Elucidation of the Ro-Vibrational Band Structures in the Silicon Tetrafluoride Spectra from Accurate Ab Initio Calculations

Abstract

1. Introduction

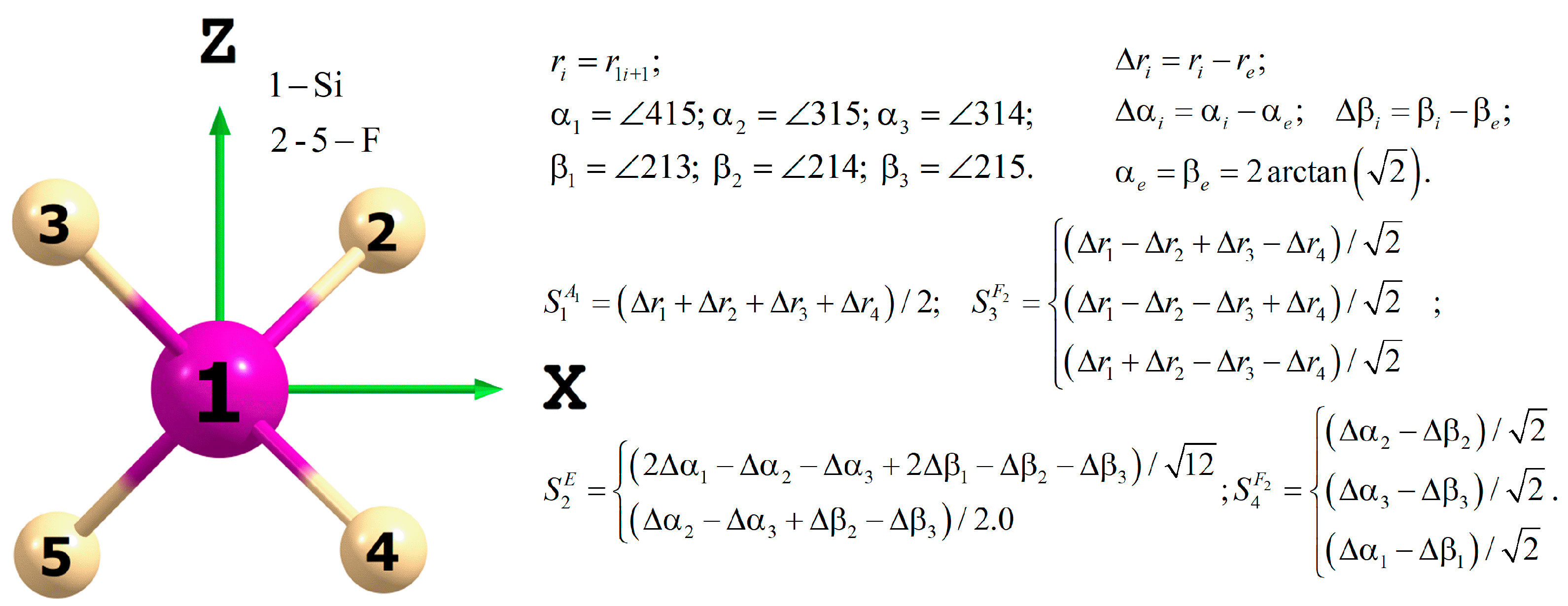

2. Analytical Model of the PES and DMS

3. Ab Initio Calculations

3.1. PES

3.2. DMS

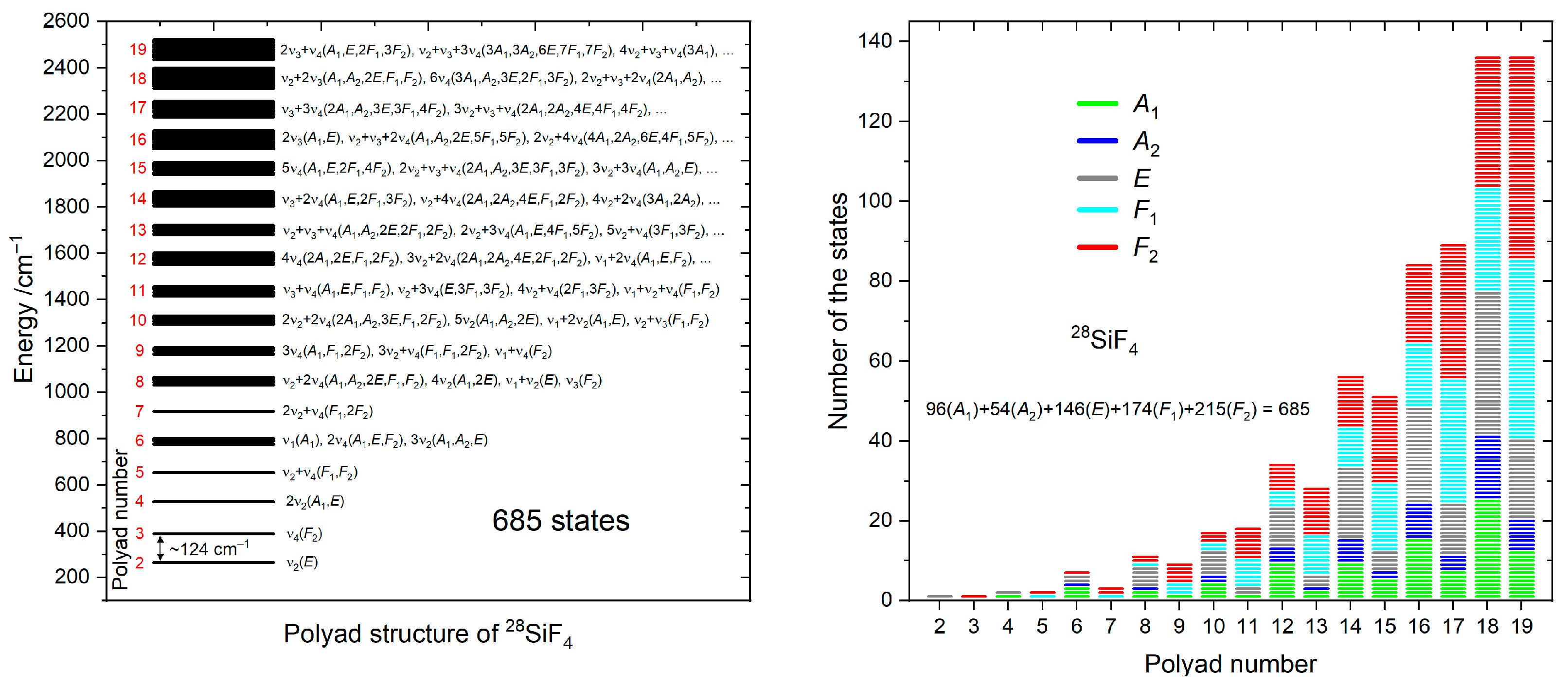

4. Effective Hamiltonian and Dipole Moment Operator

5. Partition Function

6. Cut-Off Values and Super-Lines

7. Validation

7.1. General Comments

7.2. Region: 0–300 cm−1

7.3. Region of ν4(F2)

7.4. Region: 570–880 cm−1

7.5. Region of ν3(F2)

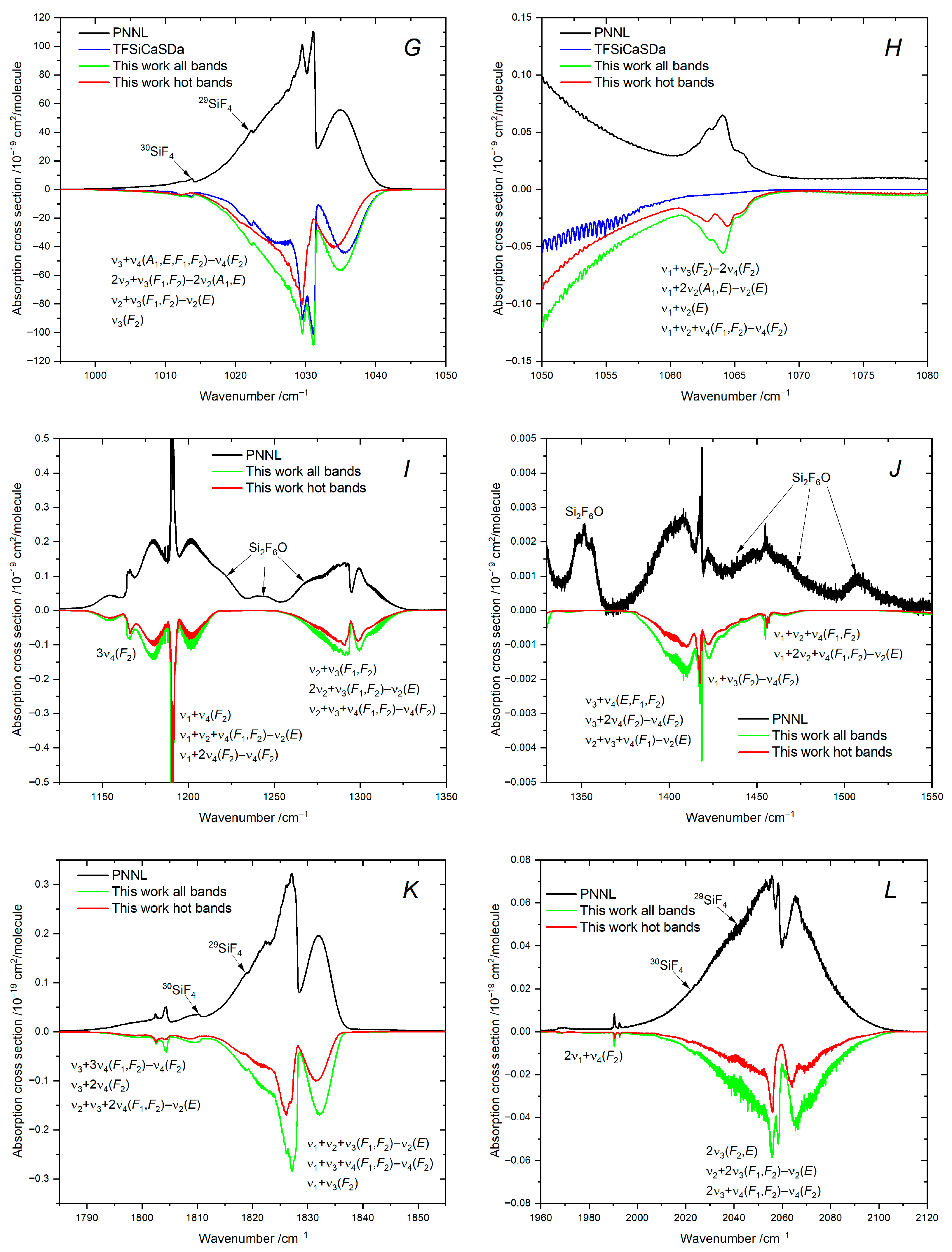

7.6. Region: 1050–1550 cm−1

7.7. Region: 1790–2120 cm−1

8. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, H.; Wu, P.; Wu, Z.; Shi, L.; Cheng, L. New insight into the electronic structure of SiF4: Synergistic back-donation and the eighteen-electron rule. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2022, 24, 17679–17685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hada, M.; Takahashi, M.; Sakaguchi, Y.; Fujii, T.; Minami, M. Chamber in-situ estimation during etching process by SiF4 monitoring using laser absorption spectroscopy. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2023, 62, SI1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernst, O.C.; Uebel, D.; Brendler, R.; Kraushaar, K.; Steudel, M.; Acker, J.; Kroke, E. Silicon-28-Tetrafluoride as an Educt of Isotope-Engineered Silicon Compounds and Bulk Materials for Quantum Systems. Molecules 2024, 29, 4222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ignatov, S.K.; Sennikov, P.G.; Chuprov, L.A.; Razuvaev, A.G. Thermodynamic and kinetic parameters of elementary steps in gas-phase hydrolysis of SiF4. Quantum-chemical and FTIR spectroscopic studies. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2003, 52, 837–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sennikov, P.G.; Ignatov, S.K.; Schrems, O. Identification of the products of partial hydrolysis of silicon tetrafluoride by matrix isolation IR spectroscopy. Russ. J. Inorg. Chem. 2010, 55, 