1. Introduction

With the acceleration of global industrialization, the effective treatment of organic pollutants, such as dye-contaminated wastewater, has become a significant challenge in environmental science. Within the broad spectrum of wastewater remediation approaches, photocatalytic oxidation is recognized as one of the most promising approaches for water pollution control due to its capacity to utilize solar energy for the thorough mineralization of pollutants, alongside its inherent environmental compatibility and sustainability [

1,

2]. Among semiconductor photocatalysts, ZnO has attracted considerable attention due to its superior photocatalytic performance, excellent chemical stability, and low cost [

3,

4]. However, its practical application is hindered by two primary limitations: (i) the rapid recombination of photogenerated e

−–h

+ pairs, which substantially diminishes quantum efficiency [

5], and (ii) the aggregation of nanoscale particles, which significantly impairs the accessibility of active sites and mass transfer kinetics [

6].

To address these limitations, a synergistic modification approach that integrates carrier confinement with elemental doping has been developed [

7,

8,

9]. Ordered mesoporous silica SBA-15 is an exemplary support for confining metal oxide nanoparticles due to its highly regular 2D hexagonal pore structure (5–10 nm), exceptionally large surface area (>600 m

2 g

−1), and significant thermal stability [

10,

11,

12]. This distinctive pore confinement effect not only effectively inhibits the aggregation and leaching of active components but also preserves efficient mass transfer pathways. This strategy has been demonstrated to be effective in various catalytic systems, including TiO

2 and Fe

2O

3 [

13,

14,

15].

Concurrently, doping with rare-earth elements constitutes an effective strategy for modifying the electronic structures of semiconductors. This approach enhances optoelectronic properties by introducing defect energy levels and altering local charge distributions [

16]. La, a representative rare-earth element, has been demonstrated to extend the visible-light absorption range of ZnO and inhibit carrier recombination through the formation of electron trapping centers, thereby improving overall photocatalytic efficiency [

8,

17].

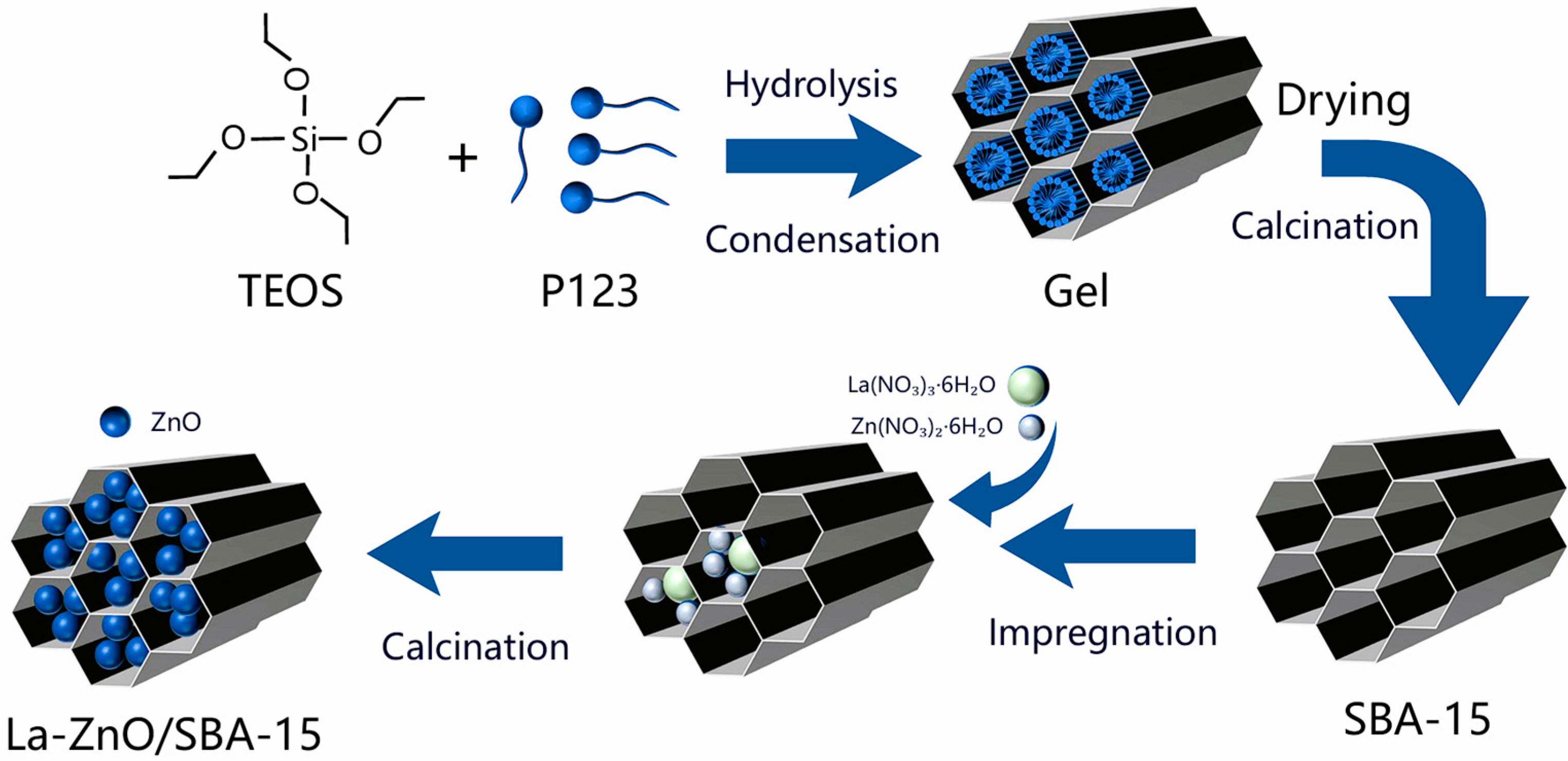

Building upon this foundation, the research synthesized La-ZnO/SBA-15 composite photocatalysts using an impregnation–calcination method to improve light absorption and charge separation by confining La-doped ZnO nanoclusters within the mesopores of SBA-15. Comprehensive characterization techniques, including X-ray diffraction (XRD), transmission electron microscopy (TEM), Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR), and N2 adsorption–desorption analysis, were employed alongside Rhodamine B (RhB) degradation experiments, kinetic analyses, and radical trapping studies. These investigations demonstrated that the La doping ratio significantly impacts photocatalytic activity. Importantly, the confined active species (e−, h+, ·OH, and ·O2−) engage in synergistic oxidation pathways during RhB degradation. This study provides a viable design framework for high-performance, recyclable mesopore-confined photocatalysts with significant potential applications in environmental remediation.

2. Results

2.1. Analysis of Structure and Composition via XRD

Figure 1 illustrates the small-angle X-ray diffraction (SAXRD) patterns of the synthesized SBA-15 support, ZnO/SBA-15, and 5% La-doped ZnO/SBA-15 composites. The SBA-15 material exhibits three diffraction peaks at 2θ values of 0.84°, 1.45°, and 1.68°, which correspond to the (100), (110), and (200) reflections characteristic of highly ordered hexagonal mesoporous silica SBA-15 [

10]. The SAXRD patterns of both ZnO/SBA-15 and 5% La-doped ZnO/SBA-15 exhibit identical characteristic peaks, confirming that the hexagonal mesostructure remains intact following impregnation and calcination. This observation demonstrates that the incorporation of ZnO and subsequent La doping does not disrupt the 2D hexagonal mesoscopic order, thereby highlighting the excellent thermal stability of SBA-15 as a catalyst support.

