Detection of Oxidative Stress Induced by Nanomaterials in Cells—The Roles of Reactive Oxygen Species and Glutathione

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Reactive Oxygen Species

2.1. Superoxide

2.1.1. Role of Superoxide in Nanomaterial Toxicity

2.1.2. Methods for the Detection of Superoxide

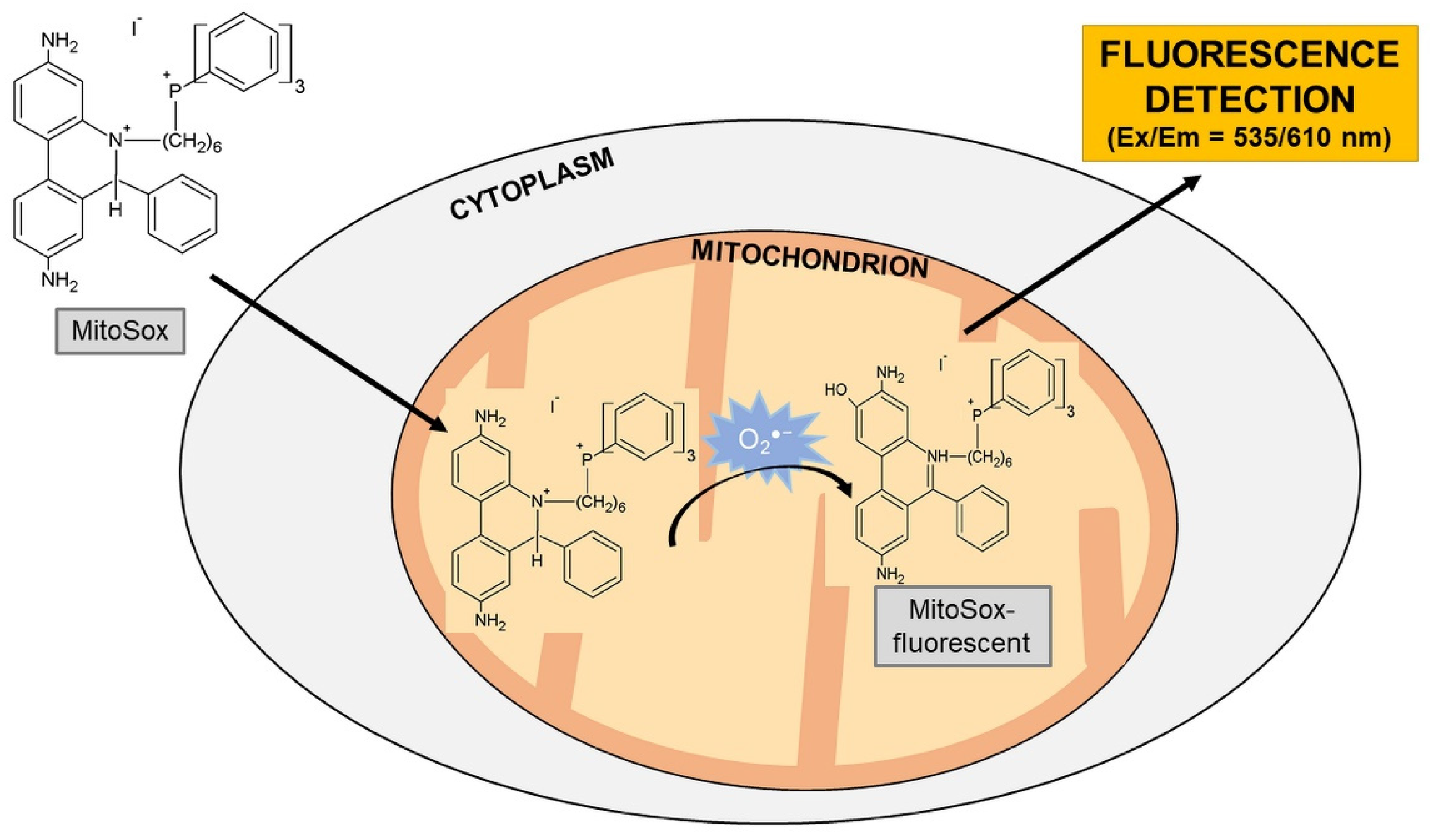

MitoSox

1,3–Diphenylisobenzofuran

2.2. Hydroxyl Radical

2.2.1. Role of Hydroxyl Radical in Nanomaterial Toxicity

2.2.2. Methods for the Detection of Hydroxyl Radical

2.3. Singlet Oxygen

2.3.1. Role of Singlet Oxygen in Nanomaterial Toxicity

2.3.2. Methods for the Detection of Singlet Oxygen

2.4. Hydrogen Peroxide

2.4.1. Role of Hydrogen Peroxide in Nanomaterial Toxicity

2.4.2. Methods for the Detection of Hydrogen Peroxide

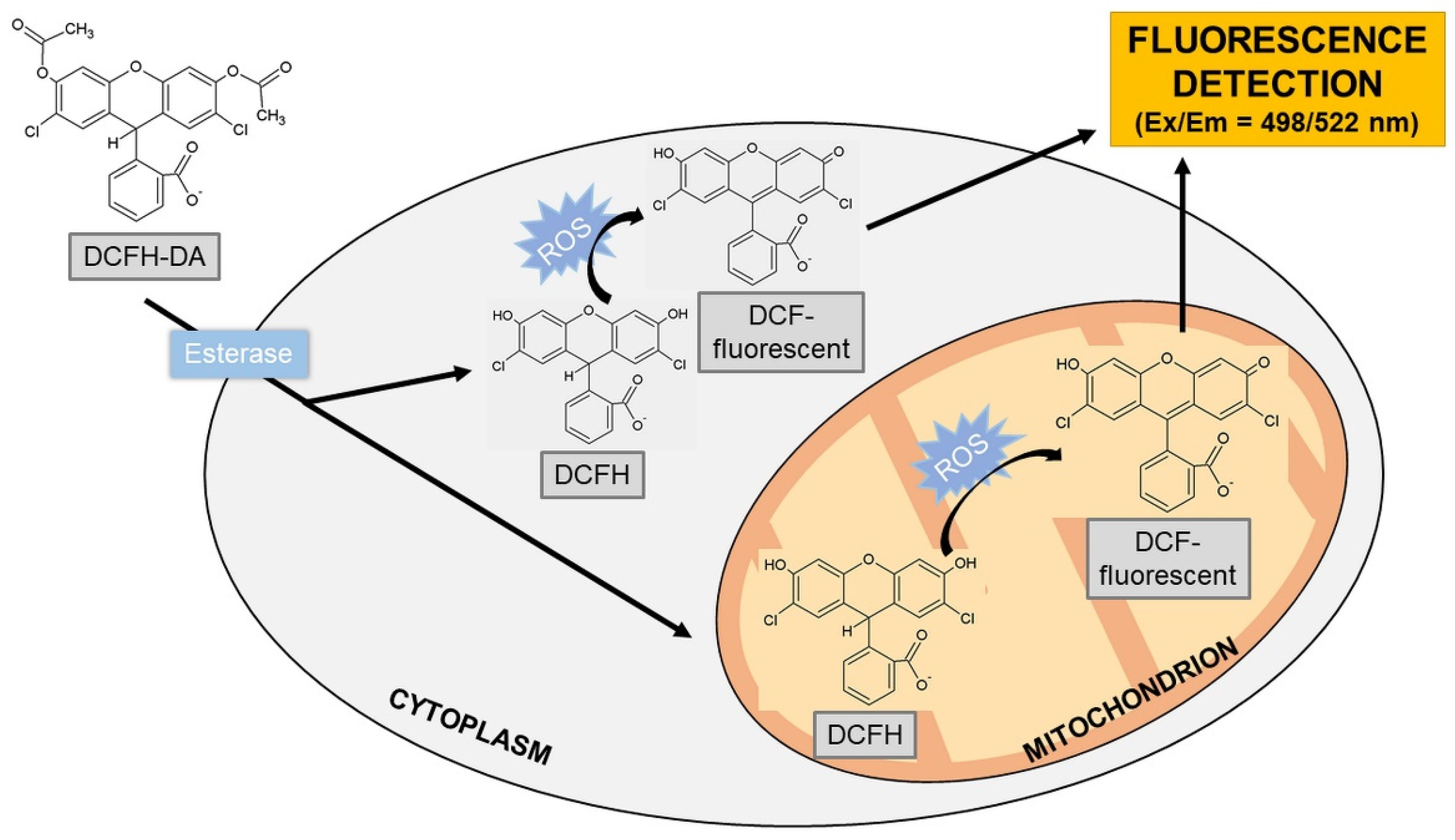

2′,7′-Dichlorodihydrofluorescein

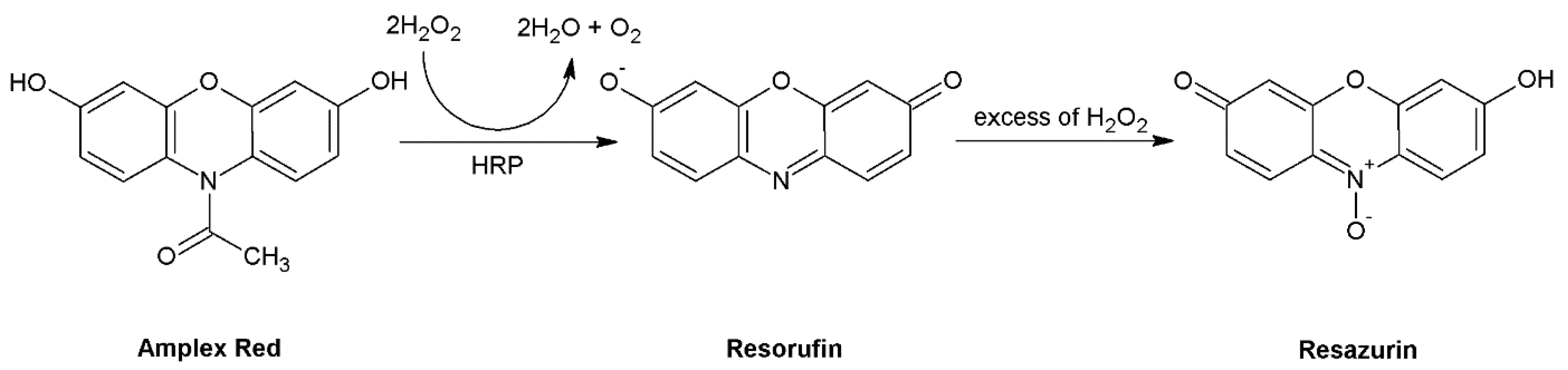

Amplex Red

HyPer Ratiometric Sensor

Pentafluorobenzenesulfonyl Fluoresceins

Europium Ion

Homovanilic Acid

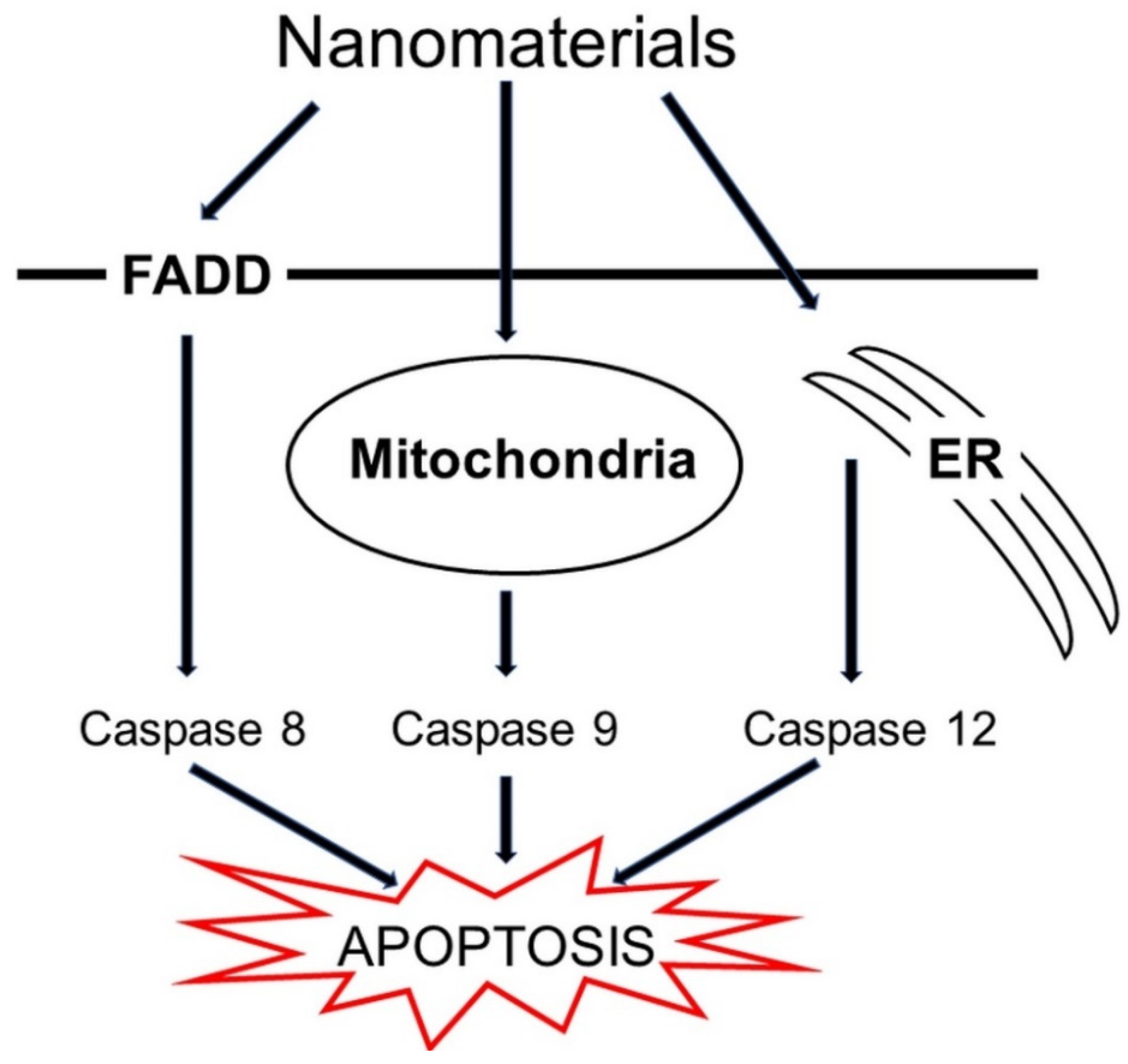

3. Role of Reactive Oxygen Species Induced by Nanoparticles in Cell Signaling

4. Current Trends in the Evaluation of Nanotoxicity In Vitro

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hayyan, M.; Hashim, M.A.; AlNashef, I.M. Superoxide Ion: Generation and Chemical Implications. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 3029–3085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lushchak, V.I. Free radicals, reactive oxygen species, oxidative stress and its classification. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2014, 224, 164–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juan, C.A.; Perez de la Lastra, J.M.; Plou, F.J.; Perez-Lebena, E. The Chemistry of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Revisited: Outlining Their Role in Biological Macromolecules (DNA, Lipids and Proteins) and Induced Pathologies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simon, H.U.; Haj-Yehia, A.; Levi-Schaffer, F. Role of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in apoptosis induction. Apoptosis 2000, 5, 415–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagner, H.; Cheng, J.W.; Ko, E.Y. Role of reactive oxygen species in male infertility: An updated review of literature. Arab. J. Urol. 2018, 16, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ott, M.; Gogvadze, V.; Orrenius, S.; Zhivotovsky, B. Mitochondria, oxidative stress and cell death. Apoptosis 2007, 12, 913–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, R.Z.; Jiang, S.; Zhang, L.; Yu, Z.B. Mitochondrial electron transport chain, ROS generation and uncoupling (Review). Int. J. Mol. Med. 2019, 44, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suski, J.; Lebiedzinska, M.; Bonora, M.; Pinton, P.; Duszynski, J.; Wieckowski, M.R. Relation Between Mitochondrial Membrane Potential and ROS Formation. Methods Mol. Biol. 2018, 1782, 357–381. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mazat, J.P.; Devin, A.; Ransac, S. Modelling mitochondrial ROS production by the respiratory chain. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2020, 77, 455–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parey, K.; Wirth, C.; Vonck, J.; Zickermann, V. Respiratory complex I—structure, mechanism and evolution. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2020, 63, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husen, P.; Nielsen, C.; Martino, C.F.; Solov’yov, I.A. Molecular Oxygen Binding in the Mitochondrial Electron Transfer Flavoprotein. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2019, 59, 4868–4879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mailloux, R.J. An Update on Mitochondrial Reactive Oxygen Species Production. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papa, S.; Skulachev, V.P. Reactive oxygen species, mitochondria, apoptosis and aging. Mol. Cell BioChem. 1997, 174, 305–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ventura, J.J.; Cogswell, P.; Flavell, R.A.; Baldwin, A.S., Jr.; Davis, R.J. JNK potentiates TNF-stimulated necrosis by increasing the production of cytotoxic reactive oxygen species. Genes Dev. 2004, 18, 2905–2915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Harashima, N.; Moritani, T.; Huang, W.; Harada, M. The Roles of ROS and Caspases in TRAIL-Induced Apoptosis and Necroptosis in Human Pancreatic Cancer Cells. