Rapid Full-Cycle Technique to Control Adulteration of Meat Products: Integration of Accelerated Sample Preparation, Recombinase Polymerase Amplification, and Test-Strip Detection

Abstract

1. Introduction

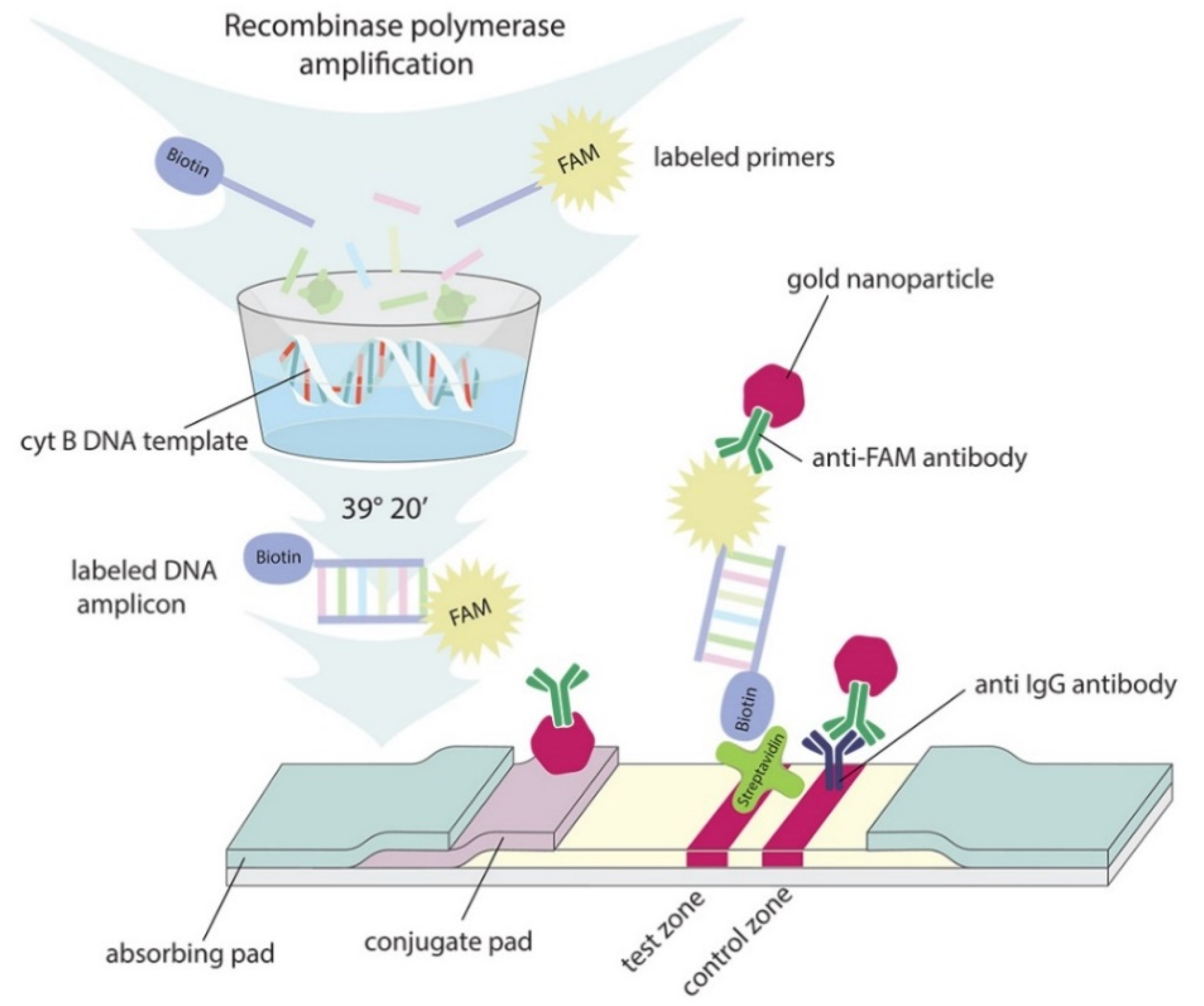

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Primer Design and Primary Verification by PCR

