A Brief Review of Computer-Assisted Approaches to Rational Design of Peptide Vaccines

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Interest in Peptide Vaccines

3. Computational Approaches to Peptide Vaccines

3.1. Web-Server-Based Peptide Identification

3.2. Software-Based Peptide Identification

3.3. Sequence-Descriptors-Based Peptide Identification

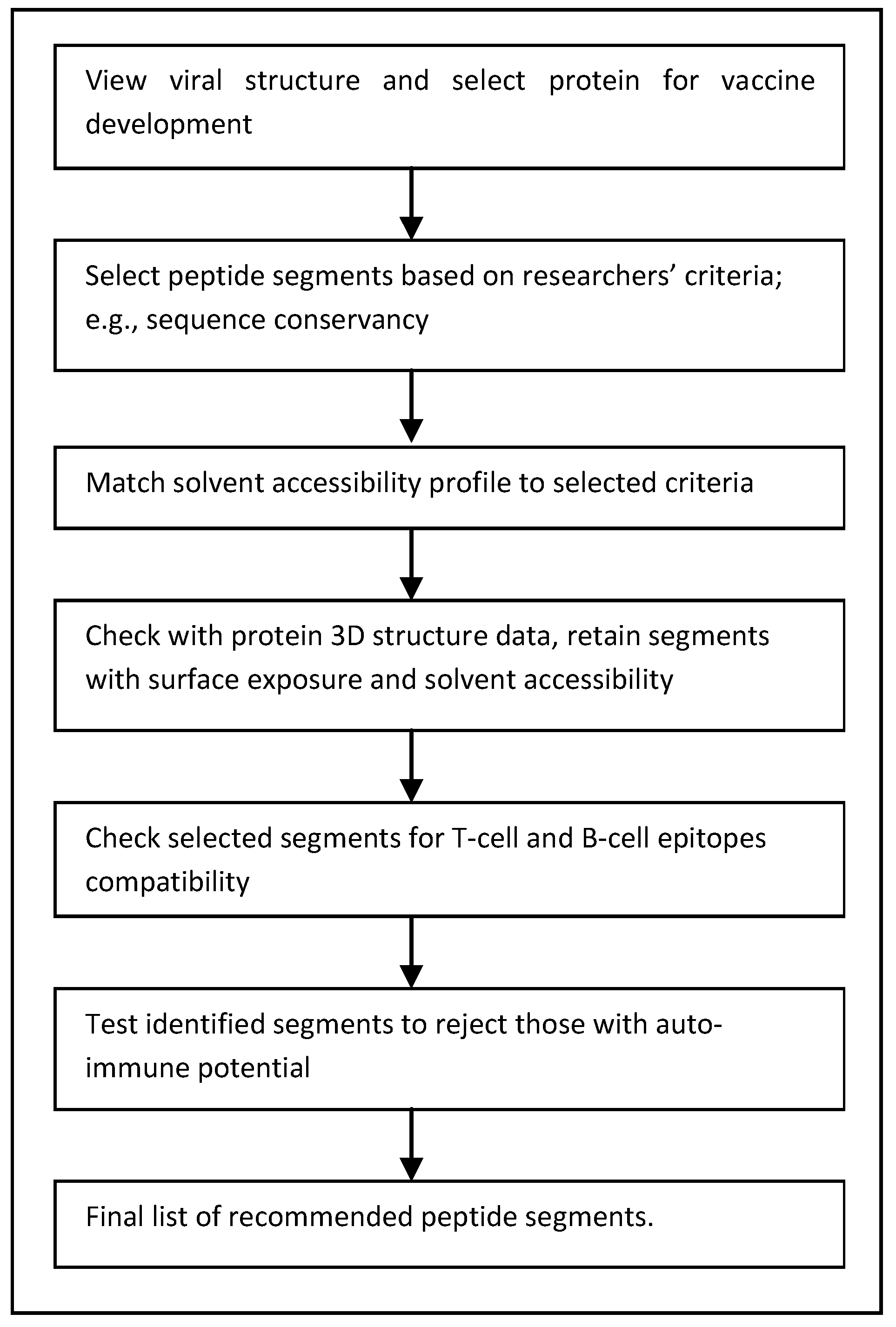

4. Improving the Search for Peptide Vaccines

4.1. Computational Efficiency

4.2. Bioinformatics Data

4.3. Transition to Wet Lab

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DOAJ | Directory of open access journals |

