Chemical and Enantioselective Analysis of the Leaf Essential Oil from Varronia crenata Ruiz & Pav. Growing in Ecuador

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

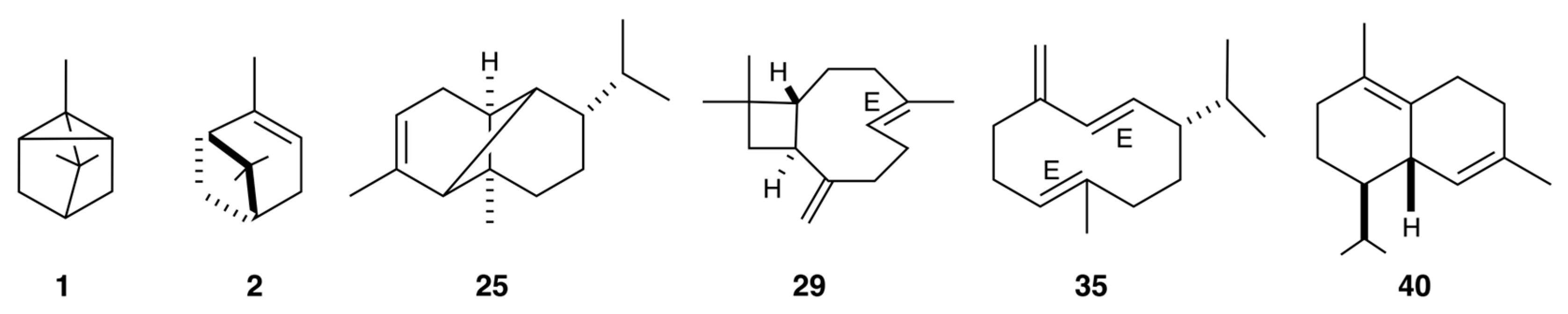

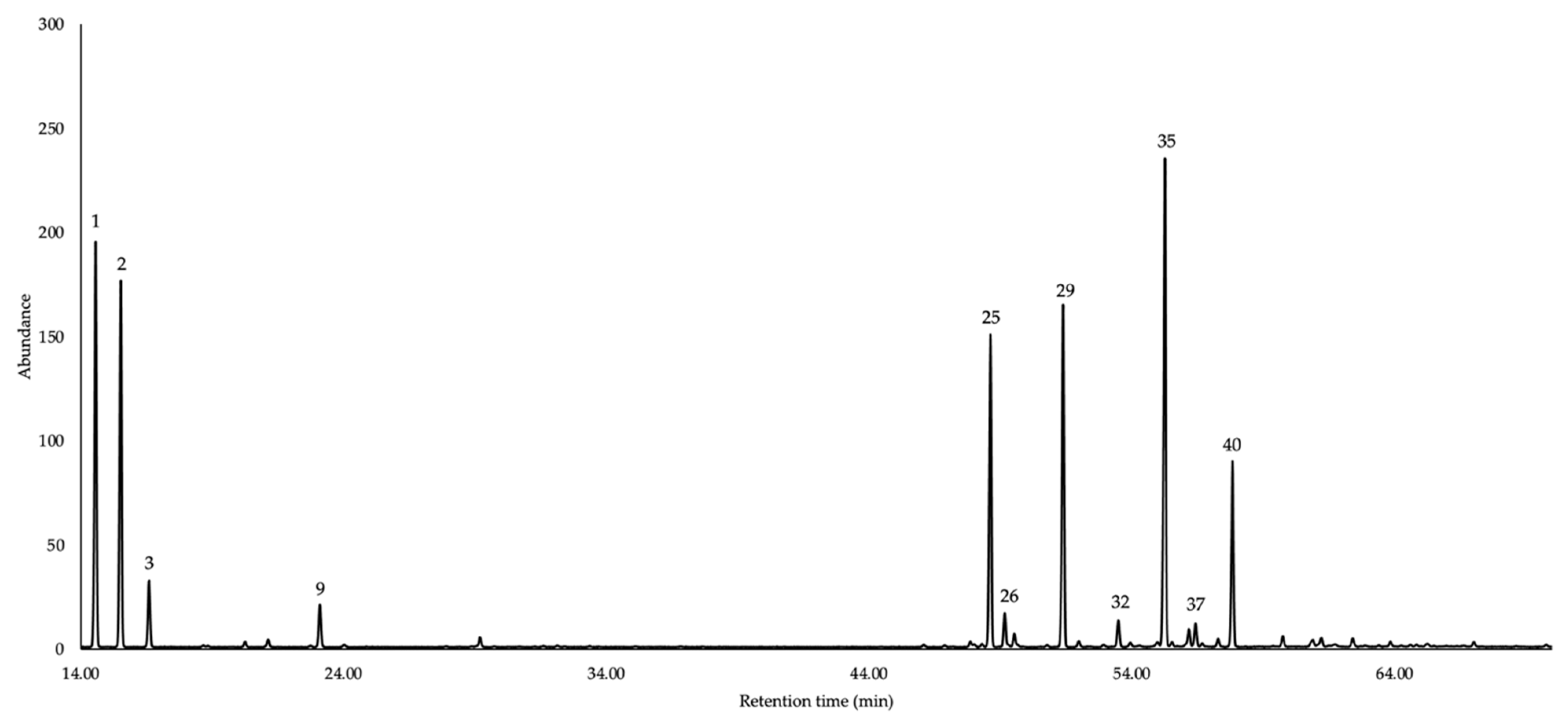

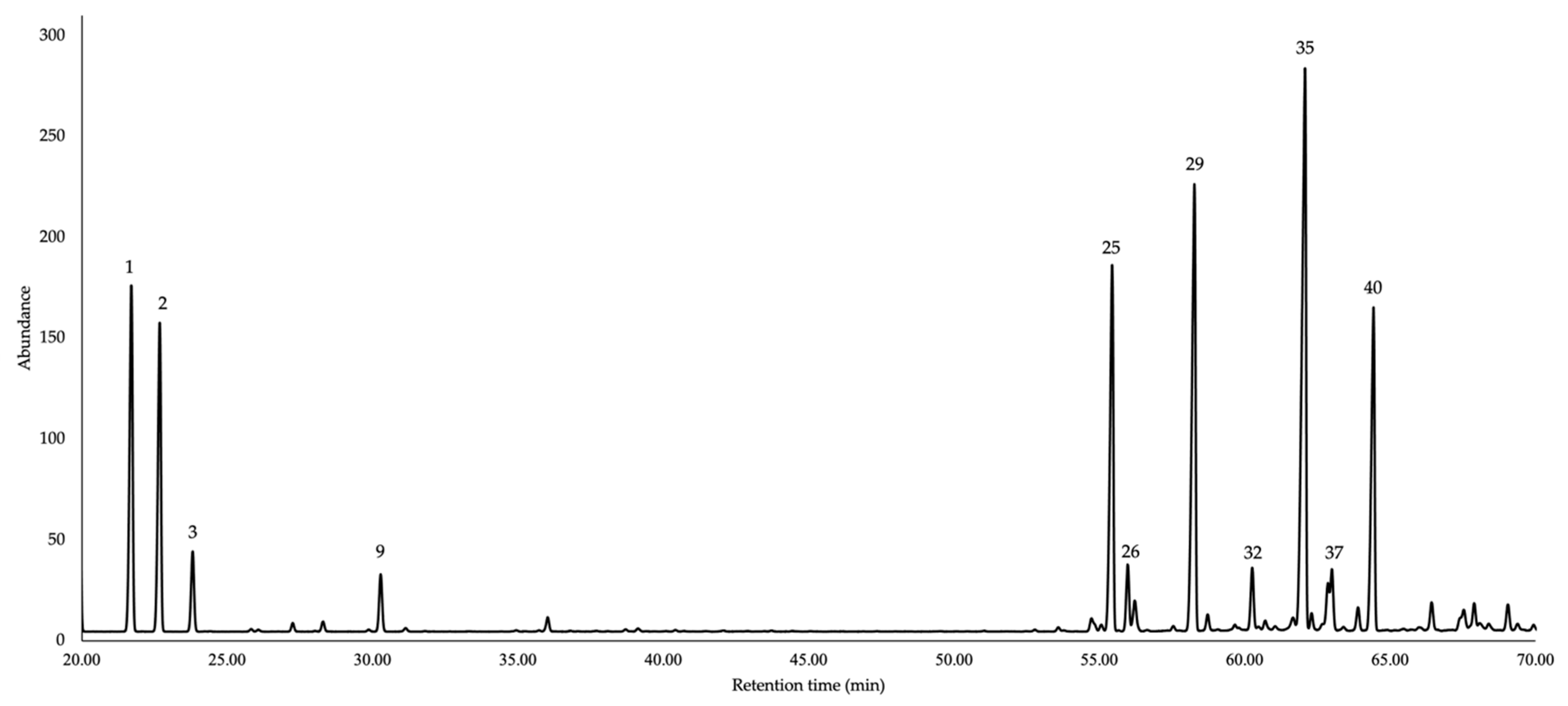

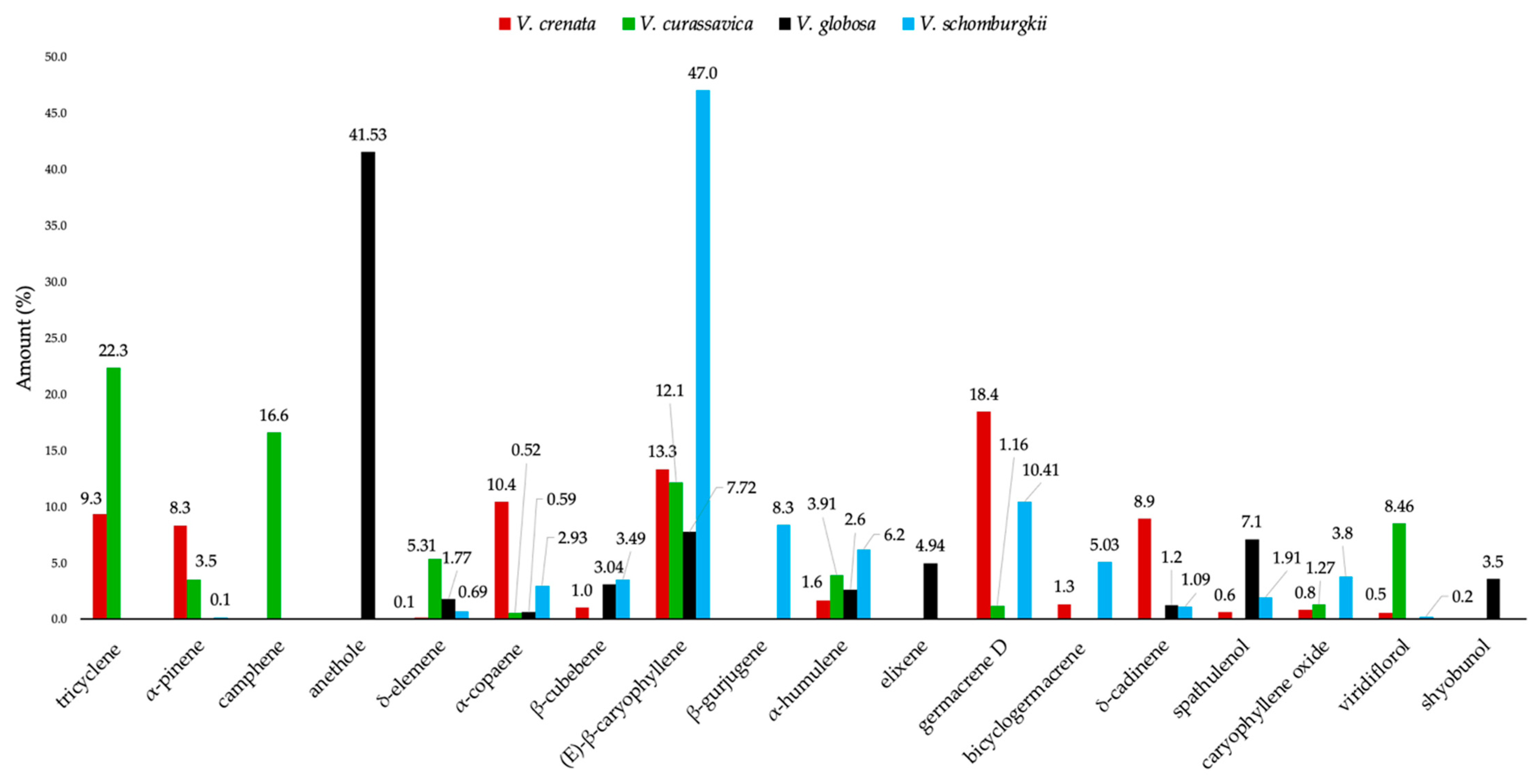

2.1. Chemical Composition of the EO

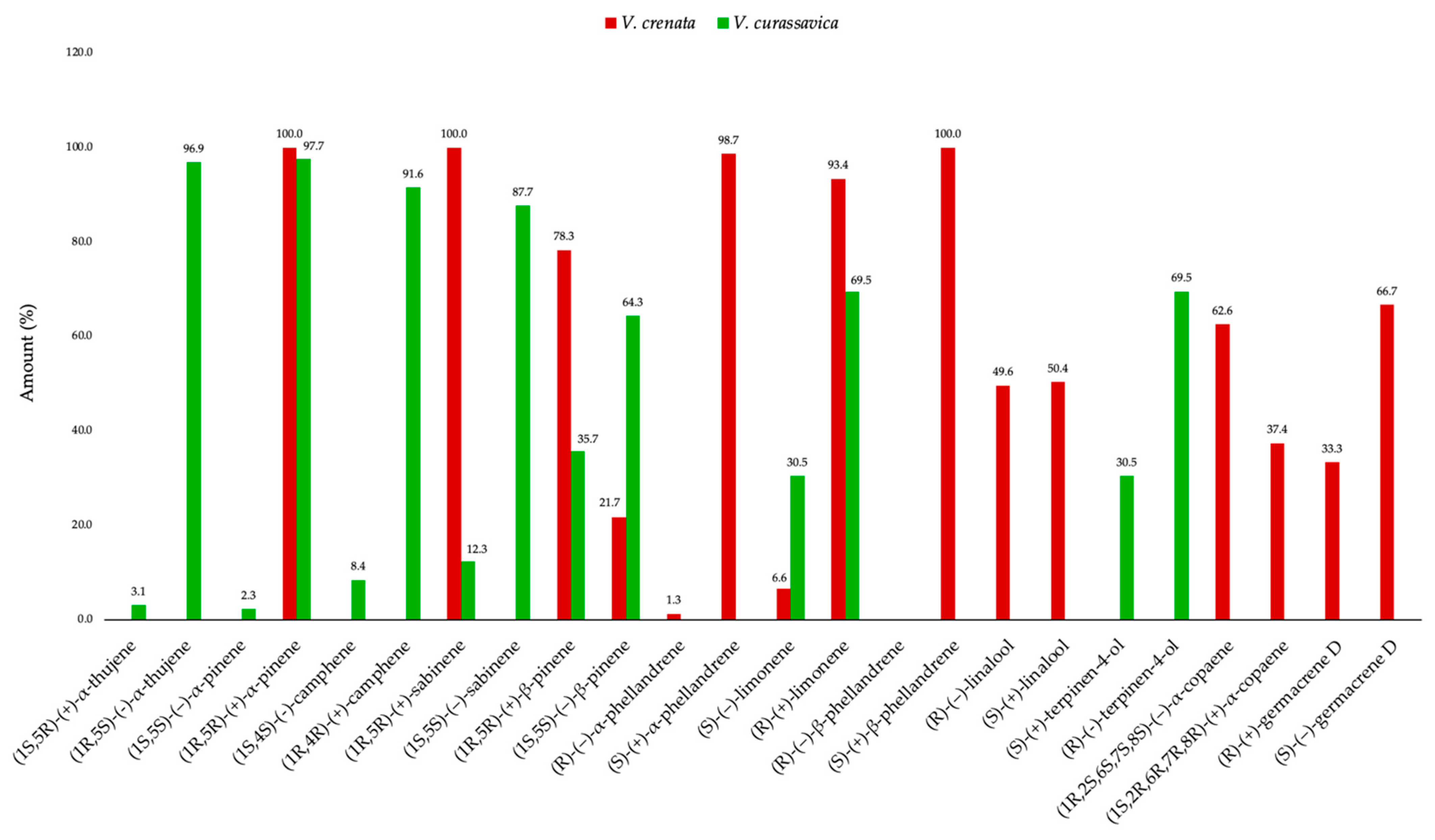

2.2. Enantioselective Analysis

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Material

4.2. Distillation and Sample Preparation

4.3. Qualitative (GC-MS) Chemical Analyses

4.4. Quantitative (GC-FID) Chemical Analyses

4.5. Enantioselective Analyses

4.6. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abdelmohsen, U.; Elmaidomy, A. Exploring the therapeutic potential of essential oils: A review of composition and influencing factors. Front. Nat. Prod. 2025, 4, 1490511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakkali, F.; Averbeck, S.; Averbeck, D.; Idaomar, M. Biological effects of essential oils—A review. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2008, 46, 446–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sousa, D.P.; Damasceno, R.O.S.; Amorati, R.; Elshabrawy, H.A.; de Castro, R.D.; Bezerra, D.P.; Nunes, V.R.V.; Gomes, R.C.; Lima, T.C. Essential Oils: Chemistry and Pharmacological Activities. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNEP-WCMC Megadiverse Countries. Available online: https://www.biodiversitya-z.org/content/megadiverse-countries (accessed on 28 April 2025).

- Malagón, O.; Ramírez, J.; Andrade, J.; Morocho, V.; Armijos, C.; Gilardoni, G. Phytochemistry and Ethnopharmacology of the Ecuadorian Flora. A Review. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2016, 11, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armijos, C.; Ramírez, J.; Salinas, M.; Vidari, G.; Suárez, A.I. Pharmacology and Phytochemistry of Ecuadorian Medicinal Plants: An Update and Perspectives. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrzanowska, E.; Denisow, B.; Ekiert, H.; Pietrzyk, Ł. Metabolites Obtained from Boraginaceae Plants as Potential Cosmetic Ingredients—A Review. Molecules 2024, 29, 5088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemayehu, G.; Asfaw, Z.; Kelbessa, E. Cordia africana (Boraginaceae) in Ethiopia: A Review on Its Taxonomy, Distribution, Ethnobotany and Conservation Status. Int. J. Bot. Stud. 2016, 1, 38–46. [Google Scholar]

- Oza, M.J.; Kulkarni, Y.A. Plants from Cordia genus: A review on their phytochemistry, ethnopharmacology and pharmacological activities. Pharmacogn. J. 2017, 9, 857–871. [Google Scholar]

- Begum, N.; Lee, H.-Y. Varronia spinescens—An Extensive Overview of Floral Strategies, Bioactive Compounds and Medicinal Uses. J. Biotechnol. Bioind. 2023, 11, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.S. New Boraginales from tropical America 8: Nomenclatural notes on Varronia (Cordiaceae: Boraginales). Brittonia 2013, 65, 342–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.S. New Boraginales from tropical America 7: A new species of Cordia from Bolivia and nomenclatural notes on neotropical Cordiaceae. Brittonia 2012, 64, 359–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tropicos.org. Missouri Botanical Garden. Available online: https://www.tropicos.org (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- POWO. Plants of the World Online: [Cordia alliodora]. Facilitated by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Published on the Internet. 2026. Available online: https://powo.science.kew.org/results?q=cordia%20alliodora (accessed on 21 January 2026).

