Application of Catalysts Prepared by Solution Combustion Synthesis in Dry Reforming of Methane

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Solution Combustion Synthesis as Method of Preparing Catalysts for Dry Reforming of Methane

2.1. History of Solution Combustion Synthesis

2.2. Dry Reforming of Methane for Synthesis Gas Production

2.3. Method of Preparing Catalysts

2.4. SCS Catalysts for Dry Reforming of Methane

2.5. Effect of Fuel Content on Solution Combustion

- They are sources of C and H which, when burned, form CO2 and H2O and release heat;

- They form complexes with metal ions and provide a source of nitrogen (during solution combustion, CO and NH3 are formed, which are reactants necessary for obtaining metals in the solution).

- The fuel must be soluble in water and used to improve solubility;

- The fuel can act as a dispersing or complexing agent for the metal, which forms a new metal-fuel precursor;

- The melting point of the organic fuel should generally be below 250 °C, and its ignition temperature should be below 500 °C;

- The fuel should typically decompose completely, releasing large amounts of gases that improve the textural properties of the catalyst;

- It should be compatible with metal nitrates, i.e., the combustion reaction should be controlled and smooth and should not lead to an explosion;

- It should not produce any residual mass other than the oxide in question;

- Oxides and their mixtures can be prepared at very low temperatures < 400 °C;

- The products are homogeneous and crystalline;

- They are soft in structure with a high surface area;

- The synthesized materials are highly pure (99.99%);

- The particles are less agglomerated and can be used directly for coating;

- Glycine is a relatively inexpensive substance that can be used to prepare a large number of composite materials [103].

2.6. Catalyst Deactivation and Methods of Decrease

2.6.1. Catalyst Deactivation During Dry Reforming of Methane

- Hydrocarbon or carbon monoxide adsorption on the surface;

- Dissociation of carbon monoxide or hydrocarbons to generate adsorbed carbon. Metal is formed at the tips of carbon filaments in the rear interface, where coke diffusion and dissolution occurred [108].

2.6.2. Methods to Decrease Carbon Formation

3. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CB | Carbon Balance |

| CHNS | Carbon, Hydrogen, Nitrogen, and Sulfur Analysis |

| CO2-TPD | Temperature-Programmed Desorption of Carbon Dioxide |

| CCS | Colloidal Combustion Synthesis |

| DFT | Density Functional Theory |

| DRM | Dry Reforming of Methane |

| GC-MS | Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry Analysis |

| GHSV | Gas Hourly Space Velocity |

| BET | Brunauer–Emmett–Teller Method |

| MSI | Metal-Support Interaction |

| NH3-TPD | Temperature-Programmed Desorption of Ammonia |

| PACS | Paper Assisted Combustion Synthesis |

| POM | Partial Oxidation of Methane |

| RWGS | Reverse Water–Gas Shift Reaction |

| SCS | Solution Combustion Synthesis |

| SEM | Scanning Electron Microscopy |

| SHS | Self-Propagation High Temperature Synthesis |

| SRM | Steam Reforming of Methane |

| STY | Space Time Yield |

| TEM | Transmission Electron Microscopy |

| TGA | Thermogravimetric analysis |

| TOS | Time of Stream |

| TPO | Temperature-Programmed Oxidation |

| TPR | Temperature-Programmed Reduction |

References

- Sorrell, S.; Speirs, J.; Bentley, R.; Brandt, A.; Miller, R. Global Oil Depletion: A Review of the Evidence. Energy Policy 2010, 38, 5290–5295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Pan, L.; Ding, Q. Dynamic Analysis of Natural Gas Substitution for Crude Oil: Scenario Simulation and Quantitative Evaluation. Energy 2023, 282, 128764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey, J.R.C.; Longo, A.; Rijo, B.; Pedrero, C.M.; Tarelho, L.A.C.; Brito, P.S.D.; Nobre, C. A Review of Cleaning Technologies for Biomass-Derived Syngas. Fuel 2024, 377, 132776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosravani, H.; Meshksar, M.; Rahimpour, H.R.; Rahimpour, M.R. Chapter 1—Introduction to Syngas Products and Applications. In Advances in Synthesis Gas: Methods, Technologies and Applications; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; Volume 3, pp. 3–25. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, H.; Chen, H.; Zhang, M.; Liang, C.; Duan, L. Recent Advances in Promoting Dry Reforming of Methane Using Nickel-Based Catalysts. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2024, 14, 1712–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussien, A.G.S.; Polychronopoulou, K. A Review on the Different Aspects and Challenges of the Dry Reforming of Methane (DRM) Reaction. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 3400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bera, P. Solution Combustion Synthesis as a Novel Route to Preparation of Catalysts. Int. J. Self-Propagating High-Temp. Synth. 2019, 28, 77–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoda, O.; Xanthopoulou, G.; Vekinis, G.; Chroneos, A. Review of Recent Studies on Solution Combustion Synthesis of Nanostructured Catalysts. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2018, 20, 1800047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SM, N.B.; Rao, M.; Madras, G.; Challapalli, S. Solution Combustion Synthesized Ni-Based Catalysts for Dry Reforming of Methane Reaction Using Dielectric Barrier Discharge Reactor. ChemCatChem 2025, 17, e202500048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurmashov, P.B.; Ukhina, A.V.; Manakhov, A.; Ishchenko, A.V.; Maksimovskii, E.A.; Bannov, A.G. Solution Combustion Synthesis of Ni/Al2O3 Catalyst for Methane Decomposition: Effect of Fuel. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 3962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddique, F.; González-Cortés, S.; Mirzaei, A.; Xiao, T.; Rafiq, M.; Zhang, X. Solution Combustion Synthesis: The Relevant Metrics for Producing Advanced and Nanostructured Photocatalysts. Nanoscale 2022, 14, 11806–11868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sintuya, P.; Charojrochkul, S.; Chanthanumataporn, M.; Wongsakulphasatch, S.; Assabumrungrat, S.; Ratchahat, S. Rapid Fabrication of Ni Supported MgO-ZrO2 Catalysts via Solution Combustion Synthesis for Steam Reforming of Methane for Hydrogen Production. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 86, 58–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Liu, Y.; Pan, Y.; Jin, H. Thermodynamics and Experimental Analysis of Ni-modified Oxygen Carriers with Carbon Resistance for Chemical Looping Dry Reforming of Methane. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 2025, 169, 151118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhumabek, M.; Xanthopoulou, G.; Tungatarova, S.A.; Baizhumanova, T.S.; Vekinis, G.; Murzin, D.Y. Biogas Reforming over Al-Co Catalyst Prepared by Solution Combustion Synthesis Method. Catalysts 2021, 11, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Khader, M.M.; Almarri, M.J.; Abdelmoneim, A.G. Ni-based Nano-catalysts for the Dry Reforming of Methane. Catal. Today 2020, 343, 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, M.G.; Melo, D.M.A.; Medeiros, R.L.B.A.; Maziviero, F.V.; Macedo, H.P.; Oliveira, Â.A.S.; Braga, R.M. NiO–MgAl2O4 Systems for Dry Reforming of Methane: Effect of the Combustion Synthesis Route in the Catalysts Properties. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2022, 278, 125599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crider, J.F. Self-Propagating High Temperature Synthesis—A Soviet Method for Producing Ceramic Materials. In Proceedings of the 6th Annual Conference on Composites and Advanced Ceramic Materials: Ceramic Engineering and Science, Cocoa Beach, FL, USA, 17–21 January 1982; pp. 519–528. [Google Scholar]

