Effects of Radiation Reabsorption on the Flammability Limit and Critical Fuel Concentration of Methane Oxy-Fuel Diffusion Flame

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Methane–Air Counterflow Diffusion Flame

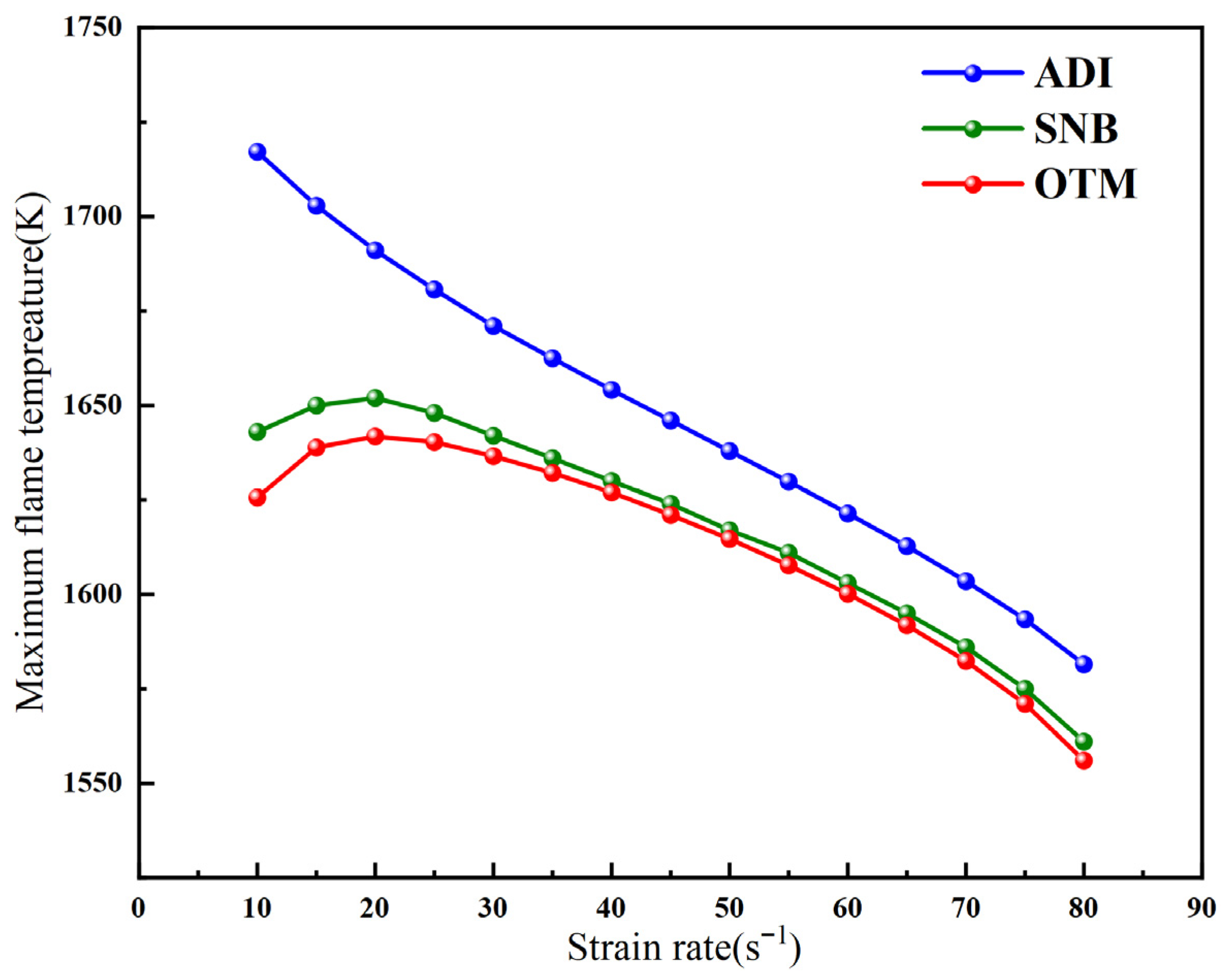

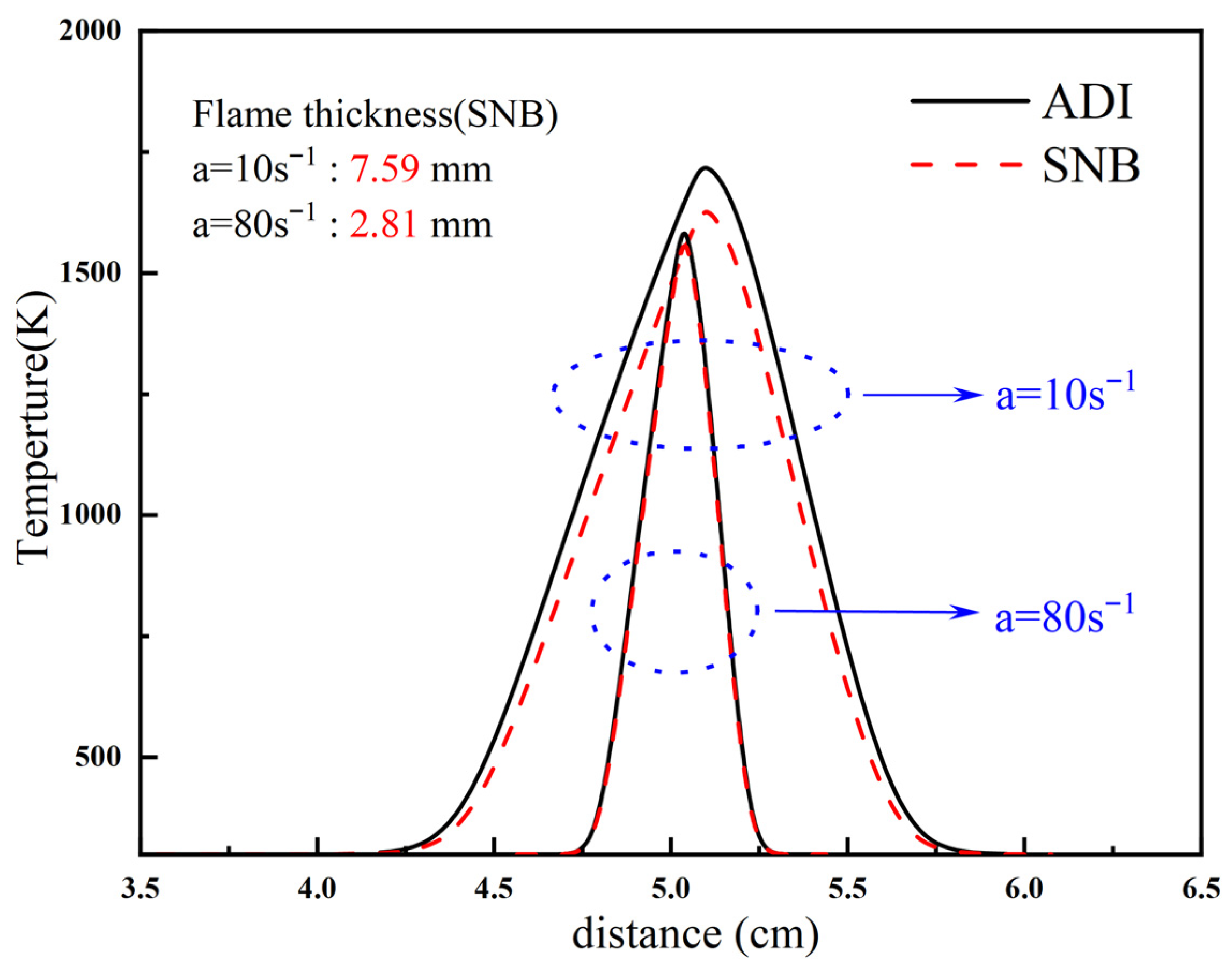

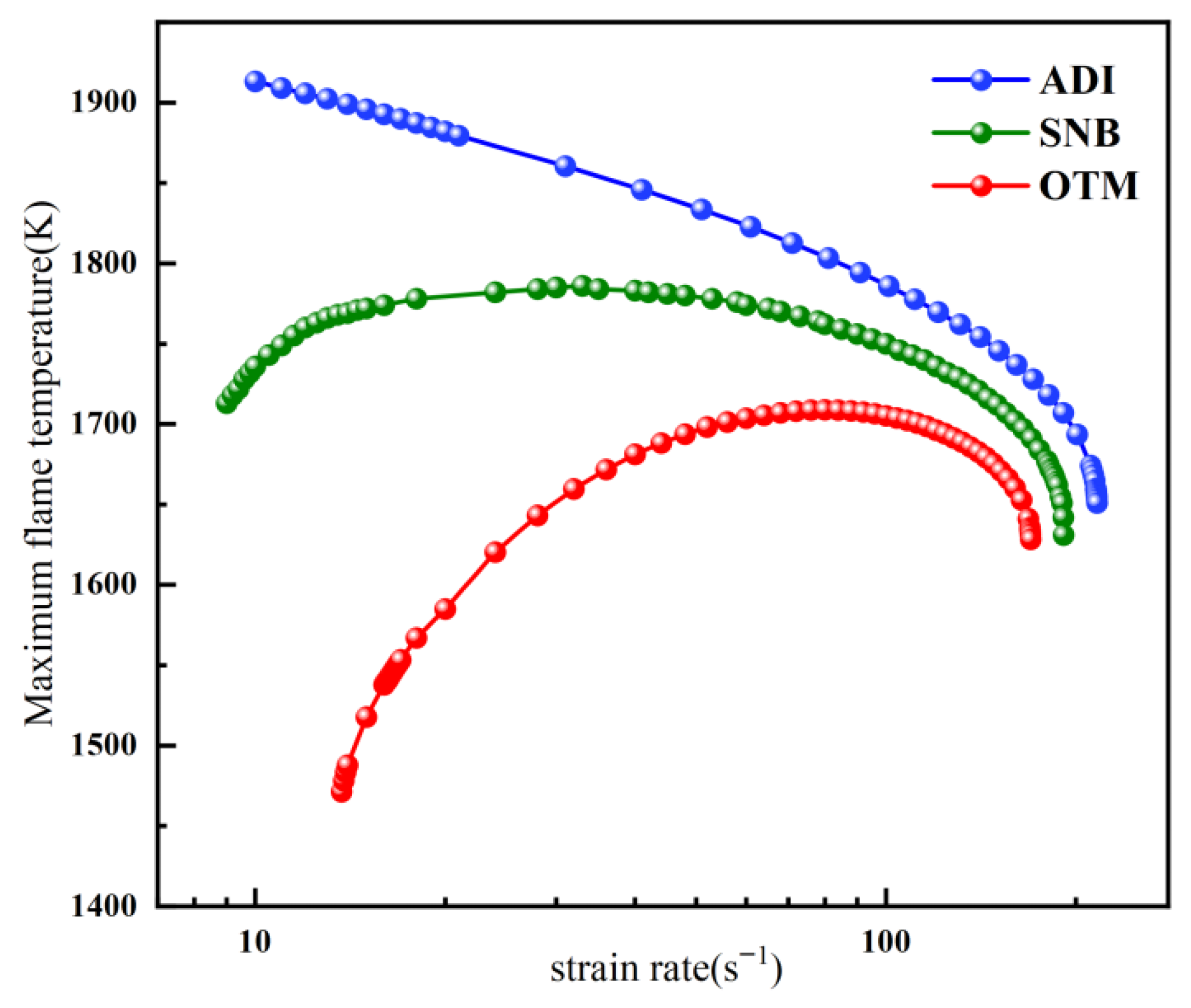

2.1.1. Overall Trends of Flame Temperature Versus Strain Rate Under Different Radiation Models

