Development of Oleic Acid Composite Vesicles as a Topical Delivery System: An Evaluation of Stability, Skin Permeability, and Antioxidant and Antibacterial Activities

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

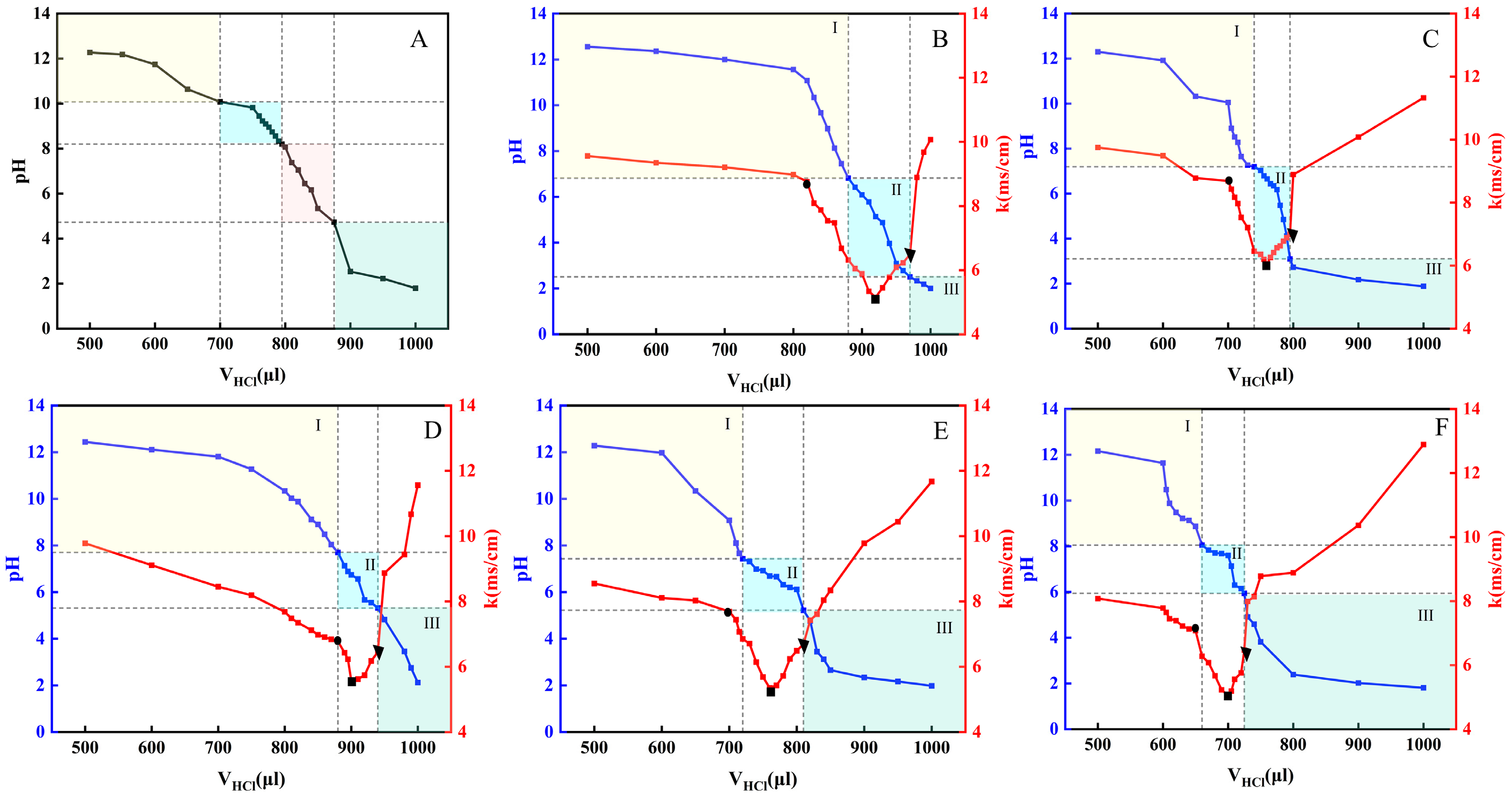

2.1. Establishment of the OA/TW40-FAV pH Window

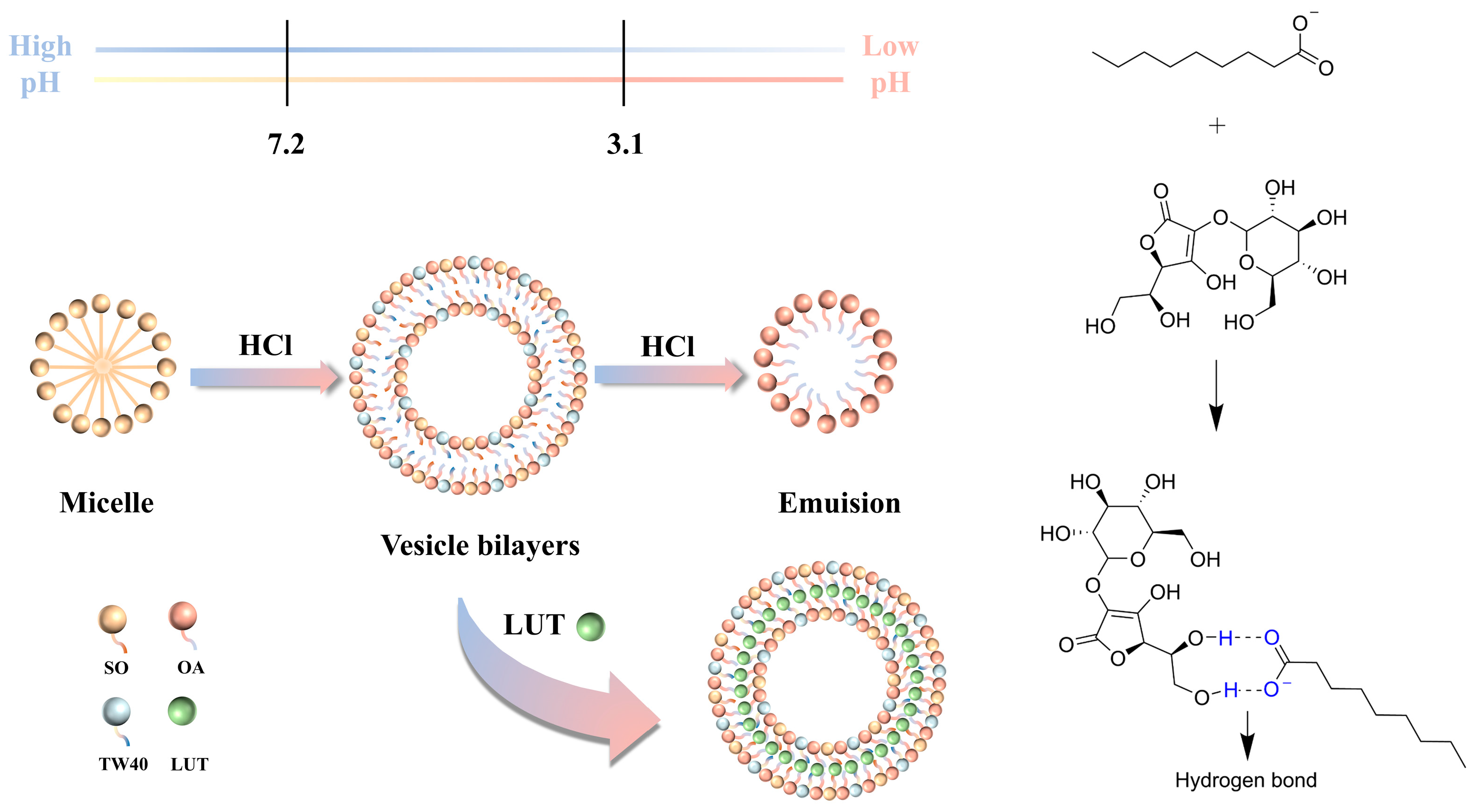

2.2. Mechanism of OA/TW40-FAV Formation and Migration Broadening pH Window

2.3. Characterization of OA/TW40-FAV

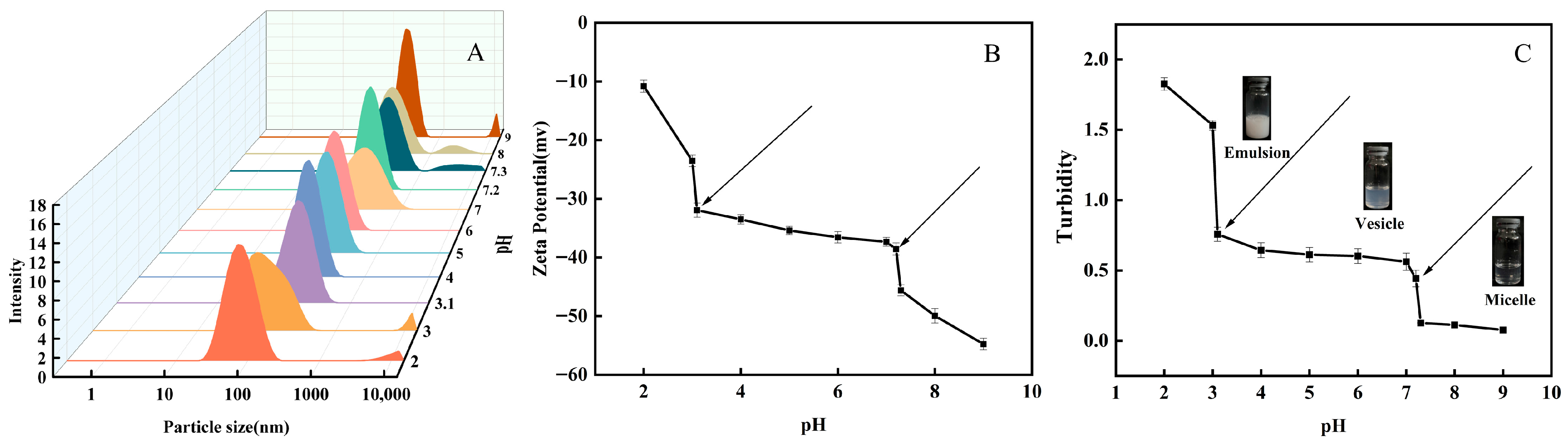

