Research Progress on Natural Plant Molecules in Regulating the Blood–Brain Barrier in Alzheimer’s Disease

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Structure and Function of the Blood–Brain Barrier

2.1. Endothelial Cell

2.2. Astrocytes

2.3. Pericyte

2.4. Basement Membrane

3. The Relationship between the Blood–Brain Barrier and AD Pathology

4. The Specific Mechanism of BBB Affecting AD Progression

4.1. Endothelial Cells and Tight Junction Damage

4.2. Changes in Astrocyte Function and Structure

4.3. Pericyte Degradation

4.4. Basement Membrane Thickening and Extracellular Matrix Protein Disorders

5. The Related Pathways of Natural Plant Molecules Regulating the AD Blood–Brain Barrier

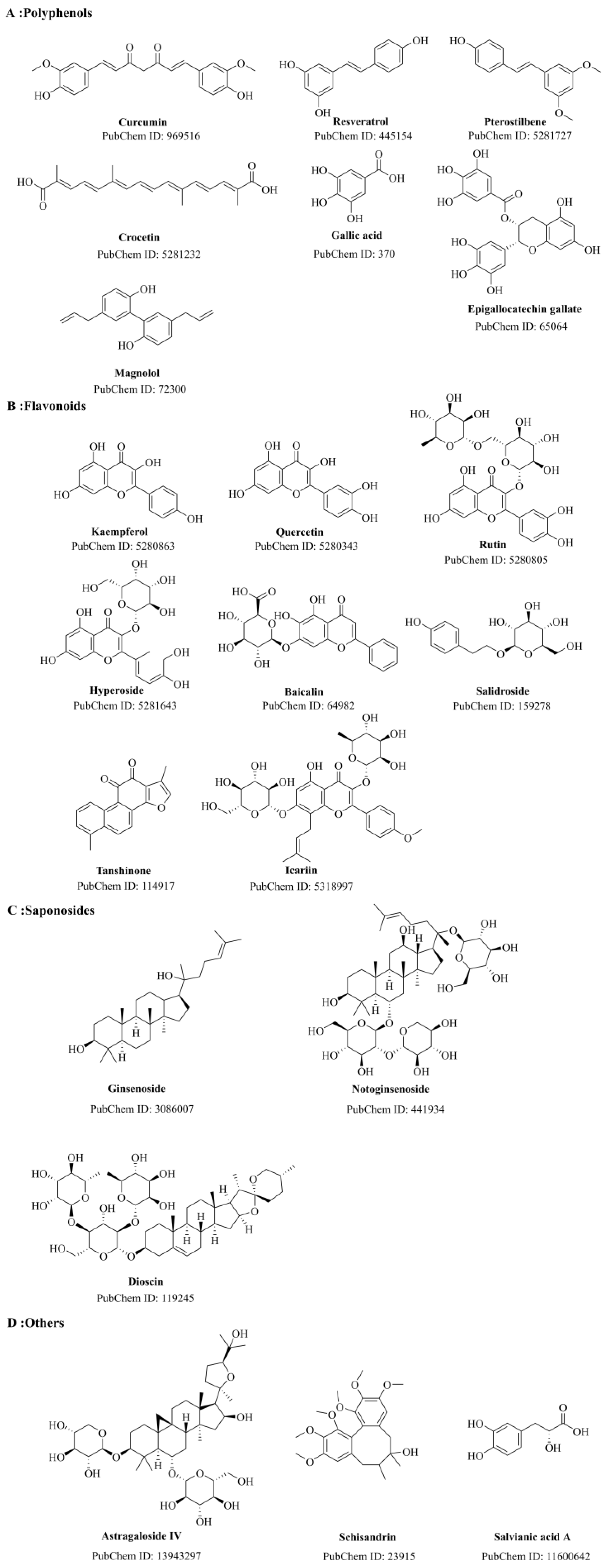

5.1. Polyphenols (Table 1)

5.1.1. Curcumin

5.1.2. Resveratrol

5.1.3. Pterostilbene

5.1.4. Crocetin

5.1.5. Gallic Acid

5.1.6. Epigallocatechin Gallate

5.1.7. Magnolol

| Natural Plant Molecules | Experimental Subjects | Possible Mechanisms | Target of Action | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Curcumin | APP/PS1 mouse | Regulating PPARγ activity ↓ NF-κB signaling pathway | Astrocytes and endothelial cells | Liu 2016 [130] |

| Resveratrol | AD patients | ↓MMP9 | Endothelial cells | Moussa 2017 [135] |

| OVX+D-gal rat | ↓ NF-κB signaling pathway ↑ Claudin-5 ↓ RAGE, MMP-9 | Astrocytes and endothelial cells | Zhao 2015 [136] | |

| APP/PS1 mouse | ↑ LRP1 protein expression | Endothelial cells | Santos 2016 [138] | |

| Pterostilbene | The immortalized murine microglia cell line BV-2 | ↓ NLRP3/caspase-1 inflammasome pathway | Astrocytes and microglia | Li 2018 [144] |

| APP/PS1 mouse | ↑ PDE4A-CREB-BDNF pathway | Endothelial cells and astrocytes | Meng 2019 [145] | |

| Aβ1-42 induced mice | ↑ Nrf2 signaling pathway | Endothelial cells and microglia | Xu 2021 [146] | |

| Crocetin | AD model of 5XFAD mice | ↑ Autophagy via regulating AMPK pathway | Endothelial cells and microglia | Wani 2021 [150] |

| LPC-treated primary mixed mesencephalic neuron/glial cultures | ↓ Microglia activation | Microglia | Zang 2022 [151] | |

| APP/PS1 mouse | ↓ NF-κB activation ↓ P53 expression | Astrocytes and microglia | Zhang 2018 [152] | |

| Mouse hippocampal Ht22 cells | ↑ Antioxidant capacity | Endothelial cells, astrocytes, and microglia | Kong 2014 [153] | |

| Gallic acid | APP/PS1 mouse | ↑ ADAM10 ↓ BACE1 activity | Endothelial cells and microglia | Mori 2020 [156] |

| APP/PS1 mouse | ↓ Aβ aggregation ↑ synaptic strength ↓ inflammation ↓ intracellular calcium influx | Endothelial cells and microglia | Yu 2019 [158] | |

| Epigallocatechin gallate | BV2 cells and APP/PS1 mice | ↓ TLR4/NF-κB pathway | Endothelial cells and microglia | Zhong 2019 [161] |

| Aβ25-35 induced AD rat | ↓ Hyperphosphorylation of tau protein ↓ BACE1 and Aβ1-42 expression | Endothelial cells and microglia | Nan 2021 [162] | |

| APP/PS1 mouse | ↓ ROS production ↓ Aβ aggregation | Endothelial cells and microglia | Chen 2020 [163] | |

| Magnolol | APP/PS1 mouse | ↑ Autophagy via regulating AMPK/mTOR/ULK1 pathway | Endothelial cells and microglia | Wang 2023 [166] |

| TgCRND8 mice | Regulating PI3K/Akt/GSK-3β and NF-κB pathway | Microglia and astrocytes | Xian 2020 [167] | |

| Transgenic caenorhabditis elegans | Regulating PPAR-γ activity ↓ NF-κB and inflammatory cytokines ↓ ROS via Nrf2-ARE | Endothelial cells and microglia | Xie 2020 [168] | |

| Aβ-induced SH-SY1Y cells | Regulating the cAMP/PKA/CREB pathway | Endothelial cells and microglia | Zhu 2022 [169] |

5.2. Flavonoids (Table 2)

5.2.1. Kaempferol

5.2.2. Quercetin

5.2.3. Rutin

5.2.4. Hyperoside

5.2.5. Baicalin

5.2.6. Salidroside

5.2.7. Tanshinone

5.2.8. Icariin

| Natural Plant Molecules | Experimental Subjects | Possible Mechanisms | Target of Action | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kaempferol | Aβ1-42-induced mice | ↓ Oxidative stress ↑ BDNF/TrkB/CREB | Endothelial cells and microglia | Yan 2019 [174] |

| STZ-induced AD rats | ↑ SOD and GSH ↓ MDA | Endothelial cells and microglia | Babaei 2021 [175] | |

| STZ-induced AD rats | ↑ SOD and GSH ↓ MDA and TNF-α | Endothelial cells and microglia | Kouhestani 2018 [176] | |

| LPS-induced mice | ↓ Neuroinflammation ↑ BBB integrity ↓ HMGB1/TLR4 pathway | Endothelial cells and microglia | Yang 2019 [177] | |

| Quercetin | Aβ damages cerebral microvascular endothelial cells | ↓ Oxidative stress ↑ Transendothelial permeability regulating enzymes and maintaining BBB integrity | Endothelial cell | Li 2015 [180] |

| Hypoxia-injured endothelial cells | Regulating Keap1/Nrf2 pathway ↑BBB junction proteins Maintaining BBB integrity | Endothelial cell | Li 2021 [182] | |

| Rutin | Aβ-induced rat | Regulating BDNF and MAPK cascades | Astrocytes and microglia | Mogbelinejad 2014 [188] |

| Male Tau-P301S mice | Regulating PP2A, NF-kB pathway | Endothelial cells and microglia | Sun 2021 [189] | |

| APP/PS1 mouse | ↓ Oxidative stress ↓ Inflammatory response ↓ Aβ oligomer activity | Endothelial cells and microglia | Xu 2014 [190] | |

| Transgenic TgAPP mice | ↓ APP expression ↓ BACE1 activity | Endothelial cells and microglia | Bermejo-Bescós 2023 [191] | |

| Hyperoside | APP/PS1 mouse | ↓ BACE1, GSK3β | Endothelial cells and microglia | Chen 2021 [192] |

| Aβ-induced AD mice | Regulating synaptic calcium-permeable AMPA receptor | Endothelial cells | Yi 2022 [193] | |

| APP/PS1 mouse | ↓ Aβ aggregation ↓ BACE1 | Endothelial cells and astrocytes | Song 2023 [194] | |

| Baicalin | APP/PS1 mouse and BV2 cells | ↓ Activation of NLRP3 inflammasome ↓ TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway | Microglia and astrocytes | Jin 2019 [196] |

| Aβ1-42-induced mice | ↓ Neuroinflammation | Microglia and astrocytes | Chen 2015 [197] | |

| Aβ-induced BV2 microglia | Regulating JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway | Microglia | Xiong 2014 [198] | |

| Aβ induced SH-SY5Y cells | Regulating Ras-ERK signaling pathway | Microglia and astrocytes | Song 2022 [199] | |

| Aβ1-42 induced rat | Regulating Nrf2 pathway ↓ Oxidative stress | Endothelial cells and microglia | Ding 2015 [200] | |

| Aβ-induced AD mice | Regulating PDE-PKA-Drp1 signaling | Endothelial cells and microglia | Yu 2022 [201] | |

