Design, Synthesis, Antifungal Activity, and 3D-QSAR Study of Novel Quinoxaline-2-Oxyacetate Hydrazide

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

3. Materials and Methods

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, L.; Zhu, X.-M.; Zhang, Y.-R.; Cai, Y.-Y.; Wang, J.-Y.; Liu, M.-Y.; Wang, J.-Y.; Bao, J.-D.; Lin, F.-C. Research on the Molecular Interaction Mechanism between Plants and Pathogenic Fungi. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.-L.; Han, L.-J.; Wu, X.-M.; Jiang, W.; Liao, H.; Xu, Z.; Pan, C.-P. Trends and perspectives on general Pesticide analytical chemistry. Adv. Agrochem. 2022, 1, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strange, R.N.; Scott, P.R. Plant Disease: A Threat to Global Food Security. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2005, 43, 83–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Fu, X.; Chen, M.; Wang, A.; Yan, J.; Mei, Y.; Wang, M.; Yang, C. Novel 1,3,5-thiadiazine-2-thione derivatives containing a hydrazide moiety: Design, synthesis and bioactive evaluation against phytopathogenic fungi in vitro and in vivo. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2019, 30, 1419–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swain, T. Secondary Compounds as Protective Agents. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 1977, 28, 479–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Duan, C.-B.; Jin, B.; Ali, A.S.; Han, X.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, M.-Z.; Zhang, W.-H.; Gu, Y.-C. Recent advances in the natural products-based lead discovery for new agrochemicals. Adv. Agrochem. 2023, 2, 324–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arif, T.; Bhosale, J.D.; Kumar, N.; Mandal, T.K.; Bendre, R.S.; Lavekar, G.S.; Dabur, R. Natural products—Antifungal agents derived from plants. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 2009, 11, 621–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, D.P.; Mattoo, A.K. Sustainable Agriculture—Enhancing Environmental Benefits, Food Nutritional Quality and Building Crop Resilience to Abiotic and Biotic Stresses. Agriculture 2018, 8, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhameliya, T.M.; Chudasma, S.J.; Patel, T.M.; Dave, B.P. A review on synthetic account of 1,2,4-oxadiazoles as anti-infective agents. Mol. Divers. 2022, 26, 2967–2980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Fan, L.-L. Synthesis and antifungal activities of novel 5,6-dihydro-indolo[1,2-a]quinoxaline derivatives. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 46, 1919–1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Zhu, C.-H.; Xia, Z.-H.; Zhao, H.-Q. Quinoxalinone-1,2,3-triazole derivatives as potential antifungal agents for plant anthrax disease: Design, synthesis, antifungal activity and SAR study. Adv. Agrochem. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Zahabi, H.S.A. Synthesis, Characterization, and Biological Evaluation of Some Novel Quinoxaline Derivatives as Antiviral Agents. Arch. Pharm. 2017, 350, 1700028–1700040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Cheng, G.; Hao, H.; Pan, Y.; Liu, Z.; Dai, M.; Yuan, Z. In vitro antimicrobial activities of animal-used quinoxaline 1,4-di-N-oxides against mycobacteria, mycoplasma and fungi. BMC Vet. Res. 2016, 12, 186–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, E.; Ancizu, S.; Pérez-Silanes, S.; Torres, E.; Aldana, I.; Monge, A. Synthesis and antimycobacterial activity of new quinoxaline-2-carboxamide 1,4-di-N-oxide derivatives. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2010, 45, 4418–4426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shekhar, A.C.; Rao, P.S.; Narsaiah, B.; Allanki, A.D.; Sijwali, P.S. Emergence of pyrido quinoxalines as new family of antimalarial agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 77, 280–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhelmsson, L.M.; Kingi, N.; Bergman, J. Interactions of Antiviral Indolo[2,3-b]quinoxaline Derivatives with DNA. J. Med. Chem. 2008, 51, 7744–7750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Clercq, E. Toward Improved Anti-HIV Chemotherapy: Therapeutic Strategies for Intervention with HIV Infections. J. Med. Chem. 1995, 38, 2491–2517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borah, B.; Chowhan, L.R. Recent advances in the transition-metal-free synthesis of quinoxalines. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 37325–37353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montana, M.; Mathias, F.; Terme, T.; Vanelle, P. Antitumoral activity of quinoxaline derivatives: A systematic review. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 163, 136–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, J.A.; Pessoa, A.M.; Cordeiro, M.N.; Fernandes, R.; Prudencio, C.; Noronha, J.P.; Vieira, M. Quinoxaline, its derivatives and applications: A State of the Art review. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 97, 664–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq, S.; Alam, O.; Synthesis, M.A. Anti-inflammatory, p38α MAP kinase inhibitory activities and molecular docking studies of quinoxaline derivatives containing triazole moiety. Bioorg. Chem. 2018, 76, 343–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.; Wang, K.; MacMillan, J.B. Hunanamycin A, an Antibiotic from a Marine-Derived Bacillus hunanensis. Org. Lett. 2013, 15, 390–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, R.; Guo, T.; He, J.; Chen, M.; Su, S.; Jiang, S.; Tang, X.; Chen, Y.; Xue, W. Antimicrobial evaluation and action mechanism of chalcone derivatives containing quinoxaline moiety. Monatsh. Chem. 2019, 150, 1325–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, T.; Chen, Z.; Fang, H.; Hua, X. A Comprehensive Investigation of Hydrazide and Its Derived Structures in the Agricultural Fungicidal Field. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023, 71, 8297–8316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niu, J.-B.; Quan, C.-H.; Liu, Y.; Yu, G.-X.; Yang, J.-J.; Li, Y.-R.; Zhang, Y.-B.; Qi, Y.-Q.; Song, J.; Jin, C.-Y.; et al. Discovery of N-aryl sulphonamide-quinazoline derivatives as anti-gastric cancer agents in vitro and in vivo via activating the Hippo signalling pathway. J. Enzym. Inhib. Med. Chem. 2021, 36, 1715–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.C.; Sharma, D.; Sharma, A.; Saini, N.; Goyal, R.; Ola, M.; Chawla, R.; Thakur, V.K. Hydrazone comprising compounds as promising anti-infective agents: Chemistry and structure-property relationship. Mater. Today Chem. 2020, 18, 100349–100369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stierli, D.; Eberle, M.; Lamberth, C.; Jacob, O.; Balmer, D.; Gulder, T. Quarternary α-cyanobenzylsulfonamides: A new subclass of CAA fungicides with excellent anti-Oomycetes activity. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2021, 30, 115965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.-W.; Zhao, L.-X.; Ma, P.; Ye, T.; Fu, Y.; Ye, F. Fragments recombination, design, synthesis, safener activity and CoMFA model of novel substituted dichloroacetylphenyl sulfonamide derivatives. Pest Manag. Sci. 2021, 77, 1724–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Fang, H.; Chang, J.; Zhang, T.; Cui, Y.; Zhang, L.; Sui, J.; Ma, Q.; Su, P.; Wang, J.; et al. Natural Alkaloid Waltherione F-Derived Hydrazide Compounds Evaluated in an Agricultural Fungicidal Field. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023, 71, 12333–12345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Zhang, R.; Lv, B.; Wang, W.-W.; Liu, Z.; Hu, Z.; Design, D.L. Synthesis and biological evaluation of thiazole and imidazo[1,2-a]pyridine derivatives containing a hydrazone substructure as potential agrochemicals. Adv. Agrochem. 2023, 2, 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-J.; Ma, K.-Y.; Du, S.-S.; Zhang, Z.-J.; Wu, T.-L.; Sun, Y.; Liu, Y.-Q.; Yin, X.-D.; Zhou, R.; Yan, Y.-F.; et al. Antifungal Exploration of Quinoline Derivatives against Phytopathogenic Fungi Inspired by Quinine Alkaloids. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 12156–12170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Dhameliya, T.M.; Sharma, K.; Patel, K.A.; Hirani, R.V.; Bhatt, A.J. Sustainable approaches towards the synthesis of quinoxalines: An update. J. Mol. Struct. 2022, 1259, 132732–132747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, X.; Wu, Z.; Bi, C.; Wang, J.; Zhao, F.; Gao, J.; Hou, Y.; Zhou, M. Molecular and Biochemical Characterization of Pydiflumetofen-Resistant Mutants of Didymella bryoniae. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 9120–9130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.D.; He, Y.H.; Ma, K.Y.; Li, H.; Zhang, Z.J.; Sun, Y.; Wang, Y.L.; Hu, G.F.; Wang, R.X.; Liu, Y.Q. Design and Discovery of Novel Antifungal Quinoline Derivatives with Acylhydrazide as a Promising Pharmacophore. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 8347–8357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Dai, Z.C.; Chen, Y.F.; Cao, L.L.; Yan, W.; Li, S.K.; Wang, J.X.; Zhang, Z.G. Synthesis of 1,2,3-triazole hydrazide derivatives exhibiting anti-phytopathogenic activity. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 126, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Wang, A.; Qiu, L.; Chen, M.; Lu, A.; Li, G.; Yang, C.; Xue, W. Expedient Discovery for Novel Antifungal Leads Targeting Succinate Dehydrogenase: Pyrazole-4-formylhydrazide Derivatives Bearing a Diphenyl Ether Fragment. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 14426–14437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Sun, S.; Li, W.; Mao, Y.; Wang, Q.; Duan, Y.; Csuk, R.; Li, S. Bioactivity-Guided Subtraction of MIQOX for Easily Available Isoquinoline Hydrazides as Novel Antifungal Candidates. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023, 71, 11341–11349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhi, X.Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.F.; Liu, Y.; Niu, W.P.; Li, Y.; Zhang, C.R.; Cao, H.; Hao, X.J.; Yang, C. Discovery of Natural Sesquiterpene Lactone 1-O-Acetylbritannilactone Analogues Bearing Oxadiazole, Triazole, or Imidazole Scaffolds for the Development of New Fungicidal Candidates. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023, 71, 11680–11691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

