Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor-A Exerts Diverse Cellular Effects via Small G Proteins, Rho and Rap

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Relationship between VEGF-A–VEGF Receptor-2 Signaling and Rho Family Small G Proteins in Endothelial Cells

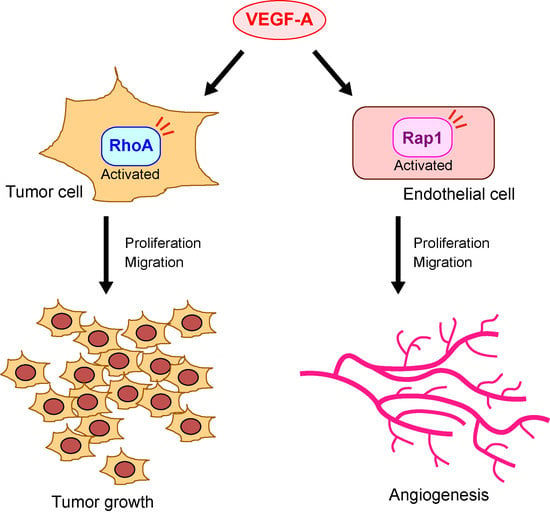

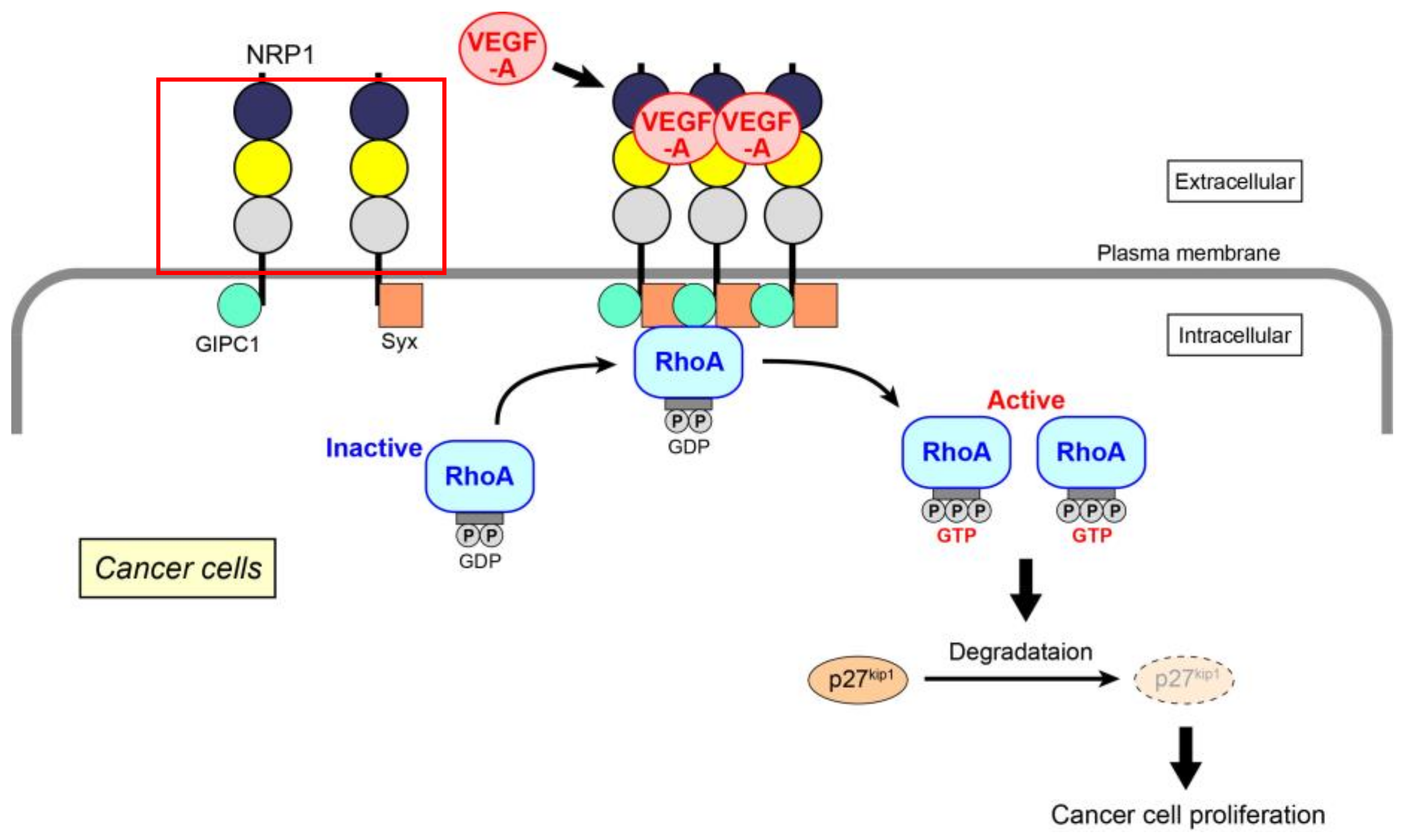

3. Pathological Implications of VEGF-A-Induced Rho Activation

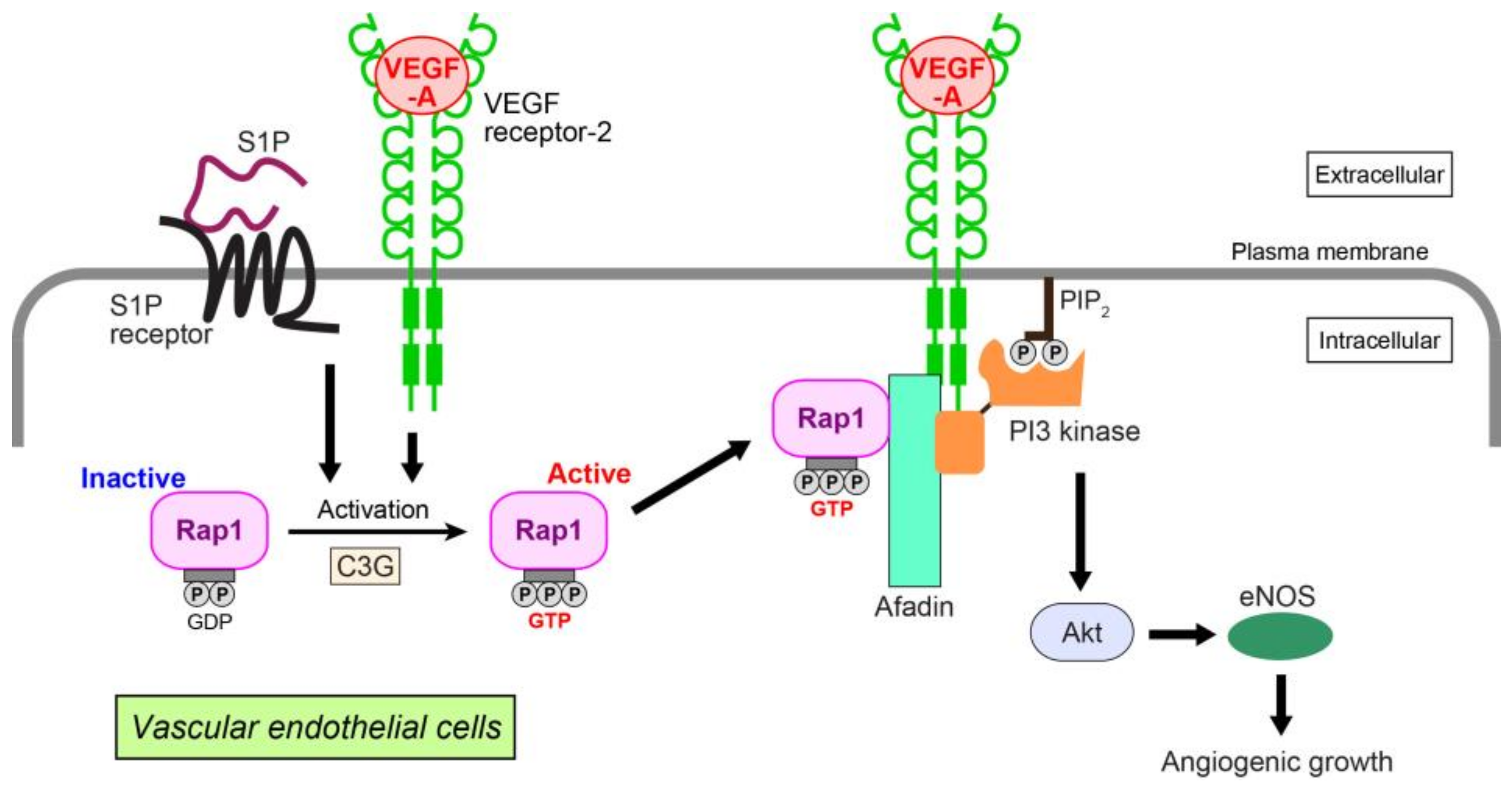

4. VEGF-A-Induced Functions of Rap in Angiogenesis

5. Mode of Association between VEGF-A and Rap1 at the Molecular Level

6. VEGF-A and Rap1 in Pathological Conditions

7. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| VEGF | vascular endothelial growth factor |

| PlGF | placental growth factor |

| Rho | Ras homologue gene |

| Rap | Ras-related protein |

| ERK | extracellular signal-regulated kinase |

| PI3 | phosphoinositide-3 |

| PIP3 | phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-trisphosphate |

| eNOS | endothelial nitric oxide synthase |

| MAP | mitogen-activated protein |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| ROCK | Rho kinase |

