Abstract

The development of highly sensitive gas sensors for toxic industrial gases (TIGs) is paramount for environmental monitoring and public safety. Here, the first-principles calculations were employed to systematically investigate the potential of Pt- and Rh-decorated InS (Pt-InS and Rh-InS) monolayers as advanced gas sensing materials for the five TIGs (SO2, NH3, NO, CO, and NO2). The results reveal that Pt and Rh atoms can be stably anchored at the InS monolayer, inducing significant modulation of its electronic properties. The Pt-InS system exhibits strong chemisorption of NH3 and CO, while the other TIGs interact via physisorption. In contrast, the Rh-InS monolayer demonstrates strong chemisorption and distinct electronic responses to all five gases, driven by robust hybridization between the Rh-d and TIG-p orbitals. Based on comprehensive analyses of sensitivity and recovery time, Rh-InS is identified as a theoretically promising candidate for a reusable SO2 sensor at room temperature, boasting a calculated rapid theoretical recovery time of 2.20 s. The Pt-InS system, conversely, shows potential for high-temperature NH3 sensing. Our findings highlight the exceptional and tunable gas sensing capabilities of Pt- and Rh-decorated InS monolayers, offering a theoretical foundation for designing InS-based sensing devices.

1. Introduction

The accelerating pace of global industrialization has led to a significant increase in the emission of toxic industrial gases, including SO2, NOx, NH3, and CO, from manufacturing processes and fossil fuel combustion [1,2]. These emissions pose a severe threat to both environmental integrity and human health [3,4,5]. As primary contributors to acid rain, photochemical smog, and the greenhouse effect, TIGs can also inflict irreversible damage on the respiratory, nervous, and cardiovascular systems, even at low concentrations [6]. Consequently, it is necessary to develop advanced gas sensors for the real-time, highly sensitive, and repeatable TIG detection [7,8]. Although conventional semiconductor metal oxide (MOS) gas sensors based on materials like SnO2 and ZnO are widely used, their practical application is limited by high operating temperatures (typically > 200 °C) [9,10]. This requirement leads to substantial energy consumption and often compromises sensitivity. To overcome these limitations, research has shifted towards two-dimensional (2D) materials [11,12]. Since the discovery of graphene, 2D materials have been identified as ideal platforms for developing next-generation, high-performance gas sensors due to their unique properties, such as atomic-scale thickness, exceptionally high specific surface area, abundant surface-active sites, and highly tunable electronic characteristics [13,14].

Recently, the InS monolayer, a member of the transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDCs) family [15,16], has garnered considerable attention in the fields of spintronics [17], photocatalysis [18], and gas sensors [19], owing to its moderate band gap, excellent chemical stability, and unique electronic structure [20,21,22,23,24]. For example, Politano et al. [19] employed density functional theory (DFT) calculations in combination with experimental techniques to demonstrate that InS nanosheets exhibit outstanding sensing performance for NO2, achieving a detection limit as low as 180 ppb at an operating temperature of 350 °C. Nevertheless, the adsorption and sensing mechanisms of NO2 on InS monolayer at the atomic scale remain elusive, and the relatively weak adsorption strength poses a significant challenge for practical applications. To address this limitation, surface functionalization via decoration with noble metals (e.g., Pt, Pd, Au, and Rh) has emerged as an effective strategy for enhancing the performance of 2D materials such as MoS2 [25], WSe2 [26], and ZrSSe [27]. While studies on various functionalized TMDCs exist, a systematic understanding of how different noble metals influence the sensing properties of the unique InS monolayer is still lacking. Pt and Rh are particularly interesting due to their renowned catalytic activity and strong interactions with small molecules [28,29]. However, a direct comparison of their effects on a single substrate for a broad range of TIGs has not been thoroughly investigated. Therefore, the integration of Pt and Rh with InS monolayers for the systematic detection of TIGs remains a critical and unexplored area. Furthermore, the underlying physicochemical mechanisms governing such hybrid systems have not yet been elucidated.

Herein, first-principles calculations were conducted to systematically evaluate and compare the gas-sensing performance of Pt- and Rh-decorated InS monolayers (Pt-InS and Rh-InS) toward five TIGs (SO2, NH3, NO, CO, and NO2). Both Pt and Rh atoms are found to anchor strongly to the InS monolayer, leading to substantial modulation of its electronic structure. The adsorption of each gas on Pt-InS and Rh-InS is then examined in detail through the analyses of adsorption energies, charge transfer, projected density of states, and charge density difference, which aims to elucidate the underlying interaction mechanisms between the TIGs and the doped InS monolayers. Furthermore, the sensitivity and recyclability of Pt-InS and Rh-InS monolayers to the TIGs are assessed by analyzing the variations in band gap and work function, as well as the estimated recovery times. This study not only underscores the remarkable potential of Pt-InS and Rh-InS monolayers for TIG detection but also provides a theoretical framework for the rational design of high-performance InS-based gas sensors.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Structural and Electronic Properties of Pt-InS and Rh-InS Monolayers

