Oligomerization of 3,5-Dimethyl Benzyl Alcohol Promoted by Clay: Experimental and Theoretical Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

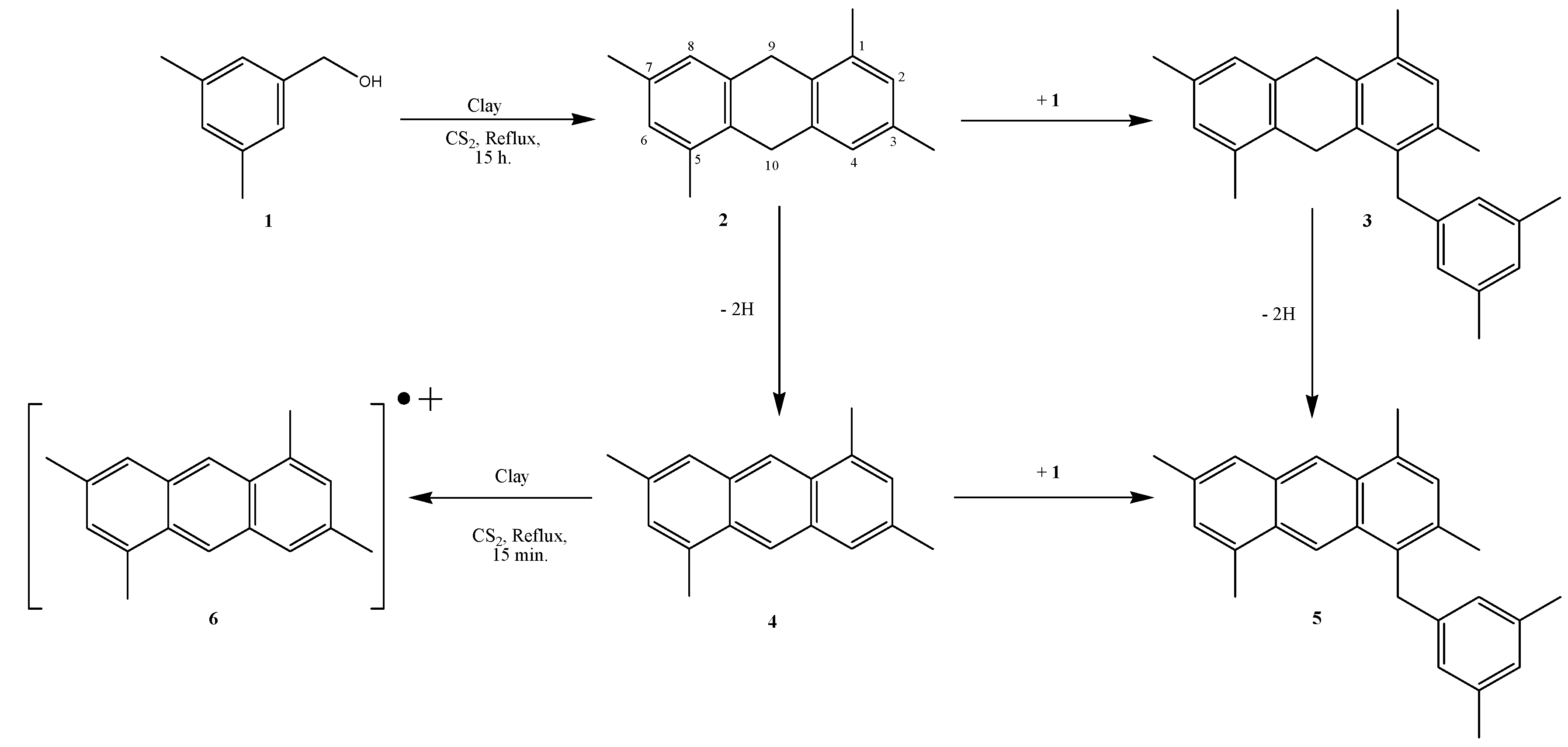

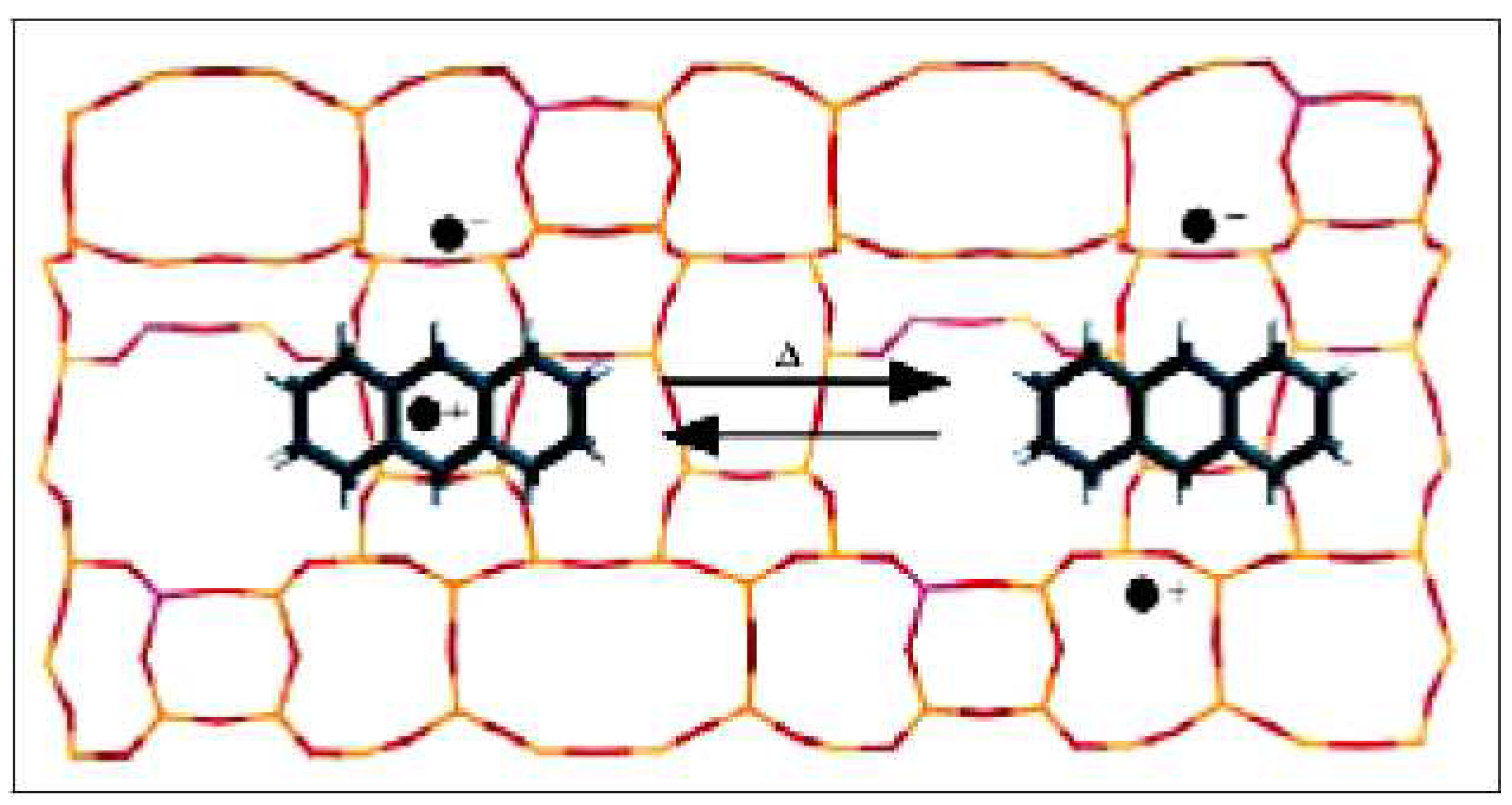

