Abstract

Viral infection almost invariably causes metabolic changes in the infected cell and several types of host cells that respond to the infection. Among metabolic changes, the most prominent is the upregulated glycolysis process as the main pathway of glucose utilization. Glycolysis activation is a common mechanism of cell adaptation to several viral infections, including noroviruses, rhinoviruses, influenza virus, Zika virus, cytomegalovirus, coronaviruses and others. Such metabolic changes provide potential targets for therapeutic approaches that could reduce the impact of infection. Glycolysis inhibitors, especially 2-deoxy-D-glucose (2-DG), have been intensively studied as antiviral agents. However, 2-DG’s poor pharmacokinetic properties limit its wide clinical application. Herein, we discuss the potential of 2-DG and its novel analogs as potent promising antiviral drugs with special emphasis on targeted intracellular processes.

1. SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic and Current COVID-19 Treatment

By the end of June 2022, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection had been diagnosed at 560 M cases causing 6.36 M deaths worldwide [1]. The rapid spread of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) was declared an emerging public health threat by the World Health Organization. It caused a global pandemic not observed in recent history. The incubation period for COVID-19 was up to 14 days, with a median time of 4–5 days from exposure to symptoms onset [2]. Most people infected with the SARS-CoV-2 virus experienced mild to moderate respiratory illness and recovered without requiring special treatment. However, older people and those with underlying medical problems, such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, obesity, chronic respiratory disease, and cancer, were more likely to develop severe illness.

Vaccination remains the most effective way to prevent severe illness caused by SARS-CoV-2 infection. However, despite the widespread availability of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines, many individuals are either not fully vaccinated or cannot mount adequate responses to the current vaccines. Some of these people, if infected, are at high risk of progressing to develop more serious COVID-19. The most severe SARS-CoV-2 complication is pneumonia that, according to Grant et al. [3], lasts longer and causes more harm than typical viral pneumonia. While other types of pneumonia rapidly infect large regions of the lungs, COVID-19 begins in numerous small areas of the lungs. As COVID-19 pneumonia slowly moves through the lungs, it leaves damaged lung tissue in its wake. Additionally, fever, low blood pressure, and organ damage have been reported in COVID-19 patients [3].

According to available National Institutes of Health (NIH) treatment guidelines, the standard of care (SOC) for hospitalized COVID-19 patients, with progressive disease development, includes the use of corticosteroids, such as dexamethasone [4], increasing the risk of permitting secondary bacterial and fungal infections, due to the extensive and prolonged immune suppression.

Very recently, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the additional use of baricitinib (selective inhibitor of Janus kinases 1 and 2 (JAK1/2)) or tocilizumab (a recombinant humanized anti-IL-6 receptor monoclonal antibody) as anti-inflammatory compounds [5] for patients who require a high-flow device for noninvasive ventilation and have rapidly increasing systemic inflammation. On 30 July 2021, the FDA also expanded the Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) indication for the anti-SARS-CoV-2 monoclonal antibodies casirivimab plus imdevimab to allow this combination to be used as post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP). This combination was approved for use in mild to moderate COVID-19 adults and pediatric patients (>12 years old) with a positive result of the SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR test and at high risk for progression to severe COVID-19, due to the above mentioned underlying medical problems. On 22 December 2021, the FDA granted emergency use authorization for the oral protease inhibitor nirmatrelvir for prevention of severe cases of COVID-19. However, two recent studies indicate that the SARS-CoV-2 virus can mutate its genome making the virus resistant to nirmatrelvir [6,7].

Today, the number of drugs approved for COVID-19 treatment is limited and does not entirely fulfill the medical need for highly efficient, cost-effective, and readily accessible antiviral treatment. Very recently, in May 2021, the Drug Controller General of India gave emergency approval for 2-deoxy-D-glucose (2-DG) in its oral formulation as an adjunct therapy along with the SOC in hospitalized moderate-to-severe COVID-19 patients. According to the phase III clinical trial results, COVID-19 patients treated with 2-DG did not require supplemental oxygen therapy by day three, compared to those treated with SOC (42% vs. 31%), thereby indicating an early recovery of pulmonary function. Notably, a similar trend was observed in patients aged 65 and above [8]. The only information from these trials is available from a government press release and trials’ registrations on the Clinical Trial Registry of India. Both the second and third phases of the 2-DG trials were not double blinded, making interpretation of the results less reliable [9]. Nevertheless, the clinical trials leading to 2-DG approval in India further support the idea of using D-glucose analogs as an antiviral therapy. The rationale for using 2-DG in antiviral treatment is presented below.

2. Metabolic Shift in Host Cells during Viral Infection

Viral infections induce virus-specific metabolic reprogramming in host cells [10]. Viral replication entirely relies on the host cell machinery to synthesize viral components, such as nucleic acids, proteins, glycans and lipid membranes [11]. As virus formation depends on the metabolic capacity of the host cell to provide required components and energy in the form of ATP, the majority of viruses modulate the host cell metabolism to optimize the biosynthetic needs for virus growth. Both DNA and RNA viruses have been shown to affect various aspects of host metabolism, including increased glycolysis, elevated pentose phosphate activity, and enhanced amino acid and lipid synthesis. Generally, viruses mainly increase the consumption of key nutrients like glucose and glutamine. However, the precise metabolic changes are often virus-dependent and can vary even within the same family of viruses, as well as with the host cell type [10].