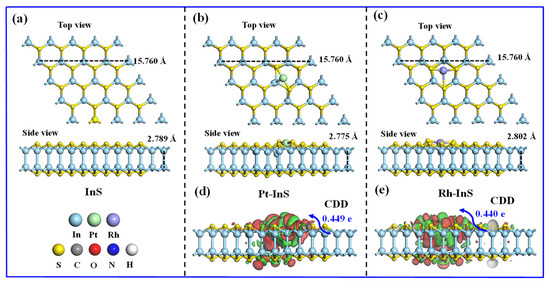

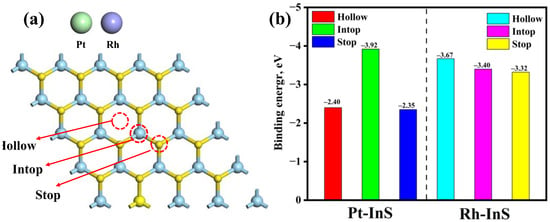

The InS monolayer exhibits a hexagonal lattice structure composed of In and S atoms, with each In atom covalently bonded to three adjacent S atoms, as shown in Figure 1. The calculated lattice constant of pristine InS is 3.94 Å, while the In–S and In–In bond lengths are 2.57 Å and 2.82 Å, respectively, all of which are consistent with previous reports [17,30]. To identify the preferred doping sites for Pt and Rh atoms, three potential adsorption sites, including Intop, Stop, and Hollow, were considered, as illustrated in Figure 2. As shown in Figure 2b, all configurations exhibit negative binding energies, indicating that the doping processes are exothermic and spontaneous. Notably, Pt doping at the Intop site yields the most negative binding energy (−3.92 eV), while Rh doping at the Hollow site results in the most negative value (−3.67 eV). Thus, Pt and Rh atoms preferentially adsorb at the Intop and Hollow sites, respectively. Furthermore, charge density difference (CDD) plots reveal that the doped Pt and Rh atoms act as electron acceptors, acquiring approximately 0.449 e and 0.440 e from the InS monolayer, respectively. This substantial charge transfer between Pt, Rh atoms, and InS monolayer further contributes to the superior stability of the doped systems.

Figure 1.

(a–c) Atomic configurations and (d,e) charge density difference (CDD) of pristine InS, Pt-InS, and Rh-InS monolayers after full relaxation.

Figure 2.

(a) The potential doping sites of InS monolayer for TM (TM = Pt, Rh) atoms and (b) their corresponding binding energy.

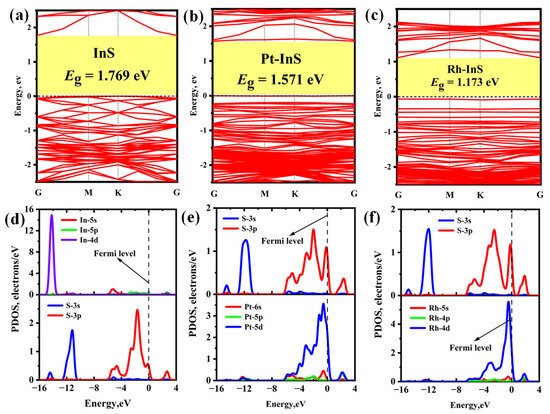

To elucidate the electronic properties of the pristine and decorated InS monolayers, the band structures and projected density of states (PDOS) are calculated (Figure 3). The pristine InS monolayer is an indirect semiconductor with a bandgap (Eg) of 1.769 eV. Upon decoration, the monolayers retain their semiconductor characteristics; however, their bandgaps are consistently reduced. For Pt-InS (Figure 3b), the Eg is reduced to 1.571 eV, while Rh decoration induces a more pronounced reduction, with the Eg narrowing to 1.173 eV (Figure 3c). This tunable bandgap engineering is crucial for optimizing the electronic response in sensing applications. Additionally, the underlying mechanism for structural stability is clarified by the PDOS analysis, as shown in Figure 3d–f. In the pristine InS monolayer, the S-3p orbital hybridizes with the In-5s orbital in the range of −6.00 eV to −3.00 eV, and with the In-5p orbital from −3.00 eV up to the Fermi level, resulting in the formation of In–S covalent bonds. In the Pt-InS and Rh-InS monolayers, the Pt-5d and Rh-4d orbitals exhibit strong overlap with the S-3p orbital across the range of −8.00 eV to 4.00 eV, with pronounced resonance peaks near the Fermi level. This suggests the formation of robust Pt–S and Rh–S covalent bonds in the doped systems, underscoring their excellent structural stability.

Figure 3.

(a–c) Band structure and (d–f) projected density of state (PDOS) of (a,d) InS, (b,e) Pt-InS, and (c,f) Rh-InS monolayers.

Although this study is theoretical, the experimental synthesis of Pt-InS and Rh-InS monolayers is considered highly feasible. High-quality InS monolayers can be fabricated using established techniques such as chemical vapor deposition. Decoration with single Pt or Rh atoms can subsequently be achieved through methods including atomic layer deposition, wet-chemical impregnation followed by reduction, or physical vapor deposition at low flux. A crucial consideration for practical applications is the stability of these single-atom decorations, particularly under sensor operating conditions. Our first-principles calculations provide strong theoretical evidence for their robust stability. The calculated high binding energies suggest strong chemical anchoring of the metal atoms to the InS substrate, resulting in a significant energy barrier against surface diffusion and subsequent aggregation. Therefore, both Pt-InS and Rh-InS systems are predicted to retain their single-atom dispersion under real operating conditions, although long-term stability will ultimately require experimental validation.

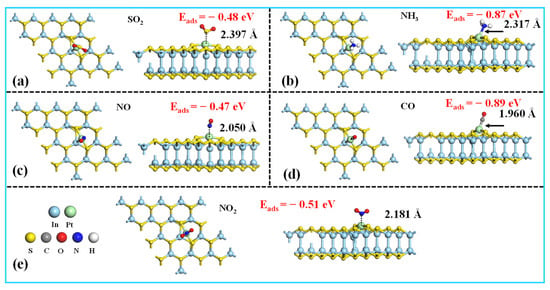

2.2. Adsorption of TIGs on Pt-InS Monolayer

To assess the gas sensing capabilities, we systematically investigated the adsorption behaviors of SO2, NH3, NO, CO, and NO2 on the Pt-InS surface. In our calculations, only the active transition metal (TM) atoms were considered as potential adsorption sites, and various adsorption orientations were explored. The most energetically favorable configurations are presented in Figure 4. CO and NH3 exhibit the strongest binding affinities to the Pt-InS surface, with adsorption energy values of −0.89 eV and −0.87 eV, respectively. As illustrated in Figure 4d, the CO molecule adsorbs atop the Pt atom through its carbon end, resulting in a short Pt–C bond length of 1.960 Å. Similarly, NH3 adsorbs via its nitrogen atom, with a Pt–N distance of 2.317 Å (Figure 4b). These high adsorption energies and short bond lengths indicate a strong chemisorption process. In contrast, NO, NO2, and SO2 show weaker interactions with the Pt-InS surface. The Eads values for NO, NO2, and SO2 are −0.47 eV, −0.51 eV, and −0.48 eV, respectively, with corresponding interaction distances of 2.050 Å (Pt–N for NO), 2.181 Å (Pt–N for NO2), and 2.397 Å (Pt–S for SO2). Therefore, the adsorption of NO, NO2, and SO2 is classified as physical adsorption.

