(−)-6-epi-Artemisinin, a Natural Stereoisomer of (+)-Artemisinin in the Opposite Enantiomeric Series, from the Endemic Madagascar Plant Saldinia proboscidea, an Atypical Source

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Extraction and Structure Elucidation

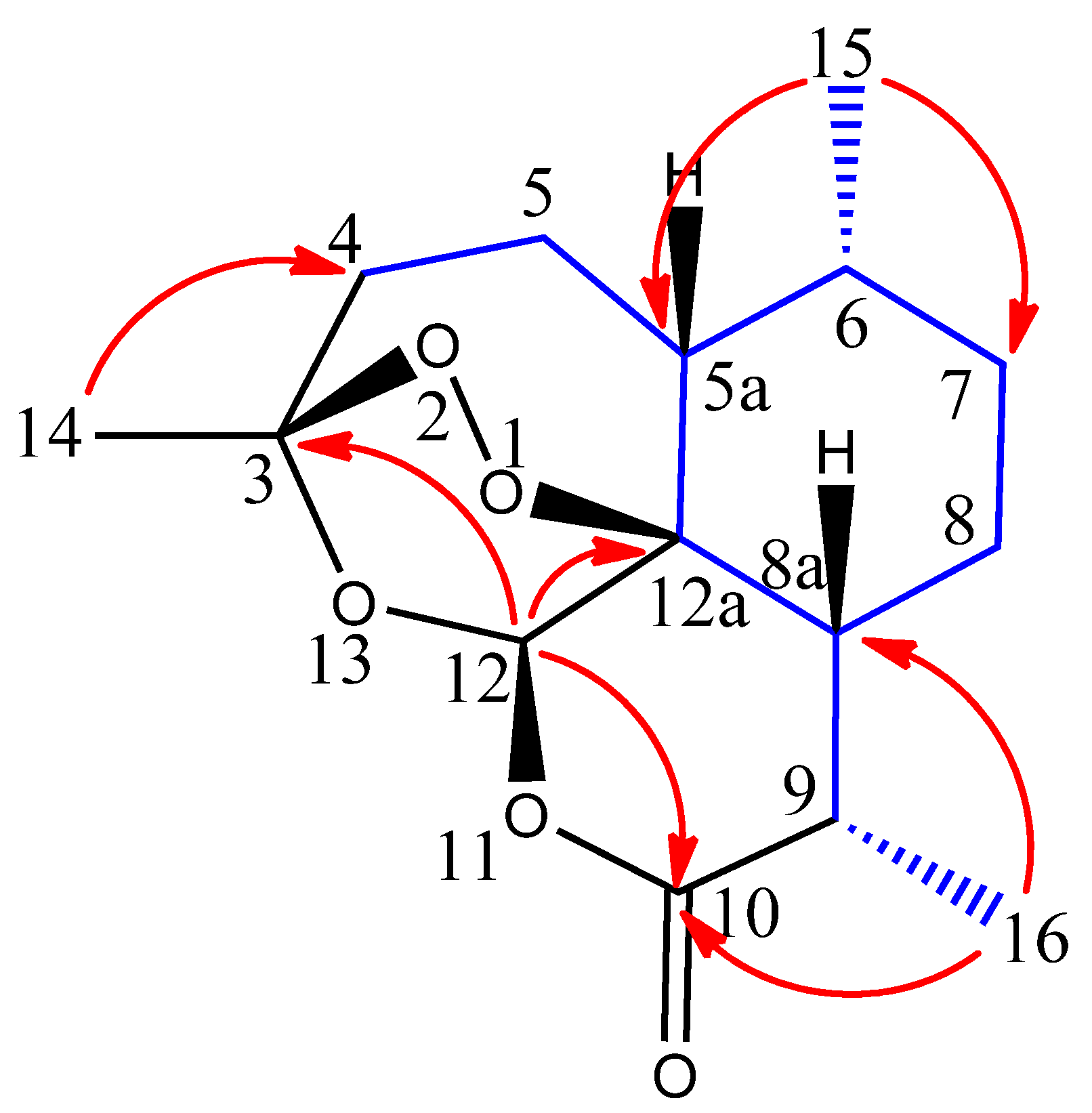

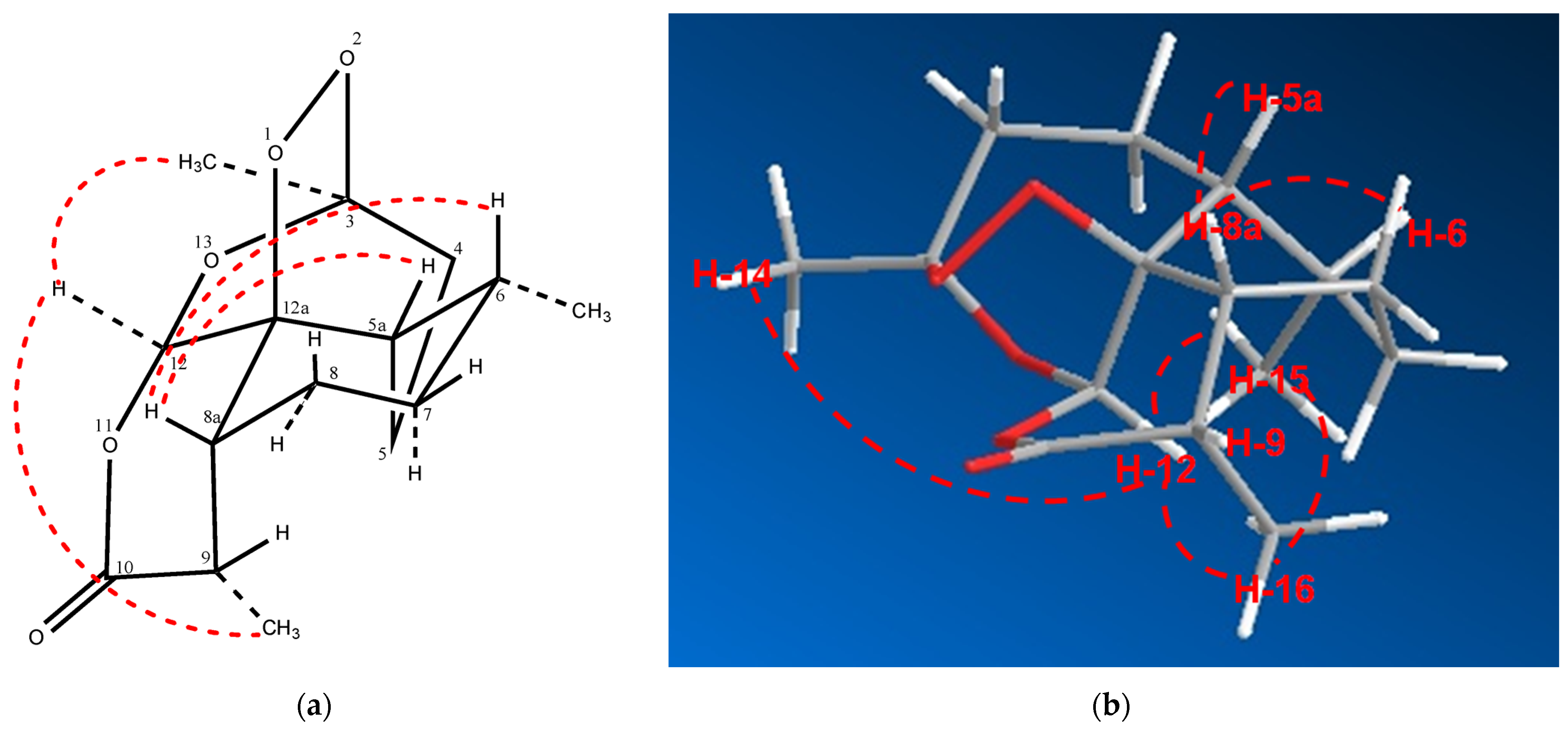

2.2. Relative Configuration of (−)-6-epi-Artemisinin (2) by ROESY Data Analyses

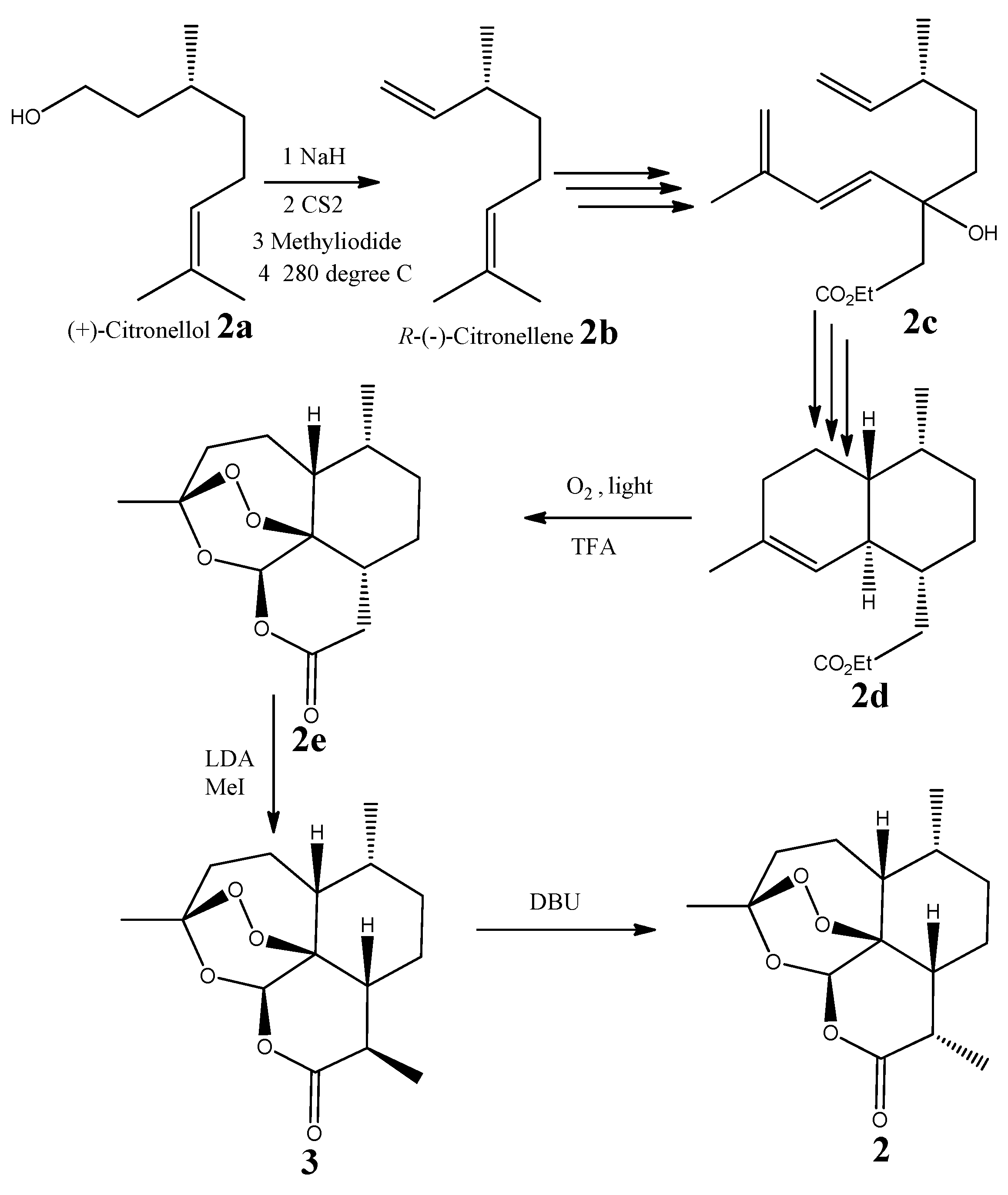

2.3. Absolute Configuration of (−)-6-epi-Artemisinin (2) by Chemical Syntheses

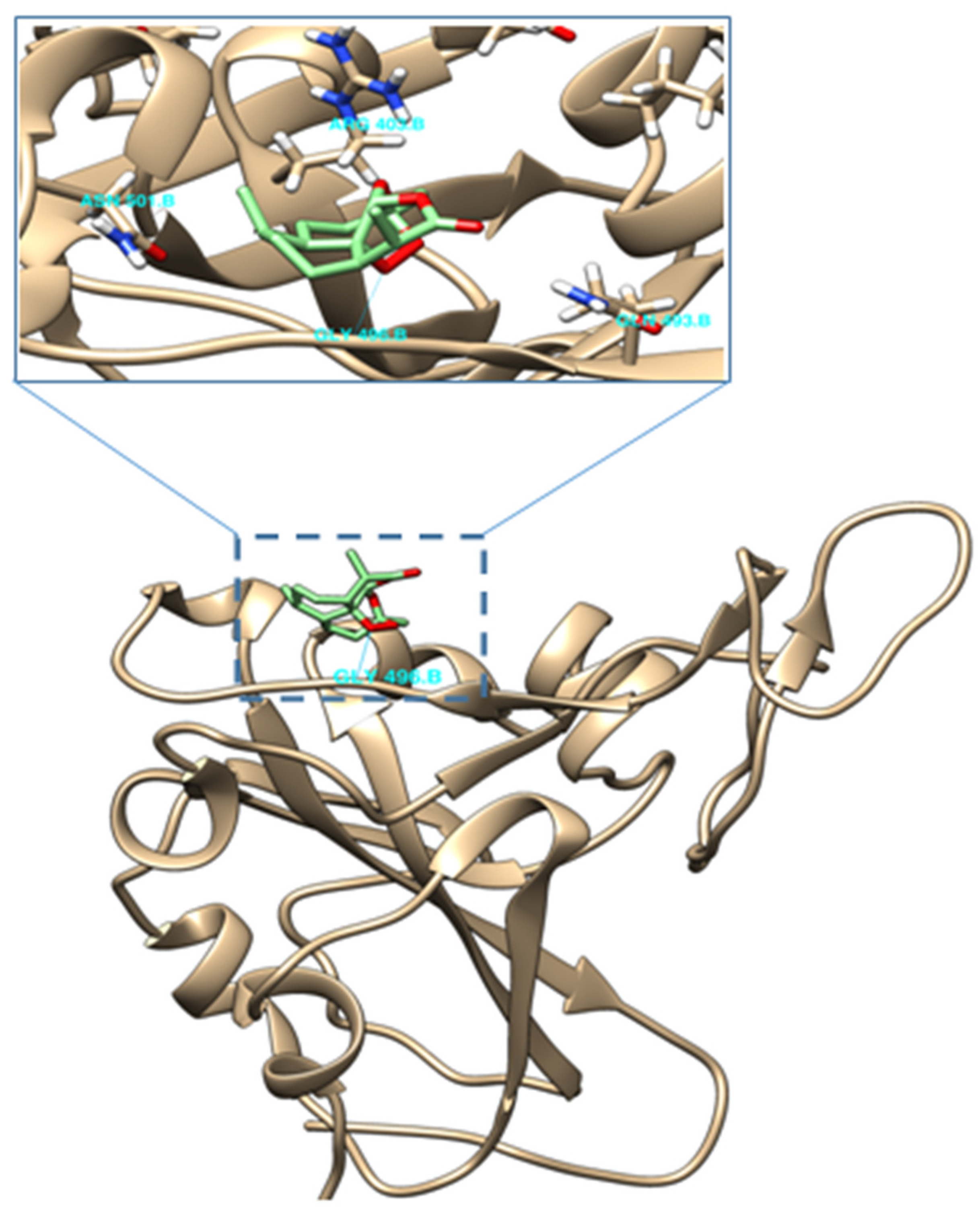

2.4. Molecular Docking of (−)-6-epi-Artemisinin (2) with the RBM of Spike Protein of SARS-CoV-2

2.5. Biological Activities

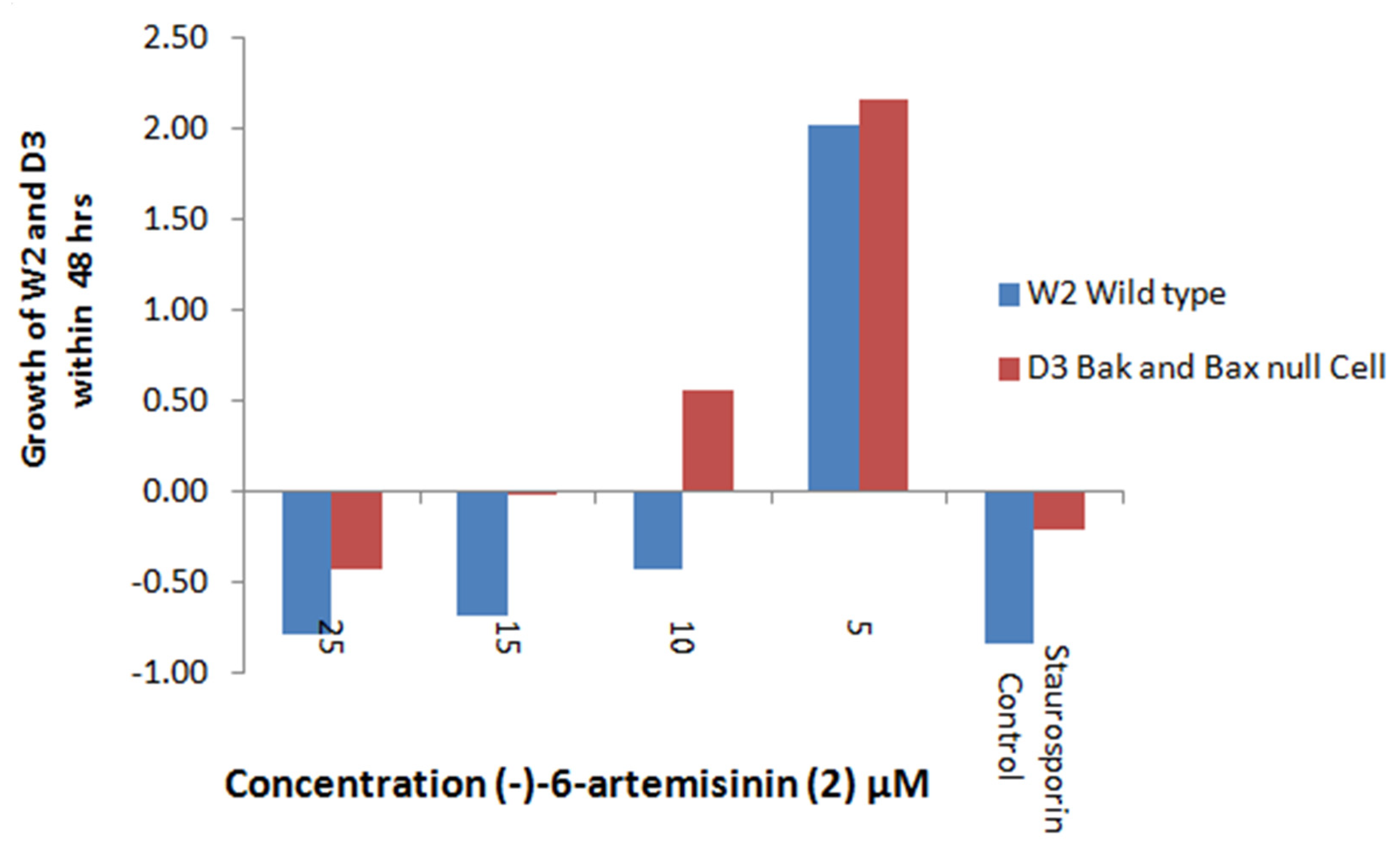

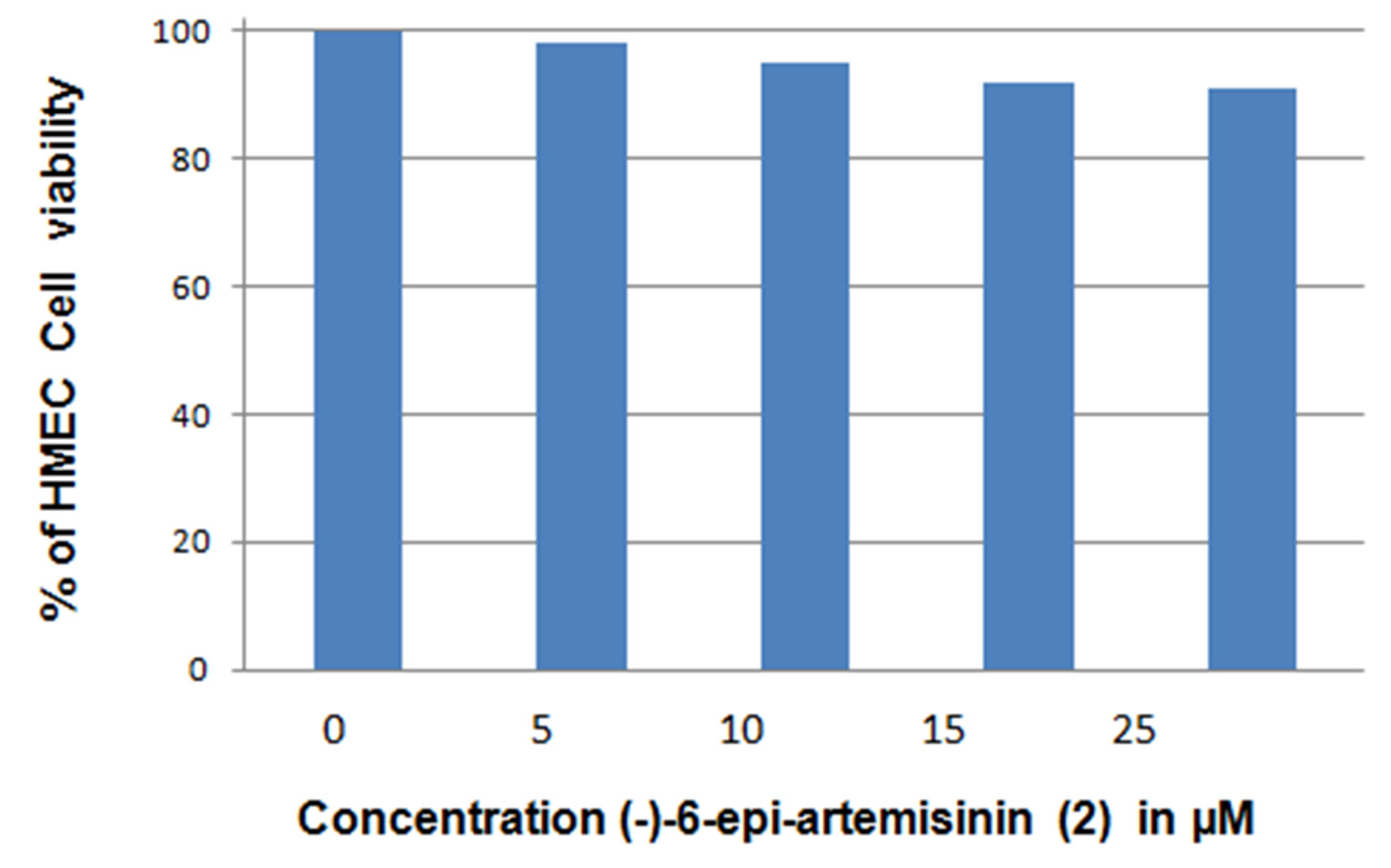

2.5.1. Apoptosis Induction

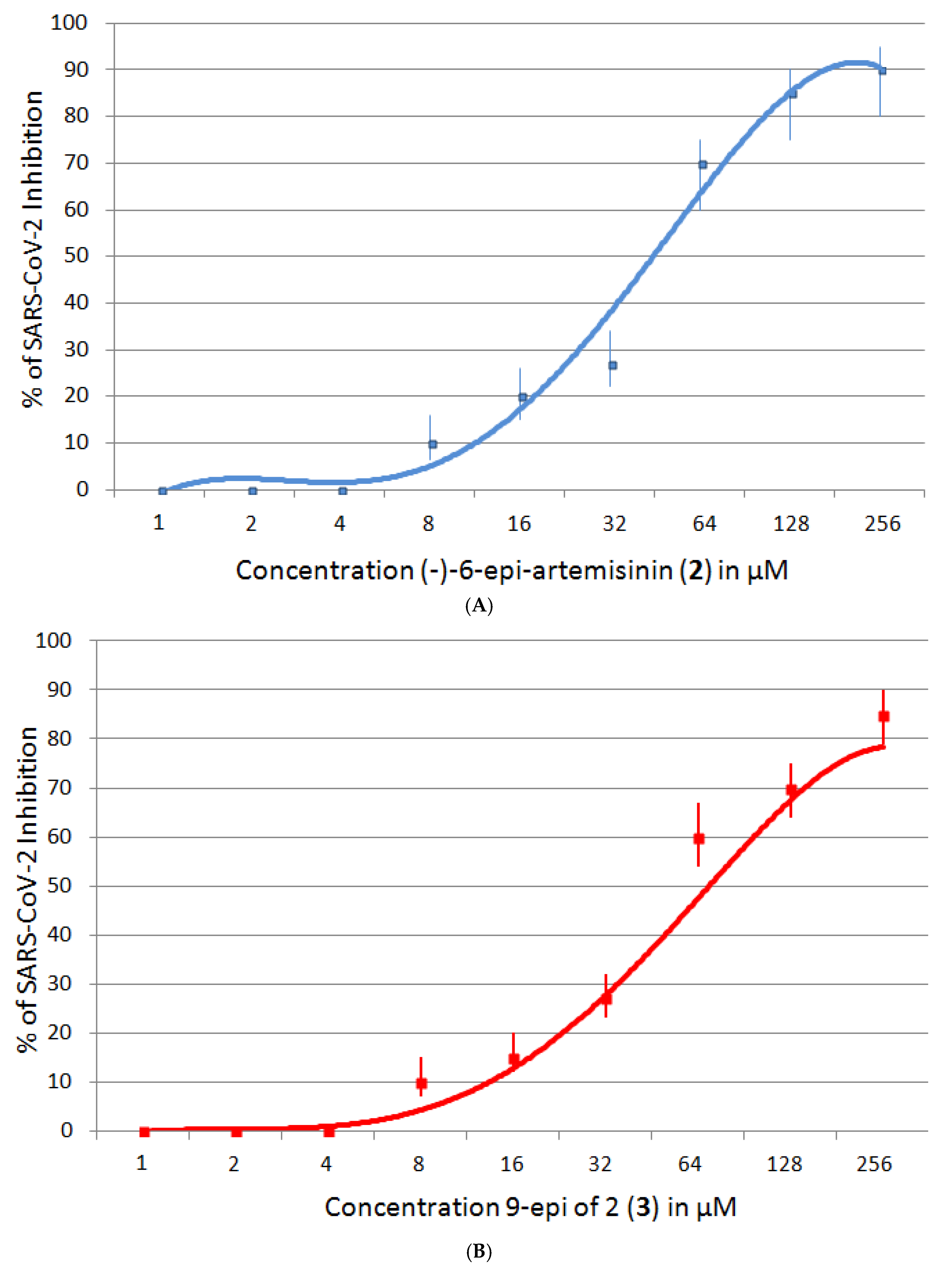

