Azobenzene as an Effective Ligand in Europium Chemistry—A Synthetic and Theoretical Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

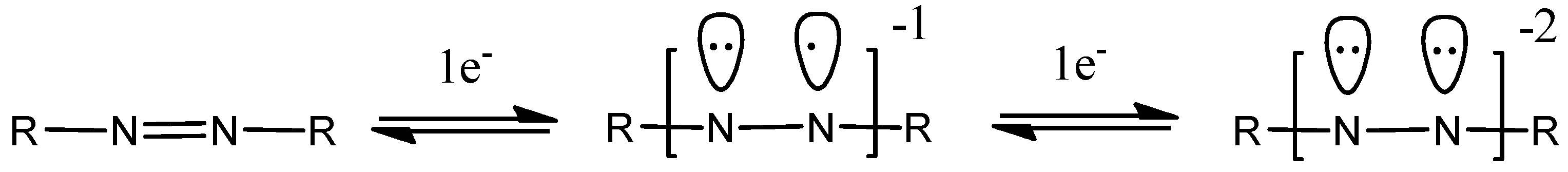

2. Results and Discussion

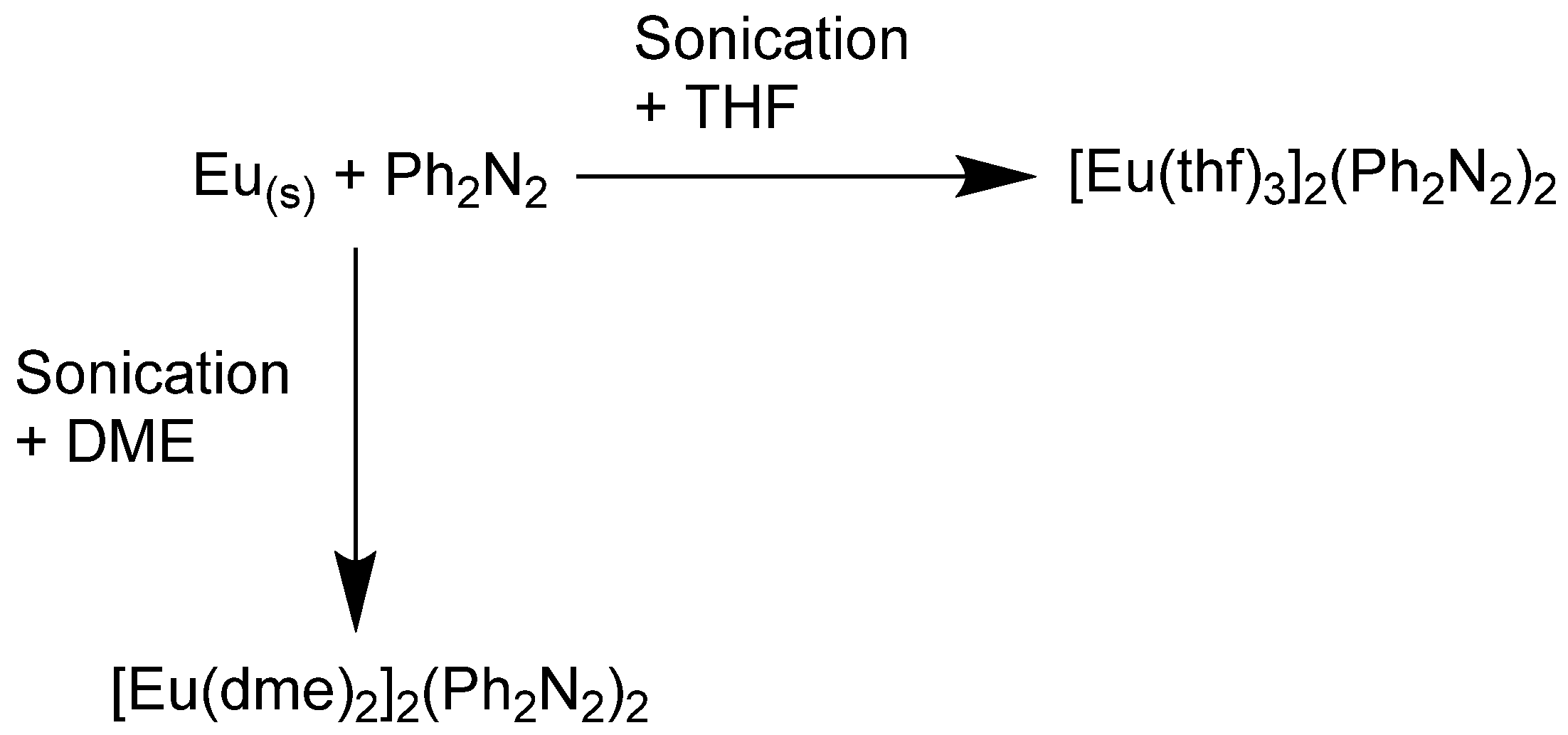