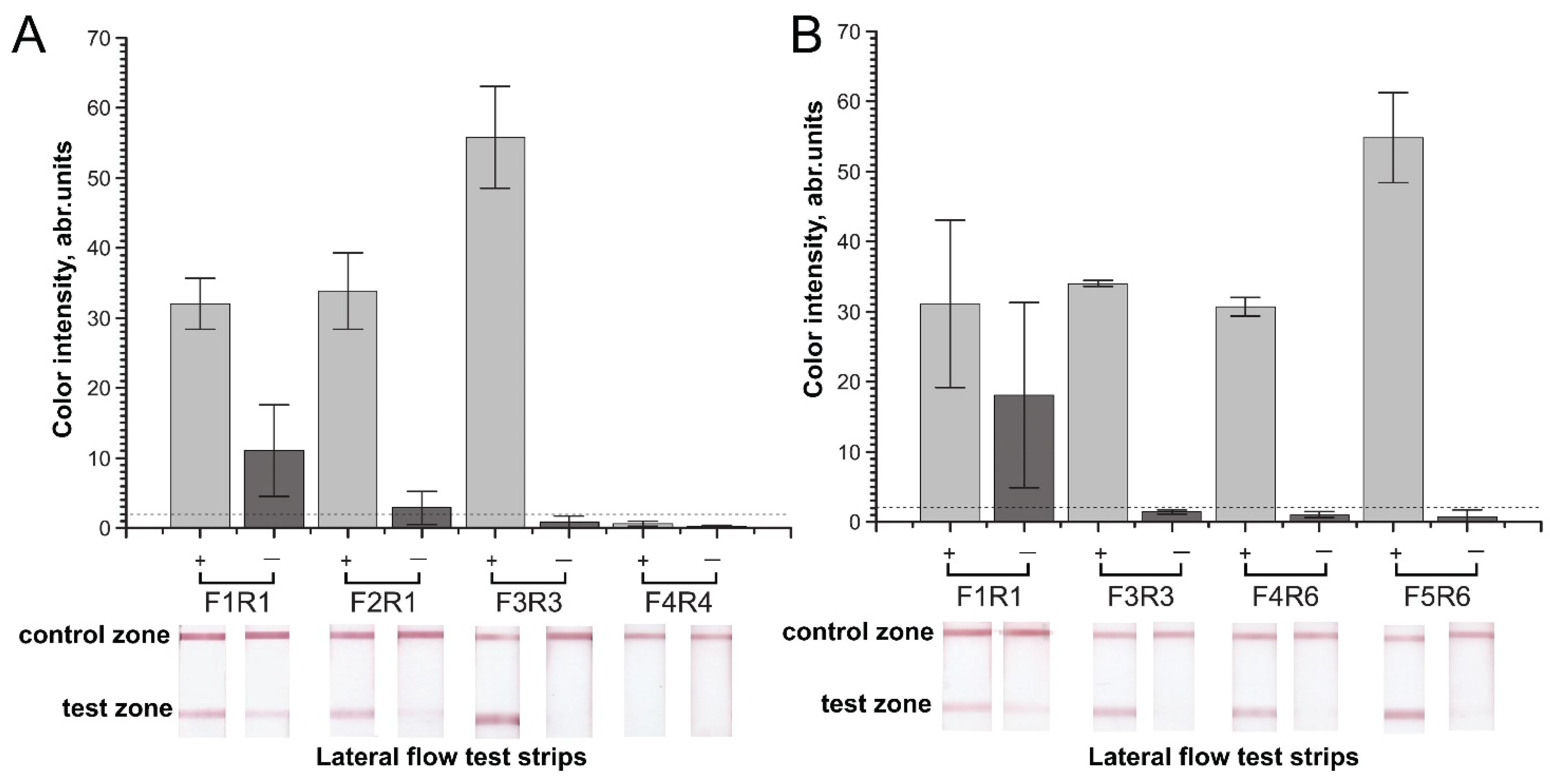

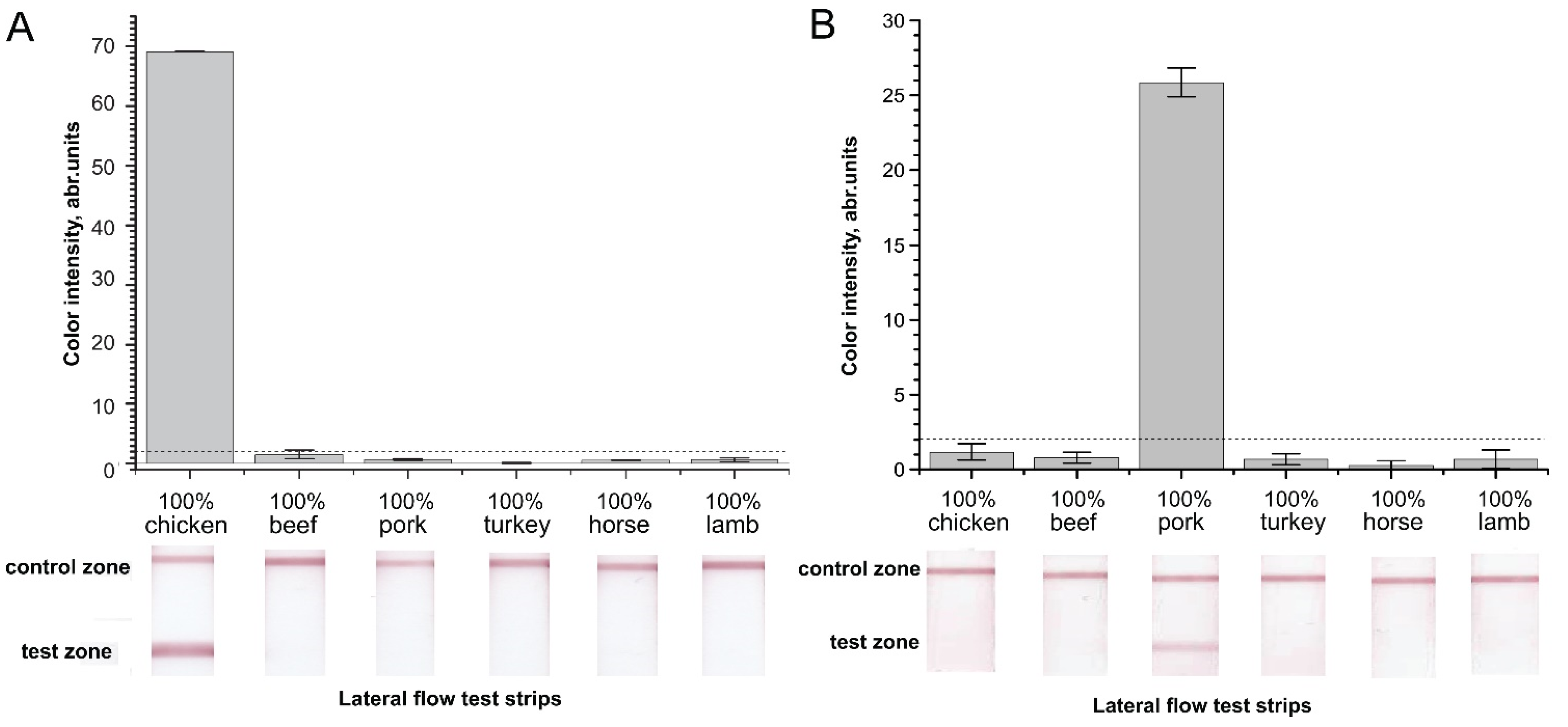

2.2. Verification of Designed Primers for the Specificity of RPA–LFA

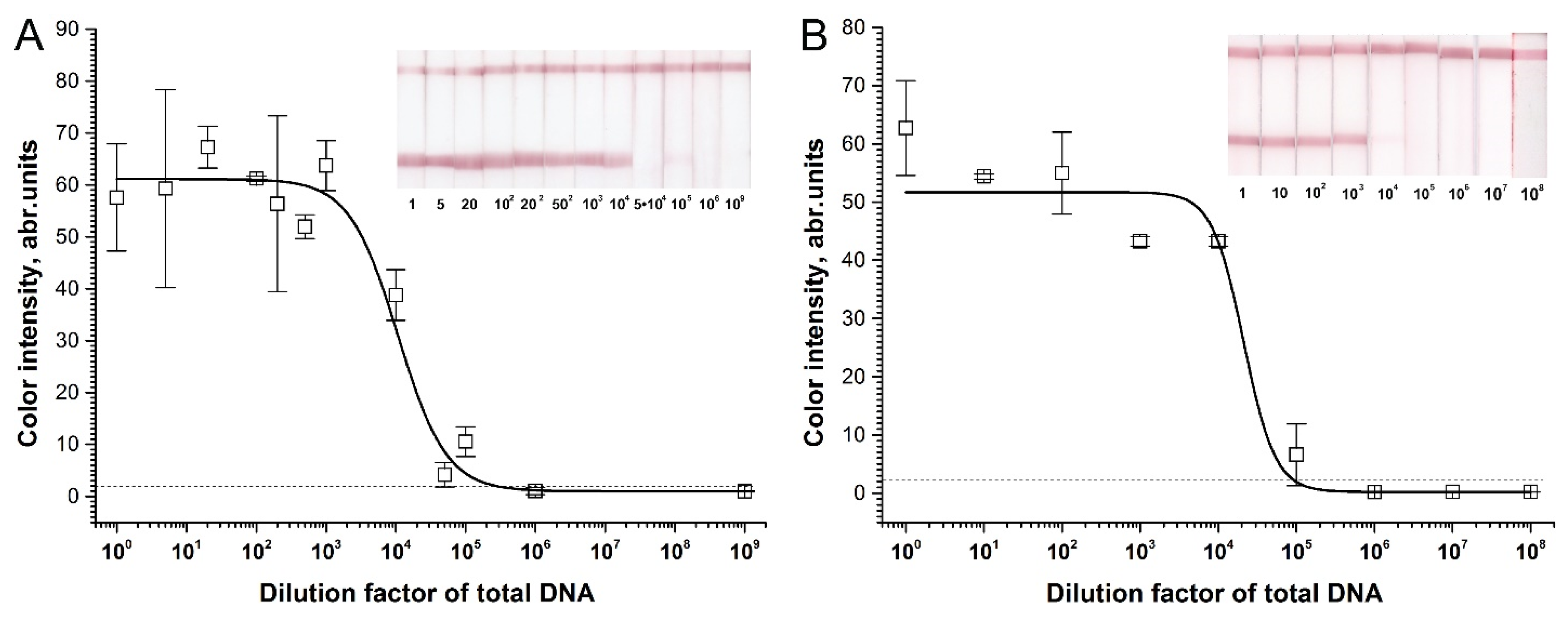

2.3. Sensitivity of RPA–LFA

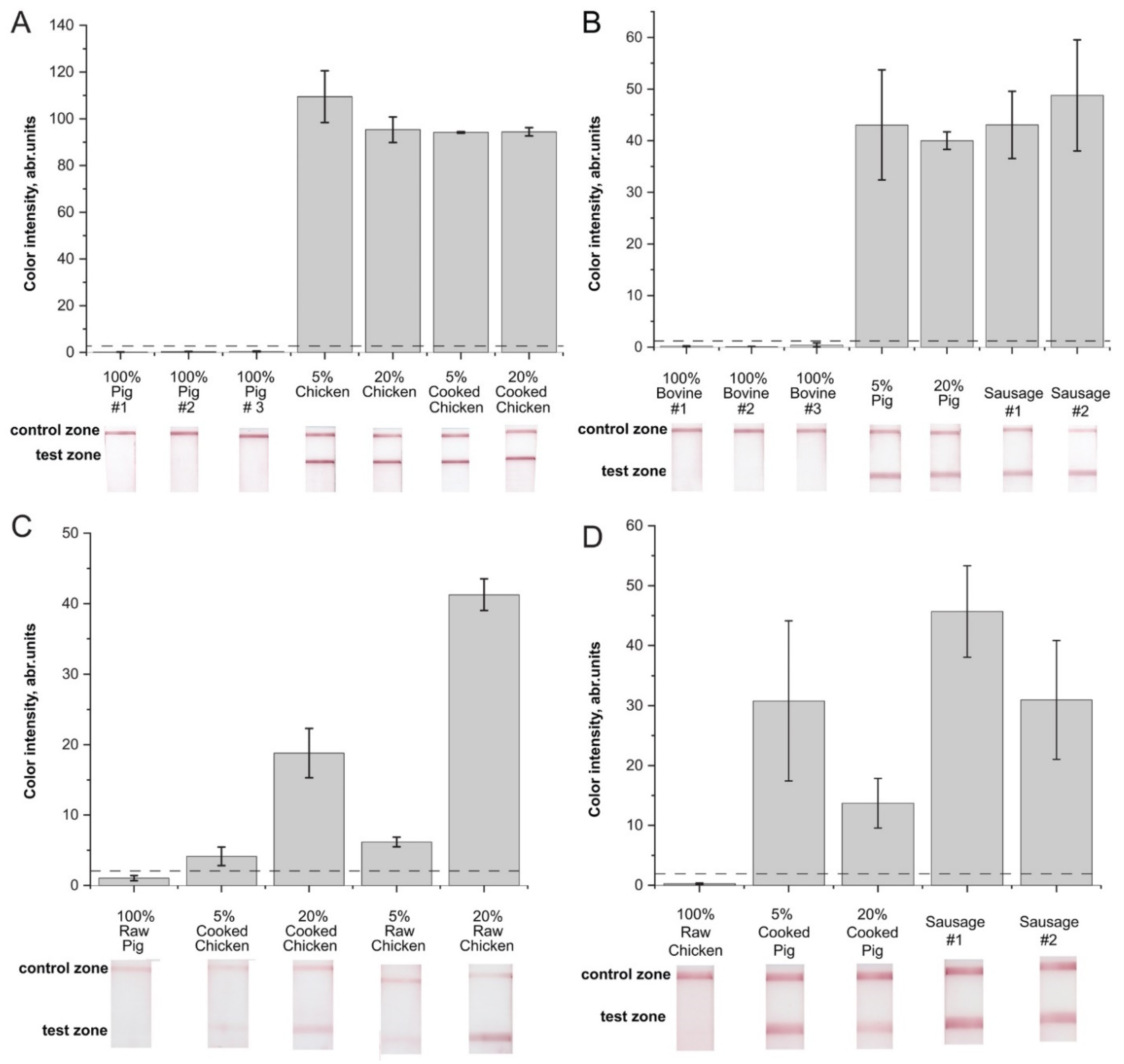

2.4. Verification of the RPA–LFA with Meat Samples

2.5. Comparison of the Developed Technique to Control Chicken or Pig Adulteration and Other RPA-Based Assays

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Reagents

3.2. Meat Samples

- Mix N1: 5% pig; 4.4% chicken; 90.6% bovine;

- Mix N2: 20% pig; 17.8% chicken; 62.2% bovine;

- Mix N3: 5% chicken muscle; 5% chicken skin; 90% pig;

