Influence of Electrode Polishing Protocols, Potentiostat Models, and LOD Calculation Methods on the Electroanalytical Performance of SWV Measurements at Glassy Carbon Electrodes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

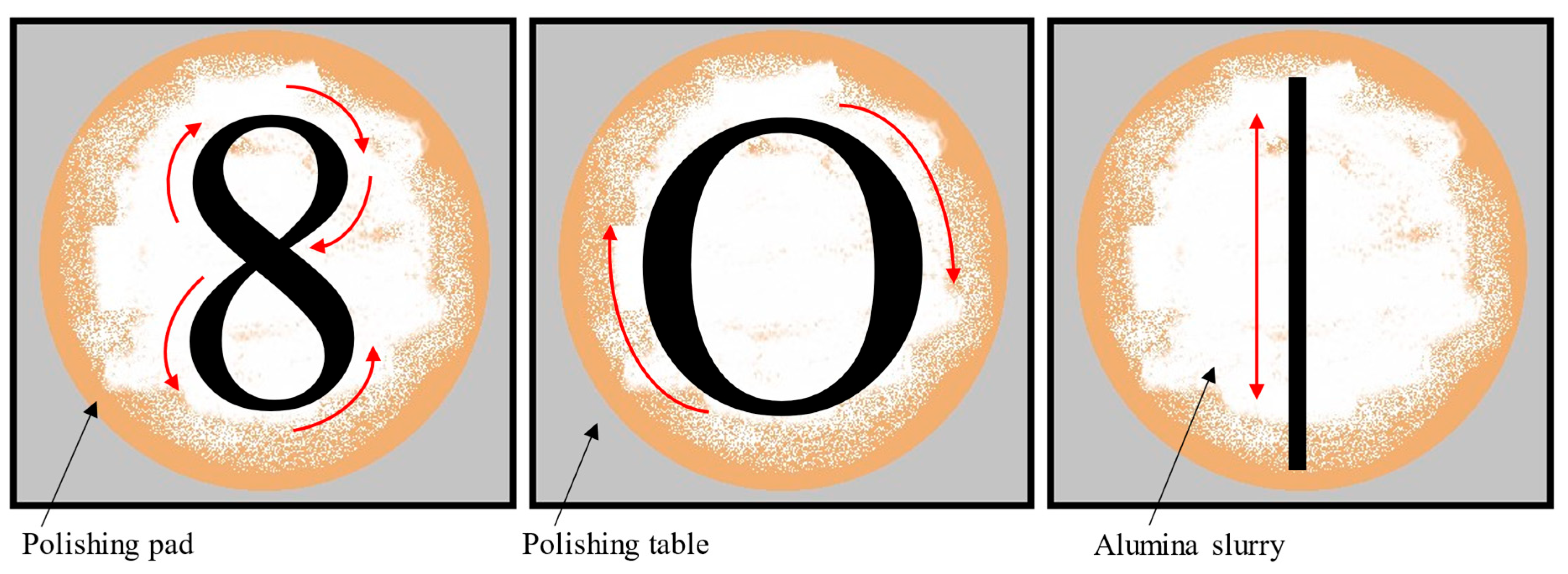

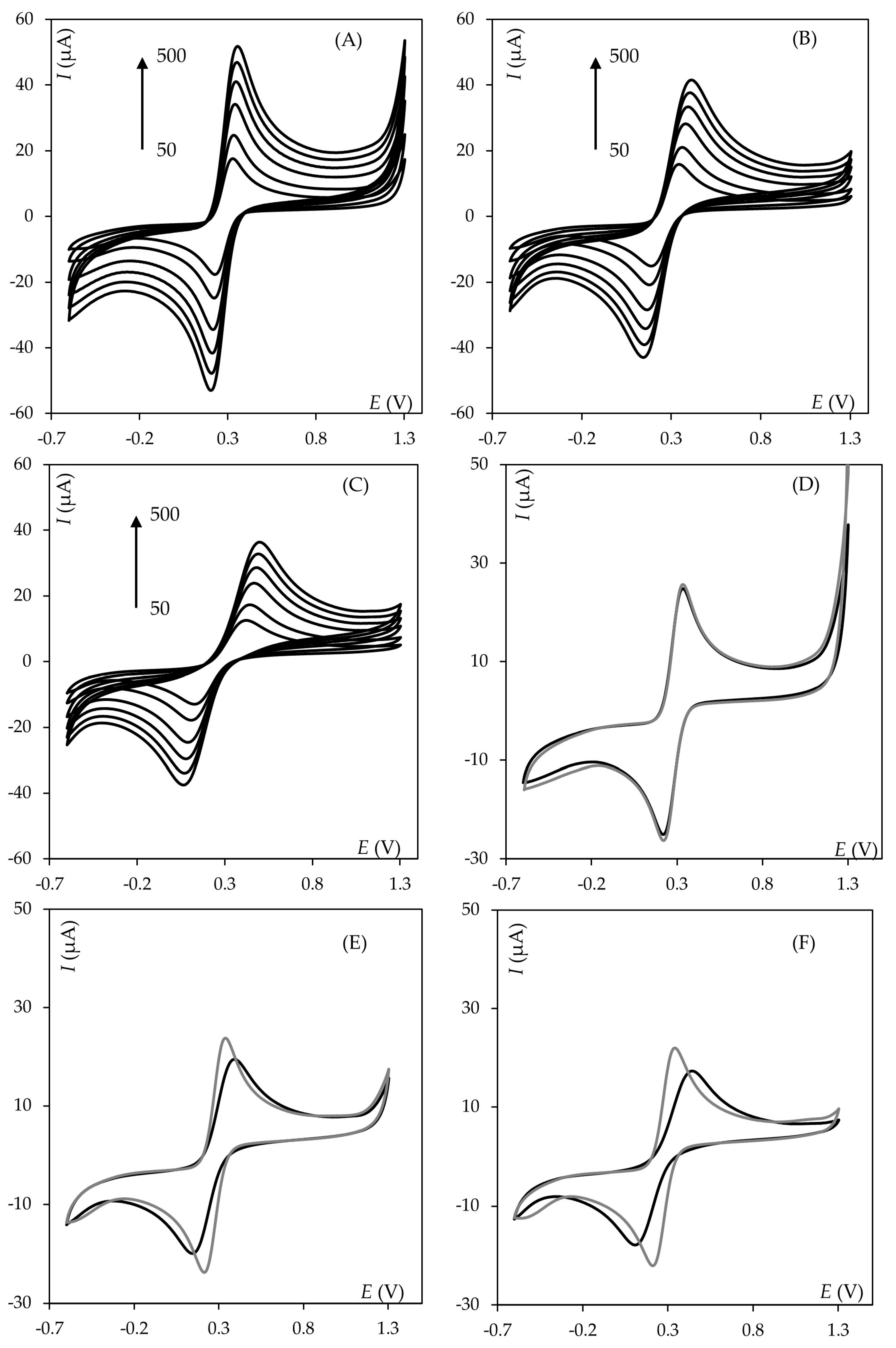

2.1. Influence of Polishing Motion Type

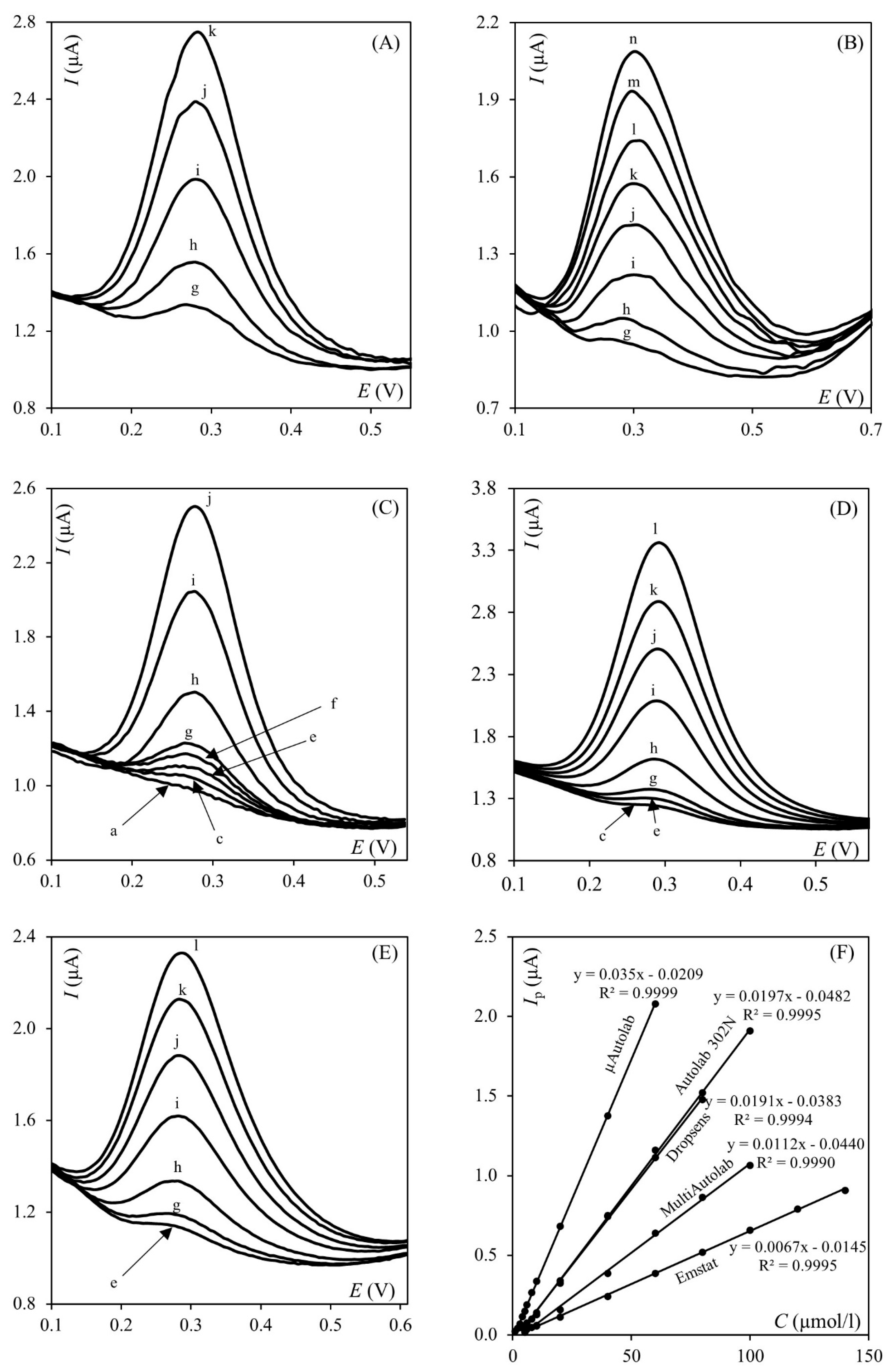

2.2. Influence of Apparatus

2.3. Influence of LOD Calculation Method

3. Experimental

3.1. Apparatus and Solutions

3.2. Equations

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, J. Analytical Electrochemistry, 2nd ed.; Wiley-VCH: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Ozkan, S.A.; Kauffmann, J.M.; Zuman, P. Electroanalysis in Biomedical and Pharmaceutical Sciences; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bard, A.J.; Faulkner, L.R.; White, H.S. Electrochemical Methods: Fundamentals and Applications; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Scholz, F. Electroanalytical Methods, Guide to Experiments and Applications; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Barek, J.; Fogg, A.G.; Muck, A.; Zima, J. Polarography and Voltammetry at Mercury Electrodes. Crit. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2001, 31, 291–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekanski, A.; Stevanović, J.; Stevanović, R.; Nikolić, B.Ž.; Jovanović, V.M. Glassy carbon electrodes: I. Characterization and electrochemical activation. Carbon 2001, 39, 1195–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavazalova, J.; Prochazkova, K.; Schwarzova-Peckova, K. Boron-doped Diamond Electrodes for Voltammetric Determination of Benzophenone-3. Anal. Lett. 2016, 49, 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vytřas, K.; Švancara, I.; Metelka, R. Carbon paste electrodes in electroanalytical chemistry. J. Serbian Chem. Soc. 2009, 74, 1021–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokoskarova, P.; Stojanov, L.; Najkov, K.; Ristovska, N.; Ruskovska, T.; Skrzypek, S.; Mirceski, V. Square-wave voltammetry of human blood serum. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 8485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miah, M.R.; Alam, M.T.; Ohsaka, T. Sulfur-adlayer-coated gold electrode for the in vitro electrochemical detection of uric acid in urine. Anal. Chim. Acta 2010, 669, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Festinger, N.; Kisielewska, A.; Burnat, B.; Ranoszek-Soliwoda, K.; Grobelny, J.; Koszelska, K.; Guziejewski, D.; Smarzewska, S. The Influence of Graphene Oxide Composition on Properties of Surface-Modified Metal Electrodes. Materials 2022, 15, 7684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palisoc, S.; Vitto, R.I.M.; Natividad, M. Determination of Heavy Metals in Herbal Food Supplements using Bismuth/Multi-walled Carbon Nanotubes/Nafion modified Graphite Electrodes sourced from Waste Batteries. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 18491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Qian, D.; Xiao, X.; Gao, S.; Cheng, J.; He, B.; Liao, L.; Deng, J. A highly sensitive and selective sensor based on a graphene-coated carbon paste electrode modified with a computationally designed boron-embedded duplex molecularly imprinted hybrid membrane for the sensing of lamotrigine. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2017, 94, 663–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.-X.; He, Y.-B.; Lai, L.-N.; Li, J.-B.; Song, X.-L. Electrochemical sensors using gold submicron particles modified electrodes based on calcium complexes formed with alizarin red S for determination of Ca2+ in isolated rat heart mitochondria. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2015, 66, 417–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarei, K.; Khodadadi, A. Very sensitive electrochemical determination of diuron on glassy carbon electrode modified with reduced graphene oxide–gold nanoparticle–Nafion composite film. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2017, 144, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassoux, P.; Valade, L.; Fabre, P.L. Comprehensive Coordination Chemistry II; McCleverty, J.A., Meyer, T.J., Eds.; Pergamon: Oxford, UK, 2003; pp. 761–773. [Google Scholar]

- Compton, R.G.; Banks, C.E. Understanding Voltammetry; World Scientific: Singapore, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hancox, R.N.; Lamb, G.D.; Lehrle, R.S. Sample size dependence in pyrolysis: An embarrassment, or a utility? J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 1991, 19, 333–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swain, G.M. Handbook of Electrochemistry; Zoski, C.G., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2007; pp. 111–153. [Google Scholar]

