A Critical Review on Pulsed Electric Field: A Novel Technology for the Extraction of Phytoconstituents

Abstract

1. Introduction

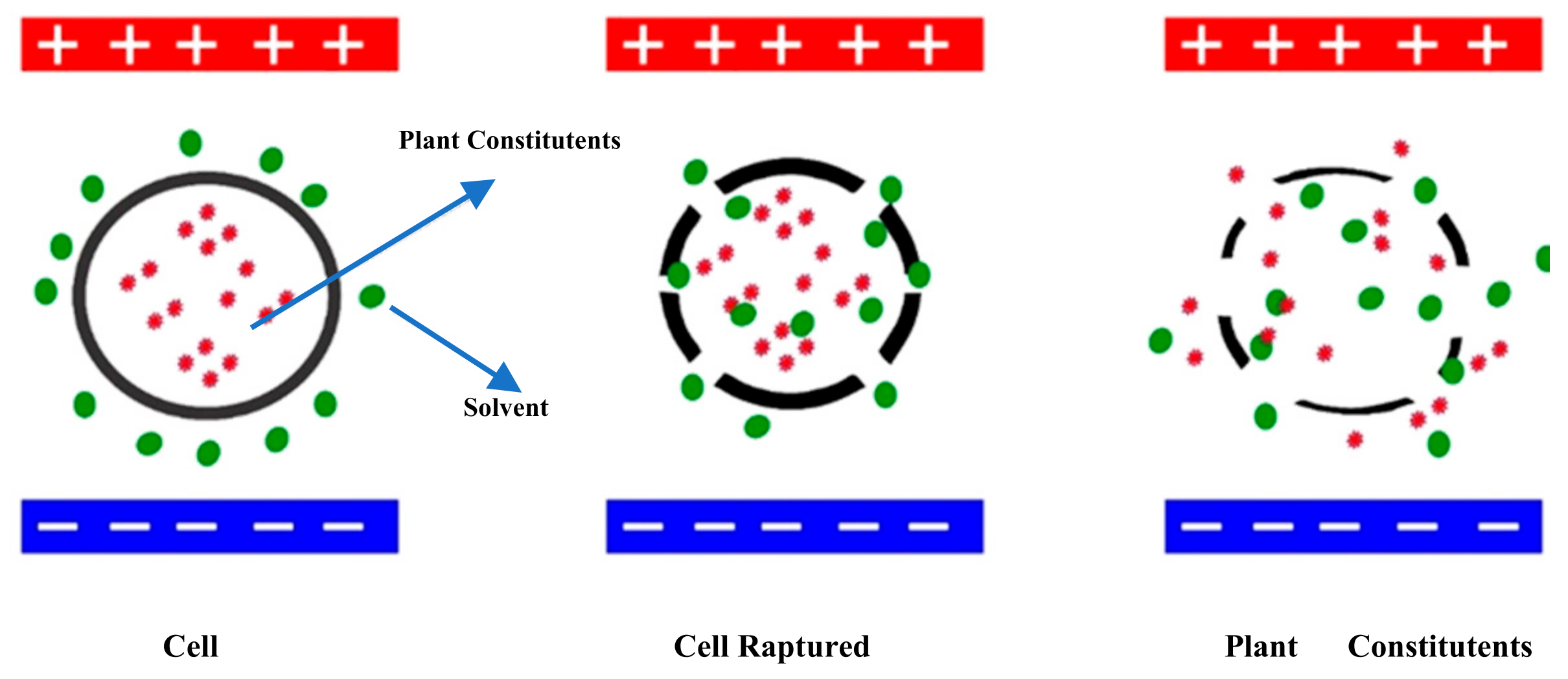

2. Working Principle of PEF-Assisted Extraction

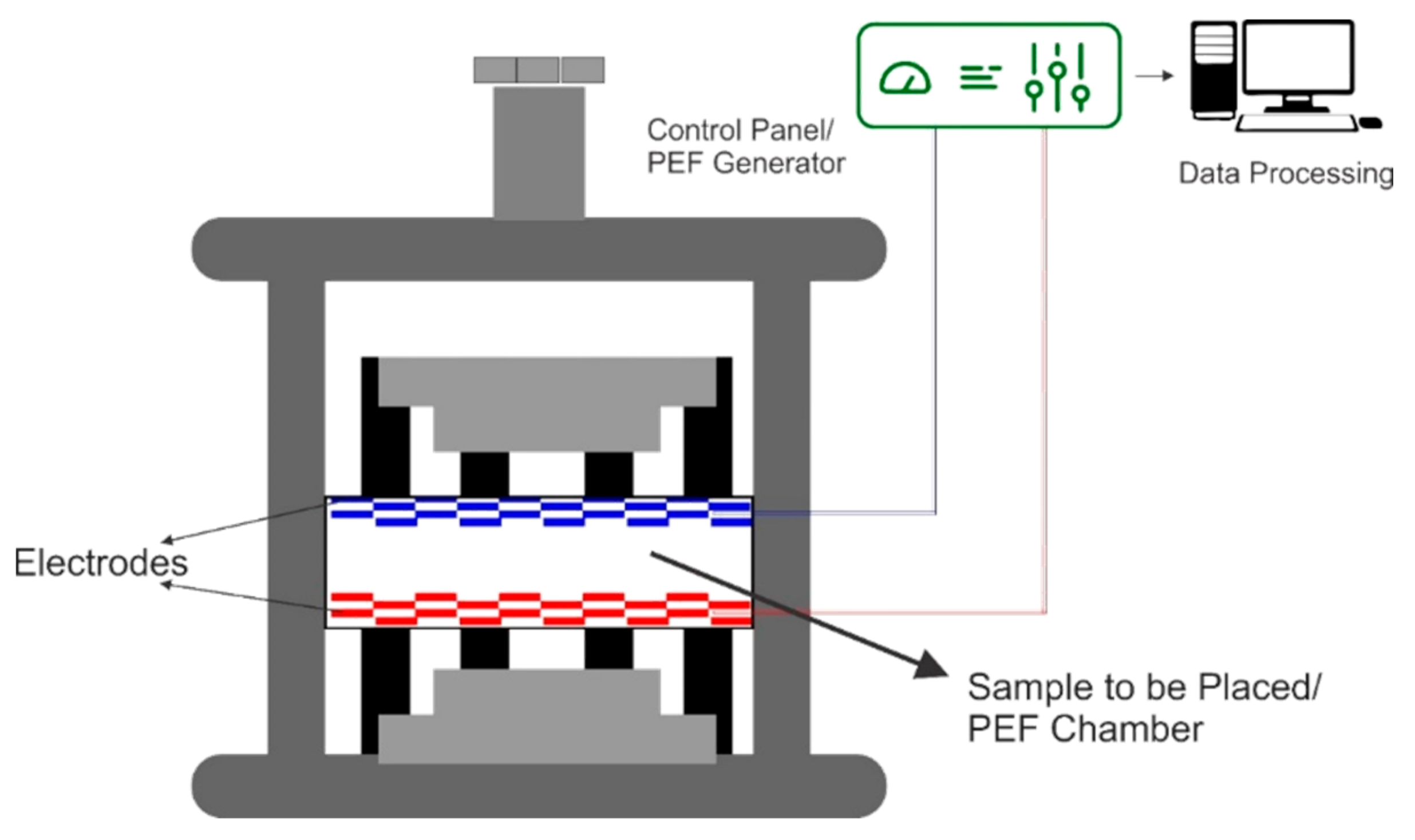

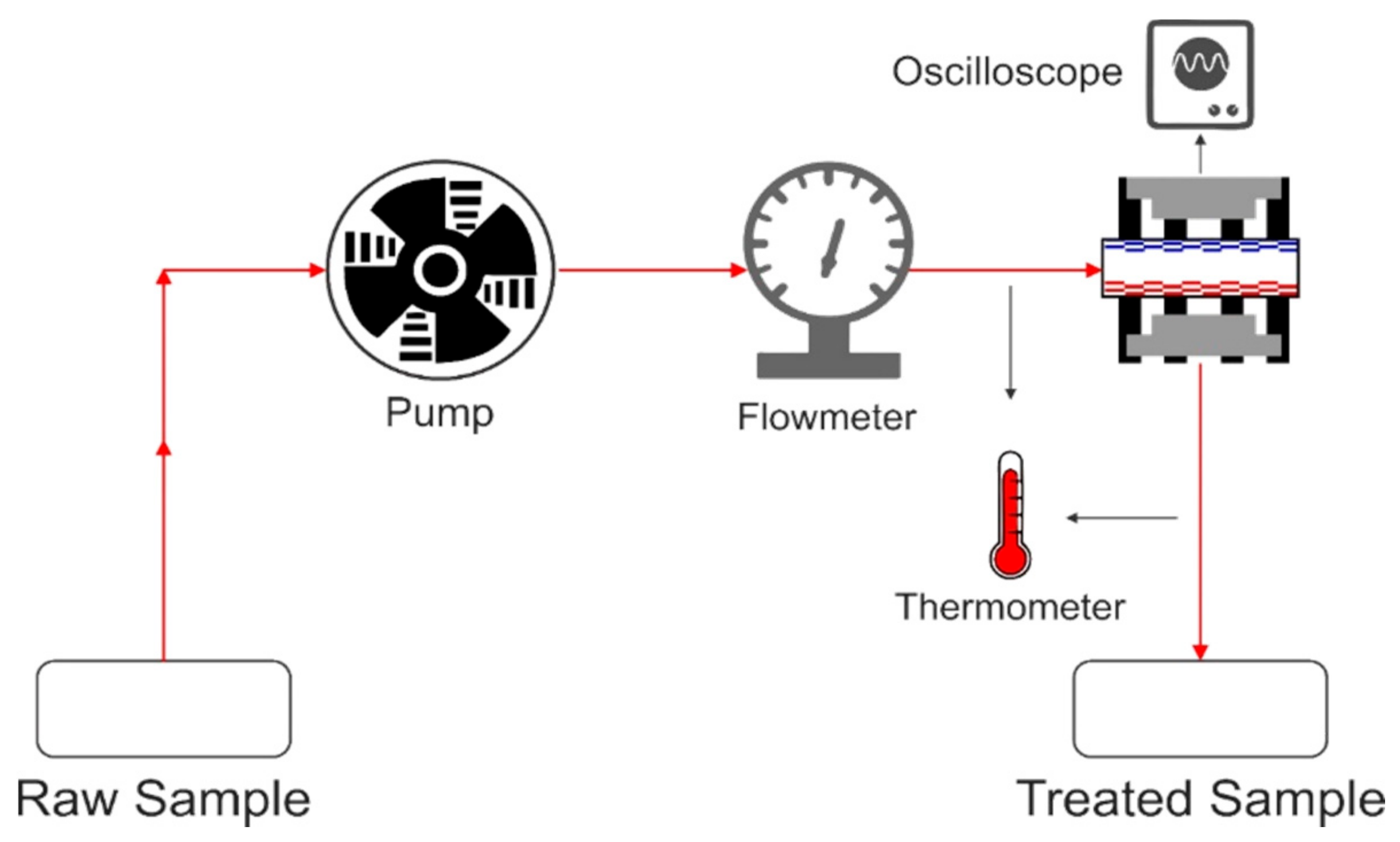

3. PEF-Assisted Extraction Equipment

3.1. PEF Batch Extraction

3.2. PEF Continuous Extraction

4. Factors Influencing the PEF Extraction

5. Applications

5.1. Fruits and Vegetables

| Ref. | Raw Material | Extraction Technique | Pretreatment Condition | Extraction Condition | Solid-Solvent Ratio | Solvent | Yield | TPC | DPPH | FRAP | IC50 | TFC | TAC | TCC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [65] | Cinnamon (Cinnamomum verum) powder | PEF-assisted extraction | Frequency: 1 Hz Voltage: 2–6 5.12 kV/cm No. of pulses: 40–60 NR | Temperature: ambient Time: 48 h | 1:10 w/v | Ethanol 100 mL | 5.06 % | 505.9 mg GA/kg | 91.7% | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| [66] | Nepeta binaludensis | PEF-assisted extraction | No. of pulses:60 Frequency: 1 Hz Voltage: 6 kV No. of pulses: 60 | Temperature: ambient Time: 48 h | 1:10 w/v | Ethanol 100 mL | 11.36% | 417.85 mg GA/g | 74.8% | 1688.53 µmol Fe2+/g | 0.32 mg/mL | NR | NR | NR |