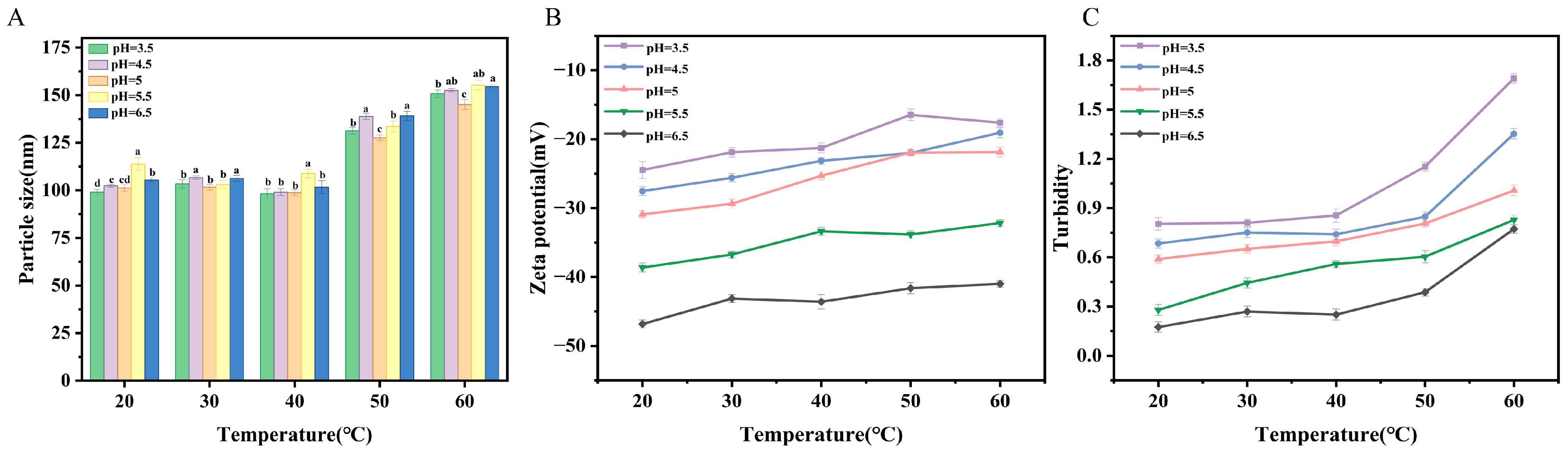

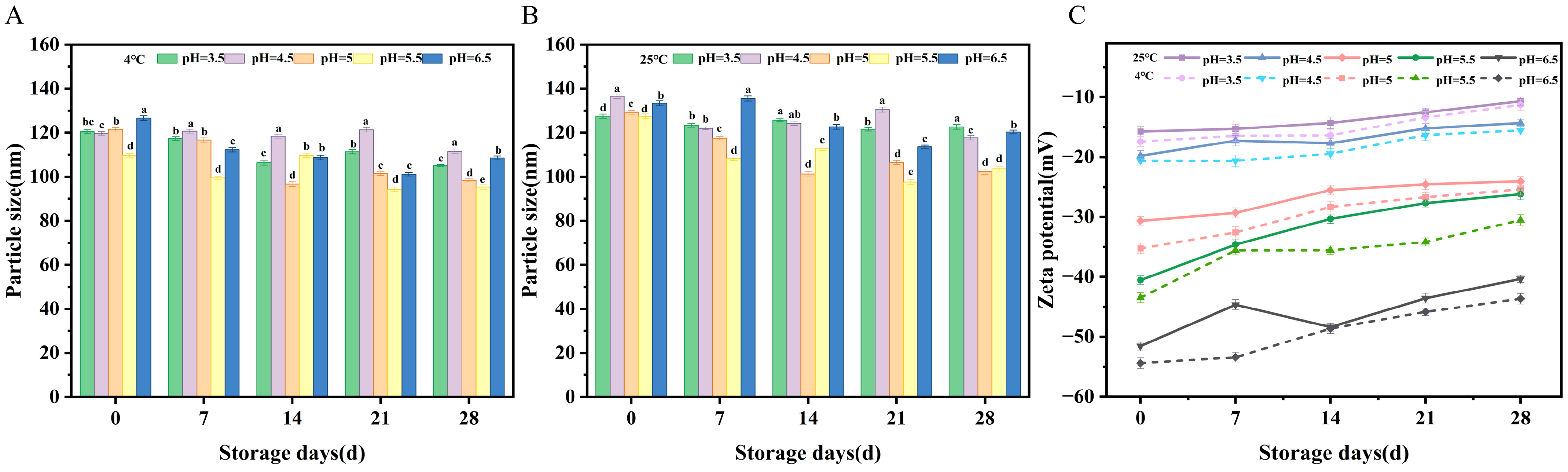

2.3.1. Particle Size Analysis

2.3.2. Zeta Potential Analysis

2.3.3. Turbidity Analysis

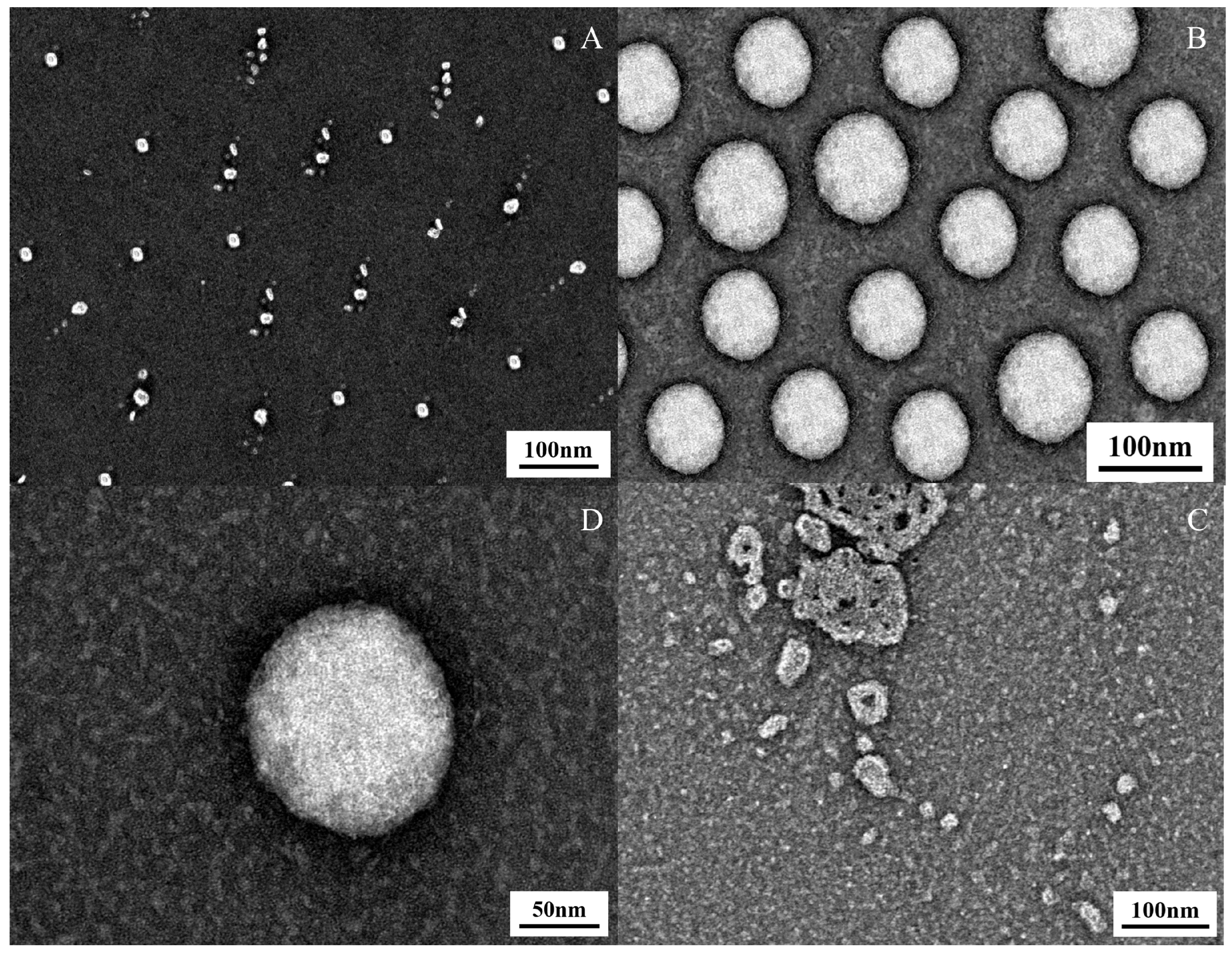

2.3.4. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) Observations

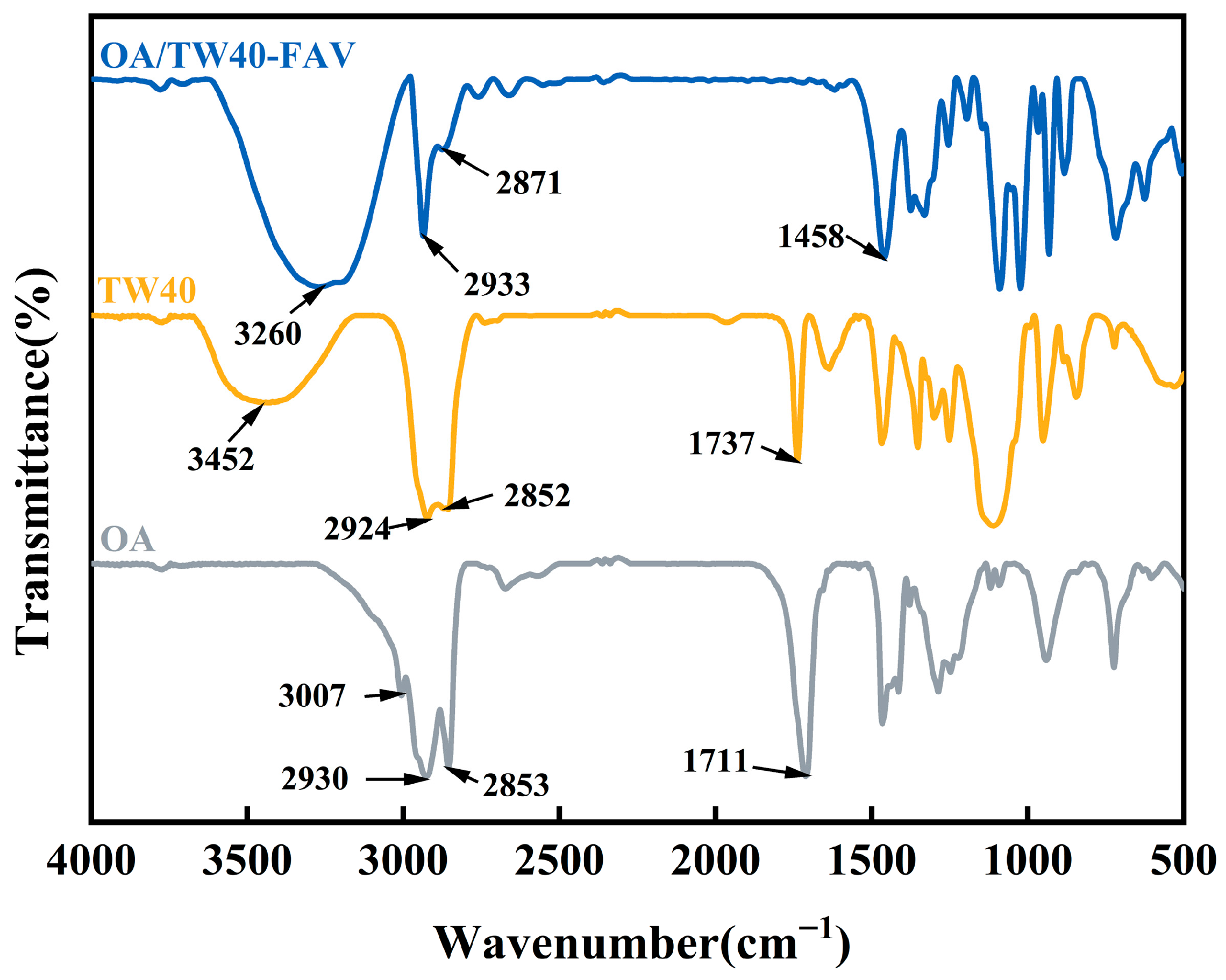

2.3.5. FT-IR Analysis of OA/TW40 Composite Solution System

2.4. Stability Analysis of OA/TW40-FAV

2.4.1. Temperature Stability

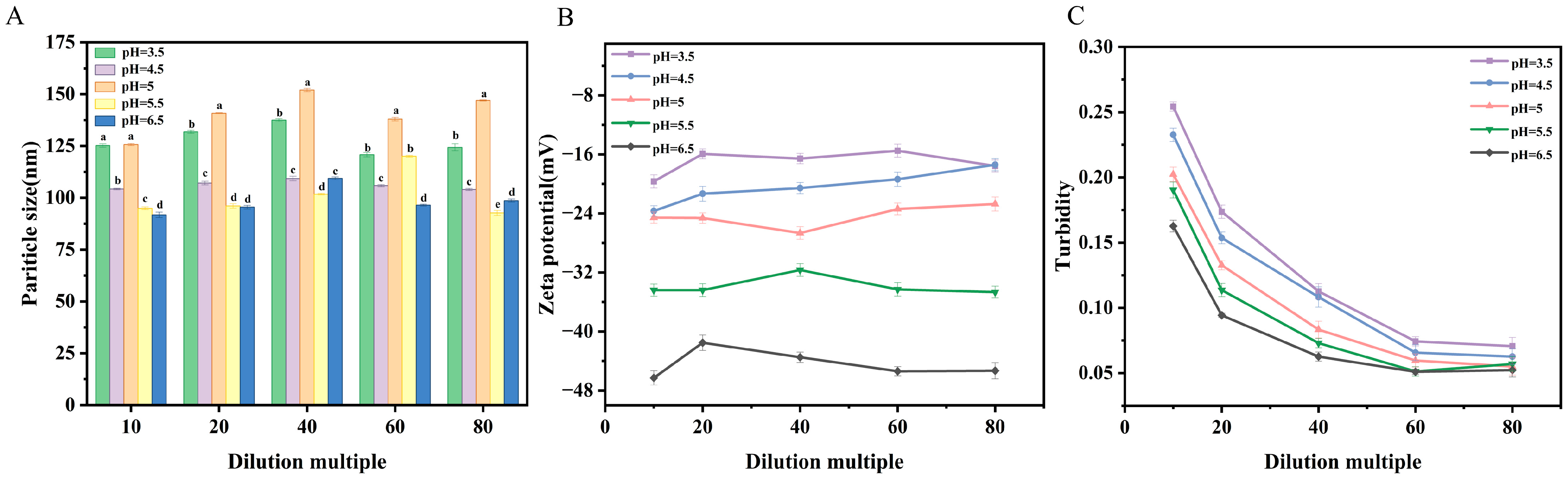

