1. Introduction

Legionella are Gram-negative bacilli that are highly successful in colonizing natural and artificial aquatic environments. Dissemination in the environment is facilitated by their characteristic biphasic lifestyle;

Legionella may adapt to distinct intracellular and aquatic environments by alternating between a “replicative” and a “virulent” form in response to growth conditions. In water systems,

Legionella infects and replicates within protozoa, colonize surfaces, and grow in biofilms [

1]. Bacteria enclosed in water-air aerosol are inhaled into the lower respiratory tract and subsequently engulfed by enteric pulmonary macrophages. The capability of

Legionella of intracellular proliferation in immune cells designed to kill bacteria and using them as their host cell is crucial for development of pneumonia known as Legionnaires’ disease. Currently, the family

Legionellaceae is composed of 58 species isolated from environmental sources, but 21 of them have been isolated from humans [

2,

3]. Among

Legionella species that cause human pneumonia,

L. pneumophila is the most common causative agent, while

L. dumoffii is the fourth [

4]. Pneumonia caused by

L. dumoffii is rapidly progressive and fulminant owing to the ability of this bacterium to invade and proliferate in human alveolar epithelial cells [

5]. The disease is often fatal, especially in immunocompromised patients.

L. dumoffii has been isolated from pericarditis, prosthetic valve endocarditis, and septic arthritis, which indicates that

L. dumoffii is responsible for extrapulmonary infections [

6,

7].

The way of bacterial penetration into the host cell and factors indispensable for settling the specific microniche,

i.e., the digestive vacuole, are dependent on virulence factors released from the cell, unique properties of surface components, and the ability to utilize host metabolites. Crucially for the biogenesis and maintenance of the bacterial replicative vacuole,

L. pneumophila uses a type IV secretion system (Dot/Icm) to deliver a large number of effector proteins to the host cell [

8]. The coordinate actions of the bacterial effectors allow

Legionella to subvert innate immune response and evade host destruction. Moreover, the components of the cell envelope: proteins, peptidoglycan, lipopolysaccharide (LPS), and phospholipids participate in the highly specific

Legionella-host interactions.

Legionella phospholipids are characterized by a high phosphatidylcholine (PC) content, which is untypical of bacteria and specific for a narrow group of pathogenic and symbiotic microbes whose life cycle is strictly associated with eukaryotic cells. PC is a major component of eukaryotic cell membranes and plays a significant role in signal transduction. The high PC content in intracellular membranes of pathogens, such as

Legionella, makes the cells of the microbes similar to the host cells. Bacteria synthesize PC via two different routes,

i.e., the phospholipid

N-methylation (Pmt) or the phosphatidylcholine synthase (Pcs) pathway. In the Pmt pathway, phosphatidylethanolamine is methylated three times to yield PC in reactions catalyzed by one or several phospholipid

N-methyltransferases (PMTs). In the Pcs pathway, choline is condensed directly with CDP-diacylglyceride to form PC in a reaction catalyzed by a bacterium-specific Pcs enzyme [

9]. Since choline is not a biosynthetic product of prokaryotes, the Pcs pathway is probably a direct sensor of environmental conditions, using choline availability as an indicator of the status of the location in which the bacterium is found. It has been shown that

L. pneumophila and

L. bozemanae are capable of utilisation of exogenous choline for PC synthesis [

10,

11]. Apart from the structural role, the exact function of PC in

Legionella cells remains unexplained. However, PC-deficient mutants of

L. pneumophila exhibited attenuated virulence and increased susceptibility to macrophage-mediated killing. These defects were attributed to reduced bacterial binding to macrophages and a poorly functioning Dot/Icm system. In the process of binding to macrophages,

L. pneumophila uses the platelet-activating factor receptor (PAF receptor), which harbors the same glycerophosphocholine head group as PC. Due to this structural similarity, PC is required for efficient binding of

L. pneumophila to macrophages via the PAF receptor [

12].

In response to infection caused by

Legionella, macrophages produce inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin 6 (IL-6), interleukin 1α (IL-1α), interleukin 1β (IL-1β), interleukin 12 (IL-12), interferon γ (INF γ), and tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) [

13]. Among these cytokines, TNF-α appears to be pivotal for activation of phagocytes and resolution of pneumonic infection [

14,

15]. Treatment of rat alveolar macrophages with TNF-α resulted in decreased intracellular growth of

L. pneumophila [

16]. In turn, inhibition of endogenous TNF-α activity via TNF-α-neutralizing antibodies resulted in enhanced growth of

L. pneumophila in the mouse lung [

17]. However, little is known about how the pathogen PC influences the induction of proinflammatory cytokines in the host.