Figure 4.

Top and side views of the most stable structures for the (a) SO2, (b) NH3, (c) NO, (d) CO, and (e) NO2 adsorbed on the Pt-InS monolayer.

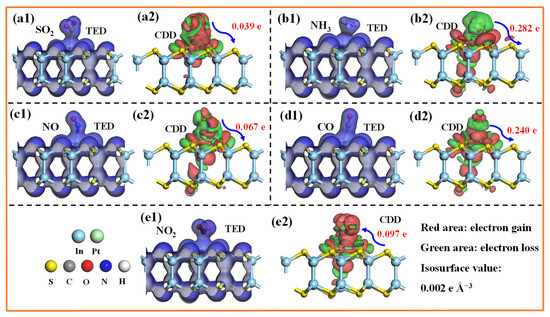

To elucidate the microscopic interactions between the TIGs and the Pt-InS monolayer, we calculated the total electron density (TED) and CDD for each system (Figure 5). All gas molecules exhibit substantial electron sharing with the Pt-InS surface, as indicated by the blue regions between them in Figure 5(a1–e1), suggesting relatively strong interactions. However, the CDD plots reveal notable differences among the gases, as shown in Figure 5(a2–e2). Specifically, SO2, NH3, NO, CO act as electron donors, transferring approximately 0.039 e, 0.282 e, 0.067 e, and 0.240 e to the Pt-InS monolayer, respectively. In contrast, NO2 behaves as an electron acceptor, withdrawing about 0.097 e from the Pt-InS surface. Furthermore, the electron transfer values for NH3 and NO are significantly higher than those for the other gases, indicating a much stronger affinity of the Pt-InS monolayer for NH3 and NO. This observation is consistent with the previously discussed adsorption energy analysis.

Figure 5.

(a1–e1) Total electron density (TED) and (a2–e2) charge density difference (CDD) plots of the adsorbed Pt-InS monolayers with (a1,a2) SO2, (b1,b2) NH3, (c1,c2) NO, (d1,d2) CO, and (e1,e2) NO2.

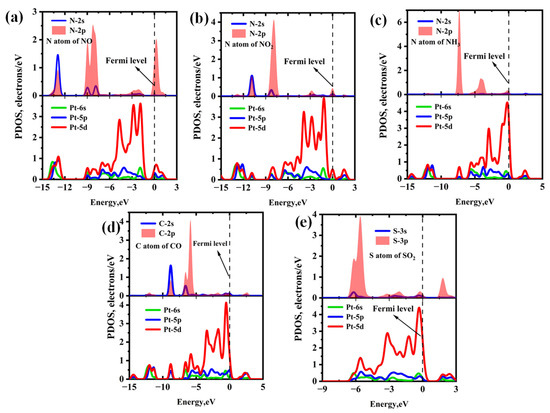

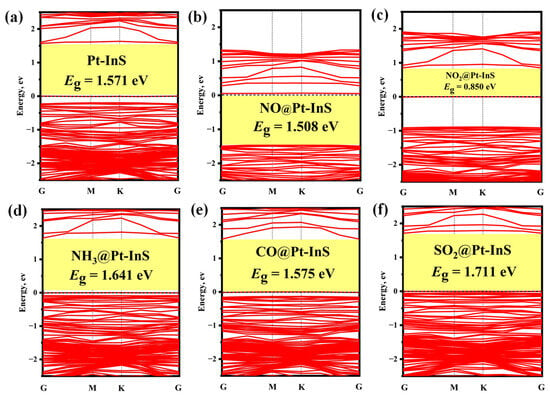

Figure 6 and Figure 7 present the PDOS and band structures of Pt-InS monolayer upon adsorption of various toxic gases, respectively. For the NO, NO2, and NH3 adsorption systems (Figure 6a–c), the adsorption strengths are primarily attributed to orbital hybridizations between N-2p and Pt-5d states within the energy range of −15.00 eV to 3.00 eV. Notably, the orbital overlap in the NH3 adsorption system is more localized and significantly stronger than that observed in the NO and NO2 systems, resulting in the highest adsorption strength for NH3 among the three gases. In the CO@Pt-InS system (Figure 6d), the PDOS reveals pronounced hybridization between the C-2p orbital and Pt-5d state, indicating the formation of a strong Pd-C covalent bond. In contrast, for the SO2@Pt-InS system (Figure 6e), the orbital overlap between S-3p and Pt-5d occurs within a narrow energy range of −6.50 eV to 3.00 eV, with less prominent resonance peaks compared to the other systems, which aligns with the lower adsorption energy of SO2. As shown in Figure 7, the adsorption of NO, NH3, and CO has minimal impact on the band gap and electrical conductivity of pristine Pt-InS. In contrast, SO2 adsorption slightly increases the band gap from 1.571 eV to 1.711 eV, indicating a potential decrease in conductivity. The most pronounced effect is observed with NO2 adsorption (Figure 7c), where the interaction introduces impurity states within the original band gap, resulting in a dramatic reduction in the band gap to 0.850 eV. This substantial narrowing of the band gap by approximately 46% is expected to significantly enhance the electrical conductivity of the material, suggesting a strong and readily detectable sensing response for NO2.