2.4.2. Dilution Stability

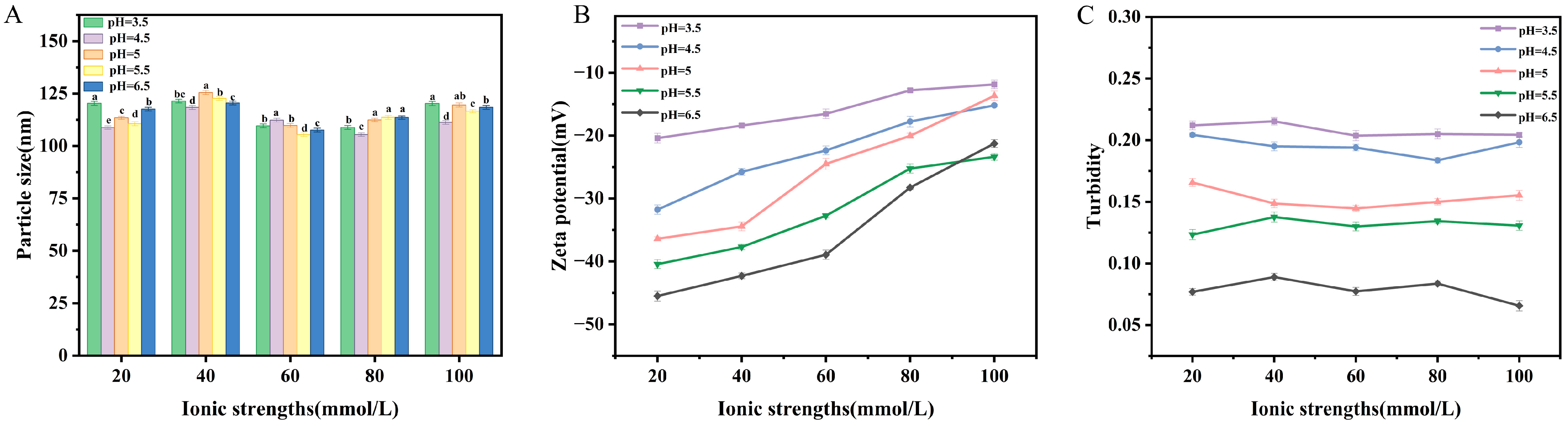

2.4.3. Salt Concentration Stability

2.4.4. Storage Time Stability

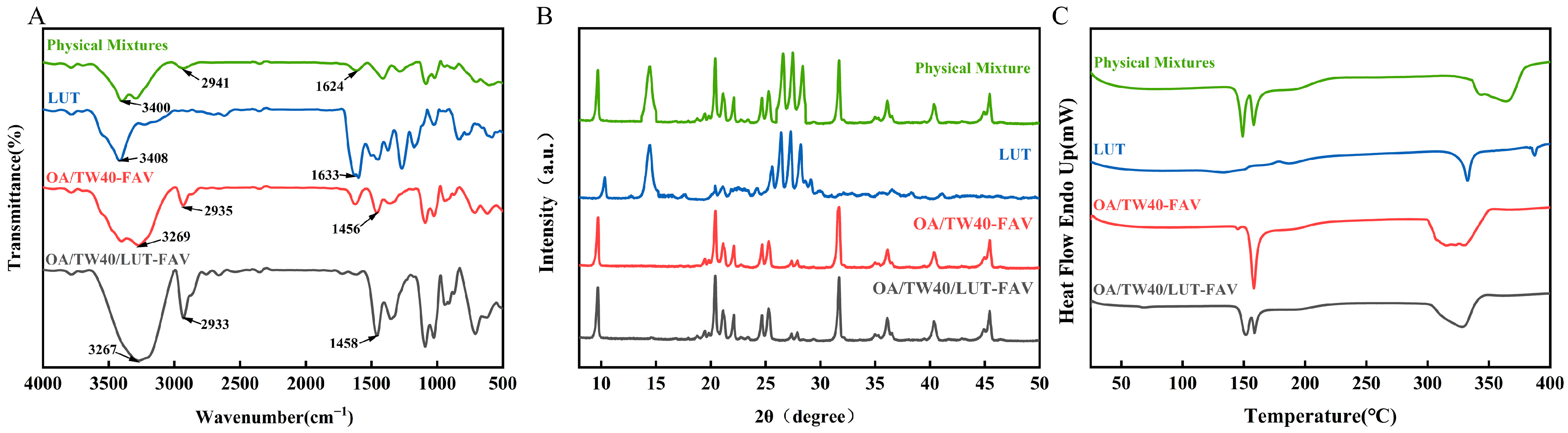

2.5. FT-IR, XRD and DSC Analysis of OA/TW40/LUT-FAV

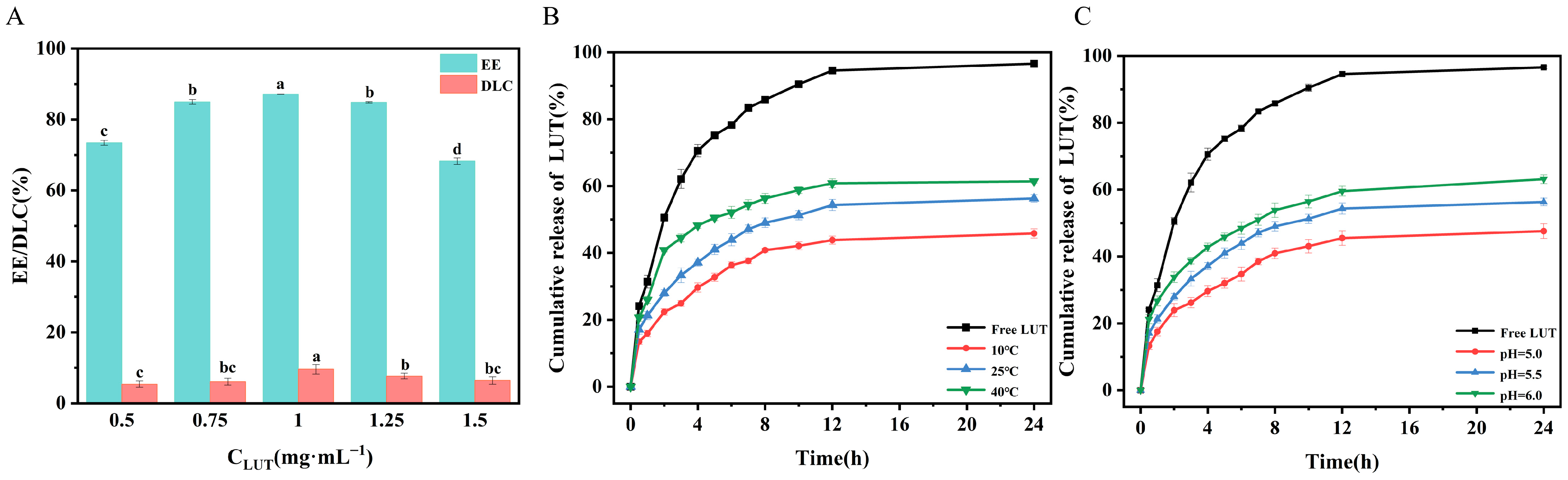

2.6. Encapsulation and In Vitro Release Studies of OA/TW40/LUT-FAV

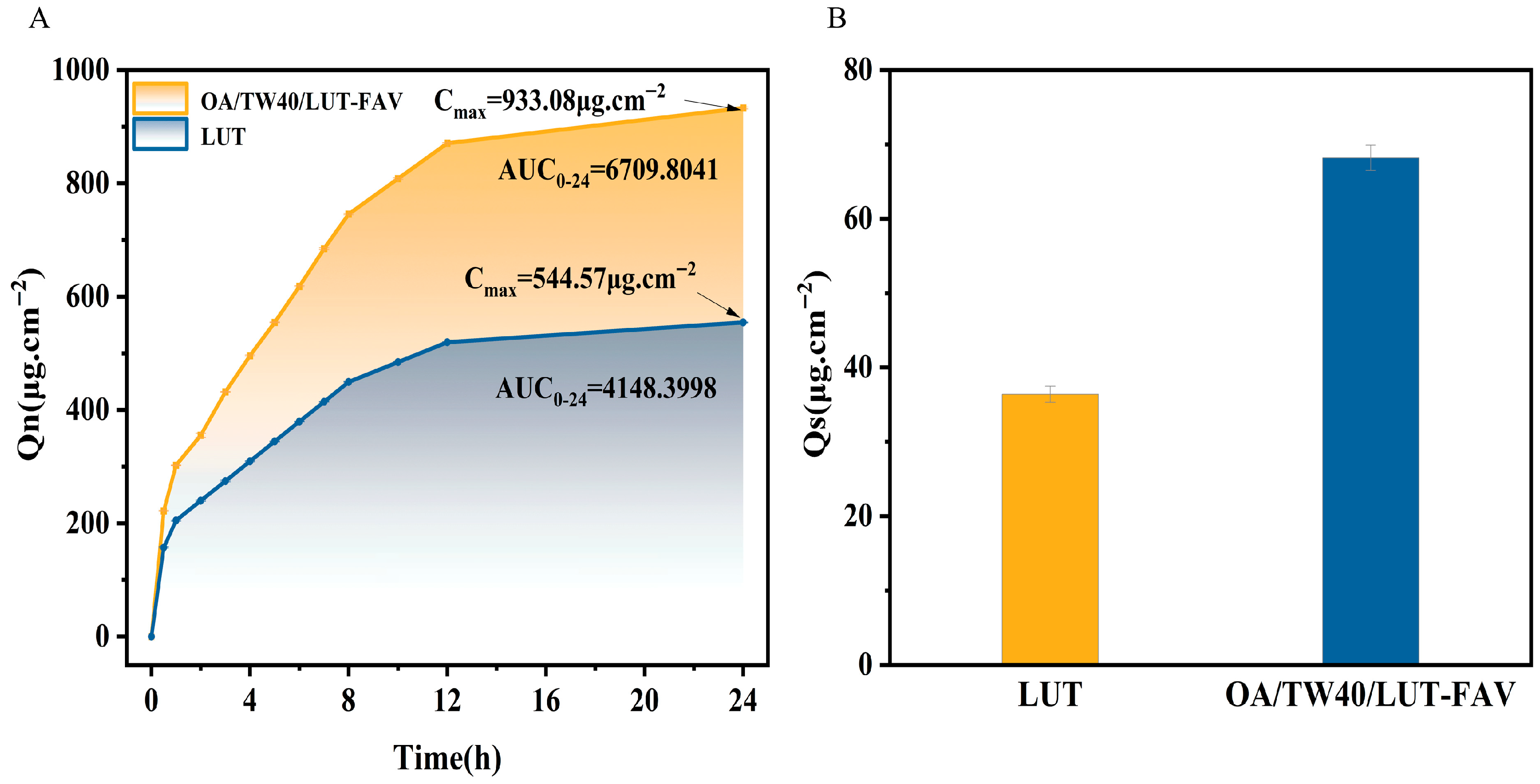

2.7. In Vitro Transdermal and Skin Retention Analysis of OA/TW40/LUT-FAV

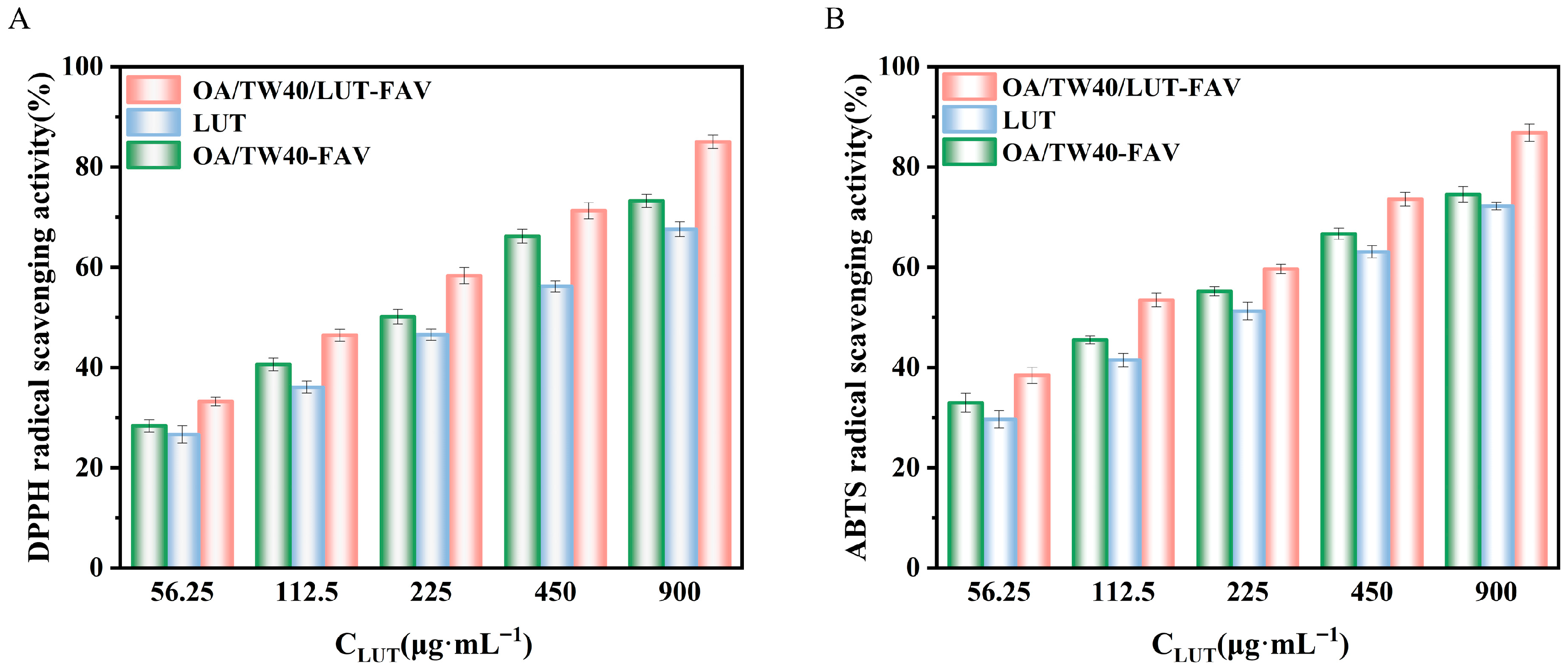

