Current Understanding of the Interplay between Phytohormones and Photosynthesis under Environmental Stress

Abstract

:1. Introduction

| Hormone | Plant | Stress | Effect on Photosynthetic Components | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABA | Arabidopsis | High light | Reduced expression of photosynthetic genes | [40] |

| Arabidopsis | Chemical (norflurazon) | Induction of genes encoding LHCB proteins | [41] | |

| Arabidopsis | Drought | Positive regulation of genes encoding LHCB proteins | [42] | |

| Barley | Heat | Decreased heat damage of chloroplast ultrastructure, improved PSII efficiency | [43] | |

| Barley | Low temperature | Higher photochemical quenching and NPQ | [44] | |

| Common bean, tobacco, beetroot, maize | Drought | Improved PSII efficiency | [45] | |

| Rice | Drought | Improved NPQ and PSII efficiency | [46] | |

| Rice, cabbage | High salinity | Enhanced PSII efficiency, NPQ and PSII photochemistry | [47] | |

| Lycium chinese | Drought | Slower decline in PSII efficiency, improved NPQ | [48] | |

| Auxin | Arabidopsis | Drought | Improved maximal electron transfer rate, photochemical quenching and maximal photochemical yield of PSII | [49] |

| Sunflower | Heavy metal | Increased ability of energy trapping by PSII reaction centres | [50] | |

| BRs | Rice | High salinity | Prevention of photosynthetic pigment loss | [51] |

| Mustard | Heavy metal | Higher chlorophyll accumulation and improved PN | [52] | |

| Winter rape | Heavy metal | Improved energy absorption, trapping, and electron transport by PSII reaction centers. Efficient oxygen-evolution | [53] | |

| BRs | Mungbean | Heavy metal | Higher PN and improved stomatal conductivity | [54] |

| Cucumber | Drought | Higher PSII efficiency, improved NPQ | [55] | |

| Tomato | Chemical stress, heavy metal | Improved PN, PSII efficiency, and NPQ | [56] | |

| Tomato | Heat | Improved recovery of PN, stomatal conductance, and maximum carboxylation rate of Rubisco, electron transport rate, relative quantum efficiency of PSII photochemistry, photochemical quenching, and increased NPQ | [57] | |

| Pepper | Drought | Improved utilization and dissipation of excitation energy in the PSII antennae. Alleviation of drought-induced photoinhibition | [58] | |

| CKs | Tobacco | Drought | Slower degradation of photosynthetic protein complexes, increased expression of genes associated with PSII, Cytb6f complex, PSI, NADH oxidoreductase, and ATP synthase complex | [59] |

| Arabidopsis | High light | Reduced PSII efficiency, low accumulation of D1 protein | [39] | |

| Maize | Drought | Increased electron donation capacity of PSII, higher plant photosynthetic performance index, energy absorption and trapped excitation energy | [60] | |

| ET | Mustard | Heavy metal | Efficient PSII, PN, stomatal conductance, and Rubisco activities | [61] |

| Mustard | Low nitrogen | Improved PN, Rubisco activity, and stomatal conductivity | [62] | |

| Mustard | High salinity | Higher photosynthetic-nitrogen and sulfur use efficiency and improved quantum yield efficiency of PSII | [63] | |

| Mustard | Heavy metal | Increased maximal quantum efficiency of PSII, PN,and Rubisco activity | [64] | |

| Tobacco | High salinity, oxidative stress | Increased PN | [65] | |

| GAs | Wheat | High salinity | Improved PN and stomatal conductance | [66] |

| Mustard | High salinity | Increased photosynthetic efficiency and stomatal conductance | [67] | |

| Linseed | High salinity | Improved PN, and stomatal conductance | [68] | |

| Sunflower | Heavy metal | Increased ability of energy trapping by PSII reaction centers | [50] | |

| JA | Rice | High salinity | Improved leaf water potential, Fv/Fm, and PN | [69] |

| Pisum sativum | High salinity | Increased non-variable fluorescence, Fv/Fm, and Rubisco activity | [70] | |

| Barley | High salinity | Improved Fv/Fm and PN | [71] | |

| Arabidopsis | Heavy metal | Improved photosynthesis activity | [72] | |

| Arabidopsis | Heavy metal | Improved PSII activity, Fv/Fm, and PN | [73] | |

| SA | Arabidopsis | Drought | Higher PN, maximum efficiency of PSII, and maximum quantum yield of PSII | [74] |

| Wheat | High salinity | Increased quantum yield of PSII | [75] | |

| SA | Wheat | Heat, high light | Improved PSII efficiency, slower degradation and accelerated recovery of damaged D1 protein | [76] |

| Wheat | Drought | Upregulated expression of luminal, oxygen-evolving enhancer, and PSII assembly factor proteins | [77] | |

| Rice | Drought | Higher PN, stomatal conductance, and transpiration rate | [78] | |

| Mustard | High salinity | Improved PN, stomatal conductance, and water use efficiency | [79] | |

| Mustard | High salinity | Improved PSII efficiency,PN, Rubisco activity, water-use efficiency, and stomatal conductance | [80] | |

| Cotton | High salinity | Increased PSII activity, PN and transpiration rate | [81] | |

| Maize | High salinity | Increased PN and Rubisco activity | [82] | |

| SA | Grapevine | Heat | Improved PN, chlorophyll a fluorescence, higher stomatal conductance | [83] |

| Grapevine | Heat | Improved PN, enhanced Rubisco and PSII activities | [84] | |

| Tomato | Drought | Higher PN, stomatal conductance | [85] | |

| Common sage | Drought | Maintenance of maximum efficiency of PSII and protection of photosynthetic apparatus | [86] | |

| Torreyagrandis | High salinity | Increased PN | [87] | |

| SLs | Arabidopsis | Drought | Higher expression of photosynthetic genes | [88] |