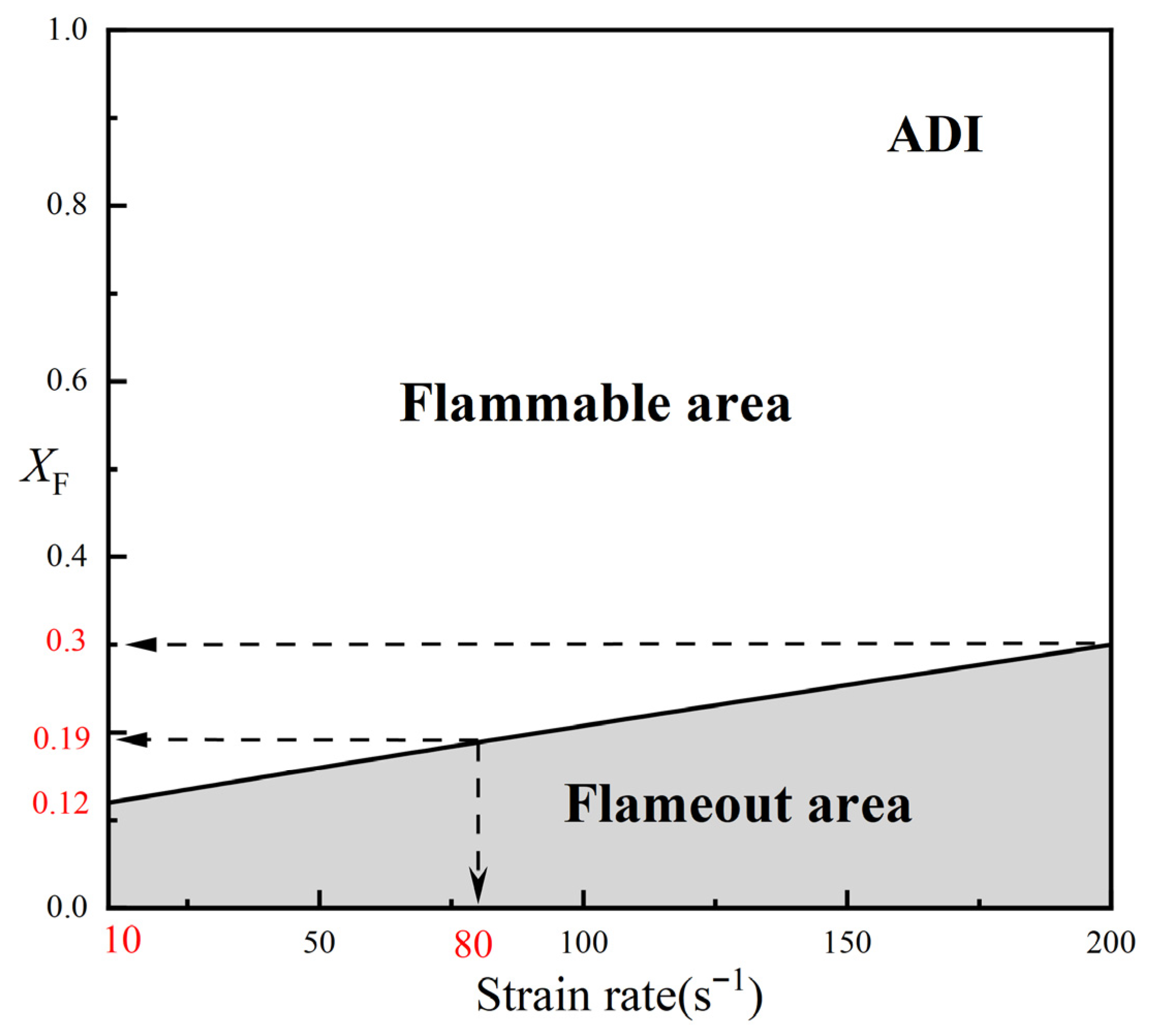

2.1.2. Critical Fuel Concentration and Flammable Area Under Different Radiation Models

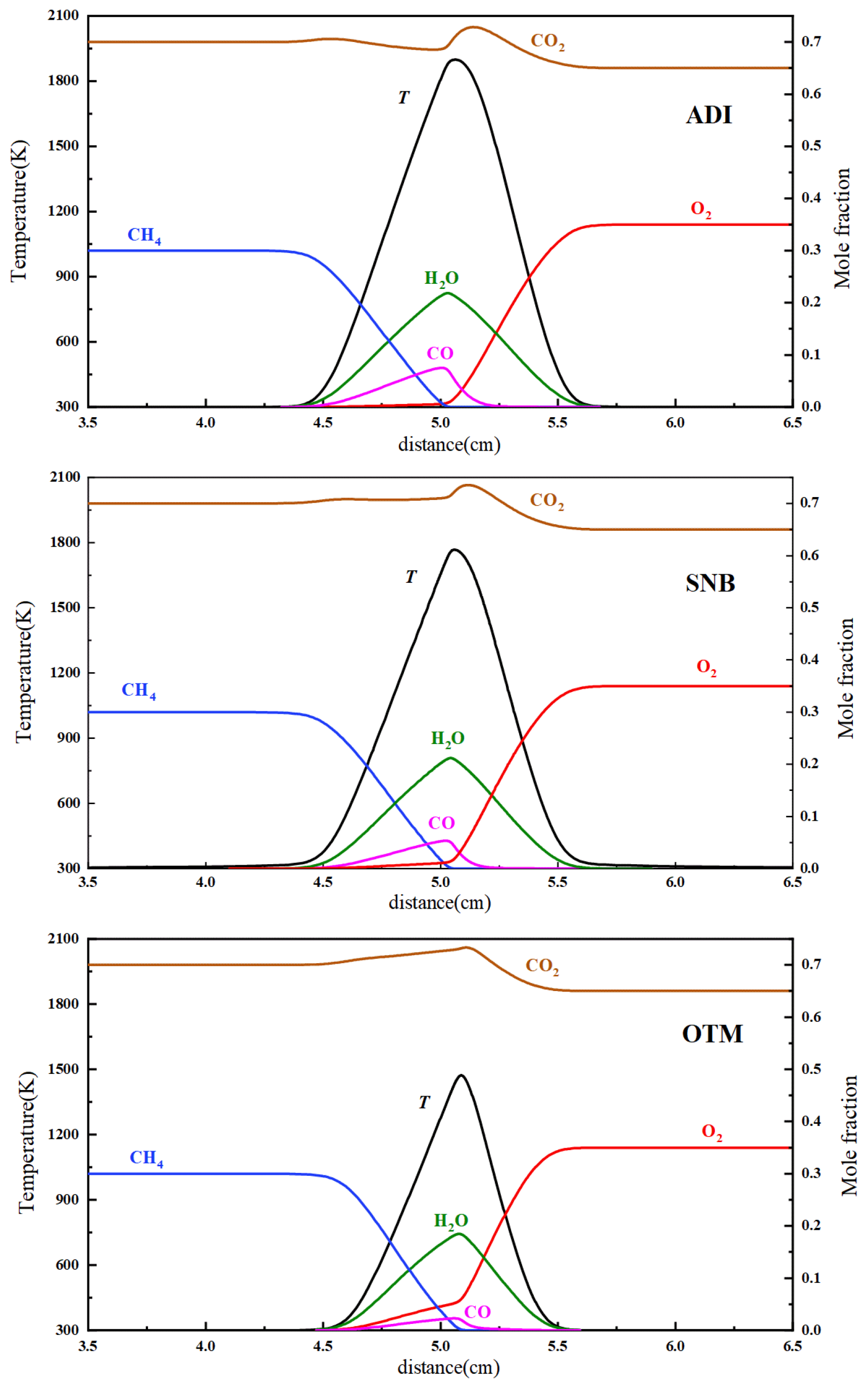

2.2. Methane Oxy-Fuel Counterflow Diffusion Flame

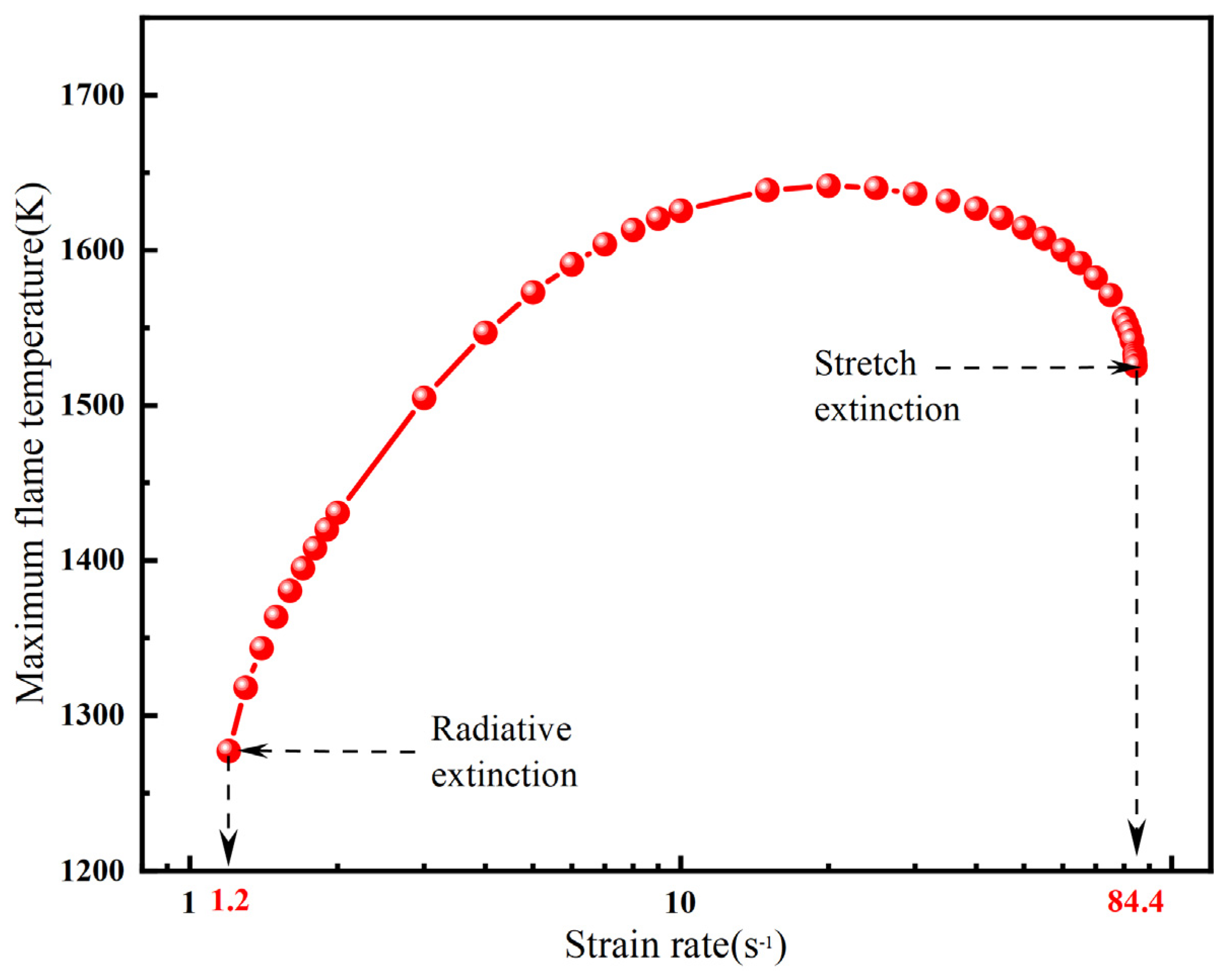

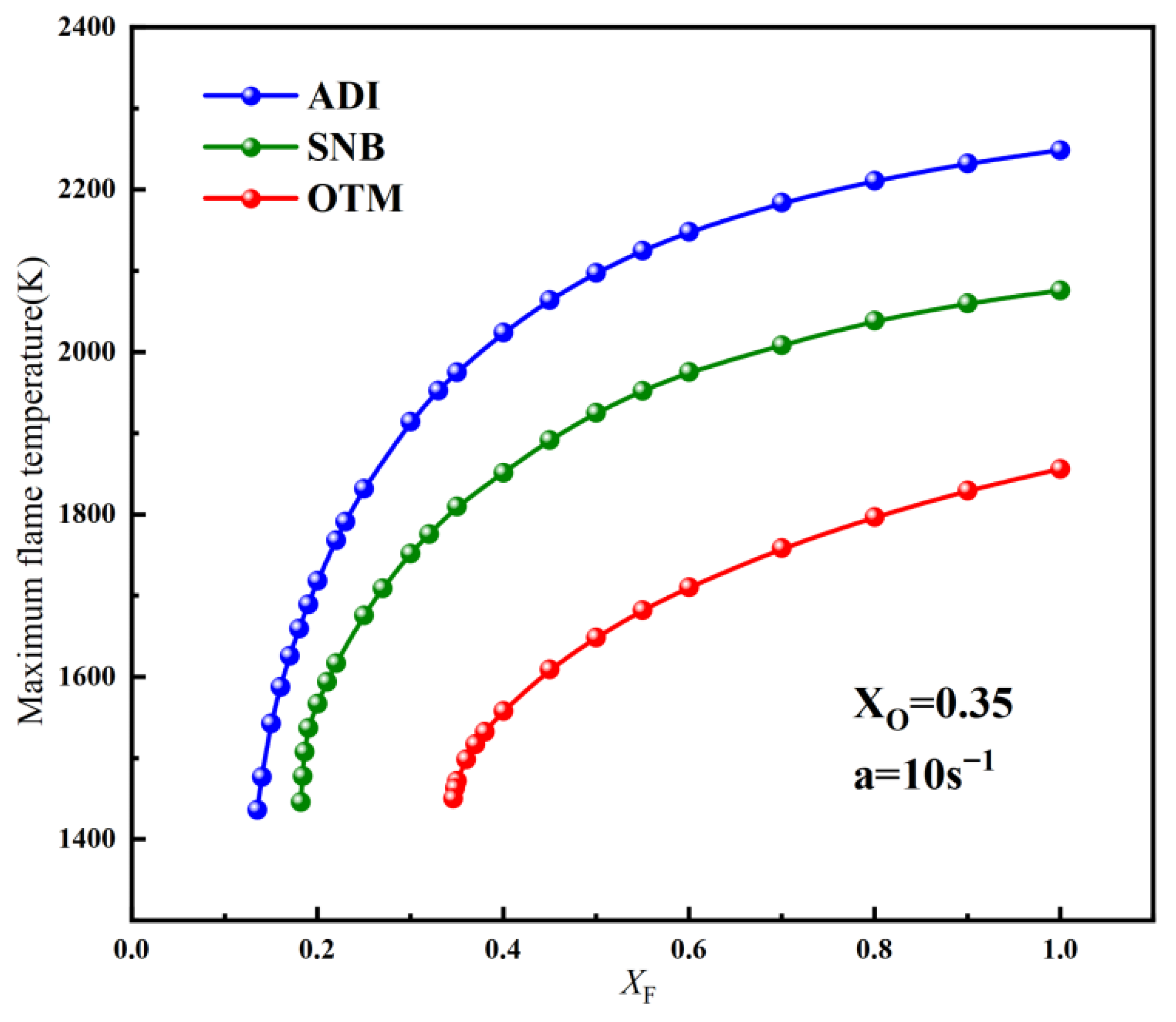

2.2.1. Overall Trends of Flame Temperature Versus Strain Rate Under Different Radiation Models

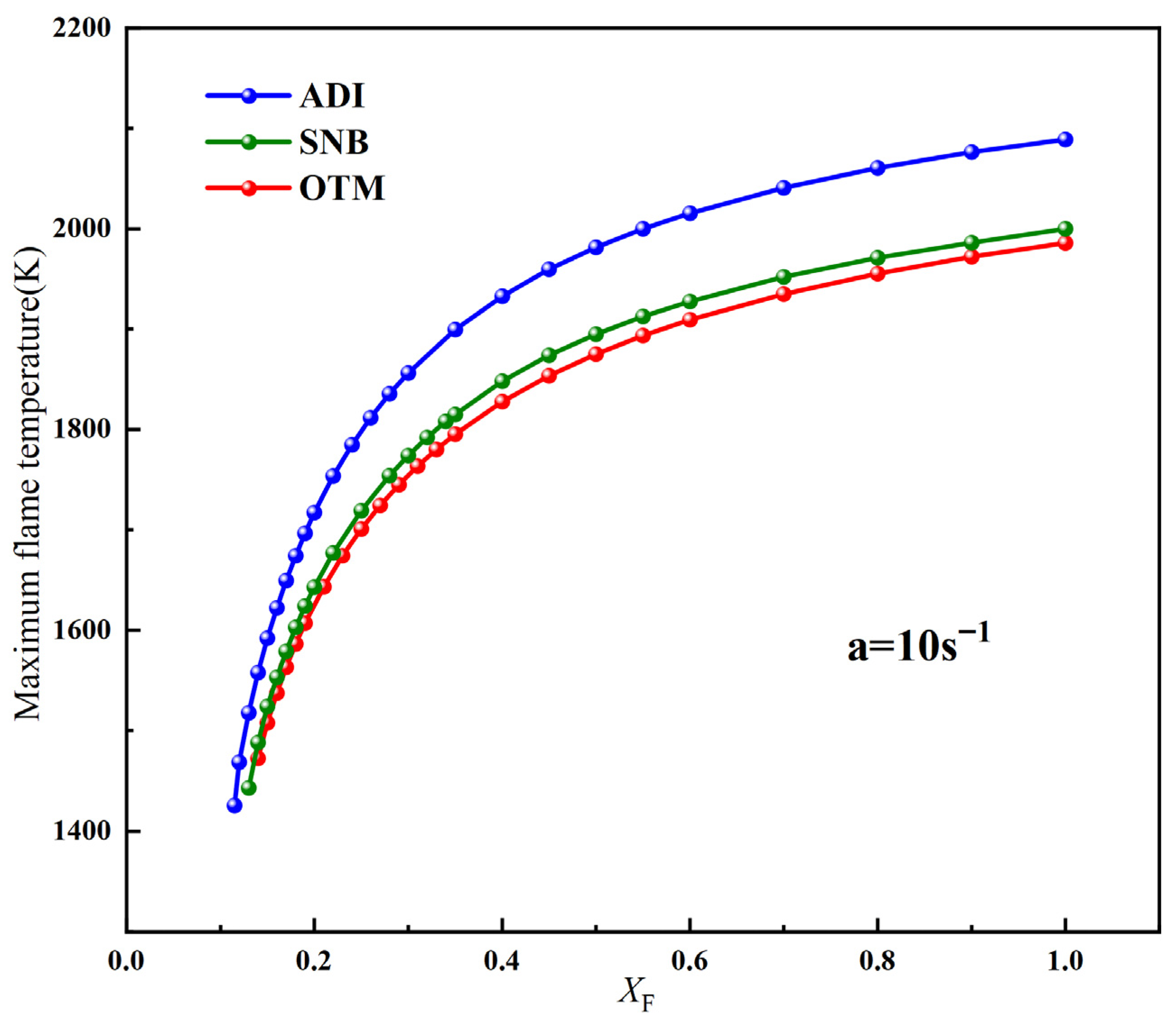