413–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Liu, S.; Shi, L.; Liu, G.; Xiao, W.; Zhu, H. Research on the Production of Hydrogen Fluoride from Silicon Tetrafluoride Using 2.45 GHz Microwave Plasma. Processes 2025, 13, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, P.; Chaffin, C.; Maciejewski, A.; Oppenheimer, C. Remote determination of SiF4 in volcanic plumes: A new tool for volcano monitoring. Geophys. Res. Lett. 1996, 23, 249–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, S.P.; Goff, F.; Counce, D.; Siebe, C.; Delgado, H. Passive infrared spectroscopy of the eruption plume at Popocatépetl volcano, Mexico. Nature 1998, 396, 563–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stremme, W.; Krueger, A.; Harig, R.; Grutter, M. Volcanic SO2 and SiF4 visualization using 2-D thermal emission spectroscopy–Part 1: Slant-columns and their ratios. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2012, 5, 275–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taquet, N.; Meza Hernández, I.; Stremme, W.; Bezanilla, A.; Grutter, M.; Campion, R.; Palm, M.; Boulesteix, T. Continuous measurements of SiF4 and SO2 by thermal emission spectroscopy: Insight from a 6-month survey at the Popocatépetl volcano. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 2017, 341, 255–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taquet, N.; Rivera Cárdenas, C.; Stremme, W.; Boulesteix, T.; Bezanilla, A.; Grutter, M.; García, O.; Hase, F.; Blumenstock, T. Combined direct-sun ultraviolet and infrared spectroscopies at Popocatépetl volcano (Mexico). Front. Earth Sci. 2023, 11, 1062699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, T.; Sato, M.; Shimoike, Y.; Notsu, K. High SiF4/HF ratio detected in Satsuma-Iwojima volcano’s plume by remote FT-IR observation. Earth Planets Space 2002, 54, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, C.W.; Pine, A.S. Doppler-limited spectrum and analysis of the 3ν3 manifold of SiF4. J. Mol. Spectrosc. 