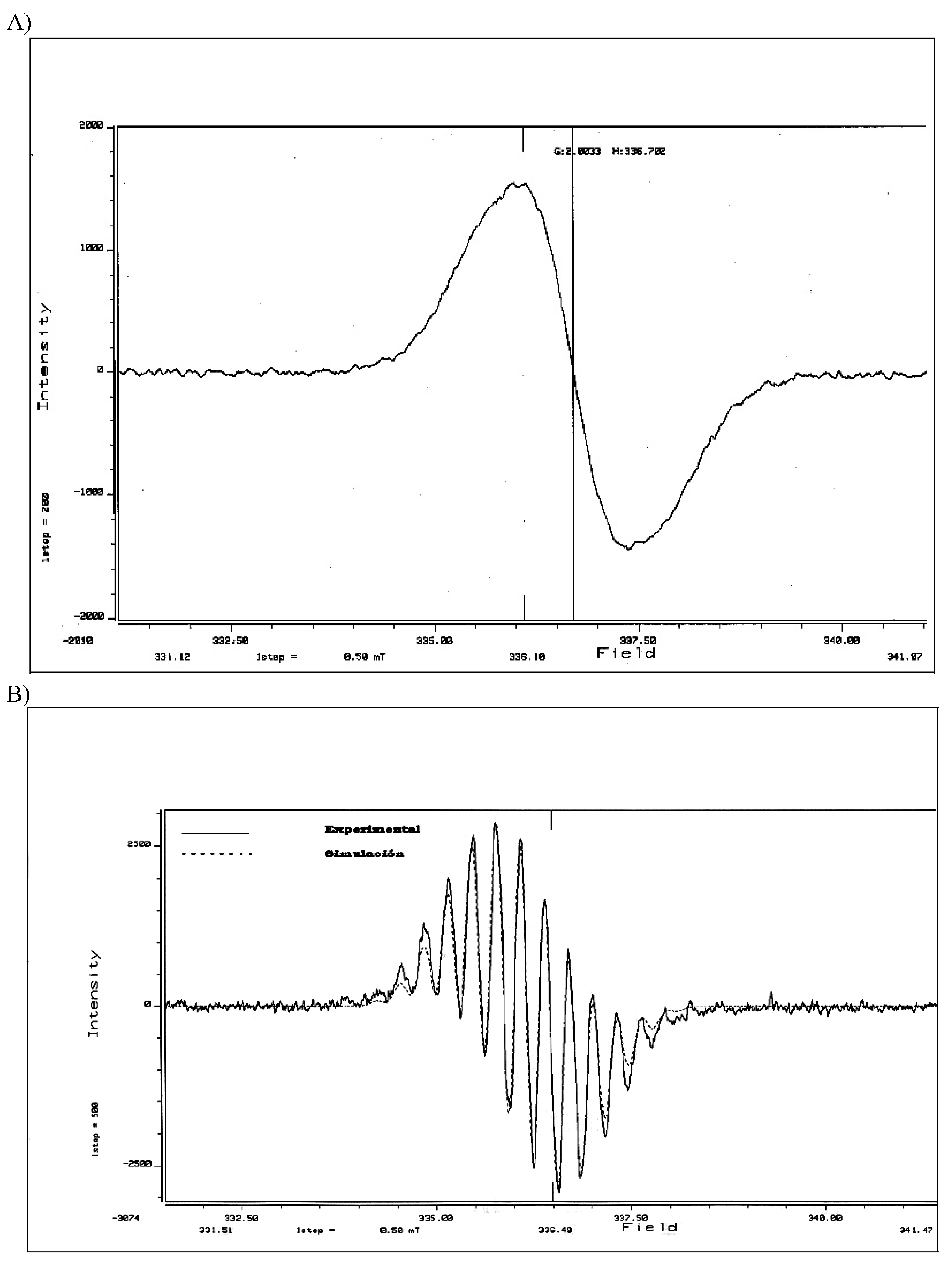

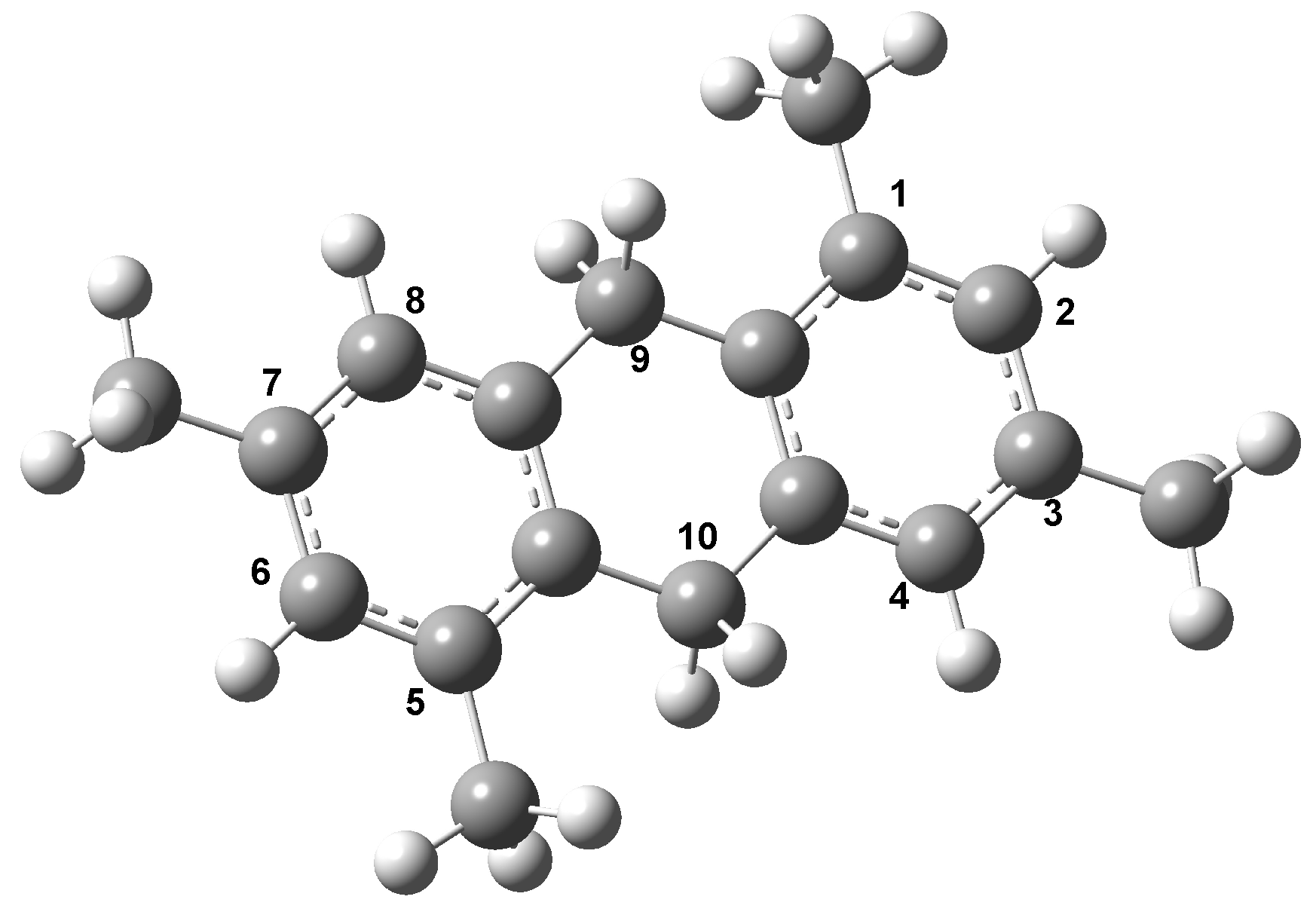

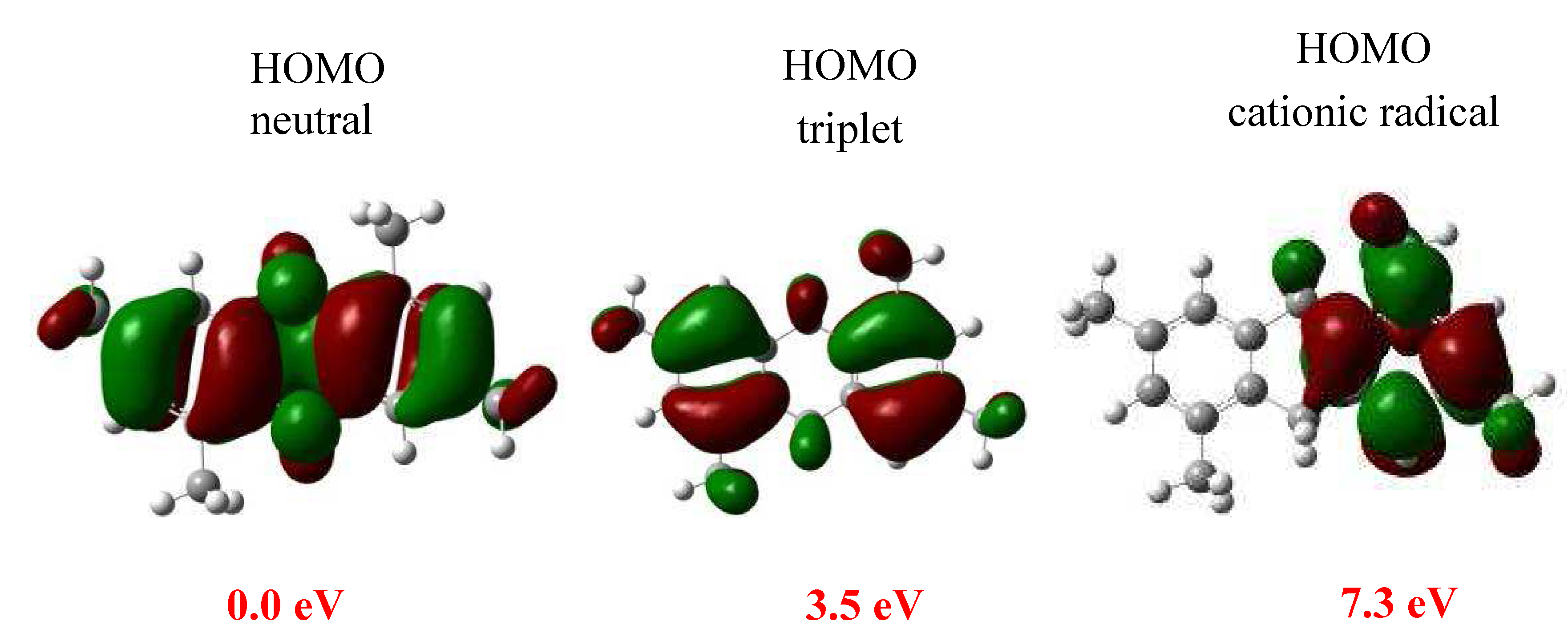

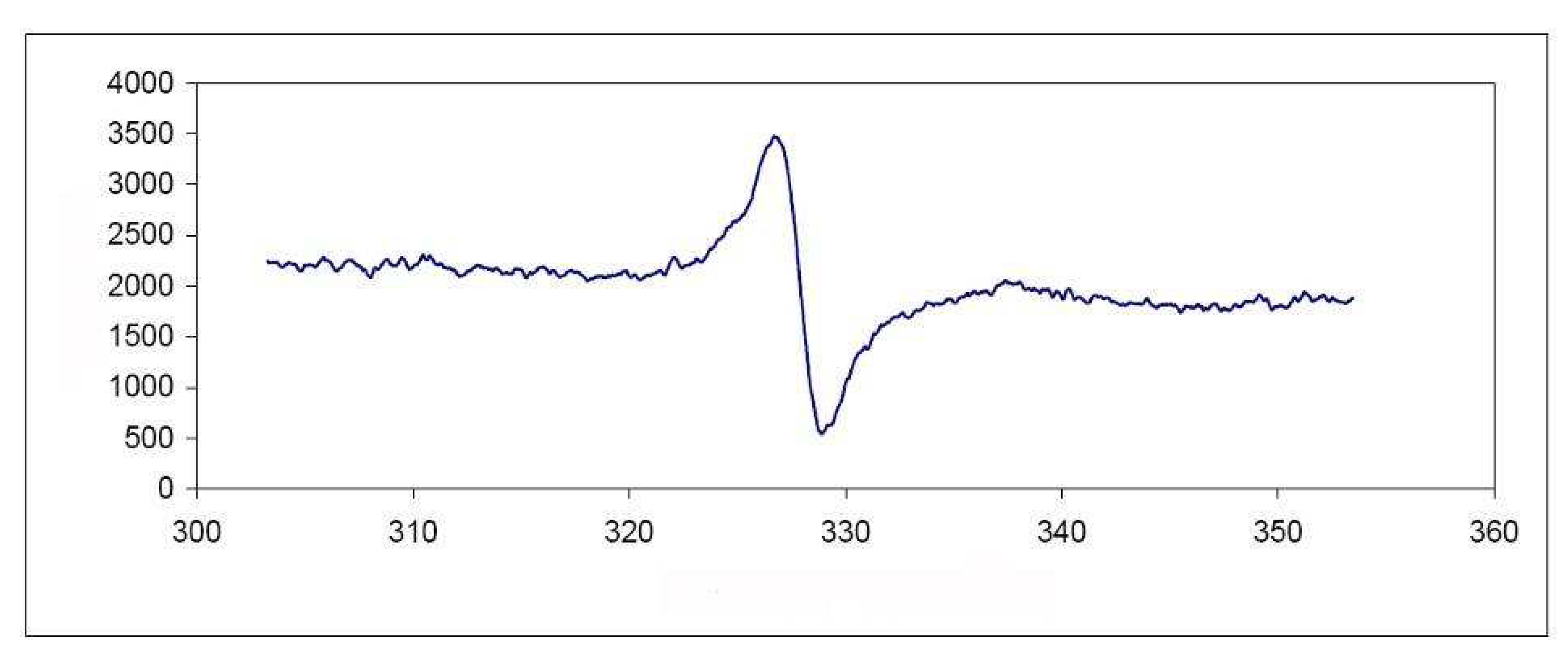

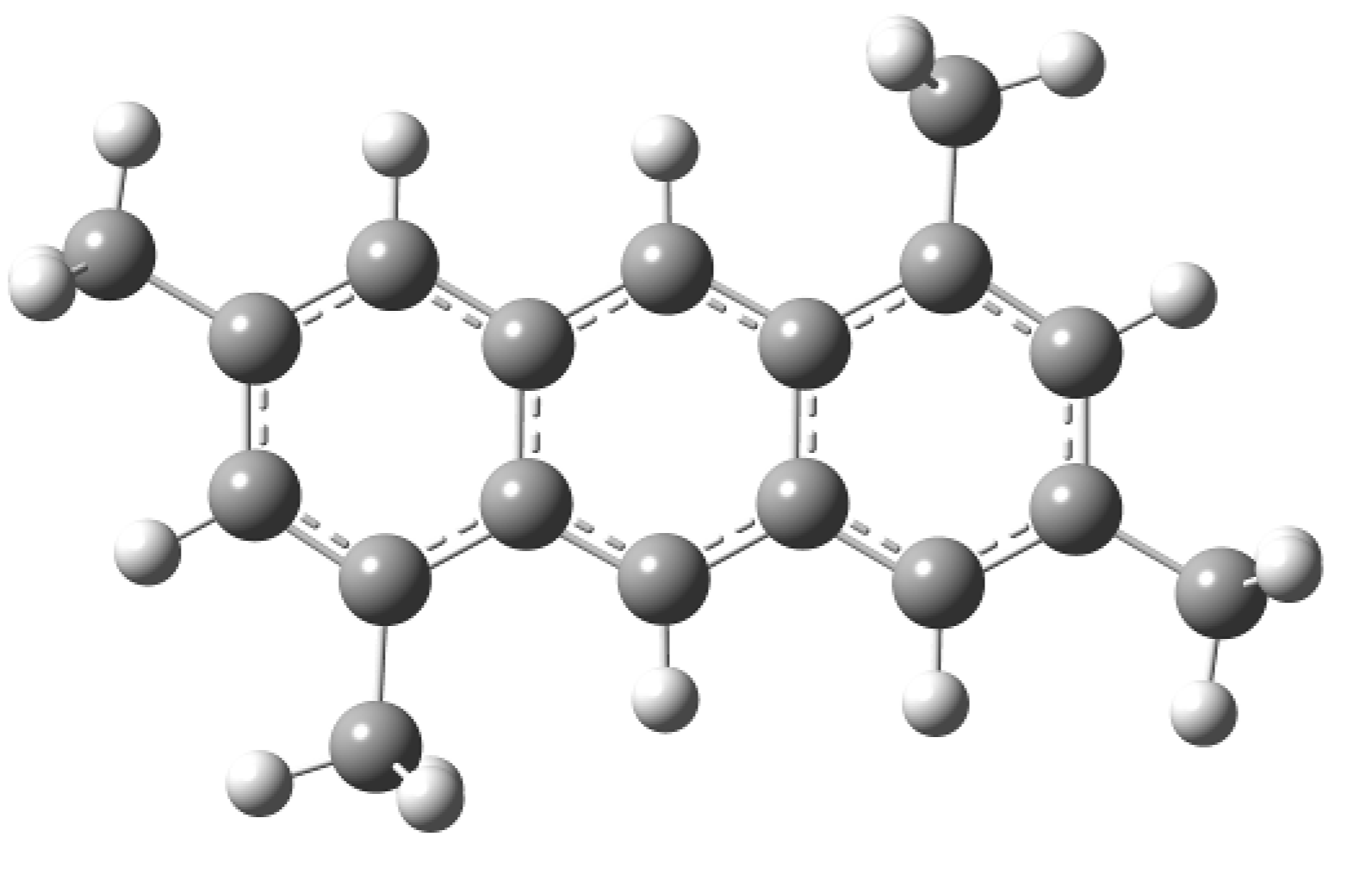

