Indolizinoquinolinedione Metal Complexes: Structural Characterization, In Vitro Antibacterial, and In Silico Studies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

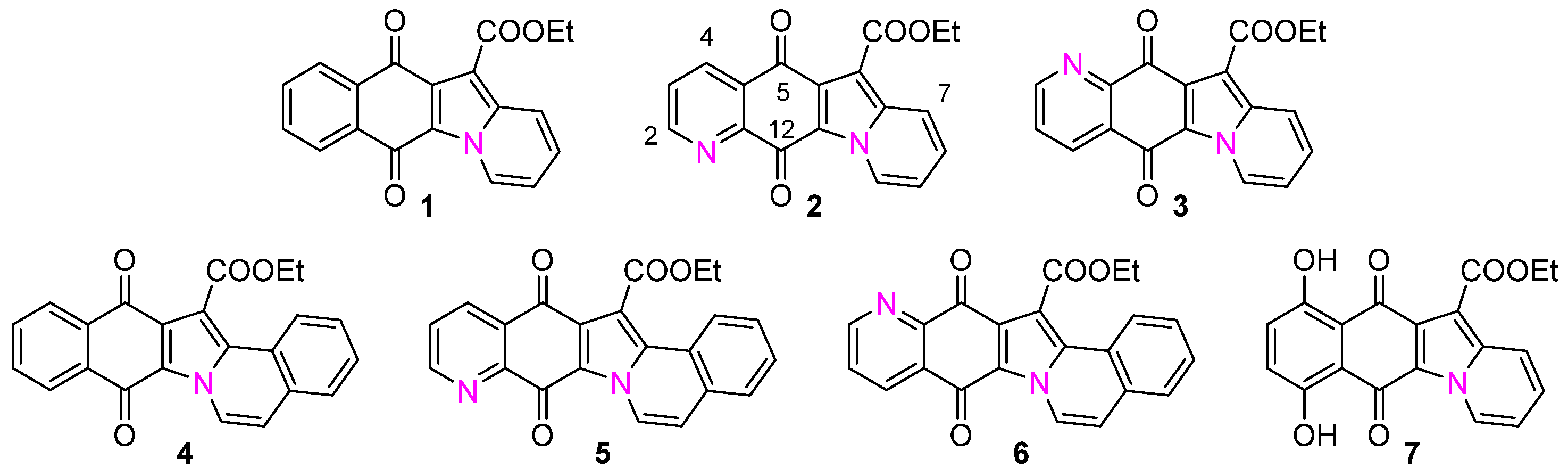

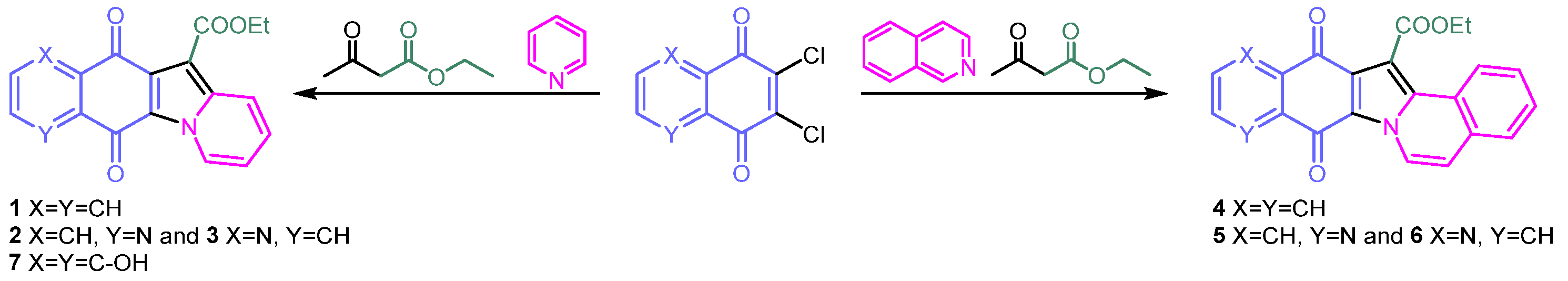

2.1. Synthesis of Molecules 1–7

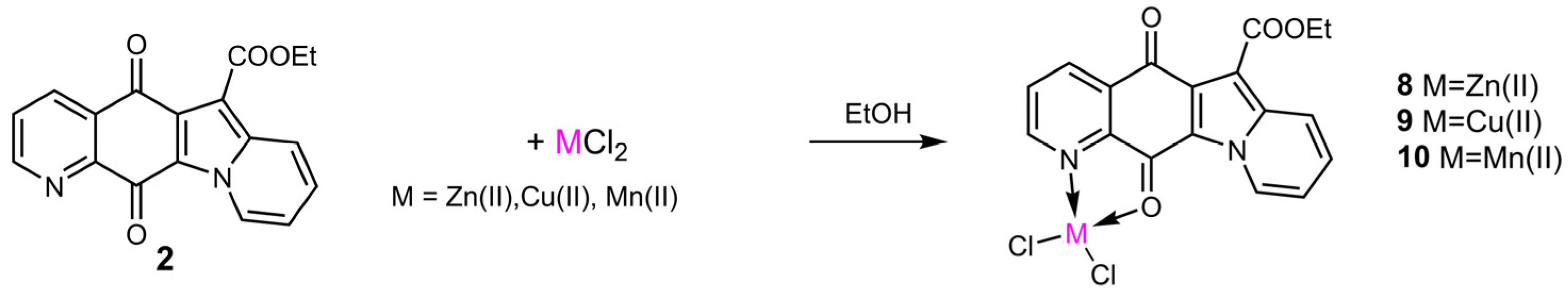

2.2. Synthesis and Structural Characterization of Metal Complexes

2.3. Biological Evaluation

2.4. Docking Calculations

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Chemistry

3.1.1. General

3.1.2. Synthesis and Structural Characterization of Metal Complexes

- (Ethyl 5,12-dihydro-5,12-dioxoindolizino[2,3-g]quinoline-6-carboxylate)zinc(II)chloride (8)1HNMR (400 MHz, CDCl3 + 2%CD3OD) δ 9.31(br. s, 1 H, H-2), 8.00 (dd, J = 8.0, 5.8 Hz, 1 H, H-3), 8.76 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 1 H, H-4), 8.49 (d, J = 9.1 Hz, 1 H, H-7), 7.69 (br. t, J = 7.9 Hz, 1 H, H-8), 7.46 (br.t, J = 7.0 Hz, 1 H, H-9), 9.83 (d, J = 7.1 Hz, 1 H, H-10), 4.56 (q, J = 6.7 Hz, 2 H, CH2), 1.54 (t, J = 6.7 Hz, 3 H, CH3).FT-IR (cm−1): 3727 (w), 3427 (w), 1720 (m), 1684 (m), 1620 (s), 1570 (s), 1503 (m), 1478 (m), 1314 (s), 1227 (s), 1190 (m), 1127 (w), 1014 (w), 790 (w), 759 (w), 687(w). ESI(+)-MS: m/z 419 [Lig 35Cl64Zn]+, 739 [2Lig 35Cl64Zn]+, 343 [Lig+Na]+, 321 [Lig+H]+; ESI(+)MS/MS on 419: m/z 391, 347.

- (Ethyl 5,12-dihydro-5,12-dioxoindolizino[2,3-g]quinoline-6-carboxylate)copper(II)chloride (9)FT-IR (cm−1): 3073 (w), 1686 (m), 1611 (s), 1576 (s), 1469 (m), 1306 (m), 1224 (vs), 1122 (m), 1084 (w), 1003 (w), 849 (w), 752 (s), 685 (w), 605 (w). ESI(+)-MS: m/z 418 [Lig 35Cl63Cu]+, 738 [2Lig 35Cl63Cu]+, 343 [Lig+Na]+; ESI(+)MS/MS on 418: m/z 390; on 738: m/z 418.

- (Ethyl 5,12-dihydro-5,12-dioxoindolizino[2,3-g]quinoline-6-carboxylate)manganese(II)chloride (10)FT-IR (cm−1): 3398 (w), 3107 (w), 2971 (w), 1684 (s), 1617 (s), 1578 (s), 1474 (s), 1408 (w), 1306 (m), 1227 (vs), 1189 (s), 1127 (w), 1080 (w), 1031 (w), 761 (m), 691 (w); ESI(+)-MS: m/z 410 [Lig 35Cl55Mn]+, 730 [2Lig 35Cl55Mn]+, 343 [Lig+Na]+.

