Abstract

Oxalate is a divalent organic anion that affects many biological and commercial processes. It is derived from plant sources, such as spinach, rhubarb, tea, cacao, nuts, and beans, and therefore is commonly found in raw or processed food products. Oxalate can also be made endogenously by humans and other mammals as a byproduct of hepatic enzymatic reactions. It is theorized that plants use oxalate to store calcium and protect against herbivory. Clinically, oxalate is best known to be a major component of kidney stones, which commonly contain calcium oxalate crystals. Oxalate can induce an inflammatory response that decreases the immune system’s ability to remove renal crystals. When formulated with platinum as oxaliplatin (an anticancer drug), oxalate has been proposed to cause neurotoxicity and nerve pain. There are many sectors of industry that are hampered by oxalate, and others that depend on it. For example, calcium oxalate is troublesome in the pulp industry and the alumina industry as it deposits on machinery. On the other hand, oxalate is a common active component of rust removal and cleaning products. Due to its ubiquity, there is interest in developing efficient methods to quantify oxalate. Over the past four decades, many diverse methods have been reported. These approaches include electrochemical detection, liquid chromatography or gas chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry, enzymatic degradation of oxalate with oxalate oxidase and detection of hydrogen peroxide produced, and indicator displacement-based methods employing fluorescent or UV light-absorbing compounds. Enhancements in sensitivity have been reported for both electrochemical and mass-spectrometry-based methods as recently as this year. Indicator-based methods have realized a surge in interest that continues to date. The diversity of these approaches, in terms of instrumentation, sample preparation, and sensitivity, has made it clear that no single method will work best for every purpose. This review describes the strengths and limitations of each method, and may serve as a reference for investigators to decide which approach is most suitable for their work.

1. Introduction

Oxalate is a divalent organic anion (Figure 1) that plays a role in a wide variety of fields. It can be derived from plant sources, formed as a byproduct in some physiological reactions, and is even formulated with some drugs currently on the international market. It is best known as a major component of kidney stones (nephrolithiasis), but also plays a role in oxidative stress and inflammation in humans. It is also an important compound in plant physiology and defense [1]. Due to its diverse roles and impact on society, there has been great interest in quantifying oxalate for many years. Below, we provide more detail on various fields where oxalate is involved, and then describe the analytical methods used for quantifying oxalate.

Figure 1.

Structure of the oxalate ion.

1.1. Oxalate in Clinical Science

The incidence of nephrolithiasis in the United States is on the rise and is currently estimated to be similar to the prevalence of diabetes. The incidence of nephrolithiasis is 10.6% in men and 7.1% in women [2], whereas the prevalence of diabetes is 10.5% [3]. Calcium oxalate is the cause of over 70–80% of patients presenting with renal stones [2,4]. Oxalate is found in human blood at levels typically around 1–5 µM; however, the oxalate level in urine is typically 100 times higher. The supersaturation of renal ultrafiltrate and urine with oxalate is crucial for the formation of renal stones, which usually attach to subepithelial plaques (Randall’s plaques) or apatite deposits in the collecting ducts. Oxalate is passively absorbed in the human gut and also absorbed via carrier-mediated mechanisms [5]. Besides the diet, oxalate is formed in humans by the liver as an end product in glyoxylate metabolism by hepatic peroxisomes. Dysfunction of the glyoxylate metabolic pathway is the cause of primary hyperoxaluria type 1, which is a rare autosomal recessive disorder [6,7]. Dysfunction of SLC26A6 (also known as PAT1), a secretory intestinal transporter, has been correlated with increased urinary excretion in mice. SLC26A6 dysfunction has also been shown to cause a net increase in oxalate absorption [8]. Increased blood oxalate causes an increased renal burden and urinary excretion. Studies show that patients who have undergone malabsorptive bariatric surgery, especially Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, approximately double their risk of nephrolithiasis [9]. A link between oxalate and the renin–angiotensin system pathway has also been found showing that angiotensin II can increase intestinal secretion of oxalate, although renal insufficiency may be necessary to induce this interaction [5,10].

1.2. Inflammation/Immunology

Exposure of renal epithelial cells to oxalate can incite an inflammatory response via an increase in reactive oxygen species as well as a decrease in glutathione levels. Oxalate exposure has also been shown to impair DNA synthesis and cause cell death. Oxalate impairs monocytes’ ability to differentiate into macrophages, which are important for renal crystal removal. Increased dietary intake of oxalate has been shown to alter immune responses in healthy patients [2].

1.3. Drugs and Nutrients Containing Oxalate or Metabolized to Oxalate (Oxaliplatin, Vitamin C)

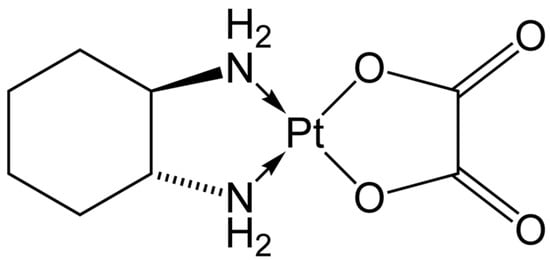

Oxaliplatin is a platinum-containing anticancer medication (Figure 2) commonly used to treat a variety of cancers including breast, colorectal, and lung cancer. Once oxaliplatin is metabolized by the body, oxalate ions are one of two major metabolites that are formed. These oxalate ions are linked to negative side effects of the drug including severe nerve pain characterized by allodynia (hypersensitivity to painful stimuli) [11]. Oxalate is hypothesized to cause this neurotoxicity through two mechanisms: chelation of calcium by oxalate, which affects calcium-sensitive voltage-gated sodium channels; and an indirect action on voltage-gated sodium channels where oxalate alters intracellular calcium-dependent regulatory mechanisms [12]. Furthermore, oxalate has also been proven to decrease the maximum sodium current peak similarly to the decrease seen from oxaliplatin.

Figure 2.

Structure of oxaliplatin.

Ascorbic acid (vitamin C) is an essential component of the human diet as it cannot be synthesized endogenously. It plays important roles in several physiological functions including the synthesis of neurotransmitters and collagen, protein metabolism, immune function, and nonheme iron absorption, and it is also an antioxidant [13]. The breakdown of ascorbic acid by the body results in oxalate formation. Although additional studies are warranted, there have been multiple reports of ascorbic acid increasing a person’s risk of kidney stones [14]. One study from Sweden showed that supplemental ascorbic acid (around 1000 mg) intake doubled the risk of kidney stones [15].