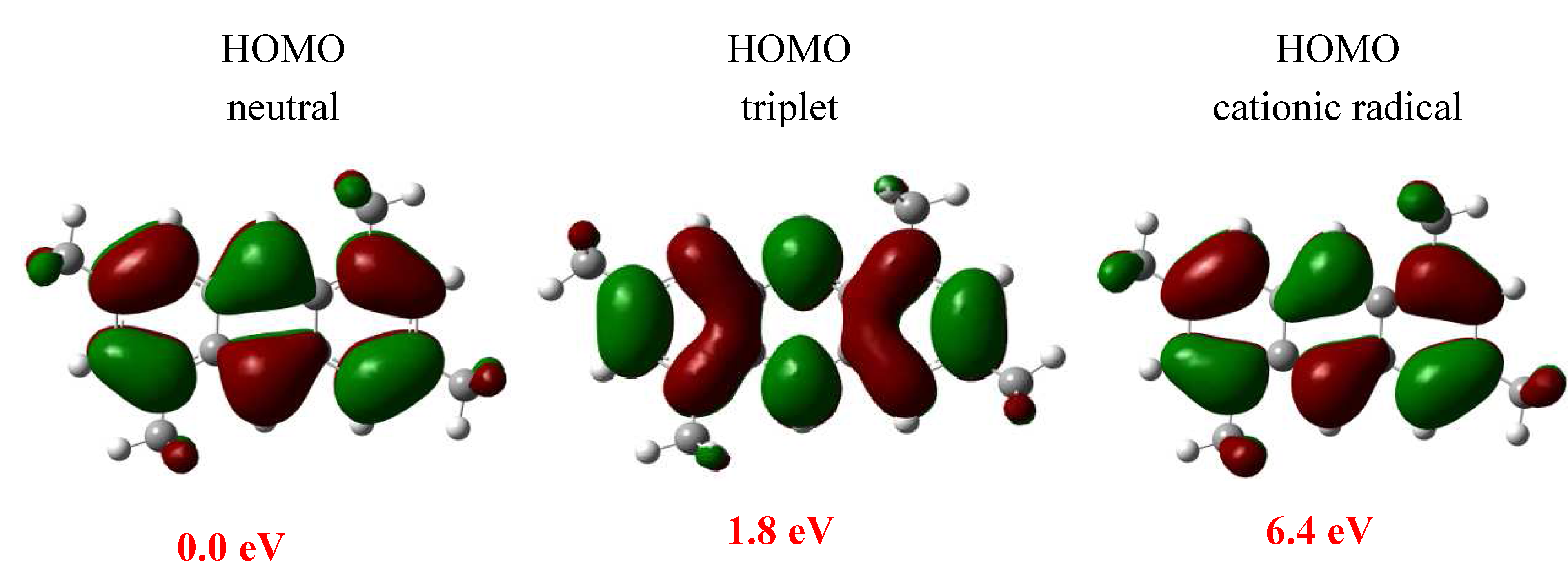

2. Results and Discussion

| C2 | C4 | C6 | C8 | C9 | C10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neutral | –0.167 | –0.176 | –0.167 | –0.176 | –0.313 | –0.313 |

| Triplet | –0.148 | –0.181 | –0.166 | –0.175 | –0.308 | –0.301 |

| Radical cationic | –0.136 | –0.159 | –0.136 | –0.159 | –0.349 | –0.349 |

| C2 | C4 | C6 | C8 | C9 | C10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neutral | –0.180 | –0.183 | –0.180 | –0.183 | –0.226 | –0.226 |

| Triplet | –0.172 | –0.201 | –0.172 | –0.201 | –0.220 | –0.220 |

| radical cationic | –0.149 | –0.160 | –0.149 | –0.160 | –0.168 | –0.168 |

| Compound | μ | η |

|---|---|---|

| 2 | –0.119 | 0.108 |

| 4 | –0.110 | 0.043 |

| 3 | –0.099 | 0.082 |

| 5 | –0.110 | 0.042 |

| Atom | 2 | 4 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| f– | f+ | f0 | f– | f+ | f0 | |