| [24] | Thinned peach (Prunus persica) | PEF-assisted extraction | EFS: 0 kV/cm Specific energy: 0.61–9.98 kJ/kg Pulse frequency: 1 Hz No. of pulses per time: 30–150 µs | Temperature: 35 °C Time: 10 h | NR | Methanol 80% 200 mL water–methanol solvent | NR | 83.3 mg GAE/100 g | 57.8 % | NR | NR | 54.3 CE/100 g | NR | NR |

| [67] | Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) peel | PEF-assisted extraction | EFS:5 kV/cm Total specific energy: 5 kJ/kg | - | 1:40 g/mL | Acetone | NR | NR | 4.2 ± 0.4 mmol TE/100 g FW | NR | NR | NR | NR | 80.4 ± 2.2 mg/100 g FW |

| - | Temperature: 50 Time: 4 h Speed: 160 rpm | 5.2 ± 0.4 mmolTE/100 g FW | 84.0 ± 8.3 mg/100 g FW | |||||||||||

| [68] | Sweet Cherries (Prunus avium) | PEF-assisted pressing | Variable field strength: 1 kV/cm Frequency: 5 Hz Pulse width: 20 µs Total specific energy input: 10 kJ/kg | Pressure: 1.64 bar Time: 5 min | NR | NR | Juice yield40% | NR | NR | 27.4% | NR | NR | 29.2 ± 1.1 mg/100 mL | NR |

