Cu14H12(PtBu3)6Cl2—The Expanse of Stryker’s Reagent

Abstract

1. Introduction

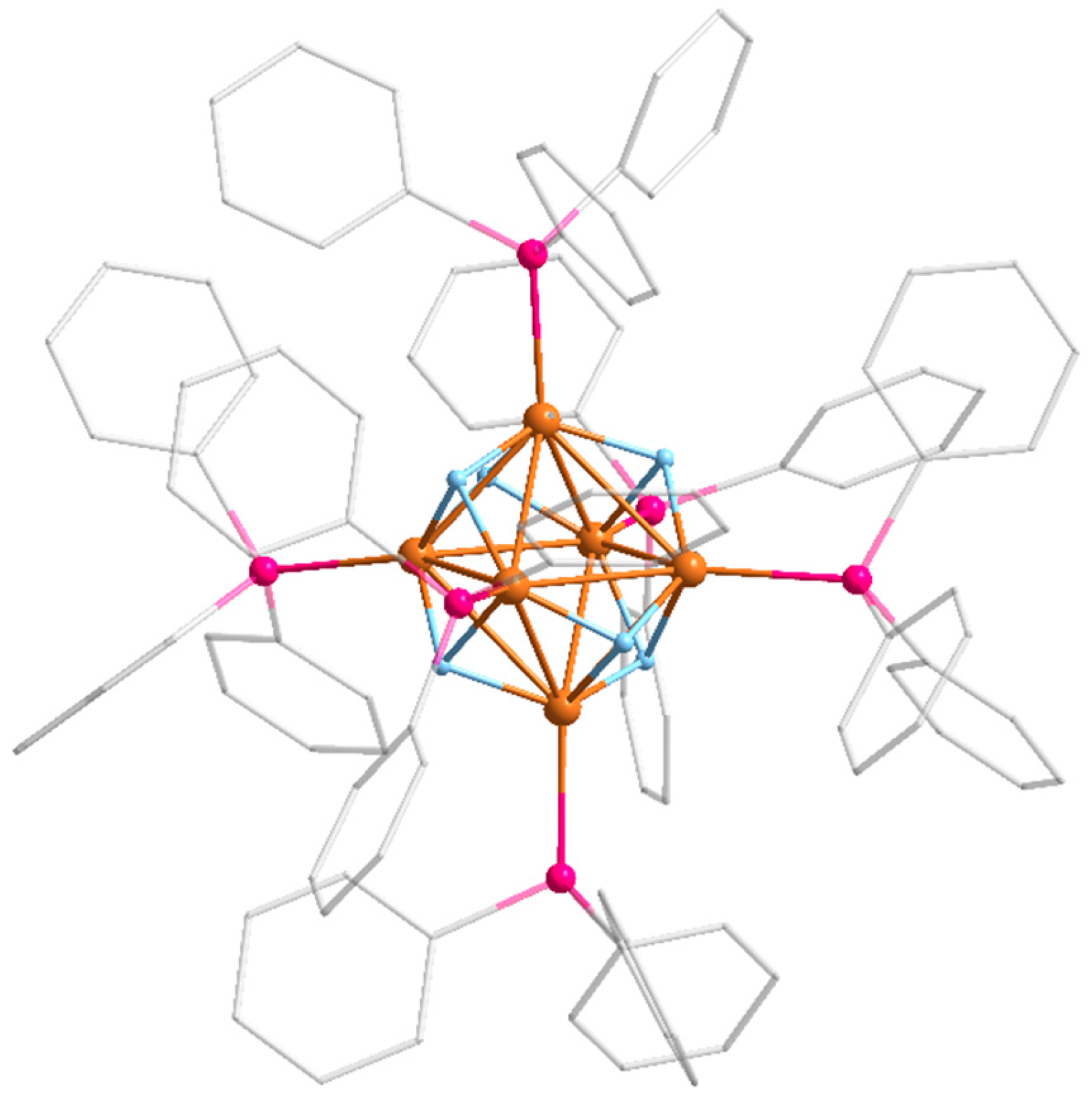

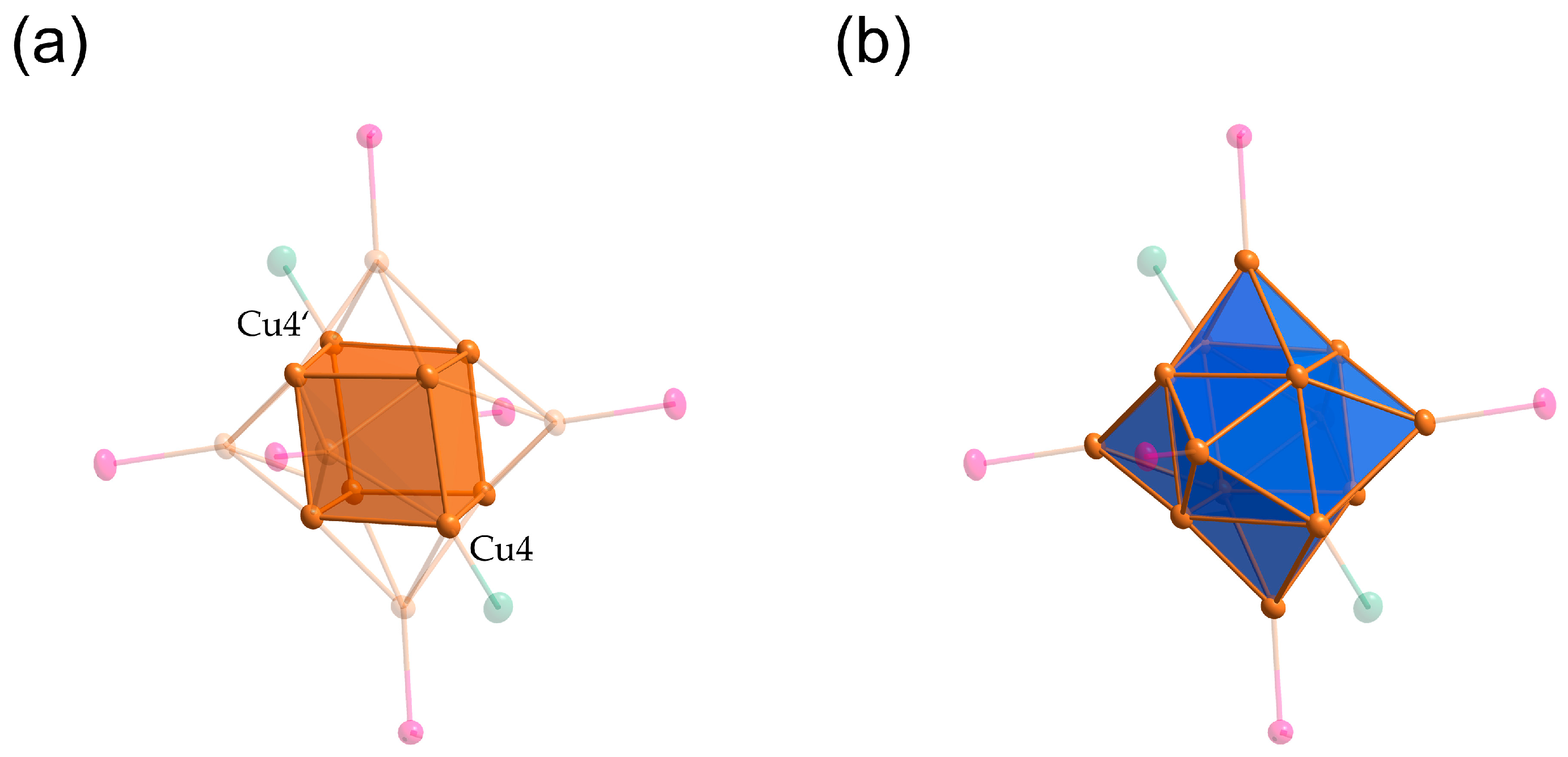