- de la Torre, L.; Navarrete, H.; Muriel, M.P.; Macía, M.J.; Balslev, H. (Eds.) Enciclopedia de las Plantas Útiles del Ecuador; Herbario QCA de la Escuela de Ciencias Biológicas de la Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador: Quito, Ecuador; Herbario AAU del Departamento de Ciencias Biológicas de la Universidad de Aarhus: Aarhus, Denmark, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- WFO Plant List. World Flora Online. Available online: https://wfoplantlist.org/ (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Jorgensen, P.; León-Yanez, S. Catalogue of the Vascular Plants of Ecuador; Missouri Botanical Garden Press: St. Louis, MO, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- de Castro Nizio, D.A.; Fujimoto, R.Y.; Nizio Maria, A.; Carneiro, P.C.F.; França, C.C.S.; Sousa, N.C.; Brito, F.A.; Sampaio, T.S.; Arrigoni-Blank, M.F.; Blank, A.F. Essential oils of Varronia curassavica accessions have different activity against white spot disease in freshwater fish. Parasitol. Res. 2017, 116, 5673–5684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, A.P.S.; Bonfim, F.P.G.; Dantas, W.F.C.; Puppi, R.J.; Marques, M.O.M. Chemical composition of essential oil from Varronia curassavica Jacq. accessions in different seasons of the year. Ind. Crops Prod. 2019, 140, 111656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, F.P.; Venzon, M.; Dôres, R.G.R.; Franzin, M.L.; Martins, E.F.; Araújo, G.J.; Fonseca, M.C.M. Toxicity of Varronia curassavica Jacq. essential oil to two arthropod pests and their natural enemy. Neotrop. Entomol. 2021, 50, 835–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.T.C.; Silva, V.B.; Silva, S.B.; Rocha, M.I.; Costa, A.R.; Silva, J.R.L.; Santos, M.A.F.; Generino, M.E.M.; Souza, J.H.; Oliveira, M.G.; et al. Chemical characterization and biological activity of Varronia curassavica Jacq. essential oil (Boraginaceae) and in silico testing of α-pinene. Analytica 2024, 5, 499–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuroyanagi, M.; Kawahara, N.; Sekita, S.; Satake, M.; Hayashi, T.; Takase, Y.; Masuda, K. Dammarane-type triterpenes from the Brazilian medicinal plant Cordia multispicata. J. Nat. Prod. 2003, 66, 1307–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopes, K.; Oliveira, J.; Sousa-Junior, F.J.C.; Santos, T.F.; Andrade, D.; Andrade, S.L.; Pereira, W.L.; Gomes, P.W.P.; Monteiro, M.C.; e Silva, C.Y.Y.; et al. Chemical composition, toxicity, antinociceptive, and anti-inflammatory activity of dry aqueous extract of Varronia multispicata (Cham.) Borhidi (Cordiaceae) leaves. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badji, C.A.; Dorland, J.; Kheloul, L.; Bréard, D.; Richomme, P.; Kellouche, A.; Azevedo de Souza, C.R.; Bezerra, A.L.; Anton, S. Behavioral and antennal responses of Tribolium confusum to Varronia globosa essential oil and its main constituents: Perspective for their use as repellent. Molecules 2021, 26, 4393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Carvalho, P.M.; Rodrigues, R.F.O.; Sawaya, A.C.H.F.; Marques, M.O.M.; Shimizu, M.T. Chemical composition and antimicrobial activity of the essential oil of Cordia verbenacea D.C. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2004, 95, 297–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sertié, J.A.A.; Woisky, R.G.; Wiezel, G.; Rodrigues, M. Pharmacological assay of Cordia verbenacea: Oral and topical anti-inflammatory activity, analgesic effect and fetus toxicity of a crude leaf extract. Phytomedicine 2005, 12, 338–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passos, G.F.; Fernandes, E.S.; Da Cunha, F.M.F.; Ferreira, J.; Pianowski, L.F.; Campos, M.M.; Calixto, C.J.B. Anti-inflammatory and anti-allergic properties of the essential oil and active compounds from Cordia verbenacea. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2007, 110, 323–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ticli, F.K.; Hage, L.I.; Cambraia, R.S.; Pereira, O.S.; Magro, A.J.; Fontes, M.R.; Stabeli, R.G.; Giglio, J.R.; Franca, S.C.; Soares, A.M.; et al. Rosmarinic acid, a new snake venom phospholipase A2 inhibitor from Cordia verbenacea (Boraginaceae): Antiserum action. Toxicon 2005, 46, 318–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Oliveira, B.M.S.; Melo, C.R.; Santos, A.C.C.; Nascimento, L.F.A.; Nízio, D.A.C.; Cristaldo, P.F.; Blank, A.F.; Bacci, L. Essential oils from Varronia curassavica (Cordiaceae) accessions and their compounds (E)-caryophyllene and α-humulene as an alternative to control Dorymyrmex thoracius (Formicidae: Dolichoderinae). Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 4044–4060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, R.P. Identification of Essential Oil Components by Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry, 4th ed.; Allured Publishing Corporation: Carol Stream, IL, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bertoli, A.; Menichini, F.; Noccioli, C.; Morelli, I.; Pistelli, L. Volatile constituents of different organs of Psoralea bituminosa L. Flavour Fragr. J. 2004, 19, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rega, B.; Fournier, N.; Nicklaus, S.; Guichard, E. Role of pulp in flavor release and sensory perception in orange juice. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004, 52, 4204–4212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelwahed, A.; Hayder, N.; Kilani, S.; Mahmoud, A.; Chibani, J.; Hammami, M.; Chekir-Ghedira, L.; Ghedira, K. Chemical composition and antimicrobial activity of essential oils from Tunisian Pituranthos tortuosus (Coss.) Maire. Flavour Fragr. J. 2006, 21, 129–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brat, P.; Rega, B.; Alter, P.; Reynes, M.; Brillouet, J.-M. Distribution of volatile compounds in the pulp, cloud, and serum of freshly squeezed orange juice. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 3442–3447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kundakovic, T.; Fokialakis, N.; Kovacevic, N.; Chinou, I. Essential oil composition of Achillea lingulata and A. umbellata. Flavour Fragr. J. 2007, 22, 184–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saroglou, V.; Arfan, M.; Shabir, A.; Hadjipavlou-Litina, D.; Skaltsa, H. Composition and antioxidant activity of the essential oil of Teucrium royleanum Wall. ex Benth growing in Pakistan. Flavour Fragr. J. 2007, 22, 154–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saroglou, V.; Marin, P.D.; Rancic, A.; Veljic, M.; Skaltsa, H. Composition and antimicrobial activity of the essential oil of six Hypericum species from Serbia. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2007, 35, 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, W.H.; Baek, H.H. Identification of characteristic aroma-active compounds from water dropword (Oenanthe javanica DC.). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 6766–6770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.H.; Thuy, N.T.; Shin, J.H.; Baek, H.H.; Lee, H.J. Aroma-active compounds of miniature beefsteakplant (Mosla dianthera Maxim.). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2000, 48, 2877–2881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flamini, G.; Cioni, P.L.; Morelli, I.; Maccioni, S.; Baldini, R. Phytochemical typologies in some populations of Myrtus communis L. on Caprione Promontory (East Liguria, Italy). Food Chem. 2004, 85, 599–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, I.H.; Choi, H.-K.; Kim, Y.-S. Difference in the volatile composition of pine-mushrooms (Tricholoma matsutake Sing.) according to their grades. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 4820–4825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bisio, A.; Ciarallo, G.; Romussi, G.; Fontana, N.; Mascolo, N.; Capasso, R.; Biscardi, D. Chemical Composition of Essential Oils from some Salvia species. Phytother. Res. 1998, 12, s117–s120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, G.S.; Larsen, L.M.; Poll, L. Formation of volatile compounds in model experiments with crude leek (Allium ampeloprasum Var. Lancelot) enzyme extract and linoleic acid or linolenic acid. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004, 52, 2315–2321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsieh, T.C.Y.; Williams, S.S.; Vejaphan, W.; Meyers, S.P. Characterization of Volatile Components of Menhaden Fish (Brevoortia tyrannus) Oil. J. Amer. Oil Chem. Soc. 1989, 66, 114–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salgueiro, L.R.; Pinto, E.; Goncalves, M.J.; Costa, I.; Palmeira, A.; Cavaleiro, C.; Pina-Vaz, C.; Rodrigues, A.G.; Martinez-De-Oliveira, J. Antifungal activity of the essential oil of Thymus capitellatus against Candida, Aspergillus and dermatophyte strains. Flavour Fragr. J. 2006, 21, 749–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, M.A.C.K.; Joseph, H.; Bercion, S.; Menut, C. Chemical composition of essential oils from aerial parts of Aframomum exscapum (Sims) Hepper collected in Guadeloupe, French West Indies. Flavour Fragr. J. 2006, 21, 902–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanciullino, A.-L.; Gancel, A.-L.; Froelicher, Y.; Luro, F.; Ollitrault, P.; Brillouet, J.-M. Effects of Nucleo-cytoplasmic Interactions on Leaf Volatile Compounds from Citrus Somatic Diploid Hybrids. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 4517–4523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mondello, L.; Zappia, G.; Cotroneo, A.; Bonaccorsi, I.; Chowdhury, J.U.; Yusuf, M.; Dugo, G. Studies on the essential oil-bearing plants of Bangladesh. Part VIII. Composition of some Ocimum oils O. basilicum L. var. purpurascens; O. sanctum L. green; O. sanctum L. purple; O. americanum L., citral type; O. americanum L., camphor type. Flavour Fragr. J. 2002, 17, 335–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gancel, A.-L.; Ollitrault, P.; Froelicher, Y.; Tomi, F.; Jacquemond, C.; Luro, F.; Brillouet, J.-M. Leaf volatile compounds of six citrus somatic allotetraploid hybrids originating from various combinations of lime, lemon, citron, sweet orange, and grapefruit. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 2224–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hachicha, S.F.; Skanji, T.; Barrek, S.; Ghrabi, Z.G.; Zarrouk, H. Composition of the essential oil of Teucrium ramosissimum Desf. (Lamiaceae) from Tunisia. Flavour Fragr. J. 2007, 22, 101–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalli, J.-F.; Tomi, F.; Bernardini, A.-F.; Casanova, J. Chemical variability of the essential oil of Helichrysum faradifani Sc. Ell. from Madagascar. Flavour Fragr. J. 2006, 21, 111–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sylvestre, M.; Longtin, A.P.A.; Legault, J. Volatile leaf condtituents and anticancer activity of Bursera simaruba (L.) Sarg. essential oil. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2007, 2, 1273–1276. [Google Scholar]