2.5.2. SARS-CoV-2 Inhibition

2.5.3. Antimalaria Assay

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. General Experimental Procedures

4.2. Extraction and Isolation Procedures

4.3. Molecular Docking

4.4. Biological Evaluation—Apoptosis Induction

4.5. Biological Evaluation—SARS-CoV-2 Inhibition

4.6. Biological Evaluation—Antimalaria Assay

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Sample Availability

References

- Arendt, P.; Miettinen, K.; Pollier, J.; De Rycke, R.; Callewaert, N.; Goossens, A. An endoplasmic reticulum-engineered yeast platform for overproduction of triterpenoids. Metab. Eng. 2017, 40, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kung, S.H.; Lund, S.; Murarka, A.; McPhee, D.; Paddon, C.J. Approaches and Recent Developments for the Commercial Production of Semi-synthetic Artemisinin. Front. Plant. Sc. 2018, 9, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Brown, G.D. The Biosynthesis of Artemisinin (Qinghaosu) and the Phytochemistry of Artemisia annua L. (Qinghao). Molecules 2010, 15, 7603–7698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Peterková, L.; Kmoníčková, E.; Ruml, T.; Rimpelová, S. Sarco/Endoplasmic Reticulum Calcium ATPase Inhibitors: Beyond Anticancer Perspective. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63, 1937–1963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Li, Q.; Wu, J.; Wang, M.; Yu, J. Artemisinin and Its Derivatives as a Repurposing Anticancer Agent: What Else Do We Need to Do? Molecules 2016, 21, 1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, R.; Hu, H.