1982, 96, 404–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDowell, R.S.; Reisfeld, M.J.; Patterson, C.W.; Krohn, B.J.; Mariena, C.; Vasquez, M.C.; Laguna, G.A. Infrared spectrum and potential constants of silicon tetrafluoride. J. Chem. Phys. 1982, 77, 4337–4343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.-G.; Sibert, E.L.; Martin, J.M.L. Anharmonic force field and vibrational frequencies of tetrafluoromethane (CF4) and tetrafluorosilane (SiF4). J. Chem. Phys. 2000, 112, 1353–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, F.; Cuisset, A.; Elmaleh, C.; Hindle, F.; Mouret, G.; Rey, M.; Richard, C.; Boudon, V. Unrivaled accuracy in measuring rotational transitions of greenhouse gases: THz CRDS of CF4. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2024, 26, 12345–12357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, C.W.; McDowell, R.S.; Nereson, N.G.; Krohn, B.J.; Wells, J.S.; Petersen, F.R. Tunable laser diode study of the ν3 band of SiF4 near 9.7 μm. J. Mol. Spectrosc. 1982, 91, 416–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takami, M.; Kuze, H. Infrared–microwave double resonance spectroscopy of the SiF4 ν3 fundamental using a tunable diode laser. J. Chem. Phys. 1983, 78, 2204–2209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jörissen, L.; Prinz, H.; Kreiner, W.A.; Wenger, C.; Pierre, G.; Magerl, G.; Schupita, W. The ν3 fundamental of silicon tetrafluoride. Spectroscopy with laser sidebands. Can. J. Phys. 1989, 67, 532–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jörissen, L.; Kreiner, W.A.; Chen, Y.-T.; Oka, T. Observation of ground state rotational transitions in silicon tetrafluoride. J. Mol. Spectrosc. 1986, 120, 233–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudon, V.; Manceron, L.; Richard, C. High-resolution spectroscopy and analysis of the ν3, ν4 and 2ν4 bands of SiF4 in natural isotopic abundance. J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transf. 2020, 253, 107114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudon, V.; Richard, C.; Manceron, L. High-Resolution spectroscopy and analysis of the fundamental modes of 28SiF4. Accurate experimental determination of the Si–F bond length. J. Mol. Spectrosc. 