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0127386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Zhao, X.; Tang, M.; Li, L.; Lei, Y.; Cheng, P.; Guo, W.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, W.; Luo, N.; et al. The role of ROS and subsequent DNA-damage response in PUMA-induced apoptosis of ovarian cancer cells. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 23492–23506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liou, G.Y.; Storz, P. Reactive oxygen species in cancer. Free Radic. Res. 2010, 44, 479–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storz, P. Reactive oxygen species in tumor progression. Front. BioSci. 2005, 10, 1881–1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Guo, X.; Yang, N.; Huang, Z.; Huang, L.; Fang, Z.; Zhang, C.; Li, L.; Yu, C. Surface engineering strategies of gold nanomaterials and their applications in biomedicine and detection. J. Mater. Chem. B 2021, 9, 5583–5598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakr, T.M.; Korany, M.; Katti, K.V. Selenium nanomaterials in biomedicine—An overview of new opportunities in nanomedicine of selenium. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2018, 46, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehlenbacher, R.D.; Kolbl, R.; Lay, A.; Dionne, J.A. Nanomaterials for in vivo imaging of mechanical forces and electrical fields. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2017, 3, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musial, J.; Krakowiak, R.; Mlynarczyk, D.T.; Goslinski, T.; Stanisz, B.J. Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticles in Food and Personal Care Products-What Do We Know about Their Safety? Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmila, R.J.; Vance, S.A.; King, S.B.; Tsang, A.W.; Singh, R.; Furdui, C.M. Silver Nanoparticles Induce Mitochondrial Protein Oxidation in Lung Cells Impacting Cell Cycle and Proliferation. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drasler, B.; Sayre, P.; Steinhäuser, K.G.; Petri-Fink, A.; Rothen-Rutishauser, B. In vitro approaches to assess the hazard of nanomaterials. NanoImpact 2017, 8, 99–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.J.; Liu, J.; Ehrenshaft, M.; Roberts, J.E.; Fu, P.P.; Mason, R.P.; Zhao, B. Phototoxicity of nano titanium dioxides in HaCaT keratinocytes--generation of reactive oxygen species and cell damage. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2012, 263, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, P.C.; Yu, H.T.; Fu, P.P. Toxicity and Environmental Risks of Nanomaterials: Challenges and Future Needs. J. Environ. Sci. Health C 2009, 27, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daimon, T.; Nosaka, Y. Formation and behavior of singlet molecular oxygen in TiO2 photocatalysis studied by detection of near-infrared phosphorescence. J. Phys. Chem. C 2007, 111, 4420–4424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phaniendra, A.; Jestadi, D.B.; Periyasamy, L. Free Radicals: Properties, Sources, Targets, and Their Implication in Various Diseases. Indian J. Clin. Biochem. 2015, 30, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.; Liu, C.; Yang, D.; Zhang, H.; Xi, Z. Comparative study of cytotoxicity, oxidative stress and genotoxicity induced by four typical nanomaterials: The role of particle size, shape and composition. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2009, 29, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Sanders, S.; Aker, W.G.; Lin, Y.; Douglas, J.; Hwang, H.M. Assessing the effects of surface-bound humic acid on the phototoxicity of anatase and rutile TiO2 nanoparticles in vitro. J. Environ. Sci. 2016, 42, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, B.; Wang, H.; He, H.; Wu, Q.; Qin, X.; Yang, X.; Chen, L.; Xu, G.; Yuan, Z.; et al. Disruption of the superoxide anions-mitophagy regulation axis mediates copper oxide nanoparticles-induced vascular endothelial cell death. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2018, 129, 268–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onodera, A.; Nishiumi, F.; Kakiguchi, K.; Tanaka, A.; Tanabe, N.; Honma, A.; Yayama, K.; Yoshioka, Y.; Nakahira, K.; Yonemura, S.; et al. Short-term changes in intracellular ROS localisation after the silver nanoparticles exposure depending on particle size. Toxicol. Rep. 2015, 2, 574–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahamed, M.; Akhtar, M.J.; Raja, M.; Ahmad, I.; Siddiqui, M.K.; AlSalhi, M.S.; Alrokayan, S.A. ZnO nanorod-induced apoptosis in human alveolar adenocarcinoma cells via p53, survivin and bax/bcl-2 pathways: Role of oxidative stress. Nanomedicine 2011, 7, 904–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jimenez-Relinque, E.; Castellote, M. Hydroxyl radical and free and shallowly trapped electron generation and electron/hole recombination rates in TiO2 photocatalysis using different combinations of anatase and rutile. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2018, 565, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thit, A.; Selck, H.; Bjerregaard, H.F. Toxic mechanisms of copper oxide nanoparticles in epithelial kidney cells. Toxicol. In Vitro 2015, 29, 1053–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thubagere, A.; Reinhard, B.M. Nanoparticle-induced apoptosis propagates through hydrogen-peroxide-mediated bystander killing: Insights from a human intestinal epithelium in vitro model. ACS Nano 2010, 4, 3611–3622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Xu, K.; Ji, L.; Tang, B. Effect of gold nanoparticles on glutathione depletion-induced hydrogen peroxide generation and apoptosis in HL7702 cells. Toxicol. Lett. 2011, 205, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.X.; Fan, Y.B.; Gao, Y.; Hu, Q.H.; Wang, T.C. TiO2 nanoparticles translocation and potential toxicological effect in rats after intraarticular injection. Biomaterials 2009, 30, 4590–4600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, D.; Bi, H.; Liu, B.; Wu, Q.; Wang, D.; Cui, Y. Reactive oxygen species-induced cytotoxic effects of zinc oxide nanoparticles in rat retinal ganglion cells. Toxicol. In Vitro 2013, 27, 731–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, E.J.; Kim, S.; Kim, J.S.; Choi, I.H. Inflammasome formation and IL-1beta release by human blood monocytes in response to silver nanoparticles. Biomaterials 2012, 33, 6858–6867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirakawa, K.; Hirano, T. Singlet oxygen generation photocatalyzed by TiO2 particles and its contribution to biomolecule damage. Chem. Lett. 2006, 35, 832–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Jun, B.H. Silver Nanoparticles: Synthesis and Application for Nanomedicine. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Z.; Song, J.; Tian, R.; Yang, Z.; Yu, G.; Lin, L.; Zhang, G.; Fan, W.; Zhang, F.; Niu, G.; et al. Activatable Singlet Oxygen Generation from Lipid Hydroperoxide Nanoparticles for Cancer Therapy. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2017, 56, 6492–6496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdal Dayem, A.; Hossain, M.K.; Lee, S.B.; Kim, K.; Saha, S.K.; Yang, G.M.; Choi, H.Y.; Cho, S.G. The Role of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) in the Biological Activities of Metallic Nanoparticles. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kermanizadeh, A.; Jantzen, K.; Ward, M.B.; Durhuus, J.A.; Juel Rasmussen, L.; Loft, S.; Moller, P. Nanomaterial-induced cell death in pulmonary and hepatic cells following exposure to three different metallic materials: The role of autophagy and apoptosis. Nanotoxicology 2017, 11, 184–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, D.; Du, Q.; Ran, B.; Liu, X.; Wang, X.; Ma, X.; Cheng, F.; Sun, B. The neurotoxicity induced by engineered nanomaterials. Int. J. Nanomed. 2019, 14, 4167–4186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fridovich, I. Biological effects of the superoxide radical. Arch. BioChem. Biophys. 1986, 247, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apel, K.; Hirt, H. Reactive oxygen species: Metabolism, oxidative stress, and signal transduction. Annu. Rev. Plant. Biol. 2004, 55, 373–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntyre, M.; Bohr, D.F.; Dominiczak, A.F. Endothelial function in hypertension: The role of superoxide anion. Hypertension 1999, 34, 539–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bielski, B.H.J.; Cabelli, D.E. Superoxide and Hydroxyl Radical Chemistry in Aqueous Solution. Act. Oxyg. Chem. 1995, 2, 66–104. [Google Scholar]

