DNA Damage-Induced Neurodegeneration in Accelerated Ageing and Alzheimer’s Disease

Abstract

:1. An Overview of DNA Damage and DNA Damage Response (DDR)

1.1. DNA Damage and DDR

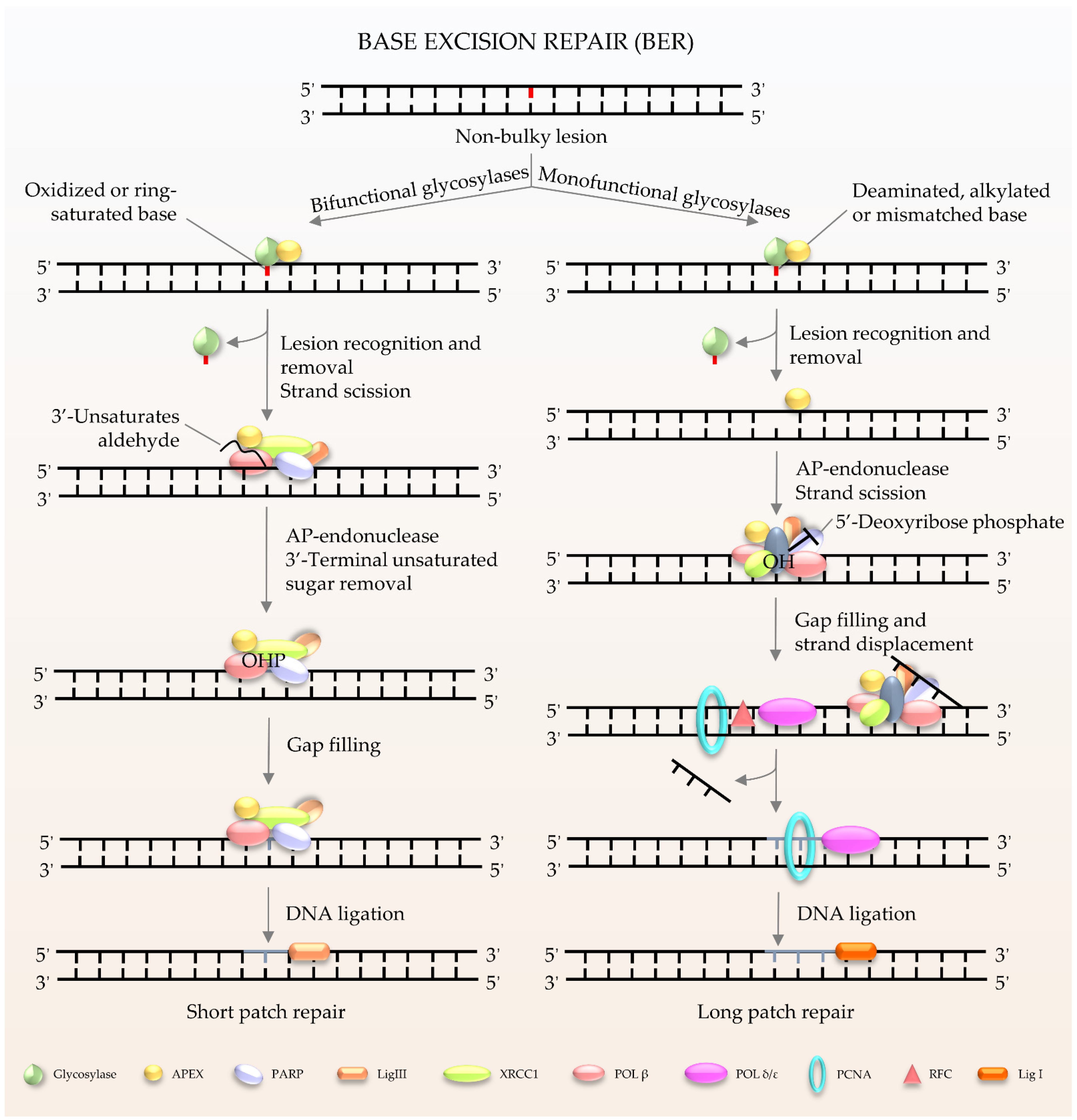

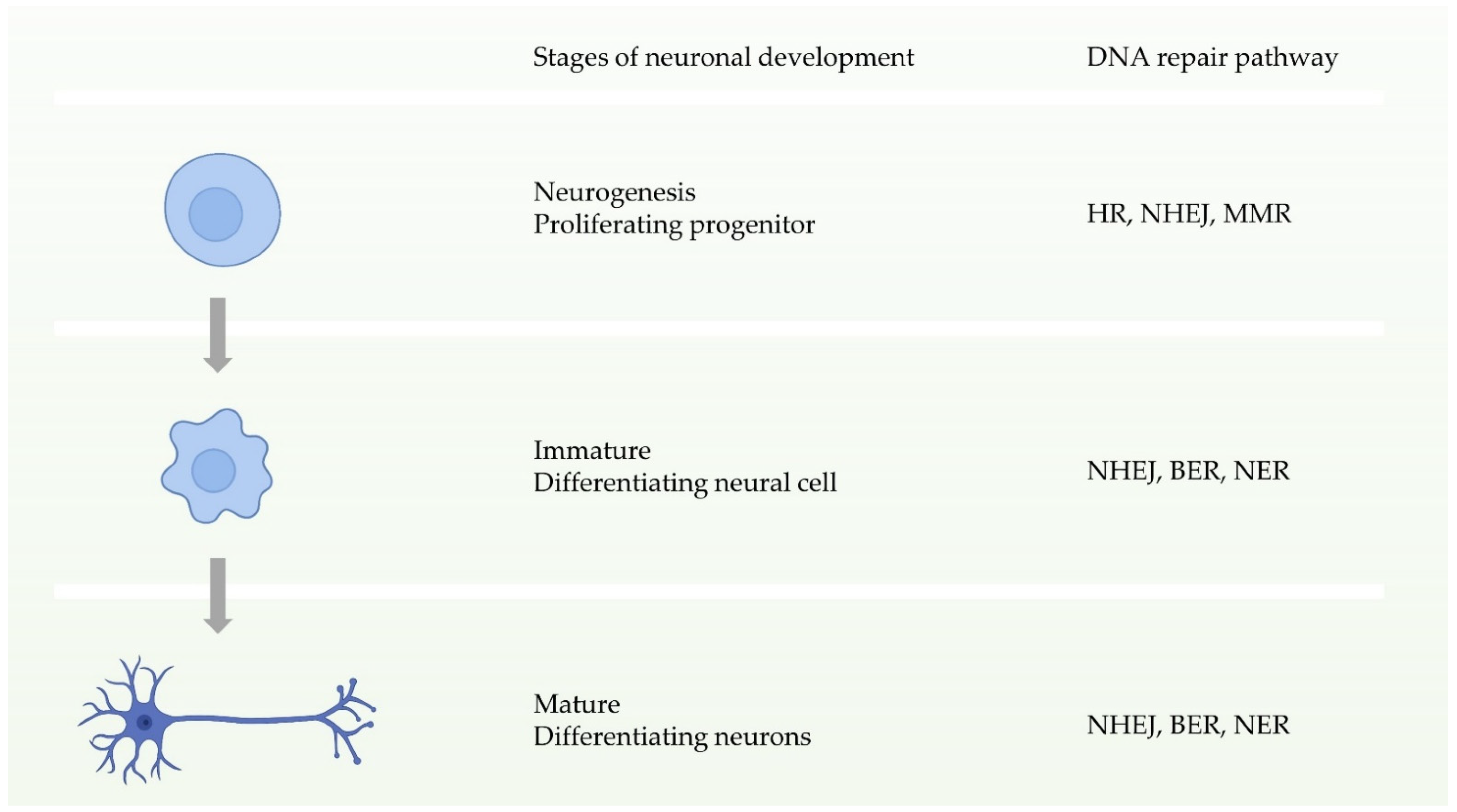