- Thiagarajan, S.; Sanmugam, A.; Vikraman, D. Facile Methodology of Sol-Gel Synthesis for Metal Oxide Nanostructures. Recent Appl. Sol-Gel Synth. 2017, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.W.; Riman, R.E.; TenHuisen, K.S.; Brown, K. Mechanochemical-Hydrothermal Synthesis of Hydroxyapatite from Nonionic Surfactant Emulsion Precursors. J. Cryst. Growth 2004, 270, 615–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingsley, J.J.; Patil, K.C. A Novel Combustion Process for the Synthesis of Fine Particle α-Alumina and Related Oxide Materials. Mater. Lett. 1988, 6, 427–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xanthopoulou, G.; Thoda, O.; Roslyakov, S.; Steinman, A.; Kovalev, D.; Levashov, E.; Chroneos, A. Solution Combustion Synthesis of Nano-Catalysts with a Hierarchical Structure. J. Catal. 2018, 364, 112–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odawara, O.; Fujita, T.; Gubarevich, A.V.; Wada, H. Thermite-Related Technologies for Use in Extreme Geothermal Environments. Int. J. Self-Propagating High-Temp. Synth. 2018, 27, 228–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manukyan, K.V.; Cross, A.; Roslyakov, S.; Rouvimov, S.; Rogachev, A.S.; Wolf, E.E.; Mukasyan, A.S. Solution Combustion Synthesis of Nano-Crystalline Metallic Materials: Mechanistic Studies. J. Phys. Chem. C 2013, 117, 24417–24427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukasyan, A.S.; White, J.D.E. Combustion Joining of Refractory Materials. Int. J. Self-Propagating High-Temp. Synth. 2007, 16, 154–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aruna, S.T.; Mukasyan, A.S. Combustion Synthesis and Nanomaterials. Curr. Opin. Solid State Mater. Sci. 2008, 12, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varma, A.; Mukasyan, A.S.; Rogachev, A.S.; Manukyan, K.V. Solution Combustion Synthesis of Nanoscale Materials. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 14493–14586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, W.; Wu, J.M. Nanomaterials via Solution Combustion Synthesis: A Step Nearer to Controllability. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 58090–58100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Cortes, S.L.; Imbert, F.E. Fundamentals, Properties and Applications of Solid Catalysts Prepared by Solution Combustion Synthesis (SCS). Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2013, 452, 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, B.; Wang, Y.; Xu, Z.; Han, W.; Jin, H.; Wang, H. Novel Ways for Hydrogen Production Based on Methane Steam and Dry Reforming Integrated with Carbon Capture. Energy Convers. Manag. 2022, 270, 116199–116215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Sun, Z.; Hu, Y.H. Steam Reforming of Methane: Current States of Catalyst Design and Process Upgrading. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 149, 111330–111354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangadharan, P.; Kanchi, K.C.; Lou, H.H. Evaluation of the Economic and Environmental Impact of Combining Dry Reforming with Steam Reforming of Methane. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2012, 90, 1956–1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsapur, R.K.; Chatterjee, S.; Huang, K.W. The Insignificant Role of Dry Reforming of Methane in CO2 Emission Relief. ACS Energy Lett. 2020, 5, 2881–2885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agún, B.; Abánades, A. Comprehensive Review on Dry Reforming of Methane: Challenges and Potential for Greenhouse Gas Mitigation. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 103, 395–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Khader, M.M. Effects of Support on Ni-based Catalysts for Dry Reforming of Methane. Clean. Chem. Eng. 2025, 11, 100201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, S.; Prasad, R. An Overview on Dry Reforming of Methane: Strategies to Reduce Carbonaceous Deactivation of Catalysts. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 108668–108688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osazuwa, O.U.; Ng, K.H. A Review to Elucidate the Influence of Promoters on the Acidity/Basicity, Reducibility, and Metal-Support Interaction of Catalysts in Methane Dry Reforming. Alex. Eng. J. 2025, 127, 309–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelsadek, Z.; Köten, H.; Gonzalez-Cortes, S.; Cherifi, O.; Halliche, D.; Masset, P.J. Lanthanum-Promoted Nickel-Based Catalysts for the Dry Reforming of Methane at Low Temperatures. Jom 2023, 75, 727–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Muñoz, G.; Alcañiz-Monge, J. Examining the Effect of Zirconium Doping in Lanthanum Nickelate Perovskites on their Performance as Catalysts for Dry Methane Reforming. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 115387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farsi, A.; Mansouri, S.S. Influence of Nanocatalyst on Oxidative Coupling, Steam and Dry Reforming of Methane: A Short Review. Arab. J. Chem. 2016, 9 (Suppl. S1), S28–S34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, R.; Mahinpey, N. A Review on Catalyst Development for Conventional Thermal Dry Reforming of Methane at Low Temperature. Can. J. Chem. Eng. 2023, 101, 3180–3212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabadi, B.A.T.; Eskandari, S.; Khan, U.; White, R.D.; Regalbuto, J.R. Chapter One—A Review of Preparation Methods for Supported Metal Catalysts. Adv. Catal. 2017, 61, 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- Munnik, P.; Jongh, P. ChemInform Abstract: Recent Developments in the Synthesis of Supported Catalysts. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 6687–6718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azeem, S.; Ashraf, M.; Hussain, S. Role of stable Ni Nano Catalysts for Dry Reforming of Methane. Adsorp. Sci. Technol. 2025, 43, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassani Rad, S.J.; Haghighi, M.; Alizadeh Eslami, A.; Rahmani, F.; Rahemi, N. Sol–Gel vs. Impregnation Preparation of MgO and CeO2 Doped Ni/Al2O3 Nanocatalysts Used in Dry Reforming of Methane: Effect of Process Conditions, Synthesis Method and Support Composition. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2016, 41, 5335–5350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubert, U.; Hüsing, N. Synthesis of Inorganic Materials; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2012; 161p. [Google Scholar]

- Hanaor, D.A.H.; Chironi, I.; Karatchevtseva, I.; Triani, G.; Sorrell, C.C. Single and Mixed Phase TiO2 Powders Prepared by Excess Hydrolysis of Titanium Alkoxide. Adv. Appl. Ceram. 2012, 111, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, M.A.; Wani, M.Y.; Hashim, M.A. Microemulsion Method: A Novel Route to Synthesize Organic and Inorganic Nanomaterials. Arab. J. Chem. 2012, 5, 397–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboonasr Shiraz, M.H.; Rezaei, M.; Meshkani, F. Microemulsion Synthesis Method for Preparation of Mesoporous Nanocrystalline γ-Al2O3 Powders as Catalyst Carrier for Nickel Catalyst in Dry Reforming Reaction. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2016, 41, 6353–6361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiraz, M.H.A.; Rezaei, M.; Meshkani, F. Preparation of Nanocrystalline Ni/Al2O3 Catalysts with the Microemulsion Method for Dry Reforming of Methane. Can. J. Chem. Eng. 2016, 94, 1177–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, M.; Daud, W.M.A.W. Microemulsion Based Synthesis of Ni/MgO Catalyst for Dry Reforming of Methane. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 38277–38289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboonasr Shiraz, M.H.; Rezaei, M.; Meshkani, F. Ni Catalysts Supported on Nano-Crystalline Aluminum Oxide Prepared by a Microemulsion Method for Dry Reforming Reaction. Res. Chem. Intermed. 2016, 42, 6627–6642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiraz, M.H.A.; Rezaei, M.; Meshkani, F. The Effect of Promoters on the CO2 Reforming Activity and Coke Formation of Nanocrystalline Ni/Al2O3 Catalysts Prepared by Microemulsion Method. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2016, 33, 3359–3366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, B.; Zhao, L.; Wang, F.; Xu, L.; Yu, H.; Cui, Y.; Zhang, J.; Shi, W. Effect of Calcination Temperature on Performance of Ni@SiO2 Catalyst in Methane Dry Reforming. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2020, 59, 13370–13379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, A.A.; Fakeeha, A.H.; Lanre, M.S.; Al-Awadi, A.S.; Alreshaidan, S.B.; Albaqmaa, Y.A.; Adil, S.F.; Al-Zahrani, A.A.; Abasaeed, A.E.; Al-Fatesh, A.S. The Effect of Calcination Temperature on Various Sources of ZrO2 Supported Ni Catalyst for Dry Reforming of Methane. Catalysts 2022, 12, 361–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, Y.H.; Mohamed, A.T.; Kumar, A.; Al-Qaradawi, S.Y. Solution Combustion Synthesis of Ni/La2O3 for Dry Reforming of Methane: Tuning the Basicity via Alkali and Alkaline Earth Metal Oxide Promoters. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 33734–33743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