2.1. Synthesis

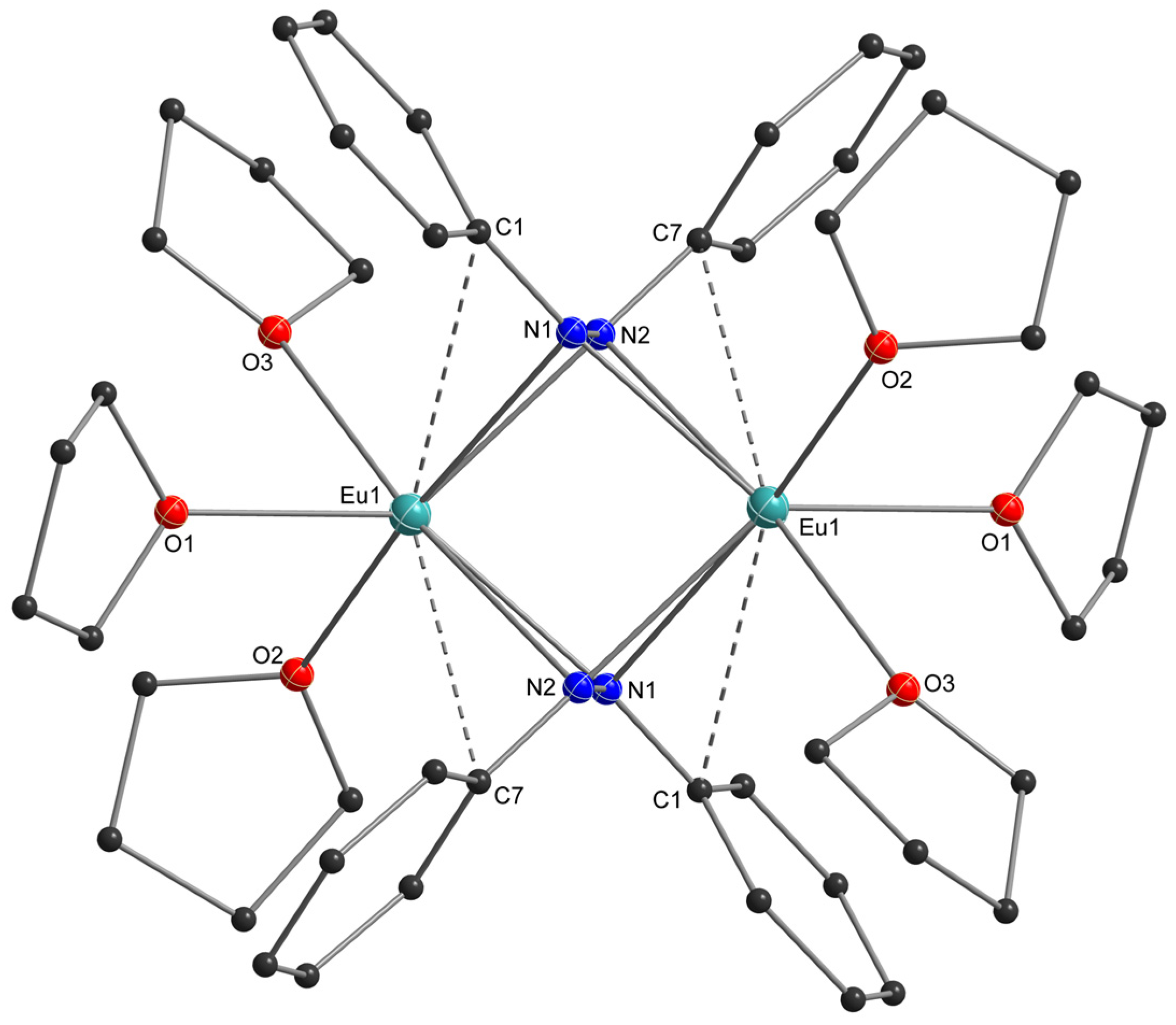

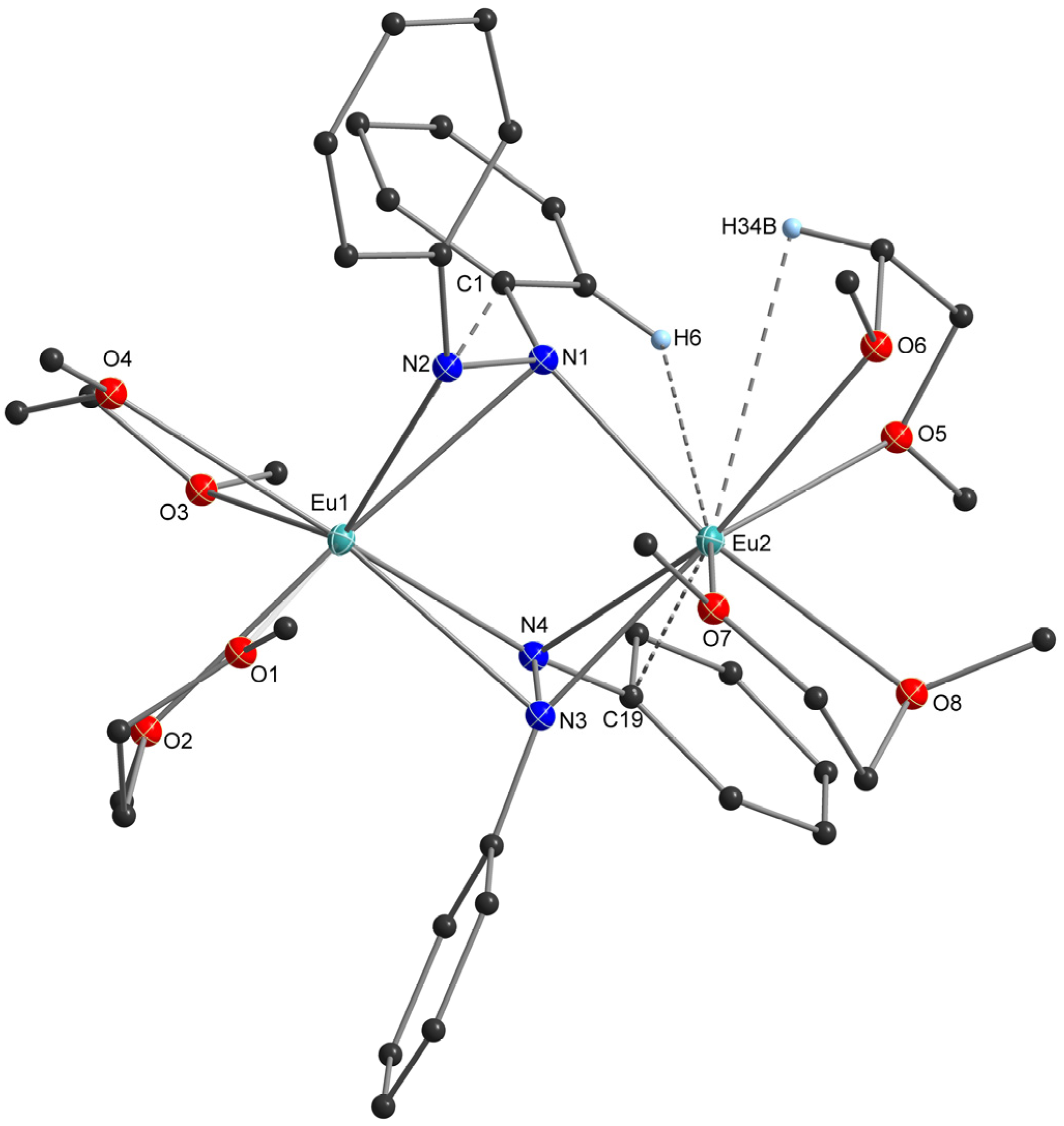

2.2. X-Ray Crystal Structures

3. Discussion

3.1. Synthetic and Spectral Aspects

3.2. Structural Aspects

3.3. Computational Modeling

- For 1, across these ranges of theory, increasing the basis set size (and computational cost) from Def2-SVP to Def2-TVZ does not improve agreement with the crystal structure geometry except when using the LC-ωHPBE density functional with no dispersion correction.

