The Influence of Y2O3 Dosage on the Performance of Fe60/WC Laser Cladding Coating

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

| Sample | Solution | Ecorr/VSCE | icorr/A cm2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1# | 3.5% NaCl | −0.726 | 2.06 × 10−5 |

| 2# | 3.5% NaCl | −0.837 | 3.01 × 10−5 |

| 3# | 3.5% NaCl | −0.704 | 1.30 × 10−5 |

| 4# | 3.5% NaCl | −0.812 | 3.56 × 10−5 |

| 5# | 3.5% NaCl | −0.838 | 3.91 × 10−5 |

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Fabrication of Laser Cladding Coatings

3.2. Material Characterization and Measurement

4. Conclusions

- (1)

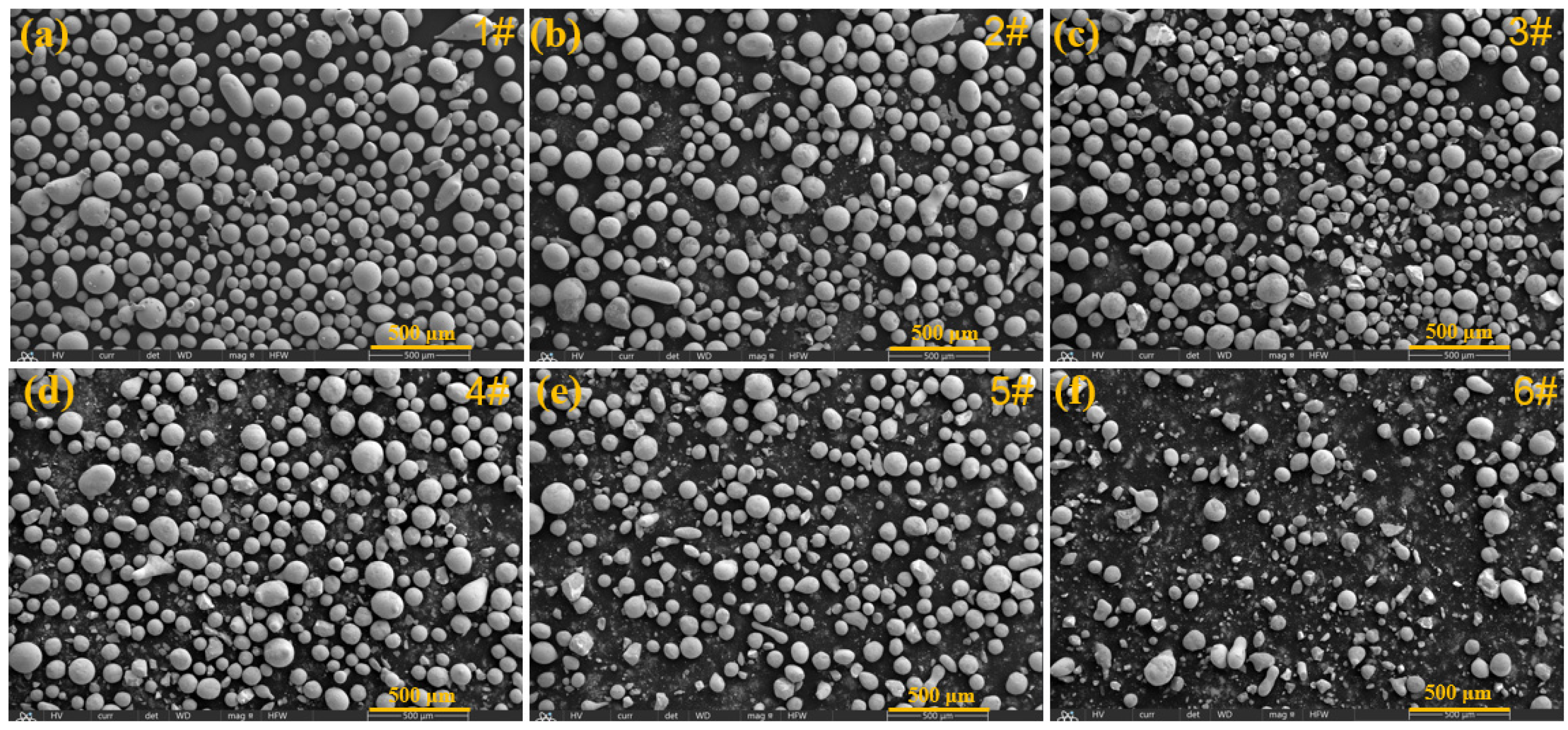

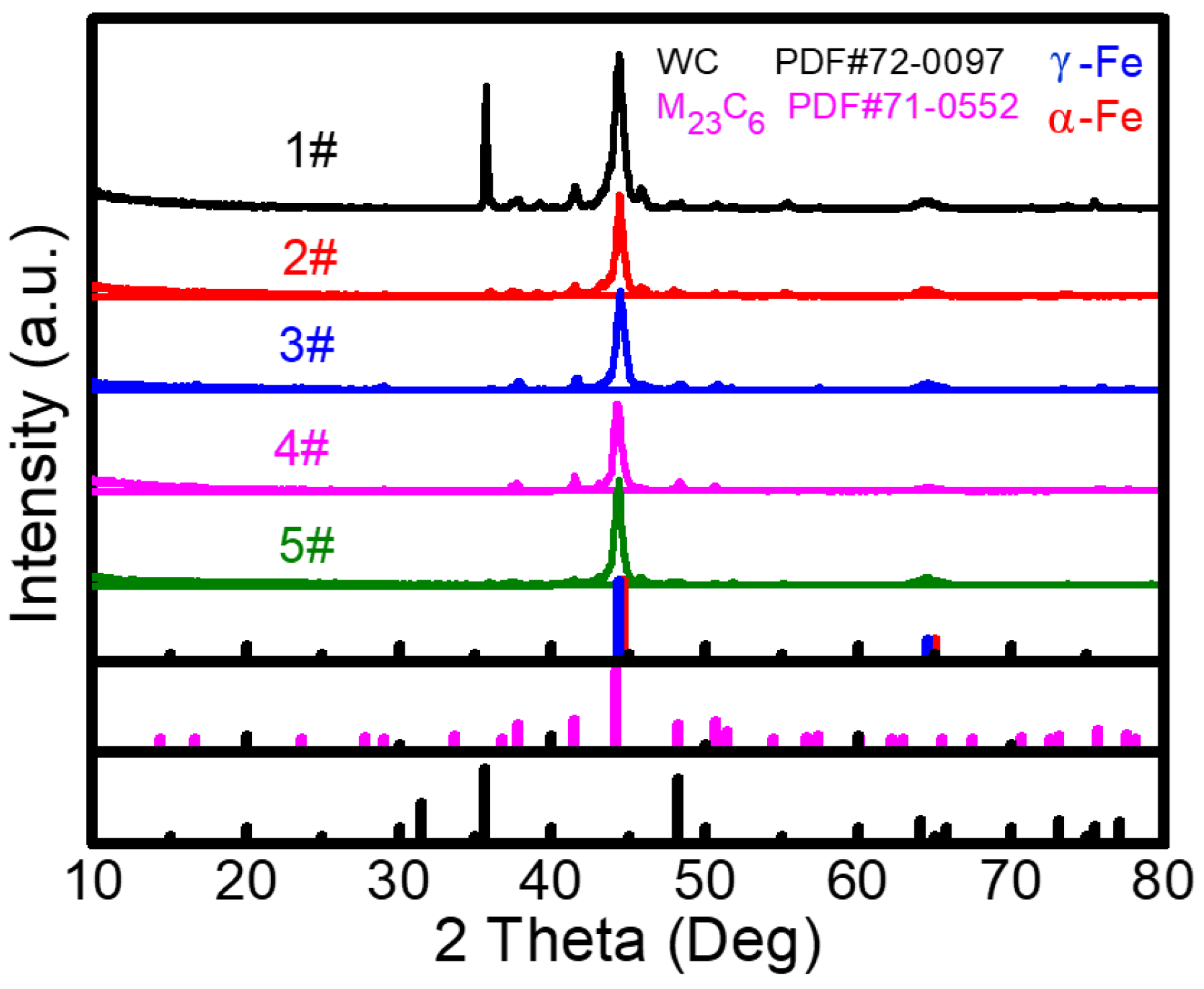

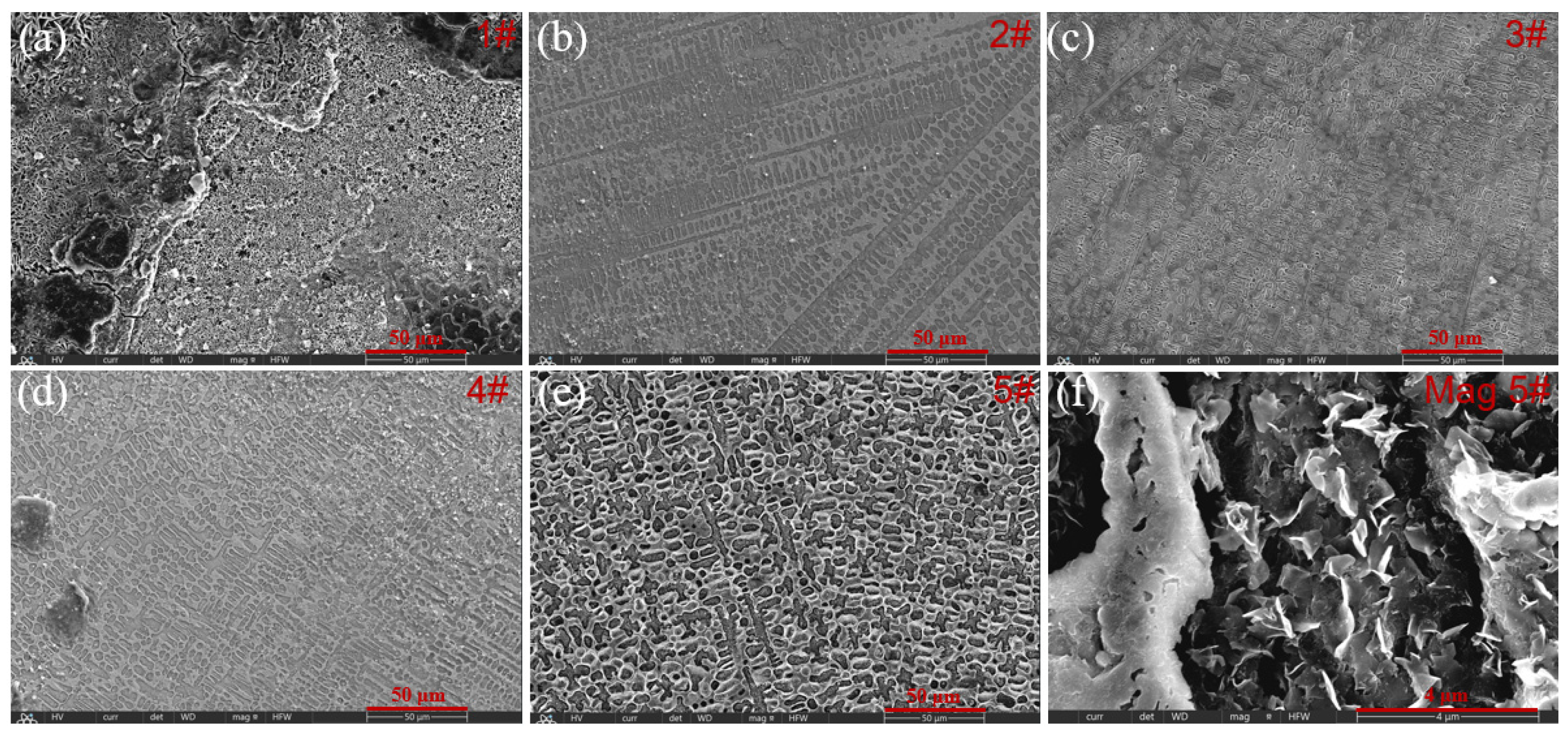

- With the addition of Y2O3, the characteristic diffraction peaks of WC disappear, while the peaks of M23C6 gradually weaken. This indicates that the introduction of Y2O3 promotes the decomposition of WC and inhibits the formation of metal carbides. SEM result verifies the formation of abundant grid-like structures in the 3# sample with 2.5 wt% Y2O3, further demonstrating the uniform distribution of decomposed W within the Fe matrix. When the Y2O3 content is more than 5 wt%, excessive Y2O3 introduces a large amount of O, which reacts with C to form CO2 gas. This reaction reduces the content of newly generated carbides and increases the number of surface pores.