| C1 | 0.058 | 0.025 | 0.042 | 0.013 | 0.021 | 0.017 |

| C2 | –0.008 | 0.012 | 0.002 | 0.029 | 0.023 | 0.026 |

| C4 | 0.090 | 0.046 | 0.068 | 0.033 | 0.034 | 0.033 |

| C9 | –0.002 | –0.010 | –0.001 | 0.049 | 0.050 | 0.049 |

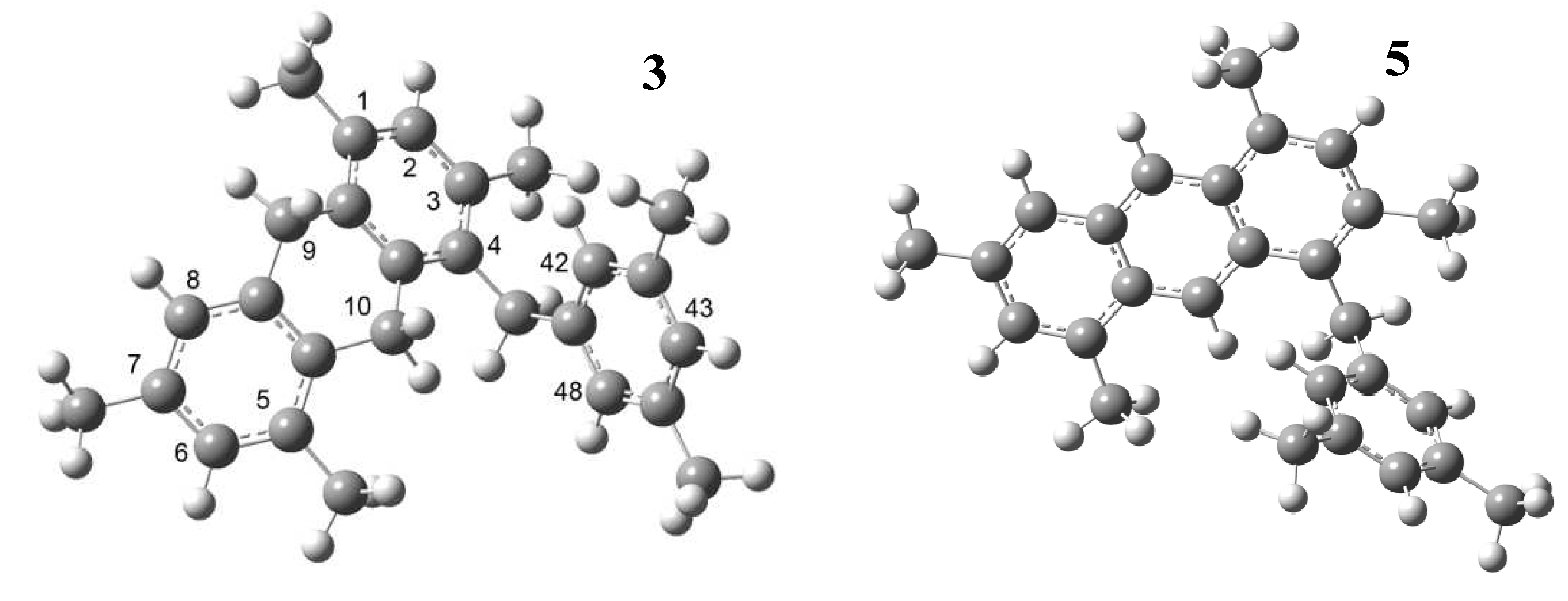

| Atom | 3 | 6 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| f– | f+ | f0 | f– | f+ | f0 | |

| C1 | 0.011 | 0.017 | 0.014 | 0.012 | 0.022 | 0.017 |

| C2 | 0.013 | 0.005 | 0.009 | 0.024 | 0.020 | 0.022 |

| C3 | 0.010 | 0.007 | 0.009 | 0.018 | –0.004 | 0.011 |

| C4 | 0.007 | 0.020 | 0.013 | 0.023 | 0.033 | 0.028 |

| C5 | 0.007 | 0.018 | 0.013 | 0.012 | 0.018 | 0.015 |

| C6 | 0.021 | 0.008 | 0.015 | 0.027 | 0.021 | 0.024 |

| C7 | 0.005 | 0.002 | 0.003 | 0.006 | 0.000 | 0.003 |

| C8 | 0.018 | 0.032 | 0.025 | 0.029 | 0.031 | 0.030 |

| C9 | –0.010 | –0.009 | –0.010 | 0.045 | 0.047 | 0.046 |

| C10 | 0.007 | –0.005 | –0.006 | 0.050 | 0.054 | 0.052 |

| C42 | 0.023 | 0.021 | 0.023 | 0.001 | –0.003 | –0.001 |

| C43 | 0.010 | 0.028 | 0.019 | –0.003 | –0.005 | –0.004 |

| C48 | 0.023 | 0.008 | 0.015 | 0.009 | 0.005 | 0.007 |

3. Experimental

3.1. General

3.2. Benzyl Alcohol Oligomerization with Tonsil

3.3. Formation of 1,3,5,7-tetramethylanthryl Radical Cation (6)

3.4. Theoretical Study

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgements

- Sample Availability: Samples of the compounds are available from the authors.

