Biomedical Applications of Chitosan-Coated Gallium Iron Oxide Nanoparticles GaxFe(3−x)O4 with 0 ≤ x ≤ 1 for Magnetic Hyperthermia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

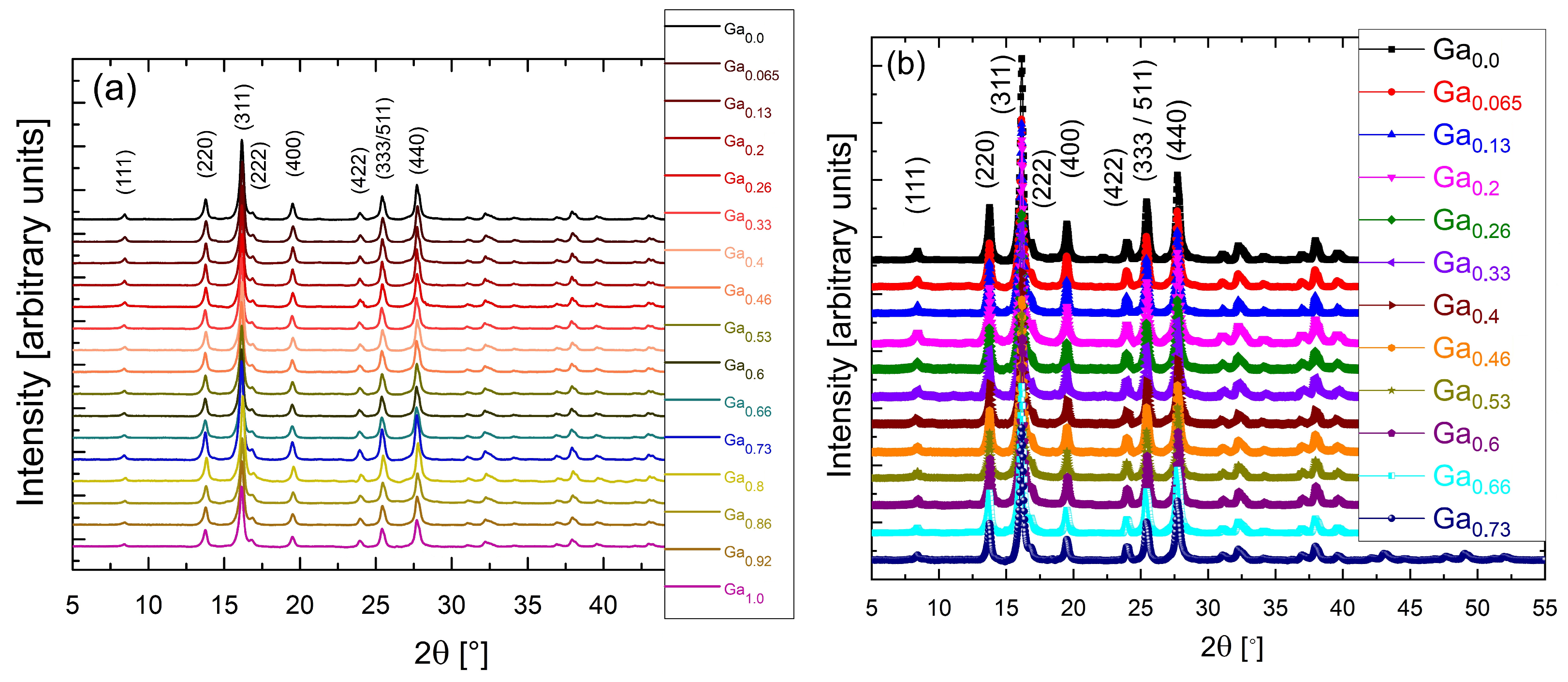

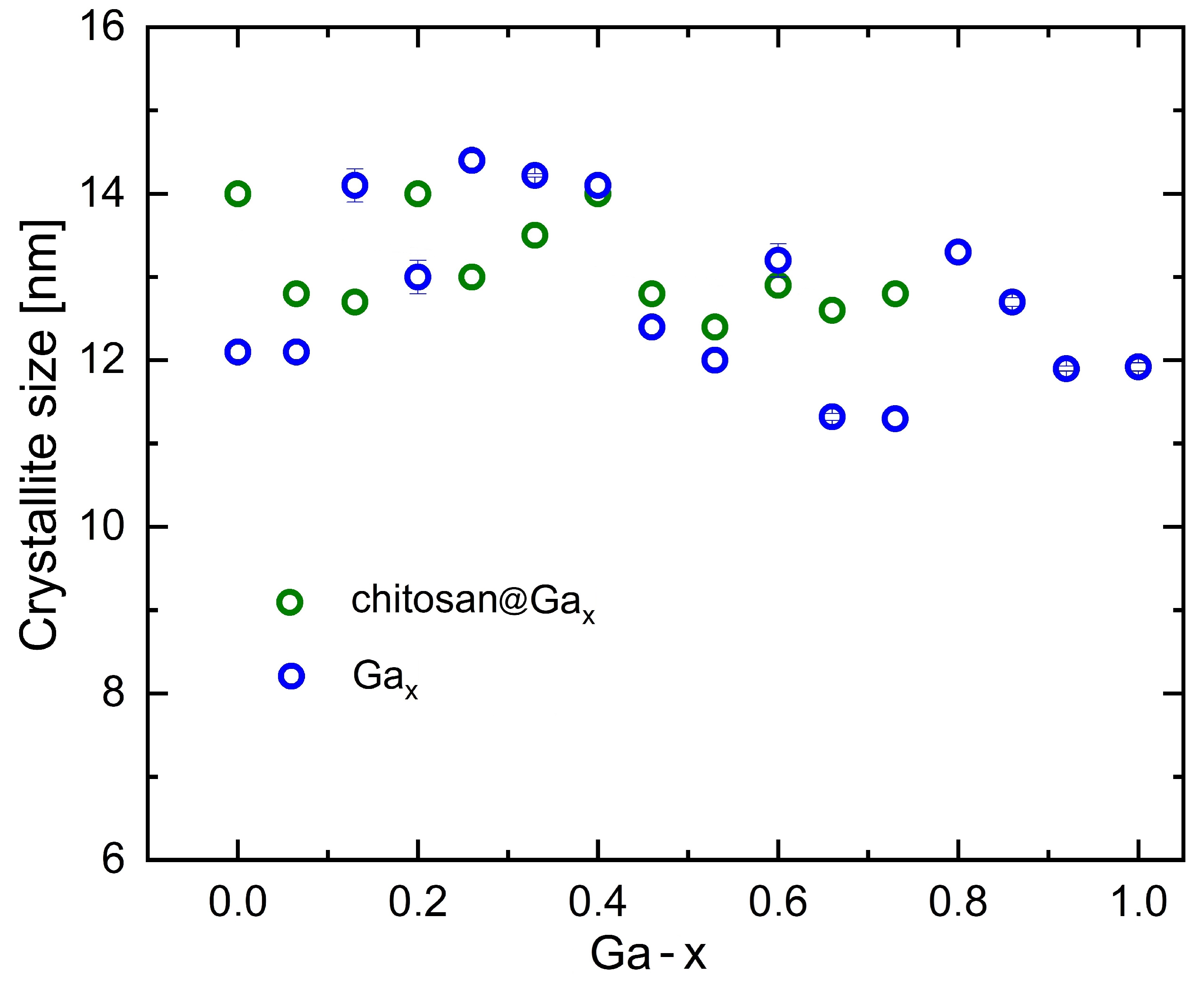

2.1. X-Ray Diffraction

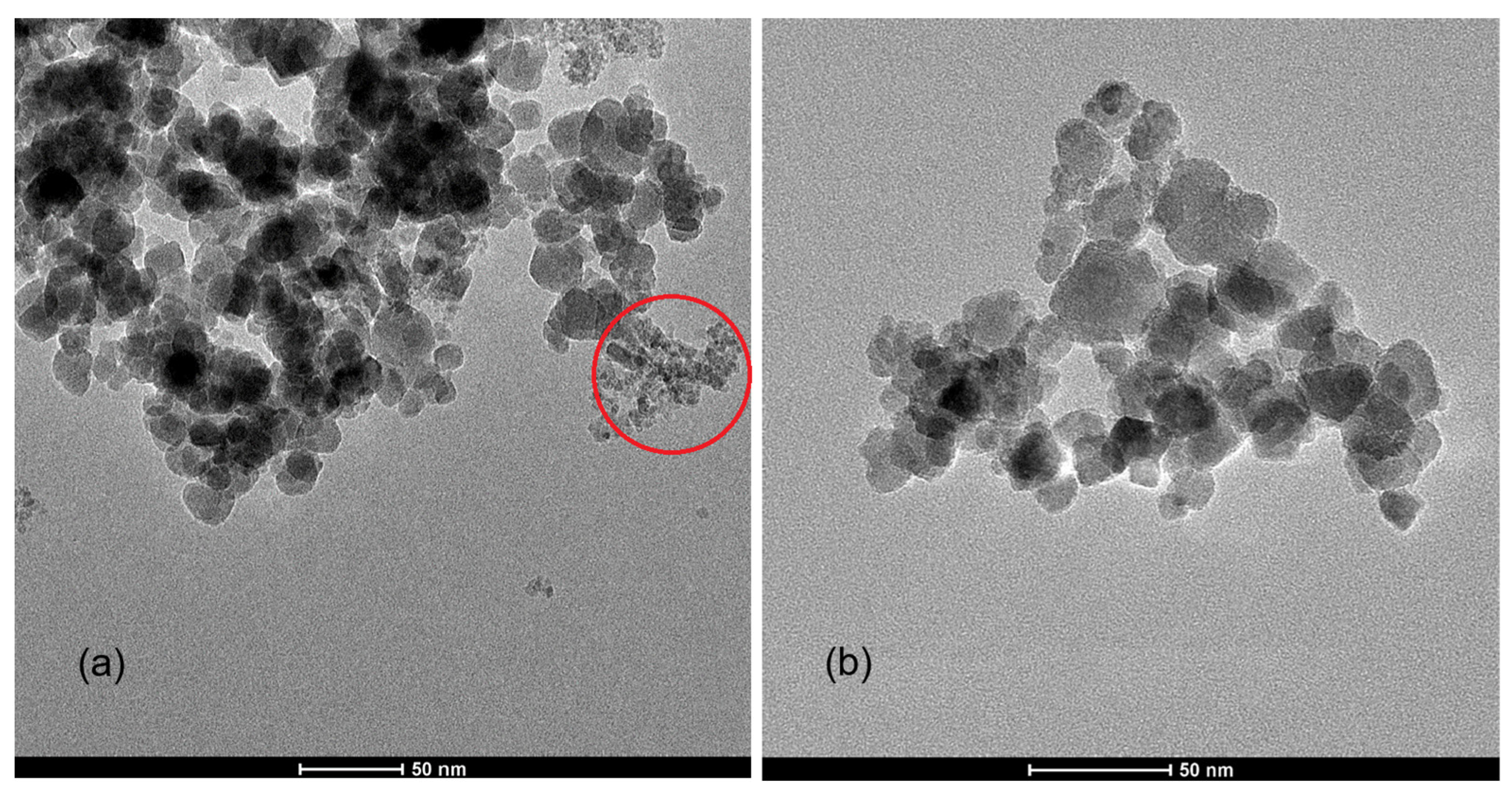

2.2. Transmission Electron Microscopy Images

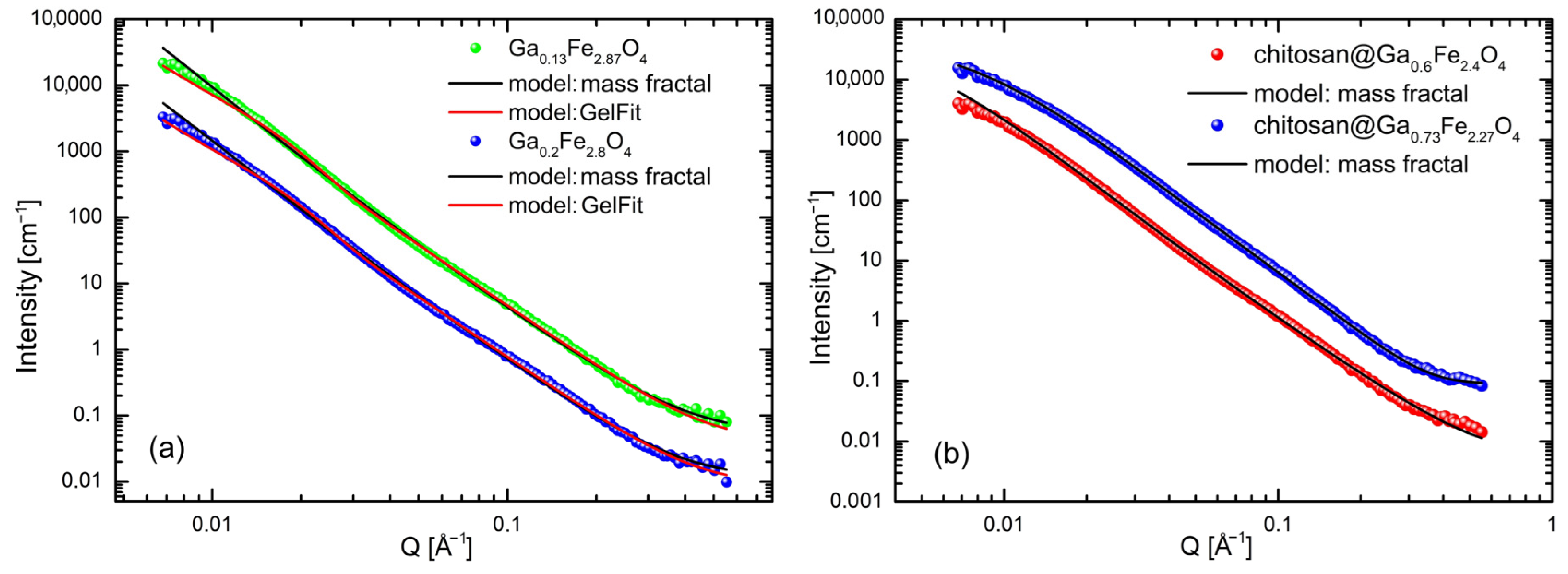

2.3. Small-Angle Neutron Scattering Measurements

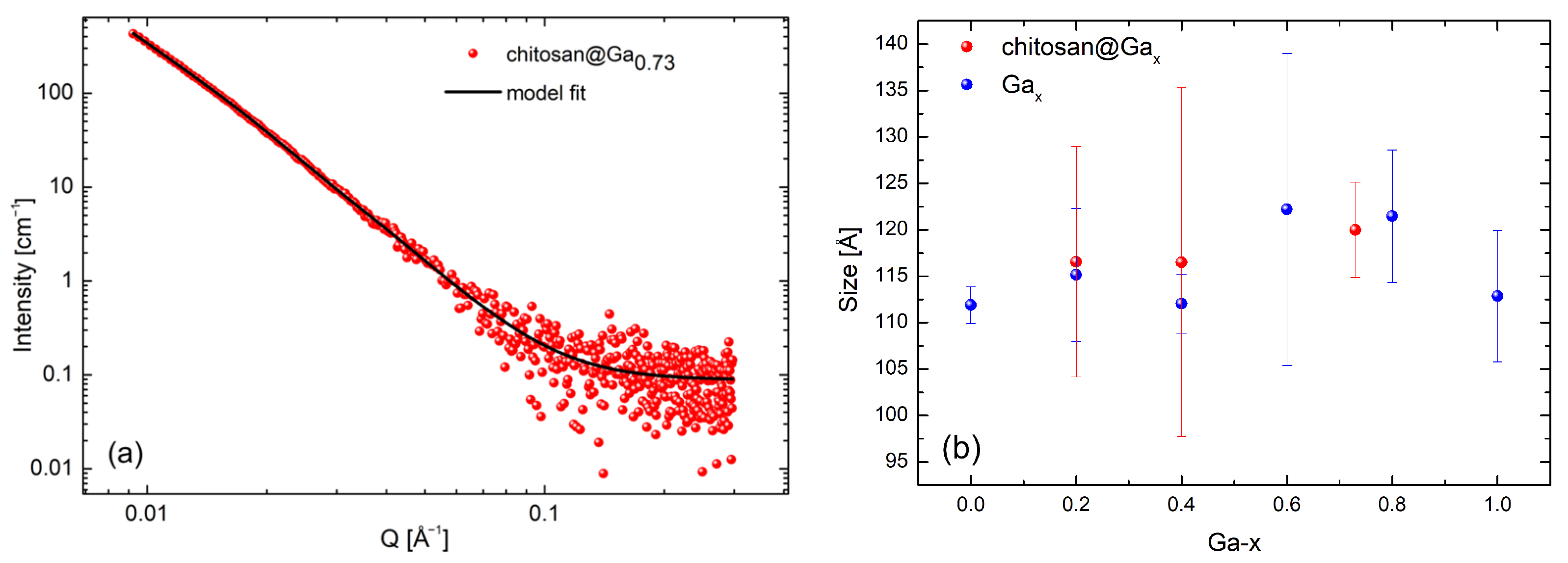

2.4. Small-Angle X-Ray Scattering Analysis

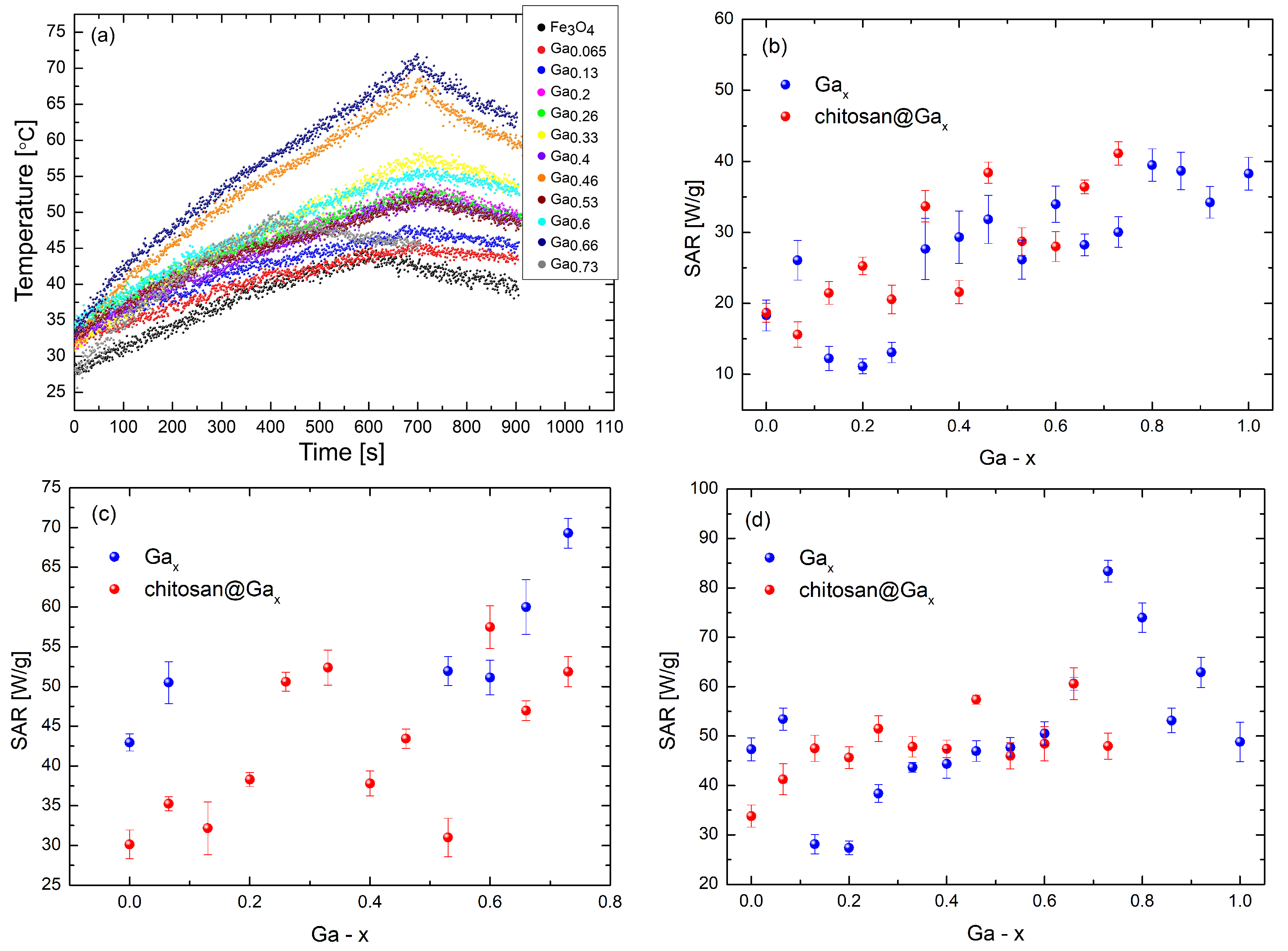

2.5. Characterization of the Specific Absorption Rate

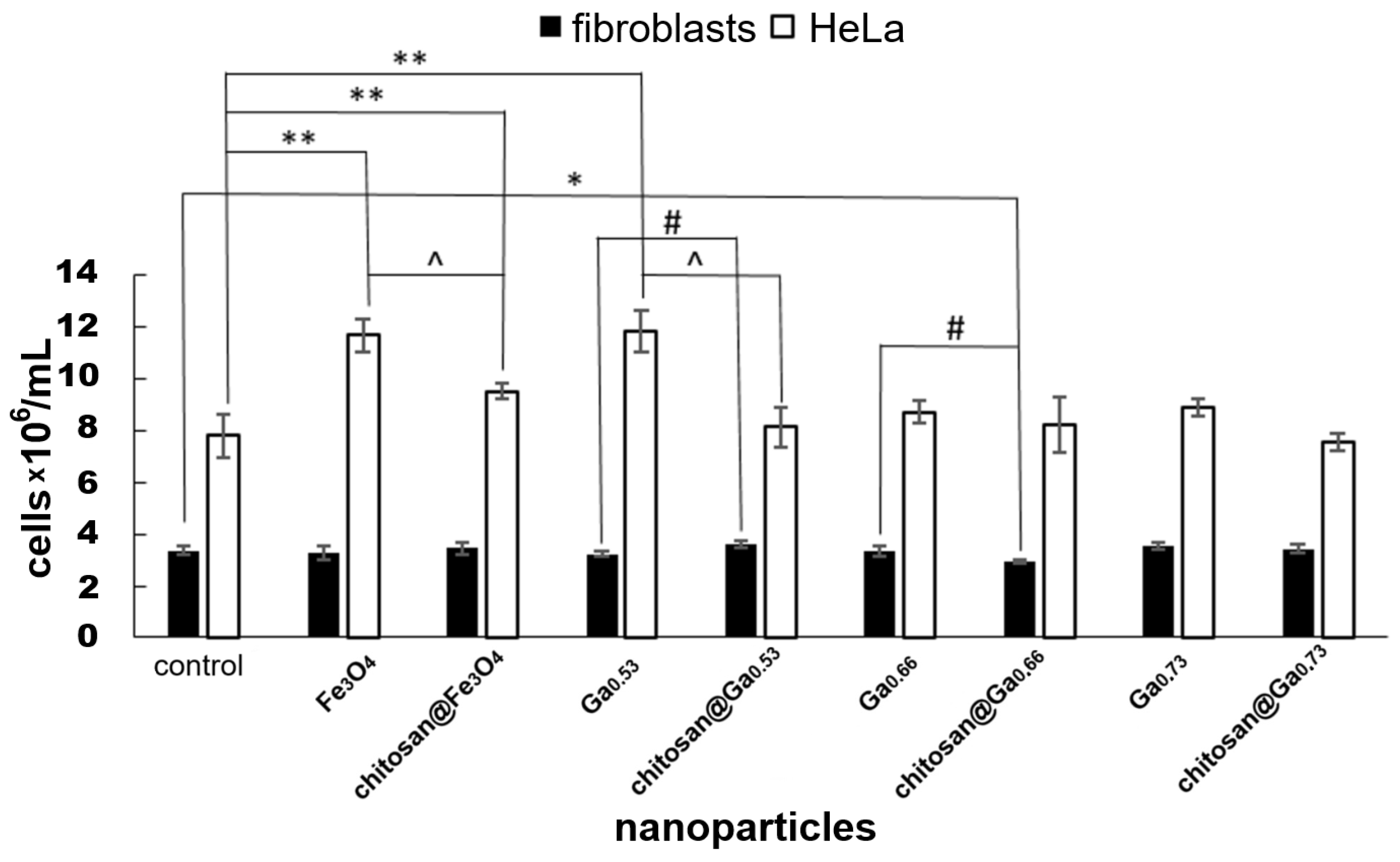

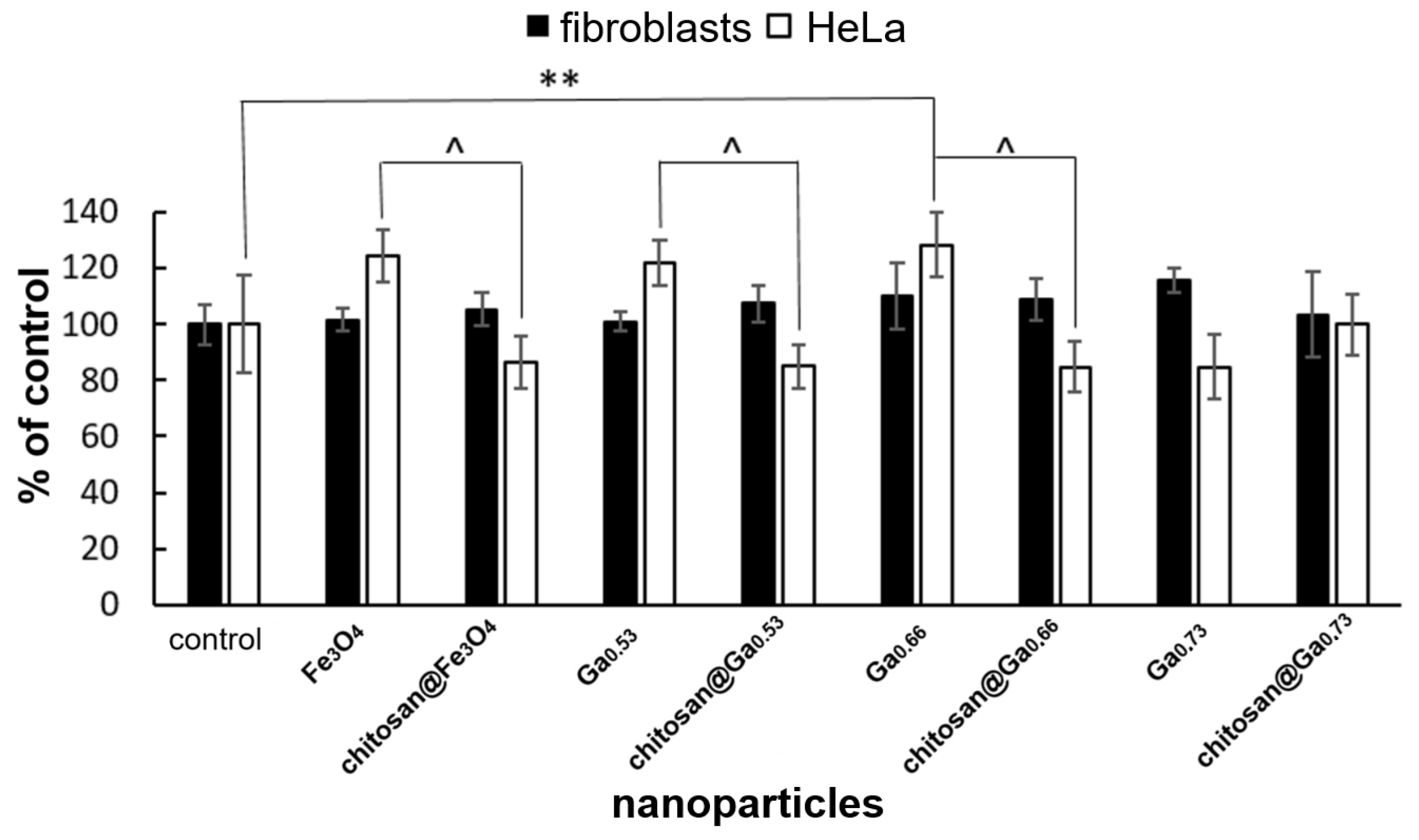

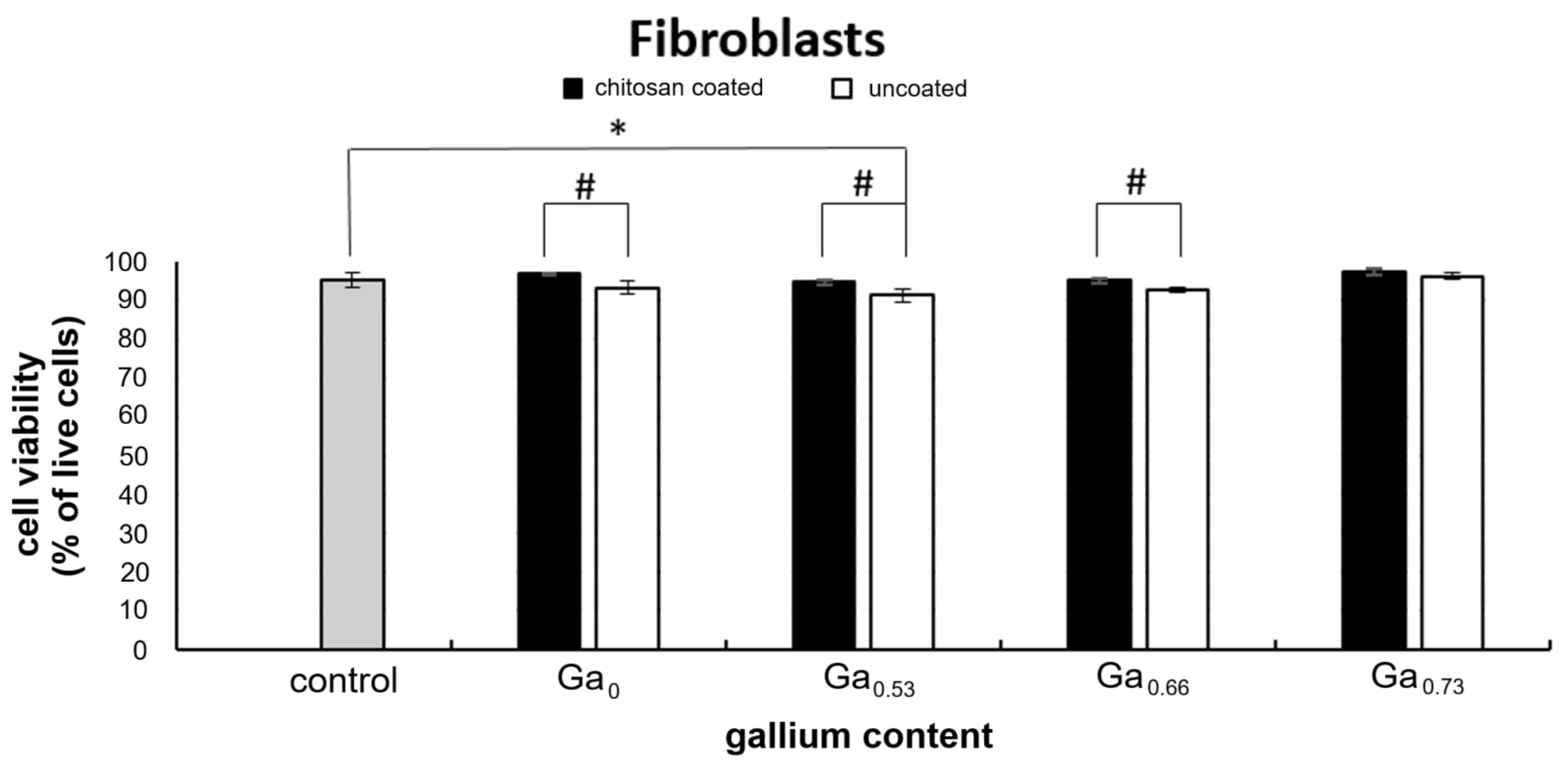

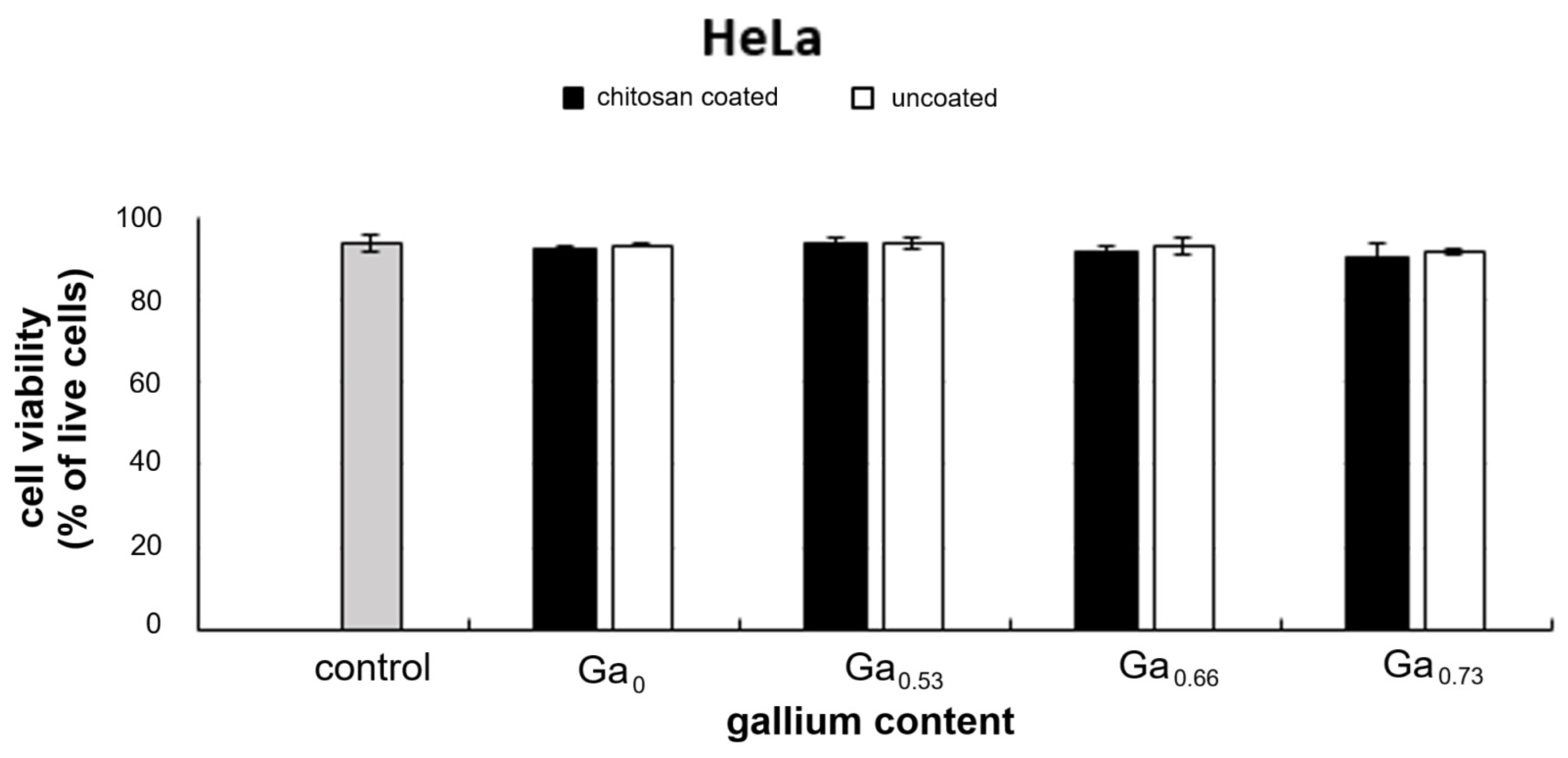

2.6. In Vitro Cytotoxicity Assessment

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. X-Ray Diffraction

4.2. Transmission Electron Microscopy Images

4.3. Small-Angle Neutron Scattering Measurements

4.4. Small-Angle X-Ray Scattering Analysis

4.5. Characterization of the Specific Absorption Rate

4.6. In Vitro Cytotoxicity Assessment

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Altammar, K.A. A Review on Nanoparticles: Characteristics, Synthesis, Applications, and Challenges. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1155622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joudeh, N.; Linke, D. Nanoparticle Classification, Physicochemical Properties, Characterization, and Applications: A Comprehensive Review for Biologists. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2022, 20, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stiufiuc, G.F.; Stiufiuc, R.I. Magnetic Nanoparticles: Synthesis, Characterization, and Their Use in Biomedical Field. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, M.D.; Nguyen, T.T.; Do, T.N.; Tran, H.V. Fe3O4 Nanoparticles: Structures, Synthesis, Magnetic Properties, Surface Functionalization, and Emerging Applications. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 11301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsubara, N.; Tsuchida, S.; Yamada, R.; Takahashi, Y.; Sakurai, H. Cation Distributions and Magnetic Properties of Ferrispinel MgFeMnO4. Inorg. Chem. 2020, 59, 17970–17980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sickafus, K.E.; Wills, J.M.; Grimes, N.W. Structure of Spinel. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 1999, 82, 3279–3292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleet, M.E. The Structure of Magnetite. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. B Struct. Crystallogr. Cryst. Chem. 1981, 37, 917–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baričić, M.; Uhrecký, R.; Mičetić, M.; Dražić, G.; Jagličić, Z.; Drofenik, M. Chemical Engineering of Cationic Distribution in Spinel Ferrite Nanoparticles: The Effect on the Magnetic Properties. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2024, 26, 6325–6334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganapathe, L.S.; Mohamed, M.S.; Alhaji, N.M.; Mohd Zuhri, M.R.; Othman, M.H.; Saheed, M.S.M. Magnetite (Fe3O4) Nanoparticles in Biomedical Application: From Synthesis to Surface Functionalisation. Magnetochemistry 2020, 6, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rećko, K.; Klekotka, U.; Kalska-Szostko, B.; Soloviov, D.; Satuła, D.; Waliszewski, J. Properties of Ga-Doped Magnetite Nanoparticles. Acta Phys. Pol. A 2018, 134, 998–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkes, L.M.; Hodgson, R.; Lu, L.T.; Tung, L.D.; Robinson, I.; Fernig, D.G.; Thanh, N.T. Cobalt Nanoparticles as a Novel Magnetic Resonance Contrast Agent—Relaxivities at 1.5 and 3 Tesla. Contrast Media Mol. Imaging 2008, 3, 150–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umut, E.; Coşkun, M.; Pineider, F.; Berti, D.; Güngüneş, H. Nickel Ferrite Nanoparticles for Simultaneous Use in Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Magnetic Fluid Hyperthermia. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2019, 550, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kusigerski, V.; Illes, E.; Blanusa, J.; Gyergyek, S.; Boskovic, M.; Perovic, M.; Spasojevic, V. Magnetic Properties and Heating Efficacy of Magnesium Doped Magnetite Nanoparticles Obtained by Co-Precipitation Method. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2019, 475, 470–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, B.D.; Rio, I.S.; Rodrigues, A.R.O.; Fernandes, F.C.; Almeida, B.G.; Pires, A.; Coutinho, P.J. Magnetoliposomes Containing Magnesium Ferrite Nanoparticles as Nanocarriers for the Model Drug Curcumin. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2018, 5, 181017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akhlaghi, N.; Najafpour-Darzi, G. Manganese Ferrite (MnFe2O4) Nanoparticles: From Synthesis to Application—A Review. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2021, 103, 292–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galarreta-Rodriguez, I.; Marcano, L.; Castellanos-Rubio, I.; de Muro, I.G.; García, I.; Olivi, L.; Insausti, M. Towards the Design of Contrast-Enhanced Agents: Systematic Ga3+ Doping on Magnetite Nanoparticles. Dalton Trans. 2022, 51, 2517–2530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Lu, J.; Cui, D.; Yan, F.X.; Yin, D.; Li, Y. Mechanical Characteristics of FeAl2O4 and AlFe2O4 Spinel Phases in Coatings—A Study Combining Experimental Evaluation and First-Principles Calculations. Ceram. Int. 2017, 43, 16094–16100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, W.; Nakagawa, T.; Kawaguchi, Y.; Kato, T.; Matsuda, T.; Kobayashi, T.; Suzuki, T. Microscopic Probing of the Doping Effects of In Ions in Fe3O4. J. Appl. Phys. 2022, 132, 083904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornak, J. Synthesis, Properties, and Selected Technical Applications of Magnesium Oxide Nanoparticles: A Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 12752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Qi, M.; Cheng, S.; Li, C.; Dong, B.; Wang, L. Gallium and Gallium Compounds: New Insights into the “Trojan Horse” Strategy in Medical