Sustained Antifungal Protection of Peanuts Using Encapsulated Essential Oils

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Chemical Characterization of the EO Blend

2.2. Effect of Free and Encapsulated EOs Formulation Vapor on Aspergillus flavus

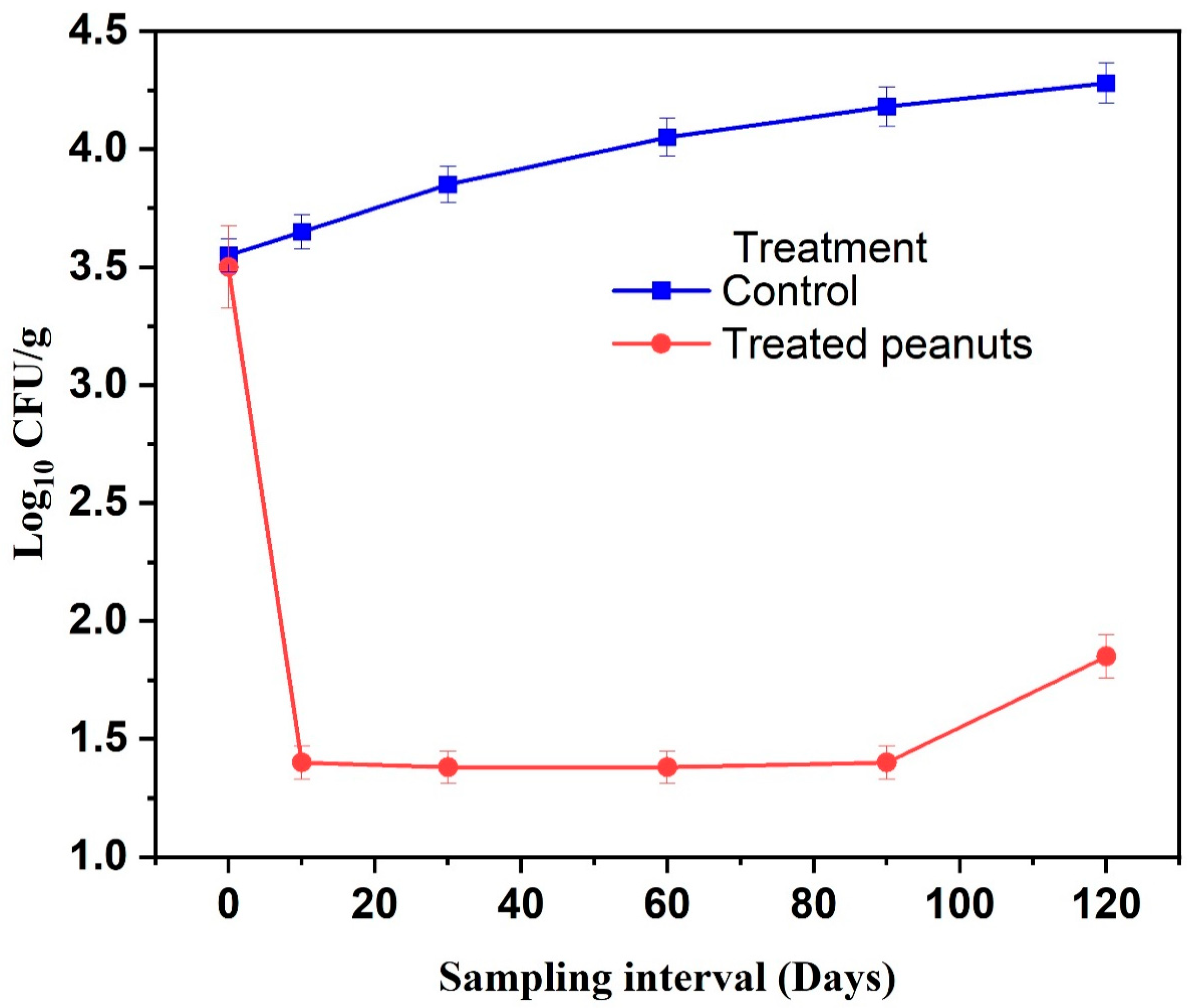

2.3. Effect of Encapsulated EO Formulation on Fungal Contamination

2.4. Effect on Germination Power

2.5. Antioxidant Activity of Free and Encapsulated Essential Oils

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Collection and Characterization of Essential Oils

