Alzheimer’s Disease and Specialized Pro-Resolving Lipid Mediators: Do MaR1, RvD1, and NPD1 Show Promise for Prevention and Treatment?

Abstract

1. Introduction

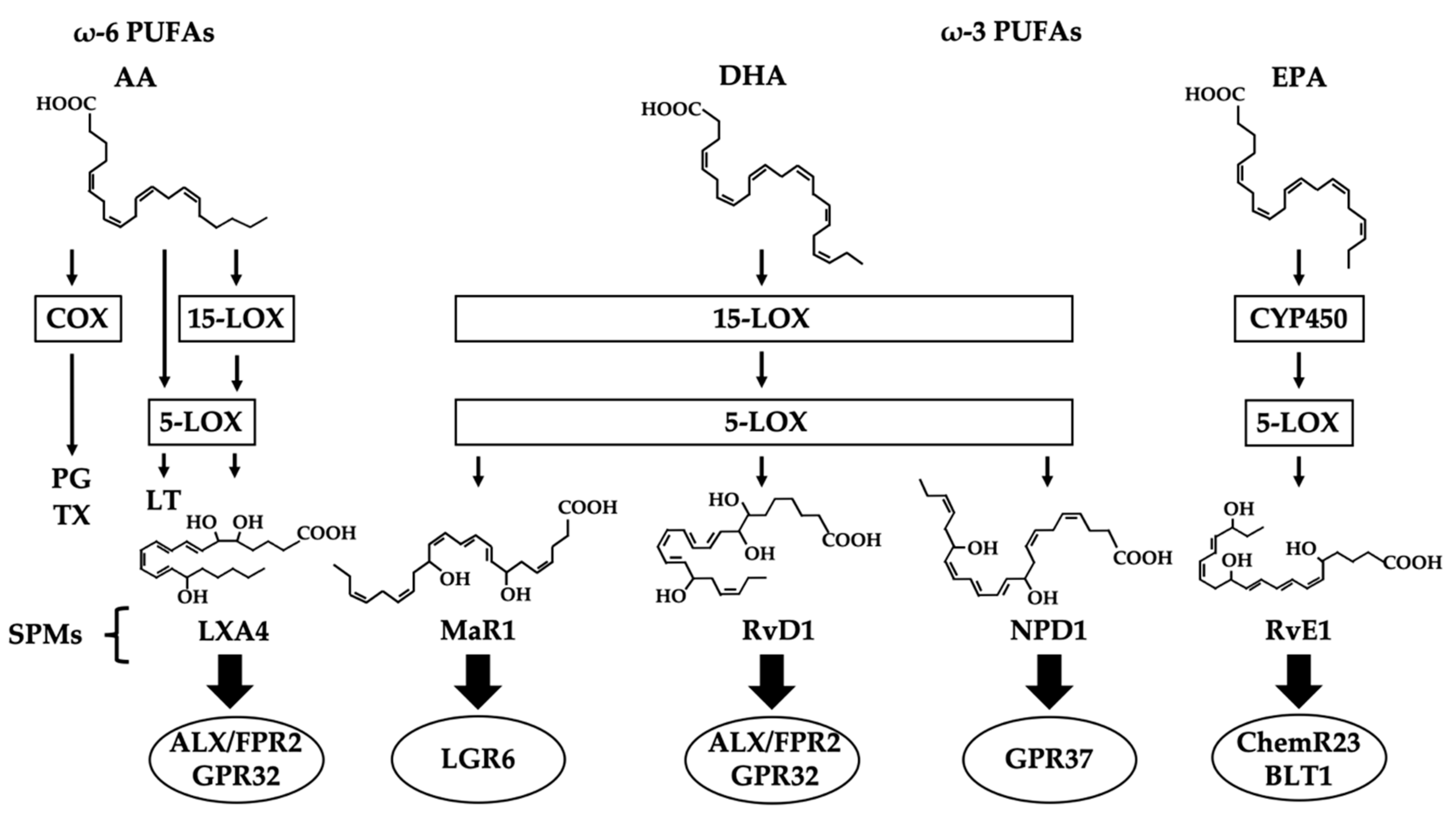

2. SPMs (Specialized Pro-resolving Lipid Mediators)

3. MaR1 (Maresin 1)

4. RvD1 (Resolvin D1)

5. NPD1 (Neuroprotection D1)

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AA | Arachidonic acid |

| AD | Alzheimer’s disease |

| ALX/FPR | Lipoxin A4/formyl peptide receptor |

| APP | Amyloid precursor protein |

| Aβ | Amyloid-beta |

| BBB | Blood-brain barrier |

| BLT | Leukotriene B4 receptor |

| ChemR | Chemerin receptor |

| CNS | Central nervous system |

| COX | Cyclooxygenase |

| CSF | Cerebrospinal fluid |

| DHA | docosahexaenoic |

| EPA | eicosapenraenoic |

| GPCR | G protein-coupled receptor |

| GPR | G protein receptor |

| LGR | Leucine-rich repeat containing G protein-coupled receptor |

| LT | Leukotriene |

| LOX | Lipoxygenase |

| LXA4 | Lipoxin A4 |

| MaR1 | Maresin 1 |

| MCI | Mild cognitive impairment |

| MMSE | Mini-Mental State Examination |

| MRI | Magnetic resonance imaging |

| NMDA | N-methyl-D-aspartate |

| NPD1 | Neuroprotectin D1 |

| NSAIDs | Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs |

| PET | Positron emission tomography |

| PG | Prostaglandin |

| PPAR | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor |

| PUFA | Polyunsaturated fatty acid |

| RORα | Retinoic acid-related orphan receptor α |

| RvD1 | Resolvin D1 |

| RvE1 | Resolvin E1 |

| SPECT | Single photon emission computed tomography |

| SPM | Specialized pro-resolving lipid mediator |

| TX | Thromboxane |

References

- Sperling, R.A.; Aisen, P.S.; Beckett, L.A.; Bennett, D.A.; Craft, S.; Fagan, A.M.; Iwatsubo, T.; Jack, C.R.; Kaye, J.; Montine, T.J.; et al. Toward defining the preclinical stages of Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2011, 7, 280–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzheimer’s Disease International. World Alzheimer Report 2019: Attitudes to Dementia; Alzheimer’s Disease International: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, J.; Cooper, N.R.; Webster, S.; Schultz, J.; McGeer, P.L.; Styren, S.D.; Civin, W.H.; Brachova, L.; Bradt, B.; Ward, P.; et al. Complement activation by β-amyloid in Alzheimer disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1992, 89, 10016–10020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, H.; Burdick, D.; Glabe, C.G.; Cotman, C.W.; Tenner, A.J. beta-Amyloid activates complement by binding to a specific region of the collagen-like domain of the C1q A chain. J. Immunol. 1994, 152. [Google Scholar]

- Afagh, A.; Cummings, B.J.; Cribbs, D.H.; Cotman, C.W.; Tenner, A.J. Localization and cell association of C1q in Alzheimer’s disease brain. Exp. Neurol. 1996, 138, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Frederickson, R.C.A.; Brunden, K.R. Neuroglial-mediated immunoinflammatory responses in Alzheimer’s disease: Complement activation and therapeutic approaches. Neurobiol. Aging 1996, 17, 781–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, S.; Bradt, B.; Rogers, J.; Cooper, N. Aggregation State-Dependent Activation of the Classical Complement Pathway by the Amyloid β Peptide. J. Neurochem. 2002, 69, 388–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, S.; Lue, L.F.; Brachova, L.; Tenner, A.J.; McGeer, P.L.; Terai, K.; Walker, D.G.; Bradt, B.; Cooper, N.R.; Rogers, J. Molecular and cellular characterization of the membrane attack complex, C5b-9, in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging 1997, 18, 415–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Lue, L.F.; Yang, L.B.; Roher, A.; Kuo, Y.M.; Strohmeyer, R.; Goux, W.J.; Lee, V.; Johnson, G.V.W.; Webster, S.D.; et al. Complement activation by neurofibrillary tangles in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurosci. Lett. 2001, 305, 165–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heneka, M.T.; Golenbock, D.T.; Latz, E. Innate immunity in Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Immunol. 2015, 16, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venegas, C.; Kumar, S.; Franklin, B.S.; Dierkes, T.; Brinkschulte, R.; Tejera, D.; Vieira-Saecker, A.; Schwartz, S.; Santarelli, F.; Kummer, M.P.; et al. Microglia-derived ASC specks crossseed amyloid-β in Alzheimer’s disease. Nature 2017, 552, 355–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heneka, M.T.; Carson, M.J.; Khoury, J.E.; Landreth, G.E.; Brosseron, F.; Feinstein, D.L.; Jacobs, A.H.; Wyss-Coray, T.; Vitorica, J.; Ransohoff, R.M.; et al. Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet. Neurol. 2015, 14, 388–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canet, G.; Hernandez, C.; Zussy, C.; Chevallier, N.; Desrumaux, C.; Givalois, L. Is AD a stress-related disorder? Focus on the HPA axis and its promising therapeutic targets. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2019, 11, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGeer, P.L.; Itagaki, S.; Boyes, B.E.; McGeer, E.G. Reactive microglia are positive for HLA-DR in the: Substantia nigra of Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s disease brains. Neurology 1988, 38, 1285–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, J.; Akama, K.T.; Krafft, G.A.; Chromy, B.A.; Van Eldik, L.J. Amyloid-β peptide activates cultured astrocytes: Morphological alterations, cytokine induction and nitric oxide release. Brain Res. 1998, 785, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akiyama, H.; Barger, S.; Barnum, S.; Bradt, B.; Bauer, J.; Cole, G.M.; Cooper, N.R.; Eikelenboom, P.; Emmerling, M.; Fiebich, B.L.; et al. Inflammation and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging 2000, 21, 383–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, A.; Nicoletti, F.; Mango, D.; Saidi, A.; Orlando, R.; Scaccianoce, S. Stress as risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease. Pharmacol. Res. 2018, 132, 130–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Risk Reduction of Cognitive Decline and Dementia WHO Guidelines; WHO Press: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Middleton, L.E.; Yaffe, K. Promising strategies for the prevention of dementia. Arch. Neurol. 2009, 66, 1210–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, A.; Nicoletti, F.; Gaetano, A.; Scaccianoce, S. Risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease: Focus on stress. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wekerle, H.; Linington, C.; Lassmann, H.; Meyermann, R. Cellular immune reactivity within the CNS. Trends Neurosci. 1986, 9, 271–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcgeer, P.L.; Mcgeer, E.; Rogers, J.; Sibley, J. Anti-inflammatory drugs and Alzheimer disease. Lancet 1990, 335, 1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beard, C.M.; Kokman, E.; Kurland, L.T. Rheumatoid arthritis and susceptibility to Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet 1991, 337, 1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkinson, M.L.; Bliss, M.R.; Brain, A.T.; Scott, D.L. Rheumatoid Arthritis and Senile Dementia of the Alzheimer’s Type. Br. J. Rheumstol. 1989, 28, 86–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinney, J.W.; Bemiller, S.M.; Murtishaw, A.S.; Leisgang, A.M.; Salazar, A.M.; Lamb, B.T. Inflammation as a central mechanism in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement. Transl. Res. Clin. Interv. 2018, 4, 575–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozben, T.; Ozben, S. Neuro-inflammation and anti-inflammatory treatment options for Alzheimer’s disease. Clin. Biochem. 2019, 72, 87–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehrer, S.; Rheinstein, P.H. Nasal steroids as a possible treatment for Alzheimer’s disease. Discov. Med. 2017, 24, 147–152. [Google Scholar]