| Sweet cherries (Prunus avium) press cake | PEF-assisted extraction | Variable field strength: 0.5–1 kV/cm Frequency: 5 Hz Pulse width: 20 µs Total specific energy input: 10 kJ/kg | Time: 24 h Temperature: 25 °C | 5:1 mL/g Solvent–cake ratio | Acidified aqueous ethanol (50% ethanol; 0.5%HCl, v/v) | NR | NR | NR | 21.0% | NR | NR | 218.0 ± 14.8 mg/100 mL | NR | |

| [15] | Moringa olifera dry leaves | PEF-assisted extraction | EFS: 7 kV/cm | Time: 40 min Temperature: ambient Pulse duration: 20 ms Pulse interval: 100 µs | NR | NR | NR | 40.24 mg GAE/g of dry matter | 98.31 | 108.22 µmoL AAE/g dry matter | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| [63] | Potato (Solanum tuberosum) peels | PEF-assisted extraction | Pulse width:3–25 µs Frequency: 1–450 Hz Electric field: 1 kV/cmSpecific energy: 5 kJ/kg | Time: 30–240 min Temperature: 20–50 °C Speed: 160 rpm | 1:20 g/mL | Water–ethanol mixture Ethanol concentration 50% | NR | 1263.5 ± 43 mgGAE/kg FW PP | 877.17/kg FWPP | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| [69] | Date palm (Phoenix dactylifera) | PEF-assisted ethanolic extraction | EFS: 3 kV/cm Frequenc:10Hz | Time: 6 h | 4:1 v/v | Ethanol–water 300 mL | NR | 67.35 mg GAE/100 g | 50–72 | NR | 110 µL/mL | 6.75 mg CE/100 g | 2.08 mg/L | 6.10 µg/mL |

| [70] | Tropical almond red leaves (Terminalia catappa) | PEF-assisted extraction | NR | Frequency: 1 Hz Electric field intensity: 0.75 kV/cm No. of pulses: 50 n | 1:10 | Water | 74.6% | 241.40 ± 2.15 mg GAE/g | 93.40 ± 1.23% | NR | 42 mg/mL | NR | NR | NR |

| [59] | Red onion (Allium cepa) | PEF-assisted water extraction | Pulse wide:100 µs Frequency: 1 Hz Electric field intensity: 2.5 kV/cm No. of pulse: 90 Specific energy: 0.23–9.38 kJ/kg | Time: 2 h Shaking speed: 200 rpm/min Temperature: 42.5 °C | NR | Distilled water 50 mL | NR | 102.86 mg GAE/100 g FW | 262.39 % | NR | NR | 37.58 mg QE/100 gFW | NR | NR |

| [71] | Wild blueberries (Vaccinium myrtillus) | PEF-assisted pressing | EFS:3 kV/cm Total specific energy: 10 kJ/kg Frequency: 10 Hz Pulse width: 20 µs | Time: 8 min Pressure: 1.32 bar | NR | NR | 56.3 | 45.5% | NR | 35.9 % | NR | NR | 77.5% | NR |

| [72] | Sour cherries (Prunus cerasus) | PEF-assisted pressing | EFS: 5 kV/cm total specific energy input:10 kJ/kg constant frequency: 10 Hz pulse width:20 µs | Pressing time: 9 min | NR | NR | 37.7 g 100/g1 | 133.90 ± 2.67 mg 100/mL Juice | NR | 6.60 ± 0.13 μmol TE/mL | NR | NR | 53.30 ± 0.97 mg 100/mL Juice | NR |

| [73] | Fresh pomelo fruits (Shantian Variety) | - | Number of pulses of 30 Electric field intensity: 4 kV/cm | Temperature: 40 °C | 40:60, v/v | 90 mL ethanol–water | 16.19 mg/mL (naringin) increased by about 20% | NR | 38.58% increased by 70% | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| [74] | Thawed blueberries | PEF-assisted pressing | EFSs: 1, 3 kV/cm Total specific energy: 10 kJ/kg Constant frequency: 20 Hz Pulse width: 20 | Constant pressure: 1.32 bar Time: 8 min | NR | NR | 36.3 ± 1% | 8.0% | NR | NR | NR | NR | 8.3% | NR |

5.2. Agro-Industrial Waste

5.3. Herbs and Spices

5.4. Leaves

5.5. Oleaginous Seeds

5.6. Microorganisms

| Phycocyanin | ||||||

| References | Rawmaterial | PEFtreatment | Extractionmethod | Extraction conditions | Solvent | Yield |

| [105] | Arthrospira platensis | EFS: 25 kV/cm Treatment time: 150 μs Temperature: 40 °C | PEF-assisted extraction | Temperature: 20 °C Time: 360 min | 19 mL of distilled water | Extraction yield 151.94 ± 14.22 mg/g |

| Total Amino Nitrogen Content (TANC) | ||||||

| References | Raw material | PEF treatment | Extractionmethod | Extractionconditions | Solvent | Yield |

| [43] | Fresh abalone (Haliotis Discus Hannai Ino) viscera | NR | PEF-assisted enzymatic extraction | EFS: 20 kV/cm treatment times: 600 s | NR | 42.35%, 175.20 mg/100 mL |

| Lipids | ||||||

| References | Rawmaterial | PEF treatment | Extraction method | Extraction conditions | Solvent | Extractedlipid |

| [109] | fresh microalgae Auxenochlorella protothecoides | Flow rate: 0.1 mL/s Pulse duration 1 µs EFS: 4 MV/m Specific energy: 150 kJ/L | NR | Time: overnight incubation conditions: Temperature: 25 °C Time: 20 h | Hexane–ethanol blend | 97% |

| Pectin | ||||||

| References | Raw material | extraction method | Extraction device | Extraction conditions | Powder–solvent ratio | Yield |

| [110] | Raw jackfruit (Artocarpus heterophyllus) | Combination of PEF- and microwave-assisted extraction | PEF generator microwave reactor | PEF conditions: Time: 5 min, EFS: 10 kV/cm. Microwave conditions: Time: 10 min, Power level of 650 W/g | 1:4 | 18.3% |

| Cellulose | ||||||

| References | Raw material | PEF treatment | Extractionmethod | Solvent | Yield | |

| [39] | Mendong Fiber (Fimbristylis globulosa) | EFS: 1.3 kV/cm Frequency: 20 kHz Time 30 s | PEF-assisted alkali extraction | NaOH sol. (300 mL) 60% conc. | 97.8% | |

| Pigment | ||||||

| References | Raw material | PEF treatment | Extraction method | Extraction conditions | Yield | |

| [111] | Algae paste of Nannochloropsis oceanica | Constant flow rate: 20 mL/min Temperature: 25 °C Square wave: 5 μs EFS: 10 kV/cm Total specific energy inputs:100 kJ/kg | PEF-assisted supercritical CO2 extraction | Pressure: 8, 14, and 20 MPa Fixed temperature: 35 °C CO2/biomass ratio: 53.3 kgCO2/kg DW Holding time: 7 min | Total carotenes: 36% Total chlorophyll: 52% | |

