Occurrence of Mycosporine-like Amino Acids (MAAs) from the Bloom-Forming Cyanobacteria Aphanizomenon Strains

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Aphanizomenon Strains and Culture Conditions

2.2. DNA Extraction and PCR Reaction

2.3. Sequence Alignment and Phylogenetic Analysis

2.4. MAA Extraction and HPLC Analysis

2.5. UPLC-MS-MS Analysis

2.6. Collection of MAA Standards

3. Results

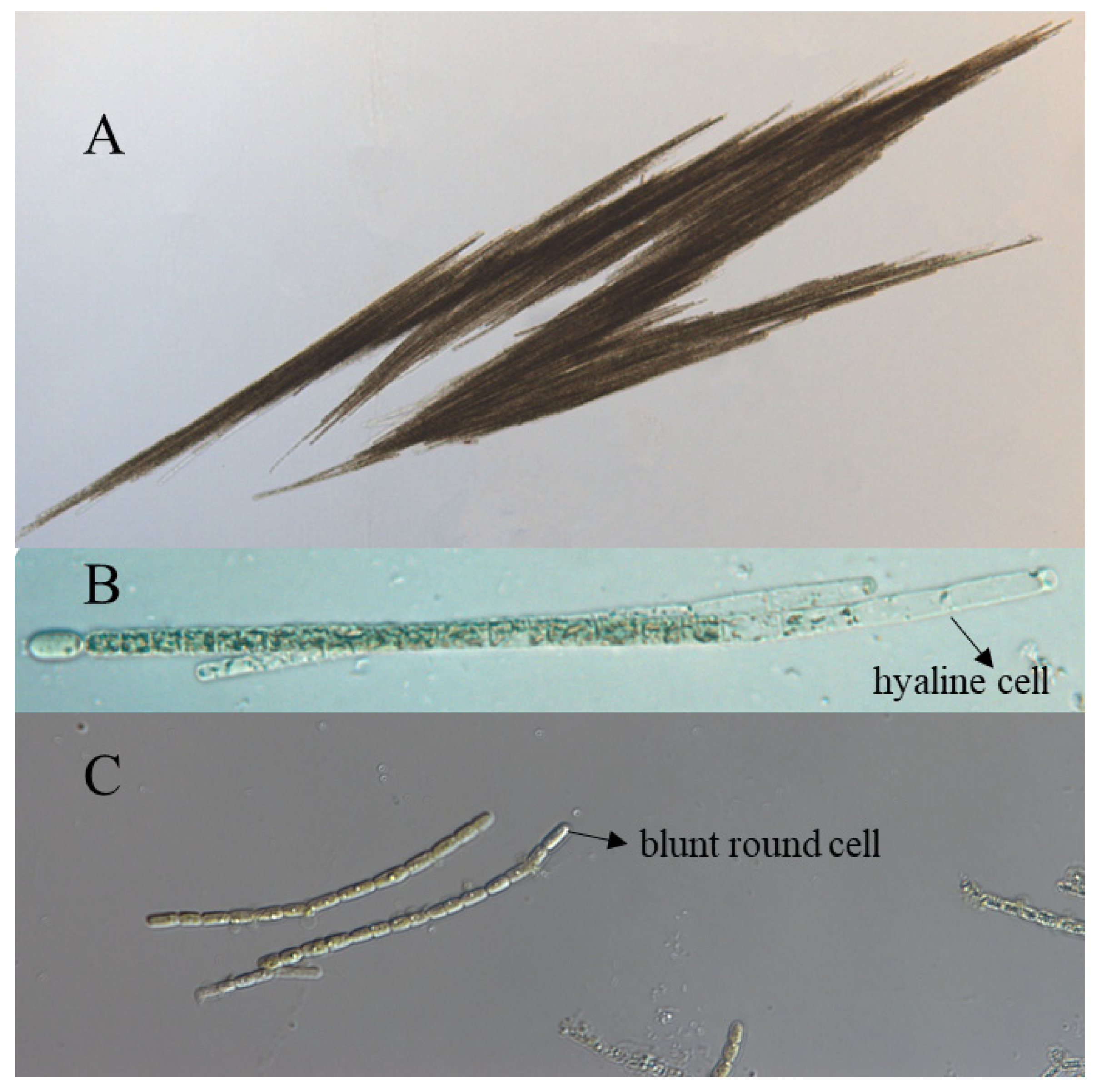

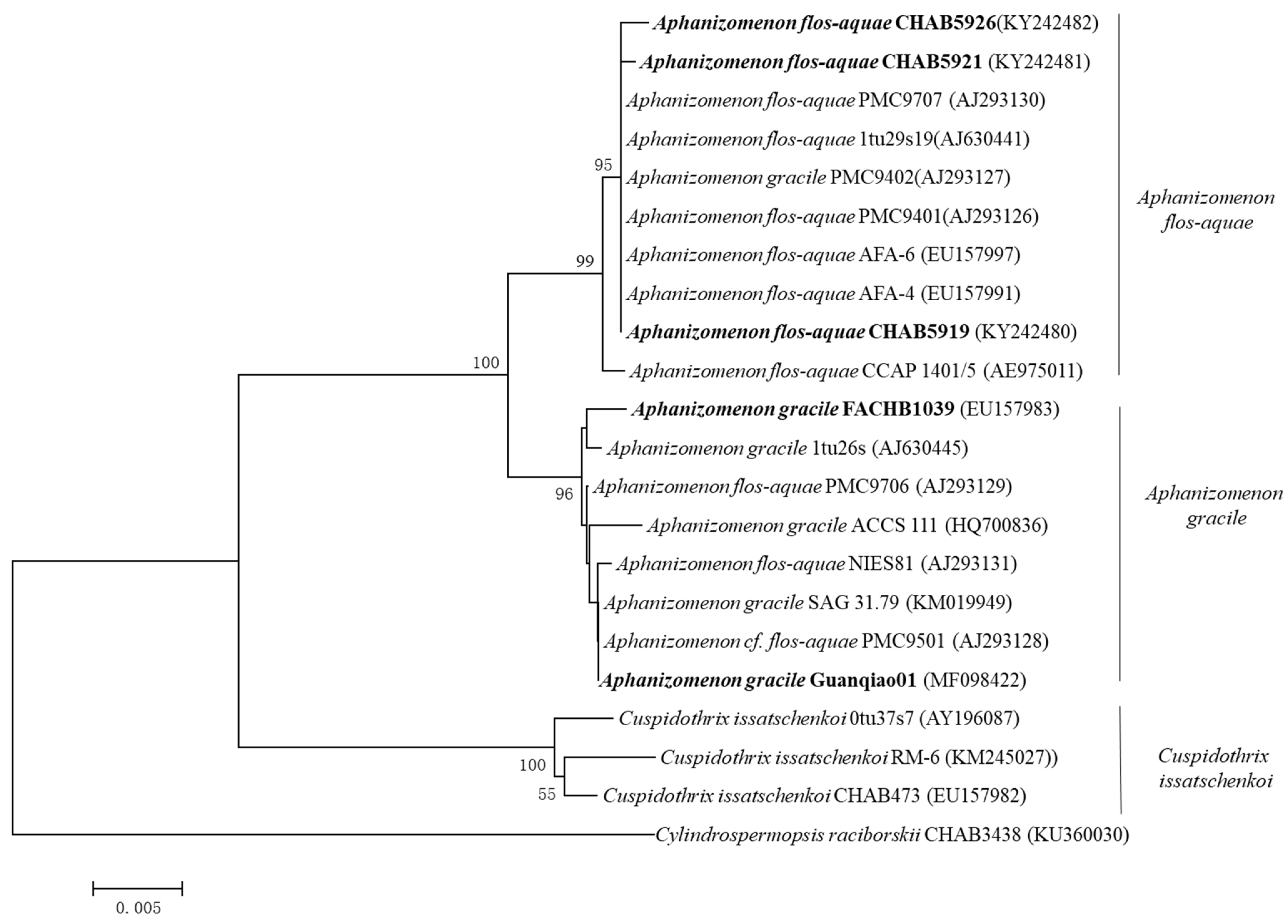

3.1. Morphological and Phylogenetic Classification of Aphanizomenon Strains

3.2. Discovery of a UV Absorption Substance in the Aphanizomenon Strains

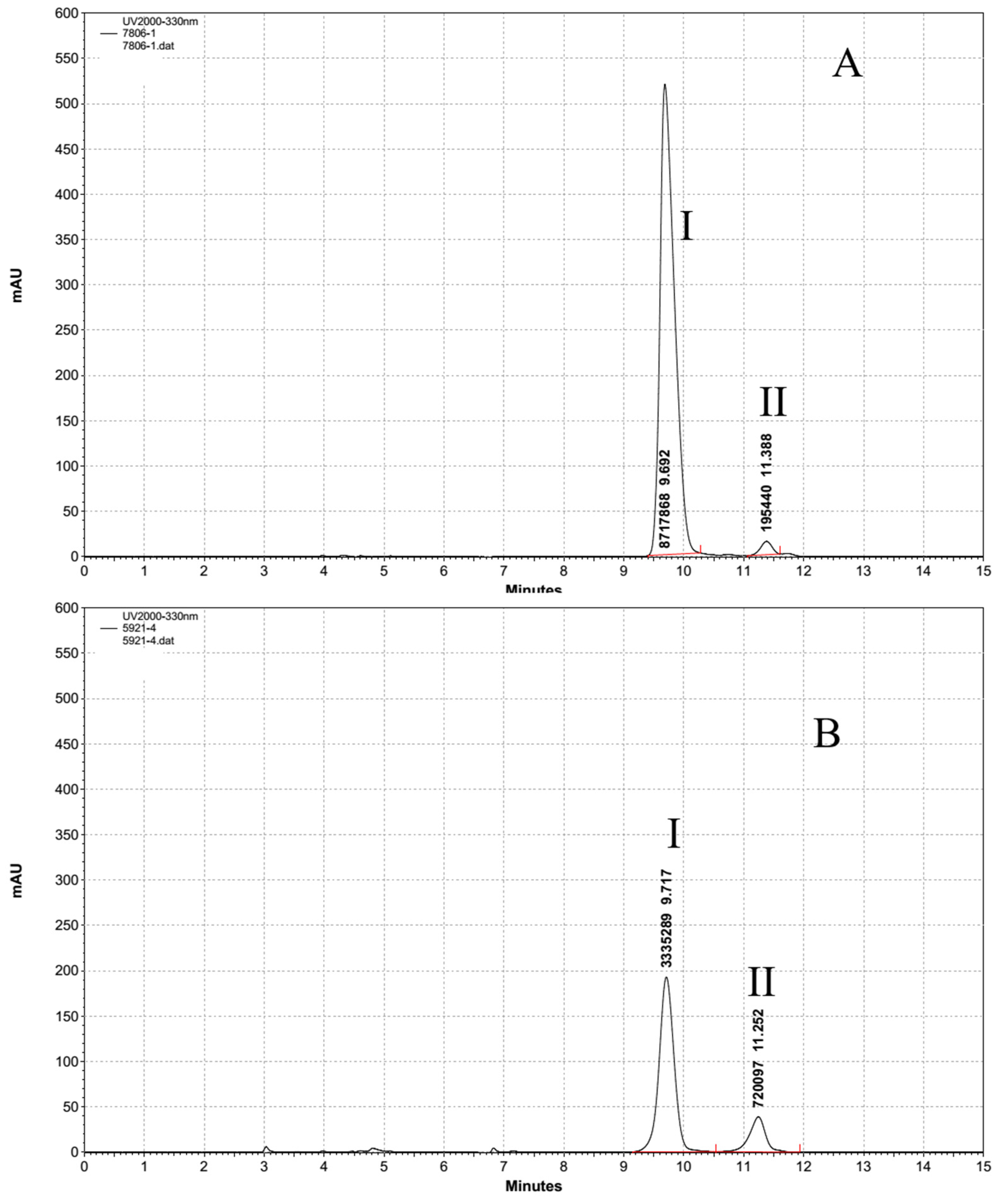

3.3. HPLC Analysis of the UV Absorption Substance