| Salidroside | D-gal induced mice | ↑ SIRT1 ↓ NF-κB pathway | Endothelial cells and astrocytes | Gao 2016 [203] |

| SAMP8 mice | ↓ Pro-inflammatory cytokines | Endothelial cells and astrocytes | Xie 2020 [204] | |

| Aβ1-42 induced mice and D-gal induced mice | ↓ NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated pyroptosis | Microglia and astrocytes | Cai 2021 [205] | |

| PC-2 cells | Regulating ERK1/2 and AKT signaling pathways | Microglia and astrocytes | Liao 2019 [206] | |

| APP/PS1 mouse | ↑ PSD95, NMDAR1 ↑ Calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II Regulating phosphatidylinositol PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling | Endothelial cells, microglia, and astrocytes | Wang 2020 [207] | |

| Aβ1-42-induced mice and Glu-damaged HT22 cells | Regulating Nrf2/HO1 signaling pathway | Endothelial cells and microglia | Yang 2022 [208] | |

| AD model of 5XFAD mice | Regulating Nrf2/SIRT3 signaling pathway | Endothelial cells and microglia | Yao 2022 [209] | |

| SAMP8 mice | ↑ Nrf2/GPX4 axis ↓ CD8+ T cell infiltration | Endothelial cells, microglia, and astrocytes | Yang 2023 [210] | |

| Tanshinone | APP/PS1 mouse | Regulating RAGE/NF-κB signaling pathway | Endothelial cells and microglia | Ding 2020 [211] |

| Aβ-induced AD mice | ↓ Neuroinflammatory factors | Astrocytes and microglia | Maione 2018 [212] | |

| Aβ1-42-induced mice | ↓ NF-κB ↑ NeuN, Nissl body, and IκB | Endothelial cells, astrocytes, and microglia | Li 2015 [213] | |

| Aβ1-42-induced rat | ↓ The activity of ERK and GSK-3β | Microglia and astrocytes | Lin 2019 [214] | |

| APP/PS1 mouse | ↑ PI3K/Akt pathway ↓ GSK-3β ↓ Tau hyperphosphorylation | Endothelial cells, microglia, and astrocytes | Peng 2022 [215] | |

| APP/PS1 mouse | ↑ The clearance of AD-related proteins ↑ BDNF-TrkB pathway | Endothelial cells and astrocytes | Li 2016 [216] | |

| APP/PS1 mouse | ↓ Aβ plaque deposition ↓ ER stress-induced apoptosis | Endothelial cells and microglia | He 2020 [217] | |

| APP/PS1 mouse | Regulating SIRT1 expression ↓ ER stress ↑ LRP1 ↓ RAGE | Endothelial cells and microglia | Wan 2023 [218] | |

| Icariin | APP/PS1 mouse | ↓ Pro-inflammatory cytokines ↑ PPARγ | Microglia and astrocytes | Wang 2019 [221] |

| Hippocampal neural stem cells treated with Aβ25-35 | Regulating BDNF-TrkB-ERK/Akt signaling pathway | Astrocytes and microglia | Lu 2020 [222] | |

| SAMP8 mice | ↓ BACE1 | Endothelial cells and microglia | Wu 2019 [223] | |

| Aβ1-42-induced rat | ↑ Autophagic lysosomal function | Astrocytes and microglia | Jiang 2019 [224] | |

| SAMP8 mice | Regulating autophagy | Astrocytes and microglia | Chen 2019 [225] |

5.3. Saponosides (Table 3)

5.3.1. Ginsenosides

5.3.2. Notoginsenosides

5.3.3. Dioscin

| Natural Plant Molecules | Experimental Subjects | Possible Mechanisms | Target of Action | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ginsenosides | AD tree shrews | Regulating Wnt/GSK-3β/β-catenin signaling pathway | Astrocytes and microglia | Yang 2022 [228] |

| D-gal induced rats | Regulating Nrf2-ARE pathway | Endothelial cells and microglia | Wang 2020 [229] | |

| Aβ-treated primary cultured rat hippocampal neurons | ↓ CDK5 induced PPARγ phosphorylation | Microglia and astrocytes | Quan 2020 [231] | |

| APP/PS1 mouse | ↑ NLRP1 inflammasome ↑ Autophagy function | Microglia and astrocytes | Li 2023 [232] | |

| Scopolamine-induced mice | Regulating cholinergic transmission ↓ Oxidative ↑ ERK-CREB-BDNF signaling pathway | Endothelial cells, microglia and astrocytes | Lv 2021 [233] | |

| APP/PS1 mouse | Regulating AMPK/Nrf2 signaling pathway | Endothelial cells and microglia | She 2023 [230] | |

| Notoginsenosides | Okada acid-treated AD brain slices | ↓ Tau protein phosphorylation ↑ BDNF | Endothelial cells and astrocytes | Wang 2013 [234] |

| Aβ-induced PC12 neuronal cells | ↓ MAPK signaling pathway | Astrocytes and microglia | Ma 2014 [236] | |

| Aβ-induced AD rats | ↓ BACE1 ↑ ADAM10, IDE | Endothelial cells and microglia | Liu 2019 [237] | |

| H2O2-treated primary rat cortical astrocytes | Regulating Nrf2 signaling pathway | Endothelial cells and microglia | Zhou 2014 [235] | |

| Dioscin | H2O2-treated SH-SY5Y cells and D-gal-induced C57BL/6J mice | Regulating the RAGE/NOX4 pathway | Endothelial cells and microglia | Guan 2022 [239] |

| Aβ1-42-treated HT22 cells | Regulating SIRT3 and autophagy | Astrocytes and microglia | Zhang 2020 [240] |

5.4. Others (Table 4)

5.4.1. Astragaloside IV

5.4.2. Schisandrin

5.4.3. Salvianic Acid A

| Natural Plant Molecules | Experimental Subjects | Possible Mechanisms | Target of Action | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Astragaloside IV | 5xFAD mouse and LPS-stimulated BV-2 cells | ↓ NF-κB signaling pathway | Astrocytes and microglia | He 2023 [243] |

| Aβ-induced AD mice | ↓ Microglial activation ↓NADPH oxidase protein expression | Endothelial cells and microglia | Chen 2021 [244] | |

| APP/PS1 mouse | ↑ PPARγ pathway ↓ BACE1 | Endothelial cells and Astrocytes | Wang 2017 [245] | |

| Aβ25-35-induced AD rat | Regulating PI3K/AKT and MAPK (or ERK) pathways | Microglia and astrocytes | Chang 2016 [246] | |

| Schisandrin | Aβ25-35–APP/PS1 mouse | ↓ NLRP1 | Microglia and astrocytes | Li 2021 [248] |

| Aβ-induced neuronal cells in rat brain | ↓ RAGE/NF-κB/MAPK ↑ HSP/Beclin | Endothelial cells, microglia, and astrocytes | Giridharan 2015 [249] | |

| Salvianic acid A | Aβ25-35-induced AD mice | ↓ Inflammation ↓ Oxidative stress | Endothelial cells and Astrocytes | Lee 2013 [251] |

| SH-SY5Y-APPsw cell | ↓ Oxidative stress ↓ GSK3β signal transduction | Endothelial cells and Astrocytes | Tang 2016 [252] | |

| N2a-mouse and H4-human neuroglioma cell lines expressing SwedAPP | ↓ BACE1 | Endothelial cells and microglia | Durairajan 2017 [253] |

6. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AD | Alzheimer’s disease |

| Aβ | Amyloid β-protein |

| NFT | Neurofibrillary tangle |

| BBB | Blood–brain barrier |

| NVU | Neurovascular unit |

| CNS | Central nervous system |

| BMECs | Brain microvascular endothelial cells |

| TJ | Tight junction |

| BDNF | Brain-derived neurotrophic factor |

| AQP4 | Aquaporin-4 |

| PDGF-BB | Platelet-derived growth factor-BB |

| BM | Basement membrane |

| ECM | Extracellular matrix |

| MAPK | Mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| BACE1 | β-amyloid precursor protein cleaving enzyme 1 |

| LRP-1 | Low-density lipoprotein-receptor-related protein 1 |

| RAGE | Receptor for advanced glycation endproducts |

| CAA | Cerebral amyloid angiopathy |

| ZO-1 | Zonula occludens protein 1 |

| PECAM-1/CD31 | Platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 |

| ICAM | Intercellular adhesion molecule |

| MMPs | Matrix metalloproteinases |

| NADPH | Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate |

| ETS | Erythroid transformation-specific |

| NF-κB | Nuclear factor kappaB |

| JNK | c-Jun N-terminal kinase |

| PI3K | Phosphoinositide 3-kinase |

| Akt | Protein kinase B |

| NMDA | N-methyl-D-aspartic acid |

| AMPA | Alpha-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole propionic acid |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| ERK | Extracellular signal-regulated kinase |

| NOX | NADPH oxidase |

| NLRP3 | N=Nucleotide-binding domain-like receptor protein 3 |

| PPARγ | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma |

| COX-2 | Cyclooxygenase-2 |

| iNOS | Inducible nitric oxide synthase |

| GSK-3β | Glycogen synthase kinase-3β |

| PTS | Pterostilbene |

| Bcl-2 | B-cell lymphoma-2 |

| Bax | BCL-2-associated X |

| MDA | Malondialdehyde |

| SOD | Superoxide dismutase |

| GSH | Glutathione |

| cAMP | Cyclic adenosine monophosphate |

| CREB | cAMP response element-binding protein |

| PSD95 | Postsynaptic density protein 95 |

| PDE4 | Phosphodiesterase4 |

| Nrf2 | Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 |

| AMPK | Adenosine 5′-monophosphate (AMP)-activated protein kinase |

| Ht22 | Mouse hippocampal neuronal cells |

| GA | Gallic acid |

| ADAM10 | A disintegrin and metalloprotease 10 |

| LTP | Long-term potentiation |

| EGCG | Epigallocatechin gallate |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharide |

| TLR4 | Toll-like receptor 4 |

| mTOR | Mammalian target of rapamycin |

| LC3 | II microtubule-associated proteins light chain 3 II |

| PKA | Protein kinase A |

| TrkB | Tropomyosin-related kinase B |

| AChE | Acetylcholinesterase |

| Keap1 | Kelch-1ike ECH-associated protein l |

| GSSG | Glutathione disulfide |

| BAI | Baicalin |

| Cyt-C | Cytochrome-c |

| Sal | Salidroside |

| D-gal | D-galactosamine |

| SIRT1 | Sirtuin 1 |

| NeuN | Neuron-specific nuclear protein |

| ER | Endoplasmic reticulum |

| ICA | Icariin |

| Wnt | Wingless-related integration site |

| PFC | Prefrontal cortex |

| MAP2 | Microtubule-associated protein 2 |

| PNTS | Panax notoginseng Total Saponins |

| HO-1 | Heme oxygenase 1 |

| AS-IV | Astragaloside IV |

| SalA | Salvianic acid A |

References

- Knopman, D.S.; Amieva, H.; Petersen, R.C.; Chételat, G.; Holtzman, D.M.; Hyman, B.T.; Nixon, R.A.; Jones, D.T. Alzheimer disease. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2021, 7, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 2023 Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2023, 19, 1598–1695. Available online: https://www.google.com.hk/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=2ahUKEwiYhMLEy8eCAxXraPUHHb1xAekQFnoECBIQAQ&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.alz.org%2Fmedia%2Fdocuments%2Falzheimers-facts-and-figures.pdf&usg=AOvVaw2Ly7jeUENko7XcPpRpAMy5&opi=89978449 (accessed on 6 November 2023). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.T.; Liu, Y. Epidemiological research progress on Alzheimer’s disease. Chin. J. Prev. Control. Chronic No-Commun. Dis. 2021, 29, 707–711. [Google Scholar]