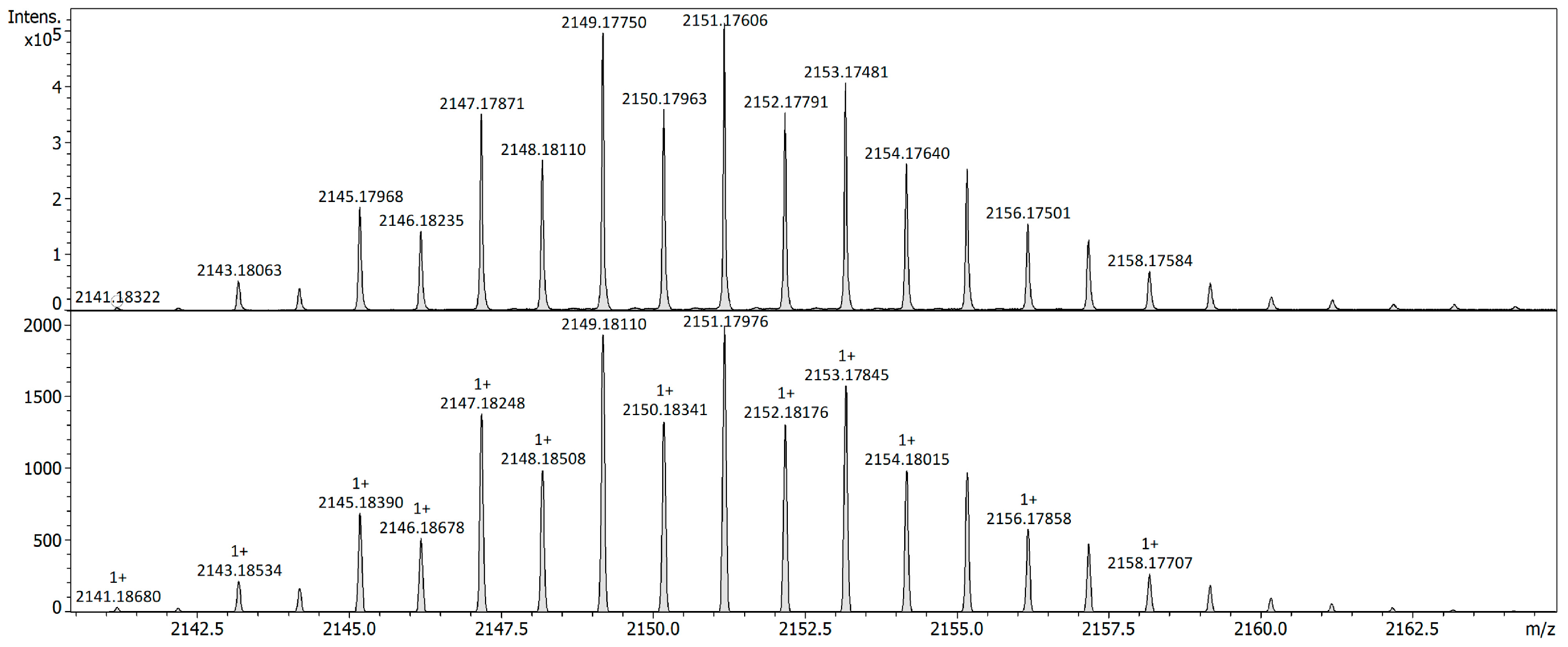

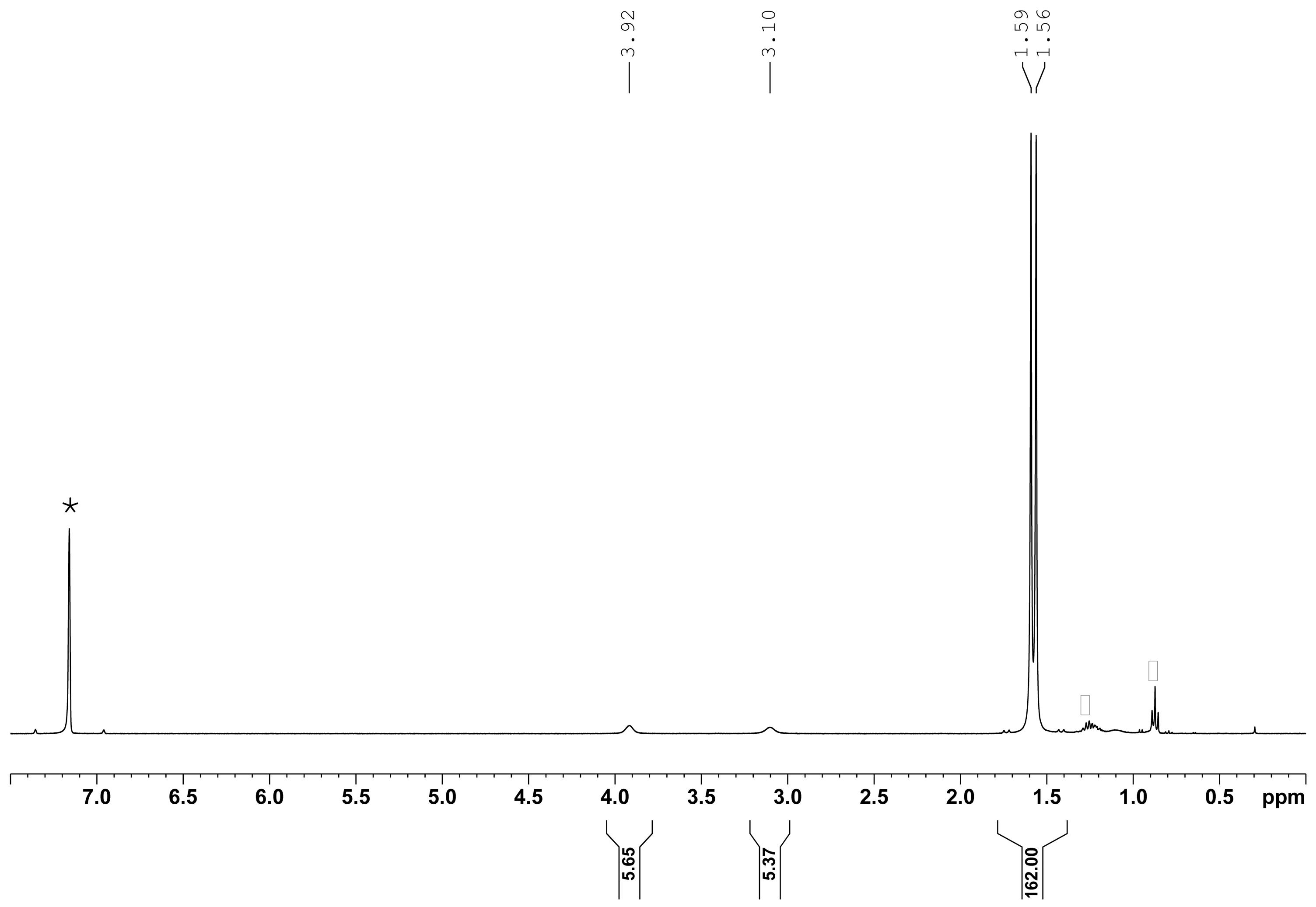