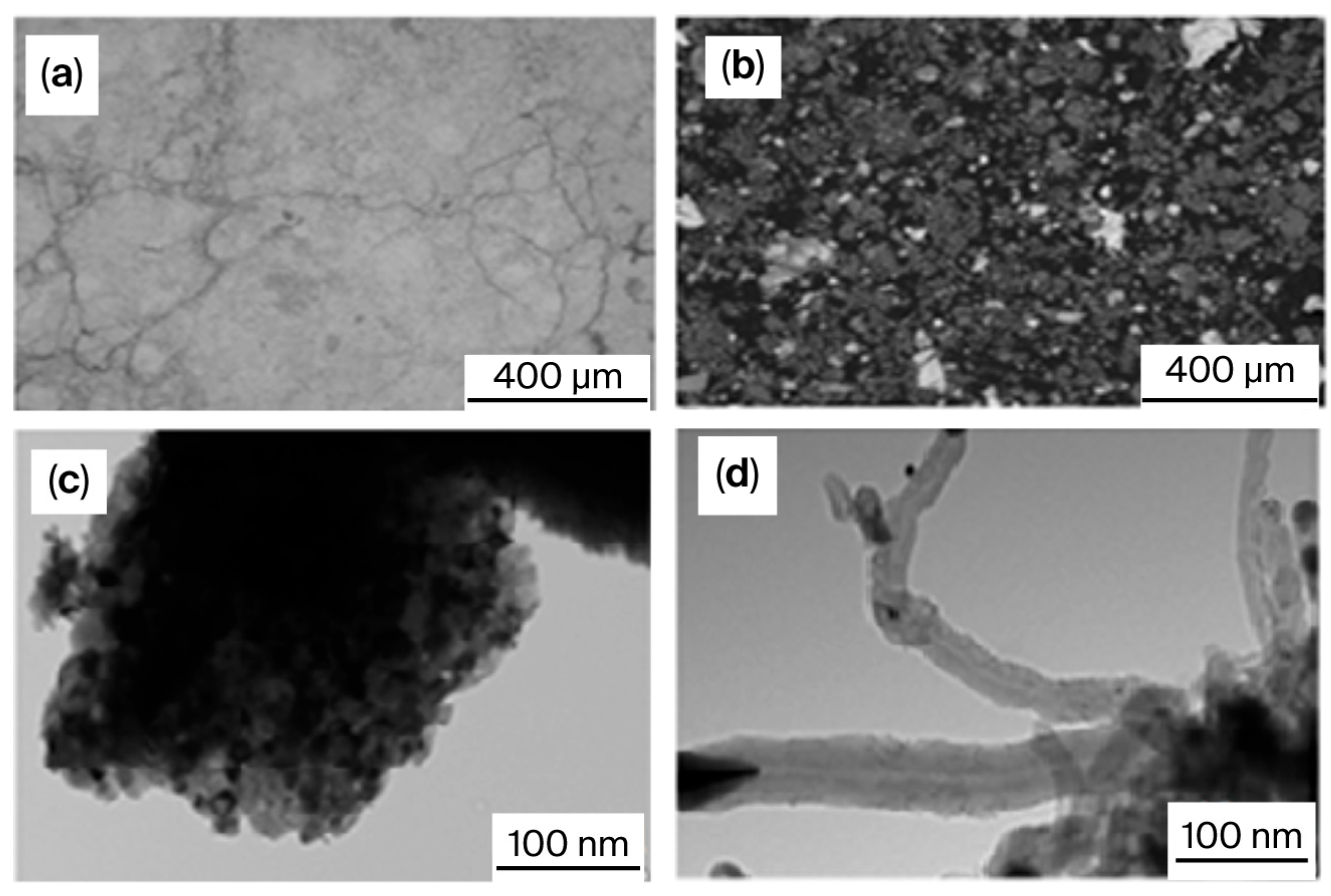

- Danghyan, V.; Kumar, A.; Mukasyan, A.; Wolf, E.E. An Active and Stable NiOMgO Solid Solution Based Catalysts Prepared by Paper Assisted Combustion Synthesis for the Dry Reforming of Methane. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2020, 273, 119056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, A.R.; Asencios, Y.J.O.; Assaf, E.M.; Assaf, J.M. Dry Reforming of Methane on Ni–Mg–Al Nano-Spheroid Oxide Catalysts Prepared by the Sol–Gel Method from Hydrotalcite-Like Precursors. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2013, 280, 876–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, D.; Tian, H.; Zeng, L.; Zhao, Z.J.; Gong, J. Dry Reforming of Methane over Ni/La2O3 Nanorod Catalysts with Stabilized Ni Nanoparticles. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2017, 202, 683–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, M.; Sikander, U.; Mehran, M.T.; Kim, S.H. Exceptional Stability of Hydrotalcite Derived Spinel Mg(Ni)Al2O4 Catalyst for Dry Reforming of Methane. Catal. Today 2022, 403, 74–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, C.; Song, K.; Pan, J.; Huang, M.; Luo, R.; Li, D.; Jiang, L. Ni-Fe/Mg(Al)O Alloy Catalyst for Carbon Dioxide Reforming of Methane: Influence of Reduction Temperature and Ni-Fe Alloying on Coking. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 33574–33585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Araujo, G.C.; de Lima, S.M.; Assaf, J.M.; Peña, M.A.; Fierro, J.L.G.; do Carmo Rangel, M. Catalytic Evaluation of Perovskite-Type Oxide LaNi1-xRuxO3 in Methane Dry Reforming. Catal. Today 2008, 133–135, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutthiumporn, K.; Maneerung, T.; Kathiraser, Y.; Kawi, S. CO2 Dry Reforming of Methane over La0.8Sr0.2Ni0.8M0.2O3 Perovskite (M = Bi, Co, Cr, Cu, Fe): Roles of Lattice Oxygen on C-H Activation and Carbon Suppression. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2012, 37, 11195–11207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhang, R.; Liu, H.; Wei, Q.; Gong, D.; Mo, L.; Tao, H.; Cui, S.; Wang, L. One-Step Synthesis of Highly Dispersed and Stable Ni Nanoparticles Confined by CeO2 on SiO2 for Dry Reforming of Methane. Energies 2020, 13, 5956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manabayeva, A.M.; Mäki-Arvela, P.; Vajglová, Z.; Martinéz-Klimov, M.; Yevdokimova, O.; Peuronen, A.; Lastusaari, M.; Tirri, T.; Tungatarova, S.A.; Baizhumanova, T.S.; et al. Mg-Modified Ni-Based Catalysts Prepared by the Solution Combustion Synthesis for Dry Reforming of Methane. Catal. Today 2025, 453, 115261–115275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dębek, R.; Motak, M.; Duraczyska, D.; Launay, F.; Galvez, M.E.; Grzybek, T.; Da Costa, P. Methane Dry Reforming over Hydrotalcite-Derived Ni-Mg-Al Mixed Oxides: The Influence of Ni Content on Catalytic Activity, Selectivity and Stability. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2016, 6, 6705–6715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.B.; Eissa, A.A.S.; Kim, M.-J.; Goda, E.S.; Youn, J.-R.; Lee, K. Sustainable Synthesis of a Highly Stable and Coke-Free Ni@CeO2 Catalyst for the Efficient Carbon Dioxide Reforming of Methane. Catalysts 2022, 12, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Slater, T.J.A.; Huang, H.; Zhou, Y.; Jiao, Y.; Parlett, C.M.A.; Guan, S.; Chansai, S.; Xu, S.; Wang, X.; et al. Developing Silicalite-1 Encapsulated Ni Nanoparticles as Sintering-/Coking-Resistant Catalysts for Dry Reforming of Methane. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 446, 137439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramezani, Y.; Meshkani, F.; Rezaei, M. Promotional Effect of Mg in Trimetallic Nickel-Manganese-Magnesium Nanocrystalline Catalysts in CO2 Reforming of Methane. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2018, 43, 22347–22356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbour, K.; Saad, A.; Inaty, L.; Davidson, A.; Massiani, P.; El Hassan, N. Ordered Mesoporous Fe-Al2O3 Based-Catalysts Synthesized via a Direct “One-Pot” Method for the Dry Reforming of a Model Biogas Mixture. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 14889–14907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aramouni, N.A.K.; Zeaiter, J.; Kwapinski, W.; Leahy, J.J.; Ahmad, M.N. Trimetallic Ni-Co-Ru Catalyst for the Dry Reforming of Methane: Effect of the Ni/Co Ratio and the Calcination Temperature. Fuel 2021, 300, 120950–120961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Vajglova, Z.; Mäki-Arvela, P.; Peurla, M.; Palonen, H.; Murzin, D.Y.; Tungatarova, S.A.; Baizhumanova, T.S.; Aubakirov, Y.A. Mono- and Bimetallic Ni−Co Catalysts in Dry Reforming of Methane. ChemistrySelect 2021, 6, 3424–3434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araiza, D.G.; Arcos, D.G.; Gómez-Cortés, A.; Díaz, G. Dry Reforming of Methane over Pt-Ni/CeO2 Catalysts: Effect of the Metal Composition on the Stability. Catal. Today 2021, 360, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, J.; Wang, Y.; Liland, S.E.; Regli, S.K.; Yang, J.; Rout, K.R.; Luo, J.; Rønning, M.; Ran, J.; Chen, D. Unraveling Enhanced Activity; Selectivity; and Coke Resistance of Pt–Ni Bimetallic Clusters in Dry Reforming. ACS Catal. 2021, 11, 2398–2411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, N.F.P.; Neto, R.C.R.; Moya, S.F.; Souza, M.M.V.M.; Schmal, M. Synthesis of NiAl2O4 with High Surface Area as Precursor of Ni Nanoparticles for Hydrogen Production. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2010, 35, 11725–11732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Luo, Y.; Li, B.; Yuan, X.; Wang, X. Catalytic Performance of Iron-Promoted Nickel-Based Ordered Mesoporous Alumina FeNiAl Catalysts in Dry Reforming of Methane. Fuel Process. Technol. 2019, 193, 348–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mubaddel, F.S.; Kumar, R.; Sofiu, M.L.; Frusteri, F.; Ibrahim, A.A.; Srivastava, V.K.; Kasim, S.O.; Fakeeha, A.H.; Abasaeed, A.E.; Osman, A.I.; et al. Optimizing Acido-Basic Profile of Support in Ni Supported La2O3-Al2O3 Catalyst for Dry Reforming of Methane. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 14225–14235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallego, G.S.; Batiot-Dupeyrat, C.; Barrault, J.; Florez, E.; Mondragón, F. Dry Reforming of Methane over LaNi1-yByO3±δ (B = Mg, Co) Perovskites Used as Catalyst Precursor. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2008, 334, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivas, M.E.; Fierro, J.L.G.; Goldwasser, M.R.; Pietri, E.; Pérez-Zurita, M.J.; Griboval-Constant, A.; Leclercq, G. Structural Features and Performance of LaNi1-xRhxO3 System for the Dry Reforming of Methane. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2008, 344, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurav, H.R.; Bobade, R.; Das, V.L.; Chilukuri, S. Carbon Dioxide Reforming of Methane over Ruthenium Substituted Strontium Titanate Perovskite Catalysts. Indian J. Chem. 2012, 51A, 1339–1347. [Google Scholar]