- Jaturapatporn, D.; Isaac, M.G.E.K.N.; McCleery, J.; Tabet, N. Aspirin, steroidal and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Tan, L.; Wang, H.F.; Tan, C.C.; Meng, X.F.; Wang, C.; Tang, S.W.; Yu, J.T. Anti-inflammatory drugs and risk of Alzheimer’s Disease: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2015, 44, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narumiya, S. Physiology and Pathophysiology of Prostanoid Receptors. Proc. Jpn. Acad. Ser. B. Phys. Biol. Sci. 2007, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, D.W.; Mannon, R.B.; Mannon, P.J.; Latour, A.; Oliver, J.A.; Hoffman, M.; Smithies, O.; Koller, B.H.; Coffman, T.M. Coagulation defects and altered hemodynamic responses in mice lacking receptors for thromboxane A2. J. Clin. Invest. 1998, 102, 1994–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moncada, S.; Gryglewski, R.; Bunting, S.; Vane, J.R. An enzyme isolated from arteries transforms prostaglandin endoperoxides to an unstable substance that inhibits platelet aggregation. Nature 1976, 263, 663–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langenbach, R.; Loftin, C.D.; Christopher, L.; Tiano, H. Cyclooxygenase-deficient mice. A summary of their characteristics and susceptibilities to inflammation and carcinogenesis. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1999, 52–61. [Google Scholar]