Figure 6.

Projected density of states (PDOS) of different adsorption systems: (a) NO@Pt-InS, (b) NO2@Pt-InS, (c) NH3@Pt-InS, (d) CO@Pt-InS, and (e) SO2@Pt-InS.

Figure 7.

Band structures of different adsorption systems: (a) Pt-InS, (b) NO@Pt-InS, (c) NO2@Pt-InS, (d) NH3@Pt-InS, (e) CO@Pt-InS, and (f) SO2@Pt-InS.

2.3. Adsorption of TIGs on Rh-InS Monolayer

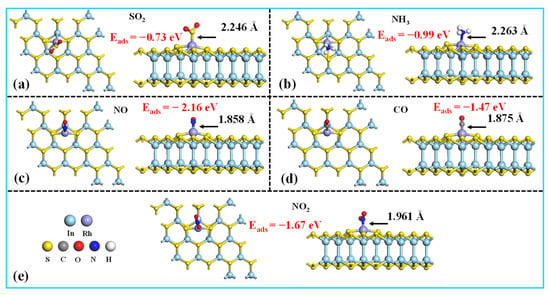

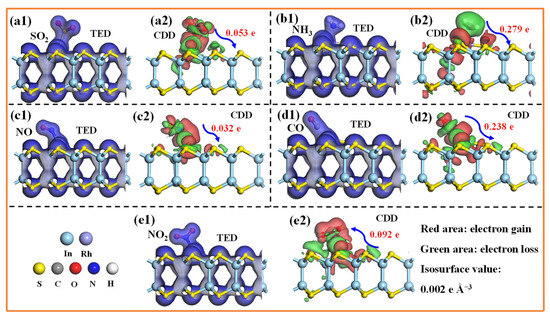

Figure 8 illustrates the most energetically favorable configurations for five TIGs adsorbed on the Rh-InS monolayer. As observed, all gases preferentially bind to the decorated Rh atom. Specifically, the SO2 molecule adsorbs via its sulfur atom, while NH3, NO, and NO2 bind through their respective nitrogen atoms, and CO interacts via its carbon atom. The calculated adsorption energies are −0.73 eV (SO2), −0.99 eV (NH3), −2.16 eV (NO), −1.47 eV (CO), and −1.67 eV (NO2), with corresponding Rh-adsorbate bond lengths of 2.246 Å, 2.263 Å, 1.858 Å, 1.875 Å, and 1.961 Å, respectively. These equilibrium adsorption distances fall within the theoretical bonding ranges, indicating that chemisorption is the dominant adsorption mechanism for these gases. The strong chemical interactions between the gases and the Rh-InS substrate are further supported by the significant electron sharing observed in all five adsorption systems, as depicted in the TED plots in Figure 9(a1–e1). Additionally, the CDD plots (Figure 9(a2–e2)) visualize the spatial redistribution of electrons. SO2, NH3, NO, and CO act as electron donors, transferring approximately 0.053 e, 0.279 e, 0.032 e, and 0.238 e to the Rh-InS substrate, respectively. Conversely, the NO2 functions as an electron acceptor, acquiring about 0.092 e from the monolayer. The substantial charge transfer observed, particularly in the NH3 and CO systems, underscores the significant electronic perturbation of Rh-InS upon gas adsorption.

Figure 8.

Top and side views of the most stable structures for the (a) SO2, (b) NH3, (c) NO, (d) CO, and (e) NO2 adsorbed on the Rh-InS monolayer.

Figure 9.

(a1–e1)Total electron density (TED) and (a2–e2) charge density difference (CDD) plots of the adsorbed Rh-InS monolayers with (a1,a2) SO2, (b1,b2) NH3, (c1,c2) NO, (d1,d2) CO, and (e1,e2) NO2.

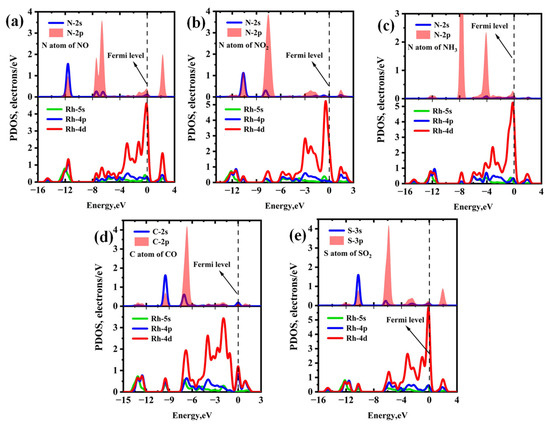

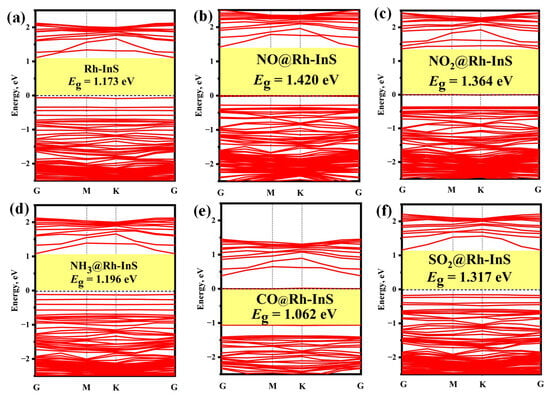

The PDOS and band structure analysis for each Rh-InS adsorption system are presented in Figure 10 and Figure 11, respectively. For the nitrogen-containing species (Figure 10a–c), a significant overlap between the N-2p and Rh-4d orbitals is observed within the energy range of −13.00 eV to 3.00 eV, indicating the formation of strong Rh-N covalent bonds. In the case of CO adsorption (Figure 10d), significant hybridization occurs between the Rh-4d and C-2p orbitals in the energy interval of −10.50 eV to −5.50 eV, with two distinct hybrid peaks appearing at approximately −9.50 eV and −6.85 eV. For SO2 adsorption (Figure 10e), the S-3p orbital exhibits strong hybridization with the Rh-4d orbital across the entire energy range, accompanied by several resonance peaks. Additionally, compared to the bandgap of pristine Rh-InS (Figure 11a), gas interactions induce diverse and significant changes. Notably, NO adsorption induces the most substantial widening of the bandgap to 1.420 eV, whereas CO causes a marked narrowing to 1.062 eV. Other adsorbates like NO2 and SO2 also widen the bandgap, while NH3 has a nearly negligible effect. These electronic alterations are advantageous for enhancing the gas sensing capabilities of the Rh-InS monolayer.