2022, 383, 111549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merkulova, M.; Boudon, V.; Manceron, L. Analysis of high-resolution spectra of SiF4 combination bands. J. Mol. Spectrosc. 2023, 391, 111738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, C.; Ben Fathallah, O.; Hardy, P.; Kamel, R.; Merkulova, M.; Rotger, M.; Ulenikov, O.N.; Boudon, V. CaSDa24: Latest updates to the Dijon calculated spectroscopic databases. J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transf. 2024, 327, 109127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpe, S.W.; Johnson, T.J.; Sams, R.L.; Chu, P.M.; Rhoderick, G.C.; Johnson, P.A. Gas-Phase Databases for Quantitative Infrared Spectroscopy. Appl. Spectrosc. 2004, 58, 1452–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey, M.; Chizhmakova, I.S.; Nikitin, A.V.; Tyuterev, V.G. Understanding global infrared opacity and hot bands of greenhouse molecules with low vibrational modes from first-principles calculations: The case of CF4. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2018, 20, 21008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papoušek, D.; Aliev, M.R. Molecular Vibrational-Rotational Spectra. In Theory and Applications of High Resolution Infrared, Microwave and Raman Spectroscopy of Polyatomic Molecules; Elsevier Scientific Pub. Co.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands; Oxford, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Knizia, G.; Adler, T.B.; Werner, H.-J. Simplified CCSD(T)-F12 methods: Theory and benchmarks. J. Chem. Phys. 2009, 130, 054104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werner, H.-J.; Knowles, P.J.; Manby, F.R.; Black, J.A.; Doll, K.; Heßelmann, A.; Kats, D.; Köhn, A.; Korona, T.; Kreplin, D.A.; et al. The Molpro quantum chemistry package. J. Chem. Phys. 2020, 152, 144107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, H.-J.; Knowles, P.J.; Celani, P.; Györffy, W.; Hesselmann, A.; Kats, D.; Knizia, G.; Köhn, A.; Korona, T.; Kreplin, D.; et al. MOLPRO, Version 2019.2; A Package of Ab Initio Programs. Available online: https://www.molpro.net (accessed on 16 May 2025).

