Gemini Surfactants: Advances in Applications and Prospects for the Future

Abstract

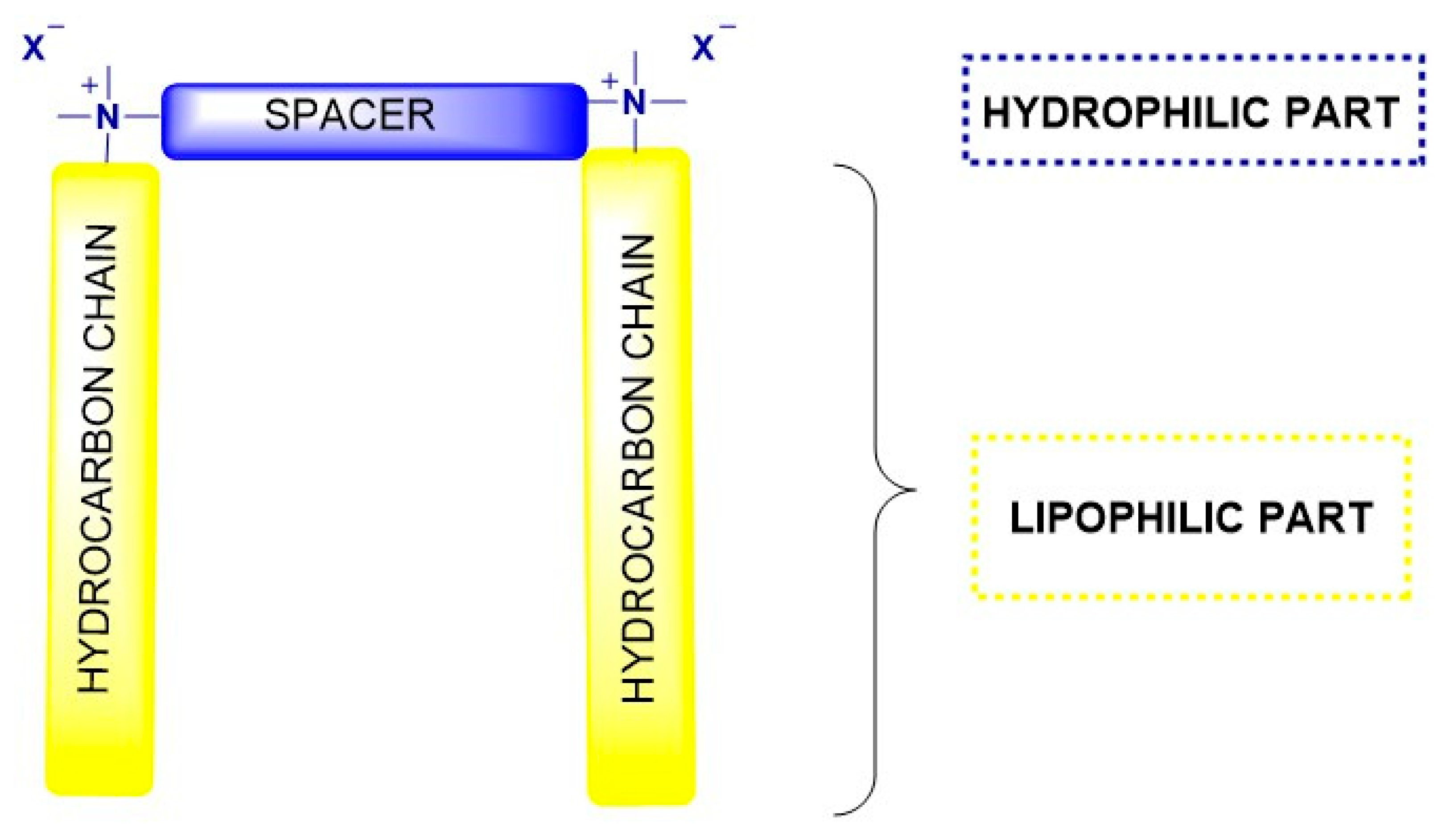

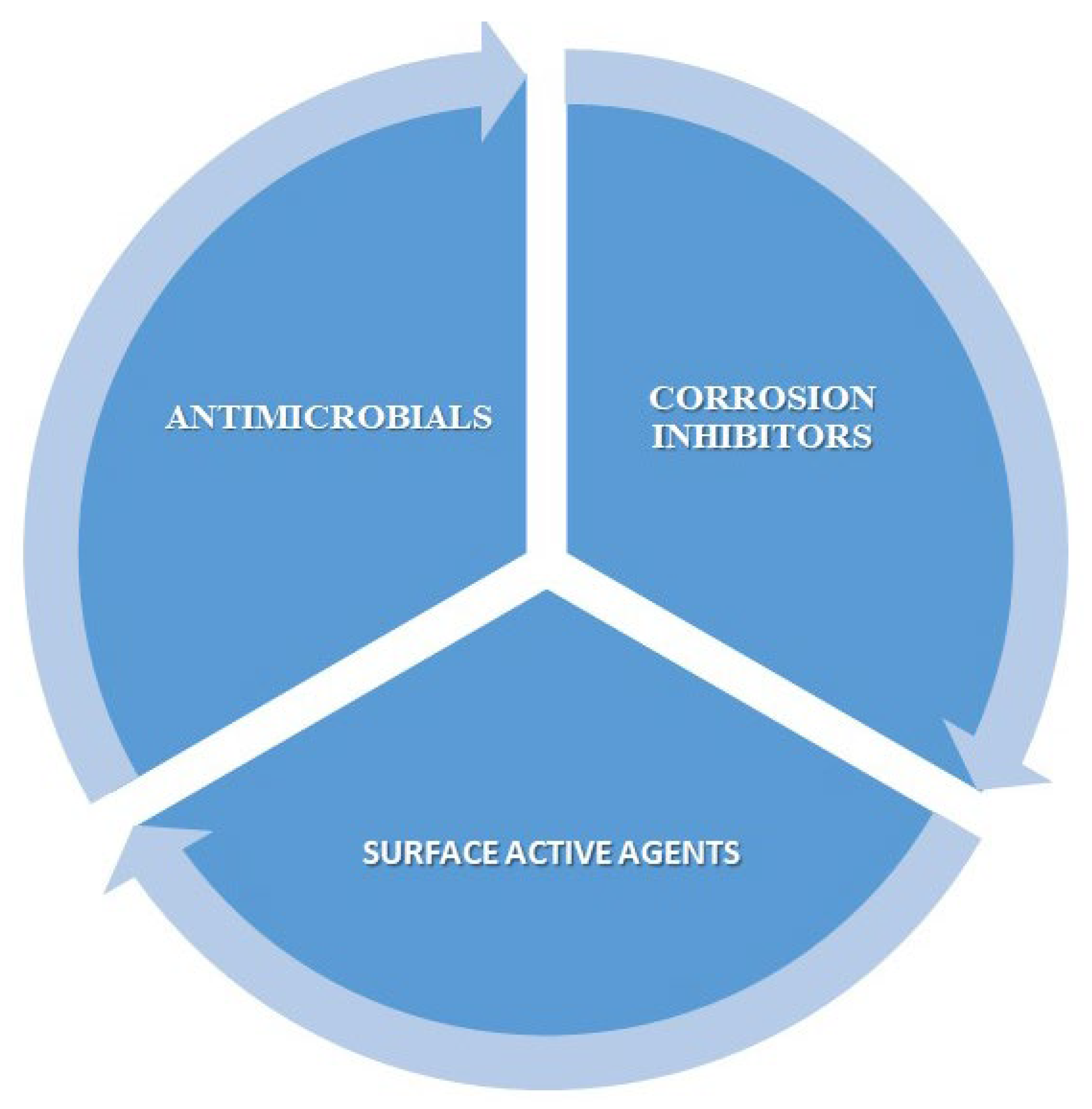

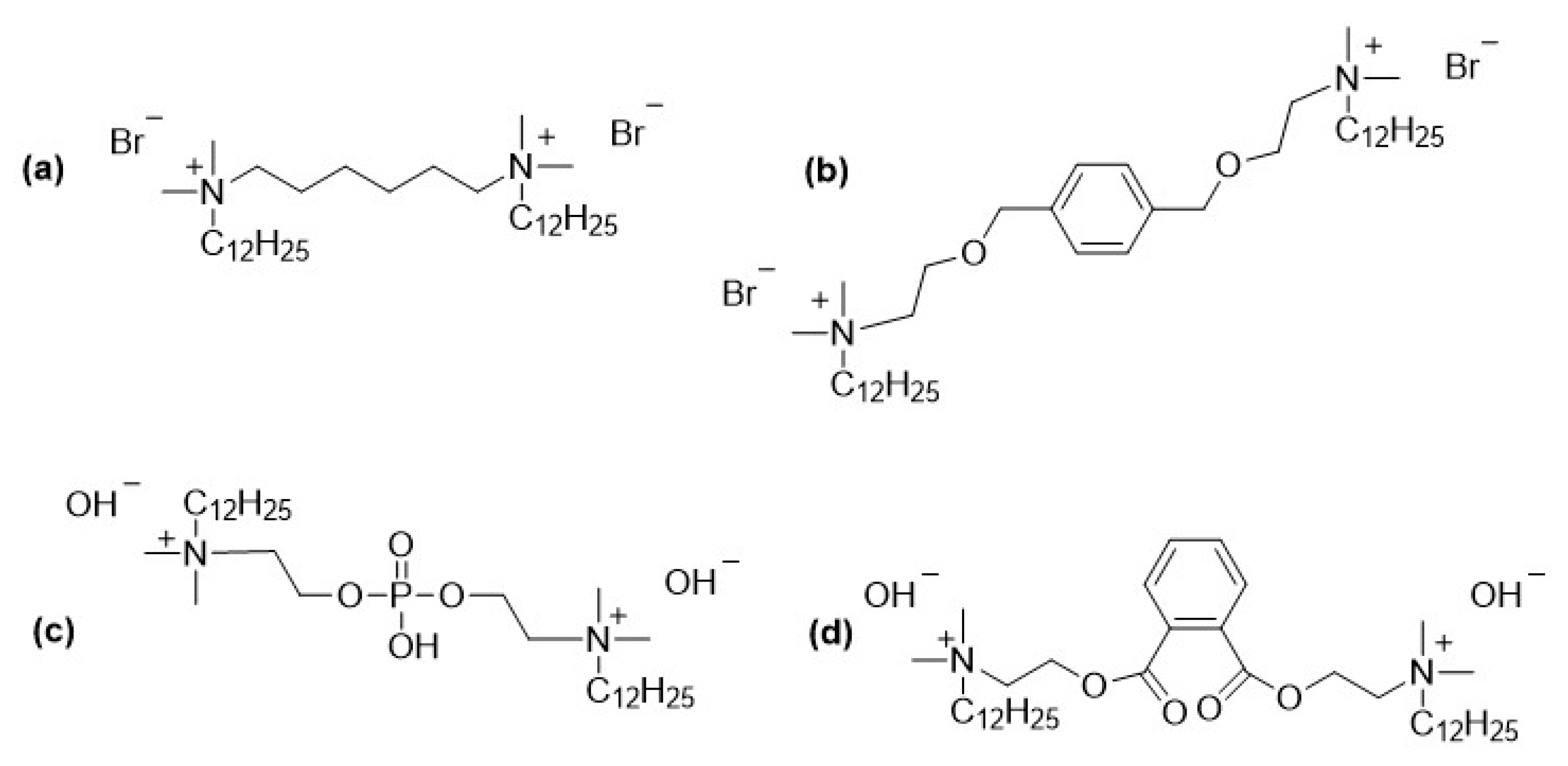

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Eradication of Biofilm by Gemini Surfactants

2.2. Gemini Surfactants as Biocorrosion Inhibitors

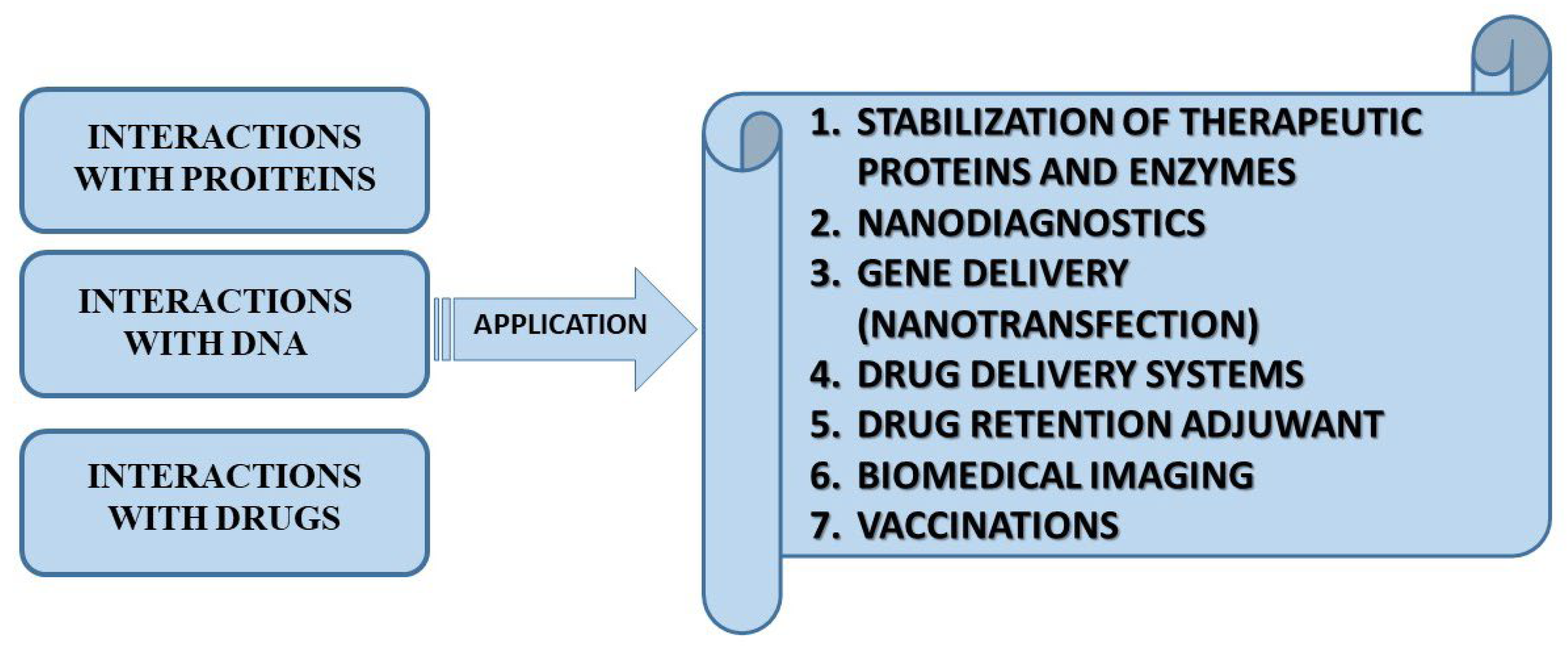

2.3. Biomedical Applications of Gemini Surfactants

2.4. Gemini Surfactants in Nanotechnology

- Improved stability: Increased resistance to moisture, light, and other degrading factors.

- Morphology control: Precise control over nanoparticle size and shape.

- Enhanced optical performance: Higher fluorescence efficiency and reduced energy losses.

- Better dispersion: Facilitates fabrication of thin films and integration with other materials.