There are multiple ways in which viruses can alter host cell metabolic processes. For example, it was shown that human cytomegalovirus (HCMV), herpesvirus-1 (HSV-1), and adenovirus (ADWT) increase glycolysis and the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, as well as enhance nucleotide and lipid synthesis [12,13,14].

According to Mayer et al. [15], most virus-infected host cells upregulate glycolysis. It should be explained that under homeostatic and aerobic conditions, cells maintain ATP production mainly by aerobic glycolysis, followed by feeding pyruvate into the TCA cycle and subsequent utilization of reduced molecules into the oxidative phosphorylation pathway. On the contrary, pyruvate is converted to lactate under anaerobic conditions, which is then eliminated to extracellular space. Aside from the anaerobic conditions, Otto Warburg observed that cancer cells utilize glucose mainly via glycolysis, even under normal oxygen conditions (normoxia), the so-called Warburg effect [16]. Cells infected by certain viruses appear to adapt similar metabolic alterations to cope with the high anabolic demands of virion production. Whereas the overall virus-induced metabolic abnormalities are unique and virus-specific, the upregulation of the glycolysis pathway is a common phenomenon, and as such has been considered a target for antiviral therapy. Significantly, increased glycolysis activity has also been described in coronavirus infections, including porcine epidemic diarrhea coronavirus (PED), MERS-CoV, and SARS-CoV-2 [17,18,19,20]. One of the common mechanisms induced by a viral infection that leads to glycolysis is upregulation of the phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K)/protein kinase B (PKB/Akt) signaling pathway, which regulates the expression of glucose transporters 1 or 4 (GLUT1, GLUT4) [18,20,21,22]. Elevated expression of GLUTs facilitates an increase in glucose uptake by infected host cells. In response, the level of glycolytic enzymes, such as hexokinase (HK), lactate dehydrogenase (LDHA), or phospho-fructokinase 1 (PFK-1), is also higher [21,23,24]. Viruses that were confirmed to induce the Warburg effect in host cells are summarized in Table 1. Additionally, viruses such as human T cell leukemia virus type 1 (HTLV-1) utilize GLUT1 as a receptor for entry [25]. While there is no literature that investigates the effect of 2-DG on HTLV-1 replication or infection, it is possible that 2-DG could impact HTLV-1 infection through competitive binding with the GLUT1 receptor.

Table 1.

Viruses upregulating host cell glycolysis as a mechanism required for their optimal replication.

In summary, several epidemiologically significant viruses and their efficient replication in host cells depend on the glycolysis process.

3. The Importance of Host Glycosylation Process for Viral Replication

Carbohydrates are one of the most critical components necessary for the synthesis of N-glycans in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). Numerous viruses rely on the expression of specific viral oligosaccharides crucial for viral entry into the host cells, proteolytic processing, protein trafficking, and evading detection by the host immune system [43,44]. In the N-glycosylation process, a high mannose core is attached to the amide nitrogen of asparagine in the context of the conserved motif Asn-X-Ser/Thr. It occurs early in the protein synthesis, followed by a complex process of trimming and remodeling of the oligosaccharide during transit through the ER and Golgi [43]. It has been shown that several viruses hijack the cellular glycosylation pathway to modify viral proteins. Adding N-linked oligosaccharides to the envelope or surface proteins promotes proper folding and subsequent trafficking using host cell chaperones and folding factors. Often, viruses use calnexin and or calreticulin to facilitate the proper folding of overexpressed viral proteins [45]. Although the cell cannot distinguish between host and viral proteins, one difference noted is an increase in the level of glycosylation in many viral glycoproteins. During viral evolution, glycosylation sites are easily added and deleted, increasing the possibility of viral modifications. Glycosylation sites have a significant impact on the survival and transmissibility of the virus and small changes can alter protein folding and conformation, affecting portions of the entire molecule [46]. Further, changes in glycosylation can affect interactions with receptors, influence virus entry, and protect the virus from neutralizing antibodies [44,47]. It was shown that many viruses even use glycosylation for important functions in their pathogenesis and immune evasion, including influenza A and B, HIV, and hepatitis C [23,28,48,49].

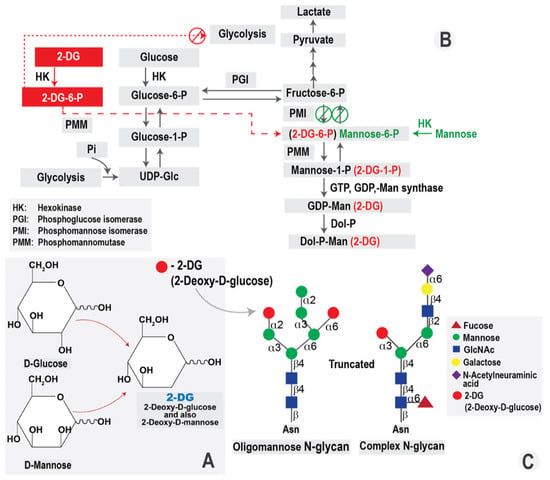

The glycosylation process requires mannose, an essential constituent of N-glycans. Mannose enters the cells via hexose transporters present in the plasma membrane. It is immediately phosphorylated by HK and then either catabolized via mannose phosphate isomerase (MPI) or diverted toward glycosylation through phoshomannomutase-2 (PMM2) [50]. On the other hand, mannose-6-phosphate (M6P) could also be obtained via the MPI-catalyzed isomerization of fructose-6-phosphate, synthesized from glucose-6-phosphate in the glycolysis pathway [51]. Moreover, a virus-induced metabolic shift in infected host cells results directly in higher activity of HK, which upregulates the glycosylation process that is required for rapid and massive production of infectious progeny in order to disseminate the infection.