3.2. Preparation of Dual-Size Microcapsules

3.3. Effect of Encapsulated EO Vapor on Aspergillus flavus

3.4. Antioxidant Activity of Free and Encapsulated EOs

3.5. Microcosm Assay

3.5.1. Evaluation of Fungal Population

3.5.2. Evaluation of Germination Power

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Arya, S.S.; Salve, A.R.; Chauhan, S. Peanuts as functional food: A review. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 53, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Çiftçi, S.; Suna, G. Functional components of peanuts (Arachis Hypogaea L.) and health benefits: A review. Future Foods 2022, 5, 100140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhtari, N.; Chabbi, M.; Bouassab, A. Measuring the impact of adhering to good practices on aflatoxin contamination in the peanut manufacturing chain: A Moroccan case study. Afr. J. Biol. Sci. 2024, 6, 1097–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhtari, N.; Farissi, H.E.L.; Mdarhri, Y.; Salim, R.; Hadda, T.B.E.N.; Chabbi, M. Green Microencapsulation Technology for Dual-Sized Delivery of O. compactum and M. communis Essential Oils: A Technological Innovation for Food Security and Fungal Control in Stored Peanuts. Mor. J. Chem. 2025, 13, 1501–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khadraji, A.; Mouradi, M.; Ghoulam, C. Antioxidant systems, germination in chickpea under drought. Mor. J. Chem. 2016, 4, 901–910. [Google Scholar]

- Girardi, N.S.; García, D.; Passone, M.A.; Nesci, A.; Etcheverry, M. Microencapsulation of Lippia turbinata essential oil and its impact on peanut seed quality preservation. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2017, 116, 227–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, J.; Xie, Y.; Guo, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Qian, H.; Yao, W. Application of edible coating with essential oil in food preservation. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 59, 2467–2480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathod, N.B.; Kulawik, P.; Ozogul, F.; Regenstein, J.M.; Ozogul, Y. Biological activity of plant-based carvacrol and thymol and their impact on human health and food quality. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 116, 733–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakasugi, L.P.; Bomfim, N.S.; Zoratto Romoli, J.C.; Nerilo, S.B.; Silva, M.V.; Oliveira, G.H.R.; Machinski, M., Jr. Antifungal and antiaflatoxigenic activities of thymol and carvacrol against Aspergillus flavus. Saúde Pesqui. 2021, 14, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleksic, V.; Knezevic, P. Antimicrobial and antioxidative activity of extracts and essential oils of Myrtus communis L. Microbiol. Res. 2014, 169, 240–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hmiri, S.; Harhar, H.; Rahouti, M. Antifungal activity of essential oils of two plants containing 1,8-cineole as major component: Myrtus communis and Rosmarinus officinalis. J. Mater. Environ. Sci. 2015, 6, 2967–2974. [Google Scholar]