- Mix N4: 20% chicken; 17.8% chicken skin; 62.2% pig.

- Additionally, mixes N3 and N4 were temperature-treated up to 72 °C. The sausages were of two types:

- Sausage N1, comprising 40% pig muscles, 25% pig fatback, and 35% bovine according to [65];

- Sausage N2, comprising 25% pig fatback and 75% bovine according to [66].

| Meat | Target Sequence | Sensitivity of DNA | Adulteration, % | Detection Method | Time of Amplification/Time of LFA | LoD of PCR | Extraction Method | Extraction Time, Min | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mangalica pig | Microsatellite locus | 0.17 ng/µL = 50 copies/reaction (1 copy/µL) | ND | LFA of RPA-nfo product | 30/5 | NA | Wizard® kit (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) ǁ DNAreleasy® (Nippon Genetics Europe, Düren, Germany) ǁ crude homogenization in water | >180 ǁ 15 ǁ <5 | [48] |

| Chicken | D-loop | 104 copies/µL = 20 pg total DNA/reaction | 1 | SYBR Green I coloration | 30 | 100 copies/µL | Universal Genomic kit (CWBIO, Taizhou, China) | 85–205 | [45] |

| Pig | 103 copies/µL = 20 pg total DNA/reaction | 1 | 100 copies/µL | ||||||

| Pig | ND2 | 1.23 pg total DNA/reaction = 10 copies/reaction | 0.1 | Real-time fluorescence by mobile equipment | 15 | NA | QIAamp® DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) | 20 | [44] |