- Passeri, E.; Elkhoury, K.; Morsink, M.; Broersen, K.; Linder, M.; Tamayol, A.; Malaplate, C.; Yen, F.T.; Arab-Tehrany, E. Alzheimer’s Disease: Treatment Strategies and Their Limitations. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 13954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, M.D.; Sagare, A.P.; Zlokovic, B.V. Blood-brain barrier breakdown in Alzheimer disease and other neurodegenerative disorders. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2018, 14, 133–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, N.L.; Perkins, A.J.; Gao, S.; Skaar, T.C.; Li, L.; Hendrie, H.C.; Fowler, N.; Callahan, C.M.; Boustani, M.A. Adherence and Tolerability of Alzheimer’s Disease Medications: A Pragmatic Randomized Trial. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2017, 65, 1497–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arvanitakis, Z.; Shah, R.C.; Bennett, D.A. Diagnosis and Management of Dementia: Review. JAMA 2019, 322, 1589–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Barve, K.H.; Kumar, M.S. Recent Advancements in Pathogenesis, Diagnostics and Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2020, 18, 1106–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Qiao, P.F.; Wan, C.Q.; Cai, M.; Zhou, N.K.; Li, Q. Role of Blood-Brain Barrier in Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2018, 63, 1223–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villaseñor, R.; Lampe, J.; Schwaninger, M.; Collin, L. Intracellular transport and regulation of transcytosis across the blood-brain barrier. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2019, 76, 1081–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamazaki, Y.; Kanekiyo, T. Blood-Brain Barrier Dysfunction and the Pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daneman, R.; Prat, A. The blood-brain barrier. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2015, 7, a020412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brightman, M.W.; Reese, T.S. Junctions between intimately apposed cell membranes in the vertebrate brain. J. Cell Biol. 1969, 40, 648–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pappenheimer, J.R.; Renkin, E.M.; Borrero, L.M. Filtration, diffusion and molecular sieving through peripheral capillary membranes; a contribution to the pore theory of capillary permeability. Am. J. Physiol. 1951, 167, 13–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chow, B.W.; Gu, C. The molecular constituents of the blood-brain barrier. Trends Neurosci. 2015, 38, 598–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikitsh, J.L.; Chacko, A.M. Pathways for small molecule delivery to the central nervous system across the blood-brain barrier. Perspect. Medicin Chem. 2014, 6, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, G.; Gan, L.S. Receptor-mediated endocytosis and brain delivery of therapeutic biologics. Int. J. Cell Biol. 2013, 2013, 703545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, N.R.; Daneman, R.; Dziegielewska, K.M.; Liddelow, S.A. Transporters of the blood-brain and blood-CSF interfaces in development and in the adult. Mol. Aspects Med. 2013, 34, 742–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löscher, W.; Potschka, H. Role of drug efflux transporters in the brain for drug disposition and treatment of brain diseases. Prog. Neurobiol. 2005, 76, 22–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ransohoff, R.M.; Engelhardt, B. The anatomical and cellular basis of immune surveillance in the central nervous system. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2012, 12, 623–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasile, F.; Dossi, E.; Rouach, N. Human astrocytes: Structure and functions in the healthy brain. Brain Struct. Funct. 2017, 222, 2017–2029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, N.J.; Rönnbäck, L.; Hansson, E. Astrocyte-endothelial interactions at the blood-brain barrier. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2006, 7, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preininger, M.K.; Kaufer, D. Blood-Brain Barrier Dysfunction and Astrocyte Senescence as Reciprocal Drivers of Neuropathology in Aging. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 6217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carpanini, S.M.; Torvell, M.; Morgan, B.P. Therapeutic Inhibition of the Complement System in Diseases of the Central Nervous System. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falsig, J.; Pörzgen, P.; Lund, S.; Schrattenholz, A.; Leist, M. The inflammatory transcriptome of reactive murine astrocytes and implications for their innate immune function. J. Neurochem. 2006, 96, 893–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priego, N.; Valiente, M. The Potential of Astrocytes as Immune Modulators in Brain Tumors. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidoryk-Wegrzynowicz, M.; Wegrzynowicz, M.; Lee, E.; Bowman, A.B.; Aschner, M. Role of astrocytes in brain function and disease. Toxicol. Pathol. 2011, 39, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acosta, C.; Anderson, H.D.; Anderson, C.M. Astrocyte dysfunction in Alzheimer disease. J. Neurosci. Res. 2017, 95, 2430–2447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guérit, S.; Fidan, E.; Macas, J.; Czupalla, C.J.; Figueiredo, R.; Vijikumar, A.; Yalcin, B.H.; Thom, S.; Winter, P.; Gerhardt, H.; et al. Astrocyte-derived Wnt growth factors are required for endothelial blood-brain barrier maintenance. Prog. Neurobiol. 2021, 199, 101937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, W.; Wu, Q.; Yuan, C.; Gao, J.; Xiao, M.; Gu, M.; Ding, J.; Hu, G. Aquaporin-4 mediates astrocyte response to β-amyloid. Mol. Cell Neurosci. 2012, 49, 406–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoshi, A.; Yamamoto, T.; Shimizu, K.; Ugawa, Y.; Nishizawa, M.; Takahashi, H.; Kakita, A. Characteristics of aquaporin expression surrounding senile plaques and cerebral amyloid angiopathy in Alzheimer disease. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2012, 71, 750–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daneman, R.; Zhou, L.; Kebede, A.A.; Barres, B.A. Pericytes are required for blood-brain barrier integrity during embryogenesis. Nature 2010, 468, 562–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, R.A.; Miners, J.S.; Love, S. Pathological changes within the cerebral vasculature in Alzheimer’s disease: New perspectives. Brain Pathol. 2022, 32, e13061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeske, R.; Albo, J.; Marzano, M.; Bejoy, J.; Li, Y. Engineering Brain-Specific Pericytes from Human Pluripotent Stem Cells. Tissue Eng. Part B Rev. 2020, 26, 367–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, R.N.; Turczyn, T.J.; Das, A. Pericyte coverage of retinal and cerebral capillaries. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1990, 31, 999–1007. [Google Scholar]

- Allt, G.; Lawrenson, J.G. Pericytes: Cell biology and pathology. Cells Tissues Organs 2001, 169, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armulik, A.; Mäe, M.; Betsholtz, C. Pericytes and the blood-brain barrier: Recent advances and implications for the delivery of CNS therapy. Ther. Deliv. 2011, 2, 419–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armulik, A.; Genové, G.; Betsholtz, C. Pericytes: Developmental, physiological, and pathological perspectives, problems, and promises. Dev. Cell. 2011, 21, 193–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, L.S.; Foster, C.G.; Courtney, J.M.; King, N.E.; Howells, D.W.; Sutherland, B.A. Pericytes and Neurovascular Function in the Healthy and Diseased Brain. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2019, 13, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, K.; Niu, F.; Hu, G.; Buch, S. Morphine-mediated release of astrocyte-derived extracellular vesicle miR-23a induces loss of pericyte coverage at the blood-brain barrier: Implications for neuroinflammation. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 984375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goncalves, A.; Antonetti, D.A. Transgenic animal models to explore and modulate the blood brain and blood retinal barriers of the CNS. Fluids Barriers CNS 2022, 19, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rustenhoven, J.; Jansson, D.; Smyth, L.C.; Dragunow, M. Brain Pericytes As Mediators of Neuroinflammation. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2017, 38, 291–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obermeier, B.; Daneman, R.; Ransohoff, R.M. Development, maintenance and disruption of the blood-brain barrier. Nat. Med. 2013, 19, 1584–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribatti, D.; Nico, B.; Crivellato, E. The role of pericytes in angiogenesis. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 2011, 55, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, E.A.; Bell, R.D.; Zlokovic, B.V. Central nervous system pericytes in health and disease. Nat. Neurosci. 2011, 14, 1398–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dore-Duffy, P. Pericytes: Pluripotent cells of the blood brain barrier. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2008, 14, 1581–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sixt, M.; Engelhardt, B.; Pausch, F.; Hallmann, R.; Wendler, O.; Sorokin, L.M. Endothelial cell laminin isoforms, laminins 8 and 10, play decisive roles in T cell recruitment across the blood-brain barrier in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J. Cell Biol. 2001, 153, 933–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallmann, R.; Horn, N.; Selg, M.; Wendler, O.; Pausch, F.; Sorokin, L.M. Expression and function of laminins in the embryonic and mature vasculature. Physiol. Rev. 2005, 85, 979–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Turnbull, J.; Guimond, S. Extracellular matrix and cell signalling: The dynamic cooperation of integrin, proteoglycan and growth factor receptor. J. Endocrinol. 2011, 209, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baeten, K.M.; Akassoglou, K. Extracellular matrix and matrix receptors in blood-brain barrier formation and stroke. Dev. Neurobiol. 2011, 71, 1018–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hynes, R.O. The extracellular matrix: Not just pretty fibrils. Science 2009, 326, 1216–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvey, P.M.; Hendey, B.; Monahan, A.J. The blood-brain barrier in neurodegenerative disease: A rhetorical perspective. J. Neurochem. 2009, 111, 291–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, L.; Nirwane, A.; Yao, Y. Basement membrane and blood-brain barrier. Stroke Vasc. Neurol. 2019, 4, 78–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savettieri, G.; Di Liegro, I.; Catania, C.; Licata, L.; Pitarresi, G.L.; D’agostino, S.; Schiera, G.; De Caro, V.; Giandalia, G.; Giannola, L.I.; et al. Neurons and ECM regulate occludin localization in brain endothelial cells. Neuroreport 2000, 11, 1081–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Milner, R. Fibronectin promotes brain capillary endothelial cell survival and proliferation through alpha5beta1 and alphavbeta3 integrins via MAP kinase signalling. J. Neurochem. 2006, 96, 148–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milner, R.; Campbell, I.L. Developmental regulation of beta1 integrins during angiogenesis in the central nervous system. Mol. Cell Neurosci. 2002, 20, 616–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, N.J. Blood-brain barrier structure and function and the challenges for CNS drug delivery. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2013, 36, 437–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agúndez, J.A.; Jiménez-Jiménez, F.J.; Alonso-Navarro, H.; García-Martín, E. Drug and xenobiotic biotransformation in the blood-brain barrier: A neglected issue. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2014, 8, 335. [Google Scholar]