- (2)

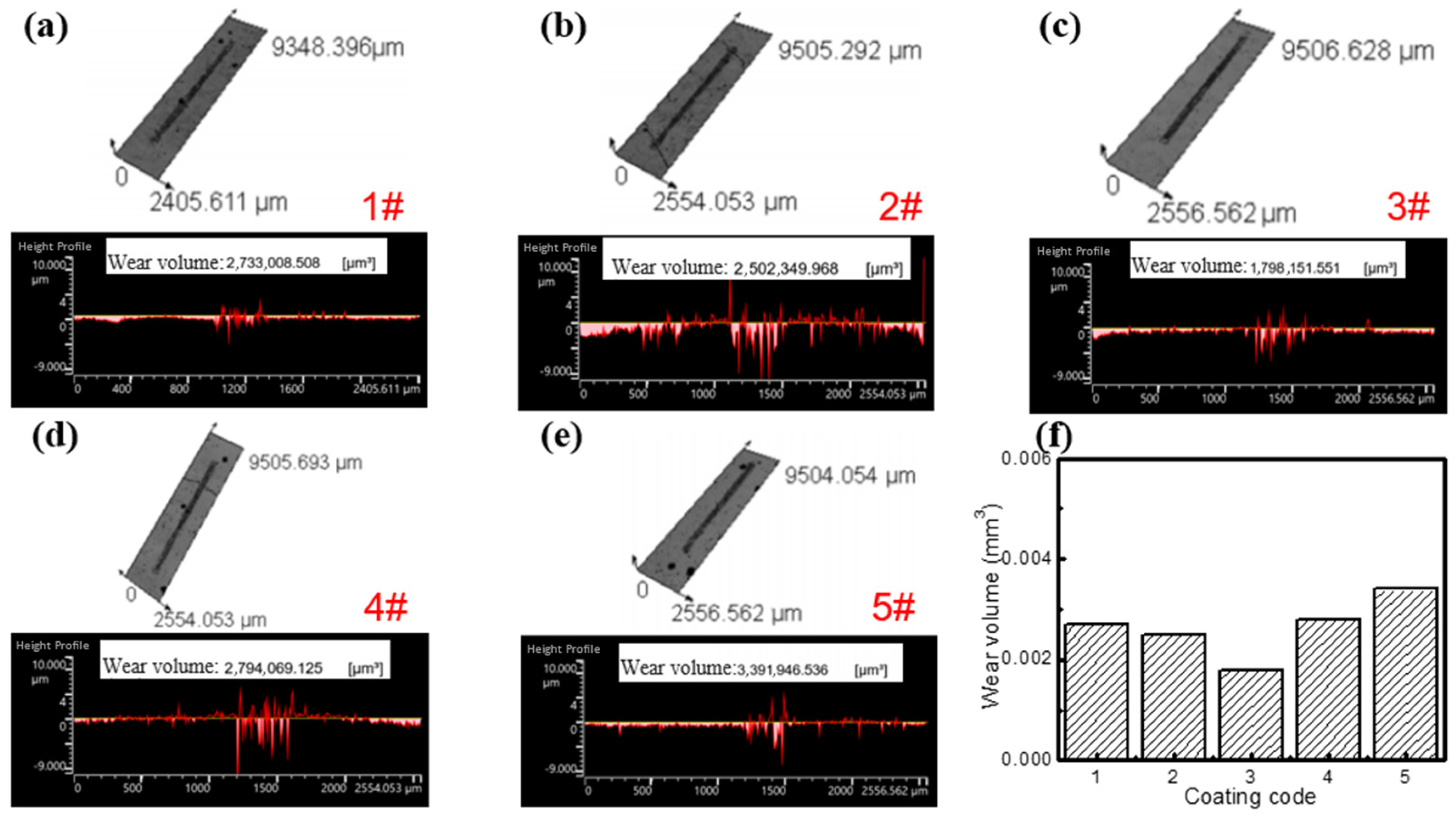

- The dosage of Y2O3 has a significant impact on the hardness of the cladding coating. The coating hardness initially increases and then decreases with increasing Y2O3 addition. When the content of Y2O3 is 2.5 wt%, the 3# sample presents the maximum average hardness of 861.97 HV, which is 3.3 times that of the substrate. The friction coefficient of different cladding coatings was tested using Si3N4 grinding balls. The 3# sample also exhibits the lowest friction coefficient (0.675) and the smallest wear volume of 1.8 × 10−3 mm3. Therefore, the Fe60/WC/Y2O3 cladding coating with 2.5 wt% Y2O3 demonstrates the optimal wear resistance.

- (3)

- Electrochemical measurement was conducted using polished cladding coating encapsulated with epoxy resin as the working electrode. Tafel curves of different samples were tested. The 3# sample (with 2.5% Y2O3) presents the most positive corrosion potential (−0.704 V) and the lowest corrosion current density (1.30 × 10−5 A cm−2). This indicates its superior corrosion resistance in 3.5% NaCl solution, which is attributed to the improved surface quality and the formation of a W-reinforced grid structure.

- (4)

- The incorporation of Y2O3 additive enhances the interfacial bonding between the metal matrix and WC reinforcement by promoting the decomposition of WC. This microstructural refinement results in a significant improvement in the coating’s hardness, wear resistance, and corrosion resistance. These findings provide a viable strategy for fabricating high-performance composite coatings on steel substrates, which can substantially enhance the durability and reliability of critical equipment components. Consequently, this approach contributes to extending the service life of repaired parts, improving operational reliability, and reducing maintenance costs.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhao, P.; Shi, Z.; Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Cao, Z.; Zhao, M.; Liang, J. A Review of the Laser Cladding of Metal-Based Alloys, Ceramic-Reinforced Composites, Amorphous Alloys, and High-Entropy Alloys on Aluminum Alloys. Lubricants 2023, 11, 482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Xue, P.; Lan, Q.; Meng, G.; Ren, Y.; Yang, Z.; Xu, P.; Liu, Z. Recent research and development status of laser cladding: A review. Opt. Laser Technol. 2021, 138, 106915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ding, Y.; Yang, L.; Sun, R.; Zhang, T.; Yang, X. Research and progress of laser cladding on engineering alloys: A review. J. Manuf. Process. 2021, 66, 341–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Zhang, Z.; Xiang, D.; Ju, J. Research and Progress of Laser Cladding: Process, Materials and Applications. Coatings 2022, 12, 1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, D.; Wang, G.; Dong, W.; Hong, X.; Guo, C. Recent Advance on Metal Carbides Reinforced Laser Cladding Coatings. Molecules 2025, 30, 1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Wang, J.; Xu, J.; Cheng, X.; Jing, C.; Chen, Z.; Ru, H.; Liu, Y.; Jiao, J. Preparing WC-Ni coatings with laser cladding technology: A review. Mater. Today Commun. 2023, 37, 106939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Lin, Y.; Peng, L.; Kang, X.; Wang, X. Progress in Microstructure Design and Control of High-Hardness Fe-Based Alloy Coatings via Laser Cladding. Coatings 2024, 14, 1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Shi, W.; Xie, L.; Gong, M.; Huang, J.; Xie, Y.; He, K. Study on the effect of Ni60 transition coating on microstructure and mechanical properties of Fe/WC composite coating by laser cladding. Opt. Laser Technol. 