Adsorption Performance Assessment of Agro-Waste-Based Biochar for the Removal of Emerging Pollutants from Municipal WWTP Effluent

Abstract

1. Introduction

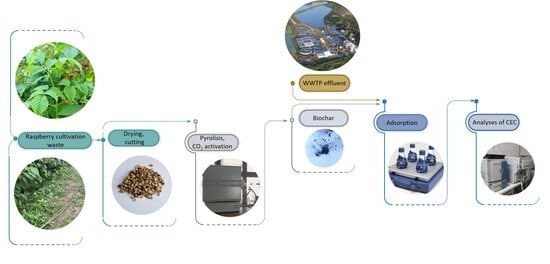

2. Results and Discussion

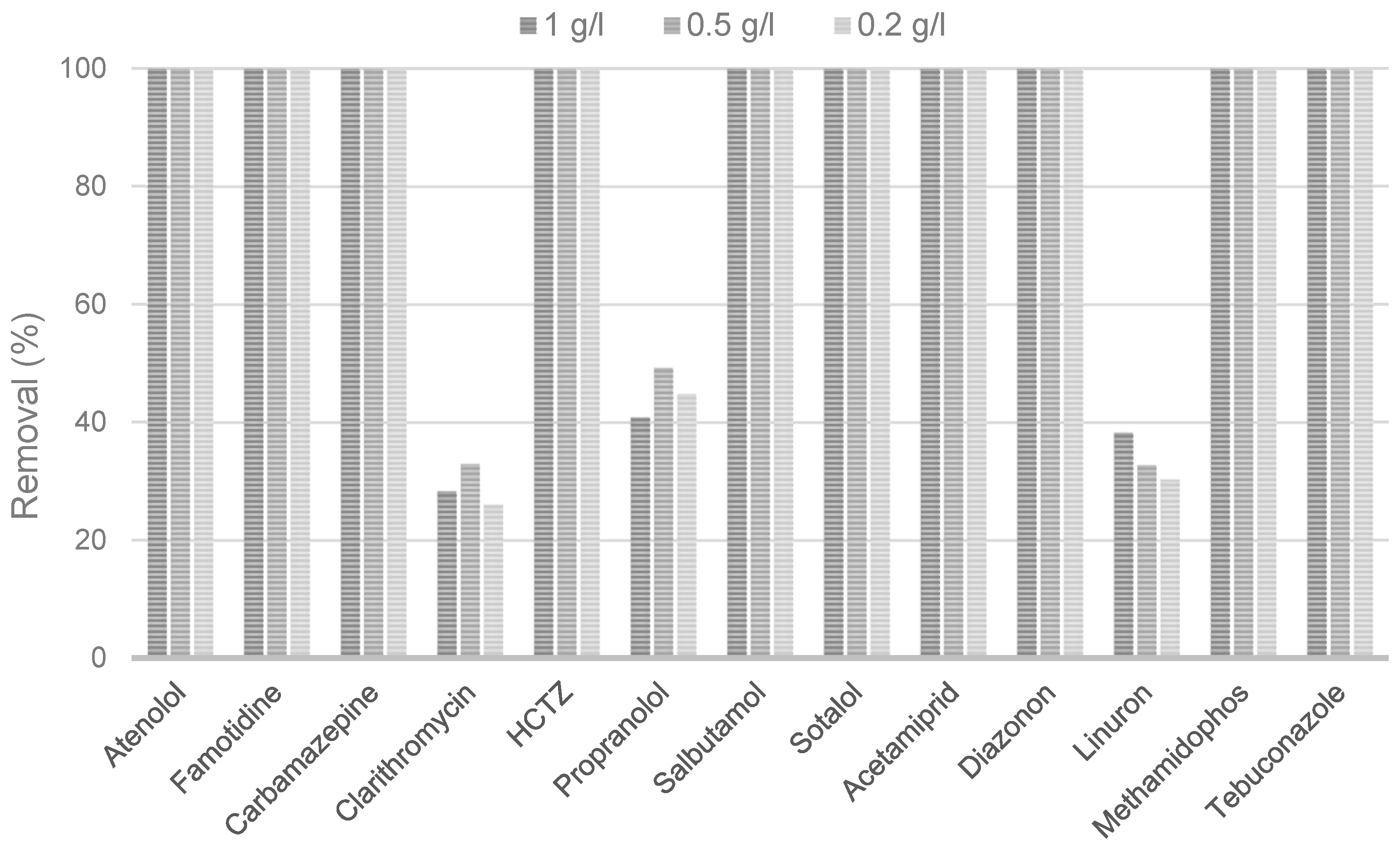

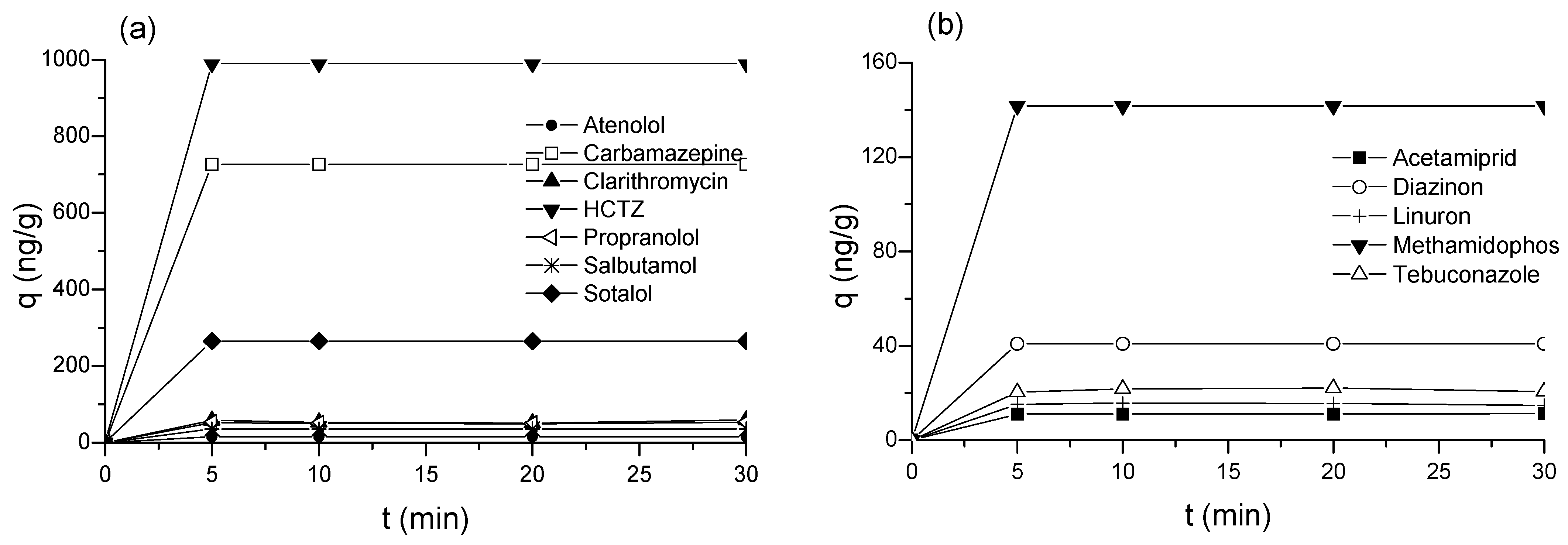

2.1. Adsorption of CECs by Biochar

2.2. Comparative Studies of Biochar and PAC

2.3. Biochar Characterization

2.3.1. Yield of Biochar

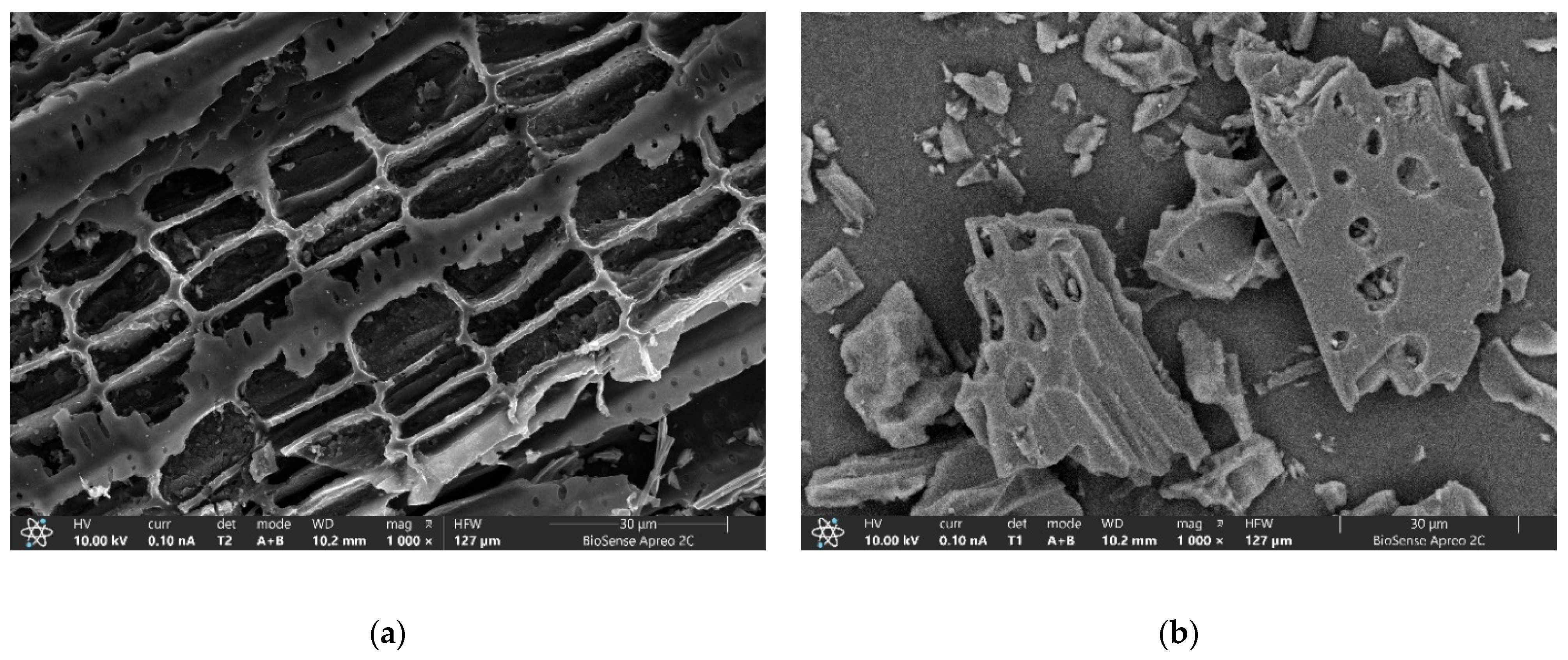

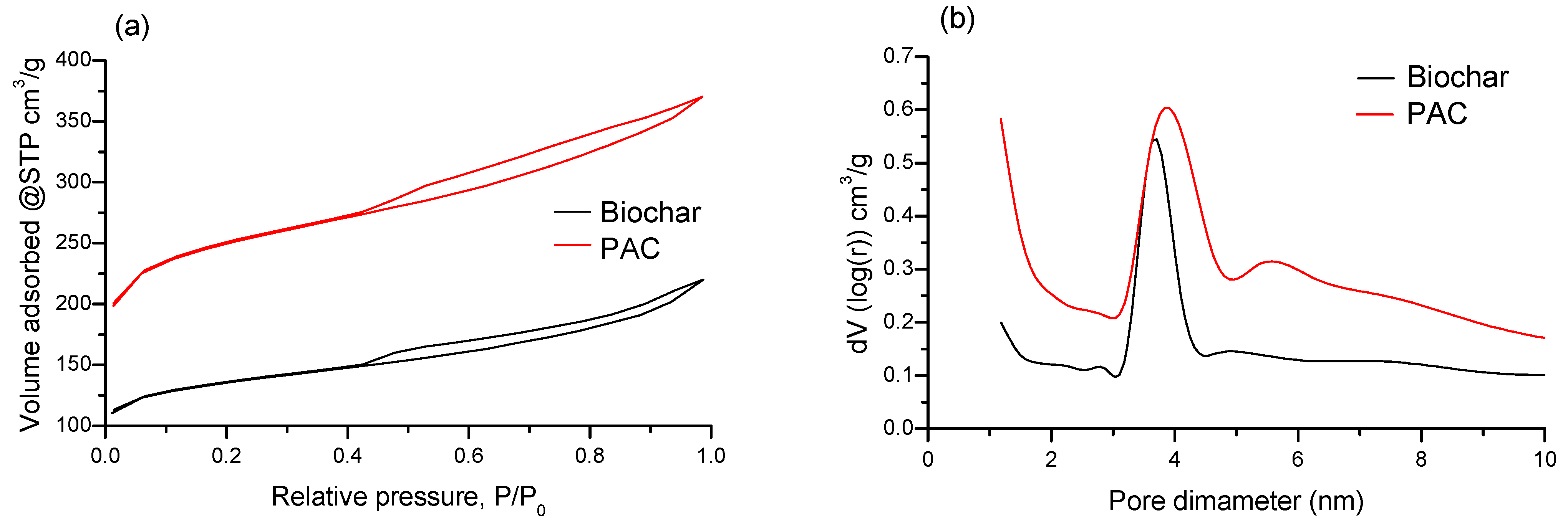

2.3.2. Characterization of Biochar and PAC