| MLC | myosin light chain |

| NRP | neuropilin |

| GEF | guanine nucleotide exchange factor |

| FGF | fibroblast growth factor |

| S1P | sphingosine 1-phosphate |

| HUVEC | human umbilical vein endothelial cell |

| CCM | cerebral cavernous malformation |

References

- Chung, A.S.; Ferrara, N. Developmental and pathological angiogenesis. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2011, 27, 563–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simons, M.; Gordon, E.; Claesson-Welsh, L. Mechanisms and regulation of endothelial VEGF receptor signalling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2016, 17, 611–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrara, N.; Carver-Moore, K.; Chen, H.; Dowd, M.; Lu, L.; O’Shea, K.S.; Powell-Braxton, L.; Hillan, K.J.; Moore, M.W. Heterozygous embryonic lethality induced by targeted inactivation of the VEGF gene. Nature 1996, 380, 439–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carmeliet, P.; Ferreira, V.; Breier, G.; Pollefeyt, S.; Kieckens, L.; Gertsenstein, M.; Fahrig, M.; Vandenhoeck, A.; Harpal, K.; Eberhardt, C.; et al. Abnormal blood vessel development and lethality in embryos lacking a single VEGF allele. Nature 1996, 380, 435–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanahan, D.; Folkman, J. Patterns and emerging mechanisms of the angiogenic switch during tumorigenesis. Cell 1996, 86, 353–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerbel, R.; Folkman, J. Clinical translation of angiogenesis inhibitors. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2002, 2, 727–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shibuya, M. Vascular endothelial growth factor and its receptor system: Physiological functions in angiogenesis and pathological roles in various diseases. J. Biochem. 2013, 153, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van der Meel, R.; Symons, M.H.; Kudernatsch, R.; Kok, R.J.; Schiffelers, R.M.; Storm, G.; Gallagher, W.M.; Byrne, A.T. The VEGF/Rho GTPase signalling pathway: A promising target for anti-angiogenic/anti-invasion therapy. Drug Discov. Today 2011, 16, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heasman, S.J.; Ridley, A.J. Mammalian Rho GTPases: New insights into their functions from in vivo studies. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008, 9, 690–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loirand, G.; Sauzeau, V.; Pacaud, P. Small G proteins in the cardiovascular system: Physiological and pathological aspects. Physiol. Rev. 2013, 93, 1659–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rojas, A.M.; Fuentes, G.; Rausell, A.; Valencia, A. The Ras protein superfamily: Evolutionary tree and role of conserved amino acids. J. Cell Biol. 2012, 196, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cross, M.J.; Dixelius, J.; Matsumoto, T.; Claesson-Welsh, L. VEGF-receptor signal transduction. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2003, 28, 488–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, T.; Ueno, H.; Shibuya, M. VEGF activates protein kinase C-dependent, but Ras-independent Raf-MEK-MAP kinase pathway for DNA synthesis in primary endothelial cells. Oncogene 1999, 18, 2221–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerber, H.P.; McMurtrey, A.; Kowalski, J.; Yan, M.; Keyt, B.A.; Dixit, V.; Ferrara, N. Vascular endothelial growth factor regulates endothelial cell survival through the phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase/Akt signal transduction pathway. Requirement for Flk-1/KDR activation. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 30336–30343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daher, Z.; Boulay, P.L.; Desjardins, F.; Gratton, J.P.; Claing, A. Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 activates ADP-ribosylation factor 1 to promote endothelial nitric-oxide synthase activation and nitric oxide release from endothelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 24591–24599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, T.; Yamaguchi, S.; Chida, K.; Shibuya, M. A single autophosphorylation site on KDR/Flk-1 is essential for VEGF-A-dependent activation of PLC-γ and DNA synthesis in vascular endothelial cells. EMBO J. 2001, 20, 2768–2778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eliceiri, B.P.; Paul, R.; Schwartzberg, P.L.; Hood, J.D.; Leng, J.; Cheresh, D.A. Selective requirement for Src kinases during VEGF-induced angiogenesis and vascular permeability. Mol. Cell 1999, 4, 915–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, J.H.; Claesson-Welsh, L. VEGF-induced activation of phosphoinositide 3-kinase is dependent on focal adhesion kinase. Exp. Cell Res. 2001, 263, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rousseau, S.; Houle, F.; Landry, J.; Huot, J. p38 MAP kinase activation by vascular endothelial growth factor mediates actin reorganization and cell migration in human endothelial cells. Oncogene 1997, 15, 2169–2177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Q.; Rounds, S. Focal adhesion kinase and endothelial cell apoptosis. Microvasc. Res. 2012, 83, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nuche-Berenguer, B.; Ramos-Álvarez, I.; Jensen, R.T. The p21-activated kinase, PAK2, is important in the activation of numerous pancreatic acinar cell signaling cascades and in the onset of early pancreatitis events. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2016, 1862, 1122–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabbatini, M.; Santillo, M.; Pisani, A.; Paternò, R.; Uccello, F.; Serù, R.; Matrone, G.; Spagnuolo, G.; Andreucci, M.; Serio, V.; et al. Inhibition of Ras/ERK1/2 signaling protects against postischemic renal injury. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2006, 290, F1408–F1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witte, D.; Bartscht, T.; Kaufmann, R.; Pries, R.; Settmacher, U.; Lehnert, H.; Ungefroren, H. TGF-β1-induced cell migration in pancreatic carcinoma cells is RAC1 and NOX4-dependent and requires RAC1 and NOX4-dependent activation of p38 MAPK. Oncol. Rep. 2017, 38, 3693–3701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bates, D.O. Vascular endothelial growth factors and vascular permeability. Cardiovasc. Res. 2010, 87, 262–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beckers, C.M.; van Hinsbergh, V.W.; van Nieuw Amerongen, G.P. Driving Rho GTPase activity in endothelial cells regulates barrier integrity. Thromb. Haemost. 2010, 103, 40–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eriksson, A.; Cao, R.; Roy, J.; Tritsaris, K.; Wahlestedt, C.; Dissing, S.; Thyberg, J.; Cao, Y. Small GTP-binding protein Rac is an essential mediator of vascular endothelial growth factor-induced endothelial fenestrations and vascular permeability. Circulation 2003, 107, 1532–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monaghan-Benson, E.; Burridge, K. The regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor-induced microvascular permeability requires Rac and reactive oxygen species. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 25602–25611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogita, H.; Liao, J.K. Endothelial function and oxidative stress. Endothelium 2004, 11, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamaoka-Tojo, M.; Ushio-Fukai, M.; Hilenski, L.; Dikalov, S.I.; Chen, Y.E.; Tojo, T.; Fukai, T.; Fujimoto, M.; Patrushev, N.A.; Wang, N.; et al. IQGAP1, a novel vascular endothelial growth factor receptor binding protein, is involved in reactive oxygen species—Dependent endothelial migration and proliferation. Circ. Res. 2004, 95, 276–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, W.; Palmby, T.R.; Gavard, J.; Amornphimoltham, P.; Zheng, Y.; Gutkind, J.S. An essential role for Rac1 in endothelial cell function and vascular development. FASEB J. 2008, 22, 1829–1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamalice, L.; Houle, F.; Jourdan, G.; Huot, J. Phosphorylation of tyrosine 1214 on VEGFR2 is required for VEGF-induced activation of Cdc42 upstream of SAPK2/p38. Oncogene 2004, 23, 434–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engelse, M.A.; Laurens, N.; Verloop, R.E.; Koolwijk, P.; van Hinsbergh, V.W. Differential gene expression analysis of tubule forming and non-tubule forming endothelial cells: CDC42GAP as a counter-regulator in tubule formation. Angiogenesis 2008, 11, 153–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, G.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, L.; Tong, W.; Cheng, Y.; Luo, Y.; Cai, S.; Zhang, L. The generation of the endothelial specific Cdc42-deficient mice and the effect of Cdc42 deletion on the angiogenesis and embryonic development. Chin. Med. J. 2011, 124, 4155–4159. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Barry, D.M.; Xu, K.; Meadows, S.M.; Zheng, Y.; Norden, P.R.; Davis, G.E.; Cleaver, O. Cdc42 is required for cytoskeletal support of endothelial cell adhesion during blood vessel formation in mice. Development 2015, 142, 3058–3070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, H.; Breslin, J.W.; Zhu, J.; Yuan, S.Y.; Wu, M.H. Rho and ROCK signaling in VEGF-induced microvascular endothelial hyperpermeability. Microcirculation 2006, 13, 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cerutti, C.; Ridley, A.J. Endothelial cell-cell adhesion and signaling. Exp. Cell Res. 2017, 358, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dejana, E. Endothelial cell-cell junctions: Happy together. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2004, 5, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dejana, E.; Orsenigo, F.; Molendini, C.; Baluk, P.; McDonald, D.M. Organization and signaling of endothelial cell-to-cell junctions in various regions of the blood and lymphatic vascular trees. Cell Tissue Res. 2009, 335, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campos, Y.; Qiu, X.; Gomero, E.; Wakefield, R.; Horner, L.; Brutkowski, W.; Han, Y.G.; Solecki, D.; Frase, S.; Bongiovanni, A.; et al. Alix-mediated assembly of the actomyosin-tight junction polarity complex preserves epithelial polarity and epithelial barrier. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 11876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Nieuw Amerongen, G.P.; Koolwijk, P.; Versteilen, A.; van Hinsbergh, V.W. Involvement of RhoA/Rho kinase signaling in VEGF-induced endothelial cell migration and angiogenesis in vitro. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2003, 23, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mammoto, A.; Huang, S.; Moore, K.; Oh, P.; Ingber, D.E. Role of RhoA, mDia, and ROCK in cell shape-dependent control of the Skp2-p27kip1 pathway and the G1/S transition. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 26323–26330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glotzer, M. Animal cell cytokinesis. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2001, 17, 351–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamaguchi, M.; Nakao, S.; Arima, M.; Wada, I.; Kaizu, Y.; Hao, F.; Yoshida, S.; Sonoda, K.H. Rho-Kinase/ROCK as a Potential Drug Target for Vitreoretinal Diseases. J. Ophthalmol. 2017, 2017, 8543592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolinger, M.T.; Antonetti, D.A. Moving Past Anti-VEGF: Novel Therapies for Treating Diabetic Retinopathy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inoue, M.; Hager, J.H.; Ferrara, N.; Gerber, H.P.; Hanahan, D. VEGF-A has a critical, nonredundant role in angiogenic switching and pancreatic β cell carcinogenesis. Cancer Cell 2002, 1, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirones, I.; Conti, C.J.; Martínez, J.; Garcia, M.; Larcher, F. Complexity of VEGF responses in skin carcinogenesis revealed through ex vivo assays based on a VEGF-A null mouse keratinocyte cell line. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2009, 129, 730–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Park, S.T.; Kim, B.R.; Park, S.H.; Lee, J.H.; Lee, E.J.; Lee, S.H.; Rho, S.B. Suppression of VEGF expression through interruption of the HIF-1α and Akt signaling cascade modulates the anti-angiogenic activity of DAPK in ovarian carcinoma cells. Oncol. Rep. 2014, 31, 1021–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Wang, J.; Gou, W.F.; Xiu, Y.L.; Zheng, H.C.; Zong, Z.H.; Takano, Y.; Zhao, Y. The involvement of RhoA and Wnt-5a in the tumorigenesis and progression of ovarian epithelial carcinoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 24187–24199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, Y.; Bi, F.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, S.; Pan, Y.; Liu, N.; Shi, Y.; Yao, X.; Zheng, Y.; Fan, D. Role of Rac1 and Cdc42 in hypoxia induced p53 and von Hippel-Lindau suppression and HIF1α activation. Int. J. Cancer 2006, 118, 2965–2972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, F.; Wey, J.S.; McCarty, M.F.; Belcheva, A.; Liu, W.; Bauer, T.W.; Somcio, R.J.; Wu, Y.; Hooper, A.; Hicklin, D.J.; et al. Expression and function of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-1 on human colorectal cancer cells. Oncogene 2005, 24, 2647–2653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bates, R.C.; Goldsmith, J.D.; Bachelder, R.E.; Brown, C.; Shibuya, M.; Oettgen, P.; Mercurio, A.M. Flt-1-dependent survival characterizes the epithelial-mesenchymal transition of colonic organoids. Curr. Biol. 2003, 13, 1721–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, J.L.; Yang, P.C.; Shih, J.Y.; Yang, C.Y.; Wei, L.H.; Hsieh, C.Y.; Chou, C.H.; Jeng, Y.M.; Wang, M.Y.; Chang, K.J.; et al. The VEGF-C/Flt-4 axis promotes invasion and metastasis of cancer cells. Cancer Cell 2006, 9, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aesoy, R.; Sanchez, B.C.; Norum, J.H.; Lewensohn, R.; Viktorsson, K.; Linderholm, B. An autocrine VEGF/VEGFR2 and p38 signaling loop confers resistance to 4-hydroxytamoxifen in MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Mol. Cancer Res. 2008, 6, 1630–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oommen, S.; Gupta, S.K.; Vlahakis, N.E. Vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGF-A) induces endothelial and cancer cell migration through direct binding to integrin α9β1: Identification of a specific α9β1 binding site. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 1083–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, M.; Hou, L.; Li, J.; Shao, S.; Huang, S.; Meng, D.; Liu, L.; Feng, L.; Xia, P.; Qin, T.; et al. VEGF/NRP-1axis promotes progression of breast cancer via enhancement of epithelial-mesenchymal transition and activation of NF-κB and β-catenin. Cancer Lett. 2016, 373, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Xing, B.; Xuan, W.; Wang, H.; Huang, H.; Yang, J.; Tang, J. NRP-2 in tumor lymphangiogenesis and lymphatic metastasis. Cancer Lett. 2018, 418, 176–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geretti, E.; Shimizu, A.; Klagsbrun, M. Neuropilin structure governs VEGF and semaphorin binding and regulates angiogenesis. Angiogenesis 2008, 11, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, N.R.; Baker, D.; James, N.H.; Ratcliffe, K.; Jenkins, M.; Ashton, S.E.; Sproat, G.; Swann, R.; Gray, N.; Ryan, A.; et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor receptors VEGFR-2 and VEGFR-3 are localized primarily to the vasculature in human primary solid cancers. Clin. Cancer Res. 2010, 16, 3548–3561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, H.; Li, C.; Zhao, Y.; Wu, L.; Du, X.; Han, Z. VEGF-A/Neuropilin 1 Pathway Confers Cancer Stemness via Activating Wnt/β-Catenin Axis in Breast Cancer Cells. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2017, 44, 1251–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atzori, M.G.; Tentori, L.; Ruffini, F.; Ceci, C.; Lisi, L.; Bonanno, E.; Scimeca, M.; Eskilsson, E.; Daubon, T.; Miletic, H.; et al. The anti-vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-1 monoclonal antibody D16F7 inhibits invasiveness of human glioblastoma and glioblastoma stem cells. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017, 36, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshida, A.; Shimizu, A.; Asano, H.; Kadonosono, T.; Kondoh, S.K.; Geretti, E.; Mammoto, A.; Klagsbrun, M.; Seo, M.K. VEGF-A/NRP1 stimulates GIPC1 and Syx complex formation to promote RhoA activation and proliferation in skin cancer cells. Biol. Open 2015, 4, 1063–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Miao, W.; Tang, X.; Zhang, H.; Wang, S.; Luo, F.; Yan, J. Inhibitory effect of neuropilin-1 monoclonal antibody (NRP-1 MAb) on glioma tumor in mice. J. Biomed. Nanotechnol. 2013, 9, 551–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glinka, Y.; Mohammed, N.; Subramaniam, V.; Jothy, S.; Prud’homme, G.J. Neuropilin-1 is expressed by breast cancer stem-like cells and is linked to NF-κB activation and tumor sphere formation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2012, 425, 775–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, Q.; Chanthery, Y.; Liang, W.C.; Stawicki, S.; Mak, J.; Rathore, N.; Tong, R.K.; Kowalski, J.; Yee, S.F.; Pacheco, G.; et al. Blocking neuropilin-1 function has an additive effect with anti-VEGF to inhibit tumor growth. Cancer Cell 2007, 11, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, Q.D.; Rodrigues, S.; Rodrigue, C.M.; Rivat, C.; Grijelmo, C.; Bruyneel, E.; Emami, S.; Attoub, S.; Gespach, C. Inhibition of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-165 and semaphorin 3A-mediated cellular invasion and tumor growth by the VEGF signaling inhibitor ZD4190 in human colon cancer cells and xenografts. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2006, 5, 2070–2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Shimizu, A.; Mammoto, A.; Italiano, J.E.; Pravda, E.; Dudley, A.C.; Ingber, D.E.; Klagsbrun, M. ABL2/ARG tyrosine kinase mediates SEMA3F-induced RhoA inactivation and cytoskeleton collapse in human glioma cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 27230–27238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bachelder, R.E.; Crago, A.; Chung, J.; Wendt, M.A.; Shaw, L.M.; Robinson, G.; Mercurio, A.M. Vascular endothelial growth factor is an autocrine survival factor for neuropilin-expressing breast carcinoma cells. Cancer Res. 2001, 61, 5736–5740. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cao, Y.; E, G.; Wang, E.; Pal, K.; Dutta, S.K.; Bar-Sagi, D.; Mukhopadhyay, D. VEGF exerts an angiogenesis-independent function in cancer cells to promote their malignant progression. Cancer Res. 2012, 72, 3912–3918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wey, J.S.; Gray, M.J.; Fan, F.; Belcheva, A.; McCarty, M.F.; Stoeltzing, O.; Somcio, R.; Liu, W.; Evans, D.B.; Klagsbrun, M.; et al. Overexpression of neuropilin-1 promotes constitutive MAPK signalling and chemoresistance in pancreatic cancer cells. Br. J. Cancer 2005, 93, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snuderl, M.; Batista, A.; Kirkpatrick, N.D.; Ruiz de Almodovar, C.; Riedemann, L.; Walsh, E.C.; Anolik, R.; Huang, Y.; Martin, J.D.; Kamoun, W.; et al. Targeting placental growth factor/neuropilin 1 pathway inhibits growth and spread of medulloblastoma. Cell 2013, 152, 1065–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Zeng, H.; Wang, P.; Soker, S.; Mukhopadhyay, D. Neuropilin-1-mediated vascular permeability factor/vascular endothelial growth factor-dependent endothelial cell migration. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 48848–48860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chittenden, T.W.; Pak, J.; Rubio, R.; Cheng, H.; Holton, K.; Prendergast, N.; Glinskii, V.; Cai, Y.; Culhane, A.; Bentink, S.; et al. Therapeutic implications of GIPC1 silencing in cancer. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e15581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, D.; Haruta, A.; Wei, Q. GIPC1 interacts with MyoGEF and promotes MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cell invasion. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 28643–28650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dachsel, J.C.; Ngok, S.P.; Lewis-Tuffin, L.J.; Kourtidis, A.; Geyer, R.; Johnston, L.; Feathers, R.; Anastasiadis, P.Z. The Rho guanine nucleotide exchange factor Syx regulates the balance of Dia and ROCK activities to promote polarized-cancer-cell migration. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2013, 33, 4909–4918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamouille, S.; Xu, J.; Derynck, R. Molecular mechanisms of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2014, 15, 178–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández-García, R.; Iruela-Arispe, M.L.; Reyes-Cruz, G.; Vázquez-Prado, J. Endothelial RhoGEFs: A systematic analysis of their expression profiles in VEGF-stimulated and tumor endothelial cells. Vasc. Pharmacol. 2015, 74, 60–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, K.; Thodeti, C.K.; Dudley, A.C.; Mammoto, A.; Klagsbrun, M.; Ingber, D.E. Tumor-derived endothelial cells exhibit aberrant Rho-mediated mechanosensing and abnormal angiogenesis in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 11305–11310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kakiuchi, M.; Nishizawa, T.; Ueda, H.; Gotoh, K.; Tanaka, A.; Hayashi, A.; Yamamoto, S.; Tatsuno, K.; Katoh, H.; Watanabe, Y.; et al. Recurrent gain-of-function mutations of RHOA in diffuse-type gastric carcinoma. Nat. Genet. 2014, 46, 583–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, C.H.; Kim, Y.K.; Lee, S.; Kim, A.; Park, H.J.; Choi, Y.; Won, Y.J.; Park, D.Y.; Lauwers, G.Y. Gastric poorly cohesive carcinoma: A correlative study of mutational signatures and prognostic significance based on histopathological subtypes. Histopathology 2018, 72, 556–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, Y.; Liu, Y.M.; Li, L.C.; Wang, L.L.; Wu, X.L. MicroRNA-338 inhibits growth, invasion and metastasis of gastric cancer by targeting NRP1 expression. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e94422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minato, N. Rap G protein signal in normal and disordered lymphohematopoiesis. Exp. Cell Res. 2013, 319, 2323–2328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frische, E.W.; Zwartkruis, F.J. Rap1, a mercenary among the Ras-like GTPases. Dev. Biol. 2010, 340, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pizon, V.; Chardin, P.; Lerosey, I.; Olofsson, B.; Tavitian, A. Human cDNAs rap1 and rap2 homologous to the Drosophila gene Dras3 encode proteins closely related to ras in the ‘effector’ region. Oncogene 1988, 3, 201–204. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Altschuler, D.L.; Ribeiro-Neto, F. Mitogenic and oncogenic properties of the small G protein Rap1b. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 7475–7479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pannekoek, W.J.; Kooistra, M.R.; Zwartkruis, F.J.; Bos, J.L. Cell-cell junction formation: The role of Rap1 and Rap1 guanine nucleotide exchange factors. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2009, 1788, 790–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, C.W.; Ye, W. Regulation of vascular endothelial junction stability and remodeling through Rap1-Rasip1 signaling. Cell Adhes. Migr. 2014, 8, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, M.; Dekker, F.J.; Maarsingh, H. Exchange protein directly activated by cAMP (epac): A multidomain cAMP mediator in the regulation of diverse biological functions. Pharmacol. Rev. 2013, 65, 670–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carmona, G.; Göttig, S.; Orlandi, A.; Scheele, J.; Bäuerle, T.; Jugold, M.; Kiessling, F.; Henschler, R.; Zeiher, A.M.; Dimmeler, S.; et al. Role of the small GTPase Rap1 for integrin activity regulation in endothelial cells and angiogenesis. Blood 2009, 113, 488–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chrzanowska-Wodnicka, M.; Smyth, S.S.; Schoenwaelder, S.M.; Fischer, T.H.; White, G.C. Rap1b is required for normal platelet function and hemostasis in mice. J. Clin. Investig. 