1.2. Major DNA Repair Pathways and Their Roles in Neurons and Microglia

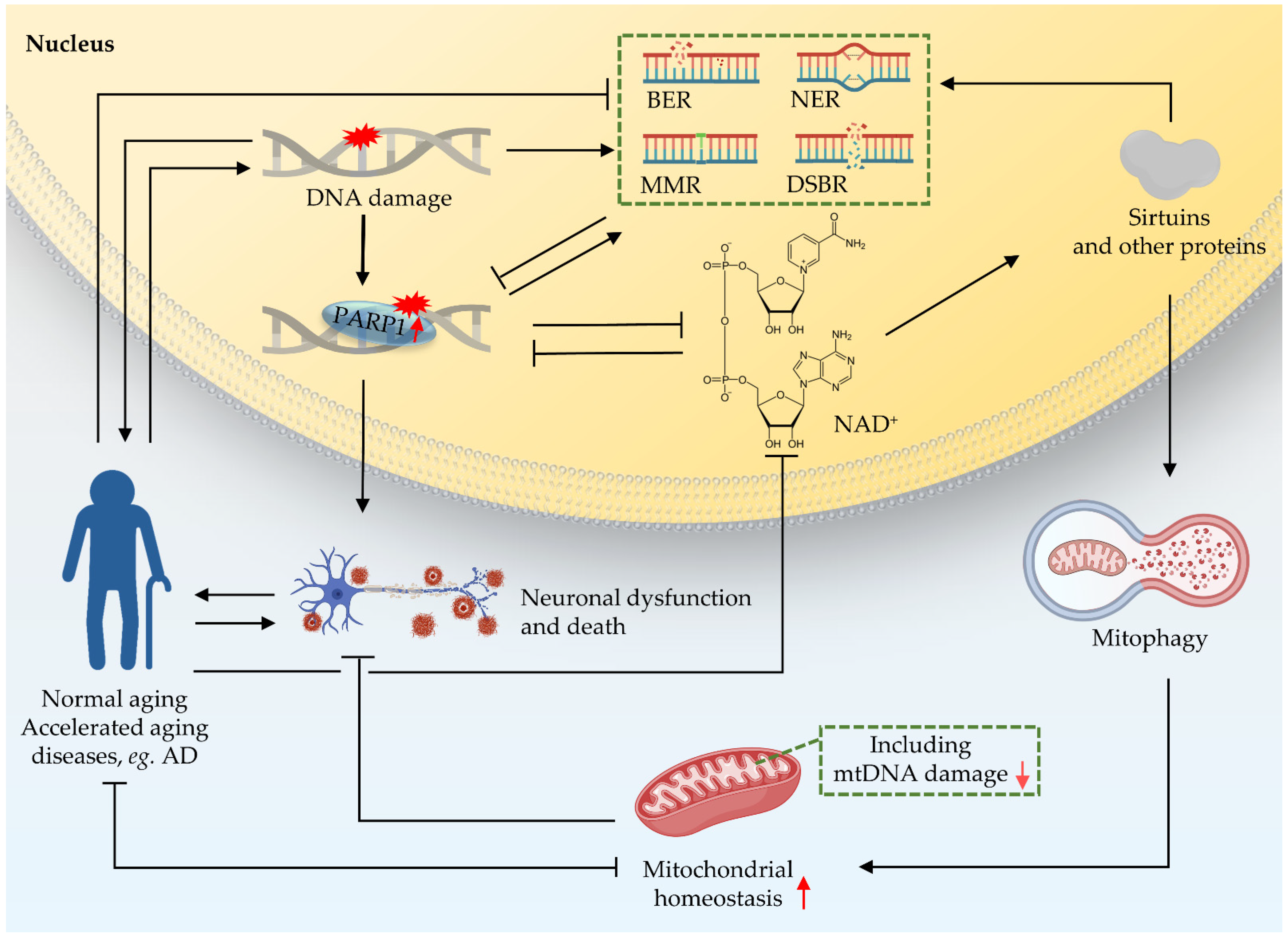

2. Crosstalk between Nucleus and Mitochondria in DNA Damage

3. Impairment of the NAD+-Mitophagy Axis Is a Shared Mechanism in DNA Damage-Induced Accelerated Ageing Diseases and in AD