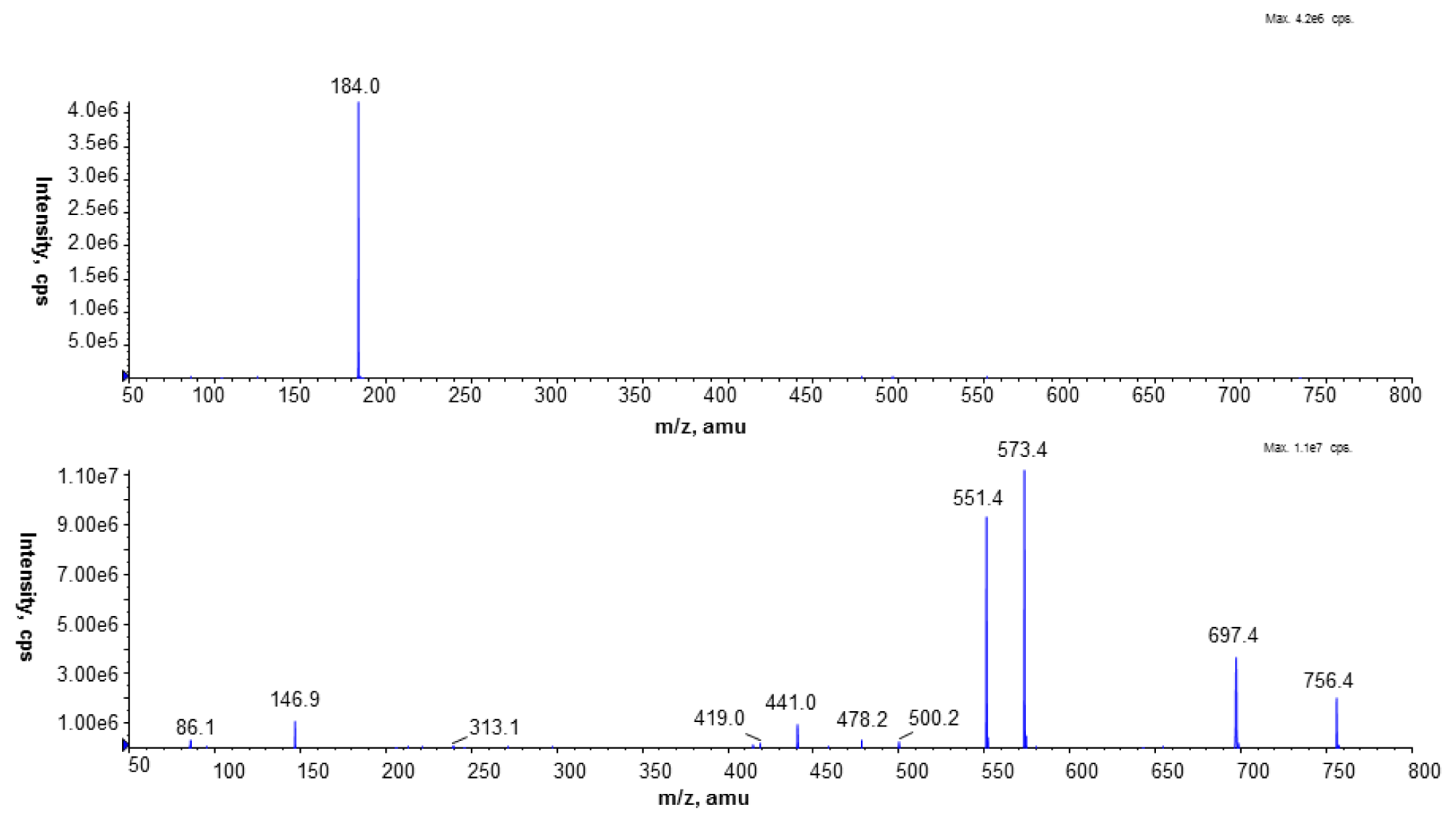

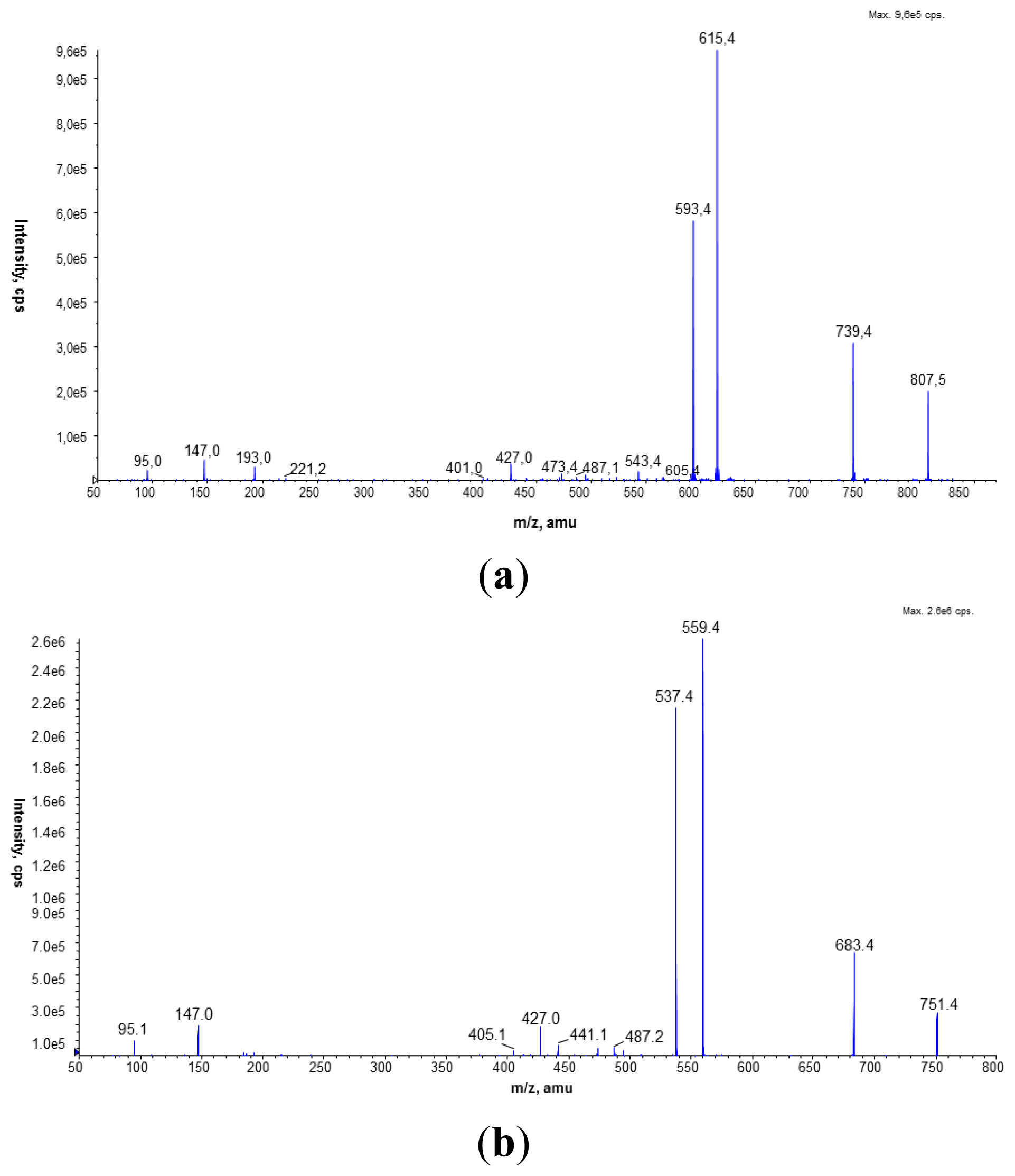

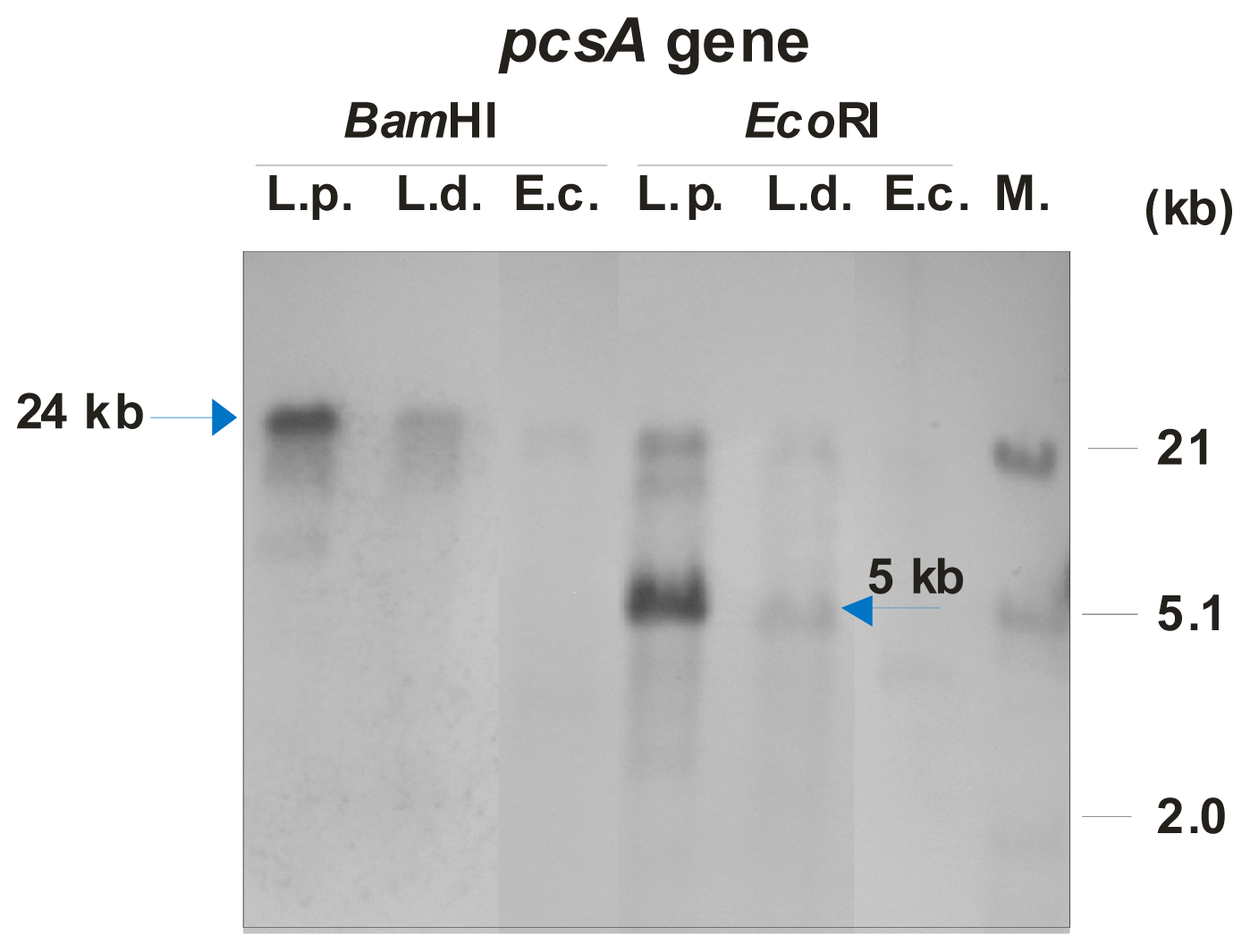

The aim of our study was to investigate the ability of L. dumoffii to utilize exogenous choline for PC synthesis using Matrix-Assisted Laser-Desorption/Ionization (MALDI)-Time of Flight (TOF) MALDI/TOF and Liquid Chromatography Coupled with the Mass Spectrometry Technique Using the Electrospray Ionization Technique (LC/ESI-MS) techniques. We also wanted to determine whether the bacteria use the Pcs pathway for PC synthesis by identification of a pcsA gene encoding phosphatidylcholine synthase. Next, the correlations between the PC species content in the L. dumoffii membranes and the level of TNF-α produced by human macrophages were investigated.

3. Discussion

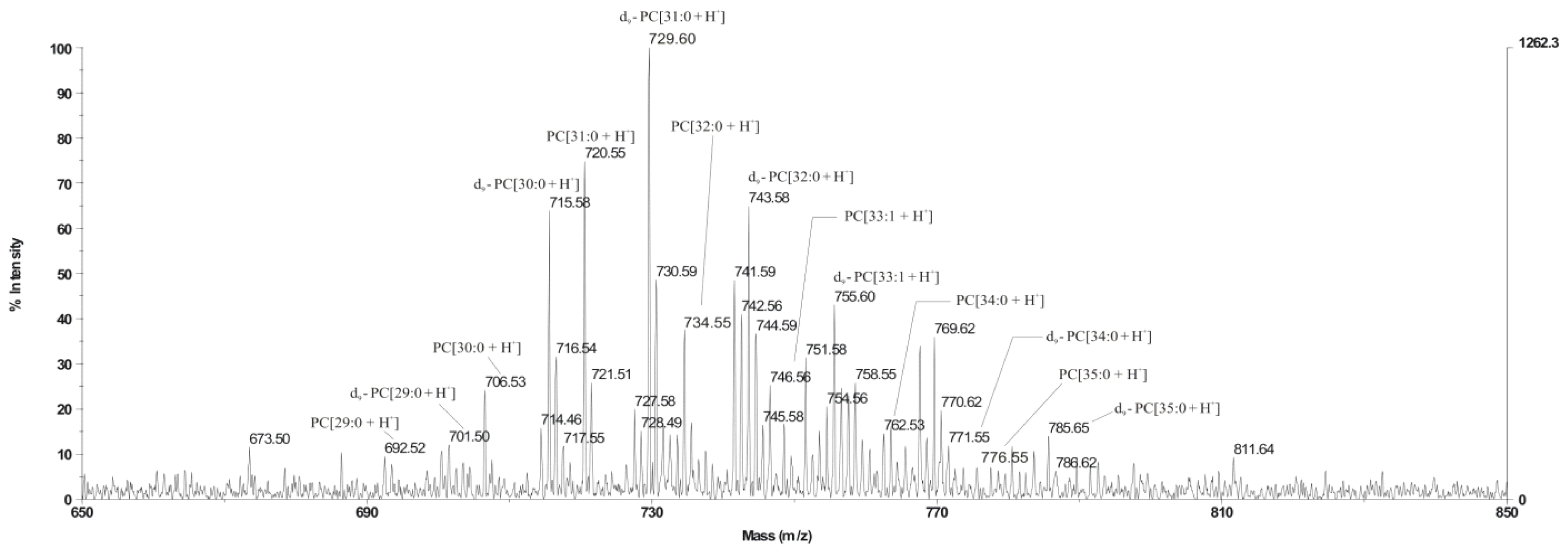

Our previous and current investigations showed that

L. lytica,

L. bozemanae, and

L. dumoffii form PC [

11,

22]. In this study, the ability of

L. dumoffii to synthesize PC in a choline-dependent manner was investigated. It was evidenced that the bacteria used exogenous choline for PC synthesis via the Pcs pathway. The main PC d9-PC[31:0 + H]

+, identified on the MALDI/TOF spectrum and synthesised via this pathway, was confirmed by LC/ESI-MS as PC 16:0/15:0, also identified in

L. bozemanae. Both species exhibit blue-white fluorescence; and the presence of PC 16:0/15:0 is an additional chemotaxonomic feature that classifies both species as representatives of the genus

Fluoribacter in the

Legionellaceae family [

23]. The Pcs pathway in

L. dumoffii was confirmed by identification of the

pcsA gene encoding the phosphatidylcholine synthase. All

Legionella spp. genomes characterized so far contain the

pcsA gene encoding phosphatidylcholine synthase, suggesting a significant function of this protein in their metabolism. Previously, we have identified the

pcsA gene in

L. bozemanae and found that PC is effectively produced in a one-step pathway, in which the PcsA enzyme is engaged [

11]. Likewise, the

L. dumoffii PcsA presented in this study and

