Theoretical Calculations on Hexagonal-Boron-Nitride-(h-BN)-Supported Single-Atom Cu for the Reduction of Nitrate to Ammonia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. h-BN-Supported Singe-Atom Cu

2.2. Band Structure and DOS

2.3. NO3 Adsorption

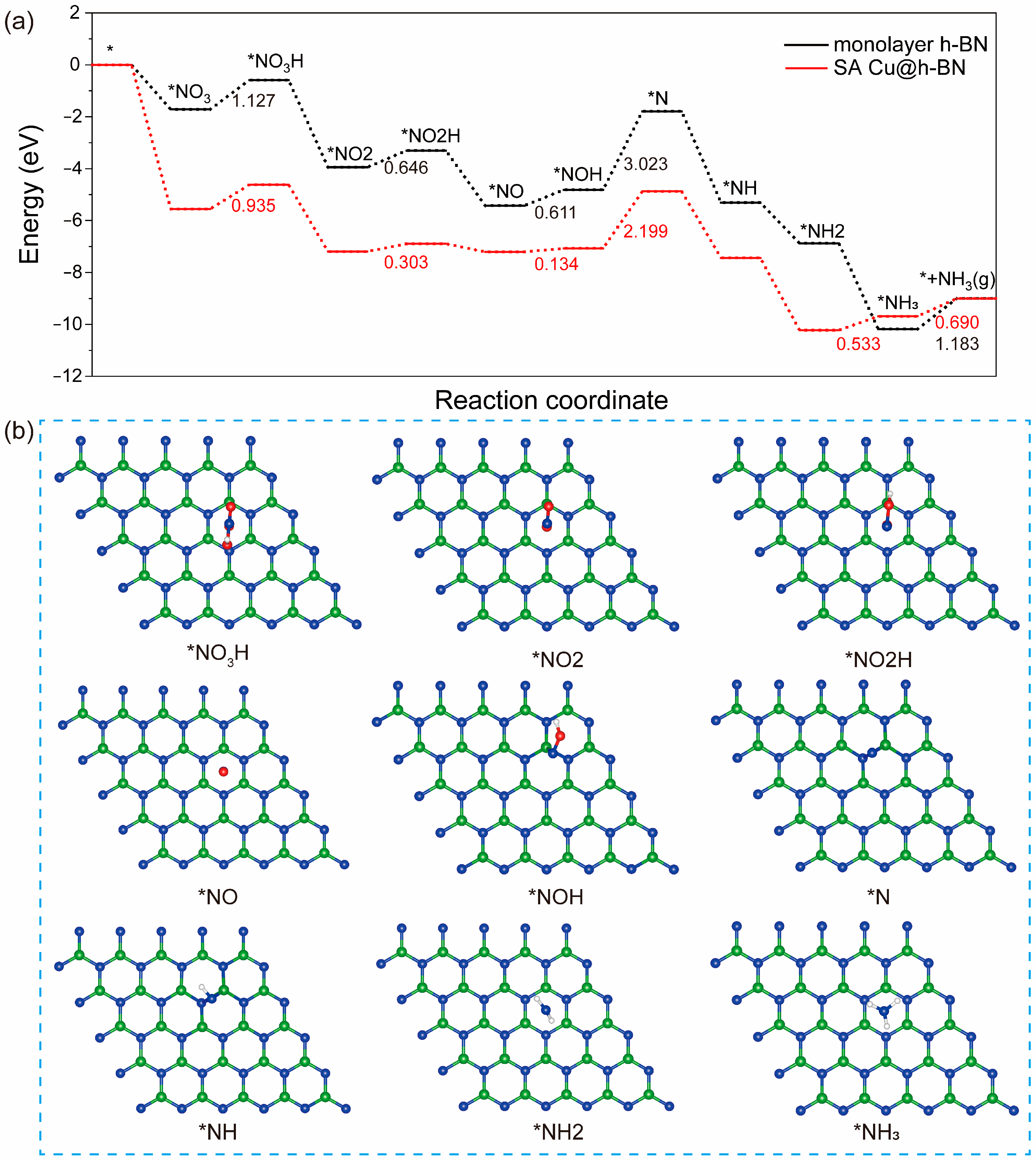

2.4. NO3 Reduction to NH3

3. Computational Details

4. Conclusions

- 1.

