Abstract

Diseases caused by viruses are a global threat, resulting in serious medical and social problems for humanity. They are the main contributors to many minor and major outbreaks, epidemics, and pandemics worldwide. Over the years, medicinal plants have been used as a complementary treatment in a range of diseases. In this sense, this review addresses promising antiviral plants from Marajó island, a part of the Amazon region, which is known to present a very wide biodiversity of medicinal plants. The present review has been limited to articles and abstracts available in Scopus, Web of Science, Science Direct, Scielo, PubMed, and Google Scholar, as well as the patent offices in Brazil (INPI), United States (USPTO), Europe (EPO) and World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO). As a result, some plants from Marajó island were reported to have actions against HIV-1,2, HSV-1,2, SARS-CoV-2, HAV and HBV, Poliovirus, and influenza. Our major conclusion is that plants of the Marajó region show promising perspectives regarding pharmacological potential in combatting future viral diseases.

1. Introduction

Viruses are a global threat and, in addition to health problems, cause serious social problems to humanity. They are the main contributors to many minor and major outbreaks, epidemics, and pandemics worldwide, such as swine flu, avian influenza, dengue fever, and the current SARS-CoV-2 that causes COVID-19 [1,2]. Although several treatment methods are available for viral diseases, viruses evolve rapidly and this requires a search for new potent and effective antiviral compounds with fewer or, better yet, no adverse side effects at all [1].

Medicinal plants have been documented as a means of complementary treatments that are useful for a range of diseases. However, few have been applied to the treatment of viral diseases. This is because some viral targets have very specific interactions with with natural molecules. Furthermore, most antivirals that are used as drugs show undesirable side effects, or the virus ends up developing a resistance to the drug, as well as recurrence and latency. In this sense, many medicinal plants can be candidates for the discovery of new antivirals due to their strong antiviral activity, fewer side effects, and the capacity to inhibit the replication or synthesis of some virus genome [3]. In addition, science has already proved the safer benefits of herbal medicines and also supports the idea of improved therapy when these herbal medicines are used in combination with conventional antiviral medicines [4].

Among many islands around the world, the island of Marajó which is part of the Brazilian Amazon, is known to have several cultures formed by indigenous, quilombolas, and mestizo populations that make use of traditional knowledge of plants, which are sometimes used as the only form of therapy in their traditional medicine. The Amazon region also has a very wide plant diversity, being estimated to have from 25 to 30 thousand species of endemic plants, and some species are also associated with the treatment of diseases [5]. In this sense, according to the literature [6], many plants from Marajó island are frequently used for the treatment of diseases, and could be a source of new specific bioactive compounds. This can be applied to expand promising studies.

Based on this, we highlight the importance of searching for new natural sources with antiviral potential, as they can be an alternative to high-cost synthetic drugs with undesirable side effects, in addition to facilitating access to the population. Therefore, we describe a brief narrative review of the main plants inserted in the ethnomedicinal use of Marajó island to treat a lot of diseases, which are directly or indirectly associated with viral agents.

2. Data Research Methodology

The present narrative review originated from the empirical knowledge of some authors of this research and the daily coexistence with the ethnomedical use of plants from the Marajó Island. Posteriorly, the pharmacological and botanical correspondence with the species and its reported therapeutic indication were conformed to specific search descriptors terms in Scopus, Web of Science, Science Direct, Scielo, PubMed, and Google Scholar, as well as the patent offices in Brazil (INPI), United States (USPTO), Europe (EPO) and World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO). The main keywords of the search were “Marajó”, “antiviral”, “medicinal herbs”, “herbal medicines”, “medicinal plants”, and “traditional medicine”. We emphasize that, in addition to these terms, the names of the species of interest were used after filtering the twelve plants reported in this study.