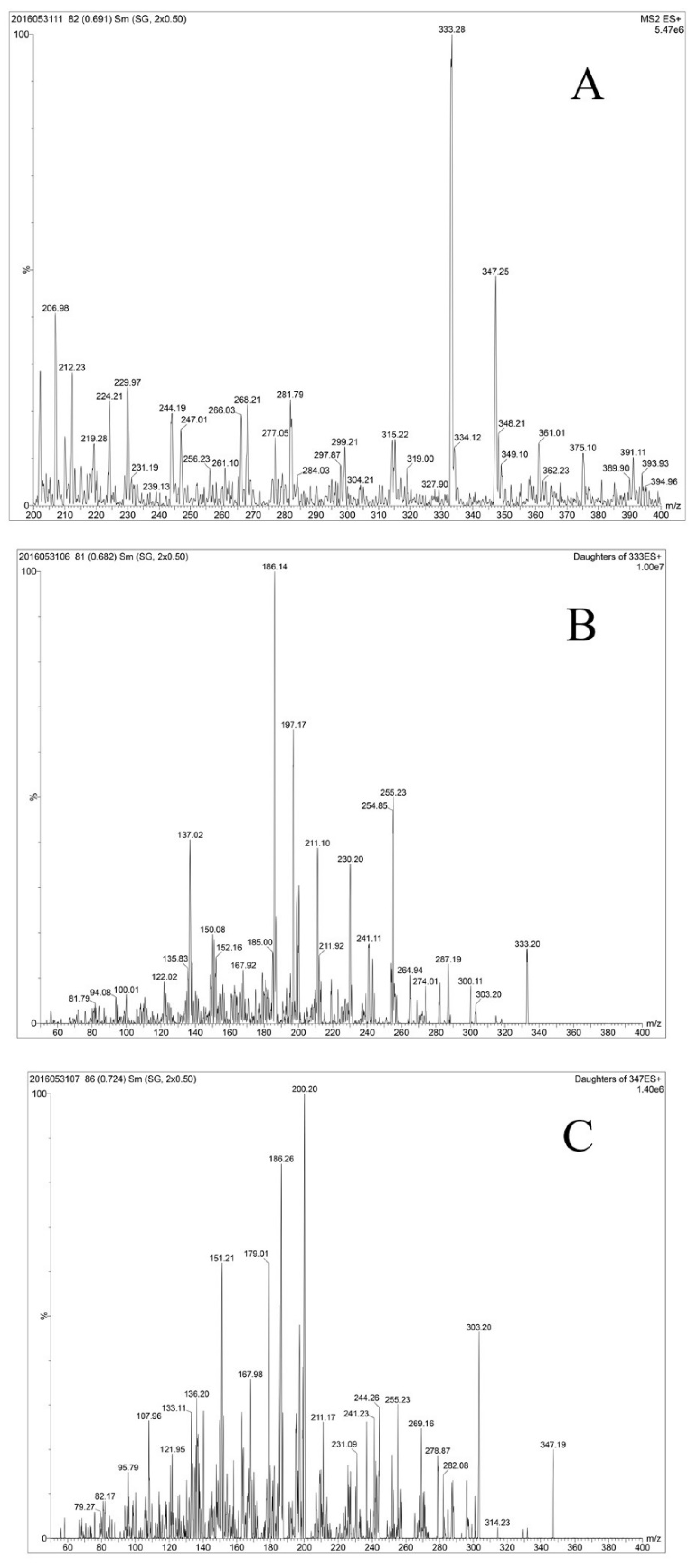

3.4. Identification of MAAs in the Aphanizomenon Strains

3.5. Quantification of MAAs in Different Aphanizomenon Strains

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Sample Availability

References

- Pattanaik, B.; Schumann, R.; Karsten, U. Effects of ultraviolet radiation on cyanobacteria and their protective mechanism. In Algae and Cyanobacteria in Extremely Environments; Cellular Origin, Life in Extreme Habitats and Astrobiology; Seckbach, J., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2007; Volume 11, pp. 29–45. [Google Scholar]

- Monika, E.S.; Siegfried, S. UV protection in cyanobacteria. Euro. J. Phy. 1999, 34, 329–338. [Google Scholar]