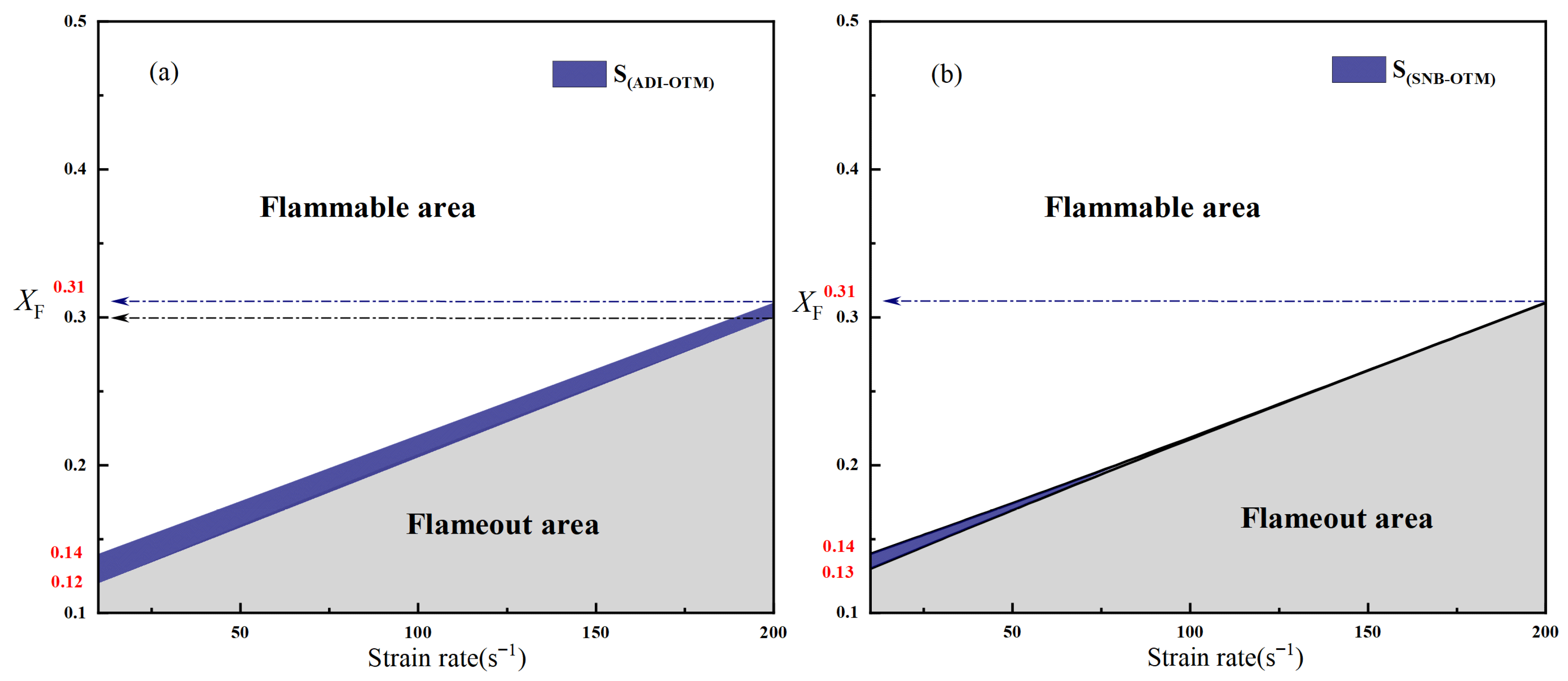

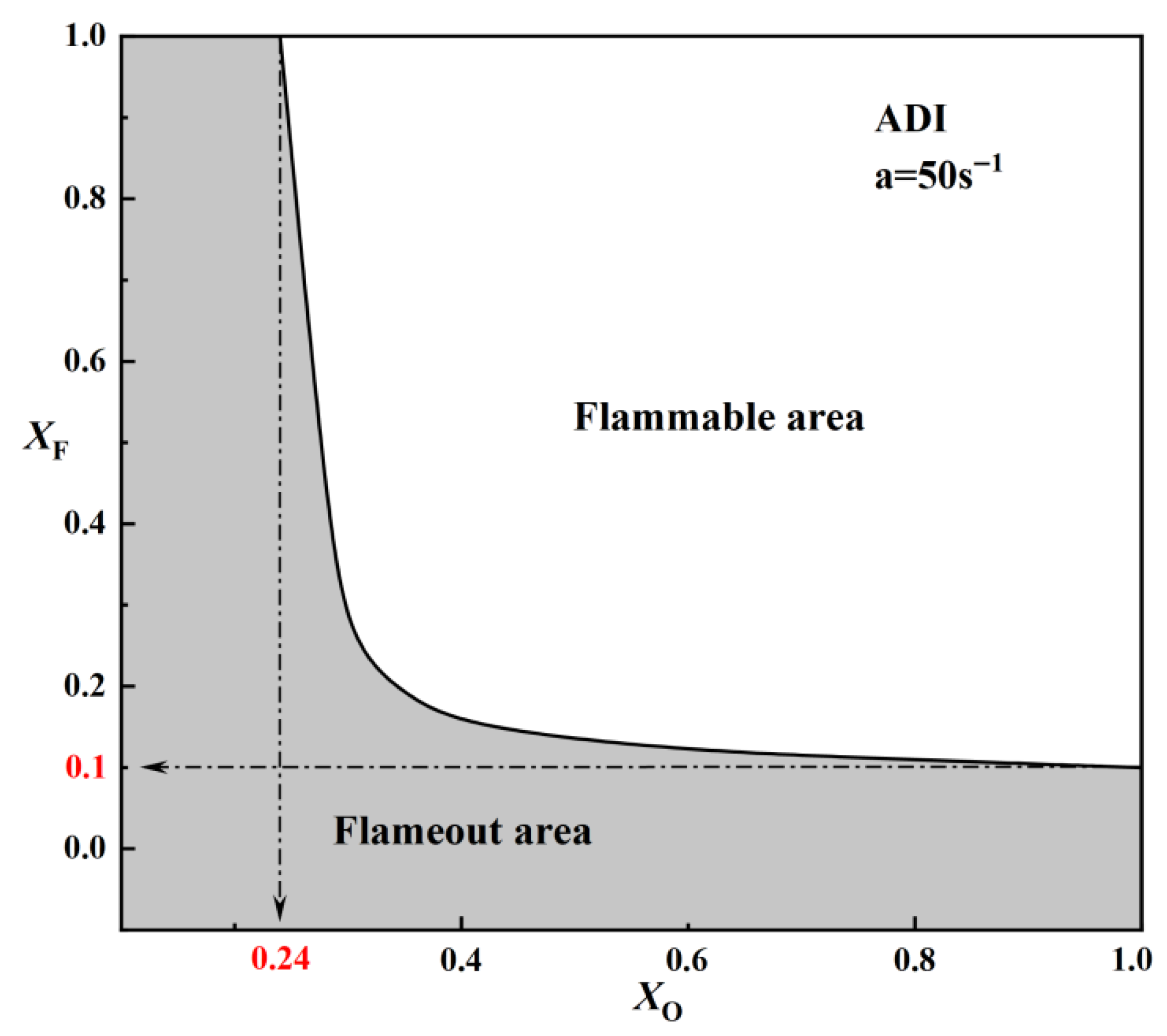

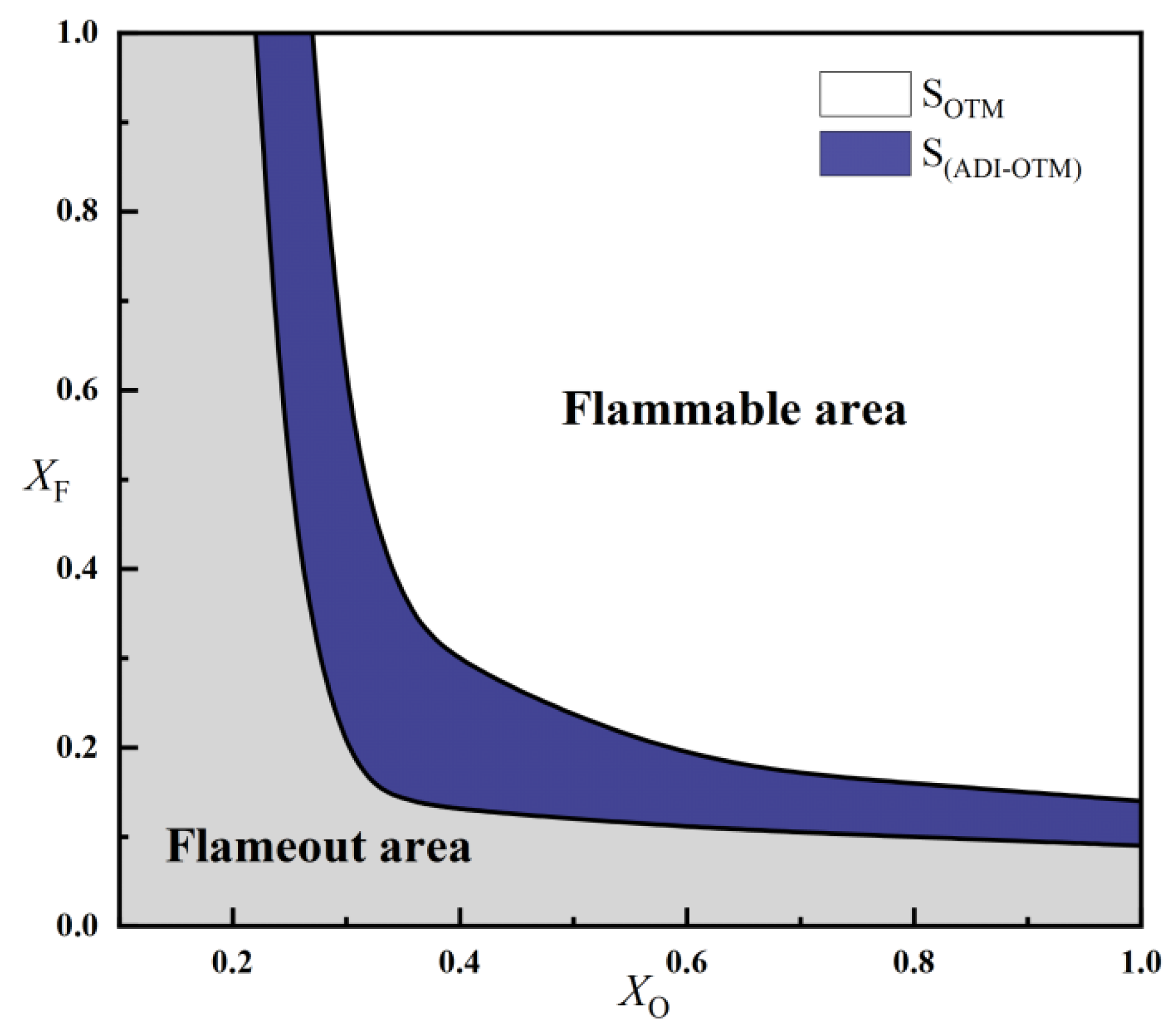

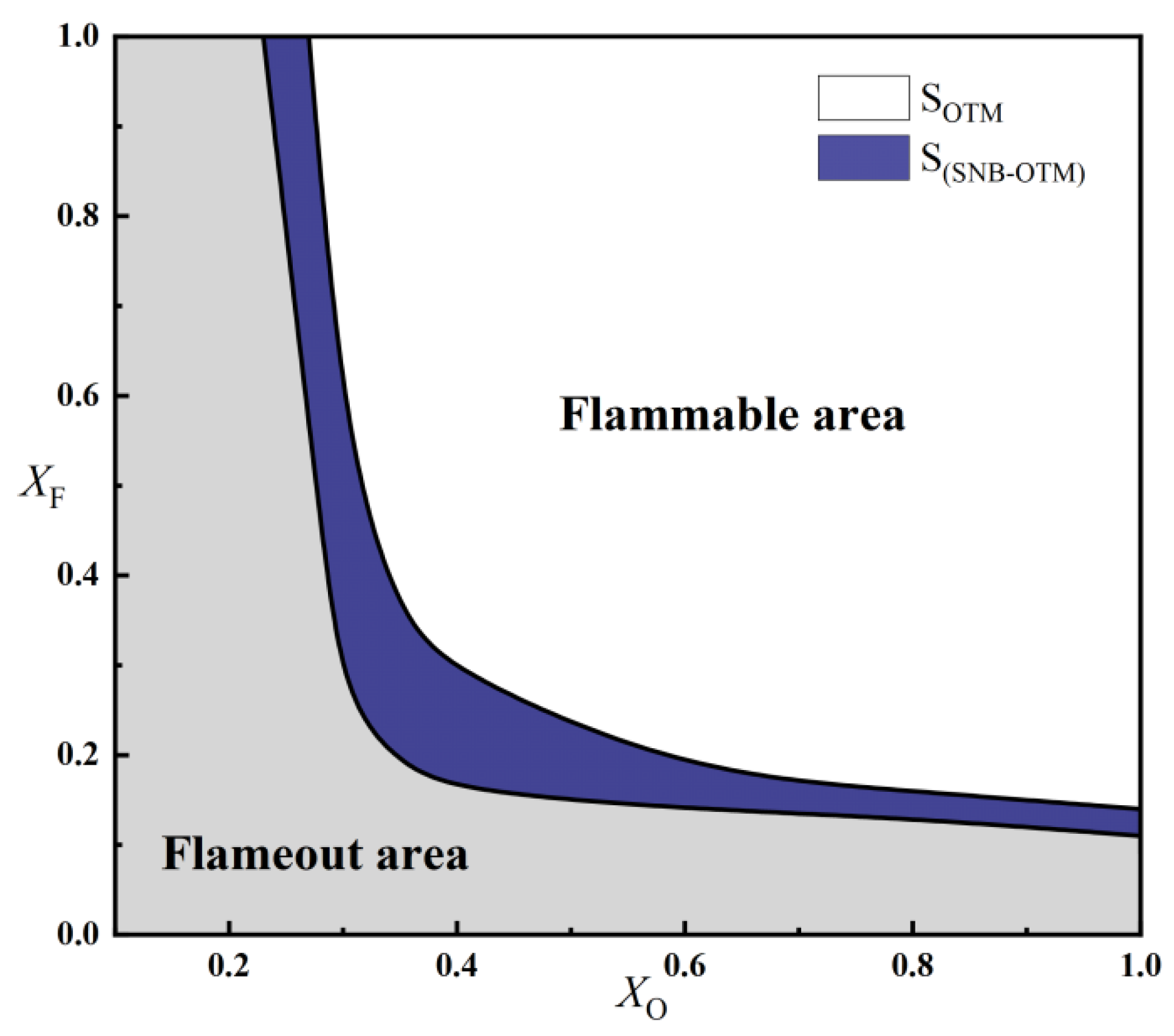

2.2.2. Critical Fuel Concentration and Flammable Regions Under Different Radiation Models

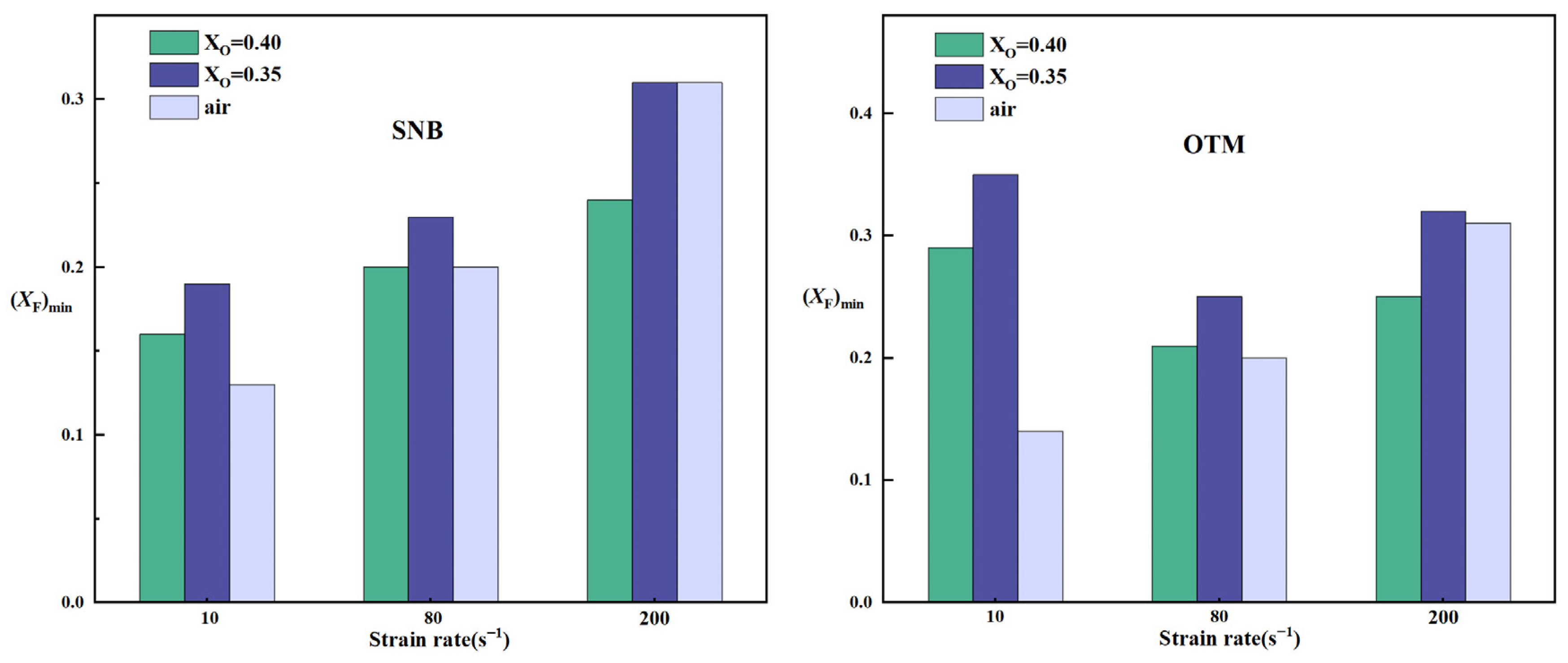

2.3. A Comparison of Critical Fuel Concentration Between Air Flames and Oxy-Fuel Flames

3. Materials and Methods

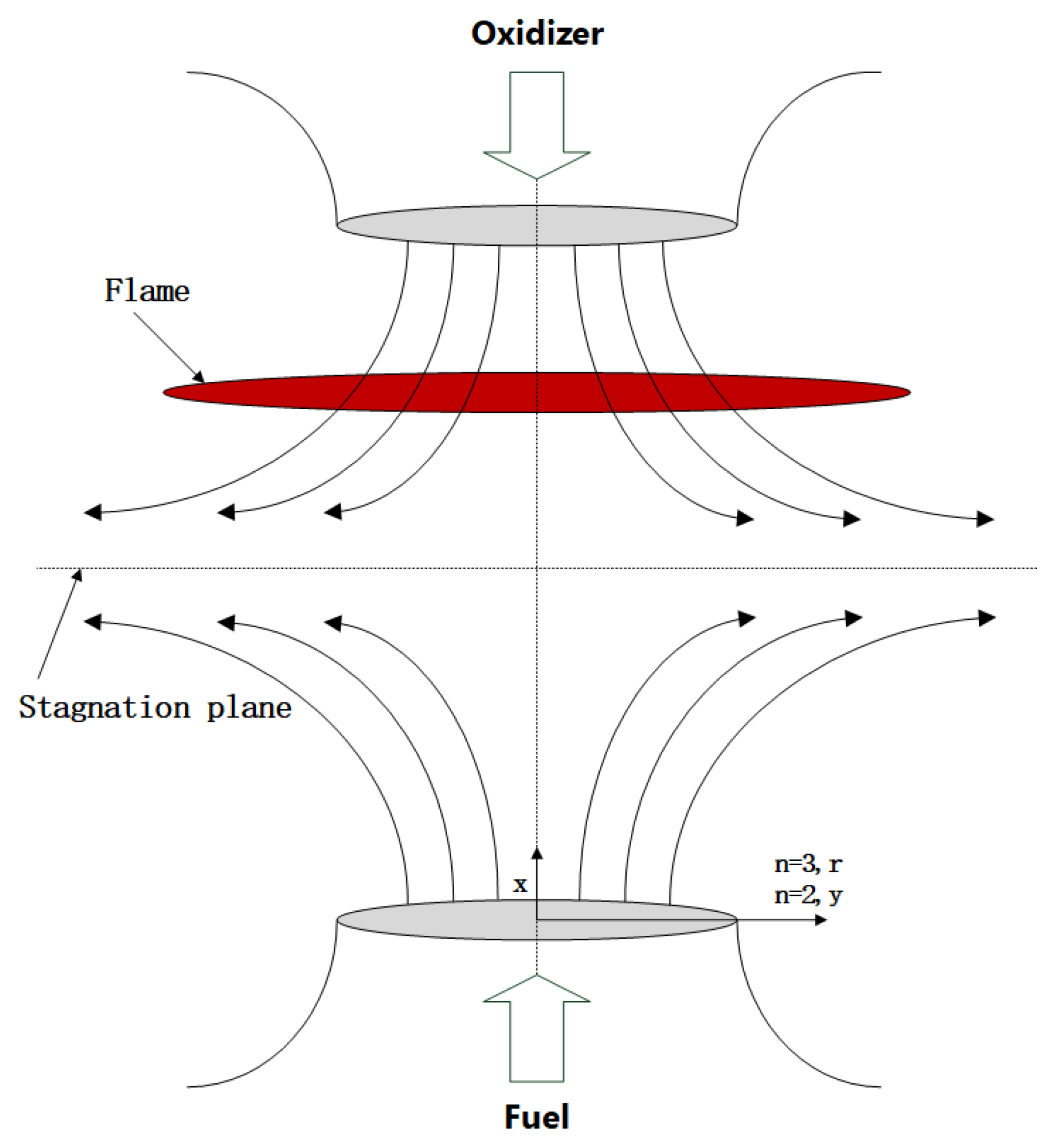

3.1. Theoretical Model

3.2. Radiation Models

3.2.1. Optically Thin Model (OTM)

3.2.2. Statistical Narrow-Band Model (SNB)

4. Conclusions

- (a)

- For methane–air flames, radiative heat loss leads to a radiative extinction limit at low strain rates, reduces the flame temperature, and diminishes the flammable area. Radiation reabsorption only has a minor influence on the fuel limits and flammable area of methane–air flames, primarily at low strain rates. Therefore, the OTM can be reasonably applied to calculate relevant flame characteristics for methane–air flames.

- (b)

- For methane oxy-fuel flames, the influence of radiation reabsorption on flame temperature becomes more pronounced as the strain rate decreases. When calculating the maximum flame temperature as a function of the strain rate, the peak temperature occurs at a lower strain rate in the SNB model compared with the OTM, which neglects reabsorption, indicating that the OTM overestimates radiative heat loss. Radiation reabsorption significantly affects both the critical fuel concentration and the flammable area of methane oxy-fuel flames at low strain rates. The variation of the flammable region with strain rate differs among the three models. For the ADI and SNB models, the flammable area follows SLow > SMid > SHigh, whereas for the OTM, the trend is SMid > Shigh > SLow.

- (c)