2.5. Gemini Surfactants in Oil Recovery and Transportation

3. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nagtode, V.S.; Cardoza, C.; Yasin, H.K.A.; Mali, S.N.; Tambe, S.M.; Roy, P.; Singh, K.; Goel, A.; Amin, P.D.; Thorat, B.R.; et al. Green Surfactants (Biosurfactants): A Petroleum-Free Substitute for Sustainability─Comparison, Applications, Market, and Future Prospects. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 11674–11699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aisha; Batool, I.; Iftekhar, S.; Taj, M.B.; Carabineiro, S.A.C.; Ahmad, F.; Khan, M.I.; Shanableh, A.; Alshater, H. Wetting the Surface: A Deep Dive into Chemistry and Applications of Surfactants. Clean. Chem. Eng. 2025, 11, 100197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhadani, A.; Kafle, A.; Ogura, T.; Akamatsu, M.; Sakai, K.; Sakai, H.; Abe, M. Current Perspective of Sustainable Surfactants Based on Renewable Building Blocks. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 2020, 45, 124–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Ray, A.; Pramanik, N. Self-Assembly of Surfactants: An Overview on General Aspects of Amphiphiles. Biophys. Chem. 2020, 265, 106429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babajanzadeh, B.; Sherizadeh, S.; Hasan, R. Detergents and Surfactants: A Brief Review. Open Access J. Sci. 2019, 3, 94–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, D.; Rufino, R.; Luna, J.; Santos, V.; Sarubbo, L. Biosurfactants: Multifunctional Biomolecules of the 21st Century. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romero Vega, G.; Gallo Stampino, P. Bio-Based Surfactants and Biosurfactants: An Overview and Main Characteristics. Molecules 2025, 30, 863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdoli, S.; Asgari Lajayer, B.; Bagheri Novair, S.; Price, G.W. Unlocking the Potential of Biosurfactants in Agriculture: Novel Applications and Future Directions. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimoh, A.A.; Booysen, E.; Van Zyl, L.; Trindade, M. Do Biosurfactants as Anti-Biofilm Agents Have a Future in Industrial Water Systems? Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 11, 1244595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.-Y.; Mahmoud, Z.H.; Hussein, U.A.-R.; Abduvalieva, D.; Alsultany, F.H.; Kianfar, E. Biosurfactants: Properties, Applications and Emerging Trends. S. Afr. J. Chem. Eng. 2025, 53, 21–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

