Unveiling the Untapped Potential of Bertagnini’s Salts in Microwave-Assisted Synthesis of Quinazolinones

Abstract

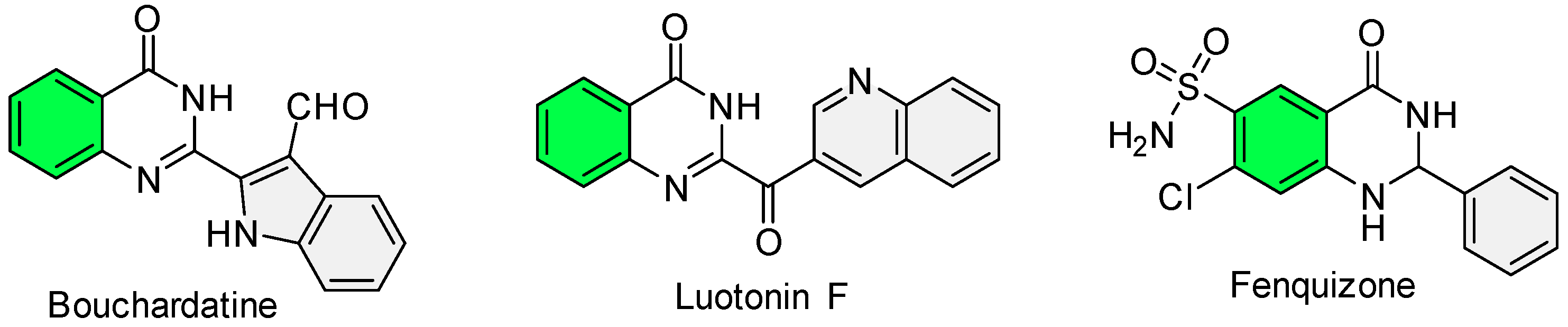

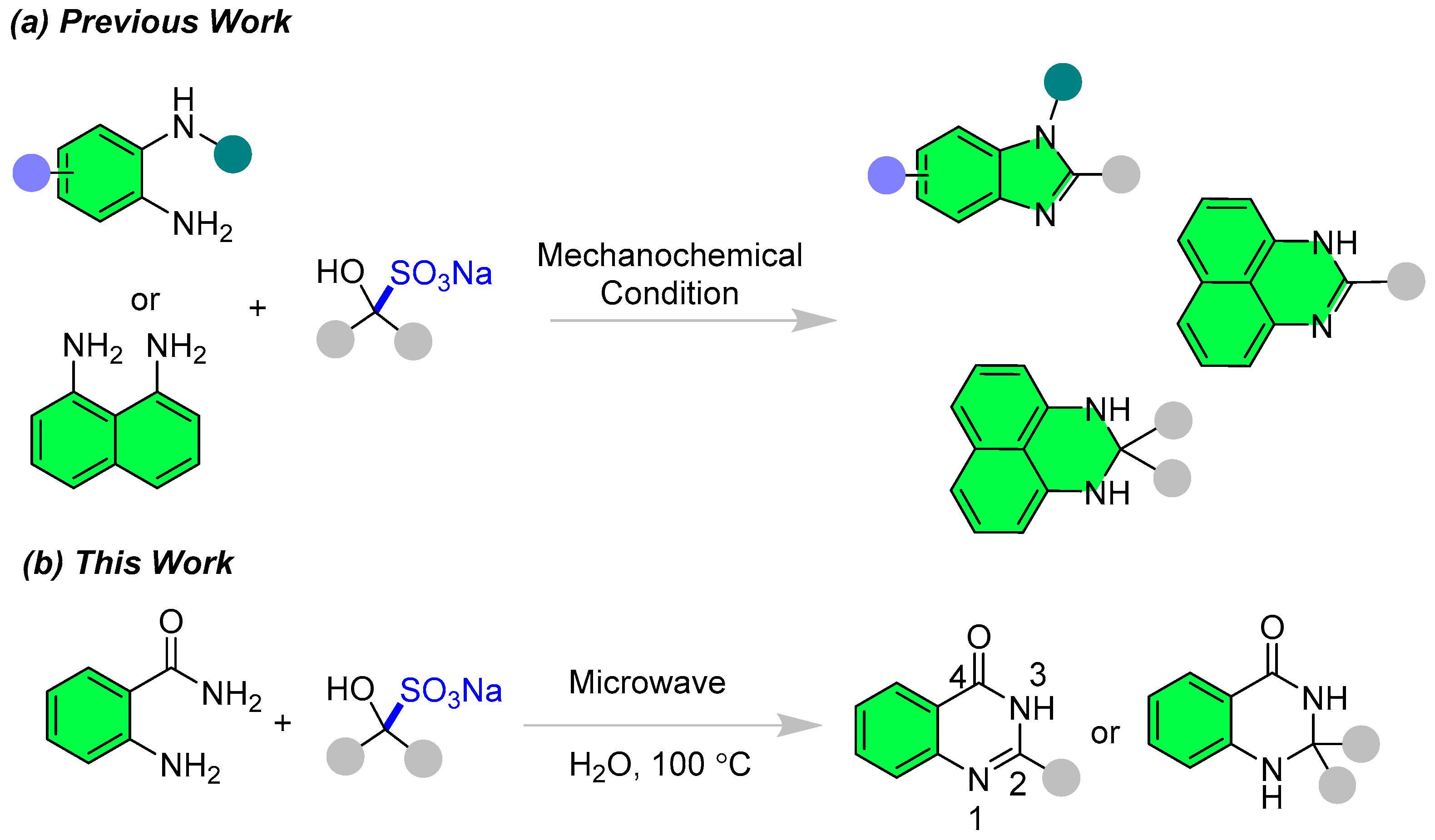

1. Introduction

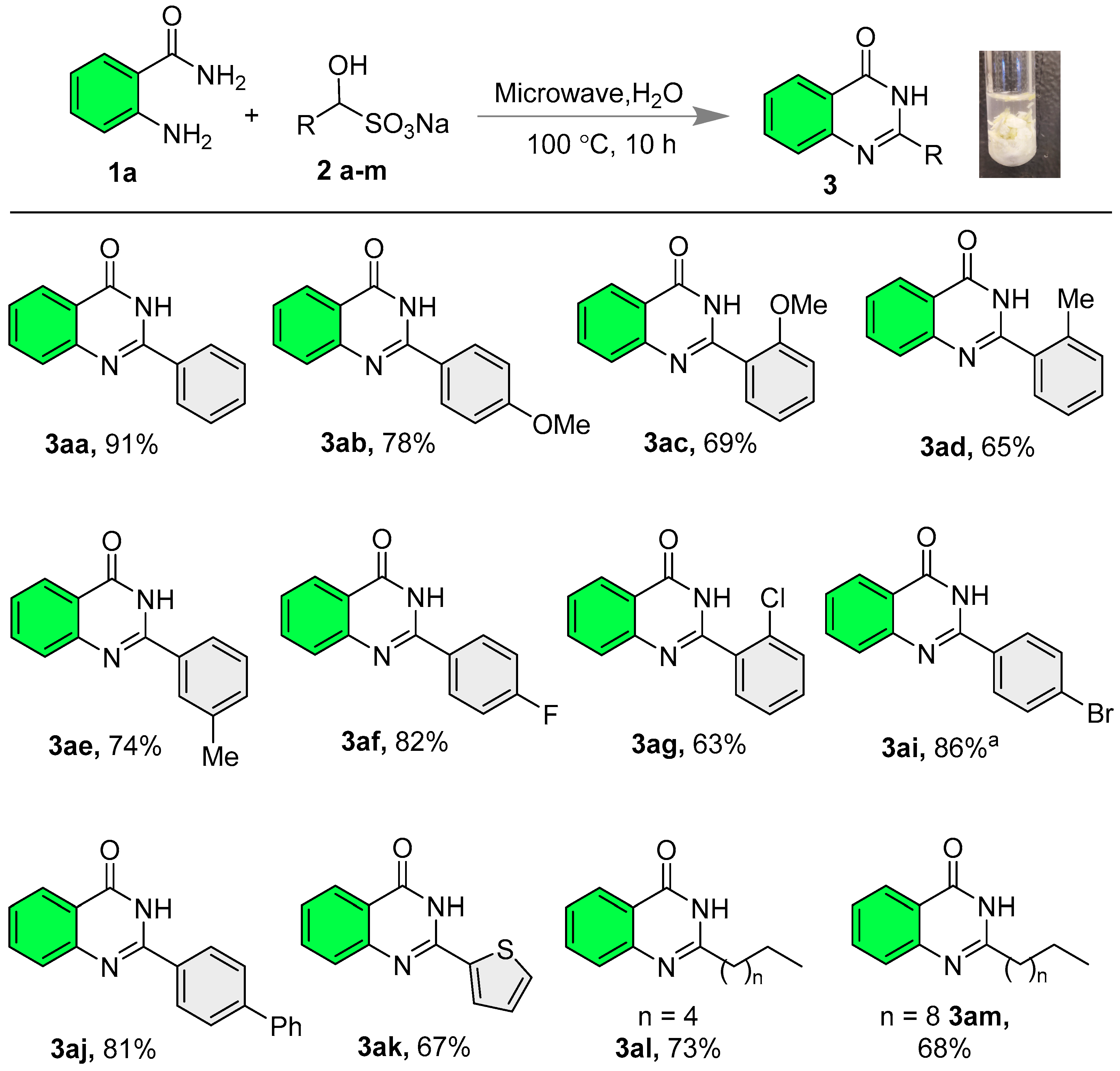

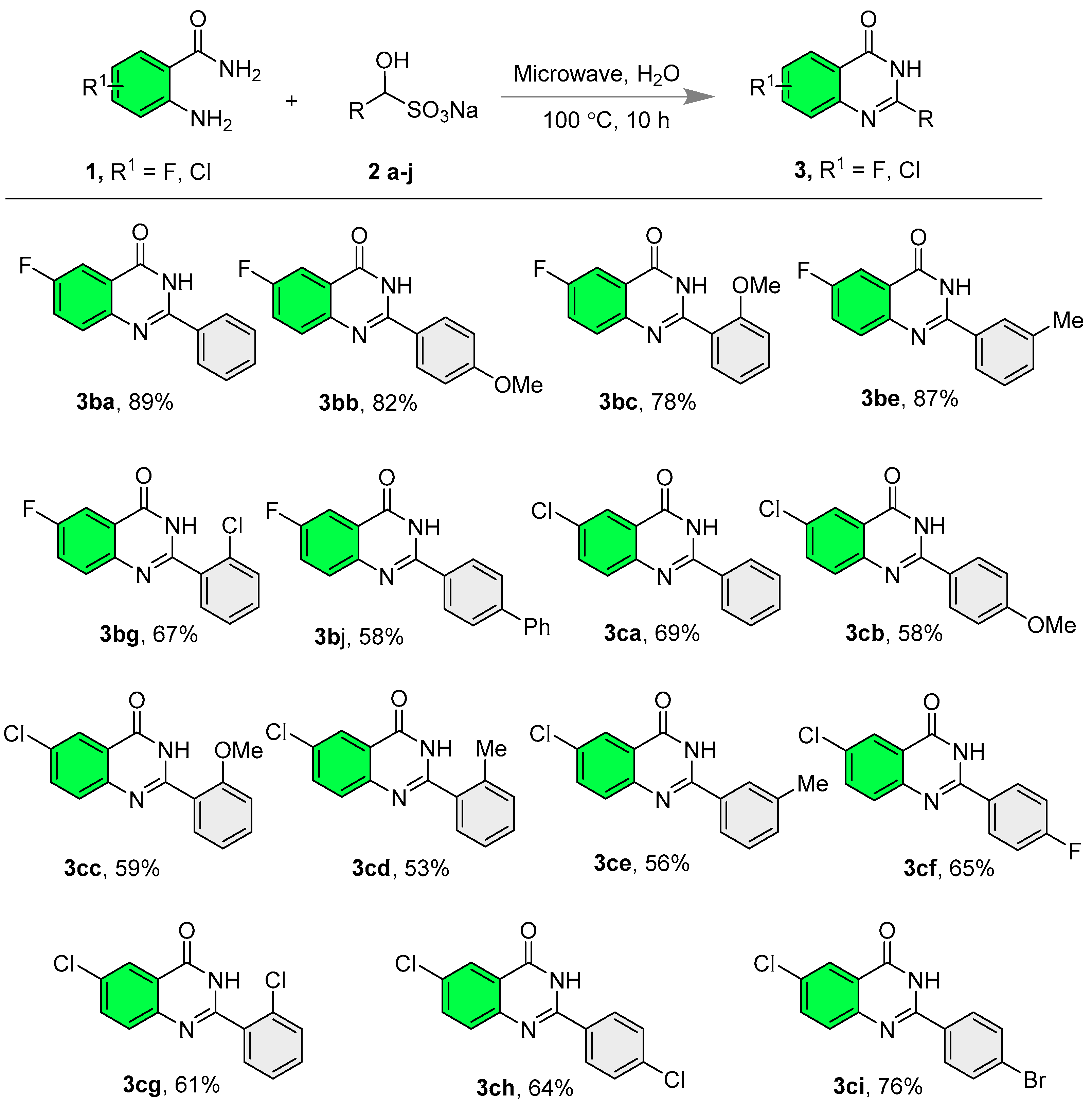

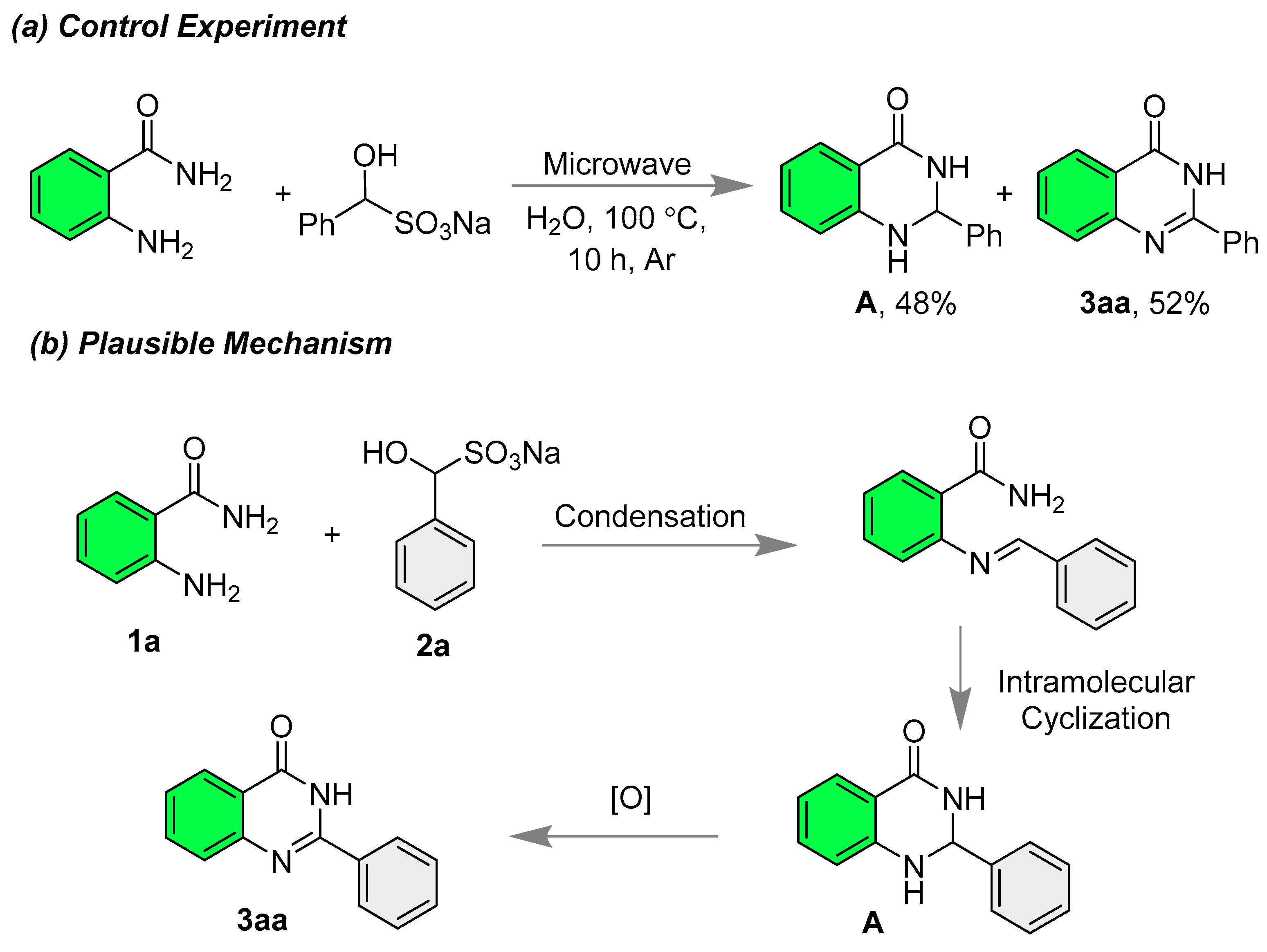

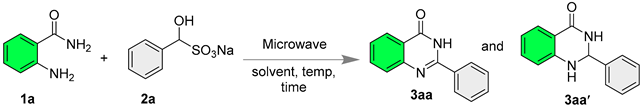

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Optimization

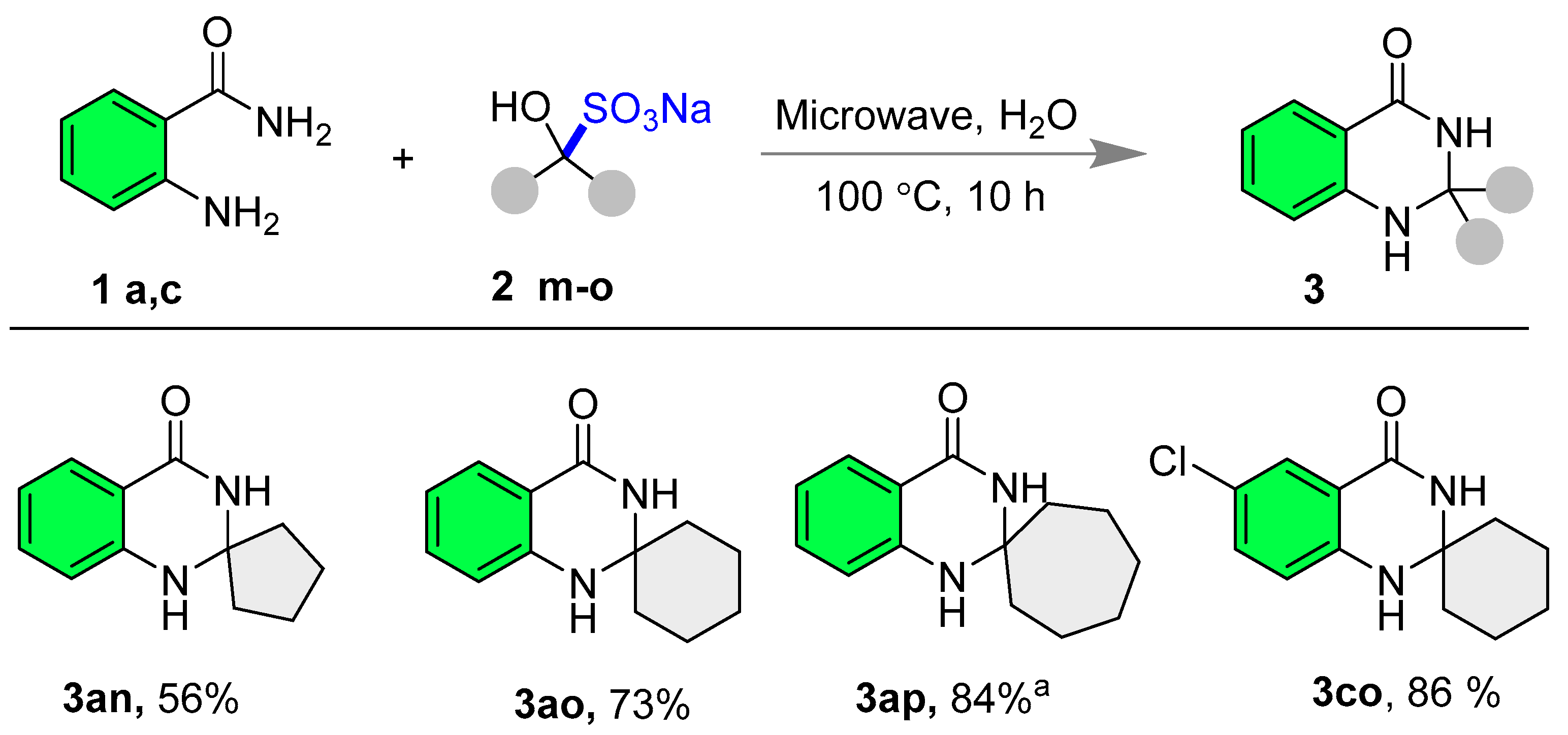

2.2. Synthesis of Quinazolinones

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

3.2. Procedure A. General Procedure for the Synthesis of 2-Phenylquinazolin-4(3H)-One

3.3. Characterization Data of the Synthesized Compounds

- 2-Phenylquinazolin-4(3H)-one (3aa) [21]: The title compound was synthesized according to general procedure A; White solid; Yield: 91% (101 mg); 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 12.53 (s, 1H), 8.20–8.13 (m, 3H), 7.82 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 7.74 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), and 7.60–7.48 (m, 4H); 13C NMR (151 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 162.3, 152.3, 148.8, 134.6, 132.7, 131.4, 128.6, 127.8, 127.5, 126.6, 125.9, and 121.0.

- 2-(4-Methoxyphenyl)quinazolin-4(3H)-one (3ab) [61]: The title compound was synthesized according to general procedure A; White solid; Yield: 78% (98.5 mg); 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 12.39 (s, 1H), 8.19 (d, J = 5.4 Hz, 2H), 8.13 (s, 1H), 7.80 (s, 1H), 7.70 (s, 1H), 7.47 (s, 1H), 7.08 (s, 2H), and 3.84 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (151 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 162.3, 161.9, 151.8, 148.9, 134.5, 129.4, 127.3, 126.1, 125.8, 124.8, 120.7, 113.9, and 55.4.

- 2-(2-Methoxyphenyl)quinazolin-4(3H)-one (3ac) [62]: The title compound was synthesized according to general procedure A; White solid; Yield: 69% (87 mg); 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 12.08 (s, 1H), 8.15 (dd, J = 7.8, 1.2 Hz, 1H), 7.85–7.79 (m, 1H), 7.71 (dd, J = 12.0, 4.8 Hz, 2H), 7.56–7.51 (m, 2H), 7.19 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.10 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), and 3.86 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (151 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 161.3, 157.2, 152.4, 148.9, 134.4, 132.2, 130.5, 127.3, 126.6, 125.8, 122.6, 120.9, 120.5, 111.9, and 55.8.

- 2-(o-Tolyl)quinazolin-4(3H)-one (3ad) [63]: The title compound was synthesized according to general procedure A; White solid; Yield: 65% (77 mg); 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 12.43 (s, 1H), 8.17 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.83 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 7.69 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.54 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 7.53–7.49 (m, 1H), 7.43 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 7.36–7.30 (m, 2H), and 2.39 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (151 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 161.8, 154.4, 148.7, 136.1, 134.4, 134.2, 130.5, 129.9, 129.1, 127.4, 126.6, 125.8, 125.7, 120.9, and 19.5.

