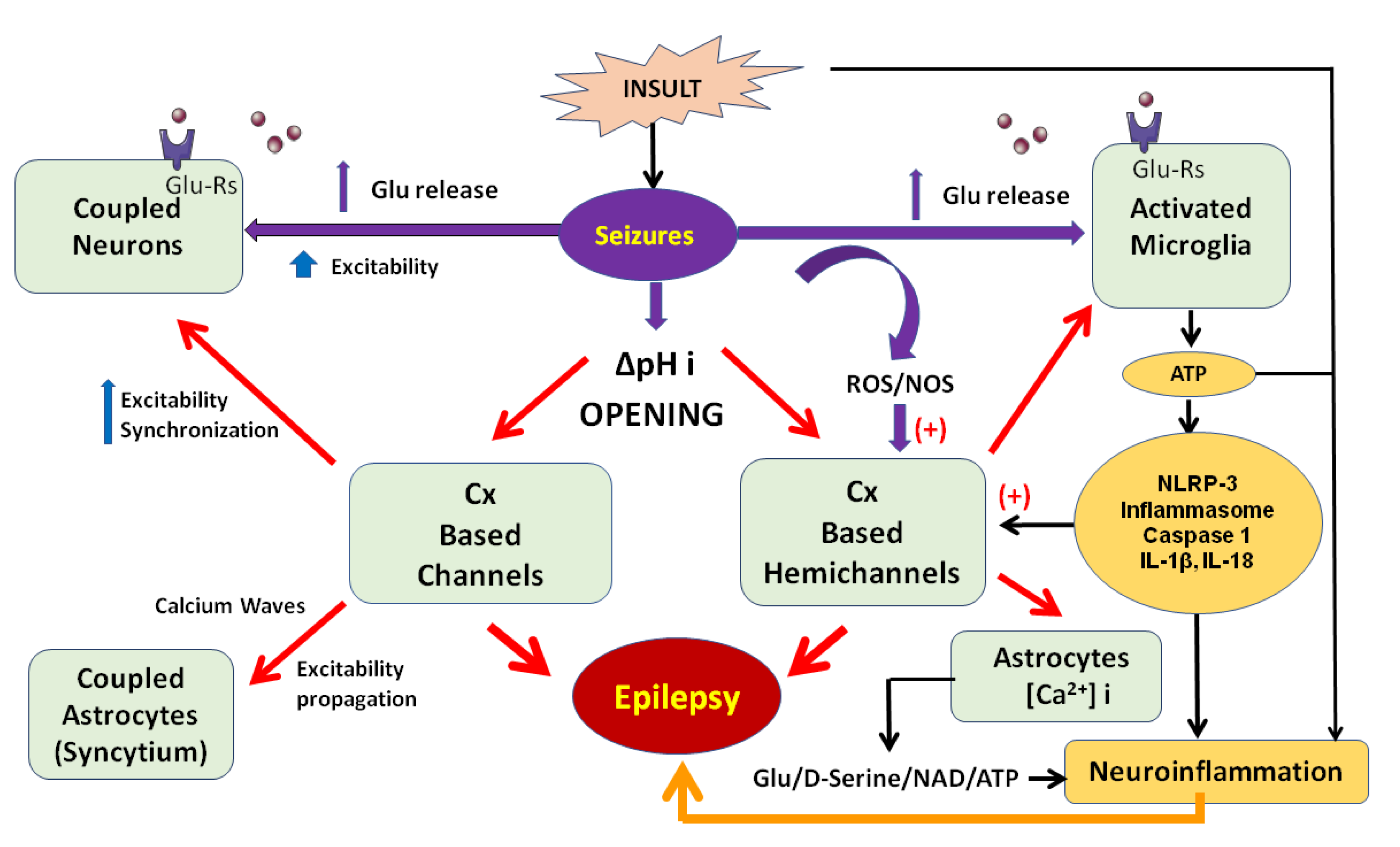

Connexins-Based Hemichannels/Channels and Their Relationship with Inflammation, Seizures and Epilepsy

Abstract

1. Molecular and Cellular Characteristics of Connexins-Based Hemichannels and Channels

2. Connexins-Based Hemichannels/Channels and Neuroinflammation

3. Blockers of Connexins-Based Channels/Hemichannels as Anticonvulsive and Antiepileptic Therapeutic Targets in Different Models of Seizures and Epilepsy

| Blocker(s) of Cxs-Based Hemichannels or Channels | Seizure or Epilepsy Model | Technique/Brain Region | Main Results | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbenoxolone (10 μM) and quinine (35 μM) administered through a piece of filter paper covering the cortical surface | In vivo: local application of crystalline 4-AP on the surface of the cortex | Electrocorticography (ECoG) in the brains of adult Wistar rats (male and female, 30–40 days old, 200–250 g) | Anticonvulsive effect of carbenoxolone (reduced the generation of seizure discharges); quinine decreased summated ictal activity and the amplitudes of seizure discharges | [125] |

| Carbenoxolone (150 mM) and meclofenamic acid (50 mM) administered through a cannula implanted in the right motor cortex | In vivo: a model of refractory focal cortical epilepsy induced with tetanus toxin (50 ng/0.5 μL, pH 7.5) in 2% bovine serum albumin | Intracranial electroencephalography (iEEG) in the right motor cortex of adult Sprague-Dawley rats (240–320 g) | Reduced the percentage of seizure time | [126] |

| Quinine (200, 400 or 1000 nmol) administered through a cannula implanted in the ventricle of the brain | In vivo: a model of epilepsy induced by 300 IU of crystallized penicillin | Epidural EEG in adult Wistar rats (male, 4 months) | Decreased the amplitude and frequency of epileptiform spikes and attenuated convulsive behavior | [127] |

| Carbenoxolone injection (50 nmol) administered through a cannula implanted in the entorhinal cortex | In vivo: a model of seizures induced by 4-aminopyridine (10 nmol) administered through a cannula implanted in the entorhinal cortex | Epidural EEG and iEEG in the entorhinal cortex of adult Wistar rats (male, 250–350 g) | Decreased the amplitude and frequency of epileptiform discharges and the number and duration of epileptiform trains | [128] |

| Carbenoxolone, Gap 27 (mimetic amino acid residues 201–211, SRPTEKTIFII) and SLS (amino acid residues 180–195, SLSAVYTCKRDPCPHQ) peptides | In vitro: epileptiform activity induced in organotypic hippocampal slice cultures by stimulation | Extracellular recordings from the CA1 and CA3 regions of hippocampal slices from 7-day-old Wistar rats | Carbenoxolone inhibited both spontaneous and evoked seizure-like events; the Cx43 mimetic peptides selectively attenuated spontaneous recurrent epileptiform activity after prolonged (10 h) treatment | [146] |

