; Dong, G.; Zou, W.; Chen, Z. Association between BDNF G196A (Val66Met) polymorphism and cognitive impairment in patients with Parkinson’s disease: A meta-analysis. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2019, 52, e8443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gatto, E.M.; Aldinio, V. Impulse Control Disorders in Parkinson’s Disease. A Brief and Comprehensive Review. Front. Neurol. 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cormier-Dequaire, F.; Bekadar, S.; Anheim, M.; Lebbah, S.; Pelissolo, A.; Krack, P.; Lacomblez, L.; Lhommée, E.; Castrioto, A.; Azulay, J.P.; et al. Suggestive association between OPRM1 and impulse control disorders in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 2018, 33, 1878–1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zainal Abidin, S.; Tan, E.L.; Chan, S.-C.; Jaafar, A.; Lee, A.X.; Abd Hamid, M.H.N.; Abdul Murad, N.A.; Pakarul Razy, N.F.; Azmin, S.; Ahmad Annuar, A.; et al. DRD and GRIN2B polymorphisms and their association with the development of impulse control behaviour among Malaysian Parkinson’s disease patients. BMC Neurol. 2015, 15, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, J.Y.; Lee, E.K.; Park, S.S.; Lim, J.Y.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, J.S.; Jeon, B.S. Association of DRD3 and GRIN2B with impulse control and related behaviors in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 2009, 24, 1803–1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Martínez, X.H.; García-Ruiz, P.J.; Martínez-García, C.; Martínez-Castrillo, J.C.; Vela, L.; Mata, M.; Martínez-Torres, I.; Feliz-Feliz, C.; Palau, F.; Hoenicka, J. Behavioral addictions in early-onset Parkinson disease are associated with DRD3 variants. Park. Relat. Disord. 2018, 49, 100–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbouw, M.E.L.; Movig, K.L.L.; Egberts, T.C.G.; Poels, P.J.E.; Van Vugt, J.P.P.; Wessels, J.A.M.; Van Der Straaten, R.J.H.M.; Neef, C.; Guchelaar, H.J. Clinical and pharmacogenetic determinants for the discontinuation of non-ergoline dopamine agonists in Parkinson’s disease. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2009, 65, 1245–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, Y.Z.; Tang, B.S.; Yan, X.X.; Liu, J.; Ouyang, D.S.; Nie, L.N.; Fan, L.; Li, Z.; Ji, W.; Hu, D.L.; et al. Association of the DRD2 and DRD3 polymorphisms with response to pramipexole in Parkinson’s disease patients. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2009, 65, 679–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Liu, J.; Yang, X.; Qian, Y.; Xiao, Q. Association of the DRD2 CAn-STR and DRD3 Ser9Gly polymorphisms with Parkinson’s disease and response to dopamine agonists. J. Neurol. Sci. 2017, 372, 433–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhi, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Si, Q.; Wang, M.; Shen, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, K. The Association between DRD3 Ser9Gly Polymorphism and Depression Severity in Parkinson’s Disease. Parkinsons. Dis. 2019, 2019, 1642087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paus, S.; Grünewald, A.; Klein, C.; Knapp, M.; Zimprich, A.; Janetzky, B.; Möller, J.C.; Klockgether, T.; Wüllner, U. The DRD2 TaqIA polymorphism and demand of dopaminergic medication in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 2008, 23, 599–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonell, K.E.; van Wouwe, N.C.; Harrison, M.B.; Wylie, S.A.; Claassen, D.O. Taq1A polymorphism and medication effects on inhibitory action control in Parkinson disease. Brain Behav. 2018, 8, 1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erga, A.H.; Dalen, I.; Ushakova, A.; Chung, J.; Tzoulis, C.; Tysnes, O.B.; Alves, G.; Pedersen, K.F.; Maple-Grødem, J. Dopaminergic and opioid pathways associated with impulse control disorders in Parkinson’s disease. Front. Neurol. 2018, 9, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Corvol, J.C.; Bonnet, C.; Charbonnier-Beaupel, F.; Bonnet, A.M.; Fiévet, M.H.; Bellanger, A.; Roze, E.; Meliksetyan, G.; Ben Djebara, M.; Hartmann, A.; et al. The COMT Val158Met polymorphism affects the response to entacapone in Parkinson’s disease: A randomized crossover clinical trial. Ann. Neurol. 