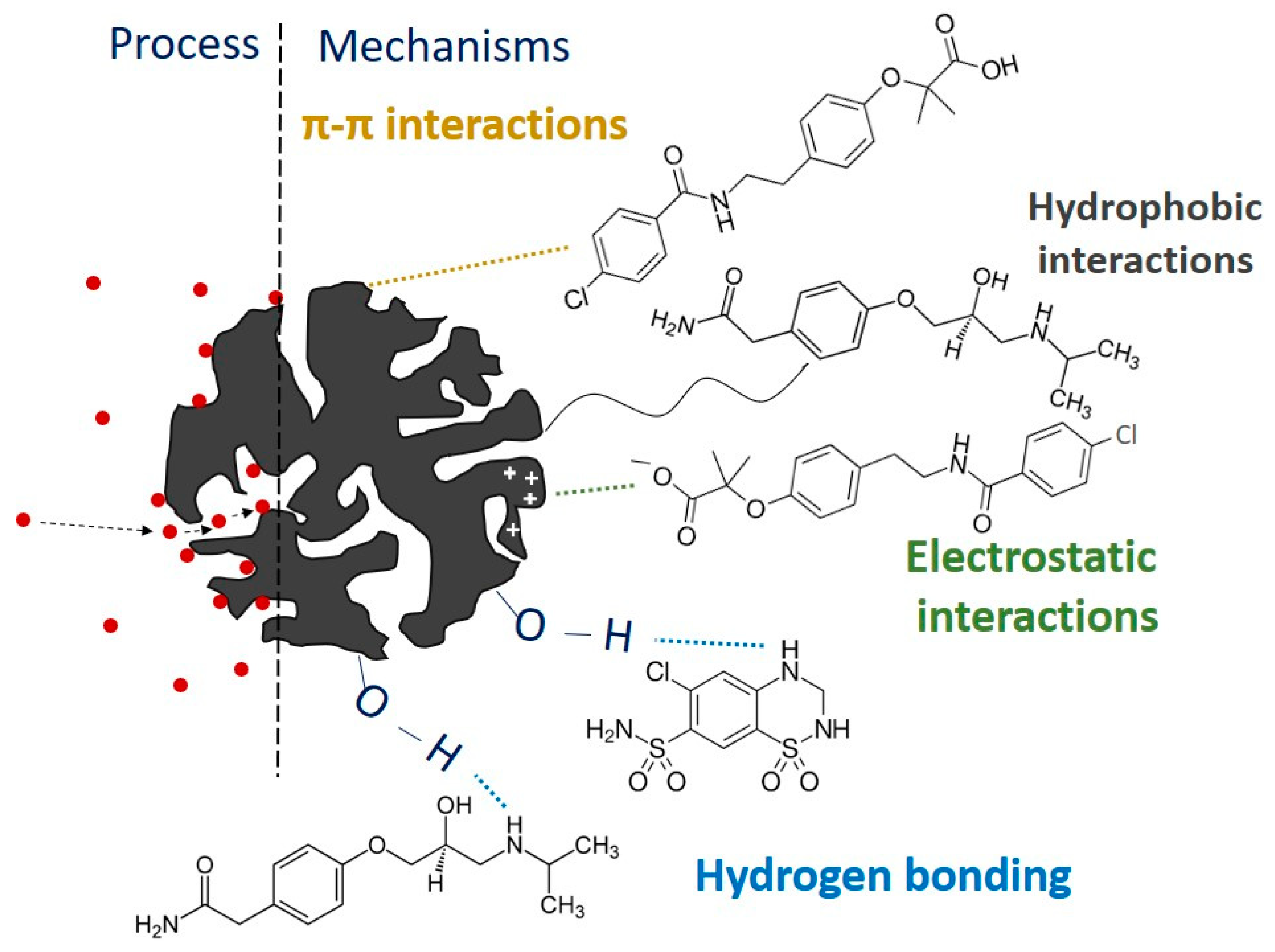

2.4. Adsorption Mechanism of CECs

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Synthesis and Activation of Biochar

3.2. Adsorbent Characterization

3.3. Adsorption Experiments

3.3.1. Wastewater

3.3.2. Batch Adsorption

3.3.3. Sample Preparation for UHPLC–MS/MS

3.3.4. Instrumental Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| WWTPs | Wastewater treatment plants |

| CECs | Contaminants of emerging concern |

| PAC | Powdered activated carbon |

| PhACs | Pharmaceutically active compounds |

| PFAS | poly- and perfluoroalkyl substances |

| AC | Activated carbon |

| MLOQ | Method limit of quantification |

| HCTZ | Hydrochlorothiazide |

| DOC | Dissolved organic carbon |

| SBET | BET specific surface area |

| PV | Pore volume |

| HRSEM | High-resolution scanning electron microscopy |

| EDX | X-ray energy dispersion |

| FTIR | Fourier transform infra-ed spectroscopy |

| BET | Brunauer–Emmett–Teller specific surface |

| CODb | Biodegradable Chemical Oxygen Demand |

| BOD5 | Biological Oxygen Demand |

| UHPLC–MS/MS | high-performance liquid chromatography coupled to triple quadrupole mass spectrometry |

