Abstract

The secondary metabolites of clerodane diterpenoids have been found in several plant species from various families and in other organisms. In this review, we included articles on clerodanes and neo-clerodanes with cytotoxic or anti-inflammatory activity from 2015 to February 2023. A search was conducted in the following databases: PubMed, Google Scholar and Science Direct, using the keywords clerodanes or neo-clerodanes with cytotoxicity or anti-inflammatory activity. In this work, we present studies on these diterpenes with anti-inflammatory effects from 18 species belonging to 7 families and those with cytotoxic activity from 25 species belonging to 9 families. These plants are mostly from the Lamiaceae, Salicaceae, Menispermaceae and Euphorbiaceae families. In summary, clerodane diterpenes have activity against different cell cancer lines. Specific antiproliferative mechanisms related to the wide range of clerodanes known today have been described, since many of these compounds have been identified, some of which we barely know their properties. It is very possible that there are even more compounds than those described today, in such a way that makes it an open field to discover. Furthermore, some diterpenes presented in this review have already-known therapeutic targets, and therefore, their potential adverse effects can be predicted in some way.

1. Introduction

Diterpenes are metabolites that come from isoprene units; these compounds can be classified according to their structure [1]. One type of diterpene is clerodanes, which are found in a wide range of plant species, especially those from the Labiatae, Euphorbiaceae and Verbenaceae families [2,3]; they have also been found in bacteria, fungi and marine sponges. This type of diterpene has been extensively studied due to many of them having biological activity [1,2,3,4]. For example, clerodin has anthelminthic activity [5]; salvinorin A is an agonist of κ-opioid receptor-serotonin-2A [6] with potential for use as a treatment in neuropsychiatric disorders [7]; tinosinenosides A–C show cytotoxicity effects against HeLa [8]; and columbin has anti-inflammatory and anticancer efficacy [4].

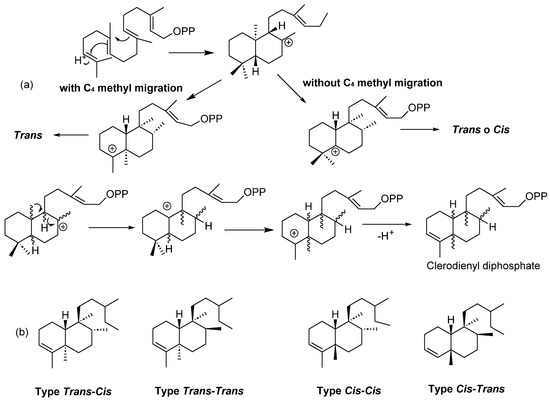

Clerodanes are secondary metabolites; when these compounds are obtained from plants, they are biosynthesized in the chloroplasts from geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate, producing a labdane-type precursor skeleton, which can be transformed to a halimane-type intermediate, and then converted to either cis- or trans- clerodanes [3] (Figure 1a).

Figure 1.

(a) Biosynthesis of clerodanes and (b) general structure of clerodanes.

Clerodanes are bicyclic diterpenoids with a fused ring of decalin structure (C1–C10) and a side chain of six carbons at C9. They are classified according to the configuration at the ring fusion and the substituents in C8 and C9 into four types: trans-cis, trans-trans, cis-cis and cis-trans (Figure 1b). About 25% have a cis ring fusion, and 75% have 5:10 trans ring fusion [9].

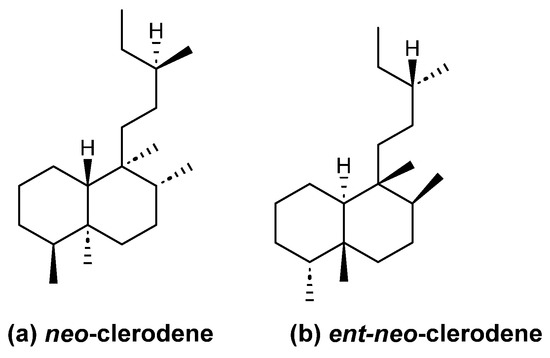

In this review, we have included clerodanes and neo-clerodanes and their enantiomers ent-neo-clerodanes (Figure 2). Additionally, carbons 12 to 16 are usually oxidized to diene, furan, lactone or hydrofurofuran, which give structural characteristics to clerodane [10].

Figure 2.

Absolute clerodane configuration.

Cancer is a global health problem and is currently one of the main causes contributing to premature death worldwide [11]. At the present time, even with the great advances in medicine in our understanding and treatment of cancer with multimodal therapies including immunotherapy, gene-targeted therapy, chemotherapy, hormonal therapy and cancer vaccines [12] against specific cell targets, there are needs that have not been covered. These include more effective therapies, with fewer adverse effects, but also therapies at a more affordable cost. Thus, there is still a need to investigate more effective and less toxic compounds. Most of the chemotherapeutic drugs (nearly 65%) that are used in current cancer treatment regimens were originally isolated from natural products or their derivatives such as plants or microorganisms [13]. For instance, paclitaxel, a diterpene isolated from Taxus brevifolia (yew trees), classified as a taxane, is used in the therapy of various types of cancers [14]. Other examples include anthracyclines derived from Streptomyces strains, among them being doxorubicin, bleomycin and many others [13]. The cytotoxic activity of several clerodanes in different cancer cell lines has been described [1].

On the other hand, inflammation is an immune response to different stimuli, such as pathogens such as viruses and bacteria, traumas and chemical irritants [15]; that is to say, inflammation is a protective response of the body against harmful stimuli. Additionally, long-term inflammation could lead to several symptoms, such as pain, fatigue, insomnia, depression and gastrointestinal problems [16]. Chronic inflammation is associated with diseases such as cancer, diabetes and arthritis [17]. The inflammatory response leads to the production of pro-inflammatory mediators, such as cytokines, serotonin, leukotrienes and histamine [18]. These mediators promote vascular permeability, leukocyte migration, blood vessel dilatation and pain. The anti-inflammatory activity of terpenes, such as carvacrol, some carotenes and diterpenes, such as clerodanes, and triterpenes, has been studied [2,19].

In this review, 158 clerodanes and 70 neo-clerodanes (1, 56, 57, 71–73, 94–132, 141–158, 184–187, 196, 197 and 207–210) with cytotoxic and anti-inflammatory activities reported from 2015 to February of 2023 were included. A total of 56 articles were found; in Table 1, the plants, family, collection place and part of the plants from which the clerodanes and neo-clerodanes were isolated are shown.

Table 1.

Part of plant, family and collection place of plants that contained clerodanes or neo-cleordanes.