- Ahsan, H.; Ali, A.; Ali, R. Oxygen free radicals and systemic autoimmunity. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2003, 131, 398–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, J.J.P.; Shin, D.S.; Getzoff, E.D.; Tainer, J.A. The structural biochemistry of the superoxide dismutases. Bba-Proteins Proteom. 2010, 1804, 245–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgstahl, G.E.O.; Oberley-Deegan, R.E. Superoxide Dismutases (SODs) and SOD Mimetics. Antioxidants 2018, 7, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landis, G.N.; Tower, J. Superoxide dismutase evolution and life span regulation. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2005, 126, 365–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loschen, G.; Flohe, L.; Chance, B. Respiratory Chain Linked H2o2 Production in Pigeon Heart Mitochondria. FEBS Lett. 1971, 18, 261–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loschen, G.; Azzi, A.; Richter, C.; Flohe, L. Superoxide Radicals as Precursors of Mitochondrial Hydrogen-Peroxide. FEBS Lett. 1974, 42, 68–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, D.F.; Erecinska, M.; Dutton, P.L. Thermodynamic Relationships in Mitochondrial Oxidative-Phosphorylation. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Bio 1974, 3, 203–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballard, J.W.; Youngson, N.A. Review: Can diet influence the selective advantage of mitochondrial DNA haplotypes? Biosci. Rep. 2015, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.B.; Fiskum, G.; Schubert, D. Generation of reactive oxygen species by the mitochondrial electron transport chain. J. NeuroChem. 2002, 80, 780–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kushnareva, Y.; Murphy, A.N.; Andreyev, A. Complex I-mediated reactive oxygen species generation: Modulation by cytochrome c and NAD(P)+ oxidation-reduction state. Biochem. J. 2002, 368, 545–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, M.P. How mitochondria produce reactive oxygen species. Biochem. J. 2009, 417, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wikstrom, M.K.; Berden, J.A. Oxidoreduction of cytochrome b in the presence of antimycin. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1972, 283, 403–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, F.; Crofts, A.R.; Kramer, D.M. Multiple Q-cycle bypass reactions at the Qo site of the cytochiome bc1 complex. Biochemistry 2002, 41, 7866–7874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bleier, L.; Drose, S. Superoxide generation by complex III: From mechanistic rationales to functional consequences. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2013, 1827, 1320–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grzelak, A.; Wojewodzka, M.; Meczynska-Wielgosz, S.; Zuberek, M.; Wojciechowska, D.; Kruszewski, M. Crucial role of chelatable iron in silver nanoparticles induced DNA damage and cytotoxicity. Redox Biol. 2018, 15, 435–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jayaram, D.T.; Payne, C.K. Intracellular Generation of Superoxide by TiO2 Nanoparticles Decreases Histone Deacetylase 9 (HDAC9), an Epigenetic Modifier. Bioconjug. Chem. 2020, 31, 1354–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masoud, R.; Bizouarn, T.; Trepout, S.; Wien, F.; Baciou, L.; Marco, S.; Houee Levin, C. Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticles Increase Superoxide Anion Production by Acting on NADPH Oxidase. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0144829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, M.J.; Kumar, S.; Alhadlaq, H.A.; Alrokayan, S.A.; Abu-Salah, K.M.; Ahamed, M. Dose-dependent genotoxicity of copper oxide nanoparticles stimulated by reactive oxygen species in human lung epithelial cells. Toxicol. Ind. Health 2016, 32, 809–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piret, J.P.; Jacques, D.; Audinot, J.N.; Mejia, J.; Boilan, E.; Noel, F.; Fransolet, M.; Demazy, C.; Lucas, S.; Saout, C.; et al. Copper (II) oxide nanoparticles penetrate into HepG2 cells, exert cytotoxicity via oxidative stress and induce pro-inflammatory response. Nanoscale 2012, 4, 7168–7184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piao, M.J.; Kang, K.A.; Lee, I.K.; Kim, H.S.; Kim, S.; Choi, J.Y.; Choi, J.; Hyun, J.W. Silver nanoparticles induce oxidative cell damage in human liver cells through inhibition of reduced glutathione and induction of mitochondria-involved apoptosis. Toxicol. Lett. 2011, 201, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zielonka, J.; Srinivasan, S.; Hardy, M.; Ouari, O.; Lopez, M.; Vasquez-Vivar, J.; Avadhani, N.G.; Kalyanaraman, B. Cytochrome c-mediated oxidation of hydroethidine and mito-hydroethidine in mitochondria: Identification of homo- and heterodimers. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2008, 44, 835–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Ross, M.F.; Kelso, G.F.; Blaikie, F.H.; James, A.M.; Cocheme, H.M.; Filipovska, A.; Da Ros, T.; Hurd, T.R.; Smith, R.A.J.; Murphy, M.P. Lipophilic triphenylphosphonium cations as tools in mitochondrial bioenergetics and free radical biology. Biochemistry 2005, 70, 222–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, K.M.; Janes, M.S.; Pehar, M.; Monette, J.S.; Ross, M.F.; Hagen, T.M.; Murphy, M.P.; Beckman, J.S. Selective fluorescent imaging of superoxide in vivo using ethidium-based probes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 15038–15043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kauffman, M.E.; Kauffman, M.K.; Traore, K.; Zhu, H.; Trush, M.A.; Jia, Z.; Li, Y.R. MitoSOX-Based Flow Cytometry for Detecting Mitochondrial ROS. React. Oxyg. Species 2016, 2, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhopadhyay, P.; Rajesh, M.; Yoshihiro, K.; Hasko, G.; Pacher, P. Simple quantitative detection of mitochondrial superoxide production in live cells. BioChem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2007, 358, 203–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roelofs, B.A.; Ge, S.X.; Studlack, P.E.; Polster, B.M. Low micromolar concentrations of the superoxide probe MitoSOX uncouple neural mitochondria and inhibit complex IV. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2015, 86, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohyashiki, T.; Nunomura, M.; Katoh, T. Detection of superoxide anion radical in phospholipid liposomal membrane by fluorescence quenching method using 1,3-diphenylisobenzofuran. Bba-Biomembranes 1999, 1421, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krieg, M. Determination of singlet oxygen quantum yields with 1,3-diphenylisobenzofuran in model membrane systems. J. BioChem. Biophys. Methods 1993, 27, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamojc, K.; Zdrowowicz, M.; Rudnicki-Velasquez, P.B.; Krzyminski, K.; Zaborowski, B.; Niedzialkowski, P.; Jacewicz, D.; Chmurzynski, L. The development of 1,3-diphenylisobenzofuran as a highly selective probe for the detection and quantitative determination of hydrogen peroxide. Free Radic. Res. 2017, 51, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andresen, M.; Regueira, T.; Bruhn, A.; Perez, D.; Strobel, P.; Dougnac, A.; Marshall, G.; Leighton, F. Lipoperoxidation and protein oxidative damage exhibit different kinetics during septic shock. Mediat. Inflamm. 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, D.F.; Cederbaum, A.I. Alcohol, oxidative stress, and free radical damage. Alcohol. Res. Health 2003, 27, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Halliwell, B.; Chirico, S. Lipid-Peroxidation ― Its Mechanism, Measurement, and Significance. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1993, 57, 715–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, L. Kinetic study of hydroxyl radical formation in a continuous hydroxyl generation system. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 40632–40638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kehrer, J.P. The Haber-Weiss reaction and mechanisms of toxicity. Toxicology 2000, 149, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, J.; Bielski, B.H.J. Kinetics of the Interaction of Ho2 and O2-Radicals with Hydrogen-Peroxide—Haber-Weiss Reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1979, 101, 58–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koppenol, W.H. The Haber-Weiss cycle—70 years later. Redox Rep. 2001, 6, 229–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischbacher, A.; von Sonntag, C.; Schmidt, T.C. Hydroxyl radical yields in the Fenton process under various pH, ligand concentrations and hydrogen peroxide/Fe (II) ratios. Chemosphere 2017, 182, 738–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Zhang, H.; Liu, H.; Yuan, Q.; Ren, F.; Han, Y.; Sun, Q.; Li, Z.; Gao, M. Boosting H2O2-Guided Chemodynamic Therapy of Cancer by Enhancing Reaction Kinetics through Versatile Biomimetic Fenton Nanocatalysts and the Second Near-Infrared Light Irradiation. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2019, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Hao, S.J.; Han, A.L.; Yang, Y.Y.; Fang, G.Z.; Liu, J.F.; Wang, S. Intracellular Fenton reaction based on mitochondria-targeted copper (II)-peptide complex for induced apoptosis. J. Mater. Chem. B 2019, 7, 4008–4016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackenberg, S.; Scherzed, A.; Technau, A.; Kessler, M.; Froelich, K.; Ginzkey, C.; Koehler, C.; Burghartz, M.; Hagen, R.; Kleinsasser, N. Cytotoxic, genotoxic and pro-inflammatory effects of zinc oxide nanoparticles in human nasal mucosa cells in vitro. Toxicol. In Vitro 2011, 25, 657–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekici, S.; Turkarslan, S.; Pawlik, G.; Dancis, A.; Baliga, N.S.; Koch, H.G.; Daldal, F. Intracytoplasmic copper homeostasis controls cytochrome c oxidase production. mBio 2014, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Chen, H.; Dong, Y.; Luo, X.; Yu, H.; Moore, Z.; Bey, E.A.; Boothman, D.A.; Gao, J. Superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles: Amplifying ROS stress to improve anticancer drug efficacy. Theranostics 2013, 3, 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehman, S.E.; Morris, A.S.; Mueller, P.S.; Salem, A.K.; Grassian, V.H.; Larsen, S.C. Silica nanoparticle-generated ROS as a predictor of cellular toxicity: Mechanistic insights and safety by design. Environ. Sci-Nano 2016, 3, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chairuangkitti, P.; Lawanprasert, S.; Roytrakul, S.; Aueviriyavit, S.; Phummiratch, D.; Kulthong, K.; Chanvorachote, P.; Maniratanachote, R. Silver nanoparticles induce toxicity in A549 cells via ROS-dependent and ROS-independent pathways. Toxicol. In Vitro 2013, 27, 330–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, X.W.; Mark, G.; von Sonntag, C. OH radical formation by ultrasound in aqueous solutions Part І: The chemistry underlying the terephthalate dosimeter. Ultrason. SonoChem. 1996, 3, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, E.B.; Unthank, J.K.; Castillo-Melendez, M.; Miller, S.L.; Langford, S.J.; Walker, D.W. Novel method for in vivo hydroxyl radical measurement by microdialysis in fetal sheep brain in utero. J. Appl. Physiol. 2005, 98, 2304–2310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Yapici, N.B.; Jockusch, S.; Moscatelli, A.; Mandalapu, S.R.; Itagaki, Y.; Bates, D.K.; Wiseman, S.; Gibson, K.M.; Turro, N.J.; Bi, L.R. New Rhodamine Nitroxide Based Fluorescent Probes for Intracellular Hydroxyl Radical Identification in Living Cells. Org. Lett. 2012, 14, 50–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.Y.; Huang, Y.Y.; Lu, M.Y.; Yang, D. HKOH-1: A Highly Sensitive and Selective Fluorescent Probe for Detecting Endogenous Hydroxyl Radicals in Living Cells. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 12873–12877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Guo, H.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, X.; Liu, Y. Non-photochemical production of singlet oxygen via activation of persulfate by carbon nanotubes. Water Res. 2017, 113, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cadenas, E. Biochemistry of Oxygen-Toxicity. Annu. Rev. BioChem. 1989, 58, 79–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agnez-Lima, L.F.; Melo, J.T.A.; Silva, A.E.; Oliveira, A.H.S.; Timoteo, A.R.S.; Lima-Bessa, K.M.; Martinez, G.R.; Medeiros, M.H.G.; Di Mascio, P.; Galhardo, R.S.; et al. DNA damage by singlet oxygen and cellular protective mechanisms. Mutat. Res. Rev. Mutat. 2012, 751, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hampton, M.B.; Kettle, A.J.; Winterbourn, C.C. Inside the neutrophil phagosome: Oxidants, myeloperoxidase, and bacterial killing. Blood 1998, 92, 3007–3017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bigot, E.; Bataille, R.; Patrice, T. Increased singlet oxygen-induced secondary ROS production in the serum of cancer patients. J. PhotoChem. PhotoBiol. B 2012, 107, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sies, H.; Menck, C.F.M. Singlet Oxygen Induced DNA Damage. Mutat Res. 1992, 275, 367–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanofsky, J.R. Singlet Oxygen Production by Biological-Systems. Chem. Biol. Interact. 1989, 70, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumont, E.; Gruber, R.; Bignon, E.; Morell, C.; Moreau, Y.; Monari, A.; Ravanat, J.L. Probing the reactivity of singlet oxygen with purines. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, M.J. Singlet oxygen-mediated damage to proteins and its consequences. BioChem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2003, 305, 761–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gracanin, M.; Hawkins, C.L.; Pattison, D.I.; Davies, M.J. Singlet-oxygen-mediated amino acid and protein oxidation: Formation of tryptophan peroxides and decomposition products. Free Radic. Bio Med. 2009, 47, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirakawa, T.; Nosaka, Y. Properties of O2.− and OH center dot formed in TiO2 aqueous suspensions by photocatalytic reaction and the influence of H2O2 and some ions. Langmuir 2002, 18, 3247–3254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.Y.; Lee, S.M.; Park, J.W. Antioxidant enzyme inhibitors enhance singlet oxygen-induced cell death in HL-60 cells. Free Radic. Res. 2006, 40, 1190–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, J.; Liu, F.; Wang, L.; An, Y.; Gao, M.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, Y. Hypoxia- and singlet oxygen-responsive chemo-photodynamic Micelles featured with glutathione depletion and aldehyde production. Biomater. Sci. 2018, 7, 429–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.Y.; Lee, S.M.; Tak, J.K.; Choi, K.S.; Kwon, T.K.; Park, J.W. Regulation of singlet oxygen-induced apoptosis by cytosolic NADP+-dependent isocitrate dehydrogenase. Mol. Cell Biochem. 2007, 302, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umezawa, N.; Tanaka, K.; Urano, Y.; Kikuchi, K.; Higuchi, T.; Nagano, T. Novel Fluorescent Probes for Singlet Oxygen. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1999, 38, 2899–2901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brega, V.; Yan, Y.; Thomas, S.W., 3rd. Acenes beyond organic electronics: Sensing of singlet oxygen and stimuli-responsive materials. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2020, 18, 9191–9209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz-Gonzalez, R.; Bresoli-Obach, R.; Gulias, O.; Agut, M.; Savoie, H.; Boyle, R.W.; Nonell, S.; Giuntini, F. NanoSOSG: A Nanostructured Fluorescent Probe for the Detection of Intracellular Singlet Oxygen. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2017, 56, 2885–2888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lennicke, C.; Rahn, J.; Lichtenfels, R.; Wessjohann, L.A.; Seliger, B. Hydrogen peroxide—Production, fate and role in redox signaling of tumor cells. Cell Commun. Signal. 2015, 13, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hossain, M.A.; Bhattacharjee, S.; Armin, S.M.; Qian, P.; Xin, W.; Li, H.Y.; Burritt, D.J.; Fujita, M.; Tran, L.S. Hydrogen peroxide priming modulates abiotic oxidative stress tolerance: Insights from ROS detoxification and scavenging. Front. Plant. Sci. 2015, 6, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halliwell, B.; Clement, M.V.; Long, L.H. Hydrogen peroxide in the human body. FEBS Lett. 2000, 486, 10–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mates, J.M.; Perez-Gomez, C.; De Castro, I.N. Antioxidant enzymes and human diseases. Clin. Biochem. 1999, 32, 595–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angermuller, S.; Islinger, M.; Volkl, A. Peroxisomes and reactive oxygen species, a lasting challenge. HistoChem. Cell Biol. 2009, 131, 459–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topo, E.; Fisher, G.; Sorricelli, A.; Errico, F.; Usiello, A.; D’Aniello, A. Thyroid hormones and D-aspartic acid, D-aspartate oxidase, D-aspartate racemase, H2O2, and ROS in rats and mice. Chem. Biodivers. 2010, 7, 1467–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Royall, J.A.; Ischiropoulos, H. Evaluation of 2’,7’-Dichlorofluorescin and Dihydrorhodamine 123 as Fluorescent-Probes for Intracellular H2o2 in Cultured Endothelial-Cells. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1993, 302, 348–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rastogi, R.P.; Singh, S.P.; Hader, D.P.; Sinha, R.P. Detection of reactive oxygen species (ROS) by the oxidant-sensing probe 2’,7’-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate in the cyanobacterium Anabaena variabilis PCC 7937. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2010, 397, 603–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes, A.; Fernandes, E.; Lima, J.L.F.C. Fluorescence probes used for detection of reactive oxygen species. J. Biochem. Bioph Meth. 2005, 65, 45–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crow, J.P. Dichlorodihydrofluorescein and dihydrorhodamine 123 are sensitive indicators of peroxynitrite in vitro: Implications for intracellular measurement of reactive nitrogen and oxygen species. Nitric Oxide 1997, 1, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chignell, C.F.; Sik, R.H. A photochemical study of cells loaded with 2’,7’-dichlorofluorescin: Implications for the detection of reactive oxygen species generated during UVA irradiation. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2003, 34, 1029–1034. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhu, H.; Bannenberg, G.L.; Moldeus, P.; Shertzer, H.G. Oxidation pathways for the intracellular probe 2’,7’-dichlorofluorescein. Arch. Toxicol. 1994, 68, 582–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebel, C.P.; Ischiropoulos, H.; Bondy, S.C. Evaluation of the Probe 2’,7’-Dichlorofluorescin as an Indicator of Reactive Oxygen Species Formation and Oxidative Stress. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 1992, 5, 227–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, I.L.; Huang, Y.J. Titanium Oxide Shell Coatings Decrease the Cytotoxicity of ZnO Nanoparticles. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2011, 24, 303–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akhtar, M.J.; Ahamed, M.; Kumar, S.; Khan, M.M.; Ahmad, J.; Alrokayan, S.A. Zinc oxide nanoparticles selectively induce apoptosis in human cancer cells through reactive oxygen species. Int. J. Nanomed. 2012, 7, 845–857. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, V.; Anderson, D.; Dhawan, A. Zinc oxide nanoparticles induce oxidative DNA damage and ROS-triggered mitochondria mediated apoptosis in human liver cells (HepG2). Apoptosis 2012, 17, 852–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Setyawati, M.I.; Tay, C.Y.; Leong, D.T. Effect of zinc oxide nanomaterials-induced oxidative stress on the p53 pathway. Biomaterials 2013, 34, 10133–10142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliakbari, F.; Haji Hosseinali, S.; Khalili Sarokhalil, Z.; Shahpasand, K.; Akbar Saboury, A.; Akhtari, K.; Falahati, M. Reactive oxygen species generated by titanium oxide nanoparticles stimulate the hemoglobin denaturation and cytotoxicity against human lymphocyte cell. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2019, 37, 4875–4881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharya, K.; Davoren, M.; Boertz, J.; Schins, R.P.; Hoffmann, E.; Dopp, E. Titanium dioxide nanoparticles induce oxidative stress and DNA-adduct formation but not DNA-breakage in human lung cells. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2009, 6, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Xu, L.; Zhang, T.; Ren, G.; Yang, Z. Oxidative stress and apoptosis induced by nanosized titanium dioxide in PC12 cells. Toxicology 2010, 267, 172–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, E.J.; Yi, J.; Chung, K.H.; Ryu, D.Y.; Choi, J.; Park, K. Oxidative stress and apoptosis induced by titanium dioxide nanoparticles in cultured BEAS-2B cells. Toxicol. Lett. 2008, 180, 222–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miwa, S.; Treumann, A.; Bell, A.; Vistoli, G.; Nelson, G.; Hay, S.; von Zglinicki, T. Carboxylesterase converts Amplex red to resorufin: Implications for mitochondrial H2O2 release assays. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2016, 90, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, A.; Romero, R.; Petty, H.R. A sensitive fluorimetric assay for pyruvate. Anal. BioChem. 2010, 396, 146–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Towne, V.; Will, M.; Oswald, B.; Zhao, Q.J. Complexities in horseradish peroxidase-catalyzed oxidation of dihydroxyphenoxazine derivatives: Appropriate ranges for pH values and hydrogen peroxide concentrations in quantitative analysis. Anal. Biochem. 2004, 334, 290–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Debski, D.; Smulik, R.; Zielonka, J.; Michalowski, B.; Jakubowska, M.; Debowska, K.; Adamus, J.; Marcinek, A.; Kalyanaraman, B.; Sikora, A. Mechanism of oxidative conversion of Amplex (R) Red to resorufin: Pulse radiolysis and enzymatic studies. Free Radic. Bio Med. 2016, 95, 323–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niethammer, P.; Grabher, C.; Look, A.T.; Mitchison, T.J. A tissue-scale gradient of hydrogen peroxide mediates rapid wound detection in zebrafish. Nature 2009, 459, 996–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maeda, H.; Fukuyasu, Y.; Yoshida, S.; Fukuda, M.; Saeki, K.; Matsuno, H.; Yamauchi, Y.; Yoshida, K.; Hirata, K.; Miyamoto, K. Fluorescent probes for hydrogen peroxide based on a non-oxidative mechanism. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2004, 43, 2389–2391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolfbeis, O.S.; Durkop, A.; Wu, M.; Lin, Z.H. A europium-ion-based luminescent sensing probe for hydrogen peroxide. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2002, 41, 4495–4498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staniek, K.; Nohl, H. H2O2 detection from intact mitochondria as a measure for one-electron reduction of dioxygen requires a non-invasive assay system. Bba-Bioenergetics 1999, 1413, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartosz, G. Use of spectroscopic probes for detection of reactive oxygen species. Clin. Chim. Acta 2006, 368, 53–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammadinejad, R.; Moosavi, M.A.; Tavakol, S.; Vardar, D.O.; Hosseini, A.; Rahmati, M.; Dini, L.; Hussain, S.; Mandegary, A.; Klionsky, D.J. Necrotic, apoptotic and autophagic cell fates triggered by nanoparticles. Autophagy 2019, 15, 4–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mittler, R.; Vanderauwera, S.; Suzuki, N.; Miller, G.; Tognetti, V.B.; Vandepoele, K.; Gollery, M.; Shulaev, V.; Van Breusegem, F. ROS signaling: The new wave? Trends Plant. Sci. 2011, 16, 300–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, X.; Vikash, V.; Ye, Q.; Wu, D.; Liu, Y.; Dong, W. ROS and ROS-Mediated Cellular Signaling. Oxid Med. Cell Longev. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bae, Y.S.; Oh, H.; Rhee, S.G.; Yoo, Y.D. Regulation of reactive oxygen species generation in cell signaling. Mol. Cells 2011, 32, 491–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonizzi, G.; Karin, M. The two NF-kappaB activation pathways and their role in innate and adaptive immunity. Trends Immunol. 2004, 25, 280–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaul, N.; Gopalakrishna, R.; Gundimeda, U.; Choi, J.; Forman, H.J. Role of protein kinase C in basal and hydrogen peroxide-stimulated NF-kappa B activation in the murine macrophage J774A.1 cell line. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1998, 350, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, K.N.; Amstad, P.; Cerutti, P.; Baeuerle, P.A. The roles of hydrogen peroxide and superoxide as messengers in the activation of transcription factor NF-kappa B. Chem. Biol. 1995, 2, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoonbroodt, S.; Ferreira, V.; Best-Belpomme, M.; Boelaert, J.R.; Legrand-Poels, S.; Korner, M.; Piette, J. Crucial role of the amino-terminal tyrosine residue 42 and the carboxyl-terminal PEST domain of I kappa B alpha in NF-kappa B activation by an oxidative stress. J. Immunol. 2000, 164, 4292–4300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takada, Y.; Mukhopadhyay, A.; Kundu, G.C.; Mahabeleshwar, G.H.; Singh, S.; Aggarwal, B.B. Hydrogen peroxide activates NF-kappa B through tyrosine phosphorylation of I kappa B alpha and serine phosphorylation of p65: Evidence for the involvement of I kappa B alpha kinase and Syk protein-tyrosine kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 24233–24241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Lu, B.; Fu, J.; Zhu, X.; Song, E.; Song, Y. Amorphous silica nanoparticles induce inflammation via activation of NLRP3 inflammasome and HMGB1/TLR4/MYD88/NF-kb signaling pathway in HUVEC cells. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 404, 124050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyriakis, J.M.; Avruch, J. Sounding the alarm: Protein kinase cascades activated by stress and inflammation. J. Biol. Chem. 1996, 271, 24313–24316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakano, H.; Nakajima, A.; Sakon-Komazawa, S.; Piao, J.H.; Xue, X.; Okumura, K. Reactive oxygen species mediate crosstalk between NF-kappaB and JNK. Cell Death Differ. 