- By comparing the critical fuel concentrations of air flames and oxy-fuel flames under different radiation models, it is observed that at medium and high strain rates, the (XF)min values of air flames fall within the range of XO = 0.35–0.4 for oxy-fuel flames. However, at low strain rates, a higher oxygen concentration is required in the oxy-fuel flame to match the (XF)min value of the air flame under the same conditions. Therefore, the SNB model should be used for calculating oxy-fuel flames to ensure higher accuracy.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bolegenova, S.; Askarova, A.; Georgiev, A.; Nugymanova, A.; Maximov, V.; Bolegenova, S.; Adil’Bayev, N. Staged supply of fuel and air to the combustion chamber to reduce emissions of harmful substances. Energy 2024, 293, 130622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- do Espírito Santo Nóbrega, C.R.; da Silva, J.B.S.; Monteiro, T.O.; Crnkovic, P.M.; Cruz, G. An investigation on the kinetic behavior and thermodynamic parameters of the oxy-fuel combustion of Brazilian agroindustrial residues. J. Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 2023, 45, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Liu, D.; Jiang, B. Soot formation and combustion characteristics in confined mesoscale combustors under conventional and oxy-combustion conditions (O2/N2 and O2/CO2). Fuel 2020, 264, 116808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, S.; Mondal, S.S. A review on the progress and prospects of oxy-fuel carbon capture and sequestration (CCS) technology. Fuel 2022, 308, 122057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Ouyang, Z.; Wang, W.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, S. Experimental study on the influence of O2/CO2 ratios on NO conversion and emission during combustion and gasification of high-temperature coal char. Fuel 2022, 310, 122311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zha, X.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, L.; Zhao, Z.; Wu, F.; Li, X.; Luo, C.; Zhang, L. Experimental study on the catalytic effect of AAEMs on NO reduction during coal combustion in O2/CO2 atmosphere. Carbon Capture Sci. Technol. 2024, 10, 100159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Kim, J.S.; Chung, J.O.; Yun, J.H.; Keel, S.I. Chemical effects of added CO2 on the extinction characteristics of H2/CO/CO2 syngas diffusion flames. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2009, 34, 8756–8762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, W.B.; Wang, Z.H.; He, Y.; Whiddon, R.; Zhou, Y.J.; Li, Z.S.; Cen, K.F. Effect of N2/CO2 dilution on laminar burning velocity of H2–CO–O2 oxy-fuel premixed flame. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2015, 40, 1203–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoerlle, C.A.; Pereira, F.M. Effects of CO2 addition on soot formation of ethylene non-premixed flames under oxygen enriched atmospheres. Combust. Flame 2019, 203, 407–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, A.; Wang, C.; Jiang, C.; Xu, H.; Ma, X.; Xu, C.; Bao, X. Effect of CO2 and N2 dilution on laminar premixed MTHF/air flames: Experiments and kinetic studies. Fuel 2019, 255, 115659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Xue, Q.; Zuo, H.; She, X.; Wang, J. Effects of CO2 and N2 dilution on the characteristics and NOx emission of H2/CH4/CO/air partially premixed flame. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 15909–15921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Hwang, D.J.; Choi, J.G.; Lee, K.-M.; Keel, S.-I.; Shim, S.-H. Chemical effects of CO2 addition to oxidizer and fuel streams on flame structure in H2–O2 counterflow diffusion flames. Int. J. Energy Res. 2003, 27, 1205–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, C.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, J.; He, X.; Zhou, L. Effects of N2 and CO2 addition to oxidizer on soot formation in n-heptane laminar diffusion flame at preheating temperatures. Fuel 2024, 374, 132480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Chen, L.; Bengtsson, P.E.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, J.; Wu, X.; Cen, K. Optical investigations on particles evolution and flame properties during pulverized coal combustion in O2/N2 and O2/CO2 conditions. Fuel 2019, 251, 394–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Jia, L.; Nakamura, H.; Tezuka, T.; Hasegawa, S.; Maruta, K. Study on flame responses and ignition characteristics of CH4/O2/CO2 mixture in a micro flow reactor with a controlled temperature profile. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2015, 84, 360–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhang, X.; Li, C. Comparisons of the uncoupled effects of CO2 on the CH4/O2 counterflow diffusion flame under high pressure. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Shi, B.; Peng, W.; Cao, Q.; Xie, D.; Dong, W.; Wang, N. Effects of N2 and CO2 dilution on the combustion characteristics of C3H8/O2 mixture in a swirl tubular flame burner. Exp. Therm. Fluid Sci. 2019, 100, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konnov, A.A.; Dyakov, I.V. Measurement of propagation speeds in adiabatic cellular premixed flames of CH4 + O2 + CO2. Exp. Therm. Fluid Sci. 2005, 29, 901–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazas, A.N.; Fiorina, B.; Lacoste, D.A.; Schuller, T. Effects of water vapor addition on the laminar burning velocity of oxygen-enriched methane flames. Combust. Flame 2011, 158, 2428–2440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhang, M.; Gong, J.; Jin, W.; Huang, Z. Experimental and numerical study on laminar flame characteristics of methane oxy-fuel mixtures highly diluted with CO2. Energy Fuels 2013, 27, 6231–6237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Wei, H. Experimental investigation of laminar flame speeds of propane in O2/CO2 atmosphere and kinetic simulation. Fuel 2020, 268, 117347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Yu, Q. Effect of the elevated initial temperature on the laminar flame speeds of oxy-methane mixtures. Energy 2018, 147, 876–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papas, P.; Rais, R.M. Thermo-diffusive instabilities in axisymmetric, non-premixed jet flames. Proc. Combust. Inst. 2009, 32, 1181–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, B.; Liu, X.; Yang, R.; Yan, S.; Mu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, J.; Zheng, H.; Li, S. Experimental study of gliding arc plasma-assisted combustion in a blast furnace gas fuel model combustor: Flame structures, extinction limits and combustion stability. Fuel 2022, 322, 124280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.; Bukar, M.; Basnet, S.; Magnotti, G. Effects of O2 concentration of O2/CO2 co-flow on the flame stability of non-premixed coaxial jet flame. Fuel 2024, 371, 132114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruta, K.; Abe, K.; Hasegawa, S.; Maruyama, S.; Sato, J. Extinction characteristics of CH4/CO2 versus O2/CO2 counterflow non-premixed flames at elevated pressures up to 0.7 MPa. Proc. Combust. Inst. 2007, 31, 1223–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Jia, L.; Onishi, T.; Grajetzki, P.; Nakamura, H.; Tezuka, T.; Hasegawa, S.; Maruta, K. Study on stretch extinction limits of CH4/CO2 versus high temperature O2/CO2 counterflow non-premixed flames. Combust. Flame 2014, 161, 1526–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.H.; Park, J.W.; Park, H.Y.; Park, J.; Park, J.H.; Lim, I.G. Chemical and radiation effects on flame extinction and NOx formation in oxy-methane combustion diluted with CO2. Fuel 2016, 177, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Li, X.; Chen, Y.; Wang, X. Study on stretch extinction characteristics of methane/carbon dioxide versus oxygen/carbon dioxide counterflow non-premixed combustion under elevated pressures. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2021, 92, 103994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; He, Y.; Hu, B.; Zhu, J.; Zhou, B.; Lu, Q. Effects of radiation reabsorption on the flame speed and NO emission of NH3/H2/air flames at various hydrogen ratios. Fuel 2022, 327, 125176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okuno, T.; Nakamura, H.; Tezuka, T.; Hasegawa, S.; Takase, K.; Katsuta, M.; Kikuchi, M.; Maruta, K. Study on the combustion limit, near-limit extinction boundary, and flame regimes of low-Lewis-number CH4/O2/CO2 counterflow flames under microgravity. Combust. Flame 2016, 172, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, J.; Huo, J.; Wang, X.; Jiang, L.; Zhao, D. C-shaped extinction curves and lean fuel limits of methane oxy-fuel diffusion flames at different oxygen concentrations. Fuel 2020, 259, 116296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Cai, L.; Guan, Y.; Liu, W.; Xiang, Y.; Li, J.; He, T. Numerical study on an original oxy-fuel combustion power plant with efficient utilization of flue gas waste heat. Energy 2020, 193, 116854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, J.Z.; Talei, M.; Gordon, R.L. Flame stretch and flame thickening in turbulent stoichiometric hydrogen/methane premixed jet flames. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 196, 152452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, C.J.; Liu, J.B.; Law, C.K. Structural response of counterflow diffusion flames to strain rate variations. Combust. Flame 1995, 102, 481–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, S. Diffusion flame extinction at small stretch rates: The mechanism of radiative loss. Combust. Flame 1986, 65, 31–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kee, R.J.; Miller, J.A.; Evans, G.H.; Dixon-Lewis, G. A computational model of the structure and extinction of strained, opposed flow, premixed methane-air flames. Symp. Int. Combust. 1989, 22, 1479–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, S.; Fang, J.; Hu, L.; Chen, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wang, J.; Chung, S.H. Buoyancy effect on extinction limits in low strain rate counterflow diffusion flames of methane. Proc. Combust. Inst. 2024, 40, 105396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomidokoro, T.; Yokomori, T.; Im, H.G. Laminar flame speed of methane/air stratified flames under elevated temperature and pressure. Proc. Combust. Inst. 2023, 39, 1669–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, H.; Arai, F.; Okazaki, K. Role of CO2 in the CH4 oxidation and H2 formation during fuel-rich combustion in O2/CO2 environments. Combust. Flame 2013, 160, 2375–2385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garnayak, S.; Selvaraj, P.; Lee, B.J.; Reddy, V.M. A computational investigation of pressure effects on soot formation in counterflow diffusion flames of methane in MILD conditions. Combust. Flame 2025, 272, 113863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruta, K.; Kataoka, T.; Kim, N.I.; Minaev, S.; Fursenko, R. Characteristics of combustion in a narrow channel with a temperature gradient. Proc. Combust. Inst. 2005, 30, 2429–2436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, H.; Shindo, M. Effects of radiation heat loss on laminar premixed ammonia/air flames. Proc. Combust. Inst. 2019, 37, 1741–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Niioka, T. The effect of radiationreabsorption on NO formation in CH4/air counterflow diffusionflames. Combust. Theory Model. 2001, 5, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Niioka, T. Numerical study of radiation reabsorption effect on NOx formation in CH4/air counterflow premixed flames. Proc. Combust. Inst. 2002, 29, 2211–2217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Kelm, S.; Kampili, M.; Kumar, G.V.; Allelein, H.-J. Monte Carlo method with SNBCK nongray gas model for thermal radiation in containment flows. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2022, 390, 111689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Zhang, M.; Yang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Lu, Q. Image temperature calculation for gas and particle system by the mid-infrared spectrum using DRESOR and SNBCK model. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2022, 138, 106414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| a = 10 s−1 | a = 80 s−1 | a = 200 s−1 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ADI | 0.12 | 0.19 | 0.30 |

| SNB | 0.13 | 0.20 | 0.31 |

| OTM | 0.14 | 0.20 | 0.31 |

| Model | a (s−1) | XO = 1.0 | XO = 0.8 | XO = 0.6 | XO = 0.4 | XO = 0.35 | XO = 0.30 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADI | 10 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.17 |

| 80 | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.14 | 0.18 | 0.22 | 0.3 | |

| 200 | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.16 | 0.22 | 0.3 | 0.49 | |

| SNB | 10 | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.16 | 0.19 | 0.26 |

| 80 | 0.12 | 0.13 | 0.15 | 0.20 | 0.23 | 0.35 | |

| 200 | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.15 | 0.23 | 0.31 | 0.54 | |

| OTM | 10 | 0.14 | 0.16 | 0.18 | 0.29 | 0.35 | 0.55 |

| 80 | 0.12 | 0.13 | 0.17 | 0.21 | 0.25 | 0.38 | |

| 200 | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.20 | 0.25 | 0.32 | 0.57 |

| ADI | SNB | OTM | |

|---|---|---|---|

| a = 10 s−1 | 0.22 | 0.23 | 0.27 |

| a = 80 s−1 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.26 |

| a = 200 s−1 | 0.28 | 0.28 | 0.29 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, S.; Wang, J.; Chen, Y.; Li, Y.; Chen, J.; Li, S.; Yan, Z. Effects of Radiation Reabsorption on the Flammability Limit and Critical Fuel Concentration of Methane Oxy-Fuel Diffusion Flame. Molecules 2026, 31, 124. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010124

Wang S, Wang J, Chen Y, Li Y, Chen J, Li S, Yan Z. Effects of Radiation Reabsorption on the Flammability Limit and Critical Fuel Concentration of Methane Oxy-Fuel Diffusion Flame. Molecules. 2026; 31(1):124. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010124

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Shuochao, Jingfu Wang, Ying Chen, Yi Li, Jiquan Chen, Shun Li, and Zewei Yan. 2026. "Effects of Radiation Reabsorption on the Flammability Limit and Critical Fuel Concentration of Methane Oxy-Fuel Diffusion Flame" Molecules 31, no. 1: 124. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010124

APA StyleWang, S., Wang, J., Chen, Y., Li, Y., Chen, J., Li, S., & Yan, Z. (2026). Effects of Radiation Reabsorption on the Flammability Limit and Critical Fuel Concentration of Methane Oxy-Fuel Diffusion Flame. Molecules, 31(1), 124. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010124