Based on the mechanisms mentioned above, inhibition of glycolysis could be a potent antiviral approach. One of the most widely used glycolysis inhibitors is the D-glucose analog, 2-deoxy-D-glucose (2-DG).

5. 2-DG in Clinical Trials

Due to 2-DG’s ability to inhibit glycolysis, ATP synthesis and protein glycosylation, 2-DG appears to be very efficient in killing highly glycolytic cells. As mentioned previously, metabolic shift is characteristic of viral infection and cancer cells. Importantly, all described 2-DG effects are mostly observed in glycolytic cells, without significant influence on the viability of normal cells [80]. Thus, 2-DG has been explored as a cytotoxic compound or an adjuvant agent for various clinically used chemotherapeutic drugs in breast, prostate, ovarian, lung, glioma, and other cancer types. 2-DG was also tested as a radio-sensitizing agent in cancer radiotherapy. The efficacy of 2-DG as an anticancer agent was reviewed in detail in our paper [54]. Due to the importance of cancer treatment for global population healthcare, 2-DG has been tested in oncological clinical trials. Clinical trials registered in India using 2-DG in COVID-19 patients are the first documented cases for clinical use of 2-DG in viral infections.

Despite the numerous preclinical and clinical studies, the use of 2-DG in cancer and viral treatment has been limited. Its rapid metabolism and short half-life (according to Hansen et al., after treatment with infusion of 50 mg/kg2-DG, its plasma half-life was only 48 min [81]), make 2-DG a relatively poor drug candidate. Moreover, 2-DG must be given at relatively high concentrations (≥5 mmol/L) to compete with blood glucose [82]. According to Stein et al. [83], the dose of 45 mg/kg received orally on days 1–14 was defined as safe because patients did not experience any dose-limiting toxicities. Notably, at the dose of 60 mg/kg, two patients experienced dose-limiting toxicity of grade 3–asymptomatic QTc prolongation. According to former studies published by Burckhardt et al. [84] and Stalder et al. [85], among patients exposed to 2-DG, non-specific T wave flattening and QT prolongation, without any event of severe arrhythmia, developed.

A study of 2-DG in humans was published in 2013 and reported the results of an association regimen of 2-DG and docetaxel in patients with advanced solid tumors [86]. In this study, based on the overall tolerability of the 2-DG treatment, the authors used a starting dosage of 63 mg/kg, which was considered safe. At the higher dose of 88 mg/kg, patients presented plasma glucose levels above 300 mg/dL and glucopenia symptoms, including sweating, dizziness, and nausea, mimicking the symptoms of hypoglycemia [86]. Other significant adverse effects recorded during the trial at 63–88 mg/kg doses were gastrointestinal bleeding (6%) and reversible grade 3 QTc prolongation (22%). After the end of the study, one patient died from a serious adverse event of cardiac arrest 17 days after the last dose of 2-DG. ECG done ten days before death showed persistent T-wave inversion and no QT prolongation [86]. However, it should be noted that the eligibility criteria of patients in this study, who had advanced or metastatic solid tumors, could have played a confounding role in relation to survival and overall patient condition. Clinical testing of 2-DG as a chemotherapy has been performed in humans and demonstrated good tolerability. Antiviral efficacy of 2-DG has been demonstrated in various models and showed a good tolerability profile. Currently, there are no available reports presenting data about safety and efficacy of 2-DG in the COVID-19 clinical trials. It is also possible, if not likely, that some hospitalized patients receiving i.v. fluids may also receive glucose at 5%, 10% or even higher (not limited to COVID-19 patients). This can be especially the case for patients that are intubated and unable to drink and eat. However, our primary goal is to reduce hospitalization rates and improve recovery through early treatment of patients that are not receiving i.v. fluid therapy yet, especially in outpatient groups of COVID-19 infected population.

Based on the available data, our group is not aware of any specific negative impact of this type of therapy against other viral infections. The only exception could be related to Herpes infection and that is being addressed in the other section of the paper. In general, it is certainly possible that patients receiving glucose i.v. therapies may not benefit from 2-DG, but we can only speculate at this stage.

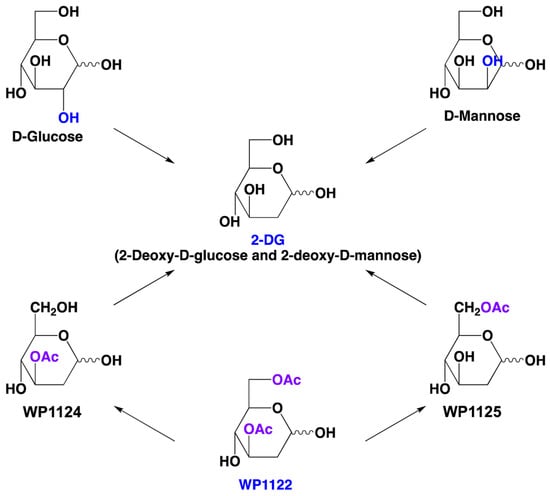

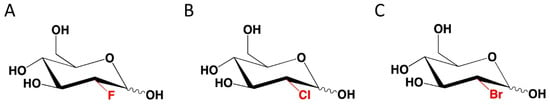

Nevertheless, the above-described poor pharmacokinetic properties and possible side effects encourage identification of other molecules that affect the same metabolic pathways but could overcome these problems. One possible solution is the use of novel 2-DG analogs, which maintain 2-DG-mediated biological efficacy, but have better drug-like properties, which is essential for successful clinical introduction.