- The LC-ωHPBE density functional with the GD3(BJ) dispersion correction produces geometries with RMSDs nearly half those of the remainder of the survey. We note that this does not mean that the LC-ωHPBE density functional is the means to producing the best gas-phase geometry until it can be determined that the geometry of the complex is only minimally impacted by crystal packing interactions. In the case of 1, where inter-complex interactions are predominantly between THF C-H bonds and azobenzene phenyl rings, such a condition might be completely reasonable.

- Except for the Eu-N1 distance (one of the two longer Eu-N distances), the inclusion of dispersion corrections uniformly improves agreement with the experiment for all of the considered theory levels.

- NPA comparisons show a uniform sensitivity to the natural charges on the Eu atoms with a choice of SVP or TZV but only a fractional difference between N atoms in either case (and similar for the O atoms, which uniformly have predicted natural charges in the −0.55 to −0.59 e− range).

- Considering the Eu-C(π) distances among the calculations reveals that using the smaller Def2-SVP basis set leads to markedly better agreement with the crystal geometry than Def2-TZV, and that dispersion corrections provide only fractional additional improvements in agreement. In terms of the generation of molecular structures for computational assessment, the crystal geometry of 1 can be better reproduced with theory levels differing only in the basis set that reduces the compute time per SCF cycle by 50% or more.

- With some small variation across all methods, the calculated Eu-C(π) distances are all in good agreement with the experiment and within the range of accepted values for these interactions. The removal of these complexes from the crystal environment and optimization as gas-phase species preserved these distances, indicating that their formation is not directly attributable to crystal packing but instead some energetic preference for including these coordinative interactions as part of the overall environment around each metal.