- Dama, S.; Ghodke, S.R.; Bobade, R.; Gurav, H.R.; Chilukuri, S. Active and Durable Alkaline Earth Metal Substituted Perovskite Catalysts for Dry Reforming of Methane. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2018, 224, 146–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Córdoba, M.; Choya, A.; de Rivas, B.; Gutiérrez-Ortiz, J.I.; López-Fonseca, R. Dry Reforming of Methane over Nickel Aluminate-Derived Catalysts Modified with Lanthanum and Magnesium. Catal. Today 2025, 460, 115483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choya, A.; Gil-Barbarin, A.; de Rivas, B.; Gutiérrez-Ortiz, J.I.; López-Fonseca, R. Mixed Ni-Co Sub-Stoichiometric Spinels as Catalytic Precursors for Dry Reforming of Methane. J. CO2 Util. 2025, 99, 103166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

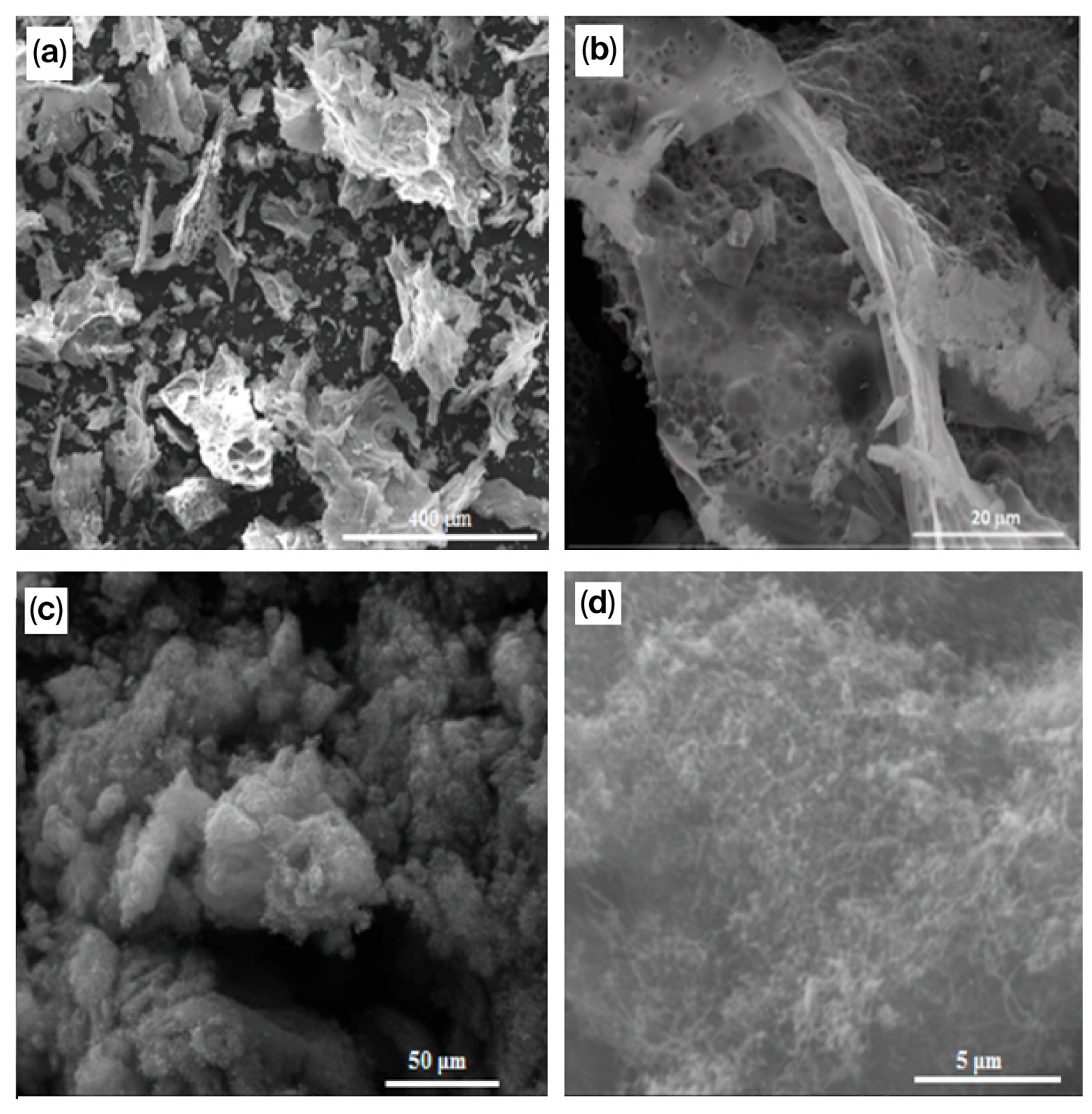

- Xanthopoulou, G.; Thoda, O.; Boukos, N.; Krishnamurthy, S.; Dey, A.; Roslyakov, S.; Vekinis, G.; Chroneos, A.; Levashov, E. Effects of Precursor Concentration in Solvent and Nanomaterials Room Temperature Aging on the Growth Morphology and Surface Characteristics of Ni–NiO Nanocatalysts Produced by Dendrites Combustion during SCS. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 4925–4945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manukyan, K.V. Solution Combustion Synthesis of Catalysts. In Concise Encyclopedia of Self-Propagating High-Temperature Synthesis; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 347–348. [Google Scholar]