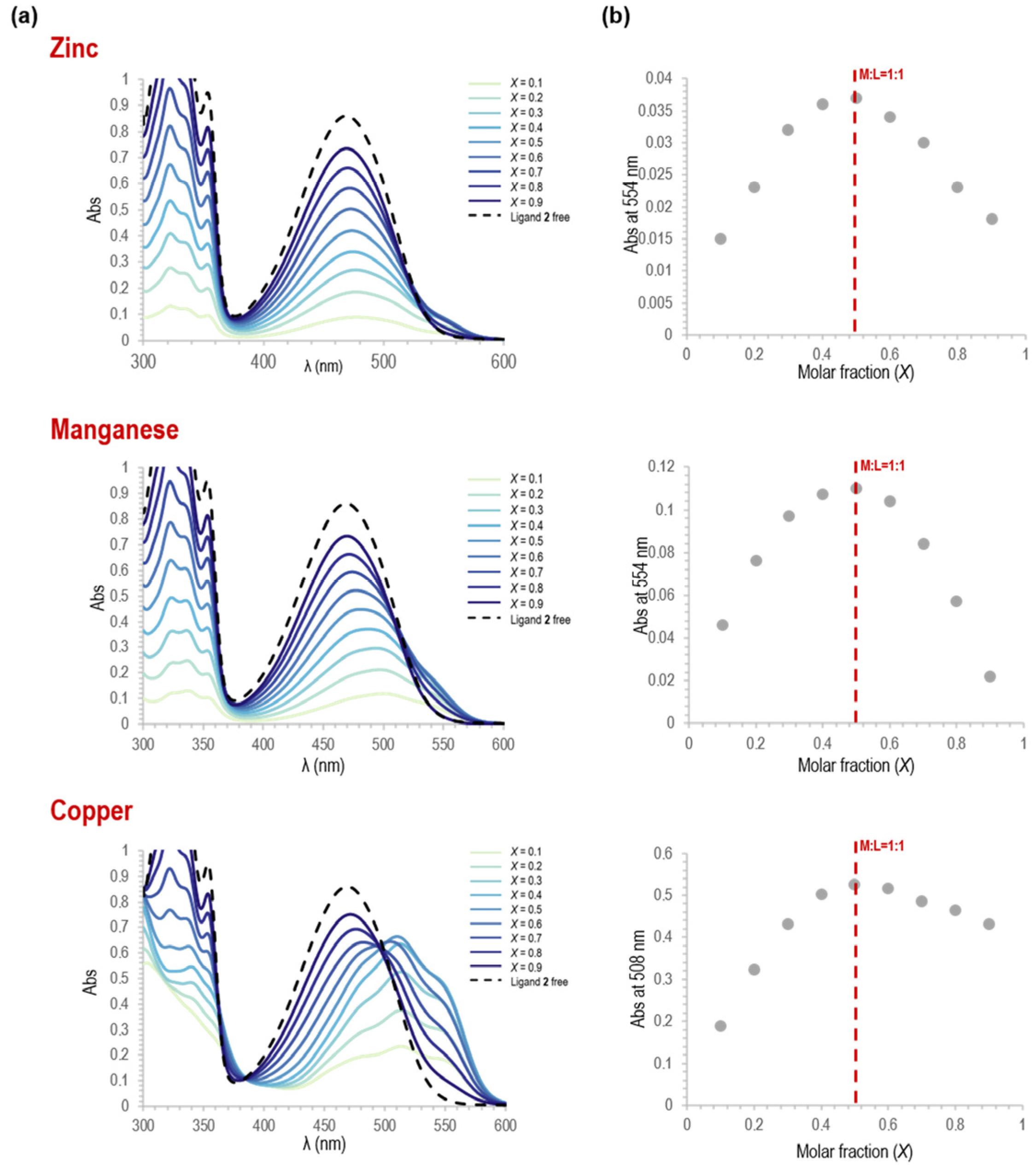

3.1.3. Stoichiometry Determination of the Metal Complexes 8–10 from Spectrophotometric Titrations

3.2. Biological Evaluation

Determination of Antibacterial Activity

3.3. Computational Analysis

3.3.1. DFT Calculation

3.3.2. Molecular Docking

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Antimicrobial Resistance. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/antimicrobial-resistance (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- World Health Organization. WHO Bacterial Priority Pathogens List, 2024; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024; Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/376776/9789240093461-eng.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Miller, W.R.; Arias, C.A. ESKAPE pathogens: Antimicrobial resistance, epidemiology, clinical impact and therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2024, 22, 598–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čiginskienė, A.; Dambrauskienė, A.; Rello, J.; Adukauskienė, D. Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia Due to Drug-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii: Risk Factors and Mortality Relation with Resistance Profiles, and Independent Predictors of In-Hospital Mortality. Medicina 2019, 55, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemire, J.A.; Harrison, J.J.; Turner, R.J. Antimicrobial activity of metals: Mechanisms, molecular targets and applications. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2013, 11, 371–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waters, J.E.; Stevens-Cullinane, S.; Siebenmann, L.; Jeannine Hess, J. Recent advances in the development of metal complexes as antibacterial agents with metal-specific modes of action. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2023, 75, 102347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uivarosi, V. Metal Complexes of Quinolone Antibiotics and Their Applications: An Update. Molecules 2013, 18, 11153–11197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defant, A.; Guella, G.; Mancini, I. Synthesis and in-vitro Cytotoxicity Evaluation of Novel Naphtindolizinedione Derivatives, Part II: Improved Activity for Aza-Analogues. Arch. Pharm. Chem. Life Sci. 2009, 342, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defant, A.; Guella, G.; Mancini, I. Synthesis and in Vitro Cytotoxicity Evaluation of Novel Naphthindolizinedione Derivatives. Arch. Pharm. Chem. Life Sci. 2007, 340, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defant, A.; Guella, G.; Mancini, I. Regioselectivity in the Multi-Component Synthesis of Indolizinoquinoline-5,12-dione Derivatives. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2006, 2006, 4201–4210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defant, A.; Guella, G.; Mancini, I. Microwave-Assisted Multicomponent Synthesis of Aza-, Diaza-, Benzo-, and Dibenzofluorenedione Derivatives. Synth. Commun. 2008, 38, 3003–3016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, L.; Huang, Z.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Bao, Y.; An, L.; Huang, S. Chitosan Dione Derivatives and Their Application in the Preparation of Antibacterial Drugs. Publication No. CN 1887884A, 3 January 2007. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Defant, A.; Rossi, B.; Viliani, G.; Guella, G.; Mancini, I. Metal-assisted regioselectivity in nucleophilic substitutions: A study by Raman spectroscopy and density functional theory calculations. J. Raman Spectrosc. 2010, 41, 1398–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Sun, D.; Yang, Y.; Li, M.; Li, H.; Chen, L. Discovery of metal-based complexes as promising antimicrobial agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 224, 113696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posokhov, Y.; Kus, M.; Biner, H.; Gümü, M.K.; Tuğcu, F.T.; Aydemir, E.; Kaban, S.; Içli, S. Spectral properties and complex formation with Cu2+ ions of 2- and 4-(N-arylimino)-quinolines. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2004, 161, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soldatović, T.; Selimović, E. Kinetic studies of the reactions between dichloride (1,2-diaminoethane)zinc(II) and biologically relevant nucleophiles in the presence of chloride. Prog. React. Kinet. Mec. 2018, 43, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieuwland, C.; Vermeeren, P.; Bickelhaupt, F.M.; Fonseca Guerra, C. Understanding chemistry with the symmetry-decomposed Voronoi deformation density charge analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 2023, 44, 2108–2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Marco, V.B.; Bombi, G. Electrospray mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) in the study of metal-ligand solution equilibria. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 2006, 25, 347–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lock, R.L.; Harry, E.J. Cell-division inhibitors: New insights for future antibiotics. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2008, 7, 324–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collin, F.; Karkare, S.; Maxwell, A. Exploiting bacterial DNA gyrase as a drug target: Current state and perspectives. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2011, 92, 479–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, C.A.; Panda, S.S. DNA Gyrase as a Target for Quinolones. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CLSI. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Tests CLSI Standard M02, 30th ed.; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Montgomery, J.A.; Vreven, T., Jr.; Kudin, K.N.; Burant, J.C.; et al. Gaussian 16, Revision A.03; Gaussian Inc.: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Becke, A.D. Density-functional thermochemistry III. The role of exact exchange. J. Chem. Phys. 1993, 98, 5648–5652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Yang, W.; Parr, R.G. Development of the Colle-Salvetti correlation-energy formula into a functional of the electron density. Phys. Rev. B 1988, 37, 785–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimme, S.; Ehrlich, S.; Goerigk, L. Effect of the damping function in dispersion corrected density functional theory. J. Comp. Chem. 2011, 32, 1456–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.; Chen, F. Multiwfn: A multifunctional wavefunction analyzer. J. Comput. Chem. 2012, 33, 580–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, T. A comprehensive electron wavefunction analysis toolbox for chemists. Multiwfn. J. Chem. Phys. 2024, 161, 082503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheeseman, J.R.; Trucks, G.W.; Keith, T.A.; Frisch, M.J. A comparison of models for calculating nuclear magnetic resonance shielding tensors. J. Chem. Phys. 1996, 104, 5497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Truhlar, D.G. A new local density functional for main-group thermochemistry, transition metal bonding, thermochemical kinetics, and noncovalent interactions. J. Chem. Phys. 2006, 125, 194101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Truhlar, D.G. Density Functionals with Broad Applicability in Chemistry. Acc. Chem. Res. 2008, 41, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritchard, B.P.; Altarawy, D.; Didier, B.; Gibson, T.D.; Windus, T.L. New Basis Set Exchange: An Open, Up-to-Date Resource for the Molecular Sciences Community. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2019, 59, 4814–4820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, G.M.; Huey, R.; Lindstrom, W.; Sanner, M.F.; Belew, R.K.; Goodsell, D.S.; Olson, A.J. Autodock4 and AutoDockTools4: Automated docking with selective receptor flexiblity. J. Comp. Chem. 2009, 16, 2785–2791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, T.J.; Hennessy, A.J.; Bax, B.; Brooks, G.; Brown, B.S.; Brown, P.; Cailleau, N.; Chen, D.; Dabbs, S.; Davies, D.T.; et al. Novel tricyclics (e.g., GSK945237) as potent inhibitors of bacterial type IIA topoisomerases. Bioorg Med. Chem. Lett. 2016, 26, 2464–2469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bax, B.D.; Chan, P.F.; Eggleston, D.S.; Fosberry, A.; Gentry, D.R.; Gorrec, F.; Giordano, I.; Hann, M.M.; Hennessy, A.; Hibbs, M.; et al. Type IIa Topoisomerase Inhibition by a New Class of Antibacterial Agents. Nature 2010, 466, 935–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skok, Z.; Barancokova, M.; Benek, O.; Cruz, C.D.; Tammela, P.; Tomasic, T.; Zidar, N.; Masic, L.P.; Zega, A.; Stevenson, C.E.M.; et al. Exploring the Chemical Space of Benzothiazole-Based DNA Gyrase B Inhibitors. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2020, 11, 2433–2440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliva, M.A.; Trambaiolo, D.; Lowe, J. Structural Insights Into the Conformational Variability of Ftsz. J. Mol. Biol. 2007, 373, 1229–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BIOVIA Discovery Studio visualizer 21.1.0.0 (Discovery Studio 2021 Client, Dassault Systèmes); Version 21.1.0.0; Dassault Systèmes: Vélizy-Villacoublay, France, 2021.