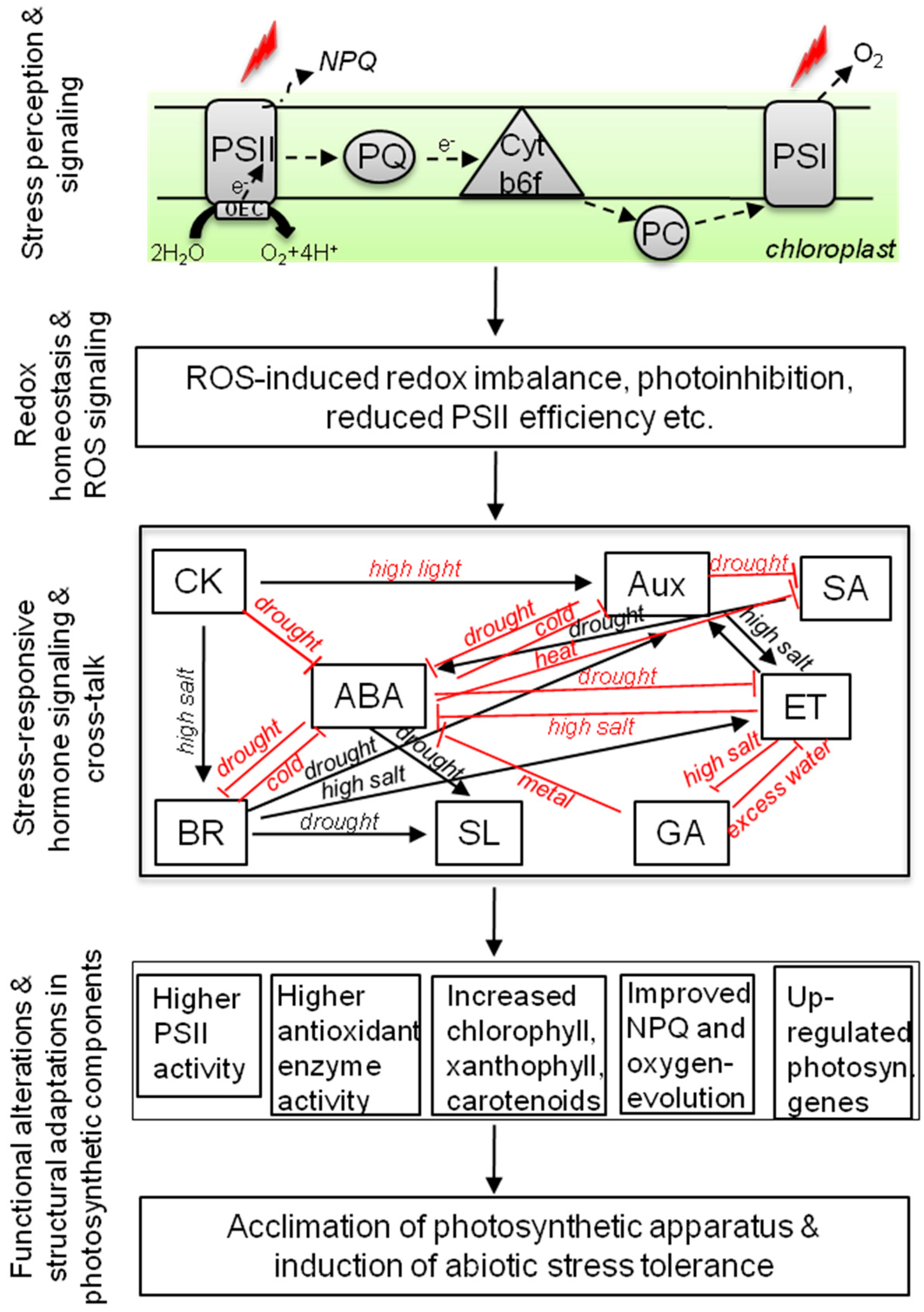

2. PSII Damage and Role of Hormones

2.1. Abscisic Acid

2.2. Auxins

2.3. Brassinosteroids

2.4. Cytokinins

2.5. Ethylene (ET)

2.6. Gibberellins

2.7. Jasmonates

2.8. Salicylic Acid (SA)

2.9. Strigolactones

3. Future Challenges and Perspectives

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ABA | abscisic acid |

| BR | brassinosteroid |

| CK | cytokinin |

| ET | ethylene |

| GA | gibberellic acid |

| IAA | indole acetic acid |

| IBA | indole butyric acid |

| LHCII | light harvesting complex II |

| NPQ | non-photochemical quenching |

| OEC | oxygen-evolving complex |

| OJIP | O and P denote origin and peak respectively and J-I denote intermediate phases of fluorescence induction |

| PN | net photosynthesis rate |

| PsbO | photosystem b O protein |

| PsbP | photosystem b P protein |

| PSI | photosystem I |

| PSII | photosystem II |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| SA | salicylic acid |

| VDE | violaxanthin de-epoxidase |

References

- Mickelbart, M.V.; Hasegawa, P.M.; Bailey-Serres, J. Genetic mechanisms of abiotic stress tolerance that translate to crop yield stability. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2015, 16, 237–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailey-Serres, J.; Lee, S.C.; Brinton, E. Waterproofing crops: Effective flooding survival strategies. Plant Physiol. 2012, 160, 1698–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maslenkova, L.T.; Zanev, Y.; Popova, L.P. Effect of abscisic-acid on the photosynthetic oxygen evolution in barley chloroplasts. Photosynth. Res. 1989, 21, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bartoli, C.G.; Casalongué, C.A.; Simontacchi, M.; Marquez-Garcia, B.; Foyer, C.H. Interactions between hormone and redox signalling pathways in the control of growth and cross tolerance to stress. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2013, 94, 73–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortleven, A.; Noben, J.P.; Valcke, R. Analysis of the photosynthetic apparatus in transgenic tobacco plants with altered endogenous cytokinin content: A proteomic study. Proteome Sci. 2011, 9, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, S.; Murata, N. How do environmental stresses accelerate photoinhibition? Trends Plant Sci. 2008, 13, 178–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, S.; Badger, M.R. Photoprotection in plants: A new light on photosystem II damage. Trends Plant Sci. 2011, 16, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nath, K.; Jajoo, A.; Poudyal, R.S.; Timilsina, R.; Park, Y.S.; Aro, E.M.; Nam, H.G.; Lee, C.H. Towards a critical understanding of the photosystem II repair mechanism and its regulation during stress conditions. FEBS Lett. 2013, 587, 3372–3381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gururani, M.A.; Upadhyaya, C.P.; Strasser, R.J.; Woong, Y.J.; Park, S.W. Physiological and biochemical responses of transgenic potato plants with altered expression of PSII manganese stabilizing protein. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2012, 58, 182–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rochaix, J.D. Regulation and dynamics of the light-harvesting system. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2014, 65, 287–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaspers, P.; Kangasjärvi, J. Reactive oxygen species in abiotic stress signaling. Physiol. Plant. 2010, 138, 405–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spetea, C.; Rintamäki, E.; Schoefs, B. Changing the light environment : Chloroplast signalling and response mechanisms. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond B: Biol. Sci. 2014, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grieco, M.; Tikkanen, M.; Paakkarinen, V.; Kangasjarvi, S.; Aro, E.M. Steady-state phosphorylation of light-harvesting complex II proteins preserves photosystem I under fluctuating white light. Plant Physiol. 2012, 160, 1896–1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gururani, M.A.; Upadhyaya, C.P.; Strasser, R.J.; Yu, J.W.; Park, S.W. Evaluation of abiotic stress tolerance in transgenic potato plants with reduced expression of PSII manganese stabilizing protein. Plant Sci. 2013, 198, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gururani, M.A.; Venkatesh, J.; Ganesan, M.; Strasser, R.J.; Han, Y.; Kim, J.I.; Lee, H.Y.; Song, P.S. In vivo assessment of cold tolerance through chlorophyll-a fluorescence in transgenic zoysiagrass expressing mutant phytochrome A. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0127200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mellis, A. Photosystem-II damage and repair cycle in chloroplasts: What modulates the rate of photodamage in vivo? Trends Plant Sci. 1999, 4, 130–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murata, N.; Takahashi, S.; Nishiyama, Y.; Allakhverdiev, S.I. Photoinhibition of photosystem II under environmental stress. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2007, 1767, 414–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishiyama, Y.; Murata, N. Revised scheme for the mechanism of photoinhibition and its application to enhance the abiotic stress tolerance of the photosynthetic machinery. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2014, 1, 8777–8796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishiyama, Y.; Allakhverdiev, S.I.; Murata, N. Protein synthesis is the primary target of reactive oxygen species in the photoinhibition of photosystem II. Physiol. Plant. 2011, 142, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gururani, M.A.; Venkatesh, J.; Tran, L.S.P. Regulation of photosynthesis during abiotic stress-induced photoinhibition. Mol. Plant 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kato, Y.; Miura, E.; Ido, K.; Ifuku, K.; Sakamoto, W. The variegated mutants lacking chloroplastic FtsHs are defective in D1 degradation and accumulate reactive oxygen species. Plant Physiol. 2009, 151, 1790–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tóth, S.Z. Analysis and Application of the fast Chl a Fluorescence (OJIP) Transient Complemented with Simultaneous 820 nm Transmission Measurements. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Geneva, Geneva, Switzerland, May 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Strasser, R.J.; Govindjee. The F0 and the O-J-I-P fluorescence rise in higher plants and algae. Regul. Chloroplast Biogenes. 1991, 226, 423–426. [Google Scholar]