2.8. Analysis of Antioxidant Properties of OA/TW40/LUT-FAV

2.8.1. DPPH Radical Scavenging Activity

2.8.2. ABTS Free Radical Scavenging Activity

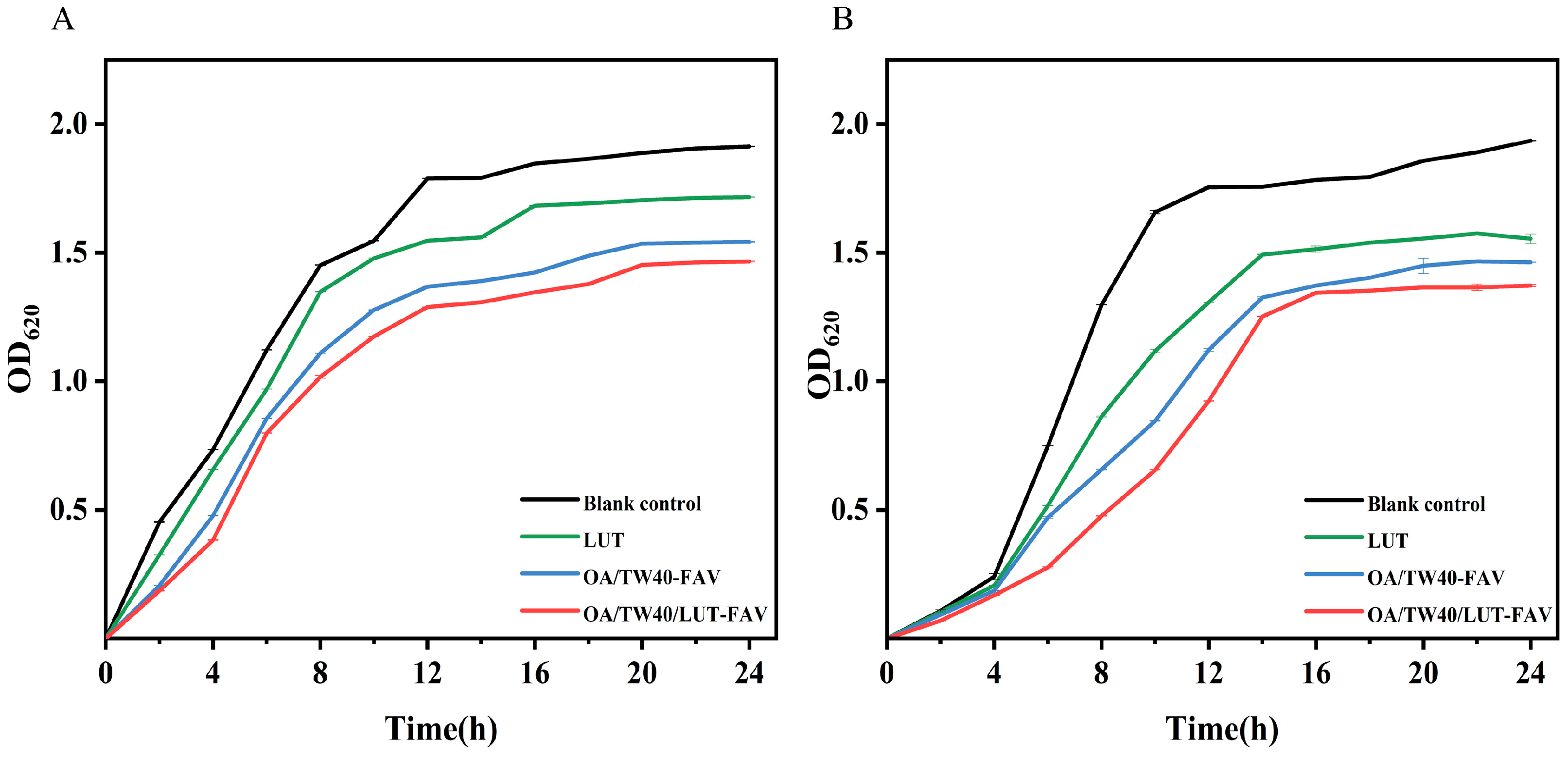

2.9. Analysis of Bacteriostatic Properties of OA/TW40/LUT-FAV

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

3.2. Preparation of OA/TW40-FAV and OA/TW40/LUT-FAV

3.2.1. Preparation Procedure

3.2.2. Establishment of pH Titration Curve

3.2.3. Measurement of Conductivity

3.3. Characterization of OA/TW40-FAV

3.3.1. Measurement of Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS)

3.3.2. Measurement of Zeta Potential

3.3.3. Measurement of Turbidity

3.3.4. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

3.4. OA/TW40-FAV Stability Study

3.4.1. Effect of Temperature

3.4.2. Effect of Dilution Factor

3.4.3. Effect of Salt Concentration

3.4.4. Effect of Storage Time

3.5. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FT-IR)

3.6. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD)

