Novel Organosilicon Tetramers with Dialkyl-Substituted [1]Benzothieno[3,2-b]benzothiophene Moieties for Solution-Processible Organic Electronics

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

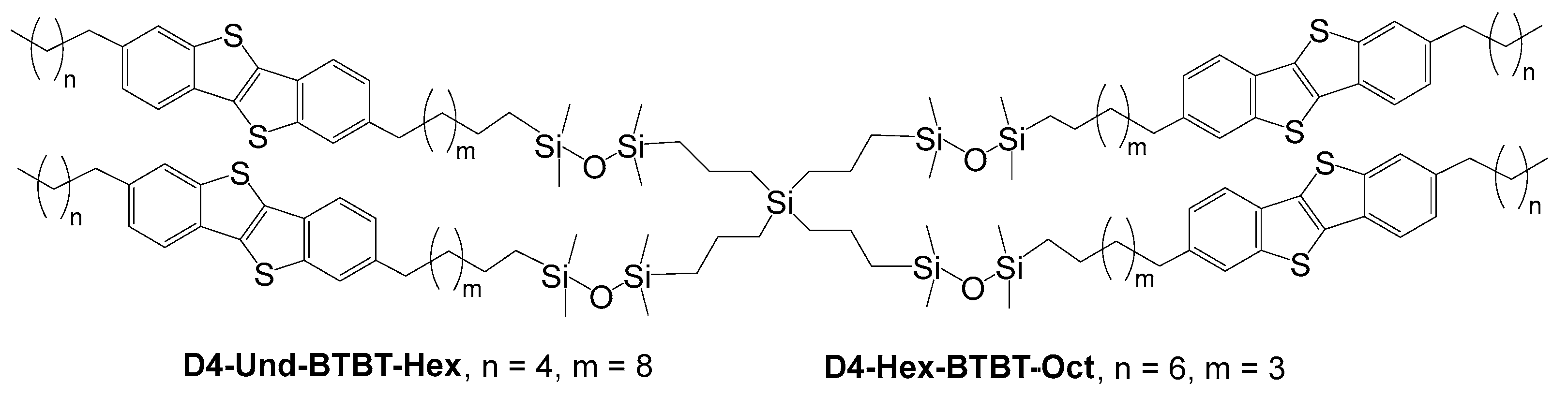