- Kianersi, F.; Pour-Aboughadareh, A.; Majdi, M.; Poczai, P. Effect of Methyl Jasmonate on Thymol, Carvacrol, Phytochemical Accumulation, and Expression of Key Genes Involved in Thymol/Carvacrol Biosynthetic Pathway in Some Iranian Thyme Species. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 11124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, S.T.; Liao, P.; Crocoll, C.; Boachon, B.; Förster, C.; Leidecker, F.; Wiese, N.; Zhao, D.; Wood, J.C.; Buell, C.R.; et al. The biosynthesis of thymol, carvacrol, and thymohydroquinone in Lamiaceae proceeds via cytochrome P450s and a short-chain dehydrogenase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2110092118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimmalek, M.; Mirzakhani, M.; Pirbalouti, A.G. Essential oil variation among 21 wild myrtle (Myrtus communis L.) populations collected from different geographical regions in Iran. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2013, 51, 328–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndao, A.; Adjallé, K. Overview of the Biotransformation of Limonene and α-Pinene from Wood and Citrus Residues by Microorganisms. Waste 2023, 1, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouedrhiri, W.; Mechchate, H.; Moja, S.; Mothana, R.A.; Noman, O.M.; Grafov, A.; Greche, H. Boosted Antioxidant Effect Using a Combinatory Approach with Essential Oils from Origanum compactum, Origanum majorana, Thymus serpyllum, Mentha spicata, Myrtus communis, and Artemisia herba-alba: Mixture Design Optimization. Plants 2021, 10, 2817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chroho, M.; Rouphael, Y.; Petropoulos, S.A.; Bouissane, L. Carvacrol and Thymol Content Affects the Antioxidant and Antibacterial Activity of Origanum compactum and Thymus zygis Essential Oils. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, F.; Tu, X.-F.; Thakur, K.; Hu, F.; Li, X.-L.; Zhang, Y.-S.; Zhang, J.-G.; Wei, Z.-J. Comparison of antifungal activity of essential oils from different plants against three fungi. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2019, 134, 110821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angane, M.; Swift, S.; Huang, K.; Butts, C.A.; Quek, S.Y. Essential oils and their major components: An updated review on antimicrobial activities, mechanism of action and their potential application in the food industry. Foods 2022, 11, 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allizond, V.; Cavallo, L.; Roana, J.; Mandras, N.; Cuffini, A.M.; Tullio, V.; Banche, G. In Vitro Antifungal Activity of Selected Essential Oils against Drug-Resistant Clinical Aspergillus spp. Strains. Molecules 2023, 28, 7259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.; Zhao, S.-Q.; Zhang, J.; Huang, G.-Y.; Chen, L.-Y.; Zhao, F.-Y. Chemical composition, antimicrobial property and microencapsulation of Mustard (Sinapis alba) seed essential oil by complex coacervation. Food Chem. 2014, 165, 560–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Granados, A.D.P.F.; Duarte, M.C.T.; Noguera, N.H.; Lima, D.C.; Rodrigues, R.A.F. Impact of Microencapsulation on Ocimum gratissimum L. Essential Oil: Antimicrobial, Antioxidant Activities, and Chemical Composition. Foods 2024, 13, 3122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira Alencar, D.D.; de Souza, E.L.; da Cruz Almeida, E.T.; da Silva, A.L.; Oliveira, H.M.L.; Cavalcanti, M.T. Microencapsulation of Cymbopogon citratus D.C. Stapf Essential Oil with Spray Drying: Development, Characterization, and Antioxidant and Antibacterial Activities. Foods 2022, 11, 1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahmane, T.; Younes, N.B.B.; Ramdani, M.; Guendouz, A.B.; Elmsellem, H. Physico-chemical characterization and antimicrobial activity of an essential oil from the flowering umbels of wild Daucus carota L. subsp. Carota growing in Algeria. Mor. J. Chem. 2017, 5, 391–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maliki, I.; Almehdi, A.M.; Moussaoui, A.E.; Abdel-Rahman, I.; Ouahbi, A. Phytochemical screening and the antioxidant, antibacterial and antifungal activities of aqueous extracts from the leaves of Lippia triphylla planted in Morocco. Mor. J. Chem. 2020, 8, 943–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soliman, S.S.M.; Raizada, M.N. Interactions between co-habitating fungi elicit synthesis of Taxol from an endophytic fungus in host Taxus plants. Front. Microbiol. 2013, 4, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddou, S.; Mounime, K.; Loukili, E.; Ou-Yahia, D.; Hbika, A.; Idrissi, M.Y.; Legssyer, A.; Lgaz, H.; Asehraou, A.; Touzani, R.; et al. Investigating the Biological Activities of Moroccan Cannabis sativa L. Seed Extracts: Antimicrobial, Anti-inflammatory, and Antioxidant Effects with Molecular Docking Analysis. Mor. J. Chem. 2023, 11, 1116–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girardi, N.S.; García, D.; Robledo, S.N.; Passone, M.A.; Nesci, A.; Etcheverry, M. Microencapsulation of Peumus boldus oil by complex coacervation to provide peanut seeds protection against fungal pathogens. Ind. Crops Prod. 2016, 92, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| N° | Compounds | Essential Oil | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RT | Origanum compactum/Myrtus communis (75:25) | Origanum compactum | Myrtus communis | ||

