Rotation Conformational Effects of Selected Cytotoxic Cardiac Glycosides on Their Interactions with Na+/K+-ATPase

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

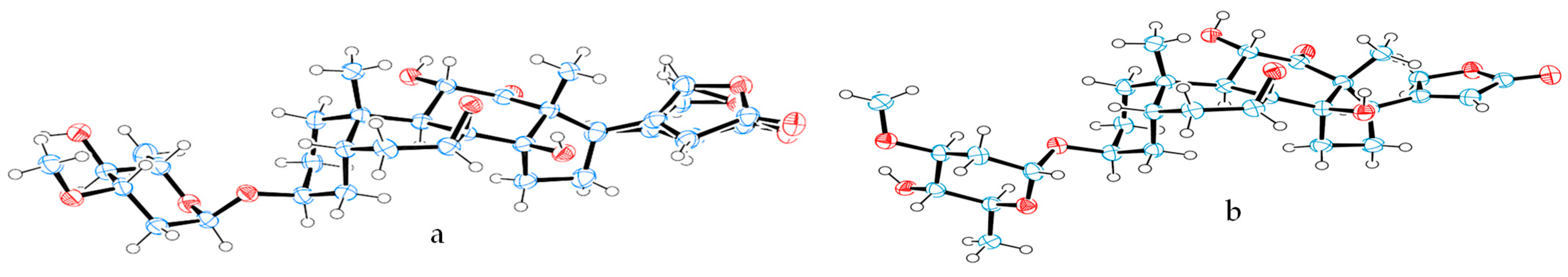

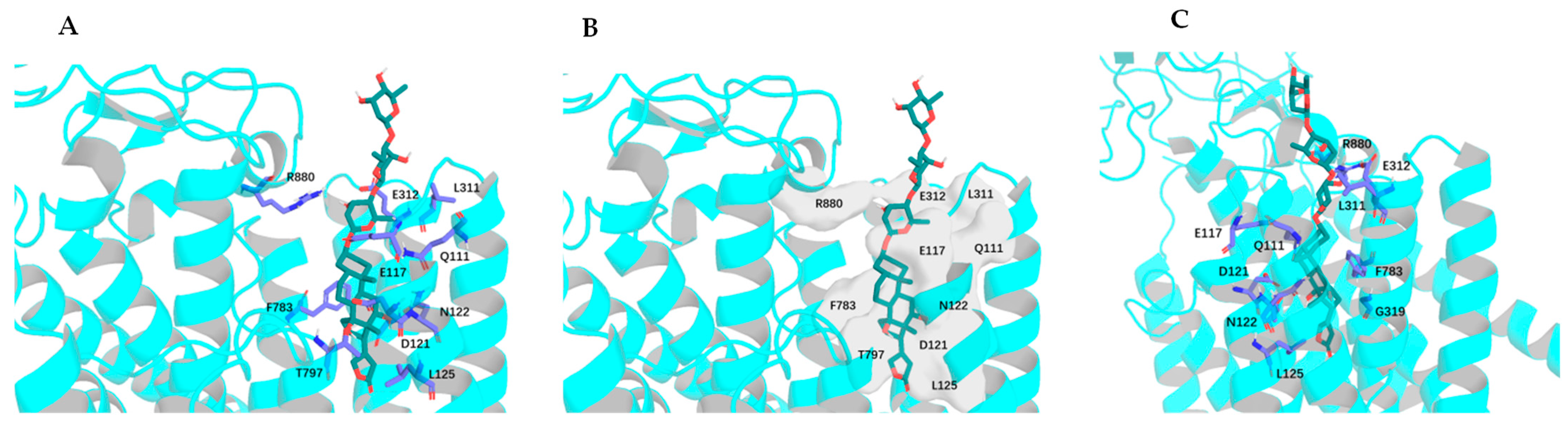

2.1. Overview of the Rotation Conformations of Digoxin and Their Binding to NKA

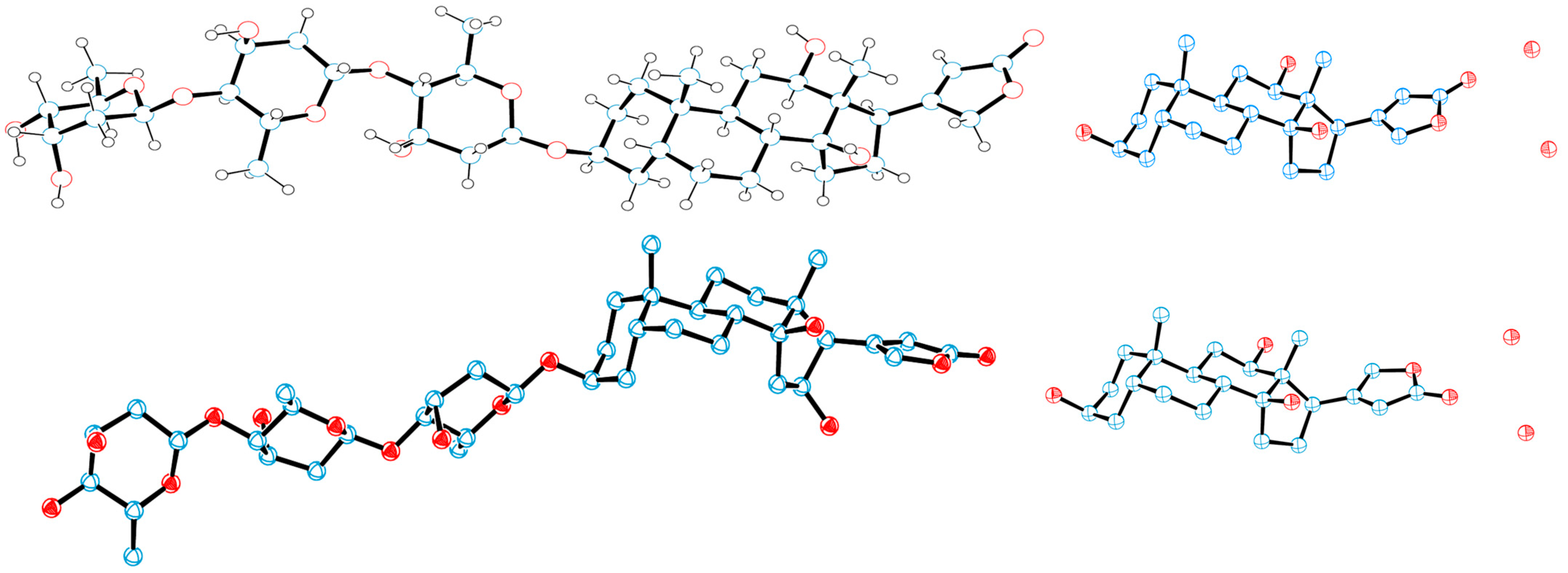

2.2. Impact of Rotation of the C-3 Saccharide Moiety and C-17 Lactone Unit of Digoxin on Its Binding to NKA

2.3. Impact of Rotation of C-17 Lactone Unit of Digoxigenin on Its Binding to NKA

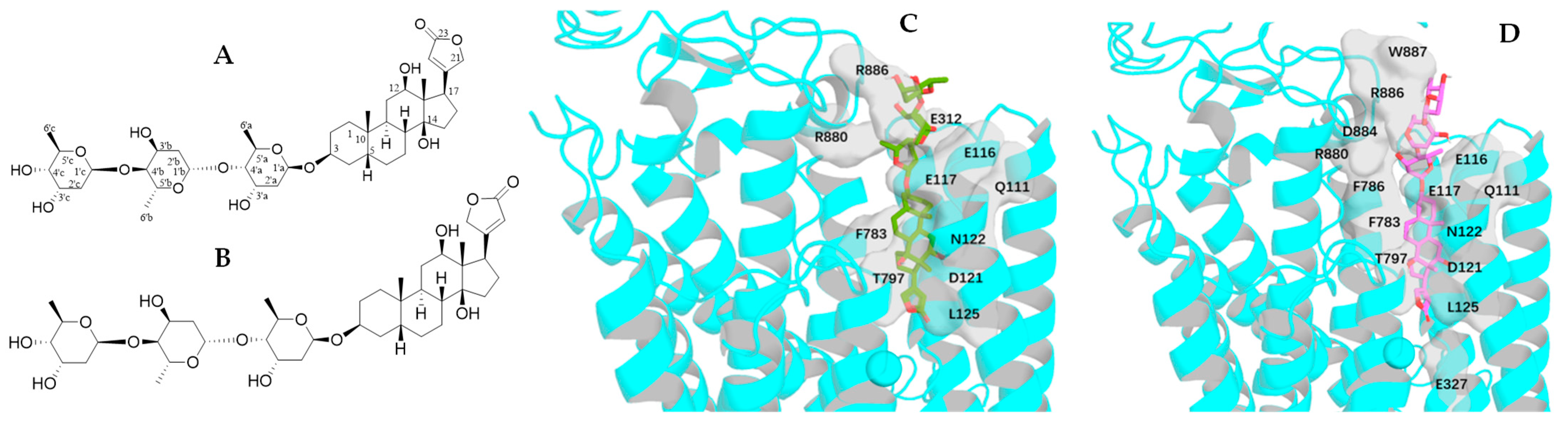

2.4. Impact of Rotation of the C-3 Saccharide Moiety and the C-17 Lactone Unit of Gitoxin on Its Binding to NKA

2.5. Impact of Rotation of the C-3 Saccharide Moiety and the C-17 Lactone Unit of Cryptanoside A on Its Binding to NKA

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Compounds and Biological Evaluation

4.2. ORTEP Plotting

4.3. Docking Simulation for NKA

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Patel, S. Plant-derived cardiac glycosides: Role in heart ailments and cancer management. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2016, 84, 1036–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, R.A.; Yang, P.; Pawlus, A.D.; Block, K.I. Cardiac glycosides as novel cancer therapeutic agents. Mol. Interv. 2008, 8, 36–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, D.; Kumavath, R.; Barh, D.; Azevedo, V.; Ghosh, P. Anticancer and antiviral properties of cardiac glycosides: A review to explore the mechanism of actions. Molecules 2020, 25, 3596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayogu, J.I.; Odoh, A.S. Prospects and therapeutic applications of cardiac glycosides in cancer remediation. ACS Comb. Sci. 2020, 22, 543–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, Y.; Anderson, A.T.; Meyer, G.; Lauber, K.M.; Gallucci, J.C.; Kinghorn, A.D. Digoxin and its Na+/K+-ATPase-targeted actions on cardiovascular diseases and cancer. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2024, 114, 117939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medford, R.M. Digitalis and the Na+,K+-ATPase. Heart Dis. Stroke 1993, 2, 250–255. [Google Scholar]