L. bozemanae PcsA exhibited the highest sequence amino acids identity to the

L. longbeachae PcsA, which confirmed genetic relatedness of these three

Legionella species.

The presence of unlabeled PC in the MALDI-TOF spectrum obtained from lipids of bacteria cultured on choline has indicated that

L. dumoffii forms PC also by triple PE methylation. LC/ESI-MS analysis of PC species present in both membranes labeled with a deuterated precursor allowed us to distinguish PC species synthesized from the CDP-choline pathway and the PE methylation pathway. Our previous investigations showed that

L. bozemanae produced PC via two independent pathways PmtA and Pcs [

11]. Similarly, both PC synthesis pathways function in

L. pneumophila. The pathway in which

Legionella spp. utilize exogenous choline is dominant and seems to be more energetically efficient [

10]. However, in the genetic experiments that were conducted (hybridization, PCR analyses using several degenerative primers and amplicon sequencing), we were unable to identify a

pmtA homologue in the

L. dumoffii genome (data not shown). Both PC synthesis pathways have also been reported in legume endosymbionts (

Rhizobium leguminosarum,

Sinorhizobium meliloti,

Bradyrhizobium japonicum) and in the plant pathogen

Agrobacterium tumefaciens. In human pathogens such as

Pseudomonas aeruginosa,

Brucella melitensis, and

Borrelia burgdorferi, PC is produced only via the Pcs pathway [

24].

Several studies have shown that the PC of bacterial membranes can be important to host-associated bacteria in pathogenesis and symbiosis. Our results have indicated that bacteria cultured on choline undergo internalization by THP1 macrophages more readily than bacteria cultured on non-choline-supplemented medium. The increase in internalization in the case of bacteria cultured on choline was not statistically significant, which may suggest a low level of participation of PC species in this process, although other papers indicate that some bacterial PC derivatives play a direct role in association with macrophages [

25].