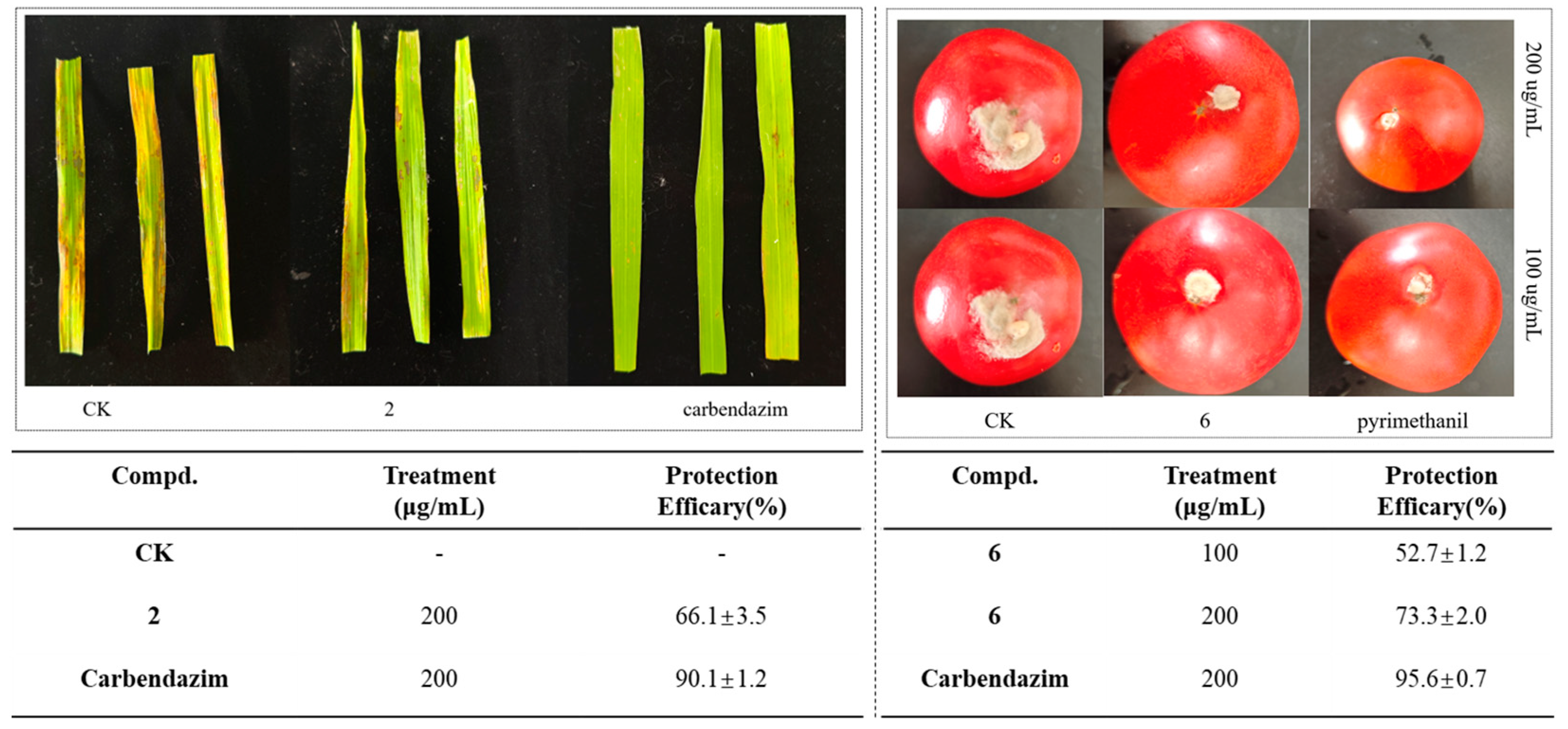

| Compd. | B. cinrea | A. solani | G. zeae | R. solani | C. orbiculare | A. alternata |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 86.1 ± 1.4 | 89.5 ± 1.2 | 95.8 ± 0.8 | 91.9 ± 0.9 | 100 | 96.4 ± 0.5 |