- Clausen, M.V.; Hilbers, F.; Poulsen, H. The structure and function of the Na,K-ATPase isoforms in health and disease. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marck, P.V.; Pierre, S.V. Na/K-ATPase signaling and cardiac pre/postconditioning with cardiotonic steroids. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 2336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Cai, T.; Yuan, Z.; Wang, H.; Liu, L.; Haas, M.; Maksimova, E.; Huang, X.-Y.; Xie, Z.-J. Binding of Src to Na+/K+-ATPase forms a functional signaling complex. Mol. Biol. Cell 2006, 17, 317–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Xie, Z. Protein interaction and Na/K-ATPase-mediated signal transduction. Molecules 2017, 22, 990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mijatovic, T.; Ingrassia, L.; Facchini, V.; Kiss, R. Na+/K+-ATPase α subunits as new targets in anticancer therapy. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 2008, 12, 1403–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bejček, J.; Spiwok, V.; Kmoníčková, E.; Rimpelová, S. Na+/K+-ATPase revisited: On its mechanism of action, role in cancer, and activity modulation. Molecules 2021, 26, 1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leslie, T.K.; James, A.D.; Zaccagna, F.; Grist, J.T.; Deen, S.; Kennerley, A.; Riemer, F.; Kaggie, J.D.; Gallagher, F.A.; Gilbert, F.J.; et al. Sodium homeostasis in the tumor microenvironment. BBA–Rev. Cancer 2019, 1872, 188304. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, K.; Li, Z.; Chen, Y.; Yin, F.; Ji, X.; Zhou, J.; Li, X.; Zeng, T.; Fei, C.; Ren, C.; et al. Na, K-ATPase a1 cooperates with its endogenous ligand to reprogram immune microenvironment of lung carcinoma and promotes immune escape. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eade5393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, N.F.Z.; Cerella, C.; Simões, C.M.O.; Diederich, M. Anticancer and immunogenic properties of cardiac glycosides. Molecules 2017, 22, 1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Škubník, J.; Pavlíčková, V.; Rimpelová, S. Cardiac glycosides as immune system modulators. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cornelius, F.; Kanai, R.; Toyoshima, C. A structural view on the functional importance of the sugar moiety and steroid hydroxyls of cardiotonic steroids in binding to Na, K-ATPase. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 6602–6616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laursen, M.; Gregersen, J.L.; Yatime, L.; Nissen, P.; Fedosova, N.U. Structures and characterization of digoxin- and bufalin-bound Na+,K+-ATPase compared with the ouabain-bound complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 1755–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, Y.; Ribas, H.T.; Heath, K.; Wu, S.; Ren, J.; Shriwas, P.; Chen, X.; Johnson, M.E.; Cheng, X.; Burdette, J.E.; et al. Na+/K+-ATPase-targeted cytotoxicity of (+)-digoxin and several semisynthetic derivatives. J. Nat. Prod. 2020, 83, 638–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Wu, S.; Burdette, J.E.; Cheng, X.; Kinghorn, A.D. Structural insights into the interactions of digoxin and Na+/K+-ATPase and other targets for the inhibition of cancer cell proliferation. Molecules 2021, 26, 3672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Y. Docking and pharmacophore methods in drug discovery. ChemistrySelect 2025, 10, e01269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salo-Ahen, O.M.H.; Alanko, I.; Bhadane, R.; Bonvin, A.M.J.J.; Honorato, R.V.; Hossain, S.; Juffer, A.H.; Kabedev, A.; Lahtela-Kakkonen, M.; Larsen, A.S.; et al. Molecular dynamics simulations in drug discovery and pharmaceutical development. Processes 2021, 9, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorber, D.M.; Shoichet, B.K. Flexible ligand docking using conformational ensembles. Protein Sci. 1998, 7, 938–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Totrov, M.; Abagyan, R. Flexible ligand docking to multiple receptor conformations: A practical alternative. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2008, 18, 178–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fantini, J.; Azzaz, F.; Di Scala, C.; Aulas, A.; Chahinian, H.; Yahi, N. Conformationally adaptive therapeutic peptides for diseases caused by intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs). New paradigm for drug discovery: Target the target, not the arrow. Pharmacol. Ther. 2025, 267, 108797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corbeil, C.R.; Therrien, E.; Moitessier, N. Modeling reality for optimal docking of small molecules to biological targets. Curr. Comput. Aided-Drug Des. 2009, 5, 241–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toniolo, C.; Temussi, P. Conformational flexibility of aspartame. Biopolymers 2016, 106, 376–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrugia, L.J. WinGX and ORTEP for Windows: An update. J. Appl. Cryst. 