- Sinha, R.P.; Häder, D.P. UV-protectants in cyanobacteria. Plant Sci. 2008, 174, 278–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Ferran, G.P. Microbial ultraviolet sunscreens. Nat. Rev. Micro. 2011, 9, 791–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rastogi, R.P.; Sinha, R.P.; Moh, S.H.; Lee, T.K.; Kottuparambil, S.; Kim, Y.J.; Rhee, J.-S.; Choi, E.M.; Brown, M.T.; Häder, D.-P.; et al. Ultraviolet radiation and cyanobacteria. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2014, 141, 154–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vega, J.; Bonomi-Barufi, J.; Gómez-Pinchetti, J.L.; Figueroa, F.L. Cyanobacteria and red macroalgae as potential sources of antioxidants and UV radiation-absorbing compounds for cosmeceutical applications. Mar. Drugs 2020, 18, 659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernando, A.; Veronica, R.; Danay, C. Robust natural ultraviolet filters from marine ecosystems for the formulation of environmental friendlier bio-sunscreens. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 749, 141576. [Google Scholar]

- Wada, N.; Sakamoto, T.; Matsugo, S. Mycosporine-like amino acids and their derivatives as natural antioxidants. Antioxidants 2015, 4, 603–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreto, J.I.; Carignan, M.O.; Daleo, G.; Marco, S.G. Occurrence of mycosporine-like amino acids in the red-tide dinoflagellate alexandrium excavatum: UV-photoprotective compounds? J. Plankton Res. 1990, 12, 909–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conde, F.R.; Churio, M.S.; Previtali, C.M. The photoprotector mechanism of mycosporine-like amino acids. excited-state properties and photostability of porphyra-334 in aqueous solution. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2000, 56, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastogi, R.P.; Sinha, R.P. Biotechnological and industrial significance of cyanobacterial secondary metabolites. Biotechnol. Adv. 2008, 27, 521–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardozo, K.H.M.; Guaratini, T.; Barros, M.P.; Falcão, V.R.; Tonon, A.P.; Lopes, N.P.; Campos, S.; Torres, M.A.; Souza, A.O.; Colepicolo, P.; et al. Metabolites from algae with economical impact. Comp. Biochem. Phys. C 2007, 146, 60–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leach, C.M. Ultraviolet-absorbing substances associated with light-induced sporulation in fungi. Can. J. Bot. 2011, 43, 185–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, R.P.; Singh, S.P.; Häder, D.P. Database on mycosporines and mycosporine-like amino acids (MAAs) in fungi, cyanobacteria, macroalgae, phytoplankton and animals. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2007, 89, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeffrey, S.W.; Mactavish, H.S.; Dunlap, W.C.; Vesk, M.; Groenewoud, K. Occurrence of UV-A and UV-B-absorbing compounds in 152 species (206 strains) of marine microalgae. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 1999, 189, 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llewellyn, C.A.; Airs, R.L. Distribution and abundance of MAAs in 33 species of microalgae across 13 classes. Mar. Drugs 2010, 8, 1273–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sun, Y.Y.; Zhang, N.S.; Zhou, J.; Dong, S.S.; Zhang, X.; Guo, L.; Guo, G. Distribution, Contents, and Types of Mycosporine-Like Amino Acids (MAAs) in Marine Macroalgae and a Database for MAAs Based on These Characteristics. Mar. Drugs 2020, 18, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shick, J.M.; Dunlap, W.C. Mycosporine-like amino acids and related gadusols: Biosynthesis, acumulation, and UV-protective functions in aquatic organisms. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2002, 64, 223–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Whitehead, K.; Hedges, J.I. Analysis of mycosporine-like amino acids in plankton by liquid chromatography electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. Mar. Chem. 2002, 80, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geraldes, V.; Pinto, E. Mycosporine-Like Amino Acids (MAAs): Biology, Chemistry and Identification Features. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibelings, B.W.; Mur, L.R.; Kinsman, R.; Walsby, A.E. Microcystis changes its buoyancy in response to the average irradiance in the surface mixed layer. Arch. Hydrobiol. 1991, 120, 385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Walsby, A.E.; Kinsman, R.; Ibelings, B.W.; Reynolds, C.S. Highly buoyant colonies of the cyanobacterium Anabaena lemmermannii form persistent surface waterblooms. Arch. Hydrobiol. 1991, 121, 261–280. [Google Scholar]