| 2 | 75.9 ± 0.5 | 48.1 ± 1.3 | 93.1 ± 0.6 | 94.4 ± 0.8 | 97.7 ± 0.5 | 100 |

| 3 | 88.8 ± 1.6 | 79.3 ± 0.7 | 59.7 ± 2.2 | 97.2 ± 0.7 | 100 | 91.2 ± 0.7 |

| 4 | 74.4 ± 1.6 | 66.4 ± 2.4 | 65.0 ± 1.2 | 77.4 ± 1.3 | 87.3 ± 1.1 | 85.0 ± 1.5 |

| 5 | 39.6 ± 3.0 | 40.7 ± 0.7 | 85.3 ± 0.6 | 96.4 ± 0.7 | 81.9 ± 0.6 | 60.9 ± 0.5 |

| 6 | 97.0 ± 0.6 | 80.6 ± 0 | 26.3 ± 0.7 | 70.2 ± 0.8 | 100 | 95.3 ± 2 |

| 7 | 80.8 ± 1.7 | 85.0 ± 0.7 | 99.7 ± 0.6 | 100 | 51.3 ± 1.0 | 100 |

| 8 | 10.2 ± 0.5 | 28.8 ± 1.0 | <10 | 39.5 ± 0.8 | <10 | <10 |

| 9 | 85.6 ± 1.4 | 73.7 ± 1.2 | 29.2 ± 1.3 | 97.2 ± 0.7 | 56.2 ± 1.1 | 46.9 ± 0.5 |

| 10 | 21.9 ± 1.1 | 47.9 ± 0.7 | 31.9 ± 2.0 | 81.9 ± 2.1 | 50 ± 0.6 | 41.1 ± 0.7 |

| 11 | 14.7 ± 1.6 | 58.6 ± 1.0 | 12.8 ± 1.2 | 81.0 ± 0.7 | 83.5 ± 0.5 | 60.4 ± 0.7 |

| 12 | 52.2 ± 1.0 | 56.5 ± 1.9 | 25.6 ± 1.2 | 73.9 ± 2.2 | 50.1 ± 0.7 | 72.0 ± 0.6 |

| 13 | 56.7 ± 1.0 | 42.1 ± 0.7 | 25.8 ± 1.9 | 75.0 ± 0.8 | 35.6 ± 0.6 | 73.6 ± 0.8 |

| 14 | 28.0 ± 1.2 | 60.7 ± 0.7 | 23.9 ± 0.8 | 79.6 ± 1.2 | 34.4 ± 2.6 | 77.1 ± 0.7 |

| 15 | 80.6 ± 1.7 | 6.4 ± 0.7 | 92.2 ± 1.2 | 98.0 ± 0.7 | 91.7 ± 0.6 | 63.2 ± 0.7 |

| 16 | 70.6 ± 1.1 | 62.1 ± 0.7 | 93.6 ± 0.6 | 94.4 ± 0.8 | 95.6 ± 0.6 | 97.9 ± 0.7 |

| 17 | 74.6 ± 1.7 | 66.4 ± 0.7 | 84.7 ± 1.1 | 96.4 ± 0.7 | 60.1 ± 2.9 | 48.1 ± 0.7 |

| 18 | 81.6 ± 1.4 | 65.1 ± 0.8 | 91.4 ± 0.6 | 98.0 ± 1.3 | 94.8 ± 0.7 | 87.8 ± 2.4 |

| 19 | 20.4 ± 0.7 | 33.6 ± 0.7 | 42.2 ± 2.3 | 73.4 ± 0.8 | 18.8 ± 0.7 | 23.1 ± 0.7 |

| 20 | 93.8 ± 0.7 | 94.9 ± 1.4 | 48.1 ± 4.3 | 98.4 ± 0.7 | 100 | 63.8 ± 3.4 |

| 21 | 55.5 ± 2.0 | 35.0 ± 0.7 | 45.0 ± 1.0 | 73.4 ± 0.8 | 47.3 ± 0.5 | 33.1 ± 0.5 |