3.1. XPA

3.2. CS

3.3. A-T

3.4. WS

3.5. AD

4. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chatterjee, N.; Walker, G.C. Mechanisms of DNA damage, repair, and mutagenesis. Environ. Mol. Mutagen. 2017, 58, 235–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tiwari, V.; Wilson, D.M., 3rd. DNA Damage and Associated DNA Repair Defects in Disease and Premature Aging. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2019, 105, 237–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tubbs, A.; Nussenzweig, A. Endogenous DNA Damage as a Source of Genomic Instability in Cancer. Cell 2017, 168, 644–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Carusillo, A.; Mussolino, C. DNA Damage: From Threat to Treatment. Cells 2020, 9, 1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, S.P.; Bartek, J. The DNA-damage response in human biology and disease. Nat. Cell Biol. 2009, 461, 1071–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lindahl, T.; Barnes, D.E. Repair of Endogenous DNA Damage. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 2000, 65, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, E.F.; Scheibye-Knudsen, M.; Chua, K.F.; Mattson, M.P.; Croteau, D.L.; Bohr, V.A. Nuclear DNA damage signalling to mitochondria in ageing. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2016, 17, 308–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kunkel, T.A. Celebrating DNA’s Repair Crew. Cell 2015, 163, 1301–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lindahl, T. Instability and decay of the primary structure of DNA. Nat. Cell Biol. 1993, 362, 709–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.-H.; Kang, T.-H. DNA Oxidation and Excision Repair Pathways. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 6092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Madabhushi, R.; Pan, L.; Tsai, L.-H. DNA Damage and Its Links to Neurodegeneration. Neuron 2014, 83, 266–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mullins, E.A.; Rodriguez, A.A.; Bradley, N.P.; Eichman, B.F. Emerging Roles of DNA Glycosylases and the Base Excision Repair Pathway. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2019, 44, 765–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Yang, X.; Lu, X.; Dai, N.; Zhang, S.; Cheng, Y.; Zhang, L.; Yang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Yang, Z.; et al. APE1 deficiency promotes cellular senescence and premature aging features. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, 5664–5677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calafiore, M.; Copani, A.; Deng, W. DNA polymerase-beta mediates the neurogenic effect of beta-amyloid protein in cultured subventricular zone neurospheres. J. Neurosci. Res. 2012, 90, 559–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Prakash, A.; Doublie, S. Base Excision Repair in the Mitochondria. J. Cell. Biochem. 2015, 116, 1490–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sharma, P.; Sampath, H. Mitochondrial DNA Integrity: Role in Health and Disease. Cells 2019, 8, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Boguszewska, K.; Szewczuk, M.; Kaźmierczak-Barańska, J.; Karwowski, B.T. The Similarities between Human Mitochondria and Bacteria in the Context of Structure, Genome, and Base Excision Repair System. Molecules 2020, 25, 2857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillet, L.C.; Scharer, O.D. Molecular mechanisms of mammalian global genome nucleotide excision repair. Chem. Rev. 2006, 106, 253–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schärer, O.D. Nucleotide Excision Repair in Eukaryotes. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2013, 5, a012609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topolska-Woś, A.M.; Sugitani, N.; Cordoba, J.J.; Le Meur, K.V.; Le Meur, R.A.A.; Kim, H.S.; Yeo, J.-E.; Rosenberg, D.; Hammel, M.; Schärer, O.D.; et al. A key interaction with RPA orients XPA in NER complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, 2173–2188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Marteijn, J.A.; Lans, H.; Vermeulen, W.; Hoeijmakers, J.H. Understanding nucleotide excision repair and its roles in cancer and ageing. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2014, 15, 465–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fousteri, M.; Mullenders, L.H. Transcription-coupled nucleotide excision repair in mammalian cells: Molecular mechanisms and biological effects. Cell Res. 2008, 18, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bohr, V.A.; Smith, C.A.; Okumoto, D.S.; Hanawalt, P.C. DNA repair in an active gene: Removal of pyrimidine dimers from the DHFR gene of CHO cells is much more efficient than in the genome overall. Cell 1985, 40, 359–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riedl, T.; Hanaoka, F.; Egly, J.M. The comings and goings of nucleotide excision repair factors on damaged DNA. EMBO J. 2003, 22, 5293–5303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Petruseva, I.O.; Evdokimov, A.N.; Lavrik, O.I. Molecular Mechanism of Global Genome Nucleotide Excision Repair. Acta Naturae 2014, 6, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kokic, G.; Chernev, A.; Tegunov, D.; Dienemann, C.; Urlaub, H.; Cramer, P. Structural basis of TFIIH activation for nucleotide excision repair. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 2885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jackson, S.P. Sensing and repairing DNA double-strand breaks. Carcinogenesis 2002, 23, 687–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaniecki, K.; De Tullio, L.; Greene, E.C. A change of view: Homologous recombination at single-molecule resolution. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2018, 19, 191–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, W.D.; Shah, S.S.; Heyer, W.-D. Homologous recombination and the repair of DNA double-strand breaks. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 10524–10535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Piazza, A.; Heyer, W.