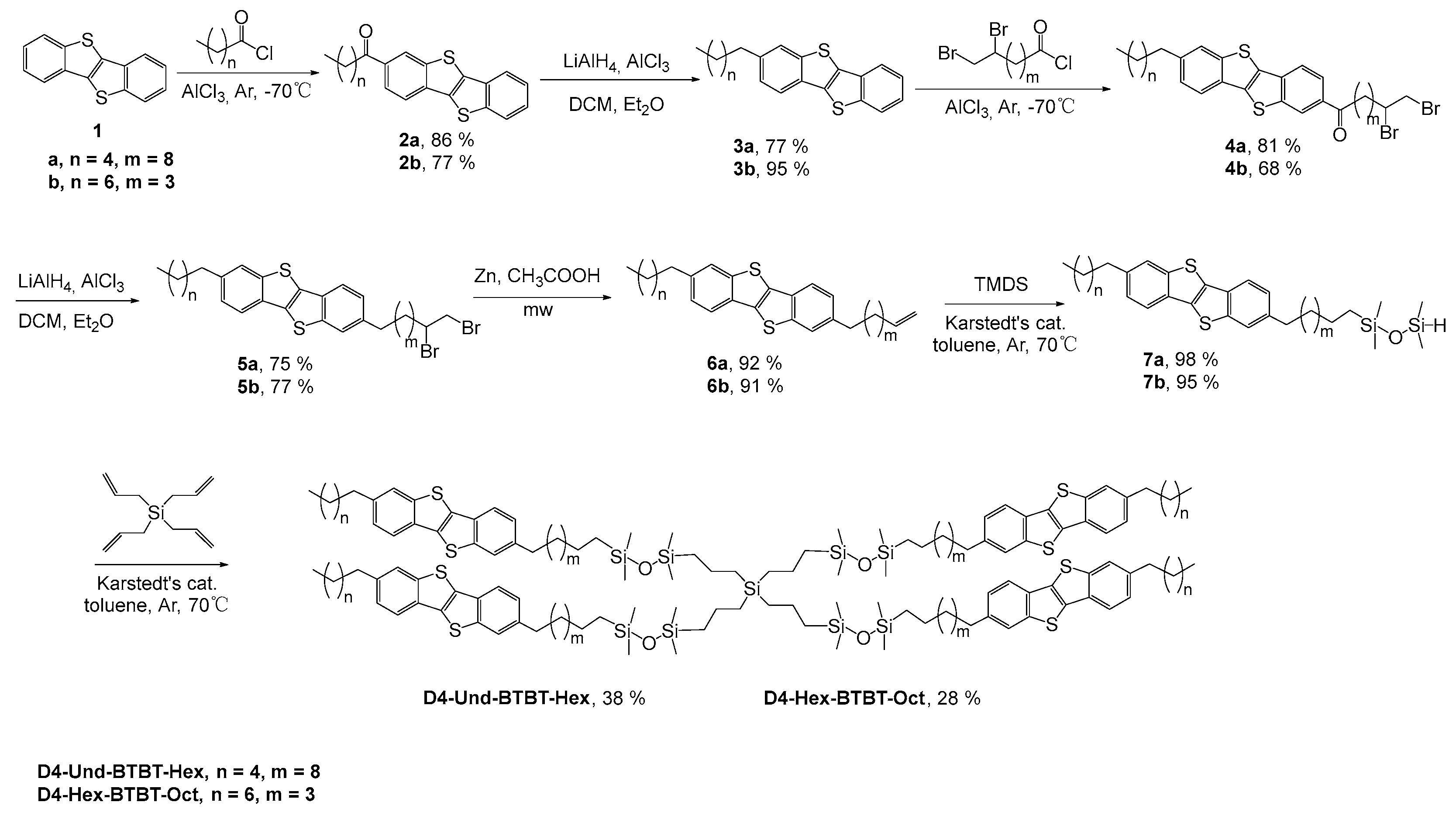

2.1. Synthesis

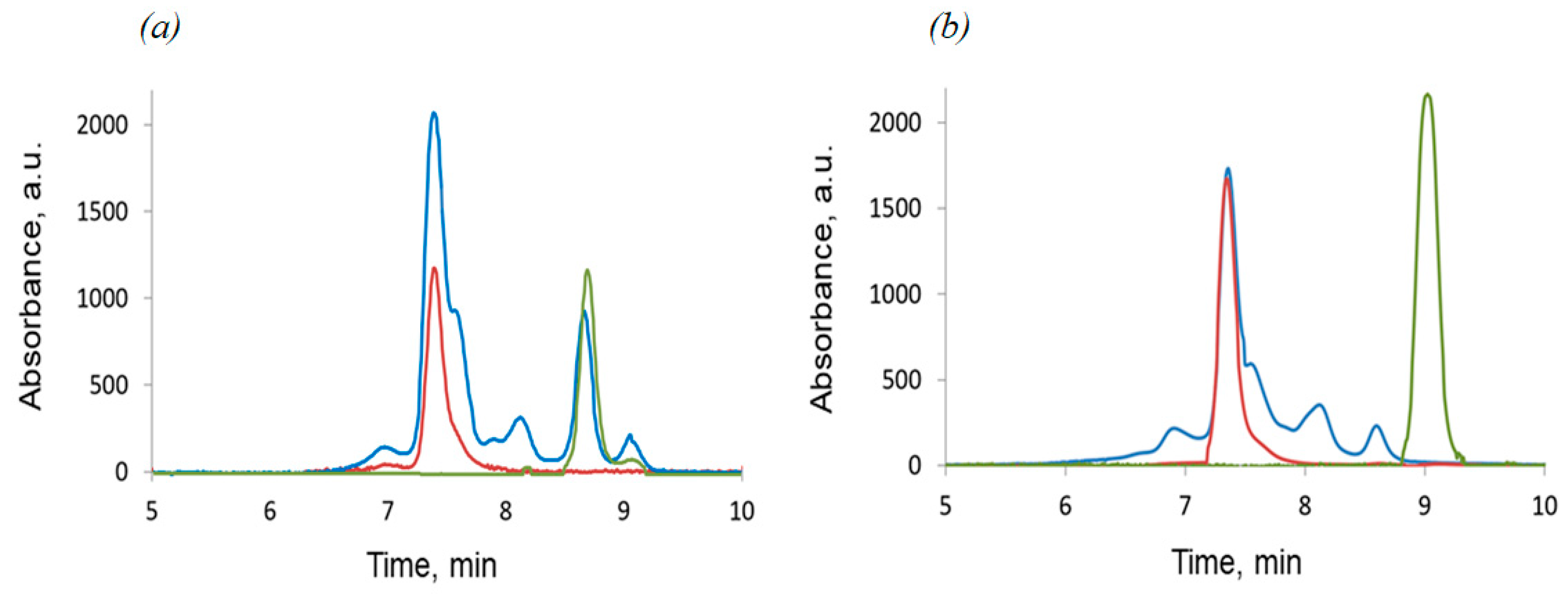

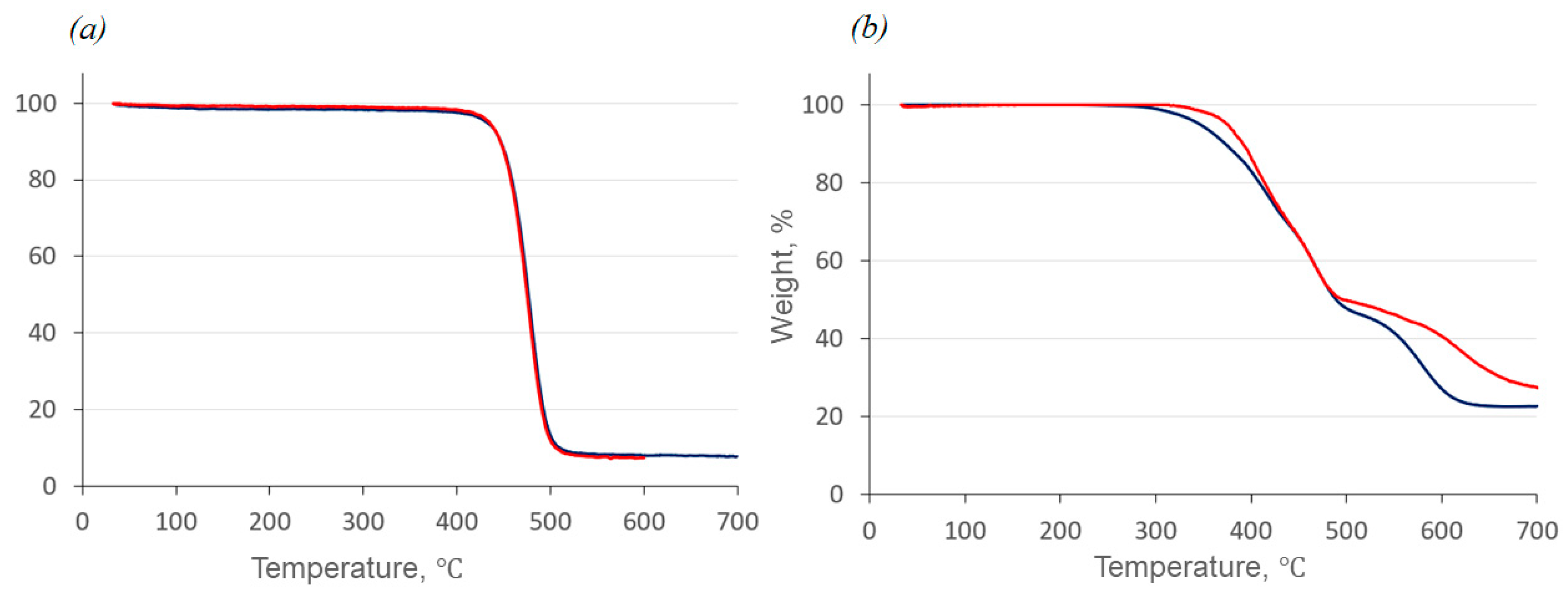

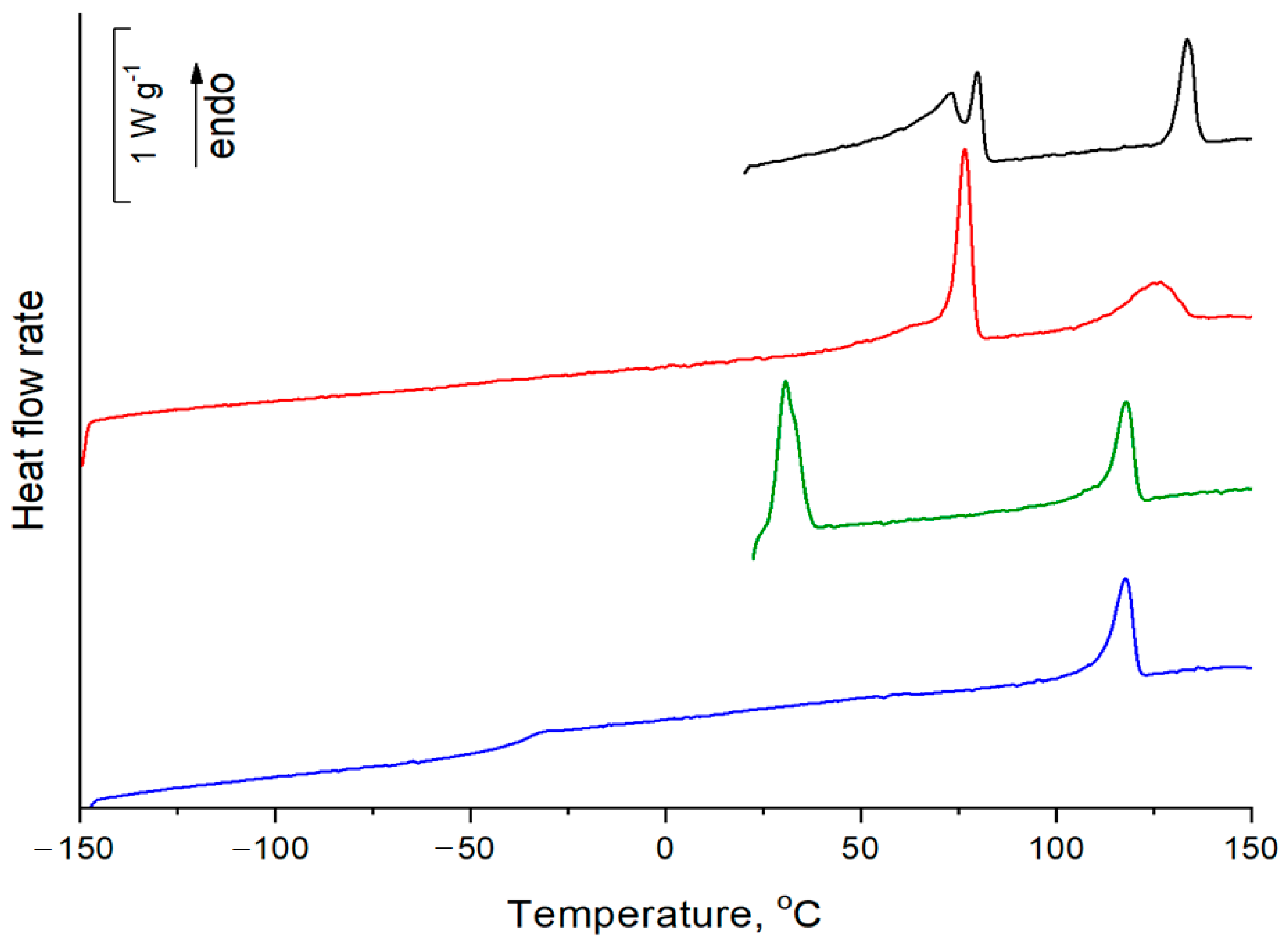

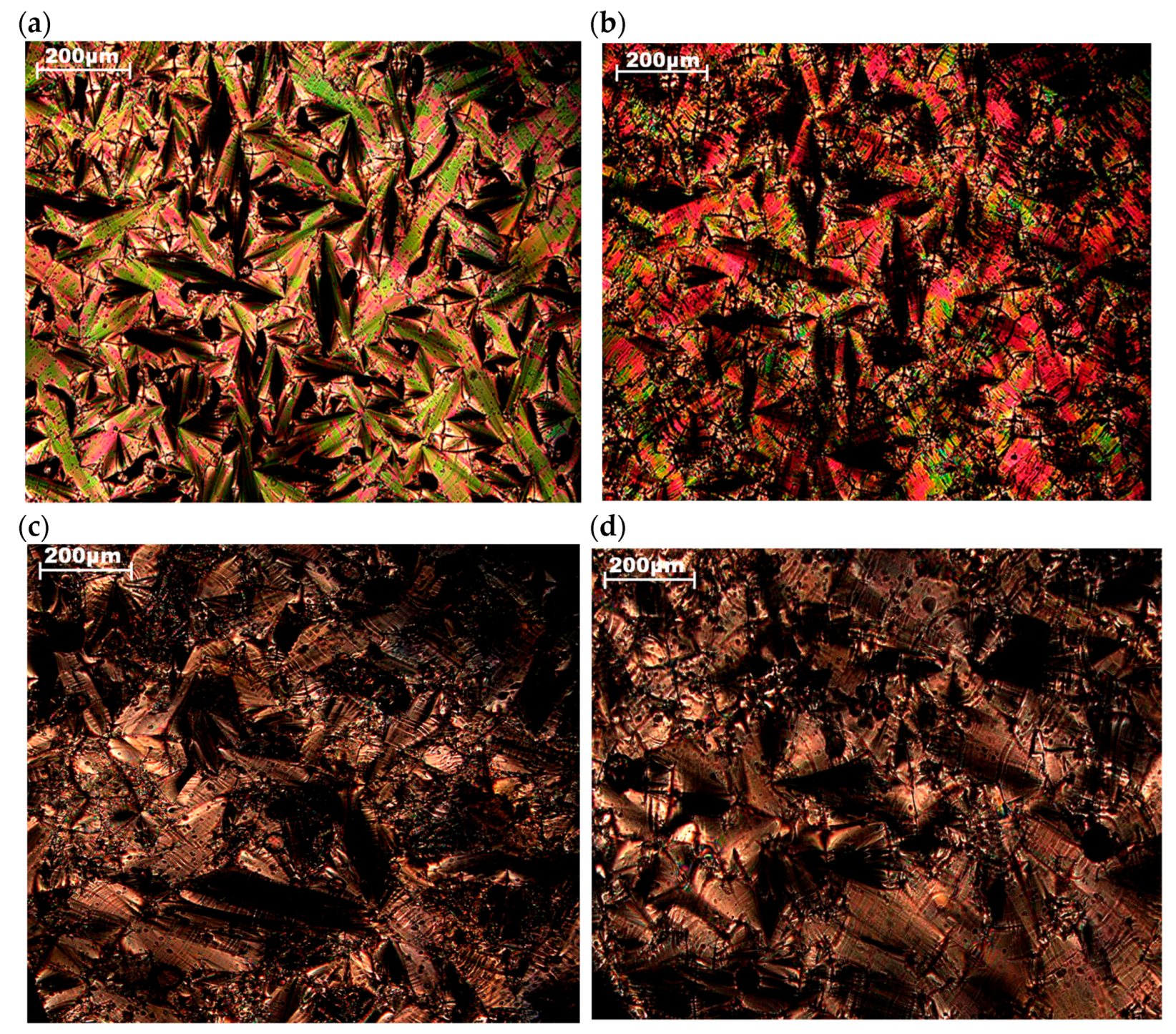