- 2-(m-Tolyl)quinazolin-4(3H)-one (3ae) [23]: The title compound was synthesized according to general procedure A; White solid; Yield: 74% (88 mg); 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 12.45 (s, 1H), 8.15 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 8.02 (s, 1H), 7.97 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.85–7.81 (m, 1H), 7.74 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.54–7.49 (m, 1H), 7.45–7.37 (m, 2H), and 2.40 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (151 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 162.2, 152.4, 148.8, 137.9, 134.6, 132.7, 132.0, 128.5, 128.3, 127.5, 126.5, 125.9, 124.9, 120.9, and 20.9.

- 2-(4-Fluorophenyl)quinazolin-4(3H)-one (3af) [64]: The title compound was synthesized according to general procedure A; White solid; Yield: 83% (99.5 mg); 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 12.55 (s, 1H), 8.27–8.22 (m, 2H), 8.15 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.82 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 7.72 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.51 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), and 7.38 (t, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (151 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 164.1 (d, 1JC-F = 249.4 Hz), 162.2, 151.4, 148.7, 134.6, 130.4 (d, 3JC-F = 9.0 Hz), 129.2 (d, 4JC-F = 2.5 Hz), 127.5, 126.6, 125.9, 120.9, and 115.6 (d, 2JC-F = 21.9 Hz).

- 2-(2-Chlorophenyl)quinazolin-4(3H)-one (3ag) [65]: The title compound was synthesized according to general procedure A; White solid; Yield: 63% (81 mg); 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 12.65 (s, 1H), 8.18 (dd, J = 7.8, 1.2 Hz, 1H), 7.88–7.82 (m, 1H), 7.71 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.67 (dd, J = 7.8, 1.2 Hz, 1H), 7.63–7.60 (m, 1H), 7.58–7.55 (m, 2H), and 7.50 (td, J = 7.8, 1.2 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (151 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 161.5, 152.3, 148.5, 134.6, 133.8, 131.6, 131.5, 130.9, 129.6, 127.4, 127.2, 127.1, 125.9, and 121.2.

- 2-(4-Bromophenyl)quinazolin-4(3H)-one (3ai) [21]: The reaction was performed in DMSO solvent and reaction mixture was poured into water to get the solid precipitate. Further crude product was washed with excess water to obtain the pure product. White solid; Yield: 86% (129 mg); 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 12.60 (s, 1H), 8.15 (dd, J = 7.8, 1.2 Hz, 1H), 8.13 (s, 1H), 8.11 (s, 1H), 7.86–7.81 (m, 1H), 7.76 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H), 7.75 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H), 7.73 (s, 1H), and 7.55–7.51 (m, 1H); 13C NMR (151 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 162.2, 151.5, 148.5, 134.7, 131.9, 131.6, 129.8, 127.4, 126.8, 125.9, 125.2, and 120.9.

- 2-([1,1′-Biphenyl]-4-yl)quinazolin-4(3H)-one (3aj) [23]: The title compound was synthesized according to general procedure A; White solid; Yield: 81% (120.5 mg); 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 12.58 (s, 1H), 8.30 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H), 8.17 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.84 (t, J = 9.0 Hz, 3H), 7.76 (d, J = 3.6 Hz, 3H), 7.56–7.47 (m, 3H), and 7.42 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (151 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 162.3, 151.9, 148.7, 142.9, 138.9, 134.6, 131.5, 129.1, 128.4, 128.2, 127.4, 126.8, 126.7, 126.6, 125.9, and 120.9.

- 2-(Thiophen-2-yl)quinazolin-4(3H)-one (3ak) [66]: The title compound was synthesized according to general procedure A; White solid; Yield: 67% (76 mg); 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 12.48 (s, 1H), 8.12 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.99 (s, 1H), 7.80 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.68 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 7.63 (d, J = 2.7 Hz, 1H), 7.48 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), and 6.74 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (151 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 161.6, 148.7, 146.6, 146.1, 144.0, 134.6, 127.2, 126.4, 125.9, 121.2, 114.5, and 112.5.

- 2-Hexylquinazolin-4(3H)-one (3al) [67]: The title compound was synthesized according to general procedure A; White solid; Yield: 73% (84 mg); 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 12.14 (s, 1H), 8.07 (dd, J = 7.8, 1.2 Hz, 1H), 7.77–7.72 (m, 1H), 7.58 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.46–7.41 (m, 1H), 2.60–2.55 (m, 2H), 1.73–1.66 (m, 2H), 1.31–1.26 (m, 2H), 1.27–1.19 (m, 4H), and 0.86–0.79 (m, 3H); 13C NMR (151 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 161.9, 157.6, 149.0, 134.3, 126.8, 125.9, 125.7, 120.8, 34.6, 30.9, 28.2, 26.8, 21.9, and 13.9.

- 2-Decylquinazolin-4(3H)-one (3am) [68]: The title compound was synthesized according to general procedure A; White solid; Yield: 68% (97 mg); 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 12.13 (s, 1H), 8.07 (dd, J = 7.8, 1.2 Hz, 1H), 7.78–7.73 (m, 1H), 7.57 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.46–7.41 (m, 1H), 2.61–2.54 (m, 2H), 1.73–1.66 (m, 2H), 1.33–1.25 (m, 5H), 1.25–1.14 (m, 9H), and 0.84–0.81 (m, 3H); 13C NMR (151 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 161.9, 157.6, 148.9, 134.3, 126.8, 125.9, 125.7, 120.8, 34.5, 31.3, 28.9, 28.9, 28.7, 28.5, 26.8, 22.1, and 13.9.

- 6-Fluoro-2-phenylquinazolin-4(3H)-one (3ba) [69]: The title compound was synthesized according to general procedure A; White solid; Yield: 89% (107 mg); 89%; 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 12.65 (s, 1H), 8.17 (s, 1H), 8.16–8.15 (m, 1H), 7.84–7.82 (m, 1H), 7.81 (d, J = 5.6 Hz, 1H), 7.72 (td, J = 8.4, 3.0 Hz, 1H), 7.59 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), and 7.56–7.53 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (151 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 161.6, 159.9 (d, 1JC-F = 245.5 Hz), 151.8, 145.6, 132.6, 131.4, 130.3 (d, 3JC-F = 8.3 Hz), 128.6, 127.7, 123.1 (d, 2JC-F = 24.1 Hz), 122.2 (d, 3JC-F = 8.6 Hz), and 110.5 (d, 2JC-F = 23.3 Hz).

- 6-Fluoro-2-(4-methoxyphenyl)quinazolin-4(3H)-one (3bb) [19]: The title compound was synthesized according to general procedure A; White solid; Yield: 82% (111 mg); 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 12.51 (s, 1H), 8.17 (s, 2H), 7.83–7.66 (m, 3H), 7.09 (s, 2H), and 3.85 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (151 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 161.9, 159.7 (d, 1JC-F = 245.7 Hz), 151.5, 145.8, 130.0, 129.4, 124.6, 123.1, 122.9, 121.8 (d, 3JC-F = 10.6 Hz), 114.0, 110.4 (d, 2JC-F = 23.4 Hz), and 55.5.

- 6-Fluoro-2-(2-methoxyphenyl)quinazolin-4(3H)-one (3bc) [19]: The title compound was synthesized according to general procedure A; White solid; Yield: 78% (106 mg); 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 12.22 (s, 1H), 7.82 (dd, J = 8.4, 3.0 Hz, 1H), 7.79–7.76 (m, 1H), 7.73–7.70 (m, 1H), 7.69–7.67 (m, 1H), 7.56–7.52 (m, 1H), 7.19 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.09 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), and 3.86 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (151 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 160.7, 159.9 (d, 1JC-F = 245.3 Hz), 157.1, 151.9, 145.9, 132.3, 130.4, 130.2 (d, 3JC-F = 8.3 Hz), 122.9 (d, 2JC-F = 24.0 Hz), 122.5, 122.2 (d, 3JC-F = 8.4 Hz), 120.4, 111.9, 110.4 (d, 2JC-F = 23.3 Hz), and 55.8.