References

- Bilal, M.; Adeel, M.; Rasheed, T.; Zhao, Y.; Iqbal, H.M.N. Emerging contaminants of high concern and their enzyme-assisted biodegradation—A review. Environ. Int. 2019, 124, 336–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkotsis, G.; Nika, M.-C.; Nikolopoulou, V.; Alygizakis, N.; Bizani, E.; Aalizadeh, R.; Badry, A.; Chadwick, E.; Cincinelli, A.; Claßen, D.; et al. Assessment of contaminants of emerging concern in European apex predators and their prey by LC-QToF MS wide-scope target analysis. Environ. Int. 2022, 170, 107623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, D.; Rangabhashiyam, S.; Verma, P.; Singh, P.; Devi, P.; Kumar, P.; Hussain, C.M.; Gaurav, G.K.; Kumar, S. Environmental and health impacts of contaminants of emerging concerns: Recent treatment challenges and approaches. Chemosphere 2021, 272, 129492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gros, M.; Rodríguez-Mozaz, S.; Barceló, D. Rapid analysis of multiclass antibiotic residues and some of their metabolites in hospital, urban wastewater, and river water by ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography coupled to quadrupole linear ion trap tandem mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A 2013, 1292, 173–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaw, S.; Thomas, K.V.; Hutchinson, T.H. Sources, impacts and trends of pharmaceuticals in the marine and coastal environment. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2014, 369, 20130572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Cooper, V.I.; Deng, J.; Amatya, P.L.; Ambrus, D.; Dong, S.; Stalker, N.; Nadeau-Bonilla, C.; Patel, J. Occurrence of pharmaceuticals in Calgary’s wastewater and related surface water. Water Environ. Res. 2015, 87, 414–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Čelić, M.; Gros, M.; Farré, M.; Barceló, D.; Petrović, M. Pharmaceuticals as chemical markers of wastewater contamination in the vulnerable area of the Ebro Delta (Spain). Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 652, 952–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasić, V.; Kukić, D.; Šćiban, M.; Đurišić-Mladenović, N.; Velić, N.; Pajin, B.; Crespo, J.; Farre, M.; Šereš, Z. Lignocellulose-based biosorbents for the removal of contaminants of emerging concern (CECs) from water: A review. Water 2023, 15, 1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Đurišić-Mladenović, N.; Živančev, J.; Antić, I.; Rakić, D.; Buljovčić, M.; Pajin, B.; Llorca, M.; Farre, M. Occurrence of contaminants of emerging concern in different water samples from the lower part of the Danube River Middle Basin—A review. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 363, 125128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llamas-Dios, M.I.; Vadillo, I.; Jiménez-Gavilán, P.; Candela, L.; Corada-Fernández, C. Assessment of a wide array of contaminants of emerging concern in a Mediterranean water basin (Guadalhorce river, Spain): Motivations for an improvement of water management and pollutants surveillance. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 788, 147822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munro, K.; Martins, C.P.; Loewenthal, M.; Comber, S.; Cowan, D.A.; Pereira, L.; Barron, L.P. Evaluation of combined sewer overflow impacts on short-term pharmaceutical and illicit drug occurrence in a heavily urbanised tidal river catchment (London, UK). Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 657, 1099–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ELV—Regulation on Limit Values for Emissions of Pollutants into Waters and Deadlines for Achieving Them. “Official Gazette of RS”, No. 67/2011, 48/2012, 1/2016. Available online: https://www.paragraf.rs/propisi/uredba-granicnim-vrednostima-emisije-zagadjujucih-materija-u-vode.html (accessed on 16 March 2025).

- European Parliament and Council. Directive (EU) 2024/3019 of 27 November 2024 on the treatment of urban waste-water (recast of Directive 91/271/EEC). Off. J. Eur. Union 2024. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=OJ:L_202403019 (accessed on 16 March 2025).