Figure 10.

Projected density of states (PDOS) of different adsorption systems: (a) NO@Rh-InS, (b) NO2@Rh-InS, (c) NH3@Rh-InS, (d) CO@Rh-InS, and (e) SO2@Rh-InS.

Figure 11.

Band structures of different adsorption systems: (a) Rh-InS, (b) NO@Rh-InS, (c) NO2@Rh-InS, (d) NH3@Rh-InS, (e) CO@Rh-InS, and (f) SO2@Rh-InS.

2.4. Evaluation of InS-Based Gas Sensors

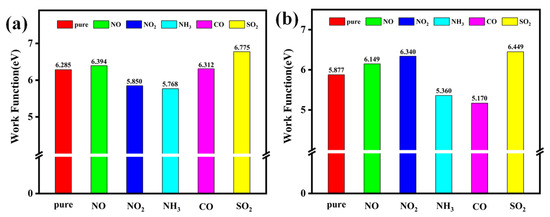

Sensitivity refers to the ability of a material to detect and respond to the presence of a specific gas analyte. The adsorption of gas molecules onto Pt-InS and Rh-InS fundamentally alters their band gap (Eg), electrical conductivity (σ), and work function (Φ). These properties are therefore essential metrics for evaluating the sensitivity of these materials. The parameters σ and Φ are defined as follows [31,32]:

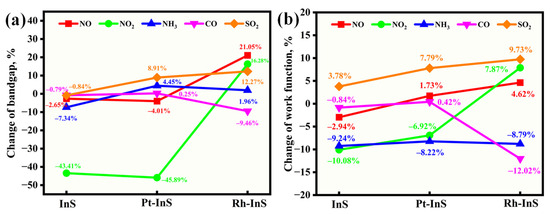

Here, A is a constant, kB is the Boltzmann constant, and T denotes temperature. and represent the vacuum level and Fermi level, respectively. Based on these definitions, the work functions of Pt-InS and Rh-InS monolayers, both before and after gas adsorption, are presented in Figure 12. Furthermore, Figure 13 illustrates the changes in band gap (ΔEg) and work function (ΔΦ) induced by the adsorption of five toxic gases.

Figure 12.

Work functions of the (a) Pt-InS and (b) Rh-InS monolayers before and after the adsorption of toxic gases.

Figure 13.

Rate of changes in (a) band gap and (b) work function for different toxic gases adsorbed on the InS, Pt-InS, and Rh-InS monolayers.

As shown in Figure 13a, the pristine InS and Pt-InS monolayers exhibit negligible band gap modulation upon exposure to the NO, NH3, CO, and SO2 molecules, with most changes falling within ±5%. However, the adsorption of NO2 induces significant changes in the band gap of both InS and Pt-InS monolayers, with |ΔEg| values of 43.41% and 45.89%, respectively. Due to the weak adsorption strength of InS for these gases, only the Pt-InS monolayer exhibits excellent gas sensitivity toward NO2. In contrast, the Rh-InS monolayer exhibits an even more pronounced response, characterized by substantial band gap widening for NO (+21.05%) and NO2 (+16.28%). Additionally, SO2 and CO adsorption results in considerable |ΔEg| values of 12.27% and 9.46%, respectively, while NH3 adsorption leads to negligible band gap changes. Therefore, the Rh-InS monolayer is well-suited to function as a resistive gas sensor for the detection of NO, NO2, SO2 and CO molecules.

As illustrated in Figure 12 and Figure 13b, the Pt-InS monolayer exhibits different work function modulation, with positive changes observed for NO (+1.73%), CO (+0.42%), and SO2 (+7.79%). In contrast, NO2 and NH3 adsorption lead to decreases in work function (−6.92% and −8.22%, respectively). These findings suggest that the Pt-InS monolayer can serve as a work function-based gas sensor for SO2 and NH3. By comparison, the Rh-InS monolayer shows more substantial changes in work function. Specifically, SO2 adsorption results in a significant increase (+9.73%), while NH3 and CO adsorption cause decreases of −8.79% and −12.02%, respectively. The pronounced changes in work function for Rh-InS suggest strong electronic interactions and charge transfer, indicating that the Rh-InS monolayer exhibits high sensitivity and holds great promise as a work function-based gas sensor for the detection of SO2, NH3, and CO.

Recovery time is another critical parameter that determines how quickly a sensor returns to its initial state following the removal of the target gas. According to transition state theory, the recovery time (τ) can be expressed as [33]

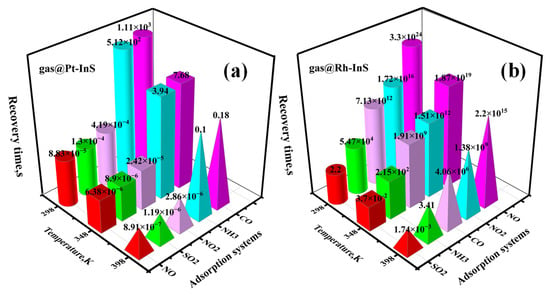

where is the attempt frequency (1012 s−1), Eads is the adsorption energy, and T is the operating temperature (K). Figure 14 presents the recovery times for the desorption of toxic gases from the Pt-InS and Rh-InS surfaces at various temperatures.

Figure 14.