- Tóth, S.Z.; Schansker, G.; Strasser, R.J. A non-invasive assay of the plastoquinone pool redox state based on the OJIP-transient. Photosynth. Res. 2007, 93, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stirbet, A.; Govindjee. On the relation between the Kautsky effect (chlorophyll a fluorescence induction) and Photosystem II: Basics and applications of the OJIP fluorescence transient. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B: Biol. 2011, 104, 236–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strasser, R.J.; Tsimilli-Michael, M.; Srivastava, A. Analysis of the chlorophyll a fluorescence transient. In Chlorophyll a Fluorescence; Springer Netherlands: Heidelberg, Germany, 2004; pp. 321–362. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, B.F.; Duan, W.; Liu, G.T.; Xu, H.G.; Wang, L.J.; Li, S.H. Response of bean (Vicia faba L.) plants to low sink demand by measuring the gas exchange rates and chlorophyll a fluorescence kinetics. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, 6–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goltsev, V.; Zaharieva, I.; Chernev, P.; Kouzmanova, M.; Kalaji, H.M.; Yordanov, I.; Krasteva, V.; Alexandrov, V.; Stefanov, D.; Allakhverdiev, S.I.; et al. Drought-induced modifications of photosynthetic electron transport in intact leaves: Analysis and use of neural networks as a tool for a rapid non-invasive estimation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2012, 1817, 1490–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zivcak, M.; Kalaji, H.M.; Shao, H.B.; Olsovska, K.; Brestic, M. Photosynthetic proton and electron transport in wheat leaves under prolonged moderate drought stress. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B: Biol. 2014, 137, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gururani, M.A.; Upadhyaya, C.P.; Baskar, V.; Venkatesh, J.; Nookaraju, A.; Park, S.W. Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria enhance abiotic stress tolerance in solanum tuberosum through inducing changes in the expression of ROS-scavenging enzymes and improved photosynthetic performance. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2013, 32, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gururani, M.A.; Ganesan, M.; Song, I.J.; Han, Y.; Kim, J.I.; Lee, H.Y.; Song, P.S. Transgenic turfgrasses txpressing hyperactive Ser599Ala phytochrome amutant exhibit abiotic stress tolerance. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tóth, S.Z.; Nagy, V.; Puthur, J.T.; Kovács, L.; Garab, G. The physiological role of ascorbate as photosystem II electron donor: protection against photoinactivation in heat-stressed leaves. Plant Physiol. 2011, 156, 382–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayzlish-Gati, E.; LekKala, S.P.; Resnick, N.; Wininger, S.; Bhattacharya, C.; Lemcoff, J.H.; Kapulnik, Y.; Koltai, H. Strigolactones are positive regulators of light-harvesting genes in tomato. J. Exp. Bot. 2010, 61, 3129–3136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krumova, S.; Zhiponova, M.; Dankov, K.; Velikova, V.; Balashev, K.; Andreeva, T.; Russinova, E.; Taneva, S. Brassinosteroids regulate the thylakoid membrane architecture and the photosystem II function. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B: Biol. 2013, 126, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobrikova, A.G.; Vladkova, R.S.; Rashkov, G.D.; Todinova, S.J.; Krumova, S.B.; Apostolova, E. L. Effects of exogenous 24-epibrassinolide on the photosynthetic membranes under non-stress conditions. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2014, 80, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tikkanen, M.; Aro, E.M. Integrative regulatory network of plant thylakoid energy transduction. Trends Plant Sci. 2014, 19, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peleg, Z.; Blumwald, E. Hormone balance and abiotic stress tolerance in crop plants. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2011, 14, 290–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tikkanen, M.; Gollan, P.J.; Mekala, N.R.; Isojärvi, J.; Aro, E.M. Light-harvesting mutants show differential gene expression upon shift to high light as a consequence of photosynthetic redox and reactive oxygen species metabolism. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond B: Biol. Sci. 2014, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortleven, A.; Nitschke, S.; Klaumunzer, M.; AbdElgawad, H.; Asard, H.; Grimm, B.; Riefler, M.; Schmulling, T. A novel protective function for cytokinin in the light stress response is mediated by the ARABIDOPSIS HISTIDINE KINASE2 and ARABIDOPSIS HISTIDINE KINASE3 receptors. Plant Physiol. 2014, 164, 1470–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staneloni, R.J.; Rodriguez-Batiller, M.J.; Casal, J.J. Abscisic acid, high-light, and oxidative stress down-regulate a photosynthetic gene via a promoter motif not involved in phytochrome-mediated transcriptional regulation. Mol. Plant 2008, 1, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voigt, C.; Oster, U.; Börnke, F.; Jahns, P.; Dietz, K.J.; Leister, D.; Kleine, T. In-depth analysis of the distinctive effects of norflurazon implies that tetrapyrrole biosynthesis, organellar gene expression and ABA cooperate in the GUN-type of plastid signalling. Physiol. Plant. 2010, 138, 503–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.H.; Liu, R.; Yan, L.; Liu, Z.Q.; Jiang, S.C.; Shen, Y.Y.; Wang, X.F.; Zhang, D.P. Light-harvesting chlorophyll a/b-binding proteins are required for stomatal response to abscisic acid in Arabidopsis. J. Exp. Bot. 2012, 63, 1095–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivanov, A.G.; Kitcheva, M.I.; Christov, A.M.; Popova, L.P. Effects of abscisic acid treatment on the thermostability of the photosynthetic apparatus in barley chloroplasts. Plant Physiol. 1992, 98, 1228–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivanov, A.G.; Krol, M.; Maxwell, D.; Huner, N.P. Abscisic acid induced protection against photoinhibition of PSII correlates with enhanced activity of the xanthophyll cycle. FEBS Lett. 1995, 371, 61–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haisel, D.; Pospíšilová, J.; Synková, H.; Schnablová, R.; Baťková, P. Effects of abscisic acid or benzyladenine on pigment contents, chlorophyll fluorescence, and chloroplast ultrastructure during water stress and after rehydration. Photosynthetica 2006, 44, 606–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; Wang, N.; Cui, F.; Li, X.; Xiao, J.; Xiong, L. Characterization of the β-carotene hydroxylase gene DSM2 conferring drought and oxidative stress resistance by increasing xanthophylls and abscisic acid synthesis in rice. Plant Physiol. 2010, 154, 1304–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, S.Q.; Chen, M.W.; Ji, B.H.; Jiao, D.M.; Liang, J.S. Roles of xanthophylls and exogenous ABA in protection against NaCl-induced photodamage in rice (Oryza sativa L.) and cabbage (Brassica campestris). J. Exp. Bot. 2011, 62, 4617–4625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, C.; Ji, J.; Zhang, X.; Li, X.; Jin, C.; Guan, W.; Wang, G. Positive feedback regulation of a Lycium chinense-derived VDE gene by drought-induced endogenous ABA, and over-expression of this VDE gene improve drought-induced photo-damage in Arabidopsis. J. Plant Physiol. 2015, 175, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tognetti, V.B.; van Aken, O.; Morreel, K.; Vandenbroucke, K.; van de Cotte, B.; de Clercq, I.; Chiwocha, S.; Fenske, R.; Prinsen, E.; Boerjan, W.; et al. Perturbation of indole-3-butyric acid homeostasis by the UDP-glucosyltransferase UGT74E2 modulates Arabidopsis architecture and water stress tolerance. Plant Cell 2010, 22, 2660–2679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouzounidou, G.; Ilias, I. Hormone-induced protection of sunflower photosynthetic apparatus against copper toxicity. Biol. Plant. 2005, 49, 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anuradha, S.; Rao, S.S.R. Application of brassinosteroids to rice seeds (Oryza sativa L.) reduced the impact of salt stress on growth, prevented photosynthetic pigment loss and increased nitrate reductase activity. Plant Growth Regul. 2003, 40, 29–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayat, S.; Ali, B.; Aiman Hasan, S.; Ahmad, A. Brassinosteroid enhanced the level of antioxidants under cadmium stress in Brassica juncea. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2007, 60, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janeczko, A.; Koscielniak, J.; Pilipowicz, M.; Szarek-Lukaszewska, G.; Skoczowski, A. Protection of winter rape photosystem 2 by 24-epibrassinolide under cadmium stress. Photosynthetica 2005, 43, 293–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, B.; Hasan, S.A.; Hayat, S.; Hayat, Q.; Yadav, S.; Fariduddin, Q.; Ahmad, A. A role for brassinosteroids in the amelioration of aluminium stress through antioxidant system in mung bean (Vigna radiata L. Wilczek). Environ. Exp. Bot. 2008, 62, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.Q.; Huang, L.F.; Hu, W.H.; Zhou, Y.H.; Mao, W.H.; Ye, S.F.; Nogués, S. A role for brassinosteroids in the regulation of photosynthesis in Cucumis sativus. J. Exp. Bot. 2004, 55, 1135–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahammed, G.J.; Choudhary, S.P.; Chen, S.; Xia, X.J.; Shi, K.; Zhou, Y.H.; Yu, J.Q. Role of brassinosteroids in alleviation of phenanthrene–methylation and chromatin patterning cadmium co-contamination-induced photosynthetic inhibition and oxidative stress in tomato. J. Exp. Bot. 2013, 64, 199–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogweno, J.O.; Song, X.S.; Shi, K.; Hu, W.H.; Mao, W.H.; Zhou, Y.H.; Yu, J.Q.; Nogués, S. Brassinosteroids alleviate heat-induced inhibition of photosynthesis by increasing carboxylation efficiency and enhancing antioxidant systems in Lycopersicon esculentum. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2008, 27, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.H.; Yan, X.H.; Xiao, Y.A.; Zeng, J.J.; Qi, H.J.; Ogweno, J.O. 24-Epibrassinosteroid alleviate drought-induced inhibition of photosynthesis in Capsicum annuum. Sci. Hortic. 2013, 150, 232–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivero, R.M.; Gimeno, J.; van Deynze, A.; Walia, H.; Blumwald, E. Enhanced cytokinin synthesis in tobacco plants expressing Psark::IPTprevents the degradation of photosynthetic protein complexes during drought. Plant Cell Physiol. 2010, 51, 1929–1941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, R.; Wang, K.; Shangguan, Z. Cytokinin-induced photosynthetic adaptability of Zea mays L. to drought stress associated with nitric oxide signal: Probed by ESR spectroscopy and fast OJIP fluorescence rise. J. Plant Physiol. 2010, 167, 472–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.I.R.; Khan, N.A. Ethylene reverses photosynthetic inhibition by nickel and zinc in mustard through changes in PS II activity, photosynthetic nitrogen use efficiency, and antioxidant metabolism. Protoplasma 2014, 251, 1007–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iqbal, N.; Nazar, R.; Syeed, S.; Masood, A.; Khan, N.A. Exogenously-sourced ethylene increases stomatal conductance, photosynthesis, and growth under optimal and deficient nitrogen fertilization in mustard. J. Exp. Bot. 2011, 62, 4955–4963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nazar, R.; Khan, M.I.R.; Iqbal, N.; Masood, A.; Khan, N.A. Involvement of ethylene in reversal of salt-inhibited photosynthesis by sulfur in mustard. Physiol. Plant. 2014, 152, 331–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masood, A.; Iqbal, N.; Khan, N.A. Role of ethylene in alleviation of cadmium-induced photosynthetic capacity inhibition by sulphur in mustard. Plant Cell Environ. 2012, 35, 524–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wi, S.J.; Jang, S.J.; Park, K.Y. Inhibition of biphasic ethylene production enhances tolerance to abiotic stress by reducing the accumulation of reactive oxygen species in Nicotiana tabacum. Mol. Cells 2010, 30, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashraf, M.; Karim, F.; Rasul, E. Interactive effects of gibberellic acid (GA3) and salt stress on growth, ion accumulation and photosynthetic capacity of two spring wheat (Triticumaestivum L.) cultivars differing in salt tolerance. Plant Growth Regul. 2002, 36, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.H. Effects of salt stress on mustard as affected by gibberellic acid application. Gen. Appl. Plant Physiol. 2007, 33, 97–106. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M.N.; Siddiqui, M.H.; Mohammad, F.; Naeem, M.; Khan, M.M.A. Calcium chloride and gibberellic acid protect linseed (Linum usitatissimum L.) from NaCl stress by inducing antioxidative defence system and osmoprotectant accumulation. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2010, 32, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, D.J.; Seo, Y.J.; Lee, J.D.; Ishii, R.; Kim, K.U.; Shin, D.H.; Park, S.K.; Jang, S.W.; Lee, I.J. Jasmonic acid differentially affects growth, ion uptake and abscisic acid concentration in salt-tolerant and salt-sensitive rice cultivars. J. Agron. Crop Sci. 2005, 191, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velitcukova, M.; Fedina, I. Response of photosynthesis of Pisum sativum to salt stress as affected by methyl jasmonate. Photosynthetica 1998, 35, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsonev, T.D.; Lazova, G.N.; Stoinova, Z.G.; Popova, L.P. A possible role for jasmonic acid in adaptation of barley seedlings to salinity stress. J. Plant Growth Regul. 1998, 17, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maksymiec, W.; Krupa, Z. Jasmonic acid and heavy metals in Arabidopsis plants—A similar physiological response to both stressors? J. Plant Physiol. 2002, 159, 509–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maksymiec, W.; Wójcik, M.; Krupa, Z. Variation in oxidative stress and photochemical activity in Arabidopsis thaliana leaves subjected to cadmium and excess copper in the presence or absence of jasmonate and ascorbate. Chemosphere 2007, 66, 421–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Q.; Zhao, S.; Ma, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, L.; Li, G.; Hao, L. Endogenous salicylic acid levels and signaling positively regulate Arabidopsisresponse to polyethylene glycol-simulated drought Stress. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2014, 33, 871–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arfan, M.; Athar, H.R.; Ashraf, M. Does exogenous application of salicylic acid through the rooting medium modulate growth and photosynthetic capacity in two differently adapted spring wheat cultivars under salt stress? J. Plant Physiol. 2007, 164, 685–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, H.J.; Zhao, X.J.; Ma, P.F.; Wang, Y.X.; Hu, W.W.; Li, L.H.; Zhao, Y.D. Effects of salicylic acid on protein kinase activity and chloroplast D1 protein degradation in wheat leaves subjected to heat and high light stress. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2011, 31, 259–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, G.; Li, G.; Xu, W.; Peng, X.; Han, Q.; Zhu, Y.; Guo, T. Proteomics reveals the effects of salicylic acid on growth and tolerance to subsequent drought stress in wheat. J. Proteome Res. 2012, 11, 6066–6079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Zhang, L. SA and PEG-induced priming for water stress tolerance in rice seedling. In Information Technology and Agricultural Engineering; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Germany, 2012; Volume 134 AISC, pp. 881–887. [Google Scholar]