- Gauvin, A.; Smadja, J. Essential oil composition of four Psiadia species from Reunion Island: A chemotaxonomic study. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2005, 33, 705–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ollé, D.; Baumes, R.L.; Bayonove, C.L.; Lozano, Y.F.; Sznaper, C.; Brillouet, J.-M. Comparison of free and glycosidically linked volatile components from polyembryonic and monoembryonic mango (Mangifera indica L.) cultivars. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1998, 46, 1094–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, A.; Rosa, S.; Goncalves, J.; Rufino, A.; Judas, F.; Salgueiro, L.; Lopes, M.C.; Cavaleiro, C.; Mendes, A.F. Screening of five essential oils for identification of potential inhibitors of IL-1-unduced Nf-kB activation and NO production in human clondrocytes: Characterization of the inhibitory activity of alpha-pinene. Plante Med. 2010, 76, 303–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limberger, R.P.; Scopel, M.; Sobral, M.; Henriques, A.T. Comparative analysis of volatiles from Drimys brasiliensis Miers and D. angustifolia Miers (Winteraceae) from Southern Brazil. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2007, 35, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bader, A.; Caponi, C.; Cioni, P.L.; Flamini, G.; Morelli, I. Composition of the essential oil of Ballota undulata, B. nigra ssp. foetida and B. saxatilis. Flavour Fragr. J. 2003, 18, 502–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez Arze, J.B.; Collin, G.; Garneau, F.-X.; Jean, F.-I.; Gagnon, H. Essential oils from Bolivia. II. Asteraceae: Ophryosporus heptanthus (Wedd.) H. Rob. et King. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2004, 16, 374–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flamini, G.; Tebano, M.; Cioni, P.L.; Bagci, Y.; Dural, H.; Ertugrul, K.; Uysal, T.; Savran, A. A multivariate statistical approach to Centaurea classification using essential oil composition data of some species from Turkey. Plant Syst. Evol. 2006, 261, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Quere, J.-L.; Latrasse, A. Composition of the Essential Oils of Blackcurrant Buds (Ribes nigrum L.). J. Agric. Food Chem. 1990, 38, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capetanos, C.; Saroglou, V.; Marin, P.D.; Simic, A.; Skaltsa, H.D. Essential oil snalysis of two endemic Eringium species from Serbia. J. Serb. Chem. Soc. 2007, 72, 961–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bousaada, O.; Ammar, S.; Saidana, D.; Chriaa, J.; Chraif, I.; Daami, M.; Helal, A.N.; Mighri, Z. Chemical composition and antimicrobial activity of volatile components from capitula and aerial parts of Rhaponticum acaule DC growing wild in Tunisia. Microbiol. Res. 2008, 163, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, T.; Canales, M.; Teran, B.; Avila, O.; Duran, A.; Garcia, A.M.; Hernandez, H.; Angeles-Lopez, O.; Fernandez-Araiza, M.; Avila, G. Antimicrobial Activity of the Essential Oil and Extracts of Cordia curassavica (Boraginaceae). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2007, 111, 137–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mhamdi, B.; Wannes, W.A.; Dhiffi, W.; Marzouk, B. Volatiles from Leaves and Flowers of Borage (Borago officinalis L.). J. Essent. Oil Res. 2009, 21, 504–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zribi, I.; Bleton, J.; Moussa, F.; Abderrabba, M. GC-MS Analysis of the Volatile Profile and the Essential Oil Compositions of Tunisian Borago officinalis L.: Regional Locality and Organ Dependency. Ind. Crops Prod. 2019, 129, 290–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scotto, C.I.; Burger, P.; Khodjet el Khil, M.; Ginouves, M.; Prevot, G.; Blanchet, D.; Delprete, P.G.; Fernandez, X. Chemical composition and antifungal activity of the essential oil of Varronia schomburgkii (DC.) Borhidi (Cordiaceae) from plants cultivated in French Guiana. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2017, 29, 304–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.S.; Ibrahim, M.E.; Khalid, K.A. Investigation of essential oil constituents isolated from Trichodesma africanum (L.) growing wild in Egypt. Res. J. Med. Plant 2015, 9, 248–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, G.S. An aroma chemical profile: Anethole. Perfum. Flavorist 1993, 18, 11–17. [Google Scholar]