| Pig | D-loop | 10 pg total pig DNA | 1 | Probe hybridization (with stage at 95 °C for 5 min) followed by LFA | 40/8 | DNeasy blood and tissue kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) | 20–60 | [46] | |

| Chicken | NDL4 | 10 copies (plasmid)/µL, 20 pg total DNA/µL | 1 | LFA of RPA-nfo product | 20/4 | Pos/neg test | gDNA extraction kit (Tiangen, Beijing, China) | 60 | [47] |

| Pig | ND1 | 10 copies (plasmid)/µL, 20 pg total DNA/µL | |||||||

| Chicken | Cyt B | 0.2 pg total DNA/µL = 20 copies/ µL | 5 | LFA of TwisDx basic products | 20/10 | 0.1 pg total DNA/µL | Salt method ǁ Crude homogenization | 120 ǁ <3 | This study |

| Pig | 0.2 pg total DNA/µL = 2 copies/µL | 0.1 pg total DNA/µL |

3.3. Meat Processing and DNA Extraction

3.4. Primer Design

3.5. Synthesis of Cytochrome b Genes

3.6. Quantitative Real-Time PCR

3.7. Preparation of Lateral Flow Test Strips

3.8. RPA–LFA Test

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Sample Availability

References

- Ballin, N.Z. Authentication of meat and meat products. Meat Sci. 2010, 86, 577–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bansal, S.; Singh, A.; Mangal, M.; Mangal, A.K.; Kumar, S. Food adulteration: Sources, health risks, and detection methods. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 57, 1174–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marvin, H.J.P.; Bouzembrak, Y.; Janssen, E.M.; van der Fels-Klerx, H.J.; van Asselt, E.D.; Kleter, G.A. A holistic approach to food safety risks: Food fraud as an example. Food Res. Int. 2016, 89, 463–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sentandreu, M.A.; Sentandreu, E. Authenticity of meat products: Tools against fraud. Food Res. Int. 2014, 60, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendall, H.; Clark, B.; Rhymer, C.; Kuznesof, S.; Hajslova, J.; Tomaniova, M.; Brereton, P.; Frewer, L. A systematic review of consumer perceptions of food fraud and authenticity: A European perspective. Trends Food Sci. Tech. 2019, 94, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spink, J.; Hegarty, P.V.; Fortin, N.D.; Elliott, C.T.; Moyer, D.C. The application of public policy theory to the emerging food fraud risk: Next steps. Trends Food Sci. Tech. 2019, 85, 116–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visciano, P.; Schirone, M. Food frauds: Global incidents and misleading situations. Trends Food Sci. Tech. 2021, 114, 424–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Mahony, P.J. Finding horse meat in beef products—A global problem. QJM 2013, 106, 595–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, S.; Elliott, C.T.; Spence, M.; Walsh, C.; Dean, M. Four years post-horsegate: An update of measures and actions put in place following the horsemeat incident of 2013. NPJ Sci. Food 2017, 1, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Premanandh, J.; Bin Salem, S. Progress and challenges associated with halal authentication of consumer packaged goods. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2017, 97, 4672–4678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zia, Q.; Alawami, M.; Mokhtar, N.F.K.; Nhari, R.; Hanish, I. Current analytical methods for porcine identification in meat and meat products. Food Chem. 2020, 324, 126664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.A.M.; Uddin, S.M.K.; Sultana, S.; Wahab, Y.A.; Sagadevan, S.; Johan, M.R.; Ali, M.E. Authentication of Halal and Kosher meat and meat products: Analytical approaches, current progresses and future prospects. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hendrickson, O.D.; Zvereva, E.A.; Dzantiev, B.B.; Zherdev, A.V. Sensitive lateral flow immunoassay for the detection of pork additives in raw and cooked meat products. Food Chem. 2021, 359, 129927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thienes, C.P.; Masiri, J.; Benoit, L.A.; Barrios-Lopez, B.; Samuel, S.A.; Meshgi, M.A.; Cox, D.P.; Dobritsa, A.P.; Nadala, C.; Samadpour, M. Quantitative detection of chicken and turkey contamination in cooked meat products by ELISA. J. AOAC Int. 2019, 102, 557–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Djurdievic, N.; Sheu, S.C.; Hsieh, Y.H.P. Quantitative detection of poultry in cooked meat products. J. Food Sci. 2005, 70, C586–C593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrickson, O.D.; Zvereva, E.A.; Vostrikova, N.L.; Chernukha, I.M.; Dzantiev, B.B.; Zherdev, A.V. Lateral flow immunoassay for sensitive detection of undeclared chicken meat in meat products. Food Chem. 2021, 344, 128598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteki, M.; Simal-Gandara, J.; Shahsavari, Z.; Zandbaaf, S.; Dashtaki, E.; Heyden, Y.V. A review on the application of chromatographic methods, coupled to chemometrics, for food authentication. Food Control 2018, 93, 165–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohme, K.; Calo-Mata, P.; Barros-Velazquez, J.; Ortea, I. Recent applications of omics-based technologies to main topics in food authentication. Trac-Trends Anal. Chem. 2019, 110, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stachniuk, A.; Sumara, A.; Montowska, M.; Fornal, E. Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry bottom-up proteomic methods in animal species analysis of processed meat for food authentication and the detection of adulterations. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 2021, 40, 3–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Zhong, P.; Jiang, A.M.; Shen, X.; Li, X.M.; Xu, Z.L.; Shen, Y.D.; Sun, Y.M.; Lei, H.T. Raman spectroscopy coupled with chemometrics for food authentication: A review. Trac-Trends Anal. Chem. 2020, 131, 116017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, K.; Manley, M.; Hoffman, L.C.; Williams, P.J. Non-destructive spectroscopic and imaging techniques for the detection of processed meat fraud. Foods 2021, 10, 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, Y.; Karne, S.C. Spectral analysis: A rapid tool for species detection in meat products. Trends Food Sci. Tech. 2017, 62, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreuders, F.K.G.; Schlangen, M.; Kyriakopoulou, K.; Boom, R.M.; van der Goot, A.J. Texture methods for evaluating meat and meat analogue structures: A review. Food Control 2021, 127, 108103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asensio, L.; Gonzalez, I.; Garcia, T.; Martin, R. Determination of food authenticity by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Food Control 2008, 19, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nhari, R.M.H.R.; Hanish, I.; Mokhtar, N.F.K.; Hamid, M.; El Sheikha, A.F. Authentication approach using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for detection of porcine substances. Qual. Assur. Saf. Crop. Foods 2019, 11, 449–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piglowski, M. Comparative analysis of notifications regarding mycotoxins in the Rapid Alert System for Food and Feed (RASFF). Qual. Assur. Saf. Crop. Foods 2019, 11, 725–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, Y.; Narsaiah, K. Rapid point-of-care testing methods/devices for meat species identification: A review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2021, 20, 900–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zvereva, E.A.; Popravko, D.S.; Hendrickson, O.D.; Vostrikova, N.L.; Chernukha, I.M.; Dzantiev, B.B.; Zherdev, A.V. Lateral flow immunoassay to detect the addition of beef, pork, lamb, and horse muscles in raw meat mixtures and finished meat products. Foods 2020, 9, 1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seddaoui, N.; Amine, A. Smartphone-based competitive immunoassay for quantitative on-site detection of meat adulteration. Talanta 2021, 230, 122346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohme, K.; Calo-Mata, P.; Barros-Velazquez, J.; Ortea, I. Review of recent DNA-based methods for main food-authentication topics. J. Agr. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 3854–3864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Kumar, R.R.; Sharma, B.D.; Gokulakrishnan, P.; Mendiratta, S.K.; Sharma, D. Identification of species origin of meat and meat products on the DNA basis: A review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2015, 55, 1340–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.E.; Razzak, M.A.; Abd Hamid, S.B. Multiplex PCR in species authentication: Probability and prospects—A review. Food Anal. Methods 2014, 7, 1933–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmati, S.; Julkapli, N.M.; Yehye, W.A.; Basirun, W.J. Identification of meat origin in food products—A review. Food Control 2016, 68, 379–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaral, J.S.; Santos, C.G.; Melo, V.S.; Oliveira, M.B.P.P.; Mafra, I. Authentication of a traditional game meat sausage (Alheira) by species-specific PCR assays to detect hare, rabbit, red deer, pork and cow meats. Food Res. Int. 2014, 60, 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, Y. Isothermal amplification-based methods for assessment of microbiological safety and authenticity of meat and meat products. Food Control 2021, 121, 107679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.Y.; Kim, M.J.; Hong, Y.; Kim, H.Y. Development of a rapid on-site detection method for pork in processed meat products using real-time loop-mediated isothermal amplification. Food Control 2016, 66, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, Y.; Bansal, S.; Jaiswal, P. Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification (LAMP): A Rapid and sensitive tool for quality assessment of meat products. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2017, 16, 1359–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.X.; Fu, S.J.; Peng, X.K.; Li, L.; Song, T.P.; Li, L. Identification of pork in meat products using real-time loop-mediated isothermal amplification. Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip. 2014, 28, 882–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb, R.; Sengar, G.S.; Singh, U.; Kumar, S.; Alyethodi, R.R.; Alex, R.; Raja, T.V.; Das, A.K.; Prakash, B. Application of a loop-mediated isothermal amplification assay for rapid detection of cow components adulterated in buffalo milk/meat. Mol. Biotechnol. 2016, 58, 850–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahradnik, C.; Martzy, R.; Mach, R.L.; Krska, R.; Farnleitner, A.H.; Brunner, K. Loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) for the detection of horse meat in meat and processed meat products. Food Anal. Meth. 2015, 8, 1576–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thangsunan, P.; Temisak, S.; Morris, P.; Rios-Solis, L.; Suree, N. Combination of loop-mediated isothermal amplification and aunp-oligoprobe colourimetric assay for pork authentication in processed meat products. Food Anal. Methods 2021, 14, 568–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jawla, J.; Kumar, R.R.; Mendiratta, S.K.; Agarwal, R.K.; Singh, P.; Saxena, V.; Kumari, S.; Boby, N.; Kumar, D.; Rana, P. On-site paper-based loop-mediated isothermal amplification coupled lateral flow assay for pig tissue identification targeting mitochondrial CO I gene. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2021, 102, 104036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Wu, X.; Xu, D.; Chen, L.; Ji, L. Identification of chicken-derived ingredients as adulterants using loop-mediated isothermal amplification. J. Food Prot. 2020, 83, 1175–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kissenkotter, J.; Bohlken-Fascher, S.; Forrest, M.S.; Piepenburg, O.; Czerny, C.P.; Abd El Wahed, A. Recombinase polymerase amplification assays for the identification of pork and horsemeat. Food Chem. 2020, 322, 126759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Y.; Zheng, K.; Jiang, J.; Wu, J.; Shi, F.; Song, X.; Jiang, Y. A novel method to detect meat adulteration by recombinase polymerase amplification and SYBR green I. Food Chem. 2018, 266, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, D.; Kumar, R.R.; Rana, P.; Mendiratta, S.K.; Agarwal, R.K.; Singh, P.; Kumari, S.; Jawla, J. On point identification of species origin of food animals by recombinase polymerase amplification-lateral flow (RPA-LF) assay targeting mitochondrial gene sequences. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 58, 1286–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, L.; Zheng, Y.; Huang, H.; Zhuang, F.; Chen, H.; Zha, G.; Yang, P.; Wang, Z.; Kong, M.; Wei, H.; et al. A visual method to detect meat adulteration by recombinase polymerase amplification combined with lateral flow dipstick. Food Chem. 2021, 354, 129526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szanto-Egesz, R.; Janosi, A.; Mohr, A.; Szalai, G.; Szabo, E.K.; Micsinai, A.; Sipos, R.; Ratky, J.; Anton, I.; Zsolnai, A. Breed-specific detection of mangalica meat in food products. Food Anal. Methods 2016, 9, 889–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.T.; Jalbani, Y.M.; Zhang, G.L.; Zhao, Z.Y.; Wang, Z.Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, X.Y.; Chen, A.L. Rapid authentication of mutton products by recombinase polymerase amplification coupled with lateral flow dipsticks. Sens. Actuators B-Chem. 2019, 290, 242–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, M.; Zhang, Q.; Zhou, X.; Liu, B. Recombinase polymerase amplification based multiplex lateral flow dipstick for fast identification of duck ingredient in adulterated beef. Animals 2020, 10, 1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Xu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, X.; Yang, Q.; Zhang, W. Saltatory rolling circle amplification (SRCA) for sensitive visual detection of horsemeat adulteration in beef products. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2021, 247, 2667–2676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhang, P.S.; Wang, H.X.; Shi, Y.J. Identification for adulteration of beef with chicken based on single primer-triggered isothermal amplification. Int. J. Food Eng. 2021, 17, 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajima, K.; Enishi, O.; Amari, M.; Mitsumori, M.; Kajikawa, H.; Kurihara, M.; Yanai, S.; Matsui, H.; Yasue, H.; Mitsuhashi, T.; et al. PCR detection of DNAs of animal origin in feed by primers based on sequences of short and long interspersed repetitive elements. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2002, 66, 2247–2250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Wang, R.F.; Myers, M.J.; Campbell, W.; Cao, W.W.; Paine, D.; Cerniglia, C.E. A rapid method for PCR detection of bovine materials in animal feedstuffs. Mol. Cell. Probes 2000, 14, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robin, E.D.; Wong, R. Mitochondrial DNA molecules and virtual number of mitochondria per cell in mammalian cells. J. Cell. Physiol. 1988, 136, 507–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyes, C.D.; Mathieu-Costello, O.A.; Tsuchiya, N.; Filburn, C.; Hansford, R.G. Mitochondrial biogenesis during cellular differentiation. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 1997, 272, C1345–C1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delp, M.D.; Duan, C. Composition and size of type I, IIA, IID/X, and IIB fibers and citrate synthase activity of rat muscle. J. Appl. Physiol. 1996, 80, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baharum, S.N.; Nurdalila, A.A. Application of 16s rDNA and cytochrome b ribosomal markers in studies of lineage and fish populations structure of aquatic species. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2012, 39, 5225–5232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, L.; Liu, J.; Jiang, Y.; Guo, W.; Wei, P.; Bai, L. Specific PCR method for detection of species origin in biochemical drugs via primers for the ATPase 8 gene by electrophoresis. Mikrochim. Acta 2019, 186, 634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellagamba, F.; Valfre, F.; Panseri, S.; Moretti, V.M. Polymerase chain reaction-based analysis to detect terrestrial animal protein in fish meal. J. Food Prot. 2003, 66, 682–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalsecco, L.S.; Palhares, R.M.; Oliveira, P.C.; Teixeira, L.V.; Drummond, M.G.; de Oliveira, D.A.A. A fast and reliable real-time PCR method for detection of ten animal species in meat products. J. Food Sci. 2018, 83, 258–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.C.; Liu, S.Y.; Meng, F.B.; Liu, D.Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, W.; Zhang, J.M. Comparative review and the recent progress in detection technologies of meat product adulteration. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2020, 19, 2256–2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russian State Standard GOST R 31719-2012. Foodstuffs and Feed. Rapid Method of Identification of Raw Composition (Molecular). 2012. Available online: https://docs.cntd.ru/document/1200098767 (accessed on 10 November 2021).