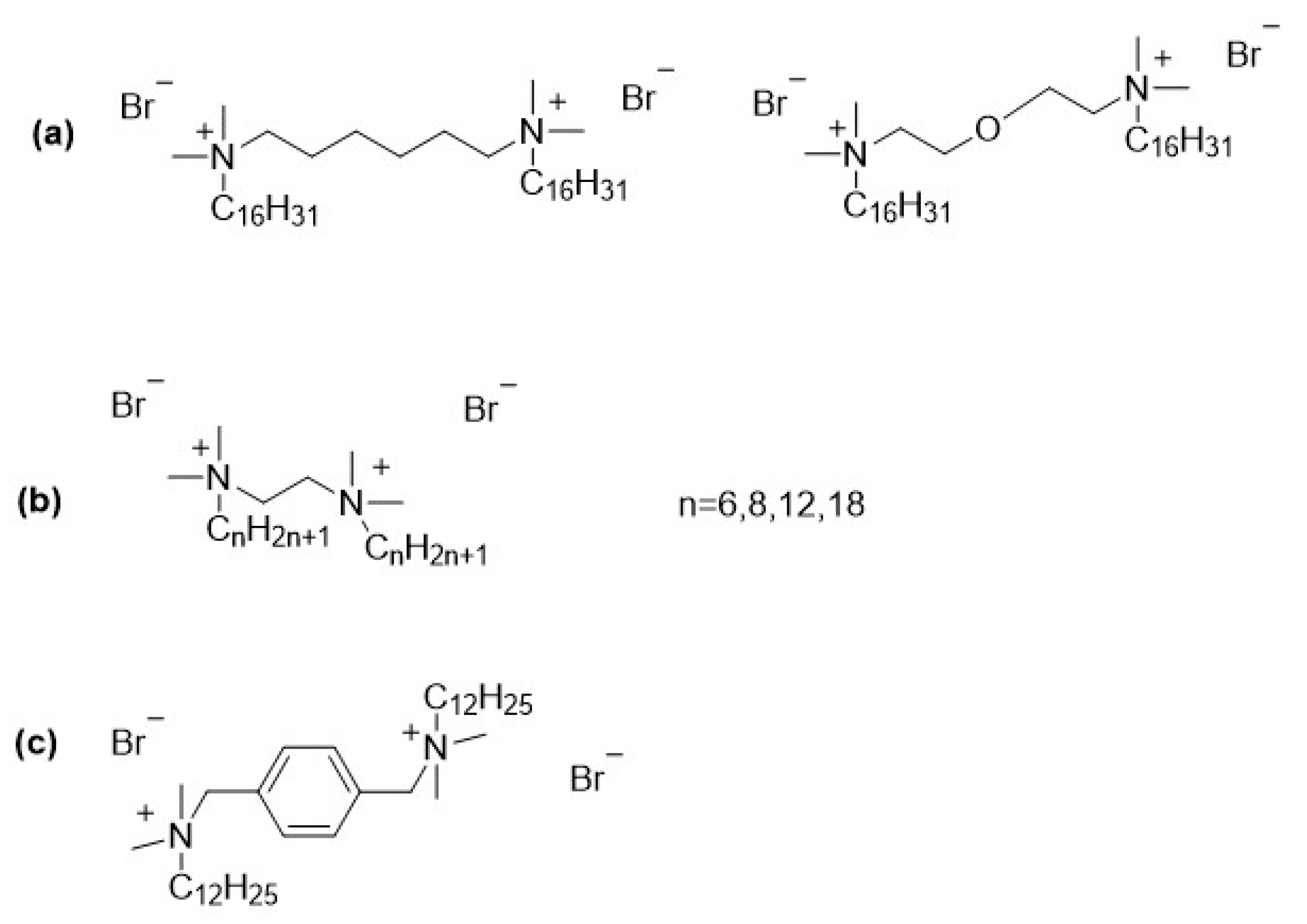

- Brycki, B.E.; Kowalczyk, I.H.; Szulc, A.; Kaczerewska, O.; Pakiet, M. Multifunctional Gemini Surfactants: Structure, Synthesis, Properties and Applications. In Application and Characterization of Surfactants; Najjar, R., Ed.; InTech: London, UK, 2017; ISBN 978-953-51-3325-4. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, R.; Kamal, A.; Abdinejad, M.; Mahajan, R.K.; Kraatz, H.-B. Advances in the Synthesis, Molecular Architectures and Potential Applications of Gemini Surfactants. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2017, 248, 35–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menger, F.M.; Keiper, J.S.; Azov, V. Gemini Surfactants with Acetylenic Spacers. Langmuir 2000, 16, 2062–2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menger, F.M.; Littau, C.A. Gemini-Surfactants: Synthesis and Properties. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991, 113, 1451–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmady, A.R.; Hosseinzadeh, P.; Solouk, A.; Akbari, S.; Szulc, A.M.; Brycki, B.E. Cationic Gemini Surfactant Properties, Its Potential as a Promising Bioapplication Candidate, and Strategies for Improving Its Biocompatibility: A Review. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2022, 299, 102581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brycki, B.; Waligórska, M.; Szulc, A. The Biodegradation of Monomeric and Dimeric Alkylammonium Surfactants. J. Hazard. Mater. 2014, 280, 797–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Ding, S.; Yu, J.; Chen, X.; Lei, Q.; Fang, W. Antibacterial Activity, in Vitro Cytotoxicity, and Cell Cycle Arrest of Gemini Quaternary Ammonium Surfactants. Langmuir 2015, 31, 12161–12169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamal, M.S. A Review of Gemini Surfactants: Potential Application in Enhanced Oil Recovery. J. Surfactants Deterg. 2016, 19, 223–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brycki, B.; Szulc, A. Gemini Surfactants as Corrosion Inhibitors. A Review. J. Mol. Liq. 2021, 344, 117686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damyanova, T.; Paunova-Krasteva, T. What We Still Don’t Know About Biofilms—Current Overview and Key Research Information. Microbiol. Res. 2025, 16, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flemming, H.-C.; Wingender, J. The Biofilm Matrix. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2010, 8, 623–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omwenga, E.O.; Awuor, S.O. The Bacterial Biofilms: Formation, Impacts, and Possible Management Targets in the Healthcare System. Can. J. Infect. Dis. Med. Microbiol. 2024, 2024, 1542576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, A.; Sun, J.; Liu, Y. Understanding Bacterial Biofilms: From Definition to Treatment Strategies. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1137947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paluch, E.; Szperlik, J.; Lamch, Ł.; Wilk, K.A.; Obłąk, E. Biofilm Eradication and Antifungal Mechanism of Action against Candida Albicans of Cationic Dicephalic Surfactants with a Labile Linker. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 8896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, D.; Saharan, B.S. Functional Characterization of Biomedical Potential of Biosurfactant Produced by Lactobacillus Helveticus. Biotechnol. Rep. 2016, 11, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koziróg, A.; Kręgiel, D.; Brycki, B. Action of Monomeric/Gemini Surfactants on Free Cells and Biofilm of Asaia Lannensis. Molecules 2017, 22, 2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koziróg, A.; Otlewska, A.; Brycki, B. Viability, Enzymatic and Protein Profiles of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Biofilm and Planktonic Cells after Monomeric/Gemini Surfactant Treatment. Molecules 2018, 23, 1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazurkiewicz, E.; Lamch, Ł.; Wilk, K.A.; Obłąk, E. Anti-Adhesive, Anti-Biofilm and Fungicidal Action of Newly Synthesized Gemini Quaternary Ammonium Salts. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 14110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, L.-H.; Kwaśniewska, D.; Wang, S.-C.; Shen, T.-L.; Wieczorek, D.; Chen, Y.-L. Gemini Quaternary Ammonium Compound PMT12-BF4 Inhibits Candida Albicans via Regulating Iron Homeostasis. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 2911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafidi, Z.; García, M.T.; Vazquez, S.; Martinavarro-Mateos, M.; Ramos, A.; Pérez, L. Antimicrobial and Biofilm-Eradicating Properties of Simple Double-Chain Arginine-Based Surfactants. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2025, 253, 114762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labena, A.; Hegazy, M.A.; Sami, R.M.; Hozzein, W.N. Multiple Applications of a Novel Cationic Gemini Surfactant: Anti-Microbial, Anti-Biofilm, Biocide, Salinity Corrosion Inhibitor, and Biofilm Dispersion (Part II). Molecules 2020, 25, 1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, L.; Da Silva, C.R.; Do Amaral Valente Sá, L.G.; Neto, J.B.D.A.; Cabral, V.P.D.F.; Rodrigues, D.S.; Moreira, L.E.A.; Silveira, M.J.C.B.; Ferreira, T.L.; Da Silva, A.R.; et al. Preventive Activity of an Arginine-Based Surfactant on the Formation of Mixed Biofilms of Fluconazole-Resistant Candida Albicans and Extended-Spectrum-Beta-Lactamase-Producing Escherichia Coli on Central Venous Catheters. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mechken, K.A.; Menouar, M.; Talbi, Z.; Saidi-Besbes, S.; Belkhodja, M. Self-Assembly and Antimicrobial Activity of Cationic Gemini Surfactants Containing Triazole Moieties. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 19185–19196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barabanova, A.I.; Karamov, E.V.; Larichev, V.F.; Kornilaeva, G.V.; Fedyakina, I.T.; Turgiev, A.S.; Naumkin, A.V.; Lokshin, B.V.; Shibaev, A.V.; Potemkin, I.I.; et al. Virucidal Coatings Active Against SARS-CoV-2. Molecules 2024, 29, 4961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodsiani, M.; Kianmehr, Z.; Brycki, B.; Szulc, A.; Mehrbod, P. Evaluation of the Antiviral Potential of Gemini Surfactants against Influenza Virus H1N1. Arch. Microbiol. 2023, 205, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santhosh Kumar, A.; Sivakumar, L.; Rajadesingu, S.; Sathish, S.; Malik, T.; Parthipan, P. Sustainable Corrosion Inhibition Approaches for the Mitigation of Microbiologically Influenced Corrosion—A Systematic Review. Front. Mater. 2025, 12, 1545245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knisz, J.; Eckert, R.; Gieg, L.M.; Koerdt, A.; Lee, J.S.; Silva, E.R.; Skovhus, T.L.; An Stepec, B.A.; Wade, S.A. Microbiologically Influenced Corrosion—More than Just Microorganisms. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2023, 47, fuad041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.I.; Ahmad, S.N. Microbiologically Influenced Corrosion in Uncoated and Coated Mild Steel. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 12629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arroussi, M.; Yang, K.; Shams, A.; Toor, I.U.H.; Wei, B. Advances in Microbial Corrosion of Metals Induced via Extracellular Electron Transfer by Shewanella oneidensis MR-1. npj Mater. Degrad. 2025, 9, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Zhang, R.; Wang, X.; Duan, J.; Etim, I.-I.N.; Mathivanan, K.; Wang, C. Harnessing Bacterial Power: Advanced Strategies and Genetic Engineering Insights for Biocorrosion Control and Inhibition. npj Mater. Degrad. 2025, 9, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Gong, L.; Chen, X.; Gadd, G.M.; Liu, D. Dual Role of Microorganisms in Metal Corrosion: A Review of Mechanisms of Corrosion Promotion and Inhibition. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1552103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tkachuk, N.; Zelena, L.; Novikov, Y. Indicators of the Microbial Corrosion of Steel Induced by Sulfate-Reducing Bacteria Under the Influence of Certain Drugs. Microbiol. Res. 2025, 16, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakiet, M.; Kowalczyk, I.; Leiva Garcia, R.; Moorcroft, R.; Nichol, T.; Smith, T.; Akid, R.; Brycki, B. Gemini Surfactant as Multifunctional Corrosion and Biocorrosion Inhibitors for Mild Steel. Bioelectrochemistry 2019, 128, 252–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, H.; Li, X.; Lu, X.; Wang, J.; Hu, Z.; Ma, X. Efficiency of Gemini Surfactant Containing Semi-Rigid Spacer as Microbial Corrosion Inhibitor for Carbon Steel in Simulated Seawater. Bioelectrochemistry 2021, 140, 107809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labena, A.; Hegazy, M.A.; Horn, H.; Müller, E. Cationic Gemini Surfactant as a Corrosion Inhibitor and a Biocide for High Salinity Sulfidogenic Bacteria Originating from an Oil-Field Water Tank. J. Surfactants Deterg. 2014, 17, 419–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labena, A.; Hegazy, M.A.; Horn, H.; Müller, E. The Biocidal Effect of a Novel Synthesized Gemini Surfactant on Environmental Sulfidogenic Bacteria: Planktonic Cells and Biofilms. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2015, 47, 367–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labena, A.; Hegazy, M.A.; Horn, H.; Müller, E. Sulfidogenic-Corrosion Inhibitory Effect of Cationic Monomeric and Gemini Surfactants: Planktonic and Sessile Diversity. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 42263–42278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, R.A.; Holmberg, K.; Lindman, B. Cationic Surfactants: A Review. J. Mol. Liq. 2023, 375, 121335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalan, F.A.; Kadhim, S.H. Synthesis, Characterization and In Vitro Anti-Cancer Properties of Cationic Gemini Surfactants with Alkyl Chains in Human Breast Cancer. J. Angiother. 2024, 8, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, T.; Kamel, A.O.; Wettig, S.D. Interactions between DNA and Gemini Surfactant: Impact on Gene Therapy: Part I. Nanomedicine 2016, 11, 289–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, P.; Chen, Y.; Xing, Y.; Wu, K.