| Quinine injection (35 pmol) administered through a cannula implanted in the entorhinal cortex | In vivo: a model of seizures induced by 4-aminopyridine (10 nmol) administered through a cannula implanted in the entorhinal cortex | Epidural EEG and iEEG in the entorhinal cortex of adult Wistar rats (male, 250–350 g) | Decreased the amplitude and frequency of discharge trains and blocked seizure behavior in five of six rats | [129] |

| Cx43 mimetic peptide (5 and 50 μM, sufficient to block hemichannels, VDCFLSRPTEKT, extracellular loop two of Cx43) | In vitro: a model of epileptiform injury induced by bicuculline methochloride (BMC) (48 h exposure to 100 μM) in hippocampal slices cultures from 6- to 8-day-old Wistar rats | Measurement of cell death after epileptiform activity (fluorescence signal) and immunohistochemistry for microtubule-associated protein (MAP2) | Exerted a protective effect in the CA1 region during the recovery period (24 h after BMC treatment) | [147] |

| Carbenoxolone (20 mg/kg, i.p.) once a day for 14 days | In vivo: a model of posttraumatic epilepsy induced by ferric ions (microinjection of 10 μL of 0.1 M FeCl3 solution into the sensorimotor area) | Evaluation of convulsive behavior according to the Racine scale in adult male Sprague-Dawley rats aged 6–8 weeks and weighing 220–250 g | Ameliorated convulsive behavior score in rats | [130] |

| Carbenoxolone (50 nmol) and quinine (35 pmol) administered through a guide cannula in the entorhinal cortex (0.2 μL/min for 5 min) | In vivo: a pilocarpine-induced model of temporal lobe epilepsy (1.2 mg/μL pilocarpine hydrochloride in a total volume of 2 μL, intracerebroventricular (i.c.v.) | iEEG in the hippocampus of epileptic adult Wistar rats (male, 190–200 g) | Decreased the number of Fast Ripples (FR) events and oscillation cycles per FR event | [150] |

| Carbenoxolone (0.2 mM) | In vitro: Neocortical slices | Neocortical slices from epileptic patients (temporal and occipital regions) | Strongly decreased the incidence of FR events | [152] |

| In silico: a small network of 256 multicompartment cells | Simulated networks containing only pyramidal cells, coupled only by axonal gap junctions, and without chemical synapses or interneurons | The network produced FR events via a cluster of axonal Cx-based channels (gap junctions) | ||

| Carbenoxolone (40 mg/kg, i.p.) and carbenoxolone + valproic acid (300 mg/kg, i.p.) | In vivo: a kindling model of epilepsy induced by pentylenetetrazole (35 mg/kg, i.p.) | Epidural EEG in Wistar rats (female, 12–15 weeks old, 200 ± 50 g) | Carbenoxolone prevented generalized seizures and reduced seizure stage, seizure duration and spike frequency; no significant difference between carbenoxolone + valproic acid and valproic acid | [131] |

| Carbenoxolone (50 mg/kg, i.p., for 3 days) and quinine (50 mg/kg, i.p. for 3 days) | In vivo: a lithium/pilocarpine-induced Status epilepticus (SE) model (i.p. injection of 50 mg/kg pilocarpine 18–20 h after the i.p. injection of 127 mg/kg lithium chloride) | iEEG in the hippocampus of adult Sprague-Dawley rats (male) | Reduced the spectral power of FR events 10 min after SE | [151] |

| Coadministration of valproate (VPA), phenytoin (PHT), or carbamazepine (CBZ) at subtherapeutic doses (i.p.) with carbenoxolone (60 mg/kg, i.p., 5 mL/kg) or quinine (40 mg/kg, i.p., 5 mL/kg) | In vivo: maximal electroshock (MES)-induced (frequency of 60 Hz, pulse width of 0.6 ms, shock duration of 0.6 s, and a current of 90 mA) and pentylenetetrazole (PTZ)-induced (70 mg/kg, i.p.) models of seizures | EEG and power spectral analysis in Wistar rats (male, 270–300 g) | Quinine increased the anticonvulsant activity of VPA, PHT and CBZ to generalized tonic-clonic seizures in the MES-induced model and the anticonvulsant activity of CBZ only to generalized tonic-clonic seizures in the PTZ-induced model | [132] |

| TAT-Gap 19 (200 mM for in vitro experiments; 12 mM intrahippocampal and 1 mM in a total volume of 1 μL i.c.v. for in vivo experiments); TAT-Gap19 (25 or 50 mg/kg i.p., electrical stimulation for in vivo experiments) | In vitro: pilocarpine (15 μM) administration in acute brain slices; In vivo: pilocarpine model in mice and rats (12 mM, intra hippocampal) Limbic psychomotor seizures by corneal stimulation | In vitro: ethidium bromide uptake experiments in acute brain slices from Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein-enhanced Green Fluorescent Protein (GFAP-eGFP) transgenic mice (both genders, 2 months old); In vivo: video-EcoG analysis (seizure duration) or modified Racine’s scale evaluation (to score kindling-induced behavioral changes) in NMRI mice (male, 20–30 g) and, video-EcoG and Racine scale evaluation of convulsive behavior in Wistar rats (male, 250–300 g) | In vitro: dye uptake experiments demonstrated that astroglial Cx43 hemichannels open in response to pilocarpine, and this was inhibited by TAT-Gap19. In vivo: TAT-Gap19 suppressed seizures and decreased D-serine concentrations; these effects were reversed by exogenous D-serine administration, and a similar effect was observed for the electrical stimulation model | [160] |

| In vitro experiments: Carbenoxolone (200 mM) quinine (100 mM) and La(NO3)3 (a blocker of Cx-based hemichannels) In vivo experiments: carbenoxolone (100 mg/kg) and quinine (40 mg/kg) | In vitro: low-Mg2+-induced epilepsy model In vivo: Wistar Albino Glaxo/ Rijswijk (WAG/Rij) rat model of absence epilepsy | Field potential recordings, evaluation of seizure-like events (SLEs) in hippocampal-entorhinal slices from Wistar rats (11–14 days old); epidural EEG (frontal and parietal cortex) in WAG/Rij rats (female, 11–12 months old, 195–210 g); recordings of bilaterally synchronous spike-wave discharges (SWDs) | Carbenoxolone prevented the occurrence of SLEs and aggravated seizures in non-convulsive absence epilepsy; quinine did not prevent SLEs but increased the number and total time of SWDs and decreased the length of the interictal intervals; La3+ completely abolished SLEs | [159] |