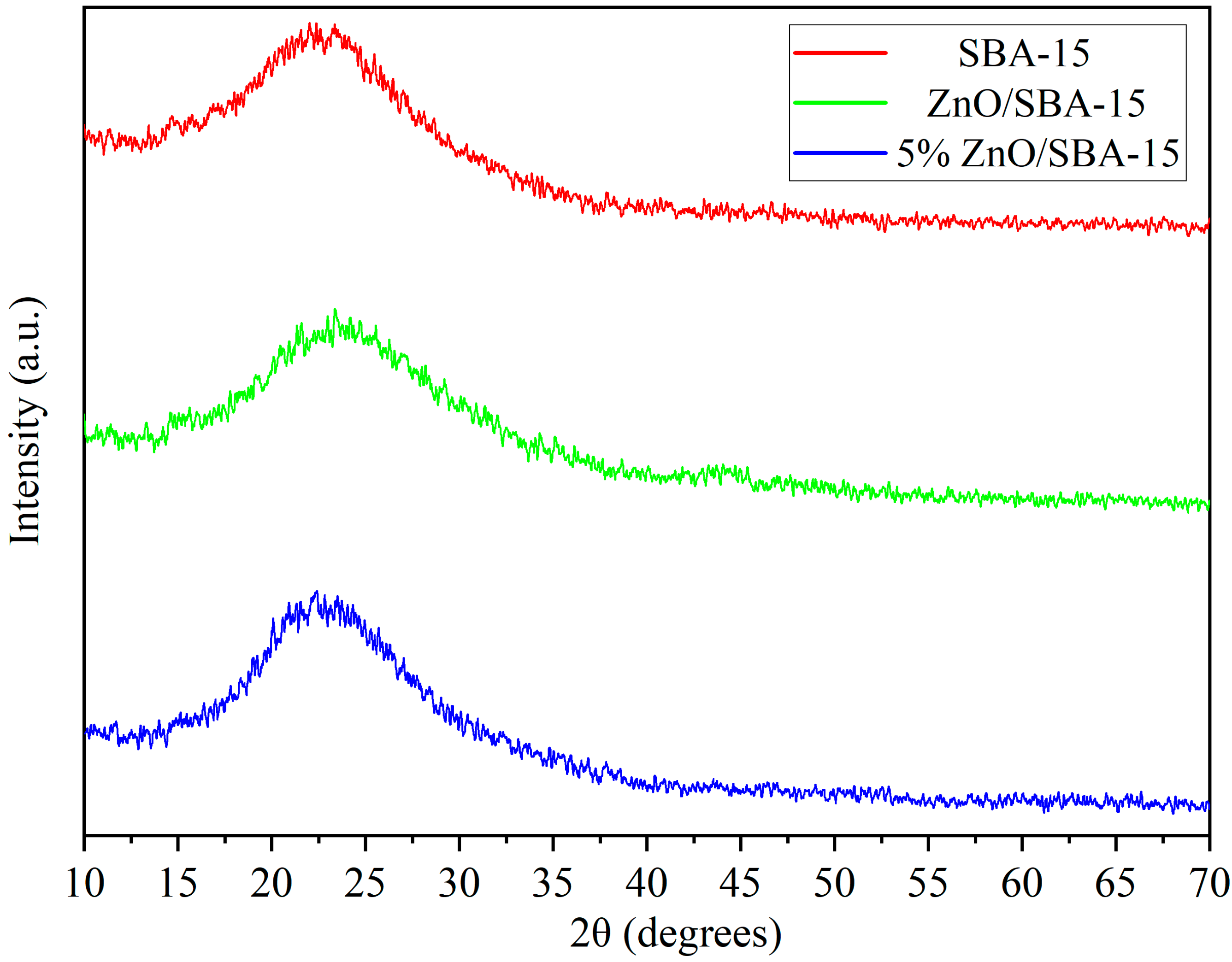

Figure 2 depicts the wide-angle XRD (WAXRD) patterns of the SBA-15 support, ZnO/SBA-15, and 5% La-ZnO/SBA-15 composites. All samples exhibit a broad diffraction hump in the 16–33° (2θ) range, characteristic of the amorphous silica framework of SBA-15 [

18,

19,

20,

21]. No additional reflections attributable to crystalline ZnO are observed for the composites, even though the Zn(NO

3)

2 precursor is completely decomposed to ZnO during calcination at 550 °C [

22]. This absence of distinct ZnO peaks indicates that the ZnO phase is present as highly dispersed, ultrafine nanoclusters confined within the SBA-15 mesopores, with crystallite sizes below the XRD detection limit (~3–5 nm) and with weak reflections overlapped by the intense amorphous silica [

23,

24]. Such pore-confined ZnO nanoclusters are often described as “XRD-amorphous” in SBA-15-based systems [

25,

26].

2.2. HRTEM Analysis

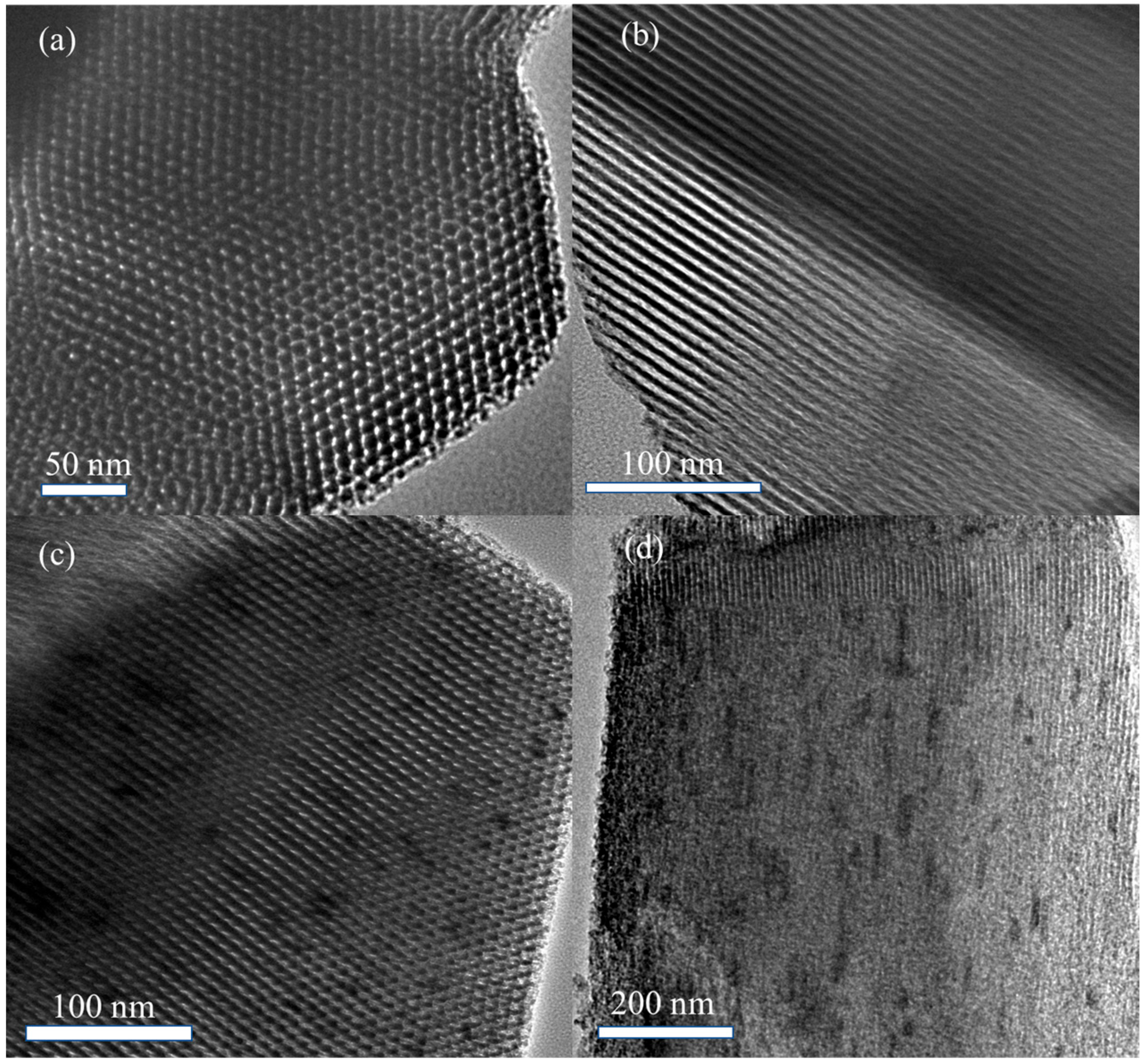

Figure 3 presents high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) images of SBA-15 and 5% La-ZnO/SBA-15.

Figure 3a illustrates the TEM image of SBA-15 viewed perpendicular to the pore channels, revealing a highly ordered 2D hexagonal honeycomb pore arrangement. The channels exhibit a regular configuration with long-range periodicity, uniform pore size distribution (~5–7 nm), and structural characteristics typical of SBA-15 mesostructures [

27].