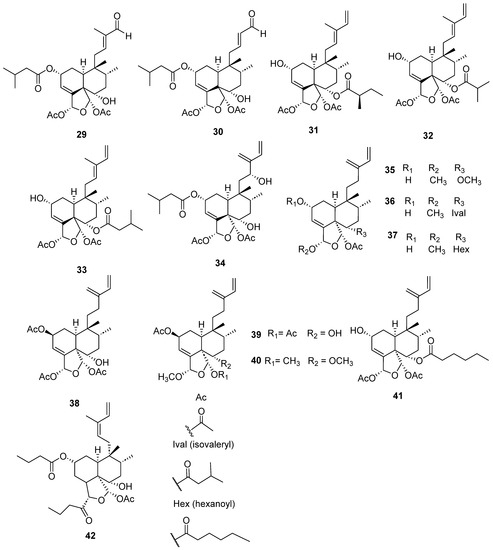

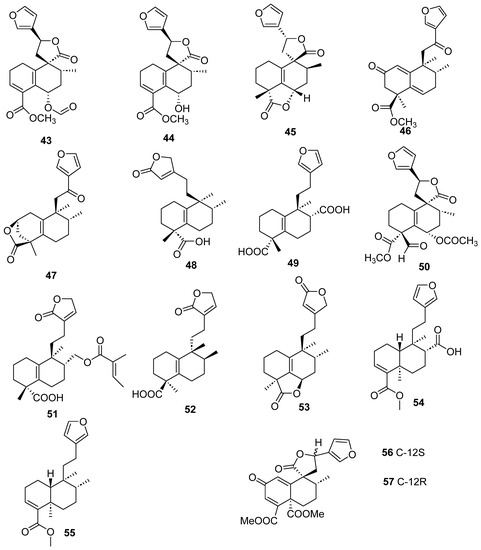

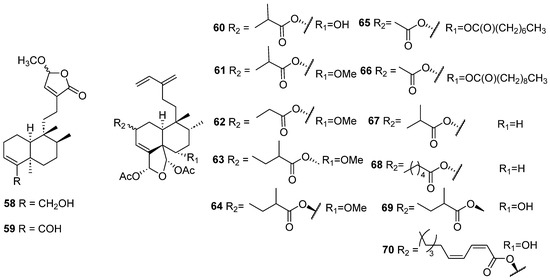

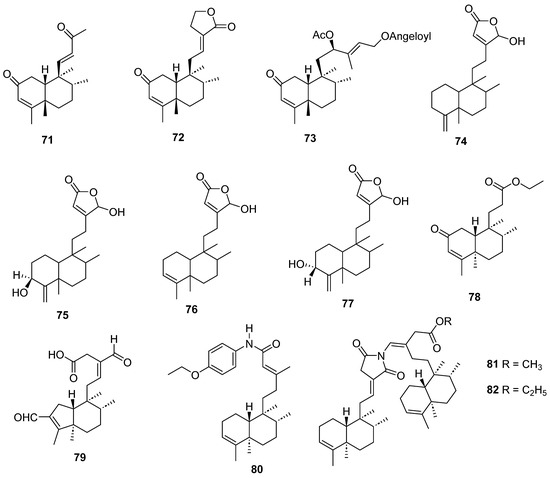

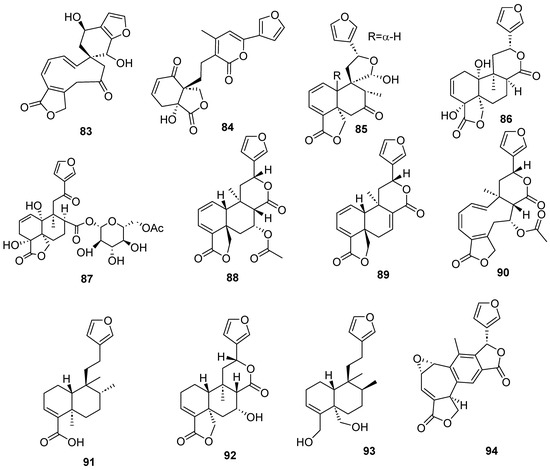

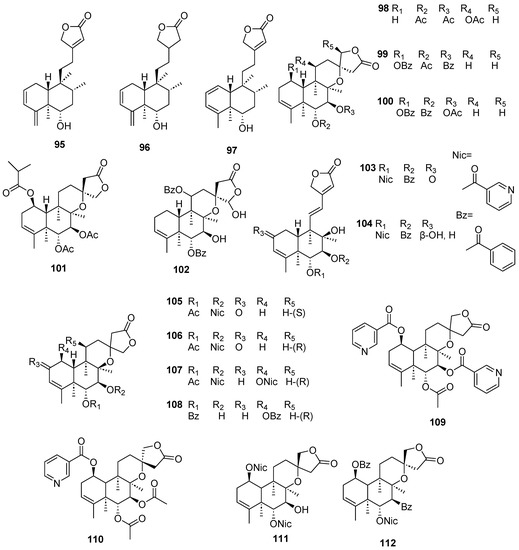

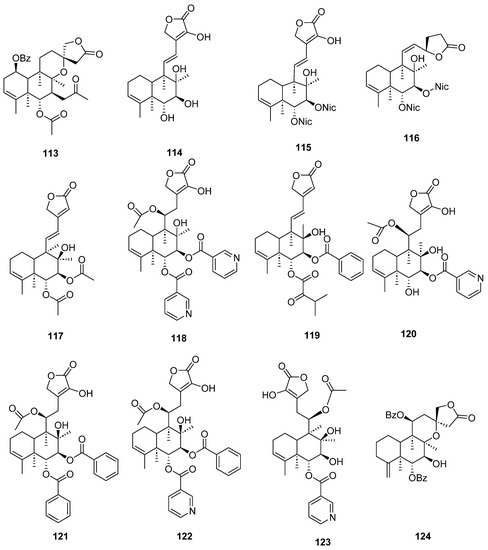

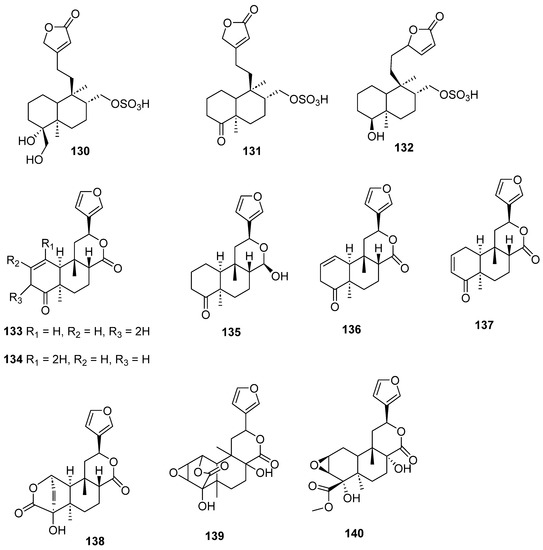

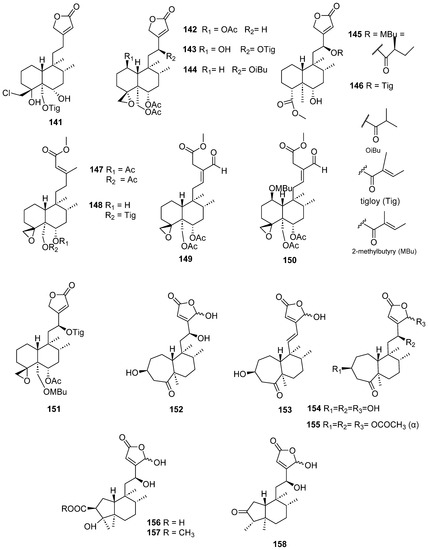

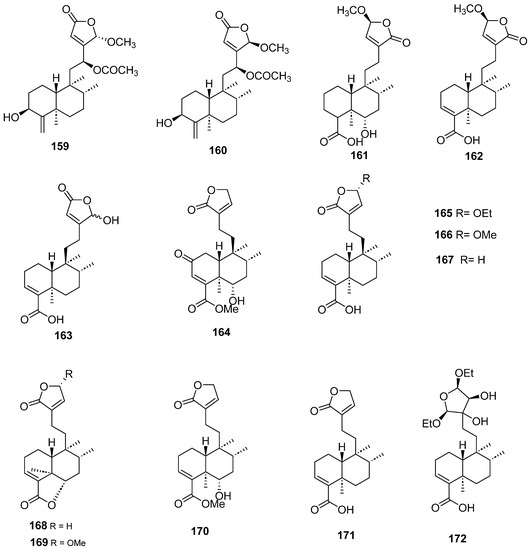

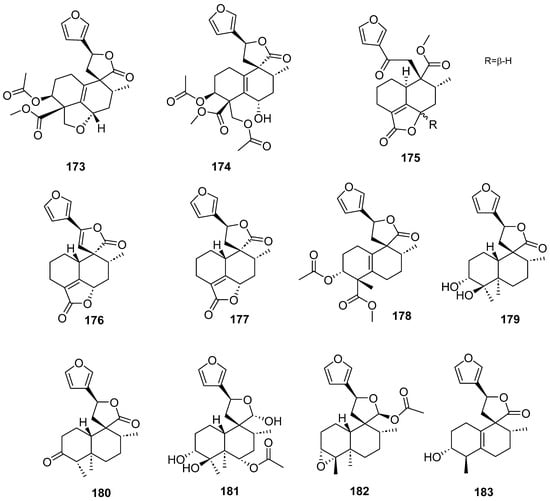

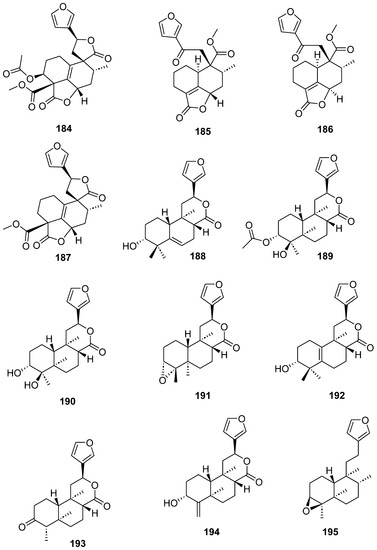

Clerodanes and neo-clerodanes with cytotoxic activity are shown in Table 2, and their structures are shown in Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10, Figure 11, Figure 12 and Figure 13.

Table 2.

Clerodane diterpenes with cytotoxic activity.

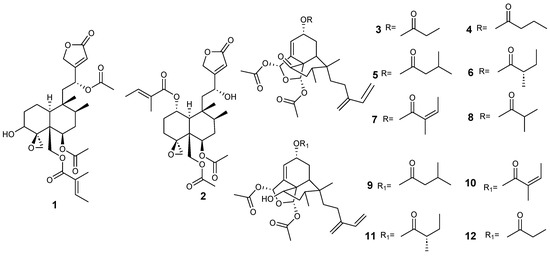