2006, 13, 730–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, M.; Forman, H.J. Redox signaling and the MAP kinase pathways. Biofactors 2003, 17, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dabrowski, A.; Boguslowicz, C.; Dabrowska, M.; Tribillo, I.; Gabryelewicz, A. Reactive oxygen species activate mitogen-activated protein kinases in pancreatic acinar cells. Pancreas 2000, 21, 376–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guyton, K.Z.; Liu, Y.; Gorospe, M.; Xu, Q.; Holbrook, N.J. Activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase by H2O2. Role in cell survival following oxidant injury. J. Biol. Chem. 1996, 271, 4138–4142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, N.; Torii, S.; Saito, N.; Hosaka, M.; Takeuchi, T. Reactive oxygen species-mediated pancreatic beta-cell death is regulated by interactions between stress-activated protein kinases, p38 and c-Jun N-terminal kinase, and mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatases. Endocrinology 2008, 149, 1654–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, B.H.; Hur, E.M.; Lee, J.H.; Jun, D.J.; Kim, K.T. Protein kinase Cdelta-mediated proteasomal degradation of MAP kinase phosphatase-1 contributes to glutamate-induced neuronal cell death. J. Cell Sci. 2006, 119, 1329–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuzawa, A.; Saegusa, K.; Noguchi, T.; Sadamitsu, C.; Nishitoh, H.; Nagai, S.; Koyasu, S.; Matsumoto, K.; Takeda, K.; Ichijo, H. ROS-dependent activation of the TRAF6-ASK1-p38 pathway is selectively required for TLR4-mediated innate immunity. Nat. Immunol. 2005, 6, 587–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pitzschke, A.; Djamei, A.; Bitton, F.; Hirt, H. A Major Role of the MEKK1-MKK1/2-MPK4 Pathway in ROS Signalling. Mol. Plant. 2009, 2, 120–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lluis, J.M.; Buricchi, F.; Chiarugi, P.; Morales, A.; Fernandez-Checa, J.C. Dual role of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species in hypoxia signaling: Activation of nuclear factor-kB via c-SRC and oxidant-dependent cell death. Cancer Res. 2007, 67, 7368–7377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, J.; Ramachandiran, S.; Tikoo, K.; Jia, Z.; Lau, S.S.; Monks, T.J. EGFR-independent activation of p38 MAPK and EGFR-dependent activation of ERK1/2 are required for ROS-induced renal cell death. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2004, 287, 1049–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forman, H.J.; Torres, M. Reactive oxygen species and cell signaling: Respiratory burst in macrophage signaling. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2002, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, G.; Guo, W.; Han, L.; Chen, E.; Kong, L.; Wang, L.; Ai, W.; Song, N.; Li, H.; Chen, H. Cerium oxide nanoparticles induce cytotoxicity in human hepatoma SMMC-7721 cells via oxidative stress and the activation of MAPK signaling pathways. Toxicol. In Vitro 2013, 27, 1082–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, C.; Xia, Y.; Niu, P.; Jiang, L.; Duan, J.; Yu, Y.; Zhou, X.; Li, Y.; Sun, Z. Silica nanoparticles induce oxidative stress, inflammation, and endothelial dysfunction in vitro via activation of the MAPK/Nrf2 pathway and nuclear factor-kappaB signaling. Int. J. Nanomed. 2015, 10, 1463–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, R.; Ho, Y.S.; Hung, C.H.; Liu, Y.; Huang, C.X.; Chan, H.N.; Ho, S.L.; Lui, S.Y.; Li, H.W.; Chang, R.C. Silica nanoparticles induce neurodegeneration-like changes in behavior, neuropathology, and affect synapse through MAPK activation. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2018, 15, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Wang, H.; He, C.; Jin, Y.; Fu, Z. Polystyrene nanoparticles trigger the activation of p38 MAPK and apoptosis via inducing oxidative stress in zebrafish and macrophage cells. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 269, 116075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Ji, J.; Ji, L.; Wang, L.; Hong, F. Respiratory exposure to nano-TiO2 induces pulmonary toxicity in mice involving reactive free radical-activated TGF-beta/Smad/p38MAPK/Wnt pathways. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2019, 107, 2567–2575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi, C.; Liu, D.; Fong, C.C.; Zhang, J.; Yang, M. Gold nanoparticles promote osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells through p38 MAPK pathway. ACS Nano 2010, 4, 6439–6448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Chen, B.; Cao, M.; Sun, J.; Wu, H.; Zhao, P.; Xing, J.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Ji, M.; et al. Response of MAPK pathway to iron oxide nanoparticles in vitro treatment promotes osteogenic differentiation of hBMSCs. Biomaterials 2016, 86, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vousden, K.H.; Lu, X. Live or let die: The cell’s response to p53. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2002, 2, 594–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Chen, Y.; St Clair, D.K. ROS and p53: A versatile partnership. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2008, 44, 1529–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.X.; Li, X.W.; Li, Y.; Li, N.; Shi, X.X.; Ding, H.Y.; Zhang, Y.H.; Li, X.B.; Liu, G.W.; Wang, Z. Non-esterified fatty acids activate the ROS-p38-p53/Nrf2 signaling pathway to induce bovine hepatocyte apoptosis in vitro. Apoptosis 2014, 19, 984–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakano, K.; Vousden, K.H. PUMA, a novel proapoptotic gene, is induced by p53. Mol. Cell 2001, 7, 683–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.R.; Yuan, B.; Zhang, L.; Mu, W.M.; Wang, C.M. ROS/p38/p53/Puma signaling pathway is involved in emodin-induced apoptosis of human colorectal cancer cells. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 2015, 8, 15413–15422. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yu, J.; Zhang, L. PUMA, a potent killer with or without p53. Oncogene 2008, 27, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samuelsen, J.T.; Dahl, J.E.; Karlsson, S.; Morisbak, E.; Becher, R. Apoptosis induced by the monomers HEMA and TEGDMA involves formation of ROS and differential activation of the MAP-kinases p38, JNK and ERK. Dent. Mater. 2007, 23, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakon, S.; Xue, X.; Takekawa, M.; Sasazuki, T.; Okazaki, T.; Kojima, Y.; Piao, J.H.; Yagita, H.; Okumura, K.; Doi, T.; et al. NF-kappaB inhibits TNF-induced accumulation of ROS that mediate prolonged MAPK activation and necrotic cell death. Embo J. 2003, 22, 3898–3909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamata, H.; Honda, S.; Maeda, S.; Chang, L.; Hirata, H.; Karin, M. Reactive oxygen species promote TNFalpha-induced death and sustained JNK activation by inhibiting MAP kinase phosphatases. Cell 2005, 120, 649–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akcan, R.; Aydogan, H.C.; Yildirim, M.S.; Tastekin, B.; Saglam, N. Nanotoxicity: A challenge for future medicine. Turk. J. Med. Sci. 2020, 50, 1180–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham, U.M.; Dozier, A.K.; Oberdorster, G.; Yokel, R.A.; Molina, R.; Brain, J.D.; Pinto, J.M.; Weuve, J.; Bennett, D.A. Tissue Specific Fate of Nanomaterials by Advanced Analytical Imaging Techniques—A Review. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2020, 33, 1145–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pu, S.; Gong, C.; Robertson, A.W. Liquid cell transmission electron microscopy and its applications. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2020, 7, 191204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiio, T.M.; Park, S. Nano-scientific Application of Atomic Force Microscopy in Pathology: From Molecules to Tissues. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2020, 17, 844–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erofeev, A.; Gorelkin, P.; Garanina, A.; Alova, A.; Efremova, M.; Vorobyeva, N.; Edwards, C.; Korchev, Y.; Majouga, A. Novel method for rapid toxicity screening of magnetic nanoparticles. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 7462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, L.; Williams, A.; Gelda, K.; Nikota, J.; Wu, D.; Vogel, U.; Halappanavar, S. 21st Century Tools for Nanotoxicology: Transcriptomic Biomarker Panel and Precision-Cut Lung Slice Organ Mimic System for the Assessment of Nanomaterial-Induced Lung Fibrosis. Small 2020, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohl, Y.; Runden-Pran, E.; Mariussen, E.; Hesler, M.; El Yamani, N.; Longhin, E.M.; Dusinska, M. Genotoxicity of Nanomaterials: Advanced In Vitro Models and High Throughput Methods for Human Hazard Assessment-A Review. Nanomaterials (Basel) 2020, 10, 1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Xu, C.; Jiang, L.; Qin, J. A 3D human lung-on-a-chip model for nanotoxicity testing. Toxicol. Res. 2018, 7, 1048–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, F.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, M.; Yu, H.; Chen, W.; Qin, J. A 3D human placenta-on-a-chip model to probe nanoparticle exposure at the placental barrier. Toxicol. In Vitro 2019, 54, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Duinen, V.; Trietsch, S.J.; Joore, J.; Vulto, P.; Hankemeier, T. Microfluidic 3D cell culture: From tools to tissue models. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2015, 35, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Nanomaterial | Produced ROS | ROS | Half-Life |