2005, 115, 680–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chrzanowska-Wodnicka, M.; Kraus, A.E.; Gale, D.; White, G.C.; Vansluys, J. Defective angiogenesis, endothelial migration, proliferation, and MAPK signaling in Rap1b-deficient mice. Blood 2008, 111, 2647–2656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Yan, J.; De, P.; Chang, H.C.; Yamauchi, A.; Christopherson, K.W.; Paranavitana, N.C.; Peng, X.; Kim, C.; Munugalavadla, V.; et al. Rap1a null mice have altered myeloid cell functions suggesting distinct roles for the closely related Rap1a and 1b proteins. J. Immunol. 2007, 179, 8322–8331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, J.; Li, F.; Ingram, D.A.; Quilliam, L.A. Rap1a is a key regulator of fibroblast growth factor 2-induced angiogenesis and together with Rap1b controls human endothelial cell functions. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2008, 28, 5803–5810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tawa, H.; Rikitake, Y.; Takahashi, M.; Amano, H.; Miyata, M.; Satomi-Kobayashi, S.; Kinugasa, M.; Nagamatsu, Y.; Majima, T.; Ogita, H.; et al. Role of afadin in vascular endothelial growth factor- and sphingosine 1-phosphate-induced angiogenesis. Circ. Res. 2010, 106, 1731–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lakshmikanthan, S.; Sobczak, M.; Chun, C.; Henschel, A.; Dargatz, J.; Ramchandran, R.; Chrzanowska-Wodnicka, M. Rap1 promotes VEGFR2 activation and angiogenesis by a mechanism involving integrin αvβ3. Blood 2011, 118, 2015–2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Somanath, P.R.; Malinin, N.L.; Byzova, T.V. Cooperation between integrin αvβ3 and VEGFR2 in angiogenesis. Angiogenesis 2009, 12, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lakshmikanthan, S.; Sobczak, M.; Li Calzi, S.; Shaw, L.; Grant, M.B.; Chrzanowska-Wodnicka, M. Rap1B promotes VEGF-induced endothelial permeability and is required for dynamic regulation of the endothelial barrier. J. Cell Sci. 2018, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majima, T.; Takeuchi, K.; Sano, K.; Hirashima, M.; Zankov, D.P.; Tanaka-Okamoto, M.; Ishizaki, H.; Miyoshi, J.; Ogita, H. An Adaptor Molecule Afadin Regulates Lymphangiogenesis by Modulating RhoA Activity in the Developing Mouse Embryo. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e68134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zankov, D.P.; Sato, A.; Shimizu, A.; Ogita, H. Differential Effects of Myocardial Afadin on Pressure Overload-Induced Compensated Cardiac Hypertrophy. Circ. J. 2017, 81, 1862–1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zankov, D.P.; Shimizu, A.; Tanaka-Okamoto, M.; Miyoshi, J.; Ogita, H. Protective effects of intercalated disk protein afadin on chronic pressure overload-induced myocardial damage. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 39335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ackah, E.; Yu, J.; Zoellner, S.; Iwakiri, Y.; Skurk, C.; Shibata, R.; Ouchi, N.; Easton, R.M.; Galasso, G.; Birnbaum, M.J.; et al. Akt1/protein kinase Bα is critical for ischemic and VEGF-mediated angiogenesis. J. Clin. Investig. 2005, 115, 2119–2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rikitake, Y.; Hirata, K.; Kawashima, S.; Ozaki, M.; Takahashi, T.; Ogawa, W.; Inoue, N.; Yokoyama, M. Involvement of endothelial nitric oxide in sphingosine-1-phosphate-induced angiogenesis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2002, 22, 108–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graupera, M.; Guillermet-Guibert, J.; Foukas, L.C.; Phng, L.K.; Cain, R.J.; Salpekar, A.; Pearce, W.; Meek, S.; Millan, J.; Cutillas, P.R.; et al. Angiogenesis selectively requires the p110α isoform of PI3K to control endothelial cell migration. Nature 2008, 453, 662–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heller, R.; Chang, Q.; Ehrlich, G.; Hsieh, S.N.; Schoenwaelder, S.M.; Kuhlencordt, P.J.; Preissner, K.T.; Hirsch, E.; Wetzker, R. Overlapping and distinct roles for PI3Kβ and γ isoforms in S1P-induced migration of human and mouse endothelial cells. Cardiovasc. Res. 2008, 80, 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lafuente, E.M.; van Puijenbroek, A.A.; Krause, M.; Carman, C.V.; Freeman, G.J.; Berezovskaya, A.; Constantine, E.; Springer, T.A.; Gertler, F.B.; Boussiotis, V.A. RIAM, an Ena/VASP and Profilin ligand, interacts with Rap1-GTP and mediates Rap1-induced adhesion. Dev. Cell 2004, 7, 585–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujita, H.; Fukuhara, S.; Sakurai, A.; Yamagishi, A.; Kamioka, Y.; Nakaoka, Y.; Masuda, M.; Mochizuki, N. Local activation of Rap1 contributes to directional vascular endothelial cell migration accompanied by extension of microtubules on which RAPL, a Rap1-associating molecule, localizes. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 5022–5031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avraamides, C.J.; Garmy-Susini, B.; Varner, J.A. Integrins in angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2008, 8, 604–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eliceiri, B.P.; Cheresh, D.A. The role of αv integrins during angiogenesis: Insights into potential mechanisms of action and clinical development. J. Clin. Investig. 1999, 103, 1227–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Legate, K.R.; Wickström, S.A.; Fässler, R. Genetic and cell biological analysis of integrin outside-in signaling. Genes Dev. 2009, 23, 397–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hynes, R.O. Integrins: Bidirectional, allosteric signaling machines. Cell 2002, 110, 673–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caron, E. Cellular functions of the Rap1 GTP-binding protein: A pattern emerges. J. Cell Sci. 2003, 116, 435–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katagiri, K.; Maeda, A.; Shimonaka, M.; Kinashi, T. RAPL, a Rap1-binding molecule that mediates Rap1-induced adhesion through spatial regulation of LFA-1. Nat. Immunol. 