| Exptl δ(ppm) | Calcd. Charges | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In chloroform | ||||||

| Position 1 | 2 2 | Zn complex 2 | Δδ | 2 | Zn complex | Δq |

| H-2 | 8.98 | 9.31 | +0.33 | 0.0684 | 0.1197 | +0.0513 |

| H-3 | 7.66 | 8.00 | +0.34 | 0.0765 | 0.0932 | +0.0167 |

| H-4 | 8.54 | 8.76 | +0.22 | 0.0801 | 0.0960 | +0.0159 |

| H-7 | 8.34 | 8.49 | +0.15 | 0.0793 | 0.0890 | +0.0097 |

| H-8 | 7.49 | 7.69 | +0.20 | 0.0763 | 0.0859 | +0.0096 |

| H-9 | 7.26 | 7.46 | +0.20 | 0.0802 | 0.0894 | +0.0092 |

| H-10 | 9.93 | 9.83 | -0.10 | 0.0844 | 0.0999 | +0.0155 |

| Zn | - | - | - | - | 0.3885 | - |

| N-1 | - | - | - | −0.1789 | −0.0763 | +0.1026 |

| O in C-12 | - | - | - | −0.3077 | −0.2084 | +0.0993 |

| In methanol | ||||||

| Position 1 | 22 | Zn complex 2 | Δδ | 2 | Zn complex | Δq |

| H-2 | 8.96 | 9.16 | +0.20 | 0.0702 | 0.1238 | +0.0536 |

| H-3 | 7.84 | 8.01 | +0.17 | 0.0809 | 0.0978 | +0.0169 |

| H-4 | 8.60 | 8.73 | +0.13 | 0.0814 | 0.0986 | +0.017 |

| H-7 | 8.35 | 8.40 | +0.05 | 0.0798 | 0.0899 | +0.0101 |

| H-8 | 7.64 | 7.77 | +0.13 | 0.0804 | 0.0892 | +0.0088 |

| H-9 | 7.40 | 7.52 | +0.12 | 0.0832 | 0.0926 | +0.0094 |

| H-10 | 9.90 | 9.88 | +0.02 | 0.0846 | 0.0999 | +0.0153 |

| Zn | - | - | - | 0.3946 | - | |

| N-1 | - | - | - | −0.1878 | −0.0738 | +0.1140 |

| O in C-12 | - | - | - | −0.3149 | −0.2177 | +0.0972 |

| Chloroform | Methanol | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

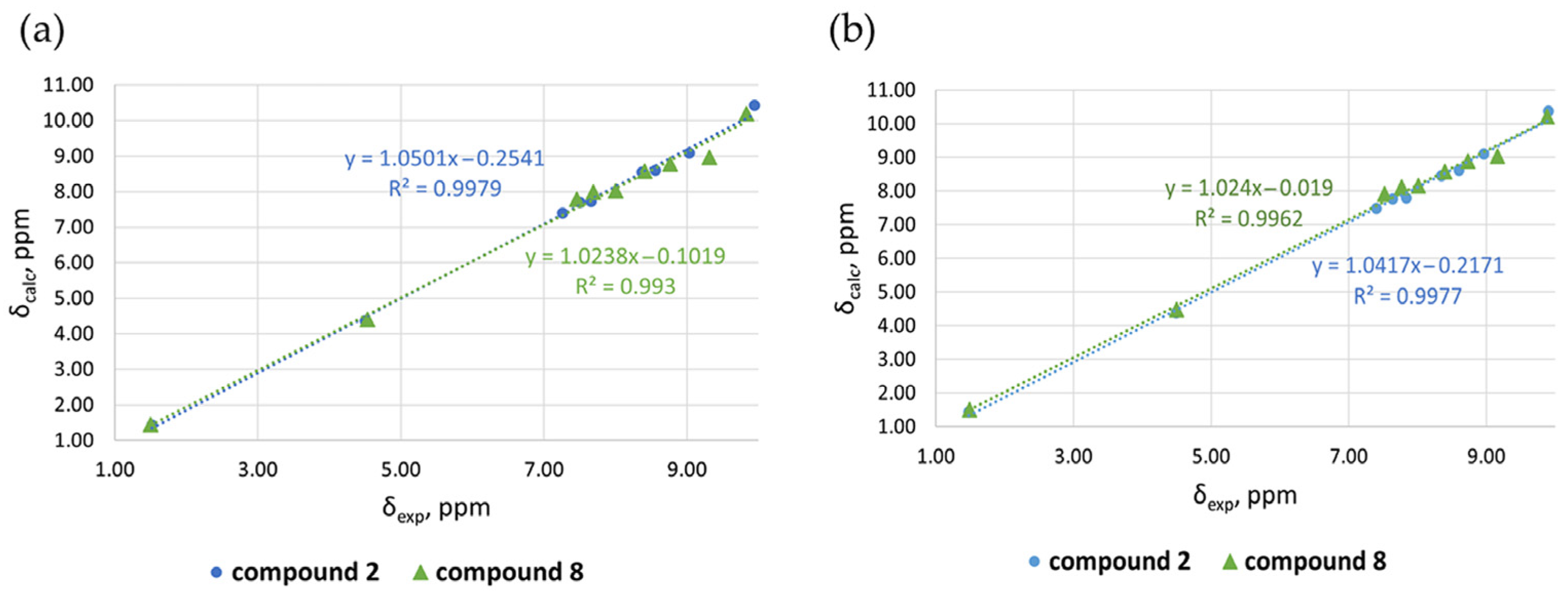

| Position1 | Exptl. | Calcd. | |Δ| | Exptl. | Calcd. | |Δ| |

| Compound 2 | ||||||

| H-10 | 9.94 | 10.42 | 0.48 | 9.90 | 10.37 | 0.47 |

| H-2 | 9.03 | 9.09 | 0.06 | 8.96 | 9.10 | 0.14 |

| H-4 | 8.56 | 8.60 | 0.04 | 8.60 | 8.61 | 0.01 |

| H-7 | 8.37 | 8.55 | 0.18 | 8.35 | 8.46 | 0.11 |

| H-3 | 7.66 | 7.72 | 0.06 | 7.84 | 7.79 | 0.05 |

| H-8 | 7.50 | 7.69 | 0.19 | 7.64 | 7.77 | 0.13 |

| H-9 | 7.26 | 7.40 | 0.14 | 7.40 | 7.48 | 0.08 |

| CH2 | 4.50 | 4.37 | 0.13 | 4.49 | 4.39 | 0.10 |

| CH3 | 1.52 | 1.43 | 0.09 | 1.48 | 1.43 | 0.05 |

| MAE 2 | 0.15 | 0.13 | ||||

| Compound 8 | ||||||

| H-10 | 9.83 | 10.19 | 0.36 | 9.88 | 10.21 | 0.33 |

| H-2 | 9.31 | 8.96 | 0.35 | 9.16 | 9.03 | 0.13 |

| H-4 | 8.76 | 8.78 | 0.02 | 8.73 | 8.88 | 0.15 |

| H-7 | 8.41 | 8.58 | 0.17 | 8.40 | 8.57 | 0.17 |

| H-3 | 8.00 | 8.02 | 0.02 | 8.01 | 8.15 | 0.14 |

| H-8 | 7.69 | 7.98 | 0.29 | 7.77 | 8.12 | 0.35 |

| H-9 | 7.46 | 7.78 | 0.32 | 7.52 | 7.91 | 0.39 |

| CH2 | 4.53 | 4.4 | 0.13 | 4.5 | 4.48 | 0.02 |

| CH3 | 1.50 | 1.44 | 0.06 | 1.49 | 1.51 | 0.02 |

| MAE 2 | 0.19 | 0.19 | ||||

| Compound | C-12(=O) | C-5(=O) + COOEt | d(Å) in the Minimized Structure | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | Calcd. | 1642 | 1678, 1671 | C12-O = 1.22 |