- Sakalar, E.; Abasiyanik, M.F.; Bektik, E.; Tayyrov, A. Effect of heat processing on DNA quantification of meat species. J. Food Sci. 2012, 77, 40–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.Y.; Jia, Q.J.; Yang, C.H.; Qiao, R.R.; Jing, L.H.; Wang, L.B.; Xu, C.L.; Gao, M.Y. Lateral flow immunochromatographic assay for sensitive pesticide detection by using Fe3O4 nanoparticle aggregates as color reagents. Anal. Chem. 2011, 83, 6778–6784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russian State Standard GOST R 55455-2013. Boiled-Smoked Meat Sausages. Specifications. 2013. Available online: https://docs.cntd.ru/document/1200107171 (accessed on 10 November 2021).

- Yalçınkaya, B.; Yumbul, E.; Mozioğlu, E.; Akgoz, M. Comparison of DNA extraction methods for meat analysis. Food Chem. 2017, 221, 1253–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frens, G. Controlled Nucleation for the Regulation of the Particle Size in Monodisperse Gold Suspensions. Nat. Phys. Sci. 1973, 241, 20–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safenkova, I.V.; Ivanov, A.V.; Slutskaya, E.S.; Samokhvalov, A.V.; Zherdev, A.V.; Dzantiev, B.B. Key significance of DNA-target size in lateral flow assay coupled with recombinase polymerase amplification. Anal. Chim. Acta 2020, 1102, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Species | Name | Sequences (5′ to 3′) | Length | Modification of 5′ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Galus galus | F1c | TCACATCGGACGAGGCCTA | 19 | Biotin |

| R1c | GGAATGGGGTGAGTATGAGAGTT | 23 | FAM | |

| F2c | TCACATCGGACGAGGCCTATACTAC | 25 | Biotin | |

| F3c | CCTATTAGCAGTCTGCCTCATGACC | 25 | Biotin | |

| R3c | GAGGCGCCGTTTGCGTGGAGATTCC | 25 | FAM | |

| F4c | CTTCAAAGACATTCTGGGCTTAACTC | 26 | Biotin | |

| R4c | ATTTTGTTTTCTAGTGTTCCGATTGT | 26 | FAM | |

| Sus scrofa | F1p | GACCTCCCAGCTCCATCAAACATCTCATCATGATGAAA | 38 | Biotin |

| R1p | GCTGATAGTAGATTTGTGATGACCGTA | 27 | FAM | |

| F2p | AACAACAGCTTTCTCATCAGTTACA | 25 | Biotin | |

| F3p | AAATTACGGATGAGTTATTCGCTATC | 26 | Biotin | |

| R3p | GTGCAGGAATATGAGATGTACGGCT | 25 | FAM | |

| F4p | AAAGACATTCTAGGAGCCTTATTTA | 25 | Biotin | |

| R4p | TAGGATGGAGGCTACTAGGGCCAAC | 25 | FAM | |

| F5p | AGCCTCCATCCTAATCCTAATTTTA | 25 | Biotin | |

| R6p | ATAGGTTGTTTTCGATGATGCTAGTG | 26 | FAM |

| Chicken (G. galus) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1c | F2c | F3c | F4c | ||

| R1c | 431 | 431 | 614 | 44 | |

| R3c | NA | NA | 159 | NA | |

| R4c | 840 | 840 | 1023 | 453 | |

| Pig (S. scrofa) | |||||

| F1p | F2p | F3p | F4p | F5p | |

| R1p | 348 | 279 | 273 | NA | NA |

| R3p | 546 | 427 | 385 | NA | NA |

| R4p | 840 | 721 | 679 | 219 | NA |

| R6p | 107 | 953 | 911 | 415 | 246 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ivanov, A.V.; Popravko, D.S.; Safenkova, I.V.; Zvereva, E.A.; Dzantiev, B.B.; Zherdev, A.V. Rapid Full-Cycle Technique to Control Adulteration of Meat Products: Integration of Accelerated Sample Preparation, Recombinase Polymerase Amplification, and Test-Strip Detection. Molecules 2021, 26, 6804. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26226804

Ivanov AV, Popravko DS, Safenkova IV, Zvereva EA, Dzantiev BB, Zherdev AV. Rapid Full-Cycle Technique to Control Adulteration of Meat Products: Integration of Accelerated Sample Preparation, Recombinase Polymerase Amplification, and Test-Strip Detection. Molecules. 2021; 26(22):6804. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26226804

Chicago/Turabian StyleIvanov, Aleksandr V., Demid S. Popravko, Irina V. Safenkova, Elena A. Zvereva, Boris B. Dzantiev, and Anatoly V. Zherdev. 2021. "Rapid Full-Cycle Technique to Control Adulteration of Meat Products: Integration of Accelerated Sample Preparation, Recombinase Polymerase Amplification, and Test-Strip Detection" Molecules 26, no. 22: 6804. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26226804

APA StyleIvanov, A. V., Popravko, D. S., Safenkova, I. V., Zvereva, E. A., Dzantiev, B. B., & Zherdev, A. V. (2021). Rapid Full-Cycle Technique to Control Adulteration of Meat Products: Integration of Accelerated Sample Preparation, Recombinase Polymerase Amplification, and Test-Strip Detection. Molecules, 26(22), 6804. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26226804