- 6-Fluoro-2-(m-tolyl)quinazolin-4(3H)-one (3be) The title compound was synthesized according to general procedure A; White solid; Yield: 87% (110 mg); 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 12.58 (s, 1H), 8.00 (s, 1H), 7.95 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 1H), 7.81 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 2H), 7.72 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H), 7.46–7.37 (m, 2H), and 2.40 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (151 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 161.7, 159.9 (d, 1JC-F = 244.8 Hz), 151.9, 145.6, 137.9, 132.5, 132.0, 130.3, 130.2 (d, 4JC-F = 4.9 Hz), 128.4 (d, 3JC-F = 7.9 Hz), 124.9, 123.1 (d, 2JC-F = 24.2 Hz), 122.2 (d, 3JC-F = 8.7 Hz), and 110.5 (d, 2JC-F = 23.2 Hz); FTIR max = 3116, 3075, 1675, 1571, 1484, 1294, 879 cm−1; HRMS: calculated for C15H12FN2O: 255.0928 [M+H]+; found: 255.0939.

- 2-(2-Chlorophenyl)-6-fluoroquinazolin-4(3H)-one (3bg): The title compound was synthesized according to general procedure A; White solid; Yield: 67% (92 mg); 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 12.76 (s, 1H), 7.85 (dd, J = 8.4, 3.0 Hz, 1H), 7.80 (dd, J = 8.4, 4.8 Hz, 1H), 7.74 (td, J = 8.4, 3.0 Hz, 1H), 7.67 (dd, J = 7.8, 1.8 Hz, 1H), 7.63–7.60 (m, 1H), 7.57 (td, J = 7.8, 1.8 Hz, 1H), and 7.50 (td, J = 7.8, 1.2 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (151 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 160.9, 160.3 (d, 1JC-F = 246.0 Hz), 151.8, 145.4, 133.6, 131.7, 131.5, 130.9, 130.4 (d, 3JC-F = 10.0 Hz), 129.6, 127.3, 123.1 (d, 2JC-F = 24.1 Hz), 122.5 (d, 3JC-F = 8.4 Hz), and 110.6 (d, 2JC-F = 23.3 Hz); FTIR max = 3045, 2977, 1679, 1604, 1481, 927, 763 cm−1; HRMS: calculated for C14H9ClFN2O: 275.0387 [M+H]+; found: 275.0396.

- 2-([1,1′-Biphenyl]-4-yl)-6-fluoroquinazolin-4(3H)-one (3bj): The title compound was synthesized according to general procedure A; White solid; Yield: 58% (92 mg); 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 12.70 (s, 1H), 8.29 (s, 2H), 7.86 (s, 4H), 7.78 (s, 3H), and 7.55–7.49 (m, 3H); 13C NMR (151 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 161.7, 159.9 (d, 1JC-F = 246.1 Hz), 157.4, 154.1, 151.5, 145.7, 142.9, 138.9, 130.3, 129.1, 128.4, 128.2, 126.8 (d, 3JC-F = 13.3 Hz), 123.1 (d, 2JC-F = 23.5 Hz), 122.2, and 110.5 (d, 2JC-F = 22.4 Hz); FTIR max = 3029, 2952, 1660, 1596, 1481, 1301, 836 cm−1; HRMS: calculated for C20H14FN2O: 317.1090 [M+H]+; found: 317.1103.

- 6-Chloro-2-phenylquinazolin-4(3H)-one (3ca) [21]: The title compound was synthesized according to general procedure A; White solid; Yield: 69% (89 mg); 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 12.71 (s, 1H), 8.18 (s, 2H), 8.09 (s, 1H), 7.86 (s, 1H), 7.77 (s, 1H), 7.60 (s, 1H), and 7.56 (s, 2H); 13C NMR (151 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 161.3, 152.9, 147.5, 134.7, 132.4, 131.6, 130.8, 129.7, 128.6, 127.8, 124.9, and 122.2.

- 6-Chloro-2-(4-methoxyphenyl)quinazolin-4(3H)-one (3cb) [70]: The title compound was synthesized according to general procedure A; White solid; Yield: 58% (83 mg); 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 12.56 (s, 1H), 8.19 (s, 1H), 8.17 (s, 1H), 8.06 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H), 7.83 (dd, J = 8.4, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 7.72 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.09 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), and 3.85 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (151 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 162.0, 161.3, 152.4, 147.7, 134.6, 130.2, 129.6, 129.5, 124.8, 124.5, 121.9, 114.0, and 55.5.

- 6-Chloro-2-(2-methoxyphenyl)quinazolin-4(3H)-one (3cc) [71]: The title compound was synthesized according to general procedure A; White solid; Yield: 59% (85 mg); 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 12.27 (s, 1H), 8.08 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H), 7.85 (dd, J = 8.4, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 7.73 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.70 (dd, J = 7.8, 1.7 Hz, 1H), 7.56–7.51 (m, 1H), 7.20 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.09 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), and 3.86 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (151 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 160.3, 157.1, 152.8, 147.8, 134.5, 132.4, 130.8, 130.5, 129.6, 124.8, 122.4, 122.2, 120.4, 111.9, and 55.8.

- 6-Chloro-2-(o-tolyl)quinazolin-4(3H)-one (3cd) [72]: The title compound was synthesized according to general procedure A; White solid; Yield: 53% (72 mg); 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 12.61 (s, 1H), 8.10 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H), 7.86 (dd, J = 8.4, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 7.71 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.51 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 7.44 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 7.35 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.32 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), and 2.38 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (151 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 160.8, 154.9, 147.4, 136.2, 134.5, 133.9, 130.8, 130.6, 130.0, 129.6, 129.1, 125.7, 124.8, 122.2, and 19.5.

- 6-Chloro-2-(m-tolyl)quinazolin-4(3H)-one (3ce): The title compound was synthesized according to general procedure A; White solid; Yield: 56% (76 mg); 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 12.63 (s, 1H), 8.08 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H), 8.01 (s, 1H), 7.96 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 7.85 (dd, J = 8.4, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 7.76 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.45–7.40 (m, 2H), and 2.41 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (151 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 161.3, 152.9, 137.9, 134.8, 134.7, 132.9, 132.4, 132.2, 130.7, 129.7, 128.5, 128.4, 124.9, 124.9, and 20.9; FTIR max = 3023, 2925, 1671, 1579, 1467, 1309, 842 cm−1; HRMS: calculated for C15H12ClN2O: 271.0638 [M+H]+; found: 271.0649.

- 6-Chloro-2-(4-fluorophenyl)quinazolin-4(3H)-one (3cf) [73]: The title compound was synthesized according to general procedure A; White solid; Yield: 65% (89 mg); 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 12.73 (s, 1H), 8.26–8.21 (m, 2H), 8.08 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H), 7.85 (dd, J = 8.4, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 7.75 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), and 7.39 (t, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (151 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 164.1 (d, 1JC-F = 249.9 Hz), 161.3, 151.9, 147.4, 134.7, 130.8, 130.5 (d, 3JC-F = 9.0 Hz), 129.7, 128.9 (d, 4JC-F = 2.8 Hz), 124.9, 122.1, and 115.7 (d, 2JC-F = 22.0 Hz).

- 6-Chloro-2-(2-chlorophenyl)quinazolin-4(3H)-one (3cg) [73]: The title compound was synthesized according to general procedure A; White solid; Yield: 61% (89 mg); 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 12.82 (s, 1H), 8.12 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H), 7.89 (dd, J = 8.4, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 7.75 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.67 (dd, J = 7.2, 1.2 Hz, 1H), 7.62 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.58 (td, J = 7.2, 1.2 Hz, 1H), and 7.50 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (151 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 160.5, 152.7, 147.3, 134.7, 133.5, 131.8, 131.4, 131.4, 130.9, 129.7, 129.6, 127.2, 124.9, and 122.5.

- 6-Chloro-2-(4-chlorophenyl)quinazolin-4(3H)-one (3ch) [73]: The title compound was synthesized according to general procedure A; White solid; Yield: 64% (93 mg); 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 12.67 (s, 1H), 8.20 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H), 8.09 (s, 1H), 7.85 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.76 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), and 7.62 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (151 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 161.3, 152.3, 141.4, 139.2, 136.3, 134.4, 129.8, 129.5, 128.5, 127.6, 124.7, and 122.2.