Applications. Mater. Des. 2023, 227, 111704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazi, R.; Ahmadian, E.; Ahmadian-Yazdi, A.; Akbarzadeh Khiavi, M.; Moradi, M.; Ebrahimnejad, P. Iron Oxide Based Magnetic Nanoparticles for Hyperthermia, MRI and Drug Delivery Applications: A Review. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 11587–11616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panigrahi, L.L.; Mohapatra, S.; Rout, J.; Sahoo, S.; Jena, P.; Sahu, S.N.; Sahu, S.; Mishra, A. Adsorption of Antimicrobial Peptide onto Chitosan-Coated Iron Oxide Nanoparticles Fosters Oxidative Stress Triggering Bacterial Cell Death. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 25497–25507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patil, S.A.; Shinde, S.S.; Bandgar, S.S.; Koli, V.B.; Shaikh, S.P.; Inamdar, A.I. Manganese Iron Oxide Nanoparticles for Magnetic Hyperthermia, Antibacterial and ROS Generation Performance. J. Clust. Sci. 2024, 35, 1405–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nehra, P.; Chauhan, R.P.; Garg, N.; Verma, K. Antibacterial and Antifungal Activity of Chitosan Coated Iron Oxide Nanoparticles. Br. J. Biomed. Sci. 2018, 75, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radwan, M.A.; Rashad, M.A.; Sadek, M.A.; Elazab, H.A. Synthesis, Characterization and Selected Application of Chitosan-Coated Magnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticles. J. Chem. Technol. Metall. 2019, 54, 303–310. [Google Scholar]