- Novitskaya, E.; Kelly, J.P.; Bhaduri, S.; Graeve, O.A. A Review of Solution Combustion Synthesis: An Analysis of Parameters Controlling Powder Characteristics. Int. Mater. Rev. 2020, 66, 188–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandana, B.; Dedhila, D.; Baiju, V.; Sajeevkumar, G. NiAl2O4 Nanocomposite via Combustion Synthesis for Sustainable Environmental Remediation. Nanosistemi Nanomater. Nanotehnologii 2022, 20, 459–472. [Google Scholar]

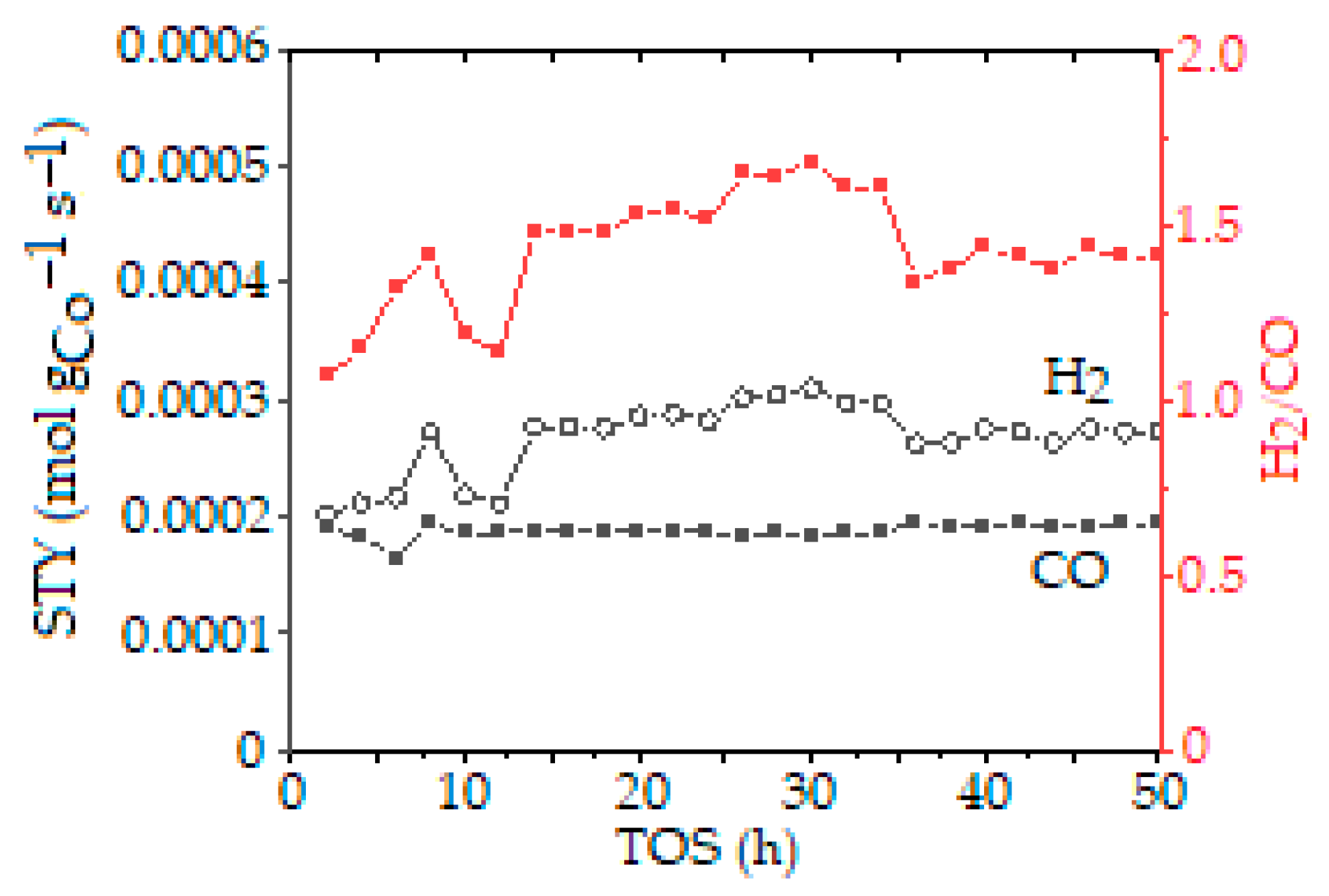

- Manabayeva, A.M.; Mäki-Arvela, P.; Vajglová, Z.; Martinez-Klimov, M.; Tirri, T.; Baizhumanova, T.S.; Grigor’eva, V.P.; Zhumabek, M.; Aubakirov, Y.A.; Simakova, I.; et al. Dry Reforming of Methane over Ni-Fe-Al Catalysts Prepared by Solution Combustion Synthesis. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2023, 62, 11439–11455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choya, A.; de Rivas, B.; No, M.L.; Gutiérrez-Ortiz, J.I.; López-Fonseca, R. Dry Reforming of Methane over Sub-Stoichiometric NiAl2O4-Mediated Ni/Al2O3 Catalysts. Fuel 2024, 358 Pt A, 130166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voskanyan, A.; Chan, K.-Y.; Li, C.Y.V. Colloidal Solution Combustion Synthesis: Towards Mass Production of Crystalline Uniform Mesoporous CeO2 Catalyst with Tunable Porosity. Chem. Mater. 2016, 28, 2768–2775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukasyan, A.S.; Rogachev, A.S.; Aruna, S.T. Combustion Synthesis in Nanostructured Reactive Systems. Adv. Powder Technol. 2015, 26, 954–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherikar, B.N.; Sahoo, B.; Umarji, A.M. Effect of Fuel and Fuel to Oxidizer Ratio in Solution Combustion Synthesis of Nanoceramic Powders: MgO, CaO and ZnO. Solid State Sci. 2020, 109, 106426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, K.C.; Aruna, S.T.; Mimani, T. Combustion Synthesis: An Update. Curr. Opin. Solid State Mater. Sci. 2002, 6, 507–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinson, K.; Belyak, V.; Sakhno, D.; Kiryanov, N.; Chebanenko, M.; Popkov, V. Effect of Fuel Type on Solution Combustion Synthesis and Photocatalytic Activity of NiFe2O4 Nanopowders. Nanosyst. Phys. Chem. Math. 2021, 12, 792–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukasyan, A.S.; Dinka, P. Novel Approaches to Solution-Combustion Synthesis of Nanomaterials. Int. J. Self-Propagating High-Temp. Synth. 2007, 16, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, K.C.; Aruna, S.T.; Ekambaram, S. Combustion Synthesis. Curr. Opin. Solid State Mater. Sci. 1997, 2, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, K.C.; Hegde, M.S.; Rattan, T.; Aruna, S.T. Chemistry of Nanocrystalline Oxide Materials Combustion Synthesis Properties and Applications; World Scientific: Singapore, 2008; p. 362. [Google Scholar]