Figure 3.

Isolated compound of Ajuga decumbens and Anacolosa clarkii.

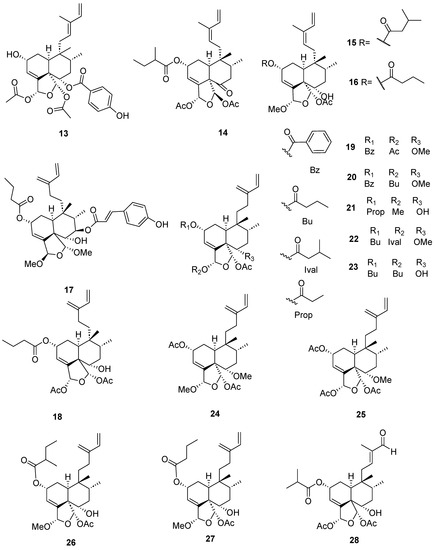

Figure 4.

Isolated compounds of different species of Casearia.

Figure 5.

Isolated compounds of different species of Casearia (continued).

Figure 6.

Isolated compounds of different species of Croton.

Figure 7.

Isolated compounds of Gottschelia schizopleura and Laetia corymbulosa.

Figure 8.

Isolated compounds of Linaria japonica and Polyalthia longifolia.

Figure 9.

Isolated compounds of different species of Salvia.

Figure 10.

Isolated compounds of Scutellaria barbata (continued).

Figure 11.

Isolated compounds of Scutellaria barbata.

Figure 12.

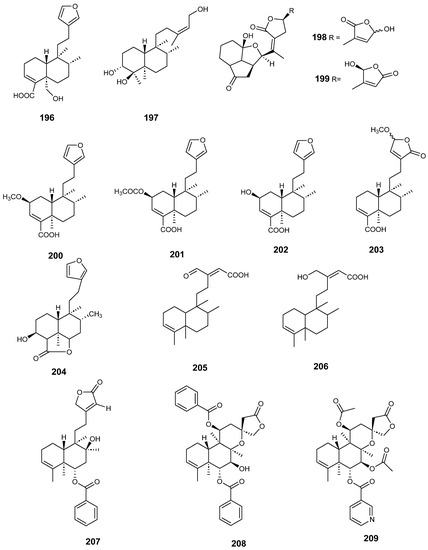

Isolated compounds of Scutellaria strigillosa.