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yammine, S.; Brianceau, S.; Manteau, S.; Turk, M.; Ghidossi, R.; Vorobiev, E.; Mietton-Peuchot, M. Extraction and purification of high added value compounds from by-products of the winemaking chain using alternative/nonconventional processes/technologies. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018, 58, 1375–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjha, M.M.A.N.; Irfan, S.; Nadeem, M.; Mahmood, S. A Comprehensive Review on Nutritional Value, Medicinal Uses, and Processing of Banana. Food Rev. Int. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjha, M.M.A.N.; Shafique, B.; Wang, L.; Irfan, S.; Safdar, M.N.; Murtaza, M.A.; Nadeem, M.; Mahmood, S.; Mueen-ud-Din, G.; Nadeem, H.R. A comprehensive review on phytochemistry, bioactivity and medicinal value of bioactive compounds of pomegranate (Punica granatum). Adv. Tradit. Med. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeem, H.R.; Akhtar, S.; Ismail, T.; Sestili, P.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Ranjha, M.M.A.N.; Jooste, L.; Hano, C.; Aadil, R.M. Heterocyclic Aromatic Amines in Meat: Formation, Isolation, Risk Assessment, and Inhibitory Effect of Plant Extracts. Foods 2021, 10, 1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali Nawaz Ranjha, M.M. A Critical Review on Presence of Polyphenols in Commercial Varieties of Apple Peel, their Extraction and Health Benefits. Open Access J. Biog. Sci. Res. 2020, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, S. A Narrative Review on the Phytochemistry, Nutritional Profile and Properties of Prickly Pear Fruit. Open Access J. Biog. Sci. Res. 2021, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemat, F.; Abert Vian, M.; Fabiano-Tixier, A.S.; Nutrizio, M.; Režek Jambrak, A.; Munekata, P.E.S.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Barba, F.J.; Binello, A.; Cravotto, G. A review of sustainable and intensified techniques for extraction of food and natural products. Green Chem. 2020, 22, 2325–2353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.G.; He, L.; Xi, J. High intensity pulsed electric field as an innovative technique for extraction of bioactive compounds—A review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 57, 2877–2888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjha, M.M.A.N.; Amjad, S.; Ashraf, S.; Khawar, L.; Safdar, M.N.; Jabbar, S.; Nadeem, M.; Mahmood, S.; Murtaza, M.A. Extraction of Polyphenols from Apple and Pomegranate Peels Employing Different Extraction Techniques for the Development of Functional Date Bars. Int. J. Fruit Sci. 2020, 20, S1201–S1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, V.; Sharma, A.; Ghanshyam, C.; Singla, M.L.; Kim, K.H. Influence of pulsed electric field and heat treatment on Emblica officinalis juice inoculated with Zygosaccharomyces bailii. Food Bioprod. Process. 2015, 95, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabrić, D.; Barba, F.; Roohinejad, S.; Gharibzahedi, S.M.T.; Radojčin, M.; Putnik, P.; Bursać Kovačević, D. Pulsed electric fields as an alternative to thermal processing for preservation of nutritive and physicochemical properties of beverages: A review. J. Food Process. Eng. 2018, 41, 12638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamad, A.; Shah, N.N.A.K.; Sulaiman, A.; Mohd Adzahan, N.; Aadil, R.M. Impact of the pulsed electric field on physicochemical properties, fatty acid profiling, and metal migration of goat milk. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2020, 44, 14940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aadil, R.M.; Zeng, X.A.; Sun, D.W.; Wang, M.S.; Liu, Z.W.; Zhang, Z.H. Combined effects of sonication and pulsed electric field on selected quality parameters of grapefruit juice. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 62, 890–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Vega, R.; Elez-Martínez, P.; Martín-Belloso, O. Influence of high-intensity pulsed electric field processing parameters on antioxidant compounds of broccoli juice. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2015, 29, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozinou, E.; Karageorgou, I.; Batra, G.; GDourtoglou, V.; ILalas, S. Pulsed Electric Field Extraction and Antioxidant Activity Determination of Moringa oleifera Dry Leaves: A Comparative Study with Other Extraction Techniques. Beverages 2019, 5, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evrendilek, G.A. Change regime of aroma active compounds in response to pulsed electric field treatment time, sour cherry juice apricot and peach nectars, and physical and sensory properties. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2016, 33, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshad, R.N.; Abdul-Malek, Z.; Munir, A.; Buntat, Z.; Ahmad, M.H.; Jusoh, Y.M.M.; Bekhit, A.E.D.; Roobab, U.; Manzoor, M.F.; Aadil, R.M. Electrical systems for pulsed electric field applications in the food industry: An engineering perspective. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 104, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Gámez, G.; Elez-Martínez, P.; Martín-Belloso, O.; Soliva-Fortuny, R. Changes of carotenoid content in carrots after application of pulsed electric field treatments. Lwt 2021, 147, 111408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzima, K.; Brunton, N.P.; Lyng, J.G.; Frontuto, D.; Rai, D.K. The effect of Pulsed Electric Field as a pre-treatment step in Ultrasound Assisted Extraction of phenolic compounds from fresh rosemary and thyme by-products. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2021, 69, 102644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soquetta, M.B.; Terra, L.D.M.; Bastos, C.P. Green technologies for the extraction of bioactive compounds in fruits and vegetables. CYTA J. Food 2018, 16, 400–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oroian, M.; Escriche, I. Antioxidants: Characterization, natural sources, extraction and analysis. Food Res. Int. 2015, 74, 10–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xi, J.; Li, Z.; Fan, Y. Recent advances in continuous extraction of bioactive ingredients from food-processing wastes by pulsed electric fields. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 61, 1738–1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panja, P. Green extraction methods of food polyphenols from vegetable materials. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2018, 23, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redondo, D.; Venturini, M.E.; Luengo, E.; Raso, J.; Arias, E. Pulsed electric fields as a green technology for the extraction of bioactive compounds from thinned peach by-products. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2018, 45, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thulasidas, J.S.; Varadarajan, G.S.; Sundararajan, R. Pulsed Electric Field for Enhanced Extraction of Intracellular Bioactive Compounds from Plant Products: An Overview. Nov. Approaches Drug Des. Dev. 2019, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koubaa, M.; Roselló-Soto, E.; Šic Žlabur, J.; Režek Jambrak, A.; Brnčić, M.; Grimi, N.; Boussetta, N.; Barba, F.J. Current and New Insights in the Sustainable and Green Recovery of Nutritionally Valuable Compounds from Stevia rebaudiana Bertoni. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015, 63, 6835–6846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barba, F.J.; Boussetta, N.; Vorobiev, E. Emerging technologies for the recovery of isothiocyanates, protein and phenolic compounds from rapeseed and rapeseed press-cake: Effect of high voltage electrical discharges. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2015, 31, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puértolas, E.; Koubaa, M.; Barba, F.J. An overview of the impact of electrotechnologies for the recovery of oil and high-value compounds from vegetable oil industry: Energy and economic cost implications. Food Res. Int. 2016, 80, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkis, J.R.; Boussetta, N.; Tessaro, I.C.; Marczak, L.D.F.; Vorobiev, E. Application of pulsed electric fields and high voltage electrical discharges for oil extraction from sesame seeds. J. Food Eng. 2015, 153, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barba, F.J.; Parniakov, O.; Koubaa, M.; Lebovka, N. Pulsed Electric Fields Assisted Extraction from Exotic Fruit Residues. In Handbook of Electroporation; Miklavcic, D., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 1–18. ISBN 978-3-319-26779-1. [Google Scholar]

