NCIVISION: A Siamese Neural Network for Molecular Similarity Prediction MEP and RDG Images

Abstract

1. Introduction

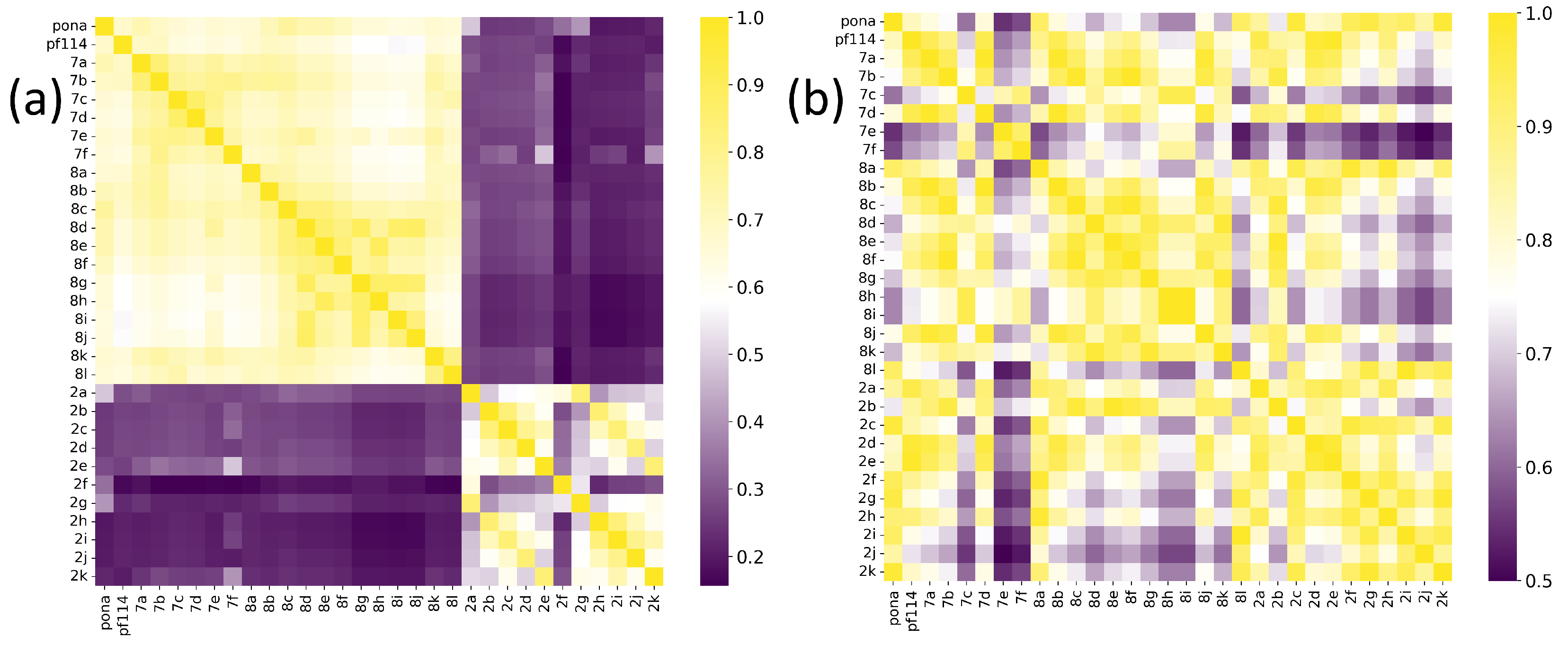

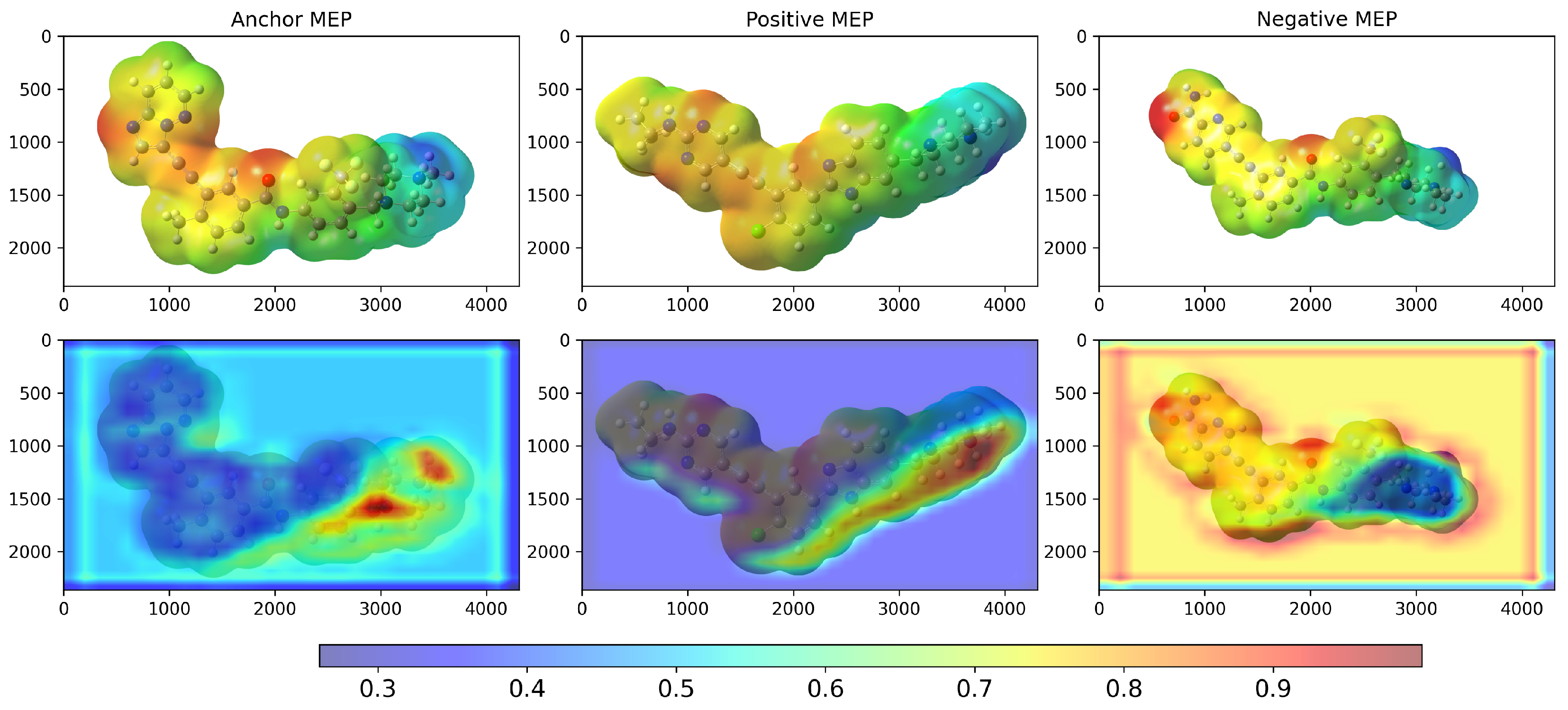

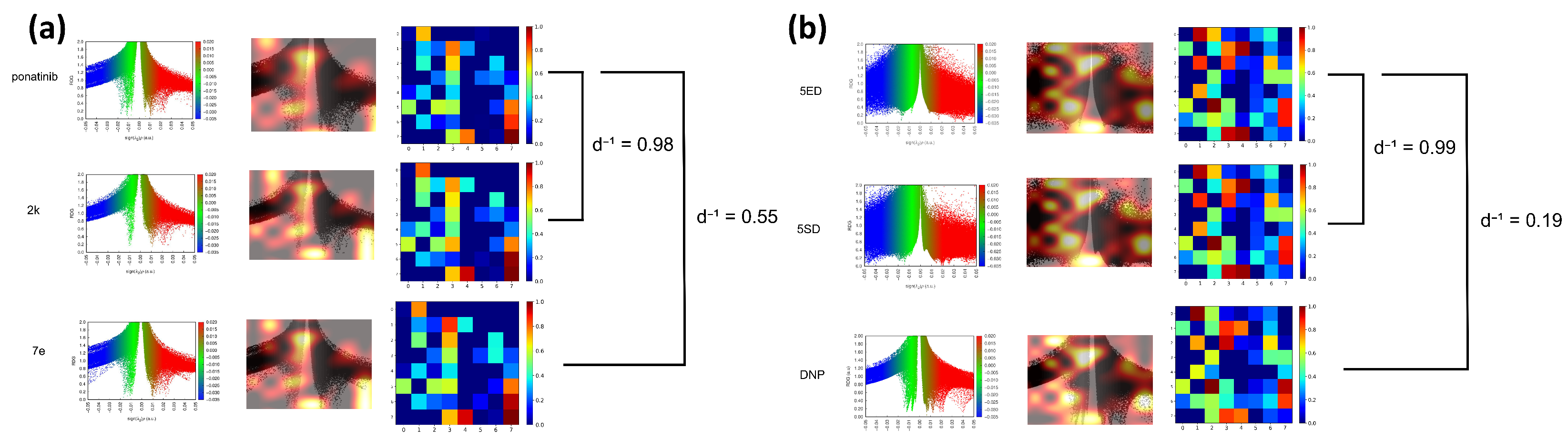

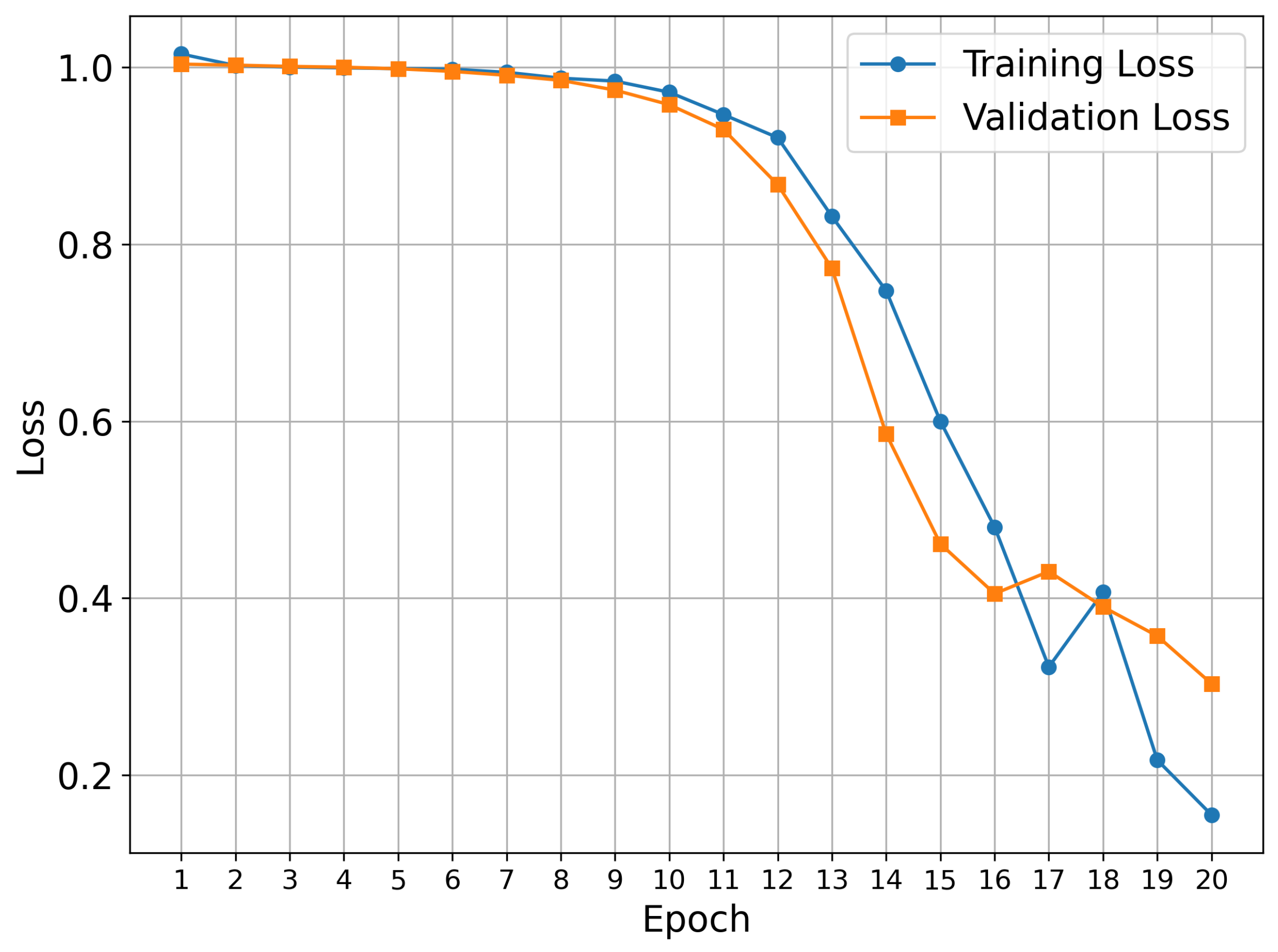

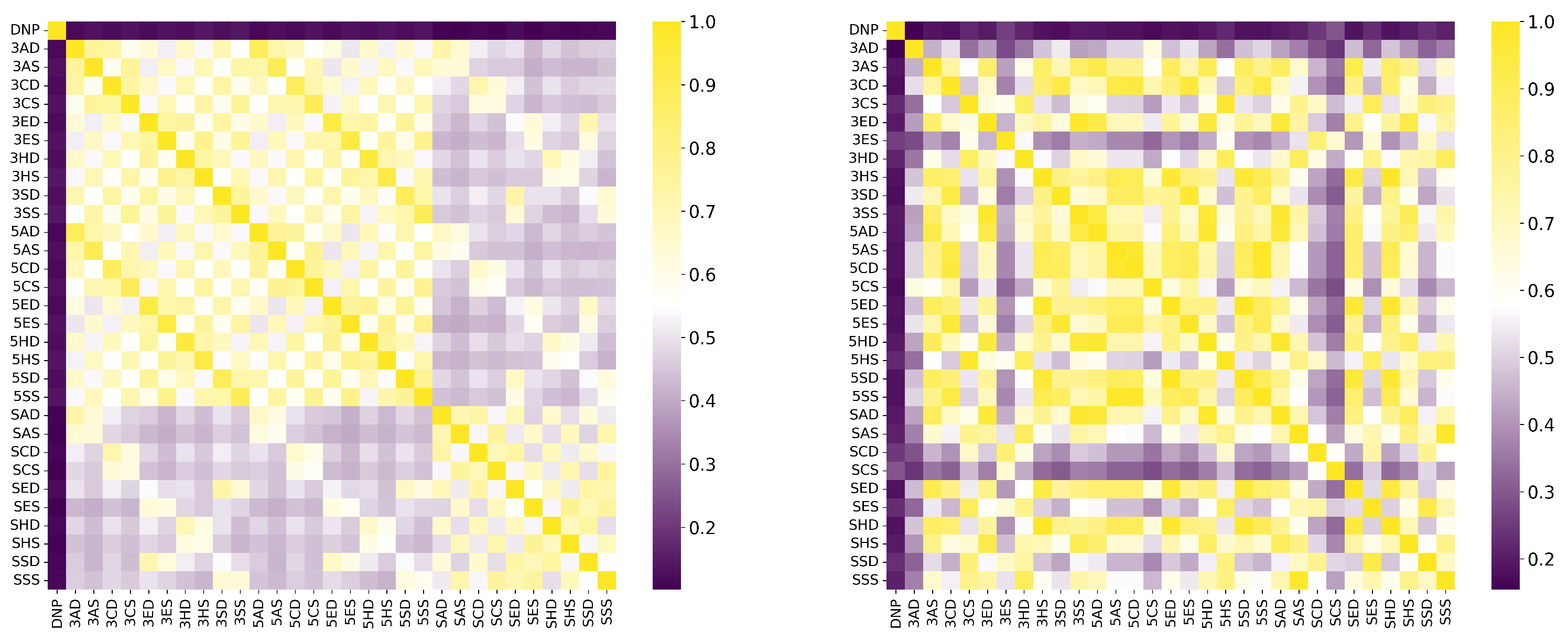

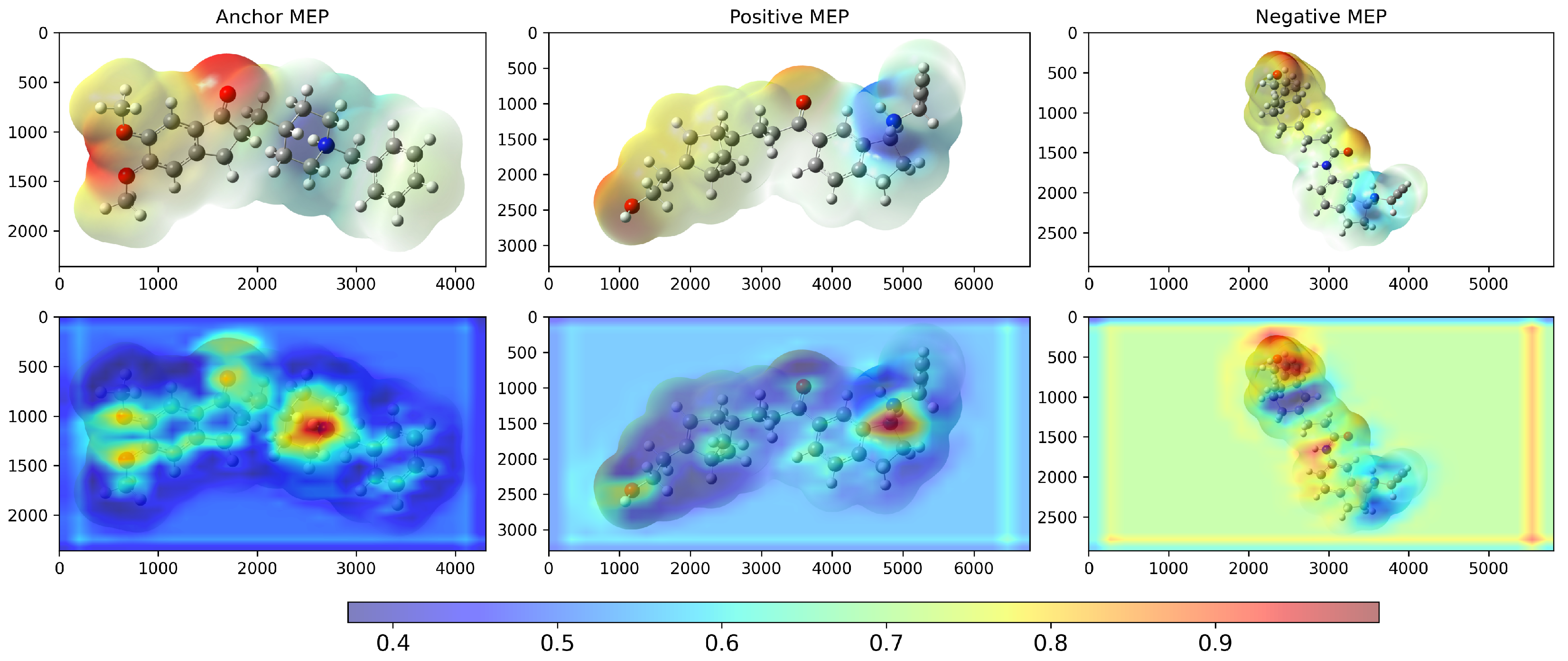

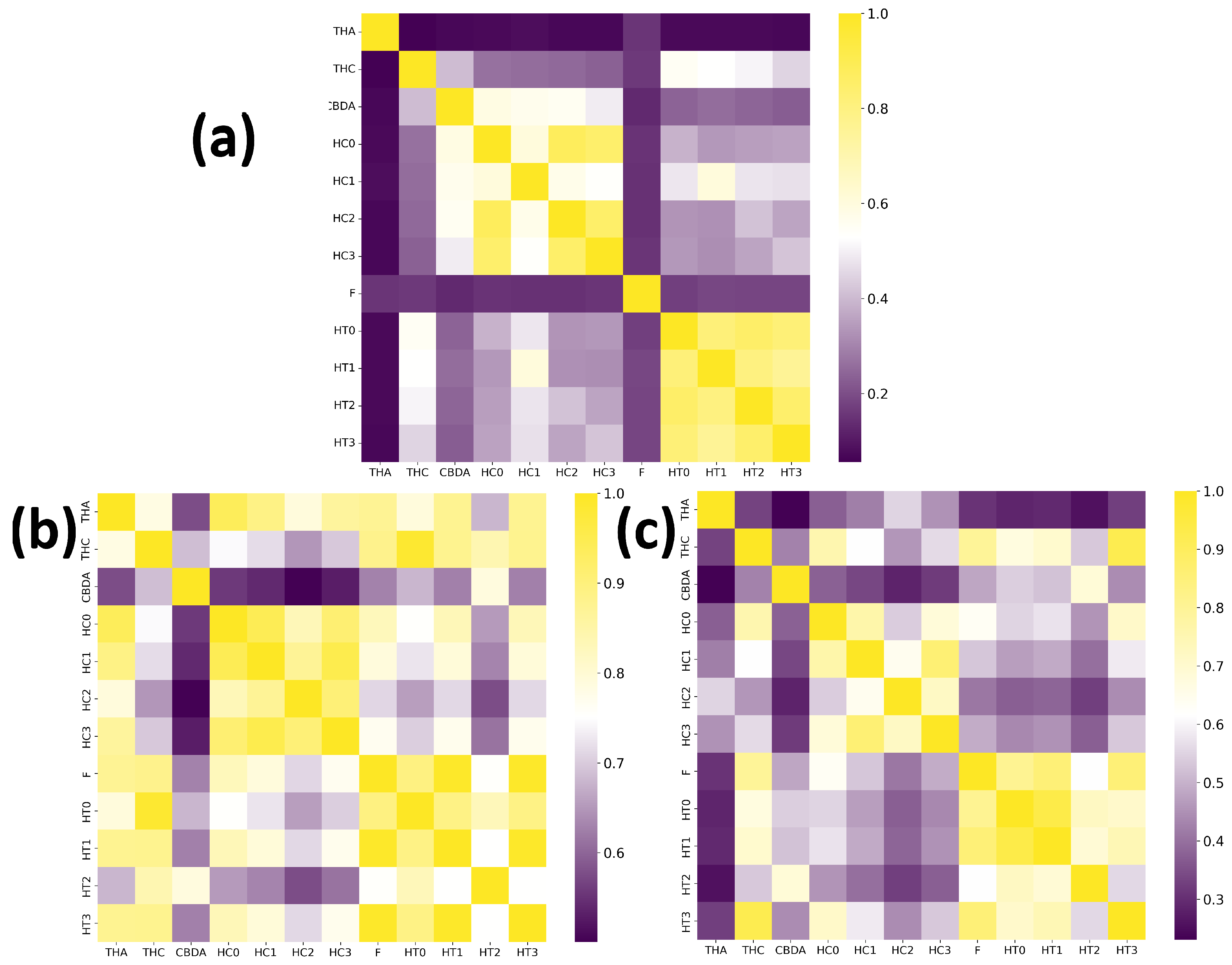

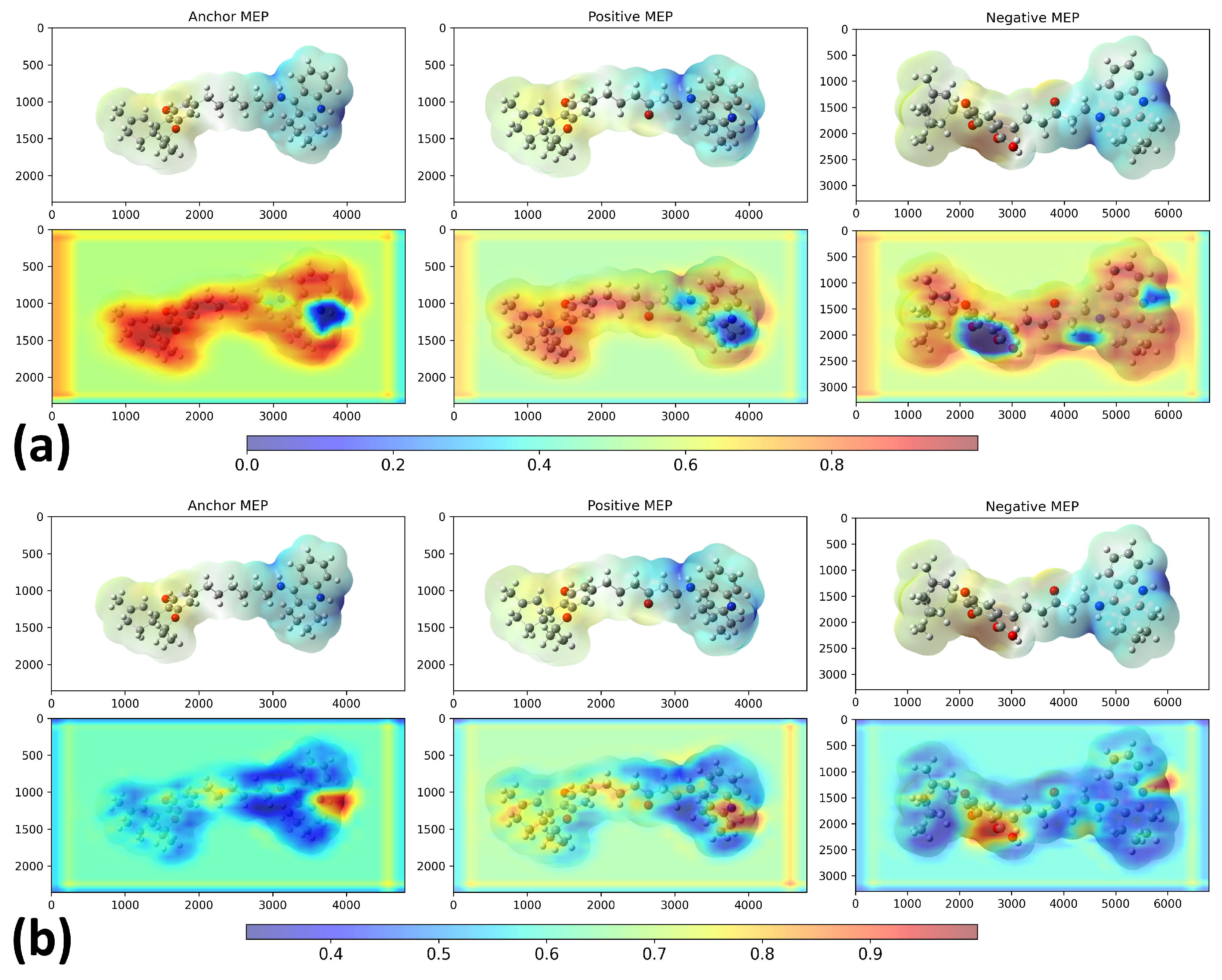

2. Results and Discussion

3. Methods

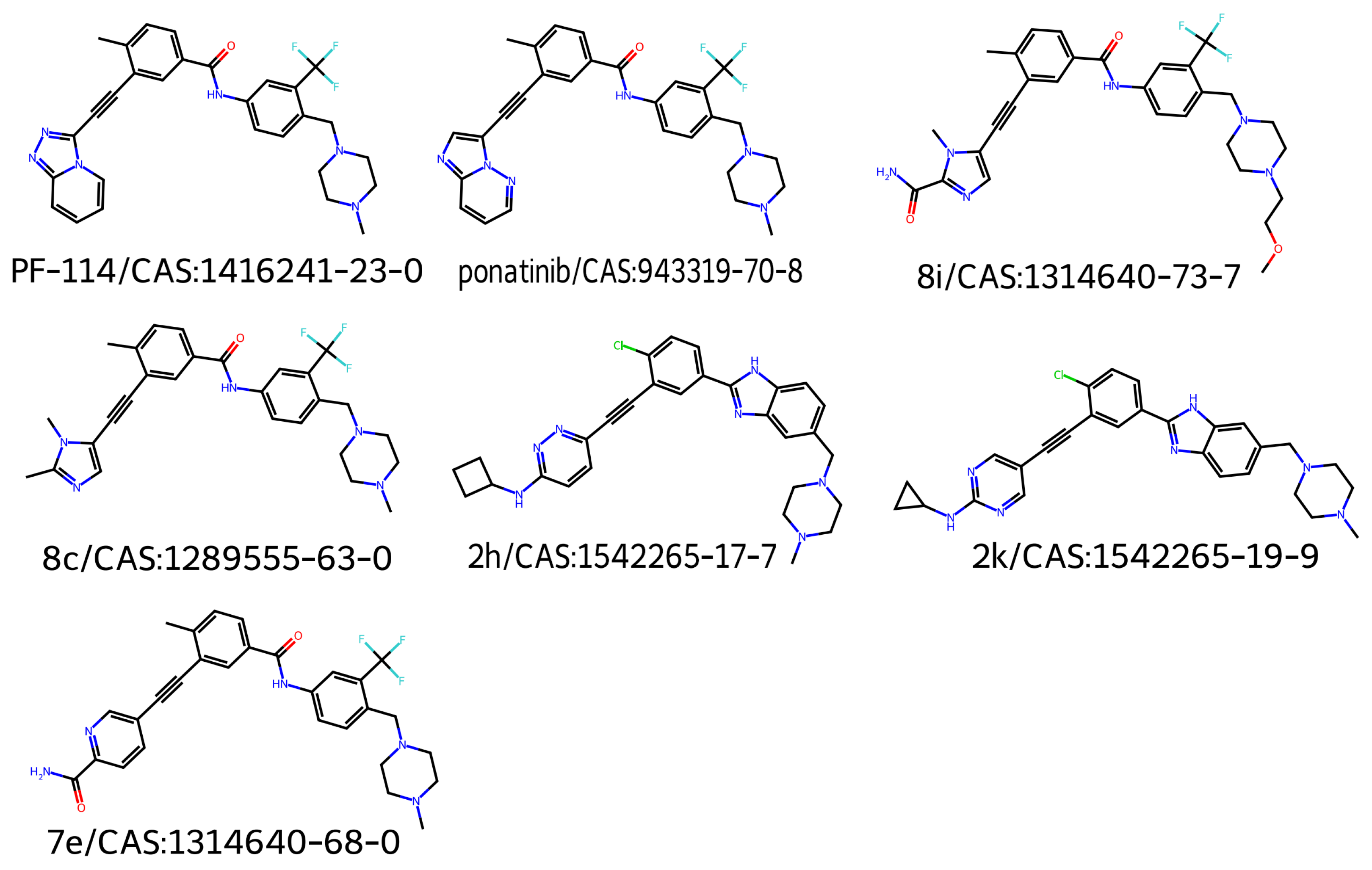

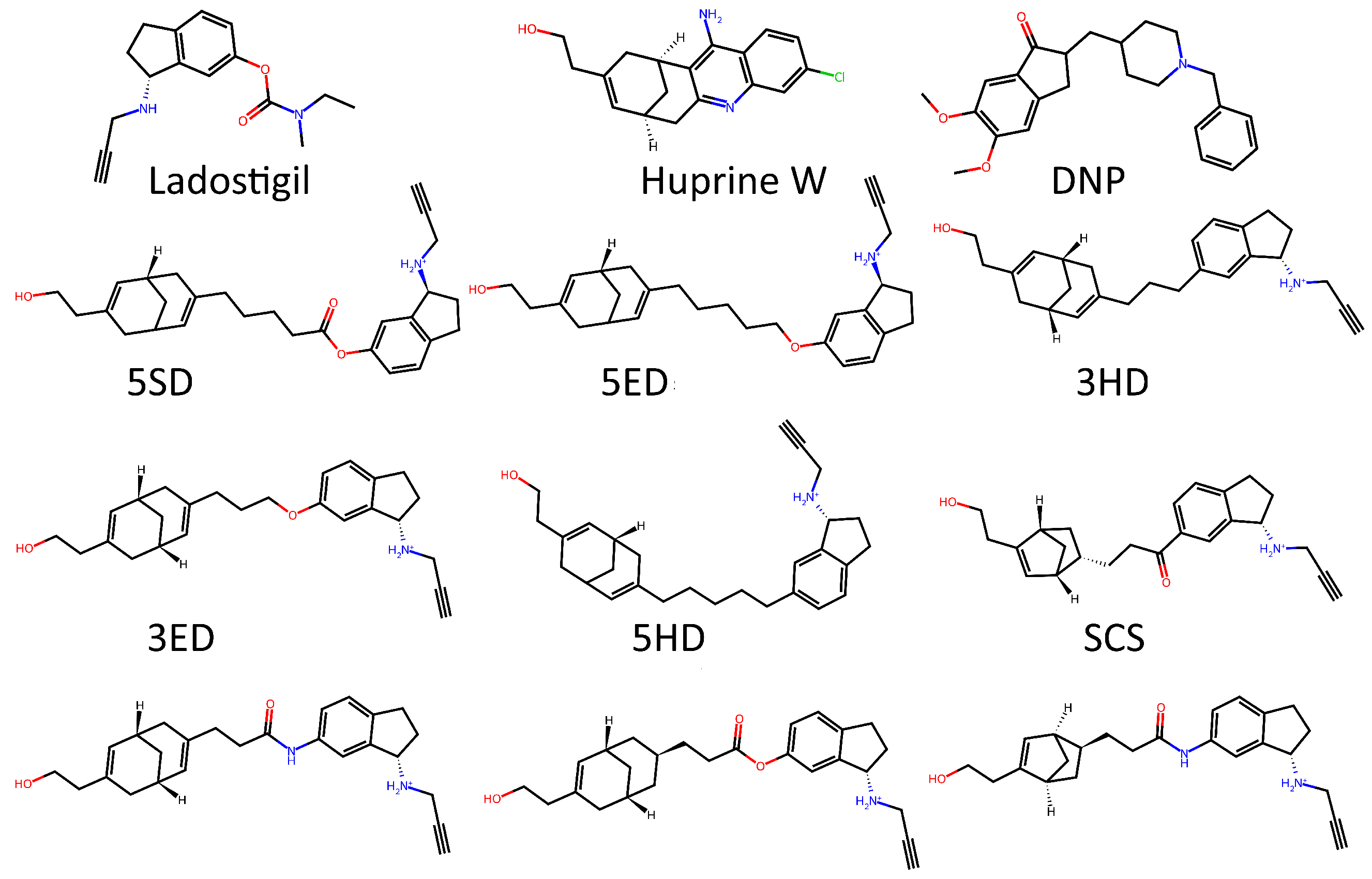

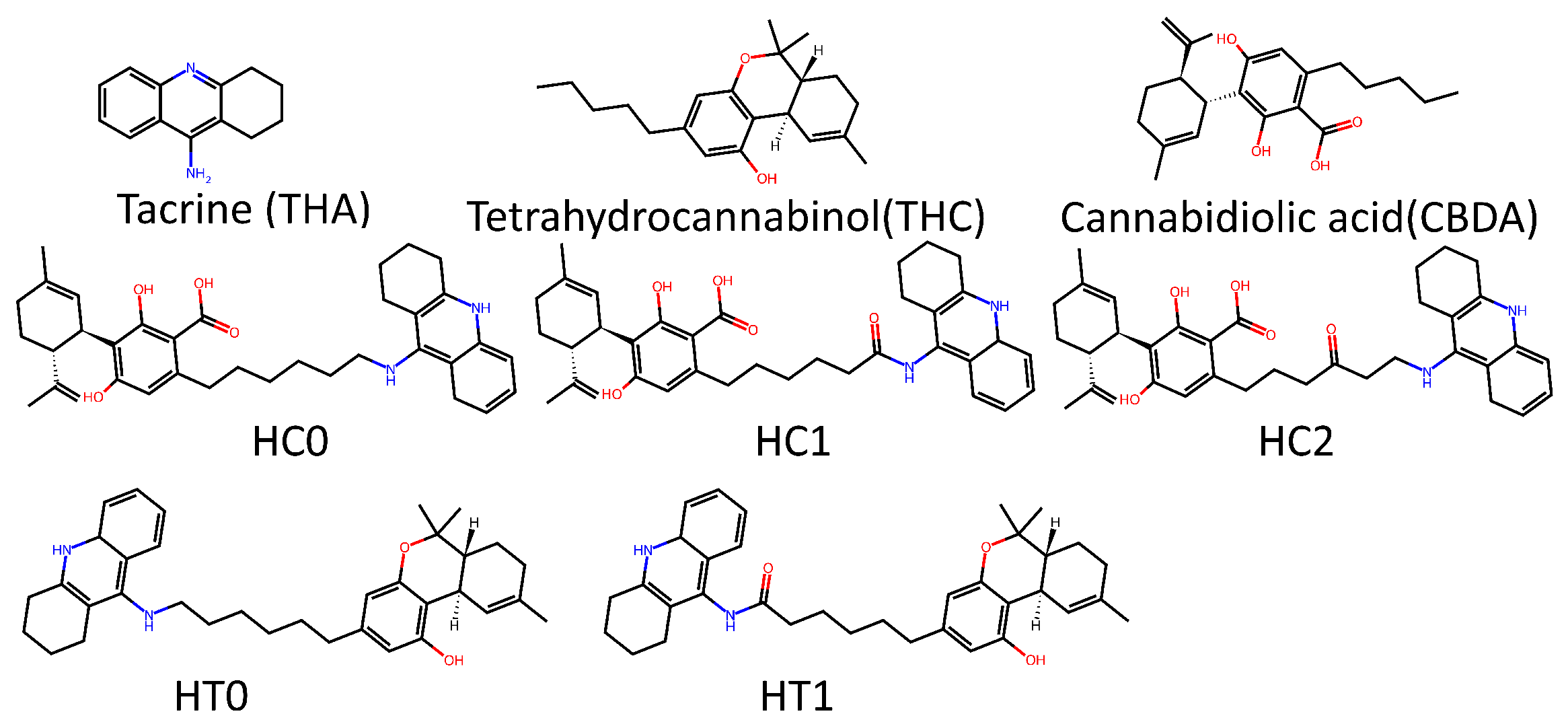

3.1. Datasets

3.2. Model Architecture

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ramos, M.C.; Collison, C.J.; White, A.D. A review of large language models and autonomous agents in chemistry. Chem. Sci. 2025, 16, 2514–2572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilnicka, A.; Schneider, G. Designing molecules with autoencoder networks. Nat. Comput. Sci. 2023, 3, 922–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ochiai, T.; Inukai, T.; Akiyama, M.; Furui, K.; Ohue, M.; Matsumori, N.; Inuki, S.; Uesugi, M.; Sunazuka, T.; Kikuchi, K.; et al. Variational autoencoder-based chemical latent space for large molecular structures with 3D complexity. Commun. Chem. 2023, 6, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miccio, L.A.; Schwartz, G.A. From