Figure 13.

Isolated compounds of Sheareria nana, Tinospora capillipes, Tinospora cordifolia and Tinospora sagittata.

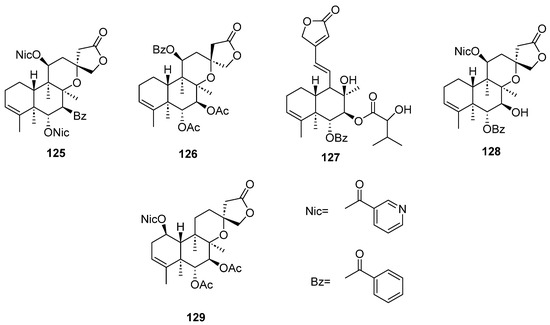

Clerodanes and neo-clerodanes’ anti-inflammatory activities are summarized in Table 3, and their structures are shown in Figure 14, Figure 15, Figure 16, Figure 17, Figure 18 and Figure 19.

Table 3.

Clerodane diterpenes with anti-inflammatory activity.

Figure 14.

Compounds of Ajuga pantantha and Callicarpa arborea with anti-inflammatory activity.

Figure 15.

Compounds of Callicarpa cathayana and Callicarpa hypoleucophylla with anti-inflammatory activity.

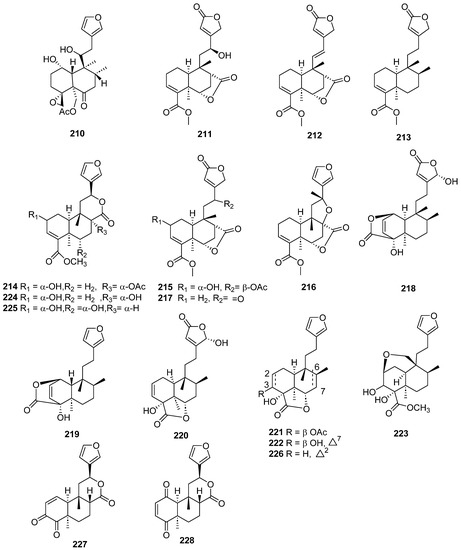

Figure 16.

Compounds of different species of Croton with anti-inflammatory activity.

Figure 17.

Compounds of different species of Croton with anti-inflammatory activity (continued).

Figure 18.

Compounds of Dodonaea viscosa, Dysoxylum lukii, Jamesoniella autumnalis, Monon membranifolium, Nepeta suavis, Polyalthia longifolia and Scutellaria barbata with anti-inflammatory activity.

Figure 19.

Compounds of different species of Teucrium fructicans, Tinospora crispa and Tinospora sagittata with anti-inflammatory activity.

2. Discussion

This review discusses research from the last 8 years on clerodane and neo-clerodane diterpenes that exhibit cytotoxic and anti-inflammatory activities. It presents studies on these diterpenes with anti-inflammatory effects from 18 species belonging to 7 families and those with cytotoxic activity from 25 species belong to 9 families. These plants mostly belong to the Lamiaceae, Salicaceae, Menispermaceae and Euphorbiaceae families. They include 228 clerodanes and neo-clerodanes, of which, 140 have cytotoxic activity, 88 have anti-inflammatory activity and crassifolin Q-U (49–53), compounds 74–77 and (-)-hardwickiic acid (91) have both activities. Compound 75 and 77 were alone in including acute toxicity, but they did not indicate LD50.

2.1. Cytotoxic Activity

All clerodanes included in this review are oxygenated; 58% of them have at least one acetate group, 47% a hydroxyl group, 49% a ring of lactone and 22% a ring of furan as substituents. Additionally, it was found that three diterpenes isolated from Sheareria nana (125–127) have -OSO3H.

We found that 82 compounds out of 140 were evaluated using the MTT assay, which is broadly used to measure the cytotoxic effects of drugs on cancer cell lines, and it is considered a quantitative cytotoxicity analysis; the assay is used more often because in itself, it is relatively straightforward and provides benefits due to the ease of its utility.

Compared to standard cancer therapies, in vitro studies have shown the cytotoxic and antiproliferative properties of different clerodane compounds. The mechanisms involved include growth inhibition, apoptosis, interference with DNA synthesis and driving DNA fragmentation in many cancer cell lines of mesenchymal, epithelial and hematopoietic origin [1,3].

Some clerodane compounds inhibit growth in cancer cell lines. Anacolosins A–F (3–8) and corymbulosins X and Y (9–10) isolated from Anacolosa clarkii exhibit cytotoxic properties in four paediatric cancer types [21]. Caseakurzin B (29) and caseakurzin J (34) from Casearia kurzii were investigated in a lung epithelial carcinoma cell line; the former arrested the cell cycle at the G2/M phase and the second at the S phase. Obtained from the same plant, corymbulosin M (25), caseamembrin B (26) and caseamembrin U (27) were also cytotoxic in three types of cancer cell lines. Of note, corymbulosin M (25) was the most potent of them and apparently even more active than etoposide, and it was shown that it affects the cell cycle at the G0/G1 stage [28]. Kurzipene D (38), also obtained from C. kurzii, has a potent antiproliferative effect compared to other kurzipenes and affects proliferation at the S stage. Further, one in vivo study used a xenograft tumor model in zebra fish embryos; this compound suppressed tumor proliferation and migration comparable to etoposide [26]. Crassifolins Q-U (49–53) from Croton crassifolius inhibited angiogenesis in HUVECs, and crassifolin U (53) had the strongest activity in this model [32]. Notably, the antitumor properties of casearins have been shown using in vivo and ex vivo methods [30]. Epoxy clerodane diterpene (139) isolated from Tinospora cordifolia had cytotoxic activity, inhibiting MCF7 growth by regulating the expression of the functional genes Rb1 and Mdm2 [55].

Several specific antiproliferative mechanisms related to the wide range of clerodanes known today have been described, since many of these compounds have been identified, some which we barely know their properties. It is very possible that there are even more compounds than those described today, in such a way that makes it an open field to discover. However, it is important to mention that clinical studies are required to demonstrate their efficacy in the therapy of the current cancer pandemic, and demonstrating their safety is also of great importance.

2.2. Anti-Inflammatory Activity

A total of 45% of the clerodanes with anti-inflammatory activity have at least one hydroxyl, 69% compounds contain a ring of lactones, 50% a ring of furans and 26% an acetate group as substituents.