2.2. Thermal Properties and Phase Behavior

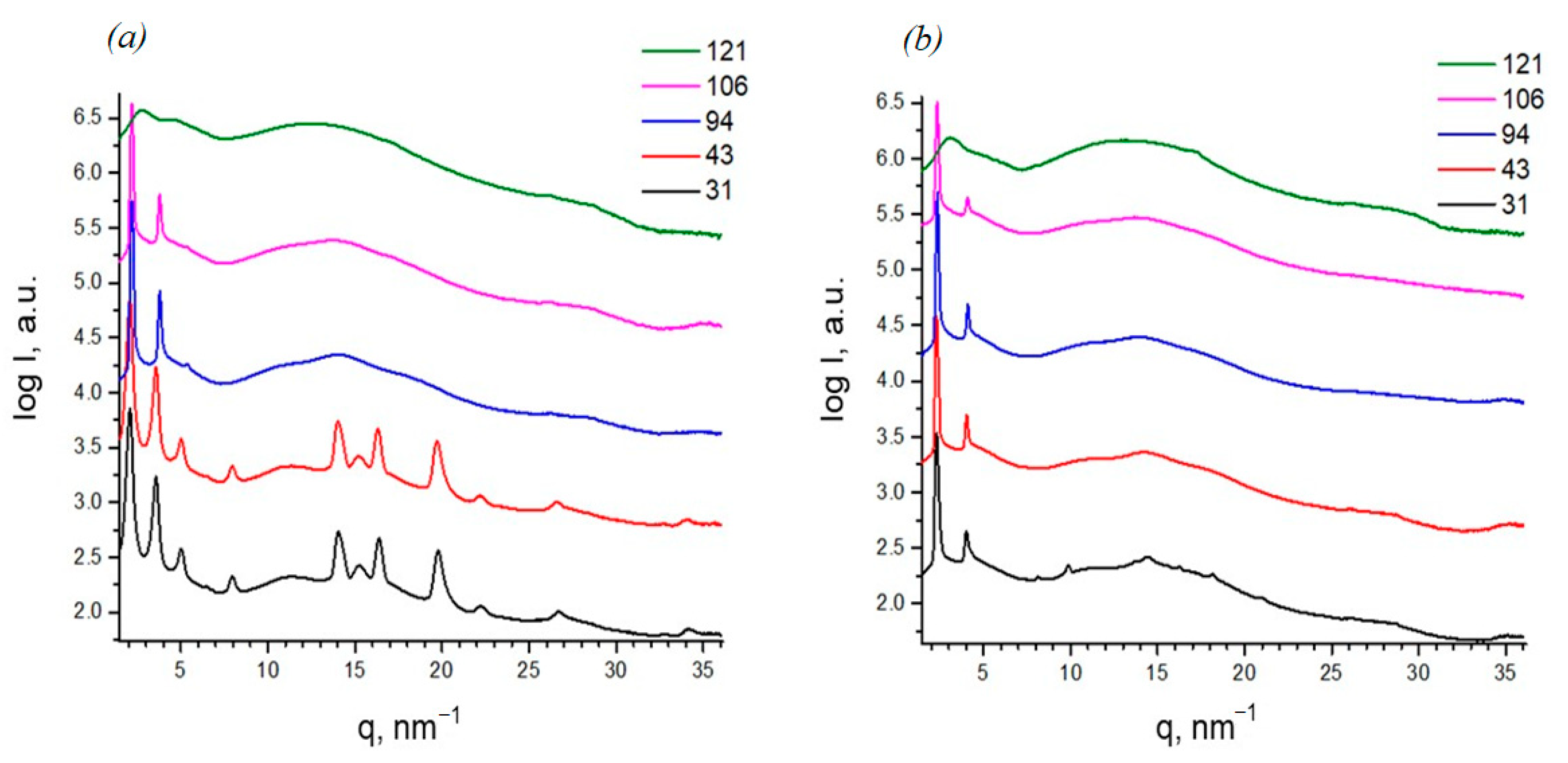

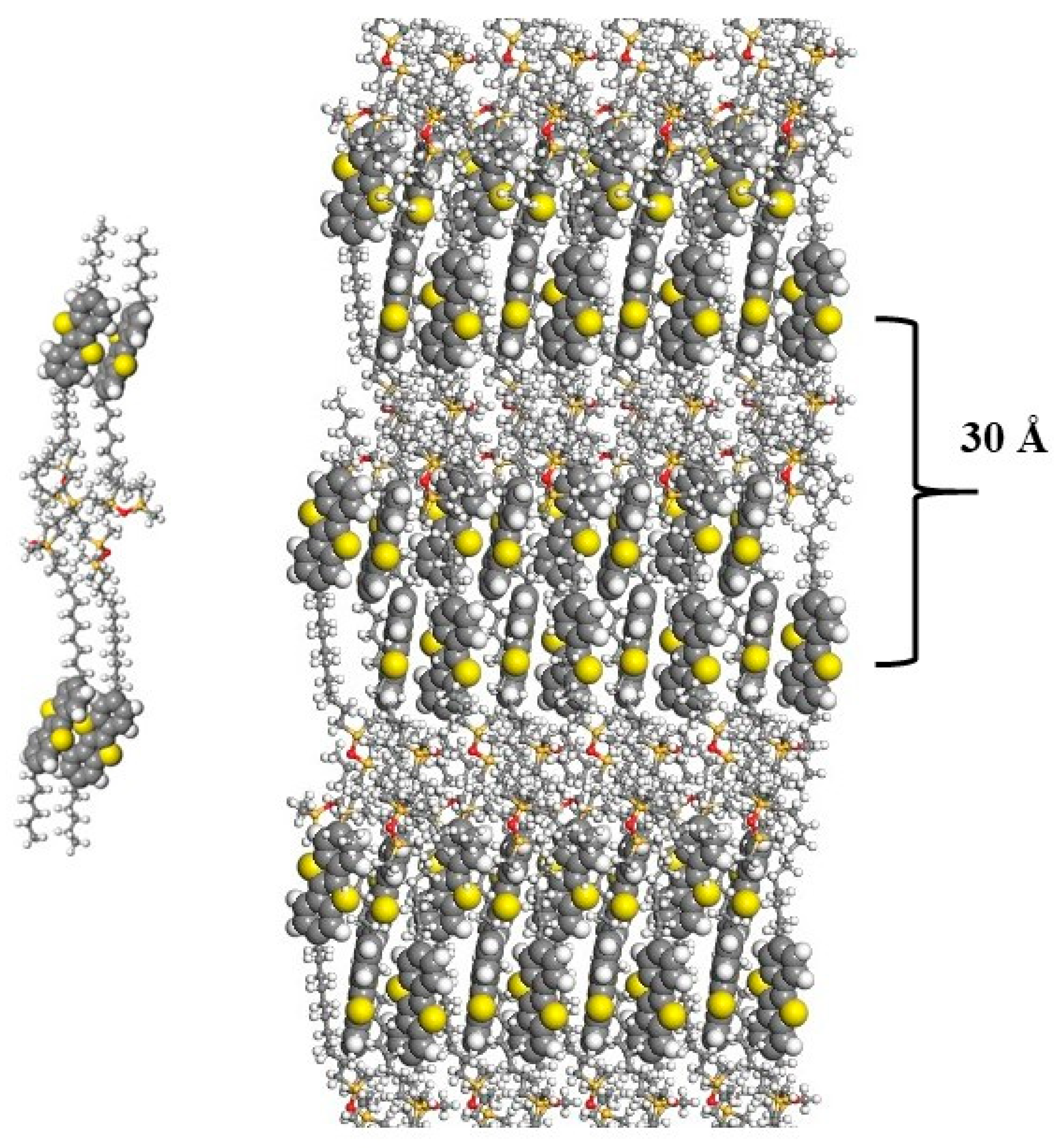

2.3. X-Ray Diffraction

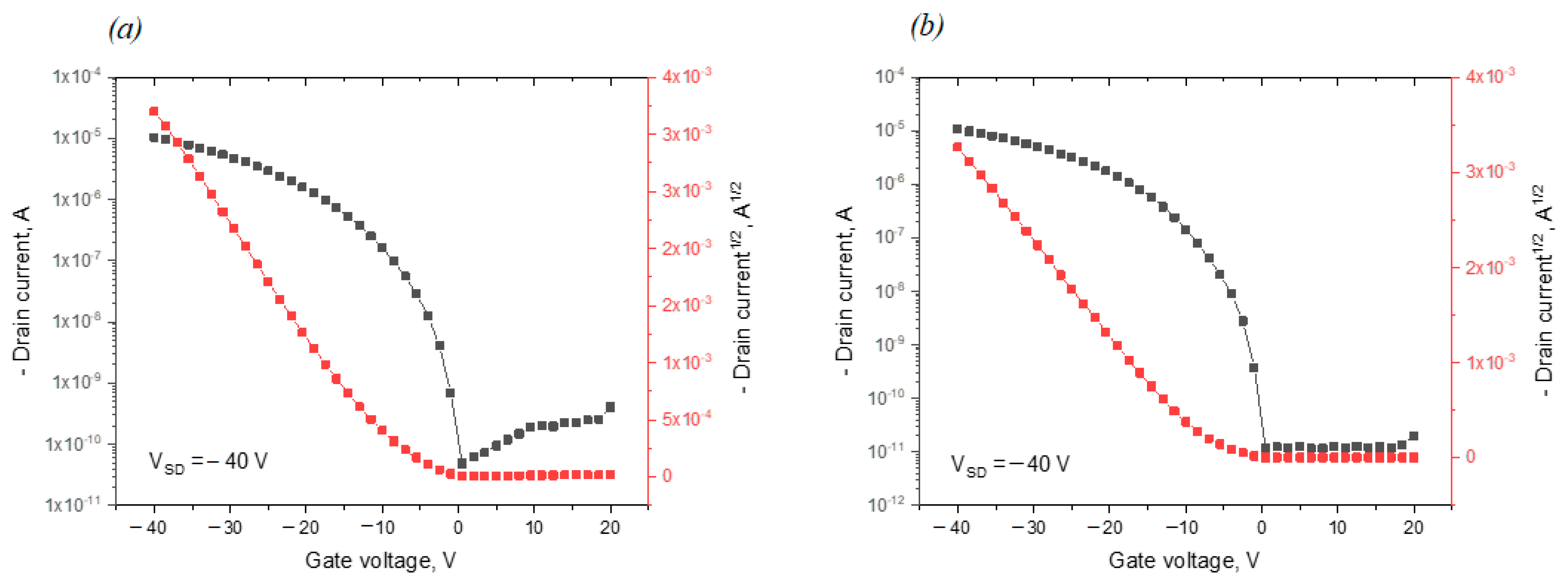

2.4. Electrical Characteristics

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

3.2. NMR-Spectroscopy

3.3. Thermal Analysis

3.4. X-Ray Diffraction Analysis

3.5. Chromatographic Methods

3.6. Mass-Spectrometry MALDI

3.7. Laboratory Equipment for Synthesis

3.8. Synthesis Methods

3.9. OFET Architecture

3.10. Surface Preparation

3.11. Application Method

3.12. Film Characterization

3.13. Electrical Measurements

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BTBT | [1]Benzothieno[3,2-b]benzothiophene |