| Exptl. | 1641 | 1680, 1674 | ||

| 8 | Calcd. | 1605 | 1687, 1679 | C12-O = 1.24 O-Zn = 2.19, N-Zn = 2.18 |

| Exptl. Δν (2-Zn complex) | 1620 | 1684, 1720 | ||

| −0.21 | ||||

| 9 | Calcd. | 1602 | 1687, 1679 | C12-O = 1.24 O-Cu = 2.17, N-Cu = 2.10 |

| Exptl. Δν (2-Cu complex) | 1611 | 1692, 1686 | ||

| −30 | ||||

| 10 | Calcd. | 1484 | 1608(keto), 1669 (ester) | C12-O = 1.32 O-Mn = 1.90, N-Mn = 1.94 |

| Exptl. Δν (2-Mn complex) | 1475 | 1620,1683 | ||

| −166 | ||||

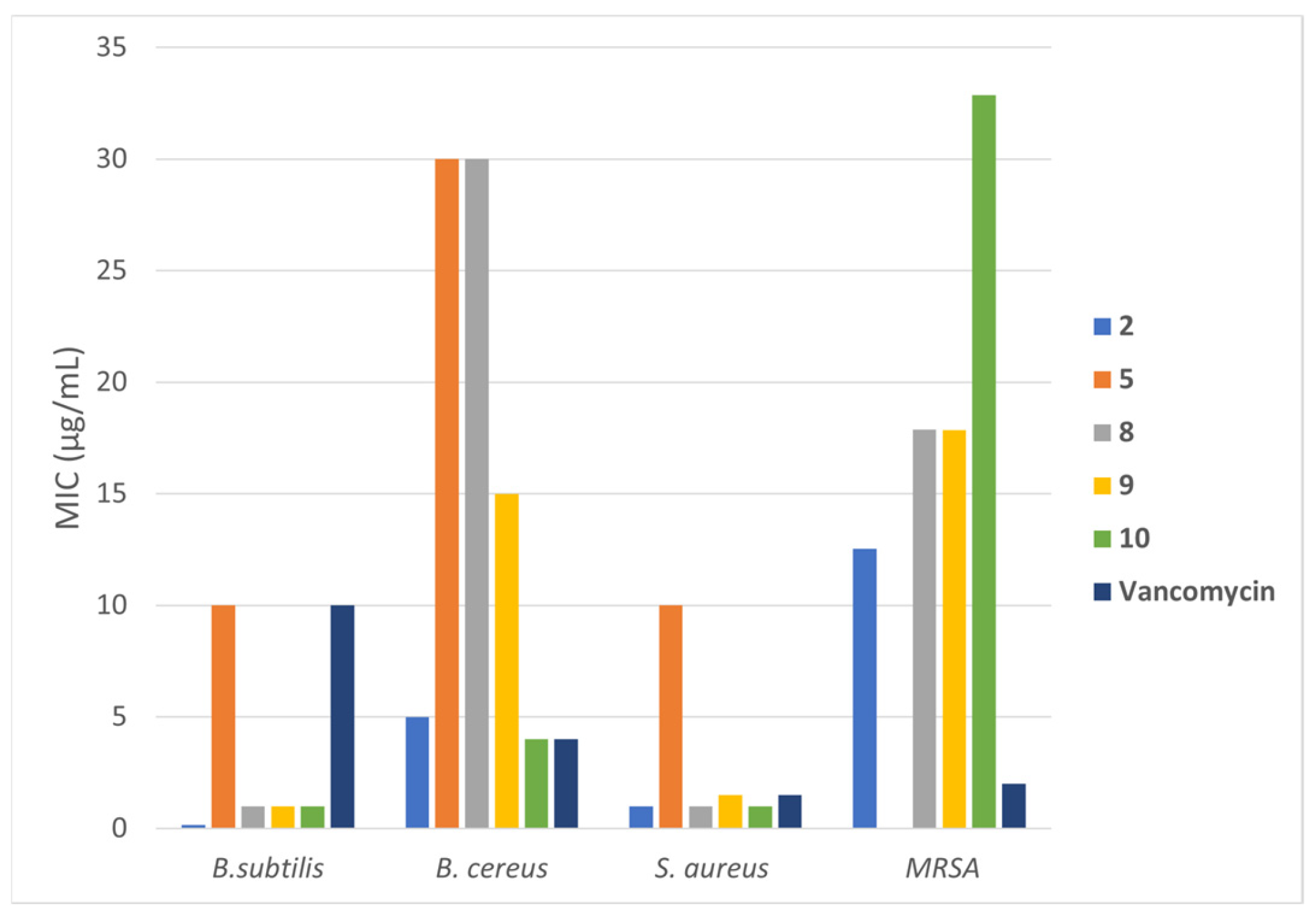

| MIC (µg/mL) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | B. subtilis | B. cereus | P. aeruginosa | E. coli | S. aureus |

| 1 | >1000 | >1000 | 1000 | >1000 | >1000 |

| 2 | 0.15 ± 0 | 5.0 ± 0.5 | >1000 | >1000 | 1.0 ± 0.3 |

| 3 | >1000 | >1000 | 1000 | >1000 | >1000 |

| 4 | >1000 | >1000 | >1000 | >1000 | >1000 |

| 5 | 10 ± 1 | 30 ± 2.5 | >1000 | >1000 | 10.0 ± 0.8 |

| 6 | >1000 | >1000 | >1000 | >1000 | 100 |

| 7 | >1000 | >1000 | 1000 | >1000 | >1000 |

| 8 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 30 ± 0 | >1000 | 300 | 1.0 ± 0.2 |