| MHC | Major Histocompatibility Index |

| SARS | Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome |

| MERS | Middle East Respiratory Syndrome |

| NIAID | National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases |

| NIH | National Institute of Health |

| MAP | Multiple Antigen Peptide |

| AIDS | Auto Immunity Deficiency Syndrome |

| HLA | Human Leukocyte Antigen |

| IEDB | Immune Epitope Database |

| ABCpred | Artificial neural network based B-cell epitope prediction |

| HCoV | Human Coronavirus |

| CTL | Cytotoxic T Lymphocytes |

| GB | Gigabytes |

| RAM | Random Access Memory |

| QSAR | Quantitative Structure Activity Relationship |

References

- Stanaway, J.D.; Shepard, D.S.; Undurraga, E.A.; Halasa, Y.A.; Coffeng, L.E.; Brady, O.J.; Hay, S.I.; Bedi, N.; Bensenor, I.M.; Castañeda-Orjuela, C.A.; et al. The global burden of dengue: An analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Global networks for surveillance of rotavirus gastroenteritis, 2001–2008. Wkly. Epidemiol. Rec. 2008, 83, 421–428. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Influenza (Seasonal). Fact Sheet No. 211. March 2014. Available online: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs211/en/ (accessed on 16 March 2016).

- Gorbalenya, A.E.; Snijder, E.J.; Spaan, W.J. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus phylogeny: Toward consensus. J. Virol. 2004, 78, 7863–7866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV). June 2015. Available online: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/mers-cov/en/ (accessed on 18 March 2016).

- World Health Organization. Ebola Virus Disease Outbreak. March 2016. Available online: http://www.who.int/csr/disease/ebola/en/ (accessed on 18 March 2016).

- PR Tufts CSDD 2014 Cost Study. Cost to Develop and Win Marketing Approval for a New Drug Is $2.6 Billion. Available online: http://csdd.tufts.edu/news/complete_story/pr_tufts_csdd_2014_cost_study (accessed on 9 January 2015).

- Chit, A.; Parker, J.; Halperin, S.A.; Papadimitropoulos, M.; Krahn, M.; Grootendorst, P. Toward more specific and transparent research and development costs: The case of seasonal influenza vaccines. Vaccine 2014, 32, 3336–3340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, S.-S.; Webby, R.J. Traditional and new influenza vaccines. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2013, 26, 476–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimizu, H.; Thorley, B.; Paladin, F.J.; Brussen, K.A.; Stambos, V.; Yuen, L.; Utama, A.; Tano, Y.; Arita, M.; Yoshida, H.; et al. Circulation of type 1 vaccine-derived poliovirus in the Philippines in 2001. J. Virol. 2004, 78, 13512–13521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chroboczek, J.; Szurgot, I.; Szolajska, E. Virus-like particles as vaccine. Acta Biochim. Polonica 2014, 61, 531–539. [Google Scholar]

- Poland, G.A.; Whitaker, J.A.; Poland, C.M.; Ovsyannikova, I.G.; Kennedy, R.B. Vaccinology in the third millennium: Scientific and social challenges. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2016, 17, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poland, G.A.; Kennedy, R.B.; Ovsyannikova, I.G. Vaccinomics and personalized vaccinology: Is science leading us toward a new path of directed vaccine development and discovery? PLoS Pathog. 2011, 7, e1002344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Purcell, A.W.; McCluskey, J.; Rossjohn, J. More than one reason to rethink the use of peptides in vaccine design. Nat. Rev. 2007, 6, 404–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langeveld, J.P.M.; Casal, J.I.; Osterhaus, A.D.M.E.; Cortes, E.; de Swart, R.; Vela, C.; Dalsgaard, K.; Puijk, W.C.; Schaaper, W.M.M.; Meloen, R.H. First peptide vaccine providing protection against viral infection in the target animal: Studies of canine parvovirus in dogs. J. Virol. 1994, 68, 4506–4513. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.; Charoenvit, Y.; Corradin, G.; Porrozzi, R.; Hunter, R.L.; Glenn, G.; Alving, C.R.; Church, P.; Hoffman, S.L. Induction of protective polyclonal antibodies by immunization with a Plasmodium yoelii circumsporozoite protein multiple antigen peptide vaccine. J. Immunol. 1995, 154, 2764–2793. [Google Scholar]

- Monso, M.; Tarradas, J.; de la Torre, B.G.; Sobrino, F.; Ganges, L.; Andreu, D. Peptide vaccine candidates against classical swine fever virus: T cell and neutralizing antibody responses of dendrimers displaying E2 and NS2–3 epitopes. J. Pept. Sci. 2011, 17, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ClinicalTrials gov. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?term=peptide+vaccines&pg=2 (accessed on 13 March 2016).