| 22 | 60.7 ± 2.4 | 76.4 ± 0.7 | 30.8 ± 0.8 | 97.2 ± 0.7 | 34.6 ± 0.6 | 39.6 ± 0.7 |

| 23 | 75.4 ± 0.7 | 69.1 ± 0.7 | 80.8 ± 1.6 | 97.6 ± 0.8 | 100 | 32.4 ± 0.7 |

| 24 | 93.7 ± 0.6 | 84.9 ± 1.2 | 25.8 ± 1.3 | 92.7 ± 0.7 | 67.2 ± 3.4 | 74.3 ± 0.6 |

| 25 | 41.5 ± 1.1 | 19.3 ± 0.7 | 15.8 ± 2.5 | 100 | 49.4 ± 0.6 | 50.7 ± 0.7 |

| 26 | 76.6 ± 1.1 | 62.1 ± 0.7 | 98.9 ± 0.8 | 100 | 100 | 91.9 ± 0.5 |

| 27 | 69.9 ± 2.6 | 46.4 ± 0.7 | 89.7 ± 2.2 | 95.2 ± 0.9 | 90.6 ± 0.6 | 56.3 ± 0.7 |

| 28 | 44.5 ± 2.0 | 39.3 ± 0.7 | 42.5 ± 1.6 | 78.0 ± 2.2 | 79.4 ± 0.6 | 45.8 ± 0.8 |

| 29 | <10 | 20.0 ± 1.0 | <10 | 100 | 14 ± 0.5 | <10 |

| 30 | 61.7 ± 0.7 | 20.7 ± 0.7 | 33.1 ± 0.6 | 100 | 39.4 ± 0.6 | 54.9 ± 0.7 |

| 31 | <10 | 23.7 ± 4.4 | 27.5 ± 4.4 | 96.8 ± 1.1 | 18.2 ± 1.1 | 22.2 ± 2.3 |

| 32 | 46.6 ± 1.1 | 54.6 ± 1.1 | 78.9 ± 2.6 | 83.9 ± 0.9 | 70.6 ± 1.4 | 60.2 ± 2.6 |

| 33 | 55.2 ± 3.2 | 53.3 ± 1.4 | 68.9 ± 1.9 | 92.5 ± 6.3 | 70.4 ± 1.3 | 48.4 ± 1.8 |

| 34 | 50.5 ± 1.5 | 70.7 ± 0.6 | 85.5 ± 1.1 | 100 | 65.9 ± 1.6 | 45.1 ± 1.4 |

| 35 | 14.1 ± 2.0 | 41.1 ± 0.8 | 24.8 ± 1.1 | 100 | 39.6 ± 1.7 | 29.3 ± 1.6 |

| 36 | 57.8 ± 3.3 | 86.1 ± 1.2 | 91.2 ± 0.5 | 100 | 100 | 92.0 ± 1.9 |

| pyrimethanil | 75.1 ± 1.0 | 43.1 ± 0.7 | 32.6 ± 1.8 | 89.4 ± 0.7 | 15.2 ± 1.1 | 27.2 ± 1.5 |

| Pathogen | Compd. | EC50 | Pathogen | Compd. | EC50 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B. Cinerea | 6 | 3.31 ± 0.18 | R. solani | 1 | 0.20 ± 0.07 |