| 9 | 1 ± 0 | 15 ± 1 | >1000 | 150 | 1.5 ± 0.2 |

| 10 | 1.0 ± 0.4 | 4 ± 0.3 | 1000 | 1000 | 1 ± 0 |

| Penicillin G | >1000 | >1000 | >1000 | 150 | >1000 |

| Vancomycin | 10.0 ± 0.8 | 4 ± 0.5 | >1000 | >1000 | 1.5 ± 0.2 |

| Amoxicillin | >1000 | >1000 | >1000 | 15 ± 1 | >1000 |

| MRSA (ATCC 43300) | A. baumanii (OXAR) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diameter of Inhibition Zones (mm) | MIC (µg/mL) | Diameter of Inhibition Zones (mm) | MIC (µg/mL) | |

| ZnCl2 | 0 | - | 0 | - |

| CuCl2∙2H2O | 0 | - | 0 | - |

| MnCl2∙4H2O | 0 | - | 0 | - |

| 2 | 21.7 ± 1.2 | <12.53 | 0 | - |

| 8 | 23 ± 0 | <17.89 | 9 ± 0 | 286.34 |

| 9 | 31 ± 0 | <17.85 | 18.5 ± 0.7 | 35.70 |

| 10 | 26.5 ± 0.7 | <32.86 | 0 | - |

| Tetracycline (30 µg/mL) | 16 ± 0 | <2 | 14 ± 0 | 8 |

| Gentamycin (10 µg/mL) | 13 ± 0 | <2 | 13 ± 0 | 4 |

| Vancomycin (30 µg/mL) | 14 ± 0 | <2 | - | - |

| Cefotaxime (30 µg/mL) | - | - | 16.5 ± 0.7 | 16 |

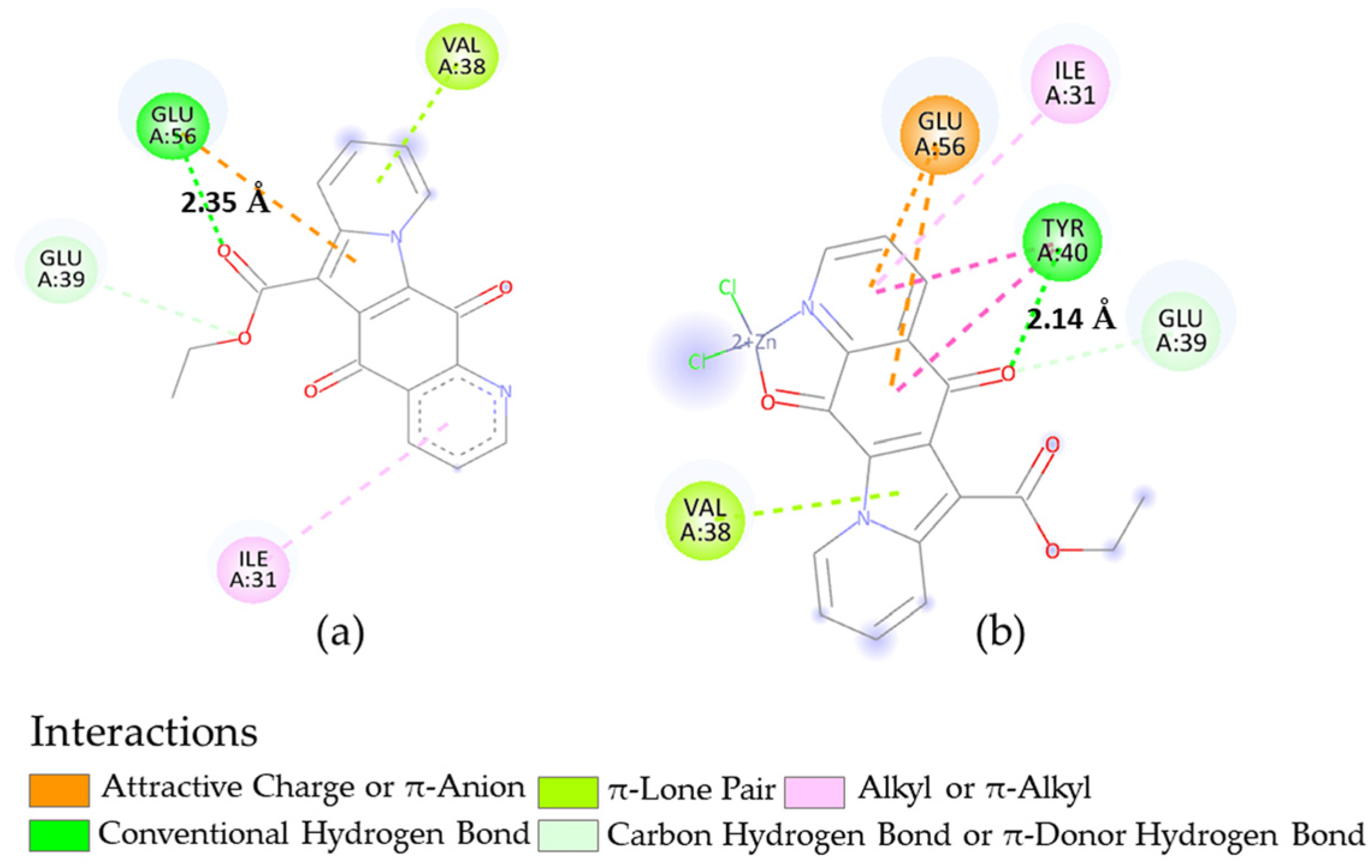

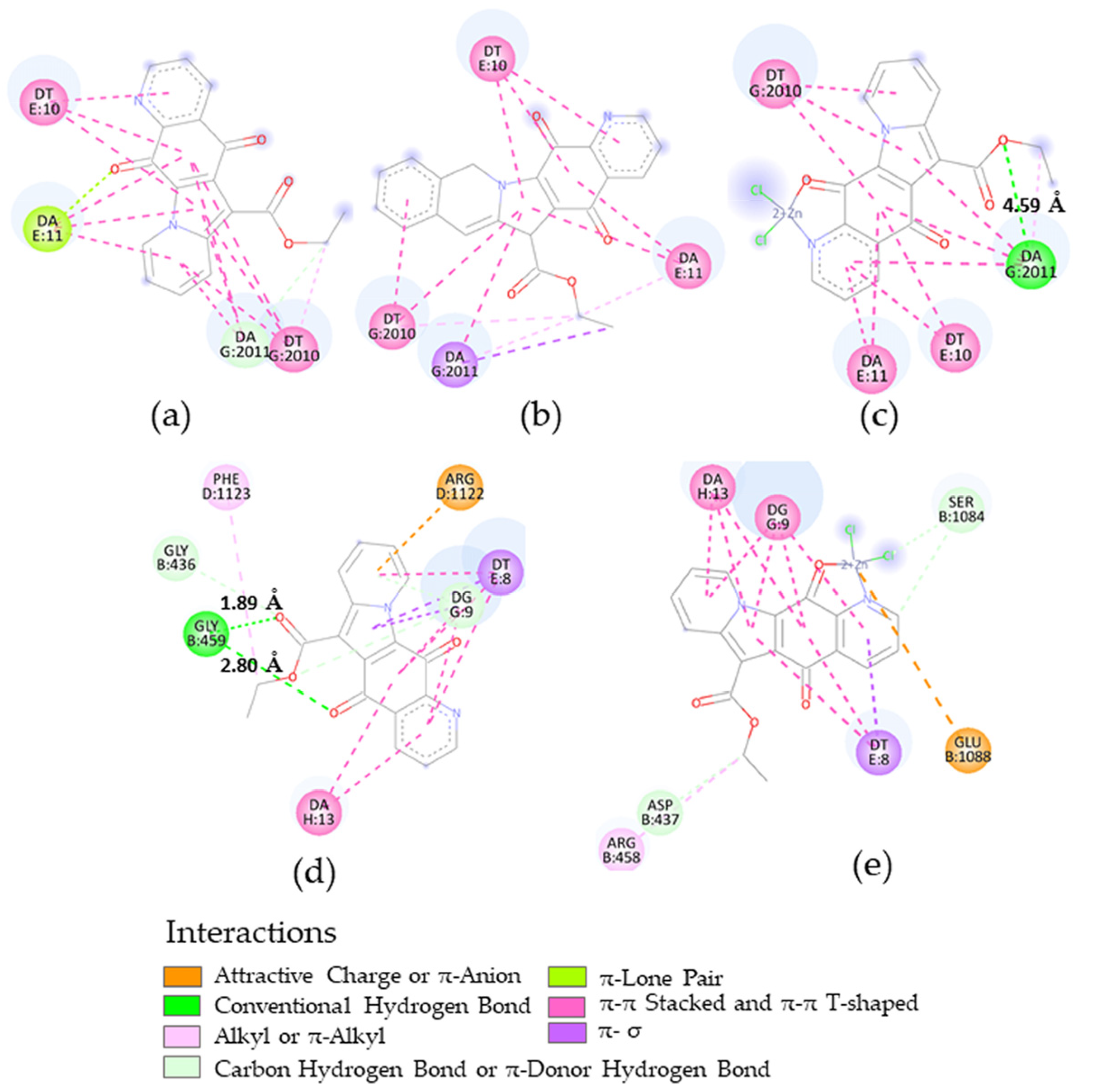

| Microorganism | Target | PDB-ID | Compound | Calcd. Binding ΔG (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B. subtilis | FtsZ | 2VAM | 2 | −7.35 |

| 8 | −6.73 | |||

| S. aureus | DNA gyrase | 5IWI | 2 | −7.24 |

| 5 | −7.71 | |||

| 8 | −6.60 | |||

| S. aureus N315 isolated as an MRSA | DNA gyrase | 2XCT | 2 | −8.79 |