- Barra, A. Factors affecting chemical variability of essential oils: A review of recent developments. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2009, 4, 1147–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Sánchez, R.; Gálvez, C.; Ubera, J.L. Bioclimatic influence on essential oil composition in South Iberian Peninsular populations of Thymus zygis. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2012, 24, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şanli, A.; Karadoğan, T. Geographical impact on essential oil composition of endemic Kundmannia anatolica Hub.-Mor. (Apiaceae). Afr. J. Tradit. Complement. Altern. Med. 2017, 14, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scandiffio, R.; Geddo, F.; Cottone, E.; Querio, G.; Antoniotti, S.; Gallo, M.P.; Maffei, M.E.; Bovolin, P. Protective effects of (E)-β-caryophyllene (BCP) in chronic inflammation. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francomano, F.; Caruso, A.; Barbarossa, A.; Fazio, A.; La Torre, C.; Ceramella, J.; Mallamaci, R.; Saturnino, C.; Iacopetta, D.; Sinicropi, M.S. β-Caryophyllene: A sesquiterpene with countless biological properties. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 5420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.-J.; Kim, J.-M.; Lee, J.-C.; Kim, W.-K.; Chun, H.S. Protective effect of β-caryophyllene, a natural bicyclic sesquiterpene, against cerebral ischemic injury. J. Med. Food 2013, 16, 471–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jena, S.; Ray, A.; Sahoo, A.; Champati, B.B.; Padhiari, B.M.; Dash, B.; Nayak, S.; Panda, P.C. Chemical composition and antioxidant activities of essential oil from leaf and stem of Elettaria cardamomum from Eastern India. J. Essent. Oil-Bear. Plants 2021, 24, 538–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Bao, S.; Liu, J.; Wang, F.; Yao, G.; Han, P.; Wan, X.; Chen, C.; Jiang, H.; Zhang, X.; et al. The biosynthesis of the monoterpene tricyclene in E. coli through the appropriate truncation of plant transit peptides. Fermentation 2024, 10, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zheng, H.; Yang, S.; Qi, Y.; Li, W.; Kang, S.; Hu, H.; Hua, Q.; Wu, Y.; Liu, Z. Antimicrobial activity and mechanism of α-copaene against foodborne pathogenic bacteria and its application in beef soup. LWT–Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 195, 115848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Türkez, H.; Çelik, K.; Toğar, B. Effects of copaene, a tricyclic sesquiterpene, on human lymphocytes cells in vitro. Cytotechnology 2013, 65, 553–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lull, C.; Gil-Ortiz, R.; Cantín, Á. A chemical approach to obtaining α-copaene from clove oil and its application in the control of the medfly. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 5622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allenspach, M.; Steuer, C. α-Pinene: A never-ending story. Phytochemistry 2021, 190, 112857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, N.T.; Ho, D.V.; Doan, T.Q.; Le, A.T.; Raal, A.; Usai, D.; Madeddu, S.; Marchetti, M.; Usai, M.; Rappelli, P.; et al. In vitro antimicrobial activity of essential oil extracted from leaves of Leoheo domatiophorus Chaowasku, D.T. Ngo and H.T. Le in Vietnam. Plants 2020, 9, 453. [Google Scholar]

- Dosoky, N.S.; Kirpotina, L.N.; Schepetkin, I.A.; Khlebnikov, A.I.; Lisonbee, B.L.; Black, J.L.; Woolf, H.; Thurgood, T.L.; Graf, B.L.; Satyal, P.; et al. Volatile composition, antimicrobial activity, and in vitro innate immunomodulatory activity of Echinacea purpurea (L.) Moench essential oils. Molecules 2023, 28, 7330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stranden, M.; Liblikas, I.; König, W.A.; Almaas, T.J.; Borg-Karlson, A.-K.; Mustaparta, H. (–)-Germacrene D receptor neurones in three species of heliothine moths: Structure–activity relationships. J. Comp. Physiol. A 2003, 189, 563–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozuraitis, R.; Stranden, M.; Ramirez, M.I.; Borg-Karlson, A.-K.; Mustaparta, H. (–)-Germacrene D increases attraction and oviposition by the tobacco budworm moth Heliothis virescens. Chem. Senses 2002, 27, 505–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sciarrone, D.; Giuffrida, D.; Rotondo, A.; Micalizzi, G.; Zoccali, M.; Pantò, S.; Donato, P.; Rodrigues-das-Dores, R.G.; Mondello, L. Quali-quantitative characterization of the volatile constituents in Cordia verbenacea D.C. essential oil exploiting advanced chromatographic approaches and nuclear magnetic resonance analysis. J. Chromatogr. A 2017, 1524, 246–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewick, P.M. Medicinal Natural Products. A Biosynthetic Approach, 3rd ed.; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Casabianca, H.; Graff, J.B.; Faugier, V.; Fleig, F.; Grenier, C. Enantiomeric distribution studies of linalool and linalyl acetate: A powerful tool for authenticity control of essential oils. J. High Resol. Chromatogr. 1998, 21, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiallos, K.; Maldonado, Y.E.; Cumbicus, N.; Gilardoni, G. The Chemical and Enantioselective Analysis of a New Essential Oil Produced by the Native Andean Species Aiouea dubia (Kunth) Mez from Ecuador. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 44077–44086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasprzyk-Hordern, B. Pharmacologically active compounds in the environment and their chirality. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010, 39, 4466–4503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, A.C.R.; Lopes, P.M.; de Azevedo, M.M.B.; Costa, D.C.M.; Alviano, C.S.; Alviano, D.S. Biological activities of α-pinene and β-pinene enantiomers. Molecules 2012, 17, 6305–6316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salehi, B.; Upadhyay, S.; Erdogan Orhan, I.; Kumar Jugran, A.; Jayaweera, S.L.D.; Dias, D.A.; Sharopov, F.; Taheri, Y.; Martins, N.; Baghalpour, N.; et al. Therapeutic potential of α- and β-pinene: A miracle gift of nature. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishida, R.; Shelly, T.E.; Whittier, T.S.; Kaneshiro, K.Y. α-Copaene, A Potential Rendezvous Cue for the Mediterranean Fruit Fly, Ceratitis capitata. J. Chem. Ecol. 2000, 26, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Alfonso, I.; Vacas, S.; Primo, J. Role of α-copaene in the susceptibility of olive fruits to Bactrocera oleae (Rossi). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 11976–11979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kendra, P.E.; Owens, D.; Montgomery, W.S.; Narvaez, T.I.; Bauchan, G.R.; Schnell, E.Q.; Tabanca, N.; Carrillo, D. α-Copaene is an attractant, synergistic with quercivorol, for improved detection of Euwallacea nr. fornicatus (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Scolytinae). PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0179416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cueva, C.F.; Maldonado, Y.E.; Cumbicus, N.; Gilardoni, G. The Essential Oil from Cupules of Aiouea montana (Sw.) R. Rohde: Chemical and Enantioselective Analyses of an Important Source of (–)-α-Copaene. Plants 2025, 14, 2474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Dool, H.; Kratz, P.D. A Generalization of the Retention Index System Including Linear Temperature Programmed Gas—Liquid Partition Chromatography. J. Chromatogr. 1963, 11, 463–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Saint Laumer, J.Y.; Cicchetti, E.; Merle, P.; Egger, J.; Chaintreau, A. Quantification in Gas Chromatography: Prediction of Flame Ionization Detector Response Factors from Combustion Enthalpies and Molecular Structures. Anal. Chem. 2010, 82, 6457–6462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tissot, E.; Rochat, S.; Debonneville, C.; Chaintreau, A. Rapid GC-FID quantification technique without authentic samples using predicted response factors. Flavour Fragr. J. 2012, 27, 290–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilardoni, G.; Matute, Y.; Ramírez, J. Chemical and Enantioselective Analysis of the Leaf Essential Oil from Piper coruscans Kunth (Piperaceae), a Costal and Amazonian Native Species of Ecuador. Plants 2020, 9, 791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| N. | Compounds | 5%-Phenyl Methyl Polysiloxane | Polyethylene Glycol | Average | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RT | LRI a | LRI b | % | σ | Reference | RT | LRI a | LRI b | % | σ | Reference | % | ||

