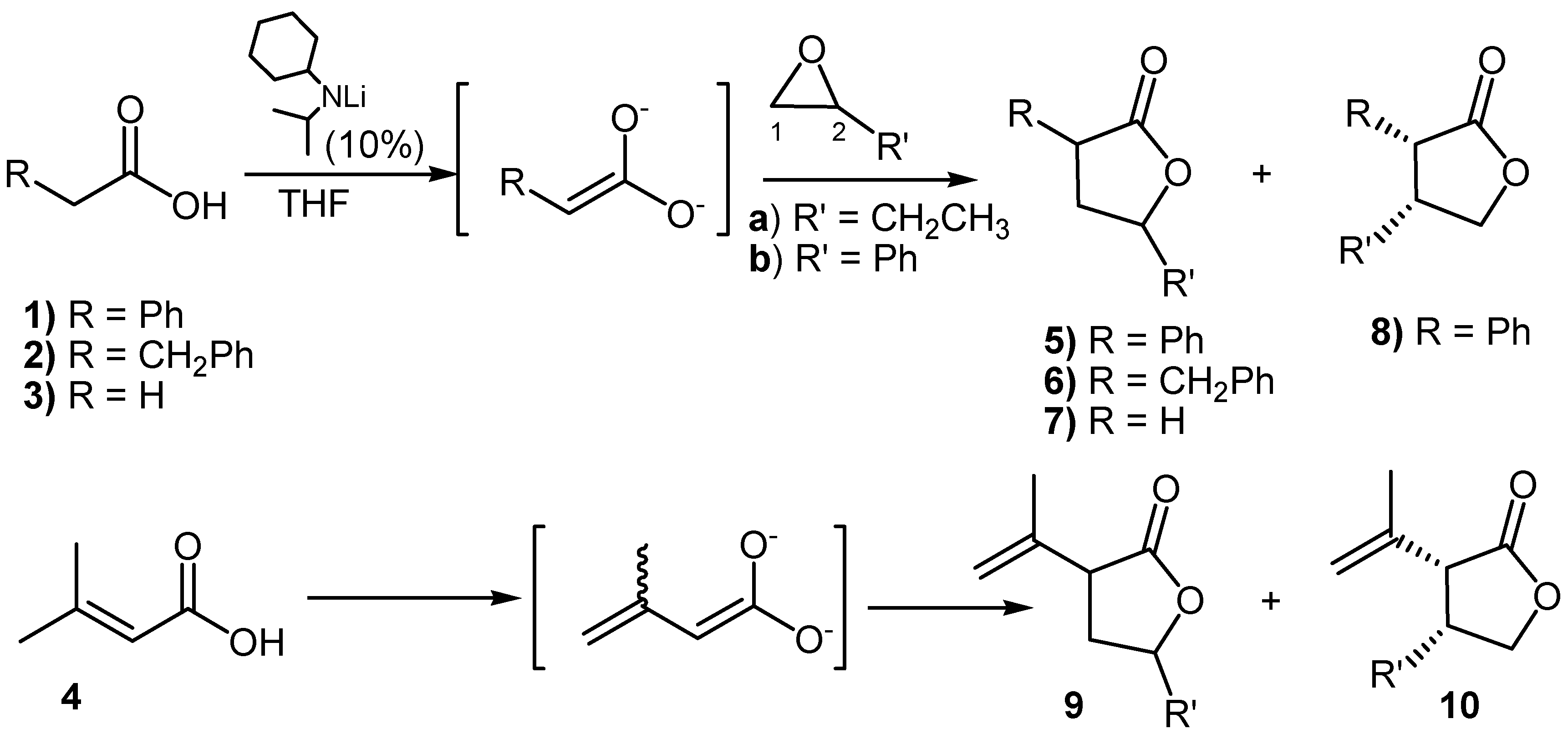

Unusual Regioselectivity in the Opening of Epoxides by Carboxylic Acid Enediolates