- Yusuf, M.; Hasan, S.A.; Ali, B.; Hayat, S.; Fariduddin, Q.; Ahmad, A. Effect of salicylic acid on salinity-induced changes in Brassica juncea. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2008, 50, 1096–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nazar, R.; Umar, S.; Khan, N.A.; Sareer, O. Salicylic acid supplementation improves photosynthesis and growth in mustard through changes in proline accumulation and ethylene formation under drought stress. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2015, 98, 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Dong, Y.; Xu, L.; Kong, J. Effects of foliar applications of nitric oxide and salicylic acid on salt-induced changes in photosynthesis and antioxidative metabolism of cotton seedlings. Plant Growth Regul. 2014, 73, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moussa, H.R.; Khodary, S.E.A. Effect of salicylic acid on the growth, photosynthesis and carbohydrate metabolism in salt-stressed maize plants. Int. J. Agric. Biol. 2004, 6, 5–8. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Li, S. The effects of salicylic acid on distribution of 14C-assimilation and photosynthesis in young grape plants under heat stress. Acta Hortic. 2007, 738, 779–7851. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.J.; Fan, L.; Loescher, W.; Duan, W.; Liu, G.J.; Cheng, J.S.; Luo, H.B.; Li, S.H. Salicylic acid alleviates decreases in photosynthesis under heat stress and accelerates recovery in grapevine leaves. BMC Plant Biol. 2010, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayat, S.; Hasan, S.A.; Fariduddin, Q.; Ahmad, A. Growth of tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum) in response to salicylic acid under water stress. J. Plant Interact. 2008, 3, 297–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abreu, M.E.; Munné-Bosch, S. Salicylic acid may be involved in the regulation of drought-induced leaf senescence in perennials: A case study in field-grown Salvia officinalis L. plants. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2008, 64, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Hu, Y.; Du, X.; Tang, H.; Shen, C.; Wu, J. Salicylic acid alleviates the adverse effects of salt stress in Torreya grandis cv. merrillii seedlings by activating photosynthesis and enhancing antioxidant systems. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e109492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Ha, C.; Leyva-González, M.A.; Osakabe, Y.; Tran, U.T.; Nishiyama, R.; Watanabe, Y.; Tanaka, M.; Seki, M.; Yamaguchi, S.; van Dong, N.; et al. Positive regulatory role of strigolactone in plant responses to drought and salt stress. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 851–856. [Google Scholar]