3. Main Vectors of Diseases Caused by Pathogenic Viruses

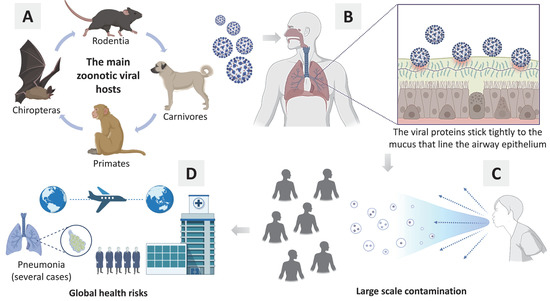

The most emerging viruses are zoonotic, which means that they can be transmitted from animals to humans, especially from mammals of the orders Chiroptera, Rodentia, Primates, and Carnivores, as they are hosts to a large diversity of viruses (see Figure 1). For instance, the literature investigated bats as the main vectors responsible for the most zoonotic viral infections. However, the total number of viruses identified in rodents is higher than that in bats [7]. In any case, whenever a virus jumps from animal to human, society is at serious risk.

Figure 1.

(A) The main animals (primary hosts) responsible for zoonotic viral transmission; (B) Basic general mechanism about viral infection in human cells; (C) Contamination of several people in society; (D) Global health risks (e.g., pandemic, hospital overcrowding, several cases of pneumonia, thousand deaths).

At present, the world is on alert to the emergence of viruses that are dangerous to public health and have the potential to begin a new pandemic. However, most zoonotic viruses transmitted from animals to humans are not easily transmitted between humans. In this sense, we can have a new problem: humans as new hosts [7].

In Brazil, other important vectors are mosquitoes and ticks, which transmit arbovirus to vertebrates, and are known as arthropod-borne viruses. Arthropods that facilitate efficient virus transmission between susceptible hosts are called vectors. Several arboviruses that are pathogenic to humans, such as the yellow fever virus (YFV), the Chikungunya virus (CHIKV), and the Zika virus (ZIKV), share the same vector, Aedes aegypti mosquito, which are abundant in tropical and subtropical regions [7].

6. Future Perspectives

Some antiviral plants described here are also found in other regions, and some compounds can be detected in other species. However, the study of plants that are on Marajó island, although some are not native to the island, are fundamental for the inventory of active biological sources available in the region. Furthermore, scientific reports about those species could promote the development of Marajó, as the trade in medicinal plants could alleviate the poverty of the native peoples, and lead to significant independence, albeit small, from synthetic, expensive, and inaccessible medications. Therefore, these plants are promissory and can open prospects for the use of unexplored resources, which could help in the economic and sustainable use of Brazil’s tropical forests.

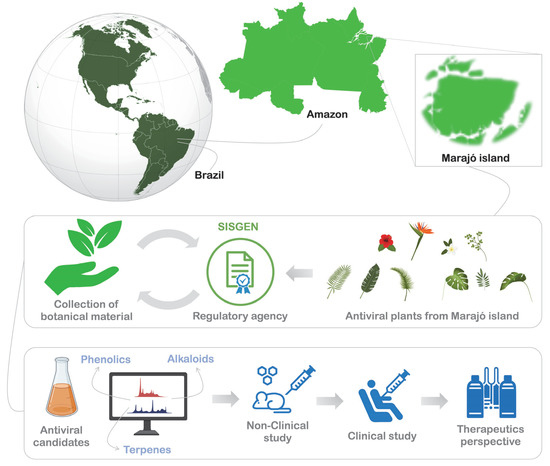

Based on the experimental designs available in the literature, we suggest a workflow (Figure 3) for the prospective and respective applications of antiviral candidates (e.g., Phenolics, alkaloids, and terpenes) from plants of the Marajó Island. We believe that studies based on this perspective may lead to promising and indispensable therapeutic alternatives. We carefully highlight, that for highly skilled researchers, this experimental design is already known. However, we also hope to instigate young researchers who carry a larger folk knowledge, for it is of paramount importance that the population receives a return on any resources generated from biodiversity. For this, comprehensive research needs to be developed and validated by regulatory agencies, to ensure that the population enjoys any benefits that these studies may generate. Furthermore, we highlight the importance of translating the folk knowledge of native people to the analytical metrics of scientific research, so that studies can be guided by unequivocal interests.

Figure 3.

Future prospects for the use of medicinal plants from Marajó island for the discovery of antiviral candidates and the development of therapeutic alternatives.