- Sellers, R.S.; Radi, Z.A.; Khan, N.K. Pathophysiology of cyclooxygenases in cardiovascular homeostasis. Vet. Pathol. 2010, 47, 601–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serhan, C.N.; Hamberg, M.; Samuelsson, B. Lipoxins: Novel series of biologically active compounds formed from arachidonic acid in human leukocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1984, 81, 5335–5339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serhan, C.N.; Chiang, N.; Van Dyke, T.E. Resolving inflammation: Dual anti-inflammatory and pro-resolution lipid mediators. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2008, 8, 349–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuelsson, B.; Dahlén, S.E.; Lindgren, J.Å.; Rouzer, C.A.; Serhan, C.N. Leukotrienes and lipoxins: Structures, biosynthesis, and biological effects. Science 1987, 237, 1171–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serhan, C.N.; Chiang, N.; Dalli, J.; Levy, B.D. Lipid mediators in the resolution of inflammation. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2015, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazawa, K.; Kageyama, H. Physiological Activity of Docosahexaenoic Acid. J. Japan Oil Chem. Soc. 1991, 40, 974–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.; Gronert, K.; Devchand, P.R.; Moussignac, R.L.; Serhan, C.N. Novel docosatrienes and 17S-resolvins generated from docosahexaenoic acid in murine brain, human blood, and glial cells: Autacoids in anti-inflammation. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 14677–14687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serhan, C.N.; Hong, S.; Gronert, K.; Colgan, S.P.; Devchand, P.R.; Mirick, G.; Moussignac, R.L. Resolvins: A family of bioactive products of omega-3 fatty acid transformation circuits initiated by aspirin treatment that counter proinflammation signals. J. Exp. Med. 2002, 196, 1025–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serhan, C.N.; Clish, C.B.; Brannon, J.; Colgan, S.P.; Chiang, N.; Gronert, K. Novel functional sets of lipid-derived mediators with antiinflammatory actions generated from omega-3 fatty acids via cyclooxygenase 2-nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs and transcellular processing. J. Exp. Med. 2000, 192, 1197–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serhan, C.N. Treating inflammation and infection in the 21st century: New hints from decoding resolution mediators and mechanisms. FASEB J. 2017, 31, 1273–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serhan, C.N. Discovery of specialized pro-resolving mediators marks the dawn of resolution physiology and pharmacology. Mol. Aspects Med. 2017, 58, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiurchiù, V.; Leuti, A.; Dalli, J.; Jacobsson, A.; Battistini, L.; MaCcarrone, M.; Serhan, C.N. Proresolving lipid mediators resolvin D1, resolvin D2, and maresin 1 are critical in modulating T cell responses. Sci. Transl. Med. 2016, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colas, R.A.; Dalli, J.; Chiang, N.; Vlasakov, I.; Sanger, J.M.; Riley, I.R.; Serhan, C.N. Identification and Actions of the Maresin 1 Metabolome in Infectious Inflammation. J. Immunol. 2016, 197, 4444–4452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhu, B.; Li, Y. Resolution of cancer-promoting inflammation: A new approach for anticancer therapy. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Wang, X.; Sun, L.; Schultzberg, M.; Hjorth, E. Can inflammation be resolved in Alzheimer’s disease? Ther. Adv. Neurol. Disord. 2018, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhu, M.; Hjorth, E.; Cortés-Toro, V.; Eyjolfsdottir, H.; Graff, C.; Nennesmo, I.; Palmblad, J.; Eriksdotter, M.; Sambamurti, K.; et al. Resolution of inflammation is altered in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2015, 11, 40–50.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Wang, X.; Hjorth, E.; Colas, R.A.; Schroeder, L.; Granholm, A.C.; Serhan, C.N.; Schultzberg, M. Pro-Resolving Lipid Mediators Improve Neuronal Survival and Increase Aβ42 Phagocytosis. Mol. Neurobiol. 2016, 53, 2733–2749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Calon, F.; Julien, C.; Winkler, J.W.; Petasis, N.A.; Lukiw, W.J.; Bazan, N.G. Docosahexaenoic acid-derived neuroprotectin D1 induces neuronal survival via secretase- and PPARγ-mediated mechanisms in Alzheimer’s disease models. PLoS ONE 2011, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikonomovic, M.D.; Abrahamson, E.E.; Uz, T.; Manev, H.; DeKosky, S.T. Increased 5-lipoxygenase immunoreactivity in the hippocampus of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2008, 56, 1065–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohri, I.; Kadoyama, K.; Kanekiyo, T.; Sato, Y.; Kagitani-Shimono, K.; Saito, Y.; Suzuki, K.; Kudo, T.; Takeda, M.; Urade, Y.; et al. Hematopoietic prostaglandin D synthase and DP1 receptor are selectively upregulated in microglia and astrocytes within senile plaques from human patients and in a mouse model of Alzheimer disease. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2007, 66, 469–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dullemeijer, C.; Durga, J.; Brouwer, I.A.; van de Rest, O.; Kok, F.J.; Brummer, R.-J.M.; van Boxtel, M.P.J. Verhoef, P. n−3 Fatty acid proportions in plasma and cognitive performance in older adults. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007, 86, 1479–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nielsen, M.M.B.; Lambertsen, K.L.; Clausen, B.H.; Meyer, M.; Bhandari, D.R.; Larsen, S.T.; Poulsen, S.S.; Spengler, B.; Janfelt, C.; Hansen, H.S. Mass spectrometry imaging of biomarker lipids for phagocytosis and signalling during focal cerebral ischaemia. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serhan, C.N.; Levy, B.D. Resolvins in inflammation: Emergence of the pro-resolving superfamily of mediators. J. Clin. Invest. 2018, 128, 2657–2669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gronert, K. Lipid autacoids in inflammation and injury responses: A matter of privilege. Mol. Interv. 