3.7. Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

3.8. Efficiency of Encapsulation

3.9. In Vitro Release Studies

3.10. Percutaneous Permeability Assessment

3.10.1. Skin Permeability

3.10.2. Skin Retention

3.10.3. Skin Sample Quality Control and Limitation

3.11. Determination of Antioxidant Activity of OA/TW40/LUT-FAV

3.11.1. DPPH Free Radical Scavenging Activity

3.11.2. ABTS Free Radical Scavenging Activity

3.12. Antimicrobial Activity

3.12.1. Microbial Strains and Culture Conditions

3.12.2. Growth Curve

3.13. Statistical Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lens, M. Niosomes as Vesicular Nanocarriers in Cosmetics: Characterisation, Development and Efficacy. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Wang, D.; Zhang, M.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Li, J.; Wu, D. Design of Oleic Acid/Alkyl Glycoside Composite Vesicles as Cosmetics Carrier: Stability, Skin Permeability and Antioxidant Activity. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. 2024, 35, 579–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calder, P.C. Functional Roles of Fatty Acids and Their Effects on Human Health. J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 2015, 39, 18S–32S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Carvalho, C.; Caramujo, M. The Various Roles of Fatty Acids. Molecules 2018, 23, 2583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kastaniotis, A.J.; Autio, K.J.; Kerätär, J.M.; Monteuuis, G.; Mäkelä, A.M.; Nair, R.R.; Pietikäinen, L.P.; Shvetsova, A.; Chen, Z.; Hiltunen, J.K. Mitochondrial Fatty Acid Synthesis, Fatty Acids and Mitochondrial Physiology. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA-Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2017, 1862, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnould, A.; Gaillard, C.; Fameau, A.-L. pH-Responsive Fatty Acid Self-Assembly Transition Induced by UV Light. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2015, 458, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Wang, Y.; Fan, P.; Jiang, L.; Zhuang, W.; Han, Y.; Zhang, H. Self-Assembled Vesicles Formed by C18 Unsaturated Fatty Acids and Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate as a Drug Delivery System. Colloids Surf. Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2019, 568, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, T.M.; Cullis, P.R. Liposomal Drug Delivery Systems: From Concept to Clinical Applications. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2013, 65, 36–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wamberg, M.C.; Wieczorek, R.; Brier, S.B.; De Vries, J.W.; Kwak, M.; Herrmann, A.; Monnard, P.-A. Functionalization of Fatty Acid Vesicles through Newly Synthesized Bolaamphiphile–DNA Conjugates. Bioconjug. Chem. 2014, 25, 1678–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, G.; Li, Z.; Xia, R.; Li, F.; O’Neill, B.E.; Goodwin, J.T.; Khant, H.A.; Chiu, W.; Li, K.C. Partially polymerized liposomes: Stable against leakage yet capable of instantaneous release for remote controlled drug delivery. Nanotechnology 2011, 22, 155605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundu, N.; Mondal, D.; Sarkar, N. Dynamics of the vesicles composed of fatty acids and other amphiphile mixtures: Unveiling the role of fatty acids as a model protocell membrane. Biophys. Rev. 2020, 12, 1117–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namani, T.; Walde, P. From Decanoate Micelles to Decanoic Acid/Dodecylbenzenesulfonate Vesicles. Langmuir 2005, 21, 6210–6219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caschera, F.; De La Serna, J.B.; Löffler, P.M.G.; Rasmussen, T.E.; Hanczyc, M.M.; Bagatolli, L.A.; Monnard, P.-A. Stable Vesicles Composed of Monocarboxylic or Dicarboxylic Fatty Acids and Trimethylammonium Amphiphiles. Langmuir 2011, 27, 14078–14090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raeisi, S.; Chavoshi, H.; Mohammadi, M.; Ghorbani, M.; Sabzichi, M.; Ramezani, F. Naringenin-Loaded Nano-Structured Lipid Carrier Fortifies Oxaliplatin-Dependent Apoptosis in HT-29 Cell Line. Process Biochem. 2019, 83, 168–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Mandal, A. Experimental Investigation of PEG 6000/Tween 40/SiO2 NPs Stabilized Nanoemulsion Properties: A Versatile Oil Recovery Approach. J. Mol. Liq. 2020, 319, 114087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gendrisch, F.; Esser, P.R.; Schempp, C.M.; Wölfle, U. Luteolin as a Modulator of Skin Aging and Inflammation. BioFactors 2021, 47, 170–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, M.; Rauf, A.; Abu-Izneid, T.; Nadeem, M.; Shariati, M.A.; Khan, I.A.; Imran, A.; Orhan, I.E.; Rizwan, M.; Atif, M.; et al. Luteolin, a Flavonoid, as an Anticancer Agent: A Review. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 112, 108612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arampatzis, A.S.; Pampori, A.; Droutsa, E.; Laskari, M.; Karakostas, P.; Tsalikis, L.; Barmpalexis, P.; Dordas, C.; Assimopoulou, A.N. Occurrence of Luteolin in the Greek Flora, Isolation of Luteolin and Its Action for the Treatment of Periodontal Diseases. Molecules 2023, 28, 7720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juszczak, A.M.; Marijan, M.; Jakupović, L.; Tomczykowa, M.; Tomczyk, M.; Zovko Končić, M. Glycerol and Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents Extraction for Preparation of Luteolin-Rich Jasione Montana Extracts with Cosmeceutical Activity. Metabolites 2022, 13, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesio, A.Y.; Robledo, S.N. Analytical Determinations of Luteolin. BioFactors 2021, 47, 141–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Wang, C.; Zou, B.; Fu, L.; Ren, S.; Zhang, X. Design and Evaluation of Tretinoin Fatty Acid Vesicles for the Topical Treatment of Psoriasis. Molecules 2023, 28, 7868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristiano, M.C.; Mancuso, A.; Fresta, M.; Torella, D.; De Gaetano, F.; Ventura, C.A.; Paolino, D. Topical Unsaturated Fatty Acid Vesicles Improve Antioxidant Activity of Ammonium Glycyrrhizinate. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsao, H.-K.; Tseng, W.L. The Interactions Between Ionic Surfactants and Phosphatidylcholine Vesicles: Conductometry. J. Chem. Phys. 2001, 115, 8125–8132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Song, A.; Dong, S.; Chen, J.; Hao, J. A Systematic Investigation and Insight into the Formation Mechanism of Bilayers of Fatty Acid/Soap Mixtures in Aqueous Solutions. Langmuir 2013, 29, 12380–12388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asker, D.; Weiss, J.; McClements, D.J. Correction to “Analysis of the Interactions of a Cationic Surfactant (Lauric Arginate) with an Anionic Biopolymer (Pectin): Isothermal Titration Calorimetry, Light Scattering, and Microelectrophoresis”. Langmuir 2017, 33, 4878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midekessa, G.; Godakumara, K.; Ord, J.; Viil, J.; Lättekivi, F.; Dissanayake, K.; Kopanchuk, S.; Rinken, A.; Andronowska, A.; Bhattacharjee, S.; et al. Zeta Potential of Extracellular Vesicles: Toward Understanding the Attributes That Determine Colloidal Stability. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 16701–16710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, M.T.; Black, R.A.; Cornell, C.; Williams, J.A.; Lee, K.K.; Keller, S.L. Stable Fatty Acid Vesicles Form under Low-pH Conditions and Interact with Amino Acids and Dipeptides. Biophys. J. 2016, 110, 85a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larkin, P. Infrared and Raman Spectroscopy: Principles and Spectral Interpretation, 2nd ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altunayar Unsalan, C.; Sahin, I.; Kazanci, N. A concentration dependent spectroscopic study of binary mixtures of plant sterol stigmasterol and zwitterionic dimyristoyl phosphatidylcholine multilamellar vesicles: An FTIR study. J. Mol. Struct. 