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Flores, C.E.; Nannapaneni, S.; Davidson, K.G.; Yasumura, T.; Bennett, M.V.; Rash, J.E.; Pereda, A.E. Trafficking of gap junction channels at a vertebrate electrical synapse in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, E573–E582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereda, A.E.; Curti, S.; Hoge, G.; Cachope, R.; Flores, C.E.; Rash, J.E. Gap junction-mediated electrical transmission: Regulatory mechanisms and plasticity. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2013, 1828, 134–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zancan, M.; Malysz, T.; Moura, D.J.; Morás, A.M.; Steffens, L.; Rasia-Filho, A.A. Gap junctions and expression of Cx36, Cx43 and Cx45 in the posterodorsal medial amygdala of adult rats. Histol. Histopathol. 2019, 9, 18160. [Google Scholar]

- Condorelli, D.F.; Mudò, G.; Trovato-Salinaro, A.; Mirone, M.B.; Amato, G.; Belluardo, N. Connexin-30 mRNA is up-regulated in astrocytes and expressed in apoptotic neuronal cells of rat brain following kainate-induced seizures. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2002, 21, 94–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghézali, G.; Vasile, F.; Curry, N.; Fantham, M.; Cheung, G.; Ezan, P.; Cohen-Salmon, M.; Kaminski, C.; Rouach, N. Neuronal Activity Drives Astroglial Connexin 30 in Perisynaptic Processes and Shapes Its Functions. Cereb. Cortex 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dermietzel, R.; Farooq, M.; Kessler, J.A.; Althaus, H.; Hertzberg, E.L.; Spray, D.C. Oligodendrocytes express gap junction proteins connexin32 and connexin45. Glia 1997, 20, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, J.I.; Ionescu, A.V.; Lynn, B.D.; Rash, J.E. Connexin29 and connexin32 at oligodendrocyte and astrocyte gap junctions and in myelin of the mouse central nervous system. J. Comp. Neurol. 2003, 464, 356–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrenis, K.; Chang, H.Y.; Pina-Benabou, M.H.; Woodroffe, A.; Lee, S.C.; Rozental, R.; Spray, D.C.; Scemes, E. Human and mouse microglia express connexin36, and functional gap junctions are formed between rodent microglia and neurons. J. Neurosci. Res. 2005, 82, 306–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajardo-Gómez, R.; Labra, V.C.; Orellana, J.A. Connexins and Pannexins: New Insights into Microglial Functions and Dysfunctions. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2016, 9, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, S.B.; Uy, B.; Perera, A.; Nicholson, L.F. AGEs-RAGE mediated up-regulation of connexin43 in activated human microglial CHME-5 cells. Neurochem. Int. 2012, 60, 640–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veenstra, R.D.; Wang, H.Z.; Beyer, E.C.; Brink, P.R. Selective dye and ionic permeability of gap junction channels formed by connexin 45. Circ. Res 1994, 75, 483–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukauskas, F.F. Neurons and β-cells of the pancreas express connexin36, forming gap junction channels that exhibit strong cationic selectivity. J. Membr. Biol. 2012, 245, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abudara, V.; Retamal, M.A.; Del Rio, R.; Orellana, J.A. Synaptic Functions of Hemichannels and Pannexons: A Double-Edged Sword. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2018, 11, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spray, D.C.; White, R.L.; Mazet, F.; Bennett, M.V. Regulation of gap junctional conductance. Am. J. Phys. 1985, 248, H753–H764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ek Vitorín, J.F.; Pontifex, T.K.; Burt, J.M. Determinants of Cx43 Channel Gating and Permeation: The Amino Terminus. Biophys. J. 2016, 110, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Velazquez, J.L.; Valiante, T.A.; Carlen, P.L. Modulation of gap junctional mechanisms during calcium-free induced field burst activity: A possible role for electrotonic coupling in epileptogenesis. J. Neurosci. 1994, 14, 4308–4317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Nieto, D.; Gómez-Hernández, J.M.; Larrosa, B.; Gutiérrez, C.; Muñoz, M.D.; Fasciani, I.; O’Brien, J.O.; Zappalà, A.; Cicirata, F.; Barrio, L.C. Regulation of neuronal connexin-36 channels by pH. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 17169–17174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimkute, L.; Kraujalis, T.; Snipas, M.; Palacios-Prado, N.; Jotautis, V.; Skeberdis, V.A.; Bukauskas, F.F. Modulation of Connexin-36 Gap Junction Channels by Intracellular pH and Magnesium Ions. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabo, T.M.; Caplan, J.S.; Zoran, M.J. Serotonin regulates electrical coupling via modulation of extrajunctional conductance: H-current. Brain Res. 2010, 1349, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivar, C.; Traub, R.D.; Gutiérrez, R. Mixed electrical-chemical transmission between hippocampal mossy fibers and pyramidal cells. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2012, 35, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasciani, I.; Pluta, P.; González-Nieto, D.; Martínez-Montero, P.; Molano, J.; Paíno, C.L.; Millet, O.; Barrio, L.C. Directional coupling of oligodendrocyte connexin-47 and astrocyte connexin-43 gap junctions. Glia 2018, 66, 2340–2352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bargiello, T.A.; Oh, S.; Tang, Q.; Bargiello, N.K.; Dowd, T.L.; Kwon, T. Gating of Connexin Channels by transjunctional-voltage: Conformations and models of open and closed states. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 2018, 1860, 22–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teubner, B.; Degen, J.; Söhl, G.; Guldenagel, M.; Bukauskas, F.E.; Trexler, E.B.; Verselis, V.K.; De Zeeuw, C.I.; Lee, C.G.; Kozak, C.A.; et al. Functional expression of the murine connexin 36 gene coding for a neuron-specific gap junctional protein. J. Membr. Biol. 2000, 176, 249–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivas, M.; Rozental, R.; Kojima, T.; Dermietzel, R.; Mehler, M.; Condorelli, D.F.; Kessler, J.A.; Spray, D.C. Functional properties of channels formed by the neuronal gap junction protein connexin 36. J. Neurosci. 1999, 19, 9848–9855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, G.; Akoum, N.; Appadurai, D.A.; Hayrapetyan, V.; Ahmed, O.; Martinez, A.D.; Beyer, E.C.; Moreno, A.P. Mono-Heteromeric Configurations of Gap Junction Channels Formed by Connexin43 and Connexin45 Reduce Unitary Conductance and Determine both Voltage Gating and Metabolic Flux Asymmetry. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuda, T.; Kosaka, T. Gap junctions linking the dendritic network of GABAergic interneurons in the hippocampus. J. Neurosci. 2000, 20, 1519–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baude, A.; Bleasdale, C.; Dalezios, Y.; Somogyi, P.; Klausberger, T. Immunoreactivity for the GABAA receptor α1 subunit, somatostatin and connexin36 distinguishes axoaxonic, basket, and bistratified interneurons of the rat hippocampus. Cereb. Cortex 2007, 17, 2094–2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zsiros, V.; Maccaferri, G. Noradrenergic modulation of electrical coupling in GABAergic networks of the hippocampus. J. Neurosci. 2008, 28, 1804–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, J.R.; Beierlein, M.; Connors, B.W. Functional properties of electrical synapses between inhibitory interneurons of neocortical layer 4. J. Neurophysiol. 2005, 93, 467–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancilla, J.G.; Lewis, T.J.; Pinto, D.J.; Rinzel, J.; Connors, B.W. Synchronization of electrically coupled pairs of inhibitory interneurons in neocortex. J. Neurosci. 2007, 27, 2058–2073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traub, R.D.; Whittington, M.A.; Buhl, E.H.; LeBeau, F.E.; Bibbig, A.; Boyd, S.; Cross, H.; Baldeweg, T. A possible role for gap junctions in generation of very fast EEG oscillations preceding the onset of, and perhaps initiating, seizures. Epilepsia 2001, 42, 153–170. [Google Scholar]