PC-deficient mutants of

B. japonicum and

S. meliloti were characterized by substantially reduced symbiosis with their plant hosts [

26,

27]. PC is indispensable for the plant pathogen

A. tumefaciens to assembly T4SS components, important factors in formation of plant crown-gall tumors [

28,

29]. A

Brucella abortus pcs mutant exhibited an altered cell envelope; therefore, it did not establish a replication niche inside the macrophages. Additionally, it showed a severe virulence defect in a murine model of infection [

30,

31].

A PC-deficient

P. aeruginosa mutant exhibited the same level of sensitivity to antibiotics and antimicrobial peptides as wild strains. PC deficiency did not change the mobility and capability of biofilm formation on an abiotic surface. However, PC may have a specific role in the interaction with eukaryotic hosts, e.g., it might aid in assembly or localization of specific proteins in

P. aeruginosa [

32].

L. dumoffii cultured on choline-supplemented medium exhibited altered sensitivity to

Galleria mellonella antimicrobial defense factors such as defensin and apoLp-III [

33]. Replacement of PE with PC induced concurrent structural and functional changes in the ABC multidrug exporter of

Lactococcus brevis [

34].

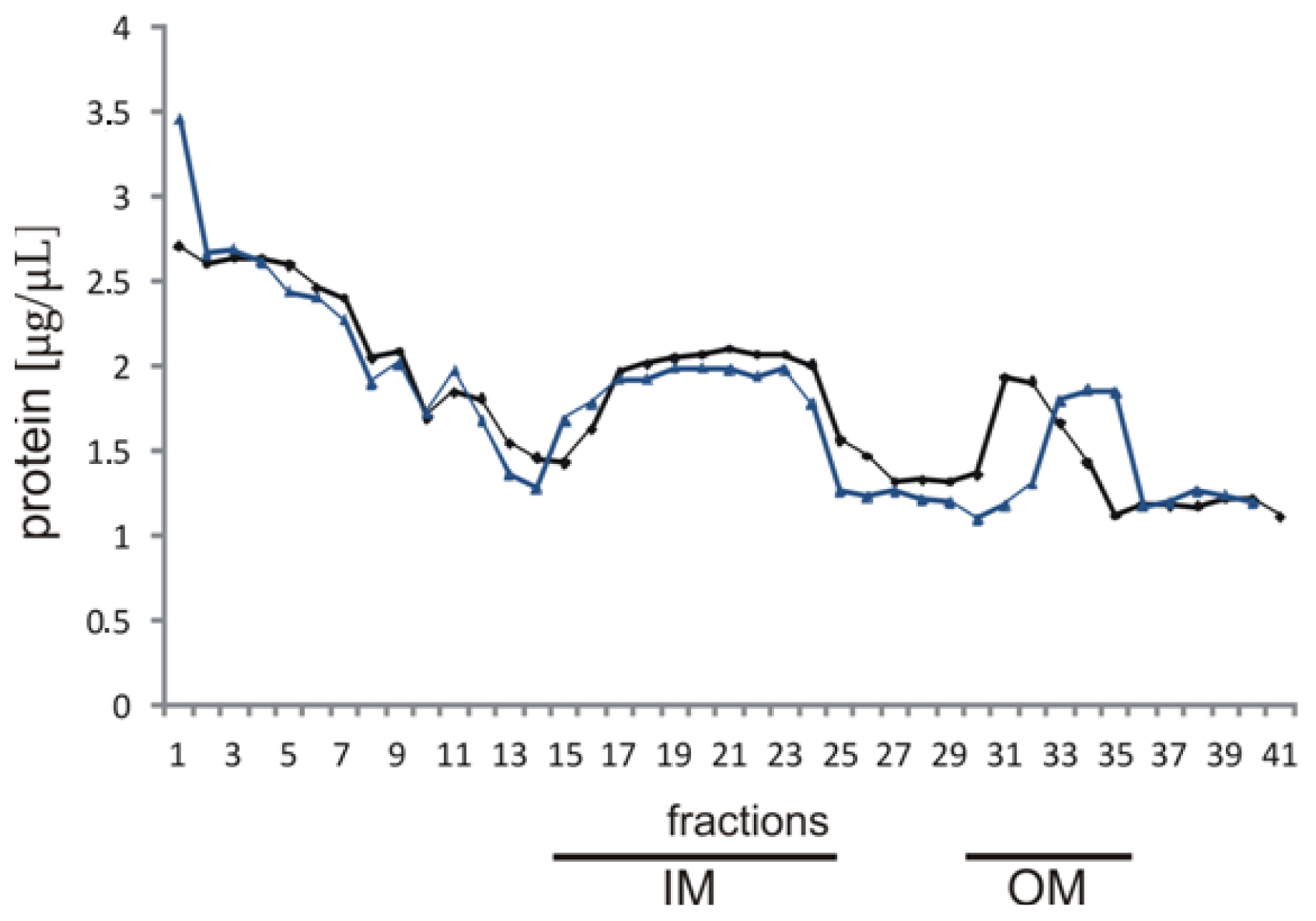

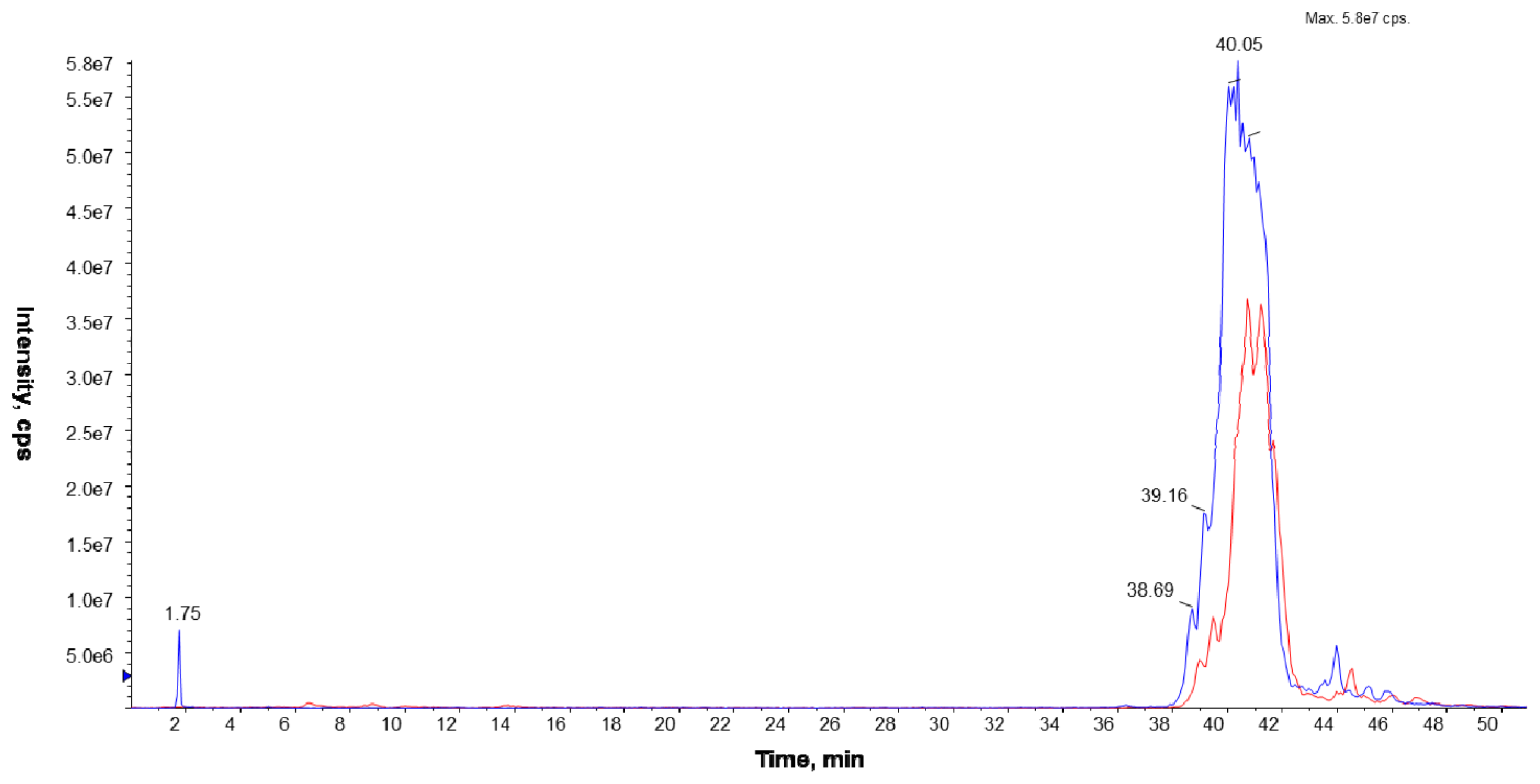

The membrane fraction experiment and LC/ESI-MS analyses suggest that PC in

L. dumoffii is present in the outer and inner membranes. In

L. pneumophila and

P. aeruginosa, PC was also localized in both membrane compartments [

35,

36]. MRM analysis showed that the amount of PC in the inner membrane of

L. dumoffii was higher than in the outer membrane. Moreover, there were differences in the structure of the PC species present in bacteria cultured with and without choline. These differences might be important for interactions of bacteria with host cells.