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Xu, M.; Liu, J.; Zhang, H.; Yan, Y.; Zhao, L.; Li, W.; et al. Anti-SARS-CoV-2 Potential of Artemisinins In Vitro. ACS Infect. Dis. 2020, 6, 2524–2531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krieger, J.; Smeilus, T.; Kaiser, M.; Seo, E.; Efferth, T.; Giannis, A. Total Synthesis and Biological Investigation of (−)-Artemisinin: The Antimalarial Activity of Artemisinin Is not Stereospecific. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 8293–8296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sehailia, M.; Chemat, S. Antimalarial-agent artemisinin and derivatives portray more potent binding to Lys353 and Lys31-binding hotspots of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein than hydroxychloroquine: Potential repurposing of artenimol for COVID-J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2020, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suberu, J.O.; Romero-Canelon, I.; Sullivan, N.; Lapkin, A.A.; Barker, G.C. Comparative Cytotoxicity of Artemisinin and Cisplatin and Their Interactions with Chlorogenic Acids in MCF7 Breast Cancer Cells. ChemMedChem 2014, 9, 2791–2797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lu, J.-J.; Meng, L.-H.; Cai, Y.-J.; Chen, Q.; Tong, L.-J. Dihydroartemisinin induces apoptosis in HL-60 leukemia cells de-pendent of iron and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase activation but independent of reactive oxygen species. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2008, 7, 1017–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Andrianasolo, E.H.; Haramaty, L.; Degenhardt, K.; Mathew, R.; White, E.; Lutz, R.; Falkowski, P. Induction of Apoptosis by Diterpenes from the Soft CoralXenia elongata. J. Nat. Prod. 2007, 70, 