- Moisa, A.A.; Kolesanova, E.F. Synthetic peptide vaccines. In Insight and Control of Infectious Disease in Global Scenario; Roy, P., Ed.; ISBN 978-953-51-0319-6. InTech: Rijeka, Croatia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- NIAID. Available online: https://www.niaid.nih.gov/topics/zika/Pages/default.aspx (accessed on 16 March 2016).

- Brossart, P.; Wirths, S.; Stuhler, G.; Reichardt, V.L.; Kanz, L.; Brugger, W. Induction of cytotoxic T-lymphocyte responses in vivo after vaccinations with peptide-pulsed dendritic cells. Blood 2000, 96, 3102–3108. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ludewig, B.; Barchiesi, F.; Pericin, M.; Zinkernagel, R.M.; Hengartner, H.; Schwendener, R.A. In vivo antigen loading and activation of dendritic cells via a liposomal peptide vaccine mediates protective antiviral and anti-tumour immunity. Vaccine 2001, 19, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, S.-J.; Deng, D.-R.; Zeng, D.; Ma, D. HPV16 E5 peptide vaccine in treatment of cervical cancer in vitro and in vivo. J. Huazhong Univ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 33, 735–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rojas-Caraballo, J.; López-Abán, J.; Pérez del Villar, L.; Vizcaíno, C.; Vicente, B.; Fernández-Soto, P.; del Olmo, E.; Patarroyo, M.A.; Muro, A. In vitro and in vivo studies for assessing the immune response and protection-inducing ability conferred by fasciola hepatica-derived synthetic peptides containing B- and T-cell epitopes. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e105323. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, H.; Fukuhara, M.; Yamaura, T.; Mutoh, S.; Okabe, N.; Yaginuma, H.; Hasegawa, T.; Yonechi, A.; Osugi, J.; Hoshino, M.; et al. Multiple therapeutic peptide vaccines consisting of combined novel cancer testis antigens and anti-angiogenic peptides for patients with non-small cell lung cancer. J. Trans. Med. 2013, 11, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IEDB Analysis Resource. Available online: http://tools.immuneepitope.org/bcell/ (accessed on 10 March 2016).

- Kolaskar, A.S.; Tongaonkar, P.C. A semi-empirical method for prediction of antigenic determinants on protein antigens. FEBS Lett. 1990, 276, 172–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, R.; Sakib, M.S.; Zaman, A. A computational assay to design an epitope-based peptide vaccine against chikungunya virus. Future Virol. 2012, 7, 1029–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poland, G.A.; Ovsyannikova, I.G.; Jacobson, R.M. Application of pharmacogenomics to vaccines. Pharmacogenomics 2009, 10, 837–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rappuoli, R. Reverse vaccinology, a genome-based approach to vaccine development. Vaccine 2001, 19, 2688–2691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barocchi, M.A.; Censini, S.; Rappuoli, R. Vaccines in the era of genomics: The pneumococcal challenge. Vaccine 2007, 25, 2963–2973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varghese, J.N. Development of neuraminidase inhibitors as anti-influenza virus drugs. Drug Dev. Res. 1999, 46, 176–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, L.W.; Malikayil, A. The impact of structure-guided drug design on clinical agents. Curr. Drug Discov. 2003, 11, 15–20. [Google Scholar]

- Assess the Safety and Immunogenicity of M-001 as A Standalone Influenza Vaccine and as A H5N1 Vaccine Primer in Adults. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02691130?term=influenza+AND+peptide+vaccines&rank=4 (accessed on 13 March 2016).

- Safety, Tolerability and Immunogenicity of Two Different Formulations of an Influenza A Vaccine (FP-01.1). Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01677676?term=influenza+AND+peptide+vaccines&rank=9 (accessed on 13 March 2016).

- HIV-1 Peptide Immunisation of Individuals in West Africa to Prevent Disease (HIV-BIS). Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01141205?term=sers+peptide+vaccine&rank=12 (accessed on 13 March 2016).