Recovery times for different gases adsorbed on (a) Pt-InS and (b) Rh-InS monolayers at various temperatures.

For the Pt-InS monolayer (Figure 14a), the recovery times for NO, NO2, and SO2 at room temperature (298 K) are 8.83 × 10−5 s, 4.19 × 10−4 s, and 1.3 × 10−4 s, respectively. Such extremely short contact times between these gases and Pt-InS are insufficient to generate detectable signals. Conversely, CO and NH3 exhibit exceptionally prolonged recovery times, reaching approximately 1.11 × 103 s and 5.12 × 102 s at 298 K, suggesting that the two gases are difficult to timely desorb from the Pt-InS surface. When the temperature is raised to 348 K, Pt-InS shows excellent reusability for CO and NH3, with recovery times reduced sharply to 7.68 s and 3.94 s, respectively. For the Rh-InS monolayer (Figure 14b), the recovery times for NO, NO2, NH3 and CO are exceedingly long at 298 K, ranging from 5.47 × 104 s to 3.30 × 1024 s, reflecting strong binding interactions that significantly impede rapid desorption. Even at 398 K, the recovery times remain substantial, except for the NH3@Rh-InS system, which achieves a recovery time of 3.41 s. Notably, Rh-InS exhibits a moderate recovery time of approximately 2.20 s for SO2 at 298 K. In conclusion, Rh-InS is a promising candidate for a reusable sensing material for SO2 at room temperature. It is important to note that this prediction is based on calculated recovery times in an ideal system, and experimental validation would be necessary to account for kinetic effects and environmental factors in real-world applications. In contrast, Pt-InS is better suited as a work function-based gas sensor for NH3 at high temperature (348 K).

3. Conclusions

In this study, the potential of Pt-InS and Rh-InS monolayers as high-performance gas sensors for five TIGs was systematically investigated using first-principles calculations. The electronic properties of each adsorption system, including the PDOS, CDD, band structures, and work function, were comprehensively analyzed. The key conclusions are summarized as follows.

(1) Pt and Rh atoms can be stably anchored onto the InS monolayer at the Intop and Hollow sites, exhibiting substantial binding energies of −3.92 eV and −3.67 eV, respectively. Furthermore, the incorporation of Pt and Rh significantly reduces the band gap and enhances the electrical conductivity of the pristine InS monolayer.

(2) NO, NO2, and SO2 are physically adsorbed on the Pt-InS monolayer, whereas CO and NH3 undergo chemisorption. In contrast, all five gases interact with the Rh-InS monolayer via chemisorption. The underlying microscopic mechanisms are elucidated through analyses of orbital hybridization.

(3) The Pt-InS monolayer demonstrates exceptional sensitivity toward NO2, attributed to the introduction of impurity states within the band gap upon NO2 adsorption. In comparison, the Rh-InS monolayer exhibits broad sensing capabilities for NO, NO2, SO2 and CO, as evidenced by significant changes in both band gap and work function.

(4) Recovery time analysis indicates that, based on theoretical calculations, the Rh-InS monolayer is a promising potential reusable sensor for SO2 detection at room temperature, featuring a calculated rapid recovery time of 2.20 s. Conversely, the Pt-InS system is more suitable as a practical sensor for NH3 at high temperature, enabling efficient reusability.

4. Computational Details

All the spin calculations in this study were performed using the DMol3 module within the Materials Studio 2020 package [34]. To ensure both computational efficiency and accuracy, a 4 × 4 × 1 supercell model, which is consistent with that employed in reference [22], was adopted. Following convergence testing (Figure S1), a vacuum layer of 20 Å was introduced along the vertical direction to eliminate interactions between atomic layers. During structural optimization and energy calculations, the generalized gradient approximation (GGA) with the Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof (PBE) functional was utilized [35], in conjunction with Grimme’s DFT-D3 dispersion correction to account for van der Waals interactions [36]. The DFT semi-core pseudopotentials (DSPPs) were employed to treat the core electrons [37], and a double numerical plus polarization (DNP) basis set with an orbital cutoff radius of 5.2 Å was applied. The DIIS iteration number was set to 6 [38], and a smearing value of 0.005 Ha was applied. The convergence criteria for geometric optimization were as follows: energy self-consistency ≤ 1.0 × 10−5 Ha, atomic force ≤ 2.0 × 10−3 Ha/Å, and maximum displacement ≤ 5.0 × 10−3 Ha/Å. Furthermore, Monkhorst–Pack k-point density [39] convergence tests were performed for the TM-InS systems (Figure S1), confirming the use of a 4 × 4 × 1 k-point grid for structural optimization and a denser 10 × 10 × 1 grid for property calculations.

To evaluate the stability of the Pt-InS and Rh-InS monolayers, the binding energy (Ebin) at different doping sites was calculated according to the following equation [12]:

where ETM-InS, EInS, and ETM are the total energies of the TM-doped InS system, the pristine InS, and an isolated TM atom (TM = Pt, Rh), respectively. To further analyze the gas adsorption behavior of the TM–InS system, the adsorption energy (Eads) was calculated as follows [40,41]:

where Egas@TM-InS is the total energy of the TM–InS system with gas adsorption. ETM-InS and Egas are the total energies of the clean TM–InS and isolated gas molecule, respectively. Generally, a larger absolute value of Eads indicates a stronger adsorption effect.

Eb = ETM-InS − EInS − ETM

Eads = Egas@TM-InS − ETM-InS − Egas

Charge transfer (ΔQ) in this work was computed using the Mulliken population analysis method [42], which is widely used for its simplicity in analyzing electron density distributions. The amount of ΔQ is given by [43]

where Qadsorbed-gas and Qfree-gas represent the charges of a single gas molecule after and before adsorption, respectively. A positive value of ΔQ indicates that electron transfers from the gas molecule to the TM–InS surface, whereas a negative value signifies that electron transfers from the TM–InS system to the gas molecule.