- 2-(4-Bromophenyl)-6-chloroquinazolin-4(3H)-one (3ci) [74]: The title compound was synthesized according to general procedure A; White solid; Yield: 76% (127 mg); 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 12.66 (s, 1H), 8.14 (s, 1H), 8.12 (s, 1H), 8.08 (d, J = 2.5 Hz, 1H), 7.84 (dd, J = 8.7, 2.5 Hz, 1H), and 7.76 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (151 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 161.4, 152.2, 134.4, 131.4, 131.4, 130.6, 129.7, 129.4, 128.8, 125.1, 124.7, and 122.2.

- 1′H-spiro[cyclopentane-1,2′-quinazolin]-4′(3′H)-one (3an) [75] The title compound was synthesized according to general procedure A; White solid; Yield: 56% (56.6 mg); 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 8.07 (s, 1H), 7.57 (dd, J = 7.8, 1.2 Hz, 1H), 7.25–7.14 (m, 1H), 6.72 (s, 1H), 6.69 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 6.63 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 1.83–1.75 (m, 4H), and 1.68–1.63 (m, 4H); 13C NMR (151 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 163.5, 147.5, 133.0, 127.3, 116.6, 114.6, 114.3, 77.1, 39.3, and 21.9.

- 1′H-spiro[cyclohexane-1,2′-quinazolin]-4′(3′H)-one (3ao) [75]: The title compound was synthesized according to general procedure A; White solid; Yield: 73% (79 mg); 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 7.90 (s, 1H), 7.56 (dd, J = 7.8, 1.2 Hz, 1H), 7.24–7.16 (m, 1H), 6.80 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 6.62 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 6.60 (d, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H), 1.78–1.67 (m, 2H), 1.65–1.58 (m, 2H), 1.58–1.51 (m, 4H), 1.46–1.36 (m, 1H), and 1.29–1.20 (m, 1H); 13C NMR (151 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 163.2, 146.8, 133.1, 127.1, 116.5, 114.6, 114.5, 67.8, 37.2, 24.6, and 20.9.

- 1′H-spiro[cycloheptane-1,2′-quinazolin]-4′(3′H)-one (3ap) [75]: The reaction was performed in DMSO solvent, and the reaction mixture was poured into water to get the solid precipitate. Further crude product was washed with excess water to obtain the pure product. White solid; Yield: 84% (97 mg); 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 8.00 (s, 1H), 7.55 (dd, J = 7.8, 1.2 Hz, 1H), 7.23–7.16 (m, 1H), 6.71 (s, 1H), 6.70 (s, 1H), 6.62–6.58 (m, 1H), 1.92–1.81 (m, 4H), and 1.51 (s, 8H); 13C NMR (151 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 162.9, 146.7, 133.1, 127.1, 116.3, 114.4, 114.3, 71.9, 41.0, 29.2, and 20.9.

- 6′-Chloro-1′H-spiro[cyclohexane-1,2′-quinazolin]-4′(3′H)-one (3co) [75]: The title compound was synthesized according to general procedure A; White solid; Yield: 86% (108 mg); 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 8.10 (s, 1H), 7.49 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H), 7.24 (dd, J = 8.4, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 6.87–6.78 (m, 2H), 1.78–1.70 (m, 2H), 1.63–1.57 (m, 2H), 1.57–1.50 (m, 4H), 1.47–1.38 (m, 1H), and 1.27–1.19 (m, 1H); 13C NMR (151 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 162.0, 145.5, 132.9, 126.2, 120.1, 116.6, 115.6, 68.0, 37.1, 24.5, and 20.8.