| 20 | 4.36 ± 0.10 | 2 | 0.19 ± 0.04 | ||

| 26 | 4.90 ± 0.05 | 3 | 0.58 ± 0.03 | ||

| pyrimethanil | 3.39 ± 0.22 | 4 | 0.17 ± 0.11 | ||

| A. solani | 20 | 4.42 ± 0.09 | 5 | 0.26 ± 0.07 | |

| carbendazim | 5.46 ± 0.14 | 6 | 0.58 ± 0.16 | ||

| G. zeae | 1 | 0.94 ± 0.03 | 7 | 0.65 ± 0.08 | |

| 2 | 1.22 ± 0.06 | 9 | 0.84 ± 0.20 | ||

| 7 | 1.21 ± 0.02 | 10 | 2.22 ± 0.06 | ||

| 15 | 0.87 ± 0.03 | 11 | 1.41 ± 0.11 | ||

| 16 | 1.17 ± 0.08 | 12 | 1.05 ± 0.04 | ||

| 18 | 1.77 ± 0.04 | 13 | 0.20 ± 0.01 | ||

| 28 | 1.27 ± 0.06 | 14 | 0.39 ± 0.08 | ||

| 38 | 1.54 ± 0.09 | 15 | 0.16 ± 0.04 | ||

| pyrimethanil | 2.20 ± 0.11 | 16 | 0.36 ± 0.12 | ||

| C. orbiculare | 1 | 1.84 ± 0.07 | 17 | 0.32 ± 0.23 | |

| 2 | 1.32 ± 0.06 | 18 | 0.52 ± 0.03 | ||

| 3 | 3.35 ± 0.22 | 19 | 0.33 ± 0.11 | ||

| 6 | 8.39 ± 0.15 | 20 | 0.54 ± 0.14 | ||

| 15 | 1.01 ± 0.11 | 21 | 0.15 ± 0.09 | ||

| 16 | 1.35 ± 0.07 | 22 | 0.47 ± 0.04 | ||

| 18 | 3.84 ± 0.10 | 23 | 0.54 ± 0.14 | ||

| 20 | 3.86 ± 0.13 | 24 | 0.66 ± 0.11 | ||

| 23 | 1.36 ± 0.14 | 25 | 0.68 ± 0.05 | ||