-D. Homologous Recombination and the Formation of Complex Genomic Rearrangements. Trends Cell Biol. 2019, 29, 135–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scully, R.; Panday, A.; Elango, R.; Willis, N.A. DNA double-strand break repair-pathway choice in somatic mammalian cells. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2019, 20, 698–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, B.; Rothenberg, E.; Ramsden, D.A.; Lieber, M.R. The molecular basis and disease relevance of non-homologous DNA end joining. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2020, 21, 765–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lieber, M.R.; Ma, Y.; Pannicke, U.; Schwarz, K. Mechanism and regulation of human non-homologous DNA end-joining. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2003, 4, 712–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falck, J.; Coates, J.; Jackson, S.P. Conserved modes of recruitment of ATM, ATR and DNA-PKcs to sites of DNA damage. Nat. Cell Biol. 2005, 434, 605–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyman, C.; Ristic, D.; Kanaar, R. Homologous recombination-mediated double-strand break repair. DNA Repair 2004, 3, 827–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty, A.J.; Jackson, S.P. DNA repair: How Ku makes ends meet. Curr. Biol. 2001, 11, R920–R924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xia, W.; Ci, S.; Li, M.; Wang, M.; Dianov, G.L.; Ma, Z.; Li, L.; Hua, K.; Alagamuthu, K.K.; Qing, L.; et al. Two-way crosstalk between BER and c-NHEJ repair pathway is mediated by Pol-beta and Ku70. FASEB J. 2019, 33, 11668–11681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brochier, C.; Langley, B. Chromatin Modifications Associated with DNA Double-strand Breaks Repair as Potential Targets for Neurological Diseases. Neurotherapeutics 2013, 10, 817–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, W.; Gu, X.; Zhang, X.; Kong, J.; Ding, N.; Qi, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Huang, D. Cadmium delays non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) repair via inhibition of DNA-PKcs phosphorylation and downregulation of XRCC4 and Ligase IV. Mutat. Res. Mol. Mech. Mutagen. 2015, 779, 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, L.; Feng, J.; Zuo, P.; Yang, J.; Lu, Y.; Yin, Y. Molecular basis for assembly of the shieldin complex and its implications for NHEJ. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerodimos, C.A.; Chang, H.H.Y.; Watanabe, G.; Lieber, M.R. Effects of DNA end configuration on XRCC4-DNA ligase IV and its stimulation of Artemis activity. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 13914–13924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hoeijmakers, J.H. DNA Damage, Aging, and Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 361, 1475–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.-H.; Yu, X. Human DNA ligase IV is able to use NAD+ as an alternative adenylation donor for DNA ends ligation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 47, 1321–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- McKinnon, P.J. Maintaining genome stability in the nervous system. Nat. Neurosci. 2013, 16, 1523–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chow, H.-M.; Herrup, K. Genomic integrity and the ageing brain. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2015, 16, 672–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Driscoll, M.; Cerosaletti, K.M.; Girard, P.-M.; Dai, Y.; Stumm, M.; Kysela, B.; Hirsch, B.; Gennery, A.; Palmer, S.E.; Seidel, J.; et al. DNA Ligase IV Mutations Identified in Patients Exhibiting Developmental Delay and Immunodeficiency. Mol. Cell 2001, 8, 1175–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodbine, L.; Neal, J.A.; Sasi, N.K.; Shimada, M.; Deem, K.; Coleman, H.; Dobyns, W.B.; Ogi, T.; Meek, K.; Davies, E.G.; et al. PRKDC mutations in a SCID patient with profound neurological abnormalities. J. Clin. Investig. 2013, 123, 2969–2980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldecott, K.W. Single-strand break repair and genetic disease. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2008, 9, 619–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakazawa, Y.; Hara, Y.; Oka, Y.; Komine, O.; van den Heuvel, D.; Guo, C.; Daigaku, Y.; Isono, M.; He, Y.; Shimada, M.; et al. Ubiquitination of DNA Damage-Stalled RNAPII Promotes Transcription-Coupled Repair. Cell 2020, 180, 1228–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Wu, Z.; Liu, L.; Liu, J.; Wang, Y. Rat Model of Cockayne Syndrome Neurological Disease. Cell Rep. 2019, 29, 800–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jones, L.; Houlden, H.; Tabrizi, S.J. DNA repair in the trinucleotide repeat disorders. Lancet Neurol. 2017, 16, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, G.T.; Kipnis, J. Immune cells and CNS physiology: Microglia and beyond. J. Exp. Med. 2018, 216, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, J.; Valin, K.L.; Dixon, M.L.; Leavenworth, J.W. The Role of Microglia and Macrophages in CNS Homeostasis, Autoimmunity, and Cancer. J. Immunol. Res. 2017, 2017, 5150678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mei, L.; Zhang, J.; He, K.; Zhang, J. Ataxia telangiectasia and Rad3-related inhibitors and cancer therapy: Where we stand. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2019, 12, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Ma, F.; Herrup, K. Accumulation of Cytoplasmic DNA Due to ATM Deficiency Activates the Microglial Viral Response System with Neurotoxic Consequences. J. Neurosci. 2019, 39, 6378–6394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Orelli, B.; McClendon, T.B.; Tsodikov, O.V.; Ellenberger, T.; Niedernhofer, L.J.; Schärer, O.D. The XPA-binding domain of ERCC1 Is Required for Nucleotide Excision Repair but Not Other DNA Repair Pathways. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 3705–3712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, X.; Heng, Y.; Kooistra, S.M.; Van Weering, H.R.J.; Brummer, M.L.; Gerrits, E.; Wesseling, E.M.; Brouwer, N.; Nijboer, T.W.; Dubbelaar, M.L.; et al. Intrinsic DNA damage repair deficiency results in progressive microglia loss and replacement. Glia 2021, 69, 729–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, M.; Reddy, P.H. Defective Autophagy and Mitophagy in Aging and Alzheimer’s Disease. Front. Neurosci. 