7. Perspectives

The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic reminded societies globally of the importance of viral diseases in human health. The rapid spread of SARS-CoV-2 and its millions of infected patients have demonstrated the lack of effective broad-spectrum antiviral treatments. Moreover, as described above, other viral infections like HBV, HPV, HSV and ZIKV also have significant health, economic and worldwide significance. All of them generate a high demand for an effective therapy that reduces infections and protects patients from the long-term harmful consequences of viral diseases, including cancer patients. Activation of glycolysis in infected cells is the common link between various viral infections making inhibition of glycolysis a promising therapeutic approach for broad-spectrum drugs. As can be seen from the numerous studies described above, 2-DG exhibits effective antiviral activity against many types of viruses, including SARS-CoV-2. Recent clinical trials of 2-DG in SARS-CoV-2-infected patients support the strategy of targeting the metabolism of infected host cells as a way to limit virus growth and dissemination in infected host. However, based on the cited data on the effects of 2-DG clinical trials for oncological indications, including the reported side effects and poor pharmacokinetic properties, it seems that there is an unmet need to search for new molecules with an analogous mechanism of action but with significantly better drug-like properties.

In this light, molecules like WP1122 appear to have great potential for development as a drug candidate in antiviral indications. We look forward to the final reports of clinical trials with WP1122 in patients with COVID-19 or other viral infections of public health importance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.P., J.T.M., S.P., M.R.E., and W.P.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, B.P., R.Z., J.T.M., S.M., S.P., M.R.E. and W.P.; Writing—Review and Editing, B.P., R.Z., J.T.M., S.M., S.P., I.F., M.R.E. and W.P.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Preparation of this review did not receive external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

Moleculin Inc. partially finances research concerning molecular mechanisms of 2-DG analogs, including WP1122 action. W.P. is an inventor of patents covering new derivatives of 2-DG. He is the chair of SAB and a shareholder of Moleculin Biotech. Inc., CNS Pharmaceuticals, and WPD Pharmaceuticals. His research is in part supported by a sponsor research grant from Moleculin Biotech. Inc. and CNS Pharmaceuticals. M.E. is a shareholder of Moleculin Biotech. Inc., and his research is in part supported by a sponsor research grant from Moleculin Biotech. Inc. I.F. and R.Z. are listed as inventors on patents covering new analogs of 2-DG and are consultants of Moleculin Biotech., Inc., and are shareholders of Moleculin Biotech, Inc. and CNS Pharmaceuticals. B.P. is the CSO at WPD Pharmaceuticals. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- COVID Pandemic Data. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Template:COVID-19_pandemic_data (accessed on 14 July 2022).

- Lauer, S.A.; Grantz, K.H.; Bi, Q.; Bi, Q.; Jones, F.K.; Zheng, Q.; Meredith, H.R.; Azman, A.S.; Reich, N.G.; Lessler, J. The incubation period of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) from publicity reported confirmed cases: Estimation and application. Ann. Intern. Med. 2020, 172, 577–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, R.A.; Morales-Nebreda, L.; Markov, N.S.; Swaminathan, S.; Querrey, M.; Guzman, E.R.; Abbott, D.A.; Donnelly, H.K.; Donayre, A.; Goldberg, I.A.; et al. Circuits between infected macrophages and T cells in SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia. Nature 2021, 590, 635–641. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, M.C.; Reynoso, D.; Ren, P. The Brief Case: A fatal case of SARS-CoV-2 coinfection with Coccidioides in Texas—Another challenge we face. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2021, 59, e0016321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Q.; Lin, H.; Wei, R.G.; Chen, N.; He, F.; Zou, D.H.; Wei, J.R. Tocilizumab treatment for COVID-19 patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Infect. Dis. Poverty 2021, 10, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Gammeltoft, K.A.; Ryberg, L.A.; Pham, L.V.; Fahnøe, U.; Binderup, A.; Rene, C.; Hernandez, D.; Offersgaard, A.; Fernendez-Antunez, C.; et al. Nirmatrelvir resistant SARS-CoV-2 variants with high fitness in vitro. BioRxiv 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jochmans, D.; Liu, C.; Donckers, K.; Stoycheva, A.; Boland, S.; Stevens, S.K.; de Vita, C.; Vanmechelen, B.; Maes, P.; Trüeb, B.; et al. The substitutions L50F, E166A and L167F in SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro are selected by a protease inhibitor in vitro and confer resistance to nirmatrelvir. BioRxiv 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Defense, India. Available online: https://pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1717007 (accessed on 14 July 2022).

- Borana, R. Dr Reddy’s Revealed More about 2-DG, and Its Approval Is More Confusing Now. Available online: https://science.thewire.in/health/dr-reddys-doc-vidya-webinar-2-dg-clinical-trials-primary-endpoints-problems/ (accessed on 14 July 2022).