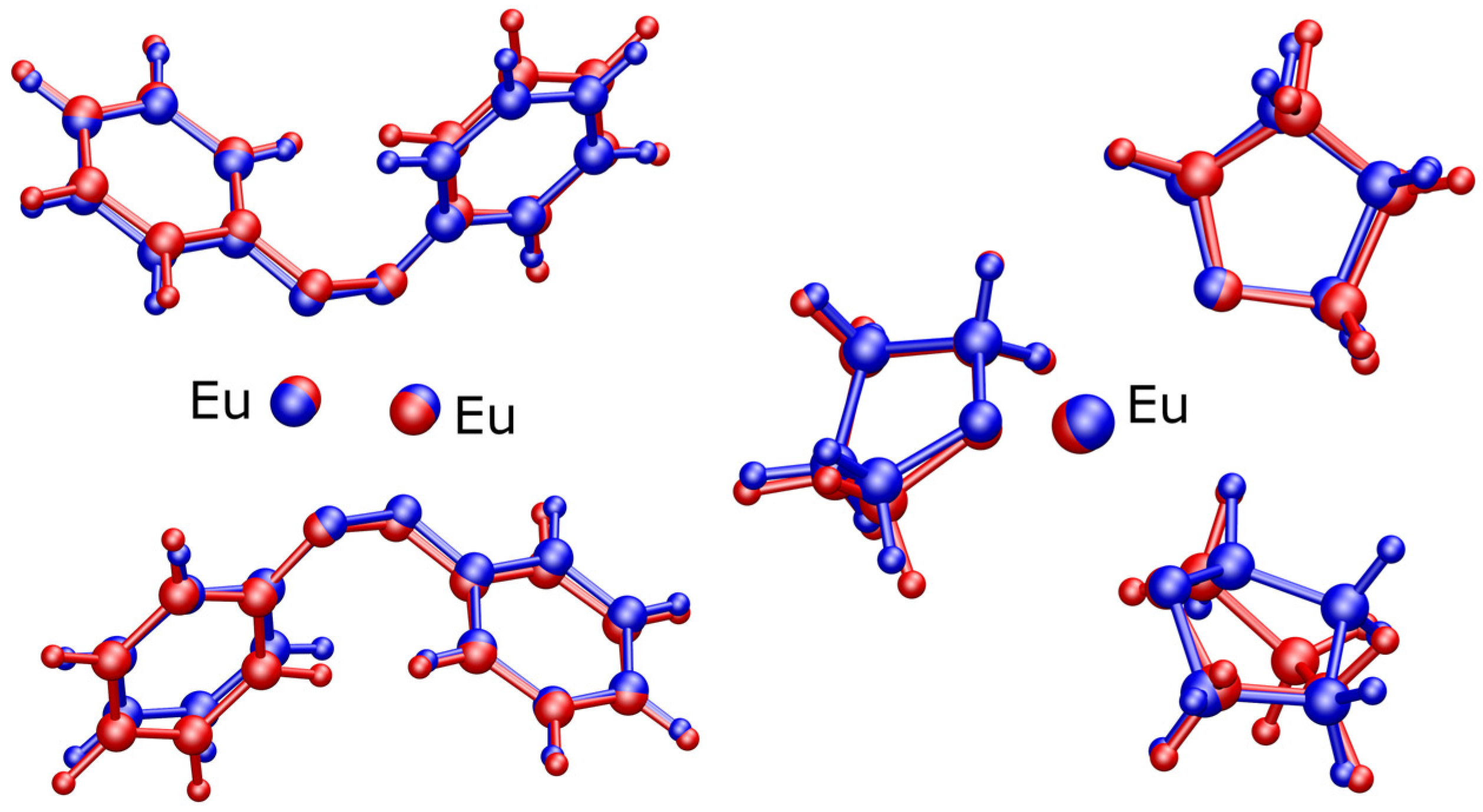

- Geometry comparisons (Figure 4) reveal that the shifting of the THF C4H8 chains during energy minimization produces the largest differences between gas-phase theory and crystal geometry. This is by no means unexpected, as the complete encapsulation of the Eu metals by the most electronegative atoms in these complexes leaves only the ligand fragments capable of the weakest of electrostatic interactions to undergo the structurally large but energetically small changes as part of crystal packing.

- There is clear disagreement in the prediction of the vibrational mode energy for the N=N stretch in the isolated cis-azobenzene using Def2-SVP vs. Def2-TZV, where Def2-SVP calculations can differ from the accepted 1511 cm−1 value by 11% to 20%. In the complex, however, Def2-SVP and Def2-TZV predicted mode energies for the symmetric and asymmetric N=N stretching pair differ by only a few cm−1 in all cases. Again, the time savings from using Def2-SVP across both optimization and normal mode analysis are considerable over Def2-TZV for the same density functionals and dispersion corrections.

- The one notable difference between LC-ωHPBE and the other three density functionals is to be found in the prediction that the N=N stretching modes are not localized to a single dominant stretching mode. With LC-ωHPBE, the lower-energy pair of stretches is coupled to phenyl ring expansion modes, while the higher-energy pair is coupled to phenyl lateral wagging modes. This splitting is 10 cm−1 with Def2-SVP and 40 cm−1 with Def2-TZV.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. General Methods and Synthesis