- Vaccine Therapy and Cyclophosphamide in Treating Patients with Stage II-III Breast or Stage II-IV Ovarian, Primary Peritoneal, or Fallopian Tube Cancer. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01606241?term=cancer+and+peptide+vaccines&rank=4 (accessed on 13 March 2016).

- Vaccine Therapy in Treating Patients with Metastatic Cancer. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00020267?term=cancer+and+peptide+vaccines&rank=16 (accessed on 13 March 2016).

- Singluff, C.L. The present and future of peptide vaccines for cancer: Single or multiple, long or short, alone or in combination? Cancer J. 2011, 17, 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huber, S.R.; van Beek, J.; de Jonge, J.; Luytjes, W.; van Baarle, D. T cell responses to viral infections—Opportunities for peptide vaccination. Front. Immunol. 2014, 5, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Joshi, M.D.; Singhania, S.; Ramsey, K.H.; Murthy, A.K. Peptide vaccine: Progress and challenges. Vaccines 2014, 2, 515–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sirskyj, D.; Diaz-Mitoma, F.; Golshani, A.; Kumar, A.; Azizi, A. Innovative bioinformatic approaches for developing peptide-based vaccines against hypervariable viruses. Immunol. Cell Biol. 2011, 89, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sobolev, B.N.; Olenina, L.V.; Kolesanova1, E.F.; Poroikov, V.V.; Archakov, A.I. Computer design of vaccines: Approaches, software tools and informational resources. Curr. Comp. Aided Drug Des. 2005, 1, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomar, N.; de, R.K. Immunoinformatics: An integrated study. Immunology 2010, 131, 153–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basak, S.C.; Nandy, A. Computer-assisted approaches as decision support systems in the overall strategy of combating emerging diseases: Some comments regarding drug design, vaccinomics, and genomic surveillance of the Zika virus. Curr. Comput.-Aided Drug Des. 2016, 12, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doytchinova, I.A.; Flower, D.R. VaxiJen: A server for prediction of protective antigens, tumour antigens and subunit vaccines. BMC Bioinform. 2007, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Immune Epitope Database and Analysis Resource. Available online: http://www.iedb.org/home_v2.php?Clear=Clear# (accessed on 15 March 2016).

- ABCpred. Available online: http://www.imtech.res.in/raghava/abcpred/ (accessed on 15 March 2016).

- Oyarzun, P.; Ellis, J.J.; Bodén, M.; Kobe, B. PREDIVAC: CD4+ T-cell epitope prediction for vaccine design that covers 95% of HLA class II DR protein diversity. BMC Bioinform. 2013, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oany, A.R.; Emran, A.-A.; Jyoti, T.P. Design of an epitope-based peptide vaccine against spike protein of human coronavirus: An in silico approach. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2014, 8, 1139–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NetCTL 1.2 Server. Available online: http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/NetCTL/ (accessed on 16 March 2016).