| 26 | 1.61 ± 0.12 | 26 | 0.55 ± 0.05 | ||

| 27 | 1.03 ± 0.11 | 27 | 0.18 ± 0.04 | ||

| 36 | 2.23 ± 0.08 | 28 | 0.15 ± 0.08 | ||

| carbendazim | 2.32 ± 0.11 | 29 | 1.21 ± 0.11 | ||

| A. alternata | 1 | 1.54 ± 0.12 | 30 | 1.05 ± 0.09 | |

| 2 | 10.75 ± 0.05 | 31 | 0.80 ± 0.11 | ||

| 3 | 7.35 ± 0.21 | 32 | 0.23 ± 0.05 | ||

| 6 | 12.09 ± 0.05 | 33 | 0.38 ± 0.07 | ||

| 7 | 1.99 ± 0.08 | 34 | 0.36 ± 0.05 | ||

| 16 | 4.82 ± 0.25 | 35 | 0.55 ± 0.23 | ||

| 28 | 2.85 ± 0.06 | 36 | 0.50 ± 0.15 | ||

| pyrimethanil | 2.07 ± 0.15 | pyrimethanil | 0.21 ± 0.10 |

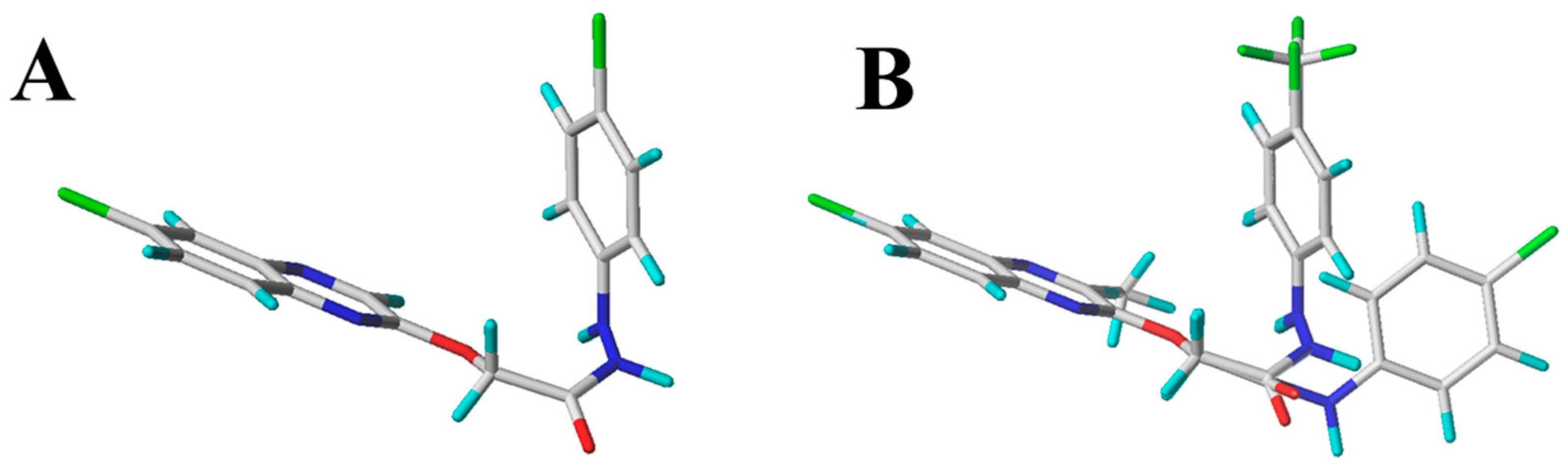

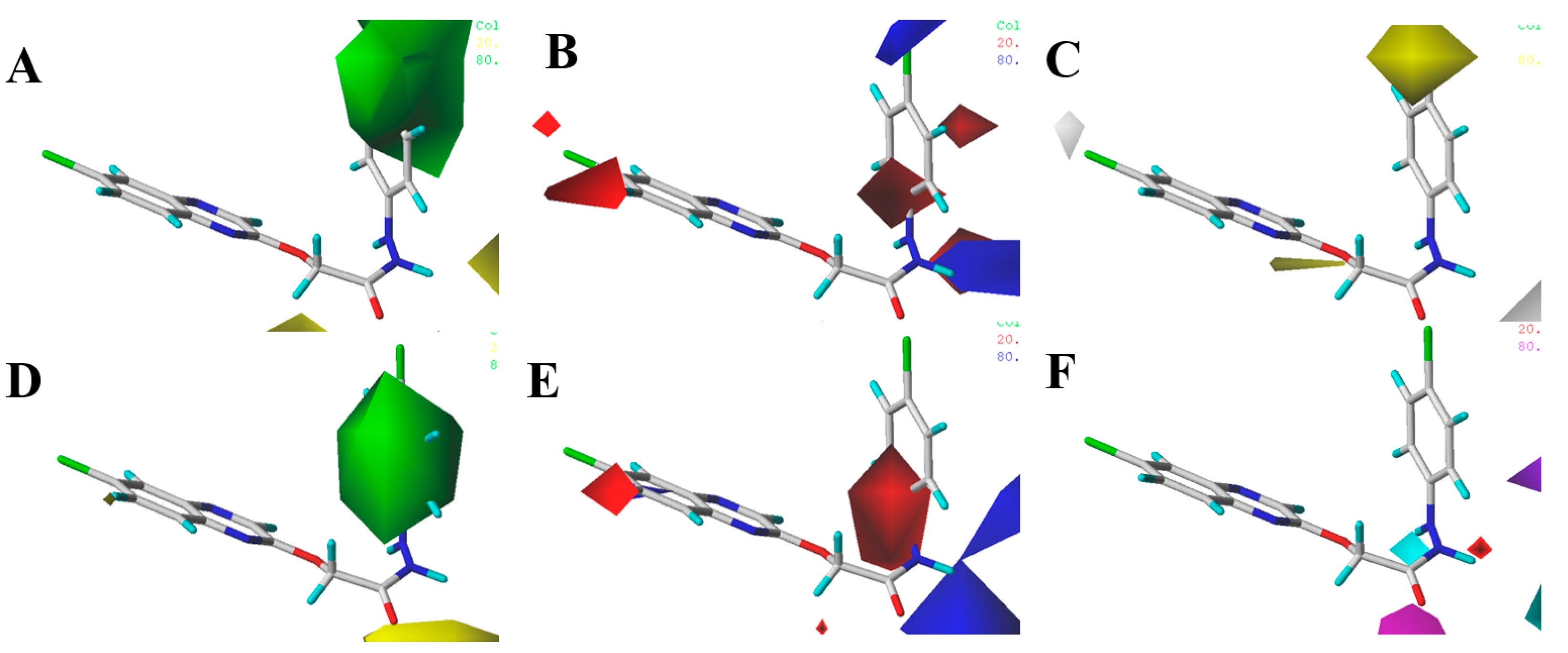

| Statistical Parameter | CoMFA | CoMSIA | Validation Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|

| q2 a | 0.843 | 0.845 | >0.5 |

| r2 b | 0.997 | 0.985 | >0.8 |

| s c | 0.025 | 0.038 | |

| F d | 144.141 | 125.981 | |

| ONC e | 14 | 7 |

| Compd. | EC50 | pEC50 | CoMFA | CoMSIA | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pred pEC50 b | Residual | Pred pEC50 b | Residual | |||