| 8 | −8.58 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Vigna, J.; Marchesi, M.; Djinni, I.; Cajnko, M.M.; Sepčić, K.; Defant, A.; Mancini, I. Indolizinoquinolinedione Metal Complexes: Structural Characterization, In Vitro Antibacterial, and In Silico Studies. Molecules 2026, 31, 348. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31020348

Vigna J, Marchesi M, Djinni I, Cajnko MM, Sepčić K, Defant A, Mancini I. Indolizinoquinolinedione Metal Complexes: Structural Characterization, In Vitro Antibacterial, and In Silico Studies. Molecules. 2026; 31(2):348. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31020348

Chicago/Turabian StyleVigna, Jacopo, Michael Marchesi, Ibtissem Djinni, Miša Mojca Cajnko, Kristina Sepčić, Andrea Defant, and Ines Mancini. 2026. "Indolizinoquinolinedione Metal Complexes: Structural Characterization, In Vitro Antibacterial, and In Silico Studies" Molecules 31, no. 2: 348. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31020348

APA StyleVigna, J., Marchesi, M., Djinni, I., Cajnko, M. M., Sepčić, K., Defant, A., & Mancini, I. (2026). Indolizinoquinolinedione Metal Complexes: Structural Characterization, In Vitro Antibacterial, and In Silico Studies. Molecules, 31(2), 348. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31020348