Hydroxyl Group as the ‘Bridge’ to Enhance the Single-Molecule Conductance by Hyperconjugation

Abstract

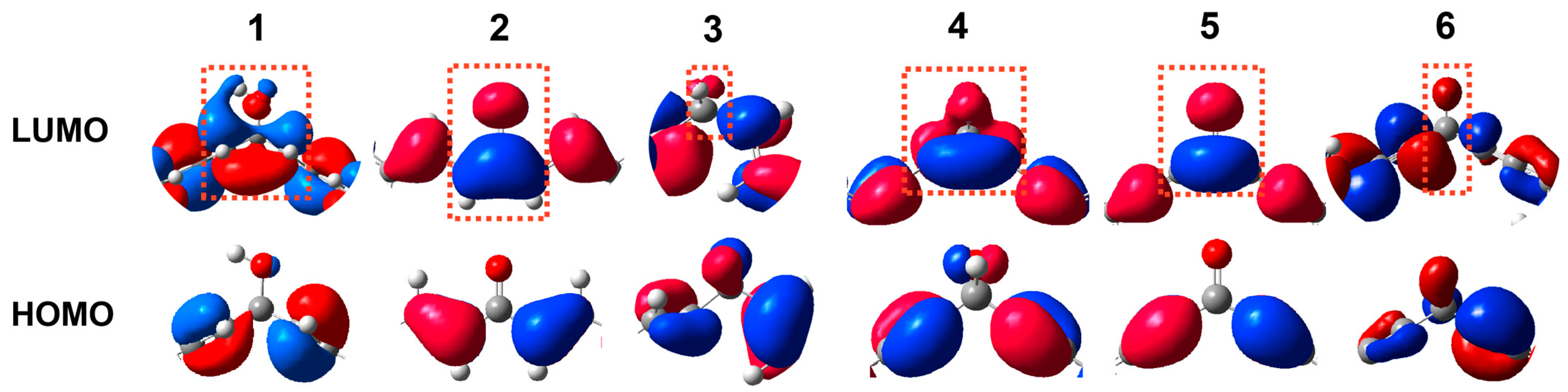

1. Introduction

2. Results

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. General

Synthesis and Characterizations

3.2. STM-BJ Method

3.3. Computational Details

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jia, C.; Guo, X. Molecule–electrode interfaces in molecular electronic devices. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 5642–5660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, T.A.; Neupane, M.; Steigerwald, M.L.; Venkataraman, L.; Nuckolls, C. Chemical principles of single-molecule electronics. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2016, 1, 16002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, J.; Zou, Y.; Wang, P.; Qin, Z.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, C.; et al. Dibenzothiophene Sulfone-Based Ambipolar-Transporting Blue-Emissive Organic Semiconductors towards Simple-Structured Organic Light-Emitting Transistors. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202308146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, W.; Li, J.; Li, G.; Jia, C.; Guo, X. Single-molecule non-volatile memories: An overview and future perspectives. J. Mater. Chem. C 2024, 12, 751–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Huang, X.; Wang, F.; Hong, W. Quantum Interference Effects in Charge Transport through Single-Molecule Junctions: Detection, Manipulation, and Application. Acc. Chem. Res. 2018, 52, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vazquez, H.; Skouta, R.; Schneebeli, S.; Kamenetska, M.; Breslow, R.; Venkataraman, L.; Hybertsen, M.S. Probing the conductance superposition law in single-molecule circuits with parallel paths. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2012, 7, 663–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardamone, D.M.; Stafford, C.A.; Mazumdar, S. Controlling Quantum Transport through a Single Molecule. Nano Lett. 2006, 6, 2422–2426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Hou, S.; Wu, Q.; Jiang, F.; Zhou, P.; Zhang, L.; Jiao, Y.; Song, B.; Guo, Q.-H.; Chen, X.-Y.; et al. Promotion and suppression of single-molecule conductance by quantum interference in macrocyclic circuits. Matter 2021, 4, 3662–3676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Zheng, H.; Hu, C.; Cai, K.; Jiao, Y.; Zhang, L.; Jiang, F.; Roy, I.; Qiu, Y.; Shen, D.; et al. Giant Conductance Enhancement of Intramolecular Circuits through Interchannel Gating. Matter 2020, 2, 378–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, W.Y.; Bi, W.; Li, L.; Jung, I.H.; Yu, L. Edge-on Gating Effect in Molecular Wires. Nano Lett. 2015, 15, 958–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Louie, S.; Evans, A.M.; Meirzadeh, E.; Nuckolls, C.; Venkataraman, L. Topological Radical Pairs Produce Ultrahigh Conductance in Long Molecular Wires. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 2492–2498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Low, J.Z.; Wilhelm, J.; Liao, G.; Gunasekaran, S.; Prindle, C.R.; Starr, R.L.; Golze, D.; Nuckolls, C.; Steigerwald, M.L.; et al. Highly conducting single-molecule topological insulators based on mono- and di-radical cations. Nat. Chem. 2022, 14, 1061–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, S.; Mao, J.-C.; Chen, L.; Ding, S.; Luo, W.; Zhou, X.-S.; Qin, A.; Zhao, Z.; Tang, B.Z. Remarkable Multichannel Conductance of Novel Single-Molecule Wires Built on Through-Space Conjugated Hexaphenylbenzene. Nano Lett. 2018, 18, 4200–4205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, S.; Shen, P.; Li, J.; Zhao, Z.; Tang, B.Z. Giant single-molecule conductance enhancement achieved by strengthening through-space conjugation with thienyls. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 2021, 2, 100364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, P.; Huang, M.; Qian, J.; Li, J.; Ding, S.; Zhou, X.S.; Xu, B.; Zhao, Z.; Tang, B.Z. Achieving Efficient Multichannel Conductance in Through-Space Conjugated Single-Molecule Parallel Circuits. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 4581–4588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alabugin, I.V.; Kuhn, L.; Krivoshchapov, N.V.; Mehaffy, P.; Medvedev, M.G. Anomeric effect, hyperconjugation and electrostatics: Lessons from complexity in a classic stereoelectronic phenomenon. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 10212–10252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vedernikova, I.; Salahub, D.; Proynov, E. DFT study of hyperconjugation effects on the charge distribution in pyrogallol. J. Mol. Struct. Theochem 2003, 663, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tostes, J.G.R.; Seidl, P.R.; Soto, M.M.; Carneiro, J.W.d.M.; Lie, S.K.; Taft, C.A.; Brown, W.; Lester, W.A. Ab initio studies of hyperconjugation effects on charge distribution in tetracyclododecane alcohols. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1995, 237, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alabugin, I.V.; dos Passos Gomes, G.; Abdo, M.A. Hyperconjugation. Wires Comput. Mol. Sci. 2018, 9, e1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paddon-Row, M.N. Some aspects of orbital interactions through bonds: Physical and chemical consequences. Acc. Chem. Res. 2002, 15, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Jiang, X.-L.; Chen, S.; Hong, W.; Li, J.; Xia, H. Stereoelectronic Modulation of a Single-Molecule Junction through a Tunable Metal–Carbon dπ–pπ Hyperconjugation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 10404–10410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, T.A.; Li, H.; Steigerwald, M.L.; Venkataraman, L.; Nuckolls, C. Stereoelectronic switching in single-molecule junctions. Nat. Chem. 2015, 7, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salthouse, R.J.; Hurtado-Gallego, J.; Grace, I.M.; Davidson, R.; Alshammari, O.; Agraït, N.; Lambert, C.J.; Bryce, M.R. Electronic Conductance and Thermopower of Cross-Conjugated and Skipped-Conjugated Molecules in Single-Molecule Junctions. J. Phys. Chem. C 2023, 127, 13751–13758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Wong, Y.L.; Zeller, M.; Hunter, A.D.; Xu, Z. Pd Uptake and H2S Sensing by an Amphoteric Metal–Organic Framework with a Soft Core and Rigid Side Arms. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 14438–14442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Wu, Q.; Dong, Z.; Xu, J.; Yang, Z. Rhodium-Catalyzed 1,1-Hydroacylation of Thioacyl Carbenes with Alkynyl Aldehydes and Subsequent Cyclization. Org. Lett. 2019, 21, 3594–3599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praveen Rao, P.N.; Chen, Q.-H.; Knaus, E.E. Synthesis and Structure–Activity Relationship Studies of 1,3-Diarylprop-2-yn-1-ones: Dual Inhibitors of Cyclooxygenases and Lipoxygenases. J. Med. Chem. 2006, 49, 1668–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, A.K.; Fatima, K.; Dudi, R.K.; Tabassum, M.; Iqbal, H.; Kumar, Y.; Luqman, S.; Mondhe, D.M.; Chanda, D.; Khan, F.; et al. Antiproliferative activity of diarylnaphthylpyrrolidine derivative dual target inhibition. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 188, 111986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.G.; Liu, J.; Zeng, P.L.; Dong, Z.B. Synthesis of α, α′-bis(Substituted Benzylidene)Ketones Catalysed by a SOCl2/EtOH reagent. J. Chem. Res. 2019, 2004, 55–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.M.; Jiang, Y.X.; Wang, J.Y.; Chen, Z.N.; Hou, S.M.; Zhang, Q.C. Effectively Enhancing the Conductance of Asymmetric Molecular Wires by Aligning the Energy Level and Symmetrizing the Coupling. Langmuir 2024, 40, 3759–3765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Lv, Y.; Song, K.; Song, X.; Zang, H.; Du, P.; Zang, Y.; Zhu, D. Cleavage of non-polar C(sp2)–C(sp2) bonds in cycloparaphenylenes via electric field-catalyzed electrophilic aromatic substitution. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Petersson, G.A.; Nakatsuji, H.; et al. Gaussian 16 Rev. B.01; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, H.; Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Li, S.; Hou, S. Understanding Quantum Interference in Molecular Devices Based on Molecular Conductance Orbitals. J. Phys. Chem. C 2022, 126, 17424–17433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.-S.; Chen, L.-C.; Wang, J.-Y.; Duan, P.; Pan, Z.-Y.; Qu, K.; Hong, W.; Chen, Z.-N.; Zhang, Q.-C. Exploring a Linear Combination Feature for Predicting the Conductance of Parallel Molecular Circuits. Nano Lett. 2023, 23, 9399–9405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, C.J.; Liu, S.X. A Magic Ratio Rule for Beginners: A Chemist’s Guide to Quantum Interference in Molecules. Chemistry 2018, 24, 4193–4201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, C.J. Basic concepts of quantum interference and electron transport in single-molecule electronics. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 875–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.C.; Zheng, J.; Liu, J.; Gong, X.T.; Chen, Z.Z.; Guo, R.X.; Huang, X.; Zhang, Y.P.; Zhang, L.; Li, R.; et al. Nonadditive Transport in Multi-Channel Single-Molecule Circuits. Small 2020, 16, e2002808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tostes, J.R.; Seidl, P.R.; Taft, C.A.; Lie, S.K.; Carneiro, J.W.d.M.; Brown, W.; Lester, W.A. Carbon–carbon and carbon–hydrogen hyperconjugation in neutral alcohols. J. Mol. Struct. Theochem 1996, 388, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nokhbeh, S.R.; Gholizadeh, M.; Salimi, A.; Sparkes, H.A. Synthesis, crystal structure, Hirshfeld surface analysis, DFT calculations and characterization of 1,3-propanediylbis(triphenylphosphonium) monotribromide as brominating agent of double bonds and phenolic rings. J. Mol. Struct. 2020, 1206, 127700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, K.P.; Spivey, D.W.; Loya, E.K.; Kellon, J.E.; Taylor, L.M.; McConville, M.R. Photochemical locking and unlocking of an acyl nitroso dienophile in the Diels–Alder reaction. Tetrahedron Lett. 2016, 57, 1296–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Tao, N.J. Measurement of Single-Molecule Resistance by Repeated Formation of Molecular Junctions. Science 2003, 301, 1221–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Z.; Dong, G.; Shang, C.; Li, R.; Gao, T.; Lin, L.; Duan, H.; Li, X.; Bai, J.; Lai, Y.; et al. XMe-Xiamen Molecular Electronics Code: An Intelligent and Open-Source Data Analysis Tool for Single-Molecule Conductance Measurements. Chin. J. Chem. 2023, 42, 317–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, W.; Manrique, D.Z.; Moreno-García, P.; Gulcur, M.; Mishchenko, A.; Lambert, C.J.; Bryce, M.R.; Wandlowski, T. Single Molecular Conductance of Tolanes: Experimental and Theoretical Study on the Junction Evolution Dependent on the Anchoring Group. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 2292–2304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lv, X.; Li, C.; Guo, M.-M.; Hong, W.; Chen, L.-C.; Zhang, Q.-C.; Chen, Z.-N. Hydroxyl Group as the ‘Bridge’ to Enhance the Single-Molecule Conductance by Hyperconjugation. Molecules 2024, 29, 2440. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29112440

Lv X, Li C, Guo M-M, Hong W, Chen L-C, Zhang Q-C, Chen Z-N. Hydroxyl Group as the ‘Bridge’ to Enhance the Single-Molecule Conductance by Hyperconjugation. Molecules. 2024; 29(11):2440. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29112440

Chicago/Turabian StyleLv, Xin, Chang Li, Meng-Meng Guo, Wenjing Hong, Li-Chuan Chen, Qian-Chong Zhang, and Zhong-Ning Chen. 2024. "Hydroxyl Group as the ‘Bridge’ to Enhance the Single-Molecule Conductance by Hyperconjugation" Molecules 29, no. 11: 2440. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29112440

APA StyleLv, X., Li, C., Guo, M.-M., Hong, W., Chen, L.-C., Zhang, Q.-C., & Chen, Z.-N. (2024). Hydroxyl Group as the ‘Bridge’ to Enhance the Single-Molecule Conductance by Hyperconjugation. Molecules, 29(11), 2440. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29112440