ΔQ = Qadsorbed-gas − Qfree-gas

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/molecules30234510/s1, Figure S1: Convergence tests for computational parameters. (a) Adsorption energy of NH3 on the Pt-InS monolayer as a function of the vacuum layer thickness, (b) total energy of a 4 × 4 × 1 InS monolayer supercell as a function of the k-point mesh.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.H., S.L. and J.D.; Methodology, J.L. (Jinyan Li), J.L. (Junxian Lin) and D.H.; Software, S.L.; Validation, J.L. (Junxian Lin), S.H. and J.D.; Formal analysis, J.L. (Junxian Lin), S.H. and D.H.; Investigation, J.L. (Jinyan Li), S.H., D.H. and J.D.; Resources, D.H. and S.L.; Data curation, S.L.; Writing—original draft, J.L. (Jinyan Li), J.L. (Junxian Lin), D.H. and J.D.; Writing—review & editing, J.L. (Jinyan Li) and J.D.; Visualization, J.L. (Jinyan Li), J.L. (Junxian Lin) and S.L.; Supervision, S.L. and J.D.; Project administration, S.H., D.H. and J.D.; Funding acquisition, D.H. and J.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors gratefully acknowledge financial support from the Project of Key Laboratory of General Universities in Guangdong Province (No. 2023KSYS007), the Special Projects in Key Fields of Ordinary Universities in Guangdong Province (No. 2024ZDZX3030), and the Science and Technology Planning Project of Guangdong Province (No. 2017B090921002).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- Wang, H.; Lustig, W.P.; Li, J. Sensing and capture of toxic and hazardous gases and vapors by metal–organic frameworks. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018, 47, 4729–4756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Ahumada, E.; Díaz-Ramírez, M.L.; Velásquez-Hernández, M.d.J.; Jancik, V.; Ibarra, I.A. Capture of toxic gases in MOFs: SO2, H2S, NH3 and NOx. Chem. Sci. 2021, 12, 6772–6799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saxena, P.; Shukla, P. A review on recent developments and advances in environmental gas sensors to monitor toxic gas pollutants. Environ. Prog. Sustain. 2023, 42, e14126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Zaman, S.U.; Joy, K.S.; Jeba, F.; Kumar, P.; Salam, A. Impact of fine particulate matter and toxic gases on the health of school children in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Environ. Res. Commun. 2023, 5, 025004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onishchenko, G.; Nikolayeva, N.; Rakitskii, V.; Ilnitskaya, A.; Filin, A.; Korolev, A.; Nikitenko, E.; Denisova, E.; Tsakalof, A.; Guseva, E.; et al. Comprehensive study of health effects of plasma technology occupational environment: Exposure to high frequency and intensity noise and toxic gases. Environ. Res. 2023, 216, 114691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Kumar, A.; Chandra, R. Environmental pollutants of paper industry wastewater and their toxic effects on human health and ecosystem. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2022, 20, 101250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Xiong, H.; Gan, L.; Deng, G. Theoretical investigation of FeMnPc, Fe2Pc, Mn2Pc monolayers as potential gas sensors for nitrogenous toxic gases. Surf. Interfaces 2024, 45, 103910–103923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, M.; Tavangar, Z. Effect of strain and charge injection on pollutant molecule sensing using black phosphorene: A DFT study. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2025, 698, 163114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tereshkov, M.; Dontsova, T.; Saruhan, B.; Krüger, S. Metal Oxide-Based Sensors for Ecological Monitoring: Progress and Perspectives. Chemosensors 2024, 12, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berwal, P.; Sihag, S.; Rani, S.; Kumar, A.; Jatrana, A.; Singh, P.; Dahiya, R.; Kumar, A.; Dhillon, A.; Sanger, A.; et al. Hybrid Metal Oxide Nanocomposites for Gas-Sensing Applications: A Review. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2023, 62, 14835–14852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, Y.; Cui, H.; Zhou, Q.; Su, X.; Kuang, Y.; Li, X. C2N monolayer as NH3 and NO sensors: A DFT study. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 487, 488–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Xie, K.; Wang, P.; Xu, D.; Lin, L. Noble metals (Os, Ir, Pt) loaded PtSe2 monolayer as high-performance SF6 decomposition gas sensor: A DFT study. Colloids Surf. A 2025, 726, 137945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Huang, H.; Zhang, H.; Yang, L.; Li, W.; Gan, L.; Xiong, H. Fe-X (X = C, P, S) atom pair-decorated g-CN monolayers for sensing toxic thermal runaway gases in lithium-ion batteries: A DFT Study. Environ. Res. 2025, 286, 122777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senthilkumar, S.N.; Panjulingam, N.; Lakshmipathi, S. 2D MoS2 for detection of COVID-19 biomarkers—A first-principles study. Phys. Scr. 2025, 100, 025013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.; Zhan, W.; Zhang, H. Theoretical investigation of Ni, Cu, Nb-doped HfS2 monolayers for sensing biomarkers relevant to early health status. Surf. Interfaces 2025, 72, 106956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Shan, Z.; Yuejing, B.; Xiaoping, J.; Cui, H. Ni-decorated WS2-WSe2 heterostructure as a novel sensing candidate upon C2H2 and C2H4 in oil-filled transformers: A first-principles investigation. Mol. Phys. 2025, 123, e2492391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Qian, C.; Zuo, L.; Zhao, W.; Yang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Yi, L. Prediction of magnetic properties of 3d transition-metal adsorbed InS monolayers. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2024, 603, 172241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Ni, L.; Duan, L.; Zhang, Y. Direct Z-scheme AlAs/InS heterojunction: A promising photocatalyst for water splitting. Surf. Interfaces 2025, 56, 105501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Olimpio, G.; Boukhvalov, D.W.; Galstyan, V.; Occhiuzzi, J.; Vorochta, M.; Amati, M.; Milosz, Z.; Gregoratti, L.; Istrate, M.C.; Kuo, C.N.; et al. Unlocking superior NO2 sensitivity and selectivity: The role of sulfur abstraction in indium sulfide (InS) nanosheet-based sensors. J. Mater. Chem. A 2024, 12, 10329–10340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, R.; Han, R.; Lin, X.; Wu, P. First-principles investigate on the electronic structure and magnetic properties of 3D transition metal doped honeycomb InS monolayer. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2023, 608, 155240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, R.; Ghafoor, F.; Zhang, Q.; Rahman, A.U.; Iqbal, M.W.; Somaily, H.H.; Dahshan, A. A First-Principles Study of Enhanced Ferromagnetism in a Two-Dimensional Cr-Doped InS Monolayer. J. Electron. Mater. 2022, 51, 6252–6263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.Y.; Xiong, M.; Zeng, Z.Y.; Chen, X.R.; Chen, Q.F. Comparative study of elastic, thermodynamic properties and carrier mobility of InX (X=O, S, Se, Te) monolayers via first-principles. Solid State Commun. 2021, 326, 114163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Szökölová, K.; Nasir, M.Z.M.; Sofer, Z.; Pumera, M. Electrochemistry of Layered Semiconducting AIIIBVI Chalcogenides: Indium Monochalcogenides (InS, InSe, InTe). ChemCatChem 2019, 11, 2634–2642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Li, J.; Dai, Y.; Wei, Y. Engineering the electronic and optoelectronic properties of InX (X = S, Se, Te) monolayers via strain. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017, 19, 4855–4860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Shen, T.; Liu, C.; Feng, Y.; Liu, X.; Wang, C. Adsorption properties of MoS2 monolayers modified with TM (Au, Ag, and Cu) on hazardous gases: A first-principles study. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2024, 174, 108254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Wu, H.; He, D.; Ma, S. Noble metal (Pd, Pt)-functionalized WSe2 monolayer for adsorbing and sensing thermal runaway gases in LIBs: A first-principles investigation. Environ. Res. 2025, 269, 120847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Xu, Y.; Wu, Z.; Hou, Z.; Qin, W.; Liu, X.; Shi, J.; Long, Y. Adsorption of Nitrogen-Containing Toxic Gases on Transition Metal (Pt, Ag, Au)-Modified Janus ZrSSe Monolayers for Sensing Applications: A DFT Study. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2025, 8, 3163–3174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Hensley, A.J.R.; Giannakakis, G.; Therrien, A.J.; Sukkar, A.; Schilling, A.C.; Groden, K.; Ulumuddin, N.; Hannagan, R.T.; Ouyang, M.; et al. Developing single-site Pt catalysts for the preferential oxidation of CO: A surface science and first principles-guided approach. Appl. Catal. B Environ. Energy 2021, 284, 119716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Yin, H.; Yang, S.; Lei, G.; Wang, Z.; Xu, H.; Gu, H. WS2 monolayer decorated with single-atom Pt for outstanding H2 adsorption and sensing: A DFT study. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 141, 1078–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirci, S.; Avazlı, N.; Durgun, E.; Cahangirov, S. Structural and electronic properties of monolayer group III monochalcogenides. Phys. Rev. B 2017, 95, 115409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, Y.; Xiong, H.; Deng, G.; Gan, L. Theoretical investigations of adsorption and sensing properties of M2Pc (M = Cr, Mo) monolayers towards volatile organic compounds. Colloids Surf. A 2025, 717, 136750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mistry, H.; Vadalkar, S.; Vyas, K.N.; Jha, P.K. Adsorption mechanism of Ni decorated α-CN monolayer towards CO, NO, and NH3 gases: Insights from DFT and semi-classical studies. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2025, 186, 109106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Zeng, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, G.; Sun, K.; Xu, M.; Chen, D.; Jia, P. Adsorption and sensing characteristics of transition metal (Au, Fe, Pt, Rh and Cu) doped WS2 on dissolved gases in transformer oil: A DFT perspective. Comput. Theor. Chem. 2025, 1251, 115327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delley, B. From molecules to solids with the DMol3 approach. J. Chem. Phys. 2000, 113, 7756–7764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, B.; Hansen, L.B.; Nørskov, J.K. Improved adsorption energetics within density-functional theory using revised Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof functionals. Phys. Rev. B 1999, 59, 7413–7421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimme, S. Semiempirical GGA-type density functional constructed with a long-range dispersion correction. J. Comput. Chem. 2006, 27, 1787–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vozzi, C.; Negro, M.; Calegari, F.; Sansone, G.; Nisoli, M.; De Silvestri, S.; Stagira, S. Generalized molecular orbital tomography. Nat. Phys. 2011, 7, 822–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellers, H. The C2-DIIS convergence acceleration algorithm. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 1993, 45, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monkhorst, H.J.; Pack, J.D. Special points for Brillouin-zone integrations. Phys. Rev. B 1976, 13, 5188–5192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khammuang, S.; Wongphen, K.; Hussain, T.; Kotmool, K. Enhanced NH3 and NO sensing performance of Ti3C2O2 MXene by biaxial strain: Insights from first-principles calculations. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2025, 27, 3827–3833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, H.; Li, X.; Kalwar, B.A.; Tan, X.; Naich, M.R. Adsorption and work function type sensing of SF6 decompositions (SO2, SOF2, SO2F2, H2S and HF) based on Fe and Cu decorated B4CN3 monolayer. A first-principles study. Chem. Phys. 2025, 589, 112522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, H.; Liu, B.; Zhang, H.; Qin, J. Theoretical insight into two-dimensional M-Pc monolayer as an excellent material for formaldehyde and phosgene sensing. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 543, 148805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Xiong, H.; Zhang, J. Proposals for gas-detection improvement of the FeMPc monolayer towards ethylene and formaldehyde by using bimetallic synergy. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2024, 26, 12070–12083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).