- Chakraborty, S.; Chakravorty, R.; Ahmed, M.; Rahman, A.; Waise, T.M.Z.; Hassan, F.; Rahman, M.; Shamsuzzaman, S. A computational approach for identification of epitopes in dengue virus envelope protein: A step towards designing a universal dengue vaccine targeting endemic regions. In Silico Biol. 2010, 10, 235–246. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gomase, V.S.; Kale, K.V.; Chikhale, N.J.; Changbhale, S.S. Prediction of MHC binding peptides and epitopes from alfalfa mosaic virus. Curr. Drug Discov. Technol. 2007, 4, 117–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomase, V.S.; Kale, K.V. Prediction of MHC binder for fragment based viral peptide vaccines from cabbage leaf curl virus. Gene Ther. Mol. Biol. 2008, 12, 83–86. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, A.; Nandy, A.; Nandy, P.; Gute, B.D.; Basak, S.C. Computational study of dispersion and extent of mutated and duplicated sequences of the H5N1 influenza neuraminidase over the period 1997–2008. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2009, 49, 2627–2638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nandy, A.; Basak, S.C. Prognosis of possible reassortments in recent H5N2 epidemic influenza in USA: Implications for computer-assisted surveillance as well as drug/vaccine design. Curr. Comput. Aided Drug. Des. 2015, 11, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, B.; Liu, Y.; Li, R.; Zhu, W. Coronavirus phylogeny based on triplets of nucleic acids bases. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2006, 421, 313–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.; Nandy, A.; Nandy, P. Computational analysis and determination of a highly conserved surface exposed segment in H5N1 avian flu and H1N1 swine flu neuraminidase. BMC Struct. Biol. 2010, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, A.; Chattopadhyay, S.; Chawla-Sarkar, M.; Nandy, P.; Nandy, A. In silico study of rotavirus VP7 surface accessible conserved regions for antiviral drug/vaccine design. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e40749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarkar, T.; Das, S.; De, A.; Nandy, P.; Chattopadhyay, S.; Chawla-Sarkar, M.; Nandy, A. H7N9 influenza outbreak in China 2013: In silico analyses of conserved segments of the hemagglutinin as a basis for the selection of peptide vaccine targets. Comput. Biol. Chem. 2015, 59, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawkins, D.M.; Basak, S.C.; Kraker, J.; Geiss, K.T.; Witzmann, F.A. Combining chemodescriptors and biodescriptors in quantitative structure-activity relationship modeling. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2006, 46, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basak, S.C.; Mills, D.; Gute, B.D.; Natarajan, R. Predicting pharmacological and toxicological activity of heterocyclic compounds using QSAR and molecular modeling. In QSAR and Molecular Modeling Studies of Heterocyclic Drugs, I; Gupta, S.P., Ed.; Springer-Verlag: Berlin, Germany; Heidelberg, Germany; New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 39–80. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Diaz, H.; Gonzalez-Diaz, Y.; Santana, L.; Ubeira, F.M.; Uriarte, E. Proteomics, networks and connectivity indices. Proteomics 2008, 8, 750–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez-Diaz, H.; Perez-Montoto, L.G.; Duardo-Sanchez, A.; Paniagua, E.; Vazquez-Prieto, S.; Vilas, R.; Dea-Ayuelac, M.A.; Bolas-Fernándezd, F.; Munteanue, C.R.; Doradoe, J.; et al. Generalized lattice graphs for 2D-visualization of biological information. J. Theor. Biol. 2009, 261, 136–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vilar, S.; González-Díaz, H. QSPR models for human Rhinovirus surface networks. In Topological Indices for Medicinal Chemistry, Biology, Parasitology, Neurological and Social Networks; González-Díaz, H., Munteanu, C.R., Eds.; Transworld Research Network: Kerala, India; 2010; pp. 145–161. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida, J.P.; Lin, A.Y.; Figueroa, E.R.; Foster, A.E.; Drezek, R.A. In vivo gold nanoparticle delivery of peptide vaccine induces anti-tumor immune response in prophylactic and therapeutic tumor models. Small 2015, 11, 1453–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Peptide Vaccine/Disease | Firm/Institution | Trial Stage | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| BOPRIVA (® Registered Trade Mark name) peptide vaccine induces antibodies against Gonadotropin-releasing factor and controls aggressive behavior in bulls | Pfizer | launched | [9] |

| NeuVax synthetic peptide vaccine for breast cancer prevention | Galena Biopharma, | Phase III | Identifier: NCT01479244 in [18] |

| Peptide vaccine for HIV (human immunodeficiency virus) | United Biomedical | Phase I/II completed | Identifier: NCT00002428 in [18] |

| Peptide vaccine for recurrent prostate cancer | University Hospital Tuebingen | Phase II | Identifier: NCT02452307 in [18] |

| Multileric linear epitope based peptide vaccine for influenza A and B | BiondVax Pharmaceuticals Ltd. | Phase II | Identifier: NCT02691130 in [18] |

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nandy, A.; Basak, S.C. A Brief Review of Computer-Assisted Approaches to Rational Design of Peptide Vaccines. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 666. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms17050666

Nandy A, Basak SC. A Brief Review of Computer-Assisted Approaches to Rational Design of Peptide Vaccines. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2016; 17(5):666. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms17050666

Chicago/Turabian StyleNandy, Ashesh, and Subhash C. Basak. 2016. "A Brief Review of Computer-Assisted Approaches to Rational Design of Peptide Vaccines" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 17, no. 5: 666. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms17050666

APA StyleNandy, A., & Basak, S. C. (2016). A Brief Review of Computer-Assisted Approaches to Rational Design of Peptide Vaccines. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 17(5), 666. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms17050666