- Roach, T.; Krieger-Liszkay, A. Regulation of photosynthetic electron transport and photoinhibition. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 2014, 15, 351–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurepin, L.V.; Ivanov, A.G.; Zaman, M.; Pharis, R.P.; Allakhverdiev, S.I.; Hurry, V.; Hüner, N.P.A. Stress-related hormones and glycinebetaine interplay in protection of photosynthesis under abiotic stress conditions. Photosynth. Res. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshioka-Nishimura, M.; Yamamoto, Y. Quality control of photosystem II: The molecular basis for the action of FtsH protease and the dynamics of the thylakoid membranes. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B: Biol. 2014, 137, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rochaix, J.D.; Lemeille, S.; Shapiguzov, A; Samol, I.; Fucile, G.; Willig, A; Goldschmidt-Clermont, M. Protein kinases and phosphatases involved in the acclimation of the photosynthetic apparatus to a changing light environment. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. L. B: Biol. Sci. 2012, 367, 3466–3474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fristedt, R.; Willig, A.; Granath, P.; Crèvecoeur, M.; Rochaix, J.D.; Vener, A.V. Phosphorylation of photosystem II controls functional macroscopic folding of photosynthetic membranes in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2009, 21, 3950–3964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tikkanen, M.; Grieco, M.; Kangasjärvi, S.; Aro, E.M. Thylakoid protein phosphorylation in higher plant chloroplasts optimizes electron transfer under fluctuating light. Plant Physiol. 2010, 152, 723–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kato, Y.; Sun, X.; Zhang, L.; Sakamoto, W. Cooperative D1 degradation in the photosystem II repair mediated by chloroplastic proteases in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2012, 159, 1428–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, L.; Luo, Q.; Yang, C.; Han, Y.; Li, W. A RAV-like transcription factor controls photosynthesis and senescence in soybean. Planta 2008, 227, 1389–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komatsu, T.; Kawaide, H.; Saito, C.; Yamagami, A.; Shimada, S.; Nakazawa, M.; Matsui, M.; Nakano, A.; Tsujimoto, M.; Natsume, M.; et al. The chloroplast protein BPG2 functions in brassinosteroid-mediated post-transcriptional accumulation of chloroplast rRNA. Plant J. 2010, 61, 409–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toledo-Ortiz, G.; Johansson, H.; Lee, K.P.; Bou-Torrent, J.; Stewart, K.; Steel, G.; Rodríguez-Concepción, M.; Halliday, K.J. The HY5-PIF regulatory module coordinates light and temperature control of photosynthetic gene transcription. PLoS Genet. 2014, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, H.; Muramatsu, M.; Hakata, M.; Ueno, O.; Nagamura, Y.; Hirochika, H.; Takano, M.; Ichikawa, H. Ectopic overexpression of the transcription factor OsGLK1 induces chloroplast development in non-green rice cells. Plant Cell Physiol. 2009, 50, 1933–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, W.W.; Muller, O.; Cohu, C.M.; Demmig-Adams, B. May photoinhibition be a consequence, rather than a cause, of limited plant productivity? Photosynth. Res. 2013, 117, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, T.H.H.; Murata, N. Glycinebetaine protects plants against abiotic stress: Mechanisms and biotechnological applications. Plant Cell Environ. 2011, 34, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakamoto, A.; Murata, N. The role of glycine betaine in the protection of plants from stress: Clues from transgenic plants. Plant Cell Environ. 2002, 25, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prasad, K.V.S.K.; Saradhi, P.P. Enhanced tolerance to photoinhibition in transgenic plants through targeting of glycinebetaine biosynthesis into the chloroplasts. Plant Sci. 2004, 166, 1197–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodd, I.C.; Davies, W.J. Hormones and the regulation of water balance. In Plant Hormones; Springer Netherlands: Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 519–548. [Google Scholar]

- Hüner, N.P.A.; Dahal, K.; Kurepin, L.V.; Savitch, L.; Singh, J.; Ivanov, A.G.; Kane, K.; Sarhan, F. Potential for increased photosynthetic performance and crop productivity in response to climate change: Role of CBFs and gibberellic acid. Front. Chem. 2014, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allard, F.; Houde, M.; Krol, M.; Ivanov, A.; Huner, N.P.A.; Sarhan, F. Betaine improves freezing tolerance in wheat. Plant Cell Physiol. 1998, 39, 1194–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, W.; Rajashekar, C.B. Glycine betaine involvement in freezing tolerance and water stress in Arabidopsis thaliana. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2001, 46, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagendorf, A.T.; Takabe, T. Inducers of glycinebetaine synthesis in barley. Plant Physiol. 2001, 127, 1827–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raghavendra, A.S.; Gonugunta, V.K.; Christmann, A.; Grill, E. ABA perception and signalling. Trends Plant Sci. 2010, 15, 395–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamburenko, M.V.; Zubo, Y.O.; Vanková, R.; Kusnetsov, V.V.; Kulaeva, O.N.; Börner, T. Abscisic acid represses the transcription of chloroplast genes. J. Exp. Bot. 2013, 64, 4491–4502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ton, J.; Flors, V.; Mauch-Mani, B. The multifaceted role of ABA in disease resistance. Trends Plant Sci. 2009, 14, 310–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirayama, T.; Shinozaki, K. Perception and transduction of abscisic acid signals: Keys to the function of the versatile plant hormone ABA. Trends Plant Sci. 2007, 12, 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinheiro, C.; Chaves, M.M. Photosynthesis and drought: Can we make metabolic connections from available data? J. Exp. Bot. 2011, 62, 869–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barickman, T.C.; Kopsell, D.A.; Sams, C.E. Abscisic acid increases carotenoid and chlorophyll concentrations in leaves and fruit of two tomato genotypes. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 2014, 139, 261–266. [Google Scholar]