- Rizzo, L.; Malato, S.; Antakyali, D.; Beretsou, V.G.; Đolić, M.B.; Gernjak, W.; Heath, E.; Ivancev-Tumbas, I.; Karaolia, P.; Ribeiro, A.R.L.; et al. Consolidated vs new advanced treatment methods for the removal of contaminants of emerging concern from urban wastewater. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 655, 986–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pistocchi, A.; Alygizakis, N.A.; Brack, W.; Boxall, A.; Cousins, I.T.; Drewes, J.E.; Finckh, S.; Gallé, T.; Launay, M.A.; McLachlan, M.S.; et al. European scale assessment of the potential of ozonation and activated carbon treatment to reduce micropollutant emissions with wastewater. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 848, 157124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggen, R.I.L.; Hollender, J.; Joss, A.; Schärer, M.; Stamm, C. Reducing the discharge of micropollutants in the aquatic environment: The benefits of upgrading wastewater treatment plants. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 7683–7689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagemann, N.; Schmidt, H.-P.; Kägi, R.; Böhler, M.; Sigmund, G.; Maccagnan, A.; McArdell, C.S.; Bucheli, T.D. Wood-based activated biochar to eliminate organic micropollutants from biologically treated wastewater. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 730, 138417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, J.; Riede, P.; Abbt-Braun, G.; Parniske, J.; Metzger, S.; Morck, T. Removal of organic micropollutants from municipal wastewater by powdered activated carbon—Activated sludge treatment. J. Water Process Eng. 2022, 50, 103246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Zhang, N.; Xing, C.; Cui, Q.; Sun, Q.; Zhang, X. The adsorption, regeneration and engineering applications of biochar for removal of organic pollutants: A review. Chemosphere 2019, 223, 12–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaashikaa, P.R.; Senthil Kumar, P.; Varjani, S.; Saravanan, A. A critical review on the biochar production techniques, characterization, stability and applications for circular bioeconomy. Biotechnol. Rep. 2020, 28, e00570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambaye, T.G.; Vaccari, M.; van Hullebusch, E.D.; Amrane, A.; Rtimi, S. Mechanisms and adsorption capacities of biochar for the removal of organic and inorganic pollutants from industrial wastewater. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 18, 3273–3294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamović, A.; Petronijević, M.; Panić, S.; Cvetković, D.; Antić, I.; Petrović, Z.; Đurišić-Mladenović, N. Biochar and hydrochar as adsorbents for the removal of contaminants of emerging concern from wastewater. Adv. Technol. 2023, 12, 57–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Chen, T.; Huang, Q.; Zhan, M.; Li, X.; Yan, J. Activation of persulfate by CO2-activated biochar for improved phenolic pollutant degradation: Performance and mechanism. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 380, 122519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukić, D.; Ivanovska, A.; Vasić, V.; Lađarević, J.; Kostić, M.; Šćiban, M. The overlooked potential of raspberry canes: From waste to an efficient low-cost biosorbent for Cr(VI) ions. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2024, 14, 4605–4619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- eKapija. Thousands of Kilowatts Remain in Orchards—Production of Pellets and Briquettes from Nuts Increases the Price of Raspberries by 7%. Available online: https://www.ekapija.com/where-to-invest/2152201/hiljade-kilovata-ostaje-u-vocnjacima-proizvodnja-peleta-i-briketa-od-orezina-uvecava (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Das, S.; Ray, N.M.; Wan, J.; Khan, A.; Chakraborty, T.; Ray, M.B. Micropollutants in wastewater: Fate and removal processes. In Physico-Chemical Wastewater Treatment and Resource Recovery; Farooq, R., Ahmad, Z., Eds.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, C.; Zhang, H.; Xia, M.; Lei, W.; Wang, F. The single/co-adsorption characteristics and microscopic adsorption mechanism of biochar-montmorillonite composite adsorbent for pharmaceutical emerging organic contaminant atenolol and lead ions. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2020, 187, 109763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naghdi, M.; Taheran, M.; Pulicharla, R.; Rouissi, T.; Brar, S.K.; Verma, M.; Surampalli, R.Y. Pine-wood derived nanobiochar for removal of carbamazepine from aqueous media: Adsorption behavior and influential parameters. Arab. J. Chem. 2019, 12, 5292–5301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, G.; Zhao, J.; Liu, Y.; Lang, D.; Wu, M.; Pan, B.; Steinberg, C.E.W. The relative importance of different carbon structures in biochars to carbamazepine and bisphenol A sorption. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 373, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baharum, N.A.; Nasir, H.M.; Ishak, M.Y.; Isa, N.M.; Hassan, M.A.; Aris, A.Z. Highly efficient removal of diazinon pesticide from aqueous solutions by using coconut shell-modified biochar. Arab. J. Chem. 2020, 13, 6106–6121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moussavi, G.; Hosseini, H.; Alahabadi, A. The investigation of diazinon pesticide removal from contaminated water by adsorption onto NH4Cl-induced activated carbon. Chem. Eng. J. 2013, 214, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Sun, H.; Liu, Y.; Wang, X.; Valizadeh, K. The sorption of Tebuconazole and Linuron from an aqueous environment with a modified sludge-based biochar: Effect, mechanisms, and its persistent free radicals study. J. Chem. 2021, 2021, 2912054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraes, L.E.Z.d.; Marcoti, F.A.O.; Lucio, M.A.N.; Rocha, B.C.d.S.; Rocha, L.B.; Romero, A.L.; Bona, E.; Peron, A.P.; Junior, O.V. Analysis and simulation of adsorption efficiency of herbicides Diuron and Linuron on activated carbon from spent coffee beans. Processes 2024, 12, 1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, M.; He, L.; Jiang, M.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, J.; Gustave, W.; Wang, S.; Deng, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Z. Biochar for the removal of emerging pollutants from aquatic systems: A review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gidstedt, S.; Betsholtz, A.; Falås, P.; Cimbritz, M.; Davidsson, Å.; Micolucci, F.; Svahn, O. A comparison of adsorption of organic micropollutants onto activated carbon following chemically enhanced primary treatment with microsieving, direct membrane filtration, and tertiary treatment of municipal wastewater. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 811, 152225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sousa, A.F.C.; Gil, M.V.; Calisto, V. Upcycling spent brewery grains through the production of carbon adsorbents—Application to the removal of carbamazepine from water. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 36463–36475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diniz, V.; Cunha, D.G.; Rath, S. Adsorption of recalcitrant contaminants of emerging concern onto activated carbon: A laboratory and pilot-scale study. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 325, 116489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Yao, B.; Yang, X.; Wang, L.; Xu, Z.; Yan, X.; Tian, L.; Zhou, H.; Zhou, Y. Novel insights into the adsorption of organic contaminants by biochar: A review. Chemosphere 2022, 287 Pt 2, 132113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, K.M.; Rover, M.; Brown, R.C.; Bai, X.; Wen, Z.; Jarboe, L.R. Recovery and utilization of lignin monomers as part of the biorefinery approach. Energies 2016, 9, 808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahya, M.A.; Al-Qodah, Z.; Ngah, C.W.Z. Agricultural bio-waste materials as potential sustainable precursors used for activated carbon production: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 46, 218–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grisales-Cifuentes, C.M.; Serna Galvis, E.A.; Porras, J.; Flórez, E.; Torres-Palma, R.A.; Acelas, N. Kinetics, isotherms, effect of structure, and computational analysis during the removal of three representative pharmaceuticals from water by adsorption using a biochar obtained from oil palm fiber. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 326, 124753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozyatnyk, I.; Oesterle, P.; Wurzer, C.; Mašek, O.; Jansson, S. Removal of contaminants of emerging concern from multicomponent systems using carbon dioxide activated biochar from lignocellulosic feedstocks. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 340, 125561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, S.; Bobde, K.; Aikat, K.; Halder, G. Biosorptive uptake of ibuprofen by steam activated biochar derived from mung bean husk: Equilibrium, kinetics, thermodynamics, modeling, and eco-toxicological studies. J. Environ. Manag. 2016, 182, 581–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Li, Z.; Wang, P.; Bai, W.; Wang, H. Aquatic plant-derived biochars produced in different pyrolytic conditions: Spectroscopic studies and adsorption behavior of diclofenac sodium in water media. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2020, 17, 100275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srikhaow, A.; Win, E.E.; Amornsakchai, T.; Kiatsiriroat, T.; Kajitvichyanukul, P.; Smith, S.M. Biochar derived from pineapple leaf non-fibrous materials and its adsorption capability for pesticides. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 26147–26157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coimbra, R.N.; Calisto, V.; Ferreira, C.I.A.; Esteves, V.I.; Otero, M. Removal of pharmaceuticals from municipal wastewater by adsorption onto pyrolyzed pulp mill sludge. Arab. J. Chem. 2019, 12, 3611–3620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, C.P.; Jaria, G.; Otero, M.; Esteves, V.I.; Calisto, V. Adsorption of pharmaceuticals from biologically treated municipal wastewater using paper mill sludge-based activated carbon. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 13173–13184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruhl, A.S.; Zietzschmann, F.; Hilbrandt, I.; Meinel, F.; Altmann, J.; Sperlich, A.; Jekel, M. Targeted testing of activated carbons for advanced wastewater treatment. Chem. Eng. J. 2014, 257, 184–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kårelid, V.; Larsson, G.; Björlenius, B. Pilot-scale removal of pharmaceuticals in municipal wastewater: Comparison of granular and powdered activated carbon treatment at three wastewater treatment plants. J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 193, 491–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margot, J.; Kienle, C.; Magnet, A.; Weil, M.; Rossi, L.; De Alencastro, L.F.; Abegglen, C.; Thonney, D.; Chèvre, N.; Schärer, M.; et al. Treatment of micropollutants in municipal wastewater: Ozone or powdered activated carbon? Sci. Total Environ. 2013, 461, 480–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mailler, R.; Gasperi, J.; Coquet, Y.; Derome, C.; Buleté, A.; Vulliet, E.; Bressy, A.; Varrault, G.; Chebbo, G.; Rocher, V. Removal of emerging micropollutants from wastewater by activated carbon adsorption: Experimental study of different activated carbons and factors influencing the adsorption of micropollutants in wastewater. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2016, 4, 1102–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stylianou, M.; Christou, A.; Michael, C.; Agapiou, A.; Papanastasiou, P.; Fatta-Kassinos, D. Adsorption and removal of seven antibiotic compounds present in water with the use of biochar derived from the pyrolysis of organic waste feedstocks. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 105868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheorghe-Bulmau, C.; Volceanov, A.; Stanciulescu, I.; Ionescu, G.; Marculescu, C.; Radoiu, M. Production and properties assessment of biochars from rapeseed and poplar waste biomass for environmental applications in Romania. Environ. Geochem. Health 2022, 44, 1683–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amalina, A.; Abd Razak, A.S.; Krishnan, S.; Zularisam, A.W.; Nasrullah, M. A comprehensive assessment of the method for producing biochar, its characterization, stability, and potential applications in regenerative economic sustainability—A review. Clean. Mater. 2022, 3, 100045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safarian, S. Performance analysis of sustainable technologies for biochar production: A comprehensive review. Energy Rep. 2023, 9, 4574–4593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khajavi-Shojaei, S.; Moezzi, A.; Norouzi Masir, M.; Taghavi, M. Characteristics of conocarpus wastes and common reed biochars as a predictor of potential environmental and agronomic applications. Energy Sources Part A 2020, 42, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowell, S.; Shields, J.E.; Thomas, M.A.; Thommes, M. Characterization of Porous Solids and Powders: Surface Area, Pore Size, and Density; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2004; Volume 16. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, M.; Li, C.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, S.; Hu, X. In situ characterization of functional groups of biochar in pyrolysis of cellulose. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 799, 149354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janu, R.; Mrlik, V.; Ribitsch, D.; Hofman, J.; Sedláček, P.; Bielská, L.; Soja, G. Biochar surface functional groups as affected by biomass feedstock, biochar composition and pyrolysis temperature. Carbon Resour. Convers. 2021, 4, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.T.; Tran, H.N.; Juang, R.-S.; Dat, N.D.; Tomul, F.; Ivanets, A.; Woo, S.H.; Hosseini-Bandegharaei, A.; Nguyen, V.P.; Chao, H.-P. Adsorption process and mechanism of acetaminophen onto commercial activated carbon. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 104408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terzyk, A.P. The influence of activated carbon surface chemical composition on the adsorption of acetaminophen (paracetamol) in vitro: Part II. TG, FTIR, and XPS analysis of carbons and the temperature dependence of adsorption kinetics at the neutral pH. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2001, 177, 23–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajjadi, B.; Chen, W.; Egiebor, N. A comprehensive review on physical activation of biochar for energy and environmental applications. Rev. Chem. Eng. 2019, 35, 735–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paunovic, O.; Pap, S.; Maletic, S.; Taggart, M.A.; Boskovic, N.; Turk Sekulic, M. Ionisable emerging pharmaceutical adsorption onto microwave functionalised biochar derived from novel lignocellulosic waste biomass. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2019, 547, 350–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baccar, R.; Sarrà, M.; Bouzid, J.; Feki, M.; Blánquez, P. Removal of pharmaceutical compounds by activated carbon prepared from agricultural by-product. Chem. Eng. J. 2012, 211–212, 310–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čadková, E.; Komárek, M.; Kaliszová, R.; Száková, J.; Vaněk, A.; Bordas, F.; Bollinger, J.C. The influence of copper on tebuconazole sorption onto soils, humic substances, and ferrihydrite. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2013, 20, 4205–4215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauletto, P.S.; Lütke, S.F.; Dotto, G.L.; Salau, N.P.G. Adsorption mechanisms of single and simultaneous removal of pharmaceutical compounds onto activated carbon: Isotherm and thermodynamic modeling. J. Mol. Liq. 2021, 336, 116203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Zhao, H.; Peng, Q.; Chen, G.; Liu, J.; Cao, X.; Xiong, S.; Li, G.; Liu, Q. Elimination of Pharmaceutical Compounds from Aqueous Solution through Novel Functionalized Pitch-Based Porous Adsorbents: Kinetic, Isotherm, Thermodynamic Studies and Mechanism Analysis. Molecules 2024, 29, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burdová, A.; Brázová, V.; Kwoczynski, Z.; Snow, J.; Trögl, J.; Kříženecká, S. Miscanthus x giganteus biochar: Effective adsorption of pharmaceuticals from model solution and hospital wastewater. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 460, 142545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, H.N.; Wang, Y.-F.; You, S.-J.; Chao, H.-P. Insights into the mechanism of cationic dye adsorption on activated charcoal: The importance of π-π interactions. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2017, 107, 168–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.; Sadiq, S.; Wu, P.; Humayun, M.; Ullah, S.; Yaseen, W.; Khan, S.; Khan, A.; Abumousa, R.A.; Bououdina, M. Synergizing black gold and light: A comprehensive analysis of biochar-photocatalysis integration for green remediation. Carbon Capture Sci. Technol. 2024, 13, 100315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, A.; Patra, B.R.; Podder, J.; Dalai, A.K. Synthesis of biochar from lignocellulosic biomass for diverse industrial applications and energy harvesting: Effects of pyrolysis conditions on the physicochemical properties of biochar. Front. Mater. 2022, 9, 870184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thongsamer, T.; Vinitnantharat, S.; Pinisakul, A.; Werner, D. Chitosan impregnation of coconut husk biochar pellets improves their nutrient removal from eutrophic surface water. Sustain. Environ. Res. 2022, 32, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrović, M.; Škrbić, B.; Živančev, J.; Ferrando-Climent, L.; Barcelo, D. Determination of 81 pharmaceutical drugs by high performance liquid chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry with hybrid triple quadrupole-linear ion trap in different types of water in Serbia. Sci. Total Environ. 2014, 468–469, 415–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Commission for the Protection of the Danube River. Joint Danube Survey 4: A Comprehensive Assessment of the Danube River Basin. 2019. Available online: https://www.icpdr.org/publications/danube-watch-2-2019-joint-danube-survey-4 (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Gros, M.; Rodríguez-Mozaz, S.; Barceló, D. Fast and comprehensive multi-residue analysis of a broad range of human and veterinary pharmaceuticals and some of their metabolites in surface and treated waters by ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography coupled to quadrupole-linear ion trap tandem mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A 2012, 1248, 104–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakić, D.; Antić, I.; Živančev, J.; Buljovčić, M.; Šereš, Z.; Đurišić-Mladenović, N. Solid-phase extraction as promising sample preparation method for compound of emerging concerns analysis. Analecta Tech. Szeged. 2023, 17, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PubChem. National Center for Biotechnology Information. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- DrugBank; Wishart, D.S.; Knox, C.; Guo, A.C.; Shrivastava, S.; Hassanali, M.; Stothard, P.; Chang, Z.; Woolsey, J. DrugBank: A Comprehensive Resource for in Silico drug Discovery and Exploration. Available online: https://go.drugbank.com (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Fér, M.; Kodešová, R.; Golovko, O.; Schmidtová, Z.; Klement, A.; Nikodem, A.; Kočárek, M.; Grabic, R. Sorption of atenolol, sulfamethoxazole and carbamazepine onto soil aggregates from the illuvial horizon of the Haplic Luvisol on loess. Soil Water Res. 2018, 13, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ChemicalBook. Available online: https://www.chemicalbook.com (accessed on 15 March 2025).