- The Cu atom is preferentially loaded at the N top site of monolayer h-BN, which is because of the stronger electronegativity of the N atom than that of the B atom.

- 2.

- The Cu atom supported on monolayer h-BN can enhance electroconductibility, reduce the bandgap width, and increase the reducibility due to its abundant 3d-orbital electrons

- 3.

- On monolayer h-BN, the NO3− ion preferentially adsorbs at the hollow site, while on SA Cu@h-BN, the NO3− ion is adsorbed more strongly at the Cu top site.

- 4.

- The rate-determining steps during the reduction of *NO3 to *N and the hydrogenation of *N to NH3 are the reduction step of *NOH to *N and the dissociation step of NH3, respectively. Due to the strong reducing capacity of the d-orbital electrons of the Cu atom, the energy barrier of the RDS can be significantly decreased. Consequently, SA Cu@h-BN exhibits excellent catalytic performance of NO3RR.

- 5.

- The theoretical calculations in this paper can provide theoretical guidance for the development of h-BN-supported single-atom metal catalysts.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xu, H.; Ma, Y.; Chen, J.; Zhang, W.-X.; Yang, J. Electrocatalytic reduction of nitrate—A step towards a sustainable nitrogen cycle. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2022, 51, 2710–2758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Qiao, L.; Peng, S.; Bai, H.; Liu, C.; Ip, W.F.; Lo, K.H.; Liu, H.; Ng, K.W.; Wang, S.; et al. Recent Advances in Electrocatalysts for Efficient Nitrate Reduction to Ammonia. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 33, 2303480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Z.; Wang, G. Rational electrocatalyst design for selective nitrate reduction to ammonia. Chem. Phys. Rev. 2025, 6, 011307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Wang, W.; Xu, S.; Sun, Q.; Shi, W.; Man, J.; Yu, S.; Yang, Y.; Wu, W.; Hu, X.; et al. Effectively mitigated eutrophication risk by strong biological carbon pump (BCP) effect in karst reservoirs. Water Res. 2025, 278, 123395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, C.; Wang, S.; Wang, H.; Hu, X.; Yang, F.; Tang, M.; Zhang, M.; Zhong, J. Internal nitrogen and phosphorus loading in a seasonally stratified reservoir: Implications for eutrophication management of deep-water ecosystems. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 319, 115681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noori, R.; Farahani, F.; Jun, C.; Aradpour, S.; Bateni, S.M.; Ghazban, F.; Hosseinzadeh, M.; Maghrebi, M.; Vesali Naseh, M.R.; Abolfathi, S. A non-threshold model to estimate carcinogenic risk of nitrate-nitrite in drinking water. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 363, 132432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamlin, Q.F.; Martin, S.L.; Kendall, A.D.; Hyndman, D.W. Examining Relationships Between Groundwater Nitrate Concentrations in Drinking Water and Landscape Characteristics to Understand Health Risks. GeoHealth 2022, 6, e2021GH000524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Xu, H.-M.; Zhu, H.-R.; Huang, C.-J.; Zhang, Z.-J.; Li, G.-R. Recent advances in electrocatalytic reduction of nitrate to ammonia: Current challenges, resolving strategies, and future perspectives. J. Mater. Chem. A 2025, 13, 21181–21232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, J.; Liu, F.; Hao, F.; Fan, Z. Electrochemical Nitrate Reduction: Ammonia Synthesis and the Beyond. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 2304021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Xu, Y.; Liu, J.; Cao, H.; Li, Y.; Ren, X.; Ye, S.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Q. Recent developments in Ti-based nanocatalysts for electrochemical nitrate-to-ammonia conversion. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2023, 10, 4901–4917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Li, H.; Li, T.; Chen, F.; Yang, R.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, B. Ultralow overpotential nitrate reduction to ammonia via a three-step relay mechanism. Nat. Catal. 2023, 6, 402–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Sun, C.; Ding, G.; Zhao, M.; Ge, X.; Zhang, W.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Jiang, Q. Synergistically tuning intermediate adsorption and promoting water dissociation to facilitate electrocatalytic nitrate reduction to ammonia over nanoporous Ru-doped Cu catalyst. Sci. China Mater. 2023, 66, 4387–4395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, L.; Narouz, M.R.; Smith, P.T.; De La Torre, P.; Chang, C.J. Supramolecular enhancement of electrochemical nitrate reduction catalyzed by cobalt porphyrin organic cages for ammonia electrosynthesis in water. Angew. Chem. 2023, 135, e202305719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosca, V.; Duca, M.; de Groot, M.T.; Koper, M.T.M. Nitrogen Cycle Electrocatalysis. Chem. Rev. 2009, 109, 2209–2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Yung, K.-F.; Yang, H.; Liu, B. Emerging single-atom catalysts in the detection and purification of contaminated gases. Chem. Sci. 2024, 15, 6285–6313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Hong, R.