- Klemer, A.R.; Cullen, J.J.; Mageau, M.T.; Hanson, K.M.; Sundell, R.A. Cyanobacterial buoyancy regulation: The paradoxical roles of carbon. J. Phycol. 1996, 32, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.W.; Häder, D.P.; Sommaruga, R. Occurrence of mycosporine-like amino acids (MAAs) in the bloom-forming cyanobacterium Microcystis aeruginosa. J. Plankton Res. 2004, 26, 963–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hu, C.L.; Völler, G.; Süßmuth, R.; Dittmann, E.; Kehr, J.C. Functional assessment of mycosporine-like amino acids in Microcystis aeruginosa strain PCC 7806. Environ. Microbiol. 2014, 17, 1548–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.L.; Ludsin, S.; Martin, J.; Dittmann, E.; Lee, J. Mycosporine-like amino acids (MAAs)-producing Microcystis in Lake Erie: Development of a qPCR assay and insight into its ecology. Harmful Algae 2018, 77, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommaruga, R.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Z.W. Multiple strategies of bloom-forming Microcystis to minimize damage by solar ultraviolet radiation in surface waters. Microb. Ecol. 2009, 57, 667–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, A.; Enk, C.D.; Hochberg, M.; Srebnik, M. Porphyra-334, a potential natural source for UV-A protective sunscreens. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2006, 5, 432–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.M.; Chen, W.; Li, D.H.; Shen, Y.W.; Li, G.B.; Liu, Y.D. First report of Aphantoxins in China-waterblooms of toxigenic Aphanizomenon flos-aquae in Dianchi Lake. Ecotox. Environ. Safe. 2006, 65, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.J.; Li, G.B.; Li, D.H.; Liu, Y.D. Temperature may be the dominating factor on the alternant succession of Aphanizomenon flos-aquae and Microcystis aeruginosa in Dianchi lake. Fresen. Environ. Bull. 2010, 20, 846–853. [Google Scholar]

- Rippka, R. [1] Isolation and purification of cyanobacteria. Method. Enzymol. 1988, 167, 3–27. [Google Scholar]

- Ichimura, T. Media for cultivation of algae. In Methods in Phycological Studies; Nishizawa, K., Chihara, M., Eds.; Kyouritsu Press: Tokyo, Japan, 1979; pp. 295–296. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z.X.; Shi, J.Q.; Lin, S.; Li, R.H. Unraveling molecular diversity and phylogeny of Aphanizomenon (Nostocales, Cyanobacteria) strains isolated from China. J. Phycol. 2010, 46, 1048–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neilan, B.A.; Jacobs, D.; Goodman, A.E. Genetic diversity and phylogeny of toxic cyanobacteria determined by DNA polymorphisms within the phycocyanin locus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1995, 61, 3327–3332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Neilan, B.A.; Jacobs, D.; Del, D.T.; Blackall, L.L.; Hawkins, P.R.; Cox, P.T.; Goodman, A.E. rRNA sequences and evolutionary relationships among toxic and nontoxic cyanobacteria of the genus Microcystis. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 1997, 47, 693–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gugger, M.; Lyra, C.; Henriksen, P.; Couté, A.; Humbert, J.F.; Sivonen, K. Phylogenetic comparison of the cyanobacterial genera Anabaena and Aphanizomenon. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Micro. 2002, 52, 1867–1880. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, T.A. Bioedit: A user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symp. Ser. 1999, 41, 95–98. [Google Scholar]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Peterson, D.; Filipski, A.; Kumar, S. MEGA 6: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol. Bio. Evol. 2013, 30, 2725–2729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kimura, M. A simple method for estimating evolutionary rates of base substitutions through comparative studies of nucleotide sequences. J. Mol. Evol. 1980, 16, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, S.; Hirata, Y. Isolation and structure of a mycosporine from the zoanthid Palythoa tuberculosa. Tetrahedron Lett. 1977, 18, 2429–2430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takano, S.; Uemura, D.; Hirata, Y. Isolation and structure of two new amino acids, palythinol and palythene, from the zoanthid Palythoa tuberculosa. Tetrahedron Lett. 1978, 19, 4909–4912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takano, S.; Nakanash, D.; Eemura, D.; Hirata, Y. Isolation and structure of a 334 nm UV-absorbing substance, porphyra-334 from the red alga Porphyra tenera kjellman. Chem. Lett. 1979, 8, 419–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tsujino, I.; Yabe, K.; SakuraiI, M. Presence of the near 358 nm UV-absorbing substances in red algae. In Bulletin of the Faculty of Fisheries Hokkaido University; Hokkaido University: Sapporo, Japan, 1979; Volume 30, pp. 100–108. [Google Scholar]