2. Results

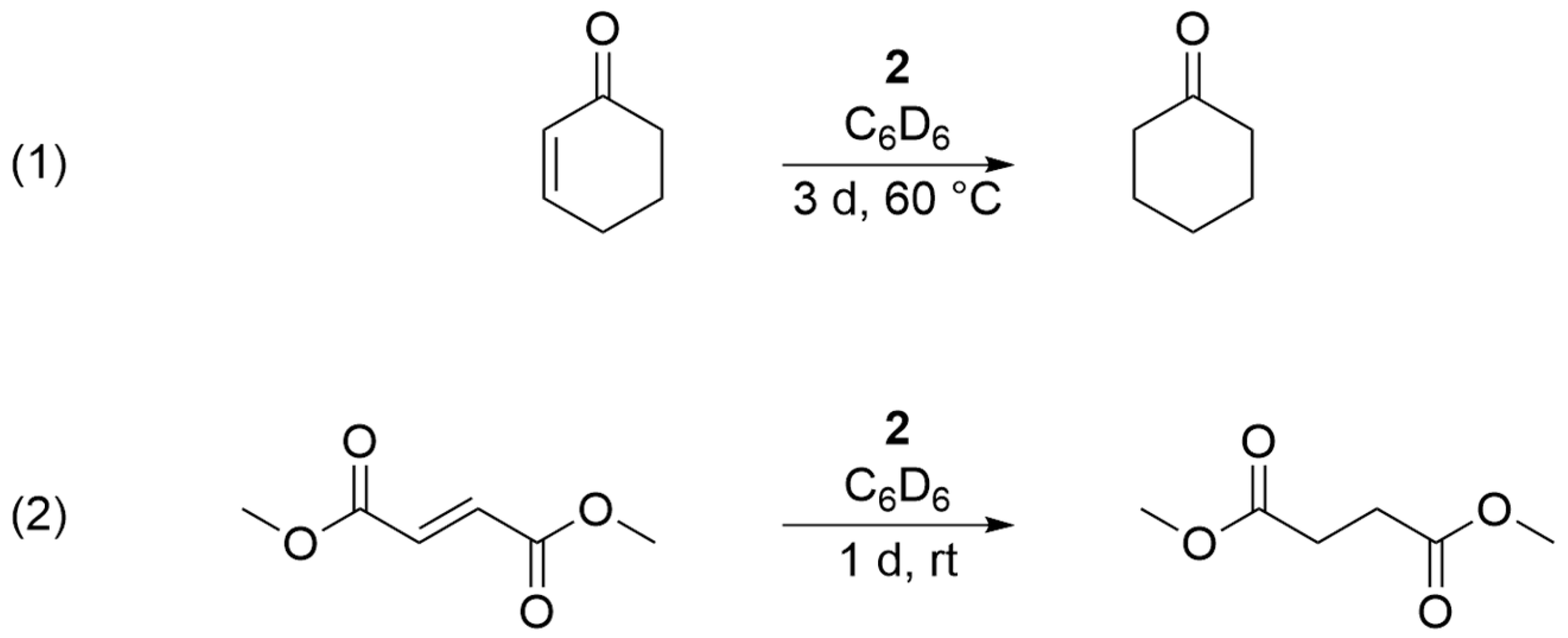

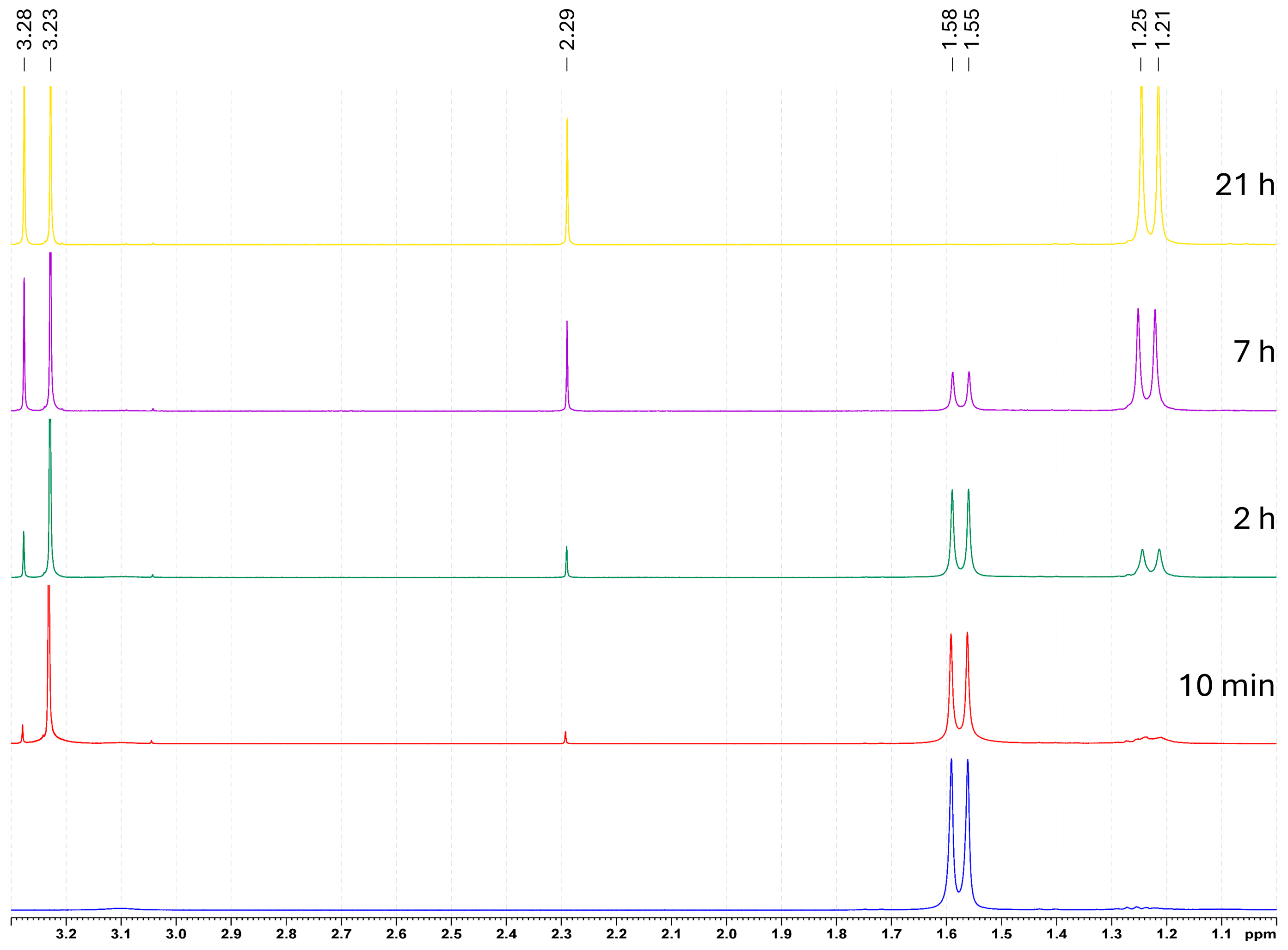

Reactivity Investigation

3. Materials and Methods

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NMR | Nuclear magnetic resonance |