Figure 3b depicts the image taken parallel to the pore axis, illustrating straight, parallel channels with consistent spacing and high aspect ratios, thereby further confirming the structural regularity and integrity.

Following the loading of the active component, the 5% La-ZnO/SBA-15 composite preserves the mesoporous structure of SBA-15, in agreement with the SAXRD analysis. In

Figure 3c, the composite exhibits a well-defined honeycomb pore arrangement characterized by hexagonal ordering and different channel boundaries. Within certain pores, discrete dark spots are observed, which are likely attributable to the incorporated ZnO species. The image oriented parallel to the pore direction (

Figure 3d) shows numerous dispersed dark nanoparticles on the pore walls and within the channels, presumably corresponding to ZnO clusters formed through the impregnation-annealing process.

2.3. FT-IR Analysis

Figure 4 illustrates the FT-IR spectra of SBA-15, ZnO/SBA-15, and 5% La-ZnO/SBA-15. All samples exhibit absorption peaks at approximately 3430 cm

−1 and 1633 cm

−1, which correspond to the stretching vibration of surface-adsorbed water or silanol groups (Si–OH) and the bending vibration of H–O–H in water molecules, respectively [

28,

29]. Within the skeletal vibration region (1400–400 cm

−1), the broad absorption band near 1080 cm

−1 is attributed to the asymmetric stretching vibration of Si–O–Si [

30], whereas the peaks at 800 cm

−1 and 460 cm

−1 are assigned to the symmetric stretching and bending vibrations of Si–O–Si, respectively [

18,

31]. Additionally, a weak absorption band near 960 cm

−1 is observed in all samples, which is typically ascribed to the stretching vibration of Si–O–Si [

32].

In the ZnO/SBA-15 and 5% La-ZnO/SBA-15 samples, a broad absorption band ranging from 1020 cm

−1 to 1230 cm

−1 is observed, with the signal near 1110 cm

−1 attributed to the stretching vibration of Zn–O bonds, which is typically characteristic of amorphous or polycrystalline ZnO materials [

33]. Notably, no additional different characteristic absorption peaks of ZnO are detected beyond this broad band, suggesting that ZnO is highly dispersed within the SBA-15 support, and likely to exist in an amorphous form or as ultrafine clusters. The weak infrared signal may result from the low ZnO content, which is potentially obscured by the intense Si–O–Si skeletal vibrations of the SBA-15 matrix, or from the high dispersion of ZnO clusters that prevents the formation of well-defined absorption features.

2.4. Sorption Analysis

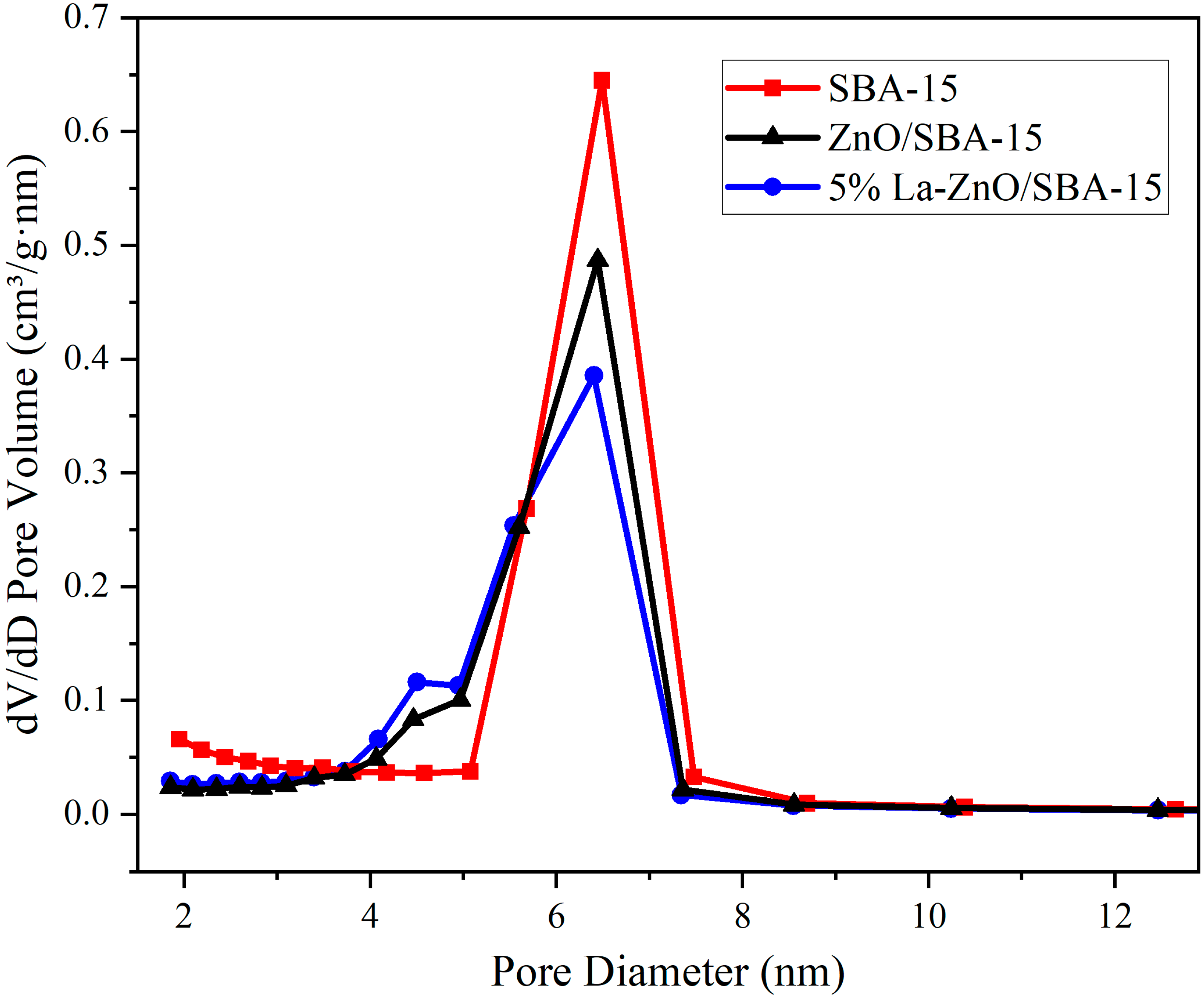

Figure 5 depicts the N

2 adsorption–desorption isotherms for SBA-15, ZnO/SBA-15, and 5% La-ZnO/SBA-15. All samples exhibit Type IV isotherms according to the 2015 IUPAC classification [

34], accompanied by H1-type hysteresis loops, which are indicative of materials possessing narrow pore size distributions and uniform cylindrical mesopores [

35]. The absence of significant changes in the isotherm type suggests that the ordered mesoporous channels of SBA-15 remain largely preserved during the formation of ZnO clusters, confirming the results obtained from SAXRD and TEM analyses.

In

Table 1, the structural parameters exhibit significant changes following ZnO loading. Specifically, the BET surface area (S

BET) decreases from 729.35 m

2 g

−1 for pure SBA-15 to 521.32 m

2 g

−1, representing a reduction of approximately 29.5%. Similarly, the total pore volume (Vp) decreases from 1.09 cm

3 g

−1 to 0.85 cm

3 g

−1, corresponding to a reduction of approximately 22.0%. These results confirm the successful incorporation of ZnO into the SBA-15 framework, with partial occupation of the pore channels resulting in moderate pore blockage.

Despite a reduction in pore volume, the average pore diameter calculated using the BJH method increases from 5.99 nm to 6.55 nm. This observation is further clarified by the BJH pore size distribution curves in

Figure 6, which show that the curves following ZnO loading exhibit broadened peaks and decreased intensity. These changes indicate a broader pore size distribution and reduced structural homogeneity. This phenomenon results from the non-uniform deposition of ZnO precursors within the SBA-15 channels: during impregnation and calcination, ZnO nanoparticles preferentially nucleate at constricted sites or pore entrances, thereby blocking smaller channels while leaving larger pores relatively accessible. Consequently, N

2 desorption measurements predominantly reflect the larger pores, leading to an “apparent increase” in the average pore diameter. Furthermore, secondary high-temperature calcination may cause localized sintering of the SBA-15 silica framework or minor collapse of pore walls, further contributing to structural disorder.