- El-Kharrag, R.; Abdel Halim, S.S.; Amin, A.; Greish, Y.E. Synthesis and Characterization of Chitosan-Coated Magnetite Nanoparticles Using a Modified Wet Method for Drug Delivery Applications. Int. J. Polym. Mater. Polym. Biomater. 2019, 68, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khmara, I.; Strbak, O.; Zavisova, V.; Koneracka, M.; Kubovcikova, M.; Antal, I.; Kavecansky, V.; Lucanska, D.; Dobrota, D.; Kopcansky, P. Chitosan-Stabilized Iron Oxide Nanoparticles for Magnetic Resonance Imaging. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2019, 474, 319–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Zafar, H.; Zia, M.; Ul Haq, I.; Phull, A.R.; Ali, J.S.; Hussain, A. Synthesis, Characterization, Applications, and Challenges of Iron Oxide Nanoparticles. Nanotechnol. Sci. Appl. 2016, 9, 49–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pool, V.L.; Klem, M.T.; Chorney, C.L.; Arenholz, E.A.; Idzerda, Y.U. Enhanced Magnetism of Fe3O4 Nanoparticles with Ga Doping. J. Appl. Phys. 2011, 109, 07B529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostikas, A.; Simopoulos, A.; Gangas, N.H.J. Effective Field Distribution in Gallium-Substituted Ferrites. Phys. Status Solidi (b) 1970, 42, 705–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oleś, A. Étude du Système Ga2O3-FeO—Fe2O3-FeO par Diffraction de Neutrons. Acta Phys. Pol. 1966, 30, 125–134. [Google Scholar]

- Repetto, G.; del Peso, A. Gallium, Indium, and Thallium. In Patty’s Toxicology, 6th ed.; John Wiley and Sons Ltd.: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 257–354. [Google Scholar]