- Blankenship, R.E.; Hartman, H. The origin and evolution of oxygenic photosynthesis. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1998, 23, 94–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillier, W.; Messinger, J. Mechanism of photosynthetic oxygen production. Photosyst. II 2005, 567–608. [Google Scholar]

- Dall’Osto, L.; Cazzaniga, S.; Havaux, M.; Bassi, R. Enhanced photoprotection by protein-bound vs free xanthophyll pools: A comparative analysis of chlorophyll b and xanthophyll biosynthesis mutants. Mol. Plant 2010, 3, 576–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demmig-Adams, B.; Adams, W.W.; Ebbert, V.; Logan, B.A. Ecophysiology of the xanthophyll cycle. Photochem. Carotenoids 2004, 8, 245–269. [Google Scholar]

- Milborrow, B.V. The pathway of biosynthesis of abscisic acid in vascular plants: A review of the present state of knowledge of ABA biosynthesis. J. Exp. Bot. 2001, 52, 1145–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballottari, M.; Dall’Osto, L.; Morosinotto, T.; Bassi, R. Contrasting behavior of higher plant photosystem I and II antenna systems during acclimation. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 8947–8958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grewe, S.; Ballottari, M.; Alcocer, M.; D’Andrea, C.; Blifernez-Klassen, O.; Hankamer, B.; Mussgnug, J.H.; Bassi, R.; Kruse, O. Light-harvesting complex protein LHCBM9 is critical for photosystem II activity and hydrogen production in chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Plant Cell 2014, 26, 1598–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, R.; Xu, Y.H.; Jiang, S.C.; Lu, K.; Lu, Y.F.; Feng, X.J.; Wu, Z.; Liang, S.; Yu, Y.T.; Wang, X.F.; et al. Light-harvesting chlorophyll a/b-binding proteins, positively involved in abscisic acid signalling, require a transcription repressor, WRKY40, to balance their function. J. Exp. Bot. 2013, 64, 5443–5456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weatherwax, S.C.; Ong, M.S.; Degenhardt, J.; Bray, E.A; Tobin, E.M. The interaction of light and abscisic acid in the regulation of plant gene expression. Plant Physiol. 1996, 111, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, Y.C.; Walling, L.L. Abscisic acid negatively regulates expression of chlorophyll a/bbinding protein genes during soybean embryogeny. Plant Physiol. 1991, 97, 1260–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartholomew, D.M.; Bartley, G.E.; Scolnik, P. A Abscisic acid control of rbcS and cabtranscription in tomato leaves. Plant Physiol. 1991, 96, 291–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barber, J.; Nield, J.; Morris, E.; Zheleva, D.; Hankamer, B. The structure, function and dynamics of photosystem two. Physiol. Plant. 1997, 100, 817–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambreva, M.D.; Russo, D.; Polticelli, F.; Scognamiglio, V.; Antonacci, A.; Zobnina, V.; Campi, G.; Rea, G. Structure/function/dynamics of photosystem II plastoquinone binding sites. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 2014, 15, 285–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lundin, B.; Hansson, M.; Schoefs, B.; Vener, A.V.; Spetea, C. The Arabidopsis PsbO2 protein regulates dephosphorylation and turnover of the photosystem II reaction centre D1 protein. Plant J. 2007, 49, 528–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi, X.; McChargue, M.; Laborde, S.; Frankel, L.K.; Bricker, T.M. The manganese-stabilizing protein is required for photosystem II assembly/stability and photoautotrophy in higher plants. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 16170–16174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pawłowicz, I.; Kosmala, A.; Rapacz, M. Expression pattern of the psbO gene and its involvement in acclimation of the photosynthetic apparatus during abiotic stresses in Festuca arundinacea and F. pratensis. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2012, 34, 1915–1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dashevskaya, S.; Horn, R.; Chudobova, I.; Schillberg, S.; Vélez, S.M.R.; Capell, T.; Christou, P. Abscisic acid and the herbicide safener cyprosulfamide cooperatively enhance abiotic stress tolerance in rice. Mol. Breed. 2013, 32, 463–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volfová, A.; Chvojka, L.; Friedrich, A. The effect of kinetin and auxin on the chloroplast structure and chlorophyll content in wheat coleoptiles. Biol. Plant. 1978, 20, 440–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tognetti, V.B.; Mühlenbock, P.; van Breusegem, F. Stress homeostasis—The redox and auxin perspective. Plant Cell Environ. 2012, 35, 321–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehlert, B.; Schöttler, M.A.; Tischendorf, G.; Ludwig-Müller, J.; Bock, R. The paramutated SULFUREA locus of tomato is involved in auxin biosynthesis. J. Exp. Bot. 2008, 59, 3635–3647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agami, R.A.; Mohamed, G.F. Exogenous treatment with indole-3-acetic acid and salicylic acid alleviates cadmium toxicity in wheat seedlings. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2013, 94, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.H.; Shan, X.Q.; Wen, B.; Owens, G.; Fang, J.; Zhang, S.Z. Effect of indole-3-acetic acid on lead accumulation in maize (Zea mays L.) seedlings and the relevant antioxidant response. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2007, 61, 246–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramel, F.; Birtic, S.; Cuine, S.; Triantaphylides, C.; Ravanat, J.L.; Havaux, M. Chemical quenching of singlet oxygen by carotenoids in plants. Plant Physiol. 2012, 158, 1267–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Nagpal, P.; Vitart, V.; McMorris, T.C.; Chory, J. A role for brassinosteroids in light-dependent development of Arabidopsis. Science 1996, 272, 398–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, M.Y.; Shang, J.X.; Oh, E.; Fan, M.; Bai, Y.; Zentella, R.; Sun, T.; Wang, Z.Y. Brassinosteroid, gibberellin and phytochrome impinge on a common transcription module in Arabidopsis. Nat. Cell Biol. 2012, 14, 810–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.; Trieu, A.; Radhakrishnan, P.; Kwok, S.F.; Harris, S.; Zhang, K.; Wang, J.; Wan, J.; Zhai, H.; Takatsuto, S.; et al. Brassinosteroids regulate grain filling in rice. Plant Cell 2008, 20, 2130–2145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.; Yu, D. BRASSINOSTEROID INSENSITIVE2 interacts with ABSCISIC ACID INSENSITIVE5 to mediate the antagonism of brassinosteroids to abscisic acid during seed germination in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Online 2014, 26, 4394–4408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, J.Y.; Sae-Seaw, J.; Wang, Z.Y. Brassinosteroid signalling. Development 2013, 140, 1615–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, M.H.; Sun, J.; Oh, D.H.; Zielinski, R.E.; Clouse, S.D.; Huber, S.C. Enhancing Arabidopsis leaf growth by engineering the BRASSINOSTEROID INSENSITIVE1 receptor kinase. Plant Physiol. 2011, 157, 120–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, M.H.; Wang, X.; Clouse, S.D.; Huber, S.C. Deactivation of the Arabidopsis BRASSINOSTEROID INSENSITIVE 1 (BRI1) receptor kinase by autophosphorylation within the glycine-rich loop. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 327–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, X.J.; Huang, L.F.; Zhou, Y.H.; Mao, W.H.; Shi, K.; Wu, J.X.; Asami, T.; Chen, Z.; Yu, J.Q. Brassinosteroids promote photosynthesis and growth by enhancing activation of Rubisco and expression of photosynthetic genes in Cucumis sativus. Planta 2009, 230, 1185–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, T.W.; Michniewicz, M.; Bergmann, D.C.; Wang, Z.Y. Brassinosteroid regulates stomatal development by GSK3-mediated inhibition of a MAPK pathway. Nature 2012, 482, 419–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasan, S.A.; Hayat, S.; Ali, B.; Ahmad, A. 28-Homobrassinolide protects chickpea (Cicerarietinum) from cadmium toxicity by stimulating antioxidants. Environ. Pollut. 2008, 151, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holá, D. Brassinosteroids: A Class of Plant Hormone; Hayat, S., Ahmad, A., Eds.; Springer Science & Business Media: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Rothová, O.; Holá, D.; Kočová, M.; Tůmová, L.; Hnilička, F.; Hniličková, H.; Kamlar, M.; Macek, T. 24-Epibrassinolide and 20-hydroxyecdysone affect photosynthesis differently in maize and spinach. Steroids 2014, 85, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polanská, L.; Vičánková, A.; Nováková, M.; Malbeck, J.; Dobrev, P.I.; Brzobohatý, B.; Vaňková, R.; Macháčková, I. Altered cytokinin metabolism affects cytokinin, auxin, and abscisic acid contents in leaves and chloroplasts, and chloroplast ultrastructure in transgenic tobacco. J. Exp. Bot. 2007, 58, 637–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivero, R.M.; Shulaev, V.; Blumwald, E. Cytokinin-dependent photorespiration and the protection of photosynthesis during water deficit. Plant Physiol. 2009, 150, 1530–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivero, R.M.; Kojima, M.; Gepstein, A.; Sakakibara, H.; Mittler, R.; Gepstein, S.; Blumwald, E. Delayed leaf senescence induces extreme drought tolerance in a flowering plant. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 19631–19636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iqbal, N.; Trivellini, A.; Masood, A.; Ferrante, A.; Khan, N.A. Current understanding on ethylene signaling in plants: The influence of nutrient availability. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2013, 73, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tari, I.; Csiszár, J. Effects of NO2−or NO3−supply on polyamine accumulation and ethylene production of wheat roots at acidic and neutral pH: Implications for root growth. Plant Growth Regul. 2003, 40, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larkindale, J.; Knight, M.R. Protection against heat stress-induced oxidative damage in Arabidopsis involves calcium, abscisic acid, ethylene, and salicylic acid. Plant Physiol. 2002, 128, 682–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iqbal, N.; Nazar, R.; Khan, M.I.R.; Khan, N.A. Variation in photosynthesis and growth of mustard cultivars: Role of ethylene sensitivity. Sci. Hortic. 2012, 135, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.A.; Mir, M.R.; Nazar, R.; Singh, S. The application of ethephon (an ethylene releaser) increases growth, photosynthesis and nitrogen accumulation in mustard (Brassica juncea L.) under high nitrogen levels. Plant Biol. 2008, 10, 534–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magome, H.; Yamaguchi, S.; Hanada, A.; Kamiya, Y.; Oda, K. Dwarf anddelayed-flowering 1, a novel Arabidopsis mutant deficient in gibberellin biosynthesis because of overexpression of a putative AP2 transcription factor. Plant J. 2004, 37, 720–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iqbal, M.; Ashraf, M. Gibberellic acid mediated induction of salt tolerance in wheat plants: Growth, ionic partitioning, photosynthesis, yield and hormonal homeostasis. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2013, 86, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.; Xu, D. Stimulation effect of gibberellic acid short-term treatment on leaf photosynthesis related to the increase in Rubisco content in broad bean and soybean. Photosynth. Res. 2001, 68, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coles, J.P.; Phillips, A.L.; Croker, S.J.; García-Lepe, R.; Lewis, M.J.; Hedden, P. Modification of gibberellin production and plant development in Arabidopsis by sense and antisense expression of gibberellin 20-oxidase genes. Plant J. 1999, 17, 547–556. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dijkstra, P.; Reegen, H.; Kuiper, P.J. Relation between relative growth rate, endogenous gibberellins, and the response to applied gibberellic acid for Plantago major. Physiol. Plant. 1990, 79, 629–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cramer, M.D.; Cramer, M.D.; Nagel, O.W.; Lips, S.H.; Lips, S.H.; Lambers, H.; Lambers, H. Reduction, assimilation and transport of N in normal and gibberellin-deficient tomato plants. Physiol. Plant. 1995, 95, 347–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biemelt, S.; Tschiersch, H.; Sonnewald, U. Impact of altered gibberellin metabolism on biomass accumulation, lignin biosynthesis, and photosynthesis in transgenic tobacco plants. Plant Physiol. 2004, 135, 254–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuna, A.L.; Kaya, C.; Dikilitas, M.; Higgs, D. The combined effects of gibberellic acid and salinity on some antioxidant enzyme activities, plant growth parameters and nutritional status in maize plants. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2008, 62, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afroz, S.; Mohammad, F.; Hayat, S.; Siddiqui, M.H. Exogenous application of gibberellic acid counteracts the Ill effect of sodium chloride in mustard. J. Plant Physiol. 2005, 29, 233–236. [Google Scholar]

