1. Introduction

Lithium has become an incredibly important raw material for numerous technologies, particularly for the production of high-performance batteries for electric mobility and mobile electronic devices [

1]. The limited resources that can currently be economically exploited via mining make the development of new technologies and the exploitation of further mining areas attractive from both economic and ecological perspectives. Suitable process-compatible analysis methods are essential for powerful, efficient, and sustainable technical processes for lithium extraction. Inline methods offer advantages over offline methods in that chemical or physical measurements are available almost instantly while being non-destructive and contactless, thereby providing the basis for an efficient and agile technical process [

2]. This increases lithium output and reduces energy consumption on the one hand. On the other hand, since the salt solutions are corrosive, this approach of minimum sample preparation and treatment in a closed loop leads to minimum destruction of the measurement equipment.

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) is a widely used and well-established analytical tool with applications both in research, such as chemical structure elucidation, and in the industrial sector, for example, in quality control [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. Industrial NMR applications require monitoring tools that are robust against external influences in a process plant, generate a small magnetic stray field, and are easy to operate with low maintenance needs. Classic high-field NMR instruments with their superconducting magnets cooled with liquid helium and nitrogen are often unsuitable for this purpose. Furthermore, mobile applications are hardly feasible. Instead, low-field NMR with permanent magnets is well suited for this purpose and has already been used extensively for inline applications [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. A low-field NMR sensor for

7Li inline measurements on lithium-containing brines has also been developed and applied [

16]. However, when measuring nuclei other than

1H and samples with small concentrations of the target product, a stronger magnetic field

B0 should be used to increase the signal-to-noise ratio. The gyromagnetic ratio γ of

7Li is a factor of 2.573 smaller than that of

1H, the spin quantum number is 3/2, and the natural abundance is with 92.4% slightly lower than of

1H so that a stronger

B0 with inherently larger sensitivity is desirable for the development of process-compatible applications of

7Li NMR [

17,

18,

19].

In this study, 7Li NMR on flowing aqueous lithium chloride (LiCl) solutions was performed with a superconducting, cryogen-free magnet at a B0 of 4.7 T as a basis for the development of an inline-capable measurement method for monitoring the lithium concentration in process streams during lithium extraction. In addition to the influence of lithium concentration, the influences of flow velocity, repetition time, and polarization length were also investigated. A compact, industrial-grade Bruker minispec NF instrument was used as electronic unit in order to realize a potentially mobile and space-saving setup.

2. Results and Discussion

The maximum signal intensities

Imax of the Hahn echo envelopes are plotted as a function of the mean velocity to show the dependencies on the respective parameters. A value of 100% corresponds to the maximum signal intensity that can be correctly processed by the receiver. For the solution with

cLiCl = 27.1 g/L and

lpol = 30 cm,

Imax decreases with increasing

vmean (

Figure 1, red data points). However, for sufficiently small

vmean,

Imax increases compared to the static case of

vmean = 0 cm/s. This can be explained by the inflow effect, which is well known in flow NMR [

20,

21]: The flow causes fresh, polarized, but unexcited spins to flow into the sensitive area after previous excitation and echo detection during the repetition time. In the next experiment, their magnetization can be excited, thereby reducing integral saturation effects. This results in a larger integral signal intensity if the repetition time

RD is smaller than five times the longitudinal relaxation time

T1. For larger

vmean, the residence time in the static magnetic field

B0 along the polarization length of 0.3 m is not sufficient for an almost complete polarization due to the long

T1 of

7Li of around 8 s [

16]. This results in smaller

Imax values. Please note that

RD = 15 s in

Figure 1 already results in partial saturation in non-flowing liquids and, thus, smaller

Imax. For static measurements,

RD would have to be significantly larger.

The measurements show that the selected experimental setup with the cryogen-free magnet can be used for measurements on 7Li, even in flow. The impact of the flow velocity can clearly be derived from the signal intensity as a consequence of the inflow effect, even at the small pre-polarization length. The investigation of the influence of the internal pre-polarization length on the measurement results additionally provides a basis for further potential applications of the magnet. The large bore allows the tube to be wound up in the magnet, increasing lpol here to 120 cm.

The signal intensities are larger for the longer pre-polarization length

lpol = 1.2 m (

Figure 1, black data points), which is explained by the larger residence time and the more pronounced longitudinal magnetization build-up. However, the influence of the inflow effect can still be observed. A further increase in the internal

lpol will result in a larger signal intensity, making the magnet well suited for experiments with the need for pre-polarization, which is especially the case for moieties with long

T1 and low NMR sensitivity.