We found that 63 compounds reported to have anti-inflammatory activity were evaluated for nitric oxide inhibition with the Griess assay on RAW264.7 macrophages or BV-2-cell-stimulated-LPS, and the clerodanes 157, 158, 185, 186 and 207 showed the best activity in this test with IC50 values of less than 2 µM. In this review, we found that in vivo studies have only been performed for hautriwaic acid (196) and nepetolide (204).

The anti-inflammatory activity of clerodane diterpenoids mediated by different mechanisms has been demonstrated in in vitro and in vivo animal models. Compounds 154, 155, 157 and 158 from Callicarpa arborea showed potent inhibitory effects against the NLRP3 inflammasome by inhibiting Casp-1 activation and IL-1β in reticulum cell sarcoma cells [59].

Clerodane 74–77 and 206 from extracts of Polyalthia longifolia seeds inhibit inflammation, blocking the synthesis of prostaglandins and leukotrienes through highly selective binding to cyclooxygenases (COX) 1 and 2 and 5-lipooxygenase (5-LOX), respectively, compared to the nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs diclofenac and indomethacin [71]. In 2008, clerodane 206 was associated with the suppression of neutrophil respiratory burst and degranulation, and it is thought that it is mediated at least in part by the inhibition of calcium mobilization, AKT (protein kinase B) and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways [77]. Hautriwaic acid (196) from Dodonaea viscosa leaves, used for rheumatism, exhibited anti-inflammatory activity in a mouse ear edema model [66]. Clerodane compounds 164–175 from Callicarpa hypoleucophylla suppress superoxide anion generation and elastase release, inhibiting the function of human neutrophils [61]. Trans-crotonin inhibits dextran- and histamine-induced oedema [2].

Compounds derived from the Scutellaria genus have strong interactions with inducible nitric oxide synthase, and because of that, they inhibit nitric oxide production [72]. Five clerodane diterpenoids from Croton crassifolius roots, named crassifolins Q–U (49–53), reduced the levels of IL-6 and TNF-α in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated RAW 264.7 cells [32]. Compounds 211–213 from Tinospora crispa diminish the production of pro-inflammatory mediators (IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, iNOs, CCL12 and COX-2) [74].

3. Conclusions

In summary, clerodane diterpenes have activity against different cell cancer lines. Furthermore, some of the diterpenes presented in this review have already-known therapeutic targets, and therefore, their potential adverse effects can be predicted in some way, but the discovery of new compounds and new mechanisms remains to be seen. Anyway, the study of possible new therapies for inflammation continues to be important in order to expand the options for the treatment of inflammatory diseases that afflict the world.