- Ghorbanli, M.; Kaveh, S.; Sepehr, M. Effects of cadmium and gibberellin on growth and photosynthesis of Glycine max. Photosynthetica 1999, 37, 627–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouzounidou, G.; Papadopoulou, P.; Giannakoula, A.; Ilias, I. Plant growth regulators treatments modulate growth, physiology and quality characteristics of Cucumis Melo L. Plants. Pak. J. Bot. 2008, 40, 1185–1193. [Google Scholar]

- Gratão, P.L.; Monteiro, C.C.; Rossi, M.L.; Martinelli, A.P.; Peres, L.E.P.; Medici, L.O.; Lea, P. J.; Azevedo, R.A. Differential ultrastructural changes in tomato hormonal mutants exposed to cadmium. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2009, 67, 387–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, R.; Macfie, S.M.; Ding, Z. Cadmium-induced plant stress investigated by scanning electrochemical microscopy. J. Exp. Bot. 2005, 56, 2831–2838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wasternack, C. Jasmonates: An update on biosynthesis, signal transduction and action in plant stress response, growth and development. Ann. Bot. 2007, 100, 681–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eyidogan, F.; Oz, M.T.; Yucel, M.; Oktem, H.A. Signal transduction of phytohormones under abiotic stresses. In Phytohormones and Abiotic Stress Tolerance in Plants; Khan, N.A., Nazar, R., et al., Eds.; Springer Science & Business Media: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 1–49. [Google Scholar]