2018, 1174, 127–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Wang, H.; Song, A.; Hao, J. Superhydrogels of Nanotubes Capable of Capturing Heavy-metal Ions. Chem.—Asian J. 2014, 9, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, B.; Yu, B.; Liu, L.; Xiu, Y.; Wang, H. Experimental Investigation of the Strong Stability, Antibacterial and Anti-Inflammatory Effect and High Bioabsorbability of a Perilla Oil or Linseed Oil Nanoemulsion System. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 25739–25749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Hua, Z.; Hu, X.; Liu, C.; Pi, B.; Han, Y. Hydrogels Consisting of Vesicles Constructed via the Self-Assembly of a Supermolecular Complex Formed from α-Cyclodextrin and Perfluorononanoic Acid. Langmuir 2019, 35, 16893–16899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D.; Han, Z.; Liu, L.; Wang, Y.; Xin, S.; Zhang, H.; Yu, Z. Solubility Enhancement of Myricetin by Inclusion Complexation with Heptakis-O-(2-Hydroxypropyl)-β-Cyclodextrin: A Joint Experimental and Theoretical Study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Y.; Yu, Z.; Lin, K.; Sun, C.; Dai, L.; Yang, S.; Mao, L.; Yuan, F.; Gao, Y. Fabrication and Characterization of Resveratrol Loaded Zein-Propylene Glycol Alginate-Rhamnolipid Composite Nanoparticles: Physicochemical Stability, Formation Mechanism and in Vitro Digestion. Food Hydrocoll. 2019, 95, 336–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Yang, J. Preparation of Oleic Acid–Carboxymethylcellulose Sodium Composite Vesicle and Its Application in Encapsulating Nicotinamide. Polym. Int. 2021, 70, 1604–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Du, N.; Song, Y.; Song, S.; Hou, W. Microviscosity, Encapsulation, and Permeability of 2-Ketooctanoic Acid Vesicle Membranes. Soft Matter 2017, 13, 3514–3520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalil, R.M.; Abdelbary, A.; Arini, S.K.E.; Basha, M.; El-Hashemy, H.A.; Farouk, F. Development of Tizanidine Loaded Aspasomes as Transdermal Delivery System: Ex-Vivo and in-Vivo Evaluation. J. Liposome Res. 2021, 31, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foti, M.C. Use and Abuse of the DPPH• Radical. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015, 63, 8765–8776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floegel, A.; Kim, D.-O.; Chung, S.-J.; Koo, S.I.; Chun, O.K. Comparison of ABTS/DPPH Assays to Measure Antioxidant Capacity in Popular Antioxidant-Rich US Foods. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2011, 24, 1043–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, S.; Wang, D.; Wen, X.; Li, X.; Fang, F.; Richel, A.; Xiao, N.; Fauconnier, M.-L.; Hou, C.; Zhang, D. Incorporation of Cinnamon Essential Oil-Loaded Pickering Emulsion for Improving Antimicrobial Properties and Control Release of Chitosan/Gelatin Films. Food Hydrocoll. 2023, 138, 108438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Yang, J.; Guo, X.; Xia, Y. Self-Assembled Vesicles of Sodium Oleate and Chitosan Quaternary Ammonium Salt in Acidic or Alkaline Aqueous Solutions. Colloid Polym. Sci. 2019, 297, 1455–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee, S. DLS and Zeta Potential—What They Are and What They Are Not? J. Control. Release 2016, 235, 337–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitchener, B.G.; Wainwright, J.; Parsons, A.J. A Review of the Principles of Turbidity Measurement. Prog. Phys. Geogr. Earth Environ. 2017, 41, 620–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meija, J.; Bushell, M.; Couillard, M.; Beck, S.; Bonevich, J.; Cui, K.; Foster, J.; Will, J.; Fox, D.; Cho, W.; et al. Particle Size Distributions for Cellulose Nanocrystals Measured by Transmission Electron Microscopy: An Interlaboratory Comparison. Anal. Chem. 2020, 92, 13434–13442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fameau, A.-L.; Arnould, A.; Saint-Jalmes, A. Responsive Self-Assemblies Based on Fatty Acids. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 2014, 19, 471–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, K.; Xie, H.; Wang, Y.; Woo, M.W.; Chen, Q.; Lai, S.; Xiong, H.; Zhao, Q. Whey Protein Isolate Nanofibrils Formed with Phosphoric Acid: Formation, Structural Characteristics, and Emulsion Stability. Food Hydrocoll. 2023, 135, 108170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Zhao, J.; Liu, K.; Wu, C.; Liang, F. Stealth PEGylated Chitosan Polyelectrolyte Complex Nanoparticles as Drug Delivery Carrier. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. 2021, 32, 1387–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Chi, J.; Ye, X.; Wang, S.; Liang, J.; Yue, P.; Xiao, H.; Gao, X. Nanoliposomes as Delivery System for Anthocyanins: Physicochemical Characterization, Cellular Uptake, and Antioxidant Properties. LWT 2021, 139, 110554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, P.; Teng, F.; Zhou, F.; Song, Z.; Meng, N.; Feng, R. Methoxy Poly (Ethylene Glycol)-b-Poly (δ-Valerolactone) Copolymeric Micelles for Improved Skin Delivery of Ketoconazole. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. 2017, 28, 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mongkolsuttirat, K.; Buajarern, J. Uncertainty Evaluation of Crystallite Size Measurements of Nanoparticle Using X-Ray Diffraction Analysis (XRD). J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 1719, 12054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyva-Porras, C.; Cruz-Alcantar, P.; Espinosa-Solís, V.; Martínez-Guerra, E.; Piñón-Balderrama, C.I.; Compean Martínez, I.; Saavedra-Leos, M.Z. Application of Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) and Modulated Differential Scanning Calorimetry (MDSC) in Food and Drug Industries. Polymers 2019, 12, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Zhai, B.; Cheng, J.; Sun, J.; Zhang, X.; Guo, D. Phloretin Transfersomes for Transdermal Delivery: Design, Optimization, and in Vivo Evaluation. Molecules 2023, 28, 6790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, C.; Li, Z. A Review of Drug Release Mechanisms from Nanocarrier Systems. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2017, 76, 1440–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Xu, W.; Liu, H. Fabrication of Chitosan Functionalized Dual Stimuli-Responsive Injectable Nanogel to Control Delivery of Doxorubicin. Colloid Polym. Sci. 2023, 301, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, B.; Huang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Ye, J.; Xu, H.; Chen, W.; Long, X. Niosomal Nanocarriers for Enhanced Skin Delivery of Quercetin with Functions of Anti-Tyrosinase and Antioxidant. Molecules 2019, 24, 2322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padula, C.; Machado, I.P.; Vigato, A.A.; De Araujo, D.R. New Strategies for Improving Budesonide Skin Retention. Pharmaceutics 2021, 14, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengíbar, M.; Miralles, B.; Heras, Á. Use of Soluble Chitosans in Maillard Reaction Products with β-Lactoglobulin: Emulsifying and Antioxidant Properties. LWT 2017, 75, 440–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Ding, Z.; Duan, W.; Mo, M.; Su, Z.; Bi, Y.; Kong, F. Optimized Preparation Process for Naringenin and Evaluation of Its Antioxidant and A-glucosidase Inhibitory Activities. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2020, 44, e14931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Zhang, M.; Mujumdar, A.S.; Wang, M. Quinoa Protein Isolate-Gum Arabic Coacervates Cross-Linked with Sodium Tripolyphosphate: Characterization, Environmental Stability, and Sichuan Pepper Essential Oil Microencapsulation. Food Chem. 2023, 404, 134536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| OA/TW40 Different Proportions | pH Windows | Range Width |