7. Conclusions

This study shows that the Marajó island (Amazon region), has a high diversity of medicinal plants with high antiviral potential, and must be further studied and valorized. It was seen that secondary metabolites from these species have bioactive compounds that can be useful if isolated and synthesized as potential antiviral agents; however, it is expected that such compounds should exhibit greater potency, selectivity, duration of action, bioavailability, and reduced toxicity. It is important to have a base in the traditional and scientific knowledge of the Marajó plants, as the plant kingdom is becoming an important source of new agents with special biological targets. In recent years, the efforts of several researchers have helped to discover and isolate many secondary metabolites from plants that are also found in Marajó island, have potential antiviral action and can be used in therapy against infectious diseases caused by viruses.

Author Contributions

Conception and design of the study: P.W.P.G. and L.M.; acquisition of data: P.W.P.G., L.M., E.G., A.K., C.B., A.M., S.P., M.R. and C.S.; analysis and/or interpretation of data: P.W.P.G., L.M., A.M., S.P., C.S. and M.S.; Drafting the manuscript: P.W.P.G., L.M., E.G., A.K. and C.B.; revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content: M.R., C.S. and M.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq). Process: 141680/2018-0, Modality: Doctoral Scholarship—GD Graduate Program.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All support data used in this study are available from the authors.

Acknowledgments

All authors acknowledge the institutions the Federal University of Pará, Federal Rural University of Amazonia, Pró-Reitoria de Pesquisa e Pós-Graduação (Propesp/UFPA) and SGB Amravati University for supporting research and for the access to didactic materials and scientific papers.

Conflicts of Interest

We declare no current or potential conflict of interest related to this article.

References

- Mishra, S.; Pandey, A.; Manvati, S. Coumarin: An emerging antiviral agent. Heliyon 2020, 6, e03217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Zhou, Q.; Li, Y.; Garner, L.V.; Watkins, S.P.; Carter, L.J.; Smoot, J.; Gregg, A.C.; Daniels, A.D.; Jervey, S.; et al. Research and Development on Therapeutic Agents and Vaccines for COVID-19 and Related Human Coronavirus Diseases. ACS Cent. Sci. 2020, 6, 315–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chattopadhyay, D. Role and scope of ethnomedical plants in the development of antivirals. Pharmacologyonline 2006, 3, 64–72. [Google Scholar]

- Maryam, M.; Te, K.K.; Wong, F.C.; Chai, T.T.; Low, G.K.K.; Gan, S.C.; Chee, H.Y. Antiviral activity of traditional Chinese medicinal plants Dryopteris crassirhizoma and Morus alba against dengue virus. J. Integr. Agric. 2020, 19, 1085–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrollo, C.T.; Kinupp, V.F.; Shepard, G.; Heinrich, M. Medicinal Plants at Rio Jauaperi, Brazilian Amazon: Ethnobotanical Survey and Environmental Conservation. Available online: https://reader.elsevier.com/reader/sd/pii/S0378874116301696?token=D504E2452034E7AC5CEE858FB49534EFC37C1F90F2654F0DD575E5CEA955D7A2D873350A9B77375198B7736F3E20EC3F&originRegion=us-east-1&originCreation=20220120202522 (accessed on 20 January 2022).