1551–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Andrianasolo, E.H.; Haramaty, L.; White, E.; Lutz, R.; Falkowski, P. Mode of Action of Diterpene and Characterization of Related Metabolites from the Soft Coral, Xenia elongata. Mar. Drugs 2014, 12, 1102–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Basilico, N.; Pagani, E.; Monti, D.; Olliaro, P.; Taramelli, D. A microtitre-based method for measuring the haem polymerization inhibitory activity (HPIA) of antimalarial drugs. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 1998, 42, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pellicera, J.; Saslis-Lagoudakisb, H.; Carrióc, E.; Ernstb, M.; Garnatjed, T.; Gracea, O.M.; Grasc, A.; Mumbrúe, M.; Vallèsc, J.; Vitalesd, D.; et al. A phylogenetic road map to antimalarial Artemisia species. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2018, 225, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, W.; Balta, V.A.; West, R.; Newlin, K.; Miljanic, O.S.; Sullivan, D.J.; Vekilov, P.G.; Rimer, J.D. A second mechanism employed by artemisinins to suppress Plasmodium falciparum hinges on inhibition of hematin crystallization. J. Biol. Chem. 2021, 296, 100123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pettersen, E.F.; Goddard, T.D.; Huang, C.C.; Couch, G.S.; Greenblatt, D.M.; Meng, E.C.; Ferrin, T.E. UCSF Chimera-a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 2004, 25, 1605–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Trott, O.; Olson, A.J. AutoDock Vina: Improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J. Comput. Chem. 2009, 31, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Position | δC, Type | δH, (J in Hz) | HMBC 1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 106.8, qC | ||