- Deganello, F. Nanomaterials for Environmental and Energy Applications Prepared by Solution Combustion Based-Methodologies: Role of the Fuel. Mater. Today Proc. 2017, 4, 5507–5516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuravlev, V.D.; Bamburov, V.G.; Beketov, A.R.; Perelyaeva, L.A.; Baklanova, I.V.; Sivtsova, O.V.; Grigorov, I.G. Solution Combustion Synthesis of α-Al2O3 Using Urea. Ceram. Int. 2013, 39, 1379–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Modi, O.P.; Gupta, G.K. Combustion Synthesis of Nanocrystalline Al2O3 Powder Using Aluminium Nitrate and Urea as Reactants—Influence of Reactant Composition. Adv. Appl. Sci. Res. 2012, 3, 3819–3824. [Google Scholar]

- Roslyakov, S.; Kovalev, D.; Rogachev, A.; Manukyan, K.; Mukasyan, A. Solution Combustion Synthesis: Dynamics of Phase Formation for Highly Porous Nickel. Dokl. Phys. Chem. 2013, 449, 48–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, F.C.; Tian, Z.Q.; Zhang, F.; Tian, C.C.; Huang, W.J. Combustion Synthesis of Nanocrystalline Al2O3 Powders Using Urea as Fuel: Influence of Different Combustion Aids. Key Eng. Mater. 2010, 434–435, 868–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadke, S.; Kalimila, M.T.; Rathkanthiwar, S.; Gour, S.; Sonkusare, R.; Ballal, A. Role of Fuel and Fuel-to-Oxidizer Ratio in Combustion Synthesis of Nano-Crystalline Nickel Oxide Powders. Ceram. Int. 2015, 41, 14949–14957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mimani, T.; Patil, K.C. Solution Combustion Synthesis of Nanoscale Oxides and Their Composites. Mater. Phys. Mech. 2001, 4, 134–137. [Google Scholar]

- Sherikar, B.N.; Umarji, A.M. Synthesis of γ-Alumina by Solution Combustion Method Using Mixed Fuel Approach (Urea + Glycine Fuel). Int. J. Res. Eng. Technol. 2013, 5, 434–438. [Google Scholar]

- Padayatchee, S.; Ibrahim, H.; Friedrich, H.B.; Olivier, E.J.; Ntola, P. Solution Combustion Synthesis for Various Applications: A Review of the Mixed-Fuel Approach. Fluids 2025, 10, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