2008, 8, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serhan, C.N. Pro-resolving lipid mediators are leads for resolution physiology. Nature 2014, 510, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, M.; Cianci, E.; Simiele, F.; Recchiuti, A. Lipoxins and aspirin-triggered lipoxins in resolution of inflammation. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2015, 760, 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.; Livne-Bar, I.; Gronert, K.; Sivak, J.M. Fair-Weather Friends: Evidence of Lipoxin Dysregulation in Neurodegeneration. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2020, 64, 1801076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.X. Fat-1 transgenic mice: A new model for omega-3 research. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fat. Acids 2007, 77, 263–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serhan, C.N. Novel lipid mediators and resolution mechanisms in acute inflammation: To resolve or not? Am. J. Pathol. 2010, 177, 1576–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serhan, C.N. Novel Chemical Mediators in the Resolution of Inflammation: Resolvins and Protectins. Anesthesiol. Clin. North Am. 2006, 24, 341–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serhan, C.N.; Petasis, N.A. Resolvins and protectins in inflammation resolution. Chem. Rev. 2011, 111, 5922–5943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asatryan, A.; Bazan, N.G. Molecular mechanisms of signaling via the docosanoid neuroprotectin D1 for cellular homeostasis and neuroprotection. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 12390–12397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serhan, C.N.; Krishnamoorthy, S.; Recchiuti, A.; Chiang, N. Novel Anti-Inflammatory-Pro-Resolving Mediators and Their Receptors. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2012, 11, 629–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnamoorthy, S.; Recchiuti, A.; Chiang, N.; Yacoubian, S.; Lee, C.H.; Yang, R.; Petasis, N.A.; Serhan, C.N. Resolvin D1 binds human phagocytes with evidence for proresolving receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 1660–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiala, M.; Kooij, G.; Wagner, K.; Hammock, B.; Pellegrini, M. Modulation of innate immunity of patients with Alzheimer’s disease by omega-3 fatty acids. FASEB J. 2017, 31, 3229–3239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz, A.; Sarabia, C.; Torres, M.; Juárez, E. Resolvin D1 (RvD1) and maresin 1 (Mar1) contribute to human macrophage control of M. tuberculosis infection while resolving inflammation. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2019, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddox, J.F.; Hachicha, M.; Takano, T.; Petasis, N.A.; Fokin, V.V.; Serhan, C.N. Lipoxin A4 stable analogs are potent mimetics that stimulate human monocytes and THP-1 cells via a G-protein-linked lipoxin A4 receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 6972–6978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, Y.; Gong, W.; Tiffany, H.L.; Tumanov, A.; Nedospasov, S.; Shen, W.; Dunlop, N.M.; Gao, J.L.; Murphy, P.M.; Oppenheim, J.J.; et al. Amyloid (beta)42 activates a G-protein-coupled chemoattractant receptor, FPR-like-1. J. Neurosci. 2001, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emre, C.; Hjorth, E.; Bharani, K.; Carroll, S.; Granholm, A.; Schultzberg, M. Receptors for pro-resolving mediators are increased in Alzheimer’s disease brain. Brain Pathol. 2020, 30, 614–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, N.; Libreros, S.; Norris, P.C.; De La Rosa, X.; Serhan, C.N. Maresin 1 activates LGR6 receptor promoting phagocyte immunoresolvent functions. J. Clin. Invest. 2019, 129, 5294–5311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, D.S. Maresin-1 resolution with RORα and LGR6. Prog. Lipid Res. 2020, 78, 101034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Y.H.; Shin, K.O.; Kim, J.Y.; Khadka, D.B.; Kim, H.J.; Lee, Y.M.; Cho, W.J.; Cha, J.Y.; Lee, B.J.; Lee, M.O. A maresin 1/RORα/12-lipoxygenase autoregulatory circuit prevents inflammation and progression of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. J. Clin. Invest. 2019, 129, 1684–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bang, S.; Xie, Y.K.; Zhang, Z.J.; Wang, Z.; Xu, Z.Z.; Ji, R.R. GPR37 regulates macrophage phagocytosis and resolution of inflammatory pain. J. Clin. Invest. 2018, 128, 3568–3582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, L.; Caterina, M.J. Accelerating the reversal of inflammatory pain with NPD1 and its receptor GPR37. J. Clin. Invest. 2018, 128, 3246–3249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondue, B.; Wittamer, V.; Parmentier, M. Chemerin and its receptors in leukocyte trafficking, inflammation and metabolism. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2011, 22, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fülöp, P.; Seres, I.; Lorincz, H.; Harangi, M.; Somodi, S.; Paragh, G. Association of chemerin with oxidative stress, inflammation and classical adipokines in non-diabetic obese patients. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2014, 18, 1313–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Z.; Dong, J.; Wu, W.; Yang, T.; Wang, T.; Guo, L.; Chen, L.; Xu, D.; Wen, F. Resolvin D1 attenuates inflammation in lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury through a process involving the PPARγ/NF-κB pathway. Respir. Res. 2012, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberger, B.; Quizon, C.; Vetrano, A.M.; Archer, F.; Laskin, J.D.; Laskin, D.L. Mechanisms mediating reduced responsiveness of neonatal neutrophils to lipoxin A4. Pediatr. Res. 2008, 64, 393–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobrado, M.; Pereira, M.P.; Ballesteros, I.; Hurtado, O.; Fernández-López, D.; Pradillo, J.M.; Caso, J.R.; Vivancos, J.; Nombela, F.; Serena, J.; et al. Synthesis of lipoxin A 4 by 5-lipoxygenase mediates pparγ-dependent, neuroprotective effects of rosiglitazone in experimental stroke. J. Neurosci. 