| Area % | |||||

| 1 | α-Thujene | 5.063 | 1.61 | 4.81 | - |

| 2 | α-Pinene | 5.192 | 8.63 | 3.45 | 5.20 |

| 3 | Camphene | 5.454 | - | 0.62 | - |

| 4 | β-Thujene | 5.549 | - | - | 0.12 |

| 5 | 1-Octen-3-ol | 5.959 | 0.65 | 2.58 | - |

| 6 | 3-Octanone | 6.024 | 0.77 | 2.11 | |

| 7 | Myrcene | 6.092 | 1.65 | 4.67 | |

| 8 | Isoamyl isovalerate | 6.275 | - | - | 0.20 |

| 9 | 6-Methyl-3-heptanol | 6.221 | - | 0.72 | - |

| 10 | α-Phellandrene | 6.368 | - | 0.99 | - |

| 11 | (+)-4-Carene | 6.567 | 1.91 | 6.32 | - |

| 12 | m-Cymene | 6.715 | 13.40 | 9.90 | - |

| 13 | Eucalyptol | 6.834 | - | - | 65.70 |

| 14 | γ-Terpinene | 7.275 | 17.41 | 28.35 | - |

| 15 | Sabinenehydrate | 7.476 | - | 0.98 | - |

| 16 | Linalool oxide | 7.527 | - | - | 0.24 |

| 17 | α-Terpinolen | 7.770 | - | 0.66 | - |

| 18 | Linalool | 7.965 | 1.85 | 6.30 | 2.70 |

| 19 | cis-Verbenol | 8.178 | - | - | 0.53 |

| 20 | α-Campholenal | 8.437 | - | - | 0.41 |

| 21 | Limonene oxide, trans | 8.617 | - | - | 0.15 |

| 22 | Borneol | 9.172 | - | 1.05 | - |

| 23 | Terpinen-4-ol | 9.303 | 0.80 | 2.82 | - |

| 24 | α-Terpineol | 9.532 | 1.37 | - | 3.15 |

| 25 | p-menth-1-en-8-ol | 9.536 | - | 2.35 | - |

| 26 | Dihydrocarvone | 9.594 | - | 0.77 | - |

| 27 | Myrtenal | 9.605 | - | - | 0.99 |

| 28 | Verbenone | 9.828 | - | - | 0.73 |

| 29 | 2-Isopropyl-1-methoxy-4-methylbenzene | 10.252 | 0.76 | - | - |

| 30 | m-Cresol, 6-tert-butyl- | 10.253 | - | 2.92 | - |

| 31 | Pulegone | 10.267 | - | - | 0.23 |

| 32 | Carvoxime | 10.342 | - | - | 0.74 |

| 33 | Linalyl Acetate | 10.341 | 0.41 | - | - |

| 34 | Thymol | 11.030 | - | 2.54 | - |

| 35 | trans-Pinocarvyl acetate | 11.125 | - | - | 0.19 |

| 36 | o-Mentha-1(7),8-dien-3-ol | 11.276 | - | - | 0.77 |

| 37 | o-Cymen-5-ol | 11.290 | - | 12.02 | - |

| 38 | Carvacrol | 11.305 | 33.83 | 3.07 | - |

| 39 | trans-Verbenol | 11.491 | 5.65 | - | - |

| 40 | Myrtenyl acetate | 11.514 | - | - | 9.62 |

| 41 | Geraniol acetate | 12.216 | 0.31 | - | - |

| 42 | Methyleugenol | 12.607 | 0.17 | - | 1 |

| 43 | Caryophyllene | 12.952 | 1.39 | - | - |

| 44 | Caryophyllene oxide | 15.194 | 0.61 | - | 0.19 |

| Total identified (%) | 92.41 | 88.42 | 95.14 | ||