2012, 45, 849–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Kaweesa, E.N.; Tian, L.; Wu, S.; Sydara, K.; Xayvue, M.; Moore, C.E.; Soejarto, D.D.; Cheng, X.; Yu, J.; et al. The cytotoxic cardiac glycoside (−)-cryptanoside A from the stems of Cryptolepis dubia and its molecular targets. J. Nat. Prod. 2023, 86, 1411–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Go, K.; Kartha, G.; Chen, J.P. Structure of digoxin. Acta Cryst. 1980, B36, 1811–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohrer, D.C.; Fullerton, D.S. Structures of modified cardenolides. III. Digoxigenin dihydrate. Acta Cryst. 1980, B36, 1565–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Go, K.; Kartha, G. Structure of gitoxin. Acta Cryst. 1980, B36, 3034–3040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S. Digoxin, a new digitalis glucoside. J. Chem. Soc. 1930, 508–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aulabaugh, A.E.; Crouch, R.C.; Martin, G.E.; Ragouzeos, A.; Shockcor, J.P.; Spitzer, T.D.; Farrant, R.D.; Hudson, B.D.; Lindon, J.C. The conformational behavior of the cardiac glycoside digoxin as indicated by NMR spectroscopy and molecular dynamics calculations. Carbohydr. Res. 1992, 230, 201–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eichhorn, E.J.; Gheorghiade, M. Digoxin. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2002, 44, 251–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Lázaro, M.; Pastor, N.; Azrak, S.S.; Ayuso, M.J.; Austin, C.A.; Cortés, F. Digitoxin inhibits the growth of cancer cell lines at concentrations commonly found in cardiac patients. J. Nat. Prod. 2005, 68, 1642–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krstić, D.; Krinulović, K.; Spasojević-Tišma, V.; Joksić, G.; Momić, T.; Vasić, V. Effects of digoxin and gitoxin on the enzymatic activity and kinetic parameters of Na+/K+-ATPase. J. Enzyme Inhibit. Med. Chem. 2004, 19, 409–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verdonk, M.L.; Cole, J.C.; Hartshorn, M.J.; Murray, C.W.; Taylor, R.D. Improved protein-ligand docking using GOLD. Proteins 2003, 52, 609–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelley, J.C.; Cholleti, A.; Frye, L.L.; Greenwood, J.R.; Timlin, M.R.; Uchimaya, M. Epik: A software program for pKα prediction and protonation state generation for drug-like molecules. J. Comput. Aid. Mol. Des. 2007, 21, 681–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trott, O.; Olson, A.J. AutoDock Vina: Improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J. Comput. Chem. 2010, 31, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seeliger, D.; de Groot, B.L. Ligand docking and binding site analysis with PyMOL and Autodock/Vina. J. Comput. Aid. Mol. Des. 2010, 24, 417–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Chen, W.-L.; Lantvit, D.D.; Sass, E.J.; Shriwas, P.; Ninh, T.N.; Chai, H.-B.; Zhang, X.; Soejarto, D.D.; Chen, X.; et al. Cardiac glycoside constituents of Streblus asper with potential antineoplastic activity. J. Nat. Prod. 2017, 80, 648–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, Y.; Wu, S.; Chen, S.; Burdette, J.E.; Cheng, X.; Kinghorn, A.D. Interaction of (+)-strebloside and its derivatives with Na+/K+-ATPase and other targets. Molecules 2021, 26, 5675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stockwell, G.R.; Thornton, J.M. Conformational diversity of ligands bound to proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 2006, 356, 928–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, R.; Olson, A.J.; Goodsell, D.S. Automated prediction of ligand-binding sites in proteins. Proteins 2008, 70, 1506–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pettersen, E.F.; Goddard, T.D.; Huang, C.C.; Couch, G.S.; Greenblatt, D.M.; Meng, E.C.; Ferrin, T.E. UCSF Chimera—A visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 2004, 25, 1605–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maier, J.A.; Martinez, C.; Kasavajhala, K.; Wickstrom, L.; Hauser, K.E.; Simmerling, C. ff14SB: Improving the accuracy of protein side chain and backbone parameters from ff99SB. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2015, 11, 3696–3713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, W.; Kollman, P.A.; Case, D.A. Automatic atom type and bond type perception in molecular mechanical calculations. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 2006, 25, 247–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eberhardt, J.; Santos-Martins, D.; Tillack, A.F.; Forli, S. AutoDock Vina 1.2.0: New docking methods, expanded force field, and Python bindings. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2021, 61, 3891–3898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Conf. | Docking Score | Compd. | Docking Score | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average | Minimal | Average | Minimal | ||