- Nagy, J.I. Evidence for connexin36 localization at hippocampal mossy fiber terminals suggesting mixed chemical/electrical transmission by granule cells. Brain Res. 2012, 1487, 107–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamzei-Sichani, F.; Davidson, K.G.V.; Yasumura, T.; Janssen, W.G.M.; Wearne, S.L.; Hof, P.R.; Traub, R.D.; Gutiérrez, R.; Ottersen, O.P.; Rash, J.E. Mixed electrical–chemical synapses in adult rat hippocampus are primarily glutamatergic and coupled by connexin-36. Front. Neuroanat. 2012, 6, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrientos, R.M.; Kitt, M.M.; Watkins, L.R.; Maier, S.F. Neuroinflammation in the normal aging hippocampus. Neuroscience 2015, 309, 84–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, M.G.; Weber, M.D.; Watkins, L.R.; Maier, S.F. Stress sounds the alarmin: The role of the danger-associated molecular pattern HMGB1 in stress-induced neuroinflammatory priming. Brain Behav. Immun. 2015, 48, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofroniew, M.V. Astrocyte barriers to neurotoxic inflammation. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2015, 16, 249–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kempuraj, D.; Thangavel, R.; Natteru, PA.; Selvakumar, GP.; Saeed, D.; Zahoor, H.; Zaheer, S.; Iyer, S.S.; Zaheer, A. Neuroinflammation Induces Neurodegeneration. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Spine 2016, 1, 1003. [Google Scholar]