More than 50% of clerodanes included in this review with cytotoxic activity contain acetate groups; on the other hand, 69% of the compounds with anti-inflammatory effects have a ring of lactone.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.P.-R. and S.P.-G.; methodology, R.M.M.-C., L.H.-V., A.M., L.S.-P., S.P.-G. and J.P.-R.; validation R.M.M.-C., L.H.-V., A.M., L.S.-P., S.P.-G. and J.P.-R.; formal analysis, R.M.M.-C., L.H.-V., A.M., L.S.-P., S.P.-G. and J.P.-R.; data curation, R.M.M.-C., L.H.-V., A.M., L.S.-P., S.P.-G. and J.P.-R.; writing—original draft preparation, S.P.-G. and A.M.; writing—review and editing, R.M.M.-C., L.H.-V., A.M., L.S.-P., S.P.-G. and J.P.-R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Acquaviva, R.; Malfa, G.A.; Loizzo, M.R.; Xiao, J.; Bianchi, S.; Tundis, R. Advances on Natural Abietane, Labdane and Clerodane Diterpenes as Anti-Cancer Agents: Sources and Mechanisms of Action. Molecules 2022, 27, 4791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, Z.; Cao, J.; Zhang, Q.; Lin, L. The Drug Likeness Analysis of Anti-Inflammatory Clerodane Diterpenoids. Chin. Med. 2020, 15, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, R.; Morris-Natschke, S.L.; Lee, K.-H. Clerodane Diterpenes: Sources, Structures, and Biological Activities. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2016, 33, 1166–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- dos Lima, J.; Marinho, E.M.; Alencar de Menezes, J.E.; Mendes, F.R.S.; da Silva Antonio, W.; Maria, K.A.F.; Emmanuel, S.M.; Marinho, M.M.; Bandeira, P.N.; dos Santos, H.S. Biological Properties of Clerodane-Type Diterpenes. J. Anal. Pharm. Res. 2022, 11, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Shukla, R.; Chaudhary, A. Evaluation of Antiulcerogenic Activity of Clerodendron Infortunatum Extract on Albino Rat Gastric Ulceration. J. Drug Deliv. Ther. 2019, 9, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranganathan, M.; Schnakenberg, A.; Skosnik, P.D.; Cohen, B.M.; Pittman, B.; Sewell, R.A.; D’Souza, D.C. Dose-Related Behavioral, Subjective, Endocrine, and Psychophysiological Effects of the κ Opioid Agonist Salvinorin A in Humans. Biol. Psychiatry 2012, 72, 871–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cichon, J.; Liu, R.; Le, H.V. Therapeutic Potential of Salvinorin A and Its Analogues in Various Neurological Disorders. Transl. Perioper. Pain Med. 2022, 9, 452–457. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, H.; Zhang, G.-J.; Liu, Y.-F.; Wang, H.-S.; Liang, D. Clerodane Diterpenoid Glucosides from the Stems of Tinospora sinensis. J. Nat. Prod. 2017, 80, 975–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokoroyama, T. Synthesis of Clerodane Diterpenoids and Related Compounds—Stereoselective Construction of the Decalin Skeleton with Multiple Contiguous Stereogenic Centers. Synthesis 2000, 2000, 611–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagiwara, H. Total Syntheses of Clerodane Diterpenoids—A Review. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2019, 14, 1934578X19843613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soerjomataram, I.; Bray, F. Planning for Tomorrow: Global Cancer Incidence and the Role of Prevention 2020–2070. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 18, 663–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsimberidou, A.M.; Fountzilas, E.; Nikanjam, M.; Kurzrock, R. Review of Precision Cancer Medicine: Evolution of the Treatment Paradigm. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2020, 86, 102019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; He, Y.; Jian, M.; Fu, X.; Cheng, Y.; He, Y.; Fang, J.; Li, L.; Zhang, D. Breaking the Bottleneck in Anticancer Drug Development: Efficient Utilization of Synthetic Biology. Molecules 2022, 27, 7480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallego-Jara, J.; Lozano-Terol, G.; Sola-Martínez, R.A.; Cánovas-Díaz, M.; de Diego Puente, T. A Compressive Review about Taxol®: History and Future Challenges. Molecules 2020, 25, 5986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Xue, M.; Geng, Z.; Chen, P. The Suppressive Effects of Bursopentine (BP5) on Oxidative Stress and NF-ĸB Activation in Lipopolysaccharide-Activated Murine Peritoneal Macrophages. Cell Physiol. Biochem. 2012, 29, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pahwa, R.; Goyal, A.; Jialal, I. Chronic Inflammation; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Nathan, C.; Ding, A. Nonresolving Inflammation. Cell 2010, 140, 871–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuller, B. Role of PGE-2 and Other Inflammatory Mediators in Skin Aging and Their Inhibition by Topical Natural Anti-Inflammatories. Cosmetics 2019, 6, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araruna, M.E.; Serafim, C.; Alves Júnior, E.; Hiruma-Lima, C.; Diniz, M.; Batista, L. Intestinal Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Terpenes in Experimental Models (2010–2020): A Review. Molecules 2020, 25, 5430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olatunde, O.Z.; Yong, J.; Lu, C. New Neo-Clerodane Diterpenoids Isolated from Ajuga decumbens Thunb., Planted at Pingtan Island of Fujian Province with the Potent Anticancer Activity. Anti-Cancer Agents Med. Chem. 2023, 23, 237–244. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, S.; Risinger, A.L.; Petersen, C.L.; Grkovic, T.; O’Keefe, B.R.; Mooberry, S.L.; Cichewicz, R.H. Anacolosins A-F and Corymbulosins X and Y, Clerodane Diterpenes from Anacolosa clarkii Exhibiting Cytotoxicity toward Pediatric Cancer Cell Lines. J. Nat. Prod. 2019, 82, 928–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vila-Luna, M.L.; Moo-Puc, R.E.; Torres-Tapia, L.W.; Peraza-Sánchez, S.R. Cytotoxic Activity of Casearborin c Isolated from Casearia corymbosa. J. Mex. Chem Soc. 2018, 62, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meesakul, P.; Ritthiwigrom, T.; Cheenpracha, S.; Sripisut, T.; Maneerat, W.; Machan, T.; Laphookhieo, S. A New Cytotoxic Clerodane Diterpene from Casearia graveolens Twigs. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2016, 11, 13–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuanyai, T.; Chailap, B.; Buakeaw, A.; Puthong, S. Cytotoxicity of Clerodane Diterpenoids from Fresh Ripe Fruits of Casearia grewiifolia. J. Sci. Technol. 2017, 39, 517–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.T.T.; Truong, N.B.; Doan, H.T.M.; Litaudon, M.; Retailleau, P.; Do, T.T.; Nguyen, H.V.; Chau, M.V.; Pham, C.V. Cytotoxic Clerodane Diterpenoids from the Leaves of Casearia grewiifolia. J. Nat. Prod. 2015, 78, 2726–2730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Yang, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Li, Y.; Du, Q.; Jin, D.-Q.; Cui, J.; Lall, N.; et al. Diterpenoids from the Leaves of Casearia kurzii Showing Cytotoxic Activities. Bioorg. Chem. 2020, 98, 103741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.-T.; Wang, X.-L.; Wang, T.; Zhang, J.-S.; Huang, Z.-Q.; Shen, T.; Lou, H.-X.; Ren, D.