2003, 4, 741–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lagarrigue, F.; Kim, C.; Ginsberg, M.H. The Rap1-RIAM-talin axis of integrin activation and blood cell function. Blood 2016, 128, 479–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glading, A.; Han, J.; Stockton, R.A.; Ginsberg, M.H. KRIT-1/CCM1 is a Rap1 effector that regulates endothelial cell cell junctions. J. Cell Biol. 2007, 179, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abassi, Y.A.; Rehn, M.; Ekman, N.; Alitalo, K.; Vuori, K. p130Cas Couples the tyrosine kinase Bmx/Etk with regulation of the actin cytoskeleton and cell migration. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 35636–35643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoletov, K.V.; Terman, B.I. Bmx is a downstream Rap1 effector in VEGF-induced endothelial cell activation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004, 320, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamagnone, L.; Lahtinen, I.; Mustonen, T.; Virtaneva, K.; Francis, F.; Muscatelli, F.; Alitalo, R.; Smith, C.I.; Larsson, C.; Alitalo, K. BMX, a novel nonreceptor tyrosine kinase gene of the BTK/ITK/TEC/TXK family located in chromosome Xp22.2. Oncogene 1994, 9, 3683–3688. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Holz, F.G.; Schmitz-Valckenberg, S.; Fleckenstein, M. Recent developments in the treatment of age-related macular degeneration. J. Clin. Investig. 2014, 124, 1430–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, N.; Wong, I.Y.; Wong, T.Y. Ocular anti-VEGF therapy for diabetic retinopathy: Overview of clinical efficacy and evolving applications. Diabetes Care 2014, 37, 900–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos, C.J.; Lin, C.; Liu, X.; Antonetti, D.A. The EPAC-Rap1 pathway prevents and reverses cytokine-induced retinal vascular permeability. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 717–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Geisen, P.; Wittchen, E.S.; King, B.; Burridge, K.; D’Amore, P.A.; Hartnett, M.E. The role of RPE cell-associated VEGF189 in choroidal endothelial cell transmigration across the RPE. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2011, 52, 570–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Fotheringham, L.; Wittchen, E.S.; Hartnett, M.E. Rap1 GTPase Inhibits Tumor Necrosis Factor-α-Induced Choroidal Endothelial Migration via NADPH Oxidase- and NF-κB-Dependent Activation of Rac1. Am. J. Pathol. 2015, 185, 3316–3325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dewerchin, M.; Carmeliet, P. PlGF: A multitasking cytokine with disease-restricted activity. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2012, 2, a011056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menon, J.; Doebele, R.C.; Gomes, S.; Bevilacqua, E.; Reindl, K.M.; Rosner, M.R. A novel interplay between Rap1 and PKA regulates induction of angiogenesis in prostate cancer. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e49893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheta, E.A.; Harding, M.A.; Conaway, M.R.; Theodorescu, D. Focal adhesion kinase, Rap1, and transcriptional induction of vascular endothelial growth factor. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2000, 92, 1065–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uramoto, H.; Akyürek, L.M.; Hanagiri, T. A positive relationship between filamin and VEGF in patients with lung cancer. Anticancer Res. 2010, 30, 3939–3944. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vitali, E.; Boemi, I.; Rosso, L.; Cambiaghi, V.; Novellis, P.; Mantovani, G.; Spada, A.; Alloisio, M.; Veronesi, G.; Ferrero, S.; et al. FLNA is implicated in pulmonary neuroendocrine tumors aggressiveness and progression. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 77330–77340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dias, S.; Hattori, K.; Zhu, Z.; Heissig, B.; Choy, M.; Lane, W.; Wu, Y.; Chadburn, A.; Hyjek, E.; Gill, M.; et al. Autocrine stimulation of VEGFR-2 activates human leukemic cell growth and migration. J. Clin. Investig. 2000, 106, 511–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sitohy, B.; Nagy, J.A.; Dvorak, H.F. Anti-VEGF/VEGFR therapy for cancer: Reassessing the target. Cancer Res. 2012, 72, 1909–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, M.; Yan, B.P.; Liao, J.K.; Lam, Y.Y.; Yip, G.W.; Yu, C.M. Rho-kinase inhibition: A novel therapeutic target for the treatment of cardiovascular diseases. Drug Discov. Today 2010, 15, 622–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mor, A.; Haklai, R.; Ben-Moshe, O.; Mekori, Y.A.; Kloog, Y. Inhibition of contact sensitivity by farnesylthiosalicylic acid-amide, a potential Rap1 inhibitor. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2011, 131, 2040–2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ooshiro, D.; Yamaguchi, S.; Kakazu, M.; Arasaki, O. Effectiveness of continuous low-dose fasudil on refractory coronary vasospasm subsequent to cardiopulmonary arrest. Clin. Case Rep. 2017, 5, 1207–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shimizu, A.; Zankov, D.P.; Kurokawa-Seo, M.; Ogita, H. Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor-A Exerts Diverse Cellular Effects via Small G Proteins, Rho and Rap. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1203. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms19041203

Shimizu A, Zankov DP, Kurokawa-Seo M, Ogita H. Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor-A Exerts Diverse Cellular Effects via Small G Proteins, Rho and Rap. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2018; 19(4):1203. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms19041203

Chicago/Turabian StyleShimizu, Akio, Dimitar P. Zankov, Misuzu Kurokawa-Seo, and Hisakazu Ogita. 2018. "Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor-A Exerts Diverse Cellular Effects via Small G Proteins, Rho and Rap" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 19, no. 4: 1203. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms19041203

APA StyleShimizu, A., Zankov, D. P., Kurokawa-Seo, M., & Ogita, H. (2018). Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor-A Exerts Diverse Cellular Effects via Small G Proteins, Rho and Rap. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 19(4), 1203. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms19041203