- Reddy, D.S.; Kuruba, R. Experimental Models of Status Epilepticus and Neuronal Injury for Evaluation of Therapeutic Interventions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 18284–18318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ransohoff, R.M.; Schafer, D.; Vincent, A.; Blachère, N.E.; Bar-Or, A. Neuroinflammation: Ways in Which the Immune System Affects the Brain. Neurotherapeutics 2015, 12, 896–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabab, T.; Khanabdali, R.; Moghadamtousi, S.Z.; Kadir, H.A.; Mohan, G. Neuroinflammation pathways: A general review. Int. J. Neurosci. 2017, 127, 624–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagberg, H.; Mallard, C.; Ferriero, D.M.; Vannucci, S.J.; Levison, S.W.; Vexler, Z.S.; Gressens, P. The role of inflammation in perinatal brain injury. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2015, 11, 192–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, B.Z.; Xu, Z.Q.; Han, B.Z.; Su, D.F.; Liu, C. NLRP3 inflammasome and its inhibitors: A review. Front. Pharmacol. 2015, 6, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vezzani, A.; Balosso, S.; Ravizza, T. Neuroinflammatory pathways as treatment targets and biomarkers in epilepsy. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2019, 15, 459–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Buisman-Pijlman, F.; Hutchinson, M.R. Toll-like receptor 4: Innate immune regulator of neuroimmune and neuroendocrine interactions in stress and major depressive disorder. Front. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, C.J.; Massie, A.; De Keyser, J. Immune players in the CNS: The astrocyte. J. Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2013, 8, 824–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, A.K.; Kavelaars, A.; Heijnen, C.J.; Dantzer, R. Neuroinflammation and comorbidity of pain and depression. Pharmacol. Rev. 2014, 66, 80–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montero, T.D.; Orellana, J.A. Hemichannels: New pathways for gliotransmitter release. Neuroscience 2015, 286, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Retamal, M.A.; Froger, N.; Palacios-Prado, N.; Ezan, P.; Sáez, P.J.; Sáez, J.C.; Giaume, C. Cx43 hemichannels and gap junction channels in astrocytes are regulated oppositely by proinflammatory cytokines released from activated microglia. J. Neurosci. 2007, 27, 13781–13792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locovei, S.; Wang, J.; Dahl, G. Activation of pannexin 1 channels by ATP through P2Y receptors and by cytoplasmic calcium. FEBS Lett. 2006, 580, 239–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baroja-Mazo, A.; Barberà-Cremades, M.; Pelegrín, P. The participation of plasma membrane hemichannels to purinergic signaling. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 2013, 1828, 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovegno, M.; Saez, J.C. Role of astrocyte connexin hemichannels in cortical spreading depression. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 2018, 1860, 216–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Vuyst, E.; Decrock, E.; De Bock, M.; Yamasaki, H.; Naus, C.C.; Evans, W.H.; Leybaert, L. Connexin hemichannels and gap junction channels are differentially influenced by lipopolysaccharide and basic fibroblast growth factor. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2007, 18, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mallard, C.; Davidson, J.O.; Tan, S.; Green, C.R.; Bennet, L.; Robertson, N.J.; Gunn, A.J. Astrocytes and microglia in acute cerebral injury underlying cerebral palsy associated with preterm birth. Pediatr. Res. 2014, 75, 234–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hung, S.C.; Choi, C.H.; Said-Sadier, N.; Johnson, L.; Atanasova, K.R.; Sellami, H.; Yilmaz, O.; Ojcius, D.M. P2X4 assembles with P2X7 and pannexin-1 in gingival epithelial cells and modulates ATP-induced reactive oxygen species production and inflammasome activation. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e70210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutterwala, F.S.; Haasken, S.; Cassel, S.L. Mechanism of NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2014, 1319, 82–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gombault, A.; Baron, L.; Couillin, I. ATP release and purinergic signaling in NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Front. Immunol. 2012, 3, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, T.; Ockinger, J.; Yu, J.; Byles, V.; McColl, A.; Hofer, A.M.; Horng, T. Critical role for calcium mobilization in activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 11282–11287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riteau, N.; Baron, L.; Villeret, B.; Guillou, N.; Savigny, F.; Ryffel, B.; Rassendren, F.; Le Bert, M.; Gombault, A.; Couillin, I. ATP release and purinergic signaling: A common pathway for particle-mediated inflammasome activation. Cell Death Dis. 2012, 3, e403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, M.D.; Frank, M.G.; Tracey, K.J.; Watkins, L.R.; Maier, S.F. Stress induces the danger-associated molecular pattern HMGB-1 in the hippocampus of male Sprague Dawley rats: A priming stimulus of microglia and the NLRP3 inflammasome. J. Neurosci. 2015, 35, 316–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, J.; Crews, F. Glutamate/NMDA excitotoxicity and HMGB1/TLR4 neuroimmune toxicity converge as components of neurodegeneration. AIMS Public Health 2015, 2, 77–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, W.R.; de Rivero Vaccari, J.P.; Locovei, S.; Qiu, F.; Carlsson, S.K.; Scemes, E.; Keane, R.W.; Dahl, G. The pannexin 1 channel activates the inflammasome in neurons and astrocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 18143–18151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liddelow, S.A.; Barres, B.A. Reactive astrocytes: Production, Function, and Therapeutic Potential. Immunity 2017, 46, 957–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allnoch, L.; Baumgärtner, W.; Hansmann, F. Impact of Astrocyte Depletion upon Inflammation and Demyelination in a Murine Animal Model of Multiple Sclerosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sofroniew, M.V.; Vinters, H.V. Astrocytes: Biology and pathology. Acta Neuropathol. 2010, 119, 7–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ludwin, S.K.; Rao, V.; Moore, C.S.; Antel, J.P. Astrocytes in multiple sclerosis. Mult. Scler. J. 2016, 22, 1114–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liddelow, S.A.; Guttenplan, K.A.; Clarke, L.E.; Bennett, F.C.; Bohlen, C.J.; Schirmer, L.; Bennett, M.L.; Munch, A.E.; Chung, W.S.; Peterson, T.C. Neurotoxic reactive astrocytes are induced by activated microglia. Nature 2017, 541, 481–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herz, J.; Filiano, A.J.; Smith, A.; Yogev, N.; Kipnis, J. Myeloid Cells in the Central Nervous System. Immunity 2017, 46, 943–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, R.S.; Hunter, C.A. Protective and Pathological Immunity during Central Nervous System Infections. Immunity 2017, 46, 891–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamanian, J.L.; Xu, L.; Foo, L.C.; Nouri, N.; Zhou, L.; Giffard, R.G.; Barres, B.A. Genomic Analysis of Reactive Astrogliosis. J. Neurosci. 2012, 32, 6391–6410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heppner, F.L.; Ransohoff, R.M.; Becher, B. Immune attack: The role of inflammation in Alzheimer disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2015, 16, 358–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sáez, J.C.; Schalper, K.A.; Retamal, M.A.; Orellana, J.A.; Shoji, K.F.; Bennett, M.V. Cell membrane permeabilization via connexin hemichannels in living and dying cells. Exp. Cell Res. 2010, 316, 2377–2389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bezzi, P.; Volterra, A. A neuron-glia signalling network in the active brain. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2001, 11, 387–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M.A.; Burda, J.E.; Ren, Y.; Ao, Y.; O’Shea, T.M.; Kawaguchi, R.; Coppola, G.; Khakh, B.S.; Deming, T.J.; Sofroniew, M.V. Astrocyte scar formation aids CNS axon regeneration. Nature 2016, 532, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Kang, N.; Lovatt, D.; Torres, A.; Zhao, Z.; Lin, J.; Nedergaard, M. Connexin 43 Hemichannels Are Permeable to ATP. J. Neurosci. 2008, 28, 4702–4711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lian, H.; Yang, L.; Cole, A.; Sun, L.; Chiang, A.C.-A.; Fowler, S.W.; Shim, D.J.; Rodriguez-Rivera, J.; Taglialatela, G.; Jankowsky, J.L.; et al. NFκB-activated Astroglial Release of Complement C3 Compromises Neuronal Morphology and Function Associated with Alzheimer’s Disease. Neuron 2015, 85, 101–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Pei, S.; Han, L.; Guo, B.; Li, Y.; Duan, R.; Yao, Y.; Xue, B.; Chen, X.; Jia, Y. Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes Reduce A1 Astrocytes via Downregulation of Phosphorylated NFκB P65 Subunit in Spinal Cord Injury. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2018, 50, 1535–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Qin, H.; Chen, J.; Mou, L.; He, Y.; Yan, Y.; Zhou, H.; Lv, Y.; Chen, Z.; Wang, J.; et al. Postnatal activation of TLR4 in astrocytes promotes excitatory synaptogenesis in hippocampalneurons. J. Cell Biol. 2016, 215, 719–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papaneophytou, C.; Georgiou, E.; Kleopa, K.A. The role of oligodendrocyte gap junctions in neuroinflammation. Channels 2019, 13, 247–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Río-Hortega, P. Son homologables la glía de escasas radiaciones y la celuladeSchwann. Bol. Soc. Esp. Biol. 1922, 10, 25–28. [Google Scholar]