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, H.; Wu, X.; Wu, Z. Single-Atom Catalysts in Environmental Engineering: Progress, Outlook and Challenges. Molecules 2023, 28, 3865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, T.; Liang, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Deng, J.; Yuan, J.; Xiong, W.; Song, B.; Zhou, C.; Yang, Y. Transition Metal Single-Atom Catalysts for the Electrocatalytic Nitrate Reduction: Mechanism, Synthesis, Characterization, Application, and Prospects. Small 2023, 19, 2303732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhe, L.; Chuanju, Y.; Bin, X.; Li, Y.; Wenlei, Z.; Yibin, C. Electrochemically nitrate remediation by single-atom catalysts: Advances, mechanisms, and prospects. Energy Mater. 2024, 4, 400046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.-Y.; Karamad, M.; Yong, X.; Huang, Q.; Cullen, D.A.; Zhu, P.; Xia, C.; Xiao, Q.; Shakouri, M.; Chen, F.-Y.; et al. Electrochemical ammonia synthesis via nitrate reduction on Fe single atom catalyst. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 2870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; Ren, X.; Liu, X.; Kuang, X.; Wang, H.; Zhang, C.; Wei, Q.; Wu, D. Zn single atom on N-doped carbon: Highly active and selective catalyst for electrochemical reduction of nitrate to ammonia. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 452, 139533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Tang, C.; Gong, J. Theoretically identifying the electrocatalytic activity and mechanism of Zn doped 2D h-BN for nitrate reduction to NH3. Chem. Commun. 2022, 58, 7156–7159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.; Wang, C.; Wang, M.; Li, C.M.; Guo, C. Theoretical Insights into Superior Nitrate Reduction to Ammonia Performance of Copper Catalysts. ACS Catal. 2021, 11, 14417–14427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoekx, S.; Daems, N.; Arenas Esteban, D.; Bals, S.; Breugelmans, T. Toward the Rational Design of Cu Electrocatalysts for Improved Performance of the NO3RR. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2024, 7, 3761–3775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, T.; Chen, Q.; Liao, P.; Duan, W.; Liang, S.; Yan, Z.; Feng, C. Single-Atom Cu Catalysts for Enhanced Electrocatalytic Nitrate Reduction with Significant Alleviation of Nitrite Production. Small 2020, 16, 2004526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, X.S.; Jeon, K.-W.; Fang, L.; de Graaf, K.; Espinosa, B.I.; Parker, S.D.T.; Piao, H.; Li, T.; Wang, X. Boron Nitride Supported Copper Single Atom Catalyst for Nitrate Reduction Reaction. Catal. Today 2025, 459, 115381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kan, A.; Duan, Y.; Guo, J.; Wu, T.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Luo, Q.; Lu, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Liang, Y.; et al. Cobalt single atom induced catalytic active site shift in carbon-doped BN for efficient photodriven CO2 reduction. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2023, 616, 156451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Chen, Z. Single Mo Atom Supported on Defective Boron Nitride Monolayer as an Efficient Electrocatalyst for Nitrogen Fixation: A Computational Study. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 12480–12487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Ye, X.; Johnson, R.S.; Guo, H. First-Principles Investigations of Metal (Cu, Ag, Au, Pt, Rh, Pd, Fe, Co, and Ir) Doped Hexagonal Boron Nitride Nanosheets: Stability and Catalysis of CO Oxidation. J. Phys. Chem. C 2013, 117, 17319–17326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Zhang, H.; Song, Q.; Liu, Z.; Xia, J.; Yan, B.; Meng, X.; Jiang, Z.; Wen Lou, X.; Lee, C.-S. Modulating Charge Separation of Oxygen-doped Boron Nitride with Isolated Co Atoms for Enhancing CO2-To-CO Photoreduction. Adv. Mater. 2023, 36, 2303287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asif, Q.u.A.; Hussain, A.; Nabi, A.; Tayyab, M.; Rafique, H.M. Computational study of X-doped hexagonal boron nitride (h-BN): Structural and electronic properties (X = P, S, O, F, Cl). J. Mol. Model. 2021, 27, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, B.D. Tuning the magnetic and electronic properties of monolayer SnS2 by 3d transition metal doping: A DFT study. Mater. Today Commun. 2022, 33, 104626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Tang, C.; Li, Q.; Xiao, T.; Xiong, F. Theoretical prediction of efficient Cu-based dual-atom alloy catalysts for electrocatalytic nitrate reduction to ammonia via high-throughput first-principles calculations. J. Mater. Chem. A 2025, 13, 3765–3776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohenberg, P.; Kohn, W. Inhomogeneous Electron Gas. Phys. Rev. 1964, 136, B864–B871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohn, W.; Sham, L.J. Self-Consistent Equations Including Exchange and Correlation Effects. Phys. Rev. 1965, 140, A1133–A1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hongzhiwei Technology. Device Studio; Version 2023B; Hongzhiwei Technology: Shanghai, China, 2023; Available online: https://cloud.hzwtech.com/web/home (accessed on 1 September 2024).