- Egorov, O.; Rey, M.; Kochanov, R.V.; Nikitin, A.V.; Tyuterev, V. High-level ab initio study of disulfur monoxide: Ground state potential energy surface and band origins for six isotopic species. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2023, 811, 140216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mester, D.; Nagy, P.R.; Csóka, J.; Gyevi-Nagy, L.; Szabó, P.B.; Horváth, R.A.; Petrov, K.; Hégely, B.; Ladóczki, B.; Samu, G.; et al. Overview of Developments in the MRCC Program System. J. Phys. Chem. A 2025, 129, 2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kállay, M.; Nagy, P.R.; Mester, D.; Gyevi-Nagy, L.; Csóka, J.; Szabó, P.B.; Rolik, Z.; Samu, G.; Hégely, B.; Ladóczki, B.; et al. Mrcc, a Quantum Chemical Program Suite. Available online: https://www.mrcc.hu (accessed on 16 May 2025).

- Burtsev, A.P.; Bocharov, V.N.; Ignatov, S.K.; Kolomiitsova, T.D.; Sennikov, P.G.; Tokhadze, K.G.; Chuprov, L.A.; Shchepkin, D.N.; Schrems, O. Integral intensities of absorption bands of silicon tetrafluoride in the gas phase and cryogenic solutions: Experiment and calculation. Opt. Spectrosc. 2005, 98, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, C.; Hornig, D.F. Calculation of Dipole Derivatives from Infrared Reflection Spectra or Raman Spectra of Crystals. J. Chem. Phys. 1957, 26, 707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, E.R.; Meredith, G.R. Raman spectra of SiF4 and GeF4 crystals. J. Chem. Phys. 1977, 67, 4132–4138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey, M. Novel methodology for systematically constructing global effective models from ab initio-based surfaces: A new insight into high-resolution molecular spectra analysis. J. Chem. Phys. 2022, 156, 224103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey, M. Group-theoretical formulation of an Eckart-frame kinetic energy operator in curvilinear coordinates for polyatomic molecules. J. Chem. Phys. 2019, 151, 024101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, J.K.G. Simplification of the molecular vibration-rotation hamiltonian. Mol. Phys. 1968, 15, 479–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egorov, O.; Nikitin, A.; Rey, M.; Rodina, A.; Tashkun, S.; Tyuterev, V. Global modeling of NF3 line positions and intensities from far to mid-infrared up to 2200 cm−1. J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transf. 2019, 239, 106668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey, M.; Chizhmakova, I.S.; Nikitin, A.V.; Tyuterev, V.G. Towards a complete elucidation of the ro-vibrational band structure in the SF6 infrared spectrum from full quantum-mechanical calculations. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2021, 23, 12115–12126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egorov, O.; Rey, M. First Ab Initio Line Lists for Triatomic Sulfur-Containing Molecules: S2O and S3. J. Phys. Chem. A 2024, 128, 8144–8158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rey, M.; Viglaska, D.; Egorov, O.; Nikitin, A.V. A numerical-tensorial “hybrid” nuclear motion Hamiltonian and dipole moment operator for spectra calculation of polyatomic nonrigid molecules. J. Chem. Phys. 2023, 159, 114103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egorov, O.; Rey, M.; Viglaska, D.; Nikitin, A.V. Rovibrational Line Lists of Triplet and Singlet Methylene. J. Phys. Chem. A 2024, 128, 6960–6971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gamache, R.R.; Vispoel, B.; Rey, M.; Nikitin, A.; Tyuterev, V.; Egorov, O.; Gordon, I.E.; Boudon, V. Total internal partition sums for the HITRAN2020 database. J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transf. 2021, 271, 107713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunker, P.R.; Jensen, P. Fundamentals of Molecular Symmetry; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2004; ISBN 0-7503-0941-5. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, R.J.H.; Rippon, D.M. The vapor-phase Raman spectra, Raman band contour analyses, Coriolis constants, and force constants of spherical-top molecules MX4 (M = Group IV element, X = F, Cl, Br, or I). J. Mol. Spectrosc. 1972, 44, 479–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Band | Empirical (Boudon et al. [22]) | Ab Initio (This Work) 1 | Final PES | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PES_I | PES_II | PES_II_Refined | ||