1.4. Oxalate in Food Science

Calcium oxalate crystals are found in all taxonomic levels of photosynthetic organisms. Plants such as spinach, rhubarb, and tea have high levels of oxalate [6]. Chocolate derived from tropical cacao trees, strawberries, nuts, wheat bran, sweet potatoes, black olives, and most dry beans are also high in oxalate [5,16]. There have been problems reporting the oxalate content of foods due to inaccuracies of the analytical methods used. Of note, variability in oxalate between food samples also contributes to the challenge of accurately measuring oxalate. For example, changes in growth conditions, plant variety, and developmental stage of the plant are known to affect oxalate content [16]. Due to this variability, achieving a broad linear range for quantifying oxalate is essential.

1.5. Relevance of Oxalate in Plants/Fungi

Although the role of oxalate in plants has not been completely elucidated, it has been suggested that oxalate is involved in seed germination, calcium storage, detoxification, structural strength, and repelling insects [16]. Calcium oxalate is also important in plants to protect against herbivory and phytotoxins [17,18]. Many fungal pathogens secrete oxalate when they attack plants in order to weaken the plant cell walls to facilitate their degradation by fungal enzymes [19].

1.6. Oxalate in Industrial Processes

Oxalate is found in, or produced from, some household and industrial products/processes. For example, ethylene glycol is a chemical commonly used in antifreeze and coolant. There have been multiple case reports confirming that ethylene glycol toxicity causes hyperoxalemia, hyperoxaluria, and calcium oxalate crystal formation in the urine because oxalate is a metabolic product of ethylene glycol [20]. SerVaas Laboratories Inc. reports that the core ingredient in Bar Keepers Friend, a common cleaning product, is oxalic acid [21]. In alumina refineries, where bauxite ore is refined to alumina (Al2O3), sodium oxalate is a major impurity that coprecipitates with aluminum hydroxide. This sodium oxalate is then removed to both remove the impurity from the constantly recycled processing liquor and to recover sodium [22]. Calcium oxalate is troublesome in the pulp (paper) industry. Oxalic acid is found naturally in wood and, as it goes through the bleaching process, it deposits on machinery, decreasing product quality and profitability [23].

1.7. Need for a Review on the Current State of Analytical Methods for Oxalate/Oxalic Acid

An updated review of analytical methods for quantifying oxalate/oxalic acid is timely, as new approaches have been reported as recently as this year. Enhancements in sensitivity have been realized, taking advantage of modern instrumentation. Moreover, new colorimetric or fluorimetric methods have been developed. We review the strengths and limitations of both modern and older methods. The table provided in this review gives a comprehensive account of figures of merit (i.e., limit of detection, limit of quantification, linear range, recovery, and precision), approaches to sample preparation, modes of detection of oxalate/oxalic acid, and noteworthy strengths and limitations.

2. Methods for Detection and Quantification of Oxalate

Many diverse methods for detecting and quantifying oxalate have been reported over the past four decades. De Castro noted that a variety of methods were developed leading up to 1988, many of which have been improved and are used, in some form, currently [24]. The updated methods are first introduced in this review, and then more detailed descriptions with references follow. A tabular summary, including limits of detection and quantification, and other figures of merit, is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Methods used for detection and quantification of oxalate. LOD, limit of detection; LOQ, limit of quantification; NR, not reported; RSD, relative standard deviation; CV, coefficient of variation.

Enzyme-based methods employing oxalate oxidase have realized a niche in commercial oxalate detection kits due to their simplicity and relatively common instrumentation for reading samples. There appears to be some promise in conjugating oxalate-degrading enzymes with solid supports, as they can be washed and reused. From a commercialization perspective, it may be useful to develop a device with oxalate oxidase coupled to beads or a monolithic solid in order to circumvent some sample preparation steps associated with enzyme dilution. Alternatively, success has been achieved using sensors based on the injection of the recognition element (SIRE) approach, wherein small quantities of oxalate oxidase are added for one-time use.

Liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC-MS) has historically not been a method of choice for oxalate due to its low sensitivity compared to other methods, and compared to other analytes using LC-MS. Perhaps the primary advantage is the more confident identification of oxalate using MS/MS, which may be acceptable if the oxalate content is above the limit of quantification. More recent reports have demonstrated improved sensitivity with LC-MS/MS, giving this approach a potential role in laboratories with access to the instrumentation. GC-MS has also not realized much utility in oxalate detection, possibly due to the time required for derivatization. However, investigators continue to explore GC-MS methods for oxalate detection.

The most sensitive oxalate detection methods to date are conductivity-based. These approaches do, however, often require corrections based on bulk solution conductivity changes, and loss of linearity at higher oxalate concentrations. In addition, the separation columns/capillaries coupled with electrochemical detection are often susceptible to fouling when real food or other biological samples are tested.

Finally, indicator displacement methods wherein oxalate turns on or turns off fluorescence, or alters UV absorbance, can be rapid and instrumentally simple, but are limited by the lack of specificity of the indicator.

Therefore, to determine which methodology is most suitable for quantifying oxalate, one must answer several questions first: What sensitivity is needed? What linear range is needed? How complicated is the sample matrix and what is the likelihood of interfering compounds? What instrumentation is available? What expertise is needed to employ the method? It is clear that no single method will be suitable for every investigation. A summary of the different approaches is presented in the following sections.

2.1. Enzyme-Based Methods

Enzyme-based detection of oxalate has been employed for several decades, and is used in several commercially available kits. In 1994, oxalate oxidase was immobilized in a column, where it was used to metabolize urine-borne oxalate into hydrogen peroxide and carbon dioxide [25]. In this flow-injection analysis method, chemiluminescence was measured from the reaction of hydrogen peroxide with luminol and hexacyanoferrate (III). The limit of detection was 34 µM (2.99 µg/mL), and linearity was confirmed up to 500 µM. The advantage of this method is that oxalate oxidase is specific for oxalate as a substrate; however, the disadvantage is that L-ascorbic acid was unable to be removed as an interfering substance due to its spontaneous conversion to oxalate.

In a related method published in 1997, HPLC was employed with an anion exchange column to resolve urinary oxalate prior to the reaction with immobilized oxalate oxidase isolated from barley [26]. The product, H2O2, was quantified using an amperometric detector. Oxalate eluted at 8.2 min, with values comparable to that of a commercial enzyme-based kit for several different concentrations. The limit of detection was 1.5 µM, which is more sensitive than the enzyme kits currently on the market (~20 µM reported). Linearity was reported up to at least 700 µM oxalate.