chemical structure to quantitative polymer properties prediction through convolutional neural networks. Polymer 2020, 193, 122341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Di, J.; Wang, D.; Dai, X.; Hua, Y.; Gao, X.; Zheng, A.; Gao, J. State-of-the-art review of artificial neural networks to predict, characterize and optimize pharmaceutical formulation. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coley, C.W.; Jin, W.; Rogers, L.; Jamison, T.F.; Jaakkola, T.S.; Green, W.H.; Barzilay, R.; Jensen, K.F. A graph-convolutional neural network model for the prediction of chemical reactivity. Chem. Sci. 2019, 10, 370–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Shim, Y.; Lee, F.; Rammohan, A.; Goyal, S.; Shim, M.; Jeong, C.; Kim, D.S. Prediction and interpretation of polymer properties using the graph convolutional network. ACS Polym. Au 2022, 2, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, N.; Qu, X.; Trozzi, F.; Elsaied, M.; Karki, N.; Tao, Y.; Zoltowski, B.; Larson, E.C.; Kraka, E. Ssnet: A deep learning approach for protein-ligand interaction prediction. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altalib, M.K.; Salim, N. Similarity-based virtual screen using enhanced Siamese deep learning methods. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 4769–4786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzopardi, J.; Ebejer, J.P. LigityScore: A CNN-Based Method for Binding Affinity Predictions. In Proceedings of the International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies, Virtual, 11–13 February 2021; pp. 18–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanavati, M.A.; Ahmadi, S.; Rohani, S. A machine learning approach for the prediction of aqueous solubility of pharmaceuticals: A comparative model and dataset analysis. Digit. Discov. 2024, 3, 2085–2104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Gong, K.; Jiang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Li, T. MolRWKV: Conditional Molecular Generation Model Using Local Enhancement and Graph Enhancement. J. Comput. Chem. 2025, 46, e70100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Lu, Y.; Zang, T. CNN-DDI: A learning-based method for predicting drug–drug interactions using convolution neural networks. BMC Bioinform. 2022, 23, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, X.; Dong, K.; Ma, L.; Sutcliffe, R.; He, F.; Chen, S.; Feng, J. Drug-drug interaction extraction via recurrent hybrid convolutional neural networks with an improved focal loss. Entropy 2019, 21, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Llaneza, D.; Ulander, S.; Gogishvili, D.; Nittinger, E.; Zhao, H.; Tyrchan, C. Siamese Recurrent Neural Network with a Self-Attention Mechanism for Bioactivity Prediction. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 11086–11094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Yao, T.; Luo, J.; Yi, H.; Han, X.; Pan, W.; Xue, Q.; Liu, X.; Fu, J.; Zhang, A. ChemNTP: Advanced Prediction of Neurotoxicity Targets for Environmental Chemicals Using a Siamese Neural Network. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 22646–22656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanni, L.; Minchio, G.; Brahnam, S.; Sarraggiotto, D.; Lumini, A. Closing the Performance Gap between Siamese Networks for Dissimilarity Image Classification and Convolutional Neural Networks. Sensors 2021, 21, 5809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boto, R.A.; Contreras-García, J.; Tierny, J.; Piquemal, J.P. Interpretation of the reduced density gradient. Mol. Phys. 2015, 114, 1406–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra, C.; Burgos, J.; Ayarde-Henríquez, L.; Chamorro, E. Formulating Reduced Density Gradient Approaches for Noncovalent Interactions. J. Phys. Chem. A 2024, 128, 6158–6166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noens, L.; Hensen, M.; Kucmin-Bemelmans, I.; Lofgren, C.; Gilloteau, I.; Vrijens, B. Measurement of adherence to BCR-ABL inhibitor therapy in chronic myeloid leukemia: Current situation and future challenges. Haematologica 2014, 99, 437–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, B.; Quiroz, J.; Priefer, R. Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitors for Alzheimer’s disease: Past, Present, and Potential Future. Med. Res. Arch. 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Li, P.; Gao, Y.; Song, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Su, H.; Yang, B.; Li, L.; Li, G.; Gong, N.; et al. Discovery of a Candidate Containing an (S)-3, 3-Difluoro-1-(4-methylpiperazin-1-yl)-2, 3-dihydro-1H-inden Scaffold as a Highly Potent Pan-Inhibitor of the BCR-ABL Kinase Including the T315I-Resistant Mutant for the Treatment of Chronic Myeloid Leukemia. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 64, 7434–7452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turkina, A.; Vinogradova, O.; Lomaia, E.; Shatokhina, E.; Shukhov, O.; Chelysheva, E.; Shikhbabaeva, D.; Nemchenko, I.; Petrova, A.; Bykova, A.; et al. Phase-1 study of vamotinib (PF-114), a 3rd generation BCR::ABL1 tyrosine kinase-inhibitor, in chronic myeloid leukaemia. Ann. Hematol. 2025, 104, 2707–2715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, M.; Huang, W.S.; Wen, D.; Zhu, X.; Wang, Y.; Metcalf, C.A.; Liu, S.; Chen, I.; Romero, J.; Zou, D.; et al. Discovery of 5-(arenethynyl) hetero-monocyclic