2023, 163, 109387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.Z.; Hao, H.; Gao, Q.; Cao, Y.B.; Han, R.H.; Qi, H.B. Strengthening mechanism and high-temperature properties of H13 + WC/Y2O3 laser-cladding coatings. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2021, 405, 126544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Yang, F.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, T.; Wang, H.; Xu, Y.; Ma, Q. Influence of CeO2 addition on forming quality and microstructure of TiCx-reinforced CrTi4-based laser cladding composite coating. Mater. Charact. 2021, 171, 110732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Yang, Q.; Yu, Z.; Wang, H.; Zhang, T. Influence of Y2O3 addition on the microstructure of TiC reinforced Ti-based composite coating prepared by laser cladding. Mater. Charact. 2022, 189, 111962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Luo, X.; Li, G.J. Effect of Y2O3 on the sliding wear resistance of TiB/TiC-reinforced composite coatings fabricated by laser cladding. Wear 2014, 310, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, F.; Li, K.; Shi, W.; Zhu, Z. Effect of Y2O3 Content on Microstructure and Corrosion Properties of Laser Cladding Ni-Based/WC Composite Coated on 316L Substrate. Coatings 2023, 13, 1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, L.; Yang, Y.; Zhu, W.; Sun, J.; Wu, J.; Xu, H.; Yan, L.; Yang, A.; Xu, Z. Stress Distribution in Wear Analysis of Nano-Y2O3 Dispersion Strengthened Ni-Based μm-WC Composite Material Laser Coating. Materials 2024, 17, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhu, Z.; Peng, Y.; Shen, G. Phase evolution and wear resistance of in-situ synthesized (Cr, W)23C6-WC composite ceramics reinforced Fe-based composite coatings produced by laser cladding. Vacuum 2021, 190, 110242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, M.; Wang, L.; Gao, Z.; Yang, X.; Liu, T.; Zhan, X. Microstructure and element distribution characteristics of Y2O3 modulated WC reinforced coating on Invar alloys by laser cladding. Opt. Laser Technol. 2022, 153, 108205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Fu, S.; Lu, H.; Li, W. Process optimization, microstructure characterization, and tribological performance of Y2O3 modified Ti6Al4V-WC gradient coating produced by laser cladding. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2024, 478, 130496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.Z.; Wang, X.; Zhang, G.A. Corrosion behaviour of 13Cr stainless steel under stress and crevice in 3.5 wt.% NaCl solution. Corros. Sci. 2020, 163, 108290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Ma, K.; Cui, J. Corrosion behaviors and mechanism of AlxCrFeMnCu high-entropy alloys in a 3.5 wt% NaCl solution. Corros. Sci. 2024, 233, 112087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Ma, A.; Zhang, L.; Zheng, Y. Intergranular erosion corrosion of pure copper tube in flowing NaCl solution. Corros. Sci. 2022, 201, 110304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Kang, C.Y.; Bang, K.S. Weld metal impact toughness of electron beam welded 9% Ni steel. J. Mater. Sci. 2001, 36, 1197–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Wang, Z.Y.; Wang, M.S.; Wang, R.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, C.H.; Wu, C.L.; Chen, H.T.; Chen, J. Microstructure evolution, corrosion and corrosive wear properties of NbC-reinforced FeNiCoCr-based high entropy alloys coatings fabricated by laser cladding. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2025, 171, 109352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Fe | C | Cr | Si | Ni | B |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 60.2 wt% | 2.8 wt% | 20.5 wt% | 3.0 wt% | 9.5 wt% | 4.0 wt% |