In 1999, urinary oxalate was measured with an alkylamine glass-bound oxalate oxidase purified from leaves of Amaranthus spinosus [27]. The hydrogen peroxide generated in the reaction was measured using 4-aminophenazone, phenol, and horseradish peroxidase. This reaction yielded a chromogen that absorbed 520 nm light. The results of this protocol were reportedly comparable to that of the commercially available kits. The limit of detection was 10.2 µM (0.9 µg/mL) and linearity was shown up to 300 µM. The limitations of this method, when first published, may be mitigated by improvements in biotechnology related to genetic engineering and protein purification. Some potential limitations are the use of glutaraldehyde in the immobilization process, and phenol in the detection step, which must be handled with some precautions, in addition to the 48-h reaction time for coupling oxalate oxidase to the beads. A major strength of the method is that the oxalate-oxidase-bound beads were reusable for at least 300 times after simple washing and storage in distilled water. If combined with modern technology, it appears feasible to construct a device, based on this method, for direct-to-consumer use.

In the following year, urinary oxalate was again detected after a reaction with oxalate oxidase; however, a synthetic compound, MnL(H2O)2(ClO4)2 (L = bis(2-pyridylmethyl)amino propionic acid), modeled off the catalase enzyme was thereafter reacted with hydrogen peroxide that had been generated from oxalate oxidase, forming a chromogen [29]. When absorbance of the chromogen was measured at 400 nm, the limit of detection for oxalate was found to be 2.0 µM (0.176 µg/mL). The linear range was 2.0 µM to 20 mM. It was also observed that adjusting the concentration of the catalase mimetic had a significant influence on the assay sensitivity. For example, 6 mM was required to detect the lower oxalate concentrations, whereas 1 mM was adequate for detecting 20 mM oxalate. A reported limitation of the method was that, in real urine samples, the calculated oxalate concentration was exceedingly higher than what is typically found. The investigators concluded that an additional substance (or additional substances) in urine may have reacted with the catalase mimetic to increase the absorbance at 400 nm. The identity of the interfering substance(s) was not determined. Although this limitation precludes the clinical use of the assay for oxalate quantification, revealing the limitation should lead to further exploration to determine the scope of reactivity of the catalase mimetic.

In 2003, oxalate oxidase was used with SIRE (sensors based on injection of the recognition element) technology to measure oxalate in urine [28]. In this method, oxalate oxidase was introduced into the reaction chamber by flow-injection, where it was free to react with oxalate from a sample. The hydrogen peroxide generated from the reaction was oxidized at the electrode, where the signal was then received. The advantage of this method is that oxalate oxidase is not immobilized to a support, but rather, it is used once in a small quantity before being discarded. This approach ensures that the enzyme is not degraded from thermal or other factors that can be troublesome for repeat-use biosensors. Moreover, the SIRE method allows the sample response to be easily measured in the absence of the enzyme, to correct for matrix-related interferences. The analysis time for this approach was 2–9 min, with a high selectivity imparted by oxalate oxidase, and a limit of detection of 20 µM (1.76 µg/mL). Linearity was shown up to 5 mM.

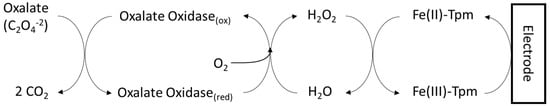

In 2012, a group of investigators reported coupling oxalate-oxidase-mediated oxalate metabolism with amperometric flow detection for quantifying oxalate in human urine [30]. In the study, oxalate oxidase was immobilized on a magnetic solid that was transiently retained on an electrode modified with Fe (III)-tris-(2-thiopyridone) borate. This complex served as a mediator that circumvented known issues with direct amperometric measurement of H2O2, such as interference from ascorbic acid and uric acid in urine. The reaction scheme is represented in Figure 3. The limit of detection was 11.4 µM (1.0 µg/mL) with a limit of quantification of 34.1µM. The advantages of this method are: no need for sample treatment, small sample volumes, and relatively simple equipment.

Figure 3.

Coupling of immobilized oxalate oxidase with amperometric detection. Oxalate oxidase was immobilized on magnetic solids, which were transiently retained on an electrode. Fe(III)-tris-(2-thiopyridone) borate (Fe(III)-Tpm) was used as a mediator between enzymatically generated hydrogen peroxide and the electrode.

2.2. Liquid Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry-Based Methods

Liquid chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry (LC-MS or LC-MS/MS) has become the method of choice for many analytes in food and drug analysis. High sensitivity and unparalleled selectivity are generally a major advantage of MS; however, until recently [33,34], the limit of quantification of oxalate using MS has not realized the sensitivity advantage. For example, in 2006, urinary oxalate was quantified using a weak anion exchange chromatography column and tandem mass spectrometry with electrospray ionization in the negative ion mode [31]. The limit of detection was 3.0 µM (0.264 µg/mL), and the limit of quantification was 100 µM. Linearity was demonstrated up to 2.2 mM. This limit of quantification is higher than that of some commercially available enzyme-based kits. However, one advantage of the method was a short (1.2 min) retention time with an adequate resolution from areas of ion suppression.

In 2018, a similar method was used, wherein a solid-phase extraction plate with weak anion exchange activity was employed in resolving urine oxalate [32]. When electrospray ionization in the negative ion mode was used with tandem mass spectrometry, a limit of quantification of 60 µM was found. Linearity was demonstrated up to 1.39 mM. Both this method and the former used 13C2 oxalate as an internal standard to correct for matrix-derived ion suppression. One advantage of the method is the ability to simultaneously quantify citrate, which may be useful due to its ability to sequester calcium and thus reduce the risk of calcium oxalate stones. Some limitations of the method include a lower sensitivity than other methods, and the time required for solid-phase extraction steps, including a drying phase, and several wash phases. These disadvantages can likely be circumvented with instrumental automation.

More recently, Mu et al. reported using ion chromatography coupled with triple quadrupole MS for quantifying oxalate, and nine other organic acids, in alcoholic beverages [33]. Liquor was analyzed directly after dilution and degassing, whereas wine was purified with graphitized carbon black solid-phase extraction before analysis. Separation was achieved with a Dionex IonPac AS11-HC anion analysis column with high capacity and hydrophilicity. A gradient elution of increasing KOH strength was used to allow the increased affinity of monovalent anions (e.g., lactate) in the beginning of the separation, and decreased affinity of di- and tri-valent anions (e.g., oxalate and citrate) at the end of the separation. A desalting suppressor was used to electrolyze water and allow the exchange of K+ for H+ at a cation exchange membrane prior to the detector to avoid fouling. The total run time was 35 min, with a 26 min retention time for oxalate. Electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry (ESI-MS/MS) in the negative ion mode was used with multiple reaction monitoring. Oxalate showed a linear response from 0.05 to 2 mg/L (r2 > 0.99). Recovery of oxalate ranged from 96.5% to 107.5%, with samples subjected to solid-phase extraction (i.e., wine) showing a tendency to exceed 100%. The cause of this apparent increase in recovery was not determined, but may theoretically be related to the removal of ionization-suppressing substances during the solid-phase extraction. Advantages of the method were simple sample preparation and high sensitivity. A potential limitation is that the instrumentation is not readily available to all investigators.