References and Notes

- Cruz-Almanza, R.; Shiba-Matzumoto, I.; Fuentes, A.; Martínez, M.; Cabrera, A.; Cárdenas, J.; Salmon, M. Oligomerization of benzylic alcohols and its mechanism. J. Mol. Catal. A. 1997, 126, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varma, R.S. Clay and clay-supported reagents in organic synthesis. Tetrahedron 2002, 58, 1235–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesan, K.; Pillai, C.N. Reactions of benzyl alcohol over oxide catalysts: A novel condensation to form anthracene. J. Catal. 1989, 119, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, R.; Arroyo, G.A.; Penieres, G.; Delgado, F.; Cabrera, A.; Alvarez, C.; Salmon, M. Preparative heterocyclic chemistry using tonsil a bentonitic clay; 1981 to 2003. Trends Heterocycl. Chem. 2003, 9, 195–235. [Google Scholar]

- Bouas-Laurent, H.; Castellan, A.; Desvergne, J.P.; Lapouyadé, R. Photodimerization of anthracenes in fluid solutions: Mechanistic aspects of the photocycloaddition and of the photochemical and thermal cleavage. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2001, 30, 248–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirose, K.; Shiba, Y.; Ishibashi, K.; Doi, Y.; Tobe, Y. An anthracene-based photochromic macrocycle as a key ring component to switch a frequency of threading motion. Chem. Eur. J 2008, 14, 981–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rameshbabu, K.; Kim, Y.; Know, T.; Yoo, J.; Kim, E. Facile one-pot synthesis of a photopatternable anthracene polymer. Tetrahed. Lett 2007, 48, 4755–4760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, R.; Tan, P.L.; Wu, H.; Yao, S.Q. Solid-phase assembly and in situ screening of protein tyrosine phosphatase inhibitors. Org. Lett. 2008, 10, 2295–2298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascal, R.A., Jr. Twisted Acenes. Chem. Rev. 2006, 106, 4809–4819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barclay, L.R.C.; Olah, G.A. Friedel-Crafts and Related Reactions; Interscience: New York, NY, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Bradsher, C.K. Aromatic cyclodehydration. Chem. Rev. 1946, 38, 447–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamato, T.; Sakaue, N.; Shinoda, N.; Matsuo, K. Selective preparation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Part 4. New synthetic route to anthracenes from diphenylmethanes using Friedel-Crafts intramolecular cyclization. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1997, 1, 1193–1199. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, J.B. Synthesis of 9-arylanthracenes. J. Org. Chem. 1966, 31, 4082–4085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, T.; Li, S.; Huang, W.; Kong, F.; Nakajima, K.; Shen, B.; Ohe, T.; Kanno, K. Homologation method for preparation of substituted pentacenes and naphthacenes. J. Org. Chem. 2006, 71, 7967–7977. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, Y.; Young, D.D.; Cruz-Montanez, A.; Deiters, A. Synthesis of anthracene and azaanthracene fluorophores via [2+2+2] cyclotrimerization reactions. Org. Lett. 2008, 10, 4661–4664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, R.; Rios, H.; Delgado, F.; Castro, M.; Cogordan, A.; Salmon, M. Characterization of a bentonitic clay and its application as catalyst in the preparation of benzyltoluenes and oligotoluenes. Appl. Catal. A 2003, 244, 217–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.; Robb, E.M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Mennucci, B.; Petersson, G.A.; et al. Gaussian 03, Revision D.01; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, S.K.; Berkowitz, M. A classical fluid-like approach to the density-functional formalism of many-electron systems. J. Chem. Phys. 1985, 83, 2976–2983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkowitz, M.; Ghosh, S.K.; Parr, R.G. On the concept of local hardness in chemistry. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1985, 107, 6811–6814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Mortier, W.J. The use of global and local molecular parameters for the analysis of the gas-phase basicity of amines. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1986, 108, 5708–5711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geerlings, P.; De Proft, F.; Langenaeker, W. Conceptual Density Functional Theory. Chem. Rev. 2003, 103, 1793–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2010 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Morales-Serna, J.A.; López-Duran, L.E.; Castro, M.; Sansores, L.E.; Zolotukhin, M.; Salmón, M. Oligomerization of 3,5-Dimethyl Benzyl Alcohol Promoted by Clay: Experimental and Theoretical Study. Molecules 2010, 15, 8156-8168. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules15118156

Morales-Serna JA, López-Duran LE, Castro M, Sansores LE, Zolotukhin M, Salmón M. Oligomerization of 3,5-Dimethyl Benzyl Alcohol Promoted by Clay: Experimental and Theoretical Study. Molecules. 2010; 15(11):8156-8168. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules15118156

Chicago/Turabian StyleMorales-Serna, José Antonio, Luis E. López-Duran, Miguel Castro, Luis E. Sansores, Mikhail Zolotukhin, and Manuel Salmón. 2010. "Oligomerization of 3,5-Dimethyl Benzyl Alcohol Promoted by Clay: Experimental and Theoretical Study" Molecules 15, no. 11: 8156-8168. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules15118156

APA StyleMorales-Serna, J. A., López-Duran, L. E., Castro, M., Sansores, L. E., Zolotukhin, M., & Salmón, M. (2010). Oligomerization of 3,5-Dimethyl Benzyl Alcohol Promoted by Clay: Experimental and Theoretical Study. Molecules, 15(11), 8156-8168. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules15118156