| NMR | Nuclear magnetic resonance |

| OFETs | Organic field-effect transistors |

| OSC | Organic semiconductor |

| OLET | Organic light-emitting transistor |

| OECT | Organic electrochemical transistor |

| OLED | Organic light-emitting diode |

| OPVs | Organic photovoltaics |

| TMDS | 1,1,3,3-Tetramethyldisiloxane |

| GPC | Gel permeation chromatography |

| TLC | Thin-layer chromatography |

| TGA | Thermogravimetric analysis |

| POM | Polarization optical microscopy |

| DSC | Differential scanning calorimetry |

| XRD | X-ray diffraction analysis |

| AFM | Atomic-force microscope |

References

- Kang, S.-H.; Lee, S.M.; Lee, K.C.; Yang, C. Viable Regiochemical Control in Semiconducting Polymers for Field-Effect Transistors: From High-Mobility Enhancement toward High Deformability. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 17, 44030–44052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friederich, P.; Fediai, A.; Kaiser, S.; Konrad, M.; Jung, N.; Wenzel, W. Toward Design of Novel Materials for Organic Electronics. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, 1808256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Umoren, S.A.; Solomon, M.M. Protective polymeric films for industrial substrates: A critical review on past and recent applications with conducting polymers and polymer composites/nanocomposites. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2019, 104, 380–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abroshan, H.; Kwak, H.S.; An, Y.; Brown, C.; Chandrasekaran, A.; Winget, P.; Halls, M.D. Active Learning Accelerates Design and Optimization of Hole-Transporting Materials for Organic Electronics. Front. Chem. 2022, 17, 800371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desu, M.; Sharma, S.; Cheng, K.-H.; Wang, Y.-H.; Nagamatsu, S.; Chen, J.-C.; Pandey, S.S. Controlling the molecular orientation of a novel diketopyrrolopyrrole-based organic conjugated polymer for enhancing the performance of organic field-effect transistors. Org. Electron. 2023, 113, 106691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Liu, C.; Huang, J. Organic Field-Effect Transistor-Based Sensors: Recent Progress, Challenges and Future Outlook. J. Mater. Chem. C 2025, 13, 8354–8424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Z.; Gao, C.; Li, H.; Dong, H.; Hu, W. Organic Light-Emitting Transistors Entering a New Development Stage. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, 2007149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsufyani, M.; Rashid, R.B.; Giovannitti, A.; Inal, S.; Nielsen, C.B. The Effect of Organic Semiconductor Electron Affinity on Preventing Parasitic Oxidation Reactions Limiting Performance of N-Type Organic Electrochemical Transistors. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 2403265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullen, K.; Scherf, U. Conjugated Polymers: Where We Come From, Where We Stand, and Where We Might Go. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2023, 224, 2200337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarrabi, N.; Sandberg, O.J.; Meredith, P.; Armin, A. Subgap Absorption in Organic Semiconductors. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2023, 14, 3174–3185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, M.Y.; Zysman-Colman, E. Purely Organic Thermally Activated Delayed Fluorescence Materials for Organic Light-Emitting Diodes. Adv. Mater. 2017, 29, 1605444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Zhang, H.; Feng, K.; Guo, X. Polymer Acceptors for High-Performance All-Polymer Solar Cells. Chem. Eur. J. 2022, 28, e202200222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, J.; Diao, Y.; Appleton, A.L.; Fang, L.; Bao, Z. Integrated Materials Design of Organic Semiconductors for Field-Effect Transistors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 6724–6746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, S.; Huang, J. OFET chemical sensors: Chemical sensors based on ultrathin organic field-effect transistors. Polym. Int. 2021, 70, 414–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, P.; He, X.; Jiang, H. Greater than 10 cm2V−1s−1: A breakthrough of organic semiconductors for field-effect transistors. InfoMat 2021, 3, 613–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Hasan, M.M.; Tang, Y.; Khan, A.R.; Yan, H.T.; Sun, Y.X.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, Y. 2D organic single crystals: Synthesis, novel physics, high-performance optoelectronic devices and integration. Mater. Today 2021, 50, 422–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Duan, S.; Zhang, X.; Hu, W. Patterning organic semiconductor crystals for optoelectronics. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2021, 119, 040501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Yu, G. Multicomponent Blend Systems Used in Organic Field-Effect Transistors: Charge Transport Properties, Large-Area Preparation, and Functional Devices. Chem. Mater. 2021, 33, 2229–2257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kousseff, C.J.; Halaksa, R.; Parr, Z.S.; Nielsen, C.B. Mixed Ionic and Electronic Conduction in Small-Molecule Semiconductors. Chem. Rev. 2021, 122, 4397–4419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Yun, C.; Yun, S.; Ho, D.; Earmme, T.; Kim, C.; Seo, S.Y. Modification of alkyl side chain on thiophene-containing benzothieno[3,2-b]benzothiophene-based organic semiconductors for organic field-effect transistors. Synth. Met. 2022, 291, 117173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Zhou, L. Comprehensive Study on the Mobility Anisotropy of Benzothieno[3,2-b][1]benzothiophenes: Toward Isotropic Charge-Transport Properties. J. Phys. Chem. C 2023, 127, 13327–13337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, T.; Nishimura, T.; Yamamoto, T.; Doi, I.; Miyazaki, E.; Osaka, I.; Takimiya, K. Consecutive Thiophene-Annulation Approach to π-Extended Thienoacene-Based Organic Semiconductors with [1]Benzothieno[3,2-b][1]benzothiophene (BTBT) Substructure. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 13900–13913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wawrzinek, R.; Sobus, J.; Chaudhry, M.U.; Ahmad, V.; Grosjean, A.; Clegg, J.K.; Namdas, E.B.; Lo, S.-C. Mobility Evaluation of [1]Benzothieno[3,2-b][1]benzothiophene Derivatives: Limitation and Impact on Charge Transport. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 3271–3279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monobe, H.; An, L.; Hu, P.; Wang, B.-Q.; Zhao, K.-Q.; Shimizu, Y. Charge transport property of asymmetric Alkyl-BTBT LC semiconductor possessing a fluorophenyl group. Mol. Cryst. Liq. Cryst. 2017, 647, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borshchev, O.V.; Sizov, A.S.; Agina, E.V.; Bessonov, A.A.; Ponomarenko, S.A. Synthesis of organosilicon derivatives of [1]benzothieno[3,2-b][1]-benzothiophene for efficient monolayer Langmuir–Blodgett organic field effect transistors. Chem. Commun. 2017, 53, 885–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trul, A.A.; Sizov, A.S.; Chekusova, V.P.; Borshchev, O.V.; Agina, E.V.; Shcherbina, M.A.; Bakirov, A.V.; Chvalun, S.N.; Ponomarenko, S.A. Organosilicon dimer of BTBT as a perspective semiconductor material for toxic gas detection with monolayer organic field-effect transistors. J. Mater. Chem. C. 2018, 6, 9649–9659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polinskaya, M.S.; Trul, A.A.; Borshchev, O.V.; Skorotetcky, M.S.; Gaidarzhi, V.P.; Toirov, S.K.; Anisimov, D.S.; Bakirov, A.V.; Chvalun, S.N.; Agina, E.V.; et al. The influence of terminal alkyl groups on the structure, and electrical and sensing properties of thin films of self-assembling organosilicon derivatives of benzothieno[3,2-b][1]benzothiophene. J. Mater. Chem. C 2023, 11, 1937–1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trul, A.A.; Chekusova, V.P.; Anisimov, D.S.; Borshchev, O.V.; Polinskaya, M.S.; Agina, E.V.; Ponomarenko, S.A. Operationally Stable Ultrathin Organic Field Effect Transistors Based on Siloxane Dimers of Benzothieno[3,2-b][1]Benzothiophene Suitable for Ethanethiol Detection. Adv. Electron. Mater. 2022, 8, 2101039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponomarenko, S.A.; Tatarinova, E.A.; Muzafarov, A.M.; Kirchmeyer, S.; Brassat, L.; Mourran, A.; Moeller, M.; Setayesh, S.; Leeuw, D. Star-Shaped Oligothiophenes for Solution-Processible Organic Electronics: Flexible Aliphatic Spacers Approach. Chem. Mater. 2006, 18, 4101–4108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polinskaya, M.S.; Luponosov, Y.N.; Borshchev, O.V.; Gülcher, J.; Ziener, U.; Mourran, A.; Wang, J.; Buzin, M.I.; Muzafarov, A.M.; Ponomarenko, S.A. Synthesis and Aggregation Behavior of Novel Linear and Branched Oligothiophene-Containing Organosilicon Multipods. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2022, 2022, e202101495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudkova, I.O.; Sorokina, E.A.; Zaborin, E.A.; Polinskaya, M.S.; Borshchev, O.V.; Ponomarenko, S.A. Peculiar Features of the Reduction of Keto Group in the Synthesis of Mono- and Dialkyl-Substituted Benzo[b]benzo[4,5]thieno[2,3-d]thiophene. Russ. J. Org. Chem. 2024, 60, 1074–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrallo-Aniceto, M.C.; Pintado-Sierra, M.; Valverde-González, A.; Díaz, U.; Sánchez, F.; Maya, E.M.; Iglesias, M. Unveiling the potential of a covalent triazine framework based on [1]benzothieno[3,2-b][1]benzothiophene (DPhBTBT-CTF) as a metal-free heterogeneous photocatalyst. Green Chem. 2024, 26, 1975–1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisoyi, H.K.; Li, Q. Liquid Crystals: Versatile Self-Organized Smart Soft Materials. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 48874926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cholakova, D.; Denkov, N. Rotator phases in alkane systems: In bulk, surface layers and micro/nano-confinements. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2019, 269, 7–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaborin, E.A.; Borshchev, O.V.; Skorotetskii, M.S.; Gorodov, V.V.; Bakirov, A.V.; Polinskaya, M.S.; Chvalun, S.N.; Ponomarenko, S.A. Synthesis and Thermal and Phase Behavior of Polysiloxanes with Grafted Dialkyl-Substituted [1]Benzothieno[3,2-b][1]benzothiophene Groups. Polym. Sci. Ser. B 2022, 64, 841–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaposhnik, P.A.; Trul, A.A.; Poimanova, E.Y.; Sorokina, E.A.; Borschev, O.V.; Agina, E.V.; Ponomarenko, S.A. BTBT-based organic semiconducting materials for EGOFETs with prolonged shelf-life stability. Org. Electron. 2024, 129, 107047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.; Cho, K.; Frisbie, C.; Sirringhaus, H.; Podzorov, V. Critical assessment of charge mobility extraction in FETs. Nat. Mater. 2018, 17, 2–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, M.; Osaka, I.; Miyazaki, E.; Takimiya, K.; Kuwabara, H.; Ikeda, M. One-step synthesis of [1]benzothieno[3,2-b][1]benzothiophene from o-chlorobenzaldehyde. Tetrahedron Lett. 2011, 52, 285–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levkov, L.L.; Surin, N.M.; Borshchev, O.V.; Titova, Y.O.; Dubinets, N.O.; Svidchenko, E.A.; Shaposhnik, P.A.; Trul, A.A.; Umarov, A.Z.; Anokhin, D.V.; et al. Three Isomeric Dioctyl Derivatives of 2,7-Dithienyl[1]benzo-thieno[3,2-b][1]benzothiophene: Synthesis, Optical, Thermal, and Semiconductor Properties. Materials 2025, 18, 743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalb, W.L.; Batlogg, B. Calculating the trap density of states in organic field-effect transistors from experiment: A comparison of different methods. Phys. Rev. B 2010, 81, 035327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Organic Semiconductor | C, g L−1 | μeff.max (µeff.ave), cm2 V−1 s−1 | Vth, V | Ion/off | Number of Devices | Thickness (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D4-Und-BTBT-Hex | 1.0 | 1.6 × 10−3 (5.2 × 10−4 ± 3.2 × 10−4) | −5.3 to 4.9 | 105−107 | 19 * | 7–16 |