4.2. Single-Crystal X-Ray Diffraction

4.3. Computational Methods

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cotton, S.A.; Raithby, P.R. Systematics and Surprises in Lanthanide Coordination Chemistry. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2017, 340, 220–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmudov, K.T.; Huseynov, F.E.; Aliyeva, V.A.; Guedes da Silva, M.F.C.; Pombeiro, A.J.L. Noncovalent Interactions at Lanthanide Complexes. Chem.—Eur. J. 2021, 27, 14370–14389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, X.; Xu, J.; Wu, Y.; Liu, X. Energy-Transfer Editing in Lanthanide-Activated Upconversion Nanocrystals: A Toolbox for Emerging Applications. ACS Cent. Sci. 2019, 5, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daumann, L.J. Essential and Ubiquitous: The Emergence of Lanthanide Metallobiochemistry. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 12795–12802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hitzbleck, J.; O’Brien, A.Y.; Forsyth, C.M.; Deacon, G.B.; Ruhlandt-Senge, K. Heavy Alkaline Earth Metal Pyrazolates: Synthetic Pathways, Structural Trends, and Comparison with Divalent Lanthanoids. Chem.—Eur. J. 2004, 10, 3315–3323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deacon, G.B.; Junk, P.C.; Moxey, G.J.; Ruhlandt-Senge, K.; St. Prix, C.; Zuniga, M.F. Charge-Separated and Molecular Heterobimetallic Rare Earth–Rare Earth and Alkaline Earth–Rare Earth Aryloxo Complexes Featuring Intramolecular Metal–π-Arene Interactions. Chem.—Eur. J. 2009, 15, 5503–5519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, N.N.; Earnshaw, A. Chemistry of the Elements, 2nd ed.; Elsevier Ltd.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Bochmann, M.; Cotton, F.A.; Wilkinson, G.; Murillo, C.A. Advanced Inorganic Chemistry, 6th ed.; Wiley-Interscience: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Shannon, R.D. Revised Effective Ionic Radii and Systematic Studies of Interatomic Distances in Halides and Chalcogenides. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. A 1976, 32, 751–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiekink, E.R.T. Supramolecular Assembly Based on “Emerging” Intermolecular Interactions of Particular Interest to Coordination Chemists. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2017, 345, 209–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornaton, Y.; Djukic, J.-P. Noncovalent Interactions in Organometallic Chemistry: From Cohesion to Reactivity, a New Chapter. Acc. Chem. Res. 2021, 54, 3828–3840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, L.; Graus, S.; Tejedor, R.M.; Chanthapally, A.; Serrano, J.L.; Uriel, S. The Combination of Halogen and Hydrogen Bonding: A Versatile Tool in Coordination Chemistry. CrystEngComm 2020, 22, 6010–6018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, W.D.; Guino-o, M.A.; Ruhlandt-Senge, K. Highly Volatile Alkaline Earth Metal Fluoroalkoxides. Inorg. Chem. 2010, 49, 7144–7155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchanan, W.D.; Ruhlandt-Senge, K. M—F Interactions and Heterobimetallics: Furthering the Understanding of Heterobimetallic Stabilization. Chem.—Eur. J. 2013, 19, 10708–10715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hitzbleck, J.; O’Brien, A.Y.; Deacon, G.B.; Ruhlandt-Senge, K. Role of Donor and Secondary Interactions in the Structures and Thermal Properties of Alkaline-Earth and Rare-Earth Metal Pyrazolates. Inorg. Chem. 2006, 45, 10329–10337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deacon, G.B.; Forsyth, C.M.; Gitlits, A.; Harika, R.; Junk, P.C.; Skelton, B.W.; White, A.H. Pyrazolate Coordination Continues To Amaze—The New μ-H2:H1 Binding Mode and the First Case of Unidentate Coordination to a Rare Earth Metal. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2002, 41, 3249–3251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, M.L.P.; Divya, V.; Pavithran, R. Visible-Light Sensitized Luminescent Europium(Iii)-β-Diketonate Complexes: Bioprobes for Cellular Imaging. Dalton Trans. 2013, 42, 15249–15262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, S.J.; Delbianco, M.; Lamarque, L.; McMahon, B.K.; Neil, E.R.; Pal, R.; Parker, D.; Walton, J.W.; Zwier, J.M. EuroTracker® Dyes: Design, Synthesis, Structure and Photophysical Properties of Very Bright Europium Complexes and Their Use in Bioassays and Cellular Optical Imaging. Dalton Trans. 2015, 44, 4791–4803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Higashiyama, N.; Machida, K.; Adachi, G. The Luminescent Properties of Divalent Europium Complexes of Crown Ethers and Cryptands. Coord. Chem. Rev. 1998, 170, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allman, R. The Chemistry of the Hydrazo, Azo and Azoxy Groups; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Hunger, K.; Mischke, P.; Rieper, W.; Zhang, S. Azo Dyes, 1. General. In Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry; Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KgaA: Weinheim, Germany, 2017; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beharry, A.A.; Woolley, G.A. Azobenzene Photoswitches for Biomolecules. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011, 40, 4422–4437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.; Zou, S.; Li, T.; Karges, J.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Ji, L.; Chao, H. Chiral Rhodium(Iii)–Azobenzene Complexes as Photoswitchable DNA Molecular Locks. Chem. Commun. 2022, 58, 4324–4327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Kadkin, O.N.; Tae, J.-G.; Choi, M.-G. Photoresponsive Palladium(II) Complexes with Azobenzene Incorporated into Benzyl Aryl Ether Dendrimers. Inorganica Chim. Acta 2008, 361, 3063–3068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazhenova, T.A.; Emelyanova, N.S.; Shestakov, A.F.; Shilov, A.E.; Antipin, M.Y.; Lyssenko, K.A. Molecular Structure and Reactions of Azobenzene Complexes with Iron-Lithium Compounds. Inorganica Chim. Acta 1998, 280, 288–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peedika Paramban, R.; Guo, Z.; Deacon, G.B.; Junk, P.C. Reactivity of [Sm(DippForm)2(Thf)2] with Substrates Containing Azo Linkages. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2024, 27, e202300583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, C.A.P.; Chilton, N.F.; Vettese, G.F.; Moreno Pineda, E.; Crowe, I.F.; Ziller, J.W.; Winpenny, R.E.P.; Evans, W.J.; Mills, D.P. Physicochemical Properties of Near-Linear Lanthanide(II) Bis(Silylamide) Complexes (Ln = Sm, Eu, Tm, Yb). Inorg. Chem. 2016, 55, 10057–10067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mashima, K.; Nakayama, Y.; Shibahara, T.; Fukumoto, H.; Nakamura, A. Synthesis of Arenethiolate Complexes of Divalent and Trivalent Lanthanides from Metallic Lanthanides and Diaryl Disulfides: Crystal Structures of [{Yb(Hmpa)3}2(μ-SPh)3][SPh] and Ln(SPh)3(Hmpa)3 (Ln = Sm, Yb; Hmpa = Hexamethylphosphoric Triamide). Inorg. Chem. 1996, 35, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jori, N.; Moreno, J.J.; Shivaraam, R.A.K.; Rajeshkumar, T.; Scopelliti, R.; Maron, L.; Campos, J.; Mazzanti, M. Iron Promoted End-on Dinitrogen-Bridging in Heterobimetallic Complexes of Uranium and Lanthanides. Chem. Sci. 2024, 15, 6842–6852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Kadri, O.M.; Heeg, M.J.; Winter, C.H. Synthesis, Structure, Properties, Volatility, and Thermal Stability of Molybdenum(II) and Tungsten(II) Complexes Containing Allyl, Carbonyl, and Pyrazolate or Amidinate Ligands. J. Organomet. Chem. 2009, 694, 3902–3911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rad, N.E.; Junk, P.C.; Deacon, G.B.; Wang, J. New Homoleptic Rare Earth 3,5-Diphenylpyrazolates and 3,5-Di-Tert-Butylpyrazolates and a Noteworthy Structural Discontinuity. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 2019, 645, 877–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruker APEX2 and SAINT; Bruker: Billerica, MA, USA, 2012.