- Standing Committee on the Scientific Evaluation of Dietary Reference Intakes; Subcommittee of Interpretation and Uses of Dietary Reference Intakes; Subcommittee on Upper Reference Levels of Nutrients; Panel on Micronutrients. Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin A, Vitamin K, Arsenic, Boron, Chromium, Copper, Iodine, Iron, Manganese, Molybdenum, Nickel, Silicon, Vanadium, and Zinc; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Orzechowska, M.; Rećko, K.; Klekotka, U.; Czerniecka, M.; Tylicki, A.; Satuła, D.; Kalska-Szostko, B. Structural and Thermomagnetic Properties of Gallium Nanoferrites and Their Influence on Cells In Vitro. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 14184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitambar, C.R. Medical Applications and Toxicities of Gallium Compounds. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2010, 7, 2337–2361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salvarese, N.; Morellato, N.; Gobbi, C.; Gandin, V.; De Franco, M.; Marzano, C.; Bolzati, C. Synthesis, Characterization and In Vitro Cytotoxicity of Gallium(III)-Dithiocarbamate Complexes. Dalton Trans. 2024, 53, 4526–4543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melnikov, P.; Matos, M.D.F.C.; Malzac, A.; Teixeira, A.R.; de Albuquerque, D.M. Evaluation of in Vitro Toxicity of Hydroxyapatite Doped with Gallium. Mater. Lett. 2019, 253, 343–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flora, S.J. Possible Health Hazards Associated with the Use of Toxic Metals in Semiconductor Industries. J. Occup. Health 2000, 42, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthing, T.; Lard, M.; Danielsen, P.H.; Abariute, L.; Barfod, K.K.; Adolfsson, K.; Knudsen, K.B.; Wolff, H.; Prinz, C.N.; Vogel, U. Pulmonary Toxicity and Translocation of Gallium Phosphide Nanowires to Secondary Organs Following Pulmonary Exposure in Mice. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2023, 21, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, A. Toxicity of Indium Arsenide, Gallium Arsenide, and Aluminium Gallium Arsenide. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2004, 198, 405–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onikura, N.; Nakamura, A.; Kishi, K. Acute Toxicity of Gallium and Effects of Salinity on Gallium Toxicity to Brackish and Marine Organisms. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2005, 75, 356–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.-L. Comparative Acute Toxicity of Gallium(III), Antimony(III), Indium(III), Cadmium(II), and Copper(II) on Freshwater Swamp Shrimp (Macrobrachium nipponense). Biol. Res. 2014, 47, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trenfield, M.A.; van Dam, J.W.; Harford, A.J.; Parry, D.; Streten, C.; Gibb, K.; van Dam, R.A. Aluminium, Gallium, and Molybdenum Toxicity to the Tropical Marine Microalga Isochrysis galbana. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2015, 34, 1833–1840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, J.K.; Kim, J.C.; Shin, Y.; Han, S.M.; Won, W.R.; Her, J.; Oh, K.T. Principles and Applications of Nanomaterial-Based Hyperthermia in Cancer Therapy. Arch. Pharmacal Res. 2020, 43, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedayatnasab, Z.; Abnisa, F.; Daud, W.M.A.W. Review on Magnetic Nanoparticles for Magnetic Nanofluid Hyperthermia Application. Mater. Des. 2017, 123, 174–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miaskowski, A. Magnetic Fluid Hyperthermia Treatment Planning Correlated with Calorimetric Measurements Under Non-Adiabatic Conditions; Towarzystwo Wydawnictw Naukowych Libropolis: Lublin, Poland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, C.; Gao, W.; Chen, Z.; Fan, H.; Li, M.; Deng, F.; Chen, Z. Tumor Selectivity of Stealth Multi-Functionalized Superparamagnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticles. Int. J. Pharm. 2011, 404, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemal, P.; Balog, S.; Geers, C.; Taladriz-Blanco, P.; Palumbo, A.; Hirt, A.M.; Petri-Fink, A. Heating Behavior of Magnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticles at Clinically Relevant Concentration. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2019, 474, 637–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozissnik, B.; Bohorquez, A.C.; Dobson, J.; Rinaldi, C. Magnetic Fluid Hyperthermia: Advances, Challenges, and Opportunity. Int. J. Hyperth. 2013, 29, 706–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiesen, B.; Jordan, A. Clinical Applications of Magnetic Nanoparticles for Hyperthermia. Int. J. Hyperth. 2008, 24, 467–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, A.; Scholz, R.; Wust, P.; Fähling, H.; Felix, R. Magnetic Fluid Hyperthermia (MFH): Cancer Treatment with AC Magnetic Field Induced Excitation of Biocompatible Superparamagnetic Nanoparticles. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 1999, 201, 413–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurent, S.; Forge, D.; Port, M.; Roch, A.; Robic, C.; Vander Elst, L.; Muller, R.N. Magnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticles: Synthesis, Stabilization, Vectorization, Physicochemical Characterizations, and Biological Applications. Chem. Rev. 2008, 108, 2064–2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdavi, M.; Ahmad, M.B.; Haron, M.J.; Namvar, F.; Nadi, B.; Rahman, M.Z.A.; Amin, J. Synthesis, Surface Modification and Characterization of Chitosan-Coated Magnetite Nanoparticles. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2013, 343, 213–217. [Google Scholar]