In addition to

vmean, the repetition time

RD was varied (

Figure 2). For

vmean = 0 cm/s,

Imax increases with increasing

RD. This is due to saturation effects as a result of the large

T1 of

7Li in the used sample. For

vmean > 0 cm/s, the influence of

lpol is clearly noticeable. Larger

lpol leads to larger

Imax. Furthermore, a plateau in

Imax occurs as a function of

RD for

vmean > 0 cm/s, which is explained by the inflow effect and the smaller influence of saturation effects. At small

RD and medium

vmean, an increase in

Imax due to the inflow effect can be seen when compared to

vmean = 0 cm/s. For larger velocities, the shorter residence time in

B0 and smaller pre-polarization lead to reduced

Imax. In addition, the outflow effect needs to be considered. The benefit of the described setup becomes obvious in the left part of the graph:

Imax is considerably larger at moderate velocities, even at the largest velocity of 10.7 cm/s, and

Imax is in the range of thermal polarization for the larger pre-polarization length. This observation allows for reducing the repetition time considerably to reasonable values: for example,

RD around 1 s instead of 8 s for

lpol = 1.2 m and

vmean = 6.4 cm/s, which results in eight times faster experiments or a significant gain in the signal-to-noise ratio. The observations are consistent with expectations, making the experimental setup and the selected parameter ranges suitable for these applications.

The three-dimensional (

vmean,

RD, and

lpol) parameter space was examined using full factorial design so that all inter-dependencies could be identified. The experiments with

cLiCl = 27.1 g/L show a sufficiently large signal intensity for the investigation of the respective influences for all parameter combinations (

Figure 3).

Spin echoes could also be detected for the aqueous solution of the smaller concentration

cLiCl = 15.6 g/L. The measurement settings have been adjusted accordingly.

Imax at

vmean > 4.2 cm/s is barely distinguishable from the noise level, so these data points are not shown (

Figure 4).

Also, at smaller concentrations, the positive influence of the longer lpol on Imax is clear. The experiments with smaller cLiCl reveal the limitations of the current measurement setup in terms of Li+ concentration and flow velocity range.

3. Materials and Methods

The superconducting magnet used for the investigations consists of a NbTi magnet coil and generates a maximum

B0 of 5 T in a warm vertical bore of 180 mm diameter (

Figure 5). The magnet is operated at 4 K and cooled without cryogen using a cryocooler. The cool-down process takes approximately 80 h, whereby only a power supply is required. In the cold state, the maximum field is reached within 42 min. The axial

B0 homogeneity in the relevant area is <1%, and neither cryogenic nor room temperature shim systems are included. Chemical resolution is not the focus of the measurement method as only Li

+ ions were observed. For compatibility reasons with results on a conventional helium-cooled NMR magnet, a

B0 of 4.7 T was selected, which corresponds to a

7Li Larmor frequency of 77.81 MHz. The electronic unit of a Bruker minispec NF series (Bruker BioSpin GmbH & Co. KG, Ettlingen, Germany) was used for control, pulse generation, and data acquisition, whereby the preamplifier was modified in order to extend the frequency range. A Bruker MICWB40

7Li 25 mm LTR micro imaging probe (Bruker BioSpin MRI GmbH, Ettlingen, Germany) was used for the experiments.

The Hahn echo pulse sequence was selected for the measurements [

22]. In this pulse sequence, a 90° excitation pulse is followed by a 180° refocusing pulse after the half echo time τ

e and then by the detection of a spin echo after a further delay of τ

e/2. In contrast to single-pulse acquisition, the Hahn echo pulse sequence refocuses the dephasing due to static magnetic field inhomogeneities, making it more suitable for measurements with the magnet used. Since the transverse NMR relaxation properties of the sample were not of interest for the fundamental investigations of this work, measurements were only performed at one echo time so that no echo train was acquired. This enables fast, quantitative measurements of lithium concentration, which is necessary for potential inline applications in quality control and process management.