| 1 * | 0.20 ± 0.07 | 6.311 | 6.295 | 0.016 | 6.324 | −0.013 |

| 2 | 0.19 ± 0.04 | 6.343 | 6.382 | −0.039 | 6.375 | −0.032 |

| 3 | 0.58 ± 0.03 | 5.728 | 5.727 | 0.001 | 5.759 | −0.031 |

| 4 | 0.17 ± 0.11 | 6.322 | 6.271 | 0.051 | 6.341 | −0.019 |

| 5 * | 0.26 ± 0.07 | 6.071 | 6.376 | −0.305 | 6.29 | −0.219 |

| 6 | 0.58 ± 0.16 | 5.729 | 6.193 | −0.464 | 5.697 | 0.032 |

| 9 * | 2.22 ± 0.06 | 5.645 | 6.209 | −0.564 | 5.6 | 0.045 |

| 12 | 1.05 ± 0.04 | 5.621 | 5.933 | −0.312 | 5.973 | −0.352 |

| 13 | 0.20 ± 0.01 | 6.015 | 6.022 | −0.007 | 6.034 | −0.019 |

| 14 * | 0.39 ± 0.08 | 6.056 | 6.049 | 0.007 | 6.036 | 0.02 |

| 15 | 0.12 ± 0.04 | 6.098 | 5.977 | 0.121 | 5.967 | 0.131 |

| 16 | 0.36 ± 0.12 | 5.974 | 5.967 | 0.007 | 5.978 | −0.004 |

| 17 | 0.32 ± 0.23 | 6.004 | 6.013 | −0.009 | 5.999 | 0.005 |

| 18 | 0.52 ± 0.03 | 5.792 | 5.800 | −0.008 | 5.787 | 0.005 |

| 19 | 0.33 ± 0.11 | 6.053 | 6.052 | 0.001 | 6.061 | −0.008 |

| 20 * | 0.54 ± 0.14 | 5.78 | 5.77 | 0.01 | 5.774 | 0.006 |

| 22 | 0.47 ± 0.04 | 5.933 | 5.714 | 0.219 | 5.62 | 0.313 |

| 23 * | 0.54 ± 0.14 | 5.798 | 5.805 | −0.007 | 5.819 | −0.021 |

| 24 | 0.66 ± 0.11 | 5.714 | 5.706 | 0.008 | 5.707 | 0.007 |

| 25 * | 0.68 ± 0.05 | 5.707 | 5.72 | −0.013 | 5.673 | 0.034 |

| 26 | 0.55 ± 0.05 | 5.796 | 6.184 | −0.388 | 6.253 | −0.457 |

| 27 | 0.18 ± 0.04 | 6.308 | 6.301 | 0.007 | 6.322 | −0.014 |

| 28 * | 0.15 ± 0.08 | 6.422 | 6.391 | 0.031 | 6.356 | 0.066 |

| 29 | 1.21 ± 0.11 | 5.527 | 5.644 | −0.117 | 5.561 | −0.034 |

| 30 | 1.05 ± 0.09 | 5.540 | 5.554 | −0.014 | 5.62 | −0.08 |

| 31 | 0.80 ± 0.11 | 5.693 | 5.689 | 0.004 | 5.688 | 0.005 |

| 32 | 0.23 ± 0.05 | 6.242 | 6.048 | 0.194 | 5.992 | 0.25 |

| 33 * | 0.38 ± 0.07 | 6.059 | 6.33 | −0.271 | 6.045 | 0.014 |

| 34 | 0.36 ± 0.05 | 6.092 | 6.33 | −0.238 | 6.317 | −0.225 |

| 35 * | 0.55 ± 0.23 | 5.839 | 5.84 | −0.001 | 5.846 | −0.007 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Teng, P.; Li, Y.; Fang, R.; Zhu, Y.; Dai, P.; Zhang, W. Design, Synthesis, Antifungal Activity, and 3D-QSAR Study of Novel Quinoxaline-2-Oxyacetate Hydrazide. Molecules 2024, 29, 2501. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29112501

Teng P, Li Y, Fang R, Zhu Y, Dai P, Zhang W. Design, Synthesis, Antifungal Activity, and 3D-QSAR Study of Novel Quinoxaline-2-Oxyacetate Hydrazide. Molecules. 2024; 29(11):2501. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29112501

Chicago/Turabian StyleTeng, Peng, Yufei Li, Ruoyu Fang, Yuchuan Zhu, Peng Dai, and Weihua Zhang. 2024. "Design, Synthesis, Antifungal Activity, and 3D-QSAR Study of Novel Quinoxaline-2-Oxyacetate Hydrazide" Molecules 29, no. 11: 2501. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29112501

APA StyleTeng, P., Li, Y., Fang, R., Zhu, Y., Dai, P., & Zhang, W. (2024). Design, Synthesis, Antifungal Activity, and 3D-QSAR Study of Novel Quinoxaline-2-Oxyacetate Hydrazide. Molecules, 29(11), 2501. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29112501