Integrated analysis of TEM, XRD, FT-IR, and N2 adsorption–desorption data reveals that the synthesized ZnO/SBA-15 nanocomposite retains the ordered hexagonal mesostructure of SBA-15 while confining ZnO clusters in an amorphous state within the mesopores. This pore-confined loading strategy not only suppresses ZnO nanoparticle aggregation—enhancing exposure of active sites—but also preserves high surface area and interconnected pore channels, facilitating reactant diffusion and mass transfer during catalytic processes. Such structural features provide a robust foundation for efficient photocatalytic degradation of organic pollutants in water, aligning with established literature on mesoporous silica-encapsulated metal oxides for environmental catalysis.

3. Discussion

3.1. Comparison of Photocatalytic Activity

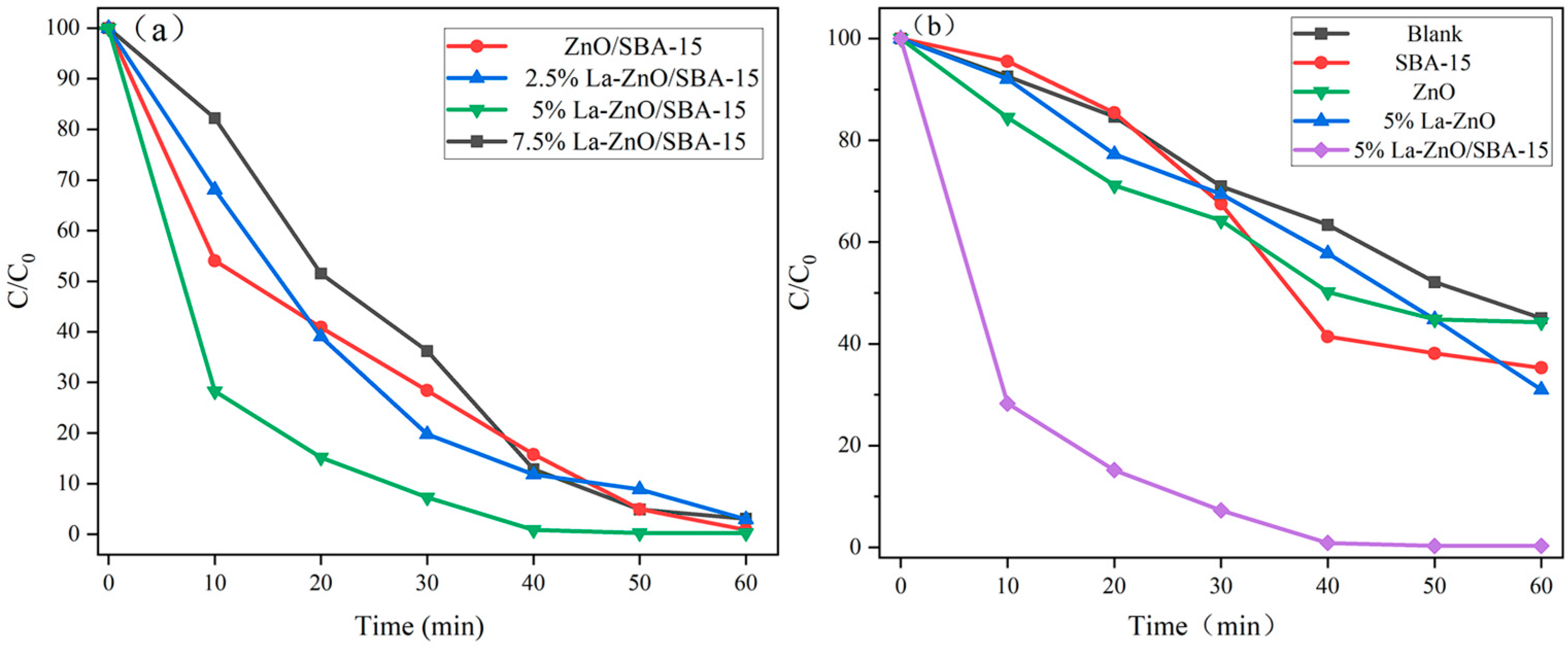

Figure 7a illustrates the photocatalytic degradation performance of RhB under visible light irradiation for ZnO/SBA-15 samples with varying La doping ratios. The undoped ZnO/SBA-15 sample achieves approximately 98% RhB degradation within 60 min, indicating favorable intrinsic photocatalytic activity. However, increasing the La doping concentration does not result in a linear improvement in photocatalytic performance: both the 2.5% and 7.5% La-doped ZnO/SBA-15 samples exhibit degradation efficiencies of approximately 95% at 60 min, comparable to the undoped sample. In contrast, the 5% La-doped ZnO/SBA-15 sample demonstrates significantly enhanced activity, achieving near-complete RhB degradation (>99%) within 40 min, thereby significantly outperforming all other samples.

The blank solution, pure SBA-15, pure ZnO, and La-ZnO exhibit nearly identical degradation efficiencies, achieving only ~40% RhB degradation after 60 min of irradiation. In contrast, the 5% La-ZnO/SBA-15 composite achieves near-complete RhB degradation (>99%) within 40 min, exhibiting significantly superior performance compared to all other samples.

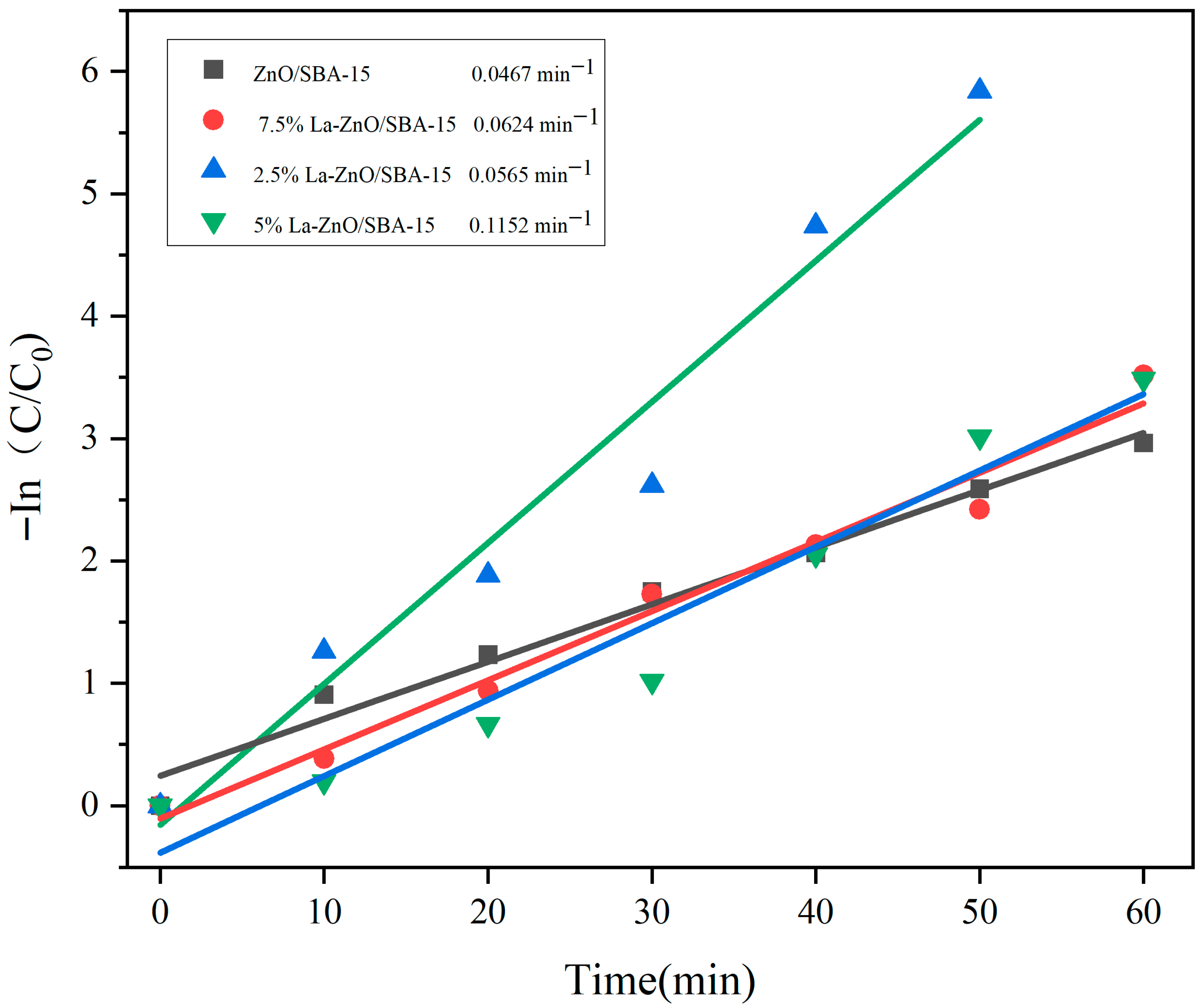

Figure 8 depicts the kinetic analysis based on the Langmuir–Hinshelwood model, demonstrating that the photodegradation of RhB adheres to pseudo-first-order kinetics [