2011, 69, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.S.; Kim, H.S.; Cho, E.K.; Lim, J.H.; Rinne, J.O. COMT genotype and effectiveness of entacapone in patients with fluctuating Parkinson’s disease. Neurology 2002, 58, 564–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, D.J.; Suchowersky, O.; Szumlanski, C.; Weinshilboum, R.M.; Brant, R.; Campbell, N.R.C. The relationship between COMT genotype and the clinical effectiveness of tolcapone, a COMT inhibitor, in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Clin. Neuropharmacol. 2000, 23, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trenkwalder, C.; Kuoppamäki, M.; Vahteristo, M.; Müller, T.; Ellmén, J. Increased dose of carbidopa with levodopa and entacapone improves “off” time in a randomized trial. Neurology 2019, 92, E1487–E1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, W.; Ramírez, J.; Gamazon, E.R.; Mirkov, S.; Chen, P.; Wu, K.; Sun, C.; Cox, N.J.; Cook, E.; Das, S.; et al. Genetic factors affecting gene transcription and catalytic activity of UDP-glucuronosyltransferases in human liver. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2014, 23, 5558–5569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yamanaka, H.; Nakajima, M.; Katoh, M.; Hara, Y.; Tachibana, O.; Yamashita, J.; McLeod, H.L.; Yokoi, T. A novel polymorphism in the promoter region of human UGT1A9 gene (UGT1A9*22) and its effects on the transcriptional activity. Pharmacogenetics 2004, 14, 329–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, M.; Martignoni, E.; Blandini, F.; Riboldazzi, G.; Bono, G.; Marino, F.; Cosentino, M. Association of UDP-glucuronosyltransferase 1A9 polymorphisms with adverse reactions to catechol-O-methyltransferase inhibitors in Parkinson’s disease patients. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2012, 68, 1493–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masellis, M.; Collinson, S.; Freeman, N.; Tampakeras, M.; Levy, J.; Tchelet, A.; Eyal, E.; Berkovich, E.; Eliaz, R.E.; Abler, V.; et al. Dopamine D2 receptor gene variants and response to rasagiline in early Parkinson’s disease: A pharmacogenetic study. Brain 2016, 139, 2050–2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Santini, E.; Heiman, M.; Greengard, P.; Valjent, E.; Fisone, G. Inhibition of mTOR signaling in parkinson’s disease prevents L-DOPA-induced dyskinesia. Sci. Signal. 2009, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zoccolella, S.; Lamberti, P.; Armenise, E.; De Mari, M.; Lamberti, S.V.; Mastronardi, R.; Fraddosio, A.; Iliceto, G.; Livrea, P. Plasma homocysteine levels in Parkinson’s disease: Role of antiparkinsonian medications. Park. Relat. Disord. 2005, 11, 131–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraemmer, J.; Smith, K.; Weintraub, D.; Guillemot, V.; Nalls, M.A.; Cormier-Dequaire, F.; Moszer, I.; Brice, A.; Singleton, A.B.; Corvol, J.C. Clinical-genetic model predicts incident impulse control disorders in Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2016, 87, 1106–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bhattacharjee, S. Impulse Control Disorders in Parkinson’s Disease: Pathophysiology, Effect of Genetic Polymorphism and Future Research Directions. Austin J. Clin. Neurol. 2017, 4, 1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agúndez, J.A.G.; García-Martín, E.; Alonso-Navarro, H.; Jiménez-Jiménez, F.J. Anti-Parkinson’s disease drugs and pharmacogenetic considerations. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2013, 9, 859–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonifácio, M.J.; Palma, P.N.; Almeida, L.; Soares-da-Silva, P. Catechol-O-methyltransferase and Its Inhibitors in Parkinson’s Disease. CNS Drug Rev. 2007, 13, 352–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, N. Tolcapone in Parkinson’s disease: Liver toxicity and clinical efficacy. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 2005, 4, 69–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martignoni, E.; Cosentino, M.; Ferrari, M.; Porta, G.; Mattarucchi, E.; Marino, F.; Lecchini, S.; Nappi, G. Two patients with COMT inhibitor-induced hepatic dysfunction and UGT1A9 genetic polymorphism. Neurology 2005, 65, 1820–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplowitz, N. Idiosyncratic drug hepatotoxicity. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2005, 4, 489–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonifácio, M.J.; Torrão, L.; Loureiro, A.I.; Palma, P.N.; Wright, L.C.; Soares-Da-Silva, P. Pharmacological profile of opicapone, a third-generation nitrocatechol catechol-O-methyl transferase inhibitor, in the rat. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2015, 172, 1739–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Youdim, M.B.H.; Edmondson, D.; Tipton, K.F. The therapeutic potential of monoamine oxidase inhibitors. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2006, 7, 295–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guay, D.R.P. Rasagiline (TVP-1012): A new selective monoamine oxidase inhibitor for Parkinson’s disease. Am. J. Geriatr. Pharmacother. 2006, 4, 330–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Repici, M.; Giorgini, F. DJ-1 in Parkinson’s Disease: Clinical Insights and Therapeutic Perspectives. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bandres-Ciga, S.; Diez-Fairen, M.; Kim, J.J.; Singleton, A.B. Genetics of Parkinson’s disease: An introspection of its journey towards precision medicine. Neurobiol. Dis. 2020, 137, 104782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nalls, M.A.; McLean, C.Y.; Rick, J.; Eberly, S.; Hutten, S.J.; Gwinn, K.; Sutherland, M.; Martinez, M.; Heutink, P.; Williams, N.M.; et al. Diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease on the basis of clinical and genetic classification: A population-based modelling study. Lancet Neurol. 2015, 14, 1002–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Pan, H.; Xu, Q.; Guo, J.; Tang, B.; Sun, Q. Clinical heterogeneity among LRRK2 variants in Parkinson’s disease: A Meta-analysis. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2018, 10, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yahalom, G.; Kaplan, N.; Vituri, A.; Cohen, O.S.; Inzelberg, R.; Kozlova, E.; Korczyn, A.D.; Rosset, S.; Friedman, E.; Hassin-Baer, S. Dyskinesias in patients with Parkinson’s disease: Effect of the leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2) G2019S mutation. Park. Relat. Disord. 2012, 18, 1039–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacabelos, R.; Carrera, I.; Alejo, R.; Fernández-Novoa, L.; Cacabelos, P.; Corzo, L.; Rodríguez, S.; Alcaraz, M.; Tellado, I.; Cacabelos, N.; et al. Pharmacogenetics of Atremorine-Induced Neuroprotection and Dopamine Response in Parkinson’s Disease. Planta Med. 2019, 85, 1351–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishioka, K.; Ross, O.A.; Ishii, K.; Kachergus, J.M.; Ishiwata, K.; Kitagawa, M.; Kono, S.; Obi, T.; Mizoguchi, K.; Inoue, Y.; et al. Expanding the clinical phenotype of SNCA duplication carriers. Mov. Disord. 2009, 24, 1811–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantor, B.; Tagliafierro, L.; Gu, J.; Zamora, M.E.; Ilich, E.; Grenier, C.; Huang, Z.Y.; Murphy, S.; Chiba-Falek, O. Downregulation of SNCA Expression by Targeted Editing of DNA Methylation: A Potential Strategy for Precision Therapy in PD. Mol. Ther. 2018, 26, 2638–2649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jankovic, J.; Goodman, I.; Safirstein, B.; Marmon, T.K.; Schenk, D.B.; Koller, M.; Zago, W.; Ness, D.K.; Griffith, S.G.; Grundman, M.; et al. Safety and Tolerability of Multiple Ascending Doses of PRX002/RG7935, an Anti--Synuclein Monoclonal Antibody, in Patients with Parkinson Disease: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Neurol. 2018, 75, 1206–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silveira, C.R.A.; MacKinley, J.; Coleman, K.; Li, Z.; Finger, E.; Bartha, R.; Morrow, S.A.; Wells, J.; Borrie, M.; Tirona, R.G.; et al. Ambroxol as a novel disease-modifying treatment for Parkinson’s disease dementia: Protocol for a single-centre, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. BMC Neurol. 