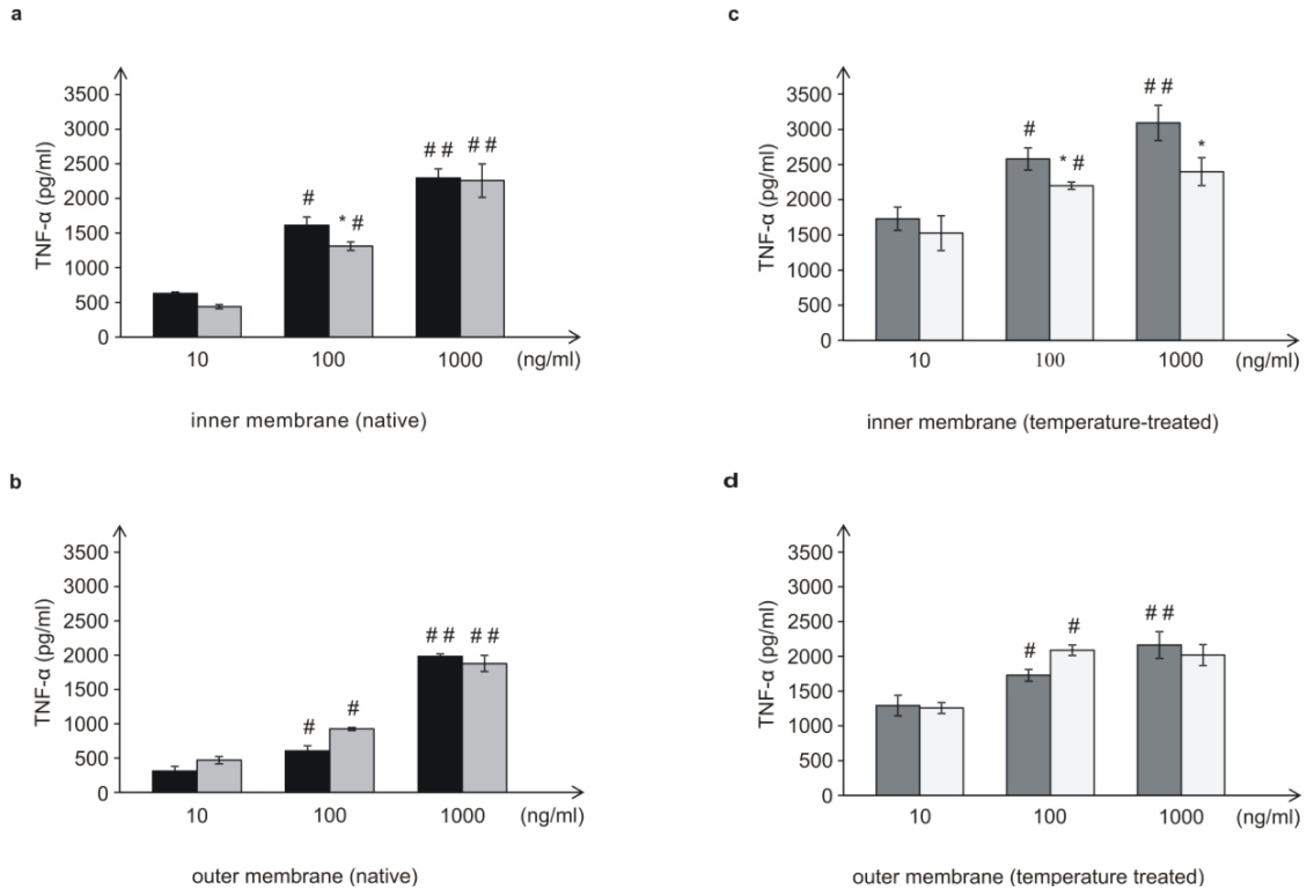

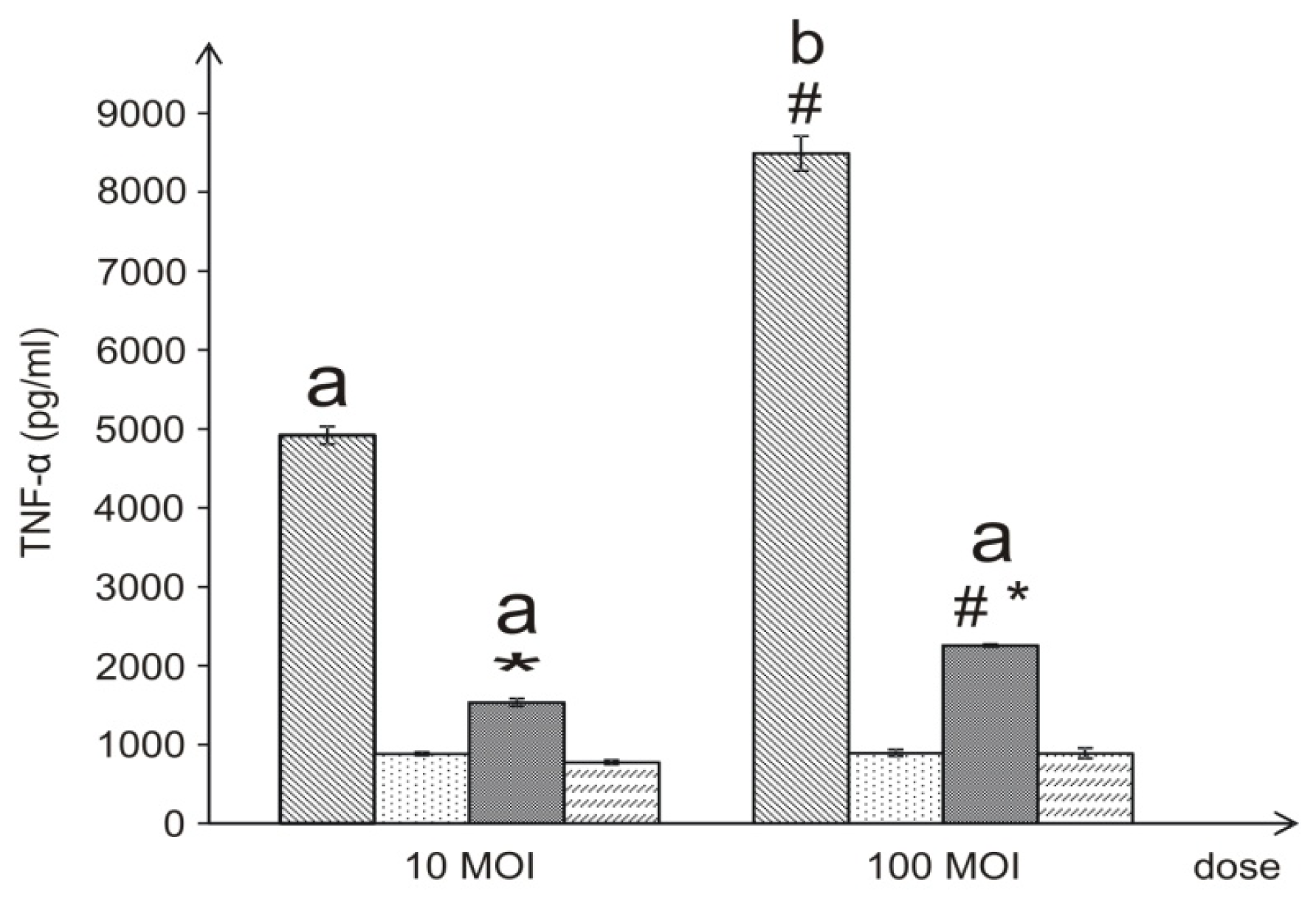

Several lines of evidence indicate that PC is able to modulate the inflammatory functions of monocytic cells. Tonks

et al. showed that PC 16:0/16:0 significantly inhibited TNF-α release from the human monocytic cell line MonoMac-6 in a dose-dependent manner. In contrast, PC 20:4/16:0 did not reduce TNF-α, which indicated that regulation of the inflammatory response was associated with the composition of fatty acids forming PC [

37]. In our study, live

L. dumoffii bacteria cultured on the choline-supplemented medium, induced three times less TNF-α than the cells grown on the non-supplemented medium. Similarly, the inner (temperature-treated and -untreated) membranes isolated from bacteria cultured on choline, applied at almost all the doses, induced a decreased level of TNF-α, in comparison to bacteria cultured without choline. Bacteria grown on choline incorporate into their inner membranes PC species with longer fatty acids than bacteria cultured without choline, which may have a significant effect on the lower induction of TNF-α level. In comparison to live bacteria, temperature-treated bacteria induced significantly lower TNF-α level. It is connected with the fact, that in live Legionella HSP, flagellin, and LPS are the main inducer of TNF-α. Temperature heating (90 °C, 20 min) causes HSP and flagellin degradation, therefore still present LPS is only inducer of this cytokine. This may be similar to the case of

L. pneumophila LPS [

38], although it is not known what the efficiency of

L. dumoffii LPS in the induction of TNF-α is, since no such investigations have been carried out and the structure of

L. dumoffii LPS is not known.

In the case of the 10- and 100-ng/mL concentrations of the outer membrane of live bacteria cultured on choline, TNF-α induction was higher than in the case of bacteria without choline; however, these differences were not statistically significant. It has been shown that lipopolysaccharide (LPS) of Gram-negative bacteria, a well-known TNF-α inducer located in the outer membrane, had an influence on the level of the cytokine as well. However,

L. pneumophila LPS is about 1000 times less potent in its ability to induce pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8) in Mono Mac 6 cells than the LPS of the

Enterobacteriaceae members [

21]. Cao

et al. showed that addition of PC18:2/18:2 into the culture of Kupffer cells significantly reduced LPS-stimulated TNF-α generation [

39]. We did not observe such an effect. Probably, the PC structure has a significant impact on the level of induction of this cytokine.

4. Experimental Section

4.1. Bacterial Strain and Growth Conditions

L. dumoffii strain ATCC 33279,

L. pneumophila serotype 3 ATCC 33155 were cultured on buffered charcoal-yeast extract (BCYE) agar plates, which contained a

Legionella CYE agar base (Oxoid, Basingstoke, Hampshire, UK) supplemented with the Growth Supplement SR0110A (ACES buffer/potassium hydroxide, ferric pyrophosphate,

l-cysteine HCl, α-ketoglutarate; Oxoid, Basingstoke, Hampshire, UK) for three days at 37 °C in a humid atmosphere and 5% CO

2 [

40].

L. dumoffii were also cultivated on this medium enriched with 100 μg·mL