- Teh, S.S.; Niven, B.E.; Bekhit, A.E.D.A.; Carne, A.; Birch, E.J. Microwave and pulsed electric field assisted extractions of polyphenols from defatted canola seed cake. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 50, 1109–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barba, F.J.; Parniakov, O.; Pereira, S.A.; Wiktor, A.; Grimi, N.; Boussetta, N.; Saraiva, J.A.; Raso, J.; Martin-Belloso, O.; Witrowa-Rajchert, D.; et al. Current applications and new opportunities for the use of pulsed electric fields in food science and industry. Food Res. Int. 2015, 77, 773–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, S.A.; Alexandre, E.M.C.; Pintado, M.; Saraiva, J.A. Effect of emergent non-thermal extraction technologies on bioactive individual compounds profile from different plant materials. Food Res. Int. 2019, 115, 177–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandre, E.M.C.; Moreira, S.A.; Pintado, M.; Saraiva, J.A. Emergent extraction technologies to valorize fruit and vegetable residues. In Agricultural Research Updates; Gorawala, P., Mandhatri, S., Eds.; Nova Science: New York, NY, USA, 2017; Volume 17, pp. 37–79. ISBN 9781536109078. [Google Scholar]

- Ricci, A.; Parpinello, G.P.; Versari, A. Recent Advances and Applications of Pulsed Electric Fields (PEF) to Improve Polyphenol Extraction and Color Release during Red Winemaking. Beverages 2018, 4, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papachristou, I.; Akaberi, S.; Silve, A.; Navarro-López, E.; Wüstner, R.; Leber, K.; Nazarova, N.; Müller, G.; Frey, W. Analysis of the lipid extraction performance in a cascade process for Scenedesmus almeriensis biorefinery. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2021, 14, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowacka, M.; Tappi, S.; Wiktor, A.; Rybak, K.; Miszczykowska, A.; Czyzewski, J.; Drozdzal, K.; Witrowa-Rajchert, D.; Tylewicz, U. The impact of pulsed electric field on the extraction of bioactive compounds from beetroot. Foods 2019, 8, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moradi, N.; Rahimi, M. Effect of simultaneous ultrasound/pulsed electric field pretreatments on the oil extraction from sunflower seeds. Sep. Sci. Technol. 2018, 53, 2088–2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suryanto, H.; Fikri, A.A.; Permanasari, A.A.; Yanuhar, U.; Sukardi, S. Pulsed Electric Field Assisted Extraction of Cellulose From Mendong Fiber (Fimbristylis globulosa) and its Characterization. J. Nat. Fibers 2018, 15, 406–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yongguang, Y.; Yuzhu, H.; Yong, H. Pulsed electric field extraction of polysaccharide from Rana temporaria chensinensis David. Int. J. Pharm. 2006, 312, 33–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshad, R.N.; Abdul-Malek, Z.; Roobab, U.; Qureshi, M.I.; Khan, N.; Ahmad, M.H.; Liu, Z.W.; Aadil, R.M. Effective valorization of food wastes and by-products through pulsed electric field: A systematic review. J. Food Process. Eng. 2021, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zia, S.; Khan, M.R.; Shabbir, M.A.; Aslam Maan, A.; Khan, M.K.I.; Nadeem, M.; Khalil, A.A.; Din, A.; Aadil, R.M. An Inclusive Overview of Advanced Thermal and Nonthermal Extraction Techniques for Bioactive Compounds in Food and Food-related Matrices. Food Rev. Int. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Lin, J.; Chen, J.; Fang, T. Pulsed Electric Field-Assisted Enzymatic Extraction of Protein from Abalone (Haliotis Discus Hannai Ino) Viscera. J. Food Process. Eng. 2016, 39, 702–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Wang, L.; Jones, G.; Trang, H.; Yin, Y.; Liu, J. Optimized extraction of calcium malate from eggshell treated by PEF and an absorption assessment in vitro. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2012, 50, 1327–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Zheng, Y.; He, H.; Sun, Z.; Li, A. Effective aluminum extraction using pressure leaching of bauxite reaction residue from coagulant industry and leaching kinetics study. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 104770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zderic, A.; Zondervan, E. Polyphenol extraction from fresh tea leaves by pulsed electric field: A study of mechanisms. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2016, 109, 586–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokosa, J.M. Selecting an extraction solvent for a greener liquid phase microextraction (LPME) mode-based analytical method. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2019, 118, 238–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efthymiopoulos, I.; Hellier, P.; Ladommatos, N.; Russo-Profili, A.; Eveleigh, A.; Aliev, A.; Kay, A.; Mills-Lamptey, B. Influence of solvent selection and extraction temperature on yield and composition of lipids extracted from spent coffee grounds. Ind. Crops Prod. 2018, 119, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pintać, D.; Majkić, T.; Torović, L.; Orčić, D.; Beara, I.; Simin, N.; Mimica–Dukić, N.; Lesjak, M. Solvent selection for efficient extraction of bioactive compounds from grape pomace. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2018, 111, 379–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pintać, D.; Majkić, T.; Torović, L.; Orčić, D.; Beara, I.; Simin, N.; Mimica–Dukić, N.; Lesjak, M. Extraction of Bioactive Compound from Some Fruits and Vegetables (Pomegranate Peel, Carrot and Tomato). Am. J. Food Nutr. 2016, 4, 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altemimi, A.; Lakhssassi, N.; Baharlouei, A.; Watson, D.G.; Lightfoot, D.A. Phytochemicals: Extraction, isolation, and identification of bioactive compounds from plant extracts. Plants 2017, 6, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, B.K. Ultrasound: A clean, green extraction technology. TrAC-Trends Anal. Chem. 2015, 71, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Pérez, C.; Quirantes-Piné, R.; Fernández-Gutiérrez, A.; Segura-Carretero, A. Optimization of extraction method to obtain a phenolic compounds-rich extract from Moringa oleifera Lam leaves. Ind. Crops Prod. 2015, 66, 246–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heleno, S.A.; Diz, P.; Prieto, M.A.; Barros, L.; Rodrigues, A.; Barreiro, M.F.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R. Optimization of ultrasound-assisted extraction to obtain mycosterols from Agaricus bisporus L. by response surface methodology and comparison with conventional Soxhlet extraction. Food Chem. 2016, 197, 1054–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, S.Y.; Burritt, D.J.; Oey, I. Evaluation of the anthocyanin release and health-promoting properties of Pinot Noir grape juices after pulsed electric fields. Food Chem. 2016, 196, 833–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shree, T.J.; Sree, V.G.; Sundararajan, R. Enhancement of Bioactive Compounds from Green Grapes Extract using Pulsed Electric Field treatment. J. Cancer Prev. Curr. Res. 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamanauskas, N.; Pataro, G.; Bobinas, Č.; Šatkauskas, S.; Viškelis, P.; Bobinaitė, R.; Ferrari, G. Impulsinio elektrinio lauko įtaka sulčių ir bioaktyvių medžiagų išgavimui iš aviečių ir jų produktų. Zemdirbyste 2016, 103, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barba, F.J.; Brianceau, S.; Turk, M.; Boussetta, N.; Vorobiev, E. Effect of Alternative Physical Treatments (Ultrasounds, Pulsed Electric Fields, and High-Voltage Electrical Discharges) on Selective Recovery of Bio-compounds from Fermented Grape Pomace. Food Bioprocess. Technol. 2015, 8, 1139–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.W.; Zeng, X.A.; Ngadi, M. Enhanced extraction of phenolic compounds from onion by pulsed electric field (PEF). J. Food Process. Preserv. 2018, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fincan, M. Extractability of phenolics from spearmint treated with pulsed electric field. J. Food Eng. 2015, 162, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkis, J.R.; Boussetta, N.; Blouet, C.; Tessaro, I.C.; Marczak, L.D.F.; Vorobiev, E. Effect of pulsed electric fields and high voltage electrical discharges on polyphenol and protein extraction from sesame cake. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2015, 29, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, D.; Farid, M.M. Pulsed electric field extraction of valuable compounds from white button mushroom (Agaricus bisporus). Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2015, 29, 178–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frontuto, D.; Carullo, D.; Harrison, S.M.; Brunton, N.P.; Ferrari, G.; Lyng, J.G.; Pataro, G. Optimization of Pulsed Electric Fields-Assisted Extraction of Polyphenols from Potato Peels Using Response Surface Methodology. Food Bioprocess. Technol. 2019, 12, 1708–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puértolas, E.; Martínez De Marañón, I. Olive oil pilot-production assisted by pulsed electric field: Impact on extraction yield, chemical parameters and sensory properties. Food Chem. 2015, 167, 497–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pashazadeh, B.; Elhamirad, A.H.; Hajnajari, H.; Sharayei, P.; Armin, M. Optimization of the pulsed electric field -assisted extraction of functional compounds from cinnamon. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2020, 23, 101461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahalleh, A.A.; Sharayei, P.; Mortazavi, S.A.; Azarpazhooh, E.; Niazmand, R. Optimization of the pulsed electric field-assisted extraction of functional compounds from nepeta binaludensis. Agric. Eng. Int. CIGR J. 2019, 21, 184–194. [Google Scholar]