Li et al. recently reported using ion-pairing reversed-phase (IP-RP) LC-MS/MS for the simultaneous quantitation of oxalate and citrate in urine and serum [34]. The method demonstrated linearity from 0.25 to 1000 µM, with a correlation coefficient > 0.99. Sample preparation was simple, involving dilution with water prior to deproteinization with methanol, then evaporation and reconstitution of the supernatant with water. 13C2 oxalate was used as a “surrogate analyte”, as a true blank matrix was not feasible. That is, oxalate and citrate could not be reliably removed from the rat serum and urine used for the method validation. Multiple ion-pairing reagents and buffers were tested for the optimization of the protocol. Recovery of oxalate from urine was 90 to 98%, while that from serum was 96 to 102%. There were no major matrix effects, with a maximum signal suppression of 7.28% found for the highest oxalate concentration. The precision was <14.70% and the accuracy was <19.73%. An advantage of the method is a shorter run time vs. other chromatography-based methods (<4 min) and better sensitivity than most reported methods to date.

Gómez et al. reported using ion chromatography with an Orbitrap mass spectrometer and electrospray ionization to quantify oxalic acid in bees, honey, beeswax, and bee bread (fermented bee pollen) [35]. The limit of detection was 0.011 µmol/kg of the sample, within-run precision was 20% relative standard deviation, and recovery was from 67% to 82%, with the lowest recovery from beeswax and highest recovery from whole bees. One potential limitation was the sample preparation time, which included disruption with an ultrasonic probe, lipid removal with a C18 cartridge, and deproteinization with acetonitrile. However, given the complexity of the matrices, all steps are likely necessary to avoid strong matrix effects. Indeed, a strength of the method was less than 10% signal suppression from matrices. In addition, the sensitivity was comparable to that of electrochemical methods, and the specificity of modern mass spectrometry is superior.

2.3. Gas-Chromatography-Based Methods

A GC-MS method was also reported in 1987 for determining urinary oxalate with 13C-oxalate as an internal standard [36]. This protocol required a 3 h precipitation step for oxalate with calcium, and derivatization to its isopropyl ester with propane-2-ol-HCl, and the limits of detection and quantification were not directly assessed. However, linearity was shown from 25 µL to 100 µL of 1.0 mM oxalate after drying, derivatization, and chloroform extraction.

In 1988, plasma oxalate was measured by capillary GC with flame ionization detection, and compared with GC-MS, using 13C-oxalate as an internal standard in the latter method [37]. In this protocol, oxalate was extracted with ethyl acetate and derivatized with MTBSTFA for 24 h. A limitation of the method, other than the reaction time, was a 57.9% oxalate recovery. Although a limit of detection was not reported, oxalate was quantified as low as 1.5 µM in plasma. This reported sensitivity is not typically achieved with most other methods discussed in this review. Lastly, the correlation coefficient between flame ionization detection and mass spectrometry was 0.938.

A recent report (2020) demonstrated that gas chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry could be instrumental in measuring the oxalate synthesis rate in human subjects with or without primary hyperoxaluria (liver-generated oxalate) [38]. In this method, 13C-labeled oxalate and glycolate were continuously infused into human subjects to monitor tracer-to-tracee ratios (TTRs). Plasma samples were derivatized with MTBSTFA prior to GC-MS/MS analysis. The proposed major utility of the method is in measuring the efficacy of therapeutic interventions for preventing oxalate synthesis. The method was not designed to measure absolute oxalate concentrations, but rather tracer/tracee ratios. Therefore, limit of detection and quantification were not reported. However, the TTR calibration curve was linear with an R2 of 0.9999.

2.4. Electrochemical Non-Enzymatic Methods

In 2000, the oxalate content of various foods was quantified using anion exchange chromatography coupled with a conductivity measurement [16]. This method was compared with capillary electrophoresis (discussed in the next section). The anion exchange method exhibited very high sensitivity (limit of quantification of 5.68 pM) compared to other reported methods. The response was linear and oxalate recovery was complete when mechanically processed food was heated with acid. A limitation was column “poisoning”, a term used to describe contamination of the column with food substances and diminished resolution with repeated use.

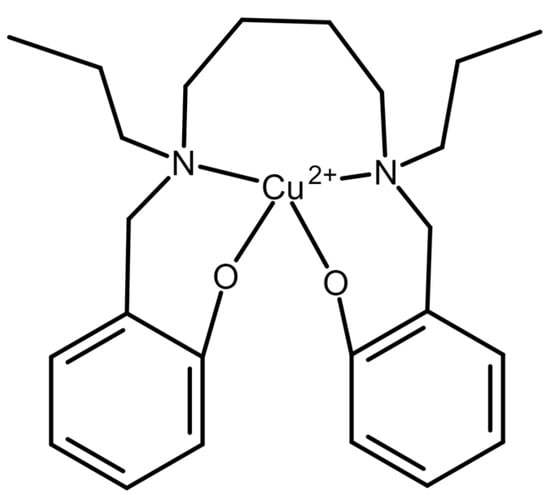

In 2006, an oxalate-selective membrane electrode based on polyvinyl chloride and the complex and ionophore, 2,2′-[1,4-butandiyle bis(nitrilo propylidine)]bis-1-naphtholato copper(II) (Figure 4), was used to quantify oxalate in water [39]. The limit of detection was 0.05 µM (4.4 × 10−3 µg/mL), and the linear range was 0.05 µM to 1.0 × 105 µM. Noted advantages, other than the sensitivity and dynamic range, were the fast response time of 10–15 s, and the ability to use the same electrode for 3 months. In addition, the electrode was several orders of magnitude more selective for oxalate than other anions, except for perchlorate and OH− (when tested in alkaline conditions). However, the utility of the method in a more complex sample matrix, such as urine or plasma, is unknown. If refined to maximize selectivity and proven to be suitable in complex fluids, this method could potentially be preferred due to its minimal need for sample handling or complex equipment.

Figure 4.

Ionophore used in [39] The ionophore, 2,2-[1,4-butandiyle bis(nitrilo propylidine)]bis-1-naphtholato copper(II) was used in a PVC-based ion-selective electrode for detection of oxalate.