2009, 29, 3875–3884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rees, D.; Miles, E.A.; Banerjee, T.; Wells, S.J.; Roynette, C.E.; Wahle, K.W.J.; Calder, P.C. Dose-related effects of eicosapentaenoic acid on innate immune function in healthy humans: A comparison of young and older men. Am J. Clin. Nutr. 2006, 83, 331–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medeiros, R.; Kitazawa, M.; Passos, G.F.; Baglietto-Vargas, D.; Cheng, D.; Cribbs, D.H.; Laferla, F.M. Aspirin-triggered lipoxin A4 stimulates alternative activation of microglia and reduces alzheimer disease-like pathology in mice. Am. J. Pathol. 2013, 182, 1780–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunn, H.C.; Ager, R.R.; Baglietto-Vargas, D.; Cheng, D.; Kitazawa, M.; Cribbs, D.H.; Medeiros, R. Restoration of lipoxin A4 signaling reduces Alzheimer’s disease-like pathology in the 3xTg-AD mouse model. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2015, 43, 893–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, M.; Jones, S.M.; Phare, S.M.; Coffey, M.J.; Peters-Golden, M.; Brock, T.G. Protein kinase a inhibits leukotriene synthesis by phosphorylation of 5-lipoxygenase on serine 523. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 41512–41520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, Y.; Lin, Y.; Perez-Polo, J.R.; Uretsky, B.F.; Ye, Z.; Tieu, B.C.; Birnbaum, Y. Phosphorylation of 5-Lipoxygenase at Ser 523 by Protein Kinase A Determines Whether Pioglitazone and Atorvastatin Induce Proinflammatory Leukotriene B 4 or Anti-Inflammatory 15-Epi-Lipoxin A 4 Production. J. Immunol. 2008, 181, 3515–3523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serhan, C.N.; Chiang, N.; Dalli, J. The resolution code of acute inflammation: Novel pro-resolving lipid mediators in resolution. Semin. Immunol. 2015, 27, 200–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joffre, C.; Rey, C.; Layé, S. N-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and the resolution of neuroinflammation. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Planagumà, A.; Kazani, S.; Marigowda, G.; Haworth, O.; Mariani, T.J.; Israel, E.; Bleecker, E.R.; Curran-Everett, D.; Erzurum, S.C.; Calhoun, W.J.; et al. Airway lipoxin A4 generation and lipoxin A4 receptor expression are decreased in severe asthma. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2008, 178, 574–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyata, J.; Fukunaga, K.; Iwamoto, R.; Isobe, Y.; Niimi, K.; Takamiya, R.; Takihara, T.; Tomomatsu, K.; Suzuki, Y.; Oguma, T.; et al. Dysregulated synthesis of protectin D1 in eosinophils from patients with severe asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2013, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredman, G.; Oh, S.F.; Ayilavarapu, S.; Hasturk, H.; Serhan, C.N.; van Dyke, T.E. Impaired phagocytosis in localized aggressive periodontitis: Rescue by resolvin E1. PLoS ONE 2011, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoki, H.; Hisada, T.; Ishizuka, T.; Utsugi, M.; Kawata, T.; Shimizu, Y.; Okajima, F.; Dobashi, K.; Mori, M. Resolvin E1 dampens airway inflammation and hyperresponsiveness in a murine model of asthma. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2008, 367, 509–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spite, M.; Norling, L.V.; Summers, L.; Yang, R.; Cooper, D.; Petasis, N.A.; Flower, R.J.; Perretti, M.; Serhan, C.N. Resolvin D2 is a potent regulator of leukocytes and controls microbial sepsis. Nature 2009, 461, 1287–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arita, M.; Yoshida, M.; Hong, S.; Tjonahen, E.; Glickman, J.N.; Petasis, N.A.; Blumberg, R.S.; Serhan, C.N. Resolvin E1, an endogenous lipid mediator derived from omega-3 eicosapentaenoic acid, protects against 2,4,6-trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid-induced colitis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 7671–7676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor, K.M.; Sangiovanni, J.P.; Lofqvist, C.; Aderman, C.M.; Chen, J.; Higuchi, A.; Hong, S.; Pravda, E.A.; Majchrzak, S.; Carper, D.; et al. Increased dietary intake of ω-3-polyunsaturated fatty acids reduces pathological retinal angiogenesis. Nat. Med. 2007, 13, 868–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Z.Z.; Zhang, L.; Liu, T.; Park, J.Y.; Berta, T.; Yang, R.; Serhan, C.N.; Ji, R.R. Resolvins RvE1 and RvD1 attenuate inflammatory pain via central and peripheral actions. Nat. Med. 2010, 16, 592–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.Y.; Han, S.H.; Park, M.H.; Song, I.S.; Choi, M.K.; Yu, E.; Park, C.M.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, S.H.; Schuchman, E.H.; et al. N-AS-triggered SPMs are direct regulators of microglia in a model of Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petursdottir, A.L.; Farr, S.A.; Morley, J.E.; Banks, W.A.; Skuladottir, G.V. Effect of Dietary n-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids on Brain Lipid Fatty Acid Composition, Learning Ability, and Memory of Senescence-Accelerated Mouse. J. Gerontol. 2008, 63, 1153–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalmijn, S.; Launer, L.J.; Ott, A.; Witteman, J.C.M.; Hofman, A.; Breteler, M.M.B. Dietary fat intake and the risk of incident dementia in the Rotterdam study. Ann. Neurol. 1997, 42, 776–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelhart, M.J.; Geerlings, M.I.; Ruitenberg, A.; Van Swieten, J.C.; Hofman, A.; Witteman, J.C.M.; Breteler, M.M.B. Diet and risk of dementia: Does fat matter? The Rotterdam study. Neurology 2002, 59, 1915–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, C.; de Souto Barreto, P.; Coley, N.; Cantet, C.; Cesari, M.; Andrieu, S.; Vellas, B. Cognitive changes with omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in non-demented older adults with low omega-3 index. J. Nutr. Heal. Aging 2017, 21, 988–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freund-Levi, Y.; Eriksdotter-Jönhagen, M.; Cederholm, T.; Basun, H.; Faxén-Irving, G.; Garlind, A.; Vedin, I.; Vessby, B.; Wahlund, L.O.; Palmblad, J. ω-3 fatty acid treatment in 174 patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer disease: OmegAD study—A randomized double-blind trial. Arch. Neurol. 