|---|---|---|

| 25:1 | 5.94–8.05 | 2.11 |

| 20:1 | 5.22–7.43 | 2.21 |

| 15:1 | 5.32–7.70 | 2.38 |

| 10:1 | 3.10–7.20 | 4.10 |

| 5:1 | 2.51–6.82 | 4.31 |

| pH | Mode | Equation | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | Zero order | F = 0.0172t + 0.1932 | 0.6355 |

| First order | −ln(1 − F) = 0.025t + 0.2185 | 0.7046 | |

| Higuchi | F = 0.1028t0.5 + 0.0764 | 0.9029 | |

| Ritger–Peppas | F = 19.57t0.31 | 0.9643 | |

| 5.5 | Zero order | F = 0.0199t + 0.2428 | 0.6013 |

| First order | −ln(1 − F) = 0.0321t + 0.2868 | 0.6894 | |

| Higuchi | F = 0.1211t0.5 + 0.1031 | 0.8839 | |

| Ritger–Peppas | F = 24.67t0.3 | 0.9616 | |

| 6 | Zero order | F = 0.0211t + 0.2824 | 0.5963 |

| First order | −ln(1 − F) = 0.0373t + 0.3407 | 0.7184 | |

| Higuchi | F = 0.1289t0.5 +0.1335 | 0.8803 | |

| Ritger–Peppas | F = 29.05t0.27 | 0.9791 | |

| 5.5 (LUT) | Zero order | F = 0.0347t + 0.4285 | 0.5553 |

| First order | −ln(1 − F) = 0.1476t + 0.5142 | 0.8714 | |

| Higuchi | F = 0.2156t0.5 + 0.1752 | 0.8510 | |

| Ritger–Peppas | F = 43.25t0.3 | 0.9321 |

| Kinetic Models | Original Formula | Rewritten Formula |

|---|---|---|

| Zero order | F = k0t | F = k0t |

| First order | F = 1 − e−k1t | −ln(1 − F) = k1t |

| Higuchi | F = kHt0.5 | F = kHt0.5 |

| Ritger–Peppas | F = k × (tn) | F = k × (tn) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ma, X.; Zhang, Q.; Yang, Y.; Zhan, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Li, J.; Wu, D. Development of Oleic Acid Composite Vesicles as a Topical Delivery System: An Evaluation of Stability, Skin Permeability, and Antioxidant and Antibacterial Activities. Molecules 2026, 31, 122. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010122

Ma X, Zhang Q, Yang Y, Zhan Y, Zhang X, Zhao Y, Li J, Wu D. Development of Oleic Acid Composite Vesicles as a Topical Delivery System: An Evaluation of Stability, Skin Permeability, and Antioxidant and Antibacterial Activities. Molecules. 2026; 31(1):122. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010122

Chicago/Turabian StyleMa, Xinyue, Qinqing Zhang, Ying Yang, Yuqi Zhan, Xiangyu Zhang, Yanli Zhao, Jinlian Li, and Dongmei Wu. 2026. "Development of Oleic Acid Composite Vesicles as a Topical Delivery System: An Evaluation of Stability, Skin Permeability, and Antioxidant and Antibacterial Activities" Molecules 31, no. 1: 122. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010122

APA StyleMa, X., Zhang, Q., Yang, Y., Zhan, Y., Zhang, X., Zhao, Y., Li, J., & Wu, D. (2026). Development of Oleic Acid Composite Vesicles as a Topical Delivery System: An Evaluation of Stability, Skin Permeability, and Antioxidant and Antibacterial Activities. Molecules, 31(1), 122. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010122