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Arcadi, A.; Morlacci, V.; Palombi, L. Synthesis of Nitrogen-Containing Heterocyclic Scaffolds through Sequential Reactions of Aminoalkynes with Carbonyls. Molecules 2023, 28, 4725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majee, S.; Shilpa; Sarav, M.; Banik, B.K.; Ray, D. Recent Advances in the Green Synthesis of Active N-Heterocycles and Their Biological Activities. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, H.; Xu, F. Advances in the synthesis of nitrogen-containing heterocyclic compounds by in situ benzyne cycloaddition. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 8238–8253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Z.; Bottari, G.; Barta, K. Supercritical methanol as solvent and carbon source in the catalytic conversion of 1,2-diaminobenzenes and 2-nitroanilines to benzimidazoles. Green Chem. 2015, 17, 5172–5181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullaha, M.; Mohammed, S.; Ali, M.; Kumar, A.; Vishwakarma, R.A.; Bharate, S.B. Discovery of Quinazolin-4(3 H)-ones as NLRP3 Inflammasome Inhibitors: Computational Design, Metal-Free Synthesis, and in Vitro Biological Evaluation. J. Org. Chem. 2019, 84, 5129–5140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J.; Chen, L.; Fan, J.; Cao, W.; Zeng, G.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Deng, X. Dual-targeting Rutaecarpine-NO donor hybrids as novel anti-hypertensive agents by promoting release of CGRP. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 168, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gatadi, S.; Lakshmi, T.V.; Nanduri, S. 4(3H)-Quinazolinone derivatives: Promising antibacterial drug leads. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 170, 157–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, S.; Feng, S.; Zhang, W.; Mou, H.; Tang, S.; Zhou, H.; Luo, J.; Wei, X.; Zhu, Y.; Wu, R.; et al. Design, synthesis and antibacterial activity of quinazolinone derivatives containing glycosides. Mol. Cryst. Liq. Cryst. 2024, 768, 72–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Yang, Z.-Y.; Hour, M.-J.; Kuo, S.-C.; Xia, P.; Bastow, K.F.; Nakanishi, Y.; Nampoothiri, P.; Hackl, T.; Hamel, E.; et al. Antitumor Agents. Part 204:1 Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of Substituted 2-Aryl Quinazolinones. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2001, 11, 1193–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noser, A.A.; El-Barbary, A.A.; Salem, M.M.; El Salam, H.A.A.; shahien, M. Synthesis and molecular docking simulations of novel azepines based on quinazolinone moiety as prospective antimicrobial and antitumor hedgehog signaling inhibitors. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 3530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakumar, C.; Lamba, P.; Pran Kishore, D.; Lakshmi Narayana, B.; Venkat Rao, K.; Rajwinder, K.; Raghuram Rao, A.; Shireesha, B.; Narsaiah, B. Synthesis, anti-inflammatory evaluation and docking studies of some new fluorinated fused quinazolines. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2010, 45, 4904–4913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.J.; Lee, S.J.; Lee, S.; Chae, S.; Han, M.D.; Mar, W.; Nam, K.W. Rutecarpine ameliorates bodyweight gain through the inhibition of orexigenic neuropeptides NPY and AgRP in mice. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2009, 389, 437–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.-R.; Carté, B.K.; Sidebottom, P.J.; Sek Yew, A.L.; Ng, S.-B.; Huang, Y.; Butler, M.S. Circumdatin G, a New Alkaloid from the Fungus Aspergillus ochraceus. J. Nat. Prod. 2001, 64, 125–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Hu, G.; Li, D.; Chen, J.; Li, Y.; Zhou, H.; Xie, Y. Synthesis and vasodilator effects of rutaecarpine analogues which might be involved transient receptor potential vanilloid subfamily, member 1 (TRPV1). Biorg. Med. Chem. 2009, 17, 2351–2359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.-H.; Hu, Y.-T.; Xu, S.-M.; Song, B.-B.; Yuan, H.; Zhao, D.-D.; Guo, S.-Y.; Jiang, Z.; Wei, L.-Y.; Rao, Y.; et al. Design and Synthesis of Bouchardatine Derivatives as a Novel AMP-Activated Protein Kinase Activator for the Treatment of Colorectal Cancer. J. Med. Chem. 2023, 66, 7387–7404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.-X.; Du, S.-S.; Wang, J.-R.; Chu, Q.-R.; Tang, C.; Zhang, Z.-J.; Yang, C.-J.; He, Y.-H.; Li, H.-X.; Wu, T.-L.; et al. Design, Synthesis, and Antifungal Evaluation of Luotonin A Derivatives against Phytopathogenic Fungi. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2021, 69, 14467–14477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarfraz, M.; Wang, C.; Sultana, N.; Ellahi, H.; Rehman, M.F.u.; Jameel, M.; Akhter, S.; Kanwal, F.; Tariq, M.I.; Xue, S. 2,3-Dihydroquinazolin-4(1H)-one as a New Class of Anti-Leishmanial Agents: A Combined Experimental and Computational Study. Crystals 2021, 12, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kshirsagar, U.; Rohokale, R. Advanced Synthetic Strategies for Constructing Quinazolinone Scaffolds. Synthesis 2016, 48, 1253–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zeng, L.Y.; Li, C.; Yang, F.; Qiu, F.; Liu, S.; Xi, B. “On-Water” Synthesis of Quinazolinones and Dihydroquinazolinones Starting from o-Bromobenzonitrile. Molecules 2018, 23, 2325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hakim Siddiki, S.M.A.; Kon, K.; Touchy, A.S.; Shimizu, K.-i. Direct synthesis of quinazolinones by acceptorless dehydrogenative coupling of o-aminobenzamide and alcohols by heterogeneous Pt catalysts. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2014, 4, 1716–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bera, S.K.; Bhanja, R.; Mal, P. DDQ in mechanochemical C–N coupling reactions. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2022, 18, 639–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bera, S.K.; Mal, P. Regiodivergent C–N Coupling of Quinazolinones Controlled by the Dipole Moments of Tautomers. Org. Lett. 2022, 24, 3144–3148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Jin, L.; Liu, Y.; Yang, G.; Wang, A.; Le, Z.; Jiang, G.; Xie, Z. Visible light-mediated synthesis of quinazolinones from benzyl bromides and 2-aminobenzamides without using any photocatalyst or additive. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2024, 22, 784–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhanja, R.; Bera, S.K.; Mal, P. Regioselective synthesis of phenanthridine-fused quinazolinones using a 9-mesityl-10-methylacridinium perchlorate photocatalyst. Chem. Commun. 2023, 59, 4455–4458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastas, P.; Eghbali, N. Green Chemistry: Principles and Practice. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010, 39, 301–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitanosono, T.; Masuda, K.; Xu, P.; Kobayashi, S. Catalytic Organic Reactions in Water toward Sustainable Society. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 679–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.J.; Chen, L. Organic chemistry in water. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2006, 35, 68–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russo, C.; Brunelli, F.; Tron, G.C.; Giustiniano, M. Visible-Light Photoredox Catalysis in Water. J. Org. Chem. 2023, 88, 6284–6293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortes-Clerget, M.; Yu, J.; Kincaid, J.R.A.; Walde, P.; Gallou, F.; Lipshutz, B.H. Water as the reaction medium in organic chemistry: From our worst enemy to our best friend. Chem. Sci. 2021, 12, 4237–4266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, M.O.; Li, C.J. Green chemistry oriented organic synthesis in water. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 1415–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, A.; Dubey, P.; Sagar, R. Exploiting Microwave-Assisted Organic Synthesis (MAOS) for Accessing Bioactive Scaffolds. Curr. Org. Chem. 2021, 25, 2378–2456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varma, R.S. Solvent-free organic syntheses. using supported reagents and microwave irradiation. Green Chem. 1999, 1, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henary, M.; Kananda, C.; Rotolo, L.; Savino, B.; Owens, E.A.; Cravotto, G. Benefits and applications of microwave-assisted synthesis of nitrogen containing heterocycles in medicinal chemistry. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 14170–14197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polshettiwar, V.; Varma, R.S. Microwave-Assisted Organic Synthesis and Transformations using Benign Reaction Media. Acc. Chem. Res. 2008, 41, 629–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lidström, P.; Tierney, J.; Wathey, B.; Westman, J. Microwave assisted organic synthesis—A review. Tetrahedron 2001, 57, 9225–9283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawande, M.B.; Shelke, S.N.; Zboril, R.; Varma, R.S. Microwave-Assisted Chemistry: Synthetic Applications for Rapid Assembly of Nanomaterials and Organics. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014, 47, 1338–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martina, K.; Cravotto, G.; Varma, R.S. Impact of Microwaves on Organic Synthesis and Strategies toward Flow Processes and Scaling Up. J. Org. Chem. 2021, 86, 13857–13872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polshettiwar, V.; Varma, R.S. Aqueous microwave chemistry: A clean and green synthetic tool for rapid drug discovery. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2008, 37, 1546–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geetanjali; Singh, R. Microwave-assisted Organic Synthesis in Water. Curr. Microw. Chem. 2021, 8, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, G.; Khanna, A.; Mishra, V.K.; Sagar, R. Recent developments on microwave-assisted organic synthesis of nitrogen- and oxygen-containing preferred heterocyclic scaffolds. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 32858–32892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardi, M.; Bonacci, S.; Herrera Cano, N.; Oliverio, M.; Procopio, A. The Highly Efficient Synthesis of 1,2-Disubstituted Benzimidazoles Using Microwave Irradiation. Molecules 2022, 27, 1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meera, G.; Rohit, K.R.; Saranya, S.; Anilkumar, G. Microwave assisted synthesis of five membered nitrogen heterocycles. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 36031–36041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majumder, A.; Gupta, R.; Jain, A. Microwave-assisted synthesis of nitrogen-containing heterocycles. Green Chem. Lett. Rev. 2013, 6, 151–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranu, B.C.; Hajra, A.; Dey, S.S.; Jana, U. Efficient microwave-assisted synthesis of quinolines and dihydroquinolines under solvent-free conditions. Tetrahedron 2003, 59, 813–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranu, B.C.; Hajra, A.; Jana, U. Microwave-assisted simple synthesis of quinolines from anilines and alkyl vinyl ketones on the surface of silica gel in the presence of indium(III) chloride. Tetrahedron Lett. 2000, 41, 531–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, A.; Bhakta, S.; Ghosh, T. Microwave-assisted synthesis of bioactive heterocycles: An overview. Tetrahedron 2022, 126, 133085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, B.; Kaur, G. Microwave Assisted Catalyst-free Synthesis of Bioactive Heterocycles. Curr. Microw. Chem. 2020, 7, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, Q.; Torabfam, M.; Fidan, T.; Kurt, H.; Yüce, M.; Clarke, N.; Bayazit, M.K. Microwave-Promoted Continuous Flow Systems in Nanoparticle Synthesis—A Perspective. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 9988–10015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karelou, M.; Kampasis, D.; Kalampaliki, A.D.; Persoons, L.; Krämer, A.; Schols, D.; Knapp, S.; De Jonghe, S.; Kostakis, I.K. Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of 2-Substituted Quinazolin-4(3H)-Ones with Antiproliferative Activities. Molecules 2023, 28, 7912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, M.; Beahm, B.J.; Bode, J.W. Chiral NHC-Catalyzed Oxodiene Diels−Alder Reactions with α-Chloroaldehyde Bisulfite Salts. Org. Lett. 2008, 10, 3817–3820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosropour, A.R.; Khodaei, M.M.; Beygzadeh, M. Highly convenient one-pot conversion of aryl acylals or aryl aldehyde bisulfites into dihydropyrimidones using BI(NO3)3·5H2O. Heteroat. Chem. 2007, 18, 684–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furigay, M.H.; Boucher, M.M.; Mizgier, N.A.; Brindle, C.S. Separation of Aldehydes and Reactive Ketones from Mixtures Using a Bisulfite Extraction Protocol. J. Vis. Exp. 2018, e57639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kissane, M.G.; Frank, S.A.; Rener, G.A.; Ley, C.P.; Alt, C.A.; Stroud, P.A.; Vaid, R.K.; Boini, S.K.; McKee, L.A.; Vicenzi, J.T.; et al. Counterion effects in the preparation of aldehyde–bisulfite adducts. Tetrahedron Lett. 2013, 54, 6587–6591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Iyer, K.S.; Thakore, R.R.; Leahy, D.K.; Bailey, J.D.; Lipshutz, B.H. Bisulfite Addition Compounds as Substrates for Reductive Aminations in Water. Org. Lett. 2021, 23, 7205–7208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Betti, M.; Genesio, E.; Marconi, G.; Sanna Coccone, S.; Wiedenau, P. A Scalable Route to the SMO Receptor Antagonist SEN826: Benzimidazole Synthesis via Enhanced in Situ Formation of the Bisulfite–Aldehyde Complex. Org. Proc. Res. Dev. 2014, 18, 699–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behera, S.; Bera, S.K.; Basoccu, F.; Cuccu, F.; Caboni, P.; De Luca, L.; Porcheddu, A. Application of Bertagnini’s Salts in a Mechanochemical Approach Toward Aza-Heterocycles and Reductive Aminations via Imine Formation. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badolato, M.; Aiello, F.; Neamati, N. 2,3-Dihydroquinazolin-4(1H)-one as a privileged scaffold in drug design. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 20894–20921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, Y.; Lee, S.B.; Hong, J.; Chun, S.; Lee, J.; Hong, S. Synthesis of 2-aryl quinazolinones via iron-catalyzed cross-dehydrogenative coupling (CDC) between N–H and C–H bonds. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2020, 18, 5435–5441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiwari, A.R.; Bhanage, B.M. Synthesis of quinazolines from 2-aminobenzylamines with benzylamines and N-substituted benzylamines under transition metal-free conditions. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2016, 14, 10567–10571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sankar, M.; Nowicka, E.; Carter, E.; Murphy, D.M.; Knight, D.W.; Bethell, D.; Hutchings, G.J. The benzaldehyde oxidation paradox explained by the interception of peroxy radical by benzyl alcohol. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 3332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Dong, J.; Chen, X.; Li, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Yin, S.-F. Metal- and Oxidant-Free Synthesis of Quinazolinones from β-Ketoesters with o-Aminobenzamides via Phosphorous Acid-Catalyzed Cyclocondensation and Selective C–C Bond Cleavage. J. Org. Chem. 2015, 80, 9392–9400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sardar, B.; Jamatia, R.; Samanta, A.; Srimani, D. Ru Doped Hydrotalcite Catalyzed Borrowing Hydrogen-Mediated N-Alkylation of Benzamides, Sulfonamides, and Dehydrogenative Synthesis of Quinazolinones. J. Org. Chem. 2022, 87, 5556–5567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alam, M.T.; Maiti, S.; Mal, P. The mechanochemical synthesis of quinazolin-4(3H)-ones by controlling the reactivity of IBX. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2018, 14, 2396–2403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.; Chen, W.; Liang, J.; Yang, Q.; Fan, Y.; Chen, M.-W.; Peng, Y. α-Keto Acids as Triggers and Partners for the Synthesis of Quinazolinones, Quinoxalinones, Benzooxazinones, and Benzothiazoles in Water. J. Org. Chem. 2021, 86, 14866–14882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dutta, B.; Dutta, N.; Dutta, A.; Gogoi, M.; Mehra, S.; Kumar, A.; Deori, K.; Sarma, D. [DDQM][HSO(4)]/TBHP as a Multifunctional Catalyst for the Metal Free Tandem Oxidative Synthesis of 2-Phenylquinazolin-4(3H)-ones. J. Org. Chem. 2023, 88, 14748–14752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Cheng, G.; Shen, J.; Kuai, C.; Cui, X. Cleavage of the C–C triple bond of ketoalkynes: Synthesis of 4(3H)-quinazolinones. Org. Chem. Front. 2015, 2, 366–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, M.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, Z.; Lu, J.; Wang, F. The cascade synthesis of quinazolinones and quinazolines using an α-MnO2 catalyst and tert-butyl hydroperoxide (TBHP) as an oxidant. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 9205–9207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmoud, M.R.; El-Bordany, E.A.A.; Hassan, N.F.; El-Azm, F.S.M.A. New 2,3-Disubstituted Quinazolin-4(3H)-Ones from 2-Undecyl-3,1-Benzoxazin-4-One. J. Chem. Res. 2007, 2007, 541–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Li, Y.; Cheng, G.; Wang, L.; Cui, X. Copper-Catalyzed Synthesis of 2-Arylquinazolinones from 2-Arylindoles with Amines or Ammoniums. J. Org. Chem. 2015, 80, 7099–7107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Wang, L.; Li, M.; Tao, M.; Zhang, W. Phosphorous acid functionalized polyacrylonitrile fibers with a polarity tunable surface micro-environment for one-pot C–C and C–N bond formation reactions. Green Chem. 2017, 19, 5818–5830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, Y.-H.; Fan, L.-Y.; Li, X.-X.; Liu, M.-X. Y(OTf)3-catalyzed heterocyclic formation via aerobic oxygenation: An approach to dihydro quinazolinones and quinazolinones. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2015, 26, 1355–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; He, L.; Neumann, H.; Beller, M.; Wu, X.-F. Cascade synthesis of quinazolinones from 2-aminobenzonitriles and aryl bromides via palladium-catalyzed carbonylation reaction. Green Chem. 2014, 16, 1336–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.M.; Chada, H.; Biswal, S.; Sharma, S.; Sharada, D.S. Copper-Catalyzed Intramolecular α-C–H Amination via Ring-Opening Cyclization Strategy to Quinazolin-4-ones: Development and Application in Rutaecarpine Synthesis. Synthesis 2019, 51, 3160–3170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumdar, B.; Sarma, D.; Jain, S.; Sarma, T.K. One-Pot Magnetic Iron Oxide–Carbon Nanodot Composite-Catalyzed Cyclooxidative Aqueous Tandem Synthesis of Quinazolinones in the Presence of tert-Butyl Hydroperoxide. ACS Omega 2018, 3, 13711–13719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gnyawali, K.; Kirinde Arachchige, P.T.; Yi, C.S. Synthesis of Flavanone and Quinazolinone Derivatives from the Ruthenium-Catalyzed Deaminative Coupling Reaction of 2′-Hydroxyaryl Ketones and 2-Aminobenzamides with Simple Amines. Org. Lett. 2022, 24, 218–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Temp (°C) | Solvent | Time (h) | Conversion (3aa: 3aa′) b |