- Thaker, S.K.; Chang, J.; Christfolk, H.R. Viral hijacking of cellular metabolism. BMC Biol. 2019, 17, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenreich, W.; Rudel, T.; Heesemann, J.; Goebel, W. How viral and intracellular bacterial pathogens reprogram the metabolism of host cells to allow their intracellular replication. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2019, 9, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munger, J.; Bennett, B.D.; Parikh, A.; Feng, X.J.; McArdle, J.; Rabitz, H.A.; Shenk, T.; Rabinowitz, J.D. Systems-level metabolic flux profiling identifies fatty acid synthesis as a target for antiviral therapy. Nat. Biotechnol. 2008, 26, 1179–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vastag, L.; Koyuncu, E.; Grady, S.L.; Shenk, T.E.; Rabinowitz, J.D. Divergent effects of human cytomegalovirus and herpes simplex virus-1 on cellular metabolism. PLoS Pathog. 2011, 7, e1002124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thai, M.; Graham, N.A.; Braas, D.; Nehil, M.; Komisopoulou, E.; Kurdistani, S.K.; McCormick, F.; Graeber, T.G.; Christfolk, H.R. Adenovirus E4ORF1-induced MYC activation promotes host cell anabolic glucose metabolism and virus replication. Cell Metab. 2014, 19, 694–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, K.A.; Stockl, J.; Zlabinger, G.J.; Gualdoni, G.A. Hijacking the supplies: Metabolism as a novel facet of virus-host interaction. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1533. [Google Scholar]

- Warburg, O.; Wind, F.; Negelein, E. The metabolism of tumors in the body. J. Gen. Physol. 1927, 8, 519–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, J.R.; Sun, M.X.; Ni, B.; Huan, C.; Huang, L.; Li, C.; Fan, H.J.; Ren, X.F.; Mao, X. Triggering unfolded protein response by 2-Deoxy-D-glucose inhibits porcine epidemic diarrhea virus propagation. Antivir. Res. 2014, 106, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Icard, P.; Lincet, H.; Wu, Z.; Coquerel, A.; Forgez, P.; Alifano, M.; Fournel, L. The key role of Warburg effect in SARS-CoV-2 replication and associated inflammatory response. Biochimie 2021, 180, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibelini, L.; De Biasi., S.; Paolini, A.; Borella, R.; Boraldi, F.; Mattioli, M.; Lo Tartaro, D.; Fidanza, L.; Caro-Maldonado, A.; Quaglino, D.; et al. Altered bioenergetics and mitochondrial dysfunction of monocytes in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia. EMBO Mol. Med. 2020, 12, e13001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passalacqua, K.D.; Lu, J.; Goodfellow, I.; Kolawole, A.O.; Arche, J.R.; Maddox, R.J.; Carnahan, K.E.; O’Riordan, M.X.; Wobus, C.E. Glycolysis is an intrinsic factor for optimal replication of a norovirus. mBio 2019, 10, e02175-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontain, K.A.; Sanchez, E.L.; Camarda, R.; Lagunoff, M. Dengue virus induces and requires glycolysis for optimal replication. J. Virol. 2015, 89, 2358–2366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Maguire, T.G.; Alwine, J.C. Human cytomegalovirus activates glucose transporter 4 expression to increase glucose uptake during infection. J. Virol. 2011, 85, 1573–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramiere, C.; Rodriguez, J.; Enache, L.S.; Lotteau, V.; Andre, P.; Diaz, O. Activity of hexokinase is increased by its interaction with hepatitis C virus protein NS5A. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 3246–3254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrantes, J.L.; Alves, C.M.; Costa, J.; Almeida, F.C.L.; Sola-Penna, M.; Fontes, C.F.L.; Souza, T.M.L. Herpes simplex type 1 activates glycolysis through engagement of the enzyme 6-phoshofructo-1-kinase (PFK-1). Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2012, 1822, 1198–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manel, N.; Kim, F.J.; Kinet, S.; Taylor, N.; Sitbon, M.; Battini, J.L. The ubiquitous glucose transporter GLUT-1 is a receptor for HTLV. Cell 2003, 115, 449–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansouri, K.; Rastegari-Pouyani, M.; Ghanbri-Movahed, M.; Safarzadeh, M.; Kiani, S.; Ghanbari-Movahed, Z. Can a metabolism-targeted therapeutic intervention successfully subjugate SARS-COV-2? A scientific rationale. Biomed. Pharm. 2020, 131, 110694. [Google Scholar]