| 2.0 | 1.8 × 10−3 (8.0 × 10−4 ± 4.4 × 10−4) | −5.8 to 13.1 | 104−107 | 19 * | 5–14 | |

| 1.0 | 3.3 × 10−2 (2.0 × 10−2 ± 1.0 × 10−2) | −20.1 to −4.0 | 103–105 | 14 ** | 6–10 | |

| 2.0 | 3.5 × 10−2 (2.1 × 10−2 ± 6.7 × 10−3) | −17.1 to −7.0 | 103–105 | 18 ** | 6–24 | |

| D4-Hex-BTBT-Oct | 1.0 | 3.8 × 10−6 (2.6 × 10−6 ± 8.8 × 10−7) | −11.0 to +14.0 | 100−101 | 5 ** | 6–9 |

| 2.0 | 4.5 × 10−6 (3.4 × 10−6 ± 7.1 × 10−7) | −11.0 to +2.0 | 100−101 | 19 ** | 9–10 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gudkova, I.O.; Zaborin, E.A.; Buzin, A.I.; Bakirov, A.V.; Titova, Y.O.; Borshchev, O.V.; Chvalun, S.N.; Ponomarenko, S.A. Novel Organosilicon Tetramers with Dialkyl-Substituted [1]Benzothieno[3,2-b]benzothiophene Moieties for Solution-Processible Organic Electronics. Molecules 2025, 30, 4639. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234639

Gudkova IO, Zaborin EA, Buzin AI, Bakirov AV, Titova YO, Borshchev OV, Chvalun SN, Ponomarenko SA. Novel Organosilicon Tetramers with Dialkyl-Substituted [1]Benzothieno[3,2-b]benzothiophene Moieties for Solution-Processible Organic Electronics. Molecules. 2025; 30(23):4639. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234639

Chicago/Turabian StyleGudkova, Irina O., Evgeniy A. Zaborin, Alexander I. Buzin, Artem V. Bakirov, Yaroslava O. Titova, Oleg V. Borshchev, Sergey N. Chvalun, and Sergey A. Ponomarenko. 2025. "Novel Organosilicon Tetramers with Dialkyl-Substituted [1]Benzothieno[3,2-b]benzothiophene Moieties for Solution-Processible Organic Electronics" Molecules 30, no. 23: 4639. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234639

APA StyleGudkova, I. O., Zaborin, E. A., Buzin, A. I., Bakirov, A. V., Titova, Y. O., Borshchev, O. V., Chvalun, S. N., & Ponomarenko, S. A. (2025). Novel Organosilicon Tetramers with Dialkyl-Substituted [1]Benzothieno[3,2-b]benzothiophene Moieties for Solution-Processible Organic Electronics. Molecules, 30(23), 4639. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234639