In 2009, a method for the sensitive and selective detection of oxalate in aerosols using microchip electrophoresis was reported [40]. In this study, the investigators used micellar electrokinetic chromatography (MEKC), which takes advantage of the ability of surfactant micelles to modify separations of weakly solvated anions. Using this approach, oxalate, being a highly solvated anion, was readily separated from the micelle-influenced analytes. In addition, picolinic acid was used in order to chelate metals that would otherwise bind and reduce the detector response to oxalate. Detection was achieved with a Dionex conductivity detector, and the limit of detection for oxalate was 180 nM (1.67 × 10−3 µg/mL), with a 19 nM limit when field-amplified sample stacking was used. This sensitivity is a major advantage of the method, exceeding that of a large majority of other methods reported to date. In addition, a major advantage of this method is the ability for the continuous online monitoring of the aerosol composition due to the sample run times of less than 1 min. Disadvantages of this method include a loss of response linearity above 300 µM, poor resolution between oxalate and the internal standard at higher concentrations, and a change in bulk solution conductivity with higher analyte concentrations. The latter limitation needs to be corrected by internal standard addition. Finally, this method has not been tested in biological samples, such as urine or plasma.

In 2022, Moura et al. used ion chromatography with a conductivity detector to quantify oxalate and other anions (and cations) in C. elegans [41]. Worms were digested with 35% H2O2 and microwave radiation, then dried, resuspended in water, and filtered. The filtrate was used directly for analysis. Separation was performed on a DIONEX IonPac AS19 analytical column with AG19 guard column. A gradient elution was used with a KOH gradient with a suppression system. A dual-channel conductivity detector was used, one channel for anions, the other for cations. The method showed linearity from 1.0 to 100 µg/L (r2 = 0.9999), with a limit of detection of 0.273 µg/L and a limit of quantitation of 0.827 µg/L.

In 2023, Kotani et al. used semi-micro hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography coupled with electrochemical detection (HILIC-ECD) to quantify oxalate in herbal products used in traditional Kampo medicine [42]. Kampo is the study of traditional Chinese medicine in Japan. Herbal products evaluated in this study included Zingiberis Rhizoma Processum, Pinelliae Tuber, Sho-seiryu-to, Hange-shashin-to, Kami-shoyo-san, Bakumondo-to, and Daikenchu-to. Preparation of samples involved heating in a 10% w/v HCl solution at 90 °C, centrifugation, dilution of supernatant in 10% w/v HCl, then dilution in acetonitrile/phosphate buffer prior to filtration through a PTFE filter. An Intersil Amide column (250 × 1.0 mm i.d., 3 µm) was used for separation at 50 °C, and detection was at an applied potential of +1.1 V vs. Ag/AgCl. This method demonstrated a broad linear range, from 4.5 × 10−4 to 1.8 µg/mL (0.0019 µM limit of detection), making it one of the most sensitive methods reported to date. A limitation was that the oxalic acid peak appeared to approach the limit of detection in Sho-seiryu-to extracts.

2.5. Indicator-Displacement-Based UV, Colorimetric, and Fluorescence Methods

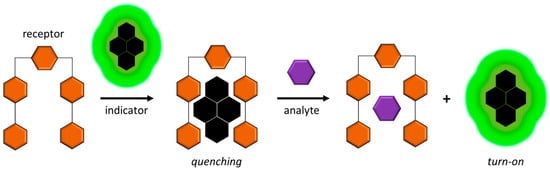

There is substantial interest in developing indicator-displacement-based methods for detecting oxalate that do not require enzymes, liquid chromatography, or mass spectrometry. Many of these methods quantify fluorescence quenching, or, more often, gain of fluorescence upon addition of the analyte [54]. The principle of operation is shown in Figure 5. A capillary electrophoresis method coupled with indicator displacement and UV absorbance [16] and a colorimetric method [49] have also been reported. These approaches are briefly discussed here.

Figure 5.

Principle of operation of indicator-displacement-based fluorescent chemosensors. The receptor (e.g., macrocyclic metal complex) sequesters the indicator, inhibiting fluorescence. The analyte of interest is added to displace the indicator, regaining fluorescence.

In 2000, the oxalate content of foods was estimated via capillary electrophoresis coupled with the UV absorbance (254 nm) response to oxalate-mediated chromate displacement [16]. The reported limit of quantification was 5.68 pM, which is the greatest sensitivity that we have found reported to date. Limitations included the need for adjustment of the electrolyte concentration for samples with low oxalate concentrations, and heating samples for 1 h. There is also a potential for oxalate to co-elute with interfering compounds, but this limitation was not observed in the study.

In 2018, a colorimetric method was developed wherein oxalate inhibited the reaction of curcumin nanoparticles with Fe (III) in acidic media [49]. The absorbance of 427 nm light by the nanoparticles showed a linear increase proportional to the oxalate concentration from 0.15 to 1.70 µg/mL. The limit of detection was 0.87 µM (0.077 µg/mL). The method was demonstrated to work well for the quantification of oxalate in water, food, and urine samples. Advantages of the method include simplicity and sensitivity. A potential limitation is interference from other substances, which was demonstrated for copper and carbonate/bicarbonate, and was not assessed for other common anions in urine, such as citrate and urate. Indeed, all indicator displacement methods are limited by either known interferences, or untested putative interferences.

A recent report by Hontz et al. revisited a fluorescence-based indicator displacement method, clearly demonstrating that interference from untested compounds in biological samples may be more prevalent than is sometimes suggested [54]. Specifically, it was shown that a dinuclear copper(II)-based macrocycle with the ability to quench eosin Y fluorescence, although reported as oxalate-selective, exhibited a stronger response to citrate and oxaloacetate. Other copper-based oxalate sensors, also based on reversing quenching, have been reported [55,56]. The reported sensitivities of these methods are in the low µM range; however, we have found that all studies to date have not performed a comprehensive assessment of potentially interfering compounds. For example, Rhaman et al. reported a nickel-based macrocycle that bound to oxalate in water [57]. Oxalate binding to the macrocycle triggered a red shift in eosin Y fluorescence with a corresponding visible color change. Potential interfering ions tested in this study included F–, Cl–, Br–, I–, NO3–, ClO4–, SO42–, and PO43–. Although none of the ions demonstrated interference, organic anions (e.g., citrate, urate, or oxaloacetate), were not tested. In contrast to reversing fluorescence quenching, at least one investigation reported the reversal of a fluorescence “turn on” response [58]. Specifically, Tang et al. showed that Zn2+ could turn on the fluorescence of a binaphthol-quinolone Schiff base. This gain in fluorescence could then be reversed via oxalate-mediated chelation and displacement of the zinc ion. In this study, phthalate, isophthalate, terephthalate, succinate, glutarate, adipate, and malonate showed no significant interference with the assay when tested at an equimolar concentration to oxalate; however, other anions were not tested, and it remains unknown whether high concentrations of the tested anions would interfere.