- Zenaro, E.; Piacentino, G.; Constantin, G. The blood-brain barrier in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 2017, 107, 41–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Sur, S.; Liu, P.; Li, Y.; Jiang, D.; Hou, X.; Darrow, J.; Pillai, J.J.; Yasar, S.; Rosenberg, P.; et al. Blood-Brain Barrier Breakdown in Relationship to Alzheimer and Vascular Disease. Ann. Neurol. 2021, 90, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, D.R.; Hawkins, R.A.; Viña, J.R. Editorial: Organization and Functional Properties of the Blood-Brain Barrier. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 796030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Profaci, C.P.; Munji, R.N.; Pulido, R.S.; Daneman, R. The blood-brain barrier in health and disease: Important unanswered questions. J. Exp. Med. 2020, 217, e20190062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiwari, S.; Atluri, V.; Kaushik, A.; Yndart, A.; Nair, M. Alzheimer’s disease: Pathogenesis, diagnostics, and therapeutics. Int. J. Nanomed. 2019, 14, 5541–5554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dieckmann, M.; Dietrich, M.F.; Herz, J. Lipoprotein receptors—An evolutionarily ancient multifunctional receptor family. Biol. Chem. 2010, 391, 1341–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michalicova, A.; Banks, W.A.; Legath, J.; Kovac, A. Tauopathies—Focus on Changes at the Neurovascular Unit. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2017, 14, 790–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos-Cejudo, J.; Wisniewski, T.; Marmar, C.; Zetterberg, H.; Blennow, K.; De Leon, M.J.; Fossati, S. Traumatic Brain Injury and Alzheimer’s Disease: The Cerebrovascular Link. EBioMedicine 2018, 28, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojala, J.O.; Sutinen, E.M. The Role of Interleukin-18, Oxidative Stress and Metabolic Syndrome in Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Clin. Med. 2017, 6, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, W.A.; Kovac, A.; Majerova, P.; Bullock, K.M.; Shi, M.; Zhang, J. Tau Proteins Cross the Blood-Brain Barrier. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2017, 55, 411–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul, H.M.; Sama, M.A.; Furman, J.L.; Mathis, D.M.; Beckett, T.L.; Weidner, A.M.; Patel, E.S.; Baig, I.; Murphy, M.P.; Levine, H., 3rd; et al. Cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease is associated with selective changes in calcineurin/NFAT signaling. J. Neurosci. 2009, 29, 12957–12969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.H.; Kang, J.W.; Kim, D.K.; Baik, S.H.; Kim, K.H.; Shanta, S.R.; Jung, J.H.; Mook-Jung, I.; Kim, K.P. Global changes of phospholipids identified by MALDI imaging mass spectrometry in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Lipid Res. 2016, 57, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogels, T.; Murgoci, A.N.; Hromádka, T. Intersection of pathological tau and microglia at the synapse. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2019, 7, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nixon, R.A.; Wegiel, J.; Kumar, A.; Yu, W.H.; Peterhoff, C.; Cataldo, A.; Cuervo, A.M. Extensive involvement of autophagy in Alzheimer disease: An immuno-electron microscopy study. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2005, 64, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, E.E.; Greenberg, S.M. Beta-amyloid, blood vessels, and brain function. Stroke 2009, 40, 2601–2606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenowitz, W.D.; Nelson, P.T.; Besser, L.M.; Heller, K.B.; Kukull, W.A. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy and its co-occurrence with Alzheimer’s disease and other cerebrovascular neuropathologic changes. Neurobiol. Aging 2015, 36, 2702–2708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jellinger, K. Prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease in very elderly people: A prospective neuropathological study. Neurology 2002, 58, 671–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartzokis, G.; Cummings, J.L.; Sultzer, D.; Henderson, V.W.; Nuechterlein, K.H.; Mintz, J. White matter structural integrity in healthy aging adults and patients with Alzheimer disease: A magnetic resonance imaging study. Arch. Neurol. 2003, 60, 393–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oikari, L.E.; Pandit, R.; Stewart, R.; Cuní-López, C.; Quek, H.; Sutharsan, R.; Rantanen, L.M.; Oksanen, M.; Lehtonen, S.; De Boer, C.M.; et al. Altered Brain Endothelial Cell Phenotype from a Familial Alzheimer Mutation and Its Potential Implications for Amyloid Clearance and Drug Delivery. Stem Cell Rep. 2020, 14, 924–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.C.; Yamazaki, Y.; Heckman, M.G.; Martens, Y.A.; Jia, L.; Yamazaki, A.; Diehl, N.N.; Zhao, J.; Zhao, N.; Deture, M.; et al. Tau and apolipoprotein E modulate cerebrovascular tight junction integrity independent of cerebral amyloid angiopathy in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2020, 16, 1372–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, S.; Cai, X.; Li, W.; Zhang, Z.; Dong, W.; Hui, G. Elevated plasma endothelial microparticles in Alzheimer’s disease. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 2012, 34, 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magaki, S.; Tang, Z.; Tung, S.; Williams, C.K.; Lo, D.; Yong, W.H.; Khanlou, N.; Vinters, H.V. The effects of cerebral amyloid angiopathy on integrity of the blood-brain barrier. Neurobiol. Aging 2018, 70, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nielsen, H.M.; Londos, E.; Minthon, L.; Janciauskiene, S.M. Soluble adhesion molecules and angiotensin-converting enzyme in dementia. Neurobiol. Dis. 2007, 26, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, L.; Uekawa, K.; Garcia-Bonilla, L.; Koizumi, K.; Murphy, M.; Pistik, R.; Younkin, L.; Younkin, S.; Zhou, P.; Carlson, G.; et al. Brain Perivascular Macrophages Initiate the Neurovascular Dysfunction of Alzheimer Aβ Peptides. Circ. Res. 2017, 121, 258–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.Y.; Bai, K.; Liu, X.H.; Zhang, L.M.; Yu, G.R. Hyperoside protects the blood-brain barrier from neurotoxicity of amyloid beta 1-42. Neural Regen. Res. 2018, 13, 1974–1980. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bhatia, K.; Ahmad, S.; Kindelin, A.; Ducruet, A.F. Complement C3a receptor-mediated vascular dysfunction: A complex interplay between aging and neurodegeneration. J. Clin. Investig. 2021, 131, e144348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haarmann, A.; Nowak, E.; Deiß, A.; Van Der Pol, S.; Monoranu, C.M.; Kooij, G.; Müller, N.; Van Der Valk, P.; Stoll, G.; De Vries, H.E.; et al. Soluble VCAM-1 impairs human brain endothelial barrier integrity via integrin α-4-transduced outside-in signaling. Acta Neuropathol. 2015, 129, 639–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Shi, S.X.; Liu, N.; Jiang, Y.; Karim, M.S.; Vodovoz, S.J.; Wang, X.; Zhang, B.; Dumont, A.S. Caveolae-Mediated Endothelial Transcytosis across the Blood-Brain Barrier in Acute Ischemic Stroke. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 3795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bock, M.; Van Haver, V.; Vandenbroucke, R.E.; Decrock, E.; Wang, N.; Leybaert, L. Into rather unexplored terrain-transcellular transport across the blood-brain barrier. Glia 2016, 64, 1097–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandit, R.; Koh, W.K.; Sullivan, R.K.P.; Palliyaguru, T.; Parton, R.G.; Götz, J. Role for caveolin-mediated transcytosis in facilitating transport of large cargoes into the brain via ultrasound. J. Control. Release 2020, 327, 667–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurnik, S.; Devraj, K.; Macas, J.; Yamaji, M.; Starke, J.; Scholz, A.; Sommer, K.; Di Tacchio, M.; Vutukuri, R.; Beck, H.; et al. Angiopoietin-2-induced blood-brain barrier compromise and increased stroke size are rescued by VE-PTP-dependent restoration of Tie2 signaling. Acta Neuropathol. 2016, 131, 753–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Shen, L.; Han, B.; Yao, H. Involvement of noncoding RNA in blood-brain barrier integrity in central nervous system disease. Noncoding RNA Res. 2021, 6, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez-Villaseñor, I.; Smith, C.I.; Thang, Y.J.R.; Heath, P.R.; Wharton, S.B.; Blackburn, D.J.; Ridger, V.C.; Simpson, J.E. RNA-Seq Profiling of Neutrophil-Derived Microvesicles in Alzheimer’s Disease Patients Identifies a miRNA Signature That May Impact Blood-Brain Barrier Integrity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 5913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tharakan, B.; Hunter, F.A.; Muthusamy, S.; Randolph, S.; Byrd, C.; Rao, V.N.; Reddy, E.S.P.; Childs, E.W. ETS-Related Gene Activation Preserves Adherens Junctions and Permeability in Microvascular Endothelial Cells. Shock 2022, 57, 309–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, S.S.; Lee, H.J.; Lim, I.; Satoh, J.; Kim, S.U. Human astrocytes: Secretome profiles of cytokines and chemokines. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e92325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Reyes, R.E.; Nava-Mesa, M.O.; Vargas-Sánchez, K.; Ariza-Salamanca, D.; Mora-Muñoz, L. Involvement of Astrocytes in Alzheimer’s Disease from a Neuroinflammatory and Oxidative Stress Perspective. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2017, 10, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, Y.F.; Wang, B.J.; Cheng, H.T.; Kuo, L.H.; Wolfe, M.S. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha, interleukin-1beta, and interferon-gamma stimulate gamma-secretase-mediated cleavage of amyloid precursor protein through a JNK-dependent MAPK pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 49523–49532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makitani, K.; Nakagawa, S.; Izumi, Y.; Akaike, A.; Kume, T. Inhibitory effect of donepezil on bradykinin-induced increase in the intracellular calcium concentration in cultured cortical astrocytes. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2017, 134, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsen, L.H.; Witter, M.P.; Sonnewald, U. Neuronal and astrocytic metabolism in a transgenic rat model of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Cereb. Blood Flow. Metab. 2014, 34, 906–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Prince, G.; Delaere, P.; Fages, C.; Lefrançois, T.; Touret, M.; Salanon, M.; Tardy, M. Glutamine synthetase (GS) expression is reduced in senile dementia of the Alzheimer type. Neurochem. Res. 1995, 20, 859–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, S.R. Neuronal expression of glutamine synthetase in Alzheimer’s disease indicates a profound impairment of metabolic interactions with astrocytes. Neurochem. Int. 2000, 36, 471–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parameshwaran, K.; Dhanasekaran, M.; Suppiramaniam, V. Amyloid beta peptides and glutamatergic synaptic dysregulation. Exp. Neurol. 2008, 210, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mota, S.I.; Ferreira, I.L.; Rego, A.C. Dysfunctional synapse in Alzheimer’s disease—A focus on NMDA receptors. Neuropharmacology 2014, 76 Pt A, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedland-Leuner, K.; Stockburger, C.; Denzer, I.; Eckert, G.P.; Müller, W.E. Mitochondrial dysfunction: Cause and consequence of Alzheimer’s disease. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 2014, 127, 183–210. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Palmer, C.S.; Anderson, A.J.; Stojanovski, D. Mitochondrial protein import dysfunction: Mitochondrial disease, neurodegenerative disease and cancer. FEBS Lett. 2021, 595, 1107–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhat, A.H.; Dar, K.B.; Anees, S.; Zargar, M.A.; Masood, A.; Sofi, M.A.; Ganie, S.A. Oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction and neurodegenerative diseases; a mechanistic insight. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2015, 74, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, M.T. Oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction-linked neurodegenerative disorders. Neurol. Res. 2017, 39, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askarova, S.; Yang, X.; Sheng, W.; Sun, G.Y.; Lee, J.C. Role of Aβ-receptor for advanced glycation endproducts interaction in oxidative stress and cytosolic phospholipase A2 activation in astrocytes and cerebral endothelial cells. Neuroscience 2011, 199, 375–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.; Lai, Y.; Shelat, P.B.; Hu, C.; Sun, G.Y.; Lee, J.C. Phospholipases A2 mediate amyloid-beta peptide-induced mitochondrial dysfunction. J. Neurosci. 2006, 26, 11111–11119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montagne, A.; Zhao, Z.; Zlokovic, B.V. Alzheimer’s disease: A matter of blood-brain barrier dysfunction? J. Exp. Med. 2017, 214, 3151–3169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boespflug, E.L.; Simon, M.J.; Leonard, E.; Grafe, M.; Woltjer, R.; Silbert, L.C.; Kaye, J.A.; Iliff, J.J. Targeted Assessment of Enlargement of the Perivascular Space in Alzheimer’s Disease and Vascular Dementia Subtypes Implicates Astroglial Involvement Specific to Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2018, 66, 1587–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeppenfeld, D.M.; Simon, M.; Haswell, J.D.; D’abreo, D.; Murchison, C.; Quinn, J.F.; Grafe, M.R.; Woltjer, R.L.; Kaye, J.; Iliff, J.J. Association of Perivascular Localization of Aquaporin-4 with Cognition and Alzheimer Disease in Aging Brains. JAMA Neurol. 2017, 74, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilcock, D.M.; Vitek, M.P.; Colton, C.A. Vascular amyloid alters astrocytic water and potassium channels in mouse models and humans with Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroscience 2009, 159, 1055–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iadecola, C. The pathobiology of vascular dementia. Neuron 2013, 80, 844–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanchard, J.W.; Bula, M.; Davila-Velderrain, J.; Akay, L.A.; Zhu, L.; Frank, A.; Victor, M.B.; Bonner, J.M.; Mathys, H.; Lin, Y.T.; et al. Reconstruction of the human blood-brain barrier in vitro reveals a pathogenic mechanism of APOE4 in pericytes. Nat. Med. 2020, 26, 952–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamazaki, Y.; Shinohara, M.; Yamazaki, A.; Ren, Y.; Asmann, Y.W.; Kanekiyo, T.; Bu, G. ApoE (Apolipoprotein E) in Brain Pericytes Regulates Endothelial Function in an Isoform-Dependent Manner by Modulating Basement Membrane Components. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2020, 40, 128–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhelmus, M.M.; Otte-Höller, I.; Van Triel, J.J.; Veerhuis, R.; Maat-Schieman, M.L.; Bu, G.; De Waal, R.M.; Verbeek, M.M. Lipoprotein receptor-related protein-1 mediates amyloid-beta-mediated cell death of cerebrovascular cells. Am. J. Pathol. 2007, 171, 1989–1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halliday, M.R.; Rege, S.V.; Ma, Q.; Zhao, Z.; Miller, C.A.; Winkler, E.A.; Zlokovic, B.V. Accelerated pericyte degeneration and blood-brain barrier breakdown in apolipoprotein E4 carriers with Alzheimer’s disease. J. Cereb. Blood Flow. Metab. 2016, 36, 216–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourassa, P.; Tremblay, C.; Schneider, J.A.; Bennett, D.A.; Calon, F. Brain mural cell loss in the parietal cortex in Alzheimer’s disease correlates with cognitive decline and TDP-43 pathology. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 2020, 46, 458–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keable, A.; Fenna, K.; Yuen, H.M.; Johnston, D.A.; Smyth, N.R.; Smith, C.; Al-Shahi Salman, R.; Samarasekera, N.; Nicoll, J.A.; Attems, J.; et al. Deposition of amyloid β in the walls of human leptomeningeal arteries in relation to perivascular drainage pathways in cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2016, 1862, 1037–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merlini, M.; Wanner, D.; Nitsch, R.M. Tau pathology-dependent remodelling of cerebral arteries precedes Alzheimer’s disease-related microvascular cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Acta Neuropathol. 2016, 131, 737–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, M.J.; Damodarasamy, M.; Banks, W.A. The extracellular matrix of the blood-brain barrier: Structural and functional roles in health, aging, and Alzheimer’s disease. Tissue Barriers 2019, 7, 1651157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J.; Kahle, M.P.; Bix, G.J. Perlecan and the blood-brain barrier: Beneficial proteolysis? Front. Pharmacol. 2012, 3, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, H.M.; Palmqvist, S.; Minthon, L.; Londos, E.; Wennström, M. Gender-dependent levels of hyaluronic acid in cerebrospinal fluid of patients with neurodegenerative dementia. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2012, 9, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Nägga, K.; Hansson, O.; Van Westen, D.; Minthon, L.; Wennström, M. Increased levels of hyaluronic acid in cerebrospinal fluid in patients with vascular dementia. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2014, 42, 1435–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reed, M.J.; Damodarasamy, M.; Pathan, J.L.; Chan, C.K.; Spiekerman, C.; Wight, T.N.; Banks, W.A.; Day, A.J.; Vernon, R.B.; Keene, C.D. Increased Hyaluronan and TSG-6 in Association with Neuropathologic Changes of Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2019, 67, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Li, C.; Guo, H.; Kern, T.S.; Huang, K.; Zheng, L. Curcumin inhibits neuronal and vascular degeneration in retina after ischemia and reperfusion injury. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e23194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, G.P.; Chu, T.; Yang, F.; Beech, W.; Frautschy, S.A.; Cole, G.M. The curry spice curcumin reduces oxidative damage and amyloid pathology in an Alzheimer transgenic mouse. J. Neurosci. 2001, 21, 8370–8377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Lim, G.P.; Begum, A.N.; Ubeda, O.J.; Simmons, M.R.; Ambegaokar, S.S.; Chen, P.P.; Kayed, R.; Glabe, C.G.; Frautschy, S.A.; et al. Curcumin inhibits formation of amyloid beta oligomers and fibrils, binds plaques, and reduces amyloid in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 5892–5901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, P.H.; Manczak, M.; Yin, X.; Grady, M.C.; Mitchell, A.; Tonk, S.; Kuruva, C.S.; Bhatti, J.S.; Kandimalla, R.; Vijayan, M.; et al. Protective Effects of Indian Spice Curcumin Against Amyloid-β in Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2018, 61, 843–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Browne, A.; Child, D.; Tanzi, R.E. Curcumin decreases amyloid-beta peptide levels by attenuating the maturation of amyloid-beta precursor protein. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 28472–28480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.J.; Li, Z.H.; Liu, L.; Tang, W.X.; Wang, Y.; Dong, M.R.; Xiao, C. Curcumin Attenuates Beta-Amyloid-Induced Neuroinflammation via Activation of Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor-Gamma Function in a Rat Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Front. Pharmacol. 2016, 7, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Zheng, X.; Tang, H.; Zhao, L.; He, C.; Zou, Y.; Song, X.; Li, L.; Yin, Z.; Ye, G. A network pharmacology approach to identify the mechanisms and molecular targets of curcumin against Alzheimer disease. Medicine 2022, 101, e30194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, P.H.; Manczak, M.; Yin, X.; Grady, M.C.; Mitchell, A.; Kandimalla, R.; Kuruva, C.S. Protective effects of a natural product, curcumin, against amyloid β induced mitochondrial and synaptic toxicities in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Investig. Med. 2016, 64, 1220–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Wang, N.; Liu, X. Resveratrol and Amyloid-Beta: Mechanistic Insights. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, A.; Sarkar, C.; Singh, S.P.; Zhang, Z.; Munasinghe, J.; Peng, S.; Chandra, G.; Kong, E.; Mukherjee, A.B. The blood-brain barrier is disrupted in a mouse model of infantile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis: Amelioration by resveratrol. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2012, 21, 2233–2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moussa, C.; Hebron, M.; Huang, X.; Ahn, J.; Rissman, R.A.; Aisen, P.S.; Turner, R.S. Resveratrol regulates neuro-inflammation and induces adaptive immunity in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neuroinflamm. 2017, 14, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.F.; Li, N.; Wang, Q.; Cheng, X.J.; Li, X.M.; Liu, T.T. Resveratrol decreases the insoluble Aβ1-42 level in hippocampus and protects the integrity of the blood-brain barrier in AD rats. Neuroscience 2015, 310, 641–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slevin, M.; Ahmed, N.; Wang, Q.; Mcdowell, G.; Badimon, L. Unique vascular protective properties of natural products: Supplements or future main-line drugs with significant anti-atherosclerotic potential? Vasc. Cell 2012, 4, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, L.M.; Rodrigues, D.; Alemi, M.; Silva, S.C.; Ribeiro, C.A.; Cardoso, I. Resveratrol administration increases Transthyretin protein levels ameliorating AD features: Importance of transthyretin tetrameric stability. Mol. Med. 2016, 22, 597–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.R.; Li, S.; Lin, C.C. Effect of resveratrol and pterostilbene on aging and longevity. Biofactors 2018, 44, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.; Seo, K.H.; Yokoyama, W. Chemistry of Pterostilbene and Its Metabolic Effects. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 12836–12841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Cui, L.; Zhou, G.; Jing, H.; Guo, Y.; Sun, W. Pterostilbene, a natural small-molecular compound, promotes cytoprotective macroautophagy in vascular endothelial cells. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2013, 24, 903–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.C.; Hsieh, M.J.; Peng, C.H.; Yang, S.F.; Huang, C.N. Pterostilbene Inhibits Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells Migration and Matrix Metalloproteinase-2 through Modulation of MAPK Pathway. J. Food Sci. 2015, 80, H2331–H2335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Li, X.; Tian, B.; Chen, L. Protective effect of pterostilbene in a streptozotocin-induced mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease by targeting monoamine oxidase B. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2022, 42, 1777–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Chen, L.; Liu, X.; Li, X.; Cao, Y.; Bai, Y.; Qi, F. Pterostilbene inhibits amyloid-β-induced neuroinflammation in a microglia cell line by inactivating the NLRP3/caspase-1 inflammasome pathway. J. Cell Biochem. 2018, 119, 7053–7062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, J.; Chen, Y.; Bi, F.; Li, H.; Chang, C.; Liu, W. Pterostilbene attenuates amyloid-β induced neurotoxicity with regulating PDE4A-CREB-BDNF pathway. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2019, 11, 6356–6369. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Liu, J.; Li, Q.; Mi, Y.; Zhou, D.; Meng, Q.; Chen, G.; Li, N.; Hou, Y. Pterostilbene Alleviates Aβ1–42-Induced Cognitive Dysfunction via Inhibition of Oxidative Stress by Activating Nrf2 Signaling Pathway. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2021, 65, e2000711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Qiu, X.; Wu, Q.; Chang, F.; Zhou, T.; Zhou, M.; Pei, J. Active constituents of saffron (Crocus sativus L.) and their prospects in treating neurodegenerative diseases (Review). Exp. Ther. Med. 2023, 25, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, Z.; Hong, J.; Cui, L.; Hao, Y.; Cheng, G.; Tan, R. Crocetin Regulates Functions of Neural Stem Cells to Generate New Neurons for Cerebral Ischemia Recovery. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2023, 12, e2203132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bie, X.; Chen, Y.; Zheng, X.; Dai, H. The role of crocetin in protection following cerebral contusion and in the enhancement of angiogenesis in rats. Fitoterapia 2011, 82, 997–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wani, A.; Al Rihani, S.B.; Sharma, A.; Weadick, B.; Govindarajan, R.; Khan, S.U.; Sharma, P.R.; Dogra, A.; Nandi, U.; Reddy, C.N.; et al. Crocetin promotes clearance of amyloid-β by inducing autophagy via the STK11/LKB1-mediated AMPK pathway. Autophagy 2021, 17, 3813–3832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, C.; Liu, H.; Ju, C.; Yuan, F.; Ning, J.; Shang, M.; Bao, X.; Yu, Y.; Yao, X.; Zhang, D. Gardenia jasminoides J. Ellis extract alleviated white matter damage through promoting the differentiation of oligodendrocyte precursor cells via suppressing neuroinflammation. Food Funct. 2022, 13, 2131–2141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Dong, X.; Liu, J. Crocetin attenuates inflammation and amyloid-β accumulation in APPsw transgenic mice. Immun. Ageing 2018, 15, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Y.; Kong, L.P.; Luo, T.; Li, G.W.; Jiang, W.; Li, S.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, H.Q. The protective effects of crocetin on aβ1–42-induced toxicity in Ht22 cells. CNS Neurol. Disord. Drug Targets 2014, 13, 1627–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hseu, Y.C.; Chen, S.C.; Lin, W.H.; Hung, D.Z.; Lin, M.K.; Kuo, Y.H.; Wang, M.T.; Cho, H.J.; Wang, L.; Yang, H.L. Toona sinensis (leaf extracts) inhibit vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-induced angiogenesis in vascular endothelial cells. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2011, 134, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.L.; Huang, P.J.; Liu, Y.R.; Kumar, K.J.; Hsu, L.S.; Lu, T.L.; Chia, Y.C.; Takajo, T.; Kazunori, A.; Hseu, Y.C. Toona sinensis inhibits LPS-induced inflammation and migration in vascular smooth muscle cells via suppression of reactive oxygen species and NF-κB signaling pathway. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2014, 2014, 901315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mori, T.; Koyama, N.; Yokoo, T.; Segawa, T.; Maeda, M.; Sawmiller, D.; Tan, J.; Town, T. Gallic acid is a dual α/β-secretase modulator that reverses cognitive impairment and remediates pathology in Alzheimer mice. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 16251–16266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajipour, S.; Sarkaki, A.; Farbood, Y.; Eidi, A.; Mortazavi, P.; Valizadeh, Z. Effect of Gallic Acid on Dementia Type of Alzheimer Disease in Rats: Electrophysiological and Histological Studies. Basic Clin. Neurosci. 2016, 7, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Chen, X.; Liu, J.; Ma, Q.; Zhuo, Z.; Chen, H.; Zhou, L.; Yang, S.; Zheng, L.; Ning, C.; et al. Gallic acid disruption of Aβ(1–42) aggregation rescues cognitive decline of APP/PS1 double transgenic mouse. Neurobiol. Dis. 2019, 124, 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Jing, D.; Shi, M.; Liu, Y.; Lin, T.; Xie, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Zhao, H.; Shi, X.; Du, F.; et al. Epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) attenuates infrasound-induced neuronal impairment by inhibiting microglia-mediated inflammation. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2014, 25, 716–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohd Sabri, N.A.; Lee, S.K.; Murugan, D.D.; Ling, W.C. Epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) alleviates vascular dysfunction in angiotensin II-infused hypertensive mice by modulating oxidative stress and eNOS. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 17633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Payne, A.; Nahashon, S.; Taka, E.; Adinew, G.M.; Soliman, K.F.A. Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate (EGCG): New Therapeutic Perspectives for Neuroprotection, Aging, and Neuroinflammation for the Modern Age. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, X.; Liu, M.; Yao, W.; Du, K.; He, M.; Jin, X.; Jiao, L.; Ma, G.; Wei, B.; Wei, M. Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate Attenuates Microglial Inflammation and Neurotoxicity by Suppressing the Activation of Canonical and Noncanonical Inflammasome via TLR4/NF-κB Pathway. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2019, 63, e1801230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nan, S.; Wang, P.; Zhang, Y.; Fan, J. Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate Provides Protection Against Alzheimer’s Disease-Induced Learning and Memory Impairments in Rats. Drug Des. Devel Ther. 2021, 15, 2013–2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, T.; Yang, Y.; Zhu, S.; Lu, Y.; Zhu, L.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X. Inhibition of Aβ aggregates in Alzheimer’s disease by epigallocatechin and epicatechin-3-gallate from green tea. Bioorg Chem. 2020, 105, 104382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, X.H.; Luo, F.M.; Wang, E.L.; Fu, M.Y.; Li, T.; Jiang, Y.P.; Liu, S.; Peng, J.; Liu, B. Magnolol alleviates hypoxia-induced pulmonary vascular remodeling through inhibition of phenotypic transformation in pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 150, 113060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Liu, F.; Zhang, R.; Xiong, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Hao, L.; Chen, S. Neuroprotective Potency of Neolignans in Magnolia officinalis Cortex Against Brain Disorders. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 857449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Jia, J. Magnolol improves Alzheimer’s disease-like pathologies and cognitive decline by promoting autophagy through activation of the AMPK/mTOR/ULK1 pathway. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 161, 114473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xian, Y.F.; Qu, C.; Liu, Y.; Ip, S.P.; Yuan, Q.J.; Yang, W.; Lin, Z.X. Magnolol Ameliorates Behavioral Impairments and Neuropathology in a Transgenic Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2020, 2020, 5920476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Zhao, J.; Wang, H.; Jiang, Y.; Yang, Q.; Fu, Y.; Zeng, H.; Hölscher, C.; Xu, J.; Zhang, Z. Magnolol alleviates Alzheimer’s disease-like pathology in transgenic C. elegans by promoting microglia phagocytosis and the degradation of beta-amyloid through activation of PPAR-γ. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 124, 109886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; Fang, Y.; Cui, X.; Jia, R.; Kang, X.; Zhao, R. Magnolol upregulates CHRM1 to attenuate Amyloid-β-triggered neuronal injury through regulating the cAMP/PKA/CREB pathway. J. Nat. Med. 2022, 76, 188–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, R.; Zhong, J.; Zhou, Q.; Ren, W.; Liu, Z.; Bian, Y. Kaempferol prevents angiogenesis of rat intestinal microvascular endothelial cells induced by LPS and TNF-α via inhibiting VEGF/Akt/p38 signaling pathways and maintaining gut-vascular barrier integrity. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2022, 366, 110135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, X.; Zhou, S.; Nao, J. Kaempferol as a therapeutic agent in Alzheimer’s disease: Evidence from preclinical studies. Ageing Res. Rev. 2023, 87, 101910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva Dos Santos, J.; Gonçalves Cirino, J.P.; De Oliveira Carvalho, P.; Ortega, M.M. The Pharmacological Action of Kaempferol in Central Nervous System Diseases: A Review. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 565700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, T.; He, B.; Xu, M.; Wu, B.; Xiao, F.; Bi, K.; Jia, Y. Kaempferide prevents cognitive decline via attenuation of oxidative stress and enhancement of brain-derived neurotrophic factor/tropomyosin receptor kinase B/cAMP response element-binding signaling pathway. Phytother. Res. 2019, 33, 1065–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babaei, P.; Eyvani, K.; Kouhestani, S. Sex-Independent Cognition Improvement in Response to Kaempferol in the Model of Sporadic Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurochem. Res. 2021, 46, 1480–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouhestani, S.; Jafari, A.; Babaei, P. Kaempferol attenuates cognitive deficit via regulating oxidative stress and neuroinflammation in an ovariectomized rat model of sporadic dementia. Neural Regen. Res. 2018, 13, 1827–1832. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.L.; Cheng, X.; Li, W.H.; Liu, M.; Wang, Y.H.; Du, G.H. Kaempferol Attenuates LPS-Induced Striatum Injury in Mice Involving Anti-Neuroinflammation, Maintaining BBB Integrity, and Down-Regulating the HMGB1/TLR4 Pathway. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Jindal, D.; Kumar, R.; Pancham, P.; Haider, S.; Gupta, V.; Mani, S.; Rachana, R.; Tiwari, R.K.; Chanda, S. Molecular Docking and Network Pharmacology Interaction Analysis of Gingko Biloba (EGB761) Extract with Dual Target Inhibitory Mechanism in Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2023, 93, 705–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deepika; Maurya, P.K. Health Benefits of Quercetin in Age-Related Diseases. Molecules 2022, 27, 2498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhou, S.; Li, J.; Sun, Y.; Hasimu, H.; Liu, R.; Zhang, T. Quercetin protects human brain microvascular endothelial cells from fibrillar β-amyloid1-40-induced toxicity. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2015, 5, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah-Abadi, M.E.; Ariaei, A.; Moradi, F.; Rustamzadeh, A.; Tanha, R.R.; Sadigh, N.; Marzban, M.; Heydari, M.; Ferdousie, V.T. In Silico Interactions of Natural and Synthetic Compounds with Key Proteins Involved in Alzheimer’s Disease: Prospects for Designing New Therapeutics Compound. Neurotox. Res. 2023, 41, 408–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.T.; Ke, J.; Guo, S.F.; Wu, Y.; Bian, Y.F.; Shan, L.L.; Liu, Q.Y.; Huo, Y.J.; Guo, C.; Liu, M.Y.; et al. The Protective Effect of Quercetin on Endothelial Cells Injured by Hypoxia and Reoxygenation. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 732874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Lin, P.; Chen, B.; Zhang, X.; Xiao, W.; Wu, S.; Huang, C.; Feng, D.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, J. Autophagy alleviates hypoxia-induced blood-brain barrier injury via regulation of CLDN5 (claudin 5). Autophagy 2021, 17, 3048–3067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zamanian, M.Y.; Soltani, A.; Khodarahmi, Z.; Alameri, A.A.; Alwan, A.M.R.; Ramírez-Coronel, A.A.; Obaid, R.F.; Abosaooda, M.; Heidari, M.; Golmohammadi, M.; et al. Targeting Nrf2 signaling pathway by quercetin in the prevention and treatment of neurological disorders: An overview and update on new developments. Fundam. Clin. Pharmacol. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rifaai, R.A.; Mokhemer, S.A.; Saber, E.A.; El-Aleem, S.a.A.; El-Tahawy, N.F.G. Neuroprotective effect of quercetin nanoparticles: A possible prophylactic and therapeutic role in alzheimer’s disease. J. Chem. Neuroanat. 2020, 107, 101795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganeshpurkar, A.; Saluja, A.K. The Pharmacological Potential of Rutin. Saudi Pharm. J. 2017, 25, 149–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enogieru, A.B.; Haylett, W.; Hiss, D.C.; Bardien, S.; Ekpo, O.E. Rutin as a Potent Antioxidant: Implications for Neurodegenerative Disorders. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2018, 2018, 6241017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghbelinejad, S.; Nassiri-Asl, M.; Farivar, T.N.; Abbasi, E.; Sheikhi, M.; Taghiloo, M.; Farsad, F.; Samimi, A.; Hajiali, F. Rutin activates the MAPK pathway and BDNF gene expression on beta-amyloid induced neurotoxicity in rats. Toxicol. Lett. 2014, 224, 108–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.Y.; Li, L.J.; Dong, Q.X.; Zhu, J.; Huang, Y.R.; Hou, S.J.; Yu, X.L.; Liu, R.T. Rutin prevents tau pathology and neuroinflammation in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neuroinflamm. 