2019, 19, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alcalay, R.N.; Levy, O.A.; Waters, C.C.; Fahn, S.; Ford, B.; Kuo, S.H.; Mazzoni, P.; Pauciulo, M.W.; Nichols, W.C.; Gan-Or, Z.; et al. Glucocerebrosidase activity in Parkinson’s disease with and without GBA mutations. Brain 2015, 138, 2648–2658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lesage, S.; Anheim, M.; Condroyer, C.; Pollak, P.; Durif, F.; Dupuits, C.; Viallet, F.; Lohmann, E.; Corvol, J.C.; Honoré, A.; et al. Large-scale screening of the Gaucher’s disease-related glucocerebrosidase gene in Europeans with Parkinson’s disease. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2011, 20, 202–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Sun, Q.Y.; Zhao, Y.W.; Shu, L.; Guo, J.F.; Xu, Q.; Yan, X.X.; Tang, B.S. Effect of GBA mutations on phenotype of Parkinson’s disease: A study on Chinese population and a meta-analysis. Parkinsons Dis. 2015, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kasten, M.; Hartmann, C.; Hampf, J.; Schaake, S.; Westenberger, A.; Vollstedt, E.J.; Balck, A.; Domingo, A.; Vulinovic, F.; Dulovic, M.; et al. Genotype-Phenotype Relations for the Parkinson’s Disease Genes Parkin, PINK1, DJ1: MDSGene Systematic Review. Mov. Disord. 2018, 33, 730–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, N.L.; Graham, E.; Critchley, P.; Schrag, A.E.; Wood, N.W.; Lees, A.J.; Bhatia, K.P.; Quinn, N. Parkin disease: A phenotypic study of a large case series. Brain 2003, 126, 1279–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benamer, H.T.S.; De Silva, R. LRRK2 G2019S in the North African population: A review. Eur. Neurol. 2010, 63, 321–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Chen, Y.; Pu, J. Leucine-Rich Repeat Kinase 2 in Parkinson’s Disease: Updated from Pathogenesis to Potential Therapeutic Target. Eur. Neurol. 2018, 79, 256–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yue, Z. LRRK2 in Parkinson’s disease: In vivo models and approaches for understanding pathogenic roles. FEBS J. 2009, 276, 6445–6454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alkanli, N.; Ay, A. The Relationship between Alpha-Synuclein (SNCA) Gene Polymorphisms and Development Risk of Parkinson’s Disease. In Synucleins—Biochemistry and Role in Diseases; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Gao, G.; Duan, C.; Yang, H. Progress of immunotherapy of anti-α-synuclein in Parkinson’s disease. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 115, 108843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.Y.; Xie, C.L.; Zhang, S.F.; Yuan, W.; Liu, Z.G. Current experimental studies of gene therapy in Parkinson’s disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2017, 9, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Riboldi, G.M.; Di Fonzo, A.B. GBA, Gaucher Disease, and Parkinson’s Disease: From Genetic to Clinic to New Therapeutic Approaches. Cells 2019, 8, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sidransky, E.; Lopez, G. The link between the GBA gene and parkinsonism. Lancet Neurol. 2012, 11, 986–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Avenali, M.; Blandini, F.; Cerri, S. Glucocerebrosidase Defects as a Major Risk Factor for Parkinson’s Disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2020, 12, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sassone, J.; Valtorta, F.; Ciammola, A. Early Dyskinesias in Parkinson’s Disease Patients With Parkin Mutation: A Primary Corticostriatal Synaptopathy? Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuhl McGuire, M. Next in Line for Parkinson’s Therapies: PRKN and PINK1 Parkinson’s Disease. Available online: https://www.michaeljfox.org/news/next-line-parkinsons-therapies-prkn-and-pink1 (accessed on 20 May 2020).

- Rahman, A.A.; Morrison, B.E. Contributions of VPS35 Mutations to Parkinson’s Disease. Neuroscience 2019, 401, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).