In 2020, Chen et al. reported the detection of oxalate via a selective recognition reaction using cadmium telluride (CdTe) quantum dots [51]. In this approach, the reduction of Cu2+ to Cu+ by oxalate was measured by quantifying the change in the fluorescence intensity of CdTe quantum dots using an excitation wavelength of 365 nm, and an emission wavelength range of 570 to 720 nm. Cu+ was able to quench the fluorescence of the CdTe quantum dots much more effectively than Cu2+. Therefore, as the concentration of oxalate increased, fluorescence decreased proportionately. This method was successfully employed with clinical urine samples, even in the presence of hematuria (presence of blood). In this study, the specificity of the assay for oxalate was measured by comparing against NaCl, KCl, MgCl2, Na2HPO4, NaH2PO4, urea, and glucose. No interference was observed; however, organic anions (e.g., citrate) were not assessed for interference. With optimization, the investigators achieved a linear response to oxalate from 100 nM to 10 mM in urine, with a limit of detection of 80 nM. Recovery of added oxalate was 96 to 105%. The method was able to differentiate between uric acid nephrolithiasis and calcium oxalate nephrolithiasis in clinical samples. When tested against an LC-MS method, the CdTe-based method gave similar results; however, repeatability was not assessed, and a correlation coefficient was not calculated. A more recent advancement was reported by Chen et al. using CdTe quantum dots, wherein printed test strips were able to detect oxalate ranging from 10 pM to 10 nM within 3 min [59].

More recently (2023), Wu et al. reported using Fe(III)-sulfosalicylate as a colorimetric chemosensor of oxalic acid in model wastewater undergoing photocatalytic ozonation [53]. In this method, oxalic acid stoichiometrically removes Fe(III) from Fe(III)-sulfosuccinate, producing a colorless product measured by spectrophotometry. The linear range of the assay was 0.80–160 mg/L (r2 = 0.9993), with a limit of detection of 0.74 mg/L. Results of the assay were comparable to those of an HPLC method. The sensor was synthesized using a simple process involving mixing an aqueous solution of FeCl3 with a solution of 5-sulfosalicylate, and diluting with a 0.01 M HCl solution (final pH of 1.9). Oxalic acid in model wastewater mixed with P25 TiO2 and simulated sunlight (AM1.5) was used with continuous ozone bubbling. To quantify oxalic acid, the catalyst was removed, the solution was mixed with the sensor solution, then the absorbance at 505 nm was measured using a standard UV-Vis spectrophotometer. A limitation identified in the study was significant interference from other dicarboxylic acids, such as methylmalonic acid, malonic acid, and succinic acid. Moreover, the assay was tested only in model wastewater.

Several additional colorimetric or fluorescent indicator-based methods have been reported, generally with lower sensitivity than electrochemical or mass-spectrometry-based methods [43,44,45,46,47,48,50,52]. All of these methods have the advantage of simple sample preparation, but invariably, they have either not been tested for interference from other organic anions, or interference has clearly been demonstrated. Given the proliferation of such studies from 2000 to 2023, there is a palpable need to improve data interpretation and extrapolation to avoid false conclusions of high specificity.

2.6. Summary of Analytical Methods for Quantifying Oxalate

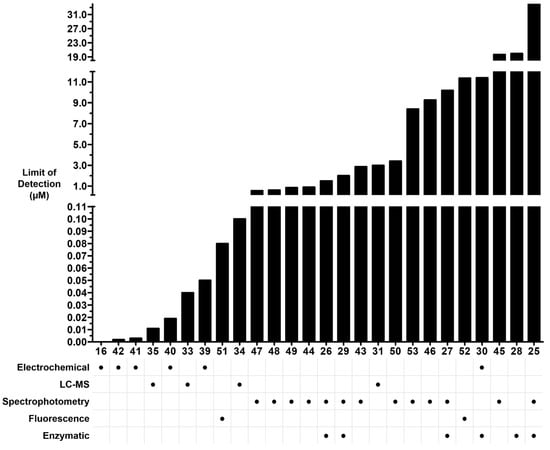

In summary, recent studies using LC-MS/MS-based methods have demonstrated a potential for high sensitivity in detecting oxalate (Figure 6). Although the sensitivity of GC-MS can theoretically be superior to several other methods, this has not been realized to date for oxalate. Moreover, the requisite derivatization step to volatilize oxalate makes sample preparation more time-consuming for GC-MS. Electrochemical methods have shown the greatest sensitivity, but LC-MS/MS is nearly eclipsing such approaches (Figure 6). Limitations of electrochemical detection include interference from variation in bulk solution conductivity, column fouling, and poor resolution for methods using column- or capillary-based modes of separation. Non-enzymatic fluorescent or colorimetric indicator methods have realized a high sensitivity and relative simplicity of instrumentation and reagents. A major limitation to these methods is the lack of specificity, or untested specificity, against common organic anions in the matrices tested.

Figure 6.

Limit of detection (LOD) of oxalate vs. mode of detection. Bars are broken for visibility of lower LOD. Numbers on horizontal axis represent reference numbers. LOD for reference 16 was reported at 0.2 mg/100 g in food, but linearity in final solution started at 5.68 × 10−6.

3. Conclusions and Future Perspective

While oxalate plays a crucial role in various biological and industrial applications, it can be a burden for a considerable portion of the population. Its involvement in diseases, drug- and toxin-induced disorders, and disruption of industrial processes makes it a high-priority chemical for the development of more precise, selective, and straightforward analytical methods. Enzyme-based colorimetric methods have been a mainstay in oxalate analysis for many years, but the relatively low sensitivity, high cost, and significant time investment in sample preparation warranted the development of alternative methods.

Currently, there are no universally applicable, or superior, methods. Advances in mass spectrometry, coupled with improvements in orthologous separation methods for oxalate, has led to a more desirable sensitivity and specificity. The future utility of alternative methods depends on whether improvements in specificity are achieved, specifically for indicator-based methods. We propose that our review may serve as a valuable guide for researchers to select the most suitable methodology based on their objectives and instrumental context.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.M. and A.L.V.; investigation, B.M. and A.L.V.; writing—original draft preparation, B.M. and A.L.V.; writing—review and editing, B.M., D.M., A.L.V. and W.T.; visualization, A.L.V.; supervision, A.L.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No original data reported.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Khan, S.R.; Canales, B.K.; Dominguez-Gutierrez, P.R. Randall’s plaque and calcium oxalate stone formation: Role for immunity and inflammation. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2021, 17, 417–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Patel, M.; Oster, R.A.; Yarlagadda, V.; Ambrosetti, A.; Assimos, D.G.; Mitchell, T. Dietary Oxalate Loading Impacts Monocyte Metabolism and Inflammatory Signaling in Humans. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 617508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Statistics Report Website. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/data/statistics-report/index.html (accessed on 3 April 2023).