Abstract

:Introduction

Results and Discussion

| Entry | Products | Yields | Regioselectivity | Diastereoselectivitya | Conditionsb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C-1/C-2 attack | Anti/Syn | ||||

| 1 | 5a | 93 | 100 : 0 | 52 : 48 | |

| 2 | 6a | 48 | 100 : 0 | 66 : 34 | |

| 3 | 9a | 77 | 100 : 0 | 53 : 47 | |

| 4 | 9a | 70 | 100 : 0 | 56 : 44 | 0 ºC |

| 5 | 9a | 60 | 100 : 0 | 63 : 37 | -40 ºC |

| 6 | 5b + 8b | 96 | 79 : 21 | 56 : 44 | |

| 7 | 5b + 8b | 68 | 62 : 38 | 50 : 50 | 0 ºC |

| 8 | 5b + 8b | 86 | 70 : 30 | 63 : 37 | without LiCl |

| 9 | 5b + 8b | 80 | 52 : 48 | 58 : 42 | direct addition |

| 10 | 5b + 8b | 70 | 75 : 25 | 60 : 40 | LiF |

| 11 | 5b + 8b | 72 | 84 : 16 | 63 : 37 | LiBr |

| 12 | 6b | 50 | 100 : 0 | 63 : 37 | |

| 13 | 7b | 48 | 100 : 0 | ||

| 14 | 9b + 10b | 46 | 84 : 16 | 51 : 49 | 0 ºC |

| 15 | 9b + 10b | 77 | 100 : 0 | 53 : 47 |

good α-regioselectivity is observed in this case following the trend of reactions with α-bromoacetonitrile [8]. This is consistent with the higher charge calculated for the α-position that slightly favours attack at this site, that can be quantitative with less reactive electrophiles. The Fukui

good α-regioselectivity is observed in this case following the trend of reactions with α-bromoacetonitrile [8]. This is consistent with the higher charge calculated for the α-position that slightly favours attack at this site, that can be quantitative with less reactive electrophiles. The Fukui  functions [9] for electrophilic attacks,, for the dienolates of propionic and dimethylacrylic acid (4) were calculated. Propionic acid was calculated as a model of non-conjugated acids 2 and 3. Firstly, the structures of the corresponding dienolates were fulfil optimized using DFT methods at the B3LYP/6-31G* level [10, 11] with the Gaussian 03 suite of programs [12]. Previous theoretical structural studies of dienolates in solution have indicated the necessity to include the counter ions Li+ solvated with three solvent molecules (Et2O) [13]. The geometry of the corresponding optimized dianions is given in Figure 1.

functions [9] for electrophilic attacks,, for the dienolates of propionic and dimethylacrylic acid (4) were calculated. Propionic acid was calculated as a model of non-conjugated acids 2 and 3. Firstly, the structures of the corresponding dienolates were fulfil optimized using DFT methods at the B3LYP/6-31G* level [10, 11] with the Gaussian 03 suite of programs [12]. Previous theoretical structural studies of dienolates in solution have indicated the necessity to include the counter ions Li+ solvated with three solvent molecules (Et2O) [13]. The geometry of the corresponding optimized dianions is given in Figure 1.

= 0.57, being this position the preferred for an electrophilic attack. For the dienolate of acid 4 analysis of the Fukui functions shows a charge delocalization along the conjugated π system. The corresponding values,

= 0.57, being this position the preferred for an electrophilic attack. For the dienolate of acid 4 analysis of the Fukui functions shows a charge delocalization along the conjugated π system. The corresponding values,  = 0.41 at the α-carbon and 0.31 at the γ-carbon, show a larger nucleophilic activation at the α-position than the γ-one. Therefore it will be expected the reaction to be regioselective towards reagents that favour a SN2 mechanism, being the major products those results from attacks to the α-carbon.

= 0.41 at the α-carbon and 0.31 at the γ-carbon, show a larger nucleophilic activation at the α-position than the γ-one. Therefore it will be expected the reaction to be regioselective towards reagents that favour a SN2 mechanism, being the major products those results from attacks to the α-carbon.

Conclusions

Experimental

General

General procedure for addition reactions.