−1 of choline-trimethyl-d

9 chloride (Sigma-Aldrich, Steinheim, Germany). The bacteria collected from this medium were washed three times with water by intensive vortexing and centrifugation at 8000×

g for 10 min. Bacteria cultured with and without choline were killed by 90 °C for 20 min. The efficiency of temperature inactivation of bacteria was checked by streaking the bacteria on BCYE plates.

Escherichia coli DH5α strain was grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium at 37 °C [

41].

4.2. Fractionation of L. dumoffii Cultured on BCYE Medium with and without Choline

The bacteria were collected from 12 BCYE plates supplemented with labeled choline and 12 non-supplemented BCYE plates. They were washed twice in saline in order to remove the remaining medium. Cell membrane isolation was performed essentially as described by Hindahl and Iglewski [

35].

The cells were washed twice with cold 10 mM HEPES (N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine- N-2-ethanesulfonic acid; Sigma-Aldrich, Steinheim, Germany) buffer (pH 7.4) and centrifuged at 8000× g, 15 min in 4 °C. The cell pellets were suspended in 15 mL of 10 mM HEPES buffer containing 20% sucrose (w/v) and incubated with DNase (0.3 mg) (Sigma-Aldrich, Steinheim, Germany) and RNase (0.3 mg) (Sigma-Aldrich, Steinheim, Germany) at 37 °C for 30 min 0.8-mL suspensions were lysed by three passages through a French press (SLM-Amico Instruments, Thermo Spectronic, Rochester, NY, USA) at 18000 lb/in2. After centrifugation for 20 min at 1000× g, 4 °C performed to remove cell debris and undisrupted cells, total membrane fractions were collected by centrifugation for 60 min at 100,000× g, 4 °C (SW 32Ti rotor, Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA). Next, they were washed twice in cold 10 mM HEPES buffer by centrifugation at 100,000× g for 1 h, 4 °C, the pelleted membranes were suspended in 2.5 mL of 10 mM HEPES buffer and layered onto a seven-step sucrose gradient.

4.3. Isolation of the Outer and Inner Membranes

Two milliliters of each cell membrane suspension were loaded on the top of a discontinuous gradient prepared by combining sucrose solutions of the following concentrations: 6 mL 70%, 9 mL 64%, 8 mL 58%, 5 mL 52%, 4 mL 48%, 3mL 42%, 3 mL 36% (w/v) in 10 mM HEPES buffer, pH 7.5. The gradient was centrifuged at 114,000× g, 20 h, 4 °C (SW 32Ti rotor, Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA), and 1 mL fractions were subsequently collected from the top of the centrifugation tube. The protein content was determined in the individual fractions and the fractions from the upper band of the gradient and the lower band of the gradient were collected separately. Next, the upper and lower fractions pooled separately were suspended in 10 mM HEPES buffer and centrifuged at 54,000× g for 1 h (MLA 80, Optima MAX-XP, Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA). The membrane pellets were washed three times in cold deionized water and centrifuged at 54,000× g for 1 h (MLA 80, Optima MAX-XP, Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA). Next, they were diluted in 250 μL of water (MQ, Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) for further analyses, i.e., enzyme assays and lipid isolation.