| 1 | tricyclene | 14.57 | 919 | 921 | 9.4 | 0.76 | [30] | 5.56 | 1008 | 1007 | 9.1 | 1.32 | [31] | 9.3 |

| 2 | α-pinene | 15.51 | 931 | 932 | 8.2 | 0.62 | [30] | 5.95 | 1019 | 1020 | 8.4 | 0.91 | [32] | 8.3 |

| 3 | α-fenchene | 16.59 | 944 | 945 | 2.1 | 0.17 | [30] | 7.43 | 1059 | 1059 | 2.2 | 0.18 | [33] | 2.2 |

| 4 | sabinene | 18.67 | 970 | 969 | 0.1 | 0.01 | [30] | 9.27 | 1105 | 1103 | 0.1 | 0.01 | [34] | 0.1 |

| 5 | β-pinene | 18.83 | 972 | 974 | 0.1 | 0.01 | [30] | 10.13 | 1119 | 1118 | 0.1 | 0.01 | [35] | 0.1 |

| 6 | myrcene | 20.24 | 989 | 988 | 0.2 | 0.01 | [30] | 13.10 | 1166 | 1167 | 0.3 | 0.02 | [36] | 0.3 |

| 7 | α-phellandrene | 21.12 | 994 | 1002 | 0.3 | 0.01 | [30] | 12.80 | 1161 | 1160 | 0.2 | 0.01 | [37] | 0.3 |

| 8 | p-cymene | 22.73 | 1015 | 1024 | 0.1 | 0.12 | [30] | 20.14 | 1269 | 1268 | 0.1 | trace | [38] | 0.1 |

| 9 | β-phellandrene | 23.09 | 1020 | 1025 | 1.5 | 0.08 | [30] | 15.56 | 1204 | 1203 | 1.2 | 0.02 | [39] | 1.6 |

| 10 | limonene | 23.11 | 1020 | 1024 | [30] | 16.67 | 1196 | 1196 | 0.4 | 0.01 | [40] | |||

| 11 | benzene acetaldehyde | 24.01 | 1032 | 1036 | 0.2 | 0.01 | [30] | 44.66 | 1648 | 1648 | 0.5 | 0.01 | [41] | 0.4 |

| 12 | terpinolene | 27.89 | 1083 | 1086 | trace | - | [30] | 20.88 | 1279 | 1280 | trace | - | [42] | trace |

| 13 | linalool | 28.86 | 1096 | 1095 | trace | - | [30] | - | - | - | - | - | trace | |

| 14 | n-nonanal | 29.18 | 1100 | 1100 | 0.4 | 0.01 | [30] | 8.92 | 1100 | 1398 | 0.3 | 0.02 | [43] | 0.4 |

| 15 | (2E,4E)-octadienal | 29.71 | 1101 | 1102 | trace | - | [30] | 41.21 | 1589 | 1590 | trace | - | [44] | trace |

| 16 | α-campholenal | 30.68 | 1114 | 1122 | trace | - | [30] | 34.91 | 1487 | 1487 | trace | - | [45] | trace |

| 17 | trans-pinocarveol | 31.59 | 1127 | 1135 | 0.1 | 0.01 | [30] | - | - | - | - | - | 0.1 | |

| 18 | trans-verbenol | 32.13 | 1135 | 1140 | 0.1 | 0.01 | [30] | 46.71 | 1684 | 1680 | 0.1 | 0.04 | [46] | 0.1 |

| 19 | pinocarvone | 33.35 | 1152 | 1160 | 0.1 | 0.01 | [30] | - | - | - | - | - | 0.1 | |

| 20 | trans-carveol | 37.65 | 1214 | 1215 | trace | - | [30] | 55.43 | 1843 | 1849 | 0.1 | 0.01 | [35] | 0.1 |

| 21 | δ-elemene | 46.07 | 1331 | 1335 | 0.1 | 0.01 | [30] | 33.10 | 1459 | 1460 | 0.1 | 0.01 | [47] | 0.1 |

| 22 | α-cubebene | 46.87 | 1344 | 1348 | 0.1 | 0.06 | [30] | 32.47 | 1450 | 1449 | trace | - | [47] | 0.1 |

| 23 | cyclosativene | 47.99 | 1362 | 1369 | 0.4 | 0.20 | [30] | 33.61 | 1467 | 1465 | 0.3 | 0.01 | [48] | 0.4 |

| 24 | ylangene | 48.29 | 1367 | 1368 | 0.2 | 0.01 | [37] | 33.89 | 1472 | 1472 | 0.3 | 0.01 | [47] | 0.3 |

| 25 | α-copaene | 48.61 | 1374 | 1373 | 10.2 | 0.32 | [30] | 34.49 | 1481 | 1481 | 10.5 | 0.6 | [47] | 10.4 |

| 26 | β-bourbonene | 49.15 | 1381 | 1387 | 1.6 | 0.05 | [30] | 36.10 | 1506 | 1504 | 1.7 | 0.09 | [47] | 1.7 |

| 27 | β-cubebene | 49.53 | 1387 | 1387 | 0.9 | 0.02 | [30] | 37.53 | 1529 | 1527 | 1.0 | 0.39 | [49] | 1.0 |

| 28 | α-gurjunene | 50.77 | 1404 | 1409 | 0.1 | 0.02 | [30] | 36.79 | 1517 | 1519 | 0.2 | 0.01 | [50] | 0.2 |

| 29 | (E)-β-caryophyllene | 51.38 | 1415 | 1417 | 13.3 | 0.4 | [30] | 40.91 | 1585 | 1587 | 13.3 | 0.64 | [51] | 13.3 |