| ν2(E) | 264.219525 (32) | 261.462 | 263.582 | 264.2189 |

| ν4(F2) | 388.433276 (29) | 384.898 | 387.785 | 388.4330 |

| ν1(A1) | 800.66566 (11) | 795.882 | 799.989 | 800.6650 |

| ν3(F2) | 1031.544438 (65) | 1025.575 | 1030.904 | 1031.5439 |

| re(Si–F) | 1.5516985 (30) | 1.558392 | 1.552765 | 1.551592 |

| Derivative | F12a/AVTZ 1 | F12b/AVQZ | Empirical 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.4240 | 0.4243 | 0.42 ± 0.02 | |

| 0.3112 | 0.3108 | 0.30 ± 0.01 |

| Origin (cm−1) | Band | Region (cm−1) | N | Iν (cm/molecule) 1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| This Work | TFSiCaSDa | ||||

| (0010)–(0010)(F2) | 1–57 | 58,547 | 6.363 × 10−24 | ||

| (0000)–(0000)(A1) | 5–28 | 9055 | 1.540 × 10−24 | ||

| (0110)–(0110)(F2) | 2–57 | 23,864 | 1.142 × 10−24 | ||

| (0110)–(0110)(F1) | 2–57 | 21,379 | 1.087 × 10−24 | ||

| 124.175 | ν2 + ν4(F1)–2ν2(E) | 111–144 | 1444 | 2.015 × 10−23 | |

| 124.214 | ν4(F2)–ν2(E) | 106–147 | 11,554 | 2.650 × 10−22 | |

| 124.426 | ν2 + ν4(F2)–2ν2(E) | 109–139 | 1797 | 2.304 × 10−23 | |

| 125.907 | ν2 + ν4(F2)–2ν2(A1) | 111–145 | 3331 | 4.536 × 10−23 | |

| 263.204 | 2ν2(A1)–ν2(E) | 240–286 | 4290 | 1.408 × 10−21 | |

| 263.669 | 3ν2(E)–2ν2(A1) | 243–284 | 1590 | 4.030 × 10−22 | |

| 264.219 | ν2(E) | 236–290 | 9570 | 5.559 × 10−21 | |

| 264.646 | ν2 + ν4(F1)–ν4(F2) | 243–285 | 1739 | 4.123 × 10−22 | |

| 264.685 | 2ν2(E)–ν2(E) | 239–289 | 3746 | 1.168 × 10−21 | |

| 264.897 | ν2 + ν4(F2)–ν4(F2) | 244–285 | 2193 | 5.396 × 10−22 | |

| 387.522 | 2ν4(A1)–ν4(F2) | 359–418 | 99,620 | 6.361 × 10−19 | |

| 388.433 | ν4(F2) | 361–419 | 62,659 | 6.155 × 10−18 | 5.775 × 10−18 |

| 388.633 | 2ν4(F2)–ν4(F2) | 361–420 | 163,332 | 1.894 × 10−18 | |

| 388.860 | ν2 + ν4(F1)–ν2(E) | 361–419 | 69,260 | 1.353 × 10−18 | |

| 389.025 | 2ν4(E)–ν4(F2) | 361–422 | 97,931 | 1.132 × 10−18 | |

| 389.111 | ν2 + ν4(F2)–ν2(E) | 362–419 | 86,260 | 2.056 × 10−18 | |

| 389.536 | 2ν2 + ν4(F1)–2ν2(E) | 362–420 | 97,970 | 4.352 × 10−19 | |

| 389.576 | 2ν2 + ν4(F2)–2ν2(E) | 362–420 | 117,984 | 4.933 × 10−19 | |

| 391.057 | 2ν2 + ν4(F2)–2ν2(A1) | 362–420 | 43,194 | 4.553 × 10−19 | |

| 640.597 | ν2 + ν3(F2)–ν2 + ν4(F2) | 610–663 | 2118 | 2.864 × 10−23 | |

| 640.848 | ν2 + ν3(F2)–ν2 + ν4(F1) | 608–665 | 2713 | 4.091 × 10−23 | |

| 642.119 | ν2 + ν3(F1)–ν2 + ν4(F2) | 612–665 | 2447 | 3.172 × 10−23 | |

| 642.370 | ν2 + ν3(F1)–ν2 + ν4(F1) | 610–663 | 1579 | 2.206 × 10−23 | |

| 643.111 | ν3(F2)–ν4(F2) | 602–672 | 18,227 | 4.499 × 10−22 | |

| 653.330 | ν2 + ν4(F2) | 639–672 | 2825 | 3.494 × 10−23 | |

| 766.504 | ν2 + ν3(F2)–2ν2(A1) | 741–798 | 2937 | 7.475 × 10−22 | |

| 767.325 | ν3(F2)–ν2(E) | 737–803 | 11,353 | 4.964 × 10−21 | |

| 777.066 | 2ν4(F2) | 758–802 | 9678 | 5.829 × 10−21 | |

| 777.458 | 2ν4(E) | 760–800 | 3184 | 1.339 × 10−21 | |

| 777.856 | 3ν4(F1)–ν4(F2) | 761–798 | 3723 | 1.043 × 10−21 | |

| 778.296 | ν2 + 2ν4(F1)–ν2(E) | 763–799 | 3151 | 8.519 × 10−22 | |

| 1028.973 | ν3 + ν4(E)–ν4(F2) | 998–1062 | 58,012 | 2.899 × 10−18 | 2.477 × 10−18 |

| 1029.400 | 2ν2 + ν3(F1)–2ν2(E) | 996–1060 | 113,020 | 2.301 × 10−18 | |

| 1029.708 | ν2 + ν3(F2)–ν2(E) | 991–1065 | 85,877 | 9.991 × 10−18 | 1.116 × 10−17 |

| 1030.174 | ν3 + ν4(F2)–ν4(F2) | 997–1060 | 63,366 | 3.541 × 10−18 | 5.420 × 10−18 |

| 1030.341 | 2ν2 + ν3(F2)–2ν2(E) | 993–1063 | 211,923 | 3.007 × 10−18 | |

| 1030.445 | ν3 + ν4(F1)–ν4(F2) | 992–1064 | 121,231 | 6.275 × 10−18 | 7.309 × 10−18 |

| 1031.031 | ν3 + ν4(A1)–ν4(F2) | 1000–1062 | 63,240 | 3.031 × 10−18 | 1.624 × 10−18 |

| 1031.230 | ν2 + ν3(F1)–ν2(E) | 988–1068 | 88,859 | 9.425 × 10−18 | 9.985 × 10−18 |