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, H. Recent Progress in Gene Delivery Systems Based on Gemini-Surfactant. MedComm—Future Med. 2025, 4, e70027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta-Martínez, D.R.; Rodríguez-Velázquez, E.; Araiza-Verduzco, F.; Taboada, P.; Prieto, G.; Rivero, I.A.; Pina-Luis, G.; Alatorre-Meda, M. Bis-Quaternary Ammonium Gemini Surfactants for Gene Therapy: Effects of the Spacer Hydrophobicity on the DNA Complexation and Biological Activity. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2020, 189, 110817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, E.; Little, L.N.; Boatwright, E.A.; Aguilar, D.; Nembaware, H.; Ginegaw, A.; Jordan, A.; Justice, P.; Dominguez, R.; Muleta, M.; et al. The Interaction of a Gemini Surfactant with a DNA Quadruplex. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 30884–30890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietralik, Z.; Kumita, J.R.; Dobson, C.M.; Kozak, M. The Influence of Novel Gemini Surfactants Containing Cycloalkyl Side-Chains on the Structural Phases of DNA in Solution. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2015, 131, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shortall, S.M.; Wettig, S.D. Cationic Gemini Surfactant–Plasmid Deoxyribonucleic Acid Condensates as a Single Amphiphilic Entity. J. Phys. Chem. B 2018, 122, 194–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akram, M. Analyzing the Interaction between Porcine Serum Albumin (PSA) and Ester-Functionalized Cationic Gemini Surfactants. Process Biochem. 2017, 63, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akram, M. Probing Interaction of Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) with the Biodegradable Version of Cationic Gemini Surfactants. J. Mol. Liq. 2019, 276, 519–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akram, M.; Ansari, F.; Din, K.U. Biophysical Investigation of the Interaction between Cationic Biodegradable Cm-E2O-Cm Gemini Surfactants and Porcine Serum Albumin (PSA). Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2019, 206, 520–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gospodarczyk, W.; Kozak, M. Interaction of Two Imidazolium Gemini Surfactants with Two Model Proteins BSA and HEWL. Colloid Polym. Sci. 2015, 293, 2855–2866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwiczak, J.; Iłowska, E.; Wilkowska, M.; Szymańska, A.; Kempka, M.; Dobies, M.; Szutkowski, K.; Kozak, M. The Influence of a Dicationic Surfactant on the Aggregation Process of the IVAGVN Peptide Derived from the Human Cystatin C Sequence (56–61). RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 3237–3249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radziunas-Salinas, Y.; Dominguez_Arca, V.; Cambon, A.; Antelo, P.T.; Prieto, G.; Pardo, A. Long-Chain Cationic Gemini Surfactants as Drug Retention Adjuvant on Liposomes. A Methodological Approach with Atorvastatin. BBA—Biomembr. 2025, 1867, 184419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, J.M.; Malik, A.; Rehman, M.T.; AlAjmi, M.F.; Ahmed, M.Z.; Almutairi, G.O.; Anwer, M.K.; Khan, R.H. Cationic Gemini Surfactant Stimulates Amyloid Fibril Formation in Bovine Liver Catalase at Physiological pH. A Biophysical Study. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 43751–43761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajput, S.M.; Mondal, K.; Kuddushi, M.; Jain, M.; Ray, D.; Aswal, V.K.; Malek, N.I. Formation of Hydrotropic Drug/Gemini Surfactant Based Catanionic Vesicles as Efficient Nano Drug Delivery Vehicles. Colloid Interface Sci. Commun. 2020, 37, 100273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez-Arca, V.; Sabín, J.; García-Río, L.; Bastos, M.; Taboada, P.; Barbosa, S.; Prieto, G. On the Structure and Stability of Novel Cationic DPPC Liposomes Doped with Gemini Surfactants. J. Mol. Liq. 2022, 366, 120230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brycki, B.; Szulc, A.; Babkova, M. Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles with Gemini Surfactants as Efficient Capping and Stabilizing Agents. Appl. Sci. 2020, 11, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P.K.; Srivastava, A.; Ranganath, K.V.S. Gemini Surfactant-stabilized Pd Nanoparticles: Synthesis, Characterization, and Catalytic Application in the Reduction and Reductive Acetylation in the Water Solvent. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2023, 37, e7251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczerewska, O.; Sousa, I.; Martins, R.; Figueiredo, J.; Loureiro, S.; Tedim, J. Gemini Surfactant as a Template Agent for the Synthesis of More Eco-Friendly Silica Nanocapsules. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 8085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roshdy, K.; Mohamed, H.I.; Ahmed, M.H.; El-Dougdoug, W.I.; Abo-Riya, M.A. Gemini Ionic Liquid-Based Surfactants: Efficient Synthesis, Surface Activity, and Use as Inducers for the Fabrication of Cu2 O Nanoparticles. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 31128–31140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaban, S.M.; Taha, A.A.; Elged, A.H.; Taha, S.T.; Sabet, V.M.; Kim, D.-H.; Moustafa, A.H.E. Insights on Gemini Cationic Surfactants Influence AgNPs Synthesis: Controlling Catalytic and Antimicrobial Activity. J. Mol. Liq. 2024, 397, 124071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alejo, T.; Martín-García, B.; Merchán, M.D.; Velázquez, M.M. QDs Supported on Langmuir-Blodgett Films of Polymers and Gemini Surfactant. J. Nanomater. 2013, 2013, 287094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alejo, T.; Paulo, P.M.R.; Merchán, M.D.; Garcia-Fernandez, E.; Costa, S.M.B.; Velázquez, M.M. Influence of 3D Aggregation on the Photoluminescence Dynamics of CdSe Quantum Dot Films. J. Lumin. 2017, 183, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, N.; Urayama, A.; Ikezawa, M.; Kondo, Y. Water-Durable Cesium Lead Halide Perovskite Nanocrystals Passivated with a Cationic Gemini Surfactant. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 9, 2101836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bader, B.; Tantawy, A.H.; Azab, M.; El-Dougdoug, W.I. Novel Synthesized Cationic Gemini Surfactants Bearing Amido Group and TheirApplication in Nanotechonoly. Curr. Sci. Int. 2022, 11, 184–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, F.; Hu, L.; Ji, Z.; Lyu, Y.; Chen, S.; Xu, L.; Hao, J. Highly Interfacial Active Gemini Surfactants as Simple and Versatile Emulsifiers for Stabilizing, Lubricating and Structuring Liquids. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202318926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Guan, X.; Xiao, W.; Chen, R.; Zhou, J.; Ren, F.; Wang, J.; Chen, W.; Li, S.; Qiu, L.; et al. Effective Passivation with Size-Matched Alkyldiammonium Iodide for High-Performance Inverted Perovskite Solar Cells. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2205009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pramanik, A.; Patibandla, S.; Gao, Y.; Gates, K.; Ray, P.C. Water Triggered Synthesis of Highly Stable and Biocompatible 1D Nanowire, 2D Nanoplatelet, and 3D Nanocube CsPbBr3 Perovskites for Multicolor Two-Photon Cell Imaging. JACS Au 2021, 1, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalam, S.; Kamal, M.S.; Patil, S.; Hussain, S.M.S. Role of Counterions and Nature of Spacer on Foaming Properties of Novel Polyoxyethylene Cationic Gemini Surfactants. Processes 2019, 7, 502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Lu, M.; Fan, Y.; Li, Y.; Holmberg, K. Recent Developments on Surfactants for Enhanced Oil Recovery. Tenside Surfactants Deterg. 2021, 58, 164–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massarweh, O.; Abushaikha, A.S. The Use of Surfactants in Enhanced Oil Recovery: A Review of Recent Advances. Energy Rep. 2020, 6, 3150–3178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Azani, K.; Abu-Khamsin, S.; Al-Abdrabalnabi, R.; Kamal, M.S.; Patil, S.; Zhou, X.; Hussain, S.M.S.; Al Shalabi, E. Oil Recovery Performance by Surfactant Flooding: A Perspective on Multiscale Evaluation Methods. Energy Fuels 2022, 36, 13451–13478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Azani, K.; Abu-Khamsin, S.; Kamal, M.S.; Patil, S.; Hussain, S.M.S.; Al-Shehri, D.; Mahmoud, M. Role of Injection Rate on Chemically Enhanced Oil Recovery Using a Gemini Surfactant under Harsh Conditions. Energy Fuels 2024, 38, 3682–3692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalam, S.; Abu-Khamsin, S.A.; Gbadamosi, A.O.; Patil, S.; Kamal, M.S.; Hussain, S.M.S.; Al-Shehri, D.; Al-Shalabi, E.W.; Mohanty, K.K. Static and Dynamic Adsorption of a Gemini Surfactant on a Carbonate Rock in the Presence of Low Salinity Water. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 11936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Li, X.; Li, H.; Liu, S.; Wang, J.; Zhang, P. Application and Synthesis of Gemini Surfactant in Heavy Oil Development. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 8832–8842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhu, F.; Xu, J.; Liu, P.; Chen, S.; Wang, Y. Spontaneous Imbibition and Core Flooding Experiments of Enhanced Oil Recovery in Tight Reservoirs with Surfactants. Energies 2023, 16, 1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oguntade, T.I.; Fadairo, A.S.; Pu, H.; Oni, B.A.; Ogunkunle, T.F.; Tomomewo, O.S.; Nkok, L.Y. Experimental Investigation of Zwitterionic Surfactant for Enhanced Oil Recovery in Unconventional Reservoir: A Study in the Middle Bakken Formation. Colloids Surf. Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2024, 700, 134768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VijayaKumar, S.D.; Zakaria, J.; Ridzuan, N. The Role of Gemini Surfactant and SiO2/SnO/Ni2O3 Nanoparticles as Flow Improver of Malaysian Crude Oil. J. King Saud Univ.—Eng. Sci. 2022, 34, 384–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Biofilm-Forming Strains | Application | References |