36]:

where C

0 and C represent the initial and instantaneous concentrations of RhB at time t, respectively; k represents the apparent first-order rate constant (min

−1); and t represents the reaction time (min).

The fitting results indicate rate constants of 0.1152 min−1 for 5% La-ZnO/SBA-15, 0.0467 min−1 for undoped ZnO/SBA-15, 0.0565 min−1 for 2.5% La-ZnO/SBA-15, and 0.0624 min−1 for 7.5% La-ZnO/SBA-15. These results reveal that 5% La-ZnO/SBA-15 exhibits a significantly higher rate constant, thereby confirming its superior kinetic performance in the photodegradation of RhB.

Figure 9 presents the recyclability test results of 5% La-ZnO/SBA-15 over four consecutive cycles. In the initial run, the catalyst achieved 99% degradation of RhB, indicating excellent initial activity. During the second cycle, the efficiency remained at 94%, demonstrating robust structural stability. The degradation efficiency stabilized at approximately 93% in the third and fourth cycles, with no significant decline, thereby confirming consistent catalytic performance. Although minor deactivation of active sites or slight leaching of active components may have occurred during recycling, the overall performance exhibited no substantial deterioration. After four cycles, efficiency decreased by approximately 7%, underscoring the catalyst’s excellent reusability and operational stability for practical applications. As summarized in

Table 2, the photocatalytic performance of the synthesized 5% La-ZnO/SBA-15 composite is compared with various ZnO-based catalysts reported in the literature for dye degradation. The comparison reveals that the 5% La-ZnO/SBA-15 composite achieves a high degradation efficiency (>99%) within a notably shorter time (40 min) under visible light. For instance, the ZnO–SiO

2 composite [

37] required 60 min to reach a comparable efficiency under UV light, and the flower-like ZnO@SiO

2 [

38] attained only 85% degradation after 180 min of UV light. These results indicate advantage and potential of the 5% La-ZnO/SBA-15 composite for efficient pollutant degradation under visible light.

3.2. Photocatalytic Mechanism Explained

To elucidate the reaction mechanism underlying the photodegradation of RhB over 5% La-ZnO/SBA-15, 50 mg of photocatalyst was dispersed in 100 mL of RhB solution (20 mg L

−1), and systematic radical trapping experiments were performed (

Figure 10). The addition of specific scavengers significantly inhibited the degradation efficiency: the ·O

2− scavenger BQ decreased the degradation rate to 32%; ·OH and h

+ co-scavenger MeOH reduced it to 38%; the h

+-specific scavenger EDTA-Na lowered it to 42%; and the e

− scavenger KI diminished it to 53%. In contrast, the degradation efficiency exceeded 99% in the absence of scavengers. These results unequivocally demonstrate the synergistic involvement of e

−, h

+, ·OH, and ·O

2− in the photodegradation process.

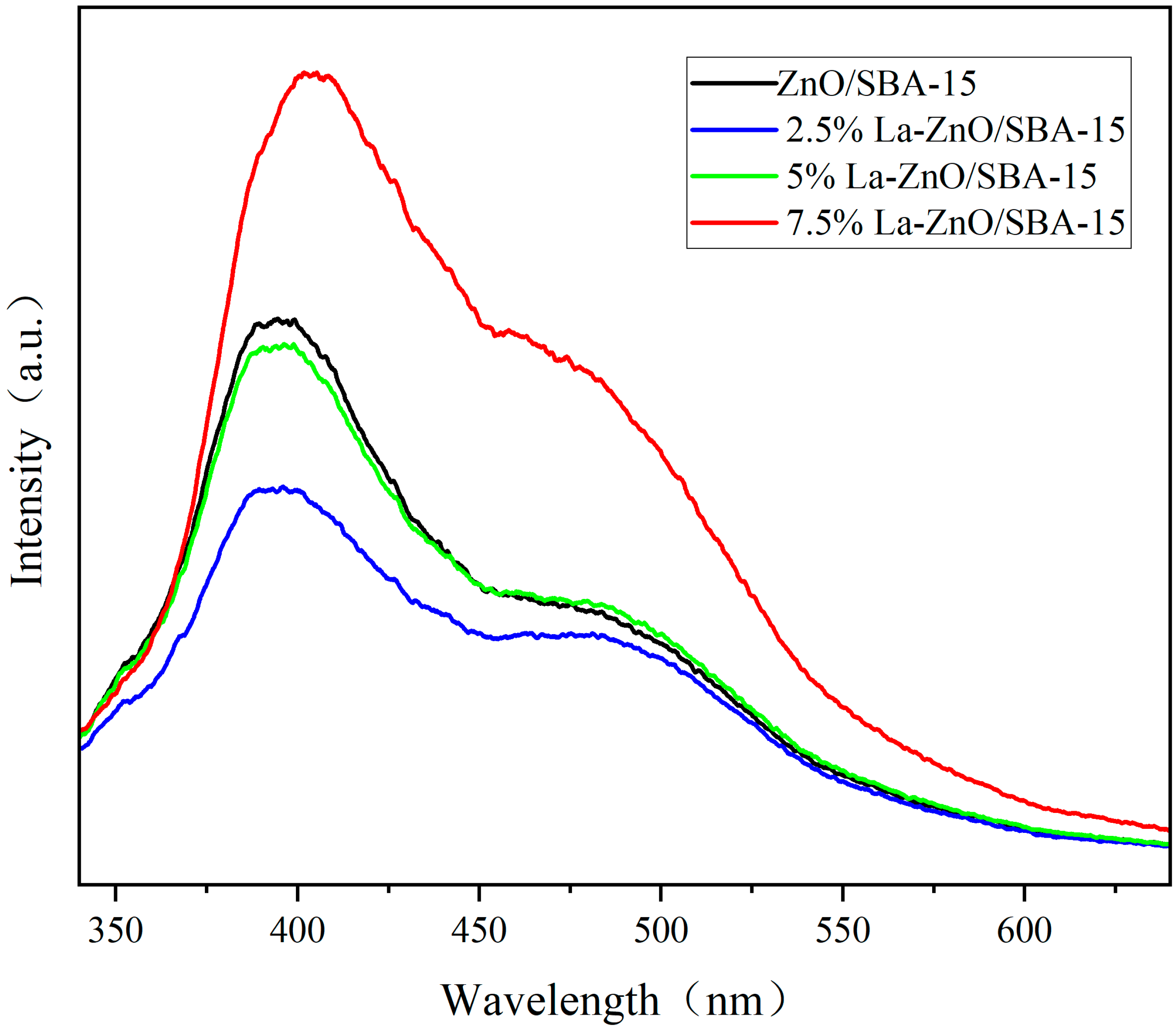

To elucidate the charge carrier separation behavior underlying the radical trapping experiments, Photoluminescence (PL) spectroscopy was utilized to assess charge separation efficiency. In

Figure 11, ZnO/SBA-15 samples with varying La doping concentrations exhibit two characteristic emission bands: a prominent broad peak near 380 nm and a weaker broad peak approximately 480 nm, corresponding to near-band-edge (NBE) radiative recombination and deep-level emission (DLE) associated with oxygen vacancies and Zn interstitial defects, respectively [

43,

44,

45]. With increasing La doping concentration, the overall PL intensity first decreases and then increases: the undoped ZnO/SBA-15 sample shows the highest emission intensity, which decreases progressively at 2.5% and 5% La, and rises again at 7.5% La. The most pronounced fluorescence quenching is observed for the 5% La–ZnO/SBA-15 sample, indicating that this doping level provides an optimal concentration of La-induced defect states and trapping sites to promote the separation and migration of photogenerated e

−–h

+ pairs while suppressing their radiative recombination [

46,

47,

48]. At higher La loading (7.5%), excessive La-related defects and/or La-rich clusters are likely formed, which act as additional recombination centers and partly offset the beneficial effect of La doping, in agreement with the partial recovery of PL intensity. The optimized charge-carrier separation at 5% La doping allows a larger fraction of photogenerated carriers to participate in surface redox reactions, thereby enhancing the photocatalytic degradation of RhB [

49,

50].