| 1 | 80 | H2O | 8 | 15:85 |

| 2 | 90 | H2O | 8 | 65:35 |

| 3 | 100 | H2O | 6 | 80:20 |

| 4 | 100 | H2O | 8 | 98:2 |

| 5 | 100 | H2O | 10 | >99 (91%) c |

| 6 | 25 | H2O | 10 | - |

| 7 | 100 | - | 10 | 80:12 |

| 8 | 100 | DMSO | 10 | >99 (86%) c |

| 9 | 100 | Toluene | 10 | 47:35 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bera, S.K.; Behera, S.; De Luca, L.; Basoccu, F.; Mocci, R.; Porcheddu, A. Unveiling the Untapped Potential of Bertagnini’s Salts in Microwave-Assisted Synthesis of Quinazolinones. Molecules 2024, 29, 1986. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29091986

Bera SK, Behera S, De Luca L, Basoccu F, Mocci R, Porcheddu A. Unveiling the Untapped Potential of Bertagnini’s Salts in Microwave-Assisted Synthesis of Quinazolinones. Molecules. 2024; 29(9):1986. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29091986

Chicago/Turabian StyleBera, Shyamal Kanti, Sourav Behera, Lidia De Luca, Francesco Basoccu, Rita Mocci, and Andrea Porcheddu. 2024. "Unveiling the Untapped Potential of Bertagnini’s Salts in Microwave-Assisted Synthesis of Quinazolinones" Molecules 29, no. 9: 1986. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29091986

APA StyleBera, S. K., Behera, S., De Luca, L., Basoccu, F., Mocci, R., & Porcheddu, A. (2024). Unveiling the Untapped Potential of Bertagnini’s Salts in Microwave-Assisted Synthesis of Quinazolinones. Molecules, 29(9), 1986. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29091986