- Tsujino, I.; Yabe, K.; Sekikawa, I. Isolation and structure of a new amino acid, shinorine, from the red alga Chondrus yendoi yamada et mikami. Bot. Mar. 1980, 23, 65–68. [Google Scholar]

- Volkmann, M.; Gorbushina, A.A. A broadly applicable method for extraction and characterization of mycosporines and mycosporine-like amino acids of terrestrial, marine and freshwater origin. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2006, 255, 286–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia Pichel, F.; Castenholz, R.W. Occurrence of UV-absorbing, mycosporine-like compounds among cyanobacterial isolates and an estimate of their screening capacity. App. Environ. Microb. 1993, 59, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Singh, S.P.; Sinha, R.P.; Klisch, M.; Häder, D.P. Mycosporine-like amino acids (MAAs) profile of a rice-field cyanobacterium Anabaena doliolum as influenced by PAR and UVR. Planta 2008, 229, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinha, R.P.; Klisch, M.; Helbling, E.W.; Häder, D. Induction of mycosporine-like amino acids (MAAs) in cyanobacteria by solar ultraviolet-B radiation. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2001, 60, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, R.P.; Ambasht, N.K.; Sinha, J.P.; Klisch, M.; Häder, D.P. UVB-induced synthesis of mycosporine-like amino acids in three strains of Nodularia, (cyanobacteria). J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2003, 71, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, S.; Prajapat, G.; Abrar, M. Cyanobacteria as efficient producers of mycosporine-like amino acids. J. Basic Microb. 2017, 57, 715–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Gao, H.Y.; Li, X.Y.; Li, R.H. Identification and determination of mycosporine-like amino acids in Dolichospermum flos-aquae. Acta. Hydrobio. Sinica 2015, 39, 549–553. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Han, W.P.; Jane, T.; Partricial, T.B. Carotenoid Enhancement and its Role in Maintaining Blue-Green Algal (Microcystis aeruginosa) Surface Blooms. Limno. Oceanogr. 1983, 28, 847–857. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, H.B.; Qiu, B.S. Photosynthetic adaptation of a bloom-forming cyanobacterium Microcystis aeruginosa (Cyanophyceae) to prolonged UV-B exposure. J. Phycol. 2010, 41, 983–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Righi, V.; Parenti, F.; Schenetti, L.; Mucci, A. Mycosporine-like amino acids and other phytochemicals directly detected by high-resolution NMR on Klamath (Aphanizomenon flos-aquae) blue-green algae. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2016, 64, 6708–6715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ngoennet, S.; Nishikawa, Y.; Hibino, T.; Waditee-Sirisattha, R.; Kageyama, H. A Method for the Isolation and Characterization of Mycosporine-like Amino Acids from Cyanobacteria. Methods Protoc. 2018, 1, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Garcia Pichel, F.; Nübel, U.; Muyzer, G. The phylogeny of unicellular, extremely halotolerant cyanobacteria. Arch. Microb. 1998, 169, 469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rastogi, R.P.; Incharoensakdi, A. Characterization of UV-screening compounds, mycosporine-like amino acids, and scytonemin in the cyanobacterium Lyngbya sp.CU2555. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2013, 87, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Suh, S.-S.; Hwang, J.; Park, M.; Seo, H.H.; Kim, H.-S.; Lee, J.H.; Moh, S.H.; Lee, T.-K. Anti-inflammation activities of mycosporine-like amino acids (MAAs) in response to uv radiation suggest potential anti-skin aging activity. Mar. Drugs 2014, 12, 5174–5187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Choi, Y.H.; Dong, J.Y.; Kulkarni, A.; Sang, H.M.; Kim, K.W. Mycosporine-like amino acids promote wound healing through focal adhesion kinase (fak) and mitogen-activated protein kinases (map kinases) signaling pathway in keratinocytes. Mar. Drugs 2015, 13, 7055–7066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Oyamada, C.; Kaneniwa, M.; Ebitani, K.; Murata, M.; Ishihara, K. Mycosporine-like amino acids extracted from scallop (patinopecten yessoensis) ovaries: UV protection and growth stimulation activities on human cells. Mar. Biotechnol. 2008, 10, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, J.; Park, S.J.; Kim, I.H.; Choi, Y.H.; Nam, T.J. Protective effect of porphyra-334 on UVA-induced photoaging in human skin fibroblasts. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2014, 34, 796–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Misonou, T.; Saitoh, J.; Oshiba, S.; Tokitomo, Y.; Maegawa, M.; Inoue, Y.; Hori, H.; Sakurai, T. UV-absorbing substance in the red alga porphyra yezoensis (Bangiales, Rhodophyta) block thymine photodimer production. Mar. Biotechnol. 2003, 5, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, D.; Schurch, C.; Zulli, F. Mycosporine-like amino acids from red alga protect against premature skin-aging. Euro. Cosmetics 2006, 9, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