2021, 18, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.X.; Wang, S.W.; Yu, X.L.; Su, Y.J.; Wang, T.; Zhou, W.W.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Y.J.; Liu, R.T. Rutin improves spatial memory in Alzheimer’s disease transgenic mice by reducing Aβ oligomer level and attenuating oxidative stress and neuroinflammation. Behav. Brain Res. 2014, 264, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bermejo-Bescós, P.; Jiménez-Aliaga, K.L.; Benedí, J.; Martín-Aragón, S. A Diet Containing Rutin Ameliorates Brain Intracellular Redox Homeostasis in a Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 4863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zhou, Y.P.; Liu, H.Y.; Gu, J.H.; Zhou, X.F.; Yue-Qin, Z. Long-term oral administration of hyperoside ameliorates AD-related neuropathology and improves cognitive impairment in APP/PS1 transgenic mice. Neurochem. Int. 2021, 151, 105196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, J.H.; Moon, S.; Cho, E.; Kwon, H.; Lee, S.; Jeon, J.; Park, A.Y.; Lee, Y.H.; Kwon, K.J.; Ryu, J.H.; et al. Hyperoside improves learning and memory deficits by amyloid β(1-42) in mice through regulating synaptic calcium-permeable AMPA receptors. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2022, 931, 175188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, L.L.; Qu, Y.Q.; Tang, Y.P.; Chen, X.; Lo, H.H.; Qu, L.Q.; Yun, Y.X.; Wong, V.K.W.; Zhang, R.L.; Wang, H.M.; et al. Hyperoside alleviates toxicity of β-amyloid via endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondrial calcium signal transduction cascade in APP/PS1 double transgenic Alzheimer’s disease mice. Redox Biol. 2023, 61, 102637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Jia, C.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, W.; Zhu, W.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, T. Baicalin relaxes vascular smooth muscle and lowers blood pressure in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 111, 325–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, X.; Liu, M.Y.; Zhang, D.F.; Zhong, X.; Du, K.; Qian, P.; Yao, W.F.; Gao, H.; Wei, M.J. Baicalin mitigates cognitive impairment and protects neurons from microglia-mediated neuroinflammation via suppressing NLRP3 inflammasomes and TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2019, 25, 575–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Li, X.; Gao, P.; Tu, Y.; Zhao, M.; Li, J.; Zhang, S.; Liang, H. Baicalin attenuates alzheimer-like pathological changes and memory deficits induced by amyloid β1-42 protein. Metab. Brain Dis. 2015, 30, 537–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, J.; Wang, C.; Chen, H.; Hu, Y.; Tian, L.; Pan, J.; Geng, M. Aβ-induced microglial cell activation is inhibited by baicalin through the JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway. Int. J. Neurosci. 2014, 124, 609–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; He, C.; Yu, W.; Yang, M.; Li, Z.; Li, P.; Zhu, X.; Xiao, C.; Cheng, S. Baicalin Attenuated Aβ (1-42)-Induced Apoptosis in SH-SY5Y Cells by Inhibiting the Ras-ERK Signaling Pathway. Biomed. Res. Int. 2022, 2022, 9491755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Wang, H.; Zhao, Y.; Sun, D.; Zhai, X. Protective Effects of Baicalin on Aβ1–42-Induced Learning and Memory Deficit, Oxidative Stress, and Apoptosis in Rat. Cell Mol. Neurobiol. 2015, 35, 623–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.Y.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, X.L.; Wang, L.; Zhou, Y.M.; Zhang, F.F.; Zhang, H.T.; Zhao, X.M. Baicalin attenuates amyloid β oligomers induced memory deficits and mitochondria fragmentation through regulation of PDE-PKA-Drp1 signalling. Psychopharmacology 2022, 239, 851–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.B.; Fan, X.Y.; Wang, C.W.; Ye, X.; Wu, C.J. Potentially active compounds that improve PAD through angiogenesis: A review. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 168, 115634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Zhou, R.; You, X.; Luo, F.; He, H.; Chang, X.; Zhu, L.; Ding, X.; Yan, T. Salidroside suppresses inflammation in a D-galactose-induced rat model of Alzheimer’s disease via SIRT1/NF-κB pathway. Metab. Brain Dis. 2016, 31, 771–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Z.; Lu, H.; Yang, S.; Zeng, Y.; Li, W.; Wang, L.; Luo, G.; Fang, F.; Zeng, T.; Cheng, W. Salidroside Attenuates Cognitive Dysfunction in Senescence-Accelerated Mouse Prone 8 (SAMP8) Mice and Modulates Inflammation of the Gut-Brain Axis. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 568423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, Y.; Chai, Y.; Fu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, L.; Miao, M.; Yan, T. Salidroside Ameliorates Alzheimer’s Disease by Targeting NLRP3 Inflammasome-Mediated Pyroptosis. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2021, 13, 809433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Z.L.; Su, H.; Tan, Y.F.; Qiu, Y.J.; Zhu, J.P.; Chen, Y.; Lin, S.S.; Wu, M.H.; Mao, Y.P.; Hu, J.J.; et al. Salidroside protects PC-12 cells against amyloid β-induced apoptosis by activation of the ERK1/2 and AKT signaling pathways. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2019, 43, 1769–1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Li, Q.; Sun, S.; Chen, S. Neuroprotective Effects of Salidroside in a Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Cell Mol. Neurobiol. 2020, 40, 1133–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Xie, Z.; Pei, T.; Zeng, Y.; Xiong, Q.; Wei, H.; Wang, Y.; Cheng, W. Salidroside attenuates neuronal ferroptosis by activating the Nrf2/HO1 signaling pathway in Aβ(1-42)-induced Alzheimer’s disease mice and glutamate-injured HT22 cells. Chin. Med. 2022, 17, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Ren, Z.; Yang, R.; Mei, Y.; Dai, Y.; Cheng, Q.; Xu, C.; Xu, X.; Wang, S.; Kim, K.M.; et al. Salidroside reduces neuropathology in Alzheimer’s disease models by targeting NRF2/SIRT3 pathway. Cell Biosci. 2022, 12, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Wang, L.; Zeng, Y.; Wang, Y.; Pei, T.; Xie, Z.; Xiong, Q.; Wei, H.; Li, W.; Li, J.; et al. Salidroside alleviates cognitive impairment by inhibiting ferroptosis via activation of the Nrf2/GPX4 axis in SAMP8 mice. Phytomedicine 2023, 114, 154762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, B.; Lin, C.; Liu, Q.; He, Y.; Ruganzu, J.B.; Jin, H.; Peng, X.; Ji, S.; Ma, Y.; Yang, W. Tanshinone IIA attenuates neuroinflammation via inhibiting RAGE/NF-κB signaling pathway in vivo and in vitro. J. Neuroinflamm. 2020, 17, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maione, F.; Piccolo, M.; De Vita, S.; Chini, M.G.; Cristiano, C.; De Caro, C.; Lippiello, P.; Miniaci, M.C.; Santamaria, R.; Irace, C.; et al. Down regulation of pro-inflammatory pathways by tanshinone IIA and cryptotanshinone in a non-genetic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Pharmacol. Res. 2018, 129, 482–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Wen, P.Y.; Li, W.W.; Zhou, J. Upregulation effects of Tanshinone IIA on the expressions of NeuN, Nissl body, and IκB and downregulation effects on the expressions of GFAP and NF-κB in the brain tissues of rat models of Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroreport 2015, 26, 758–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, L.; Jadoon, S.S.; Liu, S.Z.; Zhang, R.Y.; Li, F.; Zhang, M.Y.; Ai-Hua, T.; You, Q.Y.; Wang, P. Tanshinone IIA Ameliorates Spatial Learning and Memory Deficits by Inhibiting the Activity of ERK and GSK-3β. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry Neurol. 2019, 32, 152–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, X.; Chen, L.; Wang, Z.; He, Y.; Ruganzu, J.B.; Guo, H.; Zhang, X.; Ji, S.; Zheng, L.; Yang, W. Tanshinone IIA regulates glycogen synthase kinase-3β-related signaling pathway and ameliorates memory impairment in APP/PS1 transgenic mice. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2022, 918, 174772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Han, G.; Wu, K. Tanshinone IIA Alleviates the AD Phenotypes in APP and PS1 Transgenic Mice. Biomed. Res. Int. 2016, 2016, 7631801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Ruganzu, J.B.; Lin, C.; Ding, B.; Zheng, Q.; Wu, X.; Ma, R.; Liu, Q.; Wang, Y.; Jin, H.; et al. Tanshinone IIA ameliorates cognitive deficits by inhibiting endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis in APP/PS1 transgenic mice. Neurochem. Int. 2020, 133, 104610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, C.; Liu, X.Q.; Chen, M.; Ma, H.H.; Wu, G.L.; Qiao, L.J.; Cai, Y.F.; Zhang, S.J. Tanshinone IIA ameliorates Aβ transendothelial transportation through SIRT1-mediated endoplasmic reticulum stress. J. Transl. Med. 2023, 21, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wen, Y.; Sheng, L.; Guo, R.; Zhang, Y.; Shao, L. Icariin activates autophagy to trigger TGFβ1 upregulation and promote angiogenesis in EA.hy926 human vascular endothelial cells. Bioengineered 2022, 13, 164–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Wu, S.; Jin, H.; Wu, J.; Wang, X.; Cao, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Li, L.; Yang, X.; et al. Molecular mechanisms and therapeutic potential of icariin in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Phytomedicine 2023, 116, 154890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhu, T.; Wang, M.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, G.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, E.; Li, X. Icariin Attenuates M1 Activation of Microglia and Aβ Plaque Accumulation in the Hippocampus and Prefrontal Cortex by Up-Regulating PPARγ in Restraint/Isolation-Stressed APP/PS1 Mice. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; Zhu, H.; Liu, X.; Tang, C. Icariin sustains the proliferation and differentiation of Aβ(25–35)-treated hippocampal neural stem cells via the BDNF-TrkB-ERK/Akt signaling pathway. Neurol. Res. 2020, 42, 936–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Qu, J.Q.; Zhou, Y.J.; Zhou, Y.J.; Li, Y.Y.; Huang, N.Q.; Deng, C.M.; Luo, Y. Icariin improves cognitive deficits by reducing the deposition of β-amyloid peptide and inhibition of neurons apoptosis in SAMP8 mice. Neuroreport 2020, 31, 663–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Chen, L.L.; Lan, Z.; Xiong, F.; Xu, X.; Yin, Y.Y.; Li, P.; Wang, P. Icariin Ameliorates Amyloid Pathologies by Maintaining Homeostasis of Autophagic Systems in Aβ(1–42)-Injected Rats. Neurochem. Res. 2019, 44, 2708–2722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.J.; Liu, B.; Wu, Q.; Liu, J.; Xu, Y.Y.; Zhou, S.Y.; Shi, J.S. Icariin Delays Brain Aging in Senescence-Accelerated Mouse Prone 8 (SAMP8) Model via Inhibiting Autophagy. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2019, 369, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.Y.; Liu, Q.P.; An, P.; Jia, M.; Luan, X.; Tang, J.Y.; Zhang, H. Ginsenoside Rd: A promising natural neuroprotective agent. Phytomedicine 2022, 95, 153883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.J.; Yang, Y.; Wan, Y.; Xia, J.; Xu, J.F.; Zhang, L.; Liu, D.; Chen, L.; Tang, F.; Ao, H.; et al. New insights into the role and mechanisms of ginsenoside Rg1 in the management of Alzheimer’s disease. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 152, 113207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhang, C.; Guo, Y.; Li, J.; Wu, C.; Jiao, J.; Zheng, H. Ginsenoside Rg1 improves Alzheimer’s disease by regulating oxidative stress, apoptosis, and neuroinflammation through Wnt/GSK-3β/β-catenin signaling pathway. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2022, 99, 884–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.J.; He, J.C.; Wang, L.F.; Gu, Y.W.; Fan, H.G.; Tian, H.J. Neuroprotective effect of ginsenoside Rb-1 on a rat model of Alzheimer’s disease. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi 2020, 100, 2462–2466. [Google Scholar]