| 30 | β-copaene | 51.98 | 1425 | 1426 | 0.4 | 0.01 | [52] | 40.43 | 1578 | 1580 | 0.4 | 0.01 | [53] | 0.4 |

| 31 | aromadendrene | 52.92 | 1441 | 1439 | 0.2 | 0.01 | [30] | 43.64 | 1631 | 1630 | 0.4 | 0.01 | [51] | 0.3 |

| 32 | α-humulene | 53.49 | 1451 | 1452 | 1.6 | 0.06 | [30] | 45.10 | 1656 | 1651 | 1.5 | 0.08 | [54] | 1.6 |

| 33 | allo-aromadendrene | 53.94 | 1459 | 1458 | 0.3 | 0.03 | [30] | 43.12 | 1622 | 1628 | 0.1 | 0.01 | [33] | 0.2 |

| 34 | γ-muurolene | 54.98 | 1476 | 1478 | 0.5 | 0.04 | [30] | 46.44 | 1679 | 1678 | 0.4 | 0.01 | [55] | 0.5 |

| 35 | germacrene D | 55.25 | 1481 | 1480 | 18.7 | 0.58 | [30] | 47.51 | 1698 | 1695 | 18.1 | 0.79 | [56] | 18.4 |

| 36 | β-selinene | 55.52 | 1486 | 1489 | 0.2 | 0.01 | [30] | 47.91 | 1705 | 1705 | 0.3 | 0.04 | [40] | 0.3 |

| 37 | bicyclogermacrene | 56.17 | 1497 | 1500 | 1.4 | 0.07 | [30] | 48.83 | 1722 | 1721 | 1.1 | 0.03 | [57] | 1.3 |

| 38 | trans-β-guaiene | 56.42 | 1501 | 1502 | 0.5 | 0.01 | [30] | 45.67 | 1666 | - | 0.7 | 0.73 | § | 0.6 |

| 39 | epi-cubebol | 57.28 | 1508 | 1493 | trace | - | [30] | 57.66 | 1886 | 1890 | 0.1 | 0.01 | [58] | 0.1 |

| 40 | δ-cadinene | 57.83 | 1517 | 1522 | 8.9 | 0.27 | [30] | 50.46 | 1751 | 1752 | 8.8 | 0.39 | [59] | 8.9 |

| 41 | germacrene B | 59.74 | 1552 | 1559 | 0.8 | 0.04 | [30] | 53.93 | 1815 | 1823 | 0.8 | 0.01 | [60] | 0.8 |

| 42 | spathulenol | 60.88 | 1572 | 1577 | 0.7 | 0.04 | [30] | 69.34 | 2128 | 2128 | 0.5 | 0.03 | [61] | 0.6 |

| 43 | caryophyllene oxide | 61.20 | 1578 | 1582 | 0.8 | 0.17 | [30] | 60.37 | 1939 | 1938 | 0.7 | 0.04 | [47] | 0.8 |

| 44 | viridiflorol | 62.40 | 1599 | 1592 | 0.8 | 0.03 | [30] | 67.29 | 2080 | 2086 | 0.2 | 0.01 | [62] | 0.5 |

| 45 | unidentified (mw = 236) | 69.76 | 1687 | - | 0.2 | 0.01 | [30] | 70.00 | 2145 | - | 0.5 | 0.04 | - | 0.4 |

| 46 | n-heneicosane | 78.23 | 2100 | 2100 | 1.4 | 0.05 | [30] | 68.24 | 2100 | 2100 | 0.5 | 0.03 | - | 1.0 |

| monoterpenes | 22.0 | 22.1 | 22.3 | |||||||||||

| oxygenated monoterpenoids | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.4 | |||||||||||

| sesquiterpenes | 60.4 | 60.0 | 60.8 | |||||||||||

| oxygenated sesquiterpenoids | 2.3 | 1.5 | 2.0 | |||||||||||

| others | 2.2 | 1.8 | 2.2 | |||||||||||

| total | 87.2 | 85.6 | 87.7 | |||||||||||

| Chiral Selector | Enantiomer | LRI | E.D. (%) | e.e. (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DAC | (1S,5S)-(-)-α-pinene | 915 | - | 100.0 |

| DAC | (1R,5R)-(+)-α-pinene | 916 | 100.0 | |

| DET | (1R,5R)-(+)-β-pinene | 949 | 78.3 | 56.6 |

| DET | (1S,5S)-(-)-β-pinene | 960 | 21.7 | |

| DET | (1R,5R)-(+)-sabinene | 978 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| DET | (1S,5S)-(-)-sabinene | 992 | - | |

| DET | (R)-(–)-α-phellandrene | 1020 | 1.3 | 97.4 |

| DET | (S)-(+)-α-phellandrene | 1023 | 98.7 | |

| DET | (S)-(-)-limonene | 1059 | 6.6 | 86.8 |

| DET | (R)-(+)-limonene | 1075 | 93.4 | |

| DET | (R)-(-)-β-phellandrene | 1049 | - | 100.0 |

| DET | (S)-(+)-β-phellandrene | 1062 | 100.0 | |

| DET | (R)-(-)-linalool | 1182 | 49.6 | 0.8 |

| DET | (S)-(+)-linalool | 1195 | 50.4 | |

| DET | (1R,2S,6S,7S,8S)-(-)-α-copaene | 1323 | 62.6 | 25.2 |

| DET | (1S,2R,6R,7R,8R)-(+)-α-copaene | 1324 | 37.4 | |

| DET | (R)-(+)-germacrene D | 1460 | 33.3 | 33.4 |

| DET | (S)-(-)-germacrene D | 1467 | 66.7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Cazares, K.; Maldonado, Y.E.; Cumbicus, N.; Gilardoni, G.; Malagón, O. Chemical and Enantioselective Analysis of the Leaf Essential Oil from Varronia crenata Ruiz & Pav. Growing in Ecuador. Molecules 2026, 31, 532. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31030532

Cazares K, Maldonado YE, Cumbicus N, Gilardoni G, Malagón O. Chemical and Enantioselective Analysis of the Leaf Essential Oil from Varronia crenata Ruiz & Pav. Growing in Ecuador. Molecules. 2026; 31(3):532. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31030532

Chicago/Turabian StyleCazares, Karem, Yessenia E. Maldonado, Nixon Cumbicus, Gianluca Gilardoni, and Omar Malagón. 2026. "Chemical and Enantioselective Analysis of the Leaf Essential Oil from Varronia crenata Ruiz & Pav. Growing in Ecuador" Molecules 31, no. 3: 532. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31030532

APA StyleCazares, K., Maldonado, Y. E., Cumbicus, N., Gilardoni, G., & Malagón, O. (2026). Chemical and Enantioselective Analysis of the Leaf Essential Oil from Varronia crenata Ruiz & Pav. Growing in Ecuador. Molecules, 31(3), 532. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31030532