| Sampling Interval (Days) | Treatment | Aspergillus Section Flavi | Aspergillus Section Nigri | Penicillium spp. | Rhizopus | Fusarium sp. | Alternaria sp. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Treated | 2 ± 0.1 a | 1 ± 0.4 a | 0.8 ± 0.7 b | 0.4 ± 0.1 a | 0.2 ± 0.1 a | 0.12 ± 0.1 a |

| 0 | Control | 2 ± 0.1 a | 1 ± 0.4 a | 0.8 ± 0.7 b | 0.4 ± 0.1 a | 0.2 ± 0.1 a | 0.12 ± 0.1 a |

| 1 | Treated | 0.6 ± 0.5 a | 0.4 ± 0.2 a | 0.3 ± 0.2 a | 0.1 ± 0.9 b | 0.05 ± 0.2 a | 0.03 ± 0.2 a |

| 1 | Control | 2.1 ± 0.2 a | 1.2 ± 0.1 a | 0.9 ± 0.3 a | 0.5 ± 0.7 b | 0.3 ± 0.3 a | 0.15 ± 0.1 a |

| 5 | Treated | 0.5 ± 0.1 a | 0.35 ± 0.2 a | 0.3 ± 0.2 a | 0.1 ± 0.3 a | 0.05 ± 0.2 a | 0.03 ± 0.7 b |

| 5 | Control | 2.2 ± 0.3 a | 1.3 ± 0.1 a | 1 ± 0.1 a | 0.6 ± 0.8 b | 0.4 ± 0.1 a | 0.2 ± 0.6 b |

| 30 | Treated | 0.5 ± 0.1 a | 0.3 ± 0.7 b | 0.25 ± 0.5 b | 0.1 ± 0.3 a | 0.05 ± 0.3 a | 0.02 ± 0.5 b |

| 30 | Control | 2.5 ± 0.1 a | 1.5 ± 0.7 b | 1.2 ± 0.7 b | 0.7 ± 0.7 b | 0.5 ± 0.3 a | 0.25 ± 0.3 a |

| Assays | T0 | T1 (30 d) | T2 (60 d) | T3 (90 d) | T4 (120 d) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (%) | 52 ± 0.9 a | 50.5 ± 2.1 c | 50.8 ± 1.1 b | 50.2 ± 0.9 a | 50.5 ± 2.5 c |

| Treated Peanuts (%) | 52 ± 1.2 b | 50.2 ± 1.5 b | 50.5 ± 3.1 c | 49 ± 0.7 a | 50.1 ± 2.2 c |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Mokhtari, N.; Farissi, H.E.; Cacciola, F.; Mdarhri, Y.; Bouassab, A.; Chabbi, M. Sustained Antifungal Protection of Peanuts Using Encapsulated Essential Oils. Molecules 2026, 31, 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010038

Mokhtari N, Farissi HE, Cacciola F, Mdarhri Y, Bouassab A, Chabbi M. Sustained Antifungal Protection of Peanuts Using Encapsulated Essential Oils. Molecules. 2026; 31(1):38. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010038

Chicago/Turabian StyleMokhtari, Narjisse, Hammadi El Farissi, Francesco Cacciola, Yousra Mdarhri, Abderrahman Bouassab, and Mohamed Chabbi. 2026. "Sustained Antifungal Protection of Peanuts Using Encapsulated Essential Oils" Molecules 31, no. 1: 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010038

APA StyleMokhtari, N., Farissi, H. E., Cacciola, F., Mdarhri, Y., Bouassab, A., & Chabbi, M. (2026). Sustained Antifungal Protection of Peanuts Using Encapsulated Essential Oils. Molecules, 31(1), 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010038