Acknowledgements

References and Notes

- See for example: McGarrigle, E.M.; Gilheany, D.G. Chromium- and Manganese-salen Promoted Epoxidation of Alkenes. Chem. Rev. 2005, 105, 1563–1602. [Google Scholar] Xia, Q.-H.; Ge, H.-Q.; Ye, C.-P.; Liu, Z.-M.; Su, K.-X. Advances in Homogeneous and Heterogeneous Catalytic Asymmetric Epoxidation. Chem. Rev. 2005, 105, 1603–1662. [Google Scholar]

- Izquierdo, J.; López, I.; Rodriguez, S.; González, F. Epoxides as useful synthetic building blocks. Recent Res. Devel. Org. Chem. 2006, 10, 53–61. [Google Scholar] Gansäuer, A.; Fan, C.-A.; Keller, F.; Karbaum, P. Regiodivergent Epoxide Openings: A Concept in stereoselective Catalysis beyond Classical Kinetic Resolutions and Desymmetrizations. Chem. Eur. J. 2007, 13, 8084–8090. [Google Scholar] Petragnani, N.; Yonashiro, M. The Reactions of Dianions of Carboxylic Acids and Ester Enolates. Synthesis 1982, 521–578. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, S. K. Reactions of Epoxides with Ester, Ketone and Amide Enolates. Tetrahedron 2000, 56, 1149–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blicke, F. F.; Wright, P. E. The Reaction of Propylene Oxide, Styrene Oxide, and Cyclohexene Oxide with an Ivanov Reagent. J. Org. Chem. 1960, 25, 693–698. [Google Scholar] Fujita, T.; Watanabe, S.; Suga, K. Reaction of carboxylic-acids with epoxides using lithium naphthalenide. Australian. J. Chem. 1974, 27, 2205–2218. [Google Scholar]

- Movassaghi, M.; Jacobsen, E.N. A Direct Method for the Conversion of Terminal Epoxides into γ-Butanolides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 2456–2457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, S.; Torres, M.; Ortúzar, N.; Wincewicz, R.; Parra, M. Efficient Addition of Acid Enediolates to Epoxides. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2004, 2160–2165. [Google Scholar]

- Gil, S.; Parra, M. Dienediolates of carboxylic acids in synthesis. Recent advances. Curr. Org. Chem. 2002, 6, 283–302. [Google Scholar] Gil, S.; Parra, M. Reactivity control of dianions of carboxylic acids. Synthetic applications. Recent Res. Devel. Org. Chem. 2002, 6, 449–481. [Google Scholar]

- Gil, S.; Parra, M.; Rodriguez, P. A simple synthesis of γ-aminoacids. Tetrahedron Lett. 2007, 48, 3451–3453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parr, R.G.; Yang, W. Density functional-approach to the frontier-electron theory of chemical-reactivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1984, 106, 4049–4050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becke, A. D. Density-functional thermochemistry .3. the role of exact exchange. J. Chem. Phys. 1993, 98, 5648–5652. [Google Scholar] Lee, C.; Yang, W.; Parr, R.G. Development of the Colle-Salvetti correlation-energy formula into a functional of the electron-density. Phys. Rev. B 1988, 37, 785–789. [Google Scholar]

- Hehre, W.J.; Radom, L.; Schleyer, P.v.R.; Pople, J.A. Ab initio Molecular Orbital Theory; Wiley: New York, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Frisch, M. J.; Trucks, G. W.; Schlegel, H. B.; Scuseria, G. E.; Robb, M. A.; Cheeseman, J. R.; Montgomery, J., J. A.; Vreven, T.; Kudin, K. N.; Burant, J. C.; Millam, J. M.; Iyengar, S. S.; Tomasi, J.; Barone, V.; Mennucci, B.; Cossi, M.; Scalmani, G.; Rega, N.; Petersson, G. A.; Nakatsuji, H.; Hada, M.; Ehara, M.; Toyota, K.; Fukuda, R.; Hasegawa, J.; Ishida, M.; Nakajima, T.; Honda, Y.; Kitao, O.; Nakai, H.; Klene, M.; Li, X.; Knox, J. E.; Hratchian, H. P.; Cross, J. B.; Adamo, C.; Jaramillo, J.; Gomperts, R.; Stratmann, R. E.; Yazyev, O.; Austin, A. J.; Cammi, R.; Pomelli, C.; Ochterski, J. W.; Ayala, P. Y.; Morokuma, K.; Voth, G. A.; Salvador, P.; Dannenberg, J. J.; Zakrzewski, V. G.; Dapprich, S.; Daniels, A. D.; Strain, M. C.; Farkas, O.; Malick, D. K.; Rabuck, A. D.; Raghavachari, K.; Foresman, J. B.; Ortiz, J. V.; Cui, Q.; Baboul, A. G.; Clifford, S.; Cioslowski, J.; Stefanov, B. B.; Liu, G.; Liashenko, A.; Piskorz, P.; Komaromi, I.; Martin, R. L.; Fox, D. J.; Keith, T.; Al-Laham, M. A.; Peng, C. Y.; Nanayakkara, A.; Challacombe, M.; Gill, P. M. W.; Johnson, B.; Chen, W.; Wong, M. W.; Gonzalez, C.; Pople, J. A. Gaussian 03, Revision C.02, Frisch, M.J., et al., Eds.; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford CT, 2004.