2021, 14, 612757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, T.; Sadoshima, J. Molecular Mechanisms of Mitochondrial Autophagy/Mitophagy in the Heart. Circ. Res. 2015, 116, 1477–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Q.; Jeong, Y.Y. Mitophagy in Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Age-Related Neurodegenerative Diseases. Cells 2020, 9, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Babbar, M.; Basu, S.; Yang, B.; Croteau, D.L.; Bohr, V.A. Mitophagy and DNA damage signaling in human aging. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2020, 186, 111207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valentin-Vega, Y.A.; MacLean, K.H.; Tait-Mulder, J.; Milasta, S.; Steeves, M.; Dorsey, F.C.; Cleveland, J.L.; Green, D.; Kastan, M.B. Mitochondrial dysfunction in ataxia-telangiectasia. Blood 2012, 119, 1490–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fang, E.F.; Scheibye-Knudsen, M.; Brace, L.E.; Kassahun, H.; SenGupta, T.; Nilsen, H.; Mitchell, J.R.; Croteau, D.L.; Bohr, V.A. Defective Mitophagy in XPA via PARP-1 Hyperactivation and NAD+/SIRT1 Reduction. Cell 2014, 157, 882–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Shimizu, I.; Yoshida, Y.; Suda, M.; Minamino, T. DNA Damage Response and Metabolic Disease. Cell Metab. 2014, 20, 967–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ou, H.-L.; Schumacher, B. DNA damage responses and p53 in the aging process. Blood 2018, 131, 488–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Maiuri, T.; Suart, C.; Hung, C.L.-K.; Graham, K.; Bazan, C.A.B.; Truant, R. DNA Damage Repair in Huntington’s Disease and Other Neurodegenerative Diseases. Neurotherapeutics 2019, 16, 948–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.; Pan, Y.; Kao, S.-Y.; Li, C.; Kohane, I.; Chan, J.; Yankner, B.A. Gene regulation and DNA damage in the ageing human brain. Nat. Cell Biol. 2004, 429, 883–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, E.F.; Kassahun, H.; Croteau, D.L.; Scheibye-Knudsen, M.; Marosi, K.; Lu, H.; Shamanna, R.A.; Kalyanasundaram, S.; Bollineni, R.C.; Wilson, M.A.; et al. NAD + Replenishment Improves Lifespan and Healthspan in Ataxia Telangiectasia Models via Mitophagy and DNA Repair. Cell Metab. 2016, 24, 566–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shiloh, Y.; Lederman, H.M. Ataxia-telangiectasia (A-T): An emerging dimension of premature ageing. Ageing Res. Rev. 2017, 33, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lautrup, S.; Caponio, D.; Cheung, H.H.; Piccoli, C.; Stevnsner, T.; Chan, W.-Y.; Fang, E.F. Studying Werner syndrome to elucidate mechanisms and therapeutics of human aging and age-related diseases. Biogerontology 2019, 20, 255–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misiak, M.; Vergara Greeno, R.; Baptiste, B.A.; Sykora, P.; Liu, D.; Cordonnier, S.; Fang, E.F.; Croteau, D.L.; Mattson, M.P.; Bohr, V.A. DNA polymerase β decrement triggers death of olfactory bulb cells and impairs olfaction in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Aging Cell 2017, 16, 162–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sykora, P.; Misiak, M.; Wang, Y.; Ghosh, S.; Leandro, G.S.; Liu, D.; Tian, J.; Baptiste, B.A.; Cong, W.N.; Brenerman, B.M.; et al. DNA polymerase β deficiency leads to neurodegeneration and exacerbates Alzheimer disease phenotypes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, 943–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, J.; Baptiste, B.A.; Kim, E.; Hussain, M.; Croteau, D.L.; Bohr, V.A. DNA damage and mitochondria in cancer and aging. Carcinogenesis 2020, 41, 1625–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saki, M.; Prakash, A. DNA damage related crosstalk between the nucleus and mitochondria. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2017, 107, 216–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fivenson, E.M.; Lautrup, S.; Sun, N.; Scheibye-Knudsen, M.; Stevnsner, T.; Nilsen, H.; Bohr, V.A.; Fang, E.F. Mitophagy in neurodegeneration and aging. Neurochem. Int. 2017, 109, 202–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sas, K.; Szabó, E.; Vécsei, L. Mitochondria, Oxidative Stress and the Kynurenine System, with a Focus on Ageing and Neuroprotection. Molecules 2018, 23, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Xu, C.; Wang, L.; Fozouni, P.; Evjen, G.; Chandra, V.; Jiang, J.; Lu, C.; Nicastri, M.; Bretz, C.; Winkler, J.D.; et al. SIRT1 is downregulated by autophagy in senescence and ageing. Nat. Cell Biol. 2020, 22, 1170–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, J.; Hong, T.; Chen, X.; Cui, L. SIRT2: Controversy and multiple roles in disease and physiology. Ageing Res. Rev. 2019, 55, 100961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dikalova, A.E.; Pandey, A.; Xiao, L.; Arslanbaeva, L.; Sidorova, T.; Lopez, M.G.; Iv, F.T.B.; Verdin, E.; Auwerx, J.; Harrison, D.G.; et al. Mitochondrial Deacetylase Sirt3 Reduces Vascular Dysfunction and Hypertension While Sirt3 Depletion in Essential Hypertension Is Linked to Vascular Inflammation and Oxidative Stress. Circ. Res. 2020, 126, 439–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, T.; Cao, Y.; Zheng, Q.; Tu, J.; Zhou, W.; He, J.; Zhong, J.; Chen, Y.; Wang, J.; Cai, R.; et al. SENP1-Sirt3 Signaling Controls Mitochondrial Protein Acetylation and Metabolism. Mol. Cell 2019, 75, 823–834.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouchiroud, L.; Houtkooper, R.H.; Moullan, N.; Katsyuba, E.; Ryu, D.; Cantó, C.; Mottis, A.; Jo, Y.S.; Viswanathan, M.; Schoonjans, K.; et al. The NAD+/Sirtuin Pathway Modulates Longevity through Activation of Mitochondrial UPR and FOXO Signaling. Cell 2013, 154, 430–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lehmann, J.; Seebode, C.; Martens, M.C.; Emmert, S. Xeroderma Pigmentosum—Facts and Perspectives. Anticancer Res. 2018, 38, 1159–1164. [Google Scholar]