- Divya, M.; Vijayakumar, S.; Chen, J.; Vaseeharan, B.; Durán-Lara, E.F. South Indian medicinal plants can combat deadly viruses along with COVID-19?—A review. Microb. Pathog. 2020, 148, 104277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Artika, I.M.; Wiyatno, A.; Ma’Roef, C.N. Pathogenic viruses: Molecular detection and characterization. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2020, 81, 104215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neto, E.M.C.; Resende, J.J. A percepção de animais como “insetos” e sua utilização como recursos medicinais na cidade de Feira de Santana, Estado da Bahia, Brasil. Acta Sci. Biol. Sci. 2004, 26, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, M.V.B.; Rodrigues, S.T.; Vasconcelos, A.L.F. Plantas medicinais utilizadas na medicina etnoveterinária praticada na ilha do Marajó. Embrapa Amaz. Orient.-Doc. 2012, 380, 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- Azevedo, M.V.D.M.P.D.S.; Lins, S.R.D.O. Aplicações Terapêuticas da Alpinia Zerumbet (Colônia) Baseado na Medicina Tradicional: uma Revisão Narrativa (2010–2020)/Therapeutic Applications of the Alpinia Zerumbet (Colônia) Based on Traditional Medicine: A Narrative Review (2010–2020). Braz. J. Dev. 2020, 6, 84222–84242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, A.; Chompoo, J.; Kishimoto, W.; Makise, T.; Tawata, S. HIV-1 Integrase and Neuraminidase Inhibitors from Alpinia zerumbet. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 2857–2862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, M.L.L.; da Mota, A.C.C.; Deana, A.M.; Cavalcante, L.A.D.S.; Horliana, A.C.R.T.; Pavani, C.; Motta, L.J.; Fernandes, K.P.S.; Mesquita-Ferrari, R.A.; da Silva, D.F.T.; et al. Antimicrobial photodynamic therapy with Bixa orellana extract and blue LED in the reduction of halitosis—A randomized, controlled clinical trial. Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther. 2020, 30, 101751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kar, B.; Chandar, B.; Rachana, S.S.; Bhattacharya, H.; Bhattacharya, D. Antibacterial and genotoxic activity of Bixa orellana, a folk medicine and food supplement against multidrug resistant clinical isolates. J. Herb. Med. 2021, 32, 100502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento Moraes Neto, R.N.M.; Guedes Coutinho, G.; de Oliveira Rezende, A.; de Brito Pontes, D.; Larissa Pinheiro Soares Ferreira, R.; de Araújo Morais, D.; Pontes Albuquerque, R.; Gonçalves Lima-Neto, L.; Cláudio Nascimento da Silva, L.; Quintino da Rocha, C.; et al. Compounds isolated from Bixa orellana: Evidence-based advances to treat infectious diseases. Rev. Colomb. Cienc. Químico-Farm. 2020, 49, 581–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.-F.; Bai, L.-P.; Huang, W.-B.; Li, X.-Z.; Zhao, S.-S.; Zhong, N.-S.; Jiang, Z.-H. Comparison of in vitro antiviral activity of tea polyphenols against influenza A and B viruses and structure–activity relationship analysis. Fitoterapia 2014, 93, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, R.; Tao, J.-Y.; Zhang, S.-L.; Zhao, L.; Yue, X.; Wang, Y.-F.; Ye, P.; Dong, J.-H.; Zhu, Y.; Wu, J.-G. In vitro antiviral activity of lutein against hepatitis B virus. Phytother. Res. 2010, 24, 1627–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Battistini, R.; Rossini, I.; Ercolini, C.; Goria, M.; Callipo, M.R.; Maurella, C.; Pavoni, E.; Serracca, L. Antiviral Activity of Essential Oils against Hepatitis A Virus in Soft Fruits. Food Environ. Virol. 2019, 11, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.-S.; Zhang, Y.; Li, H.-T.; Wu, C.-H.; El-Seedi, H.R.; Ye, W.-K.; Wang, Z.-W.; Li, C.-B.; Zhang, X.-F.; Kai, G.-Y. Limonoids from Citrus: Chemistry, anti-tumor potential, and other bioactivities. J. Funct. Foods 2020, 75, 104213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, F.M.A.; Da Silva, K.P.A.; De Oliveira, L.P.M.; Costa, E.V.; Koolen, H.H.; Pinheiro, M.L.B.; De Souza, A.Q.L.; De Souza, A.D.L. Flavonoid glycosides and their putative human metabolites as potential inhibitors of the SARS-CoV-2 main protease (Mpro) and RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp). Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 2020, 115, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Liu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, P.; Zhong, W.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Xu, Y.; Li, M.; Li, X.; et al. Analysis of therapeutic targets for SARS-CoV-2 and discovery of potential drugs by computational methods. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2020, 10, 766–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, D.; Variyar, E.J. Repurposing simeprevir, calpain inhibitor IV and a cathepsin F inhibitor against SARS-CoV-2 and insights into their interactions with Mpro. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2020, 40, 325–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganeshpurkar, A.; Saluja, A.K. The Pharmacological Potential of Rutin. Saudi Pharm. J. 2017, 25, 149–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, N.; Faccin-Galhardi, L.C.; Espada, S.F.; Pacheco, A.C.; Ricardo, N.; Linhares, R.E.C.; Nozawa, C. Sulfated polysaccharide of Caesalpinia ferrea inhibits herpes simplex virus and poliovirus. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2013, 60, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tshilanda, D.D.; Ngoyi, E.M.; Kabengele, C.N.; Matondo, A.; Bongo, G.N.; Inkoto, C.L.; Mbadiko, C.M.; Gbolo, B.Z.; Lengbiye, E.M.; Kilembe, J.T.; et al. Ocimum Species as Potential Bioresources against COVID-19: A Review of Their Phytochemistry and Antiviral Activity. Int. J. Pathog. Res. 2020, 5, 42–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayisi, N.K.; Nyadedzor, C. Comparative in vitro effects of AZT and extracts of Ocimum gratissimum, Ficus polita, Clausena anisata, Alchornea cordifolia, and Elaeophorbia drupifera against HIV-1 and HIV-2 infections. Antivir. Res. 2003, 58, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thayil, S.; Thyagarajan, S.P. PA-9: A Flavonoid Extracted from Plectranthus amboinicus Inhibits HIV-1 Protease. Int. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. Res. 2016, 8, 1020–1024. [Google Scholar]