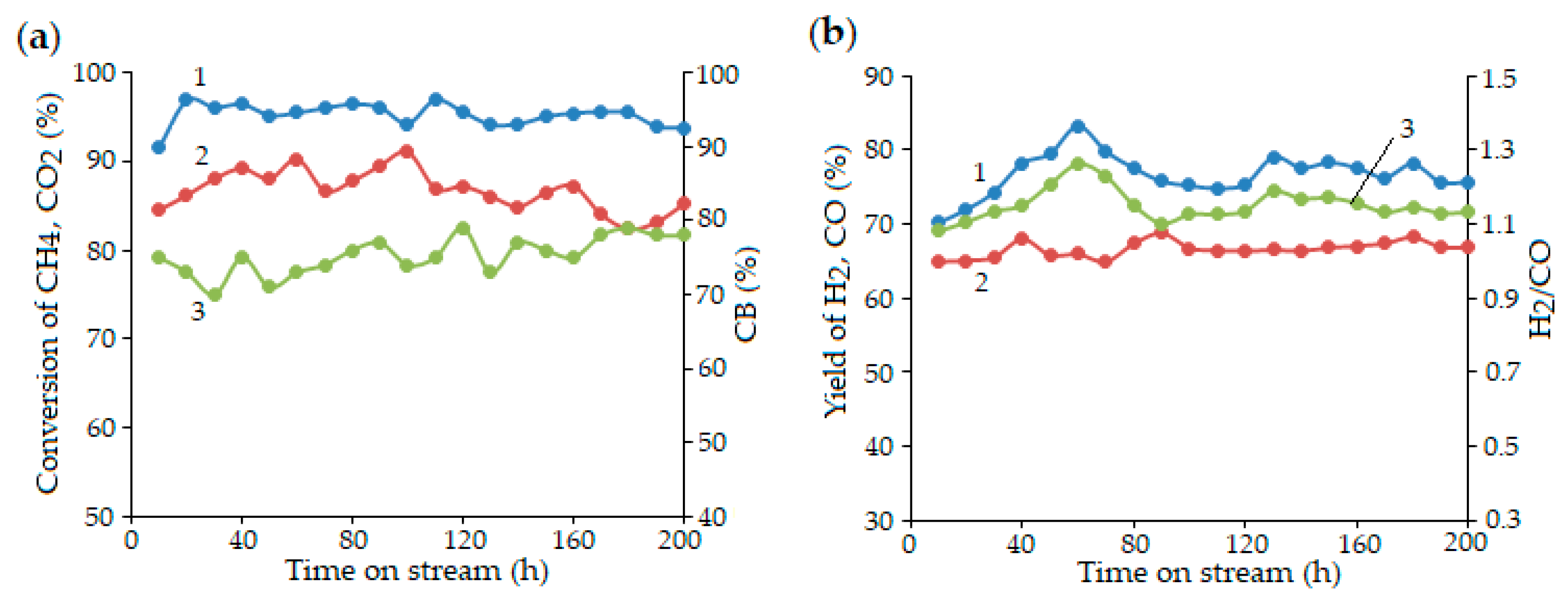

- Xanthopoulou, G.; Karanasios, K.; Tungatarova, S.; Baizhumanova, T.; Zhumabek, M.; Kaumenova, G.; Massalimova, B.; Shorayeva, K. Catalytic Methane Rreforming into Synthesis Gas over Developed Composite Materials Prepared by Combustion Synthesis. React. Kinet. Mech. Catal. 2019, 126, 645–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhumabek, M.; Kaumenova, G.; Augaliev, D.; Alaidar, Y.; Murzin, D.; Tungatarova, S.; Xanthopoulou, G.; Kotov, S.; Baizhumanova, T. Selective Catalytic Reforming of Methane into Synthesis Gas. Chem. Eng. Technol. 2021, 44, 2026–2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval-Diaz, L.E.; Shlögl, R.; Lunkenbein, T. Quo Vadis Dry Reforming of Methane?—A Review on Its Chemical, Environmental, and Industrial Prospects. Catalysts 2022, 12, 465–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manabayeva, A.M.; Mäki-Arvela, P.; Vajglová, Z.; Martinéz-Klimov, M.; Yevdokimova, O.; Peuronen, A.; Lastusaari, M.; Tirri, T.; Kassymkan, K.; Baizhumanova, T.S.; et al. Dry Reforming of Methane over Rare-Earth Metal Oxide Ni-M-Al (M = Ce, La) Catalysts. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2023, 62, 20588–20607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manabayeva, A.M.; Mäki-Arvela, P.; Vajglová, Z.; Martinez-Klimov, M.; Yevdokimova, O.; Peuronen, A.; Lastusaari, M.; Tirri, T.; Baizhumanova, T.S.; Kassymkan, K.; et al. Dry Reforming of Methane over Mn-Modified Ni-Based Catalysts. Catal. Lett. 2024, 154, 4780–4794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooqi, A.S.; Yusuf, M.; Zabidi, N.A.M.; Saidur, R.; Sanaullah, K.; Farooqi, A.S.; Khan, A.; Abdullah, B. A Comprehensive Review on Improving the Production of Rich-Hydrogen via Combined Steam and CO2 Reforming of Methane over Ni-Based Catalysts. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 31024–31040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoganbek, D.; Martinez-Klimov, M.; Yevdokimova, O.; Peuronen, A.; Lastusaari, M.; Aho, A.; Tungatarova, S.A.; Baizhumanova, T.S.; Zhumadullaev, D.A.; Zhumabek, M.; et al. Dry Methane Reforming over Lanthanide-Doped Co–Al Catalysts Prepared via a Solution Combustion Method. Mater. Adv. 2025, 6, 1173–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Costa, S.K.; Summa, P.; Gopakumar, J.; Valen, Y.; Rønning, M. Excess-Methane CO2 Reforming over Reduced KIT-6-Ni-Y Mesoporous Silicas Monitored by In Situ XAS–XRD. Energy Fuels 2023, 37, 18952–18967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Nie, Z.; Yu, Y. The Carbon Deposition Process on NiFe Catalyst in CO Methanation: A Combined DFT and KMC Study. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2024, 655, 159527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, W.; Wang, L.; Dai, Z.; Yao, L.; Yang, L.; Jiang, W. The Mitigation of Carbon Deposition for Ni-Based Catalyst in CO2 Reforming of Methane: A Combined Experimental and DFT Study. Carbon Capture Sci. Technol. 2024, 13, 100286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Li, L.; Wei, N.; Li, J.; Basset, J.M. Effect of NiAl2O4 Formation on Ni/Al2O3 Stability during Dry Reforming of Methane. ChemCatChem 2015, 7, 2508–2516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagódka, P.; Matus, K.; Sobota, M.; Łamacz, A. Dry Reforming of Methane over Carbon Fibre-Supported CeZrO2, Ni-CeZrO2, Pt-CeZrO2 and Pt-Ni-CeZrO2 Catalysts. Catalysts 2021, 11, 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Ying, M.; Yu, J.; Zhan, W.; Wang, L.; Guo, Y.; Guo, Y. NixAl1O2-δ Mesoporous Catalysts for Dry Reforming of Methane: The Special Role of NiAl2O4 Spinel Phase and its Reaction Mechanism. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2021, 291, 120074–120091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benrabaa, R.; Löfberg, A.; Rubbens, A.; Bordes-Richard, E.; Vannier, R.N.; Barama, A. Structure, Reactivity and Catalytic Properties of Nanoparticles of Nickel Ferrite in the Dry Reforming of Methane. Catal. Today 2013, 203, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, T.; Ye, M.; Liu, Z. Regeneration of Catalysts Deactivated by Coke Deposition: A Review. Chin. J. Catal. 2020, 41, 1048–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieck, C.L.; Vera, C.R.; Querini, C.A.; Parera, J.M. Differences in Coke Burning-off from Pt–Sn/Al2O3 Catalyst with Oxygen or Ozone. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2005, 278, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnoux, P.; Guisnet, M. Coking, Ageing and Regeneration of Zeolites: VI. Comparison of the Rates of Coke Oxidation of HY, H-Mordenite and HZSM-5. Appl. Catal. 1988, 38, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copperthwaite, R.G.; Hutchings, G.J.; Johnston, P.; Orchard, S.W. Regeneration of Pentasil Zeolite Catalysts Using Ozone and Oxygen. J. Chem. Soc. Faraday Trans. 1 Phys. Chem. Condens. Phases 1986, 82, 1007–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, G.; Wang, G.; Xu, C.; Gao, J. Coproduction of Syngas during Regeneration of Coked Catalyst for Upgrading Heavy Petroleum Feeds. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2013, 52, 16737–16744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bednarczuk, L.; Ramírez de la Piscina, P.; Homs, N. Efficient CO2-Regeneration of Ni/Y2O3-La2O3-ZrO2 Systems Used in the Ethanol Steam Reforming for Hydrogen Production. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2016, 41, 19509–19517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rego de Vasconcelos, B.; Pham Minh, D.; Sharrock, P.; Nzihou, A. Regeneration Study of Ni/Hydroxyapatite Spent Catalyst from Dry Reforming. Catal. Today 2018, 310, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, B.; Shang, Z.; Li, S.; Jiang, Y.; Gu, X.; Liang, X. Reforming of Methane with Carbon Dioxide over Cerium Oxide Promoted Nickel Nanoparticles Deposited on 4-Channel Hollow Fibers by Atomic Layer Deposition. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2020, 10, 3212–3222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhi, Y.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, T.; Ye, M.; Liu, Z. Partial Regeneration of the Spent SAPO-34 Catalyst in the Methanol-to-Olefins Process via Steam Gasification. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2018, 57, 17338–17347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yu, D.; Li, W.; Wang, Y.; Gao, S.; Xu, G. Fundamentals of Petroleum Residue Cracking Gasification for Coproduction of Oil and Syngas. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2012, 51, 15032–15040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benamar, A.; Bechket, Z.; Boucheffa, Y.; Miloudi, A. Transformation of m-Xylene over an USHY Zeolite: Deactivation and Regeneration. Comptes Rendus Chim. 2009, 12, 706–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Luo, J.; Cao, M.; Zheng, P.; Li, G.; Bu, J.; Cao, Z.; Chen, S.; Xie, X. A Comparative Study on Different Regeneration Processes of Pt-Sn/γ-Al2O3 Catalysts for Propane Dehydrogenation. J. Energy Chem. 2018, 27, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Entry | Catalyst | Synthesis Method and Conditions | DRM Conditions | Initial Conversion of CH4/CO2 (%) H2/CO | Final Conversion of CH4/CO2 (%) H2/CO | Surface Area (m2·g−1) dfresh (nm) | TOS (h) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ni-La2O3 | SCS; glycine as fuel; calcination at 550 °C for 2 h | CH4/CO2 = 1; T = 700 °C; 30 l·gcat−1·h−1 | 7/20 0.1 | 60/70 0.75 | 37.3 10.3 | 100 | [55] |

| 2 | Mg-Ni-La2O3 | SCS; glycine as fuel; calcination at 550 °C for 2 h | CH4/CO2 = 1; T = 700 °C; 30 l·gcat−1·h−1 | 19/31 0.5 | 80/90 0.9 | 54.5 14.8 | 100 | [55] |

| 3 | 10NiOMgO | PACS; glycine as fuel; pre-ignition at 200 °C | CH4/CO2 = 1; T = 600 °C; 72 l·gcat−1·h−1 | 83/95 n.a. | 79/94 n.a | 163 10 | 25 | [56] |

| 4 | 15 wt.% Ni/Mg-Al | Sol–gel; calcination at 650 °C for 5 h | CH4/CO2 = 1.4; T = 800 °C; 34 l·gcat−1·h−1 | 95/97 n.a. | 95/97 n.a. | 184 5 | 8 | [57] |

| 5 | Ni-Al2O3-CeO2 | Sequential impregnation; calcination at 500 °C for 2 h | CH4/CO2 = 1; T = 850 °C; 24 l·gcat−1·h−1 | 84/87 0.6 | 75/80 0.6 | 65 44 | 24 | [44] |

| 6 | Ni-CeO2/SiO2(CSC) | Colloidal solution combustion; glycine as fuel; calcination at 600 °C for 4 h | CH4/CO2 = 1; P = 0.1 MPa; T = 700 °C; 120 l·gcat−1·h−1 | 75/85 1.0 | 77/85 1.0 | 63.5 n.a. | 20 | [63] |

| 7 | 15Ni-15Mg-20Al | SCS; urea as fuel; pre-ignition at 500 °C | 850 °C; CH4/CO2 = 1; 3 l·gcat−1·h−1 | 90/84 1.1 | 92/81 1.2 | 10 16 | 200 | [64] |

| 8 | 25Ni-MgAl2O4 | Co-precipitation; calcination at 550 °C for 4 h | 750 °C; CH4:CO2:Ar = 1:1:8; GHSV = 20,000 h−1 | 90/92 1.0 | 90/92 1.0 | 115 n.a. | 24 | [65] |

| 9 | 12.5 wt.% Ni/CeO2 | One-pot method; calcination at 400 °C for 4 h | 800 °C; CH4:CO2:Ar = 1:1:1; GHSV = 24 l·gcat−1·h−1 | 90/100 0.9 | 90/95 0.9 | 66.9 n.a. | 50 | [66] |