| 1a | −11.874 | −12.110 | 2c | −11.245 | −11.412 |

| 1b | −13.043 | −13.050 | 2d | −11.261 | −11.326 |

| 1c | −12.580 | −12.633 | 3a | −8.679 | −8.677 |

| 1d | −12.478 | −12.486 | 3b | −8.699 | −8.728 |

| 1e | −10.875 | −10.884 | 3c | −9.197 | −9.202 |

| 1f | −10.446 | −10.452 | 3d | −11.831 | −11.858 |

| 2a | −10.485 | −10.629 | 3e | −12.084 | −12.089 |

| 2b | −10.403 | −10.433 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ren, Y.; Yang, P.; Gallucci, J.C.; Wang, C.; Cheng, X.; Wu, S.; Kinghorn, A.D. Rotation Conformational Effects of Selected Cytotoxic Cardiac Glycosides on Their Interactions with Na+/K+-ATPase. Molecules 2025, 30, 4815. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244815

Ren Y, Yang P, Gallucci JC, Wang C, Cheng X, Wu S, Kinghorn AD. Rotation Conformational Effects of Selected Cytotoxic Cardiac Glycosides on Their Interactions with Na+/K+-ATPase. Molecules. 2025; 30(24):4815. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244815

Chicago/Turabian StyleRen, Yulin, Peirun Yang, Judith C. Gallucci, Can Wang, Xiaolin Cheng, Sijin Wu, and A. Douglas Kinghorn. 2025. "Rotation Conformational Effects of Selected Cytotoxic Cardiac Glycosides on Their Interactions with Na+/K+-ATPase" Molecules 30, no. 24: 4815. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244815

APA StyleRen, Y., Yang, P., Gallucci, J. C., Wang, C., Cheng, X., Wu, S., & Kinghorn, A. D. (2025). Rotation Conformational Effects of Selected Cytotoxic Cardiac Glycosides on Their Interactions with Na+/K+-ATPase. Molecules, 30(24), 4815. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244815