- DiGiovanna, J.J.; Kraemer, K.H. Shining a Light on Xeroderma Pigmentosum. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2012, 132, 785–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Uribe-Bojanini, E.; Hernandez-Quiceno, S.; Cock-Rada, A.M. Xeroderma Pigmentosum with Severe Neurological Manifestations/De Sanctis–Cacchione Syndrome and a Novel XPC Mutation. Case Rep. Med. 2017, 2017, 7162737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abeti, R.; Zeitlberger, A.; Peelo, C.; Fassihi, H.; Sarkany, R.P.E.; Lehmann, A.R.; Giunti, P. Xeroderma pigmentosum: Overview of pharmacology and novel therapeutic strategies for neurological symptoms. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2019, 176, 4293–4301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rass, U.; Ahel, I.; West, S.C. Defective DNA Repair and Neurodegenerative Disease. Cell 2007, 130, 991–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fassihi, H.; Sethi, M.; Fawcett, H.; Wing, J.; Chandler, N.; Mohammed, S.; Craythorne, E.; Morley, A.M.S.; Lim, R.; Turner, S.; et al. Deep phenotyping of 89 xeroderma pigmentosum patients reveals unexpected heterogeneity dependent on the precise molecular defect. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, E1236–E1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cleaver, J.E. Defective Repair Replication of DNA in Xeroderma Pigmentosum. Nat. Cell Biol. 1968, 218, 652–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugasawa, K.; Akagi, J.-I.; Nishi, R.; Iwai, S.; Hanaoka, F. Two-Step Recognition of DNA Damage for Mammalian Nucleotide Excision Repair: Directional Binding of the XPC Complex and DNA Strand Scanning. Mol. Cell 2009, 36, 642–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabatella, M.; Pines, A.; Slyskova, J.; Vermeulen, W.; Lans, H. ERCC1-XPF targeting to psoralen-DNA crosslinks depends on XPA and FANCD2. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2020, 77, 2005–2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sugitani, N.; Sivley, R.M.; Perry, K.E.; Capra, J.A.; Chazin, W.J. XPA: A key scaffold for human nucleotide excision repair. DNA Repair 2016, 44, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, L.; Elledge, S.J.; Peterson, C.A.; Bales, E.S.; Legerski, R.J. Specific association between the human DNA repair proteins XPA and ERCC1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1994, 91, 5012–5016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tsodikov, O.V.; Ivanov, D.; Orelli, B.; Staresincic, L.; Shoshani, I.; Oberman, R.; Schärer, O.D.; Wagner, G.; Ellenberger, T. Structural basis for the recruitment of ERCC1-XPF to nucleotide excision repair complexes by XPA. EMBO J. 2007, 26, 4768–4776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Volker, M.; Moné, M.J.; Karmakar, P.; van Hoffen, A.; Schul, W.; Vermeulen, W.; Hoeijmakers, J.H.; van Driel, R.; van Zeeland, A.A.; Mullenders, L.H. Sequential Assembly of the Nucleotide Excision Repair Factors In Vivo. Mol. Cell 2001, 8, 213–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Liu, W.; Doycheva, D.M.; Gamdzyk, M.; Lu, W.; Tang, J.; Zhang, J.H. Ghrelin attenuates oxidative stress and neuronal apoptosis via GHSR-1α/AMPK/Sirt1/PGC-1α/UCP2 pathway in a rat model of neonatal HIE. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2019, 141, 322–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, G.; Xiao, L.; Wang, D.; Wang, N.; Luo, C.; Yang, X.; Hao, L. Resveratrol protects against ethanol-induced impairment of insulin secretion in INS-1 cells through SIRT1-UCP2 axis. Toxicol. In Vitro 2020, 65, 104808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagouge, M.; Argmann, C.; Gerhart-Hines, Z.; Meziane, H.; Lerin, C.; Daussin, F.; Messadeq, N.; Milne, J.; Lambert, P.; Elliott, P.; et al. Resveratrol improves mitochondrial function and protects against metabolic disease by activating SIRT1 and PGC-1α. Cell 2006, 127, 1109–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St-Pierre, J.; Drori, S.; Uldry, M.; Silvaggi, J.M.; Rhee, J.; Jager, S.; Handschin, C.; Zheng, K.; Lin, J.; Yang, W.; et al. Suppression of Reactive Oxygen Species and Neurodegeneration by the PGC-1 Transcriptional Coactivators. Cell 2006, 127, 397–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alano, C.C.; Garnier, P.; Ying, W.; Higashi, Y.; Kauppinen, T.M.; Swanson, R. NAD+ Depletion Is Necessary and Sufficient forPoly(ADP-Ribose) Polymerase-1-Mediated Neuronal Death. J. Neurosci. 2010, 30, 2967–2978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manandhar, M.; Lowery, M.G.; Boulware, K.S.; Lin, K.H.; Lu, Y.; Wood, R.D. Transcriptional consequences of XPA disruption in human cell lines. DNA Repair 2017, 57, 76–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheibye-Knudsen, M.; Fang, E.F.; Croteau, D.L.; Bohr, V.A. Contribution of defective mitophagy to the neurodegeneration in DNA repair-deficient disorders. Autophagy 2014, 10, 1468–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nance, M.A.; Berry, S.A. Cockayne syndrome: Review of 140 cases. Am. J. Med Genet. 1992, 42, 68–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraemer, K.H.; Patronas, N.J.; Schiffmann, R.; Brooks, B.P.; Tamura, D.; DiGiovanna, J.J. Xeroderma pigmentosum, trichothiodystrophy and Cockayne syndrome: A complex genotype–phenotype relationship. Neuroscience 2007, 145, 1388–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stevnsner, T.; Nyaga, S.; De Souza-Pinto, N.C.; Van Der Horst, G.T.J.; Gorgels, T.G.M.F.; Hogue, B.A.; Thorslund, T.; Bohr, V.A. Mitochondrial repair of 8-oxoguanine is deficient in Cockayne syndrome group B. Oncogene 2002, 21, 8675–8682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shemen, L.J.; Mitchell, D.P.; Farkashidy, J. Cockayne syndrome—An audiologic and temporal bone analysis. Am. J. Otol. 1984, 5, 300–307. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, B.T.; Stark, Z.; Sutton, R.E.; Danda, S.; Ekbote, A.V.; Elsayed, S.M.; Gibson, L.; Goodship, J.A.; Jackson, A.P.; Keng, W.T.; et al. The Cockayne Syndrome Natural History (CoSyNH) study: Clinical findings in 102 individuals and recommendations for care. Genet. Med. 2015, 18, 483–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Okur, M.N.; Mao, B.; Kimura, R.; Haraczy, S.; Fitzgerald, T.; Edwards-Hollingsworth, K.; Tian, J.; Osmani, W.; Croteau, D.L.; Kelley, M.W.; et al. Short-term NAD+ supplementation prevents hearing loss in mouse models of Cockayne syndrome. NPJ Aging Mech. Dis. 2020, 6, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aamann, M.D.; Sorensen, M.M.; Hvitby, C.; Berquist, B.R.; Muftuoglu, M.; Tian, J.; de Souza-Pinto, N.C.; Scheibye-Knudsen, M.; Wilson, D.M., 3rd; Stevnsner, T.; et al. Cockayne syndrome group B protein promotes mitochondrial DNA stability by supporting the DNA repair association with the mitochondrial membrane. FASEB J. 2010, 24, 2334–2346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pascucci, B.; Lemma, T.; Iorio, E.; Giovannini, S.; Vaz, B.; Iavarone, I.; Calcagnile, A.; Narciso, L.; Degan, P.; Podo, F.; et al. An altered redox balance mediates the hypersensitivity of Cockayne syndrome primary fibroblasts to oxidative stress. Aging Cell 2012, 11, 520–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheibye-Knudsen, M.; Mitchell, S.J.; Fang, E.F.; Iyama, T.; Ward, T.; Wang, J.; Dunn, C.A.; Singh, N.; Veith, S.; Hasan-Olive, M.M.; et al. A high-fat diet and NAD+ activate Sirt1 to rescue premature aging in cockayne syndrome. Cell Metab. 2014, 20, 840–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Scheibye-Knudsen, M.; Tseng, A.; Borch Jensen, M.; Scheibye-Alsing, K.; Fang, E.F.; Iyama, T.; Bharti, S.K.; Marosi, K.; Froetscher, L.; Kassahun, H.; et al. Cockayne syndrome group A and B proteins converge on transcription-linked resolution of non-B DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 12502–12507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Okur, M.N.; Fang, E.F.; Fivenson, E.M.; Tiwari, V.; Croteau, D.L.; Bohr, V.A. Cockayne syndrome proteins CSA and CSB maintain mitochondrial homeostasis through NAD+ signaling. Aging Cell 2020, 19, e13268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choy, K.R.; Watters, D.J. Neurodegeneration in ataxia-telangiectasia: Multiple roles of ATM kinase in cellular homeostasis. Dev. Dyn. 2018, 247, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Amirifar, P.; Ranjouri, M.R.; Yazdani, R.; Abolhassani, H.; Aghamohammadi, A. Ataxia-telangiectasia: A review of clinical features and molecular pathology. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2019, 30, 277–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, A.; Lang, A.E. Ataxia-telangiectasia: A review of movement disorders, clinical features, and genotype correlations. Mov. Disord. 2018, 33, 1238–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schon, K.; Van Os, N.J.; Oscroft, N.; Baxendale, H.; Scoffings, D.; Ray, J.; Suri, M.; Whitehouse, W.P.; Mehta, P.; Everett, N.; et al. Genotype, extrapyramidal features and severity of variant Ataxia-Telangiectasia. Ann. Neurol. 2018, 85, 170–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Os NJ, H.; Jansen AF, M.; van Deuren, M.; Haraldsson, A.; van Driel NT, M.; Etzioni, A.; van der Flier, M.; Haaxma, C.A.; Morio, T.; Rawat, A.; et al. Ataxia-telangiectasia: Immunodeficiency and survival. Clin. Immunol. 2017, 178, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakad, R.; Schumacher, B. DNA Damage Response and Immune Defense: Links and Mechanisms. Front. Genet. 2016, 7, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nastasi, C.; Mannarino, L.; D’Incalci, M. DNA Damage Response and Immune Defense. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKnight, K.L.; Swanson, K.V.; Austgen, K.; Richards, C.; Mitchell, J.K.; McGivern, D.R.; Fritch, E.; Johnson, J.; Remlinger, K.; Magid-Slav, M.; et al. Stimulator of interferon genes (STING) is an essential proviral host factor for human rhinovirus species A and C. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 27598–27607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, C.E.; Oshima, J.; Fu, Y.H.; Wijsman, E.M.; Hisama, F.; Alisch, R.; Matthews, S.; Nakura, J.; Miki, T.; Ouais, S.; et al. Positional cloning of the Werner’s syndrome gene. Science 1996, 272, 258–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bohr, V.A. Rising from the RecQ-age: The role of human RecQ helicases in genome maintenance. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2008, 33, 609–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Larsen, N.B.; Hickson, I.D. RecQ Helicases: Conserved Guardians of Genomic Integrity. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2012, 767, 161–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croteau, D.L.; Popuri, V.; Opresko, P.L.; Bohr, V.A. Human RecQ Helicases in DNA Repair, Recombination, and Replication. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2014, 83, 519–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huang, S.; Li, B.; Gray, M.D.; Oshima, J.; Mian, I.S.; Campisi, J. The premature ageing syndrome protein, WRN, is a 3′→5′ exonuclease. Nat. Genet. 1998, 20, 114–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, E.F.; Hou, Y.; Lautrup, S.; Jensen, M.B.; Yang, B.; Sengupta, T.; Caponio, D.; Khezri, R.; Demarest, T.G.; Aman, Y.; et al. NAD+ augmentation restores mitophagy and limits accelerated aging in Werner syndrome. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 5284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Oshima, J.; Sidorova, J.; Monnat, R.J. Werner syndrome: Clinical features, pathogenesis and potential therapeutic interventions. Ageing Res. Rev. 2017, 33, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Oshima, J.; Martin, G.M.; Hisama, F.M. Werner Syndrome. In GeneReviews(®); Adam, M.P., Ardinger, H.H., Pagon, R.A., Wallace, S.E., Bean, L.J.H., Stephens, K., Amemiya, A., Eds.; University of Washington: Seattle, WA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Takemoto, M.; Mori, S.; Kuzuya, M.; Yoshimoto, S.; Shimamoto, A.; Igarashi, M.; Tanaka, Y.; Miki, T.; Yokote, K. Diagnostic criteria for Werner syndrome based on Japanese nationwide epidemiological survey. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2013, 13, 475–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, E.F.; Hou, Y.; Palikaras, K.; Adriaanse, B.A.; Kerr, J.S.; Yang, B.; Lautrup, S.; Hasan-Olive, M.; Caponio, D.; Dan, X.; et al. Mitophagy inhibits amyloid-β and tau pathology and reverses cognitive deficits in models of Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Neurosci. 2019, 22, 401–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N.K.; Lebedeva, M.; Thomas, T.; Kovalenko, O.A.; Stumpf, J.D.; Shadel, G.S.; Santos, J.H. Intrinsic mitochondrial DNA repair defects in Ataxia Telangiectasia. DNA Repair 2014, 13, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumpter, R., Jr.; Sirasanagandla, S.; Fernández, Á.F.; Wei, Y.; Dong, X.; Franco, L.; Zou, Z.; Marchal, C.; Lee, M.Y.; Clapp, D.W.; et al. Fanconi Anemia Proteins Function in Mitophagy and Immunity. Cell 2016, 165, 867–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, X.; Fang, E.F.; Scheibye-Knudsen, M.; Cui, H.; Qiu, L.; Li, J.; He, Y.; Huang, J.; Bohr, V.A.; Ng, T.B.; et al. Di-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate inhibits DNA replication leading to hyperPARylation, SIRT1 attenuation and mitochondrial dysfunction in the testis. Sci. Rep. 2015, 4, 6434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Livingston, G.; Huntley, J.; Sommerlad, A.; Ames, D.; Ballard, C.; Banerjee, S.; Brayne, C.; Burns, A.; Cohen-Mansfield, J.; Cooper, C.; et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 Report of the Lancet Commission. Lancet 2020, 396, 413–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Götz, J.; Ittner, A.; Ittner, L.M. Tau-targeted treatment strategies in Alzheimer’s disease. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2012, 165, 1246–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Iqbal, K.; Liu, F.; Gong, C.-X. Tau and neurodegenerative disease: The story so far. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2016, 12, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Song, H.; Croteau, D.L.; Akbari, M.; Bohr, V.A. Genome instability in Alzheimer disease. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2017, 161, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Weissman, L.; de Souza-Pinto, N.C.; Mattson, M.P.; Bohr, V.A. DNA base excision repair activities in mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging 2009, 30, 2080–2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Weissman, L.; Jo, D.G.; Sørensen, M.M.; de Souza-Pinto, N.C.; Markesbery, W.R.; Mattson, M.P.; Bohr, V.A. Defective DNA base excision repair in brain from individuals with Alzheimer’s disease and amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35, 5545–5555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovell, M.A.; Markesbery, W.R. Oxidative DNA damage in mild cognitive impairment and late-stage Alzheimer’s disease. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35, 7497–7504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, J.; Markesbery, W.R.; Lovell, M.A. Increased oxidative damage in nuclear and mitochondrial DNA in mild cognitive impairment. J. Neurochem. 2006, 96, 825–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovell, M.A.; Xie, C.; Markesbery, W.R. Decreased base excision repair and increased helicase activity in Alzheimer’s disease brain. Brain Res. 2000, 855, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canugovi, C.; Misiak, M.; Ferrarelli, L.K.; Croteau, D.L.; Bohr, V.A. The role of DNA repair in brain related disease pathology. DNA Repair 2013, 12, 578–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sykora, P.; Wilson, D.M., 3rd; Bohr, V.A. Base excision repair in the mammalian brain: Implication for age related neurodegeneration. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2013, 134, 440–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hou, Y.; Lautrup, S.; Cordonnier, S.; Wang, Y.; Croteau, D.L.; Zavala, E.; Zhang, Y.; Moritoh, K.; O’Connell, J.F.; Baptiste, B.A.; et al. NAD+ supplementation normalizes key Alzheimer’s features and DNA damage responses in a new AD mouse model with introduced DNA repair deficiency. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E1876–E1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kerr, J.S.; Adriaanse, B.A.; Greig, N.H.; Mattson, M.P.; Cader, M.Z.; Bohr, V.A.; Fang, E.F. Mitophagy and Alzheimer’s Disease: Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms. Trends Neurosci. 2017, 40, 151–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lautrup, S.; Sinclair, D.A.; Mattson, M.P.; Fang, E.F. NAD+ in Brain Aging and Neurodegenerative Disorders. Cell Metab. 2019, 30, 630–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, B.; Pan, Y.; Vempati, P.; Zhao, W.; Knable, L.; Ho, L.; Wang, J.; Sastre, M.; Ono, K.; Sauve, A.A.; et al. Nicotinamide riboside restores cognition through an upregulation of proliferator-activated receptor-gamma coactivator 1alpha regulated beta-secretase 1 degradation and mitochondrial gene expression in Alzheimer’s mouse models. Neurobiol. Aging 2013, 34, 1581–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, H.; Lautrup, S.; Caponio, D.; Zhang, J.; Fang, E.F. DNA Damage-Induced Neurodegeneration in Accelerated Ageing and Alzheimer’s Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6748. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22136748

Wang H, Lautrup S, Caponio D, Zhang J, Fang EF. DNA Damage-Induced Neurodegeneration in Accelerated Ageing and Alzheimer’s Disease. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2021; 22(13):6748. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22136748

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Heling, Sofie Lautrup, Domenica Caponio, Jianying Zhang, and Evandro F. Fang. 2021. "DNA Damage-Induced Neurodegeneration in Accelerated Ageing and Alzheimer’s Disease" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 22, no. 13: 6748. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22136748

APA StyleWang, H., Lautrup, S., Caponio, D., Zhang, J., & Fang, E. F. (2021). DNA Damage-Induced Neurodegeneration in Accelerated Ageing and Alzheimer’s Disease. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 22(13), 6748. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22136748