- She, L.; Xiong, L.; Li, L.; Zhang, J.; Sun, J.; Wu, H.; Ren, J.; Wang, W.; Zhao, X.; Liang, G. Ginsenoside Rk3 ameliorates Aβ-induced neurotoxicity in APP/PS1 model mice via AMPK signaling pathway. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 158, 114192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, Q.; Li, X.; Feng, J.; Hou, J.; Li, M.; Zhang, B. Ginsenoside Rg1 reduces β-amyloid levels by inhibiting CDK5-induced PPARγ phosphorylation in a neuron model of Alzheimer’s disease. Mol. Med. Rep. 2020, 22, 3277–3288. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Huang, L.; Kong, L.; Su, Y.; Zhou, H.; Ji, P.; Sun, R.; Wang, C.; Li, W.; Li, W. Ginsenoside Rg1 alleviates learning and memory impairments and Aβ disposition through inhibiting NLRP1 inflammasome and autophagy dysfunction in APP/PS1 mice. Mol. Med. Rep. 2023, 27, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, J.; Lu, C.; Jiang, N.; Wang, H.; Huang, H.; Chen, Y.; Li, Y.; Liu, X. Protective effect of ginsenoside Rh2 on scopolamine-induced memory deficits through regulation of cholinergic transmission, oxidative stress and the ERK-CREB-BDNF signaling pathway. Phytother. Res. 2021, 35, 337–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Feng, Y.; Fu, Q.; Li, L. Panax notoginsenoside Rb1 ameliorates Alzheimer’s disease by upregulating brain-derived neurotrophic factor and downregulating Tau protein expression. Exp. Ther. Med. 2013, 6, 826–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, N.; Tang, Y.; Keep, R.F.; Ma, X.; Xiang, J. Antioxidative effects of Panax notoginseng saponins in brain cells. Phytomedicine. 2014, 21, 1189–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, B.; Meng, X.; Wang, J.; Sun, J.; Ren, X.; Qin, M.; Sun, J.; Sun, G.; Sun, X. Notoginsenoside R1 attenuates amyloid-β-induced damage in neurons by inhibiting reactive oxygen species and modulating MAPK activation. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2014, 22, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.Z.; Cheng, W.; Shao, J.W.; Gu, Y.F.; Zhu, Y.Y.; Dong, Q.J.; Bai, S.Y.; Wang, P.; Lin, L. Notoginseng Saponin Rg1 Prevents Cognitive Impairment through Modulating APP Processing in Aβ(1–42)-injected Rats. Curr. Med. Sci. 2019, 39, 196–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.S.; Lu, Y.; Li, W.; Tao, T.; Wang, W.H.; Gao, S.; Zhou, Y.; Guo, Y.T.; Liu, C.; Zhuang, Z.; et al. Cerebroprotection by dioscin after experimental subarachnoid haemorrhage via inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome through SIRT1-dependent pathway. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2021, 178, 3648–3666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, L.; Mao, Z.; Yang, S.; Wu, G.; Chen, Y.; Yin, L.; Qi, Y.; Han, L.; Xu, L. Dioscin alleviates Alzheimer’s disease through regulating RAGE/NOX4 mediated oxidative stress and inflammation. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 152, 113248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Han, K.; Wang, C.; Sun, C.; Jia, N. Dioscin Protects against Aβ1-42 Oligomers-Induced Neurotoxicity via the Function of SIRT3 and Autophagy. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2020, 68, 717–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Gan, H.; Jin, H.; Fang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Hu, X.; Chu, L. Astragaloside IV promotes microglia/macrophages M2 polarization and enhances neurogenesis and angiogenesis through PPARγ pathway after cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury in rats. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2021, 92, 107335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, M.L.; Xie, X.H.; Ding, J.H.; Du, R.H.; Hu, G. Astragaloside IV inhibits astrocyte senescence: Implication in Parkinson’s disease. J. Neuroinflamm. 2020, 17, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, L.; Sun, J.; Miao, Z.; Chen, S.; Yang, G. Astragaloside IV attenuates neuroinflammation and ameliorates cognitive impairment in Alzheimer’s disease via inhibiting NF-κB signaling pathway. Heliyon 2023, 9, e13411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, F.; Yang, D.; Cheng, X.Y.; Yang, H.; Yang, X.H.; Liu, H.T.; Wang, R.; Zheng, P.; Yao, Y.; Li, J. Astragaloside IV Ameliorates Cognitive Impairment and Neuroinflammation in an Oligomeric Aβ Induced Alzheimer’s Disease Mouse Model via Inhibition of Microglial Activation and NADPH Oxidase Expression. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2021, 44, 1688–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Hu, J.P.; Yu, S.; Li, B.K.; Cui, Y.; Ren, L.; Zhang, L.D. Astragaloside IV, a Natural PPARγ Agonist, Reduces Aβ Production in Alzheimer’s Disease Through Inhibition of BACE1. Mol. Neurobiol. 2017, 54, 2939–2949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.P.; Liu, Y.F.; Lin, H.J.; Hsu, C.C.; Cheng, B.C.; Liu, W.P.; Lin, M.T.; Hsu, S.F.; Chang, L.S.; Lin, K.C. Beneficial Effect of Astragaloside on Alzheimer’s Disease Condition Using Cultured Primary Cortical Cells Under β-amyloid Exposure. Mol. Neurobiol. 2016, 53, 7329–7340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.T.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, C.Q.; Chang, Y.F.; Cui, M.R.; Sun, Y.; Hao, W.Q.; Yan, Y.M.; Gu, S.; Xie, Y.; et al. Combined with UPLC-Triple-TOF/MS-based plasma lipidomics and molecular pharmacology reveals the mechanisms of schisandrin against Alzheimer’s disease. Chin. Med. 2023, 18, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Wang, Q.; Guan, H.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, L. Schisandrin Inhibits NLRP1 Inflammasome-Mediated Neuronal Pyroptosis in Mouse Models of Alzheimer’s Disease. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2021, 17, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giridharan, V.V.; Thandavarayan, R.A.; Arumugam, S.; Mizuno, M.; Nawa, H.; Suzuki, K.; Ko, K.M.; Krishnamurthy, P.; Watanabe, K.; Konishi, T. Schisandrin B Ameliorates ICV-Infused Amyloid β Induced Oxidative Stress and Neuronal Dysfunction through Inhibiting RAGE/NF-κB/MAPK and Up-Regulating HSP/Beclin Expression. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0142483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Liu, X.; Zhang, L.; Yang, H.; Zhang, Q. Current Progress of Research on Neurodegenerative Diseases of Salvianolic Acid B. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2019, 2019, 3281260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.W.; Kim, D.H.; Jeon, S.J.; Park, S.J.; Kim, J.M.; Jung, J.M.; Lee, H.E.; Bae, S.G.; Oh, H.K.; Son, K.H.; et al. Neuroprotective effects of salvianolic acid B on an Aβ25-35 peptide-induced mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2013, 704, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]