- De Ollas, C.; Hernando, B.; Arbona, V.; Gómez-Cadenas, A. Jasmonic acid transient accumulation is needed for abscisic acid increase in citrus roots under drought stress conditions. Physiol. Plant. 2013, 147, 296–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Attaran, E.; Major, I.T.; Cruz, J.A.; Rosa, B.A.; Koo, A.J.K.; Chen, J.; Kramer, D.M.; He, S.Y.; Howe, G.A. Temporal dynamics of growth and photosynthesis suppression in response to jasmonate signaling. Plant Physiol. 2014, 165, 1302–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raskin, I. Role of salicylic acid in plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 1992, 43, 439–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayat, S.; Ali, B.; Ahmad, A. Salicyclic acid: biosynthesis, metabolism and physiological role in plants. In Salicylic Acid: A Plant Hormone; Hayat, S., Ahmad, A., Eds.; Springer Netherlands: Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Rivas-San Vicente, M.; Plasencia, J. Salicylic acid beyond defence: Its role in plant growth and development. J. Exp. Bot. 2011, 62, 3321–3338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mateo, A.; Funck, D.; Mühlenbock, P.; Kular, B.; Mullineaux, P.M.; Karpinski, S. Controlled levels of salicylic acid are required for optimal photosynthesis and redox homeostasis. J. Exp. Bot. 2006, 57, 1795–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nazar, R.; Umar, S.; Khan, N.A. Exogenous salicylic acid improves photosynthesis and growth through increase in ascorbate-glutathione metabolism and S assimilation in mustard under salt stress. Plant Signal. Behav. 2015, 10, e1003751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janda, K.; Hideg, É.; Szalai, G.; Kovács, L.; Janda, T. Salicylic acid may indirectly influence the photosynthetic electron transport. J. Plant Physiol. 2012, 169, 971–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balint, I.; Bhattacharya, J.; Perelman, A.; Schatz, D.; Moskovitz, Y.; Keren, N.; Schwarz, R. Inactivation of the extrinsic subunit of photosystem II, PsbU, in Synechococcus PCC 7942 results in elevated resistance to oxidative stress. FEBS Lett. 2006, 580, 2117–2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Ronde, J.A.; Cress, W.A.; Krüger, G.H.J.; Strasser, R.J.; van Staden, J. Photosynthetic response of transgenic soybean plants, containing an Arabidopsis P5CR gene, during heat and drought stress. J. Plant Physiol. 2004, 161, 1211–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allakhverdiev, S.I.; Kreslavski, V.D.; Klimov, V.V.; Los, D.A.; Carpentier, R.; Mohanty, P. Heat stress: An overview of molecular responses in photosynthesis. Photosynth. Res. 2008, 98, 541–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dat, J.F.; Lopez-Delgado, H.; Foyer, C.H.; Scott, I.M. Parallel changes in H2O2 and catalase during thermotolerance induced by salicylic acid or heat acclimation in mustard seedlings1. Plant Physiol. 1998, 116, 1351–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez-Delgado, H.; Dat, J.F.; Foyer, C.H.; Scott, I.M. Induction of thermotolerance in potato microplants by acetylsalicylic acid and H2O2. J. Exp. Bot. 1998, 49, 713–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Tayeb, M.A. Response of barley grains to the interactive effect of salinity and salicylic acid. Plant Growth Regul. 2005, 45, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.A.; Syeed, S.; Masood, A.; Nazar, R.; Iqbal, N. Application of salicylic acid increases contents of nutrients and antioxidative metabolism in mungbean and alleviates adverse effects of salinity stress. Int. J. Plant Biol. 2010, 1, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, E.N.; Silveira, J.A.G.; Ferreira-Silva, S.L.; Viégas, R.A. Salicylic acid mitigates salinity effects by enhancing the growth, CO2 assimilation, and antioxidant protection in Jatropha curcas plants. Indian J. Plant Physiol. 2014, 19, 345–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Usha, K. Salicylic acid induced physiological and biochemical changes in wheat seedlings under water stress. Plant Growth Regul. 2003, 39, 137–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loutfy, N.; El-Tayeb, M.A.; Hassanen, A.M.; Moustafa, M.F.M.; Sakuma, Y.; Inouhe, M. Changes in the water status and osmotic solute contents in response to drought and salicylic acid treatments in four different cultivars of wheat (Triticum aestivum). J. Plant Res. 2012, 125, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anosheh, H.P. Exogenous application of salicylic acid and chlormequat chloride alleviates negative effects of drought stress in wheat. Adv. Stud. Biol. 2012, 4, 501–520. [Google Scholar]

- Horváth, E.; Pál, M.; Szalai, G.; Páldi, E.; Janda, T. Exogenous 4-hydroxybenzoic acid and salicylic acid modulate the effect of short-term drought and freezing stress on wheat plants. Biol. Plant. 2007, 51, 480–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waseem, M.; Athar, H.U.R.; Ashraf, M. Effect of salicylic acid applied through rooting medium on drought tolerance of wheat. Pak. J. Bot. 2006, 38, 1127–1136. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, G.Z.; Li, G.Z.; Liu, G.Q.; Xu, W.; Peng, X.Q.; Wang, C.Y.; Zhu, Y.J.; Guo, T.C. Exogenous salicylic acid enhances wheat drought tolerance by influence on the expression of genes related to ascorbate-glutathione cycle. Biol. Plant. 2013, 57, 718–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, S.R.; Qayyum, A.; Razzaq, A.; Ahmad, M.; Mahmood, I.; Sher, A. Role of foliar application of salicylic acid and l-tryptophan in drought tolerance of maize. J. Anim. Plant Sci. 2012, 22, 768–772. [Google Scholar]

- Saruhan, N.; Saglam, A.; Kadioglu, A. Salicylic acid pretreatment induces drought tolerance and delays leaf rolling by inducing antioxidant systems in maize genotypes. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2012, 34, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, M.; Basra, S.M.A.; Wahid, A.; Ahmad, N.; Saleem, B.A. Improving the drought tolerance in rice (Oryza sativa L.) by exogenous application of salicylic acid. J. Agron. Crop Sci. 2009, 195, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.L.; Li, X.M.; Zhang, L.H. Effect of salicylic acid pretreatment on drought stress responses of zoysiagrass (Zoysia japonica). Russ. J. Plant Physiol. 2014, 61, 619–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Babili, S.; Bouwmeester, H.J. Strigolactones, a novel carotenoid-derived plant hormone. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2015, 66, 161–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waldie, T.; McCulloch, H.; Leyser, O. Strigolactones and the control of plant development: Lessons from shoot branching. Plant J. 2014, 79, 607–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mashiguchi, K.; Sasaki, E.; Shimada, Y.; Nagae, M.; Ueno, K.; Nakano, T.; Yoneyama, K.; Suzuki, Y.; Asami, T. Feedback-regulation of strigolactone biosynthetic genes and strigolactone-regulated genes in Arabidopsis. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2009, 73, 2460–2465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quain, M.D.; Makgopa, M.E.; Márquez-García, B.; Comadira, G.; Fernandez-Garcia, N.; Olmos, E.; Schnaubelt, D.; Kunert, K.J.; Foyer, C.H. Ectopic phytocystatin expression leads to enhanced drought stress tolerance in soybean (Glycine max) and Arabidopsis thaliana through effects on strigolactone pathways and can also result in improved seed traits. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2014, 903–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pospíšilová, J. Participation of phytohormones in the stomatal regulation of gas exchange during water stress. Biol. Plant. 2003, 46, 491–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaudoin, N.; Serizet, C.; Gosti, F.; Giraudat, J. Interactions between abscisic acid and ethylene signaling cascades. Plant Cell 2000, 12, 1103–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kohli, A.; Sreenivasulu, N.; Lakshmanan, P.; Kumar, P.P. The phytohormone crosstalk paradigm takes center stage in understanding how plants respond to abiotic stresses. Plant Cell Rep. 2013, 32, 945–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, A.J.; Jackson, A.C.; Symonds, R.C.; Mulholland, B.J.; Dadswell, A.R.; Blake, P.S.; Burbidge, A.; Taylor, I.B. Ectopic expression of a tomato 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase gene causes over-production of abscisic acid. Plant J. 2000, 23, 363–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gururani, M.A.; Mohanta, T.K.; Bae, H. Current Understanding of the Interplay between Phytohormones and Photosynthesis under Environmental Stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 19055-19085. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms160819055

Gururani MA, Mohanta TK, Bae H. Current Understanding of the Interplay between Phytohormones and Photosynthesis under Environmental Stress. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2015; 16(8):19055-19085. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms160819055

Chicago/Turabian StyleGururani, Mayank Anand, Tapan Kumar Mohanta, and Hanhong Bae. 2015. "Current Understanding of the Interplay between Phytohormones and Photosynthesis under Environmental Stress" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 16, no. 8: 19055-19085. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms160819055

APA StyleGururani, M. A., Mohanta, T. K., & Bae, H. (2015). Current Understanding of the Interplay between Phytohormones and Photosynthesis under Environmental Stress. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 16(8), 19055-19085. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms160819055