| 1031.544 | ν3(F2) | 987–1068 | 53,957 | 3.491 × 10−17 | 3.860 × 10−17 |

| 1031.822 | 2ν2 + ν3(F2)–2ν2(A1) | 995–1064 | 56,483 | 2.460 × 10−18 | |

| 1051.287 | ν1 + ν3(F2)–2ν4(F2) | 1014–1038 | 1226 | 2.464 × 10−21 | |

| 1063.382 | ν1 + 2ν2(A1)–ν2(E) | 1033–1083 | 7167 | 3.339 × 10−21 | |

| 1064.650 | ν1 + ν2(E) | 1034–1088 | 12,965 | 1.183 × 10−20 | |

| 1064.982 | ν1 + 2ν2(E)–ν2(E) | 1035–1086 | 8762 | 2.862 × 10−21 | |

| 1066.009 | ν1 + ν2 + ν4(F1)–ν4(F2) | 1039–1083 | 3588 | 1.002 × 10−21 | |

| 1066.292 | ν1 + ν2 + ν4(F2)–ν4(F2) | 1039–1083 | 4119 | 1.252 × 10−21 | |

| 1166.658 | 3ν4(F2) | 1140–1192 | 13,478 | 1.793 × 10−20 | |

| 1190.005 | ν1 + ν4(F2) | 1161–1219 | 22,899 | 1.311 × 10−19 | |

| 1190.223 | ν1 + ν2 + ν4(F1)–ν2(E) | 1164–1217 | 18,203 | 3.133 × 10−20 | |

| 1190.506 | ν1 + ν2 + ν4(F2)–ν2(E) | 1164–1217 | 20,531 | 3.533 × 10−20 | |

| 1191.034 | ν1 + 2ν4(F2)–ν4(F2) | 1165–1217 | 28,004 | 3.722 × 10−20 | |

| 1293.927 | ν2 + ν3(F2) | 1248–1332 | 25,760 | 7.186 × 10−20 | |

| 1294.085 | 2ν2 + ν3(F1)–ν2(E) | 1253–1326 | 24,701 | 2.108 × 10−20 | |

| 1294.790 | ν2 + ν3 + ν4(F2)–ν4(F2) | 1255–1326 | 20,682 | 1.084 × 10−20 | |

| 1294.892 | ν2 + ν3 + ν4(F1)–ν4(F2) | 1254–1326 | 18,596 | 1.070 × 10−20 | |

| 1295.026 | 2ν2 + ν3(F2)–ν2(E) | 1251–1329 | 49,899 | 5.538 × 10−20 | |

| 1295.449 | ν2 + ν3(F1) | 1248–1329 | 20,422 | 2.746 × 10−20 | |

| 1417.406 | ν3 + ν4(E) | 1381–1439 | 7620 | 3.130 × 10−22 | |

| 1418.607 | ν3 + ν4(F2) | 1380–1441 | 9590 | 9.213 × 10−22 | |

| 1418.752 | ν3 + 2ν4(F2)–ν4(F2) | 1388–1448 | 14,347 | 2.304 × 10−22 | |

| 1418.878 | ν3 + ν4(F1) | 1392–1443 | 12,166 | 4.422 × 10−22 | |

| 1419.106 | ν2 + ν3 + ν4(F1)–ν2(E) | 1381–1439 | 10,396 | 3.187 × 10−22 | |

| 1439.920 | ν1 + ν3(F2)–ν4(F2) | 1415–1462 | 1888 | 2.241 × 10−23 | |

| 1454.442 | ν1 + ν2 + ν4(F1) | 1442–1471 | 488 | 5.751 × 10−24 | |

| 1454.725 | ν1 + ν2 + ν4(F2) | 1440–1472 | 3899 | 6.313 × 10−23 | |

| 1455.529 | ν1 + 2ν2 + ν4(F1)–ν2(E) | 1455–1470 | 219 | 2.253 × 10−24 | |

| 1455.577 | ν1 + 2ν2 + ν4(F2)–ν2(E) | 1444–1467 | 245 | 2.446 × 10−24 | |

| 1806.026 | ν3 + 3ν4(F1)–ν4(F2) | 1795–1836 | 2380 | 5.649 × 10−22 | |