| CEC * (ng/L) | Campaign | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Influent | I | II | III | IV | V | |

| Effluent | Effluent | Effluent | Effluent | Effluent | ||

| Atenolol | 0.50 | 19.4 | 458 | 15.3 | 39.2 | 54.1 |

| Bezafibrate | <MLOQ | <MLOQ | <MLOQ | <MLOQ | 275 | <MLOQ |

| Carbamazepine | 161 | 319 | 177 | 726 | 507 | 413 |

| Clarithromycin | 82.3 | 75.3 | 218 | 115 | 60.9 | 46.9 |

| Famotidine | 6.23 | 27.5 | <MLOQ | <MLOQ | 11.8 | 18.1 |

| Furosemide | 294 | <MLOQ | 955 | <MLOQ | <MLOQ | <MLOQ |

| HCTZ (hydrochlorthiazide) | 574 | 816 | 1127 | 992 | 803 | 1459 |

| Losartan | 389 | <MLOQ | 382 | <MLOQ | <MLOQ | <MLOQ |

| Propranolol | <MLOQ | 78.1 | 1767 | 93.4 | 61.0 | 83.5 |

| Ranitidine | <MLOQ | <MLOQ | <MLOQ | <MLOQ | 54.6 | <MLOQ |

| Salbutamol | <MLOQ | 37.5 | <MLOQ | 36.1 | 49.7 | 47.5 |

| Sotalol | 178 | 310 | 321 | 265 | 589 | 481 |

| Acetamiprid | <MLOQ | 35.6 | <MLOQ | 35.3 | 54.1 | 188 |

| Diazinon | <MLOQ | 32.9 | <MLOQ | 45.9 | 54.6 | 66.5 |

| Linuron | <MLOQ | 68.7 | <MLOQ | 58.8 | 51.5 | 55.2 |

| Methamidophos | <MLOQ | 119 | <MLOQ | 146 | <MLOQ | 91.7 |

| Tebuconazole | <MLOQ | 49.2 | <MLOQ | 58.5 | 98.2 | <MLOQ |

| CEC | Campaign I | Removal (%) * | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C0 (ng/L) | pH 6 | pH 7 | pH 8 | Original pH | |

| Atenolol | 19.4 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Carbamazepine | 319 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Clarithromycin | 75.3 | 33.9 | 30.3 | 36.2 | 36.5 |

| Famotidine | 27.5 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| HCTZ | 816 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Propranolol | 78.1 | 35.1 | 37.3 | 47 | 38.8 |

| Salbutamol | 37.5 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Sotalol | 310 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Acetamiprid | 35.6 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Diazinon | 32.9 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Linuron | 68.7 | 37.1 | 34.2 | 36.2 | 35.8 |

| Methamidophos | 119 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Tebuconazole | 49.2 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| CEC | Campaign II C0, (ng/L) | Removal (%) * | Campaign III C0, (ng/L) | Removal (%) * |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atenolol | 458 | 100 | 15.3 | 100 |

| Carbamazepine | 177 | 100 | 726 | 100 |

| Clarithromycin | 218 | 43.7 | 115 | 48.9 |

| Furosemide | 955 | 100 | <MLOQ | / |

| HCTZ | 1127 | 96.6 | 992 | 100 |

| Losartan | 382 | 100 | <MLOQ | / |

| Propranolol | 1767 | 42.3 | 93.4 | 52.7 |

| Salbutamol | <MLOQ | / | 36.1 | 100 |

| Sotalol | 321 | 97.7 | 265 | 100 |

| Acetamiprid | <MLOQ | / | 35.3 | 100 |

| Diazinon | <MLOQ | / | 45.9 | 100 |

| Linuron | <MLOQ | / | 58.8 | 26.9 |

| СEС | Campaign IV | Spiked Effluent | |

|---|---|---|---|

| C0 (ng/L) | Concentration Range (ng/L) | Removal * (%) | |

| Atenolol | 39.2 | 1605–7589 | 99.5–100 |

| Bezafibrate | 275 | 850–3533 | 72.6–91.5 |

| Famotidine | 11.8 | 927–4282 | 100 |

| HCTZ | 803 | 1544–5705 | 100 |

| Carbamazepine | 507 | 1467–4566 | 100 |

| Clarithromycin | 60.9 | 927–5787 | 96.2–100 |

| Propranolol | 61 | 893–5841 | 91.6–100 |

| Ranitidine | 54.6 | 947–3998 | 93.8–100 |

| Salbutamol | 49.7 | 1358–6928 | 97.9–100 |

| Sotalol | 589 | 2052–7552 | 100 |

| Acetamiprid | 54.1 | 745–3557 | 93–100 |

| Diazinon | 54.6 | 1499–4638 | 94.7–100 |

| Methamidophos | ˂MLOQ | 158–208 | 100 |

| Linuron | 51.5 | 796–3094 | 100 |

| Tebuconazol | 98.2 | 1751–4386 | 100 |

| Acetaminophen | ˂MLOQ | 1333–4831 | 100 |

| Diltiazem | ˂MLOQ | 172–761 | 80–97 |

| Dimethoate | ˂MLOQ | 542–2165 | 100 |

| Ethopropohos | ˂MLOQ | 1606–5518 | 100 |

| Furosemide | ˂MLOQ | 1294–3996 | 100 |

| Imazalil | ˂MLOQ | 389–1080 | 100 |

| Carbofuran | ˂MLOQ | 205–784 | 100 |

| Losartan | ˂MLOQ | 579–2402 | 93.3–100 |

| Methidation | ˂MLOQ | 506–2305 | 100 |

| Omethoate | ˂MLOQ | 114–306 | 100 |

| Propioconazole | ˂MLOQ | 2334–5831 | 100 |

| СEС | Biochar | PAC | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Removal * (%) | Removal * (%) | |||||