- Huang, Y.; Zhang, Y.H.; Chi, Z.P.; Huang, R.; Huang, H.; Liu, G.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, H.; Lin, J.; Yang, T.; et al. The Handling of Oxalate in the Body and the Origin of Oxalate in Calcium Oxalate Stones. Urol. Int. 2020, 104, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiela, P.R.; Ghishan, F.K. Physiology of Intestinal Absorption and Secretion. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2016, 30, 145–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakhaee, K. Recent advances in the pathophysiology of nephrolithiasis. Kidney Int. 2009, 75, 585–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, K.W.; Letson, R.; Scheinman, J. Ocular findings in primary hyperoxaluria. Arch. Ophthalmol. 1990, 108, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Wang, W.; Wang, H.; Tuo, B. Physiological and Pathological Functions of SLC26A6. Front. Med. 2021, 7, 618256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lieske, J.C.; Mehta, R.A.; Milliner, D.S.; Rule, A.D.; Bergstralh, E.J.; Sarr, M.G. Kidney stones are common after bariatric surgery. Kidney Int. 2015, 87, 839–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatch, M.; Freel, R.W. Angiotensin II involvement in adaptive enteric oxalate excretion in rats with chronic renal failure induced by hyperoxaluria. Urol. Res. 2003, 31, 426–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W. Effect of Oxaliplatin on Voltage-Gated Sodium Channels in Peripheral Neuropathic Pain. Processes 2020, 8, 680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grolleau, F.; Gamelin, L.; Boisdron-Celle, M.; Lapied, B.; Pelhate, M.; Gamelin, E. A Possible Explanation for a Neurotoxic Effect of the Anticancer Agent Oxaliplatin on Neuronal Voltage-Gated Sodium Channels. J. Neurophysiol. 2001, 85, 2293–2297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Office of Dietary Supplements. Vitamin C. Available online: https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/VitaminC-HealthProfessional/ (accessed on 26 April 2022).

- Knight, J.; Madduma-Liyanage, K.; Mobley, J.A.; Assimos, D.G.; Holmes, R.P. Ascorbic acid intake and oxalate synthesis. Urolithiasis 2016, 44, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, L.D.K.; Elinder, C.-G.; Tiselius, H.-G.; Wolk, A.; Akesson, A. Ascorbic acid supplements and kidney stone incidence among men: A prospective study. JAMA Intern. Med. 2013, 173, 386–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, R.P.; Kennedy, M. Estimation of the oxalate content of foods and daily oxalate intake. Kidney Int. 2000, 57, 1662–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franceschi, V.R.; Nakata, P.A. Calcium Oxalate in Plants: Formation and Function*. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2005, 56, 41–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, A.G. Research Advances: Floating Metals; Oxalate Fights Phytotoxin; A Taste of Success in the Search for an Electronic Tongue. J. Chem. Educ. 2006, 83, 1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutton, M.V.; Evans, C.S. Oxalate production by fungi: Its role in pathogenicity and ecology in the soil environment. Can. J. Microbiol. 1996, 42, 881–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheta, H.M.; Al-Najami, I.; Christensen, H.D.; Madsen, J.S. Rapid Diagnosis of Ethylene Glycol Poisoning by Urine Microscopy. Am. J. Case Rep. 2018, 19, 689–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oxalic Acid: The Magic of Bar Keepers Friend-Bar Keepers Friend n.d. Available online: https://www.barkeepersfriend.com/oxalic-acid-magic-of-bkf/ (accessed on 26 April 2022).