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

The following chemicals were utilized in the synthesis of the photocatalyst: La(NO3)3·6H2O (99%, Macklin Biochemical, Shanghai, China) and Zn(NO3)2·6H2O (99%, Macklin Biochemical, Shanghai, China) served as the La and Zn precursors, respectively; deionized water (DI), EO20PO70EO20 (P123, Mn ~5800, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS, 99%, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), and HCl (37%, Sinopharm, Shanghai, China) were employed for the preparation of the SBA-15 template; and CH3CH2OH (99%, Sinopharm, Shanghai, China) was also used. All chemicals were utilized as received without further purification.

4.2. Synthesis of SBA-15

SBA-15 mesoporous material was synthesized with minor modifications to a previously established protocol [

10]. In brief, 4 g of Pluronic P123 copolymer was added directly to 150 mL of 1.7 mol L

−1 HCl solution and stirred in a water bath at 303 K until a colorless, transparent solution was obtained. The temperature of the bath then increased to 312 K, and 9.4 mL of TEOS was slowly added dropwise using a pipette. The mixture was continuously stirred at this temperature for 24 h. Subsequently, the solution was transferred to an autoclave and subjected to hydrothermal crystallization at 373 K for 24 h. Following the reaction, the product was collected via vacuum filtration using a Büchner funnel, and the resulting filter cake was alternately washed with deionized water and CH

3CH

2OH for three cycles to remove residual HCl and Pluronic P123 template. The solid was subsequently dried at 373 K for 12 h in air, followed by calcination at 823 K for 3 h in air, yielding SBA-15.

4.3. Synthesis of La-ZnO/SBA-15

La-ZnO/SBA-15 composites were synthesized using a post-impregnation technique. SBA-15 was first vacuum-dried at 343 K for 2 h. Subsequently, a predetermined amount of La(NO

3)

3·6H

2O and 0.24 g of Zn(NO

3)

2·6H

2O were dissolved in 10 mL of CH

3CH

2OH, followed by the addition of 0.2 g of the pre-treated SBA-15. The resulting mixture was uniformly dispersed with ultrasonic assistance and continuously stirred at ambient temperature for 24 h. After stirring, the mixture was dried in air at 333 K for 12 h to ensure complete solvent evaporation, followed by annealing in a tube furnace at 823 K for 2 h. Employing this procedure, a series of La–ZnO/SBA-15 samples with different La-doping levels (0, 2.5, 5.0, and 7.5 at.%) were prepared by adjusting the amount of La(NO

3)

3 precursor relative to Zn(NO

3)

2 in the impregnation solution. Here, the La content is expressed as atomic percent (at.%), defined as the molar fraction of La in the total amount of La and Zn. The synthesis route is schematically illustrated in

Figure 12.

4.4. Characterization

The surface morphology of the samples was examined using a FEI Tecnai G2 F20 TEM (FEI Company, Hillsboro, OR, USA). The crystal structure and mesostructure were investigated employing a Bruker D8 Advance XRD with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5406 Å). FT-IR spectra were obtained using a Nicolet 6700 spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) using the KBr pellet method, with a resolution of 4 cm−1. N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms were measured using a Micromeritics ASAP 2460 surface area analyzer (Micromeritics Instrument Corporation, Norcross, GA, USA). Prior to analysis, samples were degassed under vacuum at 373 K for 12 h. The specific surface area was calculated by the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) method. The pore-size distribution was obtained from the desorption branch of the isotherms by applying the Barrett–Joyner–Halenda (BJH) method, which uses the Kelvin equation to relate the relative pressure of capillary condensation to the mesopore radius. PL spectra were recorded with the fluorescence module of a HORIBA micro-Raman spectrometer, employing an excitation wavelength of 325 nm.

4.5. Photocatalytic Evaluation

The photocatalytic degradation of RhB at a concentration of 20 mg L−1 was investigated using La-ZnO/SBA-15 catalysts under irradiation from a 250 W Hg lamp. In the experimental procedure, 50 mg of the photocatalyst was dispersed in 100 mL of the RhB solution, followed by a 30 min dark adsorption period to achieve adsorption equilibrium. Subsequently, at 15 min intervals after the initiation of illumination, 3 mL aliquots were withdrawn and centrifuged to remove catalyst particles. The concentration of RhB was quantified by measuring the absorbance at 553 nm using a Hitachi U-3900 UV-Vis spectrophotometer.

The degradation efficiency was determined as follows:

To elucidate the active species involved in the photocatalytic process, radical scavenging experiments were conducted using specific quenchers: benzoquinone (BQ, 0.01 mol L

−1) to target ·O

2−, ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid disodium salt (EDTA-Na, 0.1 mol L

−1) for h

+, KI (0.1 mol L

−1) for surface-bound ·OH and h

+, and methanol (MeOH, 0.1 mol L

−1) for ·OH [

18,

19,

20,

21].

5. Conclusions

La-doped ZnO/SBA-15 mesoporous composites were prepared by an impregnation–calcination route and evaluated as visible-light photocatalysts for RhB degradation. Structural characterization confirms that the ordered 2D hexagonal mesostructure and mesoporosity of SBA-15 are preserved after ZnO and La loading, with ZnO present as amorphous or ultrafine clusters confined within the mesopores.

Photocatalytic tests show that the activity strongly depends on the La content, with the 5% La-ZnO/SBA-15 sample exhibiting the best performance: it achieves nearly complete RhB degradation within 40 min and maintains high efficiency over repeated cycles, indicating good stability. Radical trapping experiments reveal that h+ and ·OH are the main reactive species, with ·O2− also contributing, and that appropriate La doping promotes charge separation and suppresses recombination.