- Uskoković, V. A historical review of glassy carbon: Synthesis, structure, properties and applications. Carbon Trends 2021, 5, 100116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S. Glassy Carbon: A Promising Material for Micro- and Nanomanufacturing. Materials 2018, 11, 1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noel, M.; Anantharaman, P.N. Voltammetric studies on a glassy carbon electrode. Part II. Factors influencing the simple electron-transfer reactions—The K3[Fe(CN)6]-K4[Fe(CN)6] system. Analyst 1985, 110, 1095–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranganathan, S.; Kuo, T.-C.; McCreery, R.L. Facile Preparation of Active Glassy Carbon Electrodes with Activated Carbon and Organic Solvents. Anal. Chem. 1999, 71, 3574–3580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamau, G.N. Surface preparation of glassy carbon electrodes. Anal. Chim. Acta 1988, 207, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bott, A.W. Practical Problems in Voltammetry: 4. Preparation of Working Electrodes. Curr. Sep. 1997, 16, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Brett, C.M.A.; Brett, A.M.O. Electrochemistry—Principles, Methods and Applications; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1994; Volume 98. [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira, C.A.; Giordano, G.F.; Beltrame, M.B.; Vieira, L.C.S.; Gobbi, A.L.; Lima, R.S. Renewable Solid Electrodes in Microfluidics: Recovering the Electrochemical Activity without Treating the Surface. Anal. Chem. 2016, 88, 11199–11206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guziejewski, D.; Smarzewska, S.; Mirceski, V. Analytical Aspects of Novel Techniques Derived from Square-Wave Voltammetry. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2023, 170, 066503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirceski, V.; Guziejewski, D.; Stojanov, L.; Gulaboski, R. Differential Square-Wave Voltammetry. Anal. Chem. 2019, 91, 14904–14910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadreško, D.; Guziejewski, D.; Mirčeski, V. Electrochemical Faradaic Spectroscopy. ChemElectroChem 2018, 5, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, N.F.A.; Noor, A.M.; Sabani, N.; Zakaria, Z.; Wahab, A.A.; Manaf, A.A.; Johari, S. We-VoltamoStat: A wearable potentiostat for voltammetry analysis with a smartphone interface. HardwareX 2023, 15, e00441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lista, L. Statistical Methods for Data Analysis; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, J.C.; Miller, J.N. Statistical Analytical Chemistry; Ellis Horwood: Chichester, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Krzyczmonik, P.; Socha, E. Budowa, właściwości i zastosowania elektrod nano- i mikrostrukturalnych. Chemik 2015, 69, 11–18. [Google Scholar]

- Takmakov, P.; Zachek, M.K.; Keithley, R.B.; Walsh, P.L.; Donley, C.; McCarty, G.S.; Wightman, R.M. Carbon Microelectrodes with a Renewable Surface. Anal. Chem. 2010, 82, 2020–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Offin, D.G.; Vian, C.J.B.; Birkin, P.; Leighton, T. An assessment of cleaning mechanisms driven by power ultrasound using electrochemistry and high-speed imaging techniques. Hydroacoustics 2008, 11, 299–312. [Google Scholar]

- Trachioti, M.G.; Lazanas, A.C.; Prodromidis, M.I. Shedding light on the calculation of electrode electroactive area and heterogeneous electron transfer rate constants at graphite screen-printed electrodes. Microchim. Acta 2023, 190, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DropSens. Bipotentiostat Μ Stat 200. Available online: https://www.metrohm.com/pl_pl/products/d/s102/ds10200011.html (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Metrohm. Instruments for Electrochemical Research. Available online: https://nlab.pl/uploads/edytor/AUTOLAB/3316826_80005314EN_Autolab_2020.pdf (accessed on 24 July 2025).

- Metrohm. Potencjostat Μautolab Typu III. Available online: http://www.potencialzero.com/media/37501/autolab_uautiii.pdf (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- PalmSens. Emstat3 and 3+ potentiostats—Specifications and Information. Available online: https://www.basinc.com/assets/file_uploads/EmStat-series-description.pdf (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- Isin, D.; Eksin, E.; Erdem, A. Graphene oxide modified single-use electrodes and their application for voltammetric miRNA analysis. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2017, 75, 1242–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Polishing Motion | 8-Type | O-Type | I-Type | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subseries | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| A [cm2] | 0.1007 ± 0.0013 | 0.1010 ± 0.0016 | 0.1009 ± 0.0009 | 0.0942 ± 0.0053 | 0.0927 ± 0.0061 | 0.0894 ± 0.0068 | 0.0889 ± 0.0072 | 0.0915 ± 0.0033 | 0.0901 ± 0.0046 |