- Weerasinghe Mohottige, T.N.; Kaksonen, A.H.; Cheng, K.Y.; Sarukkalige, R.; Ginige, M.P. Kinetics of oxalate degradation in aerated packed-bed biofilm reactors under nitrogen supplemented and deficient conditions. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 211, 270–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassland, P.; Sjöde, A.; Winestrand, S.; Jönsson, L.J.; Nilvebrant, N.-O. Evaluation of Oxalate Decarboxylase and Oxalate Oxidase for Industrial Applications. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2010, 161, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Castro, M.D. Determination of oxalic acid in urine: A review. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 1988, 6, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansen, E.H.; Winther, S.K.; Gundstrup, M. Enzymatic Assay of Oxalate in Urine by Flow Injection Analysis Using Immobilized Oxalate Oxidase and Chemiluminescence Detection. Anal. Lett. 1994, 27, 1239–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hönow, R.; Bongartz, D.; Hesse, A. An improved HPLC-enzyme-reactor method for the determination of oxalic acid in complex matrices. Clin. Chim. Acta 1997, 261, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, L.; Thakur, M.; Pundir, C.S. Quantification of Urinary Oxalate with Alkylamine Glass Bound Amaranthus Leaf Oxalate Oxidase. Anal. Lett. 1999, 32, 633–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, F.; Nilvebrant, N.-O.; Jönsson, L.J. Rapid and convenient determination of oxalic acid employing a novel oxalate biosensor based on oxalate oxidase and SIRE technology. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2003, 18, 1173–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, G.; Jiang, X.; Liu, H.; Zhang, J. A novel urinary oxalate determination method via a catalase model compound with oxalate oxidase. Anal. Methods 2010, 2, 254–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, J.A.; Hernandez, P.; Salazar, V.; Castrillejo, Y.; Barrado, E. Amperometric Biosensor for Oxalate Determination in Urine Using Sequential Injection Analysis. Molecules 2012, 17, 8859–8871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keevil, B.G.; Thornton, S. Quantification of Urinary Oxalate by Liquid Chromatography–Tandem Mass Spectrometry with Online Weak Anion Exchange Chromatography. Clin. Chem. 2006, 52, 2296–2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, D.J.; Adaway, J.E.; Keevil, B.G. A combined liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry assay for the quantification of urinary oxalate and citrate in patients with nephrolithiasis. Ann. Clin. Biochem. 2018, 55, 461–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, Y.; Wu, Y.; Wang, X.; Hu, L.; Ke, R. Determination of 10 organic acids in alcoholic products by ion chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Se Pu Chin. J. Chromatogr. 2022, 40, 1128–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Zheng, J.; Chen, M.; Liu, B.; Liu, Z.; Gong, L. Simultaneous determination of oxalate and citrate in urine and serum of calcium oxalate kidney stone rats by IP-RP LC-MS/MS. J. Chromatogr. B Anal. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 2022, 1208, 123395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez, I.B.; Ramos, M.J.G.; Rajski, Ł.; Flores, J.M.; Jesús, F.; Fernández-Alba, A.R. Ion chromatography coupled to Q-Orbitrap for the analysis of formic and oxalic acid in beehive matrices: A field study. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2022, 414, 2419–2430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koolstra, W.; Wolthers, B.G.; Hayer, M.; Elzinga, H. Development of a reference method for determining urinary oxalate by means of isotope dilution—Mass spectrometry (ID-MS) and its usefulness in testing existing assays for urinary oxalate. Clin. Chim. Acta 1987, 170, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- France, N.C.; Holland, P.T.; McGhie, T.K.; Wallace, M.R. Measurement of plasma oxalate by capillary gas chromatography and its validation by isotope dilution mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. B: Biomed. Sci. Appl. 1988, 433, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Harskamp, D.; Garrelfs, S.F.; Oosterveld, M.J.S.; Groothoff, J.W.; van Goudoever, J.B.; Schierbeek, H. Development and Validation of a New Gas Chromatography–Tandem Mass Spectrometry Method for the Measurement of Enrichment of Glyoxylate Metabolism Analytes in Hyperoxaluria Patients Using a Stable Isotope Procedure. Anal. Chem. 2020, 92, 1826–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ardakani, M.M.; Jalayer, M.; Naeimi, H.; Heidarnezhad, A.; Zare, H.R. Highly selective oxalate-membrane electrode based on 2,2′-[1,4-butandiyle bis(nitrilo propylidine)]bis-1-naphtholato copper(II). Biosens. Bioelectron. 2006, 21, 1156–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noblitt, S.D.; Schwandner, F.M.; Hering, S.V.; Collett, J.L.; Henry, C.S. High-sensitivity microchip electrophoresis determination of inorganic anions and oxalate in atmospheric aerosols with adjustable selectivity and conductivity detection. J. Chromatogr. A 2009, 1216, 1503–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moura, A.V.; Silva, A.A.R.; da Silva, J.D.S.; Pedroza, L.A.L.; Bornhorst, J.; Stiboller, M.; Schwerdtle, T.; Gubert, P. Determination of ions in Caenorhabditis elegans by ion chromatography. J. Chromatogr. B Anal. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 2022, 1204, 123312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotani, A.; Ishikawa, H.; Shii, T.; Kuroda, M.; Mimaki, Y.; Machida, K.; Yamamoto, K.; Hakamata, H. Determination of oxalic acid in herbal medicines by semi-micro hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography coupled with electrochemical detection. Anal. Sci. 2023, 39, 441–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Q.-Z.; Zhang, X.-X.; Liu, Q.-Z. Catalytic kinetic spectrophotometry for the determination of trace amount of oxalic acid in biological samples with oxalic acid-rhodamine B-potassium dichromate system. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2006, 65, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamjangali, M.A.; Keley, V.; Bagherian, G. Kinetic Spectrophotometric Method for the Determination of Trace Amounts of Oxalate by an Activation Effect. Anal. Sci. 2006, 22, 333–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Q.-Z.; Zhang, X.-X.; Liu, Q.-Z. Spectrophotometric determination of trace oxalic acid with zirconium(IV)-dibromochloroarsenazo complex. Bull. Chem. Soc. Ethiop. 2007, 21, 297–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Q.-Z. Determination of trace amount of oxalic acid with zirconium(IV)-(DBS-arsenazo) by spectrophotometry. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2008, 71, 332–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arab Chamjangali, M.; Sharif-Razavian, L.; Yousefi, M.; Amin, A.H. Determination of trace amounts of oxalate in vegetable and water samples using a new kinetic-catalytic reaction system. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2009, 73, 112–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavallali, H.; Deilamy-Rad, G.; Mosallanejad, N. Development of a New Colorimetric Chemosensor for Selective Determination of Urinary and Vegetable Oxalate Concentration Through an Indicator Displacement Assay (IDA) in Aqueous Media. Food Technol. Biotechnol. 2018, 56, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pourreza, N.; Lotfizadeh, N.; Golmohammadi, H. Colorimetric sensing of oxalate based on its inhibitory effect on the reaction of Fe (III) with curcumin nanoparticles. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2018, 192, 251–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, D.P.; Pinto, G.F.; Silva, S.M.; Squissato, A.L.; Silva, S.G. A multi-pumping flow system for spectrophotometric determination of oxalate in tea. Microchem. J. 2020, 157, 104938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Bai, Y.; Tang, Y.; Yan, S.; Wang, X.; Wei, W.; Wang, J.; Zhang, M.; Ying, B.; Geng, J. Rapid and highly sensitive visual detection of oxalate for metabolic assessment of urolithiasis via selective recognition reaction of CdTe quantum dots. J. Mater. Chem. B 2020, 8, 7677–7684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, H.; Li, X.; Li, Y.; Feng, S. Wild jujube-based fluorescent carbon dots for highly sensitive determination of oxalic acid. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 28545–28552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Li, F.; Yu, H.; Shen, L.; Wang, M. Facile and rapid determination of oxalic acid by fading spectrophotometry based on Fe(III)-sulfosalicylate as colorimetric chemosensor. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2023, 284, 121784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hontz, D.; Hensley, J.; Hiryak, K.; Lee, J.; Luchetta, J.; Torsiello, M.; Venditto, M.; Lucent, D.; Terzaghi, W.; Mencer, D.; et al. A Copper(II) Macrocycle Complex for Sensing Biologically Relevant Organic Anions in a Competitive Fluorescence Assay: Oxalate Sensor or Urate Sensor? ACS Omega 2020, 5, 19469–19477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Park, J.; Kim, H.-J.; Kim, Y.; Kim, S.J.; Chin, J.; Kim, K.M. Tight Binding and Fluorescent Sensing of Oxalate in Water. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 12606–12607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emami, E.; Mousazadeh, M.H. Green synthesis of carbon dots for ultrasensitive detection of Cu2+ and oxalate with turn on-off-on pattern in aqueous medium and its application in cellular imaging. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2021, 418, 113443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhaman, M.M.; Fronczek, F.R.; Powell, D.R.; Hossain, M.A. Colourimetric and fluorescent detection of oxalate in water by a new macrocycle-based dinuclear nickel complex: A remarkable red shift of the fluorescence band. Dalton Trans. 2014, 43, 4618–4621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, L.; Wu, D.; Huang, Z.; Bian, Y. A fluorescent sensor based on binaphthol-quinoline Schiff base for relay recognition of Zn2+ and oxalate in aqueous media. J. Chem. Sci. 2016, 128, 1337–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Cen, L.; Wang, Y.; Bai, Y.; Shi, T.; Chen, X. Rapid binary visual detection of oxalate in urine samples of urolithiasis patients via competitive recognition and distance reading test strips. J. Mater. Chem. B 2023, 11, 2530–2537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).