- Sheldrick, G.M. CELL NOW; Georg-August-Universität: Göttingen, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Blessing, R.H. An Empirical Correction for Absorption Anisotropy. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. A 1995, 51, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SADABS; Bruker: Billerica, MA, USA, 2003.

- Sheldrick, G.M. It SHELXT—Integrated Space-Group and Crystal-Structure Determination. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. A 2015, 71, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldrick, G.M. Phase Annealing in SHELX-90: Direct Methods for Larger Structures. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. A 1990, 46, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldrick, G.M. SHELXS97; University of Gottingen: Gottingen, Germany, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Sheldrick, G.M. A Short History of It SHELX. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. A 2008, 64, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldrick, G.M. Crystal Structure Refinement with It SHELXL. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. C 2015, 71, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hübschle, C.B.; Sheldrick, G.M.; Dittrich, B. It ShelXle: A Qt Graphical User Interface for It SHELXL. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2011, 44, 1281–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spek, A.L. Single-Crystal Structure Validation with the Program It PLATON. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2003, 36, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spek, A.L. Structure Validation in Chemical Crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D 2009, 65, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macrae, C.F.; Bruno, I.J.; Chisholm, J.A.; Edgington, P.R.; McCabe, P.; Pidcock, E.; Rodriguez-Monge, L.; Taylor, R.; Van De Streek, J.; Wood, P.A. Mercury CSD 2.0–New Features for the Visualization and Investigation of Crystal Structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2008, 41, 466–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putz, H.; Brandenburg, K. Diamond—Crystal and Molecular Structure Visualization. Crystal Impact GbR: Bonn, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, F.H. The Cambridge Structural Database: A Quarter of a Million Crystal Structures and Rising. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. B 2002, 58 Pt 1, 380–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groom, C.R.; Bruno, I.J.; Lightfoot, M.P.; Ward, S.C. The Cambridge Structural Database. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. B 2016, 72, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becke, A.D. Density-functional Thermochemistry. III. Role Exact Exchange. J. Chem. Phys. 1993, 98, 5648–5652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanai, T.; Tew, D.P.; Handy, N.C. A New Hybrid Exchange–Correlation Functional Using the Coulomb-Attenuating Method (CAM-B3LYP). Chem. Phys. Lett. 2004, 393, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, T.M.; Izmaylov, A.F.; Scalmani, G.; Scuseria, G.E. Can Short-Range Hybrids Describe Long-Range-Dependent Properties? J. Chem. Phys. 2009, 131, 044108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chai, J.-D.; Head-Gordon, M. Long-Range Corrected Hybrid Density Functionals with Damped Atom–Atom Dispersion Corrections. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2008, 10, 6615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grimme, S. Semiempirical GGA-Type Density Functional Constructed with a Long-Range Dispersion Correction. J. Comput. Chem. 2006, 27, 1787–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grimme, S.; Ehrlich, S.; Goerigk, L. Effect of the Damping Function in Dispersion Corrected Density Functional Theory. J. Comput. Chem. 2011, 32, 1456–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weigend, F. Accurate Coulomb-Fitting Basis Sets for H to Rn. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2006, 8, 1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolg, M.; Stoll, H.; Preuss, H. A Combination of Quasirelativistic Pseudopotential and Ligand Field Calculations for Lanthanoid Compounds. Theoret. Chim. Acta 1993, 85, 441–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, A.E.; Weinstock, R.B.; Weinhold, F. Natural Population Analysis. J. Chem. Phys. 1985, 83, 735–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritchard, B.P.; Altarawy, D.; Didier, B.; Gibson, T.D.; Windus, T.L. New Basis Set Exchange: An Open, Up-to-Date Resource for the Molecular Sciences Community. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2019, 59, 4814–4820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Caricato, M.; Hratchian, H.P.; Li, X.; Barone, V.; Bloino, J.; Zheng, G.; et al. Gaussian 09. Available online: https://gaussian.com/glossary/g09/ (accessed on 27 October 2024).