- Siqueira, E.M.D.S.; Lima, T.L.C.; Boff, L.; Lima, S.G.M.; Lourenço, E.M.G.; Ferreira, É.G.; Barbosa, E.G.; Machado, P.; Farias, K.J.S.; Ferreira, L.D.S.; et al. Antiviral Potential of Spondias mombin L. Leaves Extract Against Herpes Simplex Virus Type-1 Replication Using In Vitro and In Silico Approaches. Planta Med. 2020, 86, 505–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Río, J.; Fuster, M.; Gómez, P.; Porras, I.; García-Lidón, A.; Ortuño, A. Citrus limon: A source of flavonoids of pharmaceutical interest. Food Chem. 2004, 84, 457–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza, R.C.; Modesto, S.P.B.; Maués, K.M.G.; Dos Santos, J.C.; Farias, A.N.; Biancalana, A.; Biancalana, F.S.C. Avaliação da ocorrência de fungos demáceos em espinhos de limoeiro-taiti (citrus latifólia tanaka) no município de Soure-Pa/Evaluation of the occurrence of demaceous fungus in spines of lemon-taiti (citrus latifólia tanaka) in Soure-Pa municipality. Braz. J. Health Rev. 2020, 3, 14894–14910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prall, S.; Bowles, E.J.; Bennett, K.; Cooke, C.G.; Agnew, T.; Steel, A.; Hausser, T. Effects of essential oils on symptoms and course (duration and severity) of viral respiratory infections in humans: A rapid review. Adv. Integr. Med. 2020, 7, 218–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheppard, E.P.; Boyd, E.M. Lemon oil as an expectorant inhalant. Pharmacol. Res. Commun. 1970, 2, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osong Public Health and Research Perspectives. Osong Public Health Res. Perspect. 2012, 3, 62. [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gumisiriza, H.; Birungi, G.; Olet, E.A.; Sesaazi, C.D. Medicinal plant species used by local communities around Queen Elizabeth National Park, Maramagambo Central Forest Reserve and Ihimbo Central Forest Reserve, South western Uganda. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2019, 239, 111926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moura-Costa, G.F.; Nocchi, S.R.; Ceole, L.F.; de Mello, J.C.P.; Nakamura, C.V.; Filho, B.P.D.; Temponi, L.G.; Ueda-Nakamura, T. Antimicrobial activity of plants used as medicinals on an indigenous reserve in Rio das Cobras, Paraná, Brazil. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2012, 143, 631–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).