- Domingo, L.R.; Gil, S.; Mestres, R.; Picher, M.T. Theoretical Model of Solvated Lithium Dienediolate of 2-Butenoic Acid. Tetrahedron 1995, 51, 7207–7214. [Google Scholar] Domingo, L.R.; Gil, S.; Mestres, R.; Picher, M.T. Theoretical Model of Solvated Lithium Dienediolate of Methyl Substituted 2-Butenoic Acid. Tetrahedron 1996, 52, 11105–11112. [Google Scholar]

- Azizi, N.; Mirmashhori, B.; Saidi, M.R. Lithium perchorate promoted highly regioselective ring opening of epoxides under solvent-free conditions. Catalysis Commun. 2007, 8, 2198–2203. [Google Scholar] Das, B.; Krishnaiah, M.; Thirupathi, P.; Laxminarayana, K. An efficient catalyst-free regio- and stereoselective ring-opening of epoxides with phenoxides using polyethylene glycol as the reaction medium. Tetrahedron Lett. 2007, 48, 4263–4265. [Google Scholar] Fringuelli, F.; Piermatti, O.; Pizzo, F.; Vaccaro, L. Ring Opening of Epòxides with Sodium Azide in Water. A Regioselective pH-controlled Reaction. J. Org. Chem. 1999, 64, 6094–6096. [Google Scholar]

- Sarangi, C.; Das, N.B.; Nanda, B.; Nayak, A.; Sharma, R.P. An Efficient Nucleophilic Cleavage of Oxiranes to 1,2-Azido Alcohols. J. Chem. Res. (S) 1997, 378–379. [Google Scholar]

- Myers, A.G.; McKinstry, L. Practical Synthesis of Enantiomerically Enriched γ-Lactones and γ-Hydroxy Ketones by the Alkylation of Pseudoephedrine Amides with Epoxides and their Derivatives. J. Org. Chem. 1996, 61, 2428–2440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sample Availability: Samples 5a, 5b and 8 are available from the authors.

© 2008 by the authors. Licensee Molecular Diversity Preservation International, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open-access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Domingo, L.R.; Gil, S.; Parra, M.; Segura, J. Unusual Regioselectivity in the Opening of Epoxides by Carboxylic Acid Enediolates. Molecules 2008, 13, 1303-1311. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules13061303

Domingo LR, Gil S, Parra M, Segura J. Unusual Regioselectivity in the Opening of Epoxides by Carboxylic Acid Enediolates. Molecules. 2008; 13(6):1303-1311. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules13061303

Chicago/Turabian StyleDomingo, Luis R., Salvador Gil, Margarita Parra, and José Segura. 2008. "Unusual Regioselectivity in the Opening of Epoxides by Carboxylic Acid Enediolates" Molecules 13, no. 6: 1303-1311. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules13061303

APA StyleDomingo, L. R., Gil, S., Parra, M., & Segura, J. (2008). Unusual Regioselectivity in the Opening of Epoxides by Carboxylic Acid Enediolates. Molecules, 13(6), 1303-1311. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules13061303