In summary, the combination of mesoporous confinement and optimal rare-earth doping offers a promising strategy for the design of robust photocatalytic systems aimed at the efficient degradation of organic pollutants in aqueous environments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.Z. and W.Y.; methodology, Z.Z.; soft-ware, Z.Z.; validation, Z.Z., W.Y. and H.P.; formal analysis, Z.Z.; investigation, Z.Z.; resources, Z.Z.; data curation, Z.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.Z.; writing—review and editing, Z.Z.; visualization, Z.Z.; supervision, H.P.; project administration, S.Z. and J.Z.; funding acquisition, S.Z. and J.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Please add: This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. U1704145); the Hainan Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 522MS062); the Special Research Fund of the Innovation Platform for Academicians of Hainan Province (Grant No. YSPTZX202207); and the Nature Science Foundation for High-level Talents in Higher Education of Hainan (Grant No. 422RC667).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Nidheesh, P.V.; Couras, C.; Karim, A.V.; Nadais, H. A review of integrated advanced oxidation processes and biological processes for organic pollutant removal. Chem. Eng. Commun. 2022, 209, 390–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titchou, F.E.; Zazou, H.; Afanga, H.; El Gaayda, J.; Ait Akbour, R.; Nidheesh, P.V.; Hamdani, M. Removal of organic pollutants from wastewater by advanced oxidation processes and its combination with membrane processes. Chem. Eng. Process.—Process Intensif. 2021, 169, 108631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, D.K.; Shukla, S.; Sharma, K.K.; Kumar, V. A review on ZnO: Fundamental properties and applications. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 49, 3028–3035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Yang, W.; Peng, H.; Zhao, S. Preparation and the Photoelectric Properties of ZnO-SiO2 Films with a Sol–Gel Method Combined with Spin-Coating. Sensors 2024, 24, 7751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Chen, R.; Xiang, L.; Komarneni, S. Synthesis, properties and applications of ZnO nanomaterials with oxygen vacancies: A review. Ceram. Int. 2018, 44, 7357–7377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, M.W.; Al-Obaidi, M.A.; Kosslick, H.; Schulz, A. Photocatalytic degradation of pharmaceutical pollutants using zinc oxide supported by mesoporous silica. J. Sol-Gel Sci. Technol. 2021, 98, 300–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kankala, R.K.; Han, Y.-H.; Na, J.; Lee, C.-H.; Sun, Z.; Wang, S.-B.; Kimura, T.; Ok, Y.S.; Yamauchi, Y.; Chen, A.-Z.; et al. Nanoarchitectured Structure and Surface Biofunctionality of Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, 1907035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, A.L.T.; Abdullah, C.A.C.; Chung, E.L.T.; Andou, Y. Recent progress in visible light-doped ZnO photocatalyst for pollution control. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 20, 5753–5772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, U.; Khan, A.; Raza, W.; Khan, A.; Bahnemann, D.; Muneer, M. Highly efficient Y and V co-doped ZnO photocatalyst with enhanced dye sensitized visible light photocatalytic activity. Catal. Today 2017, 284, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Feng, J.; Huo, Q.; Melosh, N.; Fredrickson, G.H.; Chmelka, B.F.; Stucky, G.D. Triblock Copolymer Syntheses of Mesoporous Silica with Periodic 50 to 300 Angstrom Pores. Science 1998, 279, 548–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltani, S.; Khanian, N.; Rashid, U.; Yaw Choong, T.S. Fundamentals and recent progress relating to the fabrication, functionalization and characterization of mesostructured materials using diverse synthetic methodologies. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 16431–16456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahab, M.A.; Beltramini, J.N. Recent advances in hybrid periodic mesostructured organosilica materials: Opportunities from fundamental to biomedical applications. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 79129–79151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busuioc, A.M.; Meynen, V.; Beyers, E.; Mertens, M.; Cool, P.; Bilba, N.; Vansant, E.F. Structural features and photocatalytic behaviour of titania deposited within the pores of SBA-15. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2006, 312, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubakar Abdulkadir, B.; Mohd Zaki, R.S.R.; Abd Jalil, A.; Fang Su, J.; Setiabudi, H.D. Synergistic effects of Fe2O3 supported on dendritic fibrous SBA-15 for superior photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2025, 185, 108859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Wang, M.; Liu, J.; Guo, B. Recent advances of SBA-15-based composites as the heterogeneous catalysts in water decontamination: A mini-review. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 254, 109787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucovsky, G.; Phillips, J.C. Defects and defect relaxation at internal interfaces between high-k transition metal and rare earth dielectrics and interfacial native oxides in metal oxide semiconductor (MOS) structures. Thin Solid Film. 2005, 486, 200–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemalatha, P.; Karthick, S.N.; Hemalatha, K.V.; Yi, M.; Kim, H.-J.; Alagar, M. La-doped ZnO nanoflower as photocatalyst for methylene blue dye degradation under UV irradiation. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2016, 27, 2367–2378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo, V.; Tran Thi, T.P.; Kim, H.-Y.; Kim, S.J. Facile post-synthesis and photocatalytic activity of N-doped ZnO–SBA-15. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2014, 75, 403–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bariki, R.; Das, K.; Pradhan, S.K.; Prusti, B.; Mishra, B.G. MOF-Derived Hollow Tubular In2O3/MIIIn2S4 (MII: Ca, Mn, and Zn) Heterostructures: Synergetic Charge-Transfer Mechanism and Excellent Photocatalytic Performance to Boost Activation of Small Atmospheric Molecules. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2022, 5, 11002–11017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, S.; Yu, J.; Oh, J.Y.; Lee, T.I. Hybrid poly (3-hexylthiophene) (P3HT) nanomesh/ZnO nanorod p-n junction visible photocatalyst for efficient indoor air purification. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 496, 143641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Y.; Yu, Y.; Lei, X.; Liang, X.; Cheng, S.; Ouyang, G.; Yang, X. Assessing the Use of Probes and Quenchers for Understanding the Reactive Species in Advanced Oxidation Processes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 5433–5444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Feng, Z.; Ying, P.; Li, M.; Han, B.; Li, C. The visible luminescent characteristics of ZnO supported on SiO2 powder. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2004, 6, 4473–4479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; Wang, Z.; Li, J.; Wang, P.; Ye, X. Structure and Photoluminescent Properties of ZnO Encapsulated in Mesoporous Silica SBA-15 Fabricated by Two-Solvent Strategy. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2009, 4, 646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.M.; Wu, Z.Y.; Shi, L.Y.; Zhu, J.H. Rapid Functionalization of Mesoporous Materials: Directly Dispersing Metal Oxides into As-Prepared SBA-15 Occluded with Template. Adv. Mater. 2005, 17, 323–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vepřek, S.; Iqbal, Z.; Sarott, F.A. A thermodynamic criterion of the crystalline-to-amorphous transition in silicon. Philos. Mag. B 1982, 45, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihai, G.D.; Meynen, V.; Mertens, M.; Bilba, N.; Cool, P.; Vansant, E.F. ZnO nanoparticles supported on mesoporous MCM-41 and SBA-15: A comparative physicochemical and photocatalytic study. J. Mater. Sci. 2010, 45, 5786–5794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, A.; Sousa, E.M.B. Influence of synthesis temperature on the structural characteristics of mesoporous silica. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2006, 352, 3451–3456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellerbrock, R.; Stein, M.; Schaller, J. Comparing amorphous silica, short-range-ordered silicates and silicic acid species by FTIR. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 11708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, S.A.; Khan, S.B.; Khan, L.U.; Farooq, A.; Akhtar, K.; Asiri, A.M. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy: Fundamentals and Application in Functional Groups and Nanomaterials Characterization. In Handbook of Materials Characterization; Sharma, S.K., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 317–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Cheng, M.; Cui, Y.; Zhang, R.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, X.; Guo, S. Effect of SBA-15-CEO on properties of potato starch film modified by low-temperature plasma. Food Biosci. 2023, 51, 102313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta-Silva, Y.J.; Nava, R.; Hernández-Morales, V.; Macías-Sánchez, S.A.; Gómez-Herrera, M.L.; Pawelec, B. Methylene blue photodegradation over titania-decorated SBA-15. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2011, 110, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oréfice, R.L.; Vasconcelos, W.L. Sol-Gel transition and structural evolution on multicomponent gels derived from the alumina-silica system. J. Sol-Gel Sci. Technol. 1997, 9, 239–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, P.; Yang, W.; Peng, H.; Zhao, S. Efficient Degradation of Methylene Blue in Industrial Wastewater and High Cycling Stability of Nano ZnO. Molecules 2024, 29, 5584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thommes, M.; Kaneko, K.; Neimark, A.V.; Olivier, J.P.; Rodriguez-Reinoso, F.; Rouquerol, J.; Sing, K.S.W. Physisorption of gases, with special reference to the evaluation of surface area and pore size distribution (IUPAC Technical Report). Pure Appl. Chem. 2015, 87, 1051–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abelniece, Z.; Kampars, V.; Piirsoo, H.-M.; Mändar, H.; Tamm, A. The influence of Zn content in Cu/ZnO/SBA-15/kaolinite catalyst for methanol production by CO2 hydrogenation. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 625–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saratovskii, A.S.; Bulyga, D.V.; Evstrop’ev, S.K.; Antropova, T.V. Adsorption and Photocatalytic Activity of the Porous Glass–ZnO–Ag Composite and ZnO–Ag Nanopowder. Glass Phys. Chem. 2022, 48, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.-Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, L. Fabrication of ZnO–SiO2 and Its Photocatalytic Degradation of Rhodamine B. J. Synth. Cryst. 2017, 26, 1456–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Shi, Y.; Shao, H.; Liu, Y.; Zhai, Y. Synthesis and photocatalytic degradation ability evaluation for rhodamine B of ZnO@SiO2 composite with flower-like structure. Water Sci. Technol. 2020, 80, 1986–1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihai, S.; Cursaru, D.L.; Şomoghi, R.; Nistor, C.L. Synthesis of Ruthenium-Promoted ZnO/SBA-15 Composites for Enhanced Photocatalytic Degradation of Methylene Blue Dye. Polymers 2023, 15, 1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Chen, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Sun, C.; Li, J. High photocatalytic activity over starfish-like La-doped ZnO/SiO2 photocatalyst for malachite green degradation under visible light. J. Rare Earths 2021, 39, 772–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Qin, W.; Zhu, H.; Dai, Y.; Hong, X.; Han, S.; Xie, Y. Construction of ZnO/r-GO Composite Photocatalyst for Improved Photodegradation of Organic Pollutants. Molecules 2025, 30, 1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Li, J.; Wang, J.; Deng, L. Synergistic Enhancement of Carrier Migration by SnO2/ZnO@GO Heterojunction for Rapid Degradation of RhB. Molecules 2024, 29, 854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Yang, L.; Wang, L.; Yu, B.; Chen, Y.; Cui, Y. Synthesis and Luminescence Properties of ZnO:Eu3+ Nanowire Arrays via Electrodeposited Method. Funct. Mater. Lett. 2010, 3, 285–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Wang, L.; Yang, L.; Wang, Z. Synthesis and luminescence properties of ZnO:Tb3+ nanotube arrays via electrodeposited method. Phys. B Condens. Matter 2010, 405, 3200–3204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Ma, H.; Wang, L.; Yang, L.; Cui, Y. Synthesis and Luminescence Properties of ZnO Nanoneedle Arrays via Electrodeposited Method. Surf. Rev. Lett. 2010, 17, 425–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moafi, H.F.; Zanjanch, M.A.; Shojaie, A.F. Lanthanum and Zirconium Co-Doped ZnO Nanocomposites: Synthesis, Characterization and Study of Photocatalytic Activity. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2014, 14, 7139–7150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Chen, G.; Yu, Y.; Zhao, L.; Yu, Q.; He, Q. Effects of La-doping on charge separation behavior of ZnO:GaN for its enhanced photocatalytic performance. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2016, 6, 1033–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Crisostomo, J.C.; López-Juárez, R.; Petranovskii, V. Photocatalytic Degradation of Rhodamine B Dye in Aqueous Suspension by ZnO and M-ZnO (M = La3+, Ce3+, Pr3+ and Nd3+) Nanoparticles in the Presence of UV/H2O2. Processes 2021, 9, 1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, H.; Shi, Q.; Zhang, X.; Jiang, W.; Lin, X.; Hu, R.; Liu, T.; Jiang, X. Synergistic Optimization of Charge Carrier Separation and Transfer in ZnO through Crystal Facet Engineering and Piezoelectric Effect. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2025, 693, 137599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, N.; Si, X.; He, L.; Zhang, J.; Sun, Y. Strategies for Enhancing the Photocatalytic Activity of Semiconductors. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 58, 1249–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