- Kindrachuk, J.; Ork, B.; Hart, B.J.; Mazur, S.; Holbrook, M.R.; Frieman, M.B.; Traynor, D.; Johnson, R.F.; Dyall, J.; Kuhn, J.H.; et al. Antiviral potential of ERK/MAPK and PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling modulation for Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection as identified by temporal kinome analysis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015, 59, 1088–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ripoli, M.; D’Aprile, A.; Quarato, G.; Sarasin-Filipowicz, M.; Gouttenoire, J.; Scrima, R.; Cela, O.; Boffoli, D.; Heim, M.H.; Moradpour, D.; et al. Hepatitic C virus-linked mitochondrial dysfunction promotes hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha-mediated glycolytic adaptation. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 647–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masson, J.J.; Billings, H.W.; Palmer, C.S. Metabolic reprogramming during hepatitis B disease progression offers novel diagnostic and therapeutic opportunities. Antivir. Chem. Chemother. 2017, 25, 53–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.H.; Yang, Y.; Chen, C.H.; Hsiao, C.J.; Li, T.N.; Liao, K.J.; Watashi, K.; Chen, B.S.; Wang, L.H.C. Aerobic glycolysis supports hepatitis B virus protein synthesis through interaction between viral surface antigen and pyruvate kinase isoform M2. PLoS Pathog. 2021, 17, e1008866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Lin, Y.; Kemper, T.; Chen, J.; Yuan, Z.; Liu, S.; Zhu, Y.; Broering, R.; Lu, M. AMPK and Akt/mTOR signalling pwathways participate in glucose-mediated regulation of the hepatitis B virus replication and cellular autophagy. Cell Microbiol. 2019, 22, e13131. [Google Scholar]

- Valle-Casuso, J.C.; Angin, M.; Volant, S.; Passaes, C.; Monceaux, V.; Mikhailova, A.; Bourdic, K.; Sitbon, M.; Lambotte, O.; Thoulouze, M.I.; et al. Cellular metabolism is a major determinant of HIV-1 reservoir seeding in CD4+ T cells and offers an opportunity to tackle infection. Cell Metab. 2019, 29, 611–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, C.S.; Ostrowski, M.; Gouillou, M.; Tsai, L.; Zhou, J.; Henstridge, D.C.; Maisa, A.; Hearps, A.C.; Lewin, S.R.; Landay, A.; et al. Increased glucose metabolic activity is associated with CD4+ T-cell activation and depletion during chronic HIV infection. AIDS 2014, 28, 297–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Bacha, T.; Menezes, M.M.; Azevedo e Silva, M.C.; Sola-Penna, M.; Da Poian, A.T. Mayaro virus infection alters glucose metabolism in cultured cells through activation of the enzyme 6-phosphofructo 1-kinase. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2004, 266, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Guo, X.; Wu, S.; Li, N.; Lin, Q.; Liu, L.; Liang, H.; Huang, Z.; Fu, X. Accelerated metabolite levels of aerobic glycolysis and the pentose phosphate pathway are required for efficient replication of infectious spleen and kidney necrosis virus in Chinese perch brain cells. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valdes, A.; Zhao, H.; Pettersson, U.; Bergstrom Lind, S. Time-resolved proteomics od adenovirus infected cells. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e204522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prusinkiewicz, M.A.; Mymryk, J.S. Metabolic reprogramming of the host cell by human adenovirus infection. Viruses 2019, 11, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez, E.L.; Pulliam, T.H.; Dimaio, T.A.; Thalhofer, A.B.; Delgado, T.; Lagunoff, M. Glycolysis, glutaminolysis, and fatty acid synthesis are required for distinct stages of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus lytic replication. J. Virol. 2017, 91, e02237-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gualdoni, G.A.; Mayer, K.A.; Kapsch, A.M.; Kreuzberg, K.; Puck, A.; Kienzl, P.; Oberndorfer, F.; Fruwirth, K.; Winkler, S.; Blaas, D.; et al. Rhinovirus induces an anabolic reprogramming in host cells metabolism essential for viral replication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E7158–E7165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritter, J.B.; Wahl, A.S.; Freund, S.; Genzel, Y.; Reichl, U. Metabolic effects of influenza virus infection in cultured animal cells; intra- and extracellular metabolite profiling. BMC Syst. Biol. 2010, 4, 61. [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Vincente, M.; Gonzalez-Riano, C.; Barbas, C.; Jimenez-Sousa, M.A.; Brochado-Kith, O.; Resino, S.; Martinez, I. Metabolic changes during respiratory syncytial virus infection of epithelial cells. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0230844. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, S.; Singh, P.K.; Suhail, H.; Arumugaswami, V.; Pellett, P.E.; Giri, S.; Kumar, A. AMP-activated protein kinase restricts Zika virus replication in endothelial cells by potentiating innate antiviral responses and inhibiting glycolysis. J. Immunol. 2020, 204, 1810–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigerust, D.J.; Shepherd, V.L. Virus glycosylation: Role in virulence and immune interactions. Trends Microbiol. 2007, 15, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantlo, E.K.; Maruyama, J.; Manning, J.T.; Wanninger, T.G.; Huang, C.; Smith, J.N.; Petterson, M.; Paessler, S.; Komab, T. Machupo virus with mutations in the transmembrane domain and glycosylation sites of the glycoprotein is attenuated and immunogenic in animal models of bolivian hemorrhagic fever. J. Virol. 2022, 96, e0020922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pieren, M.; Galli, C.; Denzel, A.; Molinari, M. The use of calnexin and calreticulin by cellular and viral glycoproteins. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 31, 28265–28271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Liu, D.; Wang, Y.; Su, W.; Liu, G.; Dong, W. The importance of glycans of viral and host proteins in enveloped virus infection. Front. Immunol. 2021, 21, 638573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koma, T.; Huang, C.; Coscia, A.; Hallam, S.; Manning, J.T.; Maruyama, J.; Walker, A.G.; Miller, M.; Smith, J.N.; Patterson, M.; et al. Glycoprotein N-linked glycans play a critical role in arenavirus pathogenicity. PLoS Pathog. 2021, 17, e1009356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, P.; Jang, Y.H.; Kwon, S.B.; Lee, C.M.; Han, G.; Seong, B.L. Glycosylation of hemagglutinin and neuraminidase of influenza virus as signature for ecological spillover and adaptation among influenza reservoirs. Viruses 2018, 10, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Upadhyay, C.; Feyznezhad, R.; Cao, L.; Chan, K.W.; Liu, K.; Yang, W.; Zhang, H.; Yolitz, J.; Arthos, J.; Nadas, A.; et al. Signal peptide of HIV-1 envelope modulates glycosylation impacting exposure of V1V2 and other epitopes. PLoS Pathog. 2020, 16, e1009185. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, V.; Freeze, H.H. Mannose efflux from the cells: A potential source of mannose in blood. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 10193–10200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeom, S.J.; Kim, Y.S.; Lim, Y.R.; Jeong, K.W.; Lee, J.Y.; Kim, Y.; Oh, D.K. Molecular characterization of a novel thermostable mannose-6-phosphate isomerase from Thermus thermophilus. Biochimie 2011, 93, 1659–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navale, A.M.; Paranjape, A.N. Glucose transporters: Physiological and pathological roles. Biophys. Rev. 2016, 8, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cura, A.J.; Carruthers, A. Role of monosaccharide transport proteins in carbohydrate assimilation, distribution, metabolism, and homeostasis. Compr. Physiol. 2012, 2, 863–914. [Google Scholar]