| C0 (ng/L) | 24 h | 45 min | C0 (ng/L) | 24 h | 45 min | |

| Atenolol | 19.4 | 100 | 100 | 39.2 | 97.4 | 96.1 |

| Carbamazepine | 319.1 | 100 | 100 | 507 | 100 | 100 |

| Clarithromycin | 75.3 | 36.6 | 28.5 | 60.9 | 59.1 | 68.8 |

| Famotidine | 27.5 | 100 | 100 | 11.8 | 100 | 100 |

| HCTZ | 816 | 100 | 99.6 | 803 | 100 | 100 |

| Propranolol | 78.1 | 38.8 | 45.9 | 61 | 42.7 | 47.9 |

| Salbutamol | 37.5 | 100 | 100 | 49.7 | 46.6 | 45.1 |

| Sotalol | 310 | 100 | 100 | 58.9 | 100 | 100 |

| Acetamiprid | 35.6 | 100 | 100 | 54.1 | 100 | 100 |

| Diazonon | 32.9 | 100 | 100 | 54.6 | 100 | 100 |

| Linuron | 68.7 | 35.8 | 38.6 | 51.5 | 100 | 100 |

| Methanidophos | 119 | 100 | 100 | 15.1 | 100 | 100 |

| Tebuconazol | 49.2 | 100 | 100 | 98.2 | 100 | 100 |

| Feedstock | Biochar | CEC | Adsorption | Ref. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kinetics | Equilibrium | |||||

| Time | Conditions | Removal (%) | ||||

| Pinewood | 525 °C 20 min Nonactivated SBET 47.25 m2/g | Carbamazepine | 48 h | Single solution (0.5–20 ng/mL) Dose: 0.25 g/L, pH 6 | 70–99 | [28] |

| Raspberry-based biochar | 700 °C, 2 h CO2 activated SBET 450 m2/g | Carbamazepine | ~5 min | WWTP effluent (1467–4566 ng/L) Dose: 1 g/L, Original pH | 100 | This study |

| Biosolids (WWTP) | 550 °C, 1.5 h Nonactivated SBET 3.98 m2/g | Clarithromycin | ~15 min | Solution (105 ng/L) (7 antibiotics mixture) Dose: 5–100 g in 1 L, pH 8.33 | 70–80 | [52] |

| Cattle manure | 550 °C, 1.5 h Nonactivated SBET 11.48 m2/g | ~80 min | Single solution (105 ng/L) (7 antibiotics mixture) Dose: 5–100 g in 1 L, pH 9.96 | 80–90 | ||

| Spent coffee grounds | 550 °C 1.5 h Nonactivated SBET 1.53 m2/g | ~5 min | Single solution (105 ng/L) (7 antibiotics mixture) Dose: 5–100 g in 1 L, pH 8.27 | 90 | ||

| Raspberry-based biochar | 700 °C, 2 h CO2 activated SBET 450 m2/g | Clarithromycin | ~5 min | WWTP effluent (927–5787 ng/L) Dose: 1 g/L, Original pH | 96–100 | This study |

| Pineapple leaf non-fibrous material | 550 °C, 2 h n.a. SBET 4.65 m2/g PV 0.0097 cm3/g | Acetamiprid | ~200 min | Single solution (107–2·108 ng/L) Dose: 5 g/L, pH 7 | 84 | [45] |

| Carbonized coconut shell | 700 °C, 2 h Nonactivated SBET 434.8 m2/g PV 0.174 cm3/g | Diazinon | n.a. | Single solution (106 ng/L) Dose: 2·106 ng/L, pH 7, 2 h | >90 | [30] |

| 700 °C, 2 h H3PO4 SBET 508 m2/g PV 0.203 cm3/g | n.a. | Single solution (106 ng/L) Dose: 2·106 ng/L, pH 7, 2 h | >90 | |||

| 700 °C, 2 h NaOH SBET 405.9 m2/g PV 0.162 cm3/g | n.a. | Single solution (106 ng/L) Dose: 2·106 ng/L, pH 7, 2 h | >90 | |||

| Raspberry-based biochar | 700 °C, 2 h CO2 activated SBET 450 m2/g | Diazinon | ~5 min | WWTP effluent (1499–4638 ng/L) Dose: 1 g/L, Original pH | 94.7–100 | This study |

| C (wt%) | O (wt%) | Mg (wt%) | P (wt%) | K (wt%) | Ca (wt%) | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biochar | 60.9 | 18.9 | 3.1 | 1.3 | 6.5 | 9.3 | 100 |

| PAC | 97.9 | 2.1 | - | - | - | - | 100 |

| Annual Average | ELV [12] (Discharge into Receiving Body) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Value | Removal (%) | Emission Limit Values | Requested Removal (%) |

| Suspended solids (mg/L) | 5–10.1 | 97–98 | 35 (mg/L) | 90 |

| pH | 6.8–8.1 | - | 6–9 | - |

| COD (mg O2/L) | 27–36 | 96 | 125 (mg/L) | 75 |

| BOD5 (mg O2/L) | 3–5.2 | 98–99 | 25 (mg/L) | 70–90 |

| Total nitrogen (mg/L) | 5.7–7.2 | 89–92 | 10 mg/L | 70–80 |

| Total phosphorus (mg/L) | 0.51–1 | 93–95 | 1 mg/L | 80 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lukić, D.; Vasić, V.; Živančev, J.; Antić, I.; Panić, S.; Petronijević, M.; Đurišić-Mladenović, N. Adsorption Performance Assessment of Agro-Waste-Based Biochar for the Removal of Emerging Pollutants from Municipal WWTP Effluent. Molecules 2025, 30, 4803. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244803

Lukić D, Vasić V, Živančev J, Antić I, Panić S, Petronijević M, Đurišić-Mladenović N. Adsorption Performance Assessment of Agro-Waste-Based Biochar for the Removal of Emerging Pollutants from Municipal WWTP Effluent. Molecules. 2025; 30(24):4803. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244803

Chicago/Turabian StyleLukić, Dragana, Vesna Vasić, Jelena Živančev, Igor Antić, Sanja Panić, Mirjana Petronijević, and Nataša Đurišić-Mladenović. 2025. "Adsorption Performance Assessment of Agro-Waste-Based Biochar for the Removal of Emerging Pollutants from Municipal WWTP Effluent" Molecules 30, no. 24: 4803. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244803

APA StyleLukić, D., Vasić, V., Živančev, J., Antić, I., Panić, S., Petronijević, M., & Đurišić-Mladenović, N. (2025). Adsorption Performance Assessment of Agro-Waste-Based Biochar for the Removal of Emerging Pollutants from Municipal WWTP Effluent. Molecules, 30(24), 4803. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244803