- Pataro, G.; Carullo, D.; Ferrari, G. Effect of PEF pre-treatment and extraction temperature on the recovery of carotenoids from tomato wastes. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2019, 75, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pataro, G.; Carullo, D.; Bobinaite, R.; Donsì, G.; Ferrari, G. Improving the extraction yield of juice and bioactive compounds from sweet cherries and their by-products by pulsed electric fields. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2017, 57, 1717–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddeeg, A.; Manzoor, M.F.; Ahmad, M.H.; Ahmad, N.; Ahmed, Z.; Khan, M.K.I.; Maan, A.A.; Mahr-Un-Nisa; Zeng, X.A.; Ammar, A.F. Pulsed electric field-assisted ethanolic extraction of date palm fruits: Bioactive compounds, antioxidant activity and physicochemical properties. Processes 2019, 7, 585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghaddam, T.N.; Elhamirad, A.H.; Saeidi Asl, M.R.; Shahidi Noghabi, M. Pulsed electric field-assisted extraction of phenolic antioxidants from tropical almond red leaves. Chem. Pap. 2020, 74, 3957–3961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobinaitė, R.; Pataro, G.; Lamanauskas, N.; Šatkauskas, S.; Viškelis, P.; Ferrari, G. Application of pulsed electric field in the production of juice and extraction of bioactive compounds from blueberry fruits and their by-products. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 52, 5898–5905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobinaitė, R.; Pataro, G.; Visockis, M.; Bobinas, Č.; Ferrari, G.; Viškelis, P. Potential application of pulsed electric fields to improve the recovery of bioactive compounds from sour cherries and their by-products. In Proceedings of the 11th Baltic Conference on Food Science and Technology, Jelgava, Latvia, 27–28 April 2017; pp. 70–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, D.; Ren, E.F.; Li, J.; Zeng, X.A.; Li, S.L. Effects of pulsed electric field-assisted treatment on the extraction, antioxidant activity and structure of naringin. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2021, 265, 118480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamanauskas, N.; Bobinaitė, R.; Šatkauskas, S.; Viškelis, P.; Pataro, G.; Ferrari, G. Sulčių spaudimas iš sušaldytų/atšildytų mėlynių taikant impulsinio elektrinio lauko metodą. Zemdirbyste 2015, 102, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, A.; Panesar, P.S.; Bera, M.B. Valorization of fruits and vegetables waste through green extraction of bioactive compounds and their nanoemulsions-based delivery system. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2019, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudra, S.G.; Nishad, J.; Jakhar, N.; Kaur, C. Food Industry Waste: Mine of Nutraceuticals. Int. J. Sci. Enviro. Technol. 2015, 4, 205–229. [Google Scholar]

- Sagar, N.A.; Pareek, S.; Sharma, S.; Yahia, E.M.; Lobo, M.G. Fruit and Vegetable Waste: Bioactive Compounds, Their Extraction, and Possible Utilization. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2018, 17, 512–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina-Meza, I.G.; Barbosa-Cánovas, G.V. Assisted extraction of bioactive compounds from plum and grape peels by ultrasonics and pulsed electric fields. J. Food Eng. 2015, 166, 268–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Kantar, S.; Boussetta, N.; Lebovka, N.; Foucart, F.; Rajha, H.N.; Maroun, R.G.; Louka, N.; Vorobiev, E. Pulsed electric field treatment of citrus fruits: Improvement of juice and polyphenols extraction. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2018, 46, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irfan, S.; Ranjha, M.M.A.N.; Mahmood, S.; Saeed, W.; Alam, M.Q. Lemon Peel: A Natural Medicine. Int. J. Biotechnol. Allied Fields 2018, 7, 185–194. [Google Scholar]

- Irfan, S.; Ranjha, M.M.A.N.; Mahmood, S.; Mueen-ud-Din, G.; Rehman, S.; Saeed, W.; Qamrosh Alam, M.; Mahvish Zahra, S.; Yousaf Quddoos, M.; Ramzan, I.; et al. A Critical Review on Pharmaceutical and Medicinal Importance of Ginger. Acta Sci. Nutr. Health 2019, 3, 78–82. [Google Scholar]