- Blöchl, P.E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 1994, 50, 17953–17979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimme, S.; Antony, J.; Ehrlich, S.; Krieg, H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 2010, 132, 154104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tkatchenko, A.; Scheffler, M. Accurate Molecular Van Der Waals Interactions from Ground-State Electron Density and Free-Atom Reference Data. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2009, 102, 073005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| System | Initial Adsorption Site | Eads (eV) | Shifting to |

|---|---|---|---|

| monolayer h-BN | B top | −1.712 | / |

| N top | −1.701 | / | |

| bridge | −1.711 | B top | |

| hollow | −1.715 | / | |

| SA Cu@h-BN | Cu top | −5.554 | / |

| System | h-BN | SA Cu@h-BN |

|---|---|---|

| *NO3 | −1.715 | −5.554 |

| *NO3H | −0.589 | −4.618 |

| *NO2 | −3.945 | −7.195 |

| *NO2H | −3.299 | −6.892 |

| *NO | −5.425 | −7.207 |

| *NOH | −4.813 | −7.073 |

| *N | −1.791 | −4.874 |

| *NH | −5.308 | −7.437 |

| *NH2 | −6.877 | −10.223 |

| *NH3 | −10.184 | −9.691 |

| *+NH3 | −9.001 | −9.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, G.; Hao, C. Theoretical Calculations on Hexagonal-Boron-Nitride-(h-BN)-Supported Single-Atom Cu for the Reduction of Nitrate to Ammonia. Molecules 2025, 30, 4700. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244700

Liu G, Hao C. Theoretical Calculations on Hexagonal-Boron-Nitride-(h-BN)-Supported Single-Atom Cu for the Reduction of Nitrate to Ammonia. Molecules. 2025; 30(24):4700. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244700

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Guoliang, and Cen Hao. 2025. "Theoretical Calculations on Hexagonal-Boron-Nitride-(h-BN)-Supported Single-Atom Cu for the Reduction of Nitrate to Ammonia" Molecules 30, no. 24: 4700. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244700

APA StyleLiu, G., & Hao, C. (2025). Theoretical Calculations on Hexagonal-Boron-Nitride-(h-BN)-Supported Single-Atom Cu for the Reduction of Nitrate to Ammonia. Molecules, 30(24), 4700. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244700