- Pajak, B.; Siwiak, E.; Sołtyka, M.; Priebe, A.; Zieliński, R.; Fokt, I.; Ziemniak, M.; Jaśkiewicz, A.; Borowski, R.; Domoradzki, T.; et al. 2-deoxy-D-glucose and its analogs: From diagnostic to therapeutic agents. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berthe, A.; Zano, M.; Muller, C.; Foulquier, F.; Houdou, M.; Schulz, C.; Bost, F.; De Fay, E.; Mazerbourg, S.; Flament, S. Protein N-glycosylation alteration and glycolysis inhibition both contribute to the antiproliferative action of 2-deoxyglucose in breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2018, 171, 581–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, Y.; Chang, Y.; Lu, W.; Sheng, X.; Wang, S.; Xu, H.; Ma, J. Regulation of autophagy by glycolysis in cancer. Cancer Manag. Res. 2020, 12, 13259–13271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szegezdi, E.; Logue, S.E.; Gorman, A.M.; Samali, A. Mediators of endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis. EMBO Rep. 2006, 7, 880–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorburn, A. Apoptosis and autophagy: Regulatory connections between two supposedly different processes. Apoptosis 2008, 13, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shutt, D.C.; O’Dorisio, S.M.; Aykin-Burns, N.; Spitz, D.R. 2-deoxy-D-glucose induces oxidative stress and cell killing in human neuroblastoma cells. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2010, 9, 853–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adrestani, A.; Azizi, Z. Targeting glucose metabolism for treatment of COVID-19. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 112. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt, A.N.; Kumar, A.; Rai, Y.; Kumari, N.; Vedagiri, D.; Harshan, K.H.; Kumar, V.C.; Chandna, S. Glycolytic inhibitor 2-Deoxy-D-glucose attenuates SARS-CoV-2 multiplication in host cells and weakens the infective potential of progeny virions. Life Sci. 2022, 295, 120411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojkova, D.; Klann, K.; Koch, B.; Widera, M.; Krause, M.; Ciesek, S.; Cinatl, J.; Munch, C. Proteomics of SARS-CoV-2-infected host cells reveals therapy targets. Nature 2020, 583, 469–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Codo, A.C.; Davanzo, G.G.; de Brito Monteiro, L.; de Souza, G.F.; Muraro, S.P.; Virgilio-da-Silva, J.V.; Prondoff, J.S.; Carregari, V.C.; Oliviera de Biagi Junior, C.A.; Crunfli, F.; et al. Elevated glucose levels favor SARS-CoV-2 infection and monocyte response through a HIF-1α/glycolysis-dependent axis. Cell Metab. 2020, 32, 437–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maehama, T.; Patzelt, A.; Lengert, M.; Hutter, J.; Kanazawa, K.; Hausen, H.; Rosl, F. Selective down-regulation of human papillomavirus transcription by 2-deoxyglucose. Int. J. Cancer 1998, 76, 639–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.T.; Ju, J.W.; Cho, J.W.; Hwang, E.S. Down-regulation of Sp1 activity through modulation of O-glycosylation by treatment with a low glucose mimetic, 2-deoxyglucose. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 51223–51231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, D.; Huang, Y.; Song, S. Inhibiting the HPV16 oncogene-mediated glycolysis sensitizes human cervical carcinoma cells to 5-fluorouracil. OncoTargets Ther. 2019, 12, 6711–6720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasche, M.; Urban, H.; Gallwas, J.; Grundker, C. HPV and other microbiota; who’s good and who’s bad: Effects of the microbial environment on the development of cervical cancer—A non-systematic review. Cells 2021, 10, 714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belov, L.; Tapparel, C. Rhinoviruses and respiratory enteroviruses: Not as simple as ABC. Viruses 2016, 8, 16. [Google Scholar]