The efficacy of the membrane isolation procedure was confirmed by measuring the activity of NADH oxidase [

42] and esterase. The concentration of protein in the fractions was determined using the Bradford method and bovine serum albumin as a standard [

43].

4.4. Enzyme Assays

As marker enzymes for the inner and outer membrane, activities of NADH oxidase and esterase, respectively, were determined by spectrophotometric analysis of the absorbance decrease at 340 nm for NADH oxidase and the absorbance increase at 405 nm for esterase. For NADH oxidase, 62 μL of the reaction mixture (50 mM Tris/HCl, pH 7.5, 0.2 mM DTT, 0.12 mM NADH) (Sigma-Aldrich, Steinheim, Germany) was incubated for 15 min at 37 °C with 8 μL of each fraction in a microtitre plate. For esterase activity, 63 mg of p-nitrophenyl acetate (Sigma-Aldrich, Steinheim, Germany) was dissolved in 10 mL of ethanol. One milliliter of this solution was slowly added to 100 mL of distilled water. Ten microliters of each fraction were added to 90 μL of the substrate solution, incubated for 10 min at 25 °C, and absorbance at 405 nm was recorded. Fractions with the NADH oxidase and esterase activities representing the inner and outer membrane fractions were lyophilized and weighed.

4.5. Isolation of Lipids

Lipids were isolated from bacterial cells cultivated on BCYE medium enriched with labeled choline using the Bligh and Dyer (1959) method: chloroform/methanol (1:2

v/

v) [

44]. Lipids were analyzed with MALDI/TOF mass spectrometry.

Lipids from the inner and outer membranes prepared from bacteria grown on the choline-supplemented and non-supplemented medium were extracted using the same extraction method. The dried organic phase was then purified with a mixture of hexane/isopropanol (3:2, v/v). The extracts were dried under nitrogen before weighing and then dissolved in chloroform for further LC/ESI-MS analysis.

4.6. Matrix-Assisted Laser-Desorption/Ionization (MALDI)-Time of Flight (TOF) Mass Spectrometry

MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry analysis was performed on a Voyager-Elite instrument (PE Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) using delayed extraction in the reflectron mode. The dry lipid extract was dissolved in a CHCl3/CH3OH mixture (2:1, v/v). The sample constituents mixed with 0.5 M aniline salt of α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid (CHCA) as a matrix were desorbed and ionized with a nitrogen laser at an extraction voltage of 20 kV. Angiotensin was used as an internal standard. Each spectrum was the average of about 256 laser shots.

4.7. Liquid Chromatography Coupled with the Mass Spectrometry Technique Using the Electrospray Ionization Technique (LC/ESI-MS)

The LC/ESI-MS analyses were performed on a Prominence LC-20 (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) liquid chromatograph coupled with a tandem mass spectrometer 4000 Q TRAP (Applied Biosystems Inc., Foster City, CA, USA), equipped with an electrospray (ESI) ion source (TurboIonSpray, Applied Biosystems Inc., Foster City, CA, USA) and a triple quadrupole/linear ion trap mass analyzer. The separation of the phospholipid mixture was carried out by normal phase chromatography using a 4.6 × 150 mm Zorbax SIL RX column (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA). Hexane/isopropanol (3:2, v/v) was used as solvent A and an isopropanol/hexane/5 mM aqua solution of ammonium acetate (38:56:5, v/v/v) as solvent B. The following elution program was employed: from 53% B to 80% B for 23 min, 80% B maintained for 4 min, 80% B to 100% B for 9 min and 100% B maintained for 14 min. The flow rate was 1 mL/min. The lipid extracts were dissolved in phase A.

To identify PC species, the precursor ion mode (PI) and neutral loss scan (NL) mass spectrometry techniques were employed in the positive ion mode. The measurements were performed using an electrospray ion source (ESI) with the following parameters: ion spray voltage (IS)—5500 V, declustering potential (DP)—40 V, and entrance potential (EP)—10 V. Nitrogen was used as a curtain (CUR 20 psi), a nebulizer (GS1 50 psi), and a collision gas. The source temperature was set at 250 °C. The collision-induced dissociation (CID) spectra were obtained in the positive and the negative ion mode using collision energy of 50 eV.

The Multiple Reaction Monitoring (MRM) technique performed in the negative ion mode was employed to compare the PC amounts in the analyzed cell membranes. The most abundant PC molecular species at m/z 778.9 (16:0/15:0) and 764.9 (15:0/15:0) were chosen in this experiment. Based on the fragmentation spectra of the selected peaks in the negative ion mode, the following MRM pairs were used: 764.9/690.4, 764.9/241.2, and 778.9/704.4, 778.9/241.2.

Chemicals for the LC/MS system (hexane, isopropanol, acetonitrile LC grade) were obtained from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany), and ammonium acetate from Sigma-Aldrich Fluka (Steinheim, Germany).

4.8. DNA Methods, PCR Amplification, and Southern Hybridization

Restriction enzyme digestion, agarose gel electrophoresis, DNA labeling, and Southern hybridization were used for genomic DNA isolation [

41]. To amplify the DNA fragment containing

pcsA of

L. pneumophila serotype 3 (ATCC 33155), the PCR reaction was performed using 100 ng of genomic DNA, REDTaq ReadyMix (Sigma-Aldrich, Steinheim, Germany) and 0.2 μM of each forward (pcsF: 5′-CTCTAGGATCCGTAATGAATCCAATAAA-3′) and reverse (pcsR: 5′-CATAAATTGG ATCCAAACTCAATCTTTATTAT-3′) primers in a 50-μL final volume. The PCR reaction was performed with the following temperature profile: initial denaturation at 94 °C for 4 min, 30 cycles of denaturation 94 °C for 1 min, annealing at 48 °C for 40 s, extension at 72 °C for 60 s, and final extension at 72 °C for 4 min. This PCR fragment was labeled using the non-radioactive DIG DNA Labeling and Detection kit according to the manufacturer’s instruction (Roche Applied Science, Penzberg, Germany). The 800-bp-long DIG-labeled amplicon with the

pcsA gene was used as a probe in the Southern hybridization. Additionally, DIG-labeled DNA of phage λ digested with

EcoRI and

HindIII restriction enzymes were used as a molecular size marker. Genomic DNA from

L. pneumophila serotype 3,

L. dumoffii, and

E. coli DH5α (used as a negative control) were digested with

BamHI and

EcoRI enzymes, separated by 0.7% agarose gel electrophoresis, and blotted. In addition, λ DNA digested with both

EcoRI and

HindIII enzymes was used as molecular markers. The hybridization experiments were performed at reduced-stringency conditions at 37 °C using 20% formamide in pre-hybridization and hybridization solutions as described previously [

11].