- Faniyi, T.O.; Adewumi, M.K.; Jack, A.A.; Adegbeye, M.J.; Elghandour, M.M.M.Y.; Barbabosa- Pliego, A.; Salem, A.Z.M. Extracts of herbs and spices as feed additives mitigate ruminal methane production and improve fermentation characteristics in West African Dwarf sheep. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2021, 53, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdés, A.; Mellinas, A.C.; Ramos, M.; Burgos, N.; Jiménez, A.; Garrigós, M.C. Use of herbs, spices and their bioactive compounds in active food packaging. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 40324–40335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roselló-Soto, E.; Parniakov, O.; Deng, Q.; Patras, A.; Koubaa, M.; Grimi, N.; Boussetta, N.; Tiwari, B.K.; Vorobiev, E.; Lebovka, N.; et al. Application of Non-conventional Extraction Methods: Toward a Sustainable and Green Production of Valuable Compounds from Mushrooms. Food Eng. Rev. 2016, 8, 214–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacometti, J.; Bursać Kovačević, D.; Putnik, P.; Gabrić, D.; Bilušić, T.; Krešić, G.; Stulić, V.; Barba, F.J.; Chemat, F.; Barbosa-Cánovas, G.; et al. Extraction of bioactive compounds and essential oils from mediterranean herbs by conventional and green innovative techniques: A review. Food Res. Int. 2018, 113, 245–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.W.; Lin, L.G.; Ye, W.C. Techniques for extraction and isolation of natural products: A comprehensive review. Chin. Med. 2018, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segovia, F.J.; Luengo, E.; Corral-Pérez, J.J.; Raso, J.; Almajano, M.P. Improvements in the aqueous extraction of polyphenols from borage (Borago officinalis L.) leaves by pulsed electric fields: Pulsed electric fields (PEF) applications. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2015, 65, 390–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barba, F.J.; Grimi, N.; Vorobiev, E. Evaluating the potential of cell disruption technologies for green selective extraction of antioxidant compounds from Stevia rebaudiana Bertoni leaves. J. Food Eng. 2015, 149, 222–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagneten, M.; Leiva, G.; Salvatori, D.; Schebor, C.; Olaiz, N. Optimization of Pulsed Electric Field Treatment for the Extraction of Bioactive Compounds from Blackcurrant. Food Bioprocess. Technol. 2019, 12, 1102–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Esveld, E.; Vincken, J.P.; Bruins, M.E. Pulsed Electric Field as an Alternative Pre-treatment for Drying to Enhance Polyphenol Extraction from Fresh Tea Leaves. Food Bioprocess. Technol. 2019, 12, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrawan, Y.; Sabrinauly, S.; Hawa, L.C.; Rachmawati, M.; Argo, B.D. Analysis of the phenol and flavonoid content from basil leaves (Ocimum americanum L) extract using pulsed electric field (PEF) pre-treatment. Agric. Eng. Int. CIGR J. 2019, 21, 149–158. [Google Scholar]

- Mushtaq, A.; Roobab, U.; Denoya, G.I.; Inam-Ur-Raheem, M.; Gullón, B.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Barba, F.J.; Zeng, X.A.; Wali, A.; Aadil, R.M. Advances in green processing of seed oils using ultrasound-assisted extraction: A review. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2020, 44, e14740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusuf, A.K. A Review of Methods Used for Seed Oil Extraction. Int. J. Sci. Res. 2017, 8, 1854–1861. [Google Scholar]

- Haji-Moradkhani, A.; Rezaei, R.; Moghimi, M. Optimization of pulsed electric field-assisted oil extraction from cannabis seeds. J. Food Process. Eng. 2019, 42, e13028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batool, M.; Kauser, S.; Nadeem, H.R.; Perveen, R.; Irfan, S.; Siddiqa, A.; Shafique, B.; Zahra, S.M.; Waseem, M.; Khalid, W.; et al. A Critical Review on Alpha Tocopherol: Sources, RDA and Health Benefits. J. Appl. Pharm. 2020, 12, 19–39. [Google Scholar]

- Chemat, F.; Rombaut, N.; Sicaire, A.G.; Meullemiestre, A.; Fabiano-Tixier, A.S.; Abert-Vian, M. Ultrasound assisted extraction of food and natural products. Mechanisms, techniques, combinations, protocols and applications. A review. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2017, 34, 540–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vorobiev, E.; Lebovka, N. Pulsed electric energy-assisted biorefinery of oil crops and residues. In Handbook of Electroporation; Miklavčič, D., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; Volume 4, pp. 2863–2881. ISBN 9783319328867. [Google Scholar]

- Sitzmann, W.; Vorobiev, E.; Lebovka, N. Applications of electricity and specifically pulsed electric fields in food processing: Historical backgrounds. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2016, 37, 302–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shorstkii, I.; Koshevoi, E. Extraction Kinetic of Sunflower Seeds Assisted by Pulsed Electric Fields. Iran. J. Sci. Technol. Trans. A Sci. 2019, 43, 813–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.J.; Xue, C.M.; Zhang, S.S.; Yao, G.M.; Zhang, L.; Wang, S.J. Effects of high intensity pulsed electric fields on yield and chemical composition of rose essential oil. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2017, 10, 295–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shorstkii, I.; Mirshekarloo, M.S.; Koshevoi, E. Application of Pulsed Electric Field for Oil Extraction from Sunflower Seeds: Electrical Parameter Effects on Oil Yield. J. Food Process. Eng. 2017, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamborrino, A.; Urbani, S.; Servili, M.; Romaniello, R.; Perone, C.; Leone, A. Pulsed electric fields for the treatment of olive pastes in the oil extraction process. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, J.M.; Delso, C.; Álvarez, I.; Raso, J. Pulsed electric field-assisted extraction of valuable compounds from microorganisms. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2020, 19, 530–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yellamanda, B.; Vijayalakshmi, M.; Kavitha, A.; Reddy, D.K.; Venkateswarlu, Y. Extraction and bioactive profile of the compounds produced by Rhodococcus sp. VLD-10. 3 Biotech. 2016, 6, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Martínez, J.M.; Luengo, E.; Saldaña, G.; Álvarez, I.; Raso, J. C-phycocyanin extraction assisted by pulsed electric field from Artrosphira platensis. Food Res. Int. 2017, 99, 1042–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaeschke, D.P.; Mercali, G.D.; Marczak, L.D.F.; Müller, G.; Frey, W.; Gusbeth, C. Extraction of valuable compounds from Arthrospira platensis using pulsed electric field treatment. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 283, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, J.M.; Delso, C.; Álvarez, I.; Raso, J. Pulsed electric field permeabilization and extraction of phycoerythrin from Porphyridium cruentum. Algal Res. 2019, 37, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carullo, D.; Abera, B.D.; Casazza, A.A.; Donsì, F.; Perego, P.; Ferrari, G.; Pataro, G. Effect of pulsed electric fields and high pressure homogenization on the aqueous extraction of intracellular compounds from the microalgae Chlorella vulgaris. Algal Res. 2018, 31, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silve, A.; Kian, C.B.; Papachristou, I.; Kubisch, C.; Nazarova, N.; Wüstner, R.; Leber, K.; Strässner, R.; Frey, W. Incubation time after pulsed electric field treatment of microalgae enhances the efficiency of extraction processes and enables the reduction of specific treatment energy. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 269, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandhu Lal, A.M.; Prince, M.V.; Sreeja, R. Studies on Characterisation of Combined Pulsed Electric Field and Microwave Extracted Pectin from Jack Fruit Rind and Core. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2020, 9, 2371–2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pataro, G.; Carullo, D.; Ferrari, G. PEF-assisted supercritical CO2 extraction of pigments from microalgae nannochloropsis oceanica in a continuous flow system. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2019, 74, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ref. | Raw Material | PEF-Pretreatment | Extraction Method | Extraction Conditions | Solid-Solvent Ratio | Solvent | Yield | TPC | AA | TAC | DPPH | FRAP | TFC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [89] | Thawed blackcurrant (Ribes nigrum) | EFS: 1318 kV/cm Pulses: 315 | Cold pressing | Power: 150 W Velocity: 70 rpm Pressing time: 1.5 min | NR | NR | NR | 3.8 ± 0.2 mg GA/g | 1.88 ± 0.06 mg GA/g | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| [72] | Blueberry (Vaccinium myrtillus) press cake | EFS: 5 kV/cm | Solid–liquid extraction | Temperature: ambient Time: 24 h Shaking speed: 150 rpm | 6:1 mL/g Solvent to press cake ratio | 50% Ethanol; 0.5% HCl, v/v | NR | 89.3% | NR | 111% | NR | 80% | NR |