| Bu | Butyl |

| Me | Methyl |

| Ph | Phenyl |

| Pr | Propyl |

| Tol | Tolyl |

References

- Blaser, H.-U.; Malan, C.; Pugin, B.; Spindler, F.; Steiner, H.; Studer, M. Selective Hydrogenation for Fine Chemicals: Recent Trends and New Developments. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2003, 345, 103–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraft, S.; Ryan, K.; Kargbo, R.B. Recent Advances in Asymmetric Hydrogenation of Tetrasubstituted Olefins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 11630–11641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; Astruc, D. The Golden Age of Transfer Hydrogenation. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 6621–6686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, J.; Wang, F.; Zhang, X. Asymmetric hydrogenation catalyzed by first-row transition metal complexes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 3211–3237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahoney, W.S.; Brestensky, D.M.; Stryker, J.M. Selective hydride-mediated conjugate reduction of. alpha.,. beta.-unsaturated carbonyl compounds using [(Ph3P)CuH]6. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1988, 110, 291–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klinkhammer, K.W.; Xiong, Y.; Yao, S. Molecular Lead Clusters—From Unexpected Discovery to Rational Synthesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004, 43, 6202–6204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesamoorthy, C.; Weßing, J.; Kroll, C.; Seidel, R.W.; Gemel, C.; Fischer, R.A. The Intermetalloid Cluster [(Cp*AlCu)6H4], Embedding a Cu6 Core Inside an Octahedral Al6 Shell: Molecular Models of Hume–Rothery Nanophases. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 7943–7947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezman, S.A.; Churchill, M.R.; Osborn, J.A.; Wormald, J. Preparation and crystallographic characterization of a hexameric triphenylphosphinecopper hydride cluster. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1971, 93, 2063–2065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemmen, T.H.; Folting, K.; Huffman, J.C.; Caulton, K.G. Copper polyhydrides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1985, 107, 7774–7775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, R.C.; McLean, M.R.; Bau, R.; Koetzle, T.F. Neutron diffraction structure analysis of a hexanuclear copper hydrido complex, H6Cu6[P(p-tolyl)3]6: An unexpected finding. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1989, 111, 3472–3473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, E.L.; Murphy, P.J.; Imberti, S.; Parker, S.F. Characterization of the Hydrides in Stryker’s Reagent: [HCu{P(C6H5)3}]6. Inorg. Chem. 2014, 53, 2963–2967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jha, K.K.; Rothbaum, J.O.; Bhethanabotla, V.C.; Musgrave, C.B., III; Jones, C.G.; Morozov, S.I.; Goddard, W.A., III; Nelson, H.M. Comparative Study of Solvatomorphs of Stryker’s Reagent Using MicroED and Quantum Mechanics. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2025, 64, e202502524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehnen, S.; Eichhöfer, A.; Fenske, D. Chalcogen-Bridged Copper Clusters. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2002, 2002, 279–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhayal, R.S.; van Zyl, W.E.; Liu, C.W. Polyhydrido Copper Clusters: Synthetic Advances, Structural Diversity, and Nanocluster-to-Nanoparticle Conversion. Acc. Chem. Res. 2016, 49, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, A.K.; Orthaber, A. Alkynyl Coinage Metal Clusters and Complexes–Syntheses, Structures, and Strategies. Chem. Eur. J. 2018, 24, 7536–7559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.-A.D.; Jones, Z.R.; Goldsmith, B.R.; Buratto, W.R.; Wu, G.; Scott, S.L.; Hayton, T.W. A Cu25 Nanocluster with Partial Cu(0) Character. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 13319–13324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxl, T.; Scheid, D.; Linti, G. Synthesis and Structure of a Metal-Rich Tetradecagallium Cluster with a Polyhedral Core. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2025, 28, e202400725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purath, A.; Dohmeier, C.; Ecker, A.; Köppe, R.; Krautscheid, H.; Schnöckel, H.; Ahlrichs, R.; Stoermer, C.; Friedrich, J.; Jutzi, P. Synthesis and Structure of a Neutral SiAl14 Cluster. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 6955–6959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, M.; Hartig, J.; Koch, K.; Schnöckel, H. Si@Al14(N(Dipp)SiMe3)6: A Si-Centered Metalloid Aluminum Cluster and the Reinvestigation of Si@Al14Cp*6. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 2009, 635, 423–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brynda, M.; Herber, R.; Hitchcock, P.B.; Lappert, M.F.; Nowik, I.; Power, P.P.; Protchenko, A.V.; Růžička, A.; Steiner, J. Higher-Nuclearity Group 14 Metalloid Clusters: [Sn9{Sn(NRR′)}6]. Angew. Chem. 2006, 118, 4439–4443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, J.-H.; Brocha Silalahi, R.P.; Chiu, T.-H.; Liu, C.W. Locating Interstitial Hydrides in MH2@Cu14 (M = Cu, Ag) Clusters by Single-Crystal X-ray Diffraction. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 31541–31547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brocha Silalahi, R.P.; Huang, G.-R.; Liao, J.-H.; Chiu, T.-H.; Chakrahari, K.K.; Wang, X.; Cartron, J.; Kahlal, S.; Saillard, J.-Y.; Liu, C.W. Copper Clusters Containing Hydrides in Trigonal Pyramidal Geometry. Inorg. Chem. 2020, 59, 2536–2547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, C.; Wang, Z.; Guo, R.; Ding, Y.; Ma, S.; Sun, X. Machine Learning Potential for Copper Hydride Clusters: A Neutron Diffraction-Independent Approach for Locating Hydrogen Positions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2025, 147, 10750–10757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wu, Z.; Dai, S.; Jiang, D. Deep Learning Accelerated Determination of Hydride Locations in Metal Nanoclusters. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 12289–12292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goeden, G.V.; Caulton, K.G. Soluble copper hydrides: Solution behavior and reactions related to carbon monoxide hydrogenation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1981, 103, 7354–7355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.-Y.; Goyal, P.; Girshick, R.B.; He, K.; Dollár, P. Focal Loss for Dense Object Detection. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2020, 42, 318–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gienger, C.; Schynowski, L.; Schaefer, J.; Schrenk, C.; Schnepf, A. New Intermetalloid Ge9-clusters with Copper and Gold: Filling Vacancies in the Cluster Chemistry of [Ge9(Hyp)3]− (Hyp=Si(SiMe3)3). Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2023, 26, e202200738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldrick, G.M. SADABS: Program for Empirical Absorption Correction of Area Detector Data; University of Göttingen: Göttingen, Germany, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Sheldrick, G.M. A short history of SHELX. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. A Found. Crystallogr. 2008, 64, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolomanov, O.V.; Bourhis, L.J.; Gildea, R.J.; Howard, J.A.K.; Puschmann, H. OLEX2: A complete structure solution, refinement and analysis program. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2009, 42, 339–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hübschle, C.B.; Sheldrick, G.M.; Dittrich, B. ShelXle: A Qt graphical user interface for SHELXL. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2011, 44, 1281–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldrick, G.M. Crystal structure refinement with SHELXL. Acta Crystallogr. C 2015, 71, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasubramani, S.G.; Chen, G.P.; Coriani, S.; Diedenhofen, M.; Frank, M.S.; Franzke, Y.J.; Furche, F.; Grotjahn, R.; Harding, M.E.; Hättig, C.; et al. TURBOMOLE: Modular program suite for ab initio quantum-chemical and condensed-matter simulations. J. Chem. Phys. 2020, 152, 184107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffen, C.; Thomas, K.; Huniar, U.; Hellweg, A.; Rubner, O.; Schroer, A. TmoleX—A graphical user interface for TURBOMOLE. J. Comput. Chem. 2010, 31, 2967–2970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Strienz, M.; Kimmich, R.; Conzelmann, A.; Schnepf, A. Cu14H12(PtBu3)6Cl2—The Expanse of Stryker’s Reagent. Molecules 2025, 30, 4779. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244779

Strienz M, Kimmich R, Conzelmann A, Schnepf A. Cu14H12(PtBu3)6Cl2—The Expanse of Stryker’s Reagent. Molecules. 2025; 30(24):4779. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244779

Chicago/Turabian StyleStrienz, Markus, Roman Kimmich, Alexander Conzelmann, and Andreas Schnepf. 2025. "Cu14H12(PtBu3)6Cl2—The Expanse of Stryker’s Reagent" Molecules 30, no. 24: 4779. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244779

APA StyleStrienz, M., Kimmich, R., Conzelmann, A., & Schnepf, A. (2025). Cu14H12(PtBu3)6Cl2—The Expanse of Stryker’s Reagent. Molecules, 30(24), 4779. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244779