To amplify and sequence the L. dumoffii pcsA gene, a set of degenerate primers has been designed based on the genomic sequences of L. pneumophila strain Philadelphia 1, L. longbeachae D-4968, and L. drancourtii LLAP12. Primers pcsLd-F (5′-ACTTTTKATWATYGATRMTATTTT-3′) and pcsLd-R (5′-TAATCATWAAADABYCAAAGTCTAT-3′) allowed amplification of the longest 900-bp fragment containing pcsA gene. The PCR reactions were performed with the temperature profile described above, except the annealing temperature that was decreased to 43 °C. The amplified DNA fragment was purified on the columns (A&A Biotechnology, Gdynia, Poland) and sequenced using the BigDye terminator cycle sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems, Inc., Foster City, CA, USA) and the ABI Prism 310 sequencer. Database searches were done with the BLAST and FASTA programs available at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (Bethesda, MD, USA) and the European Bioinformatics Institute (Hinxton, UK). The sequence of L. dumoffii pcsA obtained in this study has been deposited in NCBI GenBank under accession number KC197708. Promoter prediction in the upstream region of L. dumoffii pcsA was done using BDGP Neural Network Promoter Prediction (fruitfly.org).

4.9. THP-1 Cell Culture

The human acute monocytic leukemia cell line (THP-1) was obtained from the European Collection of Cell Cultures (Cat No. 88081201). Cells were cultured at (0.5–7) × 105 cells/mL in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS), 10 mM HEPES, 2 mM glutamine, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin. The cells cultured in tissue culture flasks (Falcon, Bedford, MA, USA) were incubated at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. The culture media, antibiotics, and FCS were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Steinheim, Germany).

4.10. THP-1 Cell Differentiation

THP-1 were seeded onto 24-well plastic plates (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark) at a density of 5 × 105 cells/well in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FCS, and treated with a final concentration of 50 ng/mL phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) (Sigma-Aldrich, Steinheim, Germany) for three days to induce maturation toward adherent macrophage-like cells. Subsequently, unattached cells were removed and after three-time washing adherent THP-1 cells were cultured in medium without PMA for three consecutive days with daily fresh medium change.

4.11. THP-1 Cell Viability Assay

The viability of THP-1 cells exposed to L. dumoffii bacteria was determined by the MTT assay, in which the yellow tetrazolium salt 3-(4,5 dimethyl-2-thiazolyl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide (MTT) is metabolized by viable cells to purple formazan crystals. The cells at a density of 5 × 104 cells/well were seeded onto 96-well plates (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark) and cultured in 10% RPMI 1640 for 24 h. Next, the medium was replaced with a fresh one with addition of 2% FCS and different concentrations of L. dumoffii at a MOI of 10, 50, 100, and 200. The treated cells were maintained in a humidified CO2-incubator at 37 °C for 4 and 24 h. Subsequently, MTT solution (25 μL of 5 mg/mL in PBS) (Sigma-Aldrich, Steinheim, Germany) was added to each well. The cells were incubated at 37 °C for 3 h, and 100 μL of SDS in 0.01 M HCl was added to dissolve the formazan crystals during overnight incubation. The controls included native (non-treated) cells and the medium alone. The spectrophotometric absorbance was measured at 570 nm wavelength using a VICTOR X4 Multilabel Plate Reader (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA, USA). The data are presented as percentage of control cell viability.

4.12. In Vitro Infection of Differentiated THP-1 with L. dumoffii—Control of Internalization and Intracellular Growth

Differentiated THP-1 cells (as described in 4.10.) were infected with 10 MOI of live L. dumoffii cultured on choline-supplemented and non-supplemented medium. After incubation for 2 h at 37 °C, 5% CO2, nonphagocytized bacteria were killed by the addition of 100 mg of gentamicin/mL for 1 h. Next, supernatants were removed and the macrophages were washed three-times with PBS. 1 mL of sterile distilled water (for bacterial internalization study) or 1 mL of RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FCS (without antibiotics) was added and the macrophages were incubated for 24, 48, and 72 h (intracellular bacterial growth study).

4.12.1. Bacteria Internalization Assay

Cells suspended in 1 mL of sterile distilled water were disrupted by aspiration through a 25-gauge needle and then series of 10-fold dilutions were made. Subsequently, 0.1 mL of each dilution was inoculated onto BCYE agar and colonies of culturable L. dumoffii were counted after three days of incubation at 37 °C, 5% CO2.

4.12.2. Intracellular Bacteria Growth Assay

After 24, 48, and 72 h of cell culture incubation, supernatants were collected into sterile tubes, centrifuged (8000 rpm/min for 10 min), and washed with sterile distilled water. One milliliter of sterile distilled water was added to THP-1 cells, which were disrupted as described above and pooled with centrifuged pellet of the respective supernatant. 0.1 mL of series of 10-fold dilutions of each sample were inoculated onto BCYE agar and incubated as above.

Formation of colonies was determined in triplicate for at least two independent experiments.

4.13. Induction of TNF-α with L. dumoffii in THP-1 Cells

The differentiated macrophages were treated with live or dead L. dumoffii for 4 h at a MOI = 10 or 100. In another experiment, the macrophages were treated with different concentrations (10–1000 ng/mL) of L. dumoffii outer or inner membranes non-treated and treated with temperature (90 °C, 20 min).

Additional controls were performed: non-treated macrophages, non-activated THP-1 cells.

In all experiments, the bacteria had been previously cultured on medium with or without addition of choline (choline-trimethyl-d9 chloride, Sigma-Aldrich, Steinheim, Germany). After incubation for 4 h at 37 °C, 5% CO2, cell culture supernatants were collected and frozen immediately at −80 °C for further TNF-α determination. TNF-α level was measured by the ELISA method using a commercial kit from R&D Systems according to the manufacturer’s instructions (R&D Systems Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA). All experiments were conducted in five independent replicates.

4.14. Statistics

Values are expressed as mean ± S.D. Results were statistically evaluated using two-way ANOVA and Tukey’s post hoc tests (Statistica software ver. 6.0, StatSoft Inc., Tulsa, OK, USA, 2001). p values of ≤0.05 were considered significant.

—live L. dumoffii;

—live L. dumoffii;  —temperature-treated L. dumoffii;

—temperature-treated L. dumoffii;  —live L. dumoffii cultured on choline-supplemented medium;

—live L. dumoffii cultured on choline-supplemented medium;

—temperature-treated L. dumoffii cultured on choline-supplemented medium.

—temperature-treated L. dumoffii cultured on choline-supplemented medium.

—live L. dumoffii;

—live L. dumoffii;  —temperature-treated L. dumoffii;

—temperature-treated L. dumoffii;  —live L. dumoffii cultured on choline-supplemented medium;

—live L. dumoffii cultured on choline-supplemented medium;

—temperature-treated L. dumoffii cultured on choline-supplemented medium.

—temperature-treated L. dumoffii cultured on choline-supplemented medium.

—membrane from bacteria cultured on the choline non-supplemented medium.

—membrane from bacteria cultured on the choline non-supplemented medium.

—membrane from bacteria cultured on the choline-supplemented medium.

—membrane from bacteria cultured on the choline-supplemented medium.

—temperature-treated membrane from bacteria cultured on the choline non-supplemented medium.

—temperature-treated membrane from bacteria cultured on the choline non-supplemented medium.

—temperature-treated membrane from bacteria cultured on the choline-supplemented medium.

—temperature-treated membrane from bacteria cultured on the choline-supplemented medium.

—membrane from bacteria cultured on the choline non-supplemented medium.

—membrane from bacteria cultured on the choline non-supplemented medium.

—membrane from bacteria cultured on the choline-supplemented medium.

—membrane from bacteria cultured on the choline-supplemented medium.

—temperature-treated membrane from bacteria cultured on the choline non-supplemented medium.

—temperature-treated membrane from bacteria cultured on the choline non-supplemented medium.

—temperature-treated membrane from bacteria cultured on the choline-supplemented medium.

—temperature-treated membrane from bacteria cultured on the choline-supplemented medium.