- Shibayama, M.; Tanaka, T.; Han, C.C. Small angle neutron scattering study on poly(N-isopropyl acrylamide) gels near their volume-phase transition temperature. J. Chem. Phys. 1992, 97, 6829–6841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mildner, D.F.R.; Hall, P.L. Small-angle scattering from porous solids with fractal geometry. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 1986, 19, 1535–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avdeev, M.V.; Tropin, T.V.; Aksenov, V.L.; Rosta, L.; Garamus, V.M.; Rozhkova, N.N. Pore structures in shungites as revealed by small-angle neutron scattering. Carbon 2006, 44, 954–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaucage, G. Approximations leading to a unified exponential/power-law approach to small-angle scattering. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 1995, 28, 717–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wildeboer, R.R.; Southern, P.; Pankhurst, Q.A. On the reliable measurement of specific absorption rates and intrinsic loss parameters in magnetic hyperthermia materials. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2014, 47, 495003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrick, P.S.; Stuckey, D.J.; Zhu, H.; Kalber, T.L.; Iftikhar, H.; Southern, P.; Pankhurst, Q.A. Improved tumour delivery of iron oxide nanoparticles for magnetic hyperthermia therapy of melanoma via ultrasound guidance and 111In SPECT quantification. Nanoscale 2024, 16, 19715–19729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drzewiński, A.; Marć, M.; Wolak, W.W.; Dudek, M.R. Effect of Magnetic Heating on Stability of Magnetic Colloids. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 3064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoshiar, A.K.; Le, T.A.; Amin, F.U.; Kim, M.O.; Yoon, J. Studies of aggregated nanoparticles steering during magnetic-guided drug delivery in the blood vessels. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2017, 427, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Włodarczyk, A.; Gorgoń, S.; Radoń, A.; Bajdak-Rusinek, K. Magnetite nanoparticles in magnetic hyperthermia and cancer therapies: Challenges and perspectives. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, A.; Pu, Y.; Xu, N.; Cai, Z.; Sun, R.; Fu, S.; Jin, R.; Guo, Y.; Ai, H.; Nie, Y.; et al. Controlled intracellular aggregation of magnetic particles improves permeation and retention for magnetic hyperthermia promotion and immune activation. Theranostics 2023, 13, 1454–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galarreta-Rodríguez, I.; Liguori, D.; Garaio, E.; Muzzi, B.; Cervera-Gabalda, L.; Rubio-Zuazo, J.; Gomide, G.; Depeyrot, J.; López-Ortega, A. Nanoscale Engineering of Cobalt–Gallium Co-Doped Ferrites: A Strategy to Enhance High-Frequency Theranostic Magnetic Materials. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2025, 8, 13817–13828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egizbek, K.; Kozlovskiy, A.L.; Ludzik, K.; Zdorovets, M.V.; Korolkov, I.V.; Marciniak, B.; Jazdzewska, M.; Chudoba, D.; Nazarova, A.; Kontek, R. Stability and Cytotoxicity Study of NiFe2O4 Nanocomposites Synthesized by Co-precipitation and Subsequent Thermal Annealing. Ceram. Int. 2020, 46, 16548–16555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abudayyak, M.; Altınçekic Gürkaynak, T.; Öznan, G. In Vitro Evaluation of the Toxicity of Cobalt Ferrite Nanoparticles in Kidney Cells. Turk. J. Pharm. Sci. 2017, 14, 169–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafi-Ahmadi, L.; Khademinia, S.; Najafzadeh Nansa, M.; Ali Alemi, A.; Mahdavi, M.; Poursattar Marjani, A. Co-precipitation Synthesis and Characterization of CoFe2O4 Nanomaterial and Evaluation of Its Toxicity on the Human Leukemia K562 Cell Line. J. Chil. Chem. Soc. 2020, 65, 4845–4848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanagesan, S.; Bin Ab Aziz, S.; Hashim, M.; Ismail, I.; Tamilselvan, S.; Alitheen, N.B.B.M.; Swamy, M.K.; Rao, B.P.C. Synthesis, Characterization and In Vitro Evaluation of Manganese Ferrite (MnFe2O4) Nanoparticles for Their Biocompatibility with Murine Breast Cancer Cells (4T1). Molecules 2016, 21, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, J.; Alhadlaq, H.A.; Alshamsan, A.; Siddiqui, M.A.; Saquib, Q.; Khan, S.T.; Wahab, R.; Al-Khedhairy, A.A.; Musarrat, J.; Akhtar, M.J.; et al. Differential Cytotoxicity of Copper Ferrite Nanoparticles in Different Human Cells. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2016, 36, 1284–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massart, R. Preparation of aqueous magnetic liquids in alkaline and acidic media. IEEE Trans. Magn. 1981, 17, 1247–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, R.K.; Chattopadhyaya, M.C. Nanomaterials for Wastewater Remediation. MRS Bull. 2017, 42, 685–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, K.; Li, P.; Zhu, H.; Zhou, Y.; Ding, J.; Shen, J.; Chu, P.K. Recent advances in multifunctional magnetic nanoparticles and applications to biomedical diagnosis and treatment. RSC Adv. 2013, 3, 10598–10618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, S.A.M.K.; Ficiarà, E.; Ruffinatti, F.A.; Stura, I.; Argenziano, M.; Abollino, O.; D’Agata, F. Magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles: Synthesis, characterization and functionalization for biomedical applications in the central nervous system. Materials 2019, 12, 465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arias, L.S.; Pessan, J.P.; Vieira, A.P.M.; Lima, T.M.T.D.; Delbem, A.C.B.; Monteiro, D.R. Iron oxide nanoparticles for biomedical applications: A perspective on synthesis, drugs, antimicrobial activity, and toxicity. Antibiotics 2018, 7, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, L.A.; Onzi, G.R.; Morawski, A.S.; Pohlmann, A.R.; Guterres, S.S.; Contri, R.V. Chitosan as a coating material for nanoparticles intended for biomedical applications. React. Funct. Polym. 2020, 147, 104459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, N.; Ji, H.; Yu, P.; Niu, J.; Farooq, M.U.; Akram, M.W.; Niu, X. Surface Modification of Magnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticles. Nanomaterials 2018, 8, 810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Carvajal, J. FullProf2000; Version 3.2; Laboratoire Léon Brillouin: Saclay, France, 1997; pp. 20–22. [Google Scholar]

- Bergerhoff, G.; Hundt, R.; Sievers, R.; Brown, I.D. The Inorganic Crystal Structure Data Base. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 1983, 23, 66–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degen, T.; Sadki, M.; Bron, E.; König, U.; Nénert, G. The HighScore Suite. Powder Diffr. 2014, 29, S13–S18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A. Handbook of SAS® DATA Step Programming; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Strober, W. Trypan Blue Exclusion Test of Cell Viability. Curr. Protoc. Immunol. 2015, 111, A3.B.1–A3.B.3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosmann, T. Rapid Colorimetric Assay for Cellular Growth and Survival: Application to Proliferation and Cytotoxicity Assays. J. Immunol. Methods 1983, 65, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample Without Chitosan | Nanoparticle Size [nm] | Sample with Chitosan | Nanoparticle Size [nm] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fe3O4 | 8.87 ± 0.16 | 1.5 | Fe3O4 | 9.36 ± 0.18 | 1.1 |

| Ga0.065 | 10.25 ± 0.10 | 1.4 | Ga0.065 | 10.28 ± 0.12 | 1.8 |

| Ga0.13 | 13.50 ± 0.11 | 4.7 | Ga0.13 | 10.56 ± 0.13 | 1.6 |

| Ga0.2 | 12.71 ± 0.11 | 4.4 | Ga0.2 | 10.68 ± 0.11 | 2.0 |

| Ga0.26 | 11.64 ± 0.20 | 1.6 | Ga0.26 | 10.32 ± 0.17 | 2.1 |

| Ga0.33 | 10.89 ± 0.13 | 1.6 | Ga0.33 | 10.36 ± 0.22 | 2.2 |

| Ga0.4 | 11.20 ± 0.17 | 1.4 | Ga0.4 | 10.27 ± 0.12 | 2.5 |

| Ga0.46 | 10.67 ± 0.15 | 1.4 | Ga0.46 | 10.37 ± 0.20 | 1.4 |

| Ga0.53 | 10.48 ± 0.18 | 1.7 | Ga0.53 | 10.47 ± 0.12 | 1.9 |

| Ga0.6 | 11.11 ± 0.13 | 1.8 | Ga0.6 | 11.40 ± 0.12 | 2.7 |

| Ga0.66 | 10.20 ± 0.16 | 1.1 | Ga0.66 | 9.60 ± 0.13 | 1.4 |

| Ga0.73 | 8.86 ± 0.12 | 1.4 | Ga0.73 | 10.17 ± 0.20 | 2.3 |

| Ga0.8 | 10.32 ± 0.18 | 1.4 | |||

| Ga0.86 | 10.49 ± 0.16 | 1.2 | |||

| Ga0.92 | 10.02 ± 0.13 | 1.4 | |||

| Ga1.0 | 10.14 ± 0.12 | 1.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Orzechowska, M.; Klekotka, U.; Czerniecka, M.; Tylicki, A.; Soloviov, D.; Miaskowski, A.; Rećko, K. Biomedical Applications of Chitosan-Coated Gallium Iron Oxide Nanoparticles GaxFe(3−x)O4 with 0 ≤ x ≤ 1 for Magnetic Hyperthermia. Molecules 2026, 31, 177. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010177

Orzechowska M, Klekotka U, Czerniecka M, Tylicki A, Soloviov D, Miaskowski A, Rećko K. Biomedical Applications of Chitosan-Coated Gallium Iron Oxide Nanoparticles GaxFe(3−x)O4 with 0 ≤ x ≤ 1 for Magnetic Hyperthermia. Molecules. 2026; 31(1):177. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010177

Chicago/Turabian StyleOrzechowska, Marta, Urszula Klekotka, Magdalena Czerniecka, Adam Tylicki, Dmytro Soloviov, Arkadiusz Miaskowski, and Katarzyna Rećko. 2026. "Biomedical Applications of Chitosan-Coated Gallium Iron Oxide Nanoparticles GaxFe(3−x)O4 with 0 ≤ x ≤ 1 for Magnetic Hyperthermia" Molecules 31, no. 1: 177. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010177

APA StyleOrzechowska, M., Klekotka, U., Czerniecka, M., Tylicki, A., Soloviov, D., Miaskowski, A., & Rećko, K. (2026). Biomedical Applications of Chitosan-Coated Gallium Iron Oxide Nanoparticles GaxFe(3−x)O4 with 0 ≤ x ≤ 1 for Magnetic Hyperthermia. Molecules, 31(1), 177. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010177