| 10 | 5Ni/SiO2-S1 | Seed-directed synthesis; 150 °C for 24 h in autoclave | 700 °C; CH4:CO2:Ar = 1:1:2; GHSV = 750 l·gcat−1·h−1 | 74/85 0.8 | 71/80 0.8 | 401 2.9 | 28 | [67] |

| 11 | 5Ni/La2O3-LOC | wet impregnation; calcination at 600 °C for 2 h | 700 °C; CH4:CO2:N2 = 15:15:70; GHSV = 60 l·gcat−1·h−1 | 74/82 0.9 | 70/75 0.9 | 23 13.8 | 50 | [58] |

| 12 | 10Ni3Mn4Mg/Al2O3 | Impregnation; calcination at 500 °C for 4 h | 700 °C; CH4:CO2 = 1:1; GHSV = 12 l·gcat−1·h−1 | 65/70 n.a. | 65/70 n.a. | 166 n.a. | 20 | [68] |

| 13 | Fe5%Ni5%Al2O3 | Evaporation-induced self-assembly; calcination at 600 °C for 5 h | 700 °C; CH4:CO2:Ar = 1.8:1:14; GHSV = 36 l·gcat−1·h−1 | 60/90 1.0 | 50/90 1.0 | 198 n.a. | 13 | [69] |

| 14 | 10Ni-5Co-0.25Ru/MgO-Al2O3 | Two-solvent impregnation; calcination at 750 °C for 2 h | 800 °C; CH4:CO2 = 1:1; GHSV = 1.1·10−2 l·gcat−1·h−1 | 100/94 n.a. | 93/93 n.a. | 242 n.a. | 24 | [70] |

| 15 | 5% Ni- 5% Co/θ-Al2O3 | Wet impregnation; calcination at 500 °C for 2 h | 700 °C; CH4:CO2 = 1:1; GHSV = 4.3·103 l·gcat−1·h−1 | 75/82 1.3 | 49/52 1.3 | 76 22 | 12 | [71] |

| 16 | Pt/Ce | Wet impregnation; calcination at 500 °C for 2 h | 650 °C; CH4:CO2:N2 = 1:1; GHSV = 36.7 l·gcat−1·h−1 | 43/40 0.6 | 49/45 0.6 | 67 3.3 | 24 | [72] |

| 17 | 1.0-Pt-12Ni/Mg-Al | Impregnation; calcination at 600 °C for 6 h | 700 °C; CH4:CO2:Ar = 2:2:1; GHSV = 180 l·gcat−1·h−1 | n.a./62 n.a. | n.a./58 n.a. | 8.8 0.4 | 30 | [73] |

| 18 | NiAl2:1 | Combustion; urea as fuel; pre-ignition at 600 °C; calcination at 700 °C for 3 h | 800 °C; CH4:CO2:He = 1:1:8; GHSV = 240 l·gcat−1·h−1 | 98/n.a. 1.1 | 99/n.a. 1.1 | <10 n.a. | 50 | [74] |

| 19 | 0.5Ni-Fe-Al | “one-pot” evaporation-induced self-assembly; calcination at 750 °C for 5 h | 700 °C CH4:CO2 = 1:1; GHSV = 24 l·g−1·h−1 | 60/68 0.9 | 56/61 0.8 | 86 7 | 7 | [75] |

| 20 | Ni-Mg/Al2O3 (MNA-2.0) | Co-precipitation; calcination at 850 °C for 6 h | 850 °C CH4:CO2:N2 = 10:20:20 sccm.; | 90/98 1.4 | 90/98 1.4 | 100 13.1 | 200 | [59] |

| 21 | Ni-Fe/Mg(Al)O | Co-precipitation; calcination at 800 °C for 5 h | CH4:CO2:N2 = 1:1:2; 500–800 °C; GHSV = 60 l·g−1·h−1 | 90/99 1.2 | n.a. | 153 14.5 | 200 | [60] |

| 22 | Ni-La/Al2O3 | Wet impregnation; calcination at 700 °C for 3 h | CH4:CO2:N2 = 1:1:0.3; 700 °C; GHSV = 42 l·g−1·h−1 | 64/79 1.0 | 63/78 1.0 | 162 14 | 8 | [76] |

| 23 | LaNi0.9Mg0.1AlO3-δ | Auto-combustion; calcination at 700 °C for 6–10 h | 800 °C; CH4:CO2 = 1:1; GHSV = 600 l·gcat−1·h−1 | 0/0 0 | 56/67 0.47 | 10 n.a. | 15 | [77] |

| 24 | LaNi0.95Rh0.05O3 | Co-precipitation; calcination at 750 °C for 5 h | 550 °C; CH4:CO2:Ar = 1:1:8; GHSV = 20,000 h−1 | 29/35 0.9 | 45/45 0.9 | 8 15 | 25 | [78] |

| 25 | LaNi0.9Ru0.1O3 | Thermal decomposition of citrate precursors; calcination at 1000 °C for 4 h | 750 °C; CH4:CO2 = 1:1; GHSV = 72 l·gcat−1·h−1 | 10/10 0.1 | 85/87 0.7 | 1.9 n.a. | 14 | [61] |

| 26 | La0.8Sr0.2Ni0.8Fe0.2O3 | Sol–gel; calcination at 700 °C for 5 h | 700 °C; CH4:CO2:N2 = 1:1:1 | 41/59 n.a. | 81/79 n.a. | 13.9 16 | 24 | [62] |

| 27 | SrTi0.85Ru0.15O3 | Sol–gel; calcination at 750 °C | 900 °C; CH4:CO2:N2 = 1:1:1; GHSV = 28.8 h−1 | 93/96 1.0 | 93/96 1.0 | 17 n.a. | 100 | [79] |

| 28 | CaZr0.8Ni0.2O3-δ | Sol–gel; calcination at 750 °C for 6 h | 800 °C; CH4:CO2:N2 = 1:1:1; GHSV = 28.8·h−1 | 95/96 1.0 | 95/96 1.0 | 13.2 n.a. | 500 | [80] |

| 29 | LaNiAl | Co-precipitation; calcination at 850 °C for 4 h | 650 °C; CH4:CO2:N2 = 1:1:8; GHSV = 90 l·gcat−1·h−1 | 50/50 0.9 | 50/50 0.9 | 72 18 | 24 | [81] |

| 30 | Ni-Co(0.15) | Co-precipitation; calcination at 850 °C for 4 h | 650 °C, CH4:CO2:N2 = 1:1:8, GHSV = 90 l·gcat−1·h−1 | 89/n.a. 1.0 | 85/n.a. 1.0 | 80 20 | 200 | [82] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tungatarova, S.A.; Manabayeva, A.M.; Abilmagzhanov, A.Z.; Baizhumanova, T.S.; Malgazhdarova, M.K. Application of Catalysts Prepared by Solution Combustion Synthesis in Dry Reforming of Methane. Molecules 2025, 30, 4575. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234575

Tungatarova SA, Manabayeva AM, Abilmagzhanov AZ, Baizhumanova TS, Malgazhdarova MK. Application of Catalysts Prepared by Solution Combustion Synthesis in Dry Reforming of Methane. Molecules. 2025; 30(23):4575. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234575

Chicago/Turabian StyleTungatarova, Svetlana A., Alua M. Manabayeva, Arlan Z. Abilmagzhanov, Tolkyn S. Baizhumanova, and Makpal K. Malgazhdarova. 2025. "Application of Catalysts Prepared by Solution Combustion Synthesis in Dry Reforming of Methane" Molecules 30, no. 23: 4575. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234575

APA StyleTungatarova, S. A., Manabayeva, A. M., Abilmagzhanov, A. Z., Baizhumanova, T. S., & Malgazhdarova, M. K. (2025). Application of Catalysts Prepared by Solution Combustion Synthesis in Dry Reforming of Methane. Molecules, 30(23), 4575. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234575