derivatives as potent inhibitors of BCR–ABL including the T315I gatekeeper mutant. Bioorganic Med. Chem. Lett. 2011, 21, 3743–3748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selvaraju, R.R.; Cogswell, M.; Das, A.; Vedantam, R.; Parikh, D.; Batra, D. Grad-CAM: Visual Explanations from Deep Networks via Gradient-Based Localization. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 618–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mian, A.A.; Rafiei, A.; Haberbosch, I.; Zeifman, A.; Titov, I.; Stroylov, V.; Metodieva, A.; Stroganov, O.; Novikov, F.; Brill, B.; et al. PF-114, a potent and selective inhibitor of native and mutated BCR/ABL is active against Philadelphia chromosome-positive (Ph+) leukemias harboring the T315I mutation. Leukemia 2014, 29, 1104–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becke, A.D. Density-functional thermochemistry. I. The effect of the exchange-only gradient correction. J. Chem. Phys. 1992, 96, 2155–2160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Yang, W.; Parr, R.G. Development of the Colle-Salvetti correlation-energy formula into a functional of the electron density. Phys. Rev. B 1988, 37, 785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vosko, S.H.; Wilk, L.; Nusair, M. Accurate spin-dependent electron liquid correlation energies for local spin density calculations: A critical analysis. Can. J. Phys. 1980, 58, 1200–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, P.J.; Devlin, F.J.; Chabalowski, C.F.; Frisch, M.J. Ab initio calculation of vibrational absorption and circular dichroism spectra using density functional force fields. J. Phys. Chem. 1994, 98, 11623–11627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marenich, A.V.; Cramer, C.J.; Truhlar, D.G. Universal Solvation Model Based on Solute Electron Density and on a Continuum Model of the Solvent Defined by the Bulk Dielectric Constant and Atomic Surface Tensions. J. Phys. Chem. B 2009, 113, 6378–6396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Petersson, G.A.; Nakatsuji, H.; et al. Gaussian, version 16. Gaussian~16 Revision C.01, 2016. Gaussian Inc.: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Dennington, R.; Keith, T.A.; Millam, J.M. GaussView, version 4.1.2; Semichem Inc.: Shawnee Mission, KS, USA, 2007.

- Lu, T.; Chen, F. Multiwfn: A multifunctional wavefunction analyzer. J. Comput. Chem. 2011, 33, 580–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphrey, W.; Dalke, A.; Schulten, K. VMD: Visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. 1996, 14, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroff, F.; Kalenichenko, D.; Philbin, J. FaceNet: A unified embedding for face recognition and clustering. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Boston, MA, USA, 7–12 June 2015; pp. 815–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vieira, R.C.; Nascimento, L.d.A.; Nascimento, A.A.; Alves, N.R.d.M.; Nascimento, É.C.M.; Martins, J.B.L. NCIVISION: A Siamese Neural Network for Molecular Similarity Prediction MEP and RDG Images. Molecules 2025, 30, 4589. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234589

Vieira RC, Nascimento LdA, Nascimento AA, Alves NRdM, Nascimento ÉCM, Martins JBL. NCIVISION: A Siamese Neural Network for Molecular Similarity Prediction MEP and RDG Images. Molecules. 2025; 30(23):4589. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234589

Chicago/Turabian StyleVieira, Rafael Campos, Letícia de A. Nascimento, Arthur Alves Nascimento, Nicolas Ricardo de Melo Alves, Érica C. M. Nascimento, and João B. L. Martins. 2025. "NCIVISION: A Siamese Neural Network for Molecular Similarity Prediction MEP and RDG Images" Molecules 30, no. 23: 4589. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234589

APA StyleVieira, R. C., Nascimento, L. d. A., Nascimento, A. A., Alves, N. R. d. M., Nascimento, É. C. M., & Martins, J. B. L. (2025). NCIVISION: A Siamese Neural Network for Molecular Similarity Prediction MEP and RDG Images. Molecules, 30(23), 4589. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234589