|---|---|---|---|

| ZnO [29], SiO2 [29], TiO2 [30], CuO [31], Ag NPs [32] | Superoxide | O2●− | 10−6 s |

| ZnO [33], TiO2 [34], CuO [35] | Hydroxyl radical | ●OH | 10−10 s |

| Polystyrene NPs [36], Au NPs [37], TiO2 [38], ZnO [39], Ag NPs [40] | Hydrogen peroxide | H2O2 | Stable (x.s, min) |

| TiO2 [41], Ag NPs [42], FeO [43] | Singlet oxygen | 1O2 | 10−6 s |

| Type of ROS | Fluorescent Probe | Excitation/Emission Wavelengths |

|---|---|---|

| Superoxide | MitoSox | 535/610 nm |

| 1,3–diphenylisobenzofuran | 410/455 nm | |

| Hydroxyl radical | Terephthalic acid | 310/420 nm |

| Rhodamine nitroxide | 560/588 nm | |

| HKOH-1 | 500/520 nm | |

| Singlet oxygen | DPAX-1 | 495/515 nm |

| DMAX | 495/515 nm | |

| Singlet Oxygen Sensor Green® | 504/525 nm | |

| Hydrogen peroxide | 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein | 498/522 nm |

| Amplex Red | 563/587 nm | |

| HyPer ratiometric sensor | 485/516 nm | |

| Pentafluorobenzenesulfonyl fluoresceins | 485/530 nm | |

| Europium ion | 400/616 nm | |

| Homovanilic acid | 312/420 nm |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Čapek, J.; Roušar, T. Detection of Oxidative Stress Induced by Nanomaterials in Cells—The Roles of Reactive Oxygen Species and Glutathione. Molecules 2021, 26, 4710. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26164710

Čapek J, Roušar T. Detection of Oxidative Stress Induced by Nanomaterials in Cells—The Roles of Reactive Oxygen Species and Glutathione. Molecules. 2021; 26(16):4710. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26164710

Chicago/Turabian StyleČapek, Jan, and Tomáš Roušar. 2021. "Detection of Oxidative Stress Induced by Nanomaterials in Cells—The Roles of Reactive Oxygen Species and Glutathione" Molecules 26, no. 16: 4710. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26164710

APA StyleČapek, J., & Roušar, T. (2021). Detection of Oxidative Stress Induced by Nanomaterials in Cells—The Roles of Reactive Oxygen Species and Glutathione. Molecules, 26(16), 4710. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26164710