| 1806.819 | ν3 + 3ν4(F2)–ν4(F2) | 1795–1836 | 1976 | 4.870 × 10−22 | |

| 1807.185 | ν3 + 2ν4(F2) | 1794–1837 | 8204 | 4.868 × 10−21 | |

| 1807.384 | ν2 + ν3 + 2ν4(F1)–ν2(E) | 1796–1837 | 2632 | 7.460 × 10−22 | |

| 1807.462 | ν2 + ν3 + 2ν4(F2)–ν2(E) | 1796–1835 | 3543 | 1.126 × 10−21 | |

| 1826.312 | ν1 + ν2 + ν3(F2)–ν2(E) | 1812–1836 | 11,704 | 2.802 × 10−20 | |

| 1827.820 | ν1 + ν2 + ν3(F1)–ν2(E) | 1812–1836 | 10,932 | 2.649 × 10−20 | |

| 1827.939 | ν1 + ν3 + ν4(F2)–ν4(F2) | 1814–1837 | 8106 | 9.321 × 10−21 | |

| 1828.179 | ν1 + ν3 + ν4(F1)–ν4(F2) | 1814–1837 | 14,154 | 1.621 × 10−20 | |

| 1828.353 | ν1 + ν3(F2) | 1814–1837 | 10,252 | 1.050 × 10−19 | |

| 1990.540 | 2ν1 + ν4(F2) | 1975–2006 | 1641 | 3.350 × 10−22 | |

| 2056.109 | ν2 + 2ν3(F1)–ν2(E) | 2009–2098 | 16,402 | 1.632 × 10−20 | |

| 2057.601 | ν2 + 2ν3(F2)–ν2(E) | 2009–2098 | 14,291 | 1.378 × 10−20 | |

| 2059.017 | 2ν3(F2) | 2007–2106 | 21,440 | 5.804 × 10−20 | |

| 2060.395 | 2ν3 + ν4(F2)–ν4(F2) | 2008–2098 | 22,522 | 1.007 × 10−20 | |

| 2060.865 | 2ν3 + ν4(F1)–ν4(F2) | 2008–2097 | 22,779 | 1.145 × 10−20 | |

| 2063.332 | 2ν3(E) | 2008–2107 | 17,304 | 2.371 × 10−20 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Egorov, O.; Rey, M. Elucidation of the Ro-Vibrational Band Structures in the Silicon Tetrafluoride Spectra from Accurate Ab Initio Calculations. Molecules 2025, 30, 4239. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30214239

Egorov O, Rey M. Elucidation of the Ro-Vibrational Band Structures in the Silicon Tetrafluoride Spectra from Accurate Ab Initio Calculations. Molecules. 2025; 30(21):4239. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30214239

Chicago/Turabian StyleEgorov, Oleg, and Michaël Rey. 2025. "Elucidation of the Ro-Vibrational Band Structures in the Silicon Tetrafluoride Spectra from Accurate Ab Initio Calculations" Molecules 30, no. 21: 4239. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30214239

APA StyleEgorov, O., & Rey, M. (2025). Elucidation of the Ro-Vibrational Band Structures in the Silicon Tetrafluoride Spectra from Accurate Ab Initio Calculations. Molecules, 30(21), 4239. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30214239