SAXRD patterns of the prepared samples.

Figure 1.

SAXRD patterns of the prepared samples.

Figure 2.

WAXRD patterns of the prepared samples.

Figure 2.

WAXRD patterns of the prepared samples.

Figure 3.

HRTEM images of SBA-15 (a,b) and 5% La-ZnO/SBA-15 (c,d): (a) SBA-15 perpendicular to pore channels; (b) SBA-15 parallel to pore channels; (c) 5% La-ZnO/SBA-15 perpendicular to pore channels; (d) 5% La-ZnO/SBA-15 parallel to pore channels.

Figure 3.

HRTEM images of SBA-15 (a,b) and 5% La-ZnO/SBA-15 (c,d): (a) SBA-15 perpendicular to pore channels; (b) SBA-15 parallel to pore channels; (c) 5% La-ZnO/SBA-15 perpendicular to pore channels; (d) 5% La-ZnO/SBA-15 parallel to pore channels.

Figure 4.

FT-IR spectra of the SBA-15, ZnO/SBA-15, and 5% La-ZnO/SBA-15.

Figure 4.

FT-IR spectra of the SBA-15, ZnO/SBA-15, and 5% La-ZnO/SBA-15.

Figure 5.

N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms of the SBA-15, ZnO/SBA-15, and 5% La-ZnO/SBA-15.

Figure 5.

N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms of the SBA-15, ZnO/SBA-15, and 5% La-ZnO/SBA-15.

Figure 6.

BJH pore size distribution curves of the SBA-15, ZnO/SBA-15, and 5% La-ZnO/SBA-15.

Figure 6.

BJH pore size distribution curves of the SBA-15, ZnO/SBA-15, and 5% La-ZnO/SBA-15.

Figure 7.

(a) Photocatalytic degradation of RhB over ZnO/SBA-15 samples with different La doping ratios under visible-light irradiation. (b) Photocatalytic degradation of RhB over blank solution, pure SBA-15, pure ZnO, La-ZnO, and 5% La-ZnO/SBA-15 under visible-light irradiation.

Figure 7.

(a) Photocatalytic degradation of RhB over ZnO/SBA-15 samples with different La doping ratios under visible-light irradiation. (b) Photocatalytic degradation of RhB over blank solution, pure SBA-15, pure ZnO, La-ZnO, and 5% La-ZnO/SBA-15 under visible-light irradiation.

Figure 8.

Pseudo-first-order kinetic fitting curves for RhB photodegradation over ZnO/SBA-15 samples with different La doping concentrations.

Figure 8.

Pseudo-first-order kinetic fitting curves for RhB photodegradation over ZnO/SBA-15 samples with different La doping concentrations.

Figure 9.

Cycling degradation of RhB by the 5% La-ZnO/SBA-15 under visible light irradiation.

Figure 9.

Cycling degradation of RhB by the 5% La-ZnO/SBA-15 under visible light irradiation.

Figure 10.

The degradation curve of RhB by 5% La-ZnO/SBA-15 photocatalyst under different quenching conditions.

Figure 10.

The degradation curve of RhB by 5% La-ZnO/SBA-15 photocatalyst under different quenching conditions.

Figure 11.

PL spectra of La-ZnO/SBA-15 composites.

Figure 11.

PL spectra of La-ZnO/SBA-15 composites.

Figure 12.

Schematic illustration of the preparation route of La–ZnO/SBA-15.

Figure 12.

Schematic illustration of the preparation route of La–ZnO/SBA-15.

Table 1.

The mesoscopic structure parameters of the SBA-15, ZnO/SBA-15, and 5% La-ZnO/SBA-15.

Table 1.

The mesoscopic structure parameters of the SBA-15, ZnO/SBA-15, and 5% La-ZnO/SBA-15.

| Samples | SBET (m2/g) | Pore Volume (cm3/g) | Pore Diameter (nm) |

|---|

| SBA-15 | 729.35 | 1.09 | 5.99 |

| ZnO/SBA-15 | 534.61 | 0.90 | 6.74 |

| 5%La-ZnO/SBA-15 | 521.32 | 0.85 | 6.55 |

Table 2.

Comparison with various ZnO-based composite photocatalysts.

Table 2.

Comparison with various ZnO-based composite photocatalysts.

| Catalyst | Light Source | Dye Concertation | Photocatalyst Mass | Irradiation Time (min) | Efficiency (%) | Reference |

|---|

| Y doped V-ZnO NPs | Visible Light | RhB | 3 g/L | 180 | 87.5 | [9] |

| ZnO-SiO2 | UV Light | RhB (10 mg/L) | 0.5 g/L | 60 | 95 | [37] |

| ZnO@SiO2 | UV Light | RhB (20 mg/L) | 15 g/L | 180 | 82.5 | [38] |

| Ru-induced ZnO/SBA-15 | UV Light | MB (20 mg/L) | 1 g/L | 120 | 97.96 | [39] |

| La-doped ZnO/SiO2 | Sunlight | MG (15 mg/L) | 0.3 g/L | 120 | 92.1 | [40] |

| ZnO/r-GO | Visible Light | RhB | 0.5 g/L | 150 | 100 | [41] |

| SnO2/ZnO@GO | Visible Light | RhB (15 mg/L) | 0.2 g/L | 60 | 98.9 | [42] |

| La-Doped ZnO/SBA-15 | Visible Light | RhB (20 mg/L) | 0.5 g/L | 40 | 99.71 | This work |

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).