| Metal Cation (2+) | Ionic Radii (Å) | Electronegativity (Pauling) | E° (V) (M2+ (aq) + 2e− = M(s)) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | 1.12 | 1.00 | −2.87 |

| Yb | 1.14 | 1.10 | −2.22 |

| Sr | 1.25 | 0.95 | −2.89 |

| Sm | 1.26 | 1.17 | −2.30 |

| Eu | 1.24 | 1.20 | −1.99 |

| Ba | 1.42 | 0.89 | −2.90 |

| Compound | N-N (Å) Ligand | Eu-N (Å) Ligand | Eu-O (Å) Donor | N-Eu-N (°) Ligand | Dihedral (ɸ), Ph-NN-Ph (°) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [Eu(thf)3]2(N2Ph2)2 | 1.471(3) | 2.469(3) 2.675(2) 2.456(2) 2.675(2) | ― | 2.592(2)– 2.659(2) | 33.00(7) 32.91(7) | 83.52(1) |

| [Eu(dme)2]2(N2Ph2)2 | 1.472(8), 1.479(7) | Eu1 2.707(6) 2.494(6) 2.644(6) 2.499(6) | Eu2 2.455(6) 3.237(5) 2.445(6) 2.731(5) | 2.620(5)– 2.733(5) | 32.5(2) 33.2(2) 32.6(2) | 75.5(7) 78.8(7) |

| Compound | Eu···C(π) (Å) | Eu···C(π) (Å) | Eu···H-C (Å) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [Eu(thf)3]2(N2Ph2)2 | Eu1 3.19 (C1) 3.28 (C7) | Eu1 3.19 (C1) 3.28 (C7) | 2.98–3.29 | ― | |

| [Eu(dme)2]2(N2Ph2)2 | Eu1 3.09 (C1) | Eu2 3.13 (C19) | ― | Eu1 ― | Eu2 3.21 (H34B, DME) 3.25 (H6, Ph2N2) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Allis, D.G.; Torvisco, A.; Webb, C.C., Jr.; Gillett-Kunnath, M.M.; Ruhlandt-Senge, K. Azobenzene as an Effective Ligand in Europium Chemistry—A Synthetic and Theoretical Study. Molecules 2024, 29, 5187. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29215187

Allis DG, Torvisco A, Webb CC Jr., Gillett-Kunnath MM, Ruhlandt-Senge K. Azobenzene as an Effective Ligand in Europium Chemistry—A Synthetic and Theoretical Study. Molecules. 2024; 29(21):5187. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29215187

Chicago/Turabian StyleAllis, Damian G., Ana Torvisco, Cody C. Webb, Jr., Miriam M. Gillett-Kunnath, and Karin Ruhlandt-Senge. 2024. "Azobenzene as an Effective Ligand in Europium Chemistry—A Synthetic and Theoretical Study" Molecules 29, no. 21: 5187. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29215187

APA StyleAllis, D. G., Torvisco, A., Webb, C. C., Jr., Gillett-Kunnath, M. M., & Ruhlandt-Senge, K. (2024). Azobenzene as an Effective Ligand in Europium Chemistry—A Synthetic and Theoretical Study. Molecules, 29(21), 5187. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29215187