| 4α | 37.3, CH2 | 2.41, m | 3, 5, 12 |

| 4β | 2.09, m | 5a | |

| 5α | 24.8, CH2 | 1.90, m | 5a, 6 |

| 5β | 1.10, m | 4, 3 | |

| 5a | 51.4, CH | 1.38, m | 6, 12, 15 |

| 6 | 38.9, CH | 1.42, m | 5a, 7, 15 |

| 7α | 34.3, CH2 | 1.10, m | 6 |

| 7β | 1.81, m | 8 | |

| 8α | 26.6, CH2 | 2.00, m | 7, 8a |

| 8β | 2.00, m | 7 | |

| 8a | 46.4, CH | 1.80, m | 8, 9 |

| 9 | 35.0, CH | 3.41, dq (7.2, 5.3) | 10, 12, 12a |

| 10 | 173.4, qC | ||

| 12 | 95.1, CH | 5.89, s | 3, 10, 12a |

| 12a | 80.9, qC | ||

| 14 | 26.2, CH3 | 1.46, s | 4, 12 |

| 15 | 21.2, CH3 | 1.01, d (5.96) | 5a, 6, 7 |

| 16 | 13.9, CH3 | 1.22, d (7.28) | 9, 8a, 10 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Randrianarivo, S.; Rasolohery, C.; Rafanomezantsoa, S.; Randriamampionona, H.; Haramaty, L.; Rafanomezantsoa, R.M.; Andrianasolo, E.H. (−)-6-epi-Artemisinin, a Natural Stereoisomer of (+)-Artemisinin in the Opposite Enantiomeric Series, from the Endemic Madagascar Plant Saldinia proboscidea, an Atypical Source. Molecules 2021, 26, 5540. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26185540

Randrianarivo S, Rasolohery C, Rafanomezantsoa S, Randriamampionona H, Haramaty L, Rafanomezantsoa RM, Andrianasolo EH. (−)-6-epi-Artemisinin, a Natural Stereoisomer of (+)-Artemisinin in the Opposite Enantiomeric Series, from the Endemic Madagascar Plant Saldinia proboscidea, an Atypical Source. Molecules. 2021; 26(18):5540. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26185540

Chicago/Turabian StyleRandrianarivo, Saholinirina, Claudine Rasolohery, Sitraka Rafanomezantsoa, Heriniaina Randriamampionona, Liti Haramaty, Roger Marie Rafanomezantsoa, and Eric H. Andrianasolo. 2021. "(−)-6-epi-Artemisinin, a Natural Stereoisomer of (+)-Artemisinin in the Opposite Enantiomeric Series, from the Endemic Madagascar Plant Saldinia proboscidea, an Atypical Source" Molecules 26, no. 18: 5540. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26185540

APA StyleRandrianarivo, S., Rasolohery, C., Rafanomezantsoa, S., Randriamampionona, H., Haramaty, L., Rafanomezantsoa, R. M., & Andrianasolo, E. H. (2021). (−)-6-epi-Artemisinin, a Natural Stereoisomer of (+)-Artemisinin in the Opposite Enantiomeric Series, from the Endemic Madagascar Plant Saldinia proboscidea, an Atypical Source. Molecules, 26(18), 5540. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26185540