2006, 63, 1402–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, C.C.; Su, K.P.; Cheng, T.C.; Liu, H.C.; Chang, C.J.; Dewey, M.E.; Stewart, R.; Huang, S.Y. The effects of omega-3 fatty acids monotherapy in Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment: A preliminary randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2008, 32, 1538–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yurko-Mauro, K.; McCarthy, D.; Rom, D.; Nelson, E.B.; Ryan, A.S.; Blackwell, A.; Salem, N.; Stedman, M. Beneficial effects of docosahexaenoic acid on cognition in age-related cognitive decline. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2010, 6, 456–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loef, M.; Walach, H. The Omega-6/Omega-3 Ratio and Dementia or Cognitive Decline: A Systematic Review of Human Studies and Biological Evidence. J. Nutr. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2013, 32, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, J.F.; Raman, R.; Thomas, R.G.; Yurko-Mauro, K.; Nelson, E.B.; Van Dyck, C.; Galvin, J.E.; Emond, J.; Jack, C.R.; Weiner, M.; et al. Docosahexaenoic acid supplementation and cognitive decline in Alzheimer disease: A randomized trial. JAMA - J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2010, 304, 1903–1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, M.A.; Childs, C.E.; Calder, P.C.; Rogers, P.J. No effect of omega-3 fatty acid supplementation on cognition and mood in individuals with cognitive impairment and probable Alzheimer’s disease: A randomised controlled trial. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 24600–24613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabue-Teguo, M.; de Souza, P.B.; Cantet, C.; Andrieu, S.; Simo, N.; Fougère, B.; Dartigues, J.F.; Vellas, B. Effect of Multidomain Intervention, Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids Supplementation or their Combinaison on Cognitive Function in Non-Demented Older Adults According to Frail Status: Results from the MAPT Study. J. Nutr. Heal. Aging 2018, 22, 923–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiala, M.; Restrepo, L.; Pellegrini, M. Immunotherapy of Mild Cognitive Impairment by ω-3 Supplementation: Why Are Amyloid-β Antibodies and ω-3 Not Working in Clinical Trials? J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2018, 62, 1013–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serhan, C.N.; Dalli, J.; Colas, R.A.; Winkler, J.W.; Chiang, N. Protectins and maresins: New pro-resolving families of mediators in acute inflammation and resolution bioactive metabolome. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2015, 1851, 397–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serhan, C.N.; Yang, R.; Martinod, K.; Kasuga, K.; Pillai, P.S.; Porter, T.F.; Oh, S.F.; Spite, M. Maresins: Novel macrophage mediators with potent antiinflammatory and proresolving actions. J. Exp. Med. 2009, 206, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serhan, C.N.; Dalli, J.; Karamnov, S.; Choi, A.; Park, C.; Xu, Z.; Ji, R.; Zhu, M.; Petasis, N.A. Macrophage proresolving mediator maresin 1 stimulates tissue regeneration and controls pain. FASEB J. 2012, 26, 1755–1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathod, K.S.; Kapil, V.; Velmurugan, S.; Khambata, R.; Siddique, U.; Khan, S.; Van Eijl, S.; Gee, L.; Bansal, J.; Pitrola, K.; et al. Accelerated resolution of inflammation underlies sex differences in inflammatory responses in humans. J. Clin. Invest. 2017, 127, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, A.; Sharma, A.; Chen, M.; Toy, R.; Mottola, G.; Conte, M.S. The pro-resolving lipid mediator maresin 1 (MaR1) attenuates inflammatory signaling pathways in vascular smooth muscle and endothelial cells. PLoS ONE 2014, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, T.; Xu, G.; Newton, P.T.; Chagin, A.S.; Mkrtchian, S.; Carlström, M.; Zhang, X.M.; Harris, R.A.; Cooter, M.; Berger, M.; et al. Maresin 1 attenuates neuroinflammation in a mouse model of perioperative neurocognitive disorders. Br. J. Anaesth. 2019, 122, 350–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mizwicki, M.T.; Liu, G.; Fiala, M.; Magpantay, L.; Sayre, J.; Siani, A.; Mahanian, M.; Weitzman, R.; Hayden, E.Y.; Rosenthal, M.J.; et al. 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 and resolvin D1 retune the balance between amyloid-β phagocytosis and inflammation in Alzheimer’s disease patients. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2013, 34, 155–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heras-Sandoval, D.; Pedraza-Chaverri, J.; Pérez-Rojas, J.M. Role of docosahexaenoic acid in the modulation of glial cells in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neuroinflammation 2016, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Wu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wu, J.; Song, L.; Xian, W.; Yuan, S.; Pei, L.; Shang, Y. Resolvin D1 promotes the interleukin-4-induced alternative activation in BV-2 microglial cells. J. Neuroinflammation 2014, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazan, N.G. The docosanoid neuroprotectin D1 induces homeostatic regulation of neuroinflammation and cell survival. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fat. Acids 2013, 88, 127–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Stark, D.T.; Bazan, N.G. Neuroprotectin D1 induces neuronal survival and downregulation of amyloidogenic processing in Alzheimer’s disease cellular models. Mol. Neurobiol. 2011, 43, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, P.; Wang, S.; Wei, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, J.; Yin, X.; Feng, J.; Zhu, M. Maresin1 Decreased Microglial Chemotaxis and Ameliorated Inflammation Induced by Amyloid-β42 in Neuron-Microglia Co-Culture Models. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2020, 73, 503–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serhan, C.N.; Yacoubian, S.; Yang, R. Anti-Inflammatory and Proresolving Lipid Mediators. Annu. Rev. Pathol. Mech. Dis. 2008, 3, 279–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, P.; Wang, X.; Wang, S.; Wei, Y.; Feng, J.; Zhu, M. Maresin 1 Improves Cognitive Decline and Ameliorates Inflammation in a Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2019, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, M.C.; Evans, D.A.; Bienias, J.L.; Tangney, C.C.; Bennett, D.A.; Wilson, R.S.; Aggarwal, N.; Schneider, J. Consumption of fish and n-3 fatty acids and risk of incident Alzheimer disease. Arch. Neurol. 2003, 60, 940–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Famenini, S.; Rigali, E.A.; Olivera-Perez, H.M.; Dang, J.; Chang, M.T.; Halder, R.; Rao, R.V.; Pellegrini, M.; Porter, V.; Bredesen, D.; et al. Increased intermediate M1-M2 macrophage polarization and improved cognition in mild cognitive impairment patients on v-3 supplementation. FASEB J. 2017, 31, 148–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.J.; Xue, Y.; Liu, X.F.; Xue, C.H.; Wang, J.F.; Du, L.; Takahashi, K.; Wang, Y.M. The protective effect of eicosapentaenoic acid-enriched phospholipids from sea cucumber Cucumaria frondosa on oxidative stress in PC12 cells and SAMP8 mice. Neurochem. Int. 2014, 64, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vela, S.; Sainz, N.; Moreno-Aliaga, M.J.; Solas, M.; Ramirez, M.J. DHA Selectively Protects SAMP-8-Associated Cognitive Deficits Through Inhibition of JNK. Mol. Neurobiol. 2019, 56, 1618–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.Z.; Zhang, B.Z.; Zhao, X.J.; Zhang, Z.Y. Resolvin D1 ameliorates cognitive impairment following traumatic brain injury via protecting astrocytic mitochondria. J. Neurochem. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelmoaty, S.; Wigerblad, G.; Bas, D.B.; Codeluppi, S.; Fernandez-Zafra, T.; El-Awady, E.S.; Moustafa, Y.; Abdelhamid, A.E.-d.S.; Brodin, E.; Svensson, C.I. Spinal Actions of Lipoxin A4 and 17(R)-Resolvin D1 Attenuate Inflammation-Induced Mechanical Hypersensitivity and Spinal TNF Release. PLoS ONE 2013, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terrando, N.; Gómez-Galán, M.; Yang, T.; Carlström, M.; Gustavsson, D.; Harding, R.E.; Lindskog, M.; Eriksson, L.I. Aspirin-triggered resolvin D1 prevents surgery-induced cognitive decline. FASEB J. 2013, 27, 3564–3571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.X.; Mardini, F.; Janik, L.S.; Garrity, S.T.; Li, R.Q.; Bachlani, G.; Eckenhoff, R.G.; Eckenhoff, M.F. Modulation of murine alzheimer pathogenesis and behavior by surgery. Ann. Surg. 2013, 257, 439–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bathina, S.; Gundala, N.K.V.; Rhenghachar, P.; Polavarapu, S.; Hari, A.D.; Sadananda, M.; Das, U.N. Resolvin D1 Ameliorates Nicotinamide-streptozotocin-induced Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus by its Anti-inflammatory Action and Modulating PI3K/Akt/mTOR Pathway in the Brain. Arch. Med. Res. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waechter, V.; Schmid, M.; Herova, M.; Weber, A.; Günther, V.; Marti-Jaun, J.; Wüst, S.; Rösinger, M.; Gemperle, C.; Hersberger, M. Characterization of the Promoter and the Transcriptional Regulation of the Lipoxin A4 Receptor (FPR2/ALX) Gene in Human Monocytes and Macrophages. J. Immunol. 2012, 188, 1856–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiala, M.; Halder, R.C.; Sagong, B.; Ross, O.; Sayre, J.; Porter, V.; Bredesen, D.E. ω-3 supplementation increases amyloid-β phagocytosis and resolvin D1 in patients with minor cognitive impairment. FASEB J. 2015, 29, 2681–2689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, P.K.; Marcheselli, V.L.; Serhan, C.N.; Bazan, N.G. Neuroprotectin D1: A docosahexaenoic acid-derived docosatriene protects human retinal pigment epithelial cells from oxidative stress. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 8491–8496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukiw, W.J.; Cui, J.G.; Marcheselli, V.L.; Bodker, M.; Botkjaer, A.; Gotlinger, K.; Serhan, C.N.; Bazan, N.G. A role for docosahexaenoic acid-derived neuroprotectin D1 in neural cell survival and Alzheimer disease. J. Clin. Invest. 2005, 115, 2774–2783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoghbi, H.Y.; Orr, H.T. Pathogenic mechanisms of a polyglutamine-mediated neurodegenerative disease, Spinocerebellar ataxia type 1. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 7425–7429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazan, N.G. Docosanoids and elovanoids from omega-3 fatty acids are pro-homeostatic modulators of inflammatory responses, cell damage and neuroprotection. Mol. Aspects Med. 2018, 64, 18–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calandria, J.M.; Asatryan, A.; Balaszczuk, V.; Knott, E.J.; Jun, B.K.; Mukherjee, P.K.; Belayev, L.; Bazan, N.G. NPD1-mediated stereoselective regulation of BIRC3 expression through cREL is decisive for neural cell survival. Cell Death Differ. 2015, 22, 1363–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halapin, N.A.; Bazan, N.G. NPD1 induction of retinal pigment epithelial cell survival involves PI3K/Akt phosphorylation signaling. Neurochem. Res. 2010, 35, 1944–1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcheselli, V.L.; Hong, S.; Lukiw, W.J.; Tian, X.H.; Gronert, K.; Musto, A.; Hardy, M.; Gimenez, J.M.; Chiang, N.; Serhan, C.N.; et al. Novel Docosanoids Inhibit Brain Ischemia-Reperfusion-mediated Leukocyte Infiltration and Pro-inflammatory Gene Expression. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 43807–43817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czapski, G.A.; Czubowicz, K.; Strosznajder, J.B.; Strosznajder, R.P. The lipoxygenases: Their regulation and implication in alzheimer’s disease. Neurochem. Res. 2016, 41, 243–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinsen, A.; Tejera, N.; Vauzour, D.; Harden, G.; Dick, J.; Shinde, S.; Barden, A.; Mori, T.A.; Minihane, A.M. Altered SPMs and age-associated decrease in brain DHA in APOE4 female mice. FASEB J. 2019, 33, 10315–10326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| SPMs | Receptor | Bioaction in AD | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| MaR1 | LGR6 | Promote microglial phagocytosis of Aβ Promote tissue regeneration Analgesic effect | [50,111,113] |