|---|---|---|

| A. lannensis | food industry (beverage production) | [26] |

| P. aeruginosa | water installations | [27] |

| C. albicans | medical devices | [28,29,30] |

| Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus | medical devices | [30] |

| B. subtilis and E. coli | petroleum industry | [31] |

| Surfactant Type | Typical Concentration Range | Typical IFT Achieved (Oil/Water) | Reported Incremental Oil Recovery [% OOIP] |

|---|---|---|---|

| cationic gemini | ~500–2500 ppm (≈0.05–0.25 wt%) | Very strong interfacial activity; often reduces IFT to <1 mN/m, and in optimized blends even ultra-low IFT (10−3 mN/m) | ~11–27 in lab/core-flood tests |

| anionic | ~200–2000 ppm (0.02–0.2 wt%) | Good IFT reduction; ~0.6–1 mN/m | ~5–20 in lab studies |

| cationic | ~0.1–1.0 wt% (≈1000–10,000 ppm) | Strong IFT reduction; down to 0.33 mN/m | ~14% in lab studies |

| zwitterionic/nonionic | ~100–2000 ppm | Moderate–strong performance; IFT often <1 mN/m | ~10–30 in lab studies |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kowalczyk, I.; Szulc, A.; Brycki, B. Gemini Surfactants: Advances in Applications and Prospects for the Future. Molecules 2025, 30, 4599. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234599

Kowalczyk I, Szulc A, Brycki B. Gemini Surfactants: Advances in Applications and Prospects for the Future. Molecules. 2025; 30(23):4599. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234599

Chicago/Turabian StyleKowalczyk, Iwona, Adrianna Szulc, and Bogumił Brycki. 2025. "Gemini Surfactants: Advances in Applications and Prospects for the Future" Molecules 30, no. 23: 4599. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234599

APA StyleKowalczyk, I., Szulc, A., & Brycki, B. (2025). Gemini Surfactants: Advances in Applications and Prospects for the Future. Molecules, 30(23), 4599. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234599