| Sample Code | Fe60 (g) | WC (g) | Y2O3 (g) | Y2O3 Fraction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1# | 36 | 4 | 0 | 0% |

| 2# | 35 | 4 | 0.5 | 1.3% |

| 3# | 34 | 4 | 1 | 2.5% |

| 4# | 33 | 4 | 2 | 5.0% |

| 5# | 33 | 4 | 3 | 7.5% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jiang, H.; Jiang, D.; Guo, C.; Hong, X. The Influence of Y2O3 Dosage on the Performance of Fe60/WC Laser Cladding Coating. Molecules 2025, 30, 4598. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234598

Jiang H, Jiang D, Guo C, Hong X. The Influence of Y2O3 Dosage on the Performance of Fe60/WC Laser Cladding Coating. Molecules. 2025; 30(23):4598. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234598

Chicago/Turabian StyleJiang, Haiyan, Dazhi Jiang, Chenguang Guo, and Xiaodong Hong. 2025. "The Influence of Y2O3 Dosage on the Performance of Fe60/WC Laser Cladding Coating" Molecules 30, no. 23: 4598. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234598

APA StyleJiang, H., Jiang, D., Guo, C., & Hong, X. (2025). The Influence of Y2O3 Dosage on the Performance of Fe60/WC Laser Cladding Coating. Molecules, 30(23), 4598. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234598