-M.; Wang, X.-N. Dolabellane and Clerodane Diterpenoids from the Twigs and Leaves of Casearia kurzii. J. Nat. Prod. 2020, 83, 2817–2830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuo, Y.; Zhang, C.; Yang, X.; Liu, F.; Zhang, Q.; Li, A.; Ma, J.; Lee, D.; Ohizumi, Y.; Guo, Y. Clerodane Diterpenoids from Casearia kurzii and Their Cytotoxic Activities. J. Nat. Med. 2019, 73, 826–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Zhang, Q.; Yang, X.; Xi, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, H.; Zhang, J.; Tuerhong, M.; Jin, D.-Q.; Lee, D.; et al. Cytotoxic Diterpenoids as Potential Anticancer Agents from the Twigs of Casearia kurzii. Bioorg. Chem. 2019, 89, 102995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, P.M.P.; Bezerra, D.P.; do Nascimento Silva, J.; da Costa, M.P.; de Oliveira Ferreira, J.R.; Alencar, N.M.N.; de Figueiredo, I.S.T.; Cavalheiro, A.J.; Machado, C.M.L.; Chammas, R.; et al. Preclinical Anticancer Effectiveness of a Fraction from Casearia Sylvestris and Its Component Casearin X: In Vivo and Ex Vivo Methods and Microscopy Examinations. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2016, 186, 270–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, M.-F.; Pan, Y.-H.; Hu, R.; Yuan, F.-Y.; Huang, D.; Tang, G.-H.; Li, W.; Yin, S. Highly Modified Nor-Clerodane Diterpenoids from Croton yanhuii. Fitoterapia 2021, 153, 104979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Sun, X.; Yin, W.; Zhan, Z.; Tang, Q.; Wang, W.; Zhuo, X.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, H.; Li, Y.; et al. Crassifolins Q−W: Clerodane Diterpenoids From Croton crassifolius With Anti-Inflammatory and Anti-Angiogenesis Activities. Front. Chem. 2021, 9, 733350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.-L.; Yao, G.-D.; Wang, Y.-X.; Gao, P.-Y.; Wang, D.; Li, L.-Z.; Lin, B.; Huang, X.-X.; Song, S.-J. Cytotoxic Clerodane Diterpenoids from Croton crassifolius. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2017, 27, 1237–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, M.; Cao, D.; Gao, Y.; Li, S.; Zhu, J.; Yang, B.; Zhou, L.; Zhou, Y.; Jin, J.; Zhao, Z. New Clerodane Diterpenoids from Croton crassifolius. Fitoterapia 2016, 108, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vendruscolo, I.; Venturella, S.R.T.; Bressiani, P.A.; Marco, I.G.; Novello, C.R.; Almeida, I.V.; Vicentini, V.E.P.; Mello, J.C.P.; Düsman, E. Cytotoxicity of Extracts and Compounds Isolated from Croton echioides in Animal Tumor Cell (HTC). Braz. J. Biol. 2022, 82, e264356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guetchueng, S.T.; Nahar, L.; Ritchie, K.J.; Ismail, F.M.D.; Evans, A.R.; Sarker, S.D. Ent-Clerodane Diterpenes from the Bark of Croton oligandrus Pierre Ex Hutch. and Assessment of Their Cytotoxicity against Human Cancer Cell Lines. Molecules 2018, 23, 410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, S.-Y.; Kamada, T.; Suleiman, M.; Vairappan, C.S. Two New Clerodane-Type Diterpenoids from Bornean Liverwort Gottschelia schizopleura and Their Cytotoxic Activity. Nat. Prod. Res. 2018, 32, 1832–1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aimaiti, S.; Suzuki, A.; Saito, Y.; Fukuyoshi, S.; Goto, M.; Miyake, K.; Newman, D.J.; O’Keefe, B.R.; Lee, K.-H.; Nakagawa-Goto, K. Corymbulosins I–W, Cytotoxic Clerodane Diterpenes from the Bark of Laetia corymbulosa. J. Org. Chem. 2018, 83, 951–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Widyowati, R.; Sugimoto, S.; Yamano, Y.; Sukardiman; Otsuka, H.; Matsunami, K. New Cis-Ent-Clerodanes from Linaria japonica. Phytochem. Lett. 2015, 14, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatipamula, V.B.; Thonangi, C.V.; Dakal, T.C.; Vedula, G.S.; Dhabhai, B.; Polimati, H.; Akula, A.; Nguyen, H.T. Potential Anti-Hepatocellular Carcinoma Properties and Mechanisms of Action of Clerodane Diterpenes Isolated from Polyalthia longifolia Seeds. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 9267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.-X.; Fu, Y.-H.; Chen, G.-Y.; Song, X.-P.; Han, C.-R.; Li, X.-B.; Song, X.-M.; Wu, A.-Z.; Chen, S.-C. New Clerodane Diterpenoids from the Roots of Polyalthia laui. Fitoterapia 2016, 111, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bautista, E.; Fragoso-Serrano, M.; Ortiz-Pastrana, N.; Toscano, R.A.; Ortega, A. Structural Elucidation and Evaluation of Multidrug-Resistance Modulatory Capability of Amarissinins A–C, Diterpenes Derived from Salvia amarissima. Fitoterapia 2016, 114, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fragoso-Serrano, M.; Ortiz-Pastrana, N.; Luna-Cruz, N.; Toscano, R.A.; Alpuche-Solís, A.G.; Ortega, A.; Bautista, E. Amarisolide F, an Acylated Diterpenoid Glucoside and Related Terpenoids from Salvia amarissima. J. Nat. Prod. 2019, 82, 631–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bautista, E.; Fragoso-Serrano, M.; Toscano, R.A.; García-Peña, M.d.R.; Ortega, A. Teotihuacanin, a Diterpene with an Unusual Spiro-10/6 System from Salvia amarissima with Potent Modulatory Activity of Multidrug Resistance in Cancer Cells. Org. Lett. 2015, 17, 3280–3282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bustos-Brito, C.; Pérez-Juanchi, D.; Rivera-Chávez, J.; Hernández-Herrera, A.D.; Bedolla-García, B.Y.; Zamudio, S.; Ramírez-Apan, T.; Quijano, L.; Esquivel, B. Clerodane and 5 10-Seco-Clerodane-Type Diterpenoids from Salvia involucrata. J. Mol. Struct. 2021, 1237, 130367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.-J.; Su, J.; Shi, X.; Wu, X.-D.; Chen, X.-Q.; He, J.; Shao, L.-D.; Li, X.-N.; Peng, L.-Y.; Li, R.-T.; et al. Neo-Clerodanes from the Aerial Parts of Salvia leucantha. Tetrahedron 2016, 72, 5507–5514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Chen, Y.; Hu, P.; Ji, J.; Li, X.; Chen, J. Neoclerodane Diterpenoids from Scutellaria barbata with Cytotoxic Activities. Nat. Prod. Res. 2020, 34, 1345–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.-C.; Hu, J.-H.; Li, B.-L.; Liu, H.; Wang, J.-Y.; Sun, L.-X. Six New Neo-Clerodane Diterpenoids from Aerial Parts of Scutellaria barbata and Their Cytotoxic Activities. Planta Med. 2018, 84, 1292–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Q.-Q.; Song, W.-B.; Wang, W.-Q.; Xuan, L.-J. Scubatines A–F, New Cytotoxic Neo-Clerodane Diterpenoids from Scutellaria barbata D. Don. Fitoterapia 2017, 119, 40–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Ma, C.; Chen, Y.; Li, X.; Chen, J. Cytotoxic Neo-Clerodane Diterpenoids from Scutellaria barbata D.Don. Chem. Biodivers. 2019, 16, e1800499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, S.-J.; Xiao, K.; Zhang, L.; Han, Q.-T. New Neo-Clerodane Diterpenoids from Scutellaria strigillosa with Cytotoxic Activities. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 2016, 18, 456–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, S.-J.; Zhang, L.; Xiao, K.; Han, Q.-T. New Cytotoxic Neo-Clerodane Diterpenoids from Scutellaria strigillosa. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2016, 26, 1750–1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Z.; Shen, J.; Zhang, F.; Liang, J.; Xia, Z. Sulfated Neo-Clerodane Diterpenoids and Triterpenoid Saponins from Sheareria nana S. Moore. Fitoterapia 2018, 124, 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Zhang, P.-L.; Zhou, M.-X.; Shen, T.; Zou, Y.-X.; Lou, H.-X.; Wang, X.-N. New Nor-Clerodane-Type Furanoditerpenoids from the Rhizomes of Tinospora capillipes. Phytochem. Lett. 2016, 15, 225–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subash-Babu, P.; Alshammari, G.M.; Ignacimuthu, S.; Alshatwi, A.A. Epoxy Clerodane Diterpene Inhibits MCF-7 Human Breast Cancer Cell Growth by Regulating the Expression of the Functional Apoptotic Genes Cdkn2A, Rb1, Mdm2 and P53. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2017, 87, 388–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, N.; Wang, A.; Li, D.; Wang, K.; Lin, B.; Li, Z.; Hua, H. Cytotoxic Clerodane Furanoditerpenoids from the Root of Tinospora sagittata. Phytochem. Lett. 2015, 12, 173–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Song, Z.; Wang, H.; Yang, X.; Joubert, E.; Zhang, J.; Li, S.; Tuerhong, M.; Abudukeremu, M.; Jin, J.; et al. Diterpenoids as Potential Anti-Inflammatory Agents from Ajuga pantantha. Bioorg. Chem. 2020, 101, 103966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, B.; Yang, X.; Liu, W.; An, L.; Zhang, X.; Tuerhong, M.; Du, Q.; Wang, C.; Abudukeremu, M.; Xu, J.; et al. Anti-Inflammatory Neo-Clerodane Diterpenoids from Ajuga pantantha. J. Nat. Prod. 2020, 83, 894–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, D.-B.; Zhang, X.-J.; Bi, D.-W.; Gao, J.-B.; Yang, Y.; Li, X.-L.; Lin, J.; Li, X.-N.; Zhang, R.-H.; Xiao, W.-L. Callicarpins, Two Classes of Rearranged Ent-Clerodane Diterpenoids from Callicarpa Plants Blocking NLRP3 Inflammasome-Induced Pyroptosis. J. Nat. Prod. 2020, 83, 2191–2199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Lin, J.; Wang, Q.; Shang, K.; Pu, D.-B.; Zhang, R.-H.; Li, X.-L.; Dai, X.-C.; Zhang, X.-J.; Xiao, W.-L. Clerodane Diterpenoids with Potential Anti-Inflammatory Activity from the Leaves and Twigs of Callicarpa cathayana. Chin. J. Nat. Med. 2019, 17, 953–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-C.; Lin, J.-J.; Chen, S.-R.; Hwang, T.-L.; Fang, S.-Y.; Korinek, M.; Chen, C.-Y.; Lin, Y.-S.; Wu, T.-Y.; Yen, M.-H.; et al. Clerodane Diterpenoids from Callicarpa hypoleucophylla and Their Anti-Inflammatory Activity. Molecules 2020, 25, 2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, G.-H.; Xue, J.-J.; Liang, W.-L.; Yang, S.-J. Three New Bioactive Diterpenoids from the Roots of Croton crassifolius. Nat. Prod. Res. 2021, 35, 1421–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Queiroz, S.A.S.; Pinto, M.E.F.; Bobey, A.F.; Russo, H.M.; Batista, A.N.L.; Batista, J.M.; Codo, A.C.; Medeiros, A.I.; Bolzani, V.S. Diterpenoids with Inhibitory Activity of Nitrite Production from Croton floribundus. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2020, 249, 112320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Zhang, D.-B.; Li, J.-T.; He, F.-J.; Zhu, H.-L.; Li, N.; Xiao, X.-C.; Ren, L.; Zheng, W. Bioactive Terpenoids from Croton laui. Nat. Prod. Res. 2021, 35, 2849–2857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somteds, A.; Tantapakul, C.; Kanokmedhakul, K.; Laphookhieo, S.; Phukhatmuen, P.; Kanokmedhakul, S. Inhibition of Nitric Oxide Production by Clerodane Diterpenoids from Leaves and Stems of Croton poomae Esser. Nat. Prod. Res. 2021, 35, 2722–2729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salinas-Sánchez, D.O.; Zamilpa, A.; Pérez, S.; Herrera-Ruiz, M.; Tortoriello, J.; González-Cortazar, M.; Jiménez-Ferrer, E. Effect of Hautriwaic Acid Isolated from Dodonaea viscosa in a Model of Kaolin/Carrageenan-Induced Monoarthritis. Planta Med. 2015, 81, 1240–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.-Z.; Zhang, Y.-M.; Lin, Y.; Wang, F.; Zhang, G.-L. Three New Diterpenes from Dysoxylum lukii and Their NO Production Inhibitory Activity. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 2020, 22, 531–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhu, R.; Zhang, J.; Wu, X.; Shen, T.; Zhou, J.; Qiao, Y.; Gao, Y.; Lou, H. Clerodane Diterpenoids from the Chinese Liverwort Jamesoniella autumnalis and Their Anti-Inflammatory Activity. Phytochemistry 2018, 154, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polbuppha, I.; Suthiphasilp, V.; Maneerat, T.; Charoensup, R.; Limtharakul, T.; Cheenpracha, S.; Pyne, S.G.; Laphookhieo, S. Nitric Oxide Production Inhibitory Activity of Clerodane Diterpenes from Monoon membranifolium. Nat. Prod. Res. 2022, 36, 2513–2517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ur Rehman, T.; Khan, A.; Abbas, A.; Hussain, J.; Khan, F.U.; Stieglitz, K.; Ali, S. Investigation of Nepetolide as a Novel Lead Compound: Antioxidant, Antimicrobial, Cytotoxic, Anticancer, Anti-Inflammatory, Analgesic Activities and Molecular Docking Evaluation. Saudi Pharm. J. 2018, 26, 422–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.T.; Vu, T.-Y.; Chandi, V.; Polimati, H.; Tatipamula, V.B. Dual COX and 5-LOX Inhibition by Clerodane Diterpenes from Seeds of Polyalthia longifolia (Sonn.) Thwaites. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 15965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.-S.; Yan, W.; Bai, L.-H.; Wang, K.; Chen, X.-Q. Neo-Clerodane Diterpenoids from the Aerial Parts of Scutellaria barbata with Anti-Inflammatory Activity. Chem. Biodivers. 2021, 18, e2100693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, H.-W.; Luo, J.-G.; Zhu, M.-D.; Zhao, H.-J.; Kong, L.-Y. Neo-Clerodane Diterpenoids from the Aerial Parts of Teucrium fruticans Cultivated in China. Phytochemistry 2015, 119, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- You, J.-Q.; Liu, Y.-N.; Zhou, J.-S.; Sun, X.-Y.; Lei, C.; Mu, Q.; Li, J.-Y.; Hou, A.-J. Cis-Clerodane Diterpenoids with Structural Diversity and Anti-Inflammatory Activity from Tinospora crispa. Chin. J. Chem. 2022, 40, 2882–2892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.-L.; Deng, L.; Song, J.-Q.; Zhu, Y.; Yuan, R.-W.; Fan, X.-Z.; Zhou, H.; Huang, Y.-S.; Zhang, L.-J.; Liao, H.-B. Clerodane Diterpenoids with Anti-Inflammatory and Synergistic Antibacterial Activities from Tinospora crispa. Org. Chem. Front. 2022, 9, 6945–6957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Ma, H.; Hu, S.; Xu, H.; Yang, B.; Yang, Q.; Xue, Y.; Cheng, L.; Jiang, J.; Zhang, J.; et al. Clerodane-Type Diterpenoids from Tuberous Roots of Tinospora sagittata (Oliv.) Gagnep. Fitoterapia 2016, 110, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.-L.; Chang, F.-R.; Chen, J.-S.; Wang, H.-P.; Wu, Y.-H.; Wang, C.-C.; Wu, Y.-C.; Hwang, T.-L. Inhibitory Effects of 16-Hydroxycleroda-3,13(14)E-Dien-15-Oic Acid on Superoxide Anion and Elastase Release in Human Neutrophils through Multiple Mechanisms. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2008, 586, 332–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).