| CV [%] | 1.17 | 1.39 | 0.84 | 4.95 | 5.82 | 6.77 | 7.14 | 3.21 | 4.55 |

| Ã [cm2] | 0.1082 ± 0.0007 | 0.0921 ± 0.0033 | 0.0902 ± 0.0027 | ||||||

| Parameter | Potentiostat | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EmStat3 | µStat 200 | µAutolab Type III | Multi Autolab/M101 | Autolab 302N | |

| Maximum current [A] | ±0.02 | ±2 × 10−4 | ±0.08 A | ±0.1 | ±2–20 * |

| Potential range [V] | ±3 | ±2 | ±5 | ±10 | ±30 |

| Potential resolution [µV] | 100 | 1000 | 3 | 3 | 0.3 |

| Current range | 1 nA–10 mA | 1 nA–100 µA | 10 nA–10 mA | 10 nA–10 mA | 10 nA–1 A |

| Number of current ranges | 8 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 9 |

| Price | lowest |  | highest | ||

| Potentiostat | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EmStat3 | µStat 200 | µAutolab Type III | Multi Autolab/M101 | Autolab 302N | |

| Linear range [mol/L] | 1.0 × 10−5– 1.4 × 10−4 | 1.0 × 10−5– 8.0 × 10−5 | 1.0 × 10−6– 6.0 × 10−5 | 5.0 × 10−6– 1.0 × 10−4 | 4.0 × 10−6– 1.0 × 10−4 |

| R2 | 0.99954 | 0.99936 | 0.99987 | 0.99897 | 0.99948 |

| LOD1 [mol/L] | 1.42 × 10−8 | 7.00 × 10−9 | 8.97 × 10−9 | 4.09 × 10−9 | 4.80 × 10−9 |

| LOD2 [mol/L] | 1.51 × 10−8 | 6.85 × 10−9 | 6.06 × 10−9 | 2.02 × 10−9 | 1.52 × 10−9 |

| LOD3 [mol/L] | 2.50 × 10−9 | 1.86 × 10−6 | 2.41 × 10−7 | 2.37 × 10−8 | 8.55 × 10−7 |

| LOD4 [mol/L] | 1.54 × 10−6 | 1.30 × 10−6 | 2.98 × 10−7 | 3.33 × 10−7 | 3.68 × 10−7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Świderski, M.; Seroka, J.; Guziejewski, D.; Krzymiński, P.; Miniak-Górecka, A.; Koszelska, K.; Ullah, N.; Smarzewska, S. Influence of Electrode Polishing Protocols, Potentiostat Models, and LOD Calculation Methods on the Electroanalytical Performance of SWV Measurements at Glassy Carbon Electrodes. Molecules 2025, 30, 4651. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234651

Świderski M, Seroka J, Guziejewski D, Krzymiński P, Miniak-Górecka A, Koszelska K, Ullah N, Smarzewska S. Influence of Electrode Polishing Protocols, Potentiostat Models, and LOD Calculation Methods on the Electroanalytical Performance of SWV Measurements at Glassy Carbon Electrodes. Molecules. 2025; 30(23):4651. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234651

Chicago/Turabian StyleŚwiderski, Michał, Jagoda Seroka, Dariusz Guziejewski, Paweł Krzymiński, Alicja Miniak-Górecka, Kamila Koszelska, Nabi Ullah, and Sylwia Smarzewska. 2025. "Influence of Electrode Polishing Protocols, Potentiostat Models, and LOD Calculation Methods on the Electroanalytical Performance of SWV Measurements at Glassy Carbon Electrodes" Molecules 30, no. 23: 4651. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234651

APA StyleŚwiderski, M., Seroka, J., Guziejewski, D., Krzymiński, P., Miniak-Górecka, A., Koszelska, K., Ullah, N., & Smarzewska, S. (2025). Influence of Electrode Polishing Protocols, Potentiostat Models, and LOD Calculation Methods on the Electroanalytical Performance of SWV Measurements at Glassy Carbon Electrodes. Molecules, 30(23), 4651. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234651