- Shawa, I.T. Hepatitis B and C viruses; Rodrigo, L., Ed.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, T.J. Hepatitis B: The virus and disease. Hepatology 2009, 49, S13–S21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.C.; Chen, M.C.; Liu, S.; Callahan, V.M.; Bracci, N.R.; Lehman, C.W.; Dahal, B.; de la Fuente, C.; Lin, C.C.; Wang, T.T.; et al. Phloretin inhibits Zika virus infection by interfering with cellular glucose utilization. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2019, 54, 80–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, H.; Jiang, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Nie, M.; Xiao, N.; Wang, S.; Song, Z.; Ji, F.; Chang, Y.; et al. Aberrant NAD+ metabolism underlines Zika virus-induced microcephaly. Nature Metab. 2021, 3, 11109–11124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subak-Sharpe, J.H.; Dargan, D.J. HSV molecular biology: General aspects of herpes simplex virus molecular biology. Virus Genes 1998, 16, 239–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO Herpes Simplex Virus Fact Sheet. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/herpes-simplex-virus (accessed on 17 July 2022).

- Varanasi, S.K.; Donohoe, D.; Jaggi, U.; Rouse, B.T. Manipulating glucose metabolism during different stages of viral pathogenesis can have either detrimental or beneficial effects. J. Immunol. 2017, 199, 1748–1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knowles, R.W.; Person, S. Effects of 2-deoxyglucose, glucosamine and mannose on cell fusion and the glycoprotein of herpes simplex virus. J. Virol. 1976, 18, 644–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kern, E.R.; Glasgow, L.A.; Klein, R.J.; Friedman-Kien, A.E. Failure of 2-deoxy-D-glucose in the treatment of experimental cutaneous and genital infections due to herpes simplex virus. J. Infect. Dis. 1982, 146, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, W.M.; Arnett, G.; Drennen, D.J. Lack of efficacy of 2-deoxy-D-glucose in the treatment of experimental herpes genitalis in guinea pigs. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1982, 21, 513–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Y.; Diao, D.; Zhang, H.; Guo, Q.; Wu, X.; Song, Y.; Dang, C. High glucose-induced resistance to 5-fluorouracil in pancreatic cancer cells alleviated by 2-deoxy-d-glucose. Biomed. Rep. 2014, 2, 188–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansen, I.L.; Levy, M.M.; Kerr, D.S. The 2-deoxyglucose test as a supplement to fasting for detection of childhood hypoglycemia. Pediatric Res. 1984, 18, 359–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strandberg, A.Y.; Pienimaki, T.; Pitkala, K.H.; Tilvis, R.S.; Salomaa, V.V.; Strandberg, T.E. Comparison of normal fasting and one-hour glucose levels as predictors of future diabetes during a 34-year follow-up. Ann. Med. 2013, 45, 336–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, M.; Lin, H.; Jeyamohan, C.; Dvorzhinski, D.; Gounder, M.; Bray, K.; Eddy, S.; Goodin, S.; White, E.; DiPaola, R.S. Targeting tumor metabolism with 2-deoxyglucose in patients with castrate-resistant prostate cancer and advanced malignancies. Prostate 2010, 70, 1388–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burckhardt, D.; Stalder, G.A. Cardiac changes during 2-deoxy-D-glucose test. A study in patients with selective vagotomy and pyloroplasty. Digestion 1975, 12, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stalder, G.A.; Schultheiss, H.R.; Allgower, M. Use of 2-deoxy-D-glucose for testing completeness of vagotomy in man. Gastroenterology 1972, 63, 552–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raez, L.E.; Papadopoulos, K.; Ricart, A.D.; Chiorean, E.G.; Dipaola, R.S.; Stein, M.N.; Rocha Lima, C.M.; Schlesselman, J.J.; Tolba, K.; Langmuir, V.K.; et al. A phase I dose-escalation trial of 2-deoxy-d-glucose alone or combined with docetaxel in patients with advanced solid tumors. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2013, 71, 523–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Priebe, W.; Zielinski, R.; Fokt, I.; Felix, E.; Radjendirane, V.; Arumugam, J.; TaiKhuong, M.; Krasinski, M.; Skora, S. EXTH-07. Design and evaluation of WP1122, in inhibitor of glycolysis with increased CNS uptake. Neuro-Oncology 2018, 20, vi86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Keith, M.; Zielinski, R.; Walker, C.M.; Le Roux, L.; Priebe, W.; Bankson, J.A.; Schellingerhout, D. Hyperpolarized pyruvate MR spectroscopy depicts glycolytic inhibition in a mouse model of glioma. Radiology 2019, 293, 168–173. [Google Scholar]

- WP1122 Phase 1a Study. Available online: https://moleculin.com/ongoing-phase-1a-study-in-covid-19/ (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- Lampidis, T.J.; Kurtoglu, M.; Maher, J.C.; Liu, H.; Krishan, A.; Sheft, V.; Szymanski, S.; Fokt, I.; Rudnicki, W.R.; Ginalski, K.; et al. Efficacy of 2-halogen substituted D-glucose analogs in blocking glycolysis and killing “hypoxic tumor cells”. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2006, 58, 725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziemniak, M.; Zawadzka-Kazimierczuk, A.; Pawlędzio, S.; Malinska, M.; Sołtyka, M.; Trzybinski, D.; Kożmiński, W.; Skóra, S.; Zieliński, R.; Fokt, I.; et al. Experimental and computational studies on structure and energetic properties of halogen derivatives of 2-deoxy-D-glucose. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).