- Battefeld, A.; Klooster, J.; Kole, M.H. Myelinating satellite oligodendrocytes are integrated in a glial syncytium constraining neuronal high-frequency activity. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 11298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philips, T.; Rothstein, J.D. Oligodendroglia: Metabolic supporters of neurons. J. Clin. Investig. 2017, 127, 3271–3280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magnotti, L.M.; Goodenough, D.A.; Paul, D.L. Deletion of oligodendrocyte Cx32 and astrocyte Cx43 causeswhite matter vacuolation, astrocyte loss and early mortality. Glia 2011, 59, 1064–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vejar, S.; Oyarzún, J.E.; Retamal, M.A.; Ortiz, F.C.; Orellana, J.A. Connexin and Pannexin-Based Channels in Oligodendrocytes: Implications in Brain Health and Disease. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Georgiou, E.; Sidiropoulou, K.; Richter, J. Gene therapy targeting oligodendrocytes provides therapeutic benefit in a leukodystrophy model. Brain 2017, 140, 599–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawson, L.J.; Perry, V.H.; Dri, P.; Gordon, S. Heterogeneity in the distribution and morphology of microglia in the normal adult mouse brain. Neuroscience 1990, 39, 151–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kettenmann, H.; Hanisch, U.K.; Noda, M.; Verkhratsky, A. Physiology of Microglia. Physiol. Rev. 2011, 91, 461–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brionne, T.C.; Tesseur, I.; Masliah, E.; Wyss-Coray, T. Loss of TGF-beta 1 leads to increased neuronal cell death and microgliosis in mouse brain. Neuron 2003, 40, 1133–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basilico, B.; Pagani, F.; Grimaldi, A.; Cortese, B.; Di Angelantonio, S.; Weinhard, L.; Gross, C.; Limatola, C.; Maggi, L.; Ragozzino, D. Microglia shape presynaptic properties at developing glutamatergic synapses. Glia 2019, 67, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Dissing-Olesen, L.; MacVicar, B.A.; Stevens, B. Microglia: Dynamic Mediators of Synapse Development and Plasticity. Trends Immunol. 2015, 36, 605–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schafer, D.P.; Lehrman, E.K.; Stevens, B. “quad-partite” synapse: Microglia-synapse interactions in the developing and mature CNS. Glia 2013, 61, 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wake, H.; Moorhouse, A.J.; Miyamoto, A.; Nabekura, J. Microglia: Actively surveying and shaping neuronal circuit structure and function. Trends Neurosci. 2013, 36, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ikegami, A.; Haruwaka, K.; Wake, H. Microglia: Lifelong modulator of neural circuits. Neuropathology 2019, 39, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maezawa, I.; Jin, L.W. Rett Syndrome Microglia Damage Dendrites and Synapses by the Elevated Release of Glutamate. J. Neurosci. 2010, 30, 5346–5356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parenti, R.; Campisi, A.; Vanella, A.; Cicirata, F. Immunocytochemical and RT-PCR analysis of connexin36 in cultures of mammalian glial cells. Arch. Ital. Biol. 2002, 140, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Belousov, A.B.; Nishimune, H.; Denisova, J.V.; Fontes, J.D. A potential role for neuronal connexin 36 in the pathogenesis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurosci. Lett. 2018, 666, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richter, N.; Wendt, S.; Georgieva, P.B.; Hambardzumyan, D.; Nolte, C.; Kettenmann, H. Glioma-associated microglia and macrophages/monocytes display distinct electrophysiological properties and do not communicate via gap junctions. Neurosci. Lett. 2014, 583, 130–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rouach, N.; Avignone, E.; Même, W.; Koulakoff, A.; Venance, L.; Blomstrand, F.; Giaume, C. Gap junctions and connexin expression in the normal and pathological central nervous system. Biol. Cell 2002, 94, 457–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sáez, P.J.; Shoji, K.F.; Retamal, M.A.; Harcha, P.A.; Ramírez, G.; Jiang, J.X.; von Bernhardi, R.; Sáez, J.C. ATP is required and advances cytokine-induced gap junction formation in microglia in vitro. Mediat. Inflamm. 2013, 2013, 216402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaikwad, S.; Patel, D.; Agrawal-Rajput, R. CD40 Negatively Regulates ATP-TLR4-Activated Inflammasome in Microglia. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 2017, 37, 351–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bona, E.; Andersson, A.L.; Blomgren, K.; Gilland, E.; Puka-Sundvall, M.; Gustafson, K.; Hagberg, H. Chemokine and Inflammatory Cell Response to Hypoxia-Ischemia in Immature Rats. Pediatr. Res. 1999, 45, 500–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, M.; Manzanero, J.S.; Borges, K. Complex alterations in microglial M1/M2 markers during the development of epilepsy in two mouse models. Epilepsia 2015, 56, 895–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, S.A.; Boddeke, H.W.; Kettenmann, H. Microglia in Physiology and Disease. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2017, 79, 619–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, H.; Jin, S.; Wang, J.; Zhang, G.; Kawanokuchi, J.; Kuno, R.; Sonobe, Y.; Mizuno, T.; Suzumura, A. Tumor Necrosis Factor-α Induces neurotoxicity via Glutamate Release from Hemichannels of Activated Microglia in an Autocrine Manner. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 21362–21368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orellana, J.A.; Froger, N.; Ezan, P.; Jiang, J.X.; Bennett, M.V.; Naus, C.C.; Giaume, C.; Sáez, J.C. ATP and glutamate released via astroglial connexin 43 hemichannels mediate neuronal death through activation of pannexin 1 hemichannels. J. Neurochem. 2011, 118, 826–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domercq, M.; Perez-Samartin, A.; Aparicio, D.; Alberdi, E.; Pampliega, O.; Matute, C. P2X7 receptors mediate ischemic damage to oligodendrocytes. Glia 2010, 58, 730–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, T.; Alves, M.; Sheedy, C.; Henshall, D.C. ATPergic signalling during seizures and epilepsy. Neuropharmacology 2016, 104, 140–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, L.; Gombault, A.; Fanny, M.; Villeret, B.; Savigny, F.; Guillou, N.; Panek, C.; Le Bert, M.; Lagente, V.; Rassendren, F.; et al. The NLRP3 inflammasome is activated by nanoparticles through ATP, ADP and adenosine. Cell Death Dis. 2015, 6, e1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heneka, M.T.; McManus, R.M.; Latz, E. Inflammasome signalling in brain function and neurodegenerative disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2018, 19, 610–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voet, S.; Srinivasan, S.; Lamkanfi, M.; van Loo, G. Inflammasomes in neuroinflammatory and neurodegenerative diseases. EMBO Mol. Med. 2019, 11, e10248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, S.; Wan, D.; Fan, Y.; Liu, S.; Sun, K.; Huo, J.; Zhang, P.; Li, X.; Xie, X.; Wang, F.; et al. Amentoflavone Affects Epileptogenesis and Exerts Neuroprotective Effects by Inhibiting NLRP3 Inflammasome. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapia, R.; Medina-Ceja, L.; Peña, F. Action of 4-aminopyridine on extracellular amino acids in hippocampus and entorhinal cortex: A dual microdialysis and electroencehalographic study in awake rats. Brain Res. Bull. 2000, 53, 255–262. [Google Scholar]

- Condorelli, D.F.; Conti, F.; Gallo, V.; Kirchhoff, F.; Seifert, G.; Steinhauser, C.; Verkhratsky, A.; Yuan, X. Expression and functional analysis of glutamate receptors in glial cells. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1999, 468, 49–67. [Google Scholar]