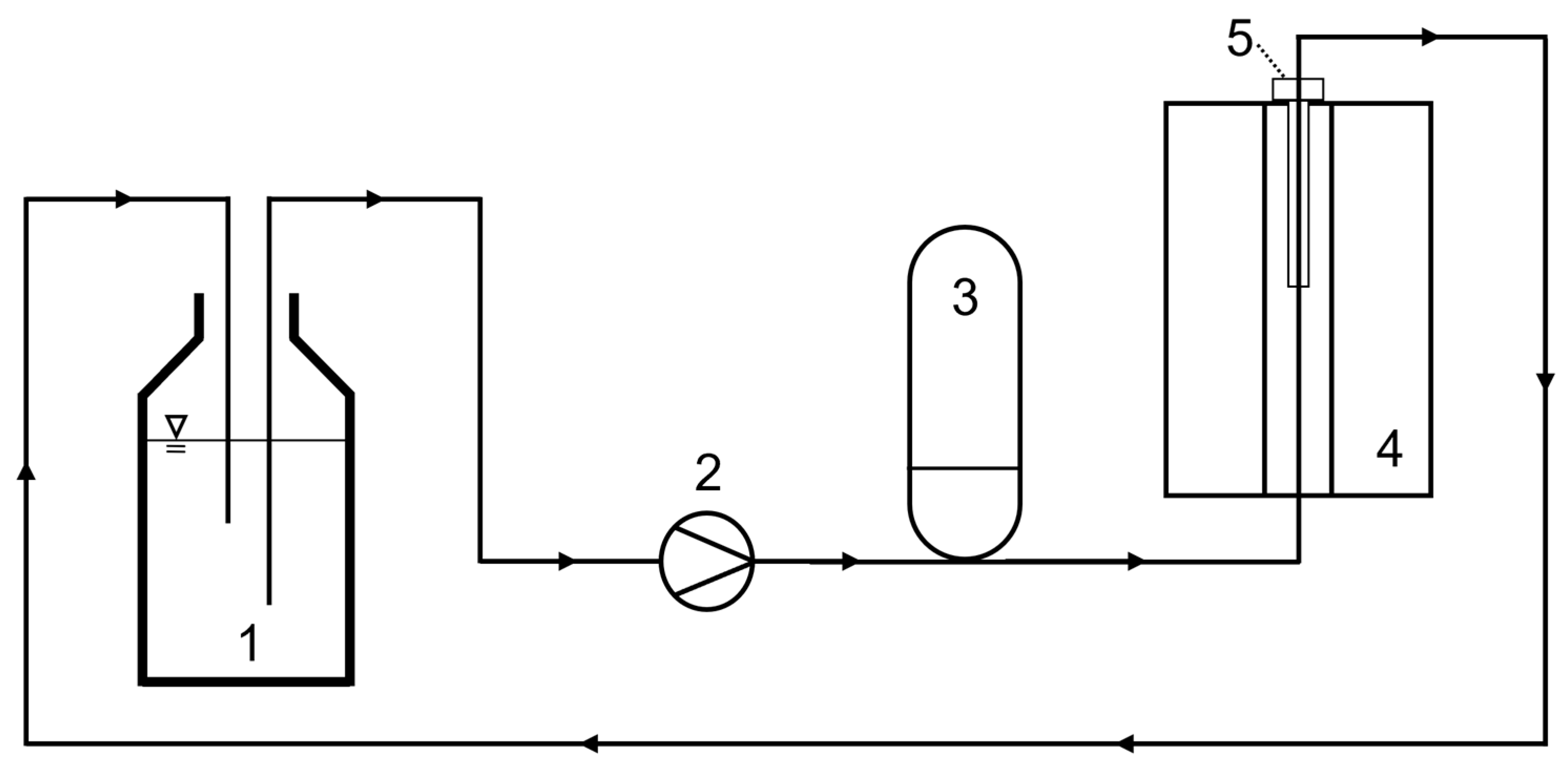

For the flow-through measurements and to show the principle on the lab scale, a fluidic circuit was built through the magnet. It comprised a reservoir tank, a peristaltic pump (Watson-Marlow 323 S, Watson-Marlow Ltd., Falmouth, UK), and a pressure compensation tank to reduce flow pulsation before the fluid enters the magnet (

Figure 6). A tube of polyurethane with an inner diameter of 7 mm was passed through the probe. The flow direction was selected from bottom to top, and the sample was recirculated for longer total experiment times. The probe was positioned in the magnet from the top and held in a reproducible position with a cover plate and precision spacers. A straight, i.e., shortest, possible arrangement of the tube results in a pre-polarization length

lpol of 30 cm from the lower edge of the magnet to the sensitive area of the probe. To realize a longer pre-polarization length, the tube was wound in a spiral and positioned in the magnet, resulting in

lpol = 120 cm.

To prove the sensitivity of the measurements on

7Li, two aqueous LiCl (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) solutions with concentrations of

cLiCl = 27.1 g/L and 15.6 g/L were prepared. The solutions were mixed by adding crystalline LiCl to deionized water and shaking the vessel for several minutes. Measurements were made on both solutions in flow at different mean flow velocities

vmean and repetition times (relaxation delay

RD). The NMR measurement parameters were determined individually for both concentrations (

Table 1).

4. Conclusions

The suitability of a cryogen-free magnet at 4.7 T for 7Li NMR on flowing samples, for example, in a lithium extraction plant, were investigated. The Hahn echo pulse sequence was used to measure signal intensities and thus make quantitative determinations about lithium concentration. By varying the mean flow velocity and the repetition time, information was obtained about the usability in a process plant and about the influences of the inflow effect on the NMR measurements in the desired area of application. The experiments with two different LiCl concentrations revealed corresponding limitations with regard to the LiCl concentration. The method can therefore be applied in the product streams of a production plant with sufficiently large lithium concentrations. In addition to the suitability of the cryogen-free magnet for 7Li NMR measurements, it was also shown that the magnet can be used for internal pre-polarization and that positive effects on the measurement results can be generated. Based on the investigations shown here, measurements could be made on lithium-containing solutions from a real production plant that offers, in addition, considerable paramagnetic relaxation enhancement in the natural composition for the reduction of Li measurement time. This effect could also be used to investigate the influence of other components, particularly those of these paramagnetic constituents. NMR relaxation measurements can also be considered for this purpose in order to gain in-depth insight, also in form of multiple echo sequences. Furthermore, measurements on other NMR-active nuclei and a comprehensive characterization of the pre-polarization properties are conceivable at the larger magnetic fields in comparison to permanent magnets. A further improvement in the measurement process can be achieved by further increasing the polarization length in the magnet. In addition, the sample volume can be increased to further improve the signal-to-noise ratio, which, together with multi-echo sequences, will result in the real inline NMR determination of Li ion content along the enrichment process.