| [90] | Fresh tea leaves (Camellia sinensis) | EFS: 1.00 kV/cm Pulses: 100 Energy: 22 kJ/kg Temperature: 1.5 °C | Organic solvent extraction | Time: 2 h Temperature: room Stirring speed: 250 rpm | 1:1000 Biomass to solvent ratio | 50% acetone/water (w/w) solution | NR | 398 mg/L | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| [72] | Sour cherry (Prunus cerasus) press cake | EFS: 5 kV/cm Specific energy input: 10 kJ/kg Frequency: 10 Hz Pulse width: 20 µs | Solvent extraction | Time: 24 h Temperature: ambient | 10:1 v/w solvent to press cake | Acidified aqueous methanol 70% MeOH and 0.5% HCl, v/v | NR | 407.90 ± 18.54 mg/100 g | NR | 168.50 ± 3.99 mg/100 g | NR | 56.10 ± 1.25 μmol TE/g | NR |

| [91] | Basil leaves (Ocimum Americanum) | EFS: 2–3 kV/cm Time: 1–2 min | Conventional method: maceration | Time: 3 h Temperature: room | NR | Distilled water 300 mL | 33.15% ± 2.484% | 115.203 ± 1.115 mg GAE/g extract | NR | NR | NR | NR | 75.816 ± 0.723 mg QE/g |

| [19] | Rosmary (Salvia rosmarinusby)―product | Frequency: 10 Hz Pulse width: 30 µs Pulses: 167 EFS: 1.1 kV/cm Specific energy input 0.36/kg 24 g of 0.1% aqueous NaCl (1:1.4 w/v) | Ultrasound assisted | Power: 200 W Temperature: 40 °C Time: 12.48 min | (1: 20 w/v) | 100 mL of 55.19% aqueous EtOH | NR | 297 mg GAE/100 g FW | NR | NR | 593 mg TE/100 g FW | NR | NR |

| Thyme (Thymus vulgaris) by-product | Frequency: 10 Hz Pulse width: 30 µs Pulses:167 EFS: 1.1 kV/cm Specific energy input 0.46 kJ/kg 24 g of 0.1% aqueous NaCl 24 g of 0.1% aqueous NaCl (1:1.5 w/v) | 460 mg GAE/100 g FW | 570 mg TE/100 g FW | ||||||||||

| [57] | Raspberry press cake | EFS: 1 kV/cm, 3 kV/cm Total specific energy: 1 kJ/kg, 6 kJ/kg Frequency: 20 Hz Pulse width: 20 µs | Solvent extraction | Temperature: ambient Time: 24 h Shaking speed: 150 rpm | Solvent to press cake 6:1 mL/g | 50% ethanol, 0.5% HCl, v/v | NR | 420.8 ± 39.33 mg GAE mg/100 g | NR | 50.7 ± 3.38 mg/100 g | NR | 24% | NR |

| Ref. | Raw Material | PEF Pretreatment Conditions | Extraction Method | Extraction Equipment | Extraction Conditions | Solvent | Oil Yield |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [99] | Sunflower seeds | EFS: 7.0 kV/cm Frequency: 0.5 Hz Solvent content: 50 wt.% Time: 90 s Pulse width: 30 µs | Solvent extraction | Shaker | Frequency: 400/min Time: 3 h Temperature: room | Bioethanol | 55.9% |

| [100] | Damask rose flowers | EFS: 20 kV/cm Pulse number: 8 | PEF-assisted Hydro distillation | Clevenger-type micro-apparatus | Distillation temperature: 100 °C Distillation time: 2 h | 10% sodium chloride | yield of 0.105% with a 50% increase in essential oil |

| [101] | Sunflower seeds | EFS: 7 kV/cm Frequency: 1.5 Hz Treatment time: 30 s Pulse width: 30 µs | Solvent extraction | Shaker | Frequency: 400/min Time: 3 h Temperature: room | Hexane 40 mL (50 wt.%) | 48.24% |

| [64] | Olive fruits (Arroniz variety) | NR | Pilot PEF-assisted extraction | Pilot PEF system | Electric fields: 2 kV/cm Frequency: 25 Hz flow rate: 520 kg/h Specific energy: 11.25 kJ/kg | NR | 22.66 kg/100 kg |

| [102] | Olives (Nocellara del Belice variety) | EFS: 2 kV/cm Frequency: 25 Hz Pulse width: 50 µs Mass flow rate: 2300 kg/h Energy delivered per pulse: 210 J Specific energy: 7.83 kJ/kg | NR | Hammer crusher Malaxation machine | Malaxation time: 30 min Temperature: 27 °C | NR | 85.5% |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ranjha, M.M.A.N.; Kanwal, R.; Shafique, B.; Arshad, R.N.; Irfan, S.; Kieliszek, M.; Kowalczewski, P.Ł.; Irfan, M.; Khalid, M.Z.; Roobab, U.; et al. A Critical Review on Pulsed Electric Field: A Novel Technology for the Extraction of Phytoconstituents. Molecules 2021, 26, 4893. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26164893

Ranjha MMAN, Kanwal R, Shafique B, Arshad RN, Irfan S, Kieliszek M, Kowalczewski PŁ, Irfan M, Khalid MZ, Roobab U, et al. A Critical Review on Pulsed Electric Field: A Novel Technology for the Extraction of Phytoconstituents. Molecules. 2021; 26(16):4893. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26164893

Chicago/Turabian StyleRanjha, Muhammad Modassar A. N., Rabia Kanwal, Bakhtawar Shafique, Rai Naveed Arshad, Shafeeqa Irfan, Marek Kieliszek, Przemysław Łukasz Kowalczewski, Muhammad Irfan, Muhammad Zubair Khalid, Ume Roobab, and et al. 2021. "A Critical Review on Pulsed Electric Field: A Novel Technology for the Extraction of Phytoconstituents" Molecules 26, no. 16: 4893. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26164893

APA StyleRanjha, M. M. A. N., Kanwal, R., Shafique, B., Arshad, R. N., Irfan, S., Kieliszek, M., Kowalczewski, P. Ł., Irfan, M., Khalid, M. Z., Roobab, U., & Aadil, R. M. (2021). A Critical Review on Pulsed Electric Field: A Novel Technology for the Extraction of Phytoconstituents. Molecules, 26(16), 4893. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26164893