| Species | Stains | Origin | Accession Number (16S rRNA) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aphanizomenon gracile | Guanqiao01 | Guanqiao fish pond, China | MF098422 |

| FACHB1039 | Lake Dianchi, China | EU157983 | |

| Aphanizomnon flos-aquae | CHAB5919 | Lake Dianchi, China | KY242480 |

| CHAB5921 | KY242481 | ||

| CHAB5926 | KY242482 |

| Substance | [M + H]+ | Fragment Patterns | Organism | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| shinorine | 333.00 | 152,168,185,186,197,211,230,236,241,255, 256,274,287,300,318 | standards | [19] |

| 137,168,185,186,197,211.230,241,255 | Nodularia spumigena | [45] | ||

| 137,150,168,185,186,197,211,230,241,255, 274,287,300 | Aphanizomenon flos-aquae | This study | ||

| porphyra-334 | 347.00 | 137,152,168,186,188,200,210,230,244,255,270,283,303,314 | standards | [19] |

| 137,151,168,185,186,197,200,243,303 | Nodularia spumigena | [45] | ||

| 137,151,168,179,186,200,244,255,269,283, 303 | Aphanizomenon flos-aquae | This study |

| Species | Strains | Shinorine (µg/mg) | Porphyra-334 (µg/mg) | Total MAAs (µg/mg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aphanizomenon flos-aquae | CHAB5919 | 0.307 ± 0.016 | 0.136 ± 0.005 | 0.443 ± 0.02 |

| CHAB5921 | 0.385 ± 0.005 | 0.112 ± 0.001 | 0.497 ± 0.005 | |

| CHAB5926 | 0.378 ± 0.003 | 0.111 ± 0.002 | 0.489 ± 0.004 | |

| Aphanizomenon gracile | FACHB1039 | 0.049 ± 0.001 | ND | 0.049 ± 0.001 |

| Guanqiao01 | 0.003 ± 0.001 | ND | 0.003 ± 0.001 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, H.; Jiang, Y.; Zhou, C.; Chen, Y.; Yu, G.; Zheng, L.; Guan, H.; Li, R. Occurrence of Mycosporine-like Amino Acids (MAAs) from the Bloom-Forming Cyanobacteria Aphanizomenon Strains. Molecules 2022, 27, 1734. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27051734

Zhang H, Jiang Y, Zhou C, Chen Y, Yu G, Zheng L, Guan H, Li R. Occurrence of Mycosporine-like Amino Acids (MAAs) from the Bloom-Forming Cyanobacteria Aphanizomenon Strains. Molecules. 2022; 27(5):1734. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27051734

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Hang, Yongguang Jiang, Chi Zhou, Youxin Chen, Gongliang Yu, Liping Zheng, Honglin Guan, and Renhui Li. 2022. "Occurrence of Mycosporine-like Amino Acids (MAAs) from the Bloom-Forming Cyanobacteria Aphanizomenon Strains" Molecules 27, no. 5: 1734. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27051734

APA StyleZhang, H., Jiang, Y., Zhou, C., Chen, Y., Yu, G., Zheng, L., Guan, H., & Li, R. (2022). Occurrence of Mycosporine-like Amino Acids (MAAs) from the Bloom-Forming Cyanobacteria Aphanizomenon Strains. Molecules, 27(5), 1734. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27051734