| RvD1 | ALX/FPR2 & GPR32 | Enhance tissue remodeling in microglia Promote macrophage phagocytosis of Aβ | [117,118,119] |

| NPD1 | GPR37 | Influence cell survival, neuroinflammatory signaling and transcription Suppress the production of APP | [51,120,121] |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Miyazawa, K.; Fukunaga, H.; Tatewaki, Y.; Takano, Y.; Yamamoto, S.; Mutoh, T.; Taki, Y. Alzheimer’s Disease and Specialized Pro-Resolving Lipid Mediators: Do MaR1, RvD1, and NPD1 Show Promise for Prevention and Treatment? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5783. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21165783

Miyazawa K, Fukunaga H, Tatewaki Y, Takano Y, Yamamoto S, Mutoh T, Taki Y. Alzheimer’s Disease and Specialized Pro-Resolving Lipid Mediators: Do MaR1, RvD1, and NPD1 Show Promise for Prevention and Treatment? International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2020; 21(16):5783. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21165783

Chicago/Turabian StyleMiyazawa, Keishi, Hisanori Fukunaga, Yasuko Tatewaki, Yumi Takano, Shuzo Yamamoto, Tatsushi Mutoh, and Yasuyuki Taki. 2020. "Alzheimer’s Disease and Specialized Pro-Resolving Lipid Mediators: Do MaR1, RvD1, and NPD1 Show Promise for Prevention and Treatment?" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 21, no. 16: 5783. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21165783

APA StyleMiyazawa, K., Fukunaga, H., Tatewaki, Y., Takano, Y., Yamamoto, S., Mutoh, T., & Taki, Y. (2020). Alzheimer’s Disease and Specialized Pro-Resolving Lipid Mediators: Do MaR1, RvD1, and NPD1 Show Promise for Prevention and Treatment? International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 21(16), 5783. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21165783