- Seifert, G.; Steinhauser, C. Ionotropic glutamate receptors in astrocytes. Prog. Brain Res. 2001, 132, 287–299. [Google Scholar]

- Verkhratsky, A.; Kirchhoff, F. Glutamate-mediated neuronal-glial transmission. J. Anat. 2007, 210, 651–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamzei-Sichani, F.; Kamasawa, N.; Janssen, W.G.; Yasumura, T.; Davidson, K.G.; Hof, P.R.; Wearne, S.L.; Stewart, M.G.; Young, S.R.; Whittington, M.A.; et al. Gap junctions on hippocampal mossy fiber axons demonstrated by thin-section electron microscopy and freeze fracture replica immunogold labeling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 12548–12553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traub, R.D.; Draguhn, A.; Whittington, M.A.; Baldeweg, T.; Bibbig, A.; Buhl, E.H.; Schmitz, D. Axonal gap junctions between principal neurons: A novel source of network oscillations, and perhaps epileptogenesis. Rev. Neuroci. 2002, 13, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traub, R.D.; Whittington, M.A.; Gutiérrez, R.; Draguhn, A. Electrical coupling between hippocampal neurons: Contrasting roles of principal cell gap junctions and interneuron gap junctions. Cell Tissue Res. 2018, 373, 671–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathy, A.; Clark, B.A.; Häusser, M. Synaptically induced long-term modulation of electrical coupling in the inferior olive. Neuron 2014, 81, 1290–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turecek, J.; Yuen, G.S.; Han, V.Z.; Zeng, X.H.; Bayer, K.U.; Welsh, J.P. NMDA receptor activation strengthens weak electrical coupling in mammalian brain. Neuron 2014, 81, 1375–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Siesjö, B.K.; von Hanwehr, R.; Nergelius, G.; Nevander, G.; Ingvar, M. Extra- and intracellular pH in the brain during seizures and in the recovery period following the arrest of seizure activity. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 1985, 5, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schalper, K.A.; Sánchez, H.A.; Lee, S.C.; Altenberg, G.A.; Nathanson, M.H.; Sáez, J.C. Connexin 43 hemichannels mediate the Ca2+ influx induced by extracellular alkalinization. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2010, 299, C1504–C1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios-Prado, N.; Briggs, S.W.; Skeberdis, V.A.; Pranevicius, M.; Bennett, M.V.; Bukauskas, F.F. pH-dependent modulation of voltage gating in connexin45 homotypic and connexin45/connexin43 heterotypic gap junctions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 9897–9902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pogoda, K.; Kameritsch, P.; Retamal, M.A.; Vega, J.L. Regulation of gap junction channels and hemichannels by phosphorylation and redox changes: A revision. BMC Cell Biol. 2016, 17 (Suppl. 1), 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garciarena, C.D.; Malik, A.; Swietach, P.; Moreno, A.P.; Vaughan-Jones, R.D. Distinct moieties underlie biphasic H+ gating of connexin43 channels, producing a pH optimum for intercellular communication. FASEB J. 2018, 32, 1969–1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajda, Z.; Szupera, Z.; Blazsó, G.; Szente, M. Quinine, a blocker of neuronal cx36 channels, suppresses seizure activity in rat neocortex in vivo. Epilepsia 2005, 46, 1581–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsen, K.E.; Kelso, A.R.; Cock, H.R. Antiepileptic effect of gap-junction blockers in a rat model of refractory focal cortical epilepsy. Epilepsia 2006, 47, 1169–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bostanci, M.O.; Bağirici, F. Anticonvulsive effects of carbenoxolone on penicillin-induced epileptiform activity: An in vivo study. Neuropharmacology 2007, 52, 362–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina-Ceja, L.; Cordero-Romero, A.; Morales-Villagrán, A. Antiepileptic effect of carbenoxolone on seizures induced by 4-aminopyridine: A study in the rat hippocampus and entorhinal cortex. Brain Res. 2008, 1187, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina-Ceja, L.; Ventura-Mejía, C. Differential effects of trimethylamine and quinine on seizures induced by 4-aminopyridine administration in the entorhinal cortex of vigilant rats. Seizure 2010, 19, 507–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Gao, Z.; Ni, Y.; Dai, Z. Carbenoxolone pretreatment and treatment of posttraumatic epilepsy. Neural Regen. Res. 2013, 8, 169–176. [Google Scholar]

- Sefil, F.; Arık, A.E.; Acar, M.D.; Bostancı, M.Ö.; Bagirici, F.; Kozan, R. Interaction between carbenoxolone and valproic acid on pentylenetetrazole kindling model of epilepsy. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 2015, 8, 10508–10514. [Google Scholar]

- Franco-Pérez, J.; Manjarrez-Marmolejo, J.; Rodríguez-Balderas, C.; Castro, N.; Ballesteros-Zebadua, P. Quinine and carbenoxolone enhance the anticonvulsant activity of some classical antiepileptic drugs. Neurol. Res. 2018, 40, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szente, M.; Gajda, Z.; Said, A.K.; Hermesz, E. Involvement of electrical coupling in the in vivo ictal epileptiform activity induced by 4-aminopyridine in the neocortex. Neuroscience 1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, J.S.; Baumgarten, I.M. Glycyrrhetinic acid derivatives: A novel class of inhibitors of gap-junctional intercellular communication. Structure-activity relationships. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1988, 246, 1104–1107. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg, G.S.; Moreno, A.P.; Bechberger, J.F.; Hearn, S.S.; Shivers, R.R.; MacPhee, D.J.; Zhang, Y.C.; Naus, C.C. Evidence that disruption of connexon particle arrangements in gap junction plaques is associated with inhibition of gap junctional communication by a glycyrrhetinic acid derivative. Exp. Cell Res. 1996, 222, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, X.; Wilson, S.; Schlender, K.K.; Ruch, R.J. Gap-junction disassembly and connexin 43 dephosphorylation induced by 18 beta-glycyrrhetinic acid. Mol. Carcinog. 1996, 16, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Feng, L.; Ma, D.; Yin, P.; Wang, X.; Hou, S.; Hao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Xin, M.; Feng, J. Roles of astrocytic connexin-43, hemichannels, and gap junctions in oxygen-glucose deprivation/reperfusion injury induced neuroinflammation and the possible regulatory mechanisms of salvianolic acid B and carbenoxolone. J. Neuroinflamm. 2018, 15, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walden, J.; Speckmann, E.J. Effects of quinine on membrane potential and membrane currents in identified neurons of Helix pomatia. Neurosci. Lett. 1981, 27, 139–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherubini, E.; North, R.A.; Surprenant, A. Quinine blocks a calcium-activated potassium conductance in mammalian enteric neurones. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1984, 83, 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivas, M.; Hopperstad, M.G.; Spray, D.C. Quinine blocks specific gap junction channel subtypes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 10942–10947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, L.; Xue, Y.; Jones, M.; Heinbockel, T.; Ying, M.; Zhan, X. The Effects of Quinine on Neurophysiological Properties of Dopaminergic Neurons. Neurotox. Res. 2018, 34, 62–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, A.J.; Lummis, S.C. Antimalarial drugs inhibit human 5-HT(3) and GABA(A) but not GABA(C) receptors. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2008, 153, 1686–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coker, S.J.; Batey, A.J.; Lightbown, I.D.; Díaz, M.E.; Eisner, D.A. Effects of mefloquine on cardiac contractility and electrical activity in vivo, in isolated cardiac preparations, and in single ventricular myocytes. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2000, 129, 323–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heshmati, M.; Golden, S.A.; Pfau, M.L.; Christoffel, D.J.; Seeley, E.L.; Cahill, M.E.; Khibnik, L.A.; Russo, S.J. Mefloquine in the nucleus accumbens promotes social avoidance and anxiety-like behavior in mice. Neuropharmacology 2016, 101, 351–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, W.H.; Bultynck, G.; Leybaert, L. Manipulating connexin communication channels: Use of peptidomimetics and the translational outputs. J. Membr. Biol. 2012, 245, 437–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samoilova, M.; Wentlandt, K.; Adamchik, Y.; Velumian, A.A.; Carlen, P.L. Connexin 43 mimetic peptides inhibit spontaneous epileptiform activity in organotypic hippocampal slice cultures. Exp. Neurol. 2008, 210, 762–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, J.J.; Green, C.R.; O’Carroll, S.J.; Nicholson, L.F. Dose dependent protective effect of connexin43 mimetic peptide against neurodegeneration in an ex vivo model of epileptiform lesion. Epilepsy Res. 2010, 92, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bragin, A.; Wilson, C.L.; Engel, J., Jr. Chronic epileptogenesis requires development of a network of pathologically interconnected neuron clusters: A hypothesis. Epilepsia 2000, 41 (Suppl. 6), S144–S152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bragin, A.; Mody, I.; Wilson, C.L.; Engel, J., Jr. Local generation of fast ripples in epileptic brain. J. Neurosci. 2002, 22, 2012–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventura-Mejía, C.; Medina-Ceja, L. Decreased fast ripples in the hippocampus of rats with spontaneous recurrent seizures treated with carbenoxolone and quinine. BioMed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 282490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, X.; Xiang, J.; Song, P.P.; Jiang, L.; Liu, B.K.; Hu, Y. Effects of gap junctions blockers on fast ripples and connexin in rat hippocampi after status epilepticus. Epilepsy Res. 2018, 146, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, A.; Traub, R.D.; Vladimirov, N.; Jenkins, A.; Nicholson, C.; Whittaker, R.G.; Schofield, I.; Clowry, G.J.; Cunningham, M.O.; Whittington, M.A. Gap junction networks can generate both ripple-like and fast ripple-like oscillations. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2014, 39, 46–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gigout, S.; Louvel, J.; Kawasaki, H.; D’Antuono, M.; Armand, V.; Kurcewicz, I.; Olivier, A.; Laschet, J.; Turak, B.; Devaux, B.; et al. Effects of gap junction blockers on human neocortical synchronization. Neurobiol. Dis. 2006, 22, 496–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolic, L.; Shen, W.; Nobili, P.; Virenque, A.; Ulmann, L.; Audinat, E. Blocking TNFα-driven astrocyte purinergic signaling restores normal synaptic activity during epileptogenesis. Glia 2018, 66, 2673–2683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Denisova, J.V.; Kang, K.S.; Fontes, J.D.; Zhu, B.T.; Belousov, A.B. Neuronal gap junctions are required for NMDA receptor-mediated excitotoxicity: Implications in ischemic stroke. J. Neurophysiol. 2010, 104, 3551–3556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Fellin, T.; Pascual, O.; Gobbo, S.; Pozzan, T.; Haydon, P.G.; Carmignoto, G. Neuronal synchrony mediated by astrocytic glutamate through activation of extrasynaptic NMDA receptors. Neuron 2004, 43, 729–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, L.; Yang, T.; Cui, S.; Chen, G. Connexin hemichannels in astrocytes: Role in CNS disorders. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2019, 12, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouach, N.; Koulakoff, A.; Abudara, V.; Willecke, K.; Giaume, C. Astroglial metabolic networks sustain hippocampal synaptic transmission. Science 2008, 322, 1551–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincze, R.; Péter, M.; Szabó, Z.; Kardos, J.; Héja, L.; Kovács, Z. Connexin 43 Differentially Regulates Epileptiform Activity in Models of Convulsive and Non-convulsive Epilepsies. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walrave, L.; Pierre, A.; Albertini, G.; Aourz, N.; De Bundel, D.; Van Eeckhaut, A.; Vinken, M.; Giaume, C.; Leybaert, L.; Smolders, I. Inhibition of astroglial connexin 43 hemichannels with TAT-Gap19 exerts anticonvulsant effects in rodents. Glia 2018, 66, 1788–1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Medina-Ceja, L.; Salazar-Sánchez, J.C.; Ortega-Ibarra, J.; Morales-Villagrán, A. Connexins-Based Hemichannels/Channels and Their Relationship with Inflammation, Seizures and Epilepsy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 5976. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20235976

Medina-Ceja L, Salazar-Sánchez JC, Ortega-Ibarra J, Morales-Villagrán A. Connexins-Based Hemichannels/Channels and Their Relationship with Inflammation, Seizures and Epilepsy. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2019; 20(23):5976. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20235976

Chicago/Turabian StyleMedina-Ceja, Laura, Juan C. Salazar-Sánchez, Jorge Ortega-Ibarra, and Alberto Morales-Villagrán. 2019. "Connexins-Based Hemichannels/Channels and Their Relationship with Inflammation, Seizures and Epilepsy" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 20, no. 23: 5976. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20235976

APA StyleMedina-Ceja, L., Salazar-Sánchez, J. C., Ortega-Ibarra, J., & Morales-Villagrán